Featured Application

The results of this study can be applied to improve radiation protection strategies in medical facilities operating cyclotrons. By identifying differences in neutron emission between 18F and 11C production, the findings support the optimization of shielding design and radiation monitoring, enhancing the safety of healthcare workers and the surrounding environment.

Abstract

This study investigates neutron radiation sources in medical cyclotrons used for PET isotope production, focusing on differences between 18F and 11C. Neutron and gamma dose rates were measured in the bunker and operator control room during routine production with an 11 MeV Eclipse cyclotron. 18F production generated approximately 2.5 times higher neutron levels in the bunker than 11C. Shielding performance also varied: the same wall reduced neutron fluxes by factors of kF = 14,000 for 18F and kC = 86,000 for 11C, while gamma shielding was similar for both isotopes (kγ ≈ 28,000). However, the neutron shielding factor calculated from the data for 18F should be taken as kF ≥ 1.4 × 104, because several neutron readings reached the upper limit of the detector range, which indicates a partial underestimation of the dose in the bunker. Consequently, neutron levels in the control room during 18F production were about 15-fold higher than during 11C production. These differences result from distinct neutron generation mechanisms. The 18O(p,n)18F reaction produces primary neutrons with a Maxwellian spectrum (~2.5 MeV), while 11C neutrons arise solely from secondary interactions in structural materials. The findings emphasize the need for composite shielding adapted to isotope-specific spectra. Annual dose estimates (260 18F and 52 11C productions) showed neutron exposure (3.78 mSv/year, 57%) exceeded gamma exposure (2.82 mSv/year, 43%). The total dose of 6.6 mSv/year is ~33% of regulatory limits, supporting compliance but underscoring the need for dedicated neutron dosimetry.

1. Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is one of the most important medical imaging techniques in oncology, cardiology, and neurology. It enables non-invasive visualization of metabolic processes in the human body. A key element of this diagnostic technology is medical cyclotrons, which produce short-lived positron-emitting radioisotopes, essential for the synthesis of radiopharmaceuticals used in PET studies [1].

1.1. Neutron Generation Mechanisms in Medical Cyclotron (p,n) Reactions

The production of radioisotopes in a cyclotron is based on the bombardment of target materials with high-energy protons. This process utilizes nuclear reactions in which protons from a cyclotron-accelerated beam interact with the atomic nuclei of the target material, leading to the formation of the desired radioisotopes. The isotope 18F is produced by the reaction 18O(p,n) 18F, where the target material is water enriched in the isotope 18O of high purity (99.9999%). In the case of the production of the isotope 11C, a mixture of N2 and O2 gases in a ratio of 39:1 is irradiated, and the reaction is 14N(p,α)11C [1,2]. In the former case, neutrons are generated directly in the production reaction, but they can also be produced in side reactions occurring in structural elements of the cyclotron located in the path of the accelerated proton beam [3,4]. The irradiated target material, a liquid or gas, is located in the target working chamber, a hole drilled in a metal cylinder. Target bodies made of silver, tantalum, titanium, and niobium are used. The working chamber is closed at the beam entrance side with a window made of a durable foil; foils made of a Havar alloy with a high cobalt content are most commonly used. Additionally, the target window is supported by a copper or aluminum mesh. Nuclear reactions of the (p,n) type can occur in all of these elements, and generated in these reactions isotopes are often unstable and undergo radioactive decay, producing ionizing radiation around even a deactivated cyclotron. In the analyzed cyclotron, 21 isotopes activated in side reactions were identified: 52,54Mn, 55Fe, 55,56,57,60Co, 95,95m,96Tc, 182,182m,183,184,184m,186Re produced in the target window made of Havar alloy, 65Zn produced in the grid supporting the window, 109,107Cd in the silver target body, and 181W, 182Ta, 181Hf in the tantalum body [5,6].

Analyzing the mixed gamma and neutron radiation during 11C production via the 14N(p,α)11C reaction, a significant contribution of neutron radiation is observed. In addition to side reactions occurring in structural materials, the 14N(p,n)14O reaction is also open at the applied proton energy of 11 MeV. Although the target material is nitrogen, this process can be considered a secondary or side reaction in the context of this study, as it competes with the desired production channel. The 14N(p,n)14O reaction has a threshold energy of about 6.35 MeV and a cross section of approximately 0.08–0.12 b in the 10–15 MeV energy range. Therefore, it may contribute to the neutron field observed during 11C production. The product isotope, 14O, has a short half-life (T1/2 ≈ 70 s) and decays by β+ emission back to stable 14N, making its direct detection by activation or spectrometric methods difficult. For this reason, the contribution of this channel was not quantified in the present study. However, previous gamma-ray spectrometric investigations have confirmed the occurrence of other secondary nuclear reactions in cyclotron components along the proton-beam path, supporting the plausibility of neutron generation both in the target and in structural materials [1,2].

During the production of 18F and 11C, intense γ radiation is emitted from the de-excitation of atomic nuclei formed in the (p,n) and (p,α) reactions. Although the intensity of this γ flux differs between the two processes, these high-energy photons can induce secondary (γ,n) reactions in materials along the beam path and near the target assemblies. In the present system, such photonuclear interactions may occur in oxygen (threshold 16.3 MeV, σₘₐₓ ≈ 100 mb for 16O(γ,n)15O), nitrogen (10.55 MeV, σₘₐₓ ≈ 80 mb for 14N(γ,n)13N), silver (9.2 MeV, σₘₐₓ ≈ 150 mb for 107Ag(γ,n)106Agᵍ,ᵐ), and tantalum (7.6 MeV, σₘₐₓ ≈ 200 mb for 181Ta(γ,n)180Ta).

At the applied proton energy of 11 MeV, the resulting γ-ray energies are close to or slightly below these thresholds; therefore, the overall photoneutron yield is expected to be small but not negligible. This secondary process may locally increase the measured neutron dose near dense metallic components, but it does not alter the general conclusion that neutron emission is dominated by primary charged-particle reactions.

The production of short-lived positron emitters in medical cyclotrons is inherently accompanied by neutron emission, which has a significant impact on radiological protection of personnel. The properties of this neutron radiation are determined by multiple factors, the most evident being that higher beam currents and proton energies increase both the intensity and maximum energy of the emitted neutrons.

The target material itself plays a critical role in shaping neutron characteristics. In many reactions, neutron emission can be approximately described by the statistical evaporation model, which assumes that, following proton absorption by the target nucleus, a compound nucleus is formed in a state of local thermodynamic equilibrium. The excitation energy E* of this compound system is distributed among all nuclear degrees of freedom and can be expressed as:

where Ep is the incident proton energy, Sp the proton separation energy in the target nucleus, and Q the reaction Q-value. Within this framework, neutron emission is analogous to molecular evaporation from a liquid surface, and the excitation energy determines an effective nuclear temperature T via the relation E* = aT2, where a is the level density parameter.

E* = Ep + Sp − Q,

The nuclear reactions leading to the formation of 18F and 11C proceed mainly through (p,n) and (p,α) channels, respectively, and involve different reaction dynamics. At proton energies around 11 MeV, neutron emission results from a combination of direct, pre-equilibrium, and compound-nucleus processes. The description of these reactions in terms of compound-nucleus formation provides a useful approximation for comparing different target materials, even though reactions on light nuclei such as oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon cannot be fully represented by this formalism alone. They involve a complex interplay of direct and statistical components, and the effective level densities and transition probabilities are only approximate.

For the 18O(p,n)18F reaction, the reaction Q-value is Q = −2.63 MeV, the neutron separation energy of the residual nucleus 18F is Sn = 4.14 MeV, and for 11 MeV protons the excitation energy of the compound nucleus 18F* is approximately E* = 17.8 MeV. With a level density parameter a ≈ 2.25 MeV−1, this corresponds to an effective nuclear temperature of T ≈ 2.8 MeV. The resulting neutron spectrum predicted by the evaporation model exhibits a broad distribution with a peak intensity near En~T and significant contributions extending up to 8–10 MeV.

In contrast, reactions occurring in structural materials, such as 107Ag(p,n)107Cd in silver target components, produce spectra with lower characteristic temperatures (peak near ~1.4 MeV), though the broader level density of heavier nuclei allows for substantial intermediate-energy neutron contributions.

The evaporation model, however, provides only a first-order description of the observed spectra. For light nuclei such as 18O, direct reaction mechanisms—where the incident proton interacts with individual nucleons without full thermalization—contribute significantly, generating neutrons with energies exceeding 6–10 MeV. For medium and heavy nuclei, pre-equilibrium processes with timescales intermediate between direct and compound reactions play an important role, enhancing neutron populations at intermediate energies.

Consequently, while the Maxwell-Boltzmann evaporation framework remains valuable for interpreting overall spectral trends in this work, a comprehensive description of neutron emission from medical cyclotron targets must account for the combined contributions of all underlying processes.

1.2. Neutron Spectra in Medical Cyclotrons

In the study by Infantino et al. [7], basic Monte Carlo concepts using FLUKA, standard application programs, as well as comparative studies on different materials and proton energies were presented. In the case of the 16.5 MeV PETtrace cyclotron in Bologna, a detailed model was developed that integrated both the cyclotron components and the bunker elements, including 18O targets, Havar foils, silver bodies, aluminum elements, and concrete shielding walls.

The simulations revealed extended neutron fluence distributions in the bunker air, characterized by a maximum around 1 MeV, a thermalized neutron range (~0.025 eV), and a tail extending into the low-MeV region. The spectrum obtained from the simulations can be interpreted in the framework of the statistical evaporation model for light nuclei, which predicts an emission maximum around 3 MeV. However, this primary spectrum is modified by moderation processes in the cyclotron structures, resulting in a “softened” distribution with an observed peak near 1 MeV.

As part of the comparative analysis, the efficiency of neutron sources as a function of target material was examined. Targets made of graphite, aluminum, copper, and tantalum were considered, and the proton beam energy ranged from 16.5 MeV to 250 MeV. The simulations demonstrated a systematic increase in neutron yield per incident proton with both increasing target atomic number and beam energy [7].

Previous studies, including both experimental measurements and Monte Carlo simulations, have shown that neutron spectra generated in the vicinity of a cyclotron can be described as the sum of three main components:

- evaporation neutrons, dominating in the 0.3–4 MeV range, with a clear maximum around 1 MeV, originating from the de-excitation of the target nuclei as well as structural materials of the cyclotron, in particular the iron-rich magnetic components;

- epithermal and thermal neutrons, produced through the moderation of fast neutrons in concrete, air, and additional shielding materials [5,7,8].

Measurements performed using Bonner sphere spectrometers equipped with thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLD-600/700), as well as activation analysis with indium foils, unequivocally confirmed the presence of all the above-mentioned components. Investigations carried out in clinical cyclotrons with proton energies of 17–20 MeV and deuteron energies of 8–10 MeV indicated reproducible spectral shapes, regardless of the type of primary beam—always showing a maximum around 1 MeV, characteristic of evaporation neutrons [5,8]. At the same time, a high-energy component extending up to the energy of the accelerated particles was recorded, along with a low-energy tail corresponding to neutrons moderated to epithermal and thermal energies.

Computer simulations performed with MCNP4A and MCNPX codes provided additional information on the character and intensity of neutron fields inside the cyclotron vault. The models included nuclear reactions occurring in the target materials (e.g., 18O, 14N, C, Ta) as well as in structural components such as tantalum collimators or havar foils [7,8]. The results of these calculations allowed the determination of the contribution of individual reaction channels and confirmed the significant role of structural materials in shaping the spectra. For example, proton reactions with tantalum or havar generate additional neutrons with average energies of 1–2 MeV, enhancing the evaporation component.

Analyses of the spatial distribution, carried out using indium activation foils placed at different locations inside the cyclotron vault, revealed substantial variations in the intensity of fast neutrons depending on the measurement position. The highest values were recorded near the target and along the proton beam direction, whereas in access mazes a still significant flux of fast neutrons was observed, which poses a considerable challenge for radiation protection [9,10].

Based on the conducted studies, it can be concluded that the shape of neutron spectra around the cyclotron is determined by: the energy and type of accelerated particles (protons, deuterons), the target material and its backing, the presence of additional structural materials (iron, tantalum, nickel, cobalt), the beam current, as well as the geometry and composition of the concrete shielding. Another important factor is the measurement location—close to the target the spectrum is dominated by the fast component, while at a distance of several meters the fraction of moderated neutrons increases [11,12].

The obtained spectra, derived from both experimental measurements and Monte Carlo simulations, provide a consistent picture of the neutron field in the vicinity of medical cyclotrons. It has been clearly demonstrated that the largest contribution to the radiation dose comes from evaporation neutrons with mean energies of approximately 1 MeV, while the presence of both the fast and thermal components must also be taken into account in shielding design and radiological risk assessment [5,8,10].

1.3. Radiobiological Effects of Neutrons: Physical Mechanisms and Biological Effects

The radiobiological effects of neutrons are a complex phenomenon resulting from the interplay of physical processes and biological responses. From a clinical perspective, acute (deterministic) effects are distinguished, characterized by a threshold dose–response relationship and resulting from direct destruction of cells and tissues after a certain dose threshold is exceeded, and late, stochastic effects (such as mutagenesis and carcinogenesis), the probability of which increases linearly with dose without the existence of a threshold dose [12].

The physical mechanisms of neutron interaction stem from the fact that the neutron is an electrically neutral particle. It is characterized by a relatively high ability to penetrate matter and interacts primarily with the nuclei of atoms in the medium through elastic and inelastic collisions [13]. As a result of these interactions, secondary, charged particles with high ionizing capacity are generated: recoil protons, alpha particles, and heavier nuclear fragments [14,15]. These secondary interaction products are responsible for leaving dense ionization traces in the tissue, characterized by high linear energy transfer (LET). Consequently, they lead to the formation of complex, spatially concentrated DNA damage [14]. Light elements (H, C, N, O) play a key role in the human body. Collisions with hydrogen generate high-energy recoil protons with particularly high biological effectiveness [15]. Reactions with carbon and oxygen nuclei can—in specific reaction channels—lead to the emission of multiple alpha particles (three for 12C and four for 16O, respectively), which further increases the local ionization density and intensifies the biological effects of radiation.

The high LET values characteristic of secondary neutron products result in complex DNA damage, including multiple double-strand breaks in close spatial proximity, base pair damage in clusters, and transverse breaks in protein-nuclear complexes. This type of damage is significantly more difficult for cellular repair systems to repair compared to the diffuse damage typical of low-LET radiation (e.g., photons) [13]. This results in a higher percentage of cells unable to survive repair processes and a higher risk of repair errors, which contribute to the stochastic component of radiation risk. Due to the mechanisms described, neutrons generally exhibit a higher relative biological effectiveness (RBE) than photons at a comparable absorbed dose. However, the RBE of neutrons is a variable quantity, dependent on [16,17]: neutron energy, radiation dose, tissue type, biological endpoint (e.g., cell survival, chromosomal aberrations, cancer induction). Microdosimetric studies and epidemiological analyses, including fundamental studies of survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, indicate a clear dependence of the RBE on neutron energy [16,18,19]. Contemporary radiobiological research is paying increasing attention to biological effects in mixed radiation fields, e.g., neutrons + photons, where the biological effect is additionally influenced by the irradiation sequence [14].

In radiological protection, the weighting factor wR, derived directly from the RBE, is used to calculate radiation doses. This factor has evolved as increasingly precise experimental and epidemiological data have been collected. The initial approach based on a constant value has been replaced by a complex function dependent on neutron energy, which better reflects the actual variability of biological effectiveness [20,21,22,23].

The complexity of neutron mechanisms is currently being analyzed in medicine (neutron radiotherapy, boron neutron capture therapy—BNCT) as well as in the context of environmental and space exposures [24]. Neutron dosimetry studies around medical cyclotrons focus on the nuclear reactions of the produced isotopes (e.g., 18F in the 18O(p,n)18F reaction), which generate fields with a broad energy spectrum [25,26,27]. The nature of the secondary particles and their energy spectrum depend on both the energy of the primary neutrons and the composition of the target material and the environment. These observations are crucial for optimizing radiation shielding and assessing exposure to medical personnel [25]. Previous studies have often overlooked secondary nuclear reactions in shielding and structural materials, although these reactions can noticeably increase the total radiation dose.

The aim of this study is to compare neutron and gamma radiation exposure during the production of 18F and 11C in a medical cyclotron, with particular attention to differences in neutron generation and their impact on radiation protection.

2. Materials and Methods

The studies were conducted using a SIEMENS Eclipse HP cyclotron accelerating protons to 11 MeV. The beam current during isotope production was maintained at 60 μA, with irradiation times of 110 min for 18F production and 60 min for 11C production. The liquid target housing containing oxygen-enriched water (18O-enriched H2O) for 18F production was constructed from tantalum, while the gaseous target housing for 11C production utilized silver construction.

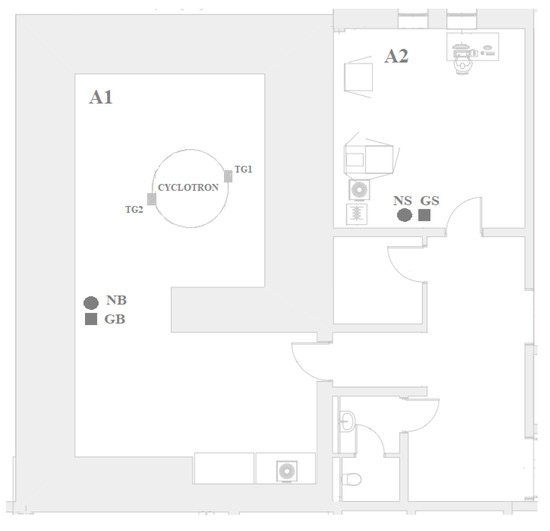

Radiation levels were measured during cyclotron operation using four detection probes that formed part of the cyclotron facility’s environmental monitoring system. These probes were positioned at two distinct locations: within the cyclotron bunker and in the cyclotron control room (Figure 1). Measurements were conducted over 10 production days for each isotope, with 18F measurements followed by 11C measurements, spanning the period from January to August 2025. For each production cycle, real-time neutron and gamma radiation levels were recorded throughout active production periods. Average neutron and gamma dose rates for each probe were subsequently determined over the entire production duration for each isotope.

Figure 1.

Cyclotron zone A1—cyclotron bunker room, A2—cyclotron control room, NB and GB—neutron and gamma probe location points in the bunker, NS and GS—neutron and gamma probe location in the cyclotron control room.

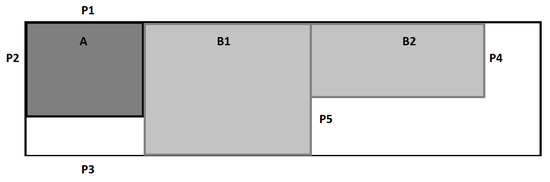

Additionally, measurements were taken in the vicinity of the bunker (P1–P3) and within the boundaries of the supervised area: the corridor of the P4 radiopharmaceutical production zone, as well as at the entrance to the supervised area, which includes the PET scanner room, the administration room, and the rooms where patients stay after radiopharmaceutical administration (P5), using an FH 40 G-10 m with a neutron probe. As shown in Table 1, the FH 40 G-10 m consists of two types of detectors: a gamma radiation detector with a built-in proportional counter, which measures the spatial dose rate of gamma radiation, and a neutron radiation detector with a BF3 moderator, which measures the spatial dose rate of neutron radiation. Measurements were taken during 10 production runs: five 18F runs at target locations TG2 and five 11C runs at locations TG1, from January to August 2025. For each production cycle, a series of single measurements of neutron and gamma radiation dose rates were recorded at 5 different points (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Technical parameters of measuring devices.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the PET-CT Laboratory. A—cyclotron zone, B1—radiopharmaceutical production and quality control zone, B2—PET-CT scanner zone with rooms where patients stay after radiopharmaceutical administration. Points P1–P3 are measurement points located outside the building around the cyclotron zone, points P4 and P5 are measurement points at the entrance to the zones. Areas A and B are controlled-access areas.

3. Results

Table 2 presents the average gamma and neutron radiation dose rates measured in the cyclotron bunker and control room during 18F and 11C production. In the bunker, the average gamma radiation dose rate during 18F production was 166,897 μSv/h, while for 11C it reached 20,552 μSv/h, corresponding to an eight-fold difference. The average neutron radiation dose rate in the bunker was 111,340 μSv/h for 18F and 44,990 μSv/h for 11C, about 2.5 times higher. In the control room, the average gamma dose rate during 18F production was 5.83 μSv/h compared to 0.73 μSv/h for 11C, while neutron dose rates were 7.88 μSv/h and 0.52 μSv/h, respectively.

Table 2.

Average gamma and neutron radiation dose rates measured by environmental monitoring system probes in the bunker and cyclotron control room during 18F and 11C production on the same day. During isotope production, the control system automatically maintains a stable beam current value of 60 μA. In the calculation of averages, values during beam ramp-up and stabilization were excluded.

Analysis of the relationship between gamma and neutron dose rates in the bunker revealed distinct differences between production cycles. For 18F, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was r ≈ 0.01 and Spearman’s ρ ≈ 0.007, indicating negligible correlations. In contrast, 11C production showed r ≈ 0.42 and ρ ≈ 0.84, corresponding to moderate linear and strong monotonic correlations.

The neutron and gamma shielding factors (kₙ, kγ) were calculated for each production day as the ratio of the mean dose rates recorded simultaneously in the bunker and the control room:

Because the beam current was constant (60 μA) for all measurements and the geometry of the measurement setup remained fixed during each isotope production run, this simplified ratio reliably reflects the relative attenuation through the same shielding wall. To account for the slightly different source–detector distances between TG1 (11C) and TG2 (18F), a geometric correction based on the inverse-square law was applied:

where dbunker, dcontrol room are the target-detector distances for each isotopes.

For the distances between the targets and the neutron probes were as follows: for 11C (target TG1), 7.5 ± 0.25 m in the bunker and 8.0 ± 0.25 m in the control room; for 18F (target TG2), 6.0 ± 0.25 m in the bunker and 9.0 ± 0.25 m in the control room, the shielding factors become k′₍11C₎ = (9.8 ± 0.9) × 104 and k′₍18F₎ = (3.15 ± 0.32) × 104. The uncertainties were propagated from the ±0.25 m positional uncertainty of the probes, corresponding to a relative error of approximately 9–10%. After distance normalization, the trend remains the same.

Shielding factors were also evaluated. For gamma radiation, attenuation was similar between isotopes (kγ ≈ 28,000). For neutrons, shielding was more effective during 11C production (kC ≈ 86,000) compared with 18F (kF ≈ 14,000), reflecting substantial differences in energy spectra. For 18F, several NB readings reached the upper range of the neutron probe (0.1 Sv h−1), meaning that the real bunker neutron dose rates were higher than indicated. Using only non-saturated days gives a mean neutron shielding factor of kF(nonsat) ≈ 9900, while considering all data yields kF ≥ 1.4 × 104 as a conservative lower bound. For 11C, neutron shielding was unaffected by saturation

The coefficients of variation (CV) further illustrated differences in measurement repeatability. For 18F, higher variability was observed in the bunker, particularly for gamma radiation, whereas control room values for both gamma and neutron radiation were stable. For 11C production, bunker measurements showed lower variability, especially for neutrons, and external measurements were also consistent.

Table 3 extends these observations by presenting gamma and neutron dose rates measured at external monitoring points. During 18F production, elevated neutron radiation was recorded outside the bunker, while 11C production resulted in significantly lower values.

Table 3.

Gamma and neutron radiation power values measured with the FH40G-10 radiometer around the cyclotron zone and at the entrance to the radiopharmaceutical production zone and the PET-CT scanner for 10 different productions.

Annual dose estimates based on a typical operating schedule (260 productions of 18F and 52 of 11C) indicated that the effective dose in the control room is about 6.6 mSv/year, with neutron radiation as the dominant component (57.3%). In surrounding areas, the annual doses were 0.22 mSv/year in the production corridor, 0.07 mSv/year at the PET facility entrance, and ~0.16 mSv/year at public access points (P1–P3). All values outside the control room were below the 1 mSv/year public limit.

4. Discussion

The results presented in Table 2 and Table 3 clearly demonstrate that 18F production generates significantly higher levels of both gamma and neutron radiation compared with 11C production, with neutron levels being particularly critical in the control room. In the bunker, the absence of correlation between neutron and gamma dose rates shown in Table 2 for 18F suggests independent generation mechanisms: neutrons are mainly produced directly in the 18O(p,n)18F reaction, while gamma radiation originates mainly from nuclear de-excitation. In contrast, the moderate-to-strong correlation observed for 11C production in Table 2 indicates that both neutron and gamma components share a common origin in various secondary interactions of protons and charged particles with structural materials. Although the (p,n) yield from silver is lower than that of the primary 18O(p,n)18F channel, our gamma-ray spectrometric analysis of irradiated targets revealed a dominant formation of cadmium isotopes (107,109Cd), confirming that the 107,109Ag(p,n) reactions occur efficiently at 11 MeV [5]. Therefore, the silver body of the 11C gas target should be regarded as a non-negligible secondary neutron source, as part of the proton beam can interact with its walls when the target operates near the gas-penetration limit. This mechanism likely contributes to the neutron dose observed during 11C production and should be considered in the overall neutron balance of the system.

The shielding analysis based on Table 2 highlights important differences. Gamma attenuation was similar for both isotopes (kγ ≈ 28,000), but neutron shielding was much more effective for 11C production (kC ≈ 86,000) compared with 18F (kF ≈ 14,000, which represents a minimum value). This reflects a lower energy range neutron spectrum generated through secondary processes, which is more easily moderated and absorbed. In contrast, the direct (p,n) channel in 18F production generates fast neutrons up to several MeV, which are more penetrating and thus less effectively attenuated by standard shielding. This inversion of dominance—gamma radiation prevailing in the bunker but neutron radiation dominating in the control room—has direct consequences for radiation protection strategies.

The coefficients of variation (CV) presented in Table 2 for the main (p,n) reaction producing 18F exhibit larger fluctuations. This reaction channel constitutes the dominant process, which strongly depends on the beam parameters and is highly sensitive to their deviations. In contrast, side reactions in other target elements, representing the main source of neutrons during 11C production, contribute to generate a more stable and reproducible radiation field.

The external measurements summarized in Table 3 extend these findings by showing that, during 18F production, elevated neutron radiation was still detectable outside the bunker, whereas 11C production resulted in significantly lower values. These observations confirm that the harder neutron spectrum from 18F is transmitted more effectively through shielding, while the softer spectrum from 11C is more readily absorbed within the shielding configuration.

These findings are consistent with previous reports. Ref. [3] showed that cyclotron neutron spectra exhibit evaporation peaks strongly influenced by structural scattering and moderation. Ref. [10] observed ~3 MeV evaporation neutrons from copper targets, with shielding introducing significant thermal components. Ref. [11] demonstrated sequential (p,n) and (p,2n) channels in heavy materials, broadening spectra with rising proton energy. Ref. [3] confirmed that different structural alloys generate characteristic neutron spectra but always with mixed fast, epithermal, and thermal components. Ref. [8] reported that 18F neutrons are harder to shield compared with those from other production routes. Our data, particularly the shielding factors reported in Table 2 and the external dose rates in Table 3, reinforce these conclusions, showing that 18F neutrons penetrate more effectively, while 11C neutrons are more readily attenuated.

The estimated effective dose of 6.6 mSv/year in the control room, calculated from Table 2 data, corresponds to ~33% of the occupational limit of 20 mSv/year, confirming compliance with safety standards. Doses in publicly accessible areas, derived from Table 3, remain well below the 1 mSv/year limit. In our earlier study on the same cyclotron facility [28], direct dosimetric measurements performed at the actual operator’s location indicated lower exposure levels than those obtained in the present analysis, suggesting that the current estimates may slightly overstate the effective dose. Nevertheless, both studies consistently demonstrate that neutrons constitute the dominant component of the radiation field, underlining the need for dedicated neutron dosimetry and optimized shielding solutions in medical cyclotron installations.

5. Conclusions

The medical cyclotron generates a neutron field with a complex energy spectrum, encompassing both fast and thermal neutrons. This spectrum is defined by neutrons produced directly in the shield’s nuclear reactions, as well as by numerous side processes occurring in the device’s structural components and its surroundings. The diverse energy structure of neutrons is crucial in the design and evaluation of radiological shielding effectiveness. The dose from neutrons is strongly dependent on their energy and therefore the mechanism of their generation. Under operating conditions, the contribution of neutron radiation to the operator’s total effective dose is comparable to the gamma component. The results indicate the need to consider the full neutron spectrum in radiological protection analyses and to maintain individual neutron dosimetry in the cyclotron’s operating environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—T.J.; methodology—T.J. and M.B.; validation—T.J. and M.B.; formal analysis—T.J.; investigation—T.J.; resources—M.B.; data curation—T.J.; writing—original draft preparation—T.J.; writing—review and editing—M.B.; visualization—T.J.; supervision—M.B.; project administration—T.J.; funding acquisition—M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data from these measurements are archived in the internal IT systems of the nuclear medicine department where the measurements were performed.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5 model, OpenAI) to proofread the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PET-CT | Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography |

| IAEA | International Atomic Energy Agency |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

References

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Cyclotron Produced Radionuclides: Principles and Practice; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Cyclotron Produced Radionuclides: Operation and Maintenance of Gas and Liquid Targets; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vega Carrillo, H.R. Neutron energy spectra inside a PET cyclotron vault room. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2001, 463, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloni, D.; Prata, M. Characterisation of the secondary neutron field generated by a compact PET cyclotron with MCNP6 and experimental measurements. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2017, 128, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowska, T.; Długosz-Lisiecka, M.; Biegała, M. Comparison of radionuclide impurities activated during irradiation of 18O enriched water in tantalum and silver targets during the production of 18F in a cyclotron. Molecules 2023, 28, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambali, I.; Suryanto, H.; Parwanto. Radioactive by-products of a self-shielded cyclotron and the liquid target system for F-18 routine production. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2016, 39, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, A.; Cicoria, G.; Lucconi, G.; Pancaldi, D.; Vichi, S.; Zagni, F.; Mostacci, D.; Marengo, M. Radiation Protection Studies for Medical Particle Accelerators using Fluka Monte Carlo Code. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 2017, 173, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.B.; Lee, J.P.; Lin, D.B.; Chen, W.K.; Liu, W.S.; Chen, C.Y. Evaluation of stray neutron distribution in medical cyclotron vault room by neutron activation analysis approach. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2009, 280, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, B.; Singlachar, R. Development of a radiation hardness testing facility for semiconductor devices at a medical cyclotron. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1996, 383, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Sahoo, G.S.; Tripathy, S.P.; Sharma, S.C.; Joshi, D.S.; Bandyopadhyay, T. Measurement of thick target neutron yield from the reaction (p + 181Ta) with projectiles in the range of 6–20 MeV. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2018, 880, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, M.A.S.; Campolina, D.A.M.; Guimarães, A.M.; Benavente, J.A.; da Silva, T.A. Use of the MCNPX to calculate the neutron spectra around the GE-PETtrace 8 cyclotron of the CDTN/CNEN, Brazil. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2014, 83, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, G.M.; Feuerstake, T.; McDonald, C.; Waker, A.J. Investigation of the stray neutron fields produced from proton irradiated Ta, Co-59, Ni, Fe, Inconel X750 and stainless steel 310 targets in a materials testing laboratory environment. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2021, 178, 109961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, S.; Endo, S.; Tanaka, K. Microdosimetric understanding of neutron RBE using a tissue-equivalent proportional counter. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 2010, 143, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stricklin, D.L.; VanHorne-Sealy, J.; Rios, C.I.; Scott Carnell, L.A.; Taliaferro, L.P. Neutron radiobiology and dosimetry. Radiat. Res. 2021, 195, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.M.; Famulari, G.; Montgomery, L.; Kildea, J. A microdosimetric analysis of the interactions of mono-energetic neutrons with human tissue. Phys. Med. 2020, 73, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICRU. Stopping Powers and Ranges for Protons and Alpha Particles; ICRU Report 49; J ICRU: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, M.S.; Endo, S.; Hoshi, M.; Nomura, T. Neutron relative biological effectiveness in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors: A critical review. J. Radiat. Res. 2016, 57, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaeva, E.; Mysara, M.; De Vos, W.H.; Baatout, S.; Quintens, R. Gene expression-based biodosimetry for radiological incidents: assessment of dose and time after radiation exposure. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2018, 94, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D.L.; Ron, E.; Tokuoka, S.; Funamoto, S.; Nishi, N.; Soda, M.; Mabuchi, K.; Kodama, K. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Radiat. Res. 2007, 168, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, G. Predicting neutron RBE: Results from the ANDANTE project. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 2016, 180, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICRP Publication 26. Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann. ICRP 1977, 1. [Google Scholar]

- ICRP Publication 103. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann. ICRP 2007, 37. [Google Scholar]

- ICRP Publication 92. Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE), Quality Factor (Q), and Radiation Weighting Factor (wR). Ann. ICRP 2003, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCRP. Ionizing Radiation Exposure of the Population of the United States; NCRP Report No. 160; National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Infantino, A.; Marengo, M.; Baschetti, S.; Cicoria, G.; Vaschetto, V.L.; Lucconi, G.; Massucci, P.; Vichi, S.; Zagni, F.; Mostacci, D. Accurate Monte Carlo modeling of cyclotrons for optimization of shielding and activation calculations. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2015, 116, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, C.; Silari, M. Neutron spectra around medical cyclotrons. Radiat. Meas. 2012, 47, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utada, M.; Brenner, A.V.; Preston, D.L.; Cologne, J.B.; Sakata, R.; Sugiyama, H.; Kato, N.; Grant, E.J.; Cahoon, E.K.; Mabuchi, K.; et al. Radiation risk of ovarian cancer in atomic bomb survivors: 1958–2009. Radiat. Res. 2021, 195, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegała, M.; Jakubowska, T. Levels of exposure to ionizing radiation among the personnel engaged in cyclotron operation and the personnel engaged in the production of radiopharmaceuticals, based on radiation monitoring system. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2020, 189, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).