Evaluating the Performance of Different Rainfall and Runoff Erosivity Factors—A Case Study of the Fu River Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Calculation Method of Erosion Dynamic Factor

3.2.1. Rainfall Erosivity Factor

3.2.2. Runoff Erosion Power

3.2.3. Rainfall and Runoff Erosivity Factor

3.3. Evaluation Parameters

4. Results and Analysis

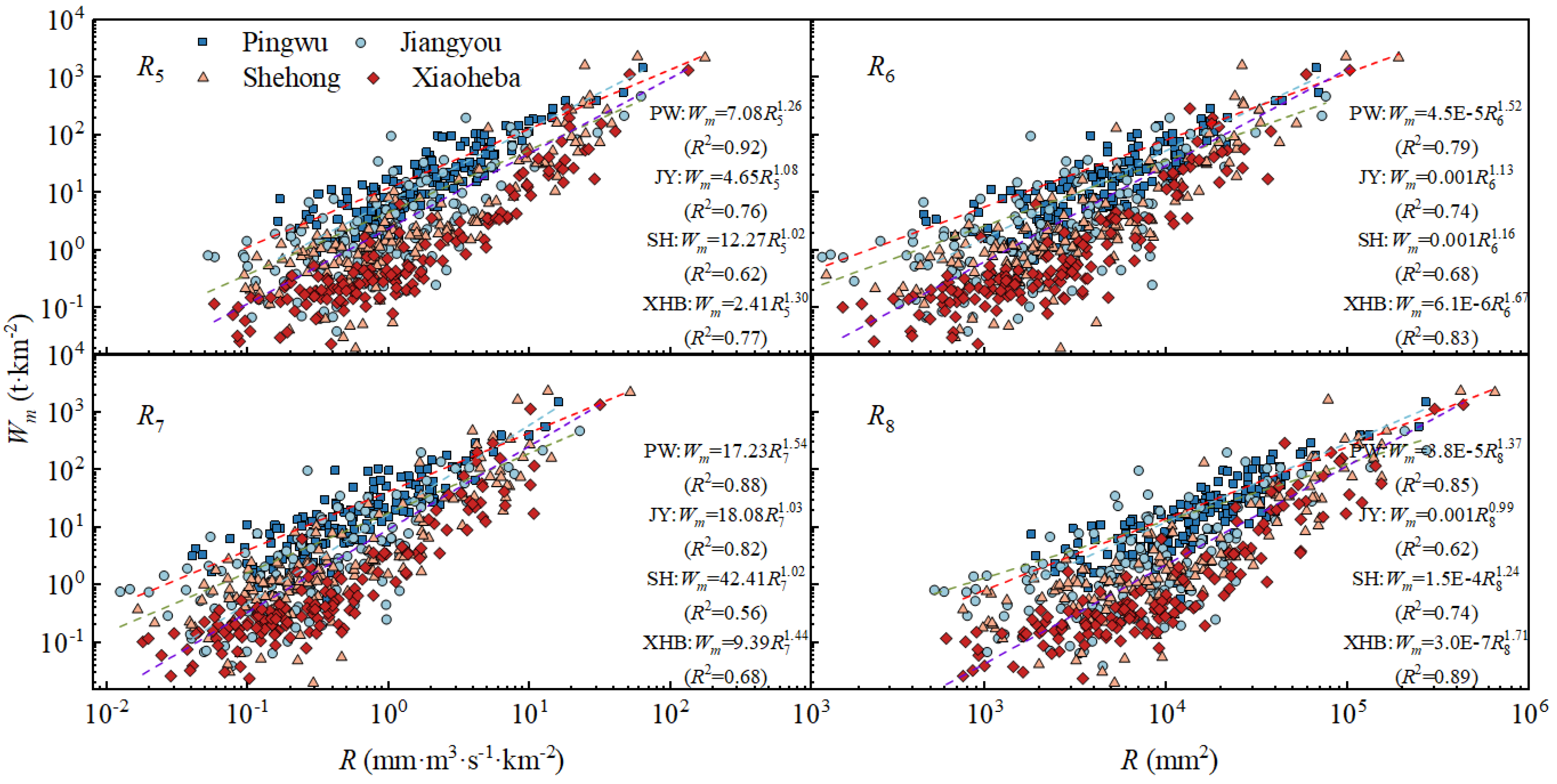

4.1. The Relationship Between Different R Factors and Sediment Transport Modulus

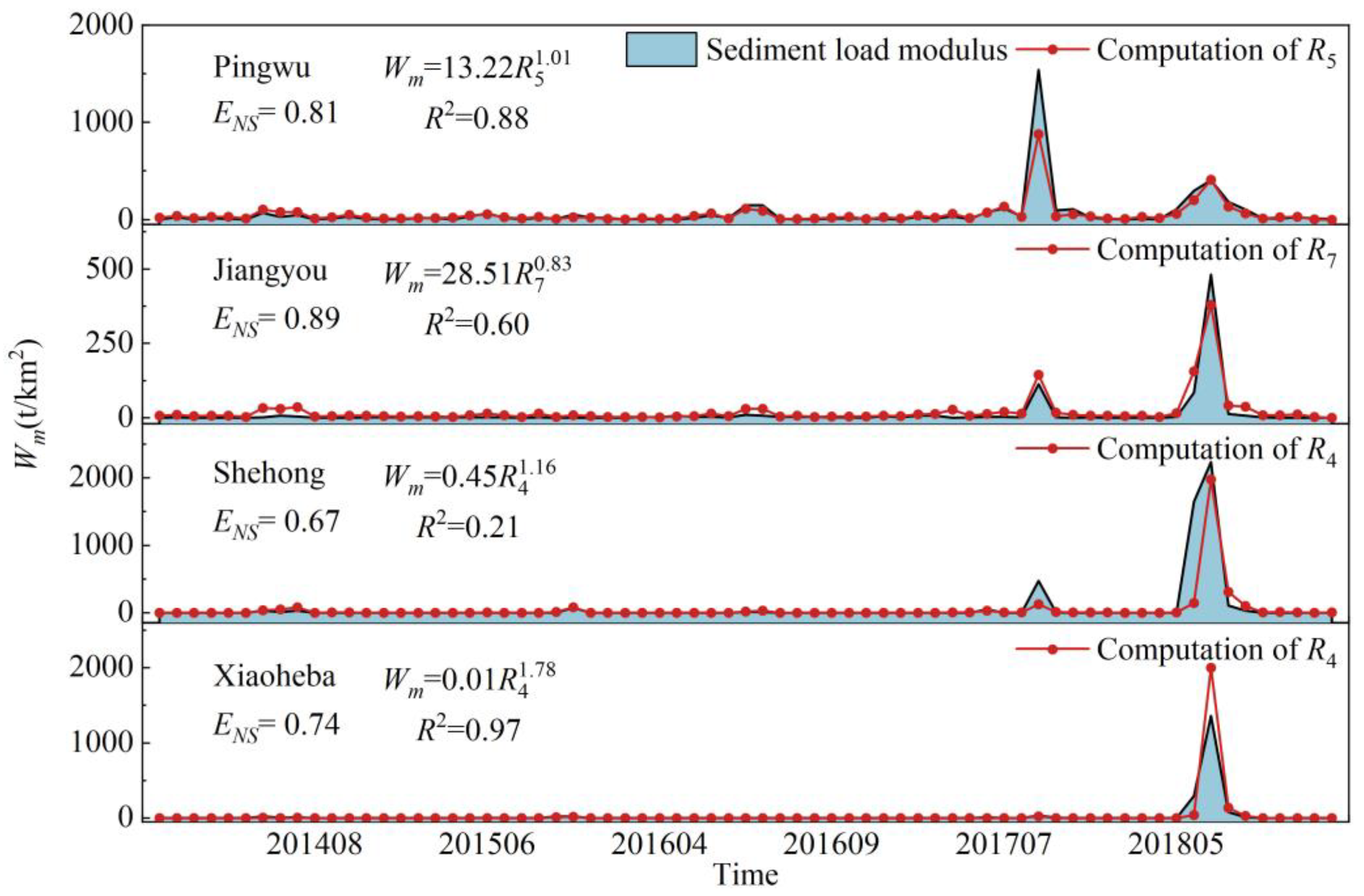

4.2. Simulation of Sediment Discharge

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borrelli, P.; Robinson, D.A.; Fleischer, L.R.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C.; Alewell, C.; Meusburger, K.; Modugno, S.; Schütt, B.; Ferro, V.; et al. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Daryanto, S.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Metacoupling supply and demand for soil conservation service. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Montanari, A. Global and Regional Increase of Precipitation Extremes Under Global Warming. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.; Ángel, J.R.; Saito, Y.; Overeem, I.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Wang, H.; Olago, D. Earth’s sediment cycle during the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, D.E.; Fang, D. Recent trends in the suspended sediment loads of the world’s rivers. Glob. Planet. Change 2003, 39, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J. Anthropogenic stresses on the world’s big rivers. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Milliman, J.D.; Xu, K.H.; Deng, B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Luo, X.X. Downstream sedimentary and geomorphic impacts of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Earth Sci. Rev. 2014, 138, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Jin, Z.; Guo, L.; Lu, J.; Ren, S.; Zhou, Y. On the cumulative dam impact in the upper Changjiang River: Streamflow and sediment load changes. Catena 2020, 184, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu, X.; Overeem, I.; Walling, D.E.; Syvitski, J.; Kettner, A.J.; Bookhagen, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T. Exceptional increases in fluvial sediment fluxes in a warmer and wetter High Mountain Asia. Science 2021, 374, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Girolamo, A.M.; Pappagallo, G.; Lo Porto, A. Temporal variability of suspended sediment transport and rating curves in a Mediterranean river basin: The Celone (SE Italy). Catena 2015, 128, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Dadson, S.J.; Bowes, M.J.; Whitehead, P.G. Seasonal and Interannual Changes in Sediment Transport Identified through Sediment Rating Curves. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2017, 22, 06016016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Zong, X.; Ye, S.; Gao, J.; Hong, Y. Dominant mechanism for annual maximum flood and sediment events generation in the Yellow River basin. Catena 2020, 187, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercruysse, K.; Grabowski, R.C.; Rickson, R.J. Suspended sediment transport dynamics in rivers: Multi-scale drivers of temporal variation. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 166, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pszonka, J.; Schulz, B. SEM Automated Mineralogy applied for the quantification of mineral and textural sorting in submarine sediment gravity flows. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2022, 38, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pszonka, J.; Godlewski, P.; Fheed, A.; Dwornik, M.; Schulz, B.; Wendorff, M. Identification and quantification of intergranular volume using SEM automated mineralogy. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 162, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.W.; Miao, W.; Wang, Z.L.; Li, D.X. Study on sediment transport law of flood event in different areas of the Jialing River basin. Adv. Water Sci. 2022, 33, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.X.Y.J. Study on characteristics and causes of sediment deposition in Three Gorges Reservoir in 2020. Yangtze River 2022, 53, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.X. Effects of Climate and Land Use and Land Cover Change on Streamflow and Sediment in Fu River Watershed. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.Z. Study on Water-Sediment Change and Erosion Energy Spatial Distribution in Fujiang River Basin Based on SWAT Model. Master’s Thesis, Xi′an University of Technology, Xi′an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Ju, H. Prediction of watershed sediment transport for single rainstorm based on runoff erosion power. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2008, 3, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting rainfall-erosion losses from cropland east of the Rocky Mountains. In Agricultural Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1965; Volume 282. [Google Scholar]

- Efthimiou, N. Evaluating the performance of different empirical rainfall erosivity (R) factor formulas using sediment yield measurements. Catena 2018, 169, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, K.; Das Bhattacharya, S. A Review of RUSLE Model. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2020, 48, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.B.; Liu, B.Y. Rainfall erosivity estimation using daily rainfall amounts. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2002, 6, 705–711. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K.X.; Ju, H.; Cheng, S.D. Study on a comparison of runoff erosion power and rainfall erosivity for single rainstorm event under different spatial scales. J. Northwest A F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2009, 37, 204–208, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.L. Research on the Impact of Changing Underlying Surface and Heavy Rainfall on Watershed Soil Erosion. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, Chia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Miao, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, D. Characteristics of runoff and sediment load during flood events in the Upper Yangtze River, China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Miao, W.; Xu, Z. Analysis of the sediment sources of flood driven erosion and deposition in the river channel of the Fu River Basin. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2023, 38, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, S.Y.; Wang, H.; Lei, X.H.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhao, Q.D. CMADS datasets and its application in watershed hydrological simulation: A case study of the Heihe River Basin. Pearl River 2016, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, B.; Liu, B.Y. Estimation of rainfall erosivity using rainfall amount and rainfall intensity. Geogr. Res. 2002, 3, 384–390. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Jia, L.; Wang, B. Simulation accuracy of runoff erosion power-sediment transfer model at different time scales. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 27, 1–7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.W.; Zhu, J.; Guo, W.W. Estimation of monthly rainfall erosivity based on rainfall amount and rainfall time: A case study in hilly and gully area of Loess Plateau in Northern Shaanxi. Sci. Soil Water Conserv. 2007, 6, 8–14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Mo, S.; Yu, K.; Li, P.; Li, Z. Analysis on the relationship between runoff erosion power and sediment transport in the Fujiang River basin and its response to land use change. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortesa, J.; Ricci, G.F.; García-Comendador, J.; Gentile, F.; Estrany, J.; Sauquet, E.; Datry, T.; De Girolamo, A.M. Analysing hydrological and sediment transport regime in two Mediterranean intermittent rivers. Catena 2021, 196, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; He, X.; Chen, G.; Tao, H. Change in sediment load of the Yangtze River after Wenchuan earthquake. J. Mt. Sci. 2010, 7, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, Y.; Ni, S.; Ma, G.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, G.; Yan, L.; Yan, Z. Increased sediment discharge driven by heavy rainfall after Wenchuan earthquake: A case study in the upper reaches of the Min River, Sichuan, China. Quat. Int. 2014, 333, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Zeng, C.; Wang, Y.; Qiangba, C.; Deji, B.; Awang, D.; Qiong, N. Investigating climate change impacts on runoff and sediment transport processes in the midstream of the Yarlung Tsangpo river based on hydrological simulation. Catena 2025, 254, 108920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Mei, X.; Darby, S.E.; Lou, Y.; Li, W. Fluvial sediment transfer in the Changjiang (Yangtze) river-estuary depositional system. J. Hydrol. 2018, 566, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kandekar, A.M.; Sangode, S.J. Natural and anthropogenic effects on spatio-temporal variation in sediment load and yield in the Godavari basin, India. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binh, D.V.; Kantoush, S.; Sumi, T. Changes to long-term discharge and sediment loads in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta caused by upstream dams. Geomorphology 2020, 353, 107011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluation Parameters | Formula | Evaluation Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| ENS | (−∞, 1] | |

| ρ | [−1, 1] | |

| R2 | [0, 1] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, W.; Wu, Q.; Ou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Liu, C.; Lin, X. Evaluating the Performance of Different Rainfall and Runoff Erosivity Factors—A Case Study of the Fu River Basin. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111353

Miao W, Wu Q, Ou Y, Zhang S, Hu X, Liu C, Lin X. Evaluating the Performance of Different Rainfall and Runoff Erosivity Factors—A Case Study of the Fu River Basin. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111353

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Wei, Qiushuang Wu, Yanjing Ou, Shanghong Zhang, Xujian Hu, Chunjing Liu, and Xiaonan Lin. 2025. "Evaluating the Performance of Different Rainfall and Runoff Erosivity Factors—A Case Study of the Fu River Basin" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111353

APA StyleMiao, W., Wu, Q., Ou, Y., Zhang, S., Hu, X., Liu, C., & Lin, X. (2025). Evaluating the Performance of Different Rainfall and Runoff Erosivity Factors—A Case Study of the Fu River Basin. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111353