Abstract

This study investigates the mechanical and durability performance of sustainable concrete using stone dust (SD) and ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) to partially replace natural sand and cement, respectively. The experimental program was conducted with concrete containing 0–40 wt% GSCBA and 100% SD were prepared and tested. The results showed that full replacement of natural sand with SD did not significantly affect compressive strength. Concrete containing 10% GSCBA and 100% SD (10GSCBA) exhibited comparable compressive strength to the control concrete (CON) up to 90 days. However, the modulus of elasticity and modulus of rupture decreased slightly with increasing GSCBA content, indicating a close correlation with compressive strength. The mix containing 40% GSCBA and 100% SD (40GSCBA) achieved a compressive strength of 42.6 MPa at 90 days, representing 91% of the CON, with acceptable durability performance. These findings demonstrate that the combined utilization of SD and GSCBA offers an innovative and eco-efficient solution for concrete production, contributing to reduced cement consumption, lower production costs, and minimized carbon emissions without necessarily affecting mechanical strength or the long-term viability of the system.

1. Introduction

The high growth rate of the construction industry has increased the need to find sustainable alternatives to traditional raw materials. Sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA) and stone dust (SD) are some of the industrial by-products that have been identified as potential supplementary cementitious and fine aggregate materials for concrete production. SCBA, a by-product of the sugar industry’s burning process, is rich in silica and possesses pozzolanic properties, making it effective as a partial substitute for cement [1,2]. SD, which is produced during the aggregate crushing process, is available in large quantities and can be utilized as an alternative to natural river sand, thereby minimizing the environmental impact associated with sand mining [3]. These materials have potential benefits of sustainability, but their utilization is limited by several reasons. The combustion temperature, particle fineness, and processing techniques of SCBA have a considerable influence on its chemical makeup, amorphous silica composition, and, therefore, its pozzolanic characteristics [1]. The differences in these parameters bring about differences in reactivity and concrete performance. Similarly, over-substitution of natural sand with stone dust may cause diminutive workability and mechanical properties because of its angular and fine particle structure [3]. This variability poses problems in the sustenance of standardized performance of ready-mixed concrete [4]. Hence, it is critical to optimize mix design and perform mix interaction analysis to guarantee a consistent performance and sustainable results.

Recent developments have shown that SCBA as a partial cement replacement can increase long-term strength and durability, which is mostly due to the augmentation of pozzolanic reactions and microstructural densification [5,6,7,8]. It has been demonstrated [6,7] that finely ground SCBA with a low loss on ignition (LOI) enhances workability, compressive strength, and compactness of the microstructures as a result of its large amorphous silica content, which favors secondary C-S-H formation. Conversely, coarse particle SCBA and high unburnt carbon SCBA have less reactivity and inconsistent development of strength. In addition, the mechanical performance of environmentally friendly concrete that contains SCBA is highly controlled by its fineness and purity, with finer, well-calcined ash giving good strength and durability, and high-LOI ash giving low workability and efficiency of hydration [7]. Other studies [8,9] have also been able to confirm the fact that the high-volume SCBA concrete with the high proportion of amorphous SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2 O3 has better long-term performance and chloride-resistance due to the presence of the pozzolanic reaction and pore refinement. Also, it has been noted that the addition of finely ground SCBA with limestone powder has also been found to further enhance chloride resistance and permeability by synergistic packing of particles and secondary hydration reactions [9]. All these results suggest that the positive effects of the SCBA on the concrete performance are directly associated with the size of the particles, LOI, and chemical composition that determine its reactivity, hydration kinetics, and pore structure.

In the case of SD, its fine angular particles tend to raise the water requirement and also redefine the workability but may enhance the packing density as well as porosity when applied in the best proportions [3]. Therefore, though both SCBA and SD are capable of separately improving the performance and sustainability of concrete, their combined use is not well-researched. Most of the past studies have focused on SCBA or stone dust individually, but very little has been attempted to assess their interactions when it comes to concrete [6,7,8,9]. As the pozzolanic activity is the primary method to alter the binder matrix with the SD acting as an auxiliary to enhance the granular structure with better packing, the joint application of both is subject to higher mechanical strength, compressive strength, and environmental performance. Thus, this work will attempt to investigate the synergistic effect of ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) and stone dust (SD) on the mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of concrete in an attempt to fill an existing gap in knowledge and contribute to the sustainable use of industrial by-products in the context of the circular economy. In addition, critical performance features such as abrasion resistance, long-term stability, and environmental safety, and, especially, the leaching capability of heavy metals, have not been studied in depth. The above research gaps make the further use of these materials in commercial concrete production difficult.

To fill these gaps, the current research systematically examines the concurrent use of ground SCBA (GSCBA) and SD as part cement and complete replacement of sand in ready-mixed concrete. The study is a novel combination of mechanical, durability, and microstructural testing and environmental safety analysis, which gives a comprehensive insight into the material performance. Through laboratory findings and industrial viability, this research provides a scientific basis of eco-efficiency, cost-efficiency, and scalability of concrete technologies, thus developing sustainable practices and helping the construction industry to move to the circular economy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Preparation

In this study, original sugarcane bagasse ash (OSCBA) was obtained at biomass power plants in Lopburi Province, Thailand (Figure 1). The OSCBA was dried in the oven at 110 ± 5 °C and blended to a state where the mass that was left on a sieving-grate of 45 µm was less than 1.0% wt. In grinding (Figure 2a), OSCBA (10 kg) was ground in a Los Angeles abrasion machine (on laboratory scale) using 50 kg of steel balls with different diameters. Optimized ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) was obtained through a duration of 240 min (Figure 2b). The GSCBA, then, was characterized in terms of its chemical composition using X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and its strength activity index was assessed against the ASTM C618. Although the specific grinding energy of GSCBA was not directly measured, the efficiency of the grinding process was evaluated through particle size reduction and the strength activity index (SAI), as defined by ASTM C618, exceeded 75%. These results confirm that the adopted grinding duration achieved adequate fineness and pozzolanic reactivity suitable for cementitious applications. The quantification of specific grinding energy will be considered in future large-scale investigations to enhance the comprehensiveness of the LCA and improve the accuracy of energy-related environmental impact estimations.

Figure 1.

Original sugarcane bagasse ash (OSCBA) from a sugar production facility in Lopburi Province, Thailand.

Figure 2.

Photographs and micrographs of (a) original sugarcane bagasse ash (OSCBA), (b) ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA), (c) OSCBA at 1000×, and (d) GSCBA at 1000×.

Stone dust (SD) used in this study was improved by washing and was subsequently sieved to obtain a particle size distribution closely matching the gradation limits specified in ASTM C33. SD was collected in the Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, southern Thailand. Its physical characteristics were established according to ASTM requirements, such as fineness modulus (ASTM C136), finer than No. 200 sieve (ASTM C117), and specific gravity and water absorption (ASTM C128). Coarse aggregate was crushed limestone at maximum size was 10 mm; Meanwhile, fine aggregate (river sand) was sieved using a No. 4 sieve.

In this study, hydraulic cement (HC) was in accordance with ASTM C1157 [10] Type GU (General Use), which is equivalent in performance to Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC Type I). Its chemical and physical characteristics were tested as related to compatibility with GSCBA in blended concrete systems.

2.2. Concrete Mix Design, Casting, and Testing

Concrete mixtures were designed to achieve a target compressive strength of 350 kg/cm2, with the cement content partially replaced by ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) at 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt% of binder (Table 1). In all mixes, natural river sand was fully substituted with stone dust as fine aggregate. The selection of 10–40% GSCBA replacement levels was guided by evidence from previous literature [1,2,5,6,7,8,9] and preliminary experimental trials. Earlier studies have consistently indicated that low to moderate GSCBA incorporation levels (≤40%) provide an optimal balance among mechanical strength, pozzolanic activity, and workability, while also contributing to environmental sustainability. Replacement levels below 10% yield only marginal benefits in cement reduction and sustainability improvement, whereas excessive substitution beyond 40% tends to dilute the binder matrix, limiting calcium hydroxide availability for secondary pozzolanic reactions and thereby reducing strength. Accordingly, the 10–40% range was systematically adopted to allow a comprehensive evaluation of the mechanical, durability, and microstructural performance of GSCBA-blended concretes, and to determine the optimal substitution level that preserves structural integrity while promoting sustainable and resource-efficient construction practices [1,2,5,6,7]. The water-to-binder ratio was maintained at 0.45. The polycarboxylate ether polymer superplasticizer (type F) was employed to maintain the slump of all concrete mixtures in the range of 150–200 mm. Compressive strength of all concrete was determined according to ASTM C39 (2016) [11], and elastic modulus (ASTM C469 [12]). After mixing, a cylinder test specimen of 100 mm diameter and 200 mm height was prepared as a customary practice in the concrete investigation. After 24 h of casting, the specimens were demolded and transferred to a water tank for submerged curing. Flexural strength in accordance with ASTM C78 [13], drying shrinkage (ASTM C157 [14]), water permeability (Darcy’s law), abrasion resistance (ASTM C944 [15]), and chloride penetration (ASTM C1202 [16]) were tested on hardened concrete. The average result of three concrete specimens was recorded for each testing age.

Table 1.

Mix proportions of concrete.

2.3. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Economic Analysis

To evaluate the environmental impacts of the proposed materials, a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment (LCA) was conducted in accordance with ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards [17,18]. The system boundary encompassed all major stages, including raw material acquisition, processing, transportation, and concrete production. Life cycle inventory data were compiled from both laboratory experiments and secondary databases, covering material consumption, energy use, and emissions associated with each process. The primary impact indicator considered was the global warming potential (GWP), expressed in kilograms of CO2 equivalent (kg CO2-eq) per cubic meter of concrete.

In parallel, an economic evaluation was performed to assess the production cost and potential cost–benefit of GSCBA-blended concrete in comparison with conventional mixtures, including the corresponding reduction in CO2 emissions (Table 2). All economic calculations were conducted in U.S. dollars. However, the emission factors for raw materials and processes following ISO 14040/14044 standards. For GSCBA, secondary data from literature reviewed describing the production of sugarcane bagasse ash and its processing energy were adopted and validated against laboratory energy consumption data to ensure representativeness and consistency with local conditions.

Table 2.

Emission factors of raw materials.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Binder

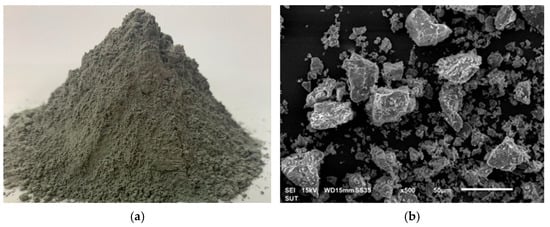

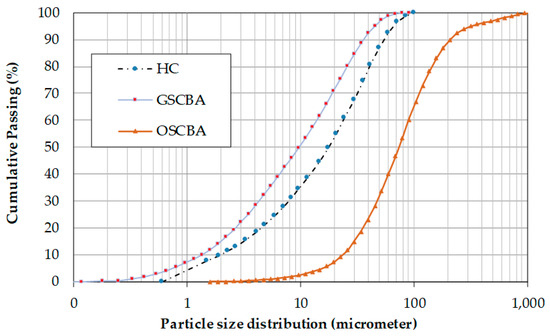

The physical and chemical properties of hydraulic cement (HC) (Figure 3a) and ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) are the substances investigated, which proves the strong evidence of the synergistic effect of these substances in the production of sustainable concrete as shown in Table 3. The hydraulic cement in this research conforms with ASTM C1157 Type GU standards, which has CaO (61.6) and SiO2 (21.9) as its major oxides, and the median particle size is 17.7 µm (Figure 4). These ratios are the ones characteristic of a regular hydraulic cement though they also point at the relatively high proportion of calcium content, which guarantees proper hydration kinetics in strength formation [21]. Microstructural examination showed angular, dense, and irregular particles (Figure 3b), a morphology that not only improves packing density but also facilitates nucleation locations of hydration products. This is essential in the development of a stable matrix that is less porous [1]. This type of particle morphology has been attributed to an improved mechanical interlocking in blended cementitious systems, which supports the possibility of HC as a stable binding phase when used together with additional materials [22].

Figure 3.

Photographs and micrographs of (a) hydraulic cement; and (b) scanning electron microscopies of at 500× magnification.

Table 3.

Chemical compositions and physical properties of hydraulic cement (HC) and ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA).

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution of materials.

In comparison, the GSCBA had significantly different physical and chemical characteristics (Table 3). It was composed mainly of reactive SiO2 (>60%), and minor amounts of Al2O3 and Fe2O3, and thus it was a very pozzolanic material [2,9]. The average fine grinding size of the particles was less than 10 μm (Figure 4), which was greatly lower than HC, giving an increased specific surface area promoting the pozzolanic reaction [23]. Porous and irregular particles (Figure 2d) observed morphologically were beneficial to absorb water and be more reactive but can impact workability when not managed through admixtures [24]. The synergistic effect of the HC and GSCBA combination could be explained by the pozzolanic reaction, when amorphous silica in the GSCBA reacts with calcium hydroxide released during the hydration of cement to produce further calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H). This process not only causes strength gain in the long term but also enhances durability through a decrease in free lime content and optimizing pore structure [25]. Moreover, the substitution of the natural clinker material with agro-industrial byproducts, such as GSCBA, is directly correlated with the concept of the circular economy, and it has both environmental and economic advantages [4].

Conversely, original sugarcane bagasse ash (OSCBA) (Figure 2a) had coarse and porous particles (d50 = 79.1 μm) (Figure 4), which decreased its direct pozzolanic reactivity as the silica phases are not readily dissolved [26]. The resultant GSCBA, after controlled grinding, had a mean particle size of 6.40 and specific gravity of 2.12 and showed a high level of refinement, which enhances packing density and dispersion of the particles in cementitious matrices [27]. The high degree of specific surface area increases the kinetics of the reaction under consideration with more sites of nucleation and faster consumption of portlandite [28]. The observations performed by SEM showed that GSCBA is made up of angular, fractured, and porous particles (Figure 2d). The benefit of such a morphology is that fractured angular edges enhance mechanical interlocking in the cement matrix, and the porous texture allows water to absorb it, enhancing local dissolution of silica and alumina phases [29]. These properties are the reason why finely ground GSCBA is significantly more reactive than its non-processed counterpart.

In terms of chemical composition, SiO2 (61.1%), Al2O3 (7.9%), and Fe2O3 (6.2%) constitute the major chemical components present in GSCBA, and the total sum of SiO2 + Al2O3 + Fe2O3 is 75.2% wt% (Table 3). This material satisfies the requirements of ASTM C618 of Class N as stated by ASTM C618, indicating that it is a reactive supplementary cementitious material [24]. However, the comparably high percentage of silica is especially important because it increases the possibility of reaction with portlandite [Ca(OH)2], a product of cement hydration, to produce secondary calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gels [30]. Such a reaction is additionally known to enhance the development of long-term strengths besides enhancing the refinement of the microstructure in the sense that the connectivity degree of the capillary pores is minimized, resulting in enhanced durability functions in mixed concretes [8,9,23,28,29].

3.2. Properties of Aggregates

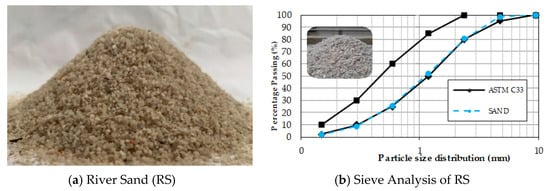

3.2.1. River Sand (RS)

The fine aggregate that was used in this study was the natural river sand that is located in Thailand, as shown in Figure 5a. The fundamental physical characteristics of the sand, which have been sieved No. 4 (Figure 5b) were to be assessed based on ASTM standards. In particular, the fineness modulus (FM) was analyzed according to the ASTM C33 [31], and specific gravity (SSD) and water absorption were measured according to the ASTM C128 [32]. An analysis of the results, as summarized in Table 4, reveals that the specific gravity of the river sand at saturated surface-dry (SSD) is 2.62, the fineness modulus is 2.78, and the water absorption is 1.10%. The fine aggregate was first kept in the SSD condition before mixing. These properties affirm that the river sand meets ASTM C33 requirements on fine aggregates in entirety, making it apt for use in high-performance concrete. The result can be used as a viable confirmation of the use of local materials in the structure, and cost-effective and regionally available materials can be used in the construction works of civil engineering.

Figure 5.

Photographs and cumulative passing of river sand and stone dust.

Table 4.

Specific properties of aggregate.

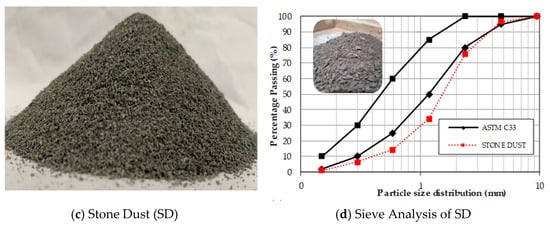

3.2.2. Stone Dust (SD)

The stone dust (SD) used in this study was limestone-based, obtained from a quarry located in the southern region of Thailand (Figure 5c). Table 4 presents its key physical properties: fineness modulus of 3.72, saturated surface-dry (SSD) specific gravity of 2.76, water absorption of 1.33%, and 15.86% passing the No. 200 sieve. Compared with ASTM C136 [33] and ASTM C117 [34], the fineness modulus exceeded the recommended range (2.3–3.1), while the percentage passing the No. 200 sieve was higher than the 3% limit specified by ASTM C33 [31]. The particle size distribution (Figure 5d) also deviated slightly from the upper and lower bounds of the ASTM C33 grading curve for fine aggregates.

Although the SD did not fully meet ASTM C33 grading requirements, its higher fine content improved particle packing density, which enhanced the interfacial transition zone and overall compactness of the concrete matrix. The increased fines slightly reduced workability but did not compromise strength performance. In fact, the resulting mixture exhibited compressive strength comparable to the control mix, indicating that the off-spec gradation of SD can positively influence microstructural densification and strength development. These findings suggest that locally sourced limestone dust, despite its nonconformance with standard grading, remains a viable and sustainable fine aggregate alternative for blended concrete applications.

3.2.3. Coarse Aggregate

The physical properties of coarse aggregate are shown in Table 4. Crushed limestone was sieved passing through sieve 3/8 and retained on sieve No. 4, a maximum size of 10 mm, having a specific gravity of 2.63, water absorption of 0.68%, and fineness modulus of 5.52 was used as coarse aggregate.

3.3. Mortar Performance with GSCBA as Partial Cement Replacement and Stone Dust as Full Sand Replacement

3.3.1. Water Requirement of Mortar

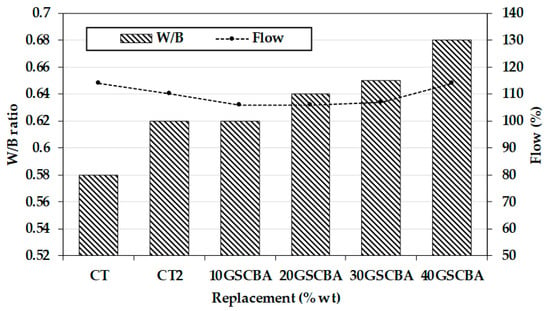

Figure 6 shows the water requirement of mortars with GSCBA used as a partial replacement of hydraulic cement (HC) at 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt% of binder with stone dust (SD) fully replacing river sand (RS) (10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA mortar). The combined ratios of the six mortar samples are described in Table 5.

Figure 6.

Effect of GSCBA and stone dust on flowability and water requirement of mortar.

Table 5.

Mix Proportions of six mortar samples.

The results showed that the water requirement for mortars with a flow value in the range of 110 ± 5% increased when HC is replaced with an increased amount of GSCBA. The control mortars with RS (CT mortar) and control mortars with SD (CT2 mortar) had W/B 0.58 and 0.62, respectively. Conversely, the 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA mortar required more W/B of 0.62, 0.64, 0.65, and 0.68, respectively, to sustain the same flow (110 ± 5%) [35,36,37]. This is due to morphological properties of GSCBA particles that can be explained by the fact that smooth and rough surfaces, as well as partial porosity, are merged, and that is why the water demand is observed to increase. Also, the GSCBA has a smaller average particle size than HC, which means that it has a much greater specific surface area that needs more water to obtain the same workability. This is in line with the previous investigations on other biomass-engineered pozzolanic materials like rice husk ash and palm oil fuel ash, which also indicate their greater water demand compared to other materials based on surface area and irregular particle geometry [30,35,36,37]. Analytically, the findings are new information on the effect of agro-industrial byproducts on the rheology of mortar. The augmented water need is not just a mathematical procedure of mix design but also the latent action by which the morphology and microstructural porosity of particles impact hydration kinetics and early age workability. These findings highlight the translational characteristics of GSCBA as a long-term cementitious compound, which creates an opportunity to cut down on the usage of regular cement without compromising on the feasible performance characteristics of mortar production.

3.3.2. Compressive Strength of Mortar

Table 6 is a summary of the compressive strength of mortars. The mixes assessed were CT, CT2, 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA mortars. In the case of the control mortar (CT), the average compressive strengths of 1, 3, 7, 28, and 60 days of water curing were 14.9, 26.6, 30.2, 39.8, and 47.7 MPa, respectively, which is in line with the earlier findings reported regarding conventional mortars [28,29,30]. Control mix (CT2), where all the RS was substituted with SD, attained compressive strengths of 14.8, 26.4, 31.6, 38.9, and 46.6 MPa, respectively, which established that full substitution of sand with stone dust did not substantially reduce early-age or late-age strengths. Mortars containing a rising proportion of GSCBA had a slowly declining early-age strength, indicating the diminution in the content of HC, and thus restricted the initial pozzolanic actions between Ca(OH)2 (generated by cement dissolution) and the active SiO2 and Al2O3 in GSCBA. The compressive strength of 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA mortars at 1 and 3 days was 10.1–26.4 MPa, which is 68–95% of the CT mortar [35,36,37]. An increased water need of GSCBA-containing mortars to sustain a target spread flow of 110 ± 5% led to higher water-to-binder ratios (W/B), which, in turn, led to a minor reduction in early-age strength.

Table 6.

Compressive strength of mortar.

The compressive strengths of 10GSCBA-40GSCBA mortars at 7 and 28 days were 23.9–39.4 MPa (79–101% of CT mortar), which indicated a further increase in the strength of the mortar due to the pozzolanic reaction. At 60 days, the GSCBA mortars development rate of the compressive strength was 41.2, 43.5, 46.4, and 47.9 MPa, or approximately 86, 91, 97, and 100% of CT mortar, respectively. It was clearly seen that the calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H), formed as a result of pozzolanic reactions, gave further binding and densification, which promoted long-term strength. Additionally, the smaller particle size of GSCBA (d50 = 6.4 μm) than that of HC (d50 = 17.7 μm) also facilitated filler effects, which enhance the packing density of the paste and fine aggregate matrix and further strength development at later ages [23,28,29,35,36,37]. In terms of the 20% pozzolanic replacement (20GSCBA mortar), must be capable of attaining at least 75% of the compressive strength of the CT mortar at 7 and 28 days, according to ASTM C618 [24]. The 20GSCBA mortar was well beyond this requirement, with 99% and 96% CT strength at these ages. The mortar entered 79% and 82% of CT mortar at 7 and 28 days, and 86% at 60 days, although the binder weighed 60% of HC only. These findings show that GSCBA can be effectively utilized as a sustainable partial cement replacement without affecting the structural performance, which has a viable potential in terms of reduction in cost and positive effects on the environment in the production of mortar and concrete.

3.3.3. Relationship Between Compressive Strength and Water Requirement of Mortar at 28 Days

Figure 7 shows the relationship between the compressive strength and water requirement of mortars, where ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) was replaced by hydraulic cement (HC), and stone dust (SD) replaced river sand (RS) in percentage after 28 days of curing. The findings show that compressive strength declines with the increment of GSCBA replacement, which implies the decline of cement content and subsequent decline in the initial pozzolanic activity [8,9,37]. The compressive strengths of mortars with 10% and 20% GSCBA replacement (10GSCBA and 20GSCBA) were nearest to the control mortar (CT), with 39.4 MPa and 38.1 MPa (99% and 96% of the CT strength) compressive strengths, correspondingly. This proves that a moderate level of GSCBA replacement can deliver almost equivalent structural performance of conventional hydraulic cement mortars, and at the same time offers environmental and economic advantages. When the relationship between compressive strength and water requirement was analyzed, it was found that the greater the water requirement, the less compressive strength. The higher GSCBA content mortars needed more water to achieve the target workability (spread flow of 110 ± 5%), and this increased the water-to-binder ratio (W/B) and minimally decreased early-age and 28-days strength [8,9,37]. Nevertheless, all the mortars with 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt% of binder replacement of GSCBA passed the compressive strength of 28 MPa at 28 days as required by Thai Industrial Standards (TIS 2594-2556) of hydraulic cement mortars [38].

Figure 7.

Compressive strength vs. water requirement of cement mortar with GSCBA and stone dust at 28-day curing.

These results highlight the feasibility of ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) as a partial substitute of the hydraulic cement. At medium replacement rates (10–20%), the compressive strength is the same as that of control mortars (CT mortar). The mixtures will satisfy structural needs even at increased replacement rates (30–40 wt% of binder), at which they will provide sustainability benefits including a lower consumption of cement and the exploitation of agricultural waste. The negative relationship that is realized between the demand for water and compressive strength is another pointer to the importance of optimization, whereby mix design must strike a balance between workability and mechanical performance. Generally speaking, this analysis proves that GSCBA can be successfully incorporated into mortar recipes without deteriorating the structural integrity, and it offers a viable and environmentally friendly scalable alternative to the construction industry [22,25].

3.4. Concrete Test Results

3.4.1. Compressive Strength of Concrete

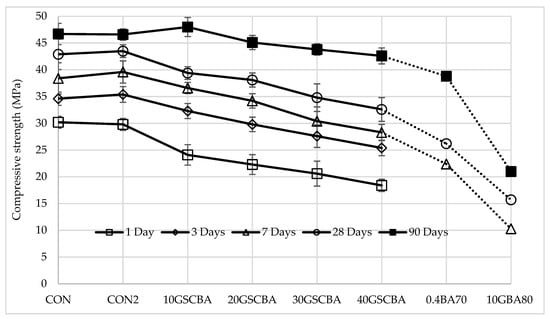

Figure 8 shows the compressive strength and age of concrete at 1, 3, 7, 28, and 90 days. The compressive strengths of the control concrete (CON) made of river sand and limestone aggregate were 30.2, 34.6, 38.4, 42.9, and 46.7 MPa, respectively. The second control mixture (CON2), whereby the river sand has been completely substituted by the stone dust whilst the limestone aggregate was maintained, showed slightly different compressive strengths of 29.8, 35.4, 39.6, 43.5, and 46.6 MPa which represents 99–103% of CON exhibiting that complete replacement of fine aggregates entirely by stone dust does not have a detrimental effect on the compressive early and late-age performance. In case of concretes supplementing ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) at 10 and 20 wt% of the binder (10GSCBA and 20GSCBA concrete) combined with stone dust, compressive strengths were similar to CON and CON2 at early ages (1–7 days). Interestingly, it was found that at 90 days, 10GSCBA and 20GSCBA concrete recorded compressive strengths of 48.0 MPa (103%) and 45.1 MPa (97%), respectively, indicating that moderate replacement of GSCBA could be used to improve compressive properties in the long-term [8,9,28,29].

Figure 8.

Compressive strength of concrete [8,39].

Nevertheless, increased levels of GSCBA replacement (30% and 40%) caused lower early compressive strength with 1- and 3-days strength of 18.4–27.6 MPa (61–80% of CON). This decrease is explained by the decreased cement content, which decreases the initial pozzolanic reaction between Ca(OH)2 generated during the hydration of cement with the SiO2/Al2O3 components of GSCBA, leading to slower initial strength gain [8,9,28,29]. The 30GSCBA and 40GSCBA concrete mixtures produced at 28.33–34.8 MPa (74–81% of CON) at 7 and 28 days and 43.8 and 42.6 MPa (94 and 91%) at 90 days. The identified late-age strength development is mostly attributed to the progressive pozzolanic reaction that develops more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), which is a binder in the concrete matrix. Moreover, the reduced average particle size of GSCBA (d50 = 6.4 μm) compared to HC (d50 = 17.7 μm) facilitates efficient filler activity, enhancing the particle packing density and microstructural compactness, which leads to the increase in long-term strength [28,29,30].

Figure 8 exhibited the compressive strength of 0.4BA70 [8] and 10GBA80 concrete [39] from the research of Chindaprasirt et al. (2020) [8] and Klathae et al. (2020) [39]. 0.4BA70 and 10GBA80 concrete had binder contents of 500 and 400 kg/m3, respectively, which was similar to this study. 0.4BA70 concrete had a W/B ratio of 0.40, and 10GBA80 had a W/B ratio of 0.45 concrete, which was close to those of all concretes in this study, which had a W/B ratio of 0.45. It should be noted that the compressive strength from this study was the similarity trend from the research of Chindaprasirt et al. (2020) [8] and Klathae et al. (2020) [39]. The overall findings indicate that the partial substitution of HC by GSCBA to a level of 20% or lower does not change or even increase the compressive strength of the material in the long-term, and, thus, the higher the degree of substitution, the more cautious should be the consideration of the water-to-binder ratios and curing measures to reach the desired compressive strength. The results herein highlight the twofold advantageous nature of GSCBA inclusion since it is possible to achieve not only the sustainable use of agricultural residues but also possible economic benefits without structural performance degradation.

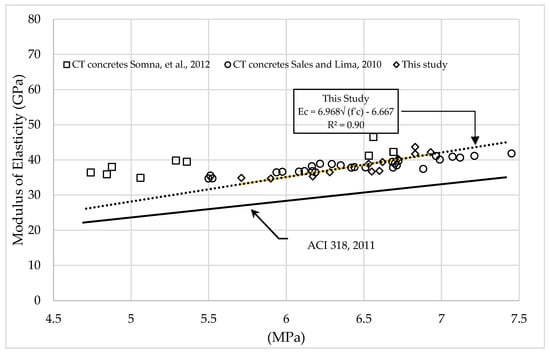

3.4.2. Modulus of Elasticity of Concrete

Figure 9 shows the correlations between the square root of compressive strength and the elastic modulus of concretes at 28 and 90 days. The control concrete (CON) had a modulus of 36.7 and 41.7 GPa, respectively, but the one in which river sand was replaced with stone dust in all rates (CON2) had a slightly higher elastic modulus of 36.9 and 43.7 GPa. This was because when fine aggregate is substituted with stone dust it can slightly improve stiffness but does not affect the performance [33,34]. An analysis predicting the relationship between the square root of the compressive strength and the modulus of elasticity showed that there is a direct relationship, i.e., concrete with higher compressive strength showed higher values of modulus. This trend is in line with the classical empirical models that have been used to correlate the elastic modulus with the compressive strength of cementitious materials [40]. The modulus of elasticity after 28 and 90 days was between 34.9 and 42.2 GPa in the case of 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA with concrete mixtures that contained ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) as a partial replacement of cement and stone dust as a total replacement of sand. The data show that a slight increase in the GSCBA content decreases the modulus of elasticity, which indicates the decrease in cement content and the subsequent early-age stiffness development. Nevertheless, the decrease is moderate, and all mixtures had the moduli in the expected range of structural concrete [39,41,42]. Comparison with the predictive ACI 318 model (Ec = 4700√f′c) indicated that most measured moduli were within ±10% of the codified values. Minor deviations occurred in mixtures with higher GSCBA content, reflecting reduced cementitious stiffness. Overall, the data confirm that compressive strength predominantly governs the modulus of elasticity, with aggregate type and GSCBA content having minimal influence. These findings demonstrate that GSCBA is a viable sustainable partial cement replacement that preserves the mechanical stiffness of concrete [40].

Figure 9.

Relationship between modulus of elasticity and square root of the compressive strength of concrete [40,41,42].

These findings illustrate that the replacement of stone dust does not have negative effects on the elastic characteristics of concrete. Compressive strength seems to dominate the modulus of elasticity and not aggregate type or ash content, which again supports the practical relevance of GSCBA as a sustainable partial cement replacement that does not affect mechanical stiffness [39,41,42].

3.4.3. Drying Shrinkage of Concrete

Figure 10 displays the drying shrinkage of concretes using ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) as a partial cement substitute and full salt replacement by stone dusts and monitored up to 120 days. The rapid of the shrinkage of all the concrete mixtures was recorded in the initial 7 days, which were then followed by a slow increment over the following 120 days, as was observed by Barr et al. (2003) who found that the drying shrinkage relied heavily on ambient relative humidity and temperature with rapid shrinkage taking place within the first 28 days and gradual increasing after 120 days [43]. The control concrete (CON), after 120 days drying shrinkage, was 359 × 10−6, and that of concrete where river sand was totally replaced by stone dust (CON2) was 394 × 10−6, showing that aggregate replacement has a slight effect on the shrinkage. In the case of concretes with GSCBA, that is, 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA, the drying shrinkage was between 452 × 10−6 and 516 × 10−6. This is attributed to the high volume of the paste in the GSCBA-modified concretes. In particular, the specific gravity of GSCBA (2.12) is much less than that of regular hydraulic cement (3.13); as a result, the volumetric content of GSCBA is greater, and the total volume of the paste is higher. When the replacement ratio of GSCBA is high, the content of paste is also increased, causing a rise in drying shrinkage. These are in line with Klathae et al. (2020), who found that the replacement of cement with biomass ash in part leads to increased early and long-term shrinkage [39].

Figure 10.

Relationship between drying shrinkage and age of concrete.

Although the values of the shrinkage were higher than those of CON and CON2, drying shrinkage of all GSCBA-containing concretes still fell within the 200–800 microstrains range of allowed shrinkage rates suggested by the ACI Committee 209, which confirms that GSCBA can be used safely as a partial cement substitute without going over the acceptable limits of shrinkages [44].

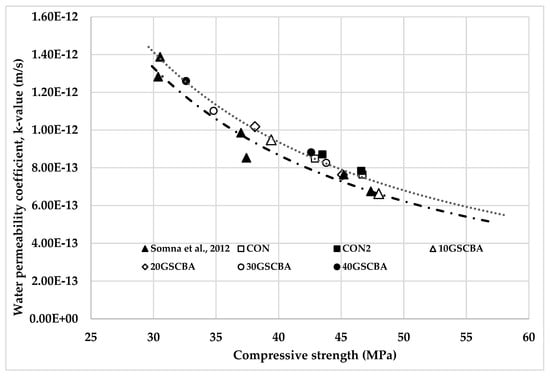

3.4.4. Water Permeability of Concrete

Figure 11 shows the correlation between the compressive strength and water permeability of the concrete mixtures, as the coefficient of water permeability (K, m/s). Control concrete (CON) had a permeability coefficient of 8.49 × 10−13 m/s after 28 days and reduced to 7.64 × 10−13 m/s after 90 days. In the case of the concrete where all river sand was replaced with stone dust (CON2), the values were a bit higher and were 8.71 × 10−13 m/s at 28 days and 7.84 × 10−13 m/s at 90 days. The permeability coefficients of concretes with 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA, which is 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% of cement substituted by stone dust (replacing river sand), were between 1.26 × 10−12 and 9.48 × 10−13 m/s at 28 days and between 8.82 × 10−13 and 6.64 × 10−13 m/s at 90 days.

Figure 11.

Relationship between the compressive strength and water permeability of concrete at 28 and 90 days [42].

These findings demonstrate that compressive strength is a major factor that governs water permeability. The concrete type was less permeable, like CON and 10GSCBA, because the microstructure was more compact and thus the connectivity between pores and water transport routes was less. On the other hand, concretes that contained more GSCBA (20–40 wt% of binder) had a reduced compressive strength by a small margin, leading to an increase in water permeability. This is in line with the earlier studies [42] that have shown that the water permeability of lower-strength concrete tends to be higher since the concrete has a less dense matrix and, also, a higher water capillary porosity. All in all, the results show a negative correlation between compressive strength and water permeability, and the GSCBA and stone dust inclusion is a good way to preserve the permeability levels at the acceptable structural usage levels.

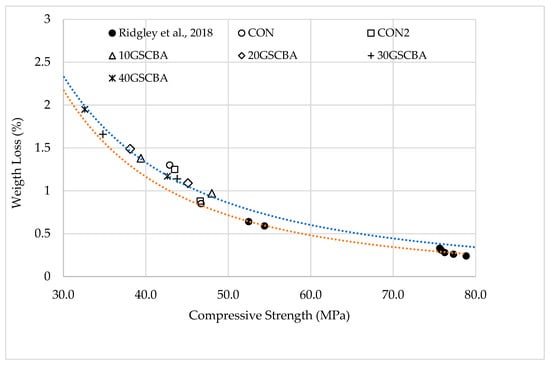

3.4.5. Abrasion Resistance of Concrete

Figure 12 illustrates the relationship between compressive strength and mass loss due to abrasion in concrete at 28 and 90 days. The control concrete (CON) exhibited average mass losses of 1.30% and 0.85% at 28 and 90 days, respectively, while the concrete in which river sand was fully replaced with stone dust (CON2) showed slightly lower mass losses of 1.25% and 0.88%. Concretes containing 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) as a partial cement replacement displayed mass losses ranging from 1.38% to 1.95% at 28 days, decreasing to 0.97–1.17% at 90 days. These results indicate a clear inverse correlation between compressive strength and abrasion susceptibility: mixtures with lower compressive strength were more prone to wear under abrasive conditions [45].

Figure 12.

Relationship between compressive strength and percent weight loss due to the abrasion of concrete [45].

The results are in line with past research, as it has been shown that the abrasion resistance tends to increase with the compressive strength [45]. In addition to this, the research offers new knowledge of the performance of sustainable concretes involving the use of agro-industrial by-products. Particularly, the addition of GSCBA as a partial cement replacement makes the mass loss at the early age a bit higher because the material is less dense, although the abrasion resistance is acceptable according to engineering standards in the long term. This fact is ascribed to the joint action of the morphology of the GSCBA particles and the increase in the packing density of the concrete matrix, contributing to the microstructural integrity and mechanical wear resistance. Notably, the findings reveal that an entirely new full sand replacement, stone dust, may enhance stiffness and packing to a minor extent and offset the possible decrease in abrasion resistance by GSCBA. In general, the results have shown that sustainable concrete with GSCBA and stone dust has the same long-term abrasion performance when compared with conventional concrete, without any reduction to its structural durability or serviceability.

Practically, these results emphasize the possible uses of GSCBA-based concrete in such situations when abrasion resistance is a major concern, like industrial flooring, pavements, and high-traffic zones. In addition, agro-industrial by-products also help to reduce the carbon footprint and promote the principles of the circular economy, proving that sustainable materials can continue to perform their functions and have an environmental and economic advantage.

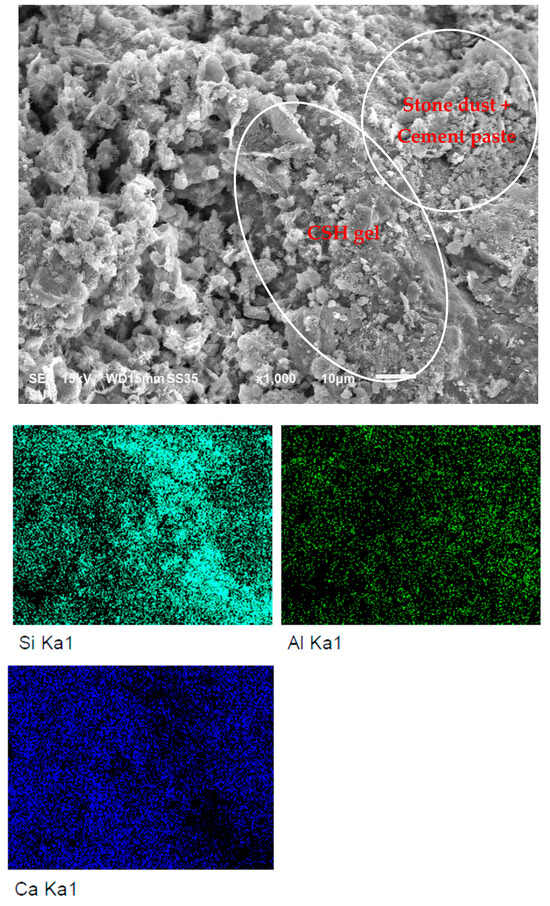

3.4.6. Microstructural Analysis of Concrete Surfaces

The control concrete (CON), under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at 1000× magnification, revealed distinct microstructural characteristics that are shown in Figure 13. Two primary regions were examined: the cement paste matrix and the embedded aggregates. The cement paste exhibited a dense, layered morphology, indicative of hydration products such as calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H), calcium hydroxide (CH), and aluminate compounds. In contrast, the aggregate phase displayed rough and angular surfaces, corresponding to unreacted fine sand (silica-rich) and limestone particles. In addition, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed that silicon (Si) was predominantly distributed within the aggregate zone, consistent with the quartz content of sand, and, to a lesser extent, present in the C–S–H gel. Aluminum (Al) was localized within the paste, suggesting the formation of hydration phases such as ettringite or monosulfate. Calcium (Ca) was highly concentrated in the cement paste, further supporting the formation of CH and C–S–H, while it was found in smaller amounts within the limestone aggregates [46,47].

Figure 13.

SEM and EDS analysis of control concrete (CON).

A concrete mix with full replacement of river sand by stone dust (CON2) showed a dense and compact microstructure under SEM observation (Figure 14). The fine and coarse particles of stone dust effectively filled the voids between cement paste particles. This led to reduced porosity, improved particle packing, and stronger bonding between the paste and the aggregates. Elemental mapping revealed that silicon was mainly present in minor amounts, while calcium was strongly concentrated in both the cement paste and the stone dust particles, consistent with the presence of calcium carbonate in the stone dust and calcium-based hydration products in the paste. Aluminum was partly distributed in the cement paste, suggesting the formation of aluminate phases during hydration. These findings highlight the dual role of stone dust in concrete: it enhances both mechanical interlocking and microstructural densification. These improvements help to explain the observed increase in compressive strength due to better particle packing and stronger bonding between the paste and aggregate [47]. These microstructural features are consistent with the enhanced strength performance observed in CON2 samples.

Figure 14.

SEM and EDS analysis of concrete with stone dust replacing river sand (CON2).

The SEM micrograph of concrete with partial replacement of cement by ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) and full replacement of river sand by stone dust (Figure 15) revealed three main regions: (i) cement paste + GSCBA, which showed a dense, fine, and slightly rough texture. This indicates active hydration combined with pozzolanic reactions, leading to the formation of C–S–H and CH gels; (ii) GSCBA particles, which displayed a rough and porous texture with some partially unreacted material, acting as an additional source of reactive silica within the matrix; and (iii) aggregates (stone dust), which filled the inter-particle voids and contributed to a denser overall structure due to their fine gradation and calcium carbonate content. Elemental mapping confirmed that Si was concentrated within the GSCBA particles and was also diffused throughout the cement paste, indicating pozzolanic reaction with Ca(OH)2. Al was mainly present in localized regions of the paste, suggesting the formation of aluminate phases within the cement matrix. Ca was widely distributed in the paste and around the aggregates, reflecting both hydration products and the calcium carbonate composition of the stone dust. The combined use of GSCBA and stone dust promoted a denser matrix and better interface between the paste and aggregate, which is consistent with the enhanced compressive strength observed in the experimental results [47].

Figure 15.

SEM and EDS analysis of concrete with stone dust replacing river sand concrete incorporating GSCBA and stone dust (40GSCBA).

The GSCBA addition to the mix led to an increase in microstructural densification through the addition of reactive silica to form pozzolanic reactions and promote the growth of C-S-H gels, increase particle packing, and decrease micro-porosity. These effects correlate well with the observed improvements in the mechanical performance of concrete containing GSCBA, particularly in the reduction in cement demand while maintaining strength. This microstructural observation will be a new input in comprehending the synergistic actions of the agro-industrial by-products and fine mineral substitutions on the concrete performance at the micro level.

Overall, the analysis of SEM and EDS shows that the optimal use of GSCBA and stone dust is not only the means of ensuring perfect microstructure integrity of concrete but also demonstrates a clear microstructural basis for the enhanced compressive strength observed in the tested mixes. The results provide a high translational significance to the industrial scale implementation in sustainable buildings that conform to the principles of the circular economy and comply with the structural performance standards.

3.4.7. Chemical Composition of Bagasse Ash and Concrete with GSCBA and Stone Dust

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was employed to determine the chemical composition of ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) and concretes with GSCBA and complete replacement of stone dust, about their possible environmental and structural effects, and adolescent heavy metal accumulation in particular. Table 7 summarizes the results. GSCBA had a high silica (SiO2) proportion of 74.54% which makes it a natural pozzolan. The reactivity of silica is high, which leads to the pozzolanic reaction with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) generated during the hydration of hydraulic cement to create calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which plays a key role in the development of concrete strength in the long term. There were significant variations in chemical composition in concrete with bagasse ash and stone dust. The level of SiO2 was reduced to about 36%, which showed the partial product of the reaction between the silica and the calcium hydroxide. Simultaneously, the percentage of the CaO content rose significantly to 45.81%, which corresponds to a total of hydraulic cement and high-calcium stone dust created by calcium carbonate. High concentration of CaO is important in the production of major hydration products like calcium silicate hydrate and calcium hydroxide that comprise the structural integrity of hardened concrete. The cementitious ratios of the SiO2 and CaO have a strong effect on the cement replacement with bagasse ash, which contributes to the increase in the mechanical strength and the long-term stability [35,36,37,39].

Table 7.

Chemical composition of GSCBA and concrete with GSCBA and stone dust.

The materials used were also analyzed using heavy metals to ensure that they were safe for the environment. XRF findings indicated there were traces of heavy metal oxides, such as Cr2O3, MnO2, CuO, ZnO, and SrO, and all of them were found in relatively low concentrations. When the data was compared with the US EPA Part 503 regulations on the application of biosolids on the land, where specifications were given on chromium of 3000 mg/kg, copper of 1500 mg/kg, zinc of 2800 mg/kg, lead of 300 mg/kg, and cadmium of 39 mg/kg, all measured values were well below the thresholds [48]. Namely, Cr2O3 was 0.019 to 0.047% (190 to 470 ppm), and ZnO was 0.03% (300 ppm). This confirms that the materials are safe for use in environmentally sensitive applications such as agricultural concrete surfaces (e.g., rice-drying yards), without posing a risk of heavy metal accumulation. Although leaching behavior under field conditions was not assessed in this study, the very low concentrations of heavy metals detected suggest a low risk of environmental contamination. To strengthen this conclusion, further investigation into leaching potential using standard tests (e.g., TCLP or EN 12457 [49]) is recommended for future studies. The sustainable design of bagasse ash and stone dust concrete is also sustained by the chemical composition. GSCBA is a reactive pozzolan, which increases the long-term strength by creating calcium silicate hydrate. Its low level of heavy metals makes it environmentally safe, whereas the high level of calcium oxide in mixtures of GSCBA stone dust enables the formation of strong hydration products. This combination of properties enhances the working performance and durability of the product, and this proves the feasibility of agro-industrial by-products in the construction industry. This will help us use resources efficiently and promote principles of the circular economy, as well as provide safer infrastructure to serve agricultural purposes [47].

3.4.8. Environmental Assessment and Economic Benefits Comparisons

Figure 16 presents the compressive strength, total cost, and CO2e emissions per cubic meter of concrete. The production cost of 1 m3 of concrete was calculated using the following unit prices (Table 2): hydraulic cement (HC) 0.075 USD/kg [19], GSCBA 0.015 USD/kg (including transportation, labor, and milling energy within 200 km) [9], river sand 0.015 USD/kg [9], water 0.0009 USD/kg [9], stone dust 0.007 USD/kg [20], coarse aggregate (crushed limestone) 0.016 USD/kg [9], and superplasticizer (Type F) 1.00 USD/kg [9]. The control concretes (CON and CON2) cost 60.23 and 55.83 USD/m3, respectively. In contrast, the concretes incorporating GSCBA with stone dust (10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA) had lower production costs of 53.25, 51.66, 49.03, and 47.45 USD/m3, corresponding to 88, 86, 81, and 79% of the CON cost. These results demonstrate a significant economic benefit associated with the adoption of GSCBA as a supplementary cementitious material.

Figure 16.

Comparisons between the compressive strength of concrete at 90 days, the total cost/m3 and the total CO2e/m3 of concrete.

The total CO2 emissions per cubic meter (CO2e/m3) of CON were 382 kg, while CON2, 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA concretes emitted 382, 339, 312, 284, and 257 kg CO2e/m3, respectively, equivalent to 96, 89, 82, 74, and 67% of the CO2e of the control concrete. The CO2 emission factors used in this study were derived from published LCA-based databases and regional studies [9,19,20]. The factor for hydraulic cement (0.82 kg CO2/kg) represents the average value from Southeast Asian cement production, while the GSCBA factor (0.18 kg CO2/kg) accounts for drying and grinding energy based on biomass ash utilization processes. Although these are secondary data, they were selected to reflect realistic local production and transportation conditions, ensuring comparability among mixtures. The results indicate a linear decline in CO2 emissions with increasing GSCBA content, corresponding to reductions of 4–33% relative to conventional HC-based concrete.

At 90 days, the compressive strengths of CON and CON2 were 46.7 and 46.6 MPa, respectively, with CO2e intensities of 8.18 and 7.86 kg CO2e/MPa. The CO2e intensity values for 10GSCBA, 20GSCBA, 30GSCBA, and 40GSCBA concretes were 7.05, 6.91, 6.48, and 6.02 kg CO2e/MPa, respectively. These results confirm that partial replacement of HC with GSCBA, particularly when combined with stone dust, can reduce CO2 emissions without compromising long-term compressive strength.

Overall, the findings highlight the dual advantage of incorporating GSCBA: it enables sustainable utilization of agricultural residues and delivers economic benefits, while maintaining or even enhancing structural performance. For substitutions beyond 20%, careful adjustment of the water-to-binder ratio and curing regime is necessary to achieve the desired compressive strength.

4. Conclusions

This experiment investigated the eco-friendly use of the ground sugarcane bagasse ash (GSCBA) in place of hydraulic cement (HC) and limestone dust (SD) in place of river sand in mortar and concrete as a partial and total replacement, respectively. It was reported that the synergies between GSCBA and HC had a strong impact on the chemical, physical, and mechanical performance of the blended systems, which justify their abilities in eco-efficient construction applications.

The results of the characterization proved that HC with CaO-rich and dense particles facilitates the nucleation of hydration products and mechanical interlocking, whereas GSCBA, containing reactive SiO2 and having a porous morphology, increases the pozzolanic reactivity and pore structure refinement, and decreases the content of free lime. The combination of these mechanisms enhances durability and microstructural integrity, which is aligned to the goals of the circular economy and low-carbon construction.

It was experimentally determined that the addition of GSCBA to a maximum of 20 wt% has similar compressive strength properties as regular HC mortar and concrete, with almost 99% of the control strength after 28 days. Still higher replacement levels (30–40 wt%) were found to be compliant with TIS 2594-2556, but exhibited a significantly reduced early-age strength and somewhat higher permeability. Thus, it is possible to accept 40 wt% as the maximum limit of the GSCBA use, which is appropriate for the elements that are not structural or that have low loads. In the case of structural-grade concrete, it is advised that the level of substitution reaches 20 wt% to maintain the balance between the strength, serviceability, and sustainability.

In addition, SEM-EDS microstructural analyses evidenced a well-integrated matrix with reduced porosity and enhanced particle packing due to active pozzolanic reactions and filler effects. Cost and environmental performance assessments revealed that GSCBA incorporation can reduce concrete production cost by up to 21% and lower CO2 emissions by 8–33%. Furthermore, trace heavy metal contents in both GSCBA and GSCBA–SD concretes were well below regulatory thresholds of U.S. EPA Part 503 and hence are assured to be environmentally safe for sensitive applications.

The durability tests, including drying shrinkage, water permeability, and abrasion resistance, have also shown that GSCBA-modified concretes possess sound engineering performance due to microstructural densification and improved resistance to mechanical wear and chemical ingress.

Overall, the findings establish GSCBA as a sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally responsible supplementary cementitious material capable of reducing the construction sector’s carbon footprint. The research contributes novel insights into the reaction kinetics, morphology–performance relationships, and microstructural evolution of blended cementitious systems. Future work should focus on optimizing curing regimes, assessing long-term durability under field conditions, and developing predictive models for GSCBA-based concrete to facilitate broader industrial implementation.

Author Contributions

P.K.: data curation, conceptualization, writing—original draft; T.K.: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, methodology; M.M.: validation, writing—review and editing; K.S.: visualization, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded by National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), Contract No. N81A670574. Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya for their cooperation and support in field coordination.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the Faculty of Engineering, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Pathum Thani, Thailand, during the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CO2e | Carbon dioxide equivalents |

| CON | Control concrete + River Sand |

| CON2 | Control concrete + Stone dust |

| CT | Control mortar + River Sand |

| CT2 | Control mortar + Stone dust |

| GSCBA | Ground sugarcane bagasse ash |

| k-value | Water permeability coefficient |

| ITZ | Interfacial transition zone |

| OSCBA | Original sugarcane bagasse ash |

| RS | River sand |

| SD | Stone dust |

| SP | Superplasticizer |

| USD | United States dollar |

References

- Bahurudeen, A.; Santhanam, M. Influence of different processing methods on the pozzolanic performance of sugarcane bagasse ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 56, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Rajagopal, K.; Thangavel, K. Evaluation of bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.S.; Amario, M.; Stolz, C.M.; Figueiredo, K.V.; Haddad, A.N. A comprehensive review of stone dust in concrete: Mechanical behavior, durability, and environmental performance. Buildings 2023, 13, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Chohan, I.M.; Alwetaishi, M.; Waheeb, S.A.; Alkhattabi, L. Sustainability assessment and mechanical characteristics of high-strength concrete blended with marble dust powder and wheat straw ash as cementitious materials by using RSM modelling. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 39, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Zhang, B.; Ahmad, M.; Niekurzak, M.; Khan, M.S.; Sabri, M.M.; Chen, W. Optimizing concrete sustainability with bagasse ash and stone dust and its impact on mechanical properties and durability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elawadly, N.; Sanad, S.A. Sustainable concrete incorporating sugarcane bagasse ash: A study on workability, mechanical behavior, and microstructure. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, T.A.; Koteng, D.O.; Shitote, S.M.; Matallah, M. Mechanical properties of eco-friendly concrete made with sugarcane bagasse ash. Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 8, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; Kroehong, W.; Damrongwiriyanupap, N.; Suriyo, W.; Jaturapitakkul, C. Mechanical properties, chloride resistance and microstructure of Portland fly ash cement concrete containing high volume bagasse ash. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klathae, T.; Tran, T.N.H.; Men, S.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Tangchirapat, W. Strength, chloride resistance, and water permeability of high-volume sugarcane bagasse ash high-strength concrete incorporating limestone powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 311, 125326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1157; Standard Performance Specification for Hydraulic Cement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C39/C39M; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM C469/C469M; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ASTM C78; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM C157/C157M; Standard Test Method for Length Change of Hardened Hydraulic-Cement Mortar and Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2005.

- ASTM C944; Standard Test Method for Abrasion Resistance of Concrete or Mortar Surfaces by the Rotating-Cutter Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM C1202; Standard Test Method for Electrical Indication of Concrete’s Ability to Resist Chloride Ion Penetration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment: Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment: Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- RISC Knowledge Center. How Hydraulic Cement Reduces Global Warming. 2023. Available online: https://risc.in.th/en/knowledge/how-hydraulic-cement-reduces-global-warming (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, H.; Ye, F.; Lei, Z. Research on carbon emission reduction of manufactured sand concrete based on compressive strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 133101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, M.; Woyciechowski, P.; Sokołowska, J. Effect of mechanically-induced fragmentation of polyacrylic superabsorbent polymer (SAP) hydrogel on the properties of cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 4th ed.; Longman: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Fairbairn, E.M.R. Effect of calcination temperature on the pozzolanic activity of Sugarcane bagasse ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 3301–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J. Concrete Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: https://repositori.mypolycc.edu.my/jspui/handle/123456789/4614 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Gedam, B.A.; Singh, S.; Upadhyay, A.; Bhandari, N.M. Improved durability of concrete using supplementary cementitious materials. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies, London, UK, 14–17 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zabade, G.; Ngekpe, B.E.; Zab, I.; Akobo, S. Mechanical and durability properties of rice husk ash blended concrete. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2022, 13, 419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Chusilp, N.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kiattikomol, K. Utilization of bagasse ash as a pozzolanic material in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 3352–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukzon, S.; Chindaprasirt, P. Utilization of bagasse ash in high-strength concrete. Mater. Des. 2012, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdane, R.; Kherraf, L.; Assia, A.; Belachia, M. Influence of biomass ash on the performance and durability of mortar. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2022, 32, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C33-97; Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1997.

- ASTM C128-15; Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Fine Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM C136-01; Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2001.

- ASTM C117-95; Standard Test Method for Materials Finer than 75-μm (No. 200) Sieve in Mineral Aggregates by Washing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1995.

- Sata, V.; Tangpagasit, J.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effect of W/B ratios on pozzolanic reaction of mortars containing biomass ashes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangchirapat, W.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kiattikomol, K. Compressive strength and expansion of blended cement mortar containing palm oil fuel ash. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2009, 21, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroehong, W.; Sinsiri, T.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effect of palm oil fuel ash fineness on the microstructure of blended cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 4095–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIS 2594-2556; Hydraulic Cement. Thai Industrial Standards Institute: Bangkok, Thailand, 2013.

- Klathae, T.; Tanawuttiphong, N.; Tangchirapat, W.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Sukontasukkul, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C. Heat evolution, strengths, and drying shrinkage of concrete containing high-volume ground bagasse ash with different LOIs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258, 119443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 318; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2011.

- Sales, A.; Lima, S.A. Use of Brazilian sugarcane bagasse ash in concrete as sand replacement. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somna, R.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Rattanachu, P.; Chalee, W. Effect of ground bagasse ash on mechanical and durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Mater. Des. 2012, 36, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, B.; Hoseinian, S.B.; Beygi, M.A. Shrinkage of concrete stored in natural environments. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee 209; Report on Factors Affecting Shrinkage and Creep of Hardened Concrete. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2005.

- Ridgley, K.E.; Abouhussien, A.A.; Hassan, A.A.; Colbourne, B. Assessing abrasion performance of self-consolidating concrete containing synthetic fibers using acoustic emission analysis. Mater. Struct. 2018, 51, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachideh, G.; Gholhaki, M.; Ketabdari, H. Effect of pozzolanic wastes on mechanical properties, durability and microstructure of cementitious mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankhaje, E.; Kim, T.; Jang, H.; Kim, C.-S.; Kim, J.; Rafieizonooz, M. A review of utilization of industrial waste materials as cement replacement in pervious concrete: An alternative approach to sustainable pervious concrete production. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 40 CFR Part 503; Standards for the Use or Disposal of Sewage Sludge. United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1993.

- EN 12457-2; Characterisation of Waste—Leaching—Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges. European Committee for Standardization: London, UK, 2002.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).