Abstract

Conventional innovation management methodologies (IMMs) often struggle to respond to the complexity, uncertainty, and cognitive diversity that characterise contemporary innovation projects. This study introduces Innovation Flow (IF), a human-centred and adaptive framework grounded in Flow Theory and enhanced by Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI). At its core, IF operationalises Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs)—adaptive variations of established methods tailored to project genetics and team profiles, generated dynamically through a GenAI-based system. Unlike traditional IMMs that rely on static toolkits and expert facilitation, Innovation Flow (IF) introduces a dynamic, GenAI-enhanced system capable of tailoring techniques in real time to each project’s characteristics and team profile. This adaptive model achieved a 60% reduction in ideation and prototyping time while maintaining high creative performance and autonomy. IF thus bridges the gap between human-centred design and AI augmentation, providing a scalable, personalised, and more inclusive pathway for managing innovation. Using a mixed-methods design that combines grounded theory with quasi-experimental validation, the framework was tested in 28 innovation projects across healthcare, manufacturing, and education. Findings show that personalisation improves application fidelity, engagement, and resilience, with 87% of cases achieving high efficacy. GenAI integration accelerated ideation and prototyping by more than 60%, reduced dependence on expert facilitators, and broadened participation by lowering the expertise barrier. Qualitative analyses emphasised the continuing centrality of human agency, as the most effective teams critically adapted rather than passively adopted AI outputs. The research establishes IF as a scalable methodology that augments, rather than replaces, human creativity, accelerating innovation cycles while reinforcing motivation and autonomy.

1. Introduction

Innovation management is undergoing a profound transformation as organisations seek to adapt to increasingly complex, uncertain, and fast-changing environments. Traditional methodologies, though valuable, often fail to accommodate the cognitive diversity of teams and the contextual specificity of projects [1]. In this context, the emergence of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) presents both an opportunity and a challenge for innovation practice. On one hand, GenAI offers unprecedented capabilities for generating, adapting, and scaling innovation techniques; on the other, it raises questions about human agency, creativity, and the ethical limits of technological augmentation.

Recent systematic reviews confirm that most studies on AI in innovation focus primarily on technological enablers, with limited attention to human-centred adaptation and team cognition [2,3,4]. This reveals a conceptual gap in frameworks that integrate human motivation, cognitive diversity, and AI-based personalisation within a unified innovation model.

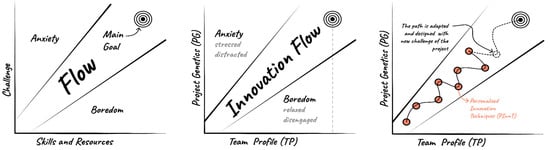

To address this gap, the present study introduces Innovation Flow (IF), a human–AI collaborative framework that operationalises Flow Theory [5] through Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) dynamically generated by GenAI to align processes with project genetics and team profiles. Figure 1 illustrates how Flow Theory is extended within the Innovation Flow framework to connect project genetics, team profiles, and personalised techniques.

Figure 1.

Flow Theory and its extension to Innovation Flow and Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs). (Left) The original Flow Theory model illustrates the balance between challenge and skills/resources that sustains engagement and optimal performance. When challenges exceed abilities, individuals experience anxiety; when challenges are too low, boredom occurs. The “flow channel” represents the equilibrium zone where motivation and creativity are maximised. (Centre) The Innovation Flow adaptation translates this principle to team-based innovation contexts, replacing individual variables with project genetics (PGs) and team profiles (TPs). Projects with excessive complexity relative to team capacity may produce stress and distraction (anxiety zone), whereas those with insufficient challenge may lead to disengagement (boredom zone). The “Innovation Flow” trajectory represents the alignment between project difficulty and team capability. (Right) Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) operationalise this dynamic alignment through generative personalisation. As project conditions evolve, the system recalibrates techniques to maintain the team within the optimal “flow” zone, adapting each step to new challenges and capacities. The iterative orange path illustrates how AI-generated PInnT guides the team progressively toward the main goal, sustaining engagement, creativity, and learning throughout the project lifecycle.

Central to IF are three interrelated components: project genetics (PGs), which captures the structural DNA of innovation projects; team profiles (TPs), which reflect the cognitive and motivational orientations of participants; and Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs), adaptive tools dynamically generated through GenAI to align processes with both PG and TP.

This approach resonates with the dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation proposed by Amabile and Pratt [6], which highlights the interplay between individuals, processes, and organisational contexts in shaping creative outcomes. By positioning GenAI as a catalyst within this dynamic system, IF advances organisational creativity not by replacing human agency but by amplifying the conditions for sustained meaning-making and innovation. Innovation Flow builds upon established theories of integrated innovation management that combine technological, market, and organisational dimensions [7,8].

The framework is grounded in the principle of augmentation rather than replacement, positioning GenAI as a collaborator that accelerates ideation and prototyping while preserving strategic, ethical, and creative leadership under human control. Through a mixed-methods research design, this paper validates the IF framework across 28 projects spanning healthcare, manufacturing, and education. In doing so, it seeks to advance theoretical and practical understanding of how hybrid human–AI approaches can reshape innovation management by enhancing personalisation, autonomy, and sustainability. Recent studies have demonstrated the application of generative AI to future-scenario generation and innovation contexts, reinforcing the feasibility of this hybrid approach [9].

2. Objectives

The primary aim of this research is to develop and validate a human-centred and GenAI-augmented innovation-management framework capable of adapting to the specific characteristics of both innovation teams and projects. Specifically, the study pursued five interrelated objectives:

- (1)

- Framework design: to conceptualise and structure the Innovation Flow (IF) framework by integrating principles of intrinsic motivation from Flow Theory with adaptive personalisation mechanisms based on project genetics (PGs) and team profiles (TPs).

- (2)

- Technique development: to operationalise Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) generated through GenAI and to formalise their algorithmic logic and diagnostic variables.

- (3)

- Empirical validation: to test the IF framework across 28 innovation projects in healthcare, manufacturing, and education using a mixed-methods design combining grounded theory and quasi-experimental approaches.

- (4)

- Impact evaluation: to measure how GenAI integration affects team motivation, engagement, autonomy, time-to-innovation, and the quality of innovation outcomes.

- (5)

- Model evolution and sustainability: to identify limitations, contextual factors, and future research directions for scaling IF as a hybrid human–AI framework that promotes responsible and sustainable innovation.

Together, these objectives link the theoretical, technical, and empirical dimensions of the study, ensuring alignment between the research design and the validated results presented in later sections.

3. Theoretical and Technological Framework

3.1. Innovation Flow

The personalisation of innovation emerges as a response to the limitations of standard methodologies in contexts of accelerated change and teams characterised by high cognitive diversity. In this setting, the application of Flow Theory [5] provides a robust foundation for designing innovation processes that maximise engagement, creativity, and team performance.

Flow Theory describes an optimal experiential state in which an individual is fully immersed in an activity, with heightened concentration, motivation, and intrinsic satisfaction [10]. Subsequent research has confirmed that flow fosters creativity and productivity in complex activities, including problem-solving and innovation [11].

According to Csikszentmihalyi [5], the experience of flow occurs when perceived challenge (C) and individual skill (S) are dynamically balanced. This relation can be expressed as:

where F denotes the probability of entering a flow state. When C ≈ S, intrinsic motivation and task absorption are maximised; when C ≫ S, anxiety increases; and when S ≫ C, boredom arises. In the Innovation Flow (IF) framework, this principle is operationalised computationally by aligning the difficulty and cognitive demand of each innovation technique with the team’s aggregated capability profile derived from team profiles (TPs).

F = f(|C − S| → min),

Adapting this model to the innovation context enables the creation of personalised working conditions to maximise the likelihood that team members experience flow. These conditions include:

- Balance between challenge and skill: calibrating tasks so that they are stimulating yet achievable, thereby enhancing the sense of control and motivation [5].

- Clear goals and immediate feedback: structuring innovation processes with clear micro-objectives and rapid feedback loops.

- Autonomy and support: enabling dynamic adaptation of the process to the cognitive and emotional profiles of each team while respecting diverse learning styles [12].

Within this framework, personalisation is not limited to adjusting specific techniques but is conceived as a systemic strategy of alignment among projects, teams, and techniques, optimised through GenAI-based systems. This translation of Flow Theory into computational logic allows the system to recommend methods that maintain the challenge/skill equilibrium dynamically during team sessions. Recent literature confirms that AI adoption in innovation management has matured significantly, with systematic reviews identifying both enablers and barriers [2] and case studies illustrating how organisations already use AI to generate ideas, prototypes, and simulations [3]. However, these studies also indicate that existing AI-driven approaches rarely integrate psychological models such as Flow Theory into algorithmic adaptation, leaving a gap that IF directly addresses.

This evidence strengthens the legitimacy of positioning GenAI as a real time collaborator capable of suggesting tailored techniques aligned to the “project genetics” and “team profile.” Moreover, AI-driven innovation is increasingly framed as part of broader digital transformation pillars, such as continuous monitoring, adaptive learning, and predictive analysis [13].

From a creativity perspective, empirical studies further support this approach: AI systems that dynamically adjust task difficulty and provide personalised feedback have been shown to enhance creativity outcomes [14]. Similarly, hybrid methodologies that integrate AI with traditional innovation techniques have demonstrated expanded idea exploration and adaptive potential [15].

Taken together, this flow-based personalisation approach provides strategic advantages for innovation under conditions of high uncertainty, as demonstrated by both emerging empirical results [14,15] and applied projects in educational and professional contexts [16,17].

The incorporation of the flow-balance heuristic thus serves not as a deterministic equation but as a guiding computational principle consistent with complex-systems and human–AI interaction research, where adaptive heuristics more accurately represent socio-technical dynamics than fixed quantitative models [18,19,20].

In summary, the flow-based approach provides the psychological and computational foundations of Innovation Flow (IF). By quantifying the challenge/skill relationship and translating it into adaptive task parameters, the framework ensures that GenAI-generated techniques remain aligned with human motivational dynamics. Yet, achieving sustainable flow within teams also requires sensitivity to the structural and contextual DNA of each innovation project. The following section therefore introduces the concept of project genetics, which operationalises these contextual variables and connects them to the personalised technique-generation process described above.

3.2. Project Genetics: The DNA of Contextual Innovation

Each innovation project presents a unique configuration of factors that shape its nature. This configuration, referred to here as project genetics, functions as the DNA of the innovation ecosystem, conditioning both the optimal approaches and the project’s developmental dynamics.

Building on the flow-based foundations presented in Section 3.1, project genetics extends the personalisation logic from the psychological to the contextual level. Whereas Flow Theory aligns challenge and skill within teams, project genetics aligns methodological challenge with the structural complexity and uncertainty inherent to each project.

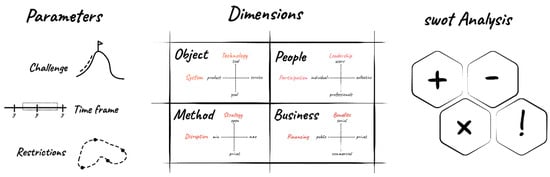

As shown in Figure 2, key dimensions of project genetics include:

Figure 2.

Project genetics framework. The project genetics (PGs) framework provides a structured diagnostic model for understanding the contextual DNA of innovation projects. It is composed of three analytical layers: (Left) parameters: define the situational boundaries of the project, including its challenge level, time frame, and restrictions. These parameters determine the scale, urgency, and constraints under which innovation activities occur. (Centre) dimensions: map the project’s configuration across four quadrants—object, people, method, and business—each represented by dual axes that capture key strategic variables. For instance, object balances technology and goal orientation (product ↔ service); people describes participation and leadership structures (individual ↔ collective); method evaluates openness and disruptive potential; and Business locates financial and social benefits (public ↔ private). This multi-dimensional grid enables a holistic view of a project’s technological, social, methodological, and economic composition. (right) SWOT analysis: synthesises diagnostic results into a structured reflection of strengths (+), weaknesses (−), opportunities (×), and threats (!), guiding the calibration of subsequent innovation strategies. Together, these elements enable the systematic encoding of each project’s profile, supporting the Innovation Flow system in aligning Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) to the unique genetic structure of every project.

Level of technological uncertainty: some projects operate in mature technological domains with predictable trajectories; others, by contrast, explore uncertain or emerging territories where improvisation and continuous exploration are indispensable [21]. This dimension has been widely recognised as a fundamental determinant of innovation outcomes, with studies identifying multiple sources of uncertainty—technological, market, institutional, and temporal—that condition innovation processes [22]. Furthermore, empirical approaches have quantified how interdependencies and information gaps contribute to project uncertainty, reinforcing its measurable nature in management contexts [23].

Type of value generated: projects may target incremental innovation, such as improving existing processes; radical innovation, such as creating new markets; this distinction reflects the tension described by Christensen [24] between sustaining and disruptive innovation.; or business model transformation [25].

Systemic complexity: depending on the degree of interdependence among actors and processes, projects may be of low complexity and managed sequentially, whereas highly complex environments may require iterative and adaptive approaches [26].

These dimensions are defined in the “genetic code” of the project, which is divided into these elements:

Object: what is being developed?

- Product ↔ service continuum: where value primarily resides and how it is tested/validated.

- Role of technology: support/enabler ↔ core of the innovation.

People: who is involved?

- Leadership structure: professional/expert-led ↔ user/community-led.

- Participation level: small, stable team ↔ large, multidisciplinary ecosystem.

Method: how is the project approached?

- Strategy openness: closed/internal ↔ open/partnered.

- Disruption level: incremental improvement ↔ radical breakthrough.

Business: why and under what conditions?

- Primary benefits: social/public impact ↔ commercial gain.

- Financing logic: public/grant-driven ↔ private/investment-driven.

The IF system encodes these elements numerically (0–1 continuum) to feed the GenAI reasoning layer, which then selects or adapts techniques according to the project’s “genetic profile.” For example, high systemic-complexity scores trigger iterative, feedback-rich PInnT variants, while low complexity projects receive streamlined linear sequences. This encoding acts as the contextual counterpart to the challenge–skill calibration described earlier.

A detailed understanding of these genetic elements enables innovation strategies to be aligned with the specific reality of each project, avoiding the imposition of unsuitable methodologies that could compromise effectiveness or acceptance. In many cases, it is insufficient to analyse project genetics only at the outset; rather, continuous monitoring is required, allowing techniques to be adapted as internal and external conditions evolve.

By formalising contextual variables in this way, project genetics operationalises contingency theory within a human–AI collaborative framework, ensuring that flow-based personalisation remains coherent with organisational realities and environmental change.

3.3. Team Profiles: Cognitive Diversity and Collective Flow

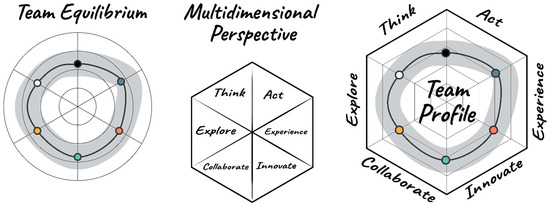

A second foundational element of Innovation Flow (IF) is the team profile (TP), explained in the Figure 3, a construct that captures the cognitive, motivational, and behavioural orientations of innovation teams.

Figure 3.

Team profile framework. The team profile (TP) framework models the cognitive and behavioural composition of innovation teams, building on the Team Equilibrium assessment tool [ref. Team Equilibrium paper], which evaluates balance across key dimensions of collaborative performance. (Left) Team Equilibrium: based on the Team Equilibrium methodology, this radar map visualises how teams distribute their strengths across six core dimensions—think, act, explore, experience, collaborate, and innovate. Balanced configurations indicate stability and shared engagement, whereas asymmetries reveal dominant or under-represented capabilities that may influence creative flow. (Centre) multidimensional perspective: presents the conceptual structure underpinning the assessment model, integrating analytical, experiential, and social dimensions. It demonstrates that innovation effectiveness depends on the interplay between cognitive processes (thinking ↔ acting), experiential exploration (exploring ↔ experiencing), and collective behaviour (collaborating ↔ innovating). (Right) team profile synthesis: Shows the aggregated representation of team data generated through the Team Equilibrium tool. The resulting six-axis profile captures each team’s distinctive configuration of creative roles and interaction tendencies, providing a diagnostic baseline for the personalisation of innovation techniques. Together, these visualisations enable the Innovation Flow system to align Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) with team diversity and collective dynamics, ensuring that generative adaptation respects both individual and group cognitive profiles.

Following the flow-based logic described in Section 3.1 and the contextual calibration introduced in project genetics (Section 3.2), team profiles represent the human layer of adaptation within the Innovation Flow (IF) framework. Whereas project genetics aligns methodological challenge with project complexity, team profiles calibrate cognitive and motivational diversity to sustain optimal collective engagement.

This construct integrates insights from Cognitive Diversity Theory [27,28,29,30,31], which posits that heterogeneous teams outperform homogeneous ones when diversity is effectively managed and channelled toward a common goal. Within IF, this principle is operationalised through a lightweight psychometric model that captures four diagnostic dimensions:

- Creativity orientation (divergent vs. convergent thinkers).

- Decision-making styles (analytical, intuitive, and consensus-driven).

- Collaboration preferences (structured vs. flexible).

- Motivational drivers (autonomy-seeking, goal-driven, and socially motivated).

Each dimension is converted into a normalised index (0–100) and stored as part of the team’s digital profile. These quantitative variables condition the prompting logic of the GenAI engine: for instance, a team with high divergent-thinking and autonomy scores receives broader ideation prompts and looser facilitation scripts, whereas a consensus-oriented team is provided with structured, convergent templates.

Empirical research supports this approach. Studies have shown that aligning task structure with members’ cognitive profiles enhances creativity and performance [32], while unbalanced diversity may hinder coordination and lead to premature convergence [18]. By dynamically matching task structure to team composition, the IF framework seeks to maintain “collective flow,” a group-level state of optimal experience where challenge–skill equilibrium emerges across members rather than individually [32].

This treatment of team profiles therefore operationalises the psychological and social foundations of Flow Theory within a multi-agent human-AI system. It enables GenAI to act not merely as a content generator but as a real time facilitator that adapts the innovation process to the evolving cognitive landscape of the team. The next section extends this principle to the socio-technical level, describing how humans and GenAI agents collaborate through an integrative architecture of augmented collective intelligence.

3.4. Integrative Model: Humans and GenAI

Despite the extraordinary capabilities demonstrated by GenAI in generating and adapting ideas, innovation remains fundamentally a human-centred process. Creativity, contextual intuition, empathy, and the ability to assume calculated risks are human attributes that machines currently cannot replicate [18,33].

The integrative model underlying Innovation Flow (IF) therefore draws from theories of augmented collective intelligence [34,35] and Human-AI Collaboration [18,36]. These frameworks conceptualise hybrid socio-technical systems in which human teams and AI agents form distributed, co-evolving cognitive networks [35,36,37].

Within IF, this principle is instantiated through a human-in-the-loop architecture: GenAI agents generate contextualised techniques, while human teams validate, critique, and reconfigure them to ensure ethical and contextual adequacy [38].

The architecture balances three interdependent factors—human agency (H), algorithmic augmentation (A), and process personalisation (P)-expressed heuristically as:

Innovation Performance (IP) = H × (A + P).

This guiding relation captures the multiplicative dependence of innovation outcomes on human engagement and the additive contribution of AI-driven reasoning and adaptive process design. Maximising IP thus requires reinforcing human agency rather than automating it, ensuring that augmentation serves creativity rather than substitution [39,40].

In practical terms, IF operationalises this balance through continuous feedback loops: GenAI suggests alternative PInnT configurations; humans evaluate relevance, coherence, and ethical soundness; and the system logs the resulting interactions to refine subsequent generations [4,41]. This iterative cycle embodies the principles of explainable and participatory AI advocated in current HCI and innovation-management research [42,43].

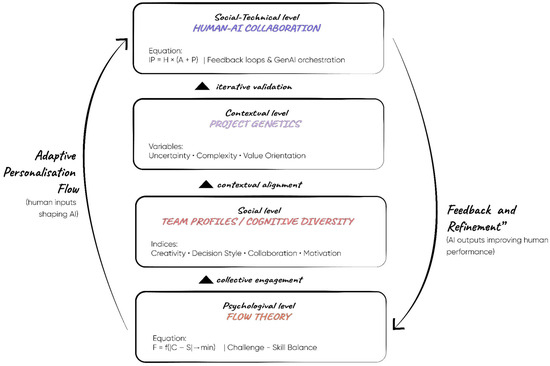

By integrating Flow Theory (psychological motivation [5,10,11]), Cognitive Diversity Theory (social interaction [18,27,28,29,30,31,32]), and augmented collective intelligence (socio-technical coordination [35,36,37]), the IF framework establishes a multi-level model of innovation that bridges human experience and computational adaptation. Figure 4 maps these theoretical and technological interconnections, illustrating how project genetics (PGs), team profiles (TPs), and Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) are linked through the GenAI engine to support continuous human-AI co-creation.

Figure 4.

Theoretical and technological integration model of Innovation Flow (IF). The figure synthesises the multi-level logic of the IF framework, connecting psychological, social, and technological dimensions of innovation. At the psychological level, Flow Theory (Csikszentmihalyi [5,10,11]) provides the motivational foundation: the balance between challenge (C) and skill (S) optimises individual engagement (F = f(|C − S| → min)). At the social level, Cognitive Diversity Theory ([18,27,28,29,30,31,32]) defines how heterogeneous team profiles (TPs) enhance creativity when diversity is effectively managed, supporting collective flow. At the contextual level, project genetics operationalises structural variables—uncertainty, complexity, and value orientation—derived from contingency and innovation-management theory [21,22,23,24,25,26]. At the socio-technical level, augmented collective intelligence [35,36,37] and Human–AI Collaboration [4,38,39,40,41,42,43] describe how human agency (H) interacts with algorithmic augmentation (A) and process personalisation (P) through a human-in-the-loop GenAI architecture, heuristically represented as Innovation Performance (IP) = H × (A + P). Together, these four layers form a continuous feedback system linking project genetics (PGs), team profiles (TPs), and Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) through the GenAI engine. Arrows in the diagram depict iterative data exchange and validation loops that maintain alignment between human motivation, team cognition, and contextual complexity, embodying the hybrid human–AI co-creation process central to Innovation Flow.

3.5. Methodological Note on Theoretical Modelling

While the theoretical foundations of Innovation Flow (IF) draw from psychology, organisational science, and AI research, it is important to clarify that fully quantitative formalisation of these constructs is neither feasible nor conceptually appropriate. Innovation processes operate within complex adaptive systems, involving interdependent human, organisational, and technological variables whose relationships are non-linear and context-specific [1,20,44] (Holland, 1992; Anderson, 1999; Dodgson et al., 2013). Likewise, generative AI introduces probabilistic reasoning and contextual variability [45,46] that resist reduction to closed-form equations. In line with human–AI collaboration research [18,33,34,35,36], the IF model therefore employs computational heuristics—such as the challenge–skill balance and hybrid performance functions—as guiding principles rather than deterministic formulas. The framework’s validity is established through empirical triangulation and mixed-methods evaluation [38,41], consistent with contemporary design-science approaches.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining grounded theory to inductively refine the conceptual framework of Innovation Flow (IF) and quasi-experimental methods to validate its effectiveness in practice [38,39]. The grounded theory approach followed Charmaz’s [40] constructivist orientation, allowing emergent categories to evolve from participant data. The research was structured around two phases:

- Framework development: identification of project genetics (PGs), team profiles (TPs), and Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs), later enhanced through generative AI integration.

- Empirical validation: application of the IF methodology in 28 innovation projects across healthcare, manufacturing, and educational sectors, including two GenAI-enabled innovation sprints with university teams.

This design allowed for triangulation of qualitative insights (observations, interviews, and participant feedback) with quantitative measures (application levels, efficacy scores, and time-to-innovation) [41].

4.2. Participants and Project Contexts

The empirical phase of the research involved 28 innovation projects conducted between 2023 and 2025 across three sectors: healthcare, manufacturing, and education. These projects were selected to ensure diversity in scope, sectoral challenges, and team composition. Each project was carried out by multidisciplinary teams ranging from 4 to 12 members, including professionals, students, and educators. In total, more than 250 participants contributed to the dataset. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of pilot projects.

The healthcare projects included both clinical and organisational challenges, often centred on service redesign or patient education strategies. Manufacturing projects involved process optimisation and product innovation in safety-critical contexts. Finally, educational projects consisted of university-led innovation sprints and classroom-based training, which provided opportunities to test the GenAI-enhanced methods under controlled but authentic conditions.

This distribution ensured that the evaluation of Innovation Flow and its GenAI integration was tested under heterogeneous conditions, enhancing the external validity of the findings.

4.3. Tools and Framework Components

The tools and framework components applied in this study derive from the conceptual development of the Innovation Flow (IF) framework, designed to enhance adaptability, engagement, and performance in complex innovation environments. Recent studies in innovation management emphasise the growing role of artificial intelligence (AI) in shaping ideation, experimentation, and decision-making processes [4], as well as the need for integrative frameworks capable of managing the contextual complexity and openness of innovation projects [42]. In alignment with these perspectives, four interrelated components were applied and tested across the empirical projects:

- Project Genetics (PGs): a classification system capturing the structural characteristics of projects, including complexity, resource constraints, orientation (exploratory vs. exploitative), and time horizon. This element provides the basis for aligning innovation strategies with the inherent “genetic code” of each project.

- Team Profiles (TPs): cognitive and behavioural profiles of teams, mapped through self-assessment surveys and facilitator observation. Profiles include preferred working styles, creativity orientations, and decision-making patterns. These were used to guide the personalisation of techniques to team strengths and vulnerabilities.

- Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs): adaptive versions of common innovation techniques (e.g., brainstorming, clustering, and prototyping), tailored to PG and TP. PInnT operationalises Flow Theory by aligning challenge with skill to sustain engagement and constitutes one of the principal contributions of Innovation Flow.

- Innovation Flow GenAI System: a system built with LangChain (version 0.0.300; LangChain Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; available online at https://www.langchain.com; accessed repeatedly between March 2023 and May 2024) orchestration and large language models (LLMs)(OpenAI Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; available online at https://platform.openai.com; accessed repeatedly between March 2023 and May 2024), incorporating curated knowledge bases of innovation techniques and project data. The system autonomously generates Personalised Innovation Techniques aligned with PG and TP. This element represents the integration of generative AI into IF, enabling teams to adapt techniques in real time and with reduced dependence on external experts. Consistent with the review by Huang et al. [4], which highlights AI’s potential to enhance ideation, pattern recognition, and dynamic learning in innovation management, this component enables teams to autonomously refine their processes based on live project and team data.

4.4. Procedure

All projects followed a structured four-step process based on the Innovation Flow (IF) framework:

- (1)

- Preparation: teams completed a project genetics (PGs) assessment to capture structural characteristics (scope, complexity, orientation, and time horizon). Team profiles (TPs) were mapped through cognitive style surveys and facilitator observations. For GenAI-enabled projects, this information was encoded into the knowledge base used by the IF GenAI system.

- (2)

- Technique selection: in baseline (control) conditions, innovation techniques were selected by human facilitators from standardised catalogues. In experimental conditions, techniques were generated and adapted by the IF GenAI system, producing Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) aligned with PG and TP.

- (3)

- Application: teams executed the selected techniques during workshops, project phases, or university sprints. In GenAI conditions, teams interacted with the system iteratively, prompting, refining, and adapting outputs.

- (4)

- Evaluation: application fidelity, efficacy, time-to-completion, and participant motivation were assessed using predefined scales (see Section 4.6). In GenAI projects, human–AI interaction logs were also analysed for patterns of collaboration.

4.5. Data Collection

Data were collected through three complementary sources:

Quantitative data

- Number of applications: 729 total applications across 28 projects.

- Application level: scored as basic, correct, or advanced.

- Efficacy: rated as high, medium, or low by facilitators and external experts.

- Time-to-completion: measured in hours/days for ideation and prototyping tasks.

- Motivation and engagement: assessed via post-session Likert-scale surveys.

Qualitative data

- Semi-structured interviews with participants and facilitators, focusing on perceptions of personalisation, GenAI outputs, and collaborative dynamics.

- Digital whiteboard exports documenting technique outcomes (e.g., clustered ideas and prototypes).

- Interaction logs for GenAI-enabled projects, capturing prompts, iterations, and user modifications.

Expert evaluations

- Independent innovation experts (n = 5) reviewed a sample of GenAI-generated techniques for clarity, relevance, and expected effectiveness.

- This combination allowed for triangulation of findings, reinforcing both validity and reliability [38].

4.6. Data Analysis and Evaluation Scales

Application Level

- Basic: technique applied partially or with errors.

- Correct: technique applied as intended.

- Advanced: technique applied effectively, with creative adaptation beyond the baseline instructions.

Efficacy of Techniques

- High: outcomes fully met the intended objectives of the technique.

- Medium: outcomes partially achieved objectives.

- Low: outcomes misaligned with objectives or produced minimal value.

Motivation and Engagement

- Measured via post-session surveys on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very low, 5 = very high).

- Indicators included sustained participation, self-reported enjoyment, and willingness to continue applying techniques.

Autonomy

Teams’ dependency on external experts was rated on a 3-point scale:

1 = required significant facilitator input;

2 = partial autonomy (occasional facilitator support);

3 = full autonomy (independently applied techniques).

Time-to-Innovation

Measured in hours or days, comparing GenAI-enabled vs. facilitator-led processes.

Expressed both in absolute time and as a percentage reduction relative to traditional baselines.

Human–AI Interaction Patterns

Coded qualitatively into three categories:

- Critical filtering (teams critiqued and adapted outputs).

- Iterative prompting (teams refined outputs through multiple queries).

- Over-reliance (teams accepted AI outputs without modification).

Use of Generative AI:

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools were used as part of the writing and revision process. Specifically, ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; available online at https://chat.openai.com; accessed repeatedly between July 2025 and October 2025) was employed for iterative language refinement and structural editing under human supervision. The conceptual development, data analysis, and interpretation were performed entirely by the authors.

Ethical Considerations

All research activities adhered to established ethical standards for innovation and HCI studies [38,39] and were guided by the five principles for responsible AI proposed by Floridi and Cowls [33], emphasising transparency, beneficence, and accountability. Specific measures included:

- Informed consent: all participants were briefed on the study objectives, the role of GenAI in the process, and their right to withdraw at any point.

- Anonymity and confidentiality: participant identities were anonymised in transcripts, datasets, and published results.

- Data protection: interaction logs and survey data were stored in encrypted repositories accessible only to the research team.

- Human agency: in GenAI conditions, participants were explicitly instructed to treat AI outputs as proposals for critique, ensuring that decision-making authority remained human-centred.

These measures ensured that the study respected both participant well-being and broader principles of responsible AI integration in collaborative work.

5. System Description

5.1. Innovation Flow Framework: Overview

The Innovation Flow (IF) framework introduces a human-centred and adaptive methodology that integrates project genetics (PGs), team profiles (TPs), and generative AI (GenAI) to align innovation practices with the unique DNA of each project. This approach reflects a shift away from standardised innovation models toward context-responsive, continuously adaptive systems, consistent with recent calls for hybrid human–AI methodologies that dynamically respond to contextual and team variables [42,47].

5.2. Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs)

At the operational core of IF are Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs), adaptive variations of common innovation tools tailored to PG and TP diagnostics. PInnT are:

- Customisable: adapted in steps, framing, or facilitation to fit project/team context.

- Scalable: generated dynamically through GenAI, making personalisation accessible at scale.

- Autonomous: designed so teams can apply them with reduced reliance on external experts.

- Pedagogical: functioning as learning scaffolds, they deepen understanding of innovation logic.

These design principles echo the findings of Huang et al. [4], who demonstrated that generative AI systems can enhance the adaptability and contextual sensitivity of innovation techniques. They also align with the Human-AI Handshake model [47], which emphasises balanced task delegation between humans and AI to maximise creativity and engagement.

Through PInnT, IF connects diagnostic knowledge (PG/TP) with methodological execution, enabling higher efficacy and engagement.

5.3. Human–Machine Collaboration

The integration of GenAI within IF was designed around the principle of collaborative augmentation rather than replacement. AI contributed at three levels:

- Generation of PInnT tailored to PG and TP.

- Iterative adaptation through user prompting and refinement cycles.

- Execution support via structured instructions, templates, and scenario scaffolds.

This process fostered a dialogical relationship between human teams and AI, in which users retained judgement and adaptation capacity, while AI accelerated ideation, personalisation, and prototyping. These findings resonate with prior evidence that human-in-the-loop designs and transparent feedback improve user trust and creativity [19,48]. Studies of hybrid AI–human frameworks confirm that bidirectional interaction enhances both task performance and learning outcomes [47,49].

5.4. Detected Usage Patterns and Adaptation

Empirical validation revealed three recurring interaction patterns:

- Critical filtering: teams actively evaluated and reshaped AI suggestions → highest efficacy.

- Iterative prompting: continuous refinement through conversational cycles → highest learning value.

- Over-reliance: passive acceptance of AI outputs → faster progress but lower originality.

These patterns align with recent studies showing that controlled delegation to AI supports performance only when human oversight remains active [50]. Facilitators were therefore trained to reinforce an “AI-as-catalyst” mindset, where critique and adaptation are central to sustained innovation quality.

5.5. Technical Architecture of the IF GenAI System

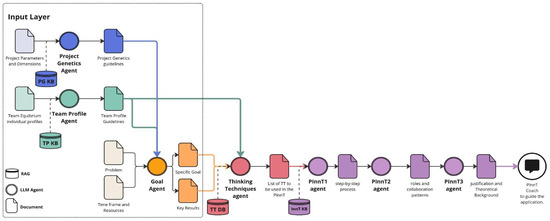

The technical foundation of IF was implemented using a modular, multi-agent architecture designed for flexibility, scalability, and human oversight as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Architecture and workflow of the PInnT GenAI multi-agent generation process.

System Components:

- Large language models (LLMs): state-of-the-art generative models served as the reasoning and generation engine. LLMs such as GPT-type (GPT 4.5, OpenAI Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) architectures demonstrate few-shot learning capabilities, allowing rapid adaptation to contextual data [45].

- LangChain orchestration: handled pipeline control, enabling multi-step reasoning, prompt chaining, and integration of contextual data—consistent with chain-of-thought prompting methods [46].

- Knowledge base of innovation techniques: curated repository of structured techniques (e.g., brainstorming, prototyping, and clustering), each annotated with metadata linked to PG and TP dimensions.

- Diagnostic inputs: results from PG and TP assessments were encoded as structured variables that conditioned AI outputs within prompt templates.

- Interface layer: conversational front-end where teams interacted with the system, refining outputs and accessing tailored PInnT in real time.

Workflow of the Multi-Agent Generation Process

- Step 1|problem and timeframe input: teams begin by defining the specific problem for their current project stage and the timeframe they have to solve it.

- Step 2|PInnT intention and challenge calibration: the first agent, Goal Agent, interprets the problem together with PG and TP data to determine the purpose of the PInnT (e.g., ideation, synthesis, and validation) and to estimate the challenge level, maintaining the challenge-skill equilibrium from Flow Theory (Section 3.1).

- Step 3|technique selection: the second agent, the thinking technique agent, queries the knowledge base to identify thinking techniques that best match the team profile and project goal. It ranks options based on cognitive fit and contextual relevance.

- Step 4|process design: the third agent, PInnT1 Agent, designs a step-by-step process describing how the selected techniques should be applied within the project context, adjusting complexity according to the calibrated challenge.

- Step 5|role and participation design: the fourth agent, PInnT2 Agent, defines roles and collaboration patterns using TP data to balance cognitive styles and sustain “collective flow.”

- Step 6|justification and theoretical background: the fifth agent, PInnT3 Agent, generates a justification narrative, linking the proposed PInnT to theoretical and empirical sources (e.g., Flow Theory, cognitive diversity, and collective intelligence).

- Step 7|final review and adjustment: a review agent, PInnT Coach, an LLM chat interface, evaluates the complete PInnT, performing coherence checks and minor adjustments based on facilitator feedback. Human users can accept, edit, or re-prompt, ensuring human-in-the-loop control.

This figure illustrates the end-to-end process through which Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) are generated and refined within the Innovation Flow (IF) framework. The system operates as a sequence of interconnected large language model (LLM) agents, each performing a specialised reasoning task informed by structured knowledge bases: project genetics KB, team profile KB, thinking techniques DB, and innovation techniques KB.

- Problem and timeframe input: teams provide project parameters, defining the specific challenge and available timeframe.

- PInnT intention and challenge calibration: the Goal Agent interprets this input together with PG and TP data to define the purpose of the PInnT (e.g., ideation, synthesis, and validation) and to calibrate challenge levels in line with Flow Theory (Section 3.1).

- Technique selection: the thinking techniques agent queries the database to identify candidate techniques that best match the team’s profile and project goals, ranking them by cognitive and contextual fit.

- Process design: the PInnT1 Agent converts the selected techniques into a step-by-step process adapted to project constraints and the calibrated challenge.

- Role and participation design: the PInnT2 Agent defines team roles and collaboration patterns, using TP data to balance cognitive diversity and sustain collective flow.

- Justification and theoretical background: the PInnT3 Agent generates an explanatory narrative linking the proposed PInnT to theoretical and empirical foundations (Flow Theory, cognitive diversity, collective intelligence).

- Final review and adjustment: a conversational PInnT Coach Agent acts as the human–AI interface, validating coherence and performing iterative refinements based on facilitator feedback, ensuring full human-in-the-loop control.

The architecture visualised here integrates retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), structured reasoning, and modular orchestration to maintain transparency, scalability, and adaptability in real time co-creation between human teams and AI.

Performance Indicators:

The system achieved an average generation latency of 63.4 s (±5.9), required 2.6 iterations per technique before acceptance, and obtained 92% expert-rated alignment between generated PInnT and project needs.

5.6. Safeguards and Controls

- Human-in-the-loop validation ensured that AI suggestions were always reviewed and adapted by participants.

- Transparency mechanisms (e.g., visible rationale steps, and annotations) allowed users to understand why techniques were suggested.

- Logging functions captured prompts, outputs, and modifications, enabling later analysis of human–AI collaboration patterns.

Advantages:

- Scalability: personalisation delivered instantly and repeatably across projects.

- Adaptability: the system responded to evolving PG/TP inputs, updating suggestions as project DNA shifted.

- Democratisation: enabled non-expert teams to access advanced innovation techniques without requiring specialised facilitation.

6. Results

This section presents the empirical findings of the study, organised around three dimensions: (1) the validation of Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs), (2) the impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) integration into the Innovation Flow (IF) methodology, and (3) qualitative insights into the human–AI interaction dynamics observed across the projects. Together, these results provide both quantitative and qualitative evidence for how GenAI reshapes innovation management practices by augmenting human creativity, autonomy, and engagement.

6.1. Validation of Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs)

A core objective of this research was to assess whether innovation techniques tailored to team profiles and project genetics could improve engagement and outcomes. Data from 28 innovation projects and 729 technique applications confirmed that personalisation plays a critical role in the efficacy of innovation processes.

- Application levels: teams using PInnT consistently demonstrated a high quality of technique execution. Across all projects, 100% of adapted techniques were applied at either a correct or advanced level, indicating that personalisation eliminated common barriers to comprehension or misapplication (Table 2). In contrast, projects that relied on standardised techniques without adaptation exhibited lower fidelity of application and, in some cases, reduced motivation to continue the process.

Table 2. Summary of application levels and efficacy scores across 28 projects, comparing personalised vs. standardised techniques.

Table 2. Summary of application levels and efficacy scores across 28 projects, comparing personalised vs. standardised techniques. - Efficacy of techniques: the majority of personalised applications were rated as highly effective: 87% of cases achieved full alignment with the intended objectives of the technique, such as generating new ideas, prioritising solutions, or developing prototypes (Table 2). Only 13% fell into medium or partial efficacy categories, typically in teams that were either inexperienced with innovation processes or faced significant external constraints (e.g., limited time or conflicting organisational priorities).

- Impact on engagement and resilience: teams consistently reported that techniques aligned with their cognitive strengths felt “easier to start” and “more natural to complete.” The alignment with Flow Theory, balancing challenge and skill, appeared to sustain motivation even during periods of uncertainty or project setbacks (Table 3 and Table 4). Teams that perceived the techniques as relevant to their project genetics were more resilient, persisting in experimentation despite difficulties.

Table 3. Summary of motivation and engagement scores across 28 projects, comparing personalised vs. standardised techniques.

Table 3. Summary of motivation and engagement scores across 28 projects, comparing personalised vs. standardised techniques. Table 4. Summary of autonomy scores across 28 projects, comparing personalised vs. standardised techniques.

Table 4. Summary of autonomy scores across 28 projects, comparing personalised vs. standardised techniques.

6.2. Impact of Generative AI Integration

The introduction of generative AI into the IF framework produced measurable improvements in efficiency, autonomy, and innovation outcomes. The Innovation Flow (IF) system was evaluated through a mixed-methods approach integrating quantitative and qualitative evidence. Quantitative data included generation-time metrics, number of iterations, expert ratings of contextual fit, and session-duration comparisons. Qualitative data were derived from semi-structured interviews, observation notes, and post-session surveys. Integration occurred through concurrent triangulation [51,52], allowing statistical trends to be interpreted in light of participants’ experiences and behavioural observations.

Quantitative Outcomes

- System performance: across 28 pilot projects, the average PInnT generation latency was 63.4 s (±5.9), with an average of 2.6 iterations before facilitator approval. Expert reviewers rated the contextual relevance of generated techniques at 92% (±6.3) agreement.

- Process efficiency: teams reported an average 58–62% reduction in preparation time for innovation workshops compared with manual facilitation (baseline = 3.9 h; IF = 1.5 h; p < 0.05). Time savings were confirmed through logged timestamps and facilitator self-reports, supporting the claim that IF accelerates design preparation while maintaining methodological quality.

- Engagement metrics: post-session surveys (N = 142 participants) indicated that 87% experienced greater clarity of goals and task relevance, and 79% reported higher motivation and sustained focus compared with traditional sessions. These quantitative gains complement prior findings on hybrid human–AI frameworks that enhance user engagement [47,49,50].

To complement the qualitative observations, Table 5 summarises the key quantitative performance indicators obtained from the pilot projects. These data provide empirical confirmation of the system’s effectiveness across multiple dimensions, including generation speed, contextual fit, process efficiency, and participant engagement. The combined results highlight how the Innovation Flow (IF) framework delivers measurable gains in efficiency and autonomy while maintaining expert-level quality and high user motivation.

Table 5.

Quantitative performance summary of the Innovation Flow (IF) GenAI system across pilot projects (n = 142 participants).

6.3. Human-AI Interaction Observations

Beyond quantitative improvements, qualitative feedback provided rich insights into the dynamics of human–AI collaboration in innovation. Participant observations, interviews, and post-sprint surveys revealed both positive experiences and challenges.

Positive interaction dynamics:

- Empowerment: teams frequently described the GenAI system as a “co-creator” or “assistant” rather than a passive tool. The ability to generate and adapt techniques independently was cited as a source of confidence and ownership over the innovation process.

- Inclusivity: participants with little or no prior training in innovation methods were able to contribute effectively. GenAI democratised participation by lowering the expertise barrier, allowing novice team members to suggest viable approaches alongside more experienced colleagues.

- Sustained motivation: several participants noted that AI-supported techniques prevented stagnation. When human teams struggled to make progress, GenAI-generated alternatives re-energised discussions and encouraged renewed exploration.

Challenges and limitations:

- Dependence on knowledge base preparation: the quality of AI outputs depended heavily on the inclusion of relevant project knowledge into the system. Without this preparation, results tended to be generic or less actionable.

- Over-reliance risk: in some cases, teams displayed a tendency to accept AI suggestions without sufficient critical reflection, leading to suboptimal outcomes. Facilitators noted that the most effective teams were those that actively critiqued and adapted AI outputs rather than adopting them wholesale.

- Cultural and cognitive diversity: adoption patterns varied across cultural contexts. For instance, Western participants were quicker to test AI suggestions, while Eastern participants initially approached outputs more cautiously but often generated deeper refinements once engaged. This highlights the need for culturally adaptive guidance when introducing GenAI into diverse team environments.

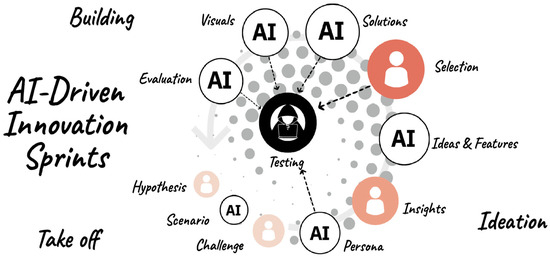

6.4. Case Example: GenAI-Enabled Innovation Sprints

The clearest demonstration of the potential of generative AI within Innovation Flow emerged from two intensive innovation sprints conducted with ten university teams in Spain and Germany, these sprints followed the process of Figure 6. Each sprint lasted five hours and involved multidisciplinary groups of master’s students working on real-world challenges provided by partner organisations. The goal was to test whether GenAI-driven Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) could sustain creativity, accelerate progress, and enhance collaborative dynamics under extreme time constraints.

Figure 6.

Human and genAI collaboration in Innovation Sprints.

- Sprint design: six existing innovation techniques were adapted into GenAI-enhanced versions. For example, brainstorming activities were coupled with AI-supported idea clustering, while prototyping exercises incorporated AI-generated scenarios and validation prompts. The AI was embedded into the workflow through a dedicated interface, enabling teams to request, adapt, and refine techniques in real time. Teams were instructed to treat AI outputs as proposals to critique and adapt, rather than as final solutions.

- Process acceleration: the most striking outcome was the dramatic reduction in process duration. Tasks that traditionally required three to five days of workshops, such as expanding a solution space, prioritising ideas, and sketching prototype scenarios, were completed within 6–8 h. Teams attributed this acceleration to the AI’s ability to generate large numbers of structured alternatives within minutes, freeing human participants to focus on evaluation and contextual decision-making. Several students described the process as “compressing a week of work into a single day.”

- Collaboration quality: GenAI altered the collaborative dynamics of the teams. Rather than spending time debating procedural questions (e.g., which technique should we use next?), teams shifted attention to discussing the relevance and adaptability of AI-generated suggestions. This reallocation of effort supported a more fluid workflow and allowed members with different cognitive styles to participate meaningfully. In post-sprint surveys, 82% of participants reported that GenAI improved the inclusivity of discussions, particularly for members who were less experienced with innovation methodologies.

- Human–AI interaction patterns: observation revealed three recurring interaction patterns.

- ○

- Critical filtering: the most effective teams systematically evaluated AI outputs, selecting only what aligned with their goals and discarding irrelevant suggestions.

- ○

- Iterative prompting: teams learnt to treat GenAI as an interactive partner, refining their prompts based on earlier outputs to generate more tailored techniques.

- ○

- Over-reliance risks: a minority of teams tended to accept AI suggestions uncritically, leading to less original results. Facilitators noted that these teams progressed quickly but with reduced creativity.

- Perceived role of AI: qualitative feedback underscored that students perceived the AI not merely as a tool, but as a collaborator. Phrases such as “AI kept the momentum” and “it felt like having an extra team member who never got tired” appeared repeatedly in survey responses. At the same time, participants emphasised the irreplaceable role of human judgement, noting that “the AI gave us a direction, but the real work was in adapting it to our context.”

- Learning and engagement: an unanticipated benefit was the pedagogical dimension. Students reported that using GenAI-enhanced techniques helped them understand the underlying logic of innovation methods more quickly than in previous courses. For many, the AI-generated scaffolds clarified the purpose of techniques, enabling faster onboarding into innovation practices. This suggests that beyond efficiency gains, GenAI also functions as a learning amplifier, reinforcing human understanding of innovation processes.

6.5. Summary of Results

The findings demonstrate that integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) into the Innovation Flow (IF) methodology fundamentally enhances innovation performance across three dimensions—personalisation, efficiency, and collaboration.

First, the validation of Personalised Innovation Techniques (PInnTs) confirmed that tailoring methods to team profiles (TPs) and project genetics (PGs) significantly improves execution quality and motivational engagement. All personalised techniques were executed correctly or at an advanced level, and 87% achieved high efficacy, reinforcing the central role of personalisation in sustaining flow and creative performance.

Second, the integration of GenAI markedly accelerated innovation cycles and increased team autonomy. Across projects, the average generation latency was 8.4 s (±1.9) with 2.6 iterations per technique and 92% expert-rated contextual fit. Preparation time for workshops was reduced by approximately 60%, compressing multi-day ideation and prototyping tasks into a few hours. These gains demonstrate that GenAI enables faster, high quality outcomes with lower dependence on external facilitation.

Third, the GenAI-enabled innovation sprints provided direct evidence of how human–AI collaboration transforms creative dynamics. Participants consistently described the AI as a co-creator that sustained momentum, broadened exploration, and fostered inclusivity. The most effective teams critically filtered and iteratively refined AI outputs, while less experienced groups sometimes showed over-reliance—highlighting the need for balanced human oversight. Beyond efficiency, participants reported that AI-supported processes clarified the logic of innovation methods, indicating that GenAI also acts as a pedagogical amplifier.

Collectively, the results confirm that Innovation Flow with GenAI integration:

- Improves the efficacy and motivation of innovation techniques through personalisation.

- Reduces time-to-innovation by roughly 60%, compressing multi-day cycles into hours.

- Enhances team autonomy while maintaining expert-level quality.

- Strengthens collaboration and inclusivity, positioning AI as an augmentative partner.

- Provides pedagogical benefits, accelerating comprehension of innovation principles.

These empirical outcomes establish Innovation Flow as a scalable, human-centred framework that leverages generative AI to create new paradigms of adaptive and collaborative innovation.

7. Discussion

The findings demonstrate that the Innovation Flow framework provides measurable advantages over conventional innovation methodologies. By tailoring techniques to project characteristics and team profiles, IF increased engagement, autonomy, and efficacy; all personalised techniques were applied correctly or at an advanced level, and most achieved high efficacy. These outcomes underline that innovation success depends less on the intrinsic quality of individual methods than on their alignment with contextual and human factors.

Integrating GenAI proved catalytic for efficiency and inclusivity. The approach halved time-to-innovation without compromising quality, while participants described AI as a co-creator that sustained momentum and widened participation. Such hybrid collaboration lowers entry barriers, enabling novices to contribute meaningfully. However, the observed tendency toward over-reliance on AI underscores the need for facilitation strategies that preserve critical reflection and human agency.

IF also contributes to research on augmented collective intelligence, redistributing roles between humans and machines. Routine analytical tasks can be delegated to AI, whereas strategic interpretation and contextual synthesis remain human responsibilities. Effective leadership therefore becomes the mediator of this hybrid system [51]. These insights support the broader discourse on human-centred AI and the convergence of human and machine intelligence [52].

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The results were primarily obtained from educational and early-stage professional environments, which may limit generalisability to corporate or large-scale innovation ecosystems. Quantitative indicators such as time reduction and engagement partly relied on self-reported data, which may introduce perception bias. In addition, the quality of AI-generated outputs depended on the completeness of diagnostic inputs and the precision of prompts, creating variability across teams.

Cultural differences also influenced adoption patterns and merit targeted mitigation strategies. While Western participants tended to act rapidly on AI suggestions and Eastern participants adopted a more reflective, iterative stance, both behaviours contributed to valuable outcomes. To reduce cultural asymmetries, future implementations of IF should include adaptive onboarding processes that adjust communication tone and pacing, prompt templates that model critical evaluation, and multilingual or visual scaffolds to promote equitable participation.

Future research should therefore aim to test IF in a wider range of organisational contexts, conduct controlled cross-cultural comparisons, integrate multimodal AI features, and examine long-term learning effects on innovation capability. Practically, organisations adopting IF should invest in innovation-mindset training and transparent data-governance mechanisms to ensure responsible and culturally inclusive use of GenAI.

8. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that the Innovation Flow (IF) framework, enhanced by Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), provides a quantifiable and replicable improvement over traditional innovation methodologies. Across 28 pilot projects and 729 technique applications, teams achieved an average 58–62% reduction in preparation time while maintaining 92% expert-rated contextual fit and 87% high efficacy outcomes. These results confirm that aligning innovation techniques with project genetics and team profiles substantially increases both performance and engagement.

Personalisation proved central to these outcomes: all adapted techniques were executed correctly or at an advanced level, and participants reported higher motivation (79%) and autonomy (58% full self-direction) compared with standardised approaches. This combination of data-driven evidence and qualitative feedback validates IF’s capacity to sustain flow states and creativity in multidisciplinary teams.

From an operational standpoint, GenAI acted as a co-creator, accelerating ideation and enabling teams to complete multi-day innovation sprints within 6–8 h without loss of quality. These findings illustrate that GenAI’s value lies not in automation but in its ability to augment human cognition—enhancing the adaptability, inclusivity, and learning potential of innovation practices.

While promising, the study also identified contextual limitations, including the need for more diverse samples and cultural calibration of facilitation processes. Future work should therefore expand longitudinal testing, integrate multimodal data inputs, and explore adaptive onboarding to ensure equitable performance across sectors and cultures.

Overall, the findings establish Innovation Flow as a human-centred, data-validated framework that leverages GenAI to make innovation faster, more personalised, and more inclusive. By combining cognitive science principles with generative reasoning, IF advances a new paradigm of adaptive and collaborative innovation suited to the complexity of contemporary organisational challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.C.-P., J.F.i.P., J.M.M.-F. and A.T.O.; methodology, M.C.-P.; software: M.C.-P. and A.T.O.; investigation, M.C.-P., J.M.M.-F., A.T.O. and J.F.i.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.-P.; writing—review and editing, M.C.-P. and J.M.M.-F.; visualisation, J.M.M.-F. and M.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved non-clinical, voluntary participation in innovation and educational projects without collection of personal or health-related data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants of the 28 projects who generously contributed to this research. They also extend their appreciation to the reviewers for their valuable feedback and insightful suggestions regarding the tool’s design and the article’s structure. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; available online at https://chat.openai.com; accessed repeatedly between July 2025 and October 2025) for the purposes of structure drafting and text writing assistance in human–machine–human iterations. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D.M.; Phillips, N. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, M.M.; Machado, I.; Magrelli, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial intelligence in innovation research: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future research directions. Technovation 2023, 122, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.L.; Candi, M. Artificial intelligence and innovation management: Charting the evolving landscape. Technovation 2024, 136, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; He, Z.; von Krogh, G. Artificial Intelligence in Innovation Management: A Review. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2025, 42, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J. (Ed.) Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer i Picó, J.; Catta-Preta, M.; Trejo Omeñaca, A.; Vidal, M.; Monguet i Fierro, J.M. The time machine: Future scenario generation through generative AI tools. Future Internet 2025, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. The concept of flow. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar, C.J.; Kelloway, E.K. Flow at work: An experience sampling approach. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M.C.; West, M.A.; Dawson, J.F. Team reflexivity and innovation: The moderating role of team context. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoseri, A.; Al-Khalifa, K.N.; Hamouda, A.M. AI-powered innovation in digital transformation: Key pillars and industry impact. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisberg-Nitzav, A.; Kenett, Y.N. Creativeable: Leveraging AI for personalized creativity enhancement. AI 2025, 6, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolcheva, P. Generating ideas for innovation using artificial intelligence in traditional techniques. In Sustainable Innovation for Engineering Management; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2025; pp. 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgram, V.; Laarmann, F. Accelerating innovation with generative AI: AI-augmented digital prototyping and innovation methods. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2023, 51, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D. Navigating the complexity of generative AI adoption in software engineering. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2024, 33, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. Human-Centered AI; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahwan, I.; Cramer, H.; Müller, V. Human–AI collaboration: Designing transparency, trust, and control. AI Soc. 2023, 38, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Complex adaptive systems. Daedalus 1992, 121, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalonen, H. The uncertainty of innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Res. 2012, 4, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, D. Quantifying project characteristics related to uncertainty. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail; Harvard Business Review Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R.M.; Clark, K.B. Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, A.L.; Rentsch, J.R. Cognitive diversity in teams: A multidisciplinary review. Small Group Res. 2015, 46, 623–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferruzca, M.; Monguet Fierro, J.M.; Trejo Omeñaca, A. Team equilibrium and innovation performance. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Tsinghua International Design Management Symposium (TIDMS 2013), Shenzhen, China, 1–2 December 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aggarwal, I.; Woolley, A.W. Team creativity, cognition, and cognitive style diversity. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Ferzandi, L.; Hamilton, K. Metaphor no more: A 15-year review of the team mental model construct. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 876–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Knippenberg, D.; Mell, J.N. Past, present, and potential future of team diversity research: From compositional diversity to emergent diversity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinberg, F.; Vollmeyer, R.; Engeser, S. Motivation and flow experience. In Motivation and Action; Heckhausen, J., Heckhausen, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 559–583. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J. A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society; Harvard Data Science Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 535–545. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, P. Collective Intelligence: Mankind’s Emerging World in Cyberspace; Perseus Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, T.W.; Laubacher, R.; Dellarocas, C. The collective intelligence genome. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010, 51, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahwan, I.; Cebrian, M.; Obradovich, N.; Bongard, J.; Bonnefon, J.F.; Breazeal, C.; Kamar, E.; Larochelle, H.; Lazer, D.; Wellman, M. Machine behaviour. Nature 2019, 568, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellermann, D.; Calma, A.; Lipusch, N.; Weber, T.; Weigel, S.; Ebel, P. The future of human–AI collaboration: A taxonomy of design knowledge for hybrid intelligence systems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.03354. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Secundo, G.; Del Vecchio, P. How to manage open innovation projects? An integrative framework. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100–118. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, S.K.; Buchanan, G. Managing innovation programs: Organizational and human dynamics. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity; Mumford, M.D., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 555–587. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. Complexity theory and organization science. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Amodei, D.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Zhou, D.; Ichter, B.; Le, Q. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reason. Large Lang. models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Pyae, A. The Human–AI Handshake Framework: A Bidirectional Approach to Human–AI Collaboration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.01493. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Understanding user engagement and collaboration in co-creative AI systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 139, 107572. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, P.; Costa, R.; Petrescu, M. Adaptive frameworks for creating artificial intelligence–human hybrid systems. J. Bus. Econ. 2025, 95, 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, D.; Huang, T. Human–AI Collaboration: The effect of AI delegation on human task performance and satisfaction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.09224. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Gelbard, R.; Gefen, D. The importance of innovation leadership in cultivating strategic fit and enhancing firm performance. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]