Abstract

Identifying malware families is vital for predicting attack campaigns and creating effective defense strategies. Traditional signature-based methods are insufficient against new and evasive malware, highlighting the need for adaptive, multimodal solutions. This paper proposes a deep learning framework that fuses visual and static features through a ConvNeXt-Tiny backbone with cross-attention integration and incorporates calibration strategies such as snapshot ensembling, test-time augmentation, and per-class bias adjustment. The model is evaluated on two publicly available datasets: Malimg and Fusion Malware. The results demonstrate an outstanding accuracy of 99.69% on Malimg and 98.67% on Fusion, with macro F1 scores of 99.22% and 98.12%, respectively. Bias calibration improved the detection of difficult families on Malimg, and error analysis of Fusion identified challenges with polymorphic and underrepresented families. Overall, combining multimodal fusion with lightweight calibration enhances robustness and interpretability for real-world malware detection and attribution.

1. Introduction

The rapid rise of malware poses a substantial challenge to cybersecurity, targeting both individuals and critical infrastructures [1]. Traditional signature-based detection methods are now insufficient against the maturing and elusive tactics of modern malware [2,3]. This shortcoming makes it difficult for analysts to accurately identify malware families and, more importantly, attribute them to specific campaigns—an essential step in anticipating threats and deploying targeted countermeasures [4].

Deep learning–based malware classification typically follows a structured pipeline consisting of data preprocessing, feature extraction, model training, and performance evaluation. During the preprocessing stage, raw binary files, system call logs, or network traffic are standardized and converted into formats that can be processed by neural networks—like byte sequences, image textures, or opcode frequency vectors. The feature extraction stage focuses on pinpointing distinctive traits using convolutional or recurrent networks. CNNs excel at capturing spatial and structural relationships in malware binaries, while RNNs and LSTMs are more adept at analyzing sequential behaviors, such as API calls or instruction traces. After features are extracted, the network parameters are fine-tuned using gradient-based methods, and the model’s performance is evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and ROC AUC.

This work introduces a multimodal fusion framework that combines visual and static representations using a ConvNeXt-Tiny backbone with cross-attention. This architecture enhances traditional unimodal models that use bytecode or image features [5] by capturing additional spatial and statistical properties of malware. It also includes a snapshot-ensemble mechanism for robust performance, comparable to multiple networks, while keeping training costs low. Additionally, the bias-calibration step improves the detection of rare or hard-to-classify families, and the model’s cross-attention design supports transfer to new or unseen malware variants by learning shared abstract feature spaces. The contributions of this work are threefold:

- A multimodal fusion architecture combines grayscale images with handcrafted and convolutional neural network (CNN)-derived features to enhance malware family classification.

- A calibration pipeline uses ensemble averaging and lightweight logit adjustments to improve generalization and robustness against class imbalance in difficult malware families.

- An evaluation of two benchmark datasets demonstrates improved accuracy and macro F1 performance while highlighting challenges like polymorphism and underrepresentation.

By integrating multimodal feature fusion with bias-aware calibration, this study improves malware attribution, offering a practical and scalable solution for threat intelligence systems. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the related malware classification approaches. Section 3 presents the proposed multimodel method. Section 4 illustrates and discusses the results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

This section reviews previous research, and Table 1 contrasts our approach with existing studies. Nazim et al. [6] propose a multimodal ensemble deep neural network framework that integrates numeric and visual data modalities for malware classification using a late fusion technique. The proposed framework combines numerical features from the CCCS-CIC-AndMal-2020 dataset [7,8] with visual features from a blended malware image dataset (Malevis [9] and Malimg [10]), achieving an accuracy of 95.36%—a result that surpasses the performance of individual unimodal approaches. Its main strengths are enhanced robustness and precision from the combination of numerical and visual modalities. However, it faces limitations, including lower performance in specific malware categories due to class imbalance and the complexity of feature representation.

Li et al. [11] introduce a detection method that identifies malware families utilizing self-learning weighting and multimodel fusion. Such approaches are practical in encountering the challenges of imbalanced datasets. The technique combines features from various inputs, including file format properties, byte sequences, semantic content, and statistical patterns. The authors utilize weighted soft voting and feature fusion to improve classification robustness. The approach has been evaluated on two imbalanced datasets (i.e., CCF BDCI-21 and Microsoft BIG-15 [12]), which show decent accuracy. However, the prediction time of the proposed method is slightly high.

Cruickshank and Carley [13] introduce Crossmodal Influence Clustering (CMIC), an unsupervised method for assigning malware samples to threat actor groups by integrating various strategies. The approach utilizes static features from Saxe and Berlin [14]—specifically, byte entropies, import address tables, string hashes, and PE headers—extracted from 2185 samples attributed to three known threat actors (Advanced Persistent Threat (APT)-1, Dukes, and Deep Panda). CMIC outperforms various multimodal clustering baselines in terms of Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Adjusted Mutual Information (AMI) scores. Intermediate and late integration methods typically yield better attribution results than early fusion. However, this approach is limited to static analysis and may not apply well to dynamic features or diverse malware ecosystems.

Jiang and Stamp [15] propose a structured multimodal machine learning approach for malware classification based on distinct regions of Windows Portable Executable (PE) files. Using the Malicia dataset [16] (2114 samples from five malware families), they train support vector machines (SVMs), long short-term memory (LSTM), and CNN models on features extracted from PE headers, sections, and full files and then combine the model outputs via late fusion using an SVM classifier. The multimodal models outperform unimodal baselines, with the best combination (CNN, CNN, and SVM) achieving 99.30% accuracy. Despite this performance, the approach is limited to static features and tested on a relatively small, imbalanced dataset, suggesting the need for broader validation and dynamic feature integration.

Ismail et al. [17] present a malware detection method that combines features from images and audio utilizing late fusion methods. The framework employs self-supervised learning (SSL) to extract visual features and a CNN to analyze audio spectrograms. Evaluated on two datasets—BODMAS and the newly introduced Maldeb—MIDALF achieved up to 99.7% accuracy and demonstrated strong resilience against adversarial malware generated by generative adversarial networks (GANs) (95.1% accuracy). It offers high classification performance, adversarial robustness, and scalability without needing behavior-based features but suffers from computational overhead and limited interpretability.

Johny et al. [18] introduce a deep learning approach for malware detection that combines three visual representations—grayscale images, entropy graphs, and Simhash images—from malware binaries. They trained separate VGG16 models for each representation using the BIG2015 dataset. They combined them using different fusion strategies (add, average, max, and concatenate), demonstrating that concatenation outperformed all other fusion methods, achieving a perfect F1 score and near-instantaneous prediction times. Their method shows high accuracy, robustness against obfuscated malware, and interpretability through gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) visualizations, albeit at the cost of increased computational complexity during fusion.

Snow et al. [19] present an end-to-end multimodel deep learning framework that incorporates dense networks, CNNs, and LSTMs to classify malware by cooperatively learning from metadata, bytecode images, and opcode sequences. Trained on the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (MMCC) dataset, the model achieved a best accuracy of 99.23% and a mean cross-validation accuracy of 98.35%, with training completed in only 35 min—significantly faster than ensemble-based models. The framework eliminates manual feature engineering, provides good adaptability to other datasets, and achieves competitive accuracy without relying on pretrained networks or ensemble techniques. However, its dependence on static features and the time needed for feature extraction may restrict its use in real-time situations without further optimization.

Kim et al. [20] create a one-dimensional deep learning method to classify Android malware families using raw string data from Android application package (APK) and certificate files. Their model uses Grad-CAM analysis to identify important features and combines them through a multi-stream design. In tests on the DREBIN [21,22] and AMD datasets, it achieved an accuracy of 93.2%, outperforming well-known two-dimensional CNN models, such as ResNet50 and Inception-V3. This approach is efficient and scalable, as it does not require disassembly, decryption, or dynamic execution. However, it may lead to longer inference times, and it focuses only on static features.

Kim et al. [23] introduce a crossmodal CNN specifically designed for malware classification using non-disassembled binary files. This model incorporates malware images with structural entropy representations using 1D CNNs and a crossmodal attention mechanism. This approach avoids disassembly issues. It was tested on datasets such as the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge, Malimg, and BODMAS-14, achieving an accuracy of up to 99.09% on Malimg. It outperforms unimodal methods and late-fusion techniques, especially with imbalanced or obfuscated samples. However, the model remains confined to static analysis and may require modifications to incorporate behavioral or semantic features.

Guo et al. [24] introduce a multimodal deep learning framework for malware open-set recognition (MOSR), which classifies known malware families and detects unknown ones. The framework combines numeric features from EMBER [25] with textual features from bidirectional encoder representations from transformer (BERT)-like models, using a multi-scale CNN for numeric malware images and transformers for behavioral embeddings. These multimodal representations are fused and projected into dual-embedding spaces—discriminative and exclusive—enhanced via contrastive learning and -bounded enclosing sphere constraints to improve classification and novelty detection. Evaluations on the Mailing dataset and the large MAL-100+ dataset demonstrate state-of-the-art performance, with classification and detection accuracies of 99.32% and 90.77% on the Mailing dataset, and 94.30% and 90.40% on the MAL-100+ dataset, respectively. Key advantages include robust multimodal fusion, better generalization to unseen families, and efficient open-set detection. However, reliance on complex model architecture may limit deployment in real-time or resource-constrained environments.

Dandan et al. [26] develop a lightweight convolutional neural network for malware image classification. It features multi-scale kernel (MK) blocks, improved squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks, and GridMask-based data augmentation to enhance robustness and efficiency. The model achieved 99.25% accuracy on the Malimg dataset and 98.63% on the BIG 2015 dataset, outperforming many baseline methods in both performance and efficiency. The technique is remarkable because it is accurate and lightweight and the feature extraction is efficient. However, its main limitations are the large number of hyperparameters and limited integration of multimodal features beyond image data.

Table 1.

Comparison of multimodal malware classification approaches.

Table 1.

Comparison of multimodal malware classification approaches.

| Study | Dataset(s) | Accuracy/Results | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nazim et al. [6] | CCCS-CIC-AndMal-2020, Malevis and Malimg | 95.36% | Robustness and precision via numeric and visual fusion; improved over unimodal methods | Lower performance on imbalanced families; complex feature representation |

| Li et al. [11] | CCF BDCI-21, Microsoft BIG-15 | High accuracy, resource-efficient | Handles imbalance and concept drift; minimal computational cost | Limited prediction efficiency |

| Cruickshank and Carley [13] | Saxe and Berlin static features (2185 samples, 3 attack groups) | Outperforms multimodal baselines based on ARI and AMI | Effective attribution; robust, parameter-efficient clustering | Limited to static features; generalization to dynamic data untested |

| Jiang and Stamp [15] | Malicia (2114 samples, 5 families) | 99.30% (CNN, CNN, and SVM) | Late fusion of PE regions; outperforms unimodal baselines | Static-only; small, imbalanced dataset limits generalization |

| Ismail et al. [17] | BODMAS, Maldeb | 99.7%; adversarial 95.1% | Integrates image and audio; high accuracy; resilient to adversarial GAN malware | Computational overhead; limited interpretability of fusion |

| Johny et al. [18] | BIG2015 | Perfect F1 score (concat fusion) | Combines grayscale, entropy, Simhash images; interpretable with Grad-CAM and t-SNE | Computationally intensive fusion |

| Snow et al. [19] | Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (MMCC) | 99.23% best, 98.35% mean CV | End-to-end multimodel (DenseNet, CNN, and LSTM); fast training; no manual features | Static-only; moderate feature extraction time |

| Kim et al. [20] | DREBIN and AMD | 93.2% | Efficient multi-stream CNN on raw APK sections; disassembly-free | Static-only; longer inference time |

| Kim et al. [23] | Microsoft MMC, Malimg, BODMAS-14 | Up to 99.09% on Malimg | Crossmodal attention on non-disassembled binaries; robust against imbalance datasets | Limited to static analysis; lacks behavioral features |

| Guo et al. [24] | Mailing, MAL-100+ | 99.32% (classification), 90.77% (detection) on Mailing; 94.30% (classification), 90.40% (open-set detection) on MAL-100+ | Novel MOSR framework; robust fusion; effective novelty detection | Complex architecture may hinder deployment |

| Dandan et al. [26] | Malimg, BIG2015 | 99.25% (Malimg), 98.63% (BIG2015) | Lightweight IMCMK-CNN; high accuracy; efficient | Hyperparameter-heavy; image-only |

| Our Method | Malimg (25 families), Fusion Malware (59 families) | 99.69% (Malimg), 98.67% (Fusion) | Multimodal fusion (images and static features); interpretable | Remaining challenges on imbalanced families |

3. Proposed Method

We propose a multimodal malware family classifier that fuses image evidence with a compact static vector through cross-attention. Visual data are processed with grayscale images resized to . The visual backbone is ConvNeXt-Tiny [27], whose last feature map feeds an attention-based [28] fusion block and a Generalized Mean (GeM) pooling head. Static vectors are z-score normalized (mean/std over the available samples). Classification is performed by a multilayer perceptron (MLP) [29] on the concatenation of the attention output and the pooled visual descriptor.

We evaluated our method using two publicly available datasets (i.e., the Malimg and Fusion Malware datasets). For the Malimg dataset, we adopt a snapshot-ensemble evaluation [30]. Multiple training snapshots are loaded, and for each snapshot, we run 8-view test-time augmentation (TTA) consisting of horizontal and vertical flips, as well as rotations of and . For every augmented view, we compute softmax probabilities and average them; then, we average across snapshots. Finally, we learn a per-class bias vector on the validation set by grid search in the range with step . The bias values are added to the ensemble logits at test time. This post hoc calibration rescues hard-to-classify families without requiring retraining.

For the Fusion Malware dataset, we precompute a hybrid static feature for each image consisting of the intensity mean and standard deviation (2D), a Local Binary Pattern (LBP) histogram with uniform pattern (10D), and a global ConvNeXt-Tiny embedding extracted from a separate convnext head. The three parts are concatenated and z-scored to form the static vector. The classifier is trained for 20 epochs with AdamW, cosine warm restarts, and label smoothing (), and the best validation checkpoint is evaluated on the test split without ensemble or bias calibration.

The static branch was designed to capture complementary characteristics of malware binaries without excessive preprocessing. For the Malimg dataset, a compact three-dimensional static vector derived from the Portable Executable (PE) header and file metadata was used, normalized by the z-score. For the Fusion Malware dataset, a richer hybrid static representation was constructed to provide both low-level and high-level information. This representation concatenates on the image intensity mean and standard deviation, which summarize the global distribution of the pixel values and relate to the binary’s overall entropy, a ten-dimensional Local Binary Pattern (LBP) histogram that encodes local textural patterns, enabling the model to detect fine-grained structural similarities among families, and a ConvNeXt-Tiny embedding extracted from a separate frozen CNN head, representing deep semantic features learned from large-scale image data. These components were chosen because they provide complementary viewpoints—statistical, structural, and semantic—while keeping a moderate feature dimensionality appropriate for multimodal fusion. The CNN-based embedding, especially, was selected for its established capability to capture high-level compositional signals across various malware visualizations, improving generalization to new families. To ensure reproducibility, a summary of training hyperparameters, optimization configurations, and hardware details can be found in Appendix A, particularly in Table A1.

Mathematical Model

Each sample consists of a grayscale malware image and a normalized static vector . Let K be the number of families. The model predicts a categorical distribution by fusing image evidence with the static vector through cross-attention and then classifying with a small MLP.

A ConvNeXt-Tiny backbone produces a final convolutional feature map of channel width C and spatial size :

We flatten F into (i.e., patch tokens), each of dimension C:

The static vector is projected to the same channel width to serve as a single query:

Let h be the number of heads and the per-head width. For each head j, we form projections of the query and the patch tokens:

Scaled dot-product attention (one query attending all L patches) yields a per-head output , which are concatenated and linearly projected:

In parallel, we compute a global image descriptor using Generalized Mean pooling:

where controls the pooling sharpness (for this reduces to average pooling).

We concatenate the attention summary (static to visual alignment) with the global visual descriptor and then feed the result to a two-layer MLP with ReLU and dropout :

The K-dimensional logits z are converted to class probabilities with softmax.

We train with cross-entropy and label smoothing , AdamW, and cosine warm restarts:

For the Fusion dataset we apply MixUp jointly to image and static branches on ):

The MixUp loss is the convex combination used in the training loop:

On the Malimg dataset, we use snapshot ensembling and 8-view TTA (flips/rotations). Let denote the t-th augmentation and the m-th checkpoint. We average probabilities over all views and snapshots and then apply a per-class bias learned by grid search on validation:

On the Fusion dataset, we use the single best checkpoint without TTA or bias ( , ), which reduces the expression above to a standard .

4. Results and Discussion

The proposed snapshot-ensemble with bias calibration achieved outstanding performance on the Malimg dataset. Using three checkpoints and eight-view test-time augmentation (TTA), the ensemble reached a final test accuracy of 99.69%. Validation accuracy improved after the addition of learned per-class biases , yielding 99.67% on the validation set. The detailed classification report shows that almost all malware families achieved perfect precision, recall, and F1 scores. Only a few of the classes exhibited marginal deviations: Lolyda.AA1 (F1 = 0.9778), Lolyda.AT (F1 = 0.9697), Swizzor.gen!E (F1 = 0.9231), and Swizzor.gen!I (F1 = 0.9333). These families display polymorphic behavior and resemble other classes, making them hard to distinguish. The model improved misclassifications for specific malware families that have negative bias values, such as Allaple.A, VB.AT, and Wintrim.BX. It achieved a macro-averaged F1 score of 0.9922, showing strong performance across various malware family sizes.

On the more challenging Fusion Malware dataset, which comprises 59 families and nearly 5000 test samples, the proposed fusion model achieved a final test accuracy of 98.67% with a best validation accuracy of 98.88%. Precision, recall, and F1 scores were consistently high across most families. Families like Adialer.C, Allaple.A, Kelihos_ver3, Lollipop, and Ramnit achieved nearly perfect results, demonstrating the effectiveness of the multimodal fusion representation. However, some families faced challenges. For instance, Swizzor.gen!I had an F1 score of 0.8372 due to low precision, while Sality scored 0.8974 with a recall below 94%. Simda, with only seven samples, attained an F1 score of 0.9231. These cases show the model’s sensitivity to unbalanced families and a lack of sufficient training samples, which are common issues in malware datasets. Nevertheless, the macro-averaged F1 score of 0.9812 and weighted average of 0.9868 highlight the effectiveness of combining ConvNeXt-Tiny visual embeddings with handcrafted and CNN-derived static features.

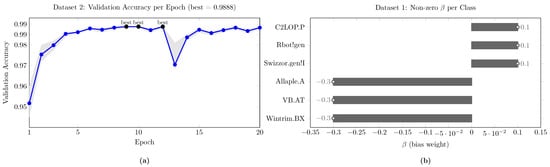

Figure 1a shows the validation accuracy curve for the Fusion Malware dataset, highlighting the performance of the multimodal fusion model. The accuracy rises from 95.17% at epoch 1 to 98.5% by epoch 4, indicating effective learning from static and visual data. After epoch 4, the accuracy stabilizes between 97.5% and 99%. The model achieves peaks of 98.88% at epochs 9, 10, and 12, demonstrating its robustness. Although there is a brief dip to 97.04% at epoch 13, performance quickly recovers, showing resilience to fluctuations. Overall, the model maintains high performance near the 99% threshold throughout training. Overall, this figure emphasizes that the hybrid ConvNeXt-Tiny fusion architecture achieves both rapid convergence and stable long-term validation accuracy on the Fusion Malware dataset.

Figure 1.

(a) The epoch-wise validation accuracy curve for the Fusion Malware dataset. (b) The per-class logit biases learned on the validation set for the Malimg snapshot-ensemble.

Figure 1b visualizes the per-class logit biases learned on the validation set for the Malimg snapshot-ensemble. Three families receive negative corrections (Allaple.A, VB.AT, and Wintrim.BX at ), indicating a tendency of the ensemble to over-score these classes before calibration; three receive positive corrections (Swizzor.gen!I, Rbot!gen, and C2LOP.P at ), compensating under-scoring or ambiguity. The magnitudes are intentionally small (), which preserves the ensemble’s ranking while gently shifting the decision boundary for borderline samples. This low-amplitude, class-specific adjustment increased validation accuracy to 0.9967 and carried through to the test set (final accuracy 0.9969), confirming that the calibration is corrective rather than distortive.

From a modeling perspective, adding is equivalent to a class-conditional logit offset, similar to a lightweight prior/threshold correction. The negative offsets on large, visually distinctive families (e.g., Allaple.A) down-weight occasional overconfidence that can steal predictions from nearby families; conversely, the positive offsets on harder families (e.g., Swizzor.gen!I) counter residual confusion (noted in its lower precision pre-calibration) and help recover recall without retraining. Because is validated by a simple grid search, the risk of overfitting is limited, and the effect is interpretable: it explicitly encodes which families benefited from post hoc adjustment and by how much—useful for analyst-facing attribution reports.

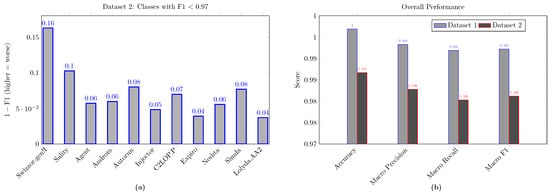

Figure 2a shows the 1-F1 scores for the eleven weakest families in the Fusion Malware dataset, with lower scores being better. Swizzor.gen!I has the highest score of 1-F1 = 0.1628, mainly due to its low precision of 0.7826 despite a decent recall of 0.90. This indicates that similar families are likely causing false positives. Sality (0.1026) and Autorun (0.0800) may reflect their broad categories and significant variation within the same class, which can blur their classification boundaries when using cross-attention fusion. Mid-tier gaps such as C2LOP.P (), Androm (), Agent (), Neshta (), and Injector () indicate mixed error profiles—moderate precision loss for some (e.g., Injector 0.9718 precision and 0.9324 recall) and mild recall under-shoot for others—consistent with families that share texture/structure motifs in their image encodings. Expiro () and Lolyda.AA2 () are close to the accuracy frontier but need more examples or targeted augmentation to reach the near-perfect cluster. Overall, the chart complements the headline scores by localizing where class ambiguity, imbalance (e.g., Simda; n = 7), and polymorphism most affect performance; these are prime candidates for class-aware augmentation (texture-preserving rotations/crops; histogram perturbations), focal/CB (class-balanced) loss to reweight hard/rare cases, and optional, small per-class calibration (threshold/bias) analogous to the Malimg bias study, if operational precision on these families is mission-critical. The Malimg bias analysis showed that tiny, interpretable logit offsets () improved validation and carried to test without distorting the ensemble’s ranking. A similar, tightly regularized per-class calibration could be explored for Fusion’s hardest families—especially Swizzor.gen!I and Sality—to nudge decision thresholds posttraining while preserving overall calibration. This provides a lightweight alternative to full retraining when operational constraints favor quick, auditable adjustments.

Figure 2.

(a) The 1-F1 for the eleven weakest families on the Fusion Malware dataset. (b) The overall performance of the proposed method on two datasets in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

Figure 2b contrasts dataset 1 (Malimg) with dataset 2 (Fusion) on four metrics and reveals a consistent 1% absolute performance gap favoring Malimg: accuracy vs. , Macro Precision vs. , Macro Recall vs. , and macro F1 vs. . This pattern indicates that, beyond overall accuracy, the class-averaged precision/recall balance is uniformly stronger on Malimg, consistent with its smaller family set and the use of snapshot-ensembling plus bias calibration. Conversely, Fusion’s larger label space and higher heterogeneity create more opportunities for per-class degradation, which pulls down the macro averages. Notably, on both datasets the Weighted-F1 (Malimg ; Fusion ) tracks overall accuracy closely, implying that large/support-rich families dominate the global score while macro metrics remain sensitive to smaller or harder families—an effect more pronounced in Fusion. The macro gap on Fusion is well explained by the error-hotspot analysis, where a handful of families (e.g., Swizzor.gen!I, Sality, and Autorun) exhibit notably lower F1 than the cohort median. The concentration of errors suggests that targeted remedies—like class-aware augmentation, calibrated thresholds, or small per-class logit adjustments—could significantly improve macro metrics without greatly altering strong model families. For Malimg, small per-class biases (with ()) enhanced validation performance and maintained ranking, providing a low-risk method for adjusting decision thresholds. Given Fusion’s macro shortfall is driven by a few outliers, the same tactic—applied sparingly to those classes—could close part of the macro gap without retraining or full ensembling (and can be combined with post hoc threshold tuning for precision/recall trade-offs).

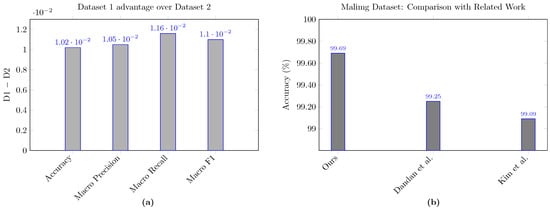

Figure 3a visualizes the absolute margin by which our method did very well on Malimg compared to Fusion across four evaluation metrics. The gaps are uniformly about one percentage point, with the largest on Macro Recall (), followed by macro F1 (), Macro Precision (), and accuracy (). The prominence of the recall gap indicates that Fusion’s harder/rarer families depress class-averaged sensitivity more than they affect global accuracy, consistent with the error-hotspot analysis and the larger label space/heterogeneity in the Fusion Malware dataset. Methodologically, the margin also reflects pipeline differences: Malimg benefits from snapshot ensembling, eight-view TTA, and per-class bias calibration, whereas Fusion uses a single best checkpoint without post hoc class-wise offsets; this combination plausibly elevates Malimg’s macro metrics, especially recall.

Figure 3.

(a) The absolute margin by which our method did very well on Malimg compared to Fusion across four evaluation metrics. (b) shows the superior performance of the proposed method on the Malimg dataset relative to recent related work (i.e., Dandan et al. [26] and Kim et al. [23]).

Discussion

The results demonstrate that these two mechanisms (i.e., calibration and multimodal fusion) are effective in detecting malware and classifying its families. On one hand, the integration of both bias learning and snapshot ensembling yields almost perfect accuracy in the Malimg dataset. On the other hand, the incorporation of static features and visual representations using ConvNetXt-Tiny embedding showed robust generalization with a large number of malware families (i.e., 59 malware families in the Fusion malware dataset). Nevertheless, the model’s performance decreased on the second dataset due to the increased number of families with a small number of visually ambiguous samples, indicating that there is room for improvement through the use of few-shot learning or data augmentation.

The Fusion Malware dataset shows notable class imbalance and polymorphic behavior, with some families featuring very few samples or sharing traits with other families. Instead of typical oversampling, which can distort the true distribution, we use label smoothing and MixUp augmentation to reduce overconfidence and encourage the model to develop generalized decision boundaries. These regularization methods and multimodal fusion have enhanced training stability and diminished overfitting in prevalent families. Future research may investigate focal loss and dynamic reweighting methods to tackle imbalances, particularly in less common polymorphic families.

The comparison shown in Figure 3b demonstrates that the proposed method outperforms recent multimodal and unimodal, i.e., image-based, approaches using the Malimg dataset. Our model achieves an accuracy of 99.69%, outperforming Dandan et al. [26] (99.25%) and Kim et al. [23] (99.09%). While the accuracy differences between the methods may seem numerically slight, this difference becomes immense when considering the high performance required for malware family classification approaches. Thus, even a slight improvement means correctly detecting a large number of malware in real-world scenarios. This advantage highlights the effectiveness of our multimodal fusion and bias calibration strategies in minimizing residual errors and achieving exceptional performance. The multimodal framework is designed for practical use, capable of processing approximately 250 images per second with a batch size of 64 on an NVIDIA T4 GPU, using less than 1.5 GB of memory. It is suitable for offline and near-real-time detection workflows. The snapshot-ensemble approach retains ensemble-level robustness without the computational overhead of training or storing multiple networks.

Figure 4 illustrates Grad-CAM overlays for three representative samples—Allaple.A, Swizzor.gen!I, and Lolyda.AA1—demonstrating how the proposed model attends to distinctive structural regions when making classification decisions. In the Allaple.A example, the activation is focused on the core image pattern, showing that the model uses key regions for accurate predictions. The Swizzor.gen!I heatmap exhibits broader attention across horizontal bands, reflecting the family’s polymorphic variability while still achieving correct classification. For Lolyda.AA1, attention centers on two symmetric hotspots along the vertical axis, highlighting the unique structural cues that differentiate this family. The illustration shows how cross-attention fusion identifies important structural patterns and reduces irrelevant background noise, allowing the model to focus on crucial aspects of malware. In the future, we will examine other explainable AI (XAI) methods, like shapley additive explanations (SHAP), to increase trust and transparency for data analysts.

Figure 4.

Grad-CAM overlays for three representative samples—demonstrating how the proposed model attends to distinctive structural regions when making classification decisions.

The proposed architecture can adapt to evolving threats by leveraging its multimodal representation space. Since the model jointly learns statistical, structural, and visual embeddings, it can generalize to new malware families with similar underlying characteristics. Moreover, the snapshot-ensemble technique does not depend on a specific architecture; thus, the same principle can be applied to other backbones such as Vision Transformers or EfficientNets. This flexibility supports continual learning and makes the approach more suitable for real-world threat intelligence systems, where rapid adaptation to emerging malware patterns is critical. This flexibility could further improve generalization to highly obfuscated malware, albeit at a higher computational cost.

5. Conclusions

We present a multimodal approach for classifying malware families using static features and grayscale images with a ConvNeXt-tiny backbone and a cross-attention layer. Our method achieved 99.69% accuracy on the Malimg dataset through eight-view test-time augmentation, per-class calibration, and snapshot ensembling and 98.67% accuracy with a macro F1 score of 0.9812 on the Fusion Malware dataset using a single-checkpoint model. Despite these results, challenges remain with malware families that have low support or polymorphic behavior. The Malimg dataset outperformed Fusion Malware in accuracy and other metrics due to effective calibration strategies. Our bias calibration study showed that small logit offsets can improve results without retraining. Classes in the Fusion Malware dataset with F1 scores below 0.97 are targeted for future refinement using methods like class-aware augmentation and lightweight calibration. This research demonstrates the effectiveness of multimodal fusion and post hoc calibration in malware attribution, providing a framework for broader application in diverse datasets.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available, i.e., Malimg dataset in FigShare at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/MalImg_dataset_zip/24189882?file=42443904 (accessed on 28 October 2025) and Fusion Malware dataset in Kaggle at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/marcesalas/fusion-dataset-59-malware-families-in-png-format (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

To support reproducibility, this section provides detailed hyperparameters and implementation notes. The entire pipeline was implemented in Python (version 3.10) using PyTorch (version 2.3.0) and the Timm vision library. All datasets used in this study—Malimg and Fusion Malware—are publicly available. The training procedures follow standard deep learning practices and can be replicated using the specifications listed in Table A1.

Table A1.

Training hyperparameters used in the multimodal fusion experiments.

Table A1.

Training hyperparameters used in the multimodal fusion experiments.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning rate schedule | Cosine Annealing with Warm Restarts |

| Initial learning rate | |

| Batch size | 64 (Malimg), 128 (Fusion Malware) |

| Epochs | 15 (Malimg), 20 (Fusion Malware) |

| Label smoothing | |

| MixUp parameter () | 1.0 (Fusion Malware only) |

| Weight decay | |

| Backbone architecture | ConvNeXt-Tiny |

| Attention heads | 8 |

| Dropout rate | 0.3 (classifier head) |

| Hardware | NVIDIA T4 GPU, 16 GB VRAM |

The complete implementation follows reproducible design principles: fixed random seeds, deterministic cuDNN settings, and explicit version control for all libraries (PyTorch 2.3, Timm 1.0). These details ensure that the reported performance can be reproduced independently using standard hardware and software configurations.

References

- Qureshi, S.U.; He, J.; Tunio, S.; Zhu, N.; Nazir, A.; Wajahat, A.; Ullah, F.; Wadud, A. Systematic review of deep learning solutions for malware detection and forensic analysis in IoT. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Wang, J.; Fang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, D.; Ge, W. A survey of strategy-driven evasion methods for PE malware: Transformation, concealment, and attack. Comput. Secur. 2024, 137, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponis, G.; Radoglou-Grammatikis, P.; Lagkas, T.; Ouzounidis, S.; Zevgara, M.; Moscholios, I.; Goudos, S.; Sarigiannidis, P. Generating full-stack 5G security datasets: IP-layer and core network persistent PDU session attacks. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2023, 171, 154913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, M.G.; Ahmed, M.; Janicke, H. Malware Detection with Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrios, S.; Leiva, D.; Olivares, B.; Allende-Cid, H.; Hermosilla, P. Systematic Review: Malware Detection and Classification in Cybersecurity. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazim, S.; Alam, M.M.; Rizvi, S.; Mustapha, J.C.; Hussain, S.S.; Su’ud, M.M. Multimodal malware classification using proposed ensemble deep neural network framework. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahali, A.; Lashkari, A.H.; Kaur, G.; Taheri, L.; Gagnon, F.; Massicotte, F. DIDroid: Android Malware Classification and Characterization Using Deep Image Learning. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Communication and Network Security (ICCNS2020), Tokyo, Japan, 27–29 November 2020; pp. 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, D.S.; Li, B.; Kaur, G.; Lashkari, A.H.; Gagnon, F.; Massicotte, F. EntropLyzer: Android Malware Classification and Characterization Using Entropy Analysis of Dynamic Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2021 Reconciling Data Analytics, Automation, Privacy, and Security: A Big Data Challenge (RDAAPS), Hamilton, ON, Canada, 18–19 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkir, A.S.; Cankaya, A.O.; Aydos, M. Utilization and Comparision of Convolutional Neural Networks in Malware Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 27th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Sivas, Turkey, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, L.; Karthikeyan, S.; Jacob, G.; Manjunath, B.S. Malware images: Visualization and automatic classification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Visualization for Cyber Security (VizSec ’11), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20 July 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Otaibi, S.A.; Tian, Z. Imbalanced Malware Family Classification Using Multimodal Fusion and Weight Self-Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 7642–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, R.; Radu, M.; Feuerstein, C.; Yom-Tov, E.; Ahmadi, M. Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.10135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, I.J.; Carley, K.M. Analysis of Malware Communities Using Multi-Modal Features. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 77435–77448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, J.; Berlin, K. Deep neural network based malware detection using two dimensional binary program features. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE), Fajardo, PR, USA, 20–22 October 2015; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Stamp, M. Multimodal Techniques for Malware Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.10956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappa, A.; Rafique, M.Z.; Caballero, J. The MALICIA dataset: Identification and analysis of drive-by download operations. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2015, 14, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.J.; Hendrawan, R.B.; Juhana, T.; Musashi, Y. MIDALF—multimodal image and audio late fusion for malware detection. EURASIP J. Info. Secur. 2025, 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johny, J.A.; Asmitha, K.A.; Vinod, P.; Radhamani, G.; Rehiman, K.R.; Conti, M. Deep learning fusion for effective malware detection: Leveraging visual features. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, E.; Alam, M.; Glandon, A.; Iftekharuddin, K. End-to-end Multimodel Deep Learning for Malware Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-I.; Kang, M.; Cho, S.-J.; Choi, S.-I. Efficient Deep Learning Network With Multi-Streams for Android Malware Family Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 5518–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzenbarth, M.; Freiling, F.; Echtler, F.; Schreck, T.; Hoffmann, J. Mobile-sandbox: Having a deeper look into android applications. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’13), Coimbra, Portugal, 18–23 March 2013; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arp, D.; Spreitzenbarth, M.; Hübner, M.; Gascon, H.; Rieck, K. Drebin: Efficient and Explainable Detection of Android Malware in Your Pocket. In Proceedings of the the 2014 Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Paik, J.-Y.; Cho, E.-S. Attention-Based Cross-Modal CNN Using Non-Disassembled Files for Malware Classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 22889–22903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, S. Multimodal Dual-Embedding Networks for Malware Open-Set Recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 4545–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyrum, S. Anderson and Phil Roth, EMBER: An Open Dataset for Training Static PE Malware Machine Learning Models. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.04637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Song, Y.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, Y. IMCMK-CNN: A lightweight convolutional neural network with Multi-scale Kernels for Image-based Malware Classification. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 111, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.03545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol. Rev. 1958, 65, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Li, Y.; Pleiss, G.; Liu, Z.; Hopcroft, J.E.; Weinberger, K.Q. Snapshot Ensembles: Train 1, get M for free. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.00109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).