1. Introduction

As traction substations serve as energy-conversion hubs in the power system, their operating status directly determines the stability and safety of the entire power supply [

1]. The grounding system, as a core component of substation facilities, has the dual functions of equipment grounding and safety protection. Through a network of metal conductors, it establishes a reliable equipotential connection between the on-site facilities and the earth. This not only safeguards the stable operation of the power system but also effectively reduces the risk of electric shock to humans and thus serves as a crucial foundation for the safe and efficient operation of substation facilities [

2,

3,

4].

In recent years, substation burnout accidents have occurred frequently. Investigations have found that abnormal grounding grids are the root cause of such accidents [

5,

6,

7].

The root cause of the vast majority of grounding-grid failures is the corrosion of grounding grids. Since the grounding-grid conductors are buried underground for long periods, their diameter gradually decreases under the continuous influence of factors such as the humid soil environment and corrosive substances in saline–alkali soil. According to research conducted in China and internationally, the annual corrosion rate of some soils can reach 2.1 mm/year, and in more severe cases, the annual corrosion rate can reach 7.99 mm/year [

8]. When a branch of the grounding grid is corroded, the resistance of that branch increases significantly, which in turn leads to a rise in the grounding resistance of the entire grounding grid, resulting in reduced grounding performance and weakened current-discharge capacity [

9]. Changes in ground resistance not only affect the potential distribution of the existing power grid but also alter the distribution of the surface magnetic field, potentially leading to accidents or injuries [

10]. Under such circumstances, the flow of current is likely to cause a localized potential rise that not only damages electrical equipment but also poses a serious threat to the safety of staff [

11,

12,

13].

Since grounding grids are deeply buried underground, information on their status is difficult to obtain directly. Currently, indirect evaluation mainly relies on electrical and magnetic signals. Common characteristic signals include grounding-grid resistance, variation in earth potential, maximum touch voltage, and maximum step voltage [

14,

15,

16]. Previously, the potential-drop method was used to assess the condition of grounding grids. However, this method requires circuit disconnection, making it unsuitable for monitoring live substations [

17]. Subsequently, researchers began evaluating grounding-grid status based on ground resistance values. While this approach is simple and direct, it is not well suited to localized detection of corrosion within the grounding grid [

18]. Researchers in [

19] evaluated the condition of grounding grids by measuring transient magnetic fields at the ground surface, achieving good results. However, this study measured only the magnetic field distribution across the entire observation surface, and the conclusions are largely qualitative and thus cannot provide further explanations based on actual data. The authors in reference [

20] investigated the grounding methods for overhead lines or transformer neutral points, as well as the fluctuations in grounding-grid potential under multiple current-injection conditions during ground faults. This method exhibits an ideal response to external faults, mainly due to the interconnection properties of grounding conductors. Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine the specific fault location when a ground fault or breakage occurs in internal conductors. Therefore, some scholars have analyzed the potential changes that occur when grounding impedance decreases using the finite element method, verifying the feasibility of replacing the actual conductor radius with an equivalent radius [

21]. However, this method still has certain limitations: relying solely on potential variation makes it impossible to accurately locate the specific position of a grounding-conductor fault. Some researchers have identified integrity failures in the grounding grid by establishing grounding-grid models and calculating contact resistance and voltage [

22,

23]. However, treating the entire grid as a single flat plate makes it difficult to identify local faults.

The electromagnetic field analysis method can relatively intuitively detect corrosion faults in grounding grids. Its principle mechanism involves injecting current into a conductor that connects the grounding grid to the ground, which induces an electromagnetic field on the ground surface above the grounding grid. Then, the surface electromagnetic field signals are collected and the relationship between the distribution of the surface electromagnetic field and the corrosion or breakage faults in the grounding grid is thus analyzed. This method does not require consideration of the structural design of the grounding grid, but it has obvious limitations: it involves the need to arrange a large number of monitoring points for the electromagnetic field, is vulnerable to interference from the internal electromagnetic environment of the substation, and has high requirements for the accuracy of the equipment used to monitor the electromagnetic field. F.P. Dawalibi, was the first to discover the characteristics of the electromagnetic field of grounding grids; they later developed CDEGS software (

https://www.sestech.com/en/Product/Package/CDEGS (Accessed on 6 November 2025)) [

24,

25]. This software is currently recognized worldwide for grounding-grid electromagnetic field simulation. To reduce the impact caused by power-frequency current, some scholars have changed the injected current to a different-frequency current [

26,

27]. In addition to the steady-state research on the electromagnetic field of grounding grids, some scholars have studied the transient characteristics of grounding grids using antenna theory [

28]. Scholars at home and abroad have used the transient characteristics of the grounding-grid electromagnetic field to study fault-state diagnosis methods and conducted effective analyses using relevant simulation software [

29,

30]. Therefore, some scholars have investigated the characteristics of variation in grounding resistance in grounding grids under the influence of impulse currents, as well as the patterns of current variation during fault occurrence, in order to further pinpoint specific fault locations [

31].

This paper combines the finite-element electromagnetic analysis method with CDEGS simulation software and, in addition to the conventional overall observation plane, simultaneously observes the electromagnetic changes along conductor lines and at discrete observation points. By classifying the conductors, the paper examines the variation patterns of three types of electromagnetic field observation results under different fault severities. It then derives a method that can effectively analyze fault locations for grounding conductors and proposes an optimized distribution scheme for the observation points of the grounding grid based on these results.

Research findings indicate that under normal conditions, the surface magnetic field exhibits a symmetrical distribution. When a conductor experiences corrosion failure, the magnitude of the surface magnetic field at each monitoring point on the grounding grid changes. The monitoring point with the highest rate of change will be that located nearest to the corroded conductor. Under mild corrosion, the maximum rate of change reaches 30%. As corrosion severity increases, this rate further escalates to a maximum of 275%. By selecting a reference conductor and utilizing the characteristics of the variation in the magnetic field of parallel and perpendicular conductor branches, the location of the corrosion can be pinpointed. Furthermore, this paper analyzes patterns of variation in the magnetic field to eliminate monitoring points with negligible impact, thereby reducing costs. Finally, it proposes an evaluation method using Manhattan distance to assess the corrosion status of grounding grids. Compared to traditional methods such as the potential-drop method and impedance measurement, this approach achieves higher measurement accuracy without affecting the existing grounding grid during the installation of monitoring points. It can also be used in conjunction with conventional methods. Leveraging the characteristics of the transient magnetic fields generated under pulsed current allows localized corrosion to be precisely located. Furthermore, costs associated with distributed monitoring are reduced through conductor classification and the elimination of monitoring points, with minimal impact on results.

3. Grounding-Grid Corrosion and Breakage Localization

3.1. Algorithm Research

The conversion of the 2-9-4-11 branches in the grounding-grid model shown in

Figure 6 to a circuit model is shown in

Figure 7.

In the figure,

Cg2, Cg4, Cg9, and

Cg11 denote the capacitance to ground of each branch, and

C9-11 and

C2-4 denote the phase-to-phase capacitance of the two branches. Therefore, the injected current can be expressed as in Equation (20):

Iinput denotes the current injected along the reference conductor, while Ioutput denotes the current flowing out along the reference conductor. Ig denotes the total leakage current to ground.

The impedance matrix of a unit can be established as in Equation (21):

After the impedance matrix has been extended to the entire grounding network, its impedance matrix is expressed in terms of

Zb. The final transformation into the node impedance matrix

Z establishes the Equations (22) and (23):

where

Jn is the node current injection and

Vn is the voltage at that node. This represents the portion of the circuit that is used for the injected current.

Vx and

Vy denote the node voltages in the

x and

y directions, respectively.

Thus, the electromagnetic field for a particular branch can be expressed in Equation (24):

In the above equation, the first term represents the magnetic field generated by the injected current and the second term represents the magnetic field generated by the earth current in the soil. It can be seen that, with the injected current remaining constant, corrosion and breakage reduce the equivalent radius of the material, which in turn increases the resistance value, thereby reducing the magnetic field generated in this branch. However, the magnetic field generated by the leakage current is not affected by changes in resistance and remains unchanged. When a breakage fault occurs in a branch, since the resistance approaches infinity, the only magnetic field generated by this branch at this time is the soil electromagnetic field.

The electromagnetic field on one branch is affected not only by its own electromagnetic field but also by all surrounding branches. Based on the distance between conductors, we classify each branch into one of two categories according to the intensity of the electromagnetic field acting on the conductor:

a. Parallel branches, i.e., branches parallel to the location of the branch, are assumed to be m in total. The total electromagnetic field can be expressed as in Equation (25):

b. Vertical branches, i.e., branches perpendicular to the location of this branch, are assuming to number

n, and the total EMF can be expressed as in Equation (26):

Combining the two cases above, the total magnetic field is expressed in Equation (27);

Assuming a neighboring branch distance of 10 m, a parallel conductor at a distance of 20 m contributes only one-eighth the effect of the neighboring conductor; the influence of conductors at greater distances is even weaker, so the influence of conductors outside the 20 m radius can be ignored. Similarly, for vertical branches, only up to four connected branches are considered. This reduces the total number of branches of both types, simplifying the calculation.

3.2. Simulation Analysis

The surface magnetic field distribution of the grounding network under no-fault conditions is simulated, and the observation results are shown in

Figure 8; from the figure, it can be seen that the branch magnetic field along the x-axis is significantly stronger than the branch magnetic field along the y-axis. The strength of the magnetic field is much greater along the x-axis where current is injected than it is on the other x-axis, and the overall distribution of the magnetic field shows symmetry.

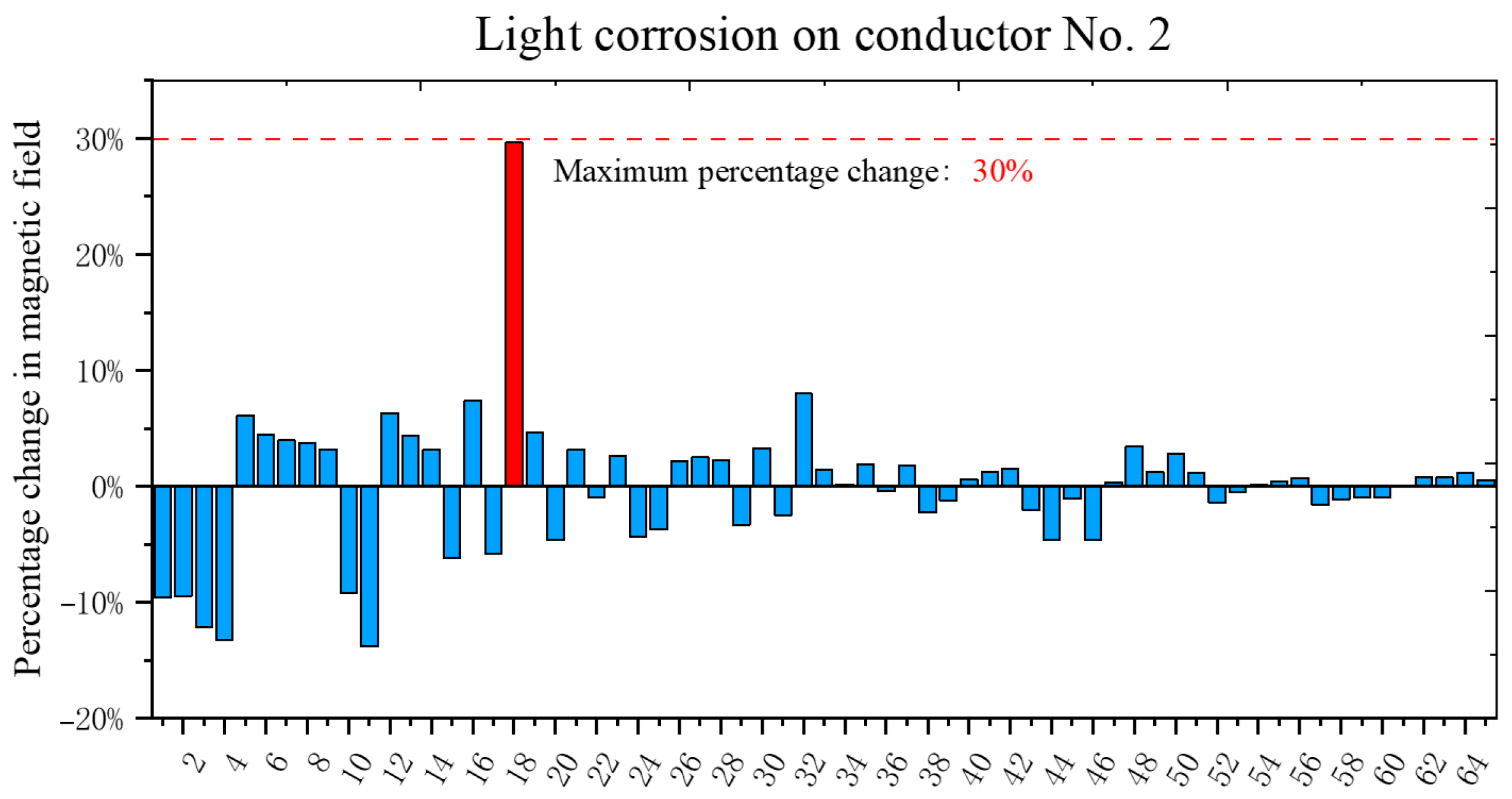

The percent change in magnetic-field strength at each point when mild corrosion occurs in Conductor No. 2 is shown in

Figure 9. Blue indicates the magnitude of magnetic field variation at each point, while red indicates the point with the greatest magnetic field variation.

Here, points 1, 3, 4, 11 and 18 have a variation of more than 10%, while Point 18 shows the largest variation, at 30%.

The percent change in magnetic field at each point when moderate corrosion occurs in Conductor No. 2 is shown in

Figure 10. Blue indicates the magnitude of magnetic field variation at each point, while red indicates the point with the greatest magnetic field variation.

It can be observed that here, points 3, 4, 11, 18, and 32 change by more than 40%, with Point 18 showing the largest change, at 108%.

When Conductor No. 2 undergoes a corrosion fracture, the magnitude of the change in magnetic field at each point is shown in

Figure 11. Blue indicates the magnitude of magnetic field variation at each point, while red indicates the point with the greatest magnetic field variation.

Here, Points 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 18, 30, 32, and 34 change by more than 50%; Point 18 shows the largest change, at 275%.

The comprehensive simulation results above represent the effects of light corrosion, moderate corrosion, and corrosion fracture in the conductor; the effects on the grounding-network surface magnetic field distribution are shown to be basically similar, but the more serious the corrosion of the conductor, the greater the degree of change in the surface magnetic field. This correlation indicates that the degree of corrosion significantly affects both the magnitude of the surface magnetic field size and its distribution.

3.3. Impact of Damage to Parallel Branches

This section analyzes the situations in which a corrosion fracture occurs in Conductors No. 4, 5, or 6, which are parallel branches of Conductor No. 2.

The magnitude of the change in magnetic field that occurs at each point when light corrosion occurs in Conductor No. 4 is shown in

Figure 12. Blue indicates the magnitude of magnetic field variation at each point, while red indicates the point with the greatest magnetic field variation.

Here, only point 18 changes more by than 10%, to −13%.

The magnitude of change in the magnetic field at each point when light corrosion occurs in Conductor No. 5 is shown in

Figure 13.

Here, there is no point where the magnetic field changes, indicating that light corrosion in Conductor 5 has no effect on the distribution of the surface magnetic field. Since Conductor 5 is located in the center of the grounding network, its impedance structure resembles a bridge, so the amplitude of the current flowing through the conductor is minimally affected by small unbalanced impedances and its thus basically unaffected by corrosion.

For further verification, we also measured Conductor No. 6. The magnitude of the change in magnetic field at each point that results when light corrosion occurs in Conductor No. 6 is shown in

Figure 14.

It can be observed that here, there are no points at which the magnetic field changes, indicating that light corrosion in Conductor 6 also has no effect on the surface magnetic field distribution.

Conductors No. 2, 4, 6 are the closest to the center of the injected current. Under conditions of light corrosion, changes in the magnetic field along the observation line are small and amplitude variations are relatively small and symmetrical.

Based on statistics describing the magnetic field at its various points, it can be seen that when corrosion occurs in Conductor No. 2, the magnetic field at monitoring points 1 to 5 decreases and the magnetic field at points 6 to 9 increases, with monitoring point 18 showing the greatest magnitude of change. The degree of change in the magnetic field decreases with distance from the fault point. A comparison of the diagrams showing the changes in magnetic field for No. 2 and No. 4 is shown in

Figure 15. Red indicates that when conductor No. 2 experiences light corrosion, the magnetic field variation at this point reaches its maximum value; Pink indicates that when conductor No. 4 experiences light corrosion, the magnetic field variation at this point reaches its maximum value.

As can be seen from the figure, the change in magnetic field at each point occurs by column. When Conductor No. 2 undergoes light corrosion, in the first column of monitoring points, Points 1 to 4, the strength of the magnetic field decreases; in the second column of monitoring points, points 5 to 9, the strength of the magnetic field increases; at points 11 and 12, the strength of the magnetic field decreases; at points 13 to 15, the strength of the magnetic field increases. In the third column of monitoring points, the maximum change in the strength of the magnetic field occurs at point 18. The first two columns show opposite-direction changes in the strength of the magnetic field when Conductor No. 4 and Conductor No. 2 undergo light corrosion. The third column of monitoring points also shows maximum values. In the fourth and fifth columns, the strength of the magnetic field changes in the same direction.

Therefore, we conclude that a grounding network is divided into left and right zones, where the corrosion of the conductor in one zone will not affect the other zone. If corrosion occurs in a conductor in the same zone, the grounding network can be again divided into upper and lower parts. In this case, changes in the strength of the magnetic field in the first and third columns will occur along the center line, while in the second column, the changes in the strength of the magnetic field occur in the vicinity of the corroded conductor. By combining the points with maximum change in the amplitude of the magnetic field, you can obtain a cross-shaped pattern of branches corresponding to the location of the corroded conductor.

For further verification, we take Conductors No. 1 and No. 3 as a comparison, and the results are shown in

Figure 16. Based on those results, the change characteristics are the same as in the first two columns in the left zone. Since Conductors No. 1 and No. 3 are located in the topmost part of the grounding network, the magnetic field does not change at the lowest monitoring point. The point at which maximum change occurs remains in the third column, corresponding to the centerline of the grounding network, but its position has been shifted upward to be closer to the corroded conductor. At the same time, in the second column, the 10th and 11th monitoring points show opposite-direction changes in the strength of the magnetic field near the corroded conductor. The 16th monitoring point exhibits the largest amplitude change, producing a cross pattern corresponding to Conductors No. 1 and No. 3. Red indicates that when conductor No. 1 experiences light corrosion, the magnetic field variation at this point reaches its maximum value; Pink indicates that when conductor No. 3 experiences light corrosion, the magnetic field variation at this point reaches its maximum value.

3.4. Impact of Damage to Vertical Branches

In this section, the changes in the strength of the magnetic field under corrosion of Conductors No. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 are analyzed and discussed. The magnitudes of the changes in the magnetic field at various points when Conductor No. 7 has been subjected to light corrosion are shown in

Figure 17. Blue indicates the magnitude of magnetic field variation at each point, while red indicates the point with the greatest magnetic field variation.

Here, Points 1, 2, 10, and 16 change by more than 10%, and Point 16 exhibits the largest change, at 19%.

A noticeable change in symmetry can be observed along the magnetic field line of No. 7 by comparing the position changes of the magnetic field at points No. 7 and No. 8, as shown in

Figure 18. Red indicates that the magnetic field change at this point reaches its maximum when conductor No. 7 experiences light corrosion; pink indicates that the magnetic field change at this point reaches its maximum when conductor No. 8 experiences light corrosion.

For vertical branch conductors in the same row experiencing light corrosion, the direction of magnetic field change at each point is basically the same. In the second column, the magnetic field changes in the vicinity of the corroded conductor, but the points of maximum change point will be different, being located near one corroded conductor in the third column and near another corroded conductor for the fourth column.

The results of the comparison of the strength of the changes in the magnetic field for Conductors 7, 9, and 11 are shown in

Figure 19. In the figure, the blue box shows Points 10, 11, and 12, which correspond to the second column of monitoring points near the corroded conductor. Each monitoring point has two nearby vertical conductor branches on the left and right, and the point with the largest value change can be used as a secondary basis for judgment. The conductor branch intersecting the two points is the corroded branch. Red indicates that the magnetic field change at this point reaches its maximum when conductor No. 7 experiences light corrosion; Light purple indicates that the magnetic field change at this point reaches its maximum when conductor No. 9 experiences light corrosion; Cyan indicates that the magnetic field change at this point reaches its maximum when conductor No. 11 experiences light corrosion.

4. Optimization of Grounding Network Monitoring Locations

The simulation results for Conductors 1–12 under light corrosion, moderate corrosion, and corrosion fracture were compiled and analyzed. It was found that Points 1, 5, 12, 16, 18, 30, and 32 changed more significantly when various faults occurred. Specific changes are shown in

Table 1, where the red data represent the maximum values of the change in the amplitude of the magnetic field under the fault. Under “Fault Type”, the first word indicates the degree of failure and the number indicates which conductor failed.

From the table, it can be seen that Points 1, 5, 12, 16, 18, 30 and 32 can be used to accurately determine the type and location of the fault of the grounding network; due to the symmetry of the grounding network, so only some of the points need to be monitored for signs of corrosion. A preliminary determination of optimal point locations is shown in

Figure 20.

Since the currents through Conductors 5 and 6 are too small to produce a noticeable effect on the monitored points, the current injection method was adjusted for another round of fault localization. The new injection position is (0, 20), and the withdrawal position is (0, −20). The rest of the conditions remain unchanged. Surface magnetic field simulations were then conducted for Conductor 5 and Conductor 6 under conditions of light corrosion, moderate corrosion, and corrosion fracture, and the results were compared with the fault-free surface magnetic field under the adjusted injection positions. The results from Points 29, 39, and 40 are shown in

Table 2.

As can be seen from the table, the changes in the amplitude of the magnetic field at Points 29, 39, and 40 can clearly indicate the fault location and type (The highlighted data represents the maximum amplitude of magnetic field variation.). Here, Conductors 5 and 6 correspond to Conductors 11 and 12 in the original injection scheme, and according to the principle of symmetry, they can be effectively monitored through points 29, 37, 39, 40, and 41. The final monitoring-point installation scheme is shown in

Figure 21. The results demonstrate the rationality of the optimized design for point installation. The original 65 observation points were successfully reduced to 25 points, minimizing the need to install monitoring points.

5. Method for Grounding Grid Condition Assessment

When conducting condition assessment of a grounding grid, a comprehensive judgment must encompass its overall grounding resistance and local corrosion/breakage faults. To this end, this paper defines characteristic fault values as the performance parameters for grounding-grid condition assessment. The amplitude variation of the grounding grid’s surface magnetic field is used as the fault characteristic information and is analyzed in combination with the Manhattan distance function. Meanwhile, the Manhattan distance function is used to define the corrosion characteristic value

Mf, which is employed to characterize the cumulative effect of surface magnetic field intensity variations corresponding to the corroded conductor segments. The definition of

Mf is given by Equation (28):

where

Yi represents the intensity of the surface magnetic field at point

i in the fault-free grounding grid;

Fi represents the intensity of the surface magnetic field at point

i in the grounding grid after corrosion occurs; and

n represents the number of sampling points.

The

Mf values of a 40 × 40 mesh grounding grid under mild corrosion, moderate corrosion, and severe corrosion were calculated, and the specific values are shown in

Table 3.

It can be seen that the fault in Conductor No. 11 has the greatest impact on the grounding grid. Moreover, there is a proportional relationship between the Mf values under mild corrosion, moderate corrosion, and corrosive breakage. Through summary and calculation, it is found that the Mf value under mild corrosion is 12.53% of that under corrosive breakage and that the Mf value under moderate corrosion is 44.75% of that under corrosive breakage.

Due to the relatively complex structure of the actual grounding grid, it is difficult to simulate mild corrosion and moderate corrosion of the grid. Therefore, in the early stage, only corrosive breakage was simulated and analyzed. Based on the patterns of mild corrosion and moderate corrosion relative to corrosive breakage in the mesh grounding grid, the

Mf values of the actual grounding grid under mild corrosion and moderate corrosion can be deduced. Define

Mf1 as the

Mf value when extracting from the upper-right corner and

Mf2 as the

Mf value when extracting from the lower-right corner. Based on the calculated values of

Mf1 and

Mf2, the values given in

Table 4 can be obtained.

A grounding-grid condition-assessment method can be designed by combining the characteristic parameters and grounding resistance values, and the specific process is shown in

Figure 22.

The condition-assessment method for grounding grids combines overall assessment and fault location. The overall assessment mainly monitors the grounding resistance of the grounding grid and the corrosion characteristic values

Mf1 and

Mf2. When the grounding resistance value of the grounding grid is greater than 1 Ω, or

Mf1 > 70, or

Mf2 > 50, the grounding grid has a breakage fault. This is judged as a severe fault, and excavation and maintenance must be carried out immediately. When the grounding resistance value is greater than 200 mΩ but less than 1 Ω, or 19 <

Mf1 < 70, or 17 <

Mf2 < 50, the probability of breakage and moderate corrosion of the grounding grid is very high. The grounding grid is judged to be in a poor condition at this time, and excavation and maintenance should be planned according to specific circumstances. When the grounding resistance value is greater than 50 mΩ but less than 200 mΩ, or 0.2 <

Mf1 < 19, or 0.15 <

Mf2 < 17, the grounding grid may be suffering from moderate corrosion or mild corrosion. Under these circumstances, the grounding grid is in acceptable condition, and continuous monitoring is required to prevent further corrosion and breakage. When the grounding resistance value is less than 50 mΩ, or

Mf1 < 0.2, or

Mf2 < 0.15, the grounding grid is free of faults and judged to be in a normal condition. The judgment logic is shown in

Figure 23.

If the overall assessment determines that there is a fault in the grounding grid, the fault can be located by combining the data with the results of local detection, thereby effectively reducing the costs of excavation and maintenance. The assessment of local corrosion and breakage mainly locates faults by collecting data on the amplitude of surface magnetic field changes. Specifically, the process is as follows: first, inject a different-frequency current into the grounding grid, where the current-injection point is the center of the grounding grid and the extraction points are at the upper-right corner and lower-right corner. After injecting the different-frequency current, collect the surface magnetic field signals acquired by the fluxgate sensors installed on the ground surface and compare these signals with the previously stored surface magnetic field signals from the grounding grid in the fault-free state. Fault location is achieved as a result.

6. Conclusions

Since the grounding grid of a substation needs to be buried underground for a long time and usually covers a large area, it is often difficult to accurately determine the positions of local corrosion and breakage. In such cases, the entire grounding grid has to be replaced, which not only wastes a large quantity of human and material resources but also affects the normal operation of the electric traction system. Studies have shown that when a different-frequency current is passed through the grounding grid, a different-frequency magnetic field can be generated on the ground surface. When a section of the conductor in the grounding grid suffers from corrosion and breakage faults, the ground surface magnetic field changes accordingly. Based on this principle, the corrosion and breakage faults of the grounding grid can be located. This paper studies the localization of corrosion and breakage and the condition assessment of substation grounding grids and draws the following conclusions:

(1). The structure of a substation grounding grid is usually approximately symmetric, and the distribution of the surface magnetic field generated during normal operation also exhibits corresponding symmetric characteristics. When a conductor in the grounding grid is corroded, this inherent magnetic field symmetry is disrupted, and this regular change can serve as a key basis for locating the fault in the grounding grid. It should be noted in particular that there is a special case: for conductors located on the perpendicular bisector of the injected current, due to the influence of the bridge effect, only an extremely weak current flows through such conductors. Therefore, even if such conductors suffer from corrosion and breakage faults, the magnetic field changes caused by the faults are very slight, making it difficult to effectively identify the fault characteristics.

(2). When a conductor of the grounding grid perpendicular to the direction of the injected current suffers from corrosion and breakage faults, it will directly disrupt the original balanced state of the magnetic field distribution along the observation line. For the deployed observation points, with the center line of the injected current as the boundary, the direction of change in the strength of the magnetic field at each column of observation points within a zone should remain consistent. If the direction of change in the strength of a magnetic field at a certain column of observation points does not conform to this rule, then the corroded conductor is most likely located in the area adjacent to this column of observation points. The observation point with the largest amplitude of change in the strength of the magnetic field is usually closest to the corroded conductor.

(3). When a conductor parallel to the direction of the injected current suffers from corrosion and breakage faults, the distribution of the magnetic field along the observation line will also become unbalanced. As in Conclusion (2), by analyzing the direction of magnetic field change at each column of observation points on non-center lines, specific observation points where the change in the strength of the magnetic field does not conform to the rule can be located. Since the conductors in the grounding grid that are perpendicular to the current direction are arranged horizontally, the observation points with abnormal changes in the magnetic field can directly correspond to the positions of the corresponding horizontal conductors. On this basis, by further combining the position of the observation point with the largest amplitude of change in the magnetic field and conducting spatial correlation analysis on these key points, conductors potentially affected by corrosion faults can be identified.

(4). It can be seen from the simulation results different fault locations and degrees in the grounding grid have significantly different effects on the surface magnetic field distribution. For example, the amplitude of the change in the magnetic field at some observation points when a fault occurs is relatively large; such points can be used as core monitoring points to realize effective monitoring of corrosion and breakage faults in the grounding grid. At the same time, by utilizing the characteristic that the distance between adjacent vertical conductors is small, a single observation point can be used to cover the area that originally required monitoring by four points, which greatly improves monitoring efficiency. Combined with the analysis of data with the most significant change in the strength of the magnetic field under various fault scenarios, after further optimization and adjustment, the initial 65 observation points can be finally streamlined to 25, which significantly reduces the cost at the actual engineering installation stage.

(5). By combining the optimized placement of monitoring points with the simulation results, a method for grounding-grid condition assessment was designed. This method is divided into two parts: overall assessment and fault location. The overall assessment mainly assesses two key parameters, namely the grounding resistance value and the corrosion characteristic value Mf, to construct a comprehensive assessment model and classifies the grounding-grid conditions into four levels: normal condition, acceptable condition, poor condition, and severe fault. When the overall assessment determines that there is a fault in the grounding grid, the fault is located by monitoring the variation in the amplitude of the surface magnetic field.