Abstract

Biological recolonization after cleaning remains a major challenge for the conservation of stone cultural heritage. As recolonization can start within months to a few years following intervention, developing rapid, field-deployable diagnostic approaches is crucial to better monitor microbial reappearance and to assess treatment performance in real time. Traditional evaluation methods lack the capacity to take into consideration non-cultivable microorganisms or assess functional traits relevant to recolonization. To bypass this gap, we applied on-site direct Whole-Genome Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore® MinION™ sequencer) coupled with colorimetric analysis to understand the microbiome, resistome, and metabolic traits of subaerial biofilms present in untreated and treated (recolonized) areas of stone statues at the “Largo da Porta Férrea” (Coimbra’s UNESCO World Heritage site). Colorimetric analysis (ΔE of 32–40 in recolonized vs. 19–43 in untreated areas) and genomic data pointed out that the applied treatment provided only a short-term effect (roughly 4–5 years), with a marked decline in fungi (1–2% vs. 7–18%), coupled with an increased recolonization mainly by Cyanobacteriota (circa 35–45%) and several stress-resistant Bacteria (globally ~95% of reads vs. 73–79% in controls). Antimicrobial resistance profiles significantly differed between sites, with treated areas showing distinct and unique resistance genes, and plasmids containing the blaTEM-116 gene, which can indicate potential adaptive shifts in the resistomes profiles after intervention. Metabolic pathways analysis revealed that untreated areas retained more complete nitrogen and sulfur cycling gene sets, whereas treated areas showed reduced biogeochemical gene contents, consistent with earlier-stage recolonization steps. Given the current recolonization detection and the ongoing biofilm formation, routine monitoring efforts (e.g., every 6 months) are recommended. Overall, this study demonstrates the first on-site genomic characterization of recolonization events on heritage stone, providing a practical prompt-warning tool for conservation monitoring and future biofilm management strategies.

1. Introduction

Outdoor exposed stone monuments and relics are particularly susceptible to biological colonization and biodeterioration. The settling of airborne particles, dust, spores, cells, and other biological propagules, coupled with the influence of environmental conditions such as humidity, temperature, and light exposure, enables the development of subaerial biofilms (SABs). Together with abiotic factors, these biofilms can contribute to stone’s physical, chemical, and aesthetic deterioration, compromising the integrity of cultural heritage materials [1,2,3,4,5]. For this reason, the shared goal of cultural heritage biodeterioration (CHB) studies is to provide and evaluate solutions that can either prevent, restore, control or delay microbial proliferation and their biodeteriorative effects [6]. Stone conservation approaches encompass both prevention and control methodologies. Prevention strategies aim to hinder microbiological development by disrupting nutrient availability or environmental conditions, while control approaches seek to suppress or reduce microbial growth and delay recolonization events [6,7]. The prevention of biological growth can involve simple measures such as the stabilization of climate conditions and effective ventilation or more complex interventions, such as the application of water repellants and the construction of preventive shelters [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Control methodologies can employ physical, chemical, and biological interventions. Physical eradication of microorganisms can be performed using methods such as electromagnetic wavelengths, laser, gamma radiation, temperature interference, and mechanical cleaning. Alternatively, chemical interventions imply the application of chemical biocides or metallic nanoparticles, while biological methods entail the use of natural biocidal and antagonistic compounds [6,7,13,14,15].

Despite these resources, recolonization after intervention is still one of the most difficult challenges that conservators currently face [16,17]. This undesirable microbial regrowth can occur through two main mechanisms: by the surviving indigenous microorganisms that developed resistance; and/or by microorganisms that can take advantage of dead biomass and residues of biocides, consolidants, and water repellents [6]. Reliant on the environmental conditions and the lithotype, recolonization can begin soon after treatment, since the remains of organic residues, the presence of humidity, light exposure, the proximity to vegetation, and the presence of a new substrate free of competitors allows biological regrowth [6,16]. The context of the intervened objects or monuments also plays a significant role, since weather conditions, microclimatic variables, monument’s surface alignment, and the presence of sheltered environments can also profoundly affect the rate and diversity of recolonizing microorganisms [16,17]. In fact, shaded areas, moisture-retaining zones, and facades with high incident light exposure often exhibit markedly different recolonization rates [16,17]. Thus, treatment performance can vary widely, with some biocidal or consolidant applications maintaining reduced colonization for several years, while others can result in visible regrowth within a few months [16,17].

Despite undeniable valuable, traditional methods applied to assess biodeterioration (e.g., visual inspection, microscopy, colorimetry, and culture-dependent approaches) are limited by their ability to detect non-culturable microorganisms, comprehensible understand microbial community dynamics, or identify functional genes related to recolonization and resistance. Due to their abilities to bypass these limitations, molecular biology methodologies such as Next-Generation-Sequencing (NGS), have become widely applied to study cultural heritage (CH) microbiomes in various environments and substrates [18,19,20,21]. Considering their microbial DNA high-resolution analysis capabilities, these techniques can be essential for the characterization of microbial communities before and after cleaning interventions. However, the number of reports detailing a thorough molecular examination of recolonization events or the evaluation of treatment effectiveness are still reduced. Jroundi and colleagues [22] evaluated the bacterial diversity (Illumina) in deteriorated tuff stones and lime plasters in an archeological Mayan site, after the application of sterile M-3P nutritional solution. They verified significant bacterial changes in the treated stones and confirmed the efficiency of this bio-conservation approach. In the consequent study conducted by Elert and colleagues [23], Illumina methods were also applied to further demonstrate the efficiency of bio-consolidation treatments in Copan stones from the same Mayan sites. Another research work conducted by Villar de Pablo and colleagues [24] studied the efficiency of biocide-based treatments on microbial colonization of a dolostone quarry using metabarcoding approaches (Illumina) coupled with microscopical techniques. The authors found that different treatments led to substantial taxon-dependent changes in the bacterial and fungal communities’ abundance profiles, with a particular impact on the mycobiome in the long-term. The work of Zhang and colleagues [25] simultaneously applied DNA and RNA analysis (Illumina) of microorganisms rapidly propagating after the installation of a protective shade in the Beishiku Temple (China). They were able to characterize the microbial communities in newly formed black and grey spots and determine that the installation of the protective shade prompted a decrease in temperatures and an increase in humidity, which in turn resulted in an exponential proliferation of indigenous cyanobacteria. Kratter and colleagues [26] used metabarcoding (Oxford Nanopore®) to characterize the fungal involvement in black spot formation in the Tomba degli Scudi atrium (Italy) after the removal of moonmilk deposits. They were able to confirm the presence of fungal species contributing to the development of these biodeterioration phenomena. Méndez and colleagues [27] applied Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) (Oxford Nanopore®) to identify shifts in the microbiome and in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes induced by artificial lighting on granite monuments. Tichy and colleagues [28] tested poultices in two historic buildings and evaluated microbial shifts with long read 16S rRNA amplicon analysis (Oxford Nanopore®), verifying that salt load and ionic composition during and after treatment impacted the Prokaryotic communities, with an enhanced effect on Bacteria. More recently, Maisto and colleagues [29] used WGS (Oxford Nanopore®) to understand how restoration biocides and routine street cleaning affected microbial communities on granite facades of historic buildings in Santiago de Compostela, finding that antibiotic and biocide resistance genes persisted mainly in areas previously treated (15 years ago) with biocides.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate the growing potential of molecular tools, from early Illumina-based to recent Oxford Nanopore® applications, for monitoring microbial communities on cultural heritage materials. However, most of the existing work is focused on elucidating community structure post-intervention, rather than directly evaluating recolonization dynamics or comparing non-intervened and recently treated surfaces in real environmental conditions. Furthermore, the Oxford Nanopore® MinION™ sequencer ability for on-site real time analysis can enable diverse monitoring applications within the field of CHB that remain unexplored [30]. The present work addresses these gaps by applying an on-site WGS approach to evaluate recolonization processes and functional shifts in microbial communities following conservation interventions. To this end, we conducted the first comparative analysis of non-intervened (NI) vs. recently intervened (with recolonization) (RI) areas, using our recently proposed on-site direct WGS protocol [31]. Samples of NI and RI areas were collected from stone statues at the “Largo da Porta Férrea” (Coimbra’s UNESCO World Heritage site) and analyzed through colorimetric measurements, on-site WGS, and bioinformatic analysis, to (1) characterize and compare the microbial communities, resistome, and metabolic traits of untreated and treated (recolonized) stone surfaces; (2) access if the applied cleaning treatment effectively delayed recolonization; and (3) to evaluate the feasibility of the applied approach as a diagnostic tool for conservation monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Site Description and Sample Collection

The “Largo da Porta Férrea” (GPS: 40°12′28.2″ N 8°25′30.7″ W) comprises the area associated with the classical entrance to the Coimbra’s University premises (“Porta Férrea” or Iron Gate). The gated entrance (completed in 1634) constitutes one of the first major works undertaken by the University after the acquisition of the building complexes in this location. In this area, the “Medicina” statue (GPS: 40°12′28.9″ N 8°25′29.2″ W) is located near the former Faculty of Medicine, while the “Artes Liberais ou Estudo” statues (GPS: 40°12′28.2″ N 8°25′29.7″ W) are located near the general library of the University of Coimbra (GPS: 40°12′27.9″ N 8°25′26.3″ W). Both statues have been constructed in 1956 with limestone. Moreover, they have recently (2019 to 2020) been the focus of undisclosed cleaning interventions. While the exact nature of these interventions remains unidentified, they were likely physical, but the possibility of chemical applications cannot be ruled out. This uncertainty adds further difficulty to precisely investigate and interpret recolonization mechanisms in this specific case study. Nonetheless, these statues are currently displaying notorious signs of biological recolonization. In this area, the development of darkened biofilms is observable, enhanced by rainwater runoff and pollution.

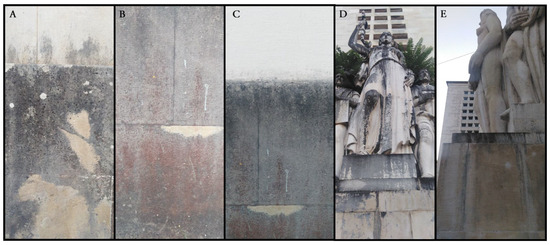

For this study, a total of five samples were collected at the “Largo da Porta Férrea”: three samples were taken from biofilms within areas without interventions (C1, C2, and C3; NI samples); and two samples were taken from biofilms where recent interventions were conducted (R1 and R2; RI samples). Control samples C1 and C3 were obtained from darkened areas, while control sample C2 was obtained from a darkened and reddish surface from the walls of the general library of the University of Coimbra (Figure 1). Samples from previously cleaned areas were obtained from the statues “Medicina” (sample R1) and “Artes Liberais ou Estudo” (sample R2). Sampling was carried out by carefully scraping or detaching the loosened biofilm regions with a sterile scalpel into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube (~0.2 g), stored in insulated boxes containing ice packs (4 ± 2 °C) while transported to the mobile laboratory (15 min) and then immediately processed for analysis.

Figure 1.

Details of the sampling sites considered, as follows: (A–C) show control samples C1, C2, and C3, respectively (retrieved from the walls of the general library of the University of Coimbra); (D) sample R1 retrieved from the “Medicina” statue; and (E) sample R2 retrieved from the “Artes Liberais ou Estudo” statue.

2.2. Colorimetric Analysis

Three fixed points (by sample) located in the immediate vicinity of the microbial sampling site were marked and used for colorimetric analysis, ensuring comparability between microbial and colorimetric results. Controls from non-colonized nearby surfaces were also considered for calculations. Colorimetric analysis of the samples was performed in situ with a portable CM-700d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Measurements were conducted with an 8 mm aperture and taken in triplicate in the selected points. The CIELAB system quantified stone surface color through three parameters: L* (lightness), a* (red–green color) and b* (yellow–blue color), with total color variation (ΔE*) being calculated with the formula: ΔE*ab = [(ΔL*)2 + (Δa*)2 + (Δb*)2]1/2. The ΔE values were interpreted using general perceptual thresholds: ΔE < 1.0 is considered imperceptible, 1.0–2.0 perceptible to trained observers, and >2.0 perceptible to most viewers.

2.3. Molecular Analysis

2.3.1. Laboratory Context

For the molecular analysis, we considered an “on-site” analysis approach [31]. For this purpose, a mobile laboratory was established in a private office at the São Bento building (at the department of Life Sciences of the University of Coimbra, about 300 m from the sampling area). The setup included a Bento Lab Pro suite (https://bento.bio/), a Quantus fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), a Styrofoam box with frozen gel packs, an internet connected mobile phone, and an Oxford Nanopore® MinION™ Mk1B sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) connected to a ASUS TUF Gaming A16 laptop (FA607PV-R97B46CS1) [31]. To ensure cleanliness control and contamination prevention, all equipment surfaces were regularly sterilized with 70% ethanol and manipulation within the sterile zone near a flame. Sterile gloves, pipette tips, and other consumables were used throughout, with negative controls being processed in parallel with field samples to monitor potential contamination.

2.3.2. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Metagenomic Sequencing

The DNA of the samples was extracted utilizing the Nucleospin® Soil Kit (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany) in conjunction with Buffer SL1 and Enhancer SX, following the manufacturer’s protocol, but considering several modifications to bypass the Bento Lab Pro 8KG maximum centrifugation capacity [31]. As such, centrifugation times were increased in a fourfold manner, the elution phase was performed over a period of five minutes and the final DNA elution volume was adjusted to 35 µL (to ensure higher nucleic acid concentrations, suitable for downstream library preparations) [31].

The extracted High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA was then quantified using a Quantus fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in conjunction with the QuantiFluor® dsDNA Dye kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to access HMW DNA quality, using a Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer system (0.5% TBE solution with 0.5 g agarose), stained with GreenSafe Premium (NZYTech™, Lisbon, Portugal) and run at 80 V for 45 min in the Bento Lab Pro electrophoresis respective unit [31].

Prior to sequencing, DNA samples were pooled to achieve equimolar concentrations, with the WGS libraries being prepared with the Rapid Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-RBK114.24) Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK), following the manufacturer’s protocol. To comply with the company guidelines, three samples tagged with four barcodes were considered for each flow cell. Barcode ligation was carried out using the Bento Lab Pro suite’s thermocycler unit [31], with the WGS sequencing being conducted in a R10.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN114) over 24 h using the MinION™ Mk1B device connected to the ASUS TUF Gaming A16 laptop (FA607PV-R97B46CS1).

Data acquisition and processing were managed via the MinKnow software (v.24.06.5), with basecalling performed using Guppy (v.6.5.7) in Super accurate (SUP) mode. This analysis also included barcode adapter removal and exclusion of raw reads exhibiting a mean quality score below 10 and length shorter than 1000 bp.

2.3.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

Read Quality Evaluation

Read quality analyses and sequencing metrics evaluation were conducted in the Galaxy web-based platform [32], via NanoPlot (v.1.43) [33].

Read Processing, Taxonomic Classification, and Metagenomic Binning

Subsequent analysis, including contig binning, retrieval of assembly and coverage statistics, plasmid detection, multi-locus sequencing typing, and prediction of antimicrobial (AMR) genotypes, were obtained with the BugSeq/BugSplit web platform, using the BugSeq Ref Curated database [34,35]. Taxonomic classification was generated in read-based mode, which aligns nanopore reads against the curated reference database using Minimap2 and performs Bayesian reassignment (Pathoscope) and a lowest common ancestor (LCA) procedure using Recentrifuge [34,35].

Data Processing, Diversity Metrics Evaluation, and Statistical Analysis

The obtained data was initially visualized with Pavian [36] and converted into a Biom file with Kraken-biom [37] in Galaxy [32]. This file was further converted into an operational taxonomic unit (OTU)-like table through the application of a combination of the Easy16S [38] and the ExploreMetabar (v.2.0.1) [39] web platforms. ExploreMetabar [39] was further applied to obtain alpha (Observed, chao1, Shannon, and Simpson) and beta diversity measures (distance-based, Bray–Curtis, and PCoA). Statistical analysis to determine significant differences in the diversity measures obtained was achieved through ANOVA coupled with TukeyHSD testing and PERMANOVA coupled with Adonis examinations, also using ExploreMetabar [39].

Bin Evaluation, Annotation, and Functional Analysis

Obtained bins from the BugSeq/BugSplit [34,35] analyses were evaluated with Quast (v.5.2) [40], annotated with Prokka (v.1.14.6) [41] and their functional characterization performed with the EggNOG Mapper (v.5.0.2) [42] (with default parameters) in Galaxy [32]. For metabolic analysis, GhostKoala [43] was used to map gene products functional roles with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

AMR Gene Profiling and Annotation

Initial AMR genes were identified through the integrated ResFinder module as implemented in the BugSeq/BugSplit workflow [34,35]. Additional AMR profiling was obtained through blast analysis against the MEGARes database (v.3.0.0) [44], as similarly conducted by He and colleagues [45]. Additionally, hits containing “Requires SNP confirmation” annotations were removed from the final dataset, following the MEGARes manual.

Additional Data Plotting and Statistical Analysis

Data plotting was also obtained with Krona [46] and the SRPlot [47] web platform. Likewise, some additional statistical analyses were conducted with the past5 software (https://www.nhm.uio.no/english/research/resources/past/ accessed on 3 November 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Biofilm Colorimetric Analysis

The results obtained for the colorimetric measurements can be found in Table 1. In general, the data attained showed that the recolonized areas exhibited some differences when compared with the controls (ΔE). The results highlighted that the RI samples were slightly distinct from the NI samples, showing a darker coloration (L*/luminosity decrease), while also mirroring an alteration of the surface’s appearance (high ΔE values). Additionally, the values of the a* (red–green) and b* (yellow–blue) colors were generally higher among NI samples and lower (and more similar between themselves) for RI samples. Moreover, all ΔE largely surpassed 2.0, pointing the presence of drastic visual changes in all sampling points considered. Statistical evaluation of the colorimetric values obtained through ANOVA calculations revealed that the p-values were 0.2256 for L*, 0.3464 for a*, 0.3193 for b*, and 0.4441 for ΔE. Considering these results, no statistically significant differences between NI and RI for any of the color metrics could be identified.

Table 1.

Colorimetric results obtained for each sample.

3.2. Microbiome Analysis

3.2.1. Overall Statistics and Diversity Measures

The overall read and contig/bin metrics and statistics can be found in Supplementary Table S1. In general, the obtained reads ranged from 20,138 to 78,886, while the assembled contigs numbered 18, 809, 33, 359, and 319, having N50 values of 3426, 30,342, 7267, 4704, and 13,509 for samples C1, C2, C3, R1, and R2, respectively. Overall, median Read Phred Scores were of 17 for all samples, except for sample C3, for which the value was 16.

The results obtained for the alpha diversity indexes are presented in Supplementary Table S2. They highlighted that the NI samples show moderate to high species richness and diversity (Observed ranging from 149 to 339 and Shannon index ranging from 3.903 to 4.386), with the species being evenly distributed (Simpson index ranging from 0.961 to 0.975). On the other hand, the RI samples displayed variable species diversity and richness (Observed being 146 and 304 and Shannon index being 3.466 and 4.638), with the indexes for R2 surpassing the values associated with NI control samples. Moreover, due to the Simpson indexes verified (R1 (0.940) and R2 (0.981)), the results also highlight variable evenness distributions, with the sample R2 exhibiting a more well-balanced microbial community. Nonetheless, ANOVA coupled with TukeyHSD did not reveal statistical differences for the microbial community’s alfa diversity measures considered (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of ANOVA and TukeyHSD post hoc results for Shannon, Simpson, and Chao1 diversity indices.

3.2.2. Microbiome Composition

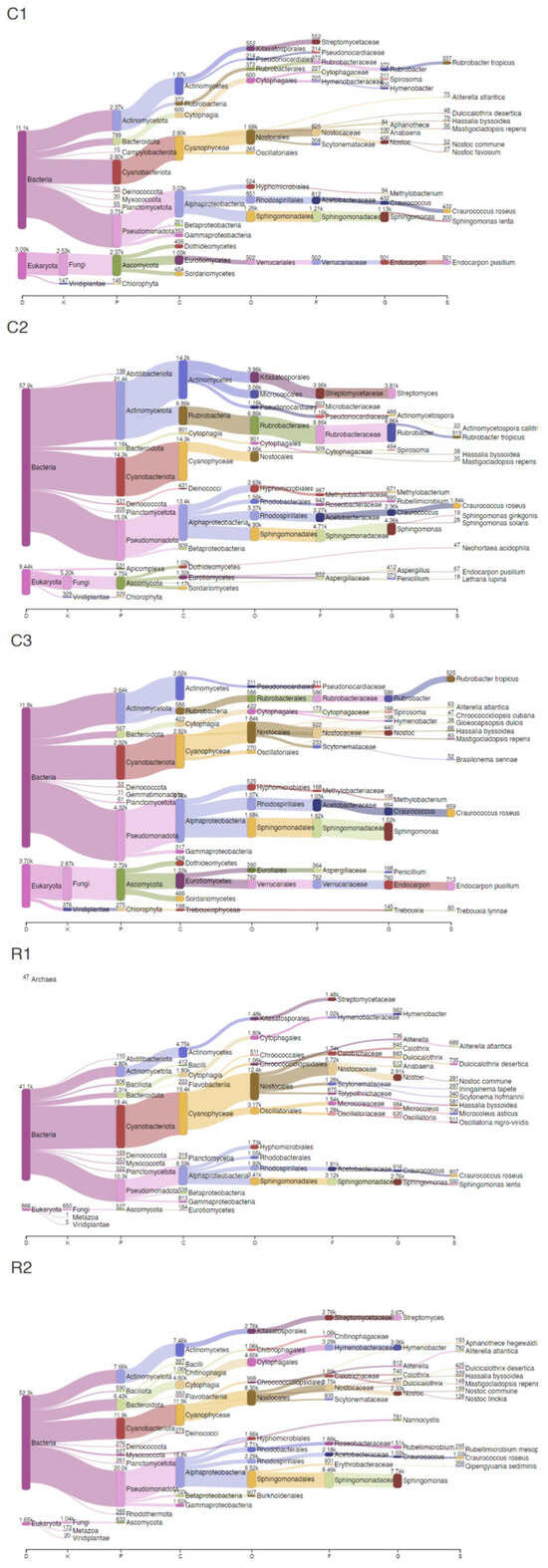

The results concerning microbiome composition and abundance details are presented in Figure 2 and in Supplementary File S1. BugSeq/BugSplit classified 98.9% (C1), 99.4% (C2), 97.6% (C3), and 99.8% (R1 and R2) of the total obtained reads for each sample (Supplementary Table S3). In addition, the software identified the higher number of bacterial reads in sample R2 and of fungal reads in sample C3.

Figure 2.

Sankey plots of the main taxonomic groups identified in each sample.

Bacteria accounted for 73–79% in NI and 95% in RI areas, while Eukaryota comprised 13–23% in NI and 2–3% in the RI samples. Additionally, Fungi percentages ranged between 7–18% in NI and 1–2% in RI, while Chlorophyta values were found to be between 1–2% in NI and 0.01–0.04% in the RI zones. Overall, the top five genera detected in all samples were assigned to Sphingomonas, Rubrobacter, Streptomyces, Hymenobacter, and Nostoc, while the main species detected were Craurococcus roseus, Rubrobacter tropicus, Aliterella atlantica, Dulcicalothrix desertica, and Endocarpon pusillum.

When looking at the results with more detail, the microbial composition in NI areas were predominantly characterized by Pseudomonadota (C1: 25%; C2: 20%; C3: 27%), Cyanobacteriota (C1: 19%; C2: 20%; C3: 18%), Actinomycetota (C1: 16%; C2: 29%; C3: 16%), Ascomycota (C1: 16%; C2: 6%; C3: 17%), and Bacteroidota (C1: 5%; C2: 2%; C3: 3%). Furthermore, microorganisms affiliated with Sphingomonas (C1: 8%; C2: 6%; C3: 9%), Endocarpon (C1: 3%; C2: 0.09%; C3: 4%), Craurococcus (C1: 3%; C2: 3%; C3: 4%), Nostoc (C1: 3%; C2: 0.2%; C3: 3%), Rubrobacter (C1: 3%; C2: 9%; C3: 4%), and Streptomyces (C1: 0%; C2: 5%: C3: 0%) were significantly prevalent within these samples. The principal annotated species for these areas included Endocarpon pusillum, Craurococcus roseus, Rubrobacter tropicus, Sphingomonas lenta, Hassalia byssoidea, Mastigocladopsis repens, and Neohortaea acidophila.

On the other hand, the microbial composition of the RI areas was predominantly characterized by Pseudomonadota (R1: 24%; R2: 36%), Cyanobacteriota (R1: 45%; R2: 22%), Actinomycetota (R1: 11%; R2: 14%), Bacteroidota (R1: 5%; R2: 12%), and Bacillota (R1: 1%; R2: 1%). Microorganisms affiliated with Nostoc (R1: 7%; R2: 4%), Sphingomonas (R1: 6%; R2: 14%), Hymenobacter (R1: 2%; R2: 6%), Craurococcus (R1: 2%; R2: 2%), Streptomyces (R1: 0%; R2: 5%), Rubellimicrobium (R1: 0.9%; R2: 3%), and Microcoleus (R1: 2%; R2: 0.09%) were significantly prevalent within these samples. The principal annotated species for these areas included Craurococcus roseus, Dulcicalothrix desertica, Microcoleus asticus, Aliterella atlantica, Hassalia byssoidea, and Qipengyuania sediminis.

Despite the differences noticed in the taxonomic composition, the results of the PERMANOVA coupled with Adonis examinations did not reveal significant statistical differences for the microbial communities between NI and RI areas (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of PERMANOVA coupled with Adonis examinations for the beta diversity measures.

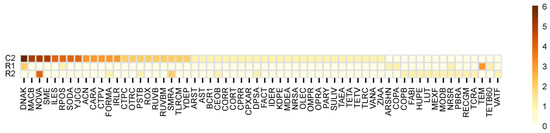

3.2.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Analysis

Overall, the results obtained for the Resfinder and Plasmidfinder (from BugSeq/BugSplit analyses) and for the KEGG resistome evaluation can be found in Table 4, while the MEGARes results are presented in Figure 3 and in Supplementary File S2. Additionally, detailed individual metagenomic bins regarding AMR profiles of each sample can be verified in Supplementary Table S4. In general, only samples C2, R1, and R2 were able to provide results for this analysis due to the absence of reliable hits after blast analysis.

Table 4.

Overall resistome analysis results.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of the MEGARes resistome genes identified.

The BugSeq/BugSplit (Resfinder) analysis predicted the presence of the Bla, blaOXA (sample C2) and the blaTEM-116 (sample R1) genotypic markers for antimicrobial resistance. Solely in sample R1, the presence of plasmids AB951 and AK937 containing the blaTEM-116 gene were detected. Members of the microbiome-carrying resistome genes included Bacteria sp. in sample R1 and Cyanophyceae sp., Nostocales sp., and Streptomyces sp. in sample C2 (Supplementary Table S4). The KEGG analysis revealed that all samples contained gene contents associated with beta-Lactam resistance, Vancomycin resistance, and Cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) pathways. Additional antimicrobial KEGG signatures such as beta-Lactamase class A TEM resistance and beta-Lactam and Bla system resistance were also found in sample R1 and R2, respectively (Table 4).

When considering the NI areas, for sample C2, the MEGARes annotation highlighted a high representation of the types: drugs (40%), metals (27%), and biocides (21%). Subtypes were dominated by multi drug resistance (13%), multi biocide resistance (11%), and copper resistance (10%). At the AMR gene level, the sample was dominated by multi drug ABC efflux pumps (11%), copper resistance proteins (9%), and drug and biocide RND efflux pumps (8%) (Supplementary File S2). In sample R1, MEGARes annotated high levels of the types: metals (50%), drugs (33%), and biocides (17%). Subtypes were dominated by copper resistance (42%) and beta-Lactams (25%), while at the AMR gene level, the sample was dominated by copper resistance proteins (42%) and class A beta-lactamases (25%) (Supplementary File S2). In parallel, for sample R2, MEGARes annotated significant levels of the types: drugs (35%), metals (35%), and biocides (17%). Subtypes were dominated by aminocoumarins (17%) and beta-Lactams (13%) while at the AMR gene level, the sample was dominated by aminocoumarin efflux pump (17%), multi-biocide ABC efflux pump, drug and biocide RND efflux pumps and copper resistance protein (all with 9%) (Supplementary File S2).

Further details of unique and shared AMR genes can be verified in Figure 3. These results revealed a pronounced shift on the resistome profiles: 39 genes detected in NI were absent from RI, indicating a substantial loss of AMR diversity following recolonization. Conversely, 15 genes were exclusively found in RI, suggesting selective persistence or emergence of specific resistance traits. Moreover, 8 were shared by both cases, potentially representing stable and more core AMR resistance genes. Further statistical evaluation of the AMR genes detected, obtained through ANOVA calculations, revealed that the associated p-value was 1.1 × 10−16, confirming statistically significant differences between NI and RI areas.

3.3. Metabolic Analysis

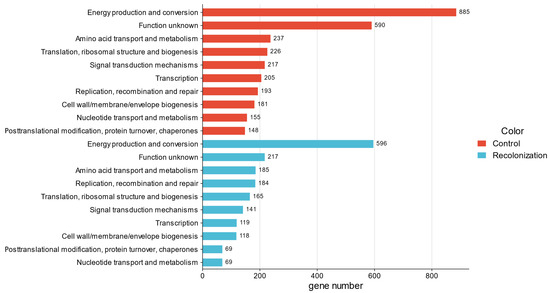

3.3.1. Clusters of Orthologous Gene Categories Analysis

Figure 4 displays the Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs) count means, identified in both cases studied. Excluding the “function unknown” category, the three most prominent COGs were energy production and conversion, amino acid transport and metabolism, and translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis. Moreover, except for energy production and conversion, low differences in the mean numbers associated with matching COGs for NI and RI were present.

Figure 4.

Mean counts of the top 10 COGs identified.

3.3.2. KEGG Pathway Mapping Analysis

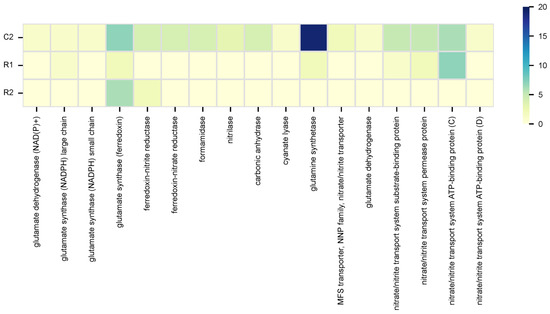

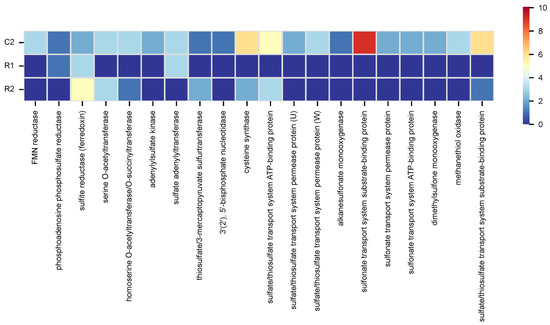

KEGG pathway mapping revealed various microbial metabolic traits potentially linked to stone biodeterioration. Specifically, microbial nitrogen and sulfur cycling, although part of natural biogeochemical processes, when intensified by pollution and moisture, promote or accelerate stone deterioration [5]. In general, the KEGG gene mapping connected to these processes solely provided results for samples C2, R1, and R2 due to the lack of significant hits for the remaining samples. The data obtained highlighted that, for sample C2, the overall microbiome can conduct nitrate and sulfate–sulfur assimilation (Signature modules). Additionally, data presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6 depict specific gene contents associated with the KEGG nitrogen and sulfur metabolic pathways.

Figure 5.

Gene counts mapped to the nitrogen metabolic pathway in KEGG.

Figure 6.

Gene counts mapped to the sulfur metabolic pathway in KEGG.

In the nitrogen cycle, for sample C2, most mapped genes were connected to nitrate assimilation, while for sample R1 and R2, most mapped genes were connected to both assimilatory nitrate reduction (nitrate => ammonia) and nitrate assimilation. In the sulfur cycle, for sample C2, many mapped genes were connected to assimilatory sulfate reduction (sulfate => H2S) and sulfate–sulfur assimilation; for sample R1, were assimilatory and dissimilatory sulfate reduction (sulfate => H2S); while for sample R2 were sulfate–sulfur assimilation and assimilatory sulfate reduction (sulfate => H2S). Overall, main genes detected were glnA (glutamine synthetase) and ssuA (sulfonate transport system substrate-binding protein) for sample C2; nrtC (nitrate/nitrite transport system ATP-binding protein) and cysH (phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate reductase) for sample R1; and glt (glutamate synthase (ferredoxin)) and sir (sulfite reductase (ferredoxin)) for sample R2 (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Statistical evaluation of the nitrogen and sulfur gene contents, obtained through ANOVA calculations, revealed significant differences between NI and RI (nitrogen: p = 0.00397; sulfur: p = 3.18 × 10−5), confirming alterations in microbial metabolism.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to characterize and compare the microbial taxonomic, resistome, and metabolic traits of untreated and treated (recolonized) stone statues at the Coimbra’s “Largo da Porta Férrea” area, while also evaluating the previously applied cleaning treatment efficiency, using on-site direct WGS Oxford Nanopore® MinION™ sequencing. The data obtained in this work allowed us to effectively assess treatment effectiveness and recolonization dynamics. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first successful report of a rapid, field-deployable recolonization diagnostic method, expanding the toolset available to microbiologists, conservators, and restorers working to improve preservation practices and decision-making policies for stone monuments and relics.

While the workflow proved to be effective, some limitations were also identified during this study. Due to the polluted nature of the stone surfaces, DNA extraction and sequencing procedures occasionally resulted in low contig N50 values and in fragmented assemblies. Although a previous work from our group [31] did not encounter these challenges, the data recovered here further underscores the need for careful, informed sampling strategies and DNA extraction and library preparation protocols, particularly in urban or heavily polluted contexts. Future applications of this workflow will benefit from optimized protocols and complementary bioinformatic analysis, to ensure robust and interpretable results across diverse environmental and anthropogenic conditions. Moreover, recognizing the potential value of linking functional traits to specific taxonomic groups, future studies should consider additional biogeochemical pathway mappers, enabling more direct connections between microbial diversity and metabolic potential, beyond the function-centric mapping approach provided by GhostKOALA in this work.

On the other hand, when compared with recent Oxford Nanopore® WGS studies that evaluated microbiome and AMR signatures following intervention [27,29], our work similarly detected treatment-associated alterations, while also allowing us to understand intra-site NI vs. RI recolonization successional pathways. By integrating on-site WGS sequencing with colorimetric measurement, this study allowed the exploration of the links between microbial taxonomical compositional, resistome, and functional shifts, with visible surface alterations and treatment impacts during early microbial recolonization events. This thorough approach provides practical contributions to the knowledge on how microbial communities recolonize stone surfaces, while also expanding the use of field-deployable metagenomics in heritage conservation.

4.1. Colorimetric Analysis

Differences in SABs colors can provide a statistically robust, quick, easy, and non-destructive way to evaluate and quantify biofilms directly on stone [48,49]. Focusing on the colorimetric analysis conducted, the RI samples showed a darker coloration (significant L*/luminosity decrease), coupled with visible surface alterations, as highlighted by the high ΔE values verified [48,49]. Interestingly, ΔE values found for the RI areas were nearly identical to some of the control samples, suggesting that recolonization after intervention is progressing towards prominent microbial growth and dense biofilm formation [48], which may also shift towards the pigmentation characteristics of the original biofilms (dark and reddish tones). Moreover, the similarity in ΔE values between RI and NI samples together with the lack of significant statistical differences further supports that recolonization may be progressing towards a surface state similar to non-intervened areas.

In parallel, analysis of a* and b* values have been shown to be useful indicators of recolonization, varying according to the color of the rocky substrate [50,51]. Both R1 and R2 samples showed lower red colorations and a shift towards yellow tones (b* values), when compared to the controls. Sanmartín and colleagues [52] previously verified that an increase in b* values can be correlated with the accumulation of photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a, carotenoids, and phycocyanin) produced during cyanobacteria development on stone monuments. Thus, this pattern is also in accordance with the results found in our microbiome analysis, linking surface appearance and pigmentation changes to microbial recolonization dynamics.

4.2. Microbiome Diversity Metrics and Taxonomic Composition

Biofilms on stone monuments are formed through an ecological succession where pioneer photoautotrophic microorganisms can establish a foundational layer able to support the development of later colonizers, including chemolithoautotrophs and heterotrophs, such as archaea, bacteria, and fungi, all influenced by environmental factors [5]. Recolonization events after intervention mirror this natural succession process, driven by either surviving or closely located microorganisms and depending on the intervention nature and the surrounding environmental characteristics [16,17,25].

The diversity metrics pointed that, despite treatment application, microbiome richness and diversity recovered towards levels similarly verified for the NI areas. The lack of significant statistical differences reinforces this hypothesis, suggesting that the interventions conducted provided only limited protection. Mechanical removal and physical eradication methods are part of common restoration practices but often result in the incomplete removal of microorganisms (since they can affect the epilithic communities but maintain the endolithic ones undisturbed), allowing recolonization events that can be accelerated by the action of environmental factors such as rainfall [16,53,54]. Considering that in these areas, the development of darkened biofilms is enhanced by rainwater runoff from adjacent buildings and by environmental pollution, our results also suggest that recolonization can have originated from either nearby untreated areas, or from viable endolithic communities that survived after the cleaning interventions took place [16,17]. These findings further emphasize the cleaning intervention limited efficiency and provide evidence of quick recovery by recolonizing microorganisms in these areas.

Comparisons of the microbiome taxonomic composition between the areas NI and RI highlighted some peculiar differences in their relative abundances. Bacteria were dominant in both contexts with higher relative abundance values in RI, while Eukaryotic communities were less abundant in these areas, suggesting a taxonomically simpler microbiome (i.e., from an ecological succession point of view [5]). Thus, the applied treatment contributed to a marked decline in Fungi and Chlorophyta communities. In contrast, the NI samples exhibited a more balanced taxa distribution, including higher abundances of eukaryotes such as Endocarpon pusillum, absent in RI (see Figure 1). According to the literature, this absence can also highlight the limited efficacy of the intervention, since physical and mechanical cleaning have been shown to strongly impact lichen communities, but to ineffectively provide long term solutions. For instance, Sohrabi and colleagues [54] conducted lichen removal (mainly Calogaya biatorina) in the Cyrus Mausoleum (Pasargadae archeological site, Iran). This approach allowed for endolithic remains to persist in the limestone interior, which resulted in strong recolonization four years later, due to the action of rainfall, proximity to agricultural surroundings, and tourism [54]. Considering this information and the strong impact that fungi, algae, and lichens can have in recolonization events [17] and biodeterioration processes, an eventual future recolonization by Endocarpon pusillum (but also other Eukaryotic species) can possibly occur at these sites and deserves to be the focus of close monitoring and permanent evaluation campaigns.

On the other hand, photosynthetic cyanobacteria, such as Nostoc, as well as Bacteria from the genera Sphingomonas and Hymenobacter, were favored following the intervention. The presence of similar microorganisms between NI and RI (e.g., Craurococcus roseus and Hassalia byssoidea), alongside differences in their relative abundances, further suggests that the SABs of the RI areas are still developing, reflecting an early colonization state prompted by endolithic or nearby photosynthetic microorganisms [2,3,5,16,17].

While various biodeteriorative microorganisms are present in the NI samples, the rise of cyanobacteria in RI areas points towards the initial steps of recolonization by photoautotrophs, with a particular emphasis on species with tolerance for extreme conditions and able to contribute to stone biodeterioration [25]. Filamentous cyanobacteria such as Nostoc (along other cyanobacteria, including Dulcicalothrix desertica, Microcoleus asticus, and Aliterella atlantica), can act as primary colonizers, influencing stone aesthetic, physical, and chemical characteristics [25,55,56]. Complementarily, Sphingomonas and Hymenobacter can grow in low-nutrient ecosystems, survive in high UV-exposed environments and contribute to stone biodeterioration via pigment production (Sphingomonas) or extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) formation (Hymenobacter) [1,57,58,59,60,61].

Overall, the microbiome analysis highlighted that biofilms quickly recovered after the intervention, while also clarifying the role of resistant pioneer microorganisms in recolonization in these areas. As such, these results provide both methodological and conservational insights that can serve as guidance for the development and application of improved strategies in these areas of the Coimbra’s UNESCO World Heritage site.

4.3. AMR Diversity and Composition

Stone monuments have been identified as natural reservoirs of AMRs, influenced by environmental conditions and human activities such as pollution, tourism, and biocidal treatments [27,29,45,62,63]. These AMRs can help stone-dwelling microorganisms to cope with cleaning interventions, contributing to recolonization and biodeterioration, emphasizing the importance of monitoring AMR dynamics in stone conservation [27,29].

When considering the resistome profiles, several traits were common to all areas (genes associated with beta-Lactam, Vancomycin, and CAMP resistance). However, a noticeable AMR profile shift between the NI and RI zones was also observed. While Bla and blaOXA genotypic markers were detected in NI, plasmids containing blaTEM-116 genes were exclusively detected in RI, which also exhibited unique KEGG signatures connected to beta-lactamase class A TEM and the beta-Lactam (Bla system) resistance systems.

These results suggest a capacity for microbial resistome adaptability in RI, likely driven by plasmid-mediated gene transfer mechanisms and from the selective pressures imposed by the applied treatment (which may contribute to promote resistance and recolonization) [43]. Such adaptability aligns with previous investigations concerning stone monuments resistomes, which have elucidated that stone-dwelling microorganisms can acquire AMR genes through horizontal transfer, particularly in anthropogenically altered environments [44,62,63]. At the “Largo da Porta Férrea”, local factors such as verified water runoff, pollution, vegetation growth, and recurrent graffiti and poster affixation (these last are especially noticeable in R1) may, in fact, further contribute to horizontal gene transfer and cross-niches dispersal, helping shape the resistome structure at this site [44,62,63].

In parallel, shifts in resistome profiles are also known to arise following the application of microbiome-targeted control interventions [27,29]. The MEGAREs analysis highlighted that the RI areas displayed a notable increase in metal resistance (copper and nickel), alongside an enhanced presence of drug resistance genes. Additionally, considering statistical differences in AMR gene contents between NI and RI, these findings point that the cleaning intervention altered the baseline resistome of the microbial communities, promoting differential (15 new genes) and more diversified resistance mechanisms (such as plasmid-mediated). Such shift can hypothetically foster the development of more resilient microbial populations and facilitate ecological succession in intervened areas [6,16].

Overall, these findings expand the previous knowledge gathered about stone resistomes, by elucidating that cleaning interventions can trigger shifts in AMR profiles (including plasmid-associated) rapidly, while also connecting resistome adaptability to microbial recolonization and treatment efficiency.

4.4. COG Functional Analysis

Previous COG functional analysis of stone biofilm metagenomes revealed that microbial communities mainly prioritize carbohydrate transport and metabolism; energy production and conversion; amino acid transport and metabolism; and translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis [31,64]. These functional profiles are essential to support adaptations to nutrient availability and to cope with harsh environmental conditions [31].

Accordingly, the results obtained in this study align with the available literature, highlighting common functional requirements for survival in extreme stony habitats [64]. Moreover, solely minimal differences could be noted between NI and RI areas (except for energy production and conversion), pointing that the recolonizing microbiome retains many of the core metabolic functions necessary for survival and maintenance (Figure 4).

Overall, these parallels reinforce the idea that stone-associated microbial communities share multiple conserved metabolic blueprints shaped by adaptions to the challenging environmental conditions typically found on lithic environments.

4.5. Metabolic Pathways

Microbial nitrogen and sulfur cycling, intensified by pollution and moisture, play a key role in accelerating stone monument biodeterioration [5]. Nitrification processes produce nitric acids able to dissolve minerals, while denitrification processes contribute to the formation of damaging salts [5]. Similarly, sulfur oxidation generates sulfuric acid, forming gypsum crusts, while sulfate reduction promotes corrosion [5].

NI areas showed a versatile and more complex nitrogen and sulfur metabolism, with potential for nitrate (glnA, glu, gltB/D, nirA, narB, and nrtA-D) and sulfate-sulfur assimilation (sir, cysK, cysA/U/W, ssuA-C, sfnG, and selenbp1) processes. These pathways can contribute to stone biodeterioration through microbial sulfate reduction into sulfide, which generates hydrogen sulfide (H2S). In the presence of oxygen or even some metal ions, H2S can be oxidized to sulfuric acid (H2SO4), a strong acid known to promote mineral dissolution [5,65,66]. In parallel, nitrate assimilation can increase carbonate alkalinity, potentially favoring CaCO3 biomineralization as part of microbial carbonate stone dissolution/biomineralization processes [65]. In contrast, RI samples exhibited reduced or limited nitrogen and sulfur cycling capabilities, displaying mainly basic nitrogen assimilation, nitrate/nitrite transport, and sulfate reduction pathways gene contents. Gene counts were also notably higher in NI than in RI (69 vs. 23 for nitrogen and 60 vs. 24 for sulfur), with both pathways exhibiting statistically significant differences.

Overall, these differences align with the enhanced proliferation of cyanobacteria in the RI samples. As early photoautotrophic colonizers, they drive initial biofilm development through the production of organic matter that can be used for subsequent colonization by heterotrophic microorganisms [2,3,55,57,65], but have limited nitrogen and sulfur metabolic diversity [5,57]. Later colonizers, including chemolithotrophs and heterotrophs, expand SABs metabolic functions, playing important roles in nitrate assimilation, sulfate reduction, and oxidation (as verified in NI) [3,5,66]. Thus, the complex nitrogen and sulfur processes detected in the NI are consistent with a more mature stage of biofilm formation, whereas in RI, the simplified metabolic profiles associated with biogeochemical reactions points towards the earlier stages of SAB development following intervention. Moreover, these results also suggest that RI potentially exhibits a lower biogeochemical biodeterioration potential (due to lower gene contents), where alterations may occur mainly by pore penetration [67] or aesthetically due to pigmented photoautotrophic colonization.

5. Conclusions

This work aimed to evaluate the utility of on-site colorimetric and molecular analysis to understand recolonization events on stone monuments. The study conducted on the non-intervened vs. recently intervened areas at the Coimbra’s “Largo da Porta Férrea” highlighted that the treatments applied were only able to offer a short-term solution, with microbial recolonization and noticeable biofilm growth already occurring. Although no statistical differences were found, the microbial communities were distinct between NI and RI areas, with the treatment resulting in a decline in Fungi and Chlorophyta. Additionally, Cyanobacteriota mainly dominated the RI zones, as typically found in early stages of SABs recolonization. Resistome analysis revealed that the baseline AMR gene profiles were altered. Additionally, after intervention, the emergence of plasmid-mediated gene transfer mechanisms and an enhanced presence of metal and drug resistances were noted. The biogeochemical processes that can impact stone monuments were also changed by the intervention. In NI areas, microbial communities exhibit broader metabolic capacities, including those connected to nitrogen and sulfur cycling, that pose a greater risk to stone substrates through biodeterioration processes. In contrast, RI areas show a reduced number of metabolic functions, being dominated by photoautotrophic microorganisms. The enhanced photoautotroph colonization is consistent with earlier stages of SAB development, which can, in the future, sustain the development of heterotrophs. Such advancement can lead to the gradual re-establishment of more complex elemental cycles, with direct impact on these stone monuments’ biodeterioration. Considering this scenario, periodic monitoring of biofilm development, ideally every six months, could strongly contribute to long-term stability and conservation of these stone monuments. Such monitoring could encompass the evaluation of microbial taxonomic diversity, resistome dynamics, and changes in functional gene profiles across time. This approach would enable timely adjustments for new informed interventions to be taken, while also allowing the development of targeted and sustainable intervention approaches. While the specific intervention protocol conducted in these areas remains undisclosed, additional comparative studies considering sites with documented cleaning strategies could also further help refine conservation practices. Lastly, this study also highlights the usefulness of the application of the Oxford Nanopore® MinION™ sequencer for on-site direct WGS aimed at evaluating common preservation actions on invaluable stone monuments and relics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152111843/s1, Table S1: Overall Nanoplot and Quast metrics obtained for each sample. Table S2: Sample alpha diversity indexes. Table S3: Overall BugSeq/BugSplit general statistics. Table S4: Detailed AMR genotypes by metagenomic bin detected in each sample. File S1: Overall taxonomic diversity relative abundance found for each sample. File S2: Overall AMR gene contents relative abundance found for each sample.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, F.S. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, F.S., L.C., C.E. and J.T.; methodology, F.S., L.C., C.E. and J.T., investigation, F.S., L.C., C.E. and J.T.; funding acquisition, F.S., L.C., C.E. and J.T.; supervision, J.T.; project administration, J.T.; conceptualization, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Santander/University of Coimbra in the framework of the SeedProjects@UC 2024 (Strategic Area Heritage, Culture and Inclusive Society) project “DiMER: in situ molecular and analytical analyses of stone monuments biodeteriorative microorganisms DIversity, MEtabolism and Resistome features to improve conservation strategies”, with the reference PT0054.A.01.C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in NCBI, reference numbers PRJNA1272556 (Bioproject), SAMN48915728-SAMN48915732 (Biosample), and SRR33846319-SRR33846323 (SRA).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for all the project assistance of António Manuel Santos Carriço Portugal and Maria Manuela Galhardo de Matos Vieira. João Trovão would like to thank the Centre for Functional Ecology (CFE), Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, for providing access to facilities and support during data collection. The analysis, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript were carried out at MUM—Micoteca da Universidade do Minho, CEB—Centre of Biological Engineering, University of Minho.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gorbushina, A.A. Life on the rocks. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1613–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerer, S.; Ortega-Morales, O.; Gaylarde, C. Chapter 5 Microbial Deterioration of Stone Monuments—An Updated Overview. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Laskin, A.I., Sariaslani, S., Gadd, G.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; Volume 66, pp. 97–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakal, T.C.; Cameotra, S.S. Microbially induced deterioration of architectural heritages: Routes and mechanisms involved. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2012, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, F.; Cappitelli, F. The Ecology of Subaerial Biofilms in Dry and Inhospitable Terrestrial Environments. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Koestler, R.J.; Warscheid, T.; Katayama, Y.; Gu, J.-D. Microbial deterioration and sustainable conservation of stone monuments and buildings. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, D. Coping with Biological Growth on Stone Heritage Objects: Methods, Products, Applications, and Perspectives; Apple Academic Press: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2017; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Cappitelli, F.; Cattò, C.; Villa, F. The Control of Cultural Heritage Microbial Deterioration. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolini, M.; Nugari, M.P. Resistance to Biodeterioration of Some Products Used for Rising Damp Barrier. In Protection and Conservation of the Cultural Heritage of the Mediterranean Cities; Zezza, G.A., Ed.; Swets & Zeitlinger: Lisse, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Caneva, G.; Nugari, M.P.; Salvadori, O. Plant Biology for Cultural Heritage: Biodeterioration and Conservation; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; 5N81-606-CB10. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, A.; Pinna, D. Prevention of Biodeterioration. Outdoor Environments. In Plant Biology for Cultural Heritage: Biodeterioration and Conservation; Caneva, G., Nugari, M.P., Salvadori, O., Eds.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 197–198. [Google Scholar]

- de Los Ríos, A.; Cámara, B.; García Del Cura, M.A.A.; Rico, V.J.; Galván, V.; Ascaso, C. Deteriorating effects of lichen and microbial colonization of carbonate building rocks in the Romanesque churches of Segovia, Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehne, E.; Price, C.A. Stone Conservation: An Overview of Current Research, 2nd ed.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, D. Can we do without biocides to cope with biofilms and lichens on stone heritage? Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2022, 172, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanza, M.R.; Caneva, G. Natural biocides for the conservation of stone cultural heritage: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 38, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolino, B.; Sorrentino, M.C.; Pacifico, S. Greener solutions for biodeterioration of organic-media cultural heritage: Where are we? Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, D. Microbial recolonization of artificial and natural stone artworks after cleaning and coating treatments. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 61, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, B.; Paz-Bermúdez, G.; López De Silanes, M.E.; Montojo, C.; Pérez-Velón, D. Current knowledge regarding biological recolonization of stone cultural heritage after cleaning treatments. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beata, G. The use of -omics tools for assessing biodeterioration of cultural heritage: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 45, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterflinger, K.; Piñar, G. Molecular-Based Techniques for the Study of Microbial Communities in Artworks. In Microorganisms in the Deterioration and Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Joseph, E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñar, G.; Sterflinger, K. Natural sciences at the service of art and cultural heritage: An interdisciplinary area in development and important challenges. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, J.; Cavalieri, D.; Mastromei, G.; Pangallo, D.; Perito, B.; Marvasi, M. MinION technology for microbiome sequencing applications for the conservation of cultural heritage. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 247, 126727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jroundi, F.; Elert, K.; Ruiz-Agudo, E.; Gonzalez-Muñoz, M.T.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C. Bacterial Diversity Evolution in Maya Plaster and Stone Following a Bio-Conservation Treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 599144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elert, K.; Ruiz-Agudo, E.; Jroundi, F.; Gonzalez-Muñoz, M.T.; Fash, B.W.; Fash, W.L.; Valentin, N.; de Tagle, A.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C. Degradation of ancient Maya carved tuff stone at Copan and its bacterial bioconservation. npj Mater. Degrad. 2021, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-de Pablo, M.; Ascaso, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, E.; Urizal, M.; Wierzchos, J.; Pérez-Ortega, S.; de los Ríos, A. Innovative approaches to accurately assess the effectiveness of biocide-based treatments to fight biodeterioration of Cultural Heritage monuments. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.; Gu, J.-D.; He, K.; Fang, Z.; Liu, X.; He, D.; Ding, X.; Li, J.; Han, Z.; et al. Dominance by cyanobacteria in the newly formed biofilms on stone monuments under a protective shade at the Beishiku Temple in China. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratter, M.; Beccaccioli, M.; Vassallo, Y.; Benedetti, F.; La Penna, G.; Proietti, A.; Zanellato, G.; Faino, L.; Cirigliano, A.; Neisje De Kruif, F.; et al. Long-term monitoring of the hypogeal Etruscan Tomba degli Scudi, Tarquinia, Italy. Early detection of black spots, investigation of fungal community and evaluation of their biodeterioration potential. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A.; Maisto, F.; Pavlović, J.; Rusková, M.; Pangallo, D.; Sanmartín, P. Microbiome shifts elicited by ornamental lighting of granite facades identified by MinION sequencing. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2024, 261, 113065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichy, J.; Sipek, B.; Ortbauer, M.; Fürnwein, L.; Waldherr, M.; Graf, A.; Sterflinger, K.; Piñar, G. Microbial community shifts during salt mitigation treatments of historic buildings using mineral poultices: A long-term monitoring of salt and associated biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1603289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisto, F.; Méndez, A.; Pavlović, J.; Kraková, L.; Sanmartín, P.; Pangallo, D. Microbiome and Response to Cleaning and Biocidal Treatments on Granite Historical Buildings Using MinION Sequencing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovão, J.; Soares, F. Future Perspectives on the Application of the Oxford Nanopore® MinIONTM Sequencer in Cultural Heritage Biodeterioration Studies. Preprints 2024, 2024061478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, F.; Catarino, L.; Egas, C.; Trovão, J. On-site Oxford Nanopore® MinION™ whole genome sequencing analysis to understand the microbiome, resistome and metabolic features of subaerial biofilms on stone monuments. Total Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, V.; Afgan, E.; Gu, Q.; Clements, D.; Blankenberg, D.; Goecks, J.; Taylor, J.; Nekrutenko, A. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2020 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W395–W402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coster, W.; D’Hert, S.; Schultz, D.T.; Cruts, M.; Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: Visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2666–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Huang, S.; Chorlton, S.D. BugSeq: A highly accurate cloud platform for long-read metagenomic analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrakumar, I.; Gauthier, N.P.G.; Nelson, C.; Bonsall, M.B.; Locher, K.; Charles, M.; MacDonald, C.; Krajden, M.; Manges, A.R.; Chorlton, S.D. BugSplit enables genome-resolved metagenomics through highly accurate taxonomic binning of metagenomic assemblies. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Salzberg, S.L. Pavian: Interactive analysis of metagenomics data for microbiome studies and pathogen identification. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabdoub, S. kraken-Biom. GitHub Repository 2016, GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/smdabdoub/kraken-biom (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Midoux, C.; Rué, O.; Chapleur, O.; Bize, A.; Loux, V.; Mariadassou, M. Easy16S: A user-friendly Shiny web-service for exploration and visualization of microbiome data. J. Open Source Softw. 2024, 9, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifa, É.; Theil, S. ExploreMetabar: A user-friendly Shiny application to explore the drivers of microbial communities. In Proceedings of the Club des bactéries lactiques (CBL 2022), Nantes, France, 8–10 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonin, N.; Doster, E.; Worley, H.; Pinnell, L.J.; Bravo, J.E.; Ferm, P.; Marini, S.; Prosperi, M.; Noyes, N.; Morley, P.S.; et al. MEGARes and AMR++, v3.0: An updated comprehensive database of antimicrobial resistance determinants and an improved software pipeline for classification using high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D744–D752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Zhang, N.; Shen, X.; Muhammad, A.; Shao, Y. Deciphering environmental resistome and mobilome risks on the stone monument: A reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, B.; Silva, B.; Lantes, O. Biofilm quantification on stone surfaces: Comparison of various methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 333, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, B.; Vázquez-Nion, D.; Fuentes, E.; Durán-Román, A.G. Response of subaerial biofilms growing on stone-built cultural heritage to changing water regime and CO2 conditions. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2020, 148, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, P.; Vázquez-Nion, D.; Silva, B.; Prieto, B. Spectrophotometric color measurement for early detection and monitoring of greening on granite buildings. Biofouling 2012, 28, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanmartín, P.; Rodríguez, A.; Aguiar, U. Medium-term field evaluation of several widely used cleaning-restoration techniques applied to algal biofilm formed on a granite-built historical monument. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2020, 147, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartin, P.; Aira, N.; Devesa-Rey, R.; Silva, B.; Prieto, B. Relationship between color and pigment production in two stone biofilm-forming cyanobacteria (Nostoc sp. PCC 9104 and Nostoc sp. PCC 9025). Biofouling 2010, 26, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado, V.; Miller, A.Z.; Cuezva, S.; Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Benavente, D.; Rogerio-Candelera, M.A.; Reyes, J.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Recolonization of mortars by endolithic organisms on the walls of San Roque church in Campeche (Mexico): A case of tertiary bioreceptivity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 53, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, M.; Favero-Longo, S.E.; Pérez-Ortega, S.; Ascaso, C.; Haghighat, Z.; Talebian, M.H.; Fadaei, H.; de los Ríos, A. Lichen colonization and associated deterioration processes in Pasargadae, UNESCO world heritage site, Iran. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2017, 117, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, M.F.; Miller, A.Z.; Dionísio, A.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Biodiversity of cyanobacteria and green algae on monuments in the Mediterranean Basin: An overview. Microbiology 2009, 155, 3476–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Baptista-Neto, J.A. Microbiologically induced aesthetic and structural changes to dimension stone. npj Mater. Degrad. 2021, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warscheid, T.; Braams, J. Biodeterioration of stone: A review. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2000, 46, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, F.; Iero, A.; Zammit, G.; Urzi, C. Chemoorganotrophic bacteria isolated from biodeteriorated surfaces in cave and catacombs. Int. J. Speleol. 2012, 41, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; He, Z.; Yang, X. Distribution and Diversity of Bacteria and Fungi Colonization in Stone Monuments Analyzed by High-Throughput Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovski, A.; Gabarre, A.; Seyer, D.; Bousta, F.; Di Martino, P. Bacterial diversity on rock surface of the ruined part of a French historic monument: The Chaalis abbey. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2017, 120, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.C.; Madureira, A.R.; Pintado, M.; Moreira, P.R. Biocontamination and diversity of epilithic bacteria and fungi colonising outdoor stone and mortar sculptures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3811–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wu, C.; He, J.; Zhang, B. Unraveling the microbiotas and key genetic contexts identified on stone heritage using illumina and nanopore sequencing platforms. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2023, 185, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Lan, W.; Li, J.; Deng, M.; Li, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Gu, J.-D. Metagenomic insight into the pathogenic-related characteristics and resistome profiles within microbiome residing on the Angkor sandstone monuments in Cambodia. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.-D.; Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Li, J.; Feng, H. Metagenomic and metaproteomic insights into the microbiome and the key geobiochemical potentials on the sandstone of rock-hewn Beishiku Temple in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 893, 164616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindschedler, S.; Cailleau, G.; Verrecchia, E. Role of Fungi in the Biomineralization of Calcite. Minerals 2016, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Lan, W.; Yan, A.; Li, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Gu, J.-D. Microbiome Characteristics and the Key Biochemical Reactions Identified on Stone World Cultural Heritage under Different Climate Conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, C.A.; Gaylarde, C.C. Cyanobacteria and Biodeterioration of Cultural Heritage: A Review. Microb. Ecol. 2005, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).