Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze the transfer performance of a spacecraft equipped with a TANDEM electric propulsion system in a classical interplanetary mission scenario targeting Mars, Venus, or a near-Earth asteroid. The TANDEM concept is a coaxial, two-channel Hall-effect thruster recently proposed under ESA’s Technology Development Element program. This innovative propulsion system, currently undergoing experimental characterization, is designed to operate at power levels between and , delivering a maximum thrust of approximately . Its architecture allows operation using a single channel (internal or external) or both channels simultaneously to achieve maximum thrust. This inherent flexibility enables the definition of advanced control strategies for future missions employing such a propulsion system. In the context of a heliocentric mission scenario, this paper adopts a simplified thrust model based on actual thruster characteristics and a semi-analytical model for spacecraft mass breakdown. Transfer performance is evaluated within an optimization framework in terms of time of flight and the corresponding propellant mass consumption as functions of the main spacecraft design parameters.

1. Introduction

Since the successful NASA mission Deep Space 1 [1], which tested the effectiveness of the NSTAR ion engine in interplanetary space in the late 1990s [2], solar electric propulsion (SEP) has been considered a viable option for performing robotic missions aimed at exploring regions of the Solar System or visiting small celestial bodies that are difficult to reach using chemical (high-thrust) propulsion systems [3]. In this context, the SEP’s potential has been confirmed over the last decade by the JAXA missions Hayabusa and Hayabusa2 [4], which successfully returned samples from near-Earth asteroids, becoming the first missions ever to achieve this milestone [5]. More recently, the ESA/JAXA mission BepiColombo [6], launched in 2018 to reach Mercury, with its four QinetiQ-T6 ion thrusters [7], represents a typical example of how a complex interplanetary trajectory can be achieved with the aid of a SEP system composed of an array of advanced thrusters.

The potential of a newly proposed (low-thrust) electric propulsion system designed to equip a deep-space vehicle is usually assessed by analyzing, within a simplified and preliminary framework [8], its performance in an interplanetary mission scenario involving the transfer to an inner planet, such as Mars or Venus [9]. In the context of the heliocentric orbit transfer of a SEP-propelled vehicle, the preliminary trajectory is obtained by solving an appropriate optimal control problem [10], where the scalar term to be minimized is the required propellant mass, the flight time, or a suitable combination of these two key mission parameters. This typical optimization problem can be solved, in an approximate form and under some simplifying assumptions, using a semi-analytical approach such as that proposed in Ref. [11], or by employing a conventional technique based on the calculus of variations [12] (i.e., an indirect approach), or a more recent—though typically more computationally demanding—direct approach [13]. In this first phase of the mission’s study, a simplified modeling of the spacecraft’s dynamics is employed to reduce computational cost and enable the analysis of a large number of possible transfer trajectories within a short time frame.

Considering the context of preliminary trajectory design, this paper aims to investigate the performance of a spacecraft equipped with the newly proposed TANDEM Electric Propulsion System (TEPS) [14,15]. In particular, the potential of this thruster concept is assessed within a heliocentric mission scenario involving the transfer of a robotic vehicle from Earth’s orbit to that of Mars, Venus, or a near-Earth asteroid, such as the recently discovered [16] (and potentially hazardous [17]) asteroid 2024 YR4. The novel contribution of this paper is to provide the first analysis of the transfer performance of a spacecraft propelled by a TEPS within a defined (and important) set of heliocentric mission scenarios.

This work is based on two main assumptions. The first is closely related to the (typical) assumption of a two-body dynamical model for describing the heliocentric motion of the TEPS-propelled spacecraft. In this context, all orbital perturbations are neglected, and the spacecraft is assumed to be influenced only by the Sun’s gravitational attraction and the continuous thrust provided by the on-board primary propulsion system, i.e., the TANDEM. Moreover, the spacecraft state vector is assumed to be exactly known at any point along the transfer trajectory, so that possible uncertainties in this aspect (as well as in the characteristics of the thrust vector) are disregarded. Uncertainty analysis, in fact, can be considered a second-order approach to trajectory design, where the results obtained with the proposed procedure are refined using a more accurate mathematical model, which, on the other hand, requires increased computation time. The second important assumption concerns the concept of orbit-to-orbit transfer, where planetary ephemerides are not considered in the trajectory design in order to determine the global minimum flight time for a given parking and target orbit. Although this assumption may seem incompatible with the requirements of an orbital rendezvous, the results obtained in this case can be used to identify the most appropriate launch window to achieve transfer performance close to the optimal one.

The TEPS is a coaxial, two-channel Hall-effect thruster [18] recently proposed under ESA’s Technology Development Element program [19]. This innovative propulsion system, developed by the University of Pisa and Aerospazio Tecnologie s.r.l. (Siena, Italy), is currently undergoing experimental characterization in terms of classical propulsive performance, such as thrust magnitude and specific impulse, using either Xenon or Krypton as propellant [20,21]. The propulsion system is designed to operate at power levels between approximately and and can deliver a maximum thrust of with a specific impulse of about and a total efficiency of when Xenon is used as propellant and the input power is [22]. Notably, the specific design of TEPS allows this Hall-effect thruster to operate using a single channel (either internal or external) or both channels simultaneously to achieve maximum thrust for a given TEPS input power [22]. Conversely, when using Xenon (which is considered the reference propellant in the remainder of this paper), tests indicated that the minimum thrust magnitude is about , obtained with a specific impulse of and a total efficiency of when the TEPS input power is .

Considering these two extreme thrust values, as described in Ref. [22], recent laboratory measurements have characterized TEPS performance at 11 potential operating points. These include operation with the inner channel only (IC mode), the outer channel only (OC mode), or both channels simultaneously (dual channel, DC mode). For each operating point, performance data—covering thrust, electric input power, specific impulse, and propellant mass flow rate—can be used to populate a representative thrust table for this propulsion system. This table enables the modeling of key characteristics of the spacecraft’s thrust vector during the interplanetary transfer, as illustrated in Ref. [23]. In that work, NASA’s Evolutionary Xenon Thruster (NEXT) thrust table, provided by Patterson and Benson [24], was used to investigate flight performance in a robotic mission to the inner Solar System’s regions. More recently, this approach was applied in Ref. [25] to analyze the heliocentric transfer of a CubeSat propelled by a BIT-3 RF ion thruster [26] developed by Busek Co. Inc. (Natick, MA, USA) [27]. A similar methodology was employed to analyze the transfer of a spacecraft equipped with more complex multimode propulsion system, such as a monopropellant–electrospray microthruster [28], which combines the advantages of both continuous-thrust and high-thrust propulsion modes in trajectory design [29].

In this paper, Section 2 illustrates a simplified thrust model suitable for implementation in an orbital simulator to study the optimal heliocentric trajectories of a TEPS-propelled interplanetary spacecraft across a set of mission scenarios. These scenarios are described in Section 3, which also briefly outlines the approach adopted for designing the spacecraft’s transfer trajectory which gives the total flight time. This approach is primarily based on the optimization method proposed about a decade ago in Ref. [23] for a conventional spacecraft and later validated for CubeSat-based mission scenarios. Accordingly, Section 3 does not present the mathematical approach used to optimize the spacecraft’s trajectory (summarized instead in the Appendix A), in order to focus on the novelties of this work, namely the results of numerical simulations discussed in Section 4.

In that section, the TEPS-based mission performance is assessed by analyzing the characteristics of the rapid transfer trajectory as functions of the vehicle’s initial mass and the reference electric power supplied by the solar array. The orbital simulations are then used to determine the propellant mass required to complete the transfer. This value is subsequently used as input to the simplified mass breakdown model proposed by Gerberich and Oleson [30], which employs a statistical approach to estimate the mass of the spacecraft’s key subsystems as a function of payload mass. The results of the numerical simulations are presented in graphical form, enabling a quick evaluation of transfer performance and the identification of an appropriate trade-off among the spacecraft’s initial total mass, installed electric power, flight time, and payload mass for a given mission scenario. This aspect is further discussed in Section 5, which provides the final remarks of the paper.

2. Simplified Thrust Modeling of TEPS for Preliminary Trajectory Analysis

This section introduces the thrust model adopted to analyze the dynamics of an interplanetary spacecraft equipped with a TEPS. The starting point is the experimental characterization of the TANDEM system, as reported in the recent and noteworthy work by Scaranzin et al. [22], which details the performance of this innovative thruster under laboratory conditions. In particular, assuming Xenon as the propellant, Table VI.1 in Ref. [22] summarizes the experimental measurements obtained during a test campaign covering eleven operating points. A subset of the data reported in that table is employed here to model the TEPS-induced thrust vector along an assigned interplanetary orbit transfer. Note that the procedure used in this work can be easily adapted to a context where the electric thruster operates with a greater number of levels than the 11 analyzed so far in the experimental framework.

From the perspective of preliminary mission design, the propulsion system is characterized by three key parameters: the thrust magnitude T, the propellant mass flow rate , and the electric input power P. It is also necessary to allow the thruster to be switched off, enabling the spacecraft to enter a coasting phase whose trajectory is essentially a Keplerian arc under the typical assumption of a two-body (heliocentric) dynamical model. To this end, in addition to the eleven operating points reported in Table VI.1 of Ref. [22], an additional (virtual) twelfth point is introduced, characterized by zero values of T, , and P. When this (virtual) operating point is selected, it indicates that the TEPS-propelled spacecraft transitions from a propelled phase to a coasting arc along the interplanetary trajectory. Accordingly, the TEPS performance model (for the preliminary trajectory analysis) considers 12 possible operating points, which are referenced throughout the paper using the dimensionless index .

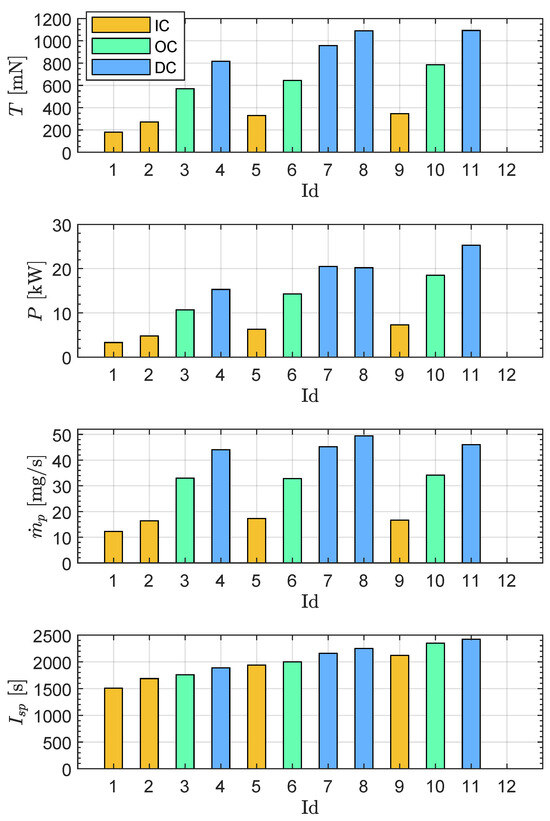

The three key parameters used for simulating the spacecraft’s orbit around the Sun, together with the specific impulse —reported here for completeness, as its value can be readily computed from the pair using standard formulas—are summarized in Table 1 as functions of the thruster’s operating point . In particular, the second column of that table specifies the TEPS operating mode, i.e., the channel employed to generate thrust (IC, OC, or DC), with corresponding to the propulsion system being switched off (no active channel). Figure 1 shows the bar plots of the thruster’s performance parameters as a function of the dimensionless term .

Table 1.

Performance characteristics of the TEPS used to model the spacecraft’s thrust vector as a function of the operating point . Data for the first eleven operating points are taken from Ref. [22]. The last row corresponds to the switched-off state.

The value of P reported in Table 1 is particularly relevant for trajectory design in a heliocentric scenario where solar arrays supply electric power. In fact, comparing P with the available electric power determines which thruster’s operating points are effectively accessible at a given solar distance r. To this end, a simple model of to operate the TEPS at a generic value of r is employed. In this simplified model, the available electric power is expressed as a function of: (1) the reference (installed) power at a solar distance of 1 astronomical unit; (2) the Sun–spacecraft distance r; and (3) the electric power allocated to other subsystems (e.g., for example, the communications system and the scientific payload), through the following equation:

Once the value of is computed at a generic point along the spacecraft’s heliocentric trajectory trough Equation (1), the operating level requiring an input power equal to P can be used only if the condition

is satisfied. On the other hand, when , the only (virtual) operating point available is , corresponding to the propulsion system being switched off and the spacecraft entering a coasting arc.

Figure 1.

Bar plots of the performance data summarized in the TEPS thrust table, used to simulate the spacecraft’s heliocentric dynamics. The three colors represent the operating modes: green → outer channel (OC), orange → inner channel (IC), and blue → dual channel (DC).

The second column in Table 1, as well as the color used to fill the bars in Figure 1, indicates the TEPS operating mode for each operating point. In this regard, three subsets of operating points can be defined: , , and , corresponding to IC, OC, and DC modes, respectively, including the off-mode identified by . The three subsets can be used, for example, to analyze the spacecraft’s transfer performance under a more constrained scenario in which the operation mode along a generic propelled arc remains fixed as one of the three options (i.e., IC, OC, or DC) throughout the entire interplanetary transfer.

Bearing in mind that Table 1 provides the thrust magnitude and propellant mass flow rate as functions of the operating point —i.e., and —which can be selected within a (discrete) interval whose limits depend on the solar distance r through the value of the available electric power , and following the approach discussed in Ref. [31], the TEPS-induced thrust vector is expressed as

where is the thrust unit vector, which will be determined (together with the operating point ) by solving a suitable optimal control problem described later in this paper, and is the duty cycle, defined according to Rayman and Williams [31] as “the fraction of time during deterministic thrust periods in which the thruster is actually active”. In this work, we assume , a value consistent with that employed to design the trajectory of Deep Space 1, where [31]. Note that the recent work by Nurre and Taheri [32] provides an interesting discussion on the impact of the mathematical model used to describe the concept of duty cycle on mission performance during the preliminary trajectory design phase.

The concept of duty cycle is also employed in the differential equation governing the temporal variation of the spacecraft mass m. Using the definition of the propellant mass flow rate, expressed as a function of in Table 1, the temporal variation of the spacecraft mass can be written as

where the term is (again) introduced to scale the nominal value of provided by the TEPS thrust table. According to Equations (3) and (4), in this simplified thrust model, the control terms are , which are used to determine the TEPS-induced thrust vector in the generic point along the spacecraft’s heliocentric trajectory. The values of the control terms are obtained by solving an optimization problem that minimizes the flight time required to complete a prescribed heliocentric orbit transfer, as described in the next section.

3. Mission Overview and Spacecraft Mass Breakdown Model

The performance of the TEPS-propelled spacecraft is evaluated during the heliocentric phase of a typical interplanetary transfer, in which the space vehicle departs from Earth’s orbit and reaches the orbit of a target celestial body, such as Venus, Mars, or the Apollo-type near-Earth asteroid 2024 YR4 [17]. In this study, both the departure and target heliocentric orbits are assumed to be Keplerian, with their orbital parameters obtained from the JPL Horizons system [33] as of 1 January 2025. More precisely, the Keplerian orbital elements of the celestial bodies involved in the analysis—namely the semimajor axis a, eccentricity e, inclination i, argument of perihelion , and right ascension of the ascending node —are reported in Table 2.

In this work, a rapid orbit-to-orbit transfer is considered, meaning that the optimal spacecraft trajectory connecting the three-dimensional heliocentric orbits (i.e., the parking and target orbits) is analyzed by minimizing the flight time without imposing ephemeris constraints. This assumption enables the determination of both the global minimum value of and the optimal geometrical configuration of the transfer. The latter can subsequently be used to identify the most favorable launch window in an actual ephemeris-constrained mission scenario. In this regard, the adopted procedure closely follows the first phase of the method presented by the author in Ref. [34], where the performance of an ideal reflective solar sail [35] was evaluated in a rendezvous scenario involving asteroid 2024 YR4. The details of the mathematical model used to compute the rapid transfer trajectory are summarized in the Appendix A.

Table 2.

Orbit’s data used in the study. Data evaluated at 1 January 2025 using JPL’s Horizons system.

Table 2.

Orbit’s data used in the study. Data evaluated at 1 January 2025 using JPL’s Horizons system.

| Cel. Body | a [AU] | e | i [deg] | [deg] | [deg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | 1 | ||||

| Venus | |||||

| Mars | |||||

| 2024 YR4 |

In this optimization procedure, once the target celestial body is selected, the minimum flight time and the corresponding propellant mass are obtained as functions of the spacecraft’s initial mass at the beginning of the transfer, and the installed reference electric power . In particular, the computed value is used as input to the simplified mass breakdown model, based on statistical data, proposed by Gerberich and Oleson [30]. In that semi-analytical model, the total (initial) spacecraft mass is assumes as the sum of the so-called dry mass and the propellant mass , viz.

The dry mass is given by the sum of the bus mass —which includes all spacecraft subsystems except the scientific payload—and the payload mass :

The bus mass , in turn, is further partitioned among the remaining subsystems using a set of suitable mass fractions. These fractions are estimated through a statistical analysis of previous space missions involving spacecraft equipped with propulsion systems of a similar class. In this regard, Ref. [30] considers seven parts of : the guidance, navigation, and control subsystem (subscript “GN&C”), the command and data handling subsystem (“C&DH”), the communications subsystem (“Comm”), the power subsystem (“Pow”), the thermal subsystem (“The”), the structure (“Str”), and the propulsion subsystem (“Pro”). Therefore, using the mass fractions reported in the first row of Table 1 in Ref. [30], the mass of each subsystem is computed as a function of as

However, the key concept behind the statistical model proposed by Gerberich and Oleson [30] is the use of an analytical expression that relates the spacecraft dry mass to its payload mass . This function, , is derived through a best-fit approximation of historical data from similar space missions collected by the COMPASS team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center. More precisely, for interplanetary missions involving spacecraft propelled by electric propulsion systems, Ref. [30] suggests a linear relationship of the form

where are best-fit coefficients obtained through a linear interpolation of historical data; see for example Equation (2) in Ref. [30].

Combining Equations (5) and (8), the payload mass can be implicitly expressed as a function of the two trajectory design parameters . The resulting relationship is given by

where the value of is an output of the optimization process which minimizes the flight time . Similarly, the bus mass —and, consequently, the masses of the other subsystems given by Equation (7)—can be expressed as a function of the two parameters as

where is given by Equation (9).

To summarize, for a given mission scenario (i.e., a specified target orbit) and a selected pair of design parameters , the optimal control problem described in the Appendix A is numerically solved to determine the minimum flight time and the propellant mass required for the specific interplanetary transfer. The computed is then used to evaluate the payload mass through Equation (9), which, in turn, is employed to compute the masses of the other subsystems using Equations (7) and (10). The results of this numerical study of the transfer performance are illustrated in the next section.

4. Simulation Results and Parametric Analysis of Mission Performance

This section presents the results of numerical simulations for the rapid transfer of a TEPS-propelled spacecraft in three interplanetary (orbit-to-orbit, ephemeris-free) mission scenarios. In particular, the orbital elements of both the parking orbit (i.e., the Earth’s orbit) and the generic target orbit (i.e., the orbit of Mars, Venus, or asteroid 2024 YR4) are reported in Table 2. In each case, the minimum flight time, the propellant mass, and subsystem masses are evaluated as functions of the pair , varying over an appropriate interval. In all simulations and mission scenarios, a fixed load electric power of was assumed, in accordance with the procedure used in Ref. [23]. The numerical results also allow the evaluation of the mass fractions , , and corresponding to the three masses . These fractions are defined as

4.1. Earth-Mars Mission

The spacecraft performance in this classical interplanetary three-dimensional transfer is computed by considering a large vehicle with an initial mass in the range . For reference, the lower bound of this interval is consistent with the launch mass of the BepiColombo spacecraft, which was about . Conversely, the upper bound of could represent a potential Mars cargo mission.

Keeping in mind the required input power summarized in Table 1, and considering the reduction of available power with increasing solar distance, a value of was selected for the simulations. This choice makes it possible to appreciate the impact of available electric power on transfer performance, even when is insufficient to operate all thrust levels indicated in Table 1. In fact, recalling that and using Equation (1), at a solar distance equal to the semimajor axis of Mars’ orbit (i.e., about ), when the available power is slightly above . This value, for example, is substantially sufficient to activate only the IC mode; see Figure 1.

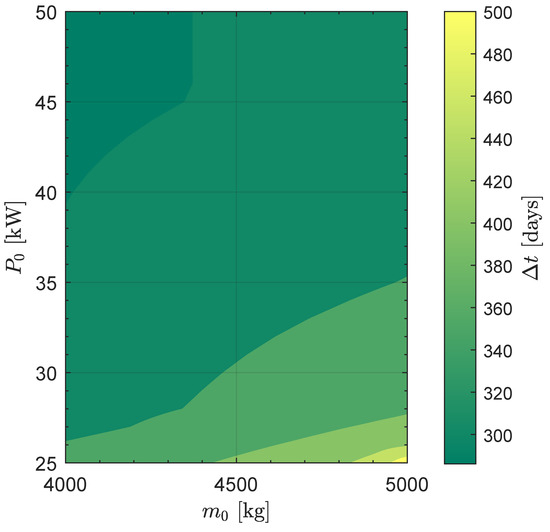

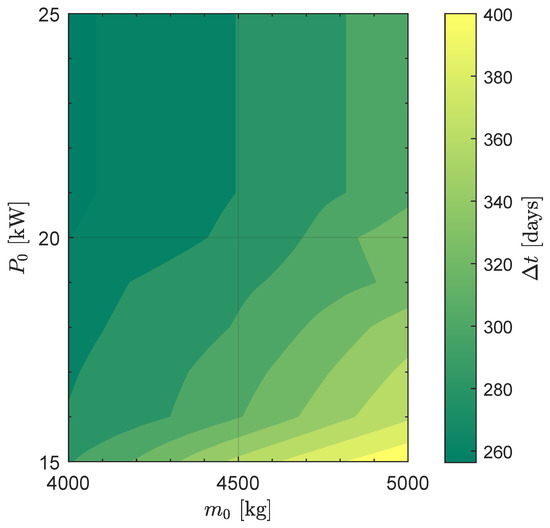

The performance analysis was carried out parametrically by varying (or ) in steps of (or ). Accordingly, 500 optimization processes were solved to obtain the contour plot shown in Figure 2, which illustrates the variation of the minimum flight time as a function of the two design parameters and .

Figure 2.

Minimum flight time for an Earth–Mars orbit-to-orbit transfer as a function of and .

Figure 2 shows that a TEPS-propelled spacecraft with a launch mass of about (i.e., similar to BepiColombo) can potentially complete the interplanetary transfer in approximately if . For the same launch mass, increasing to (or ) reduces the flight time to (or ). Similar trends are observed in the figure for launch masses up to .

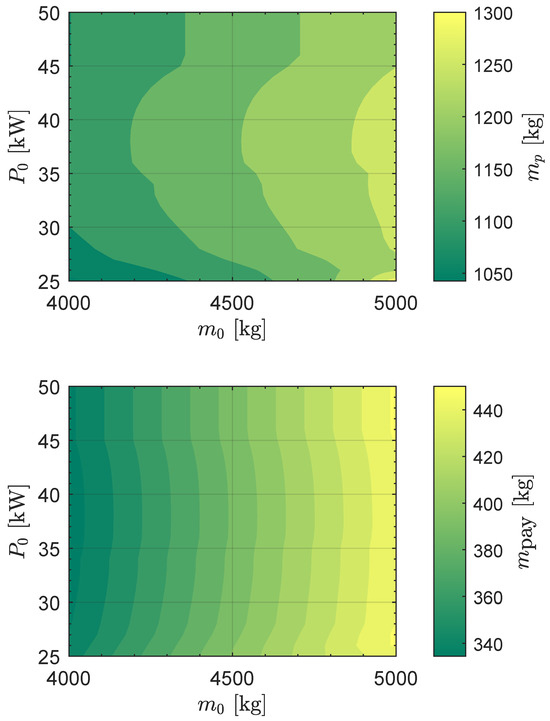

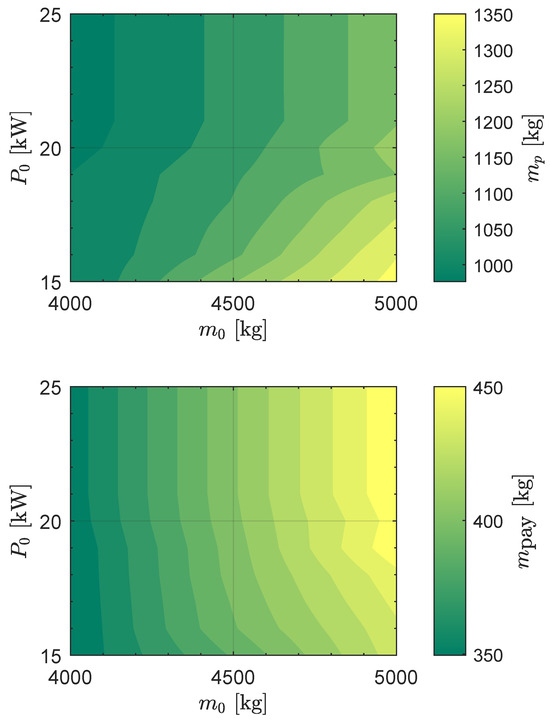

The corresponding propellant mass , which is an output of the optimization process, together with the payload mass obtained using Equation (9), is reported in Figure 3. Note that refers to a transfer where the performance index to be optimized is the flight time . For example, from the figure, one can observe that a spacecraft with and requires about of propellant to complete the transfer (the BepiColombo spacecraft, for comparison, carried of propellant at the beginning of its transfer), while the scientific payload mass obtained through the statistical model is slightly below .

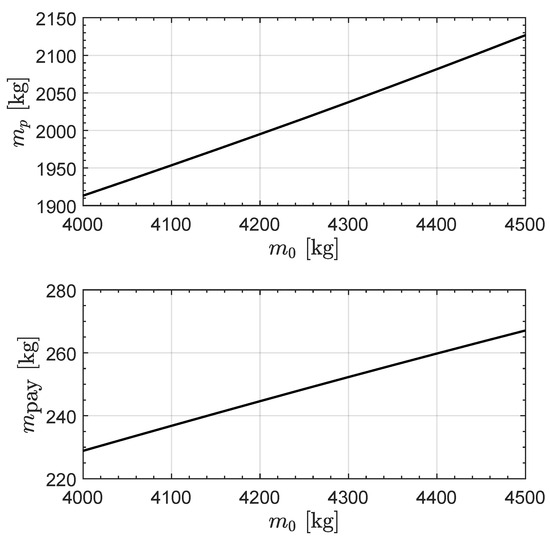

Figure 3.

Propellant () and payload () mass for an Earth–Mars orbit-to-orbit transfer as a function of and .

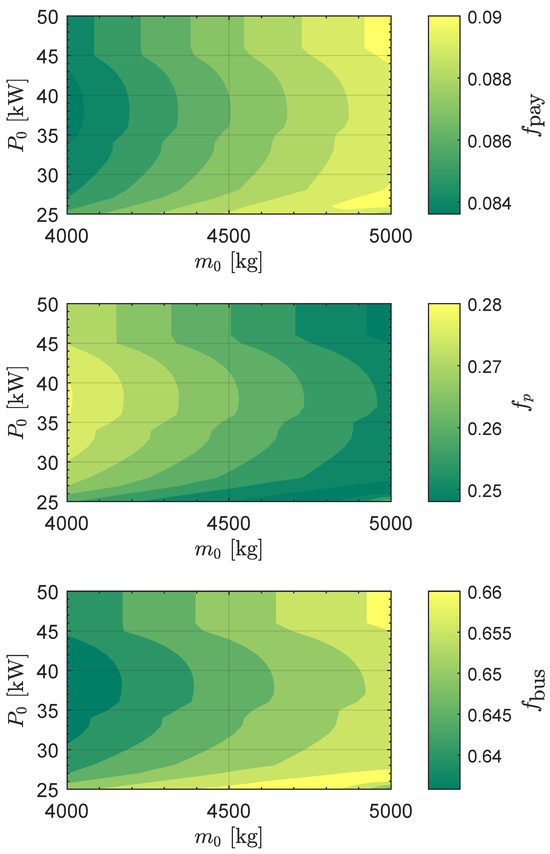

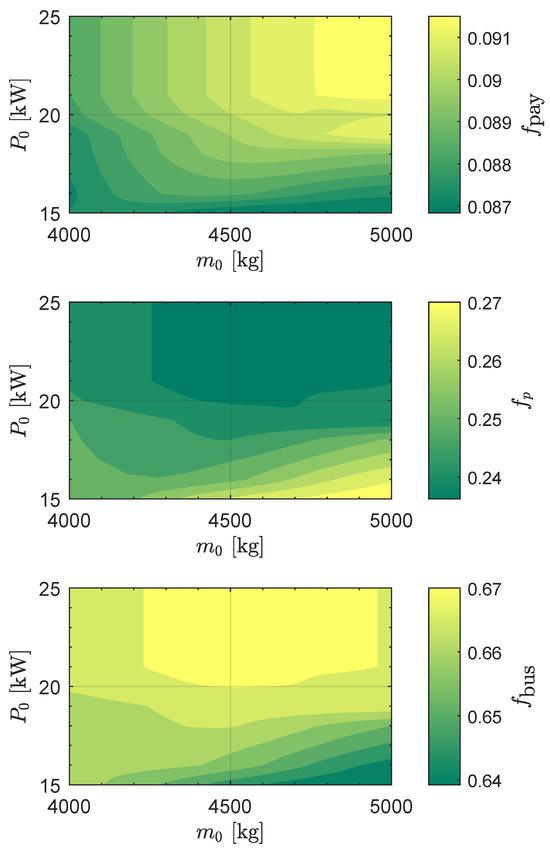

These values of and correspond to mass fractions of and , respectively. This is confirmed by Figure 4, which also shows the variation of with the two design parameters and . In particular, the same combination of launch mass and reference electric power gives about .

4.2. Earth-Venus Mission

The same procedure illustrated in the previous subsection was used to parametrically investigate the transfer performance in an Earth–Venus scenario. In this case, the initial spacecraft mass still lies within the interval , while—bearing in mind that the transfer is now toward an inner region of the Solar System—the reference electric power was selected in the range .

The results of the numerical optimizations provide the minimum flight time, , shown in Figure 5. The trend of the level curves is similar to that observed in the Earth–Mars scenario (see Figure 2). For example, assuming again , the flight time is about (or ) when (or ). Conversely, if the initial mass is , the minimum flight time ranges between and , with an excursion of about one hundred days.

The results in terms of propellant mass and payload mass are reported in Figure 6, where one can observe that and . Finally, the mass fractions are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 4.

Mass fractions defined in Equation (11) for an Earth–Mars orbit-to-orbit transfer as a function of and .

Figure 5.

Minimum flight time for an Earth–Venus orbit-to-orbit transfer.

Figure 6.

Propellant () and payload () mass for an Earth–Venus orbit-to-orbit transfer.

Figure 7.

Mass fractions for an Earth–Venus orbit-to-orbit transfer.

4.3. Earth-Asteroid 2024 YR4 Mission

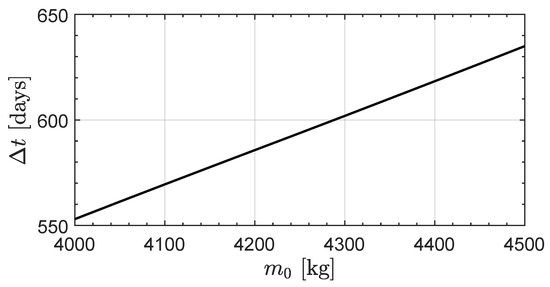

The asteroid-based mission scenario was analyzed by considering a singe (fixed) value of to reduce the computational cost of the parametric study, and an initial spacecraft mass ranging within the interval , with a step of . In this case, the minimum flight time ranges between and , as shown in Figure 8. The corresponding propellant mass varies from about to , while the payload mass is on the order of ; see Figure 9. For instance, the solar sail-based mission scenario analyzed in Ref. [34] gives a flight time of about 7 years when the initial propulsive acceleration of the spacecraft is roughly .

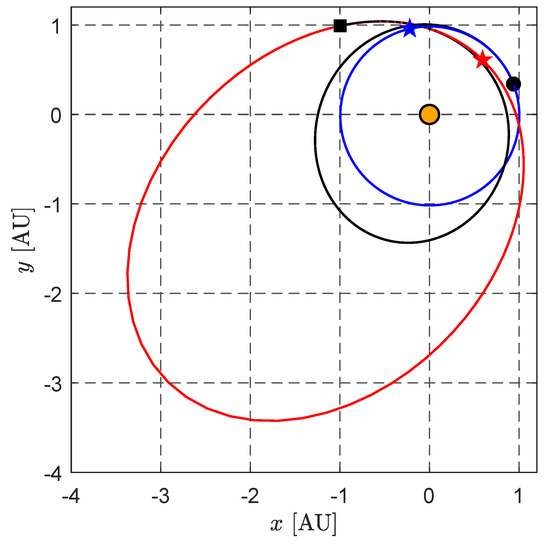

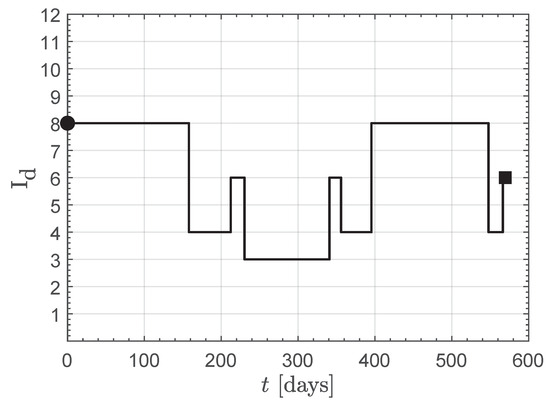

Consider the case study in which the initial spacecraft mass is . In this specific scenario, the minimum flight time and the spacecraft mass breakdown (obtained using the simplified approach described in the previous section) are reported in Table 3. The resulting masses yield the following fractions: , , and . The sketch of the optimal spacecraft transfer trajectory is reported in Figure 10, while Figure 11 shows the temporal variation of the control term during the rapid interplanetary transfer. In particular, Figure 11 shows that this specific rapid transfer requires four thrust levels, namely . In other words, the TEPS operates in both OC and DC modes during the flight.

Figure 8.

Minimum flight time for an Earth–asteroid 2025 YR4 transfer when .

Figure 9.

Propellant and payload mass for an Earth–asteroid 2025 YR4 transfer when .

Table 3.

Results for the rapid Earth–asteroid 2025 YR4 transfer with and .

Table 3.

Results for the rapid Earth–asteroid 2025 YR4 transfer with and .

| Term | Value |

|---|---|

Figure 10.

Rapid transfer trajectory for an Earth–asteroid 2025 YR4 transfer (ecliptic projection) when and . Orange dot → the Sun; black dot → start; black square → arrival; blue star → Earth’s perihelion; red star → asteroid orbit’s perihelion; blue line → Earth’s orbit; red line → asteroid’s orbit; black line → spacecraft trajectory.

Figure 11.

Optimal thrust level for an Earth–asteroid 2025 YR4 transfer when and . Black dot → start; black square → arrival.

5. Conclusions

This paper has analyzed the transfer performance of an interplanetary spacecraft equipped with a TANDEM electric propulsion system across a set of potential heliocentric mission scenarios. The specific capability of this Hall-effect thruster, which can operate in either single- or dual-channel mode, provides greater flexibility in selecting the most appropriate thrust level at any point along a heliocentric transfer trajectory.

In this context, the performance in terms of flight time and required propellant mass was investigated parametrically as a function of the spacecraft’s initial inertial characteristics and the reference electric power supplied by the solar array subsystem. The simulations indicate that a large spacecraft, with an initial (total) mass comparable to that of ESA/JAXA’s BepiColombo, requires a minimum flight time of about one year to reach Mars in a simplified orbit-to-orbit mission scenario. This transfer time should be regarded as the minimum admissible value, since in an ephemeris-constrained case the relative angular positions of the planets will degrade mission performance by increasing the flight time.

The results also show that the characteristics of the transfer trajectory depend on the reference (installed) electric power, which directly affects the number of thrust levels that can be selected at a given solar distance during the transfer. In this study, a simplified mathematical model for the variation of available electric power with Sun–spacecraft distance was adopted. A more refined model—accounting, for example, for the temporal degradation of the solar panels and possible constraints on array orientation during the flight—could be considered as a future extension of this work. In fact, if both the degradation of the solar cell film and potential attitude constraints on the solar panel orientation are included in the mathematical model, the result would be a reduction in the available thrust levels at any point along the transfer trajectory, given that the reference value of the electric power remains fixed. This, in turn, would affect the characteristics of the thrust vector and ultimately the flight time performance. Quantifying this type of performance degradation is difficult without a specific calculation of the optimal transfer trajectory.

Once such a refined model for calculating the available electric power is implemented, the transfer performance can be assessed in a more realistic, ephemeris-constrained scenario. This would enable the identification of the most suitable launch windows, starting from the ephemeris-free results obtained with the approach presented in this paper. Another potential extension of this work involves analyzing a more common geocentric mission scenario, where the TANDEM-based propulsion system equips a reusable orbital transfer vehicle, enabling the geocentric orbital transfer of small satellites.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations and symbols are used in this manuscript:

| Acronyms | |

| BVP | Boundary value problem |

| COMPASS | Collaborative Modeling for Parametric Assessment of Space Systems |

| DC | Dual channel |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| IC | Inner channel |

| JAXA | Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency |

| JPL | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NEXT | NASA’s Evolutionary Xenon Thruster |

| OC | Outer channel |

| PPU | Power Processing Unit |

| RTN | Radial–transverse–normal reference frame |

| SEP | Solar electric propulsion |

| TEPS | TANDEM electric propulsion system |

| State matrix; see Equation (A1) | |

| a | Semimajor axis [AU] |

| Best-fit coefficient [kg] | |

| Best-fit coefficient | |

| Vector; see Equation (A1) | |

| e | Eccentricity |

| Hamiltonian function | |

| Thruster’s operating point | |

| Specific impulse [s] | |

| i | Orbital inclination [deg] |

| m | Spacecraft mass [kg] |

| Bus mass [kg] | |

| Mass of the command and data handling subsystem [kg] | |

| Mass of the communications subsystem [kg] | |

| Dry mass [kg] | |

| Mass of the guidance, navigation, and control subsystem [kg] | |

| Propellant mass [kg] | |

| Payload mass [kg] | |

| Mass of the power subsystem [kg] | |

| Mass of the propulsion subsystem [kg] | |

| Structure mass [kg] | |

| Mass of the thermal subsystem [kg] | |

| Propellant mass flow rate [mg/s] | |

| P | PPU input power [kW] |

| Solar array output power at [kW] | |

| Available electric power for the thruster [kW] | |

| Electric power allocated to other subsystems [kW] | |

| Modified equinoctial elements | |

| r | Sun–spacecraft radial distance [AU] |

| T | Thrust magnitude [mN] |

| t | Time [days] |

| Thrust unit vector | |

| Flight time [days] | |

| Duty cycle | |

| Adjoint vector | |

| Generic adjoint variables | |

| Argument of perihelion [deg] | |

| Right ascension of the ascending node [deg] | |

| Subscripts | |

| 0 | initial |

| DC | related to the DC mode |

| f | final |

| IC | related to the IC mode |

| OC | related to the OC mode |

| Superscripts | |

| · | temporal derivative |

| T | transpose |

Appendix A

This section provides a concise description of the mathematical model adopted to represent the heliocentric dynamics of the TEPS-propelled spacecraft and to optimize its transfer trajectory in a generic orbit-to-orbit scenario. The model is based on the formulation presented in Ref. [23], originally developed to analyze the performance of a probe equipped with an electric thruster for a scientific mission toward the inner regions of the Solar System.

The spacecraft’s heliocentric dynamics is expressed in terms of the six modified equinoctial elements [36], where L denotes the true longitude, the angular parameter that essentially defines the position of the vehicle along its osculating orbit. In this framework, L is left free at both the beginning of the transfer (i.e., along Earth’s orbit) and the end of the flight (i.e., along the target heliocentric orbit), consistent with the orbit-to-orbit transfer assumption. The initial and final values of L are therefore determined as outputs of the optimization process.

The use of modified equinoctial elements, as is well known, avoids the singularities that arise when classical orbital elements are employed to describe the spacecraft’s dynamics [36]. In this context, considering only the gravitational attraction of the Sun and the thrust provided by the TEPS, recalling that the vehicle’s mass varies during the transfer when , and defining the spacecraft’s state vector as , the vehicle’s equations of motion can be expressed in the following compact vector form:

where is a matrix whose entries depend on the seven state (scalar) variables, and is a vector with only two nonzero components. The explicit expressions of and can be found in Equations (8) and (9) of Ref. [37]. In particular, the components of the thrust vector appearing in the previous equation should be computed in a classical right-handed radial–transverse–normal (RTN) reference frame, where the radial direction coincides with the Sun–spacecraft line, the normal direction aligns with the specific angular momentum vector, and the spacecraft’s heliocentric velocity vector has a positive component along the transverse direction.

Given that the initial spacecraft mass is assigned parametrically and the shape and orientation of the parking orbit (i.e., Earth’s orbit) are known (see Table 2), six initial scalar conditions of Equation (A1) are specified, while the initial value of L is determined by solving an optimal control problem. This problem is formulated using the calculus of variations [38] by introducing the adjoint vector , which allows the Hamiltonian to be expressed as , where is given by the right-hand side of Equation (A1) and depends on the state and control variables, i.e., .

The analytical expression of the Hamiltonian function is used to derive both the optimal control law and the seven Euler–Lagrange equations, which define the time derivatives of the adjoint vector . The optimal control law is determined according to Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle by computing, at each instant, the local values of the controls that maximize the Hamiltonian through a numerical optimization procedure. The Euler–Lagrange equations are obtained analytically from their definition .

The boundary value problem (BVP) for the optimization procedure is formulated by imposing the final conditions that match the target orbit values of , along with the transversality condition [38]. This condition specifies that the initial and final values of the adjoint variable are zero, the final value of is zero, and the Hamiltonian equals 1, since the total flight time is treated as an optimization output. From a numerical perspective, the equations of motion and the Euler–Lagrange equations were integrated using a PECE solver based on the classical Adams–Bashforth method [39] with a tolerance of , while the BVP was solved through a multiple shooting approach [40].

References

- Rayman, M.D. The successful conclusion of the Deep Space 1 mission: Important results without a flashy title. Space Technol. 2003, 23, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, A.; Anderson, J.A.; Gamer, C.; Brophy, J.R.; De Groh, K.K.; Banks, B.A.; Thomas, T.A.K. Deep space 1 flight spare ion thruster 30,000-hour life test. J. Propuls. Power 2009, 25, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J.R. Perspectives on the success of electric propulsion. J. Electr. Propuls. 2022, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, J.; Fujiwara, A.; Uesugi, T. Hayabusa—Its technology and science accomplishment summary and Hayabusa-2. Acta Astronaut. 2008, 62, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. The Falcon Has Landed. Science 2006, 312, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhoff, J.; van Casteren, J.; Hayakawa, H.; Fujimoto, M.; Laakso, H.; Novara, M.; Ferri, P.; Middleton, H.R.; Ziethe, R. BepiColombo-Comprehensive exploration of Mercury: Mission overview and science goals. Planet. Space Sci. 2010, 58, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, N. Testing of the Qinetiq T6 Thruster in Support of the ESA BepiColombo Mercury Mission for the ESA BepiColombo Mission. In Proceedings of the 4th International Spacecraft Propulsion Conference, Chia Laguna, Italy, 2–9 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boretti, A. A narrative review of solar electric propulsion for space missions: Technological progress, market opportunities, geopolitical considerations, and safety challenges. J. Space Saf. Eng. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Dutt, P.; Negi, D.; Kumar, A.; Ashok, V. Analysis of Direct Interplanetary Transfers Using Solar-Electric Propulsion. In Advances in Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization; Pradeep Pratapa, P., Saravana Kumar, G., Ramu, P., Amit, R.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; Chapter 5; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prussing, J.E. Optimal Spacecraft Trajectories; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Chapter 4; pp. 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kluever, C.A. Efficient Computation of Optimal Interplanetary Trajectories Using Solar Electric Propulsion. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2015, 38, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawden, D.F. Optimal Trajectories for Space Navigation; Butterworths & Co.: London, UK, 1963; Chapter 6; pp. 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, J.T. Survey of Numerical Methods for Trajectory Optimization. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 1998, 21, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganucci, F.; Becatti, G.; Burgalassi, F.; Giammarinaro, G.; Marconcini, F.; Pasini, A.; Saravia, M.; Dini, F.; Scortecci, F.; Estublier, D. Development of a High Power, Magnetically Shielded, Dual Channel Hall Thruster in The Framework of the TANDEM Project. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Space Propulsion, Estoril, Portufal, 9–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Paganucci, F.; Becatti, G.; Burgalassi, F.; Giammarinaro, G.; Marconcini, F.; Pasini, A.; Poli, D.; Saravia, M.; Dini, F.; Scortecci, F.; et al. TANDEM: A High Power, Magnetically Shielded Hall Thruster with a Nested Configuration. In Proceedings of the 37th International Electric Propulsion Conference, Cambridge, MA, USA, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, B.T.; Hanuš, J.; Denneau, L.; Bonamico, R.; Abron, L.M.; Delbo, M.; Ďurech, J.; Jedicke, R.; Alcorn, L.Y.; Cikota, A.; et al. The Discovery and Characterization of Earth-crossing Asteroid 2024 YR4. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 984, L25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegert, P.; Brown, P.; Lopes, J.; Connors, M. The Potential Danger to Satellites due to Ejecta from a 2032 Lunar Impact by Asteroid 2024 YR4. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 990, L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammarinaro, G.; Marconcini, F.; Becatti, G.; Saravia, M.M.; Andrenucci, M.; Paganucci, F. A scaling methodology for high-power magnetically shielded Hall thrusters. J. Electr. Propuls. 2023, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconcini, F.; Giammarinaro, G.; Becatti, G.; Saravia, M.; Guidi, C.; Paganucci, F.; Dini, F.; Scortecci, F.; Estublier, D. A 20 kW Magnetically Shielded Nested Hall Thruster: Status and Perspectives of the TANDEM Project. In Proceedings of the Space Propulsion 2024, Glasgow, UK, 20–23 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paganucci, F.; Andrenucci, M. Electric Propulsion Activities at the University of Pisa. In Proceedings of the 38th International Electric Propulsion Conference, Toulouse, France, 23–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paganucci, F.; Becatti, G.; Saravia, M.; Giammarinaro, G.; Marconcini, F.; Camarri, S.; Razionale, A.V. Electric Propulsion Activities at DICI-Unipi. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Space Propulsion, Estoril, Portugal, 9–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scaranzin, S.; Scortecci, F.; Bonelli, E.; Sestini, L.; Bartali, M.; Avanzi, F.; Cesari, U.; Dini, F.; Cannelli, F.; Giammarinaro, G.; et al. Characterisation of a 20 kW Dual Channel HET in the Framework of the ESA TANDEM Project. In Proceedings of the 38th International Electric Propulsion Conference (IEPC2024), Toulouse, France, 23–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quarta, A.A.; Izzo, D.; Vasile, M. Time-Optimal Trajectories to Circumsolar Space Using Solar Electric Propulsion. Adv. Space Res. 2013, 51, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Benson, S.W. NEXT ion propulsion system developmentstatus and performance. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 8–11 July 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, A.A. Effects of Discrete Thrust Levels on the Trajectory Design of the BIT-3 RF Ion Thruster-Equipped CubeSat. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, M. 3,500-Hour Wear Test Result of BIT-3 RF Ion Propulsion System. In Proceedings of the 37th International Electric Propulsion Conference, Cambridge, MA, USA, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Busek Co., Inc. BIT-3: Compact and Efficient Iodine Gridded ion Thruster. 2025. Available online: https://www.busek.com/bit3 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Rovey, J.L.; Lyne, C.T.; Mundahl, A.J.; Rasmont, N.; Glascock, M.S.; Wainwright, M.J.; Berg, S.P. Review of multimode space propulsion. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2020, 118, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, A.A.; Bassetto, M.; Becatti, G. Optimal Heliocentric Orbit Raising of CubeSats with a Monopropellant Electrospray Multimode Propulsion System. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerberich, M.; Oleson, S.R. Estimation Model of Spacecraft Parameters and Cost Based on a Statistical Analysis of COMPASS System Designs. In Proceedings of the AIAA SPACE 2013 Conference and Exposition, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 September 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayman, M.D.; Williams, S.N. Design of the First Interplanetary Solar Electric Propulsion Mission. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2002, 39, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurre, N.P.; Taheri, E. Duty-cycle-aware low-thrust trajectory optimization using embedded homotopy. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 212, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseev, Y.A.; Emelyanov, N.V. Ephemeris Theories JPL DE, INPOP, and EPM. Astron. Rep. 2024, 68, 1098–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, A.A. Using Solar Sails to Rendezvous with Asteroid 2024 YR4. Technologies 2025, 13, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, M.; Schalkwyk, J.; Çelik, O.; Sengupta, D.; Fujino, K.; Hein, A.M.; Tenorio, L.; Cardoso dos Santos, J.; Worden, S.P.; Mauskopf, P.D.; et al. Space sails for achieving major space exploration goals: Historical review and future outlook. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 150, 101047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.J.H.; Ireland, B.; Owens, J. A set of modified equinoctial orbit elements. Celest. Mech. 1985, 36, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, A.A.; Mengali, G.; Bassetto, M. Rapid orbit-to-orbit transfer to asteroid 4660 Nereus using Solar Electric Propulsion. Universe 2023, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, A.E.; Ho, Y.C. Applied Optimal Control; Hemisphere Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1975; Chapter 2; pp. 71–89. ISBN 0-891-16228-3. [Google Scholar]

- Shampine, L.F.; Reichelt, M.W. The MATLAB ODE Suite. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 1997, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Y.; Cao, W.; Kim, J.; Park, K.W.; Park, H.H.; Joung, J.; Ro, J.S.; Hong, C.H.; Im, T. Applied Numerical Methods Using MATLAB; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Chapters 3 and 6; pp. 158–165, 312. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).