1. Introduction

China was a large country in terms of plant resources, with one of the largest numbers of plant species in the world, and was rich in botanical resources, especially

Juniperus sibirica, which was particularly widely distributed in China. There were three domestically produced Juniper species in China:

Juniperus formosana Hayata,

Juniperus rigida S. et Z., and

Juniperus sibirica Burgsd, and the introduced Juniper was

Juniperus communis Linn [

1]. Juniper was a relatively short tree, generally 3–4 m tall; it was light-loving, cold-tolerant, and drought-resistant, and was mainly distributed in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Tibet [

2]. Juniper trees boast a striking appearance and are widely used as ornamental trees in gardens or as potted landscape plants. Additionally, their roots possess properties that clear heat, detoxify, dry dampness, and relieve itching, making them frequently employed as medicinal ingredients. Furthermore, junipers play multiple vital roles in soil conservation, particularly excelling in preventing soil erosion, improving soil structure, and maintaining ecosystem stability [

3,

4,

5,

6].

In China, Zheng Ziang [

7], Min Rui et al. conducted research on Juniper for gardening and potted ornamental planting, which was of great help for the efficient use of Juniper and for greening the environment. Luo Hong [

8] et al. studied the chemical composition of several Juniper species distributed in Qinghai Province and their biological activities, and the results showed that the main chemical components of Juniper genus species for wood quality evaluation were spicebush biflavonoids and kaempferin. Pan Hui-Qing [

9] and Cao Pan et al. measured the HPLC fingerprints of the Tibetan medicine Juniper and the biflavonoid content of

Fagus sylvatica, confirming that the establishment of HPLC fingerprints combined with the measurement of biflavonoid content, CP, and PCA methods could reasonably and effectively control the quality of Juniper, providing a scientific basis for the medicinal use of Juniper. Studies on the wood anatomy of Juniper were fewer in China at that time, and Jiazhuo Wang from Guangxi University had studied the stem and leaf anatomy of Juniper. Abroad, FANG O [

10] et al. explored the relationship between annual rings and precipitation by comparing drought signals recorded from Juniper wheel widths in Central and West Asia over the past four centuries. Both leaves and berries of Juniper spp. had hypoglycaemic as well as antioxidant properties [

11].

To better understand the growth responses of Asian tropical forests to climate change, it is particularly important to investigate the key scientific question of how the annual ring characteristics of Lijiang Juniper respond to precipitation variations. Currently, a comprehensive cultural reconstruction spanning from ancient to modern times based on archeology has not yet been established in Yunnan Province, China. Therefore, conducting dendrochronological research on Juniper trees represents a critically important research topic. As one of the widely distributed tree species in China, Juniper was studied for its wood anatomy to provide a more in-depth analysis of its properties, explore its value in timber use, discover the internal causes of defects in Juniper wood, improve the defects in the wood, and increase the value of its timber utilization and economic value. Therefore, this study was considered extremely necessary.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimens

This study focused on Juniper specimens (belonging to the Cupressaceae family, Juniperus genus, scientific name:

Juniperus formosana) in Baoshan Township, Yulong County, Lijiang City, Yunnan Province, China. Smartphone technology was employed to record the latitude, longitude, and elevation of sampling locations, with the north–south orientation clearly marked. Select representative Juniper specimens with moderate site conditions, intact tree growth, and trunks free of significant defects. Employ growth cones to sample at breast height (1.3 m above ground level), extracting tree cores as experimental material to study their annual ring characteristics. In addition, the trunks were intercepted as test materials, brought back to the laboratory, and placed in a ventilated and dry place to air-dry in order to study the anatomical structure of the wood. A total of seven Lijiang Juniper specimens were sampled in this study, including one from Yulong Snow Mountain and six from Baoshan Township. To investigate the radial variation patterns of Lijiang Juniper tree ring widths, six Juniper trees from the same location in Baoshan Township were specifically selected for analysis. Detailed information is provided in

Table 1.

2.2. Major Equipment

The instruments and equipment used in this experiment primarily include: a sliding microtome (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), growth cones, MH-300 density tester (Shanghai Minheng Trading Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), optical microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), Leica DM2000 digital microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), water bath, Leica M5080 microanalyzer (Leica M50, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany), LINTAB 6.0 tree ring analyzer (RINNTECH, Heidelberg, Germany), etc.

2.3. Slicing Test Method

A sectioning experiment was conducted to observe the microscopic characteristics of Lijiang juniper wood. Each Juniper specimen was sawn into a square shape, wrapped in gauze and labeled, and placed in an autoclave for steaming for about 24 h. Sections were made from three different cuts of the wood block and placed on clean slides. A drop of glycerine was applied to the slide, which was then pressed down with a coverslip and further pressed against the coverslip with a lead block. The pressed sections were removed from the slides and immersed in 1% Senna solution for staining for about 8–10 h. The sections were then removed from the staining solution and placed in glassware, after which they were dehydrated step by step by immersing them in 25%, 50%, 95%, and 100% ethanol solution for 5–10 min each, followed by immersion in a mixture of n-butyl alcohol and ethanol solution for 5–10 min. The dehydrated sections were then treated transparently with xylene for about 3 min. Intact transverse, radial, and chordal sections of the dehydrated material were selected, and neutral resin was dropped around the three sections of the slide in order, ensuring there were no air bubbles on the slide, the resin was evenly distributed, and there was no overflow of the coverslip. Finally, the finished permanent slides were placed in a dry and ventilated place to cure [

12,

13,

14].

2.4. Separation Test Method

Two small pieces of wood were intercepted from each Juniper test material, placed into test tubes, and numbered. A dissociative solution (glacial acetic acid-hydrogen peroxide) was added to the test tubes, which were then placed in a boiling water bath and heated for 3–4 h. The small pieces of wood were boiled to pure white fibers and then removed. The test tubes were filled with pure water after dissociation, washed several times repeatedly, and the dissociative solution was filtered out. An appropriate amount of pure water was added, and the test tube was shaken vigorously to disperse the fibers. The fibers in the test tube were then pipetted onto a clean slide and covered with a coverslip. Finally, the slides were placed under a digital microscope to observe the morphological characteristics of the fibers and measure 50 sets of data [

15,

16], from which the average values were calculated.

2.5. Juniper Annual Rotation Width Measurement

Firstly, 400 mesh, 800 mesh, 1000 mesh, and 1500 mesh sandpaper were used to sand the growth cone specimen in turn, smoothing and flattening the surface. Then, the spray gun blowing or tape paper pasting method was used to remove the wood shavings left in the hole of the tube cell due to sanding. The sanded growth cone specimens were then placed under the annual ring analyzer, where the magnification and position were adjusted so that the number of annual rings was clearly visible in the field of view. The computer-assisted software was activated to record the number and width of the observed annual rings into the system, and the data were exported for analysis at the end [

17,

18].

2.6. Determination of Air-Dry Density

Take representative samples from three Juniper specimens and process them into regular shapes (e.g., cubes, rectangular prisms). Place the samples in a constant temperature and humidity chamber and adjust them to air-dry equilibrium (typically achieved by balancing with ambient air; precise measurements require equilibration under standard conditions). Equilibrium is confirmed when two consecutive weighings conducted 24 h apart show a mass difference not exceeding 0.1% to 0.5%. Remove the conditioned specimens and immediately weigh their mass (m) using an electronic balance, accurate to 0.001 g. Wear gloves during this operation to prevent contamination from hand perspiration affecting results. Measure the length, width, and height of the specimen at different locations using a vernier caliper. Measure each dimension at least three times and calculate the average. Maintain the moisture content of juniper at 12%. Apply the density formula to calculate the air-dry density:

where:

—Air-dry density (g/cm3)

m—Air-dry mass (g)

v—Air-dry volume (cm3)

3. Results

3.1. Juniper Macro-Tectonic Characterization

3.1.1. Juniper Triple Cut Macro Features

Juniper’s three sections were observed by the naked eye or with 10× magnification [

19], as shown in

Figure 1A. In the cross section, many growth wheel textures were observed and were particularly obvious; the heartwood and sapwood were distinctly differentiated, with the sapwood being light yellowish-brown and the heartwood being reddish-brown. The wood rays were narrower, not obvious to the naked eye, and were slightly visible under magnification. Early and latewood were also slightly visible under magnification. As shown in

Figure 1B, on the radial section, parallel growth ring boundaries can be observed, and they are relatively distinct. As shown in

Figure 1C, parabolic-shaped grain patterns can be observed on the tangential surface.

3.1.2. Juniper Secondary Macro Features

- (1)

Color and luster: The color was light yellowish-brown to reddish-brown, and the surface luster was not obvious.

- (2)

Odor and taste: It had a weak aroma and no taste. (Aroma and flavor are secondary macrostructural characteristics of wood, determined by the olfactory system.)

- (3)

Hardness and density: The wood was of medium hardness, with hardness and density at an intermediate level. The air-dried density was 0.771 g/cm3.

- (4)

Grain, structure, and pattern: The grain was straight, the structure was fine, and there were no ripple marks. The distinct growth wheel boundaries formed a beautiful pattern in all sections.

- (5)

Medullary spots and color spots: It had a few medullary spots and color spots.

- (6)

Wood surface: Most of the wood surface was relatively full and smooth, with a few areas having grooves.

3.2. Juniper Microstructural Characterization

3.2.1. Juniper Triple-Cut Microfacets

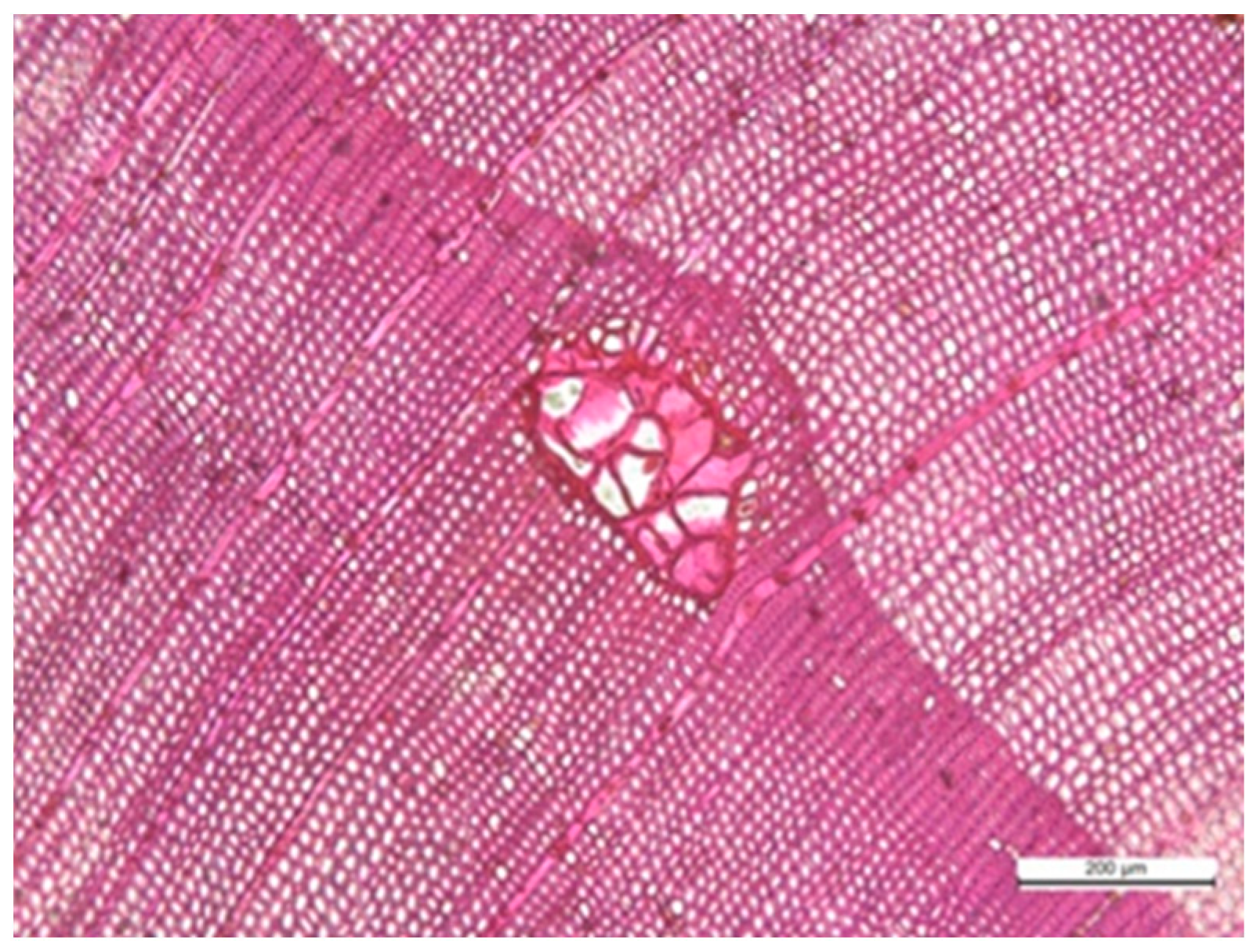

From the transverse section of

Figure 2, the morphology and arrangement of the tubular cells could be clearly seen. The axial thin-walled tissue was mainly distributed in a scattered pattern, the tubular cells contained inclusions, and the change from earlywood to latewood was a slow transition. From the radial section, a large number of traumatic resin tracts could be seen, and the tubular cell wall was densely ciliated with grain holes and crisscrossed with cross-fields. From the chordal section, the type of wood rays that could be seen was monoclinic wood rays, and the height of the wood rays was 3–5 cells. The wood ray cells contained a large amount of resin inside.

3.2.2. Morphological Characteristics of Tubular Cells

Axial tubular cells were narrow, thick-walled cells arranged along the main axis of the trunk in coniferous wood. The cell cavity was relatively small, the wall was thicker, and the cell ends were closed. The internal hollow cell cavity contained part of the inclusions. The overall shape was thin and long, and the tubular cell wall had a ciliated texture with holes, playing a role in channeling water and providing support. These cells were the main component of the coniferous wood, accounting for about 90% of the total volume of the wood.

As shown in

Figure 3, the morphological characteristics of the tubular molecules in Juniper wood in three sections were observed. In the earlywood zone, the tubular cells in the cross-section were round and oval, with some of the tubular positions slightly staggered. Before and after, the tubular shape became polygonal. In the latewood zone, the tubular cells were slightly aligned, mostly round and oval. The transition of Juniper from earlywood to latewood was slow, and the lumen of the tubules contained infill. Ciliated pores on the wall of the Juniper tubules could also be seen. The molecular fiber morphology of the tubular cells shown in

Figure 3d mainly displayed pointed cut ends, narrow cells, and abundant ciliated pores on the walls of the tubular cells [

20].

Tubular cell length and width are the primary characteristic parameters of tubular cells. Taking Juniperus chinensis BSX-2, BSX-3, and BSX-4 as examples,

Table 2 and

Table 3 present the data analysis of tubular cell length and width for the three specimens. Taking BSX-2 as an example, from the data in the table, it could be seen that: the maximum value of the length of the tubular cell was 1464.57 μm, and the minimum value was 451.61 μm. The extreme difference in the length of the tubular cell was relatively large, with an average value of 1010.36 μm, which belonged to the medium length of the tubular cell. From the point of view of papermaking, timber whose tubular cell length was greater than 900 μm was suitable for papermaking, and the average tubular length of the wood of

Juniperus chinensis was greater than 900 μm, making it suitable as a raw material for papermaking [

21]. The maximum value of the tubule width was 41.73 μm, the minimum value was 6.43 μm, and the average value was 22.58 μm. From the analysis of the data, it was concluded that the other two groups of data were in good agreement with this group of data, and the test conclusions were more reliable.

Through disintegration and sectioning tests, combined with a microscopic image analysis and processing system, characteristic data were measured. After calculating the average values, the length-to-width ratio of tracheids in Lijiang Juniper was determined to be approximately 50, making it relatively suitable as raw material for pulp and paper production. The wall-to-cavity ratio referred to the ratio of cell lumen to cell diameter, which was also a very important index in the papermaking process, related to the degree of abrasion resistance of paper. The wall-to-cavity ratio was associated with the water-absorbing and loosening capacity of paper, and the larger the wall-to-cavity ratio was, the better the paper produced. Juniper’s aspect ratio, wall-to-cavity ratio, and cavity-to-diameter ratio were all within the permissible range for papermaking, making it suitable as a raw material for papermaking [

22,

23]. Data analyses of specific tubular cell characteristics are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

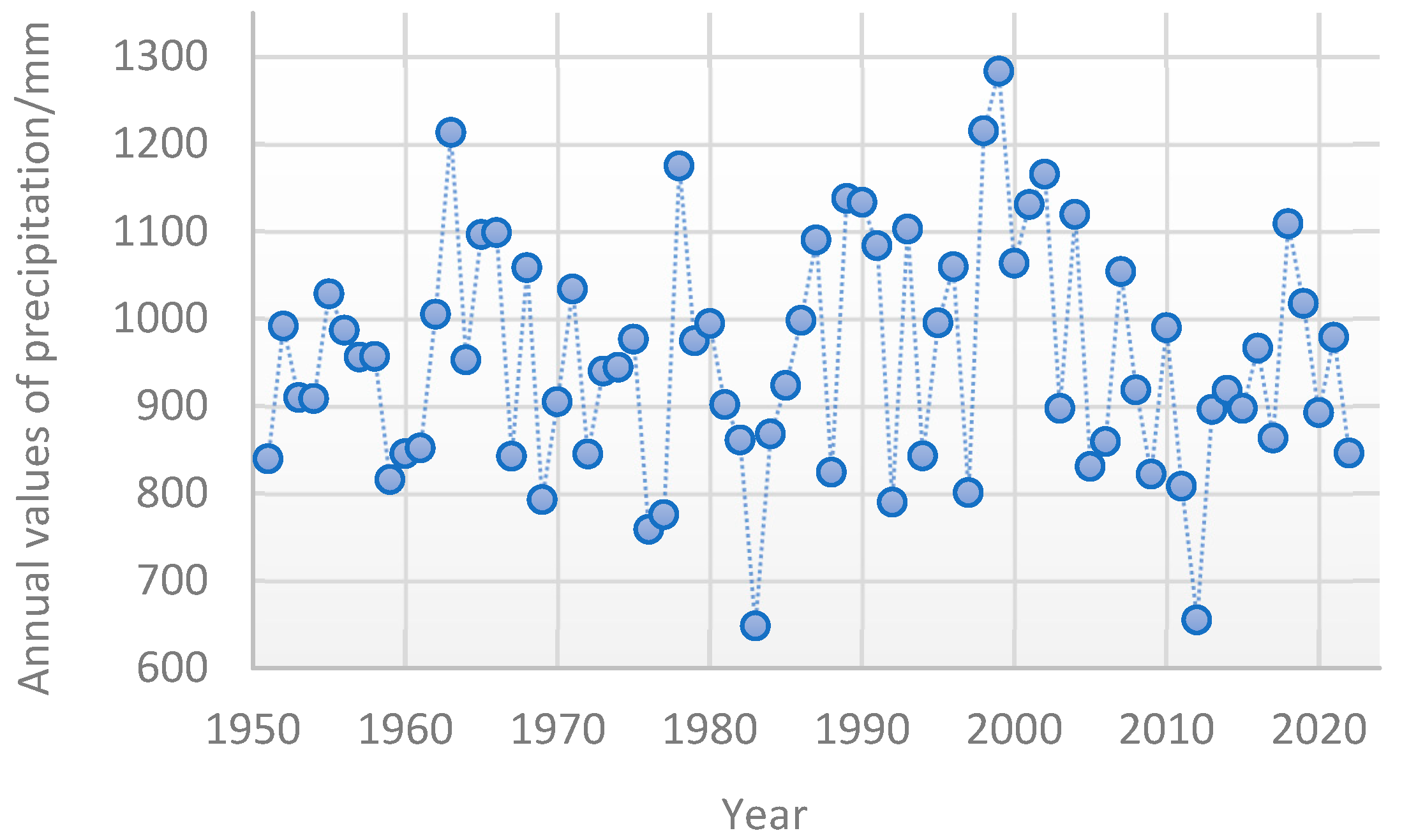

3.2.3. Morphological Characteristics of Thin-Walled Tissue

Juniper wood had a smaller amount of axial thin-walled tissue, visible only under the microscope, in a stellate distribution (

Figure 4). This tissue was thinner than the large walls of the tubular lumen, with a few brighter dots unevenly distributed in the growth whorls, which were observed under the 20× microscope.

3.2.4. Morphological Characteristics of Wood Rays

The type of wood rays of Juniper was uniseriate wood rays, with the height of the wood rays ranging from 2 to 5 cells, most of them being 2 to 3 cells, as shown in

Figure 5. The ray cells contained a small amount of resin, and there was a large number of cross-fields between axial tubular cells and wood rays, which were more obvious at 20× magnification. The cross-field stripe hole pattern was cypress-type, as shown in

Figure 6. The data of the wood rays were analyzed as shown in

Table 6.

3.2.5. Morphological Characteristics of the Resin Channel

Normal resin tracts in Juniper wood were few in number and uncommon, but traumatic resin tracts or healing tissue were present, as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

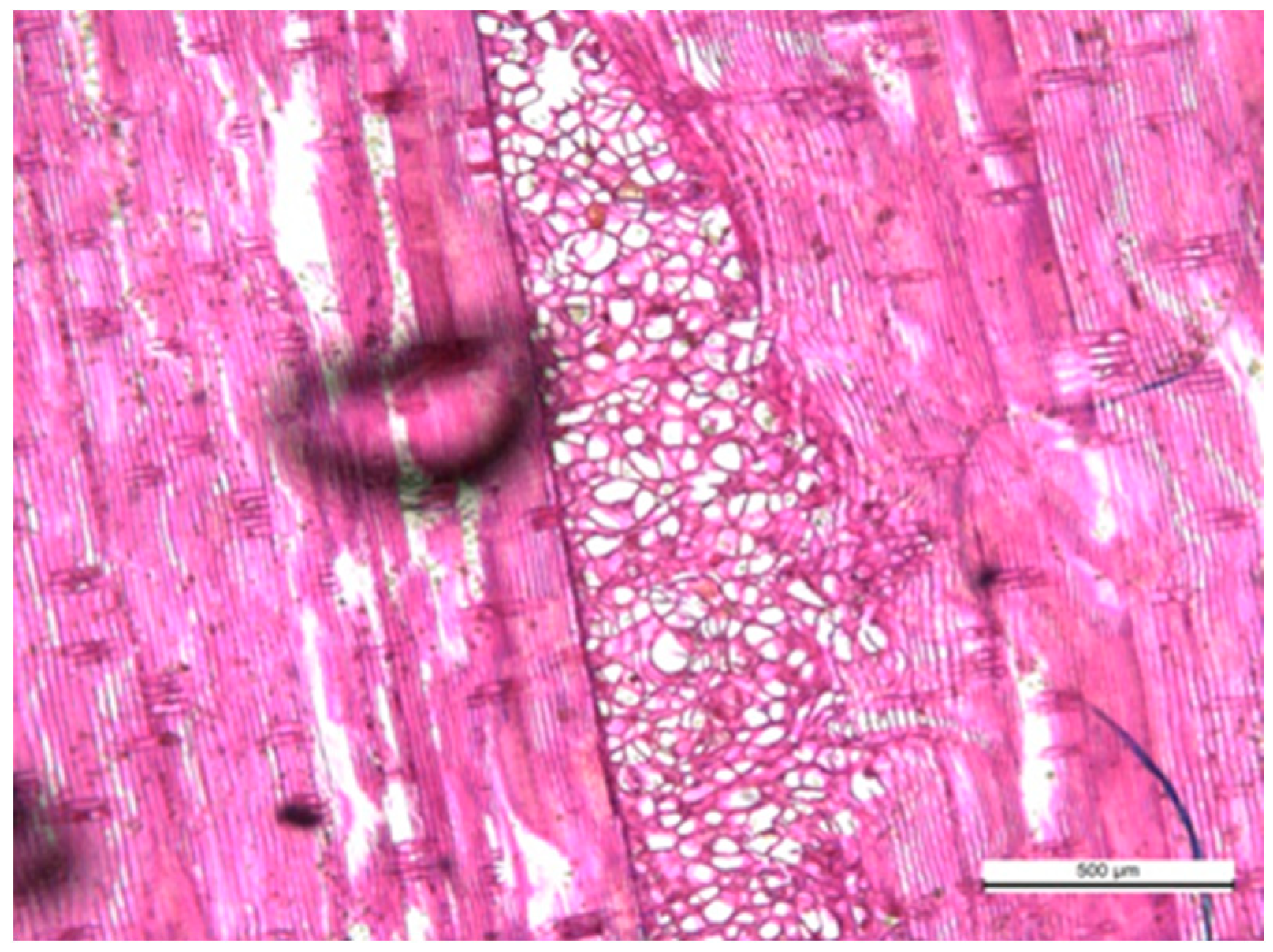

3.3. Lijiang Juniper Radial Variation in Annual Ring Width

The annual ring width responded to the radial growth rate of Juniper, and the speed of tree growth was affected by precipitation. By measuring the annual ring width of Juniper, not only could the age of Juniper and the radial growth width per year be derived, but also the mechanism of the response between the annual ring width and precipitation could be deduced based on the local precipitation in the past years. In addition, the study of Juniper’s annual rings also provided an important scientific basis in historical archeology, forestry research, geology, and public security crime solving.

Using a dendrochronology analyzer, we measured six processed Juniper samples from Baoshan Township and conducted data analysis on the obtained annual ring widths.

Table S1 displays the annual ring widths of six Juniper trees from Baoshan Township, Lijiang City. The trend of radial variation of annual ring width of Lijiang Juniper is shown in

Figure 9. For two Junipers of the same age, BSX-2 and BSX-3, the trend of radial variation of annual ring width was similar, and the fluctuation trend of their annual ring widths was very similar in the same time period.

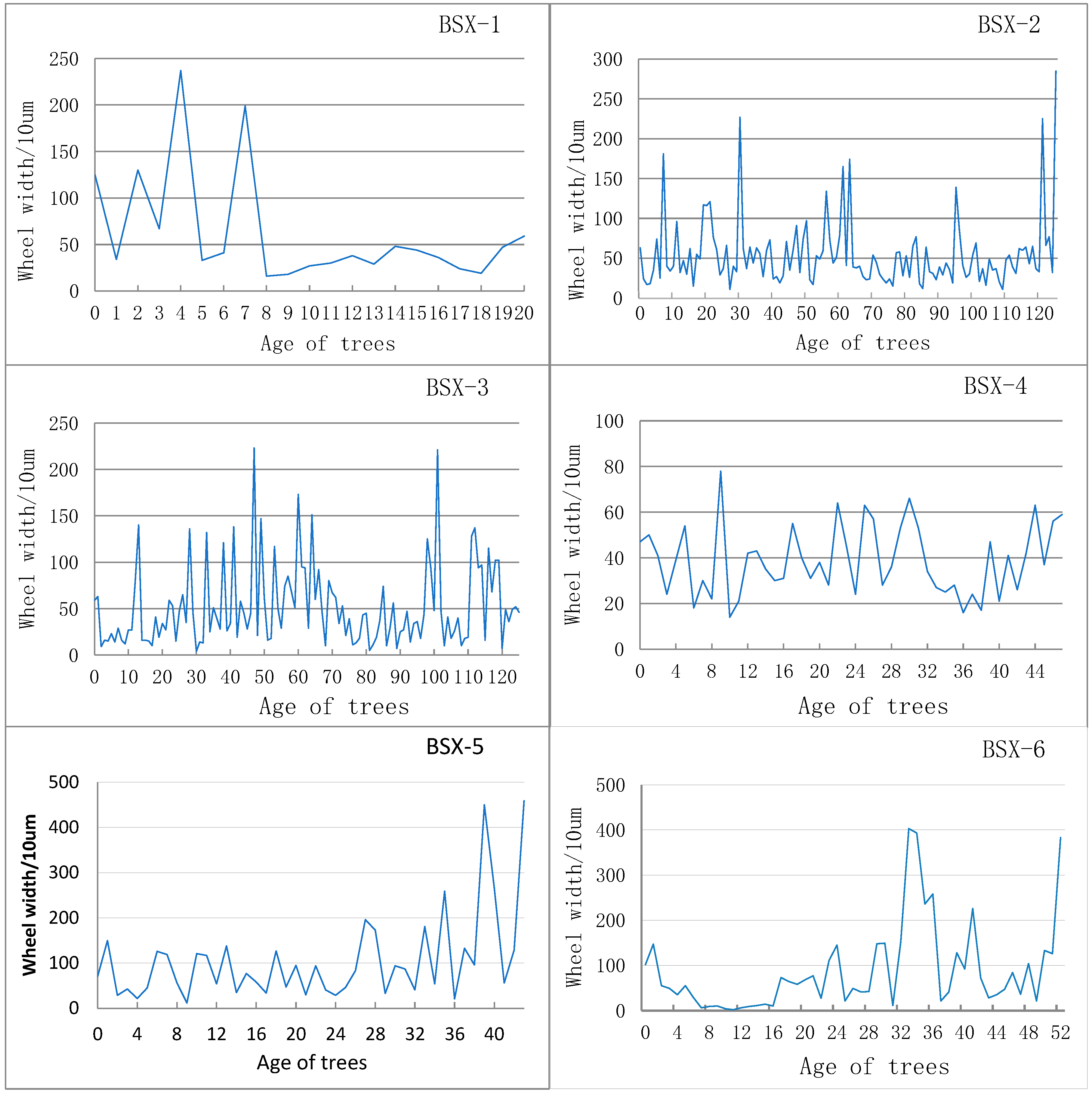

3.4. Correlation Between Juniper Annual Ring Width and Precipitation in Lijiang, China

3.4.1. Trends in Precipitation Variability in Lijiang

In the project study, the precipitation data obtained from the meteorological station “Lijiang Station No. 56651”, and its variation trend is shown in

Figure 10.

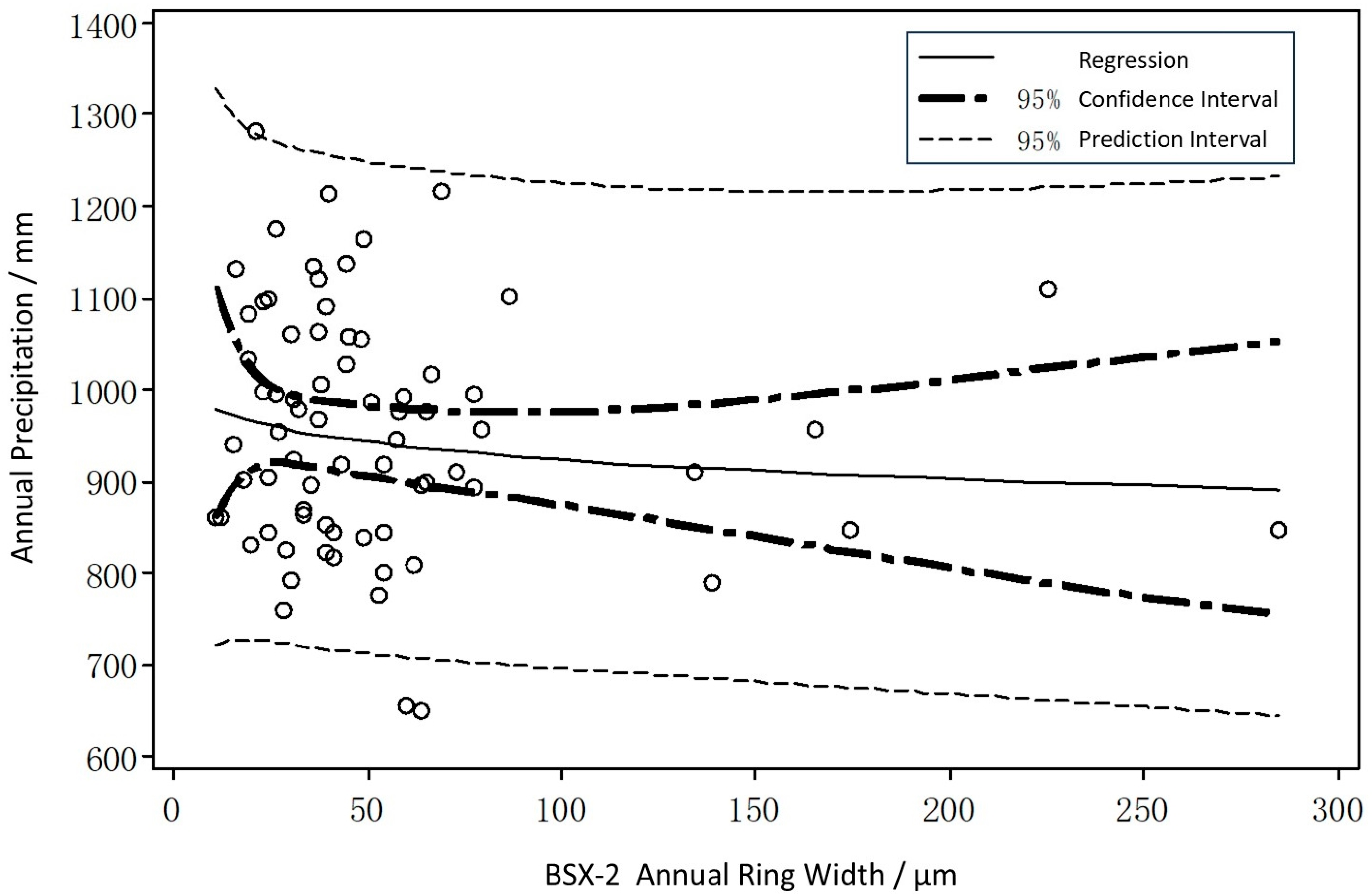

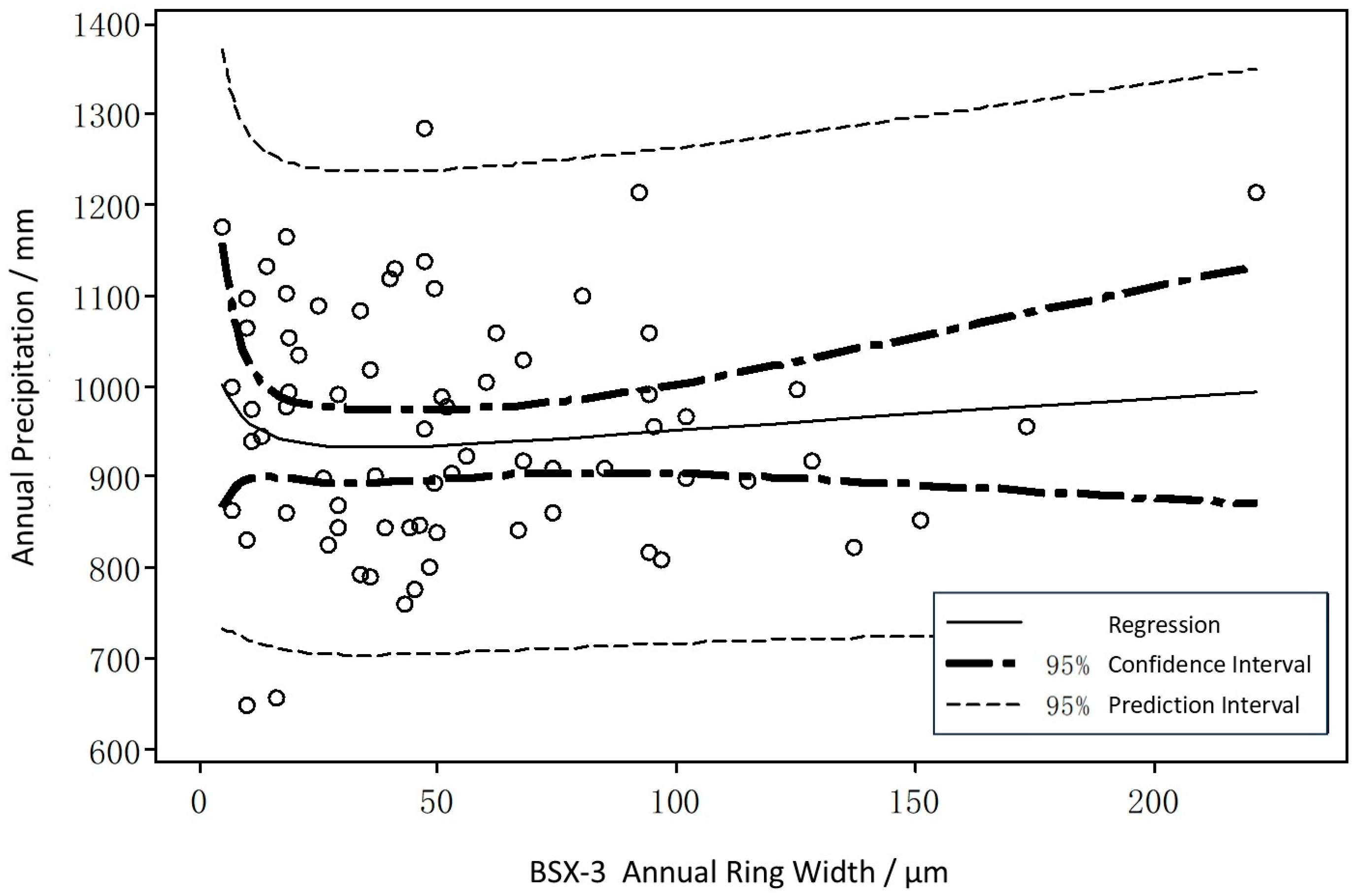

3.4.2. Correlation Between Juniper Annual Ring Width and Precipitation

Taking Juniper BSX-2 and BSX-3 as examples, their annual cycle widths were fitted to the precipitation data from the last 72 years, and the fitting plots of Juniper’s annual cycle widths and precipitation were obtained, as shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. It could be seen that the two fit well. Moreover, the correlation between Juniper annual ring width and precipitation is shown in

Table 7, with a correlation of y = a + bx + cx

2, and the correlation coefficients were 0.605 and 0.678, respectively. There was a strong correlation between Juniper annual ring width and precipitation at the 0.05 level.

4. Discussion

Juniper wood had a clear distinction between the heartwood and sapwood, with the sapwood being a broader yellowish color and the heartwood being a reddish-brown color, a characteristic that was consistent with the typical structural features of plants in the genus Juniper. The significant difference between sapwood and heartwood not only helped the plant to store nutrients during growth but may also have been closely related to the physical properties of the wood, such as density and hardness. In the study, it was noted that Juniper wood had a medium texture and an air-dry density of 0.771 g/cm3, which made it a moderately hard wood. This characteristic gave it a wider application potential in the fields of papermaking and construction, especially when used as a raw material for papermaking, where it showed better adaptability.

From a microstructural point of view, Juniper wood had tubular cells occupying about 90% of the tissue, and the small width of the tubular cells and the short molecular length indicated that it had some special characteristics in terms of moisture transport. The cypress-type cross-field grain pores and the small number of axial thin-walled tissues indicated that Juniper wood had high biomechanical properties and was able to withstand certain environmental stresses. In addition, the wood rays were uniseriate and 2–5 cells in height, which provided a basis for understanding the physiological functions of the wood. The presence of traumatic resin tracts may have been related to the plant’s self-repair mechanism when it was injured or exposed to pests and diseases, a characteristic that had some adaptive significance for the survival and reproduction of Juniper.

The study showed that the annual ring width of Juniper had a certain correlation with the amount of precipitation as measured by the tree annual ring analyzer. In particular, the annual ring widths of Juniper BSX-2 and BSX-3 showed a better fit with precipitation, with correlation coefficients of 0.605 and 0.678, respectively, indicating that, to a certain extent, precipitation had a significant effect on the growth of Juniper. As an important indicator of tree growth, annual ring width could reflect the growth environment and climatic conditions of plants in different periods [

24]. In Lijiang, precipitation was one of the most important factors limiting the growth of Juniper, especially in the dry season, and the variation of precipitation directly affected the annual ring width of Juniper, which had an important influence on its growth rate. The correlation between Juniper annual ring width and precipitation was positive, especially in the early growth stage of the annual rings, where an increase in precipitation could promote the growth of the trees and the formation of wider annual rings. This phenomenon was in line with the climatic characteristics of alternating wet and dry seasons and suggested that Juniper had a strong adaptive response to ambient precipitation. Higher precipitation usually meant an adequate supply of water, which in turn contributed to tree growth. In years of low precipitation, the annual ring widths were significantly reduced, further demonstrating the important role of water in Juniper growth.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the ecological adaptability of Juniper in the Lijiang region of Yunnan. Through adaptations in its anatomical structure and annual ring growth, Juniper is able to survive and reproduce in areas with significant climate variability. Furthermore, the width of Juniper tree rings exhibits a correlation with precipitation, represented by the equation y = a + bx + cx

2, with correlation coefficients of 0.605 and 0.678, respectively. This indicates a strong correlation between Juniper tree ring width and precipitation at the 0.05 significance level. The significant correlation between tree ring width and precipitation provides a basis for further research into the impacts of climate change on forest ecosystems [

25,

26]. Meanwhile, the significant correlation between annual ring width and precipitation provided a basis for further research on the effects of climate change on forest ecosystems. Future studies could further explore the effects of other climatic factors (e.g., temperature, humidity, etc.) on Juniper’s annual ring width, in order to fully understand the response mechanism of this species to climate change. The results of this study were of great significance to the management of forestry resources and ecological conservation in Yunnan. As a tree species with high ecological adaptability, the variation in annual ring width of Juniper could provide important information for local climate monitoring and water management. Meanwhile, the wood properties of Juniper also made it an important economic resource, and its potential applications in paper-making and construction industries could be explored in the future. Given Juniper’s sensitivity to precipitation, protecting water resources in the environment where Juniper grew, especially during the dry season, had important ecological and economic implications.

In this study, we analyzed the relationship between wood anatomical characteristics and annual ring width of Juniper in Lijiang, Yunnan Province, China, and the response of annual ring width to precipitation. The study showed that the anatomical characteristics of Juniper wood were ecologically adaptive, and that there was a significant correlation between annual ring width and precipitation, especially in drier years, when changes in precipitation had an important impact on the growth of Juniper. This finding provided valuable data for the ecological study of Juniper, climate change monitoring, and forest resource management. In the subsequent research on Juniper in Lijiang, we could also consider the aging of Juniper, the physiology of Juniper senescence, the diversity of the ecosystem, and the economic value, in order to improve the comprehensive use value of Juniper, realize the deep integration of natural resource protection and use, formulate reasonable protection measures, and safeguard the ecological security of forests.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the anatomical characteristics of Juniper from Lijiang, Yunnan Province, and its annual ring width in response to precipitation were investigated. Macroscopically, the heartwood and sapwood of Juniper were distinctly differentiated, with the sapwood being rather wide and yellowish, and the heartwood reddish-brown; the transition from the earlywood to the latewood was slow-varying; and the boundaries of the growth rings were obvious. From the microscopic point of view, the number of ciliated pores on the tubular cells was large, and the cross-field pores were cypress-type; the proportion of tissues in the tubular cells was about 90%, the width of the tubular cells belonged to a small level, and the length of the tubular cell molecules was short; the number of axial thin-walled tissues was relatively small, and it was distributed in a scattered type; the wood rays were uniseriate, and the height of the wood rays was 2–5 cells; there was the presence of traumatic resin tracts. According to the mean, standard deviation, and extreme deviation of Juniper wood tubular cells and wood rays, Lijiang Juniper was determined to be an excellent raw material for paper making. The ages of Juniper BSX-1, BSX-2, BSX-3, BSX-4, BSX-5, and BSX-6 in Lijiang BaoShan Township were 20, 125, 125, 47, 43, and 52 years, respectively, as determined by the tree annual ring analyzer. In the case of Juniper BSX-2 and BSX-3, for example, the fit between the annual ring widths and the amount of precipitation was high, with correlation coefficients of 0.605 and 0.678, respectively. The annual cycle width of Juniper and precipitation had a strong correlation at the 0.05 level. This indicates that Juniper’s radial growth is more sensitive to water supply.

Consequently, subsequent research can be conducted across four dimensions: “breadth” (more samples, larger regions), “depth” (from broad-scale to microscopic anatomy and multiple climatic factors), “application” (climate reconstruction, ecological disturbances, dating), and “interdisciplinary” (multi-species comparisons, carbon sink assessments). This approach will elevate Lijiang Juniper from a valuable climate response indicator to a comprehensive repository of information representing climate change, ecosystem processes, and human activity history in Northwest Yunnan, further establishing a Juniper tree-ring database for the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W.; methodology, X.Q.; validation, X.W. and J.Z.; formal analysis, J.Z.; resources, L.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Q. and Y.F.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and X.Q.; supervision, Y.F.; project administration, L.Q.; funding acquisition, L.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Scientific Research Foundation Project of Yunnan Province Education Department (2018JS344),Yunnan Province Agricultural Fundamental Research Joint Project (202101BD070001-129), and the “Xingdian Talent Support Plan” Young Talents Special Project of Yunnan Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the School of Materials and Chemical Engineering at Southwest Forestry University for providing the invaluable instrumentation and experimental environment. We also acknowledge the support and encouragement of all colleagues and friends who offered valuable suggestions throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, Z.P.; Wang, H.R. Classification and distribution of the Cypress family: Subfamilies, tribes and genera. J. Plant Taxon. 1997, 35, 236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.P.; Wang, H.R. Overview of introduced cypress species in China. For. Sci. Res. 1997, 10, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.C.; Zhang, S.Y. Compendium of Aromatic Plant Lists (XIV). Flavours Fragr. Cosmet. 2008, 02, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Shan, M.Q.; Ding, A.W.; Zhang, L. Progress in the Study of Medicinal Plants of the Cypress Family. Chin. Herb. Med. 2008, 31, 1765–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, K.B.; Luo, Y. Research on Container Nursery Technology of Large-Fruited Cypress in Gannan Plateau. For. Sci. Technol. Newsl. 2018, 6, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Z.F.; Yi, X.M.; Ruan, J.Y. Research on Seedling Technology of Large-Fruited Cypress in High Altitude Area of Ganzi. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2011, 32, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.A.; Min, R. Landscape Applications of Beijing Pine and Cypress Plants. Rural. Econ. Technol. 2018, 29, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Four Species of Cyperus Rotundus from Qinghai Province. Bachelor’s Thesis, North West Agriculture and Forestry University, Xianyang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.Q.; Cao, P.; Zhu, Y.B.; Wei, X.M.; Zhang, Y.S. HPLC fingerprinting and determination of biflavonoids in the Tibetan medicine Cyperus rotundus. J. Chin. Vet. Med. 2020, 39, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, O.; Zhang, Q.-B.; Vitasse, Y.; Zweifel, R.; Cherubini, P. The Frequency and Severity of Past Droughts Shape the Drought Sensitivity of Juniper Trees on the Tibetan Plateau. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 486, 118968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, N.; Deliorman Orhan, D.; Gökbulut, A.; Aslan, M.; Ergun, F. Comparative Analysis of Chemical Profile, Antioxidant, In-Vitro and In-Vivo Antidiabetic Activities of Juniperus foetidissima Willd. and Juniperus Sabina L. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.M. Timber Science; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.Q.; Yang, J.J.; Liu, P. Chinese Timber Journal; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.Y.; Shen, H.J.; Qiu, J. Comparison of the anatomical structure of two species of wood from the genus Rhododendron and analysis of the anatomical structure of Cotoneaster flatus. Guangxi For. Sci. 2017, 46, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Li, G.L.; Tan, B.M.; Mou, J.P.; Xu, F. Comparative study on the anatomical characteristics of wood of Phellodendron bidentata and Phellodendron bidentata. J. Northwest Coll. For. 2012, 27, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, C.H.; Qiu, J. Comparison of Anatomical Structures of Red Tsubaki and Simao Red Tsubaki Timber. Guangxi For. Sci. 2017, 46, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.X.; Zhang, D.Y. Methods and progress in the study of radial growth of trees. J. Nat. Sci. Harbin Norm. Univ. 2022, 38, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.J.; Guo, Z.C.; Su, F.; Zhao, Y.M. Research on the measurement method of annual rings width of trees based on digital image method. Ind. Instrum. Autom. 2017, 6, 75–77+96. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 29894-2013; General Principles of Wood Identification Methods. China National Standardisation Administration, Guangxi University: Nanning, China, 2013.

- Chang, S.S.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.B.; Wu, Y.Q.; Zhu, L.F.; Hu, Y.C. Anatomical structure and fibre morphology of the wood of the Eucalyptus caudatus lineage. Pap. Sci. Technol. 2007, 26, 1–5+38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H. Important achievements in the field of paper fibre morphology in the 20th century. Pap. Papermak. 1998, 24, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, J.; Luo, J.X.; Jia, C.; Qi, J.Q.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Huang, X.Y.; Xie, J.L. Characteristics and Physical and Mechanical Properties of Fir Tubular Cells in Dechang Area, Sichuan, China. J. Sichuan Agric. Univ. 2020, 38, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.F.; Yao, X.S. Study on the morphological structure of fibres on 33 domestic bamboo pulp applications. For. Sci. 1964, 9, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cregg, B.M. Growth and Physiological Responses to Varied Environments among Populations of Pinus Ponderosa. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 219, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H. A Study on the Effect of Climatic Factors on the Morphological Characteristics and Width of Annual Rings and Latewood Percentage of Cypress Wood Tubular Cells. Bachelor’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.L. Historical Changes in Key Hydroclimatic Elements Recorded by Tree Whorls in the Monsoon-Continental Climate Transition Zone of China. Ph.D. Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Juniper tri-section ((A): transverse section; (B): radial section; (C): chordal section).

Figure 1.

Juniper tri-section ((A): transverse section; (B): radial section; (C): chordal section).

Figure 2.

Juniper three-section microstructure ((a) is a cross section (5×); (b) is a radius section (10×); (c) is a chord section (10×)).

Figure 2.

Juniper three-section microstructure ((a) is a cross section (5×); (b) is a radius section (10×); (c) is a chord section (10×)).

Figure 3.

Morphological features of Juniper triple sectioned tubules with fiber morphology of tubule molecules. ((a) is the transverse section (40×); (b) is the radial section (40×); (c) is the chordal section (40×); (d) is the fiber morphology of the tubulin molecules).

Figure 3.

Morphological features of Juniper triple sectioned tubules with fiber morphology of tubule molecules. ((a) is the transverse section (40×); (b) is the radial section (40×); (c) is the chordal section (40×); (d) is the fiber morphology of the tubulin molecules).

Figure 4.

Juniper axial thin-walled tissue micromorphology (10×).

Figure 4.

Juniper axial thin-walled tissue micromorphology (10×).

Figure 5.

Juniper wood ray micromorphology (40×).

Figure 5.

Juniper wood ray micromorphology (40×).

Figure 6.

Juniper cross-field microscopic morphology (40×).

Figure 6.

Juniper cross-field microscopic morphology (40×).

Figure 7.

Trauma resin tract morphology.

Figure 7.

Trauma resin tract morphology.

Figure 8.

Healing tissue morphology.

Figure 8.

Healing tissue morphology.

Figure 9.

Trend of radial variation of Juniper annual ring width in Baoshan Township, Lijiang City, China (BSX-1 is 20 years old Juniper; BSX-2 is 125 years old Juniper; BSX-3 is 125 years old; BSX-4 is 47 years old; BSX-5 is 43 years old; BSX-6 is 52 years old).

Figure 9.

Trend of radial variation of Juniper annual ring width in Baoshan Township, Lijiang City, China (BSX-1 is 20 years old Juniper; BSX-2 is 125 years old Juniper; BSX-3 is 125 years old; BSX-4 is 47 years old; BSX-5 is 43 years old; BSX-6 is 52 years old).

Figure 10.

Trend of precipitation variability at Lijiang station No. 56651.

Figure 10.

Trend of precipitation variability at Lijiang station No. 56651.

Figure 11.

JuniperBSX-2 annual cycle width fitted to precipitation.

Figure 11.

JuniperBSX-2 annual cycle width fitted to precipitation.

Figure 12.

JuniperBSX-3 annual cycle width fitted to precipitation.

Figure 12.

JuniperBSX-3 annual cycle width fitted to precipitation.

Table 1.

Sampling Information Record Form.

Table 1.

Sampling Information Record Form.

| Sample Number | Sampling Location | Latitude and Longitude | Elevation (m) | Tree Height (m) | Canopy Width (m) | Diameter at Breast Height (cm) | Base Diameter (cm) | Slope Direction | Soil Types |

|---|

| CB-1 | Yulong Snow Mountain | 27° N, 100° E | 3250 | 1.2 | 1.1; 1.0 | 5.1 | 5.7 | sunny slope | Loess |

| BSX-1 | Baoshan Township | 27° N, 100° E | 2960 | 2.3 | 1.8; 1.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | sunny slope | Yellowish-brown |

| BSX-2 | Baoshan Township | 27° N, 100° E | 2918 | 3.5 | 2.1; 2.1 | 14.0 | 23.9 | sunny slope | grayish brown |

| BSX-3 | Baoshan Township | 27° N, 100° E | 2914 | 2.3 | 2.4; 2.4 | 11.5 | 12.1 | sunny slope | grayish brown |

| BSX-4 | Baoshan Township | 27° N, 100° E | 2914 | 4.1 | 1.8; 1.8 | 4.8 | 9.5 | sunny slope | grayish brown |

| BSX-5 | Baoshan Township | 27° N, 100° E | 2930 | 3.9 | 4.0; 3.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 | sunny slope | grayish brown |

| BSX-6 | Baoshan Township | 27° N, 100° E | 2900 | 3.2 | 4.0; 3.8 | 9.2 | 9.5 | sunny slope | grayish brown |

Table 2.

Tracheid length data analysis.

Table 2.

Tracheid length data analysis.

| Sample Number | Mean Tubule Length (μm) | Maximum Tube Cell Length (μm) | Minimum Tube Cell Length (μm) | Extreme Difference in Tubule Length (μm) | Standard Deviation of Tubule Length (μm) |

|---|

| BSX-2 | 1010.36 | 1464.57 | 451.61 | 1012.96 | 263.13 |

| BSX-3 | 842.05 | 1359.46 | 427.61 | 931.85 | 179.17 |

| BSX-4 | 1062.34 | 1402.61 | 550.06 | 852.55 | 183.97 |

Table 3.

Tracheid width data analysis.

Table 3.

Tracheid width data analysis.

| Sample Number | Mean Cell Width (μm) | Maximum Cell Width (μm) | Minimum Tube Cell Width (μm) | Extreme Difference in Tubule Width (μm) | Standard Deviation of Tubule Width (μm) |

|---|

| BSX-2 | 22.58 | 41.73 | 6.43 | 35.30 | 7.90 |

| BSX-3 | 19.02 | 27.15 | 3.48 | 23.67 | 5.05 |

| BSX-4 | 18.09 | 30.48 | 4.89 | 25.59 | 5.74 |

Table 4.

Table of analysis of inner diameter data of tubular cells.

Table 4.

Table of analysis of inner diameter data of tubular cells.

| Sample Number | Mean Internal Diameter of Tubular Cells (μm) | Maximum Inner Diameter of Tubular Cells (μm) | Minimum Inner Diameter of Tubular Cell (μm) | Tubule Inner Diameter Extremes (μm) | Standard Deviation of Inner Diameter of Tubular Cells (μm) |

|---|

| BSX-2 | 14.21 | 30.28 | 5.22 | 25.06 | 6.32 |

| BSX-3 | 13.78 | 19.88 | 2.70 | 17.18 | 3.72 |

| BSX-4 | 13.39 | 24.13 | 4.18 | 19.95 | 4.74 |

Table 5.

Tubular cell data analysis table.

Table 5.

Tubular cell data analysis table.

| Sample Number | Tubule Length (μm) | Tubule Width (μm) | Tubule Radial Double Thickness (μm) | Inner Diameter of a Tracheid (Botany) (μm) | Tubule Aspect Ratio | Tubular Wall-to-Lumen Ratio | Tubule Lumen-to-Diameter Ratio |

|---|

| BSX-2 | 1010.36 | 22.58 | 8.37 | 14.21 | 44.75 | 0.59 | 0.63 |

| BSX-3 | 842.05 | 19.02 | 5.23 | 13.78 | 44.28 | 0.38 | 0.72 |

| BSX-4 | 1062.34 | 18.09 | 5.70 | 12.39 | 58.72 | 0.46 | 0.68 |

Table 6.

Analysis of wood ray data.

Table 6.

Analysis of wood ray data.

| Sample Number | Mean Wood Ray Height (μm) | Maximum Wood Ray Height (μm) | Maximum Wood Ray Height (μm) | Wood Ray Height Extremes (μm) | Standard Deviation of Wood Ray Height (μm) |

|---|

| BSX-2 | 49.85 | 88.55 | 10.83 | 77.72 | 12.23 |

| BSX-3 | 53.01 | 105.74 | 15.05 | 90.69 | 16.70 |

| BSX-4 | 57.42 | 110.82 | 15.72 | 95.10 | 16.70 |

Table 7.

Correlation between Juniper annual ring width and precipitation.

Table 7.

Correlation between Juniper annual ring width and precipitation.

| Sample Number | Regression Line Equation (y = a + bx + cx2) | Correlation Coefficient | p-Value |

|---|

| BSX-2 | y = 3.007 − 0.0103x − 0.00535x2 | 0.605 | * |

| BSX-3 | y = 3.073 − 0.1330x + 0.0428x2 | 0.678 | * |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).