Abstract

Identifying age-appropriate books for children is a complex task that requires balancing linguistic, cognitive, and thematic factors. This study introduces an artificial intelligence–supported framework to estimate the Suitable Age Value (SAV) of Turkish children’s books targeting the 2–18-year age range. We employ repeated, stratified cross-validation and report out-of-fold (OOF) metrics with 95% confidence intervals for a dataset of 300 Turkish children’s books. As classical baselines, linear/ElasticNet, SVR, Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost are trained on the engineered features; we also evaluate a rule-based Ateşman readability baseline. For text, we use a frozen dbmdz/bert-base-turkish-uncased encoder inside two hybrid variants, Concat and Attention-gated, with fold-internal PCA and metadata selection; augmentation is applied only to the training folds. Finally, we probe a few-shot LLM pipeline (GPT-4o-mini) and a convex blend of RF and LLM predictions. A few-shot LLM markedly outperforms the zero-shot model, and zero-shot performance is unreliable. Among hybrids, Concat performs better than Attention-gated, yet both trail our best classical baseline. A convex RF + LLM blend, learned via bootstrap out-of-bag sampling, achieves a lower RMSE/MAE than either component and a slightly higher QWK. The Ateşman baseline performance is substantially weaker. Overall, the findings were as follows: feature-based RF remains a strong baseline, few-shot LLMs add semantic cues, blending consistently helps, and simple hybrid concatenation beats a lightweight attention gate under our small-N regime.

1. Introduction

Reading books strengthens children’s minds, which can yield a host of significant all-around benefits. Most children dive into another world created by blending the book’s fictional world and their own imagination. Spending more time with books can support children in managing their own emotional or psychological problems and offer immense pleasure [1]. Furthermore, books can also contribute to children’s intellectual development and literacy skills [2].

However, it can be hard to obtain these positive results for children’s development unless children encounter books that are suitable for their age. Ensuring children encounter books appropriate to their age level requires expertise in the criteria used in book evaluation and attention. Therefore, librarians and schools might face challenges when they are using the various and sometimes ambiguous criteria identified by domain experts to categorize books or choose books to purchase according to age levels.

There is no consensus on the age limits that define children and childhood. In the “Convention on the Rights of the Child” [3] published in the Official Gazette No. 22184, every individual up to the age of 18 is defined as a child. However, in the literature, the childhood period is variously defined according to the child’s calendar age, age period, class attended, and physical, mental, and psychosocial development [4]. It is divided into stages such as infancy, the preschool period, the school period, and adolescence [5,6]. Moreover, in the literature, there are no clear age limits defining these stages. Some books are categorized by age levels or age ranges, while others are categorized by class levels or class ranges.

Conventionally, determining the appropriate age levels for children’s books relies heavily on the opinions of domain experts, requiring many hours of laborious evaluation. This process is further complicated by the frequent emergence of conflicting expert opinions, as there is no universally accepted formulation or standard for evaluating children’s books. These differences of opinion can lead to inconsistencies, where the same book may be recommended for different reader groups depending on the expert consulted. Such discrepancies can cause confusion for parents, teachers, and librarians, making it challenging to ensure that children are reading age-appropriate material. This lack of standardization highlights the need for a more objective and consistent approach to assessing the suitability of children’s literature.

Within the scope of this study, AI-supported software models were developed to rank children’s books by age. Our AI-supported software models utilize the power of regression models to make an estimation in a continuous age range, and the value thus obtained is called the Suitable Age Value (SAV) metric.

The AI-supported software models developed enable the evaluation of children’s literature in an automatic, systematic, and reliable way regarding age levels, the suitability of the books to the student’s readiness level, and developmental characteristics. The results of this study will hold value for all stakeholders (authors, publishing houses, book-sales platforms, teachers, school/library managers, parents, and students).

This study would impact librarians and their work process by streamlining and enhancing the book-recommendation system for children’s literature. If they can automatically determine the age suitability of children’s books with high precision, librarians can more efficiently and accurately match books to appropriate reader groups. This saves time and ensures that the selected literature meets educational and developmental needs. Additionally, the AI-supported software models provide more reliable and consistent age-range recommendations than traditional methods do; they could thus improve the quality of the library’s offerings and support librarians in their roles as educational facilitators and reading advocates.

In this study, we propose an AI-based approach to estimate the age suitability of children’s books in Turkish. Our contributions include (1) a curated dataset of 300 Turkish children’s books with age labels derived from expert and publisher references, (2) a software pipeline for automated feature extraction tailored to the Turkish language and Turkish literature, and (3) an evaluation of machine learning models and an LLM-based model using OpenAI API [7] to predict Suitable Age Value (SAV). We evaluate both zero-shot and few-shot prompting schemes for GPT-4o-mini, a feature-level hybrid model (frozen BERT embeddings + structured features), and a convex model blending of RF and LLM predictions.

2. Background

Book publishing is increasing every year all over the world. The Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) publishes library statistics annually. According to TUIK 2024 Library Statistics [8], the number of published materials increased by 18.4% in 2023 compared to 2022, reaching 99,025.

It is necessary to evaluate the dynamics of the increase in publications in the realm of children’s literature. According to TUIK 2024 [8], 13% of the published materials in 2023 were in the category of children’s and adolescent literature. Additionally, the number of materials published in the children’s and adolescent literature category increased by 11.3% in 2023 compared to 2022, reaching 13,080.

This upward trend is a positive indicator that can be leveraged to help children develop prosocial reading habits. Books prepared for children, apart from offering children a pleasant and valuable way to spend their time, are also crucial in terms of linguistic, cognitive, social, and personality development [9]. Through books, children not only develop their knowledge of the world, but also develop their sensitivity, imagination, creativity and communication skills. They read about examples of social behaviors and learn to exhibit appropriate behaviors in society [10]. In addition, books offer children the opportunity to use language correctly and with more developed structures.

Of note, Çiftçi [6] states that reading is not a haphazard activity; it is an acquired and essential skill, and given this point, there is a need for children’s literature that can make reading more meaningful. The concept of children’s literature also has a periodic nature. Güleryüz [11] emphasized that childhood is composed of stages, from infancy to adolescence, and that children in each period should have suitable books. Otherwise, Çiftçi [6] warns, age-group mismatch can be devastating and alienating.

In light of this information, the target age group’s characteristics should be considered while the author is writing, when teachers and librarians are choosing books for students, and when publishing houses are shaping a book to be published. In the literature, these features are discussed in two main categories: “external structure (formal)” and “internal structure (content)”. It is important to consider both the internal and external structural characteristics of literary works when introducing children to books that match their interests, needs, and developmental characteristics [12]. Libraries, in their role as gatekeepers of knowledge and culture, must also ensure that the books they offer align appropriately with these structures to support the educational and developmental needs of young readers.

2.1. Internal and External Criteria for Books

Studies focused on determining the criteria that define the internal and external structures of children’s books and on evaluations based on these criteria have gained momentum since 2000.

In general, the external structure criteria are items such as size (dimensions), paper quality, page layout, font size, suitability of the pictures used, and cover (binding); the internal structure criteria comprise items such as theme, plan, subject, language, and expression (sentence structure, presence of foreign words, etc.).

Demircan [13] evaluates 36 children’s books (for children 7–11 years old) and states that a book’s font size should be greater than twelve points for first-, second- and third-grade primary-school students, while ten-point font size can be used for readers in the fourth and fifth grades. The author stated that in terms of language and style, which are among the internal structure criteria, paragraphs should not exceed three to five sentences, the language should be modern, and foreign words should not be included.

Orhan and Pilav [14] recommended sentences be three to five words (20–30 characters) for children aged 2–7 years, six words (35–40 characters) for children in grades one to three, and a maximum of ten words (60–70 characters) for children in grades four to five. They determined that the line lengths in the book should be 7–8 cm for children in grades one to five and 9–11 cm for more advanced grades.

Apart from the suggestions in the studies mentioned above, Çiftçi [6] also underlined that there are many different approaches in the literature on children’s books to assigning books and their characteristics to age groups. In this context, he drew attention to the necessity of establishing common criteria in the form of quality standards with the participation of all stakeholders.

2.2. Identified Problems and Problem Areas Highlighted in the Literature

Many popular online bookstores divide children’s books into age categories. As most children’s books do not have age labels on them, it is unclear according to which criteria the age-group labels are made by the online bookstores. In addition, the age categories in each online bookstore are different. To give an example, children’s books have been classified in online bookstores as follows:

Kitapyurdu website [15] :

- Pre-school

- 6–12 Years

- 12+ Years.

D&R website [16] :

- Pre-School 6 Months–5 Years,

- School Age 6–10 Years,

- Youth 10+ Years.

Bkmkitap website [17] :

- 0–3 Years,

- 4–5 Years,

- 6–7 Years,

- Children’s Primary School,

- Youth Secondary School,

- Youth High School.

For example, “Korsan Okulu - 5: Hücum!” is presented in the “6–12 Ages” category on the Kitapyurdu website [15], in the “6–10 Ages” category on the D&R website [16] and in the “Novel” category on the Bkmkitap website [17]. Another example is “Sketty and Meatball”, which is tagged as being for "Ages 6 to 7" on the Toronto Public Library website [18], but as being for 4–8-year-olds on the Amazon website [19]. Many other children’s books are also presented in different age categories in different online bookstores or libraries. Moreover, for many books, there is no information about the age group on the cover and tag of the book or on the publisher’s website.

These differences complicate the work of authors and organizations such as publishing houses, families, teachers, and libraries who choose books for children. Discrepancies in age categorization can lead to confusion and potential misselection, providing books that are either too advanced or too simplistic for the intended reader. Librarians and bookstore staff might face challenges in cataloging and recommending books accurately.

3. Related Work

Those studies that use machine learning methods to assess children’s books operate from various perspectives. Existing studies mainly focus on classification tasks intended for different purposes that are developed using children’s literature as a dataset. The studies present innovative research that explores how machine learning algorithms are developed to classify and recommend books.

Researchers from the National University conducted a study [20] to create a machine-learning model that could classify the readability levels of Filipino children’s literature. Their goal was to develop a reliable system that can automatically identify the appropriate reading levels, by grade, for books written in Filipino. As their dataset, they employed 258 picture books that were divided into grade levels 1–10 by reading specialists. Three techniques were used in the study: Random Forest, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Multinomial Naive-Bayes. Using count vectors, they found that the Random Forest algorithm performed better than the other techniques, attaining a high accuracy of 0.942. With count vectors, the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm also fared well, attaining an accuracy of 0.857 in one case. Meanwhile, trigrams proved to be the most effective combination for the Multinomial Naive-Bayes algorithm, producing an accuracy of 0.61.

Chatzipanagiotidis et al. [21] investigate the readability classification of Greek textbooks, focusing on their suitability for different educational levels and proficiency groups, particularly for students classified as Greek as a Second Language (GSL) learners. Using data from five Greek text corpora and linguistic complexity features, the classification experiments utilized WEKA [22] to compare various machine learning algorithms, such as Logistic Regression, Multilayer Perceptron, and Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO). Among these, the SMO classifier delivered the best performance. The results of the study include findings that combining linguistic features enhances classification accuracy, with the GSL corpus achieving the highest accuracy (88.16%). The study concludes that incorporating diverse linguistic features advances readability classification.

Dalvean et al. [23] introduce a new method for determining the reading complexity of fiction texts to aid English teachers in selecting appropriate reading materials for students. Using a corpus of 200 fiction texts (100 children and 100 adults), the study used WEKA for logistic regression modeling, achieving 89% accuracy in classifying text complexity.

In another study, Niksarli et al. [24] present work on developing an artificial neural network (ANN) to classify books based on their appropriateness for middle-school students. The study utilizes natural language processing (NLP) techniques, sentiment analysis, and a newly created dataset to train the ANN. The researchers create a unique dataset containing 416 books, including books that are both suitable and unsuitable for middle-school children. Their ANN model demonstrated a high accuracy of 91.2% in detecting appropriate books and 80.7% accuracy in identifying inappropriate books.

Singh et al. [25] present a machine learning-based system designed to provide personalized book recommendations for young readers by considering both the content of the books and the age of the readers. Books were categorized into specific age groups: children, teenagers, and young adults. Combined features were created by consolidating the book’s name, age category, author, and genre. The study employed several machine learning algorithms, including K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree, and Naive Bayes. The models were evaluated based on their execution times and accuracy in providing book recommendations.

Denning et al. [26] introduce TRoLL (Tool for Regression Analysis of Literacy Levels), a tool designed to predict the readability levels of K-12 books written in English using publicly accessible data. The researchers utilized metadata such as subject headings, book and author information, and content-based predictors (when text snippets were available), including counts of long words and sentences, as well as total word count and letter count. TRoLL implements multiple linear regression to analyze these predictors and estimate readability levels. In comparison with existing tools, TRoLL outperformed traditional readability formulas (Coleman–Liau, Flesch–Kincaid, Rix, and Spache) as well as popular tools like Lexile and Accelerated Reader (AR).

Sato et al. [27] present a method for assessing the readability of Japanese text from 127 textbooks. The total corpus is divided into thirteen grade levels (1–12, with university level as the thirteenth grade). Their method for readability measurement is based on character-unigram models, which calculate the likelihood of a text belonging to a specific grade level. In the readability-estimation process, they use conditional probabilities for operative characters (Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji) calculated for each grade level. The log-likelihood of a given text is computed for each grade, and the grade with the highest likelihood is assigned as the readability level. Their method achieved a 39.8% accuracy for exact grade-level classification and 73.8% accuracy if one allows for an error of plus/minus one grade level.

While most existing studies have focused on feature-based machine learning pipelines, recent developments in natural language processing have led to the adoption of deep learning and large language models (LLMs) for readability prediction. A recent study [28] introduced a reading bot that supports guided reading using NLP techniques such as word-sense disambiguation, question generation, and text simplification, which was tested on 28 English articles (A2–B2 level). Their system achieved up to 93% accuracy in word-sense disambiguation and generated mostly fluent and relevant questions. Maddela et al. [29] used transformer models for simplification of English texts, showing that LLMs are capable of capturing complex syntactic and semantic structures relevant to age-appropriate language.

Recent work has examined multilingual and cross-lingual evaluations of readability with large language models and modern encoders. ReadMe++ introduces a multilingual, multi-domain benchmark and shows that LLMs capture readability across Arabic, English, French, Hindi, and Russian, highlighting cross-lingual trends and limits [30]. Complementing this, an open multilingual readability-scoring system demonstrates practical pipelines that combine BERT-style embeddings with engineered features [31].

On the modeling side, prompt-based/LLM-derived difficulty metrics significantly improve difficulty classification over static formulae, indicating that few-shot conditioning can inject high-level discourse and topic cues [32]. Prior age-recommendation work in French [33] frames the task as interval regression with CamemBERT fine-tuning and expert comparison. Our finding that few-shot conditioning outperforms a zero-shot approach aligns with progress in few-shot metric learning [34], which aims to learn richer representations under sample scarcity. Encoder-only, attention-guided transformer frameworks demonstrate strong deep representations and high explainability in classification, offering a conceptual backdrop for our frozen-BERT/LLM components, which we directly compare with stable, feature-based regressors [35].

Despite this promise, the application of LLMs to Turkish children’s literature remains largely unexplored. Most prior work has focused on high-resource languages or datasets with limited narrative structure. Our study addresses this gap by not only evaluating classical regression models, but also integrating a GPT-4o-mini-based implementation from Turkish-language text inputs. GPT-4o-mini’s robust multilingual capabilities allow us to process Turkish input without translation. Furthermore, we implemented model blending by using Random Forest and LLM and feature-level hybrid modeling by combining textual representations (embeddings) of each book with extracted features.

3.1. Summary of Differences and Contributions

Table 1 summarizes how the proposed framework differs from representative prior works in the field of readability and age-estimation modeling. Unlike earlier studies that mostly address grade-level classification or rely solely on surface linguistic metrics, our framework performs continuous Suitable Age Value (SAV) regression with a leakage-safe repeated 5 × 5 CV protocol, integrates few-shot large language model prompting, and introduces a convex Random Forest + LLM blend that leverages complementary structural and semantic cues.

Table 1.

Comparison of our framework with representative prior studies on readability, age estimation, and related LLM/NLP systems.

This comparison highlights the novelty of our approach in several aspects:

- Focusing on continuous age prediction rather than discrete level classification,

- Ensuring leakage-safe repeated 5 × 5 cross-validation with out-of-fold confidence intervals,

- Integrating few-shot LLM prompting and a convex Random Forest + LLM blend optimized via bootstrap OOB, and

- Including a rule-based Atesşman baseline for fair comparison.

3.1.1. Methodological Rationale (Advanced Models in Data-Centric Settings)

Beyond domain-specific readability studies, our evaluation aligns with a broader body of evidence in data-centric, technically constrained environments: on small-to-moderate datasets with heterogeneous, structured features, tree ensembles (e.g., Random Forest/XGBoost) often provide strong, stable baselines, while LLMs contribute complementary semantic signals not captured by surface or metadata features. This motivates our triangulated comparison, which includes advanced classical baselines, frozen-encoder hybrids (BERT embeddings + metadata), and a convex RF + LLM blend, all under a leakage-safe repeated CV protocol. Our findings empirically support this rationale by showing (i) a strong RF baseline, (ii) significant gains from few-shot vs. zero-shot LLM prompting, and (iii) consistent RMSE/MAE improvements from blending, with maintained QWK (see Section 4 and Section 5).

3.1.2. Methodological Background on Advanced Model Contrasts

Recent comparative studies in data-centric and technically constrained environments have demonstrated that classical tree-based models remain strong baselines even when evaluated against deep neural architectures. Grinsztajn et al. [36] showed that Random Forest and XGBoost models consistently outperform deep learning architectures across a wide range of tabular datasets under typical sample sizes (below 10K). Similarly, Rana et al. [37] and Shmuel et al. [38] provided comprehensive benchmarks indicating that tree ensembles often achieve higher stability and interpretability compared to neural networks in industrial data analysis. Complementarily, Wydmański et al. [39] introduced a hypernetwork-based deep learning framework (HyperTab) designed for small tabular datasets, which demonstrated performance competitive with tree ensembles. In parallel, recent hybrid-learning surveys [40] have emphasized the growing trend of combining traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques to leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms. Our study builds directly on these findings by contrasting Random Forest and LLM/BERT-based models under identical cross-validation protocols and by proposing a convex blend (RF + LLM) that embodies these hybridization principles.

4. Methodology

The automatic grading of the content of books before they are published using artificial intelligence models developed within the scope of this study will answer the research question below.

Research Question: How can an artificial intelligence model be created that uses internal and external structure attributes to provide age grading of children’s books?

This applied research study aims to solve the problems encountered in evaluating Turkish children’s literature. It is envisaged that software using artificial intelligence models, which is the output of this study, can become a standard tool for printing children’s books. Considering the high volume of children’s books produced every year and the necessity for a practical and fast process of review and evaluation, it is believed that labeling books by age category will contribute to improving their quality and facilitating book selection. It will positively contribute to the education system by preparing the ground for an increase in reading enthusiasm and turning reading into a habit. Furthermore, consistent age recommendations can prevent libraries from misclassifying books; this is an error that causes readers difficulties in finding suitable books. The steps to be taken to achieve this end are listed below.

- Step 1: Determining the attributes to be used in the age grading of children’s books.

- Step 2: Development of feature-extraction software and creation of datasets for artificial intelligence models.

- Step 3: Development of artificial intelligence models to determine SAV (Suitable Age Value) metrics for children’s books.

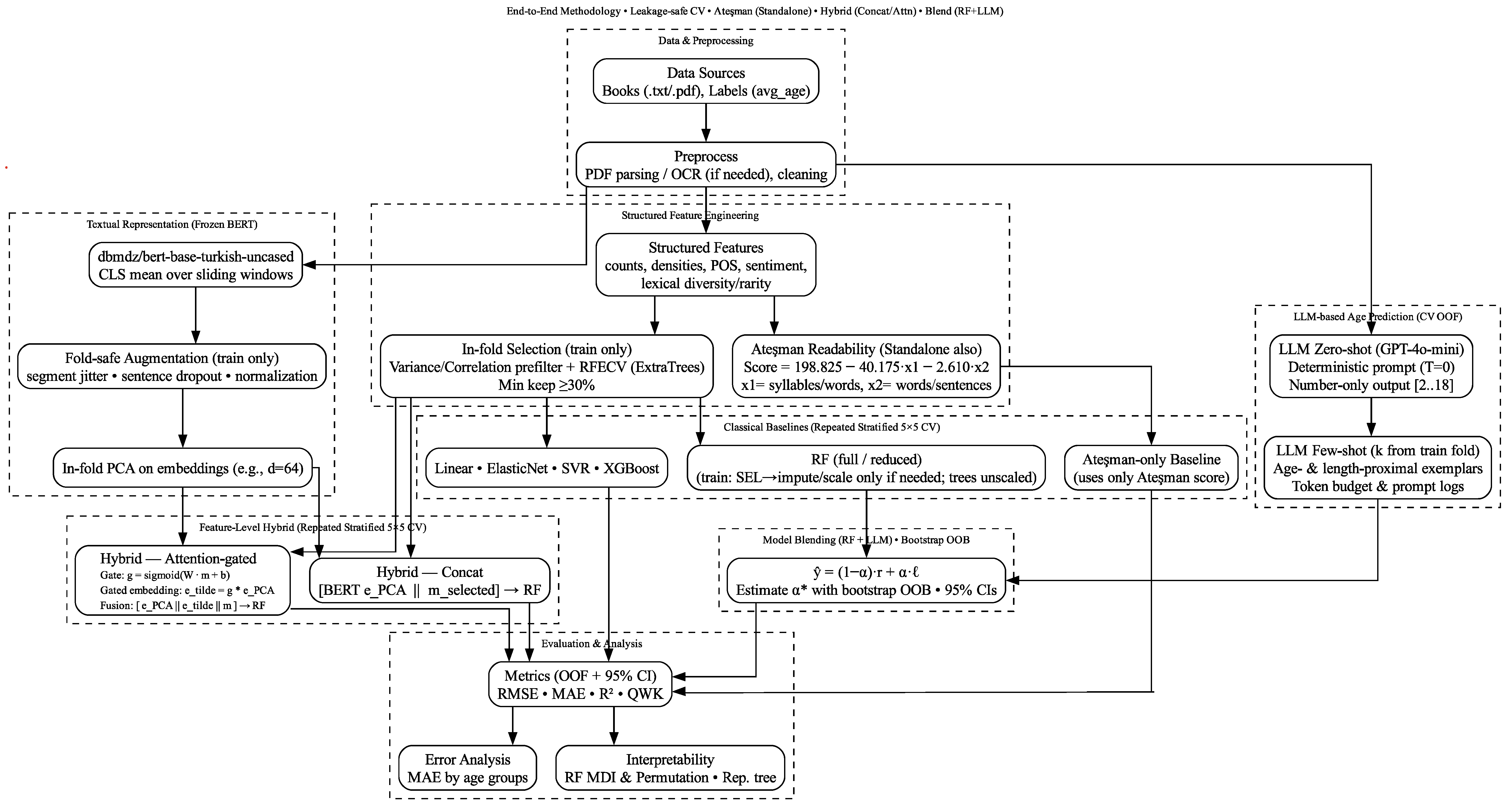

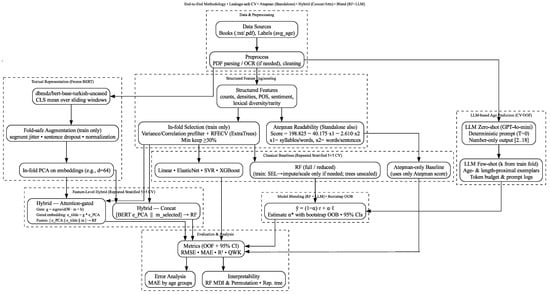

Figure 1 summarizes our end-to-end pipeline, which was followed in direct support of the study’s research question. The flowchart includes (i) leakage-safe data preparation and structured/LLM routes, (ii) classical baselines, (iii) LLM-based prediction, (iv) feature-level hybrids (Concat, Attention-gated), and (v) RF + LLM blending, together with (vi) evaluation and interpretability. We also highlight Ateşman readability both as a feature within the structured branch and as a stand-alone baseline. This design targets scalability and standardization in pre-publication age grading, aiming to improve selection quality for educators, publishers, and libraries by enabling fast, consistent recommendations across the 2–18-year range.

Figure 1.

End-to-end flowchart showing the methodology.

4.1. Determining the Attributes to Be Used in the Age Grading of Children’s Books

The attributes that should be decisive in the age rating of a children’s book have been studied extensively in the literature. In this framework, two main categories are used: internal structure and external structure. Each of these main categories also has its own sub-dimensions: Design and Arrangement and Author and Book Information for external structure and Language and Expression, Subject-Plan, and Illustration for internal structure. Each sub-dimension also encompasses various attributes [13,14,41]. The features used/recommended by different researchers in their studies were compiled within the scope of this goal, and a comprehensive and detailed feature scheme [42] was created.

According to the preliminary studies carried out for this study, the features obtained from children’s books can be grouped into three different groups. In the first group, key features are available directly from the book’s digital edition. It has been observed that these are mainly external structure attributes, such as page size, font size, number of pages of the book, line spacing, etc.

Some features in the second group can be calculated with standard approaches. For instance, such attributes include the total number of words, the total number of unique words, the average number of words per page, and the particular types of words used (noun, adjective, verb, adverb, preposition, etc.).

The last group consists of features that can be calculated as a function of the features in the first two groups. These calculations will be based on studies in the literature. While the lexical diversity attribute is obtained by dividing the number of unique words by the total number of words, the lexical density attribute is obtained by dividing the number of words of a particular type (e.g., adjective) by the total number of words. We used a list of frequently used words to calculate the distribution of lexical rarity in Turkish children’s literature. Specifically, we took the first one thousand most frequently used words in Turkish from the Turkish National Corpus [43]. We then compared the vocabulary of the children’s book texts we examined with this list of common words. Finally, we calculated the rate at which these frequently used words appeared in the texts.

In the literature, multiple methodologies for the calculation of some features have also been observed. The readability metric naturally has different computational approaches for each language [44]. The readability score, calculated with the Readability Formula proposed by Ateşman, was used in this context [45]. The constants in this formula were empirically derived by Ateşman through adaptation of the Flesch Reading Ease formula to the morphological and phonetic characteristics of the Turkish language. This includes adjustments for average syllables per word and average sentence length, which are known to affect perceived difficulty in Turkish differently compared to English. The formula is as follows:

where refers to the total syllables divided by the total number of words, and refers to the total number of words divided by the total number of sentences.

In addition to general linguistic and structural features, we also incorporated several attributes tailored specifically to the Turkish language. For instance, inverted sentence structures, which are relatively common in Turkish due to its flexible subject–object–verb (SOV) syntax, were counted separately from regular sentence structures. We also computed lexical rarity based on the frequency of words in the Turkish National Corpus [43], allowing us to detect the use of advanced or uncommon vocabulary. Furthermore, idiomatic expressions, a notable aspect of Turkish children’s literature, were identified and quantified, as their presence often correlates with more advanced age levels and abstract thinking.

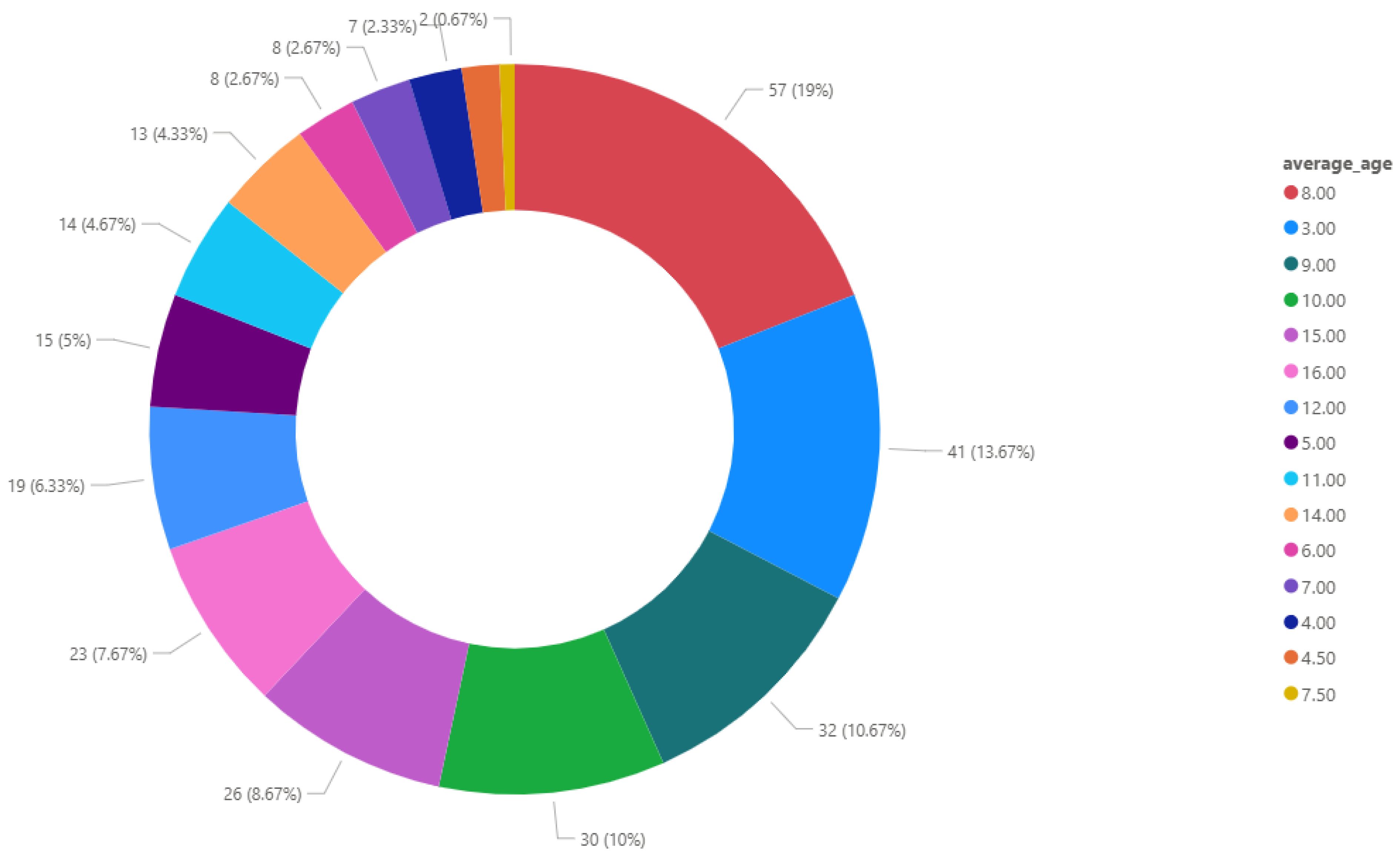

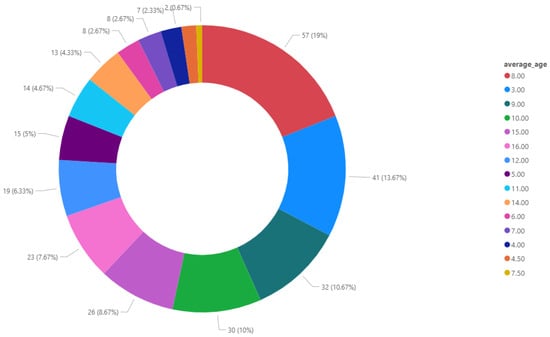

Since there is no existing dataset of Turkish children’s books, we needed to create our own for this study. To this end, children’s books available in online bookstores were purchased to create a dataset. Books for which this was not possible or for which no digital version (e-pub) exists were used in scanned form. To create a target age value to be used in machine learning models, average age values were calculated according to the age range determined by publishers/bookstore categories. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of age values in our book corpus of 300 books.

Figure 2.

The distribution of age values in our book corpus.

4.2. Feature Extraction and Dataset Construction

After the desired features had been identified, the next step was to develop a method for automatically extracting them from the books. To achieve this, a software system was built using well-established Python (Version:3.12.1) libraries for text processing. In particular, the spaCy [46] natural language processing library was utilized, along with its “tr_core_news_trf” model [47], which is a transformer-based Turkish-language model built on the BERT architecture. This model enabled the extraction of linguistic features such as tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, and named-entity recognition. Additionally, the PyMuPDF library [48] was used to parse and extract text from PDF files, allowing for efficient processing of both digital and scanned books.

For sentiment analysis, a pre-trained BERT-based Turkish sentiment model [49] was employed. The model was integrated using the AutoModelForSequenceClassification class from the Hugging Face Transformers library, allowing for automatic classification of Turkish sentences based on sentiment polarity.

The feature set was derived from the existing literature on analysis of children’s books. First, we used all extracted features in the initial training phase. In addition to using all extracted features, we further applied a two-step feature-selection process within each CV fold: (i) variance/correlation-based preprocessing on the train fold; and (ii) RFECV with ExtraTrees, also only on the training data, retaining at least 30% of the features. Selection was performed independently in each fold (no data leakage). Within each CV fold (training portion only), we applied variance/correlation prefiltering followed by RFECV, reducing the 19 attributes to a median of 9 (IQR 6–14). After each fold, a Random Forest model was trained and evaluated on the validation set. Additionally, feature importance was reported using both tree-based MDI and model-agnostic permutation importance methods [50]. While alternative methods such as LASSO regression could also be employed, our selection pipeline provided sufficient complexity reduction without sacrificing predictive performance.

The process of extracting the features in the books began only where the story began in the book. Sections that are not related to the story, such as book-cover information, author biography, and publisher information in the book’s introductory pages, were not included. Table 2 describes each attribute derived from the books and used in machine learning models (Target label was not used as a feature.).

Table 2.

Attributes used in machine learning models.

Structured features, as defined in Section 4.1, were systematically extracted from each book to construct a comprehensive dataset. This dataset encompasses both low-level linguistic attributes (e.g., sentence length, word count) and higher-order textual metrics (e.g., readability scores, lexical diversity). For each book, the age label was determined by calculating the average of all the age-range endpoints provided across multiple bookstores to mitigate source bias. Although this averaging introduces some uncertainty for books with wide ranges, the resulting distribution (Figure 2) remained well balanced across the 2–18-year scale. Stratification in the repeated cross-validation was applied on the integer-rounded SAVs to ensure proportional representation of both narrow and broad intervals. This average is used as the target Suitable Age Value (SAV) for regression modeling. Together with the corresponding SAV labels, these features constituted the final dataset used for training and evaluating the machine-learning models presented in the subsequent section. This feature-engineering pipeline ultimately facilitated the development of a labeled dataset tailored for age prediction through artificial intelligence-based techniques.

4.3. Developing Machine Learning Models

Within the scope of Step 3, several machine learning models for regression were developed to calculate the SAV metric for children’s books that yielded the highest performance using the labeled dataset.

Different approaches are used to produce a regression model in the literature and in practice. For example, a simple linear regression model tries to describe the obtained data with a single linear function. As might be expected, such a model can be calculated quickly and easily; however, it cannot successfully solve many problems due to its strict conditions (such as absolute independence between features) and inadequacies, such being restricted to finding only one linear function. For this purpose, more advanced modeling techniques have emerged in the literature. The most important of these, which were studied within the scope of this study, are machine learning models.

Machine learning models try to describe the obtained data using linear or non-linear curves. Since they can process more than one curve and more than one section of the data simultaneously, they can learn and define more complex data.

Linear Regression, ElasticNet Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and XGBoost Regression were employed as machine learning models for regression modeling.

4.3.1. Evaluation Protocol and Preprocessing

To address small-N stability, we report all classical baselines using repeated, stratified -fold cross-validation (25 validation folds in total), stratifying by integer-rounded SAV in . Within each training fold only, we apply inverse age-bin frequency sample weights (Linear/ElasticNet/RF/XGBoost) and row oversampling for SVR; validation folds remain untouched. Preprocessing is implemented with scikit-learn [51] Pipelines to prevent leakage: SimpleImputer (strategy=median) for all models and StandardScaler only for Linear/ElasticNet/SVR; tree ensembles (RF/XGBoost) are left unscaled. We report fold-aggregated means and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI).

4.3.2. Model Families and Hyperparameters

We evaluate Linear Regression, ElasticNet (, ratio = ), SVR with RBF kernel (, ), Random Forest (, max_features = sqrt, bootstrap), and XGBoost (, max_depth = , learning_rate = , subsample = , colsample_bytree = , tree_method = hist).

4.3.3. Two-Stage Feature Selection (CV-Internal)

Classical models use a two-stage selection inside each training fold to avoid leakage: (i) a prefilter comprising VarianceThreshold and correlation with the target ( ≥ corr_threshold); and (ii) RFECV with an ExtraTreesRegressor ( trees), inner CV = 3, and a minimum retention of min_features_frac = . All selectors are fit on the training fold only ; validation folds are never used to choose features. After selection, a Random Forest is fit on the reduced set and we compute feature importance via both tree-based MDI and model-agnostic permutation importance (on the validation fold).

4.4. LLM-Based Age Prediction

To complement the feature-based baselines, we implement an LLM pipeline that predicts the Suitable Age Value (SAV) directly from text using GPT-4o-mini. The entire evaluation follows a repeated, stratified cross-validation protocol (25 folds). For each validation item, we construct a deterministic prompt, obtain the model’s numeric age prediction, and aggregate out-of-fold (OOF) predictions to compute metrics.

4.4.1. Input Preparation and Token Budgeting

For each book, we read a TXT file or (if available) extract text from a PDF. A single target excerpt is formed by truncating the raw text to a token-budgeted limit. In few-shot mode, we additionally include k labeled exemplars (excerpt + gold age) taken only from the training fold. Budgets are computed so the full prompt stays within a configured limit (max_prompt_tokens = 6000, with 10 tokens reserved for the response), using a conservative character-to-token ratio (chars_per_token = 4.0). We allocate ≈ of the prompt tokens to the target excerpt and ≈ to exemplars (split across k). Our code enforces practical min/max char bounds to avoid very short/very long snippets.

4.4.2. Prompting

We use a fixed system prompt that frames the task as predicting a reader age and instructs the model to return only a number between 2 and 18.

System prompt (English): “You are an expert assistant that predicts the suitable reader AGE for Turkish children’s books.” “Return ONLY a numeric age between 2 and 18 (decimals allowed), with no words, symbols, or explanations.”

Zero-shot uses a simple user prompt containing the target excerpt and the same “number-only” instruction. Few-shot augments the user prompt with an exemplar block: each exemplar is rendered as “Example i-GOLD LABEL AGE: a” followed by the exemplar excerpt. Temperature is fixed at 0.0 for determinism.

4.4.3. Exemplar Selection (Few-Shot)

Within each CV fold, exemplars are drawn only from the training portion to prevent leakage. We sort candidates by age proximity to the target, break ties by length proximity, and apply a per-age cap to maintain diversity across the label range. The top k items (default ) are inserted into the prompt. This procedure yields age-proximal, length-compatible guidance while preserving reproducibility.

4.4.4. Decoding and Post-Processing

The model’s response is parsed to extract the first numeric value. Predictions are clipped to [2, 18] and stored as continuous ages. (When a response is malformed, a bounded retry policy is used; failures are logged and skipped to avoid biasing results.) All calls are cached to ensure identical results under re-runs.

4.4.5. Cross-Validation Protocol

For each repeat/fold, prompts for the validation set are built using only training-fold information (text excerpts, exemplars, and budgets). This produces OOF predictions for every item. We then report metrics as the mean (and, where applicable, confidence interval) across the 25 folds.

4.4.6. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate four complementary measures:

- RMSE (root mean squared error):which penalizes large errors more heavily; lower is better.

- MAE (mean absolute error):directly interpretable in “years of age”; lower is better.

- (coefficient of determination):measuring explained variance (can be negative); higher is better.

- QWK (quadratic weighted kappa): agreement on integer-rounded predictions vs. integer labels, weighting disagreements quadratically across the [2, 18] scale; higher is better.

RMSE/MAE quantify absolute error in continuous age prediction; summarizes explained variance; QWK evaluates ordinal agreement after rounding and is useful because downstream stakeholders often use whole-year categories.

4.5. Model Blending

We investigated whether predictions from a Random Forest (RF) and a Large Language Model (LLM) could be combined to improve age estimation. Let be the RF prediction and the LLM for item i. A convex blend is defined as

We evaluate two RF variants: (i) RF (full) trained on all 19 engineered features; and (ii) RF (reduced) trained on the CV-internal two-stage selection (variance/correlation prefiltering + RFECV), yielding a median of nine features (IQR 6–14)—i.e., ≈ dimensionality reduction without material loss of accuracy.

4.5.1. Diagnostic -Sweep

To illustrate the impact of different weights, we sweep and report RMSE, MAE, and QWK. These curves indicate where the blend benefits most from LLM vs. RF.

4.5.2. Selection-Free Performance via Bootstrap Out-of-Bag (OOB) Sampling

To obtain an unbiased estimate of blending performance, we apply a bootstrap-OOB protocol over the cross-validated OOF predictions (from repeated, stratified CV). For each of B resamples:

- 1.

- Sample n indices with replacement to form an in-bag set; the complement forms the OOB set.

- 2.

- Fit the blending weight on the in-bag set by minimizing mean squared error (MSE). The closed-form solution iswhere y are the ground-truth labels and projects to . A small denominator triggers a fallback (e.g., ) to ensure stability.

- 3.

- Evaluate the blended predictor on the OOB set and record all metrics (QWK is computed on rounded, clipped ages in to respect the label space.).

We report bootstrap means and percentile intervals across OOB resamples, along with the distribution of values. Importantly, is never tuned on the items used for evaluation within each replicate, providing a selection-free assessment; the grid sweep is presented for illustration only.

4.6. Feature-Level Hybrid Modeling

We construct hybrid regressors that combine a textual representation with structured meta-features. Text is encoded using the pretrained Turkish model dbmdz/bert-base-turkish-uncased; the Transformer is kept frozen for reproducibility and small-N stability [52].

4.6.1. Book Embeddings

Each book is split into overlapping segments of at most wordpieces with stride . For segment t, we take the hidden state and obtain a book vector by mean pooling across T segments:

(Mean pooling over token embeddings produced the same conclusions.)

4.6.2. Fold-Safe Dimensionality Reduction (Text)

To mitigate redundancy, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is fit inside each training fold and projects to components, yielding .

4.6.3. Fold-Safe Selection (Metadata)

Handcrafted features (counts, densities, readability, sentiment tallies, etc.) are reduced by Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) using an ExtraTrees regressor, again fit inside each fold. A minimum keep fraction of 30% is enforced. Across the protocol, the median number retained was 9 (IQR 6–14), i.e., ≈ reduction without loss in accuracy (see Section 4.3).

4.6.4. Data Augmentation

Given , we regularize the text encoder by fold-safe augmentation that does not alter labels: (i) segment jitter (randomized segment start offsets), (ii) sentence dropout (Bernoulli removal with ), (iii) orthographic normalization (lowercasing, punctuation/space canonicalization). Augmentations are applied only on the training portion of each fold; the validation items are kept original. Embeddings from multiple augmented views of the same book are averaged before PCA, which stabilizes while keeping the evaluation protocol unchanged.

4.6.5. Hybrid Head

Unless stated otherwise, the fused representation is regressed by a Random Forest (RF) with tuned hyperparameters (bootstrap on, max_features=sqrt, n_estimators selected inside CV).

4.6.6. Hybrid—Concat, Augmented, Repeated CV (5 × 5)

The reduced embedding and the selected metadata are concatenated:

and fed to the RF regressor. All preprocessing (augmentation, PCA, RFECV) is performed inside folds, and evaluation uses repeated, stratified CV with out-of-fold (OOF) aggregation.

4.6.7. Hybrid—Attention-Gated, Augmented, Repeated CV (5 × 5)

To move beyond simple concatenation, we adopt a lightweight attention-gated fusion that learns how strongly the textual representation should contribute given the metadata. Inside each training fold, we fit a small logistic “gate” from metadata to the text space:

where is the elementwise sigmoid, , and are learned with regularization (Ridge objective) on the training fold only (We also evaluated a scalar gate ; results were similar). The final fused vector concatenates gated and raw views:

and is passed to the same RF head. Intuitively, g upweights components of the textual embedding that are predictive given the current metadata, providing an attention-like feature weighting without training the Transformer. Because are fit per-fold and applied to that fold’s validation items only, leakage is avoided.

4.6.8. Protocol and Metrics

Both hybrids use the repeated, stratified CV protocol. We report RMSE/MAE, , and QWK on integer-rounded predictions. Hyperparameters for RF and the gate’s ridge penalty are selected by inner CV on the training fold (grid over ). All stochastic steps use fixed seeds for reproducibility.

This advanced-model contrast (RF/XGBoost vs. frozen-BERT hybrids vs. few-shot LLM and their convex blend) follows best practices for data-centric industrial/technical settings, small-N, heterogeneous feature spaces, and strict anti-leakage evaluation, providing a principled basis for our downstream comparisons and conclusions (see Section 5).

4.7. Rule-Based Readability Baseline (Ateşman)

To contextualize the ML/LLM models with a traditional readability tool, we add a rule-based baseline built on Ateşman’s readability formula for Turkish, as described in Section 4.1. Higher values indicate easier texts.

4.7.1. Fold-Safe Estimation

We compute the Ateşman score directly from the raw text (PDF/TXT). To put this baseline on the same footing as our regressors, we fit a univariate mapping from Ateşman to the target age within each training fold only and evaluate on that fold’s validation items. Concretely, we use a simple linear regression Ateşman, with estimated in-fold. This avoids introducing external heuristics for “grade bands” while ensuring a fair, leakage-safe comparison.

4.7.2. Protocol and Metrics

The baseline is evaluated under the same repeated, stratified cross-validation as our other models, stratifying by the integer-rounded label. We report RMSE, MAE, , and QWK (on integer-rounded predictions). Confidence intervals (95%) are computed by percentile bootstrap over the 25 out-of-fold (OOF) folds.

4.7.3. Interpretation

This baseline isolates how far a single scalar readability signal can go towards predicting suitable reader age. In our setting with diverse structural cues (sentence/word distributions, densities) and semantic variation, we expect the feature-based RF and the hybrid/LLM models to outperform the Ateşman-only regressor; nonetheless, including it strengthens the claim that ML/LLM methods provide substantive improvements over legacy readability tools by capturing non-linear interactions and semantics beyond surface difficulty.

5. Results

In this section, we present the results of the evaluation of various regression models trained to predict the SAV of Turkish children’s books.

Table 3 reports that Random Forest achieved the strongest average performance (RMSE , 95% CI ; MAE ; QWK ), with XGBoost being competitive (RMSE ; QWK ). Training a reduced Random Forest on the CV-selected subsets yielded no material degradation under the same repeated CV (RF: vs. RMSE; ), confirming that a compact subset retains most predictive power. SVR outperformed linear baselines, while Linear and ElasticNet underperformed, indicating non-linear interactions in the engineered features. Confidence intervals are narrow (e.g., ), suggesting stable generalization despite .

Table 3.

Classical baselines under repeated, stratified -fold CV. RF (reduced) uses CV-internal two-stage selection (variance/correlation prefiltering + RFECV); across 25 folds, the selected subset size had median 9 (IQR 6–14). We report mean RMSE with 95% CI across 25 validation folds, plus MAE and quadratic weighted kappa (QWK) computed on integer-rounded predictions. The best results are highlighted in bold.

5.1. Zero-Shot and Few-Shot LLM Results

We evaluate GPT-4o-mini under the same repeated, stratified CV protocol used elsewhere in the paper. In the zero-shot condition (), the model receives only the target excerpt and returns a single numeric age. In the few-shot condition, we include () exemplars ( per age) drawn only from the training fold, with a fixed token budget (, , ) and . Table 4 reports the main metrics, including RMSE, MAE, coefficient of determination (), and quadratic weighted kappa (QWK).

Table 4.

Comparison of zero-shot and few-shot (k = 5) performance under repeated, stratified CV (OOF). Values are mean ± 95% CI when available. The best results are highlighted in bold.

The results show a clear performance gap between the two settings. In the zero-shot case, the model failed to capture the complexity of age prediction, as reflected by high error rates (RMSE = 4.437, MAE = 3.518) and a negative value (−0.231). This indicates that the predictions were not reliable when no exemplars were provided.

In contrast, the few-shot () setting achieved strong improvements across all metrics. The RMSE decreased to 1.509, and the MAE dropped to 1.035. Furthermore, the value increased to 0.858, demonstrating that the model explained most of the variance in the target ages. The QWK score also reached 0.900, showing a high level of agreement with the gold standard labels.

Few-shot exemplars inject task-specific inductive bias from age-proximal texts, sharply reducing continuous-error metrics (RMSE/MAE) and yielding high ordinal agreement (QWK), whereas the zero-shot approach lacks such calibration.

5.2. Model-Blending Results

We combine Random Forest (RF) predictions with LLM outputs using the convex blend (Section 4.5). We evaluate two RF variants: RF (full) trained on all 19 features and RF (reduced) trained on the CV-selected subsets (median 9 features, IQR 6–14).

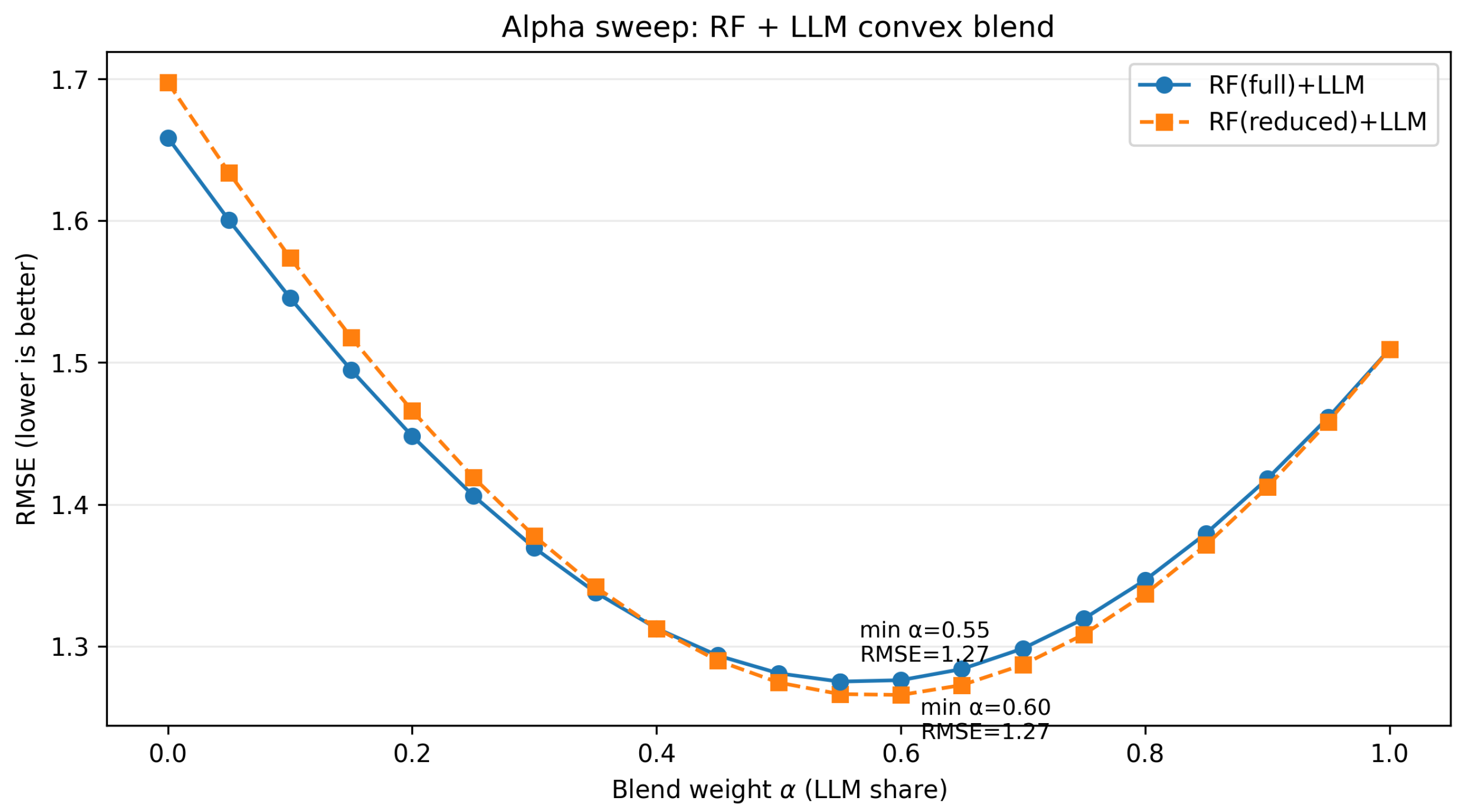

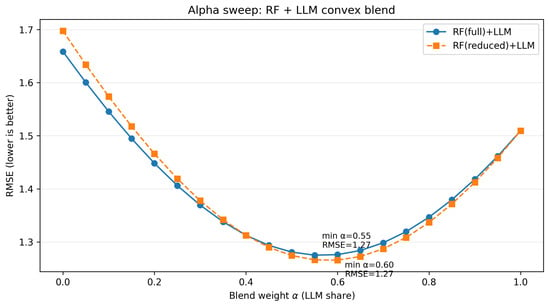

5.2.1. Alpha Sweep (Diagnostic)

Figure 3 plots RMSE as a function of the blend weight (LLM share). For both RF variants, RMSE decreases as increases from 0 and bottoms out around –, then rises again as the model becomes LLM-dominant. The minima of the two curves are nearly identical (annotated in the figure), indicating that the reduced feature set retains enough signal to blend as effectively as the full feature set does.

Figure 3.

Alpha sweep: RMSE vs. blend weight (LLM share) for RF (full) + LLM and RF (reduced) + LLM. Both achieve their minima near –.

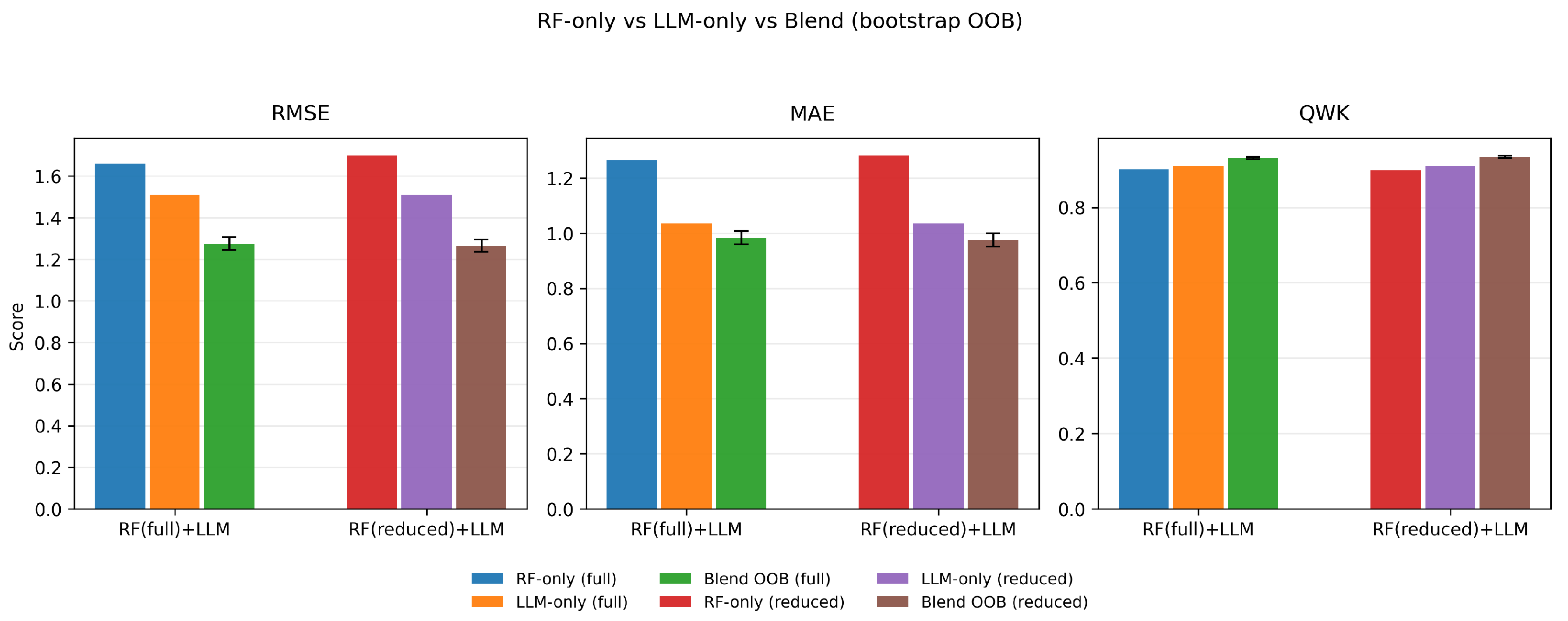

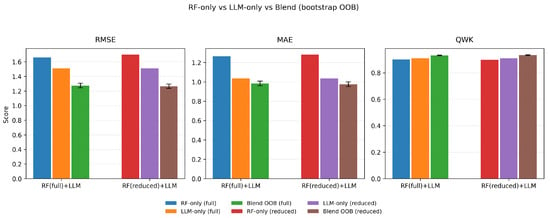

5.2.2. Selection-Free Performance (Bootstrap OOB)

To obtain an unbiased estimate of blend performance, we fit by minimizing in-bag MSE over bootstrap resamples and report metrics on out-of-bag (OOB) items (Section 4.5). Figure 4 compares RF-only, LLM-only, and Blend (OOB) across RMSE, MAE, and QWK for both RF variants. In all cases, the blended model improves RMSE/MAE over either component alone and slightly increases QWK, confirming that the RF and LLM carry complementary information.

Figure 4.

Selection-free performance (bootstrap OOB). RF-only, LLM-only, and Blend (OOB) compared on RMSE/MAE/QWK. Error bars denote CIs for the blended model. Blending improves RMSE/MAE in both RF variants and slightly increases QWK.

5.2.3. Blend Weight Stability

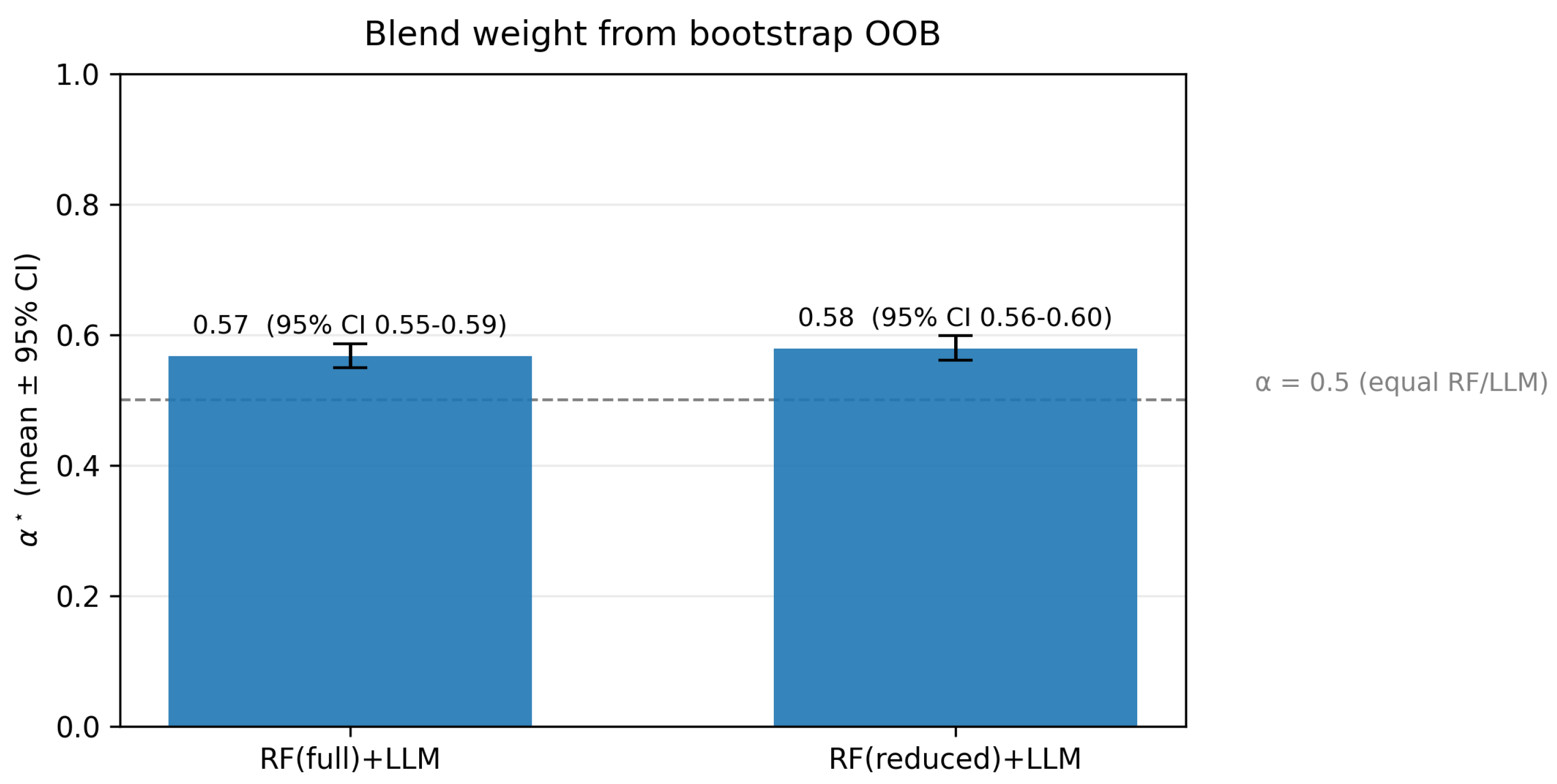

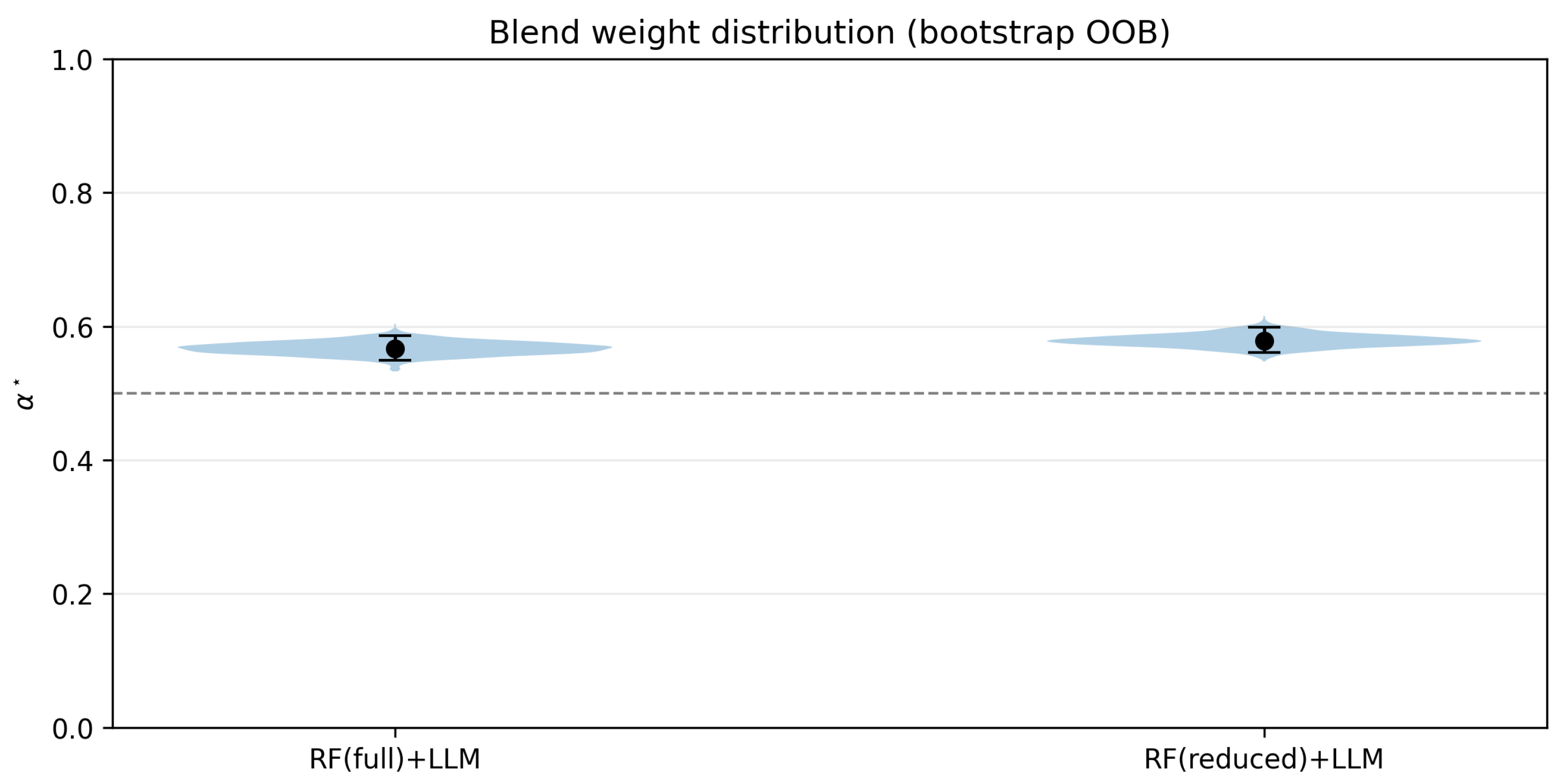

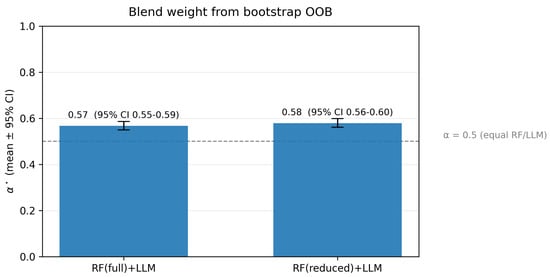

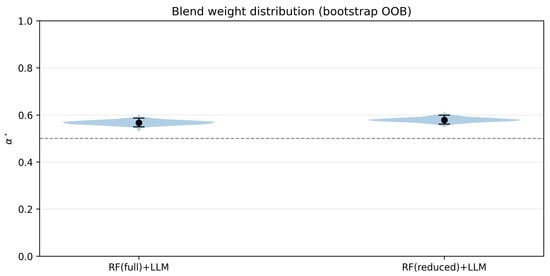

Figure 5 and Figure 6 summarize the estimated blend weights. The mean is (RF (full) + LLM) and (RF (reduced) + LLM), with narrow CIs (about and , respectively). The violin plot shows tight, unimodal distributions around –, both of which sit above the reference line, indicating that the LLM contributes slightly more, while the model still benefits from RF regularity. Critically, the RF(reduced) pair behaves almost identically to RF(full), supporting our claim that the dimensionality reduction preserves downstream blending behavior.

Figure 5.

Mean (bootstrap OOB) with CIs. The dashed line marks (equal RF/LLM). Both blends favor a slightly higher LLM share (–) with tight CIs.

Figure 6.

Distribution of (bootstrap OOB). Violin plots with mean ± 95% CI markers show stable, unimodal weights around – for both RF (full)+LLM and RF (reduced) + LLM.

Overall, the convex blend consistently outperforms individual models, and the reduced feature pipeline remains competitive with the full feature set under blending.

5.3. Feature-Level Hybrid Modeling Results

We evaluate two hybrid variants under the repeated, stratified CV protocol with fold-internal preprocessing and train-fold-only augmentation: Hybrid—Concat and Hybrid—Attention-gated (see Table 5). Both use frozen dbmdz/bert-base-turkish-uncased text embeddings, fold-specific PCA (), and RFECV on metadata with a minimum keep fraction of 30%.

Table 5.

Hybrid (augmented) results under repeated, stratified CV. We report mean metrics with 95% CIs from out-of-fold predictions; lower RMSE/MAE and higher /QWK are better. “Sel. (IQR)” is the per-fold number of metadata features retained by RFECV.

5.3.1. Aggregate Metrics

Across the 25 validation folds, the Hybrid—Concat model attains [95% CI 1.59–2.37], [1.24–2.03], [0.64–0.84], and [0.76–0.90] (Median #selected metadata features per fold: 14 (IQR 10–16).). These statistics are computed from out-of-fold predictions and reflect the repeated-CV uncertainty.

The Hybrid—Attention-gated variant yields [1.70–2.85], [1.33–2.48], [0.48–0.81], and [0.63–0.88], with a similar fold-wise selection profile (median 14, IQR 10–16).

5.3.2. Interpretation

Under data augmentation and repeated CV, simple feature concatenation remains the stronger fusion of the two: it achieves lower error and higher ordinal agreement than the attention-gated variant. The attention gate here is intentionally lightweight (a ridge-learned, fold-internal map from metadata to a sigmoid gate on the PCA-reduced text space); while it provides an interpretable, attention-like weighting without tuning the Transformer, its gains are not realized on our small-N setting.

5.3.3. Comparison to Classical Baselines

In our dataset, the best classical baseline (RF on the reduced feature set selected fold-internally) remains highly competitive, with tighter error bands and higher kappa values under the same repeated CV. This suggests that the engineered structural–lexical features already capture much of the age signal and that hybrid gains will likely require either stronger pooling/fusion or task-adaptive text encoders. We therefore position the hybrid models as complementary: they introduce semantic cues from text while preserving leakage-safe evaluation; future work will explore higher-capacity gates and end-to-end fine-tuning under regularization.

5.4. Rule-Based Readability Baseline (Ateşman) Results

We evaluate the Ateşman-based baseline under the same repeated, stratified CV protocol as our ML/LLM models, fitting the linear map from readability score to age within each training fold and evaluating on that fold’s validation items (leakage-free) (see Table 6. Aggregate out-of-fold results are as follows:

- RMSE [95% CI: , ]

- MAE [95% CI: , ]

- [95% CI: , ]

- QWK [95% CI: , ]

These figures indicate that a single readability scalar provides limited predictive power for age: error is relatively high, hovers around zero (often being negative across folds), and ordinal agreement (QWK) is near zero. In contrast, our blended (RF + LLM) and hybrid (BERT + meta) models, leveraging richer structural and semantic information, achieve substantially lower error and markedly higher agreement, demonstrating substantive improvements over the rule-based baseline.

Table 6.

Ateşman (rule-based) baseline under repeated, stratified CV. Mean metrics with 95% CIs from out-of-fold predictions; lower RMSE/MAE and higher /QWK are better.

Table 6.

Ateşman (rule-based) baseline under repeated, stratified CV. Mean metrics with 95% CIs from out-of-fold predictions; lower RMSE/MAE and higher /QWK are better.

| Method | RMSE (95% CI) | MAE (95% CI) | (95% CI) | QWK (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ateşman → Age (linear) | [1.96, 2.83] | [1.73, 2.30] | [, 0.107] | [, 0.169] |

5.5. Important Features for Suitable Age Value (SAV)

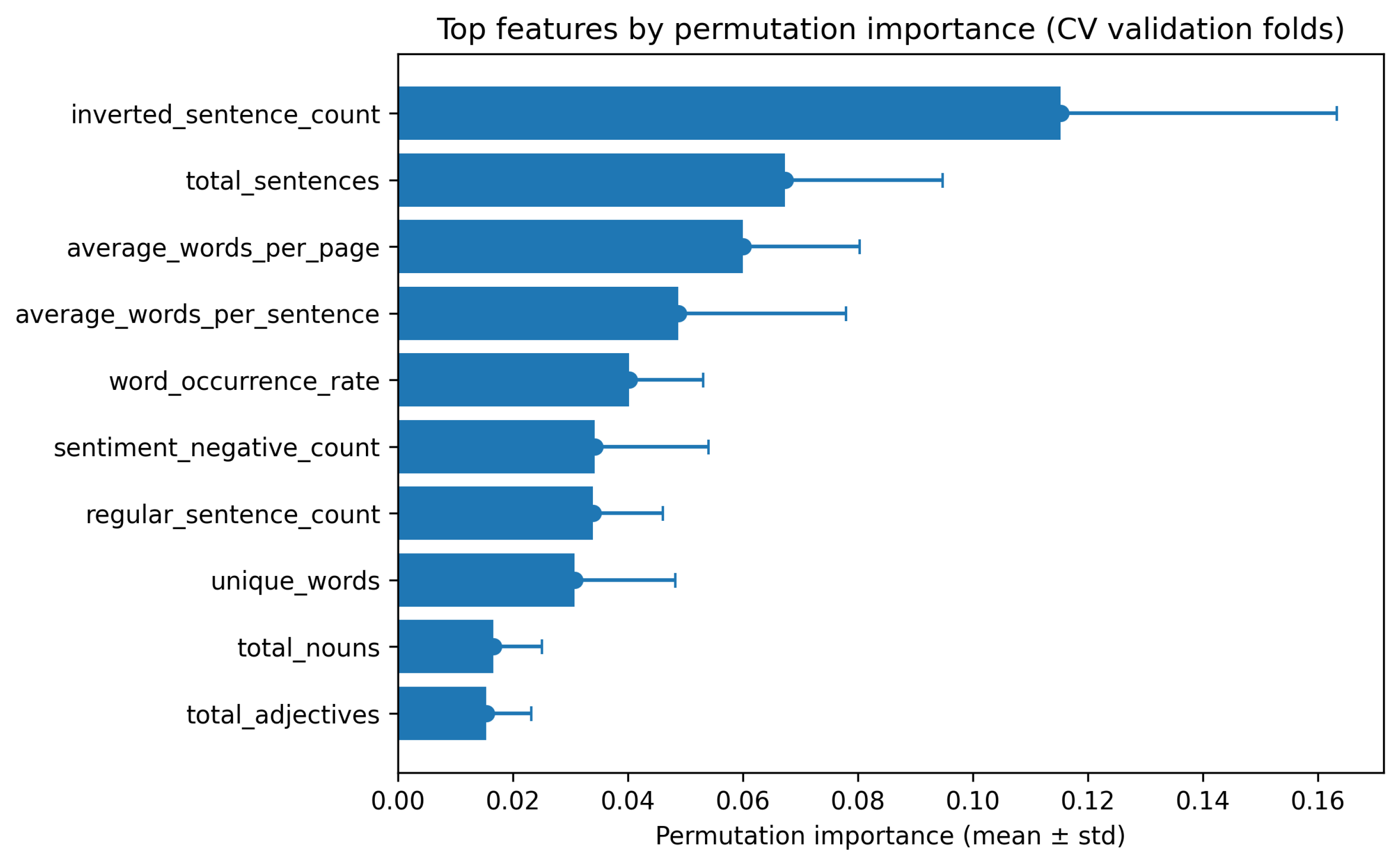

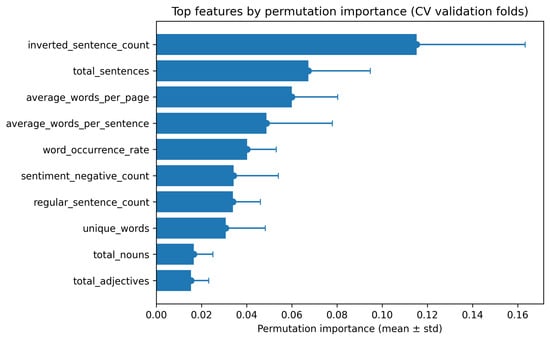

We audited feature relevance inside the cross-validation (CV) protocol to avoid leakage: in each training fold we applied a two-stage selection (VarianceThreshold + correlation prefilter, then RFECV with ExtraTrees), refit a Random Forest on the selected subset, and computed importance via both tree-based Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI) and model-agnostic permutation importance on the corresponding validation fold.

Across the repeated, stratified CV (25 folds), the number of selected features per fold had median 9 with IQR 6–14. Since the modeling matrix contained 19 numeric attributes, this corresponds to an average dimensionality reduction of with preservation of accuracy.

5.5.1. Selection Frequency

Five attributes were retained in all folds ( selection frequency): unique_words, average_words_per_sentence, inverted_sentence_count, sentiment_negative_count, and word_occurrence_rate. Additional high-frequency attributes included average_words_per_page (), and regular_sentence_count/total_sentences ( each).

5.5.2. Importance Rankings

MDI ranked inverted_sentence_count, word_occurrence_rate, and average_words_per_sentence among the top contributors on average across folds, followed by sentiment_negative_count and unique_words. Permutation importance on validation folds highlighted inverted_sentence_count most strongly, with total_sentences, average_words_per_page, average_words_per_sentence, and word_occurrence_rate forming the next tier.

Overall, structural/lexical attributes that quantify sentence structure and density (e.g., inverted_sentence_count, average_words_per_sentence, average_words_per_page, word_occurrence_rate) dominate SAV prediction. Notably, sentiment_negative_count was consistently selected () and showed non-negligible importance, yet its permutation gains were generally below those of the strongest structural features, indicating a secondary but stable signal from sentiment relative to structure (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Top features by permutation importance under repeated CV. Bars show mean permutation importance on validation folds with standard deviation as error bars. Structural/lexical cues such as inverted_sentence_count, total_sentences, and average_words_per_page dominate, with word_occurrence_rate and average_words_per_sentence also contributing consistently.

5.6. Visualization and Interpretation of Decision Tree from a Random Forest Model

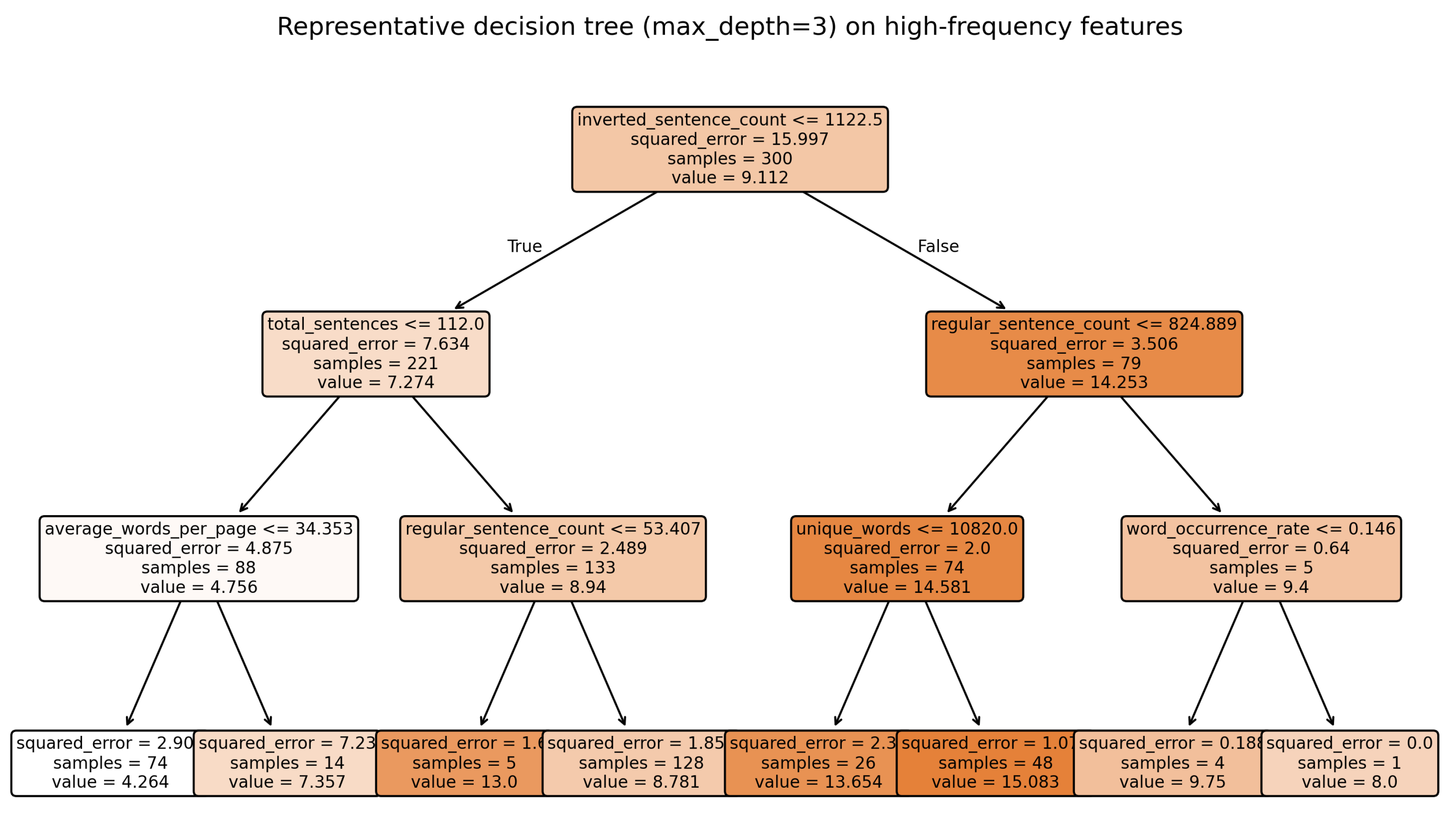

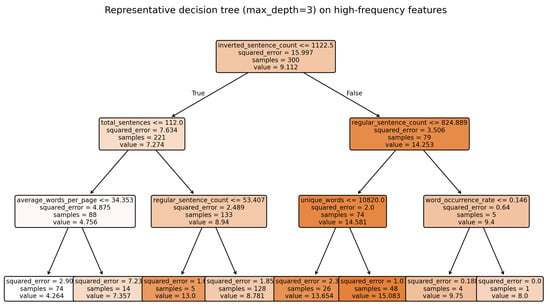

To provide interpretable insight complementary to aggregate importance, we visualize a representative decision tree (Figure 8) trained on the CV-selected feature subset (median nine features). Consistent with the importance audit, the top splits typically involve inverted_sentence_count and average_words_per_sentence, followed by page-level density metrics such as total_sentences or average_words_per_page and frequency measures like word_occurrence_rate.

Figure 8.

Representative decision tree (max_depth = 3) trained on high-frequency selected features. The top split uses inverted_sentence_count, followed by total_sentences, regular_sentence_count, average_words_per_page, unique_words, and word_occurrence_rate. While a single tree does not match the ensemble’s accuracy, it provides interpretable rules consistent with the CV importance analysis.

While a single tree cannot match the predictive performance of the full ensemble, it shows how structural/lexical cues (word order inversions, sentence length, and textual density) translate into age predictions. This qualitative view aligns with both MDI and permutation results, reinforcing that structural complexity and density are the primary determinants, with sentiment adding secondary refinements.

5.7. Error Analysis

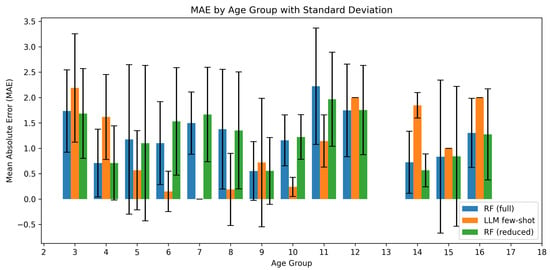

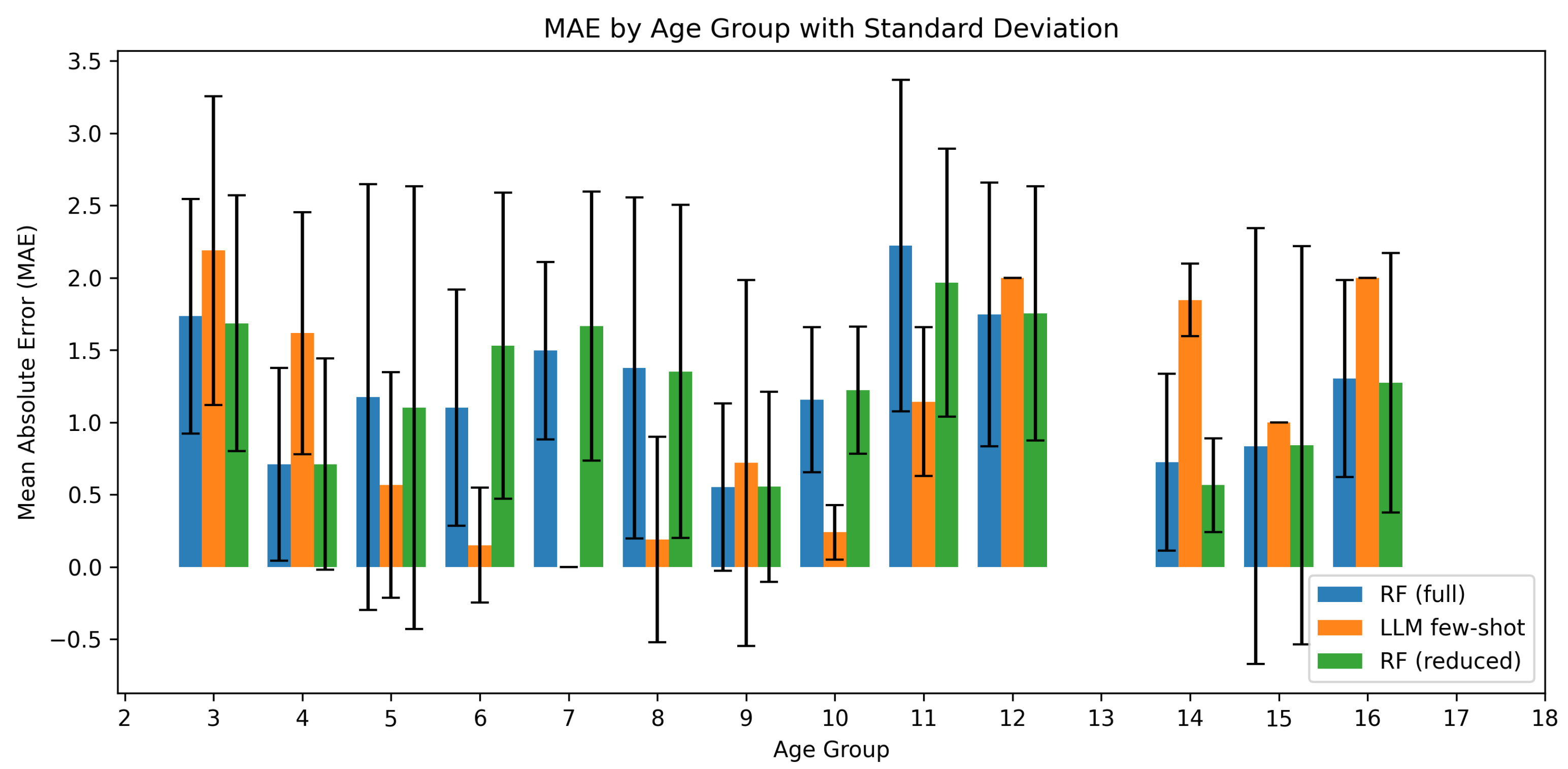

We analyze errors by age using out-of-fold (OOF) predictions under the repeated, stratified CV protocol (25 folds). Figure 9 presents grouped bars showing the mean absolute error (MAE) with standard-deviation error bars for three systems:

- Random Forest (RF, full) trained on all 19 engineered features,

- LLM few-shot (GPT-4o-mini, k = 5 exemplars drawn from the train fold only), and

- RF (reduced) trained on the CV-internal two-stage feature subset (variance/correlation prefiltering + RFECV; median nine features, IQR 6–14).

Figure 9.

Mean absolute error (MAE) and standard deviation of RF(full), RF(reduced) and LLM few shot predictions across age groups.

Figure 9.

Mean absolute error (MAE) and standard deviation of RF(full), RF(reduced) and LLM few shot predictions across age groups.

Mid-range advantage of LLM: Across the middle age bands (≈5–11), the LLM few-shot model generally achieves lower MAE than either RF variant. The gain is most visible around ages 6–8 years and 10–11 years, indicating that exemplar-guided prompting captures age-specific textual cues well in these “typical” school-age narratives.

Edge robustness of RF: At the younger (3–4 years) and older (≈12 years, 14–16 years) ends of the range, RF (full) tends to outperform the LLM, with RF (reduced) tracking RF(full) closely. This pattern is consistent with structural/lexical features (e.g., sentence/word distributions) providing stable signals where the LLM’s calibration from short excerpts is less reliable.

Variability: Error bars widen notably for the LLM at distribution edges (e.g., 3, 9, 11–12, 15), reflecting higher variance where sample sizes are small and content is heterogeneous. RF’s dispersion is more uniform across ages; the reduced model shows very similar dispersion to RF(full), confirming that dimensionality reduction does not materially alter the age-wise error profile.

5.8. Discussion and Interpretation

The CV-internal two-stage selection reduced the modeling matrix from 19 numeric attributes to a median of 9 per fold (IQR 6–14), i.e., an average dimensionality reduction of without degrading performance under the repeated CV protocol.

Both tree-based MDI and model-agnostic permutation importance converge on structural and lexical predictors—particularly inverted_sentence_count, average_words_per_sentence, average_words_per_page, total_sentences, and word_occurrence_rate. Sentiment carries a consistent but secondary signal: sentiment_negative_count is selected in all folds yet typically trails the strongest structural features in permutation impact. These findings indicate that syntactic regularity and text density remain the primary determinants of age suitability, while sentiment nuances can refine predictions for challenging cases.

Cross-Lingual Applicability and Expected Performance

Our pipeline combines language-agnostic structural/lexical features with language-specific components (e.g., Turkish readability and NLP models) and an LLM few-shot predictor. Because most of our predictive signal comes from structural regularities and text-density cues (e.g., sentence length, inversion counts, words-per-page), we expect moderate transferability to other languages after replacement of language-specific pieces with their in-language counterparts (readability metric, tokenizer/POS tagger, stop-lists) and retraining on a small labeled set. This expectation is consistent with our importance analysis in Turkish, where structural/lexical features dominate and sentiment plays a secondary role.

For the LLM branch, our results show that few-shot conditioning is critical, markedly outperforming zero-shot prompting; therefore, when moving to a new language, we would rely on in-language few-shot exemplars rather than zero-shot prompts.

Practically, implementing the model in another language entails the following steps: (i) swapping the Turkish-specific readability formula for a validated in-language readability proxy, (ii) using an in-language NLP stack for feature extraction, (iii) optionally replacing the frozen Turkish BERT with a strong in-language or multilingual encoder, and (iv) retraining the classical and hybrid models under the same leakage-safe repeated-CV protocol. We anticipate some performance drop without any relabeling (domain shift in style and age-labeling norms), but with a modest number of labeled books and few-shot exemplars, we expect performance to approach the Turkish results under our protocol.

5.9. LLM vs. Machine Learning Models (OOF Under Repeated CV)

We compare large language models (LLMs) to feature-based learners under the same repeated, stratified cross-validation protocol. All results are reported as out-of-fold (OOF) estimates to avoid optimistic bias on small-N datasets.

5.9.1. Setups

The classical baselines (Linear, ElasticNet, SVR, Random Forest, XGBoost) are summarized in Table 3. In addition, the RF (reduced) variant—trained on the CV-internal two-stage selection with a median of 9/19 features preserves accuracy relative to RF (full), supporting ≈53% dimensionality reduction. LLM results (zero-shot and few-shot) are reported in Table 4 using the same OOF protocol and deterministic prompting.

5.9.2. Headline Comparison

Taken together, the earlier tables show a clear pattern: (i) zero-shot GPT-4o-mini underperforms the classical baselines, indicating that unrestricted semantic inference without task conditioning is insufficient; (ii) with few-shot prompting ( exemplars from the training fold and a fixed token budget), GPT-4o-mini achieves strong OOF accuracy—matching or exceeding the RF variants on average without hand-engineered features (see Table 4 vs. Table 3); (iii) RF (reduced) remains highly competitive while using about half the features, corroborating our claim that a compact structural representation suffices for robust performance.

5.9.3. Error Profile by Age

Despite similar averages, the models behave differently across age bands. Figure 9 plots age-wise MAE (mean ± SD) for RF (full), RF (reduced), and the few-shot LLM under the same OOF splits. RF variants show slightly more stable errors at the extremes (younger/older groups), whereas the LLM is competitive or better around mid-range ages, consistent with its ability to leverage contextual cues when given compact, label-anchored guidance.

5.9.4. Takeaway and Motivation for Blending

The complementary strengths, RF’s stability and LLM’s semantic sensitivity, motivate the use of a convex blend (RF + LLM) evaluated in Section 5.2. As shown there, the bootstrap OOB tuning of the blend weight can yield small but consistent gains while preserving robustness.

5.9.5. Limitations and Complex Dependencies

Complex dependencies among structural and semantic signals pose challenges for purely feature-based or purely LLM pipelines. Our analysis indicates that tree ensembles stably exploit non-linear structure in engineered features, while the few-shot LLM injects discourse/topic cues that are hard to hand-engineer; neither alone captures the full dependency pattern, motivating blending. Under small-N, hybrids with frozen encoders underperform RF and zero-shot LLM is unreliable; hence, few-shot prompting and model blending are recommended. Interpretability remains stronger on the feature-based side. as shown by permutation/MDI inspections, which consistently identify structural density and sentence-order cues as primary drivers of SAV.

6. Conclusions

This work presents a leakage-safe, end-to-end framework for estimating the Suitable Age Value (SAV) of Turkish children’s books by combining structured linguistic/structural features with text-based signals. Under repeated, stratified CV and OOF evaluation, a Random Forest trained on engineered features remains a strong baseline with tight error bands. A few-shot LLM (GPT-4o-mini) substantially improves performance over the zero-shot approach and reaches high ordinal agreement (QWK), showing that task-proximal exemplars inject useful inductive bias. Among feature-level fusions with frozen BERT, a simple concatenation outperforms a lightweight attention-gated variant, yet both trail the top classical baseline in our small-N setting. Crucially, a convex blend of RF and LLM, with the blend weight fitted via bootstrap out-of-bag sampling, consistently reduces RMSE/MAE versus either component and slightly increases QWK, indicating complementary structural and semantic evidence. Finally, a readability-only (Ateşman) baseline proves insufficient on its own.

These results collectively suggest a practical recipe for age grading at scale: engineer stable structural features; apply leakage-safe repeated CV; add few-shot prompting for semantic cues; and blend the two sources for robust gains. Limitations include the modest dataset size and frozen text encoder; future work will explore larger/augmented corpora, task-adaptive encoders, and richer fusion (e.g., attention with capacity control), as well as ordinal objectives and calibration tailored to age scales. In domains where transparency matters, tree-based models and attention analysis from the transformer literature provide interpretable handles for stakeholders.

Finally, because our strongest signals are language-agnostic structural cues and our LLM component benefits from in-language few-shot conditioning, we expect the framework to transfer to other languages after swapping language-specific modules and retraining on a modest labeled set.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N.K. and B.G.; Methodology, F.N.K.; Software, F.N.K.; Validation, F.N.K., B.G., F.S. and A.A.; Formal analysis, F.N.K. and B.G.; Investigation, F.N.K.; Resources, F.N.K.; Data curation, F.N.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, F.N.K.; Writing—review and editing, F.N.K., B.G., F.S. and A.A.; Visualization, F.N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RFECV | Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation |

| MDI | Mean Decrease in Impurity |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| QWK | Quadratic Weighted Kappa |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ET | ExtraTrees (Extremely Randomized Trees) |

| OOF | Out-of-Fold |

| OOB | Out-of-Bag (bootstrap validation) |

| SAV | Suitable Age Value |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CLS | [CLS] token (classification embedding in BERT) |

| SARI | System output Against References and Input |

| FK | Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level |

References

- Britt, S.; Wilkins, J.; Davis, J.; Bowlin, A. The benefits of interactive read-alouds to address social-emotional learning in classrooms for young children. J. Character Educ. 2016, 12, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, D.K.; Griffith, J.A.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K. How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Dev. Res. 2012, 2012, 602807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başbakanlık, T.C. Çocuk haklarına dair sözleşme. Resmi Gazete 1995, 44, 22184. [Google Scholar]

- Gürel, Z. Âkif’in eserlerinde çocuk, çocukluk ve eserlerinin çocuk edebiyatı açısından değerlendirilmesi. AKRA Kültür Sanat ve Edeb. Derg. 2016, 4, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kara, C. Çocuk kitabı seçiminde resimlemelerle ilgili olarak ebeveynin dikkat etmesi gereken başlıca unsurlar. Batman Üniv. Yaşam Bilim. Derg. 2012, 1, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Çiftçi, F. Çocuk edebiyatinda yaş gruplarına göre kitaplar ve özellikleri. Anemon Muş Alparslan Üniv. Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2013, 1, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI, GPT-4o mini: Advancing Cost-Efficient Intelligence. Available online: https://openai.com/index/gpt-4o-mini-advancing-cost-efficient-intelligence/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Turkish Statistical Institute. TUIK Library Statistics. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Kutuphane-Istatistikleri-2023-53655 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Scarborough, H.S.; Dobrich, W. On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Dev. Rev. 1994, 14, 245–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, G.A.; Nyhout, A.; Ganea, P.A. The role of book features in young children’s transfer of information from picture books to real-world contexts. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleryüz, H. Yaratıcı Çocuk Edebiyatı; Pegem A. Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar, A. Value of children’s literature and students’ opinions regarding their favourite books. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2021, 17, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircan, C. TÜBİTAK çocuk kitaplığı dizisindeki kitapların dış yapısal ve iç yapısal olarak incelenmesi. Mersin Univ. Egit. Fak. Derg. 2006, 2, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, M.; Pilav, S. Tübitak çocuk kitaplarının çocuk edebiyatı yönünden incelenmesi. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli Üniversitesi SBE Dergisi 2021, 11, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitapyurdu Online Bookstore. Çocuk Kitapları. Available online: https://www.kitapyurdu.com/index.php?route=product/category&path=2 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- D&R Online Bookstore. Çocuk Kitapları. Available online: https://www.dr.com.tr/kategori/Kitap/Cocuk-ve-Genclik/grupno=00884 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- BKM Online Bookstore. Çocuk Kitapları. Available online: https://www.bkmkitap.com/kitap/cocuk-kitaplari (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Toronto Public Library. Children’s Books. Available online: https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/books-video-music/books/childrens-books/ (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Amazon Website. Sketty and Meatball. Available online: https://www.amazon.ca/Sketty-Meatball-Sarah-Weeks/dp/0062431617 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Imperial, J.M.; Roxas, R.E.; Campos, E.M.; Oandasan, J.; Caraballo, R.; Sabdani, F.W.; Almaroi, A.R. Developing a machine learning-based grade level classifier for Filipino children’s literature. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Asian Language Processing (IALP), Shanghai, China, 15–17 November 2019; pp. 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzipanagiotidis, S.; Giagkou, M.; Meurers, D. Broad linguistic complexity analysis for Greek readability classification. In Proceedings of the 16th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications, Online, 20 April 2021; pp. 48–58. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2021.bea-1.0/ (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Hall, M.; Frank, E.; Holmes, G.; Pfahringer, B.; Reutemann, P.; Witten, I.H. The WEKA data mining software: An update. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2009, 11, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvean, M.; Enkhbayar, G. Assessing the readability of fiction: A corpus analysis and readability ranking of 200 English fiction texts. Linguist. Res. 2018, 35, 137–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niksarli, A.; Gorgu, S.O.; Gencer, E. Identification of books that are suitable for middle school students using artificial neural networks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.07591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]