Abstract

The extraction of relationships in natural language processing (NLP) is a task that consists of identifying interactions between entities within a text. This approach facilitates comprehension of context and meaning. In the medical field, this is of particular significance due to the substantial volume of information contained in scientific articles. This paper explores various training strategies for medical relationship extraction using large pre-trained language models. The findings indicate significant variations in performance between models trained with general domain data and those specialized in the medical domain. Furthermore, a methodology is proposed that utilizes language models for relation extraction with hyperparameter optimization techniques. This approach uses a triplet-based system. It provides a framework for the organization of relationships between entities and facilitates the development of medical knowledge graphs in the Spanish language. The training process was conducted using a dataset constructed and validated by medical experts. The dataset under consideration focused on relationships between entities, including anatomy, medications, and diseases. The final model demonstrated an 85.9% accuracy rate in the relationship classification task, thereby substantiating the efficacy of the proposed approach.

1. Introduction

Relationship extraction in the context of NLP refers to the task of identifying semantic interactions between entities within a text. Relationships are semantic links that enable an understanding of context. In the domain of medicine, this task is crucial due to the volume and complexity of information contained in scientific articles, clinical records, and specialized databases. Increasing access to medical data, both structured and unstructured, presents new opportunities for implementing automatic techniques in decision-making and medical knowledge management.

Knowledge graphs are a way of representing the extracted information. Nodes represent medical entities such as diseases, drugs, procedures, or anatomy. Edges describe the relationships between entities, for example, a drug that treats a disease. This representation facilitates the visualization, integration, retrieval, and inference of information. It enables the development of intelligent applications such as question-and-answer systems or clinical assistants.

Processing scientific article abstracts offers an effective alternative for knowledge extraction. Abstracts summarize the objectives, methodology, results, and conclusions of the study. Processing abstracts generates lower computational costs compared to processing the full text. Abstracts facilitate the identification of key terms and the establishment of meaningful relationships between entities, which supports tasks such as named entity recognition (NER) [1] and relationship classification [2]. Due to the volume of scientific documents produced daily, manual extraction of relationships is an impractical solution. This underscores the need for automated solutions based on NLP.

The process of extracting medical relationships between entities such as anatomy, medication, and disease is a fundamental task in biomedical text analysis. In this context, this paper describes an approach to extracting medical relationships by applying named entity recognition within scientific abstracts in Spanish. This approach utilizes deep learning techniques, with a focus on Large Language Models (LLMs). These models demonstrate high performance in classification and information extraction tasks in specialized domains.

One of the main challenges in medical relation extraction is the limited availability of expert-validated datasets. Additionally, traditional methods must be effectively integrated with more advanced models. This paper proposes the creation of a specialized dataset validated by experts, as well as the training of an LLM with hyperparameter fine-tuning optimization for the task of medical relation extraction in Spanish.

Furthermore, a hybrid approach is proposed that integrates NER with classical algorithms such as Random Forest and specialized LLMs such as MedicoBERT [3] for relation classification. The model obtained for the recognition of relations between medical entities is based on the generation of triplets to construct knowledge graphs useful in clinical and research applications. A hyperparameter tuning process is performed to adapt the LLM to the medical domain in Spanish, with a significant improvement in performance.

In this paper, MedicoBERT is used as a base model for the task of medical relation classification. On this basis, fine-tuning with hyperparameter optimization is performed on a dataset annotated by experts to expand the model’s capacity in identifying semantic relations between medical entities. The linguistic knowledge acquired during the MedicoBERT pre-training is leveraged.

The extracted relationships enable the representation of connections between different medical entities within a knowledge graph. This organized representation facilitates the development of applications with more efficient search processes and reduced computational response times. It can also feed automatic summarization tools, recommendation systems, and medical decision support environments. Scientific information structured in the form of a knowledge graph establishes explicit links between diseases, drugs, and parts of the body. The authors of [4] describe how knowledge graph-based search engines understand the entities present in queries and provide direct entity-centric answers. This approach demonstrates the potential to improve access to information in the medical field.

2. Related Work

Relation extraction is a task within the domain of NLP applied to distinct domains. For example, in [5], a relationship extraction model is proposed in the general domain, merging multiple types of information and applying a tension mechanism to improve detection by assigning weights to different parts of the text, focusing on those most relevant to identifying the relationship. The application of a final classification layer to label the relationships is a key feature of the system. A relationship extraction model is proposed in [6] for the specific domain of Chinese banking sector texts. The model employs BERT to construct a knowledge graph, which facilitates the querying and location of regulatory requirements. The proposed model for the financial domain consists of BERT, entity location, BiLSTM (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory) [7], and a relationship type classifier.

In contrast, the extraction of medical relations from the scientific literature constitutes a critical task within the domain of NLP applied to medical texts. This discipline facilitates the conversion of unstructured content into structured knowledge bases, a process that is imperative for the development of support systems within the medical domain. A major development in this area is the integration of pre-trained LLMs customized for the medical domain. Among these, BioBERT [8] is a noteworthy exception, representing a specialized variant of the BERT model that has been trained on an extensive biomedical corpus in English, including resources such as PubMed and PMC. BioBERT has demonstrated substantial improvements in tasks such as entity recognition and medical relation extraction. In the context of the Spanish language, models such as MedicoBERT [3] have been developed and trained on Spanish-language medical texts, including scientific articles. These models have been meticulously designed to address the unique requirements of the medical sector in the Spanish language.

Beyond transformer-based models, more complex approaches have emerged, integrating attention mechanisms and hierarchical linguistic structures. For instance, the SARE model [9] employs hierarchical attention mechanisms to identify relations among biomedical entities, including proteins, drugs, and chemical compounds. This model has achieved notable results on standardized datasets such as DDI (Drug–Drug Interactions), PPI (Protein–Protein Interactions), and ChemProt.

The evaluation of the biomedical corpus is an active field, and there are several widely recognized resources available for this research. One of the most comprehensive resources is BioRED [10], which is composed of PubMed abstracts annotated with multiple entities and relations. This resource also differentiates between established knowledge and novel relationships. Other prominent datasets include DDI [11], PPI [12], and ChemProt [13], each focused on specific types of biomedical interactions, all in English. In the Spanish language, a significant resource is the NLPMedTerm project [14], the initial deliverable of which is a medical lexicon developed by experts from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. This lexicon is designed for processing medical language in Spanish. Additionally, hybrid approaches and multimodal methods have been explored; for instance the MeTAE system [15] combines semantic rules with tools such as MetaMap for the extraction of therapeutic relationships between drugs and diseases.

Alternatively, BioGraphSAGE [16] integrates graph neural networks with structured knowledge from biological databases, enabling the representation of complex relationships among entities extracted from the biomedical literature.

Concurrently, other relevant studies have focused on specific clinical contexts; for instance, [17] presents a deep learning-based system for extracting relationships among diseases, tests, and treatments from medical prescriptions, using a convolutional neural network with embedding, feature extraction, and classification modules. Furthermore, the hierarchical convolutional model proposed in [18] incorporates semantic sentence segmentation and multi-channel convolutions over BERT-generated representations, effectively capturing semantic dependencies.

In the context of Spanish and employing more conventional approaches, the study presented in [19] implements a semantic relation classifier based on Support Vector Machines (SVMs). This system employs lexical, named entity, and syntactic features and evaluates various combinations after translating a corpus originally developed in English into Spanish, thereby adapting the model to multilingual environments.

Table 1 presents the reviewed works that demonstrate significant progress in the task of medical relation extraction with pre-trained language models, hybrid approaches, and specialized resources, particularly in English. However, a significant gap exists in the development of models and resources adapted to Spanish, which limits their applicability in medical contexts of this language. This deficiency underscores the necessity for research endeavors focused on medical knowledge extraction in Spanish. Such research should entail the creation of specialized corpora, the adaptation of existing models, and the exploration of hybrid strategies that integrate linguistic and medical knowledge. This paper makes a significant contribution to this goal by proposing a methodology that aims to reduce this gap and advance the construction of tools for the automatic analysis of medical texts in Spanish.

Table 1.

Comparison of related work on the task of relation extraction.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the approach, which integrates classical techniques for NER and deep learning methods for automatic relation extraction. The primary objective of this approach is to construct and improve a medical knowledge graph. This knowledge representation integrates relevant information extracted from the abstracts of scientific articles.

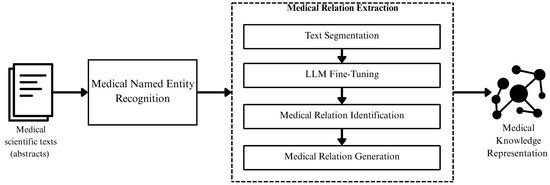

Figure 1 presents a general methodology of the phases, as well as the interaction between each of them, which are detailed below.

Figure 1.

Methodology of the proposed model.

3.1. Medical Scientific Texts

The initial knowledge is obtained from a set of scientific articles belonging to a specialized collection, as referenced in [20]. This dataset is part of the MESINESP (Medical Semantic Indexing in Spanish) [21] task, whose objective is to promote the development of semantic indexing tools for biomedical content in languages other than English. All documents were annotated with DeCS (Descriptors in Health Sciences) [22] descriptors, a structured and controlled vocabulary developed by BIREME (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information) [22] to index scientific publications in BVSalud (Virtual Health Library) [23].

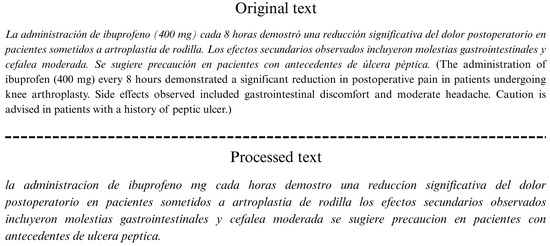

Plain text documents undergo a preprocessing procedure. The cleaning process is informed by exploratory analysis. The objective is to identify and preserve information that may be of medical significance. The cleaning process entails the removal of punctuation marks, including periods, commas, semicolons, underscores, slashes, brackets, parentheses, colons, and both Spanish and English quotation marks. Furthermore, regular expressions are employed to suppress numbers and digits combined with special characters, such as dots, slashes, hyphens, plus signs, and hashtags. Additionally, the utilization of symbols in conjunction with signs, such as plus/minus, equal, greater than, less than, percentage, and the ampersand, is crucial for effective communication. This analysis enables the flexible management of terms, allowing for their complete preservation or omission, while ensuring the accurate identification of named medical entities. For instance, the term “COVID-19” is not altered thanks to the regular expressions used and the analysis of the signs that can be removed.

Figure 2 shows an example of a text in its original form and the result of applying the preprocessing techniques described.

Figure 2.

Text preprocessing example.

3.2. Medical Named Entity Recognition

Subsequently, medical entities are recognized using the methodology implemented in [24]. This implementation uses a vector of semantic, syntactic, and contextual features at the token level. The following section will delineate the features:

- Multi-word expression belonging to a medical semantic group: A value indicating the medical semantic group the current token belongs to. A value of 1 is assigned if the token is the start of a term within a medical semantic group, and 2 if it is part of a multi-word term but not the beginning. Otherwise, it is assigned a 0.

- Medical semantic group type: A value indicating the semantic group type for the current token, or 0 if none.

- Dependency type: The type of dependency relation of the current token.

- Syntactic parent node dependency type: The dependency type between the current token and its syntactic parent.

- POS tag: The general grammatical part-of-speech tag.

- POS tag of the syntactic parent node: Syntactic parent node.

- Left child nodes: Indicates whether the current token has left child nodes (within a two-token window). A value of 1 if present, 0 otherwise.

- Right child nodes: Indicates the presence of right child nodes (within a two-token window). A value of 1 if present, 0 otherwise.

Medical features 1 and 2 are defined based on Deliverable 1 of the NLPMedTerm project (Natural Language Processing for Medical Terminology) [14]. This deliverable comprises a Spanish medical lexicon developed by experts from the Autonomous University of Madrid, which is organized into 127 semantic groups. These features utilize 11 categories that correspond to anatomy, diseases, and drugs.

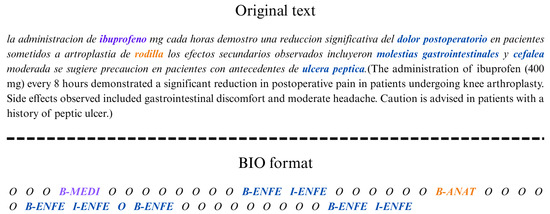

The remaining features are obtained using internal hash tables, complementing automatic identification with additional lexical and contextual information. Entity recognition is performed at the token level, identifying entities in Spanish classified into anatomy (ANAT), diseases (ENFE), and medications (MEDI). The BIO (Begin–Inside–Outside) labeling scheme [25] is used to distinguish the beginning (term B), continuation (term I), or absence (O) of an entity in a text sequence.

NER uses the classic Random Forest machine learning (ML) technique as a classification model with 97% accuracy. Figure 3 shows an example of the output.

Figure 3.

Example of a medical entity recognizer with BIO format.

3.3. Medical Relation Extraction

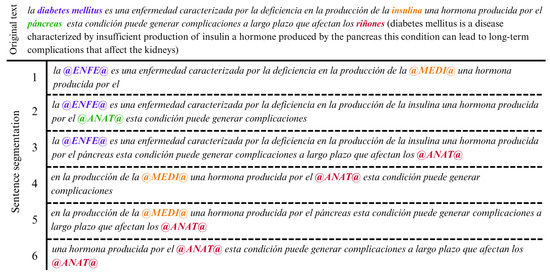

In the medical relationship extraction phase, the previously processed texts are segmented. Segmentation involves identifying and extracting all possible sentences that contain at least two recognized medical entities. The restriction is that the distance between them must not exceed 20 words.

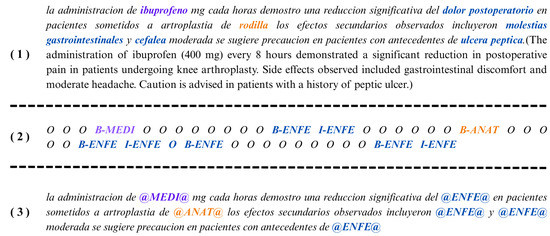

The identified entities are masked within each sentence using specific tags according to their type. The acronyms @ENFE@, @ANAT@, and @MEDI@ are used for diseases, anatomy, and drugs, respectively. Masking standardizes the representation of entities to facilitate the detection of medical relationships. Each extracted sentence contains all the words between the two entities, along with a context window of five words on both sides.

All combinations of entities are evaluated to derive several candidate sentences from the same text fragment. The entities involved in a relationship are hidden in each sentence, preserving the rest of the content.

The sequences of terms B and I are grouped into a single hidden term. For example, for a disease, all relevant labels (B-ENFE and I-ENFE) were systematically replaced by @ENFE@. The original term is retained for further analysis and representation. Figure 4 shows this process.

Figure 4.

Example of masked text: (1) Original text with highlighted entities. (2) The BIO-annotated version. (3) The final masked version.

In Figure 5, the sentence segmentation process from the original text is presented, in conjunction with entity masking.

Figure 5.

Example of sentence segmentation from text.

The purpose of entity masking is to enable the model to identify specific medical relationships between two entities. It also prevents the introduction of other medical terms that may interfere with the context. This highlights the importance of local context and facilitates the accurate management of compound medical terms. In the example in Figure 5, only the entities involved in each sentence are masked, and the rest of the text remains unchanged.

Masking is based on Harris’s distributional hypothesis [26], which posits that words that appear in similar contexts tend to have similar meanings. Therefore, the coincidence of two nearby medical entities suggests the likelihood of a shared semantic context, indicating a possible relationship between them. This principle is reinforced by LLMs that utilize attention mechanisms to assign greater weight to nearby tokens, thereby facilitating the identification of meaningful relationships.

Segmentation was performed on 990 articles from the BioASQ corpus, extracting 1912 sentences with a minimum of two medical entities (ANAT, ENFE, or MEDI). Three medical experts manually annotated the semantic relationships between entities. The annotation system is binary, assigning a value of 1 to indicate a valid relationship and 0 in the case of an invalid relationship.

The resulting dataset, accessible in [27], is used to train an LLM for the binary classification of medical relations. In total, 80% of the phrases are allocated for training and the remaining 20% for evaluation. A maximum precision of 90.6% is obtained using MedicoBERT [3] as the base model.

According to the authors of MedicoBERT, the model was pre-trained on two different tasks: masked language modeling (MLM) and next sentence prediction (NSP). These tasks were performed using a dataset consisting of more than three million medical texts in Spanish. The corpus is made up of three different biomedical datasets recognized by the research community. The BioASQ, CoWeSe, and CORD-19 datasets comprise approximately 1.1 billion words in total.

The MedicoBERT tokenizer, developed to process medical texts with a vocabulary of over 50,000 specialized tokens, is also used. This tokenizer enables accurate and contextual representation of medical terms to improve performance on specific tasks.

Initially, a preliminary adjustment of the hyperparameters is performed using an exploratory approach to identify a candidate range for each parameter. This phase involved a literature-guided search adapted to the context of medical relationship identification.

The subsequent adjustment stage employed Bayesian optimization, which constructs a probabilistic surrogate model (typically a Gaussian process or GP). The model’s performance is estimated across a range of hyperparameter configurations. The search is guided by an acquisition function designed to balance exploration and identify a global optimum. A random function represents the model’s performance, as shown in Equation (1).

where is the expected model performance and is a kernel representing similarity between configurations.

The expected improvement (EI) acquisition function is used to select the next set of hyperparameters to be evaluated. Equation (2) represents the expected value of the improvement in the objective function with respect to the best known value . This improvement is only considered when it is positive; otherwise, a value of 0 is assigned. Thus, points that do not exceed the current value do not penalize the result but do not contribute to the expected value. This behavior allows a balance to be achieved between exploitation and exploration during the optimization process. Points with a high expected mean corresponding to the exploitation of acquired knowledge are favoured. Conversely, points with high uncertainty in the prediction are valued, which encourages the exploration of potentially promising regions of the search space.

The trained model is designed to identify the presence of medical relationships in sentences with two masked entities. The entities involved can be diseases, anatomy, or medications. The model output has a binary structure, where 1 indicates the presence of a relationship and 0 means its absence.

Relationships annotated as valid are assigned rules defined as semantically consistent. Table 2 presents the six types of rules that demonstrate the semantic validity of the relationships transferred to the knowledge graph.

Table 2.

Types of medical relations.

In addition, a hierarchical relationship is defined for cases in which both entities are of the same type, using the generic relationship “es_un” (is_a), as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Generic relationship.

Relationships enable the construction of informative triplets in the form of a relationship (entity A, entity B). The new processed texts have a verification mechanism to avoid duplication of generated triplets. The identification of specific relationships is verified along with the updating of the hierarchical relationship to ensure semantic enrichment.

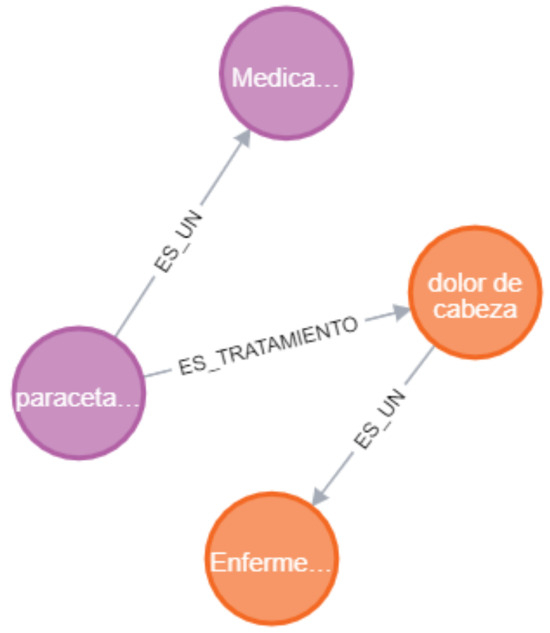

For example, if a relationship is found between dolor de cabeza (headache) and paracetamol (paracetamol) (ENFE and MEDI), the triplets generated are as follows:

- es_tratamiento (paracetamol, dolor de cabeza)is_treatment_for (paracetamol, headache);

- es_un (paracetamol, medicamento)is_a (paracetamol, drug);

- es_un (dolor de cabeza, enfermedad)is_a (headache, disease).

The triplets reflect the specific semantic relationships es_tratamiento (is_treatment_for) and es_un (is_a). This integration of contextual links with structured representations in the knowledge graph facilitates the interpretation of medical information.

Figure 6 illustrates a section of the knowledge graph, highlighting the relationships from the example mentioned above.

Figure 6.

Subgraph of knowledge generated from a representative example.

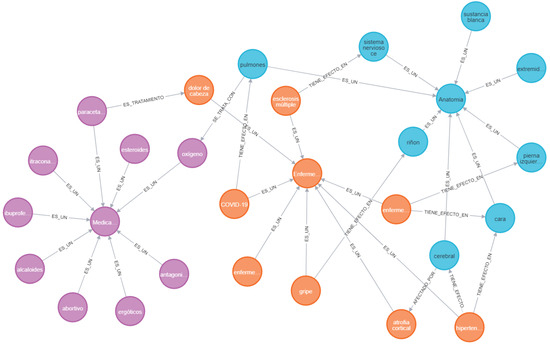

In a knowledge graph, triplets are represented by a network of nodes and edges. In this context, the nodes correspond to medical entities and the edges represent relationships. The final knowledge graph contains 4355 nodes, 2217 diseases, 969 drugs, and 1169 anatomy, as well as 12,294 extracted relationships. Figure 7 shows a knowledge subgraph with nodes of each entity type (disease, anatomy, and medicine) to facilitate visual analysis and interpretation.

Figure 7.

Knowledge subgraph with nodes of each entity type (disease, anatomy, and drug).

4. Results

Medical relations were extracted using 1912 sentences generated from text segmentation. The class distribution is shown in Table 4. The dataset underwent manual validation by medical experts to ensure its quality and reliability.

Table 4.

Type of entities involved in the segmented and expert-labeled sentences.

Segmented sentences consist of two types of entities. In each instance, experts were tasked with determining whether a relationship existed between the entities involved. Table 4 presents the distribution of entities within the set of segmented sentences. The results also indicate the number of sentences in which the experts identified the existence or non-existence of a relationship. For instance, if a segmented sentence encompasses an ENFE entity and an ANAT entity, yet no medical or contextual relationship is observed between them, the experts annotated it as a “Relationship without existence” (0). Conversely, if a relationship is identified, it is recorded as a “Relationship without existence” (1).

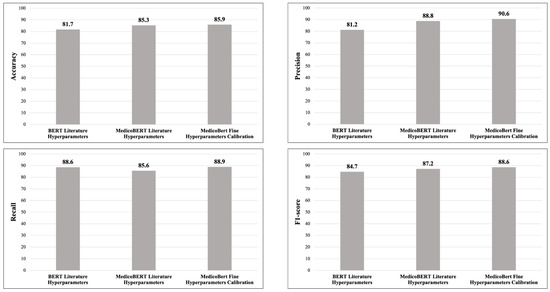

Two pre-trained LLMs are evaluated on the binary classification task with hyperparameters obtained from the literature. The hyperparameters of the training process included 15 epochs, an initial batch size of 8, a learning rate of 5 × 10−5, an adamw_torch optimizer, and a weight decay of 0.01.

The BERT LLM [28] was trained on a corpus of English Wikipedia texts [29] and BooksCorpus [30] for general language comprehension. The LLM demonstrated a maximum precision of 80.8% for predicting a medical relationship.

The second LLM tested is MedicoBERT [3], pre-trained for the medical domain using a corpus of over three million medical texts in Spanish. The texts come from three well-known datasets in the domain: BioASQ [20], CoWeSe [31], and CORD-19 [32], with approximately 1.1 billion words. This model demonstrated a maximum accuracy of 88.2%, attributable to its training with Spanish medical texts.

Based on these results, a third experiment was conducted to fine-tune the hyperparameter calibration in MedicoBERT. A Bayesian optimization strategy with Gaussian processes was used, see Equations (1) and (2). The ranges of the hyperparameters during the experimental phase are described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ranges of hyperpameters used during the experiments.

The model was trained with the best configuration found: 15 epochs, a batch size of 16, a learning rate of 2.39291 × 10−5, an adamw_hf optimizer, and a weight decay of 0.01. These values achieved a maximum accuracy of 90.6%. To optimize accuracy in the task of classifying medical relationships in Spanish, it is necessary to adjust the hyperparameters together. Modifying them in isolation does not lead to optimal performance.

The results of the experiments with BERT, MedicoBERT, and MedicoBERT with hyperparameter fine-tuning calibration using precision, accuracy, recall, and F1 score as metrics are detailed in Figure 8. Table 6 shows the results of the MedicoBERT experiments with hyperparameter fine-tuning for epochs. These results show the epoch values for four metrics used in classification: precision, recall, accuracy, and F1 score. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of model performance. Precision indicates the proportion of predicted positive relationships that are actually correct. Recall evaluates the model’s ability to identify all relevant relationships. Precision provides an overview of performance. The F1 score is a combination of precision and recall that provides a balanced evaluation, particularly when false positives and false negatives have critical implications.

Figure 8.

Results of experiments with BERT, MedicoBERT and MedicoBERT with hyperparameter fine-tuning.

Table 6.

Experiment results for medical relation extraction of MedicoBERT with hyperparameter fine-tuning.

All experiments were conducted on a system equipped with an NVIDIA 3090 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 128 GB of RAM, and an Intel Xeon processor. Fine-tuning was computationally inexpensive, taking approximately 20 min for each configuration.

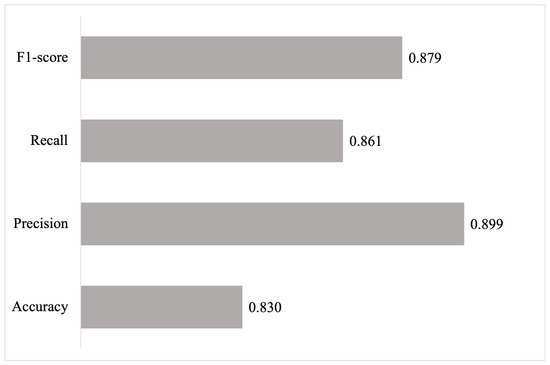

The pre-trained model was evaluated using an independent test set, consisting of 100 sentences extracted from Cowese and different from those used during training, to estimate its generalization ability. Figure 9 shows the results obtained for the metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

Figure 9.

Results of the evaluation of the medical relationship extraction model (100 sentences).

5. Discussion

The findings of this paper demonstrate that the use of LLMs specialized in the medical domain, combined with hyperparameter tuning techniques, can improve the extraction of medical relationships in Spanish texts. The accuracy achieved by our model (85.9%) places it within the performance range reported by related works. Table 7 presents a comparison with other systems, whose values range from 74% to 86% in similar tasks developed in English. This result suggests that, despite being trained on a smaller dataset and in a different language, the model achieves competitive performance in the classification task.

Table 7.

Comparison with related works.

It is essential to note that the comparison with previous work encompasses models that address multi-class classification tasks, whereas the model developed focuses on binary classification. This comparison is valid since all studies share the same objective: the automatic identification of relationships between medical entities. Therefore, the reported accuracy values provide an adequate reference for situating the performance of this model within the state of the art. The BERT model, configured according to the parameters reported in the literature, performs acceptably. However, when incorporating a pre-trained model specialized in the medical domain, a significant improvement is observed in all metrics, demonstrating a greater ability to capture relevant medical relationships.

The MedicoBERT model with fine-tuned hyperparameters achieved the highest values of precision and recall, suggesting improved identification capacity without an increase in false positives. Furthermore, an F1 score of 0.886 reflects an optimal balance between accuracy and sensitivity.

Similar accuracy values were observed for the MedicoBERT models with and without fine-tuning; nevertheless, there were noticeable differences in precision and F1 score. These differences may be attributed to a slight increase in errors within the majority classes, without compromising overall performance. Further improvements could be achieved through a more exhaustive hyperparameter search and an expanded training dataset.

These results show the importance of using domain-specific vocabularies, expert-validated datasets, and appropriate combinations of hyperparameters to optimize the performance of language models in biomedical tasks. The proposed approach facilitates its application in domains where the availability of annotated examples is limited, as is the case with medical texts in Spanish. This efficiency renders binary models a valuable point of departure for evaluating the viability of specialized approaches before scaling up to more complex multi-class scenarios.

Analysis of classification errors reveals that mistakes occurred in sentences where entities were semantically related but lacked an explicit linguistic connection. This suggests that the model struggles to infer implicit or context-dependent relationships. One possible solution would be to incorporate syntactic features, such as grammatical dependencies.

The findings indicate that medical LLMs exhibit a high degree of adaptability in the context of multilingual biomedical research and clinical decision support systems. Moreover, the explicit nature of the extracted relationships facilitates their incorporation into medical knowledge graphs, with each identified relationship defining the connections between different types of nodes. The system performs a classification function and adds structural value by representing medical knowledge in a form that is both interpretable and reusable.

The proposed phases of the methodology may apply to other languages and domains. However, the main limitation is the lack of available resources to replace employees in the medical field, including corpora in the target language, language-specific NER, and specialized pre-trained language models. This approach is particularly relevant in the case of Spanish due to the scarcity of biomedical resources available in this language, despite it being one of the most widely spoken languages in the world according to the Language Technology Promotion Plan [33]. Therefore, developing and validating systems in Spanish helps reduce this gap by allowing for the adaptation of the approach to other languages, following the same methodological phases and adjusting the relevant linguistic and domain-specific resources.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a methodology that combines traditional machine learning techniques, such as Random Forest for NER and pre-trained medical LLMs for relation extraction. It leverages the accuracy of classical methods in the detection stages, together with the contextual and semantic capabilities of LLMs in relation classification. Everything is applied to Spanish texts, focusing on three types of entities: anatomy, medications, and diseases.

The solution contributes to the generation of resources and the development of models applicable to real-world medical tasks. First, a set of medical data in Spanish was developed and validated by experts, ensuring the semantic and terminological quality of the relations. This resource is a significant contribution given the scarcity of available datasets of medical relations in Spanish.

Secondly, an automatic system has been designed to generate triplets in the form of relation (entity A, entity B) for a structured representation of medical knowledge. The graph constructed includes 4355 nodes and 12,294 relations extracted from Spanish medical texts. In future work, the triplets generated will be evaluated alongside the knowledge graph. Validating the connections between the nodes will allow the consistency of the relations to be verified, consequently assessing the quality of the automatically generated triplets. This process will not only strengthen the structural evaluation of the system but also allow us to identify areas for improvement in the automatic generation of relationships and the expansion of the medical knowledge graph.

For the extraction of relations, three configurations of pre-trained LLMs were tested: BERT, MedicoBERT, and MedicoBERT with hyperparameter fine-tuning using a Bayesian search. The adjusted model achieved a maximum precision of 90.6%, a recall of 88.9%, an F1 score of 88.6%, and an accuracy of 85.9%, comparable to the literature.

For future work, expert validation of the generated knowledge graph is proposed. In addition, it is suggested that the graph be enriched with new texts by applying the proposed approach and incorporating full-text medical articles to capture more enriching contexts. Finally, the methodology should be extended to new types of relationships between various medical entities. The generated and enriched graph serves as an aid for question-and-answer applications, thereby reducing the cost of information extraction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.G.-R., M.B., A.D.C.-R., J.A.R.-O. and J.P.-C.; methodology, M.B., A.D.C.-R. and G.A.G.-R.; software, G.A.G.-R., J.P.-C. and J.A.R.-O.; validation, M.B. and A.D.C.-R.; formal analysis, G.A.G.-R., J.P.-C. and J.A.R.-O.; investigation, G.A.G.-R.; resources, J.P.-C. and J.A.R.-O.; data curation, G.A.G.-R., J.A.R.-O. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.G.-R.; writing—review and editing, M.B., A.D.C.-R., J.A.R.-O. and J.P.-C.; visualization, G.A.G.-R.; supervision, M.B. and A.D.C.-R.; funding acquisition, M.B., A.D.C.-R. and J.A.R.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Azcapotzalco, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Texcoco, and the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación del Gobierno de México (SECIHTI), Mexico, with scholarship No. 881294.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nadeau, D.; Sekine, S. A survey of named entity recognition and classification. Lingvisticae Investig. 2007, 30, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, N.; Badaskar, S. A Review of Relation Extraction. 2007. Available online: https://nguyenbh.github.io/publication/bach-badaskar-2007/bach-badaskar-2007.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Padilla Cuevas, J.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.A.; Cuevas-Rasgado, A.D.; Mora-Gutiérrez, R.A.; Bravo, M. MédicoBERT: A Medical Language Model for Spanish Natural Language Processing Tasks with a Question-Answering Application Using Hyperparameter Optimization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, G. A Tutorial on Leveraging Knowledge Graphs for Web Search. In Information Retrieval. RuSSIR 2015; Braslavski, P., Markov, I., Volkovich, Y., Ignatov, D.I., Koltsov, S., Koltsova, O., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 573, pp. 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Entity relation extraction method based on fusion of multiple information and attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 6th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 11–14 December 2020; pp. 2485–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Cui, J. A relation extraction model based on BERT model in the financial regulation field. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Computer Science, Electronic Information Engineering and Intelligent Control Technology (CEI), Nanjing, China, 23–25 September 2022; pp. 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, L.; Xiang, Z.L. Biomedical relation extraction method based on ensemble learning and attention mechanism. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Lai, P.T.; Wei, C.H.; Arighi, C.N.; Lu, Z. BioRED: A rich biomedical relation extraction dataset. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshjou, R.; Vodrahalli, K.; Liang, W.; Novoa, R.A.; Jenkins, M.; Rotemberg, V.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Bailey, E.E.; Gevaert, O.; et al. Disparities in Dermatology AI Performance on a Diverse, Curated Clinical Image Set. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moine-Franel, A.; Mareuil, F.; Nilges, M.; Ciambur, C.B.; Sperandio, O. A comprehensive dataset of protein-protein interactions and ligand binding pockets for advancing drug discovery. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taboureau, O.; Nielsen, S.K.; Audouze, K.; Weinhold, N.; Edsgård, D.; Roque, F.S.; Kouskoumvekaki, I.; Bora, A.; Curpan, R.; Jensen, T.S.; et al. ChemProt: A disease chemical biology database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D367–D372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campillos-Llanos, L. First steps towards building a medical lexicon for Spanish with linguistic and semantic information. In Proceedings of the 18th BioNLP Workshop and Shared Task, Florence, Italy, 1 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Abacha, A.; Zweigenbaum, P. Automatic extraction of semantic relations between medical entities: A rule based approach. J. Biomed. Semant. 2011, 2, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Huang, L.; Yao, G.; Wang, Y.; Guan, H.; Bai, T. Extracting biomedical entity relations using biological interaction knowledge. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2021, 13, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.; Tanwani, S.; Patidar, C. Relation extraction between medical entities using deep learning approach. Informatica 2021, 45, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Yanping, C.; Huang, R.; Qin, Y.; Zheng, Q. A hierarchical convolutional model for biomedical relation extraction. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.P.; de Piñerez Reyes, R.G.; Bucheli, V.A. Support Vector Machines for Semantic Relation Extraction in Spanish Language. In Advances in Computing; Serrano C., J.E., Martínez-Santos, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 326–337. [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsaronis, G.; Balikas, G.; Malakasiotis, P.; Partalas, I.; Zschunke, M.; Alvers, M.R.; Weissenborn, D.; Krithara, A.; Petridis, S.; Polychronopoulos, D.; et al. An overview of the BIOASQ large-scale biomedical semantic indexing and question answering competition. BMC Bioinform. 2015, 16, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Penagos, C.; Nentidis, A.; Gonzalez-Agirre, A.; Asensio, A.; Armengol-Estapé, J.; Krithara, A.; Villegas, M.; Paliouras, G.; Krallinger, M. Overview of MESINESP8, a Spanish Medical Semantic Indexing Task within BioASQ 2020. In Proceedings of the 8th BioASQ Workshop A Challenge on Large-Scale Biomedical Semantic Indexing and Question Answering, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 8–11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- BIREME; PAHO; WHO. Health Sciences Descriptors: DeCS [Internet], 2025th ed.; Updated 2025 March 28; BIREME: São Paulo, Brazil; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca Virtual en Salud (BVS). Portal de la Biblioteca Virtual en Salud [Internet], 2025; BIREME: São Paulo, Brazil; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- García-Robledo, G.A.; Cuevas-Rasgado, A.D.; Bravo, M.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.A. Generation of Feature Vectors for Identifying Medical Entities in Spanish. Comput. Y Sist. 2025, 29, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramshaw, L.; Marcus, M. Text chunking using transformation-based learning. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Very Large Corpora, Cambridge, MA, USA, 30 June 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Z.S. Distributional structure. WORD 1954, 10, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Robledo, G.A.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.A.; Bravo, M.; Cuevas Rasgado, A.D. MedRel_Spanish (Version 1). 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15320867 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia Contributors. EnglishWikipedia, 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Wikipedia (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Zhu, Y.; Kiros, R.; Zemel, R.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Urtasun, R.; Torralba, A.; Fidler, S. Aligning books and movies: Towards story-like visual explanations by watching movies and reading books. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Krallinger, M.; Armengol-Estapé, J.; De Gibert, O.; Carrino, C.P.; Gonzalez-Agirre, A.; Gutiérrez-Fandiño, A.; Villegas, M. Spanish Biomedical Crawled Corpus. 2021. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4561971 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Wang, L.L.; Lo, K.; Chandrasekhar, Y.; Reas, R.; Yang, J.; Burdick, D.; Eide, D.; Funk, K.; Katsis, Y.; Kinney, R.; et al. CORD-19: The Covid-19 Open Research Dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10706v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ministerio de Energía, Turismo y Agenda Digital. Plan de Impulso de las Tecnologías del Lenguaje; El Ministerio de Energía, Turismo y Agenda Digital: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).