Abstract

By analyzing the coverage model of cameras, a surveillance camera network model based on road vertex coverage is proposed, and an optimized deployment method for cameras based on the Minimum Weighted Vertex Cover (MWVC) model is given. The greedy algorithm is used to solve the MWVC problem, where vertex weights are defined based on adjacency degree to guide the selection process. The results from large-scale simulation experiments (10,000 runs) show that compared to the traditional Minimum Vertex Cover (MVC) model, this method reduces the number of monitoring points by approximately 15 on average (a relative reduction of about 2%). In a practical case study of a township in Wuwei City, Gansu Province, this method optimized the number of required monitoring poles from 62 to 33 (a 46.8% reduction) and the number of cameras from 196 to 98 (a 50% reduction), while ensuring 100% road coverage. This research provides a practical theoretical basis and decision-making support for the low-cost, high-efficiency layout of surveillance equipment in smart city infrastructure.

1. Introduction

The continuous advancement of video surveillance technology has brought revolutionary changes to fields such as intelligent transportation [1] and public security [2]. By monitoring road conditions and vehicle driving status in real time, these systems can promptly identify traffic congestion, violations, and accidents [3], thereby enhancing traffic flow efficiency. The video surveillance technology can quickly identify criminal suspects through facial recognition technology [4] and achieve round-the-clock monitoring and real-time early-warnings of important places. Reasonable installation of video surveillance can effectively prevent all kinds of potential safety hazards [5] and criminal activities and improve the level of social security. However, the traditional installation and layout of surveillance cameras mainly rely on the experience of engineering personnel. Unreasonable surveillance layout can lead to problems such as coverage blind spots [6], coverage overlap [7], and missing fields of view, ultimately resulting in suboptimal resource utilization.

To address these limitations, significant research efforts have been directed towards optimizing surveillance site selection [8] and coverage [9]. These efforts can be broadly categorized into qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative approaches, such as Ramanathan [10] evaluated the influencing factors of the environment on monitoring site selection by using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), and discussed the flexibility, main shortcomings and improvement methods of AHP. Ziemann et al. [11] assessed if the comparison of several syndromic surveillance systems through Qualitative Comparative Analysis helps to evaluate performance and identify key success factors. However, this qualitative analysis method has the problem that the coverage of surveillance videos cannot be guaranteed, which is prone to cause waste of resources and failure to meet the standard coverage rate.

On the quantitative front, many camera placement problems have been effectively formulated as combinatorial optimization problems. Kritter et al. [12] combined the relationship between the Optimal Camera Placement problem (OCP) and the set Covering problem (SCP), providing a theoretical basis and inspiration for the camera placement problems involved in practical applications. Sumi et al. [13] proposed the Alternating Global Greedy (AGG) algorithm and the Greedy Grid Voting (GGV) algorithm to determine the optimal camera configuration for multi-camera networks in order to maximize coverage and reduce overlap. Tran [14] proposes a voxel-based site coverage and overlapping analysis for camera allocation planning in parametric BIM environments, called the PBA approach. Beyond camera placement, optimization concepts are also prevalent in sensor network deployment. Zou et al. [15] proposed the Virtual Force Algorithm (VFA) as a sensor deployment strategy to improve the coverage of cluster-based distributed sensor networks. Other relevant optimization techniques include the theory of the observation field and the MAGA algorithm used by Wang and Dou [16] for monitoring point positioning, and the use of Robust Particle Swarm Optimization (RPSO) by He et al. [17] for video encoding to reduce redundancy. Recent trends also explore intelligent optimization at the edge [9] and hybrid or AI-based methods like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) for related coverage problems.

Despite these advancements, a notable gap persists when applying these methods specifically to large-scale urban road network surveillance. While graph theory models, particularly the Minimum Vertex Cover (MVC) problem, offer a natural fit for representing roads as graphs (vertices as intersections, edges as road segments), standard MVC solutions often treat all vertices as homogeneous. This overlooks the varying topological importance of different intersections within the complex structure of a real road network. Therefore, although using the standard MVC algorithm would generate a set of camera positions that cover all the roads, it is not the most cost-effective approach. The inherent simplicity of a basic greedy algorithm for MVC can lead to blindness in selection, especially when many vertices have similar degrees—a common scenario in road networks where intersection degrees often cluster around 3 or 4. Furthermore, while advanced metaheuristics (e.g., GA, ILP) can potentially find better solutions, their high computational complexity often makes them less practical for the rapid planning required in large-scale urban deployments.

To bridge this gap, this paper proposes a novel monitoring layout optimization method based on a Minimum Weighted Vertex Cover (MWVC) model, specifically designed for the characteristics of traffic road networks. The innovative aspect lies in integrating the vertex weighting mechanism into the MVC framework, where the weights are derived from the adjacency degree of an intersection. This guides a greedy algorithm towards a more intelligent and efficient selection of monitoring points.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We propose a Minimum Weighted Vertex Cover (MWVC) model for road network surveillance, where vertex weights are dynamically calculated based on their adjacency degree, effectively incorporating local topological significance into the optimization objective.

- (2)

- We develop an efficient greedy algorithm enhanced by the vertex weighting scheme to solve the MWVC problem. This approach maintains the computational efficiency crucial for large-scale urban applications while achieving superior performance compared to the unweighted greedy approach.

- (3)

- We demonstrate the effectiveness and practicality of our proposed model through extensive large-scale simulations (10,000 runs) and a detailed real-world case study in Wuwei City, China. The results consistently show a reduction in the number of required monitoring points compared to the unweighted MVC baseline, leading to significant cost savings.

2. Modeling of Monitoring Layout Problem

2.1. Camera Perception Model

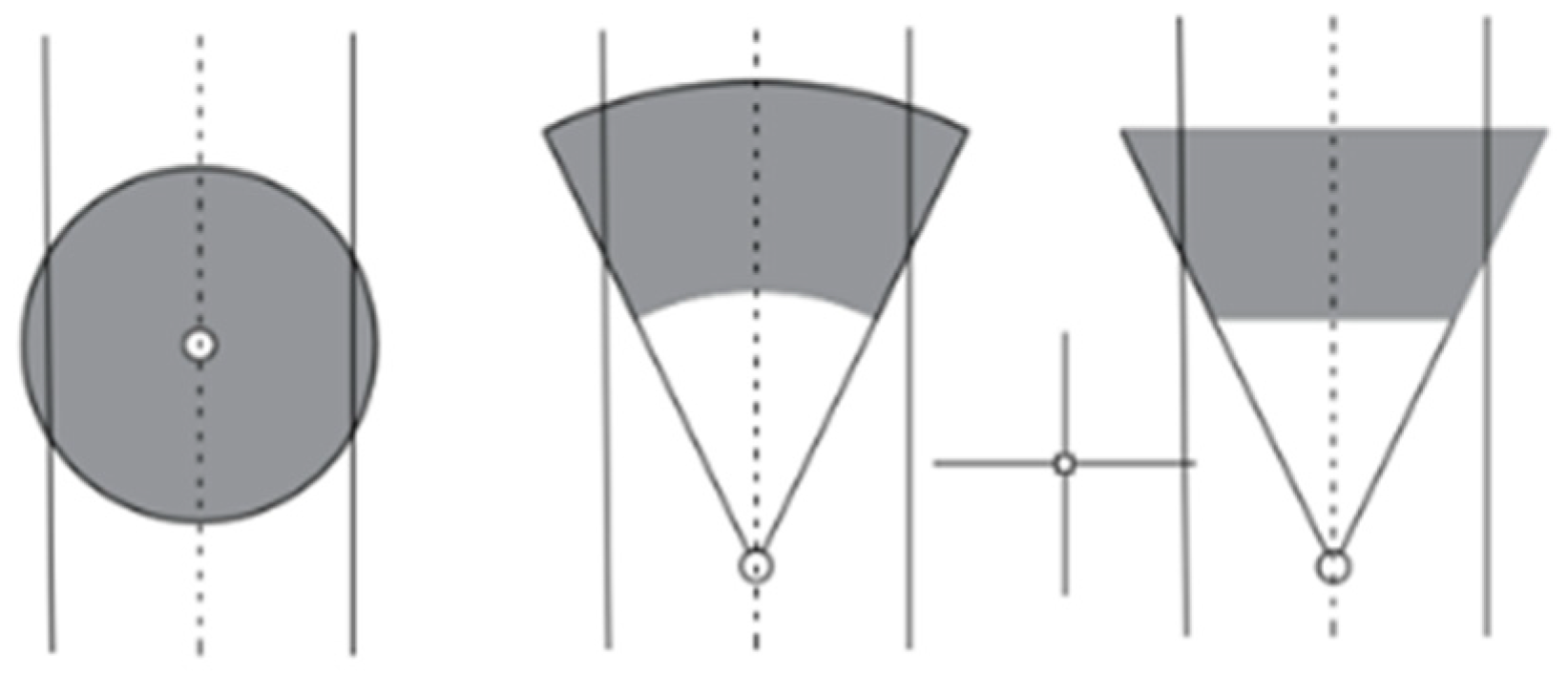

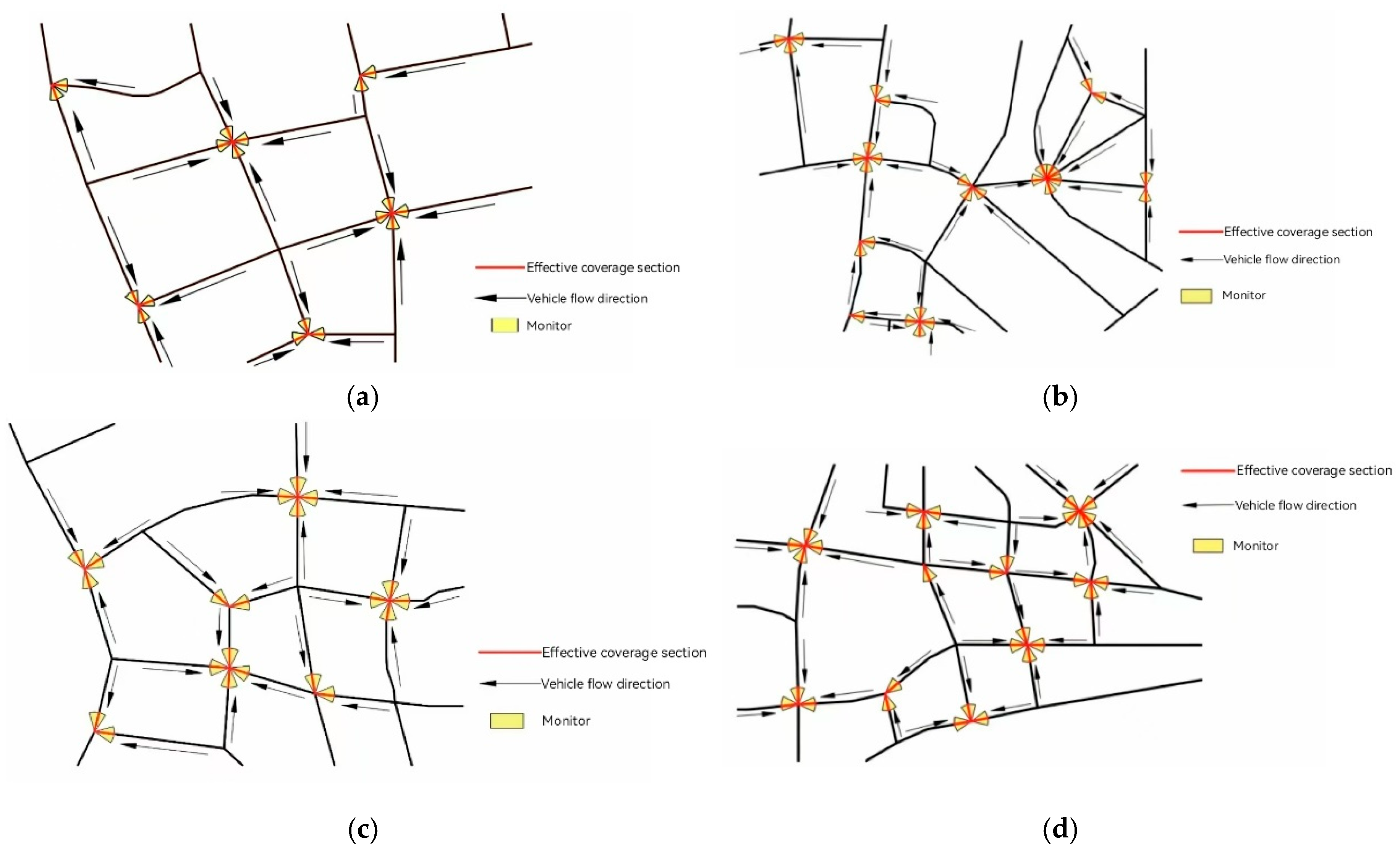

Typically, a camera is deployed in 3D space to monitor the 2D plane, and the result of the coverage layout is illustrated in Figure 1. The coverage of the hemispherical camera can be expressed as a circle, and the radius of the circle represents the working range of the camera. The 2D plane monitored by the gun-type camera in 3D space can be expressed as a trapezoid or annular sector. The two-dimensional directional sensing model refers to the sensing model composed of a sensor node as the center, a certain sensing radius, and a fan-shaped area of the start and end angles. The directional sensing model (sector/trapezoid) was chosen because it aligns well with real-world camera deployment at road intersections and facilitates the transformation of the road network into a graph structure, which is essential for applying vertex cover models. Its mathematical model can be abstracted as a quadruple represented by .

Figure 1.

Camera perception model.

2.2. Monitoring Layout Model

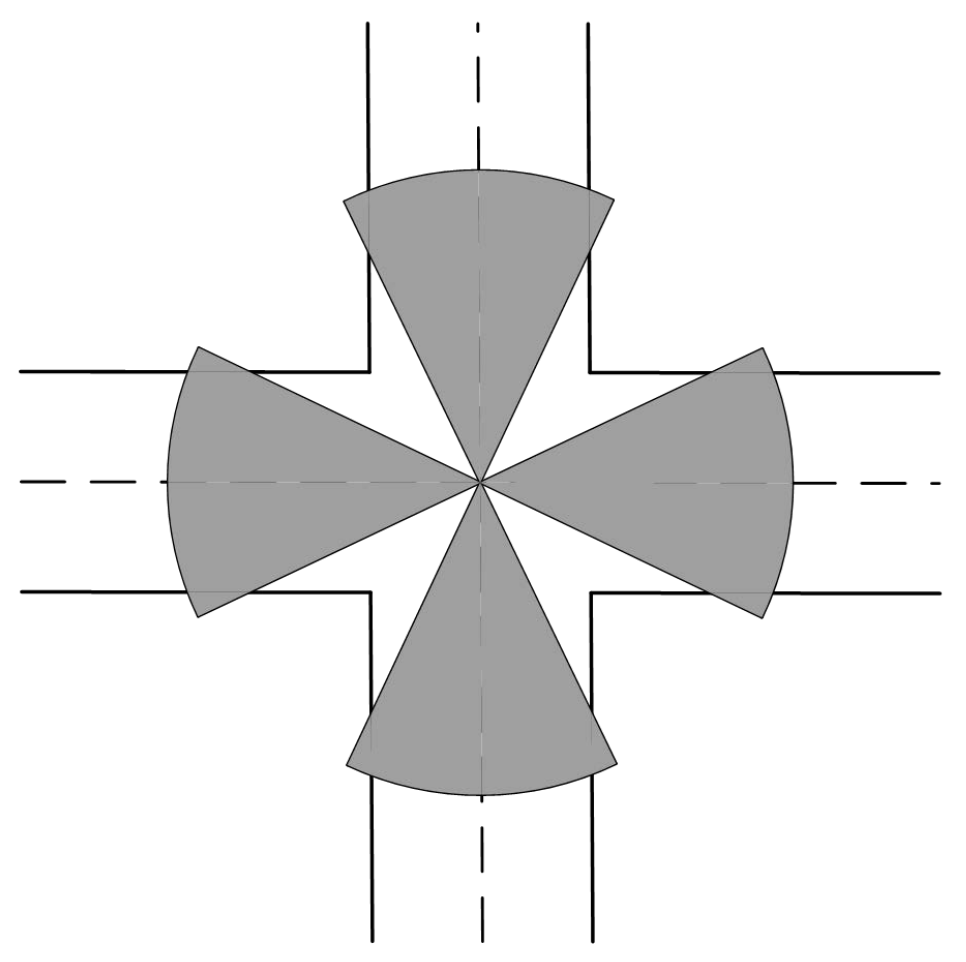

In practical applications, surveillance devices are often installed along each road at road intersections to effectively cover the entire monitoring area. This layout can effectively monitor traffic flow, vehicle speed and traffic incidents, and improve the efficiency and accuracy of traffic management, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Road vertex surveillance deployment model diagram.

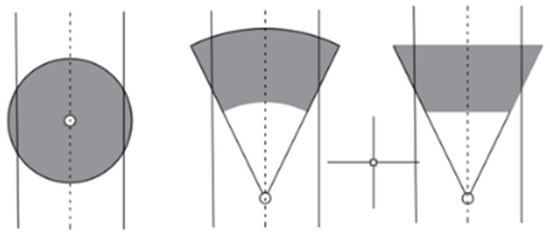

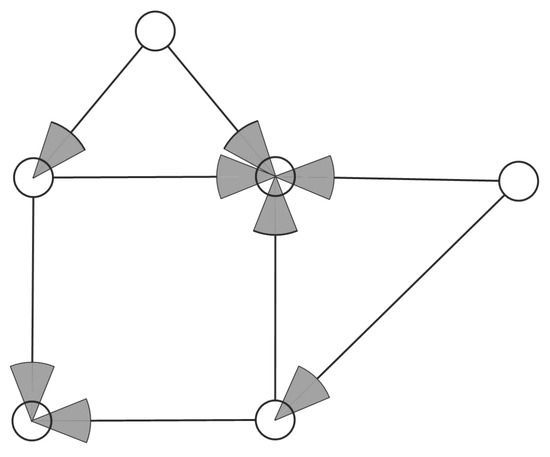

In order to analyze the monitoring coverage of the entire monitoring area more comprehensively and easily, the intersection is regarded as the vertex of the road network, and each road is regarded as an edge connecting different vertices. Therefore, the entire monitoring area can be transformed into an undirected graph structure. As shown in Figure 3, surveillance devices are installed along each edge, respectively. When vehicles and pedestrians pass through the intersection, they can be monitored and recorded in real time.

Figure 3.

Fully deployed monitoring deployment model.

By transforming the research area into an undirected graph and converting the camera deployment problem into a minimum vertex coverage problem, the problem of cost and benefit balance in the monitoring layout can be effectively solved. The minimum vertex cover set, which is the smallest set of vertices that can cover all edges of the graph, can be obtained as shown in Figure 4. By installing a camera at the road intersection focused by the minimum vertex set, the coverage of the entire monitoring area can be effectively ensured, and the input cost of the monitoring equipment can be saved to a certain extent.

Figure 4.

Optimised deployment of road apex monitoring models.

3. Monitoring Layout Model Solution

3.1. Minimum Vertex Cover Model Based on Greedy Algorithm and Its Solution

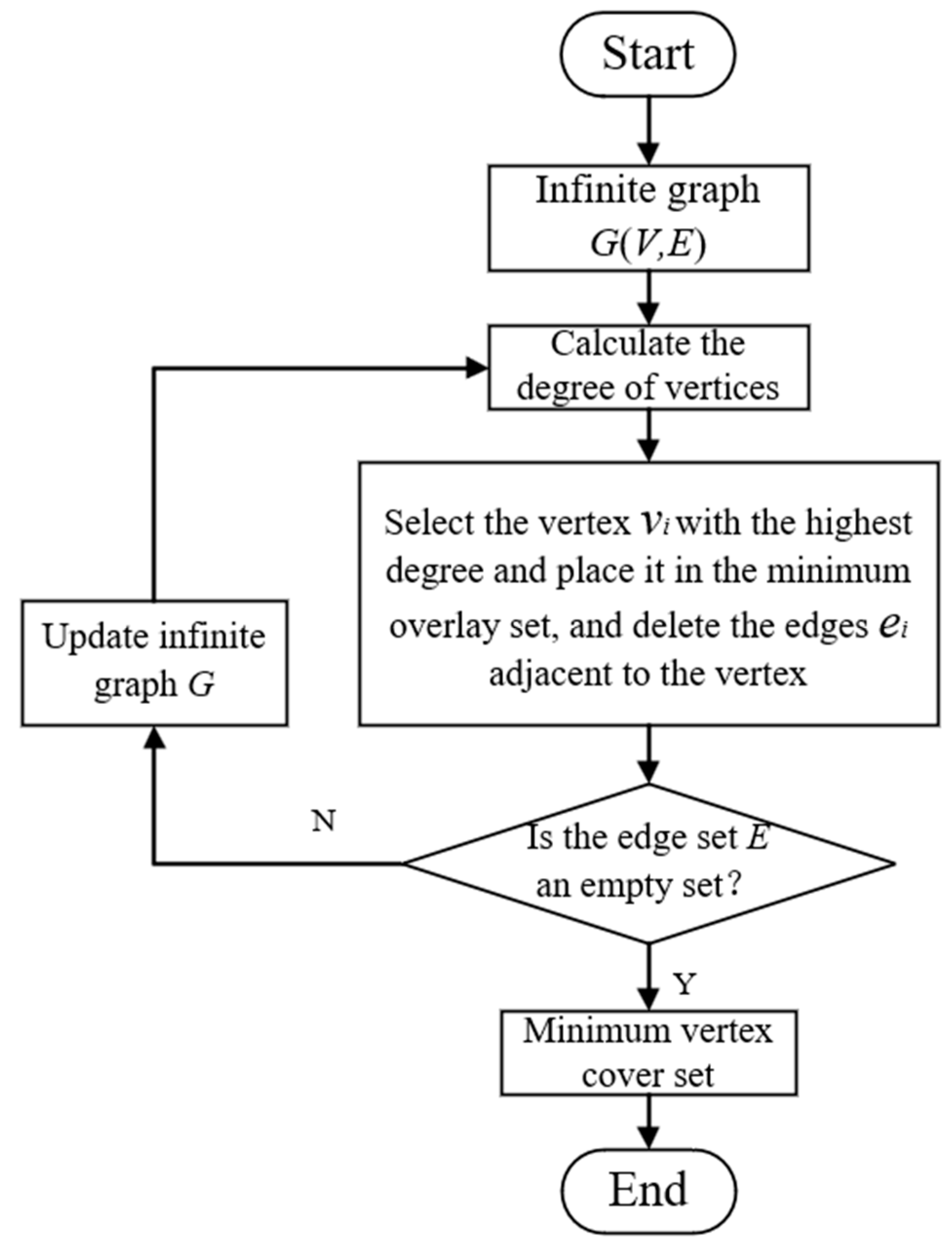

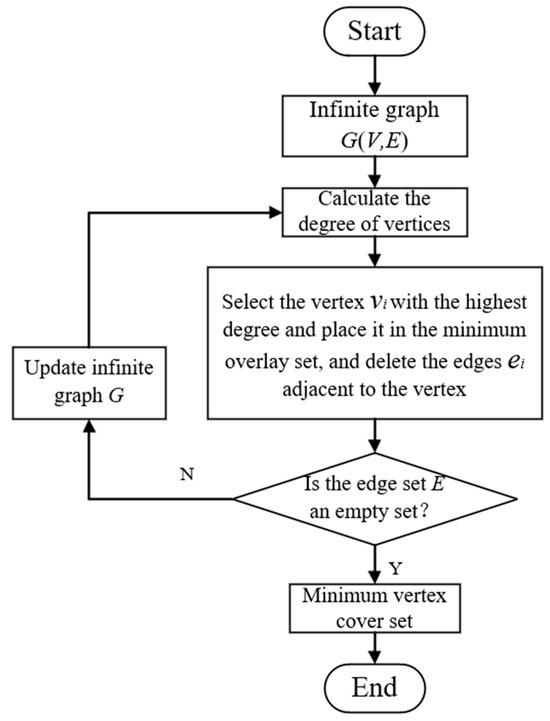

Based on the road vertex monitoring deployment model and the greedy algorithm, the main process of solving the road vertex monitoring deployment model is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart for solving the minimum vertex cover model.

The pseudo-code for solving the minimum vertex coverage model is as follows:

| Input: A symmetric matrix Output: A set of selected row indices

|

The specific steps of this algorithm are as follows:

(1) Undirected graph datafication: Transform an undirected graph into a symmetric matrix representation. The symmetric matrix representation can be expressed as:

where . is the number of nodes of the research object. When is 0, the two nodes represented by are not connected, and when is 1, the two nodes represented by are connected.

(2) Calculation of vertex degree: The undirected graph can be expressed as:

where represents each vertex on the road, and represents the edge connecting each vertex.

Suppose is the degree of . The degree of a vertex can be expressed as:

(3) Local optimal solution selection: For m vertices, the vertex with the maximum degree is selected first, and the edge connected with the verte is deleted in the undirected graph G, that is, the vertex is required.

(4) Ending criterion: Check whether the edge set is an empty set. If it is an empty set, the algorithm stops and outputs the search results (the vertex cover set). If it is not an empty set, update the undirected graph, and repeat steps (1), (2), (3) until the edge set is an empty set, and output the search result at this time, that is, the minimum vertex cover set.

However, in the process of road vertex monitoring layout optimization, the degree values of multiple nodes are similar (generally speaking, the degree values of most nodes in the traffic road network graph are 3 or 4), which may lead to a certain blindness in the greedy algorithm in finding the minimum vertex cover set. This blindness may affect the optimality of the coverage set and may cause the edge nodes to be omitted and not given priority. Therefore, aiming at the specific needs of traffic road network monitoring, this paper introduces a weight mechanism to improve the minimum vertex coverage model, and proposes a minimum weighted vertex coverage model based on greedy algorithm.

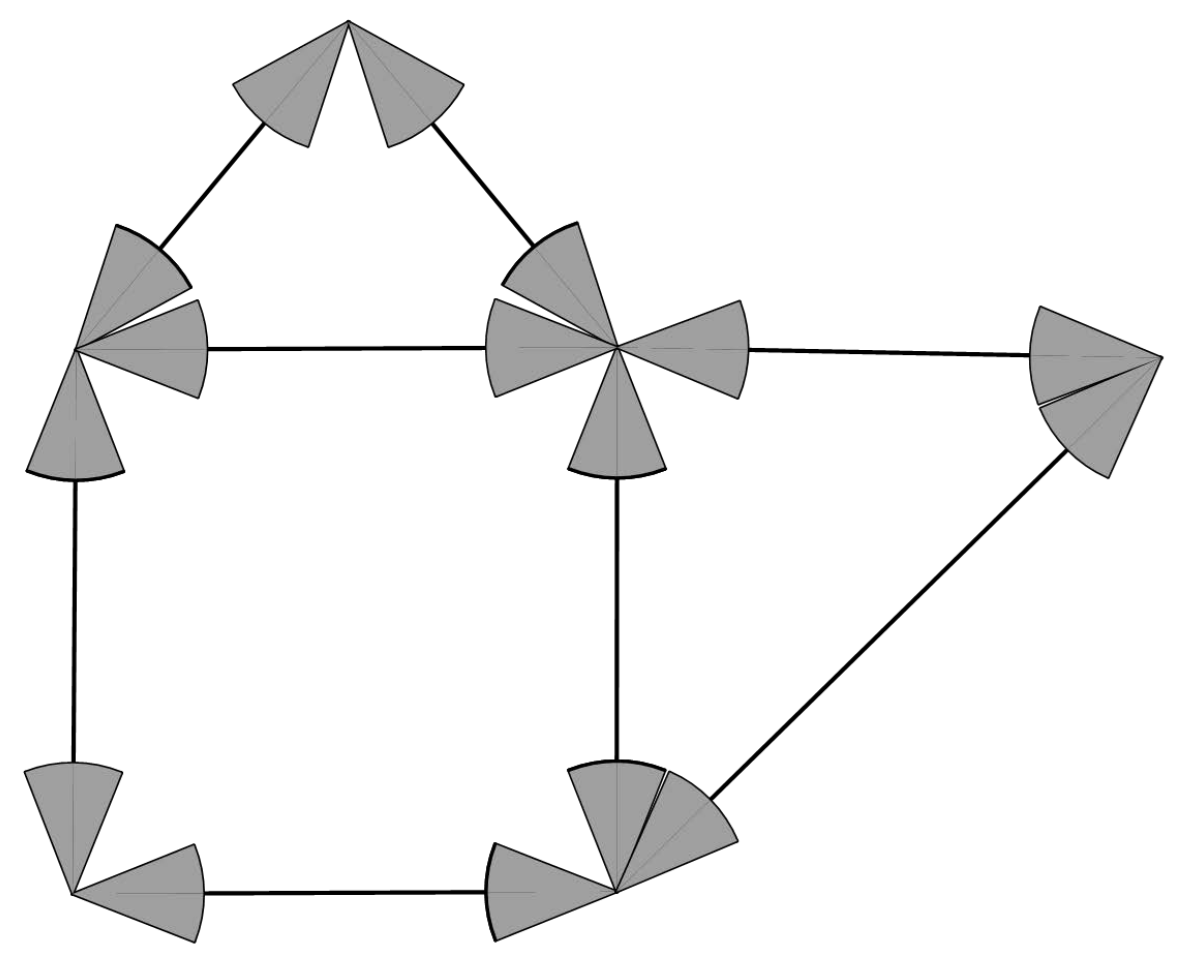

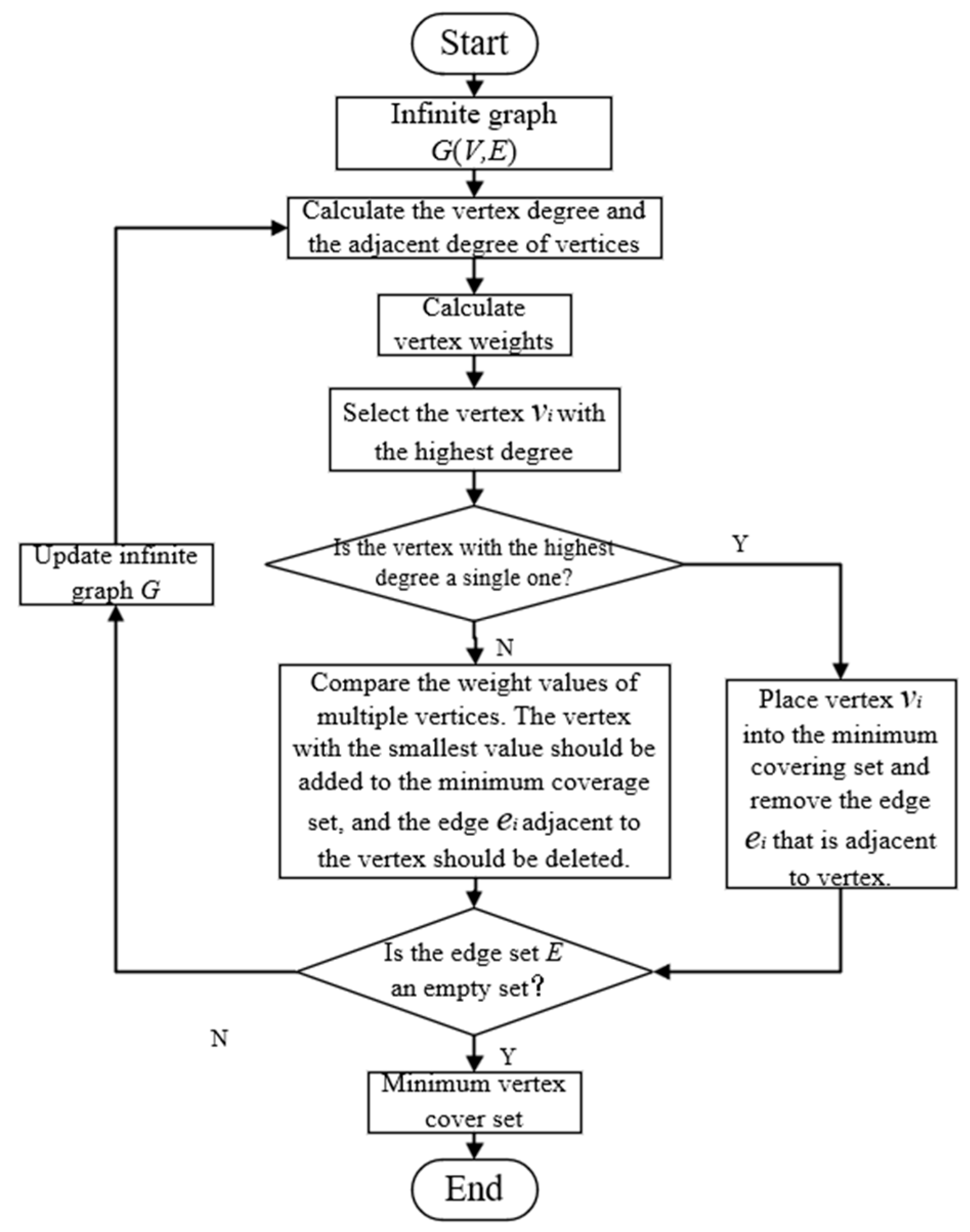

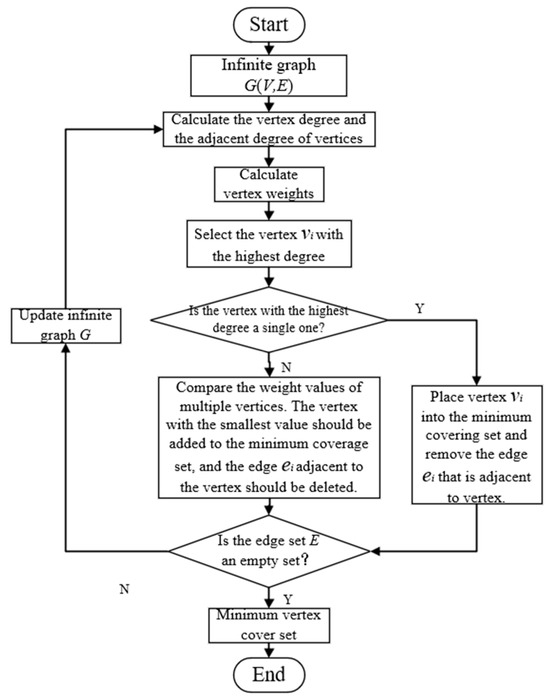

3.2. Minimum Weighted Vertex Cover Model Based on Greedy Algorithm and Its Solution

The minimum weighted vertex cover model is based on the minimum vertex cover and introduces a weight mechanism to assign different weights to each node. By comparing the weight values of the vertices, the blindness of vertex selection can be effectively reduced, so that the number of vertices in the minimum vertex cover set is optimized. The solution process of the minimum weighted vertex cover model based on the greedy algorithm is shown in Figure 6. The undirected graph datamation and vertex degree calculation process are the same as those in the solution process of the minimum vertex cover model based on the greedy algorithm. The difference is that the vertex adjacency degree and weight need to be calculated.

Figure 6.

Technical framework for solving minimum weighted vertex coverage models.

Definition of . is the degree of . The adjacency degree is the sum of the degree of vertex and the degrees of all other adjacent vertices. The adjacency degree is expressed as:

Then the weights of the vertices are expressed as

The logic behind this weight design is as follows: the algorithm prioritizes selecting the vertex with the highest adjacency degree, , to achieve the greatest immediate coverage gain. When ties occur, the vertex with the smallest weight is chosen among them. This is because a vertex with a small weight indicates that the overall connectivity of itself and its neighborhood is relatively low, positioning it as a ‘terminal’ point within the local network. Prioritizing the coverage of such vertices preserves those with better connectivity and greater potential (i.e., vertices with higher weights) for later stages of the covering process, which may ultimately lead to a smaller vertex cover set globally.

When selecting the local optimal solution, the vertices with the highest value in the graph are first selected as candidate vertices. If there are multiple vertices with the same highest value, the weights of these vertices are compared, and the vertices with the smallest weight value are preferentially selected and added to the local optimal solution set. After the vertex is selected, the vertex and all edges connected to it are removed from the graph to ensure that these edges are covered by at least one selected vertex. Then, the vertices with the highest degree value are re-selected in the remaining graphs and selected according to the principle of weight priority. This process is iterated until all edges are covered by at least one selected vertex.

The pseudo-code for solving the minimum weighted vertex coverage model is as follows:

| Input: Symmetric matrix Output: Selected set of row indices

|

3.3. Comparative Evaluation of the Two Models

In order to verify the performance of the improved monitoring layout model, a bidirectional graph containing 1000 nodes was generated in the experiment to simulate the real outdoor traffic road. According to the actual situation of the road intersection, the degree of each node was set to change between 3 and 6, and a total of 10,000 experiments were performed. In each round of the experiment, the results are classified into three cases based on the size differences among the vertex cover sets:

(1) When the vertex cover set of the weighted model has n fewer vertices than that of the non-weighted model, it is considered that the weighted model performs better, and the n value is recorded for subsequent calculations.

(2) If the results of the two models are the same, they are regarded as equivalent.

(3) If the weighted model has n more vertices than the unweighted model, it is considered to have poorer performance, and the corresponding n value will also be recorded.

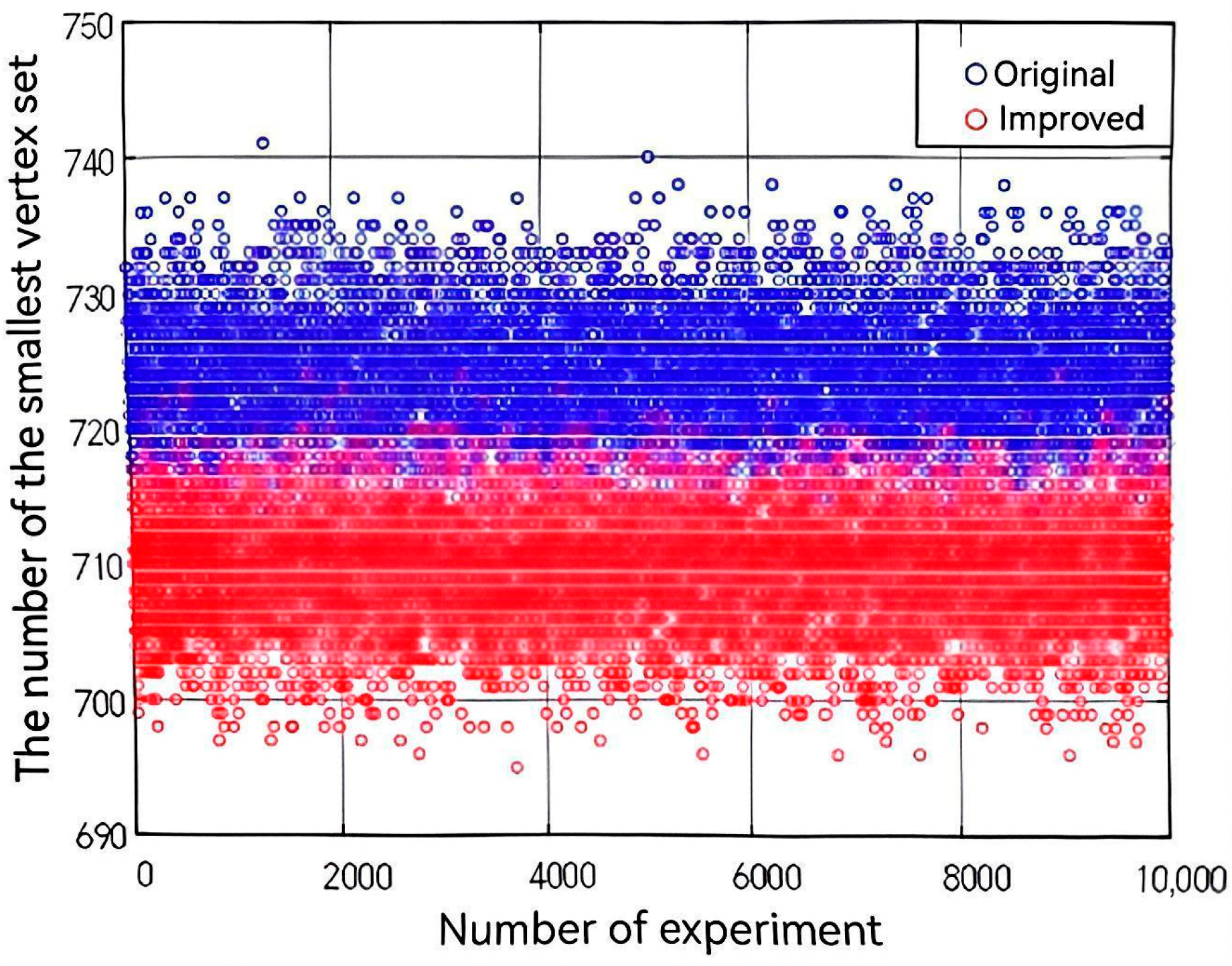

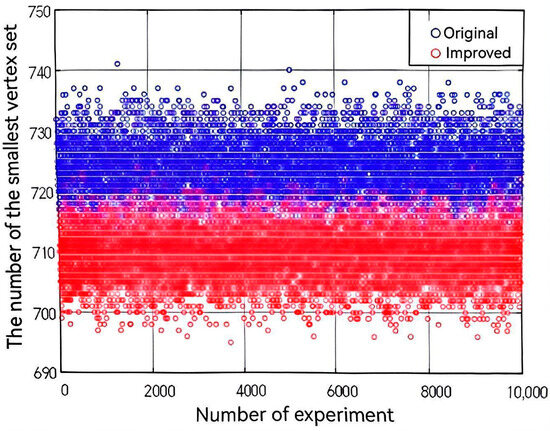

After comparing all 10,000 graphs, divide the accumulated n value by the occurrence frequency of the corresponding situation to obtain the average number of optimized vertices. The final comparison result is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of results before and after model improvement.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that the size of minimum vertex sets obtained by the improved model is significantly lower than that before the improvement, that is, the improved monitoring deployment scheme needs to install fewer monitoring devices. For the graphs with 1000 vertices, the size of the MVC set is primarily concentrated around 725, whereas the MWVC set is concentrated around 710. Therefore, the improved minimum weighted vertex model is more advantageous under the premise of covering all edge sets. The specific data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of optimisation results.

The 10,000 graphs adopted in this experiment are all randomly generated connected bidirectional graphs, ensuring that they can simulate the basic topological structure of the real road network. The degree of each node in the graph is set to follow a uniform distribution between 3 and 6 to conform to the connection conditions of common road intersections.

In 10,000 experiments, the minimum weighted vertex coverage model performed better than the traditional minimum vertex coverage model in 9981 experiments, with an average reduction of 14.56 vertices (mean ± standard deviation: 14.56 ± 2.34). This indicates that for a network of 1000 nodes, the improved surveillance deployment plan can reduce the number of required monitoring devices by approximately 15 on average. This not only lowers the corresponding engineering costs, but also reduces the later maintenance and management costs, as well as the burden of power consumption and data processing. In the few cases where MWVC performed worse (12 experiments), the average increase was only about 2 vertices, indicating its robust overall superiority. These results clearly demonstrate that incorporating vertex weights based on adjacency degree significantly enhances the performance of the vertex cover model for this application.

4. Experiment and Optimization Results Analysis

4.1. Requirement Analysis and Data Preparation

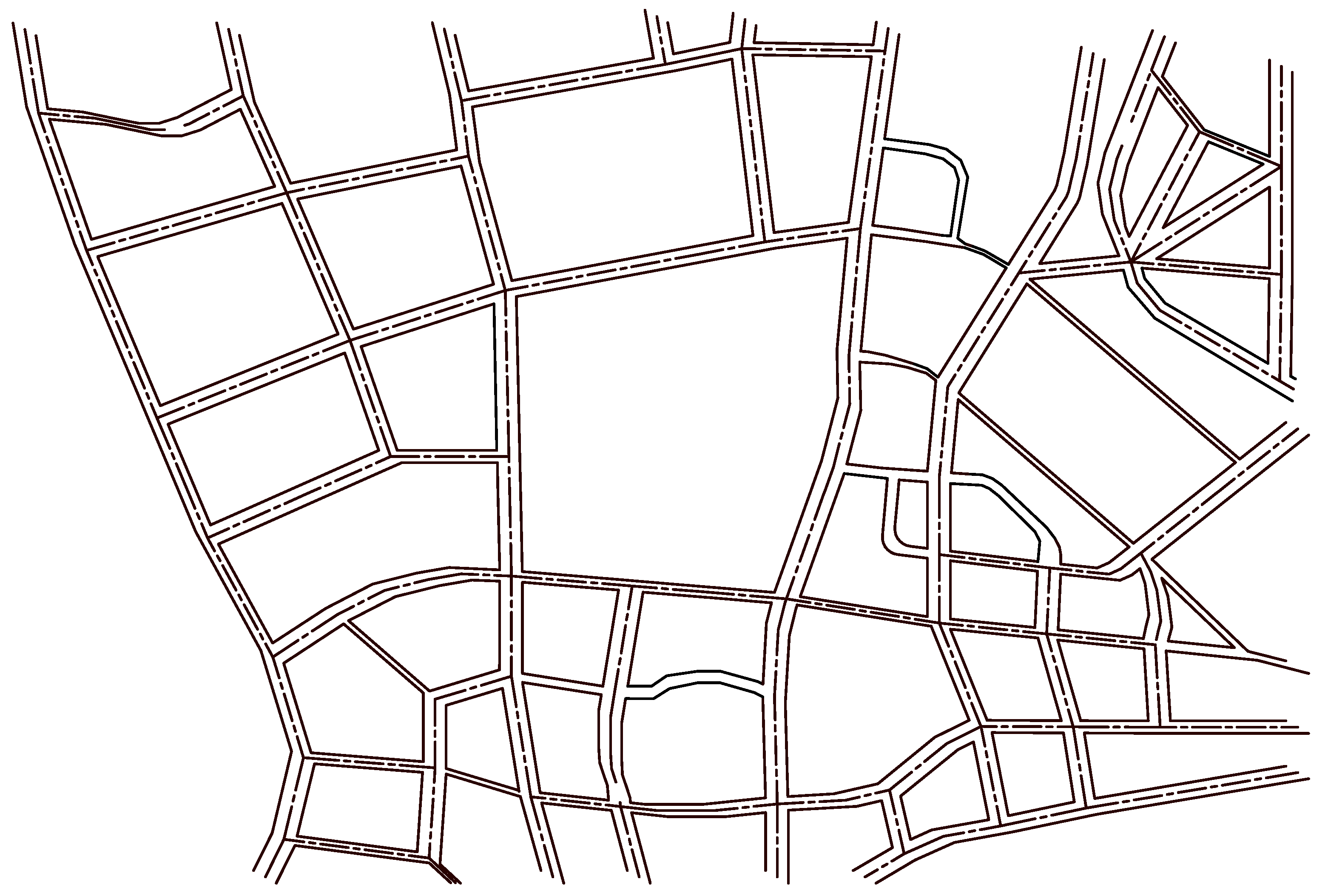

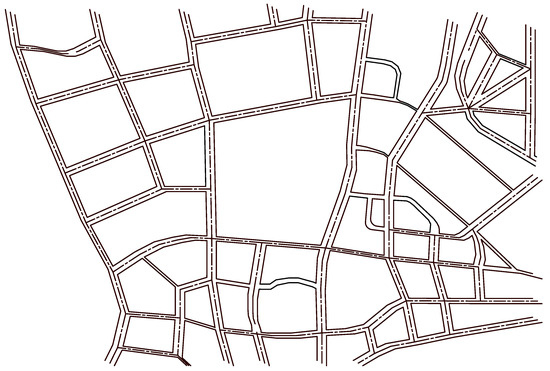

This paper takes a township in Wuwei City, Gansu Province as the main research object, downloads high-resolution geographic information data from Google Earth, and edits the obtained road data through CAD to obtain the road vector diagram shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Surveillance area road vector.

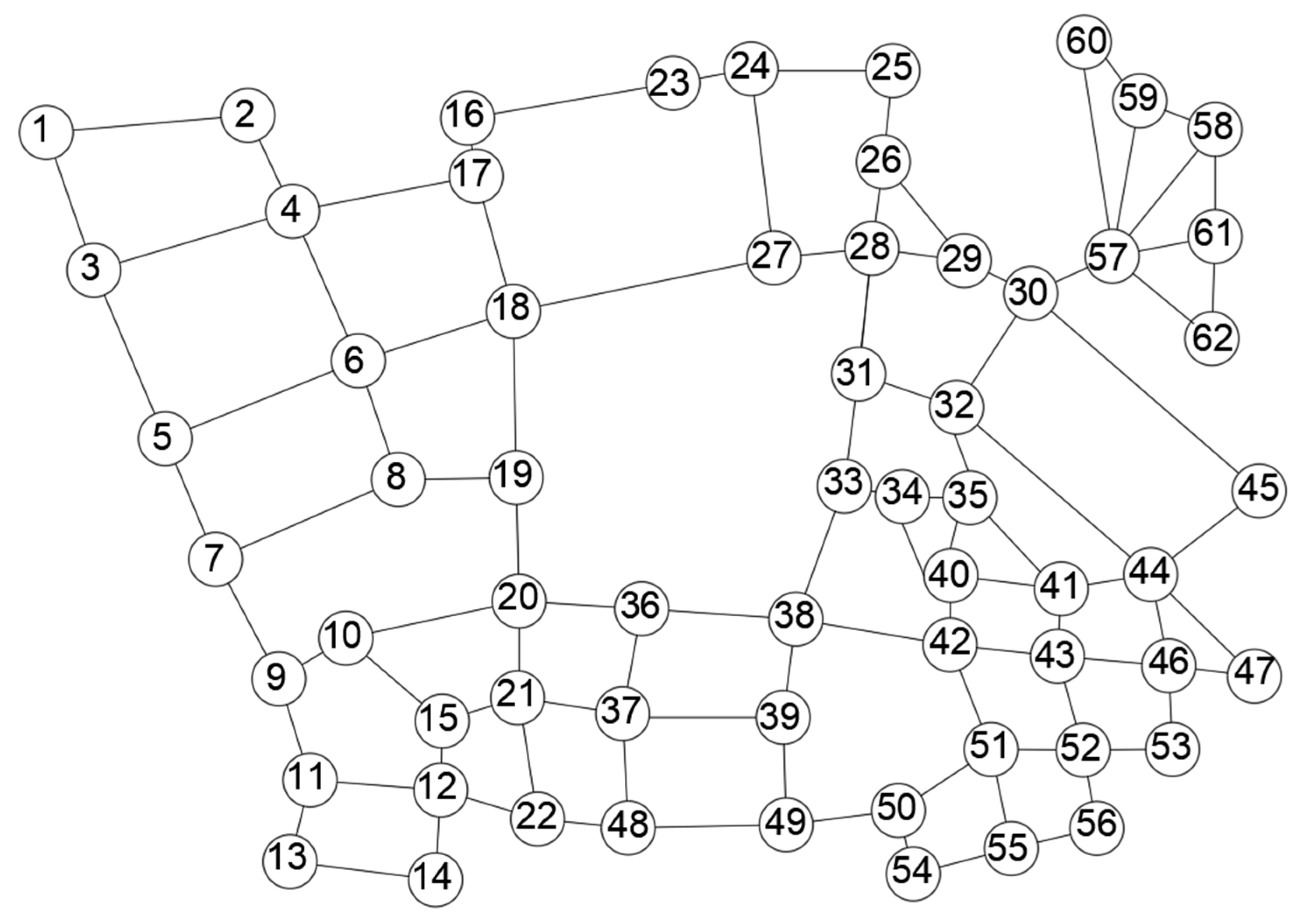

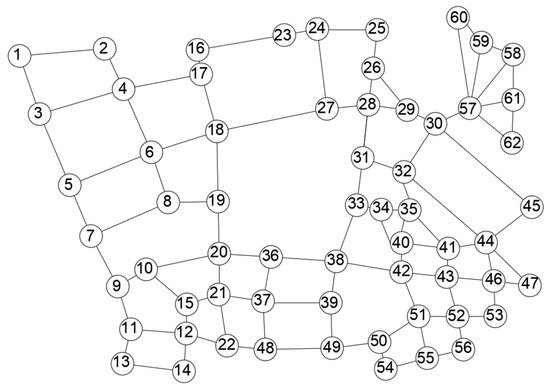

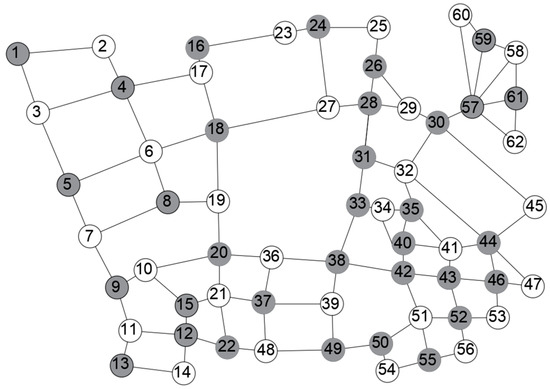

Combining the traffic road data map collected in Figure 8 with the road intersection monitoring deployment model, a video monitoring deployment model based on the research target is established, and the road vector map is mapped to a two-way graph, as shown in Figure 9. The study area includes a total of 62 vertices and 98 edges. In order to facilitate subsequent data processing and model solving, each vertex is numbered.

Figure 9.

Node data distribution map.

4.2. Optimization Results

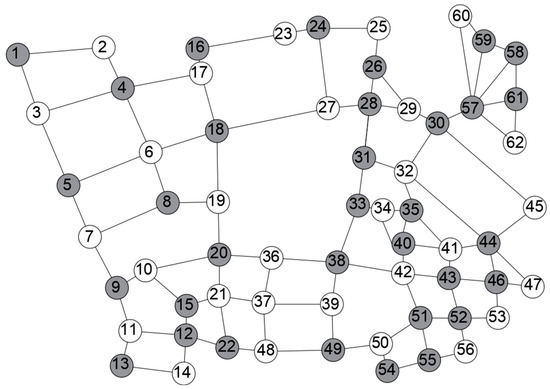

Without affecting the monitoring efficiency, the layout cost is reduced, the number of traffic intersection monitoring equipment is optimized by greedy algorithm, and the numerical calculation is carried out by MATLAB R2022a software. The monitoring layout scheme of traffic intersection is obtained as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Optimisation results for the minimum vertex coverage model.

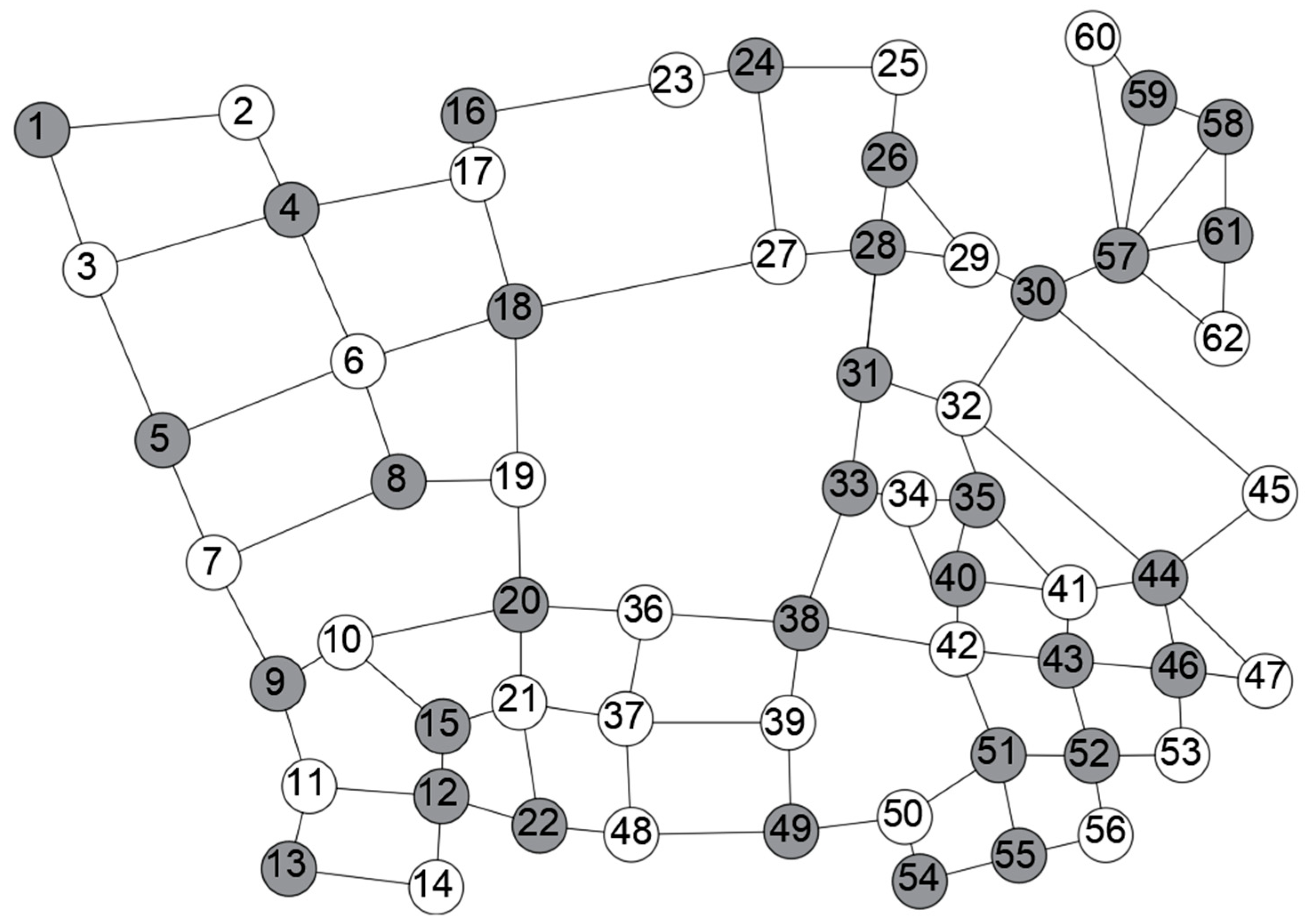

As shown in Figure 10, the minimum vertex cover set generated by the minimum vertex cover model contains 34 vertices: {57, 44, 4, 12, 18, 20, 35, 37, 38, 43, 51, 5, 8, 9, 24, 26, 30, 31, 40, 49, 1, 13, 15, 16, 22, 28, 46, 52, 54, 58, 33, 55, 59, 61}. These minimum set vertices are the intersections arranged by the monitoring equipment of the road map shown in Figure 4. Among them, nodes that do not need to be installed are marked with white; grey nodes represent mandatory installation points. To install directional cameras at these nodes to monitor each road, at least 98 cameras are required. According to the road vertex optimization results in Figure 10, the monitoring scheme is deployed for each part of the road.

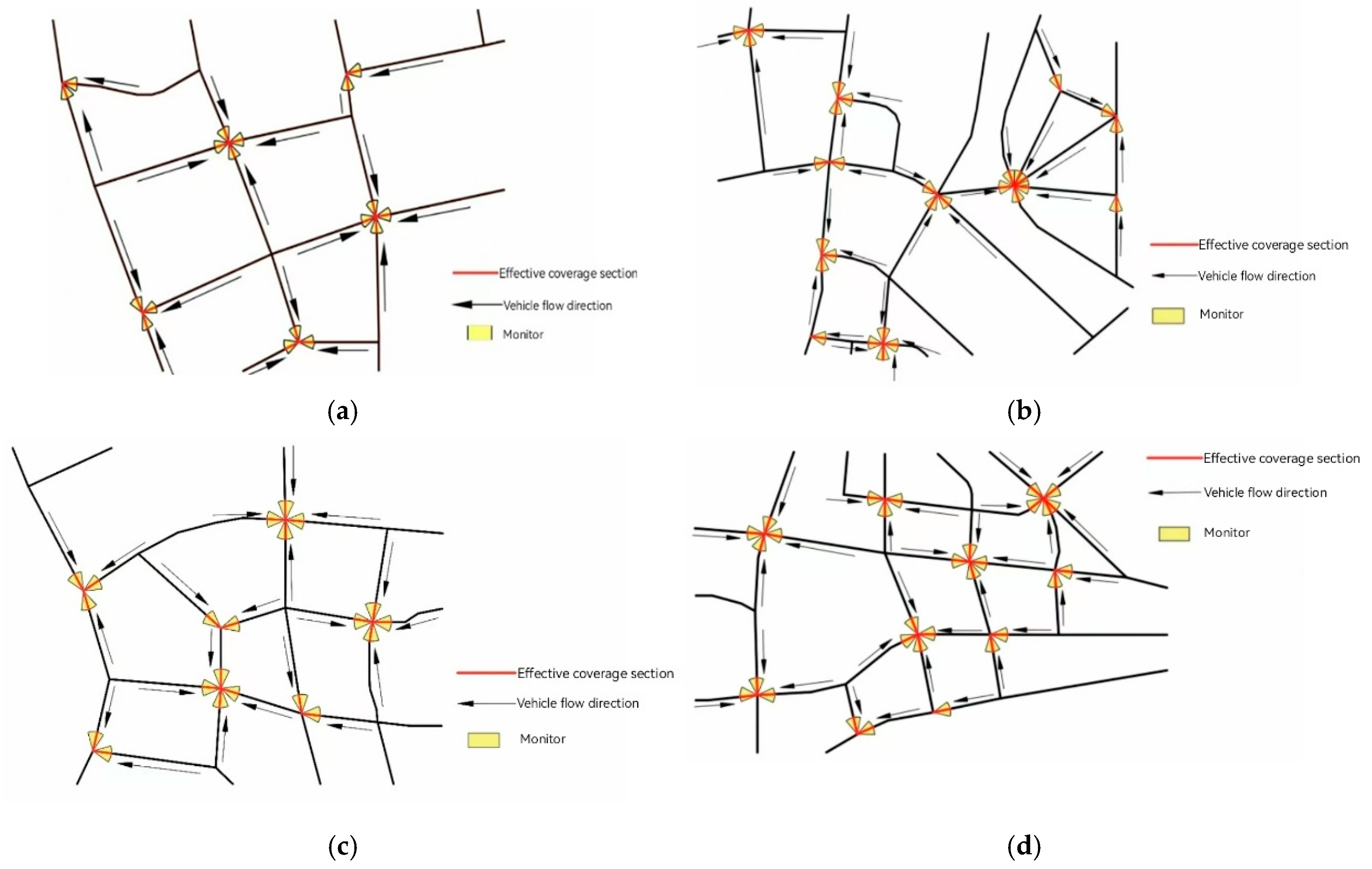

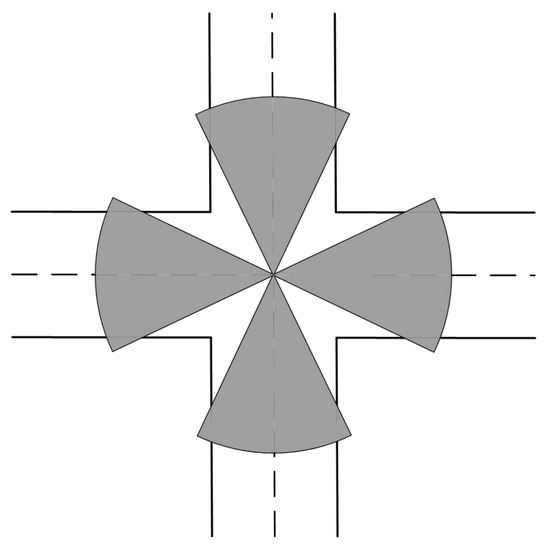

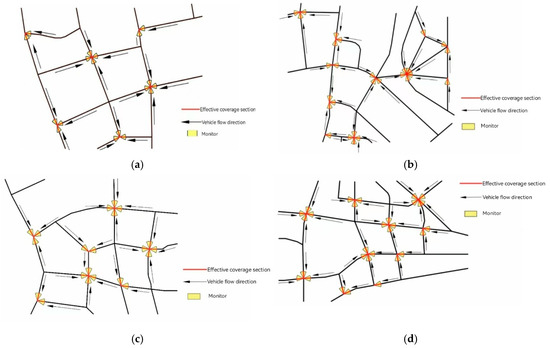

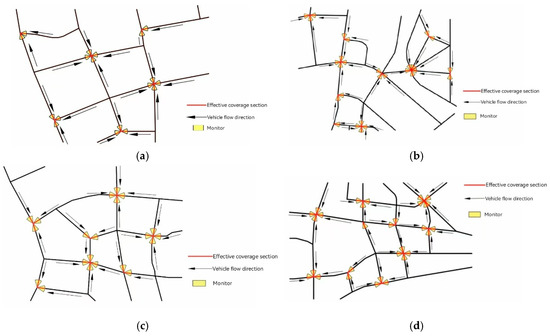

As shown in Figure 11, the yellow sector represents the field of view of a directional camera, and the red line segment represents the area effectively covered. By deploying directional cameras at 34 selected nodes to monitor all roads, it is necessary to set up 34 monitoring poles and install 98 cameras to achieve full coverage of the flow of vehicles and people on the road.

Figure 11.

Road apex monitoring deployment diagram (MVC). (a) The deployment result of Road A monitoring; (b) The deployment result of Road B monitoring; (c) The deployment result of Road C monitoring; (d) The deployment result of Road D monitoring.

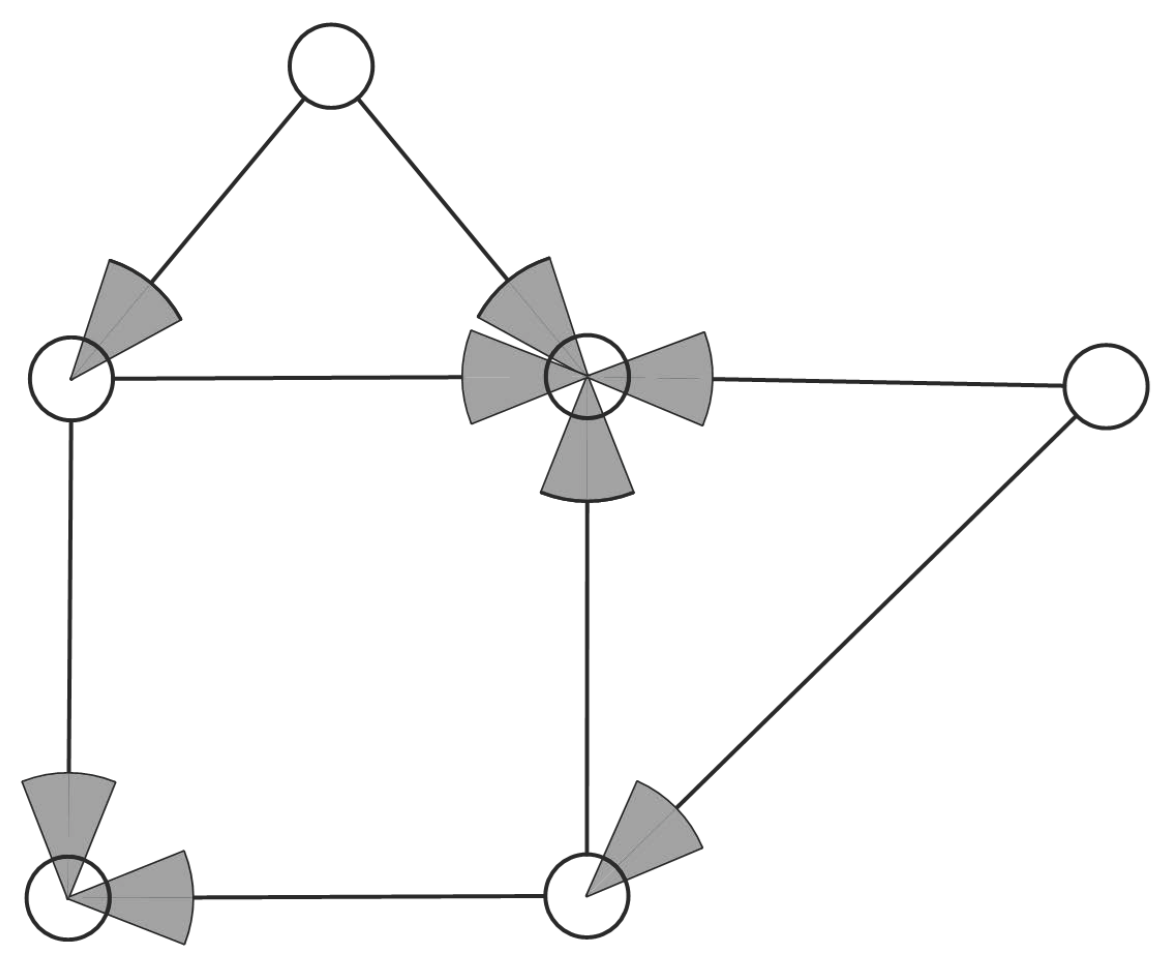

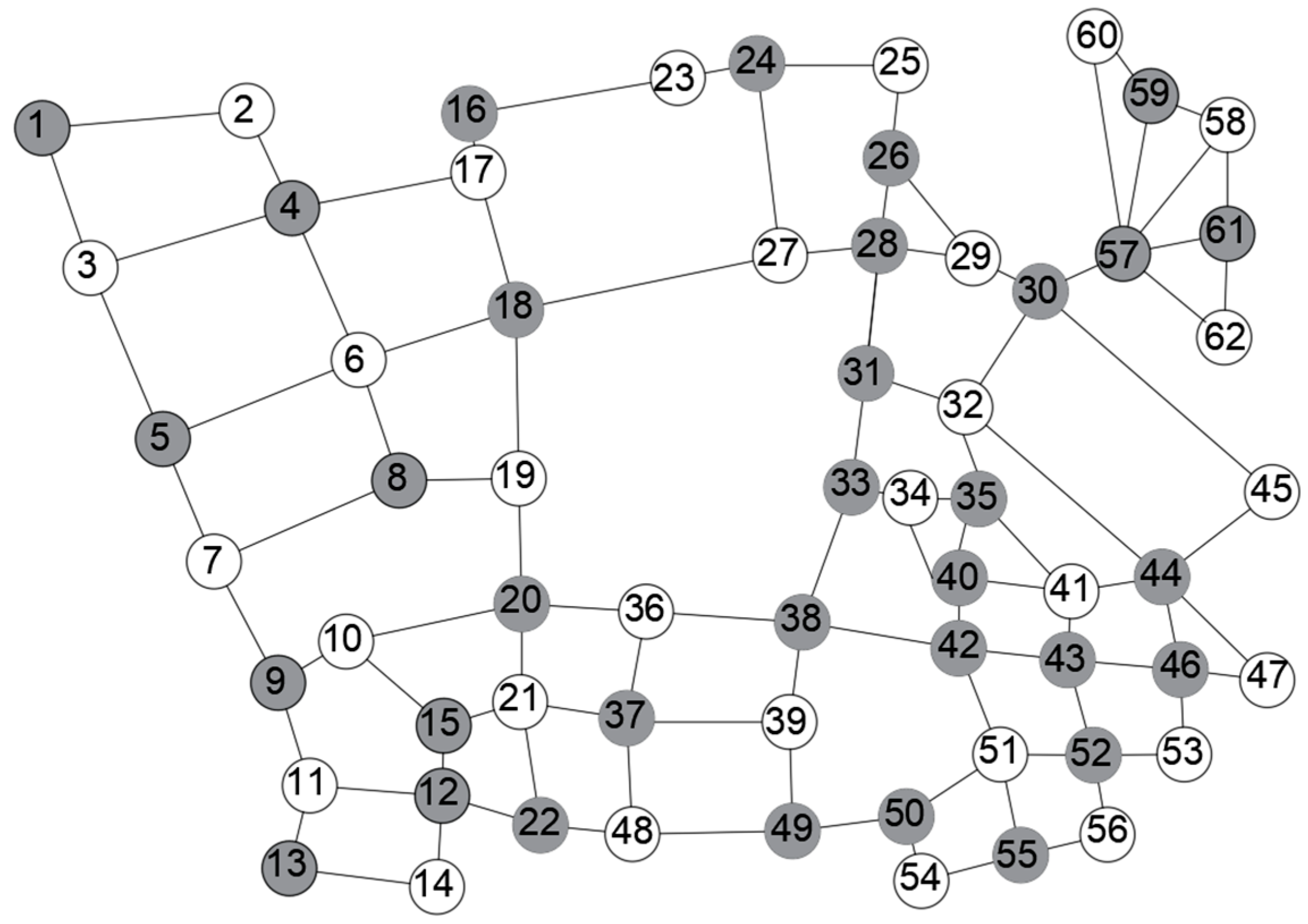

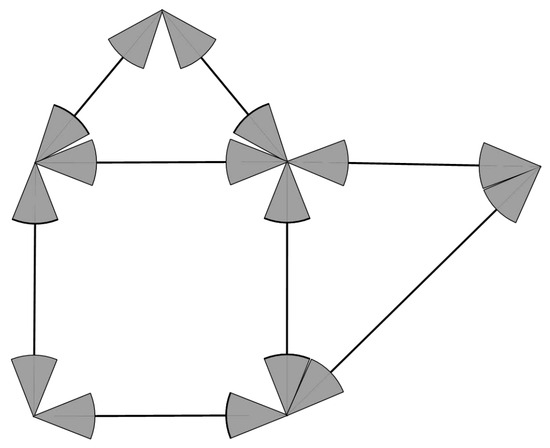

As shown in Figure 12, the minimum vertex cover set generated by the minimum weighted vertex cover model contains 33 vertices: {57, 44, 12, 4, 18, 20, 37, 38, 52, 35, 46, 8, 5, 9, 24, 30, 28, 31, 49, 55, 40, 1, 13, 16, 26, 15, 22, 43, 50, 59, 61, 33, 42}. According to the order of the vertices in the minimum vertex coverage set, the location and layout of the monitoring equipment are carried out. For example, Figure 13 is the road vertex monitoring deployment scheme of each part.

Figure 12.

Optimisation results for the minimum weighted vertex coverage model.

Figure 13.

Road apex monitoring deployment diagram(MWVC). (a) The deployment result of Road A monitoring; (b) The deployment result of Road B monitoring; (c) The deployment result of Road C monitoring; (d) The deployment result of Road D monitoring.

In the scheme shown in Figure 13, although 98 cameras are still needed to monitor the entire road network, only 33 specified nodes need to be installed. This design effectively reduces the complexity of installation and related equipment costs, reduces the maintenance and management costs of the monitoring system, as well as the burden of power consumption and data processing in the subsequent use of the monitoring system, and still achieves a complete coverage of the flow of vehicles and personnel throughout the road. The optimization results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Road vertex optimisation results statistics.

It can be seen from Table 2 that the monitoring deployment scheme before optimization needs to install the monitoring pole on 62 nodes, and 196 monitoring cameras need to be installed to meet the requirements of full coverage of the road section. After optimization using the MVC model, the number of poles was reduced to 34, and the number of cameras was halved to 98. The further improved MWVC model maintains the same number of cameras (98) but reduces the number of required poles to 33. This reduction in installation points, achieved without compromising coverage, leads to lower costs. The relative improvement gained by MWVC over MVC (reducing poles from 34 to 33) is modest in this specific case but demonstrates the model’s refinement principle. The absolute benefit of the optimization approach (MVC/MWVC) over the initial deployment is substantial, and the performance gain of MWVC is expected to be more pronounced in larger, more complex networks.

5. Limitations and Future Work

This study has some limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the model relies on a static network assumption and was validated primarily using a single-city case study, which may limit its generalizability to other urban environments with different topological characteristics. Second, while large-scale simulations were conducted, they were based on synthetic graph data that only partially captures the complexity of real-world road networks.

Future work will focus on testing the proposed method on larger and more diverse real-world road network datasets to further validate its robustness. Another promising direction is to extend the current 2D layout model to 3D surveillance scenarios, accounting for multi-level roads and elevation factors. Additionally, integrating the optimization framework with computer vision-based detection models could create a more comprehensive surveillance system that jointly optimizes hardware deployment and analytical capabilities.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposed a monitoring layout optimization method based on the Minimum Weighted Vertex Cover (MWVC) model for urban road networks. The core innovation lies in incorporating a vertex weighting scheme based on adjacency degree into the traditional Minimum Vertex Cover (MVC) framework, guiding a greedy algorithm towards a more intelligent selection of monitoring locations.

The method was validated through both extensive simulations and a real-world case study. Large-scale simulations on 10,000 random graphs showed that the MWVC model consistently outperformed the MVC model, reducing the vertex cover set size by an average of about 15 vertices (~2% relative reduction). In the practical case study of a township in Wuwei City, the MWVC model further refined the layout obtained by the MVC model. Compared to the initial non-optimized deployment requiring 62 poles and 196 cameras, the MVC model reduced these numbers to 34 poles and 98 cameras. The subsequent MWVC model achieved the same camera coverage (98 cameras) with only 33 poles, representing a further 2.9% reduction in infrastructure points compared to the MVC solution and a total reduction of 46.8% compared to the initial layout.

In summary, the MWVC model provides a computationally efficient and cost-effective solution for surveillance camera deployment in smart city infrastructure. By achieving comparable coverage with fewer installation points, it offers significant savings in equipment, installation, maintenance, and operational costs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and Y.Z.; methodology, T.F.; software, T.F.; validation, Y.Z., T.F. and X.Q.; formal analysis, X.Q.; investigation, L.W.; resources, L.W.; data curation, T.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11302092), the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (21YF5WA060) and the Lanzhou City University Research Projects (4121735). The authors are grateful for the financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- He, F. Intelligent video surveillance technology in intelligent transportation. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 1, 8891449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.G. Intelligent video data security: A survey and open challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 26948–26967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maha Vishnu, V.C.; Rajalakshmi, M.; Nedunchezhian, R. Intelligent traffic video surveillance and accident detection system with dynamic traffic signal control. Clust. Comput. 2018, 21, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Choi, N.; Kwon, H.J.; Kim, H. Surveillance system for real-time high-precision recognition of criminal faces from wild videos. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 56066–56082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocca, P.; Marciano, F.; Alberti, M. Video surveillance systems to enhance occupational safety: A case study. Saf. Sci. 2016, 84, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Zhou, L.; Yin, Q.; Lin, B. Research on the Evaluation Method of Surveillance Camera Layout for 3D Spatial Grids. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altahir, A.A.; Asirvadam, V.S.; Hamid, N.H.B.; Sebastian, P.; Saad, N.B.; Ibrahim, R.B.; Dass, S.C. Optimizing visual sensor coverage overlaps for multiview surveillance systems. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 4544–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, E.; Martínez, D.; Brugués-i-Pujolràs, R.; Farreras, M.; Saló-Grau, J.; Pueyo-Ros, J.; Corominas, L. Optimal selection of monitoring sites in cities for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in sewage networks. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsmirat, M.; Sarhan, N.J. Intelligent optimization for automated video surveillance at the edge: A cross-layer approach. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 105, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R. A note on the use of the analytic hierarchy process for environmental impact assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 63, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemann, A.; Fouillet, A.; Brand, H.; Krafft, T. Success factors of European syndromic surveillance systems: A worked example of applying qualitative comparative analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritter, J.; Brévilliers, M.; Lepagnot, J.; Idoumghar, L. On the optimal placement of cameras for surveillance and the underlying set cover problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 74, 133–153.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, M.S.; Narayanan, A.; Menon, V. Maximizing camera coverage in multicamera surveillance networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 10170–10178.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, S.V.T.; Lee, D.; Pham, H.C.; Dang, L.H.; Park, C.; Lee, U.K. Leveraging BIM for enhanced camera allocation planning at construction job sites: A voxel-based site coverage and overlapping analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Chakrabarty, K. Sensor deployment and target localization in distributed sensor networks. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. (TECS) 2004, 3, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dou, W. A fast candidate viewpoints filtering algorithm for multiple viewshed site planning. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Venkateswaran, N. Intelligent Power Grid Video Surveillance Technology Based on Efficient Compression Algorithm Using Robust Particle Swarm Optimization. Wirel. Power Transf. 2021, 2021, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).