Abstract

The inherent spatial inaccessibility of cliff inscriptions and the dilemma between preservation and public access have made digital dissemination essential for their legacy. Using the digital design of the “Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions” in Hanzhong as a case study, this research integrates the four-dimensional experience economy model with the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to construct a mixed evaluation framework combining expert rational weighting and user perceptual scoring. Weightings were determined by seven experts, and user experience data was collected from 198 questionnaires. The priority for platform optimization was then identified via a “weight × gap” matrix. The results show the following: (1) In digital settings, the experience structure is significantly reordered, with interactivity (44.4%) and immersion (29.8%) taking the lead. (2) Overall platform satisfaction was good (4.05 out of 5.00), but diversity of operations and depth of knowledge emerged as the main shortcomings. (3) A staged optimization scheme of “progressive interaction + hierarchical knowledge delivery” is proposed, which can enhance sustainable dissemination effectiveness without increasing technological barriers. This study proposes a sustainability-oriented strategy prototype for the digital communication of cliff inscriptions, develops second-level constructs for design and measurement support, and employs AHP-based expert weighting to prioritize strategy elements and derive design pathways. The platform functions as a research prototype for academic inquiry and methodological demonstration, without involvement in operational KPI loops or full system deployment. The contribution lies in offering a replicable user experience evaluation grid and a closed-loop optimization process, rather than advancing 3D/AR/VR techniques per se.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Significance

Cliff inscriptions are significant carriers of human culture, often referred to as “history books carved upon the earth” [1]. Over 100,000 such inscriptions exist in China, mostly distributed in remote and inaccessible mountainous regions and often scattered [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Natural factors such as weathering and water erosion, coupled with human activities like touching and rubbing, have posed severe challenges to their preservation [8,9,10,11,12]. Meanwhile, the traditional “see–photograph–leave” pattern of museum visits is losing its experiential appeal, leading to declining user engagement and insufficient cultural identification [13,14]. How to achieve sustained remote dissemination of cliff inscriptions while ensuring their protection has become an urgent topic in the field of cultural heritage conservation and utilization.

1.2. The Current State of Digital Dissemination

In recent years, advances in high-precision 3D scanning, WebGL online visualization, and AR/VR technologies have provided new pathways for the digital preservation and dissemination of cliff inscriptions [15,16,17,18]. Multiple museums and research institutes have launched projects involving 3D modeling, virtual tours, and interactive interpretation. However, most remain at a superficial “technology showcase” stage, failing to stimulate in-depth user participation or lasting engagement, as exemplified by the “Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions” at the Hanzhong Museum (see Figure 1). Studies show that on some platforms, average user dwell times are less than three minutes and revisit rates are below 10%, making it difficult to generate long-term cultural identification and dissemination effects.

Figure 1.

Exhibition of the Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions (a series of calligraphic stone carvings located in Hanzhong, Shaanxi Province, China) at Hanzhong Museum.

1.3. Experience Economy Theory and Its Application

The four-dimensional experience economy model (education, entertainment, aesthetics, escapism) has been widely validated in the fields of tourism, museums, and theme parks [19,20,21]. In tourism, immersive experiences significantly enhance visitor satisfaction and loyalty, while in museums, interactive exhibitions and immersive spaces help strengthen cultural identity and learning outcomes. However, existing research mainly focuses on tangible scenarios with in-person interaction, and systematically empirical studies on experience dimensions and their weighting for “purely digital plus immovable” heritage remain lacking [22,23,24].

1.4. Review of Evaluation Methods

A variety of methods are used to evaluate the effectiveness of digital dissemination of cultural heritage. Expert-driven methods such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Delphi method excel at constructing scientific weighting systems but tend to rely on rational judgment, making it hard to reflect the true sentiments of the public [25,26]. User-driven methods, such as quantitative surveys and user-generated content (UGC) analysis, emphasize user perception but lack rational weighting support [27,28,29]. Most existing studies focus on one-sided perspectives (e.g., IPA quadrant analysis [30,31,32]) and have yet to form a closed, integrated framework combining “expert rationality” and “user sensibility”. Additionally, there has been little in-depth integration of AHP-derived weightings with large-sample user data [33,34].

1.5. Research Gaps

From the above review, three primary shortcomings in remote digital dissemination of cliff inscriptions are identified:

- (1)

- Lack of empirical support for experience dimension weights, complicating the prioritization of platform functions;

- (2)

- Disconnection between expert-based weighting and user experience evaluation, with no hybrid models forming a closed evaluation–optimization loop;

- (3)

- Existing studies mostly focus on the presentation of results, lacking actionable iterative solutions and thus struggling to enhance sustainable dissemination outcomes.

1.6. Research Objectives and Innovations

Taking the digital design of the “Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions” as a case study, this research aims to:

- (1)

- Validate the applicability of the four-dimensional experience economy model to cliff inscription digital scenarios and reveal the reordering of weights for education, entertainment, aesthetics, and immersion;

- (2)

- Construct a hybrid evaluation framework combining expert-based AHP weighting and user perception scoring, and propose a “weight × gap” priority analysis approach to achieve a closed loop from evaluation to optimization;

- (3)

- Based on empirical results, design an iterative scheme of “progressive interaction + hierarchical knowledge delivery”, thus providing a replicable tool for the sustainable digital dissemination of cliff inscriptions and similar immovable heritage.

Innovations:

- (1)

- For the first time, the experience economy model is contextually extended and empirically validated in a “purely digital plus immovable” heritage scenario;

- (2)

- A “rational weighting—sensory scoring—integrated analysis” paradigm is proposed to bridge the gap between expert judgment and user experience in evaluation;

- (3)

- A full-chain methodology is developed, providing decision support for the continuous operation of digital cultural heritage platforms, from indicator construction to iterative optimization.

1.7. Structure of This Paper

Section 2 reviews digital cultural heritage dissemination, the application of experience economy theory, and evaluation methods. Section 3 introduces the case selection, index system construction, and the hybrid evaluation approach. Section 4 presents the results of weight calculation, user scoring, and priority analysis. Section 5 discusses theoretical and practical implications. Section 6 summarizes the conclusions and addresses research limitations and future directions. We do not aim to improve 3D modeling or AR/VR algorithms. AR/VR is one of multiple modules used to examine the immersion–accessibility trade-off. Given low attempt rates under device constraints, we recommend a tiered immersion strategy (web-first with optional AR/VR) to enhance experience quality without raising barriers.

2. Related Work

2.1. Technological Evolution in Digital Cultural Heritage Dissemination

The digital cultural heritage field has evolved through three primary stages: starting from high-precision 3D data acquisition and reconstruction [35,36], advancing to WebGL-based online visualization and interaction [16,17,18,37], and moving toward multimodal integration involving artificial intelligence, augmented reality, and social media [38,39,40,41,42]. Key technological breakthroughs include improvements in scanning accuracy from centimeter-level to millimeter-level [40,41]; the development of integrated “spectral-geometric” multimodal workflows [42]; and the rapid lowering of the threshold for online 3D displays thanks to advances in real-time rendering with WebGL [18]. Despite growing technical maturity, substantial progress in user stickiness and cultural identification remains elusive.

2.2. Unique Challenges in the Digitization of Cliff Inscriptions

Cliff inscriptions, together with surrounding mountains, vegetation, and water systems, constitute complex landscapes that require large-scale modeling using technologies such as drone-based Structure-from-Motion (SfM) [35]. Long-term weathering leads to loss of surface information, making ultrasonic testing (UT) advantageous for diagnosing internal damage [43]. From a knowledge interpretation perspective, collaborations between archaeology and epigraphy have narrowed disciplinary gaps [36], yet the absence of unified open data standards (such as EpiDoc and CIDOC CRM) impedes cross-platform data integration. In China, research has mostly focused on technical demonstrations, with insufficient discussion on user cognitive processes.

2.3. Application of Experience Economy Theory in Cultural Heritage

The four-dimensional experience economy model (education, entertainment, aesthetics, escapism) has been validated in settings such as museums and tourism [19,20,21], yet differences in heritage types and platform designs result in varied dimension weightings [22,23,24,28]. In AR-guided systems, narrative-based interaction can significantly enhance immersion and memory retention [44], while touch-based interactions outperform in-air gestures in terms of usability [45]. These findings indicate the need to balance technological innovation and user cognitive load in digital environments to develop an experience structure suitable for cliff inscriptions.

2.4. Development of Cultural Heritage Evaluation Methods

Expert-driven approaches—such as AHP, AHP-Entropy, DEMATEL-ANP, and AHP-EDAS—have established relatively comprehensive weighting systems based on rational judgment [25,34,46,47,48,49,50,51], but struggle to fully reflect perceptual differences among users. User experience evaluation has evolved from simple satisfaction scales to the integration of behavioral data, social media text, and physiological signal analysis [26,27,44,52,53,54,55], highlighting the importance of affective feedback. While each methodological strand has strengths, there is a lack of cross-validation and closed-loop optimization mechanisms.

2.5. Research Gaps and Positioning of This Study

In summary, four major gaps exist in the digital dissemination of cliff inscriptions: (1) There is a lack of empirical evidence concerning the contextual specificity of experience dimension weights for “purely digital plus immovable” heritage; (2) Deep coupling mechanisms between expert rationality and user sensibility have not been established; (3) Pathways from static evaluation to dynamic optimization remain unclear; (4) Theoretical frameworks lag behind practical needs. To address these issues, this study takes the “Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions” digital platform as a case, establishing a closed-loop model that integrates “expert AHP weighting, user experience scoring, and weight × gap analysis,” aiming to bridge these gaps and provide operable methodological tools.

3. Methods

3.1. Overview of Research Design

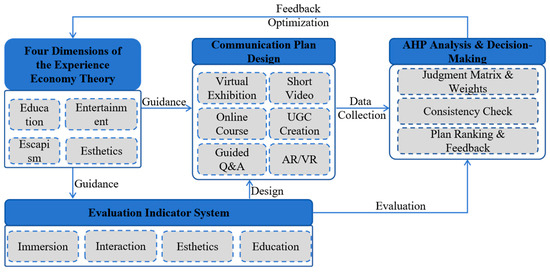

This study employs a mixed-methods research design, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches to construct a “theoretical modeling–empirical evaluation–optimization strategy” research framework. This research is conducted in four phases: (1) constructing an evaluation index system based on experience economy theory; (2) determining indicator weights using the Delphi method and AHP; (3) collecting user experience data via questionnaire survey; (4) synthesizing analysis and proposing optimization strategies. The research framework is illustrated in Figure 2. This framework emphasizes a cyclic and iterative process of “theory-driven, data-supported, practice-oriented” research, ensuring both academic rigor and practical relevance.

Figure 2.

Research Framework.

3.2. Selection of Research Object

3.2.1. Case Selection

The Hanzhong Museum was chosen as the research object, for the following reasons:

- (1)

- Representativeness: The Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions are classified as top-level national cultural relics, exemplifying the highest artistic achievements of Chinese cliff inscriptions, with significant historical and cultural value.

- (2)

- Technical Integrity: The platform prototype covers multiple modules, including virtual exhibitions, interactive experiences, and educational courses.

- (3)

- Data Availability: The research team focuses on museum studies; however, the platform described in this paper is a research prototype intended solely for academic research and method validation. Whether it will be jointly implemented with the museum is still under discussion and evaluation. We do not claim any deployed application at this stage. Appendix A provides the full questionnaire items.

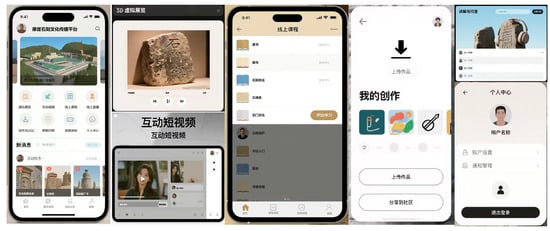

3.2.2. Definition of Functional Modules

The platform consists of six major functional modules, corresponding to the four dimensions of the experience economy. The communication scheme is shown in Figure 3, and further details about the modules and their correspondence to experience dimensions are provided in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Application (APP) Communication Scheme.

Table 1.

APP Functional Modules Corresponding to Experience Dimensions.

Each module is tailored to the cultural characteristics and technical requirements of cliff inscriptions, offering mechanisms for active exploration, multi-sensory presentation, layered knowledge delivery, and user co-creation platforms, thereby providing diverse entry points to satisfy different user needs.

3.3. Construction of the Evaluation Index System

3.3.1. Development Process

A combination of deductive and inductive approaches was adopted to ensure the theoretical foundation and practical relevance of the index system:

Step 1: Literature review and initial extraction—systematically reviewed 112 relevant articles on experience economy and digital heritage evaluation, initially extracting 48 candidate indicators.

Step 2: Expert interviews and contextual adjustment—conducted in-depth interviews with five experts (two heritage protection experts, two digital media specialists, one museum manager; each interview lasted 60–90 min), adding 12 context-specific indicators.

Step 3: Delphi screening and optimization—organized two rounds of consultation among 12 experts: in the first round, experts rated the importance of 60 candidate indicators (scale 1–5); 18 indicators with mean scores < 3.5 were dropped. In the second round, 42 remaining indicators were subjected to cluster analysis and semantic merging, ultimately resulting in 12 Second-level constructs.

Step 4: Pilot test and expression optimization—recruited 30 users for a pilot test and refined the indicators’ wording based on feedback, ensuring clarity and unambiguity.

3.3.2. Final Index System

A hierarchical index system with 4 primary and 12 Second-level constructs was developed:

A. Immersion

A1. Scene Authenticity: Similarity between the virtual environment and the real inscriptions, including texture, lighting, and proportions

A2. Sensory Stimulation: Richness and coherence of multi-sensory (visual, auditory) experiences

A3. Attentional Focus: Degree of user concentration and time distortion during the experience

B. Education

B1. Knowledge Richness: Depth, breadth, and accuracy of historical, artistic, and cultural knowledge

B2. Ease of Understanding: Clarity of content organization and comprehensibility of presentation

B3. Learning Effectiveness: User’s actual gains in knowledge acquisition, comprehension, and memory

C. Interaction

C1. Operational Diversity: Variety and innovativeness of interaction modes available

C2. Participation Convenience: Ease of use, smoothness, and learning cost of interaction

C3. Feedback Immediacy: Speed, accuracy, and effectiveness of system response to user actions

D. Aesthetics

D1. Visual Attractiveness: Artistic quality, harmony, and professional standard of design

D2. Cultural Ambience: Depth and natural integration of traditional cultural elements

D3. Innovative Expression: Degree of innovative integration between digital technology and cultural content

3.4. Determination of AHP Weights

3.4.1. Expert Selection

Purposive sampling was used to select seven experts: two in heritage conservation, two in digital cultural dissemination, two in experience economy research, and one in digital media design.

3.4.2. Construction of Judgment Matrices

Training Session: A two-hour online workshop was held to explain evaluation criteria, scoring rules, and key considerations, ensuring consistent understanding.

Independent Scoring: Experts independently completed pairwise comparisons within two weeks, using the Saaty 1–9 scale. A hierarchical comparison strategy was applied: primary dimensions compared first, followed by Second-level constructs under each dimension.

Consistency Check: The consistency ratio (CR) of each judgment matrix was computed; matrices with CR > 0.1 were revised by the experts until consistency requirements were met.

Group Decision: The geometric mean method was used to aggregate the individual matrices into a group consensus matrix.

3.4.3. Weight Calculation Steps

Weights were computed using the eigenvalue method:

- (1)

- Construct the judgment matrix

- (2)

- Calculate the maximum eigenvalue and the corresponding eigenvector

- (3)

- Normalize the eigenvector to obtain the weight vector

- (4)

- Consistency check:

3.5. User Experience Survey

3.5.1. Sample Size Determination

Structural equation modeling suggests a sample size 5–10 times the number of indicators. With 36 items (12 Second-level constructs × 3 questions each), the target sample size was 180–360. Considering a 20% inefficiency rate, 220 questionnaires were distributed.

3.5.2. Sampling Method

Quota sampling was applied to ensure sample representativeness:

Age: 18–25 (30%), 26–35 (30%), 36–45 (25%), above 45 (15%)

Education: High school or below (20%), College/Undergraduate (60%), Graduate and above (20%)

Usage Experience: First-time users (30%), Occasional users (40%), Frequent users (30%)

Sampling rationale and representativeness: The 18–35 age group is more active in digital cultural tourism and immersive experiences, representing a typical early-adopter profile. The high proportion of this cohort in our sample reflects this social phenomenon and provides demand-side evidence for setting strategic priorities. The conclusions of this study are limited to the present context and sample.

3.5.3. Data Collection Procedure

Platform Experience: Participants were required to engage for at least 30 min and use at least four functional modules, ensuring comprehensive familiarity with the platform.

Immediate Evaluation: Participants complete the questionnaire immediately after experiencing the prototype to reduce recall bias.

Quality Control:

- -

- Three attention-check questions (e.g., “Please select ‘Strongly Agree’”)

- -

- Discarded questionnaires completed in less than 5 min

- -

- Discarded questionnaires with identical responses to all items

- -

- Checked for duplicate IP addresses to prevent repeated submissions

3.5.4. Measurement Tool and Documentation

A Likert 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) was used, with three items designed for each secondary indicator, totaling 36 items. Additionally, one item each measured overall satisfaction, willingness to recommend, and intention to revisit.

Sample items:

A1 Scene Authenticity: “The virtual display of the inscription closely matches the real artifact details.”

B2 Ease of Understanding: “The platform’s explanations are clear and easy to understand, helping me grasp the meaning of the inscriptions.”

C1 Operational Diversity: “The platform offers a wide variety of interaction options for me to choose from.”

This paper confines “dimensions” to the four first-order dimensions of the experience economy. “Second-level constructs” are used to organize the content domain and guide item development. Measurement is implemented with Likert-type items; we do not directly construct SMART, operational “indicators (KPIs)”. Items are designed in accordance with the principles of being specific, measurable, relevant, attainable, and context-explicit, and their comprehensibility and internal consistency are verified in a pretest.

3.6. Data Analysis Methods

3.6.1. Descriptive Statistics

Sample characteristics: frequency and percentage

Experience scores: mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis

Distribution normality: Kolmogorov–Smirnov test

3.6.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

Reliability: Cronbach’s α > 0.7

Convergent validity: AVE > 0.5, CR > 0.7

Discriminant validity: square root of AVE greater than inter-construct correlations

3.6.3. Weight-Score Comprehensive Analysis

Weighted score calculation:

Gap analysis:

Prioritization: ranked by magnitude of weighted gaps.

3.6.4. Statistical Software

SPSS 20.0 was used for descriptive and reliability analyses, Expert Choice 11.5 for AHP calculations, and AMOS 24.0 for confirmatory factor analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics and Data Quality

4.1.1. Sample Composition

A total of 220 questionnaires were distributed, with 198 valid responses collected (effective response rate 90%). The sample characteristics generally conformed to the quota plan (see Table 2), ensuring good representativeness. Demographically, the gender distribution was balanced (male 46.5%, female 53.5%); the age structure was reasonable, mainly concentrated among young and middle-aged adults (18–35 years accounting for 60.1%); education level was predominantly college/undergraduate (61.1%); and usage experience with digital cultural products followed a normal distribution, with occasional users being the largest group (41.4%). Respondents experienced the prototype offsite using mobile devices, primarily engaging with the regular and light-interaction modules; due to device limitations, attempts with the immersive module were relatively infrequent.

Table 2.

Sample Demographics (N = 198).

4.1.2. Reliability and Validity Test Results

Table 3.

Reliability and Validity of the Scales.

As shown in Table 3, all subscales demonstrated high reliability: Cronbach’s α values exceeded 0.878 for each dimension and reached 0.946 for the overall scale. Composite reliability (CR) ranged from 0.881 to 0.908, and average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.712 to 0.767, all exceeding recommended thresholds, indicating sound reliability and convergent validity. The KMO value was 0.928; Bartlett’s test confirmed suitability for factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis showed good model fit (χ2/df = 2.13, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.076), supporting the four-dimensional structure.

4.2. Results of AHP Weight Calculation

4.2.1. Primary Dimension Weights

As shown in Table 4, the calculated weights for the Primary Dimensions revealed marked differences: (1) Interaction (0.444): Highest weight, reflecting users’ strong demand for active participation in digital environments. (2) Immersion (0.298): Second place, highlighting the core feature of virtual experiences. (3) Education (0.136): Lower priority, possibly indicating expert recognition of entertainment trends. (4) Aesthetics (0.122): Lowest, but still essential for supporting the overall experience.

Table 4.

Judgment Matrix and Weights for Primary Dimensions.

Table 4.

Judgment Matrix and Weights for Primary Dimensions.

| Indicator | A | B | C | D | Weight | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Immersion | 1 | 3 | 1/2 | 3 | 0.298 | 2 |

| B Education | 1/3 | 1 | 1/3 | 2 | 0.136 | 4 |

| C Interaction | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.444 | 1 |

| D Aesthetics | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1 | 0.122 | 3 |

| λmax = 4.094, CI = 0.031, RI = 0.90, CR = 0.035 < 0.10 | ||||||

The judgment matrix passed the consistency test.

4.2.2. Global Weights of Second-Level Constructs

As shown in Table 5, The top three are: C2 Participation Convenience (0.197): Usability is foundational for user experience. C1 Operational Diversity (0.172): Rich interaction choices strengthen user agency. A2 Sensory Stimulation (0.135): Multi-sensory experience enhances immersion. Lower weights for B3 (Learning Effectiveness, 0.025) and D3 (Innovative Expression, 0.021) may indicate insufficient investment in education and innovation functions.

Table 5.

Global Weights of Second-level constructs.

Table 5.

Global Weights of Second-level constructs.

| Rank | Code | Name | Local Weight | Global Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C2 | Participation Convenience | 0.443 | 0.197 |

| 2 | C1 | Operational Diversity | 0.387 | 0.172 |

| 3 | A2 | Sensory Stimulation | 0.454 | 0.135 |

| 4 | A3 | Attentional Focus | 0.321 | 0.096 |

| 5 | C3 | Feedback Immediacy | 0.17 | 0.075 |

| 6 | A1 | Scene Authenticity | 0.225 | 0.067 |

| 7 | B1 | Knowledge Richness | 0.545 | 0.074 |

| 8 | D2 | Cultural Ambience | 0.443 | 0.054 |

| 9 | D1 | Visual Attractiveness | 0.387 | 0.047 |

| 10 | B2 | Ease of Understanding | 0.273 | 0.037 |

| 11 | B3 | Learning Effectiveness | 0.182 | 0.025 |

| 12 | D3 | Innovative Expression | 0.17 | 0.021 |

4.3. User Experience Evaluation Results

4.3.1. Dimension Scores

As shown in Table 6, the results show overall good performance, with differences across dimensions.

Aesthetics (4.15): Highest score, indicating user recognition of visual design. Immersion (4.12): Good virtual environment creation. Interaction (4.08): Adequate, with room for improvement. Education (3.85): Lowest, reflecting shortcomings in knowledge delivery.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics of Experience Dimensions.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics of Experience Dimensions.

| Dimension | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion | 4.12 | 0.62 | 2.33 | 5 |

| Education | 3.85 | 0.71 | 2 | 5 |

| Interaction | 4.08 | 0.68 | 2.11 | 5 |

| Aesthetics | 4.15 | 0.65 | 2.44 | 5 |

| Overall Satisfaction | 4.05 | 0.69 | 2 | 5 |

Overall satisfaction is 4.05, which is “satisfactory” but not “very satisfactory”.

4.3.2. Detailed Scores for Second-Level Constructs

As shown in Table 7, C2 Participation Convenience: Best performer (Mean 4.23, Weight 0.197, Weighted Score 0.833), indicating smooth basic operations. C1 Operational Diversity: Largest weighted gap (0.186), suggesting the top improvement priority. A2 Sensory Stimulation & A3 Attentional Focus: Means above 4.0, with gaps ≈ 0.1, showing a solid foundation for immersion. B1 Knowledge Richness: Lowest mean (3.78), weighted score only 0.28—content depth insufficient. D2 Cultural Ambience: Low weight but higher score (4.21), traditional character well received but innovation still lacking.

Table 7.

Second-level constructs Scores and Weighted Analysis.

Overall, the platform shows strengths in “usability–immersion–cultural ambience”, but should focus on enhancing “operational diversity” and “knowledge depth”.

4.4. Synthesis of Weight and Score

As shown in Table 8, C1 Operational Diversity and C2 Participation Convenience are the foremost areas for improvement.

Table 8.

Improvement Priority Ranking.

4.5. Functional Module Effectiveness Analysis

4.5.1. Comparison of Module Scores

As shown in Table 9, Outstanding modules:

Table 9.

Functional Module Experience Evaluation.

4.5.2. Behavioral Analysis of Module Use

As shown in Table 10, Behavioral data reveals a complex relationship between experience quality and actual usage.

Table 10.

User Behavior Statistics by Function Module.

This “good experience but hard to use” versus “usable but mediocre experience” paradox highlights a need for functional balance in future design.

5. Discussion

5.1. Restructuring the Experience Model in Digital Environments

This study found that interaction holds the highest weight (44.4%) in the digital experience of cliff inscriptions, significantly surpassing immersion (29.8%), education (13.6%), and aesthetics (12.2%). This order diverges from traditional museum studies, which typically prioritize immersion. Prior research has shown, for example, that ontology-driven conversational systems (such as HeriBot) can significantly boost learning motivation [56], and narrative AR guides enhance knowledge retention more effectively than pure information delivery [44]. However, this study also revealed an internal differentiation within interaction: participation convenience scored high (4.23) while operational diversity was lower (3.92), which aligns with observations that touch interaction is easy but lacks novelty, while in-air gestures offer innovation but impose cognitive load [45]. Thus, future designs should adopt “progressive interaction”: the first layer focuses on ease of use, the second encourages exploration, and the third supports creativity.

5.2. The Paradox of Technological Accessibility and Experience Quality

In the immersion dimension, there is a “high expectation–low achievement” paradox. Handheld AR is susceptible to outdoor lighting conditions [44], while advanced VR remains inaccessible for most due to cost and space requirements. This dilemma appears across multiple studies. International cases suggest that multi-level immersion strategies can address this: high-resolution panoramas cover basic visual experience, WebGL provides lightweight 3D interaction, and full VR is reserved for dedicated users, balancing inclusivity with depth.

5.3. The Value Dilemma of Educational Functions

The education dimension faces a double burden of “low weight + low score” (mean score 3.85), indicating a struggle to balance education and entertainment in current designs. Research on Mazu cultural identity shows emotional identification precedes knowledge identification [57]; MOOC studies also reveal that experience quality influences learning persistence. This suggests a shift from “authoritative narrative” to “multivocal dialogue” [36]: using contextual VR to reconstruct creative scenes, employing AI dialogue systems for personalized Q&A, and building UGC platforms for collaborative interpretation. Design recommendations for the educational function include the following: a layered learning path (micro-scenarios of 1–2 min, thematic bundles of 5–8 min, and deep-dive modules of 15–30 min), task-oriented guidance (clues → light interaction → immediate micro-feedback), and narrative integration (parallel threads of character, event, and place). These recommendations are aligned with the evaluation results of the first-level dimensions and the AHP-derived priorities, and they help enhance perceived educational gains and continuity of engagement under device-access constraints.

5.4. Opportunities in Digital Aesthetics

Although aesthetics had the lowest weight, it scored surprisingly well. This indicates that digital technologies excel at presenting both detail and landscape [35]. However, simple “digital copying” cannot meet the demand for innovation—low innovative expression (3.89) suggests the need for computational aesthetics: applying AI to generate virtual scenes that align with traditional aesthetics, using procedural design and multimedia for ambiance, and utilizing digital means to interpret enduring beauty.

5.5. Innovations and Limitations in Evaluation Methods

The “weight × gap” framework enables the transformation of abstract evaluation into tangible improvement priorities, well-suited for internal project optimization. Compared with AHP-EDAS [51], which focuses on cross-project comparison, this method emphasizes self-iteration; unlike DEMATEL-ANP [48], which accounts for indicator interactions, this method assumes independence—potentially overlooking interrelations; and while it incorporates expert weighting (raising professionalism over pure user evaluations), it may deviate from real user needs. Future research could introduce DEMATEL for causality, fuzzy sets for uncertainty, and machine learning to uncover behavior preferences, as well as dynamic mechanisms to adjust weights in response to user and technical context changes.

5.6. Avoiding a “Purely Objectified” Focus in Practice

Virtualization improves accessibility, but it also risks “pure objectification”: if form and interaction are overemphasized while textual meaning, historical context, and local situatedness are neglected, inscriptions may be reduced to “mere visibles”. Without altering the methods used in this paper (the four dimensions of the experience economy + AHP), subsequent iterations and evaluations can focus on the following:

Education dimension (Understanding): Strengthen the accurate presentation and accessibility of inscription texts and their person–event–time–place relationships, enhancing cultural understanding and mnemonic cues.

Aesthetic dimension (Resonance): Highlight calligraphic style, local imagery, and overall visual character to reinforce the linkage between aesthetic experience and sense of place/belonging.

Immersion and Escapism (Channels): Treat these as channels for meaning transmission; seek a balance between device accessibility and ease of participation to avoid “high immersion–low inclusivity”.

Introduce localized narratives and community ties in moderation, and use standardized mechanisms to showcase audience interpretations, thereby promoting participatory identification.

To further avoid “pure objectification”, educational design should target “identity-relevant meaning-making”: while ensuring factual accuracy, activate cultural memory, local belonging, and participatory identification through accessible presentation of texts–persons–events–places and multivoiced dialogue.

The above aims can be progressively realized—without raising device thresholds—by embedding a layered learning path and task-oriented guidance, complemented by short annotations, contrastive examples, and contextual cues.

Overall, the digital environment prompts three key shifts in the experience economy model:

- (1)

- Decentralized production: Users now both consume and contribute to experience design via interaction, creation, and sharing.

- (2)

- Redefined boundaries: Experiences can take place anytime, anywhere, and are infinitely repeatable and shareable—moving from “peak experience” to “continuous experience”.

- (3)

- Real-time evaluation: Every interaction can be tracked, providing a foundation for precise optimization. The “weight × gap” approach exemplifies this trend.

These findings point to an emerging field—digital experience economics—in which the impact of digital technology on experience ontology, cognition, and methodological tools warrants systematic exploration.

6. Conclusions

Using the digital design of the Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions as a case, this study developed and validated a hybrid evaluation model that integrates experience economy theory and AHP, providing a systematic analysis of user experience in the digital dissemination of cliff inscriptions. The observed “viewing-to-enacting” pattern is case-bound under our current sample (N = 198; 18–35 skew; many occasional users) and should be treated as a working hypothesis requiring cross-case and longitudinal validation. Our main conclusions include the following:

- (1)

- Significant restructuring of the experience model: Interaction (44.4%) ranks first, followed by immersion (29.8%), with education (15.3%) and aesthetics (10.5%) trailing. This demonstrates that in this study’s prototype and sample, users’ experiential focus leans toward a “doing culture” orientation characterized by participation and co-creation.

- (2)

- Paradox between technological novelty and broad accessibility: While advanced AR/VR can boost immersion, device barriers limit their reach. Developers need to balance technological innovation with accessibility to enable broader participation.

- (3)

- Double dilemma in education functionality: The education dimension is both low-weighted and low-scoring, signaling that “edutainment” designs are not yet well executed. Systematic knowledge transmission should be organically embedded within engaging interactions.

- (4)

- Direct channel for optimization via “weight × gap”: The proposed “expert weighting–user quantification–gap analysis” method establishes a seamless path from evaluation to product iteration, efficiently pinpointing and prioritizing improvement areas for agile development.

- (5)

- Three-stage iteration scheme: Based on gap analysis, a three-stage “progressive interaction + tiered knowledge delivery” optimization path is proposed:

Stage 1: Lightweight guided interaction, with simple tasks and prompts to reduce cognitive barriers for new users;

Stage 2: Immersive narrative integration with educational content to strengthen cultural identity;

Stage 3: Ongoing updates to aesthetic displays and real-time feedback monitoring to support long-term engagement and platform iteration.

Theoretically, this study contextualizes the experience economy model for “digital plus immovable” heritage, emphasizing user co-creation and ongoing evolution.

Methodologically, it proposes a closed-loop “expert weighting–user quantification–gap optimization” framework, offering a paradigm for evaluating complex cultural-technical systems.

Limitations include a geographically narrow sample, a short study period, and an emphasis on subjective measures within a prototype context not yet deployed in real-world operations. As a single-case validation, the findings exhibit limited external validity and should be interpreted with caution.

Future work will expand scope and rigor along three axes: Broader coverage and longitudinal design: Conduct cross-site and cross-type comparisons, alongside longitudinal tracking, to examine the temporal stability of AHP-derived weights and score structures and to further assess the grid’s robustness across contexts. Multimodal corroboration: Incorporate behavioral logs and physiological indicators (e.g., eye tracking, electrodermal activity, heart rate variability) under compliance constraints to cross-validate self-report data, improving explanatory power and reproducibility. Methodological enrichment: Retain first-level experience-economy dimensions as core evaluation units and use AHP for prioritization, while adding qualitative instruments and narrative experiments (e.g., targeted open-ended prompts, brief interviews, multi-voiced annotations) to capture identity-related evidence and connect qualitative insights with quantitative results.

Overall, we anchor sustainability in the continuity and contextual adaptability of strategy: first-level dimensions guide evaluation, second-level constructs support design refinement and measurement, and AHP informs priority pathways. This yields a deployable, resource-aware strategy prototype whose claims will be strengthened through multi-case, multi-group external validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and D.L.; methodology, H.W. and H.Y.; software, H.W.; validation, H.W. and X.J.; formal analysis, H.W. and X.J.; investigation, H.W. and X.J.; resources, D.L. and H.Y.; data curation, H.W.; writing original draft preparation, H.W.; writing review and editing, H.W.; supervision, D.L.; project administration, D.L.; funding acquisition, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Shaanxi Provincial Social Science Foundation (Project No. 2023J009) and The Major Project of the Autonomous Region Social Science Foundation, Provincial and Ministerial Level Category A (Project No. 202510120001; Grant No. 2025&ZD016) and The Open Project Program of Key Laboratory of Intelligent and Green Textile, Xinjiang University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study collected fully anonymized questionnaire data without any intervention. According to Article 32 (1)–(2) of the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans (No. 4 [2023] of the National Health Commission), research that uses lawfully obtained public/observational data or anonymized information, without harm to individuals and without involving sensitive personal information or commercial interests, may be exempted from ethical review. Our study meets these conditions; therefore, ethical review was exempted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within this article. The full questionnaire is provided in Appendix A. Given the prototype nature and ongoing research plans, item-level raw data and individual expert matrices are not publicly available. AHP formulas, weighting results, and consistency criteria are reported for methodological transparency.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This questionnaire aims to understand your experience with the prototype of the “Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions Cliff-Carving” digital communication platform. Please answer based on your actual experience—there are no right or wrong answers. Your responses will be kept strictly confidential and used only for academic research. Thank you for your support!

Part I: Demographics

Gender: □ Male □ Female

Age: □ Under 18 □ 18–35 □ 36–50 □ 51 and above

Education: □ High school or below □ Junior college □ Bachelor’s □ Master’s and above

Usage frequency: □ First-time user □ Occasional user □ Frequent user

Part II: Experience Evaluation

Likert 5-point scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree

A. Immersion Dimension (Immersion)

A1 Scene Authenticity

A1.1 The virtual scenes of the Shimen inscriptions provided by the platform make me feel as if I am there.

A1.2 The digitized details of the inscriptions are highly consistent with the real artifacts.

A1.3 The lighting and material effects in the virtual environment enhance the sense of realism.

A2 Sensory Stimulation

A2.1 The platform’s visual effects (color, imagery) left a strong impression on me.

A2.2 The sound design (background music, narration) enhanced my experience.

A2.3 The combination of multisensory elements made the experience more vivid.

A3 Attention Focus

A3.1 While using the platform, I can fully concentrate on exploring the content.

A3.2 The immersive design makes me lose track of time.

A3.3 I am seldom distracted and can focus on the cultural content.

B. Education Dimension (Education)

B1 Knowledge Enrichment

B1.1 The platform helped me learn about the historical background and cultural value of the Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions.

B1.2 I acquired specialized knowledge about cliff-carving art.

B1.3 The information provided expanded my understanding of Hanzhong culture.

B2 Comprehension Ease

B2.1 The platform’s content is organized logically and is easy to understand.

B2.2 Technical terms are explained in plain and accessible language.

B2.3 The layered presentation of information suits users with different knowledge backgrounds.

B3 Learning Effectiveness

B3.1 After learning through the platform, I can remember key historical and cultural information.

B3.2 The interactive learning approach is more effective than traditional exhibitions.

B3.3 The platform’s knowledge quizzes helped me consolidate what I learned.

C. Aesthetics Dimension (Aesthetics)

C1 Visual Beauty

C1.1 The platform’s interface design is elegant and aesthetically pleasing.

C1.2 The digital presentation of the inscriptions showcases their artistic beauty.

C1.3 The overall visual style is coherent and pleasing to the eye.

C2 Cultural Atmosphere

C2.1 The platform’s design fully reflects the characteristics of traditional Chinese culture.

C2.2 The digital presentation of calligraphic art preserves its original cultural charm.

C2.3 The background music and overall atmosphere create a strong sense of historical culture.

C3 Innovative Expression

C3.1 The use of digital technology brings novelty to the presentation of traditional culture.

C3.2 While preserving tradition, the platform incorporates modern aesthetic elements.

C3.3 The innovative presentation methods breathe new life into ancient artifacts.

D. Escapism Dimension (Escapism)

D1 Participation Convenience

D1.1 The platform’s interface is simple and user-friendly, easy to get started with.

D1.2 I can access the platform anytime, anywhere, on multiple devices.

D1.3 One can easily participate without any specialized knowledge background.

D2 Operational Diversity

D2.1 The platform provides various interactive methods for me to choose from.

D2.2 I can explore content at my own pace and according to my interests.

D2.3 Different functional modules meet my diverse needs.

D3 Immediate Feedback

D3.1 Every operation I perform receives a timely system response.

D3.2 The platform provides personalized informational feedback based on my interactions.

D3.3 Real-time interactive feedback enhances my sense of participation and achievement.

Part III: Overall Evaluation

Overall satisfaction: I am satisfied with the platform’s overall experience (1–5 points).

Willingness to recommend: I would recommend this platform to my friends (1–5 points).

Revisit intention: I am willing to use this platform again (1–5 points).

Part IV: Attention Check Item

Please select “Agree” (for data quality control).

Part V: Open-ended Questions (Optional)

Which functional module of the platform do you like the most? Why?

In your opinion, what areas of the platform still need improvement?

Other comments and suggestions:

References

- Su, S.; Chen, Y. A Study on the Statistics and Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cliff Inscriptions in China. Art Obs. 2022, 9, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. A Review of Rock Cave and Cliff Carving Surveys in Sichuan and Chongqing (2011–2020). Sichuan Cult. Relics 2021, 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. Daoist Sculpture of the Song Dynasty Centered on Dazu, Sichuan—A Brief Discussion on Daoist Sculpture in China (VI). Sculpture 2010, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Tang, G.; Yang, H. Analysis of Seismic Technology Application and Evaluation of Applicable Technology in Jianyang–Dazu Area, Sichuan Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2011, 16, 125–138, 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Pan, G.; Lin, B.; Deng, Y.; Chen, W. Archaeological Investigation and Exploration Brief of Guoxing Temple Ruins at Taimu Mountain (2015–2016). Fujian Herit. Mus. 2021, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. Classification, Evaluation, and Development of Tourism Resources in Mount Taimu National Geopark, Fujian. J. Beihua Univ. Nat. Sci. 2015, 16, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Tourism Value of Cliff Inscriptions—A Case Study of Guilin Cliff Inscriptions. J. Guilin Inst. Aerosp. Ind. 2018, 23, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y. Fangcun Archive Rubs Danxia Mountain Cliff Inscriptions in Shaoguan. Lantai World 2010, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Tan, L. Research on Protection Technology for Historical Archives of Minority Cliff Inscriptions in Southwest China. Guangxi Ethn. Stud. 2005, 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Huang, M.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, S. Weathering and Protection Materials of Cliff Inscriptions. Mater. Rev. 2012, 26, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, G.; Li, F.; Xie, M.; Shan, H.; Chen, L.; Li, Z. Application of Surface Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in the Protection of Stone Cultural Relics. Prot. Cult. Relics Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 30, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Yang, W. Analysis of Water Damage Causes and Prevention Strategies for Guihai Stele Forest Cliff Inscriptions. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2020, 47, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Oriental Philosophy in Shimen Han–Wei Cliff Inscriptions. Cult. Relics 1993, 35, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Editor’s Note, Compilation on Cliff Inscriptions of Shimen Thirteen Inscriptions, Baoxie Road. Chin. Calligr. 2017, 19, 64.

- Sun, B.; Weng, Y.; Zhou, X. Application of Remake-Based 2018, 3D Modeling Technology in Digital Reconstruction of Cliff Inscriptions. Prot. Cult. Relics Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 30, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, G.; Chen, W. Research on Web-Based 2021, 3D Architectural Model Visualization Methods. J. Graph. 2021, 42, 823–832. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K.; Liu, M.; Li, Z. Construction Method of Virtual Geographic Environment Based on WebGL Technology. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. 2023, 38, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Qin, L.; Fan, J.; Bi, J. Organization and 2022, 3D Visualization of Navigation Data Based on WebGL. Surv. Mapp. Geogr. Inf. 2021, 47, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Na, J.; Ma, T.; Tang, Y. The Moderating Role of Authenticity between Experience Economy and Memory: Evidence from Qiong Opera. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1070690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Lee, C.-K.; Park, J.A.; Hwang, Y.H.; Reisinger, Y. The Influence of Tourist Experience on Perceived Value and Satisfaction with Temple Stays: The Experience Economy Theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, H. Research on Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Development from an Experience Economy Perspective: A Case Study of Macau. Qinghai Soc. Sci. 2017, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, A.H.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Litovuo, L. Customer Experience in Circular Economy: Experiential Dimensions among Consumers of Reused and Recycled Clothes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinares-Lara, P.; Rodríguez-Fuertes, A.; Garcia-Henche, B. The Cognitive and Affective Dimensions in the Patient’s Experience. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Xie, Z.; Xie, C. Evaluation on the Practice Effects of Experience Economy in Historic Cultural Blocks based on AHP—A Case Study of Sanfang Qixiang, Fuzhou. J. Guizhou Univ. Commer. 2017, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Yin, J. Pre-Evaluation Study of Rural Tourism in Inner Mongolia from the Perspective of Experience Economy. J. Southwest Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 47, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, P. Research on the Needs and Satisfaction of Short Video User-Generated Content. J. Commun. Res. 2021, 28, 77–94, 127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, M.; Bi, X.; Xu, Y. The Impact of Governance Mechanisms on Customer Participation Value Co-creation Behavior: Empirical Study from Virtual Brand Communities. Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Shen, G. The Effect of Virtual Community Sense on Customer Participation Value Co-creation: An Empirical Study from Virtual Brand Communities. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, T.; Yao, J.; Zhu, A. Evaluation and Optimization Path of Horse Culture Tourism Product Experience from the Perspective of Tourists: A Case Study of Zhaosu County, Xinjiang. Hebei Agric. Sci. 2023, 27, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Wang, D. Spatial Consumption Attractiveness of Cultural and Creative Business Complexes: A Case Study of Eslite Bookstore Suzhou. South. Archit. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z. Creative Design and Evaluation of Rural Cultural Heritage Tourism Derivative Products from the Perspective of Experience Economy. Art Panor. 2021, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Design of Ultrasonic Atomizer for Dry Eye Treatment Based on Comprehensive Evaluation Methods. Packag. Eng. 2024, 45, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tan, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, D. Usability Evaluation Study of Smart Car HMI Design Based on AHP-FCE. Packag. Eng. 2024, 45, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, Y.; Elez, J.; Silva, P.G.; Santos-Delgado, G.; Giner-Robles, J.L.; Reicherter, K. 3D Modelling of Archaeoseismic Damage in the Roman Site of Baelo Claudia (Gibraltar Arc, South Spain). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.E. Archaeology and Epigraphy in the Digital Era. J. Archaeol. Res. 2022, 30, 285–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cara, S.; Valera, P.; Matzuzzi, C. 3D Modelling Approach to Enhance the Characterization of a Bronze Age Nuragic Site. Minerals 2024, 14, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J. Digital Dissemination of Intangible Cultural Heritage Driven by Artificial Intelligence. Media 2024, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Feng, Q. Style Capture: Digital Practice of Excellent Traditional Culture Based on Artificial Intelligence Technology. Packag. Eng. 2024, 45, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Shang, S. From Virtual Reality to Augmented Reality: Practical Paths for Legal Program Innovation. China Broadcasting TV J. 2018, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kalfatovic, M.R.; Kapsalis, E.; Spiess, K.P.; Van Camp, A.; Edson, M. Smithsonian Team Flickr: A Library, Archives, and Museums Collaboration in Web 2008, 2.0 Space. Arch. Sci. 2008, 8, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, L.; Paananen, S.; Lengyel, D.; Häkkilä, J.; Toubekis, G.; Talhouk, R.; Hespanhol, L. HCI Advances to Re-Contextualize Cultural Heritage Toward Multiperspectivity, Inclusion, and Sensemaking. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Dong, L.; Shen, X. A Study on the Detection of Weathering in the Yungang Grottoes Using Non-Hermitian Wireless Sensing. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 075021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paolis, L.T.; Gatto, C.; Corchia, L.; De Luca, V. Usability, User Experience and Mental Workload in a Mobile Augmented Reality Application for Digital Storytelling in Cultural Heritage. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 1117–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Hang, L. Influence of Interaction Modes and Gender Differences on Tourist AR Experience. Libr. Inf. Serv. 2021, 65, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Feng, H. Coupling and Coordination Degree of Rural Revitalization Tourism Economy under Entropy Weight Method. J. Southwest Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 47, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jiao, J.; Chang, R.; Chen, B.; Jia, K. Research on Rural Tourism Resource Integration Based on SWOT-ANP Model: A Case Study of Feng County, Shaanxi Province. Land Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hou, J.; Qi, Y. Evaluation of Chinese Tourism Industry Structure Optimization Based on DEMATEL-ANP Model. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2021, 37, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Nie, X. Construction of Competitiveness Index System for Creative Industry Parks in Tourism Culture Based on ANP. Henan Sci. 2013, 31, 2317–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. Evaluation of Island Tourism Competitiveness Based on GEM-ANP Model: A Case Study of Liaoning Province. J. Liaodong Coll. Soc. Sci. 2013, 15, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turskis, Z.; Morkunaite, Z.; Kutut, V. A Hybrid Multiple Criteria Evaluation Method for Ranking of Cultural Heritage Structures for Renovation Projects. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2017, 21, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Tasci, A.D.A. Developing and Validating a Scale to Measure Tourists’ Personality Change after Transformative Travel Experiences. Leis. Sci. 2025, 47, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Gao, W.; Yuan, J. The Sustained Regulatory Effect of Cognitive Reappraisal Based on Implementation Intention on Negative Emotion: Longitudinal EEG Evidence. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2025, 57, 1572–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Xie, J.; Guo, Y.; Xiong, W. Research on Child-Friendly Green Space in Old Urban Areas of Beijing Based on Emotional–Cognitive Health Assessment of School-Age Children. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 41, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Yang, Z. Cold-Escape Tourism Therapy: An EEG Experimental Study of Tourists’ Attention Recovery and Stress Relief. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, M.; De Santo, M.; Mosca, R.; Santaniello, D. An Ontology-Based Chatbot to Enhance Experiential Learning in a Cultural Heritage Scenario. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 808281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzarly, M.; Joshi, M.Y.; Teller, J. A Multidimensional Framework for Assessing Cultural Heritage Vulnerability to Flood Hazards. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2024, 30, 1173–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).