Abstract

Monocular 3D object detection (Mono3D) is essential for autonomous driving and augmented reality, yet its performance degrades significantly at night due to the scarcity of annotated nighttime data. In this paper, we investigate the use of style transfer for nighttime data augmentation and evaluate its effect on individual components of 3D detection. Using CycleGAN, we generated synthetic night images from daytime scenes in the nuScenes dataset and trained a modular Mono3D detector under different configurations. Our results show that training solely on style-transferred images improves certain metrics, such as AP@0.95 (from 0.0299 to 0.0778, a 160% increase) and depth error (11% reduction), compared to daytime-only baselines. However, performance on orientation and dimension estimation deteriorates. When real nighttime data is included, style transfer provides complementary benefits: for cars, depth error decreases from 0.0414 to 0.021, and AP@0.95 remains stable at 0.66; for pedestrians, AP@0.95 improves by 13% (0.297 to 0.336) with a 35% reduction in depth error. Cyclist detection remains unreliable due to limited samples. We conclude that style transfer cannot replace authentic nighttime data, but when combined with it, it reduces false positives and improves depth estimation, leading to more robust detection under low-light conditions. This study highlights both the potential and the limitations of style transfer for augmenting Mono3D training, and it points to future research on more advanced generative models and broader object categories.

1. Introduction

Monocular 3D object detection (Mono3D) has become a cornerstone of computer vision with applications in autonomous driving, robotics, and augmented reality. Compared to LiDAR or stereo-based systems, monocular approaches are attractive due to their lower hardware cost and simpler deployment. However, estimating depth, orientation, and dimensions from a single image remains extremely challenging, especially in conditions where visual cues are degraded, such as at night.

Despite recent advances in state-of-the-art methods including GUPNet [1], MonoFlex [2], and M3D-RPN [3] performance continues to deteriorate significantly under low-light conditions. Current large-scale benchmarks such as KITTI [4] and NuScenes [5] are heavily imbalanced toward daytime scenes, with night images often representing less than 15% of the data. This imbalance leads to domain shift, where models optimized for daytime fail to generalize to nighttime environments. Glare from headlights, reduced object visibility, and sensor noise further exacerbate the problem, resulting in unreliable depth predictions, unstable orientation estimates, and poor recall.

Several strategies have been proposed to bridge this domain gap. Domain adaptation techniques (e.g., DA-3Ddet [6], MonoGDG [7], STMono3D [8]) modify feature representations or employ pseudo-labeling across domains, but these require model architectural changes and significant tuning. An alternative is data-level augmentation, particularly style transfer, which can generate synthetic nighttime images from abundant daytime data. While style transfer has shown benefits in related tasks such as depth estimation and semantic segmentation, its impact on the different components of monocular 3D object detection has not been thoroughly studied.

In this work, we critically evaluate whether style transfer can compensate for the scarcity of nighttime data in Mono3D detection. Specifically, we address the following research questions:

- RQ1: How does style transfer affect individual detection components, including 2D bounding boxes, depth estimation, orientation, center localization, and dimension prediction?

- RQ2: Can synthetic night images alone provide meaningful improvements, or must they be combined with real nighttime data to achieve robust performance?

- RQ3: How do style transfer-based datasets compare with conventional augmentation and domain adaptation approaches in terms of practicality and effectiveness?

By answering these questions, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the role of style transfer in nighttime detection. Our contribution is not to propose a new detection architecture, but to systematically assess the extent to which synthetic night data can improve existing monocular 3D models and to highlight the conditions under which style transfer is most beneficial.

2. Related Work

The goal of style transfer is to convert images between domains while maintaining the original image’s characteristics. Similar ideas underlie these techniques, such as using adversarial networks and certain loss functions to guarantee realistic results. However, they are different in their principles, data requirements, and architectural layout. We examine three SOTA methods in this subsection: CycleGAN [9], Pix2pix [10], and img2img-turbo [11]. All three methods use Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). GANs are image generation methods that produce realistic artificial images by teaching a generator to produce images that look as close as possible to the real data, and a discriminator to distinguish between real and artificial images. Firstly, these methods have different dataset requirements. Pix2pix [10] is based on paired datasets, where there is an output image for every input image. On the other hand, CycleGAN [9] is specifically made for unpaired environments, for situations where getting paired data is not possible. To work without paired data, CycleGAN [9] uses a cycle consistency loss. This loss guarantees that translating an image to the target domain and back to the source domain reconstructs the original image so that structural and semantic features are preserved (this is particularly crucial for 3D monocular object detection).

Img2img-turbo [11] expands on these ideas while resolving the efficiency issues with diffusion-based and conventional GAN approaches. Img2img-turbo [11] uses a single-step inference technique, which drastically lowers the computational resources necessary during training, unlike CycleGAN [9] and Pix2pix [10]. This is accomplished by using adversarial objectives to modify previously trained text-conditional diffusion models for picture translation. Furthermore, img2img-turbo [11]’s design enables it to work well in both paired and unpaired contexts, in contrast to the two earlier approaches.

Despite their differences, these techniques seek to maintain the input image’s fundamental structure throughout the translation process. Because of this common objective, all three approaches are appropriate for 3D monocular object detection, where preserving the integrity of the input image is crucial. In our particular situation, we chose to mostly employ CycleGAN [9] since we did not have access to a paired dataset with 3D ground truth and because maintaining the original image’s characteristics is crucial for our 3D monocular object recognition task.

Although depth estimation is different from monocular 3D object detection, it shares some of the same difficulties, and its applications to applied style transfer are relevant to our study. Due to domain shifts, illumination changes, and photometric irregularities, depth estimation is particularly difficult in challenging environments such as at night or in bad weather. The application of domain adaptation and style transfer strategies has become a viable remedy where conventional approaches often fall short in these circumstances.

The use of image translation to create synthetic datasets that match the characteristics of difficult situations is a recurring theme in state-of-the-art techniques. For example, ref. [12] used a generative adversarial network (GAN) to create artificial night images from daytime photographs in the KITTI [4] dataset. A pre-trained depth estimation network was then refined using these artificial images, resulting in improved performance at night. The usefulness of synthetic data in tackling domain-specific problems has also been demonstrated by other techniques such as ADFA [13] and ADDS-DepthNet [14], which use GANs such as CycleGAN [9] to generate night photographs for domain adaptation.

Feature matching for domain adaptation is another common strategy. ADFA [13] focused on using a PatchGAN-based adversarial learning framework to adapt the feature representations of night photographs to those of day photographs. The technique allowed pre-trained daytime depth decoders to be efficiently reused for night images by adapting features rather than network outputs. The domain-separated framework used by ADDS-DepthNet [14], on the other hand, divided features into invariant (texture-specific) and private (illumination-specific) components. This separation preserved important depth-related information while reducing the detrimental effects of domain-specific variables such as lighting.

Several approaches have used quality-aware learning techniques to further improve the adaptation process. An image quality adaptation technique was presented by ITDFA [15] to assess the quality of GAN-generated images and modify the loss weights accordingly. By addressing the instability of the synthetic data, this method ensured that high-quality translations improved the learning capabilities of the depth models. Similarly, GASDA [16] integrates both synthetic and real data into an end-to-end training framework by using both synthetic depth labels and epipolar geometry constraints in real images.

Although their effectiveness varies depending on the situation, these techniques also rely on photometric consistency losses. For example, due to uneven illumination, photometric losses perform poorly in dark environments but well in daylight photographs. This limitation was overcome by techniques such as ADDS-DepthNet [14] and GASDA [16], which included other limitations such as orthogonality and similarity losses, and focused on preserving complementary features and geometric consistency.

Two of the earliest techniques for training depth estimation models with synthetic data and style transfer are [17,18]. Ref. [17] uses a lightweight architecture with skip connections, while ref. [18] showed the effectiveness of style transfer and adversarial training for pixel-perfect depth detection.

Domain adaptation (DA) refers to methods developed to mitigate performance degradation in monocular 3D object recognition (Mono3D) when applied across domains with different camera specifications and scene characteristics. The advances made in this area are still relevant, although we do not use DA in this study.

While MonoEF [19] uses vanishing points and horizon detection to recover features from perturbations, ensuring robustness in uneven road settings, MonoGDG [7] minimizes camera discrepancies via geometry-based image reprojection, unifying intrinsic parameters and FOVs. MonoGDG [7] also uses feature disentanglement, which preserves geometry while preventing negative transfer by separating domain-specific and domain-shared features.

STMono3D [8] presents a geometry-aligned multi-scale strategy to address depth shift, ensuring consistent geometry across domains, and uses adaptive pseudo-labels with quality-aware monitoring and confidence-based filtering to refine target domain training. Ref. [20] uses stereo algorithms to generate confidence-weighted pseudo-labels for unsupervised fine-tuning.

Finally, DA-3Ddet [6] reduces inconsistencies caused by inaccurate depth estimation by aligning pseudo-LiDAR features with real LiDAR features using a context-aware foreground segmentation module.

This section reviews prior work on style transfer, depth estimation with synthetic data, and domain adaptation for 3D perception, emphasizing their relevance and limitations in addressing nighttime monocular 3D object detection.

2.1. Style Transfer Methods

The goal of style transfer is to convert images between domains while preserving structural and semantic consistency. Common approaches rely on adversarial networks and specialized loss functions to ensure realistic translations. We focus on three representative methods: CycleGAN [9], Pix2pix [10], and img2img-turbo [11]. All three are based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), where a generator learns to produce realistic images while a discriminator distinguishes real from synthetic samples.

Pix2pix [10] requires paired datasets, making it impractical for unpaired domains such as day-to-night translation. In contrast, CycleGAN [9] was specifically designed for unpaired image-to-image translation using a cycle-consistency loss to reconstruct the source image after translation. This property is crucial for monocular 3D object detection, where geometric and semantic integrity must be maintained. Img2img-turbo [11] builds upon these ideas, introducing a one-step inference process to improve computational efficiency compared to conventional GAN and diffusion-based models. However, its implementation requires large-scale resources, and reproducibility remains limited in open-source settings. Recent works such as Asymmetric CycleGAN [21] and PCA-SRGAN [22] have introduced architectural improvements to enhance realism and feature diversity in image-to-image translation and super-resolution. While these models achieve superior texture detail and convergence stability, they typically require paired or domain-specific supervision and larger computational budgets. In the context of this study, our focus was on the transferability of visual style rather than generative fidelity, making CycleGAN [9] a practical and interpretable baseline. Nevertheless, incorporating asymmetric architectures or orthogonal feature regularization represents a promising future direction for improving nighttime scene translation without sacrificing geometric consistency.

Despite their differences, all these methods share the objective of preserving scene structure during translation. In our case, we adopted CycleGAN [9] because (1) it does not require paired data, (2) it offers stable geometric preservation, and (3) it has proven effective in similar low-light translation tasks. The choice reflects a balance between realism, efficiency, and experimental reproducibility.

2.2. Depth Estimation Using Style Transfer

Depth estimation and monocular 3D object detection share similar challenges, particularly when faced with domain shifts caused by lighting and weather variations. Several studies have explored the use of GAN-based style transfer for improving depth prediction under adverse conditions. For instance, Khalefa et al. [12] employed CycleGAN to generate artificial night images from KITTI [4] daytime data, improving nighttime depth estimation accuracy. Similarly, ADFA [13] and ADDS-DepthNet [14] used adversarial feature adaptation to align day and night domains, while ITDFA [15] and GASDA [16] introduced quality-aware or geometry-consistent constraints to stabilize learning from synthetic data.

These works demonstrate that style transfer and domain adaptation can reduce illumination-related errors by aligning photometric and structural features. However, their primary focus remains on dense depth prediction. While these methods highlight the value of synthetic data for improving perception under low-light conditions, they do not analyze its impact on multi-task monocular 3D object detection, which jointly estimates depth, orientation, and object dimensions. Addressing this unexplored gap is one of the main goals of our study.

2.3. Domain Adaptation

Domain adaptation (DA) aims to mitigate performance degradation when models are applied across different domains with varying camera parameters or scene conditions. Recent advances have produced strong results for monocular 3D detection. MonoEF [19] recovers geometric features via horizon detection, while MonoGDG [7] minimizes camera discrepancies through geometry-guided reprojection and feature disentanglement. STMono3D [8] employs adaptive pseudo-labeling and confidence-based filtering for improved target-domain training, and DA-3Ddet [6] aligns pseudo-LiDAR and real LiDAR features using context-aware segmentation.

Although DA approaches effectively reduce domain gaps, they typically require architectural modifications, additional supervision, or complex fine-tuning procedures. In contrast, style transfer operates purely at the data level and can be applied to any existing detector without retraining the model or altering its architecture. This flexibility makes it an appealing alternative for augmenting datasets under unbalanced day/night distributions.

In summary, prior works demonstrate the potential of domain adaptation and style transfer for improving perception across varying lighting conditions. However, no prior research has systematically evaluated how style-transferred images influence each component of monocular 3D object detection under nighttime conditions. Our work addresses this gap by quantitatively analyzing the contribution of style-transferred and mixed datasets on detection precision, depth estimation, and orientation performance.

3. Method

3.1. Applying the Style Transfer

We decided to use the NuScenes [5] dataset for this study because of its 3D ground truth and high-quality image resolution, which make it appropriate for training 3D monocular object detection models. It is useful for investigating the difficulties involved in object detection in different lighting circumstances because it includes photos taken both during the day and at night. This allows us to use it to test how well style transfer might improve the performance of monocular 3D object detection models.

However, despite NuScenes having both daytime and nighttime images, the majority of the images were taken during the day, with nighttime images making up only 13% of the entire dataset. When training models that need to generalize effectively in both day and night situations, this imbalance might be problematic because it may result in daytime overfitting.

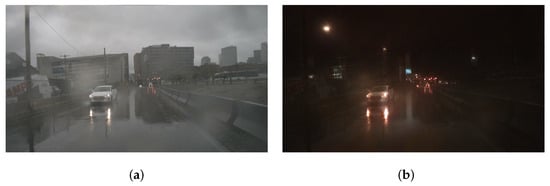

Additionally, as shown in Figure 1, there are a few major issues with some of the nighttime photos that are currently available from the NuScenes dataset for training.

Figure 1.

Example of challenges with nighttime images on the NuScenes [5] dataset. (a) Strong headlights completely obscure the opposing vehicle; (b) Rain droplets on the camera create large reflections.

- Accurate recognition is made more difficult by powerful headlights, which create a large bloom effect in many nighttime photos, obscuring some areas of the car.

- Raindrops on the camera glass can cause significant distortions/reflections in some photos, making them difficult to use if not outright unusable for object detection.

To compensate for the small number of night images and their shortcomings, we used style transfer to add more artificial night images to the training set. We chose to use CycleGAN [9] for style transfer for the reasons explained in Section 3. The CycleGAN model was trained for 100 epochs using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of and . A batch size of 1 and an input image resolution of pixels were used. The training was conducted on an NVIDIA A100 GPU (80 GB) hosted on the regional computing cluster CRIANN (Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, France).

We employed the standard CycleGAN loss functions, including the adversarial loss to ensure realism in generated images, the cycle-consistency loss to preserve structural content, and the identity loss to maintain illumination consistency. Both generator and discriminator losses converged after approximately 80 epochs, indicating training stability. To ensure data quality, images showing visual artifacts such as ghosting, blurring, or overexposure were filtered out before inclusion in the final dataset.

When we used it for day-to-night style transfer, we saw that CycleGAN [9] produced visually realistic night images. The results are shown in Figure 2. It is important to note that CycleGAN does not require paired images for training; the source and target domains are learned independently. The paired examples shown in Figure 2 are only for visualization. The transferred photos retained the overall appearance of the cars, which allowed them to be used as training data. The style transfer was strong enough to produce excellent images that retained the realism of a nighttime environment, even when the images contained weather-related aberrations such as rain or an overcast sky. However, we often saw the generation of ’ghost’ lights in the sky as a result of the style transfer. Whilst this was noticeable, we believe that it did not significantly affect the overall quality of the images (for detection purposes), as these lights were far away from the vehicles that the model needed to detect.

Figure 2.

Example of unpaired day-to-night style transfer using CycleGAN. (a) Original Image; (b) Image after Style Transfer.

However, the style transition from night to day was much less successful. As we can see in Figure 3, the transferred images only resembled the original night images with increased contrast and brightness. They were oversaturated and over-contrasted, making them look unrealistic and out of sync with actual daylight settings. In addition, the quality of the created daytime images was further degraded by the style transfer process, which increased the visual noise in the original nighttime images. Because of these problems, we decided to focus only on the day-to-night style transfer, which was more appropriate for our purpose and produced more encouraging results.

Figure 3.

Night-to-day style transfer. (a) Original Image; (b) Image after Style Transfer.

3.2. Dataset Configuration

To test the effect of style transfer on 3D monocular object detection, we made many training and validation datasets from the NuScenes dataset. Furthermore, we restricted our experiments to three object categories: car, pedestrian, and cyclist.

This choice is motivated by several factors. First, these classes are the most widely used for benchmarking in datasets such as KITTI and nuScenes, allowing direct comparison with prior works in monocular 3D object detection. Second, they represent the most safety-critical agents in autonomous driving scenarios, where accurate perception directly impacts collision avoidance and decision-making. Finally, other object categories in nuScenes (such as barriers, buses, or construction vehicles) appear too infrequently to provide sufficient samples for stable training and statistical evaluation. Including them would introduce high class imbalance and unreliable metrics, which would obscure the analysis of the effects of style transfer. Focusing on these three core classes, therefore, ensures both experimental consistency and relevance to real-world applications. The NuScenes dataset is sequential in nature, consisting of multiple images captured continuously within each driving scene. To prevent data contamination—where correlated frames from the same sequence could appear in both training and validation sets—we ensured that all images belonging to a given scene were assigned exclusively to one subset. Furthermore, during the style transfer process, not all GAN-generated images exhibited sufficient visual quality or structural consistency. To maintain data integrity, we implemented a filtering step to remove suboptimal samples. Low-quality or artifact-heavy images were automatically detected and excluded using a combination of brightness and contrast thresholds, followed by manual inspection of random subsets. This ensured that only visually coherent, geometrically consistent images were retained for training. After filtering, the final dataset consisted of 20,127 daytime and 3233 nighttime images, totaling 23,360 high-quality samples used for model development and evaluation. In the first configuration, we tested the impact of style transfer when no original nighttime images were included in the training set:

In the first configuration, we focused on isolating the impact of style transfer when no original nighttime images were included in the training set:

- Validation Set: All the 3233 original nighttime photos

- Day Training Set: All the 20,127 original daytime images

- Night Training Set: All the 20,127 daytime images were transformed into synthetic nighttime images (using CycleGAN)

- Combined Training Set: All the original 20,127 daytime images with the 20,127 style-transferred nighttime images, resulting in a total of 40,254 images.

These configurations enabled us to evaluate the effectiveness of synthetic nighttime images alone and in combination with original daytime or nighttime data. All the configurations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Datasets used in both configurations.

In the second configuration, we added a subset of original nighttime images into the training datasets to test how a combination of real and synthetic nighttime images impacts detection performance:

- Validation Set: Half of the original nighttime images (1616 images)

- Mixed Day Training Set: 20,127 daytime images and 1617 original nighttime images

- Mixed Night Training Set: 20,127 CycleGAN-transformed synthetic nighttime images and 1617 original nighttime images

- Mixed Combined Training Set: 20,127 daytime images, 20,127 CycleGAN-transformed nighttime images, and 1617 original nighttime images, resulting in a total of 41,871 images

These configurations allowed us to test the effectiveness of synthetic nighttime images alone and in combination with original daytime or nighttime data. The Table 1 compares both configurations.

3.3. Evaluation Protocol

To test the effects of style transfer on 3D monocular object detection performances, we employ a combination of standard 2D metrics and individualized 3D metrics, rather than relying on a single 3D score metric. This allows us to understand the impact of style transfer on the various metrics of 3D detection rather than having a single score metric without explanation.

We use the following metrics:

- Precision: Indicates how well the model reduces false positives by calculating the percentage of accurately recognized objects among all detections

- Recall: Indicates how well the model minimizes false negatives by measuring the percentage of ground truth items it detects

- Average Precision (AP): Assessed at two Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds: 50% and 95%

- Depth Error: Indicates how accurately the model estimates object distances by measuring the absolute error between predicted and ground truth depth values.

- Center Offset: Indicates the accuracy of localization in three dimensions by calculating the distance between the centers of the predicted and ground truth objects.

- Dimension Score (DS): Indicates how accurate the projected object dimensions are.

- Orientation Score (OS): Indicates how accurately the model predicts an object’s orientation in three dimensions.

The combined use of 2D and 3D metrics served two main purposes: First, we can determine which particular elements of the 3D detection pipeline were most affected by style transfer by examining them separately. Secondly, we can modify the hyperparameters to make the model focus on some specific metrics using the previous feedback.

Finally, the evaluation process consisted of training the models on the various training datasets (listed in the Section 3.2 paragraph) and testing them on their respective validation sets. We tested how well style transfer addressed the domain gap between day and night situations by comparing performance across configurations (day-only, night-only, and mixed datasets).

4. Experimental Results

4.1. First Configuration

In the first configuration, the training data consisted exclusively of either synthetic nighttime images generated by CycleGAN or original daytime photographs. No real nighttime images were included in this setup. As shown in Table 2, the model achieved relatively low performance across all metrics, particularly in depth estimation and mAP, indicating limited generalization under this training condition.

Table 2.

Three-dimensional object detection results on the first dataset configuration. All values correspond to evaluation on the same nighttime test set. Best results per metric (across all configurations) are highlighted in bold.

The model trained on style-transferred nighttime images achieved higher performance on 2D recognition metrics, particularly mAP@0.95, and exhibited lower depth estimation errors compared to the model trained solely on daytime data. However, it performed worse on the orientation, classification, and distance similarity (OS, CS, and DS) metrics relative to the daytime-trained model.

The combined dataset, which included both daytime and style-transferred nighttime images, produced the best overall performance in terms of depth estimation and two-dimensional metrics. Nevertheless, the results remained insufficiently precise for practical deployment.

The limited generalization observed in this configuration likely stems from the absence of real nighttime data and the strong imbalance between the number of daytime and nighttime training samples. This first experiment demonstrates that style-transferred images can enhance detection performance when combined with daytime data but cannot fully replace real nighttime images, which is a predictable outcome. To address this limitation, the second configuration incorporates real nighttime samples and reduces the disparity between day and night image counts (including style-transferred samples). This adjustment was intended to prevent overfitting toward daytime scenes. The corresponding results are presented in the next subsection (Section 4.2).

4.2. Second Configuration

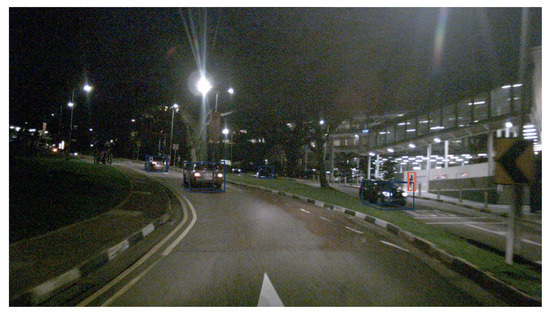

In the second configuration, the training dataset was expanded to include original nighttime images while reducing the proportion of daytime samples. This adjustment was made to improve the balance between day and night data and to mitigate overfitting toward daytime scenes. The corresponding results are reported in Table 3 for the car class and Table 4 for the pedestrian class. Since certain datasets required longer training durations to achieve convergence, the number of training epochs is also indicated in each table. In addition, Figure 4 provides a qualitative example of detections obtained from a model trained under this second configuration using style-transferred nighttime images.

Table 3.

Three-dimensional object detection results for the car class using the same model trained under different data configurations (Day, Night, and Combined) and epoch counts.

Table 4.

Three-dimensional object detection results for the pedestrian class using the same model trained under different data configurations (Day, Night, and Combined) and epoch counts.

Figure 4.

Detection results of the model trained on the second configuration style-transferred nighttime images on NuScenes [5].

Firstly, when looking at the result in Table 3, we can see that the ones obtained in this second configuration are significantly better than those obtained in the first configuration. Decent AP@0.95 scores indicate that the style-transformed datasets performed well in terms of precision. This means that the use of style transfer reduced false positives. Style transfer also increased the accuracy of depth predictions compared to models trained without synthetic night images.

Models trained on original daytime image datasets had better recall results, resulting in higher AP@0.5 scores. False negatives seem to have been reduced by this training without style transfer. The difference between AP@0.5 and AP@0.95 can be explained by this trade-off between recall and precision: conventional training produced low false negative rates, whereas style-transferred datasets produced low false positive rates. Interestingly, style transfer also improved depth prediction, which was an unexpected result.

In this scenario, the models trained on the combined dataset produced the best results on the majority of measures, as in the first scenario. It produced good results in both 2D and 3D detection by finding a compromise between the recall of the original nighttime dataset and the precision of the style-transformed datasets. Apart from AP@0.5, where the model trained on the daylight photos continued to perform better, the model trained on the combined dataset consistently outperformed the other models on most measures.

4.3. Discussion

The results presented above demonstrate that style transfer can partially mitigate the lack of nighttime data in monocular 3D object detection. However, beyond numerical improvements, these findings reveal important insights into the behavior of 3D detectors under domain shifts.

First, the consistent gain in AP@0.95 and the reduction in depth error suggest that style transfer primarily improves low-level luminance and contrast distributions, enabling the model to better estimate object boundaries and relative distances. In contrast, orientation and dimension scores degraded, indicating that global geometric consistency is more sensitive to generative artifacts introduced by style translation. This implies that while appearance-level augmentation increases detection precision, it cannot fully reproduce the geometric realism captured by authentic nighttime data.

Second, the complementarity between real and synthetic data highlights that combining both domains reduces bias: real data enhances recall by exposing true lighting variations, while synthetic data increases precision by regularizing feature learning. This trade-off suggests that mixed-domain training acts as a form of implicit regularization against overfitting to one illumination domain. From a broader perspective, these results have several implications for autonomous driving and dataset design. The ability to generate realistic nighttime imagery without costly manual collection can accelerate the development of perception systems in safety-critical environments. Furthermore, the modular evaluation framework used here could be extended to other perception tasks—such as instance segmentation or motion estimation—and to other datasets like KITTI, Waymo, or nuScenes-lidar, allowing a systematic assessment of generative augmentation in cross-domain settings.

Finally, these findings underline the importance of balancing synthetic and authentic data in safety-critical applications. While generative models provide scalable augmentation, their uncontrolled artifacts may bias training and reduce interpretability. Future work should therefore investigate realism metrics (e.g., FID or user studies), statistical significance testing, and human-in-the-loop validation to ensure reliable deployment in real-world autonomous systems.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the use of style transfer for augmenting nighttime data in monocular 3D object detection. Through a systematic evaluation using the nuScenes dataset, we demonstrated that style transfer can enhance certain components of 3D detection, particularly 2D precision and depth estimation, but remains insufficient as a standalone substitute for real nighttime data.

Quantitatively, models trained exclusively on style-transferred images achieved a 160% improvement in AP@0.95 and an 11% reduction in depth error compared to daytime-only training. When combined with authentic nighttime data, style transfer further reduced the average depth error from 0.041 to 0.021 and improved pedestrian AP@0.95 by 13%. These results confirm that synthetic nighttime images complement, rather than replace, real nighttime samples, reducing false positives and improving the overall robustness of detection under low-light conditions.

However, the experiments also revealed persistent limitations: degradation in orientation and dimension estimation, unstable cyclist detection due to class sparsity, and the absence of significance testing. These findings highlight the complexity of domain adaptation for night scenes and the necessity of maintaining a balance between synthetic and real data to avoid overfitting.

Beyond empirical gains, this work emphasizes the broader implications of using generative models for autonomous driving perception. Style-transferred data can accelerate dataset collection and improve safety-critical model generalization, but it also raises concerns about realism, bias, and potential overreliance on synthetic artifacts.

In future work, we plan to extend this analysis by employing diffusion-based translation models such as img2img-turbo for higher realism, integrating additional object classes, and performing ablation and user studies to quantify perceptual quality. Ultimately, this research contributes to understanding how generative augmentation can improve monocular 3D detection robustness while maintaining ethical and practical considerations for deployment in autonomous systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E., R.K., S.A. and M.O.; Methodology, A.E., F.J., R.K. and S.A.; Validation, A.E., F.J., R.K. and S.A.; Formal analysis, A.E.; Investigation, R.K. and M.O.; Data curation, A.E.; Writing—original draft, A.E., F.J., R.K., S.A. and M.O.; Writing—review & editing, R.K., S.A. and M.O.; Visualization, A.E., F.J., S.A. and M.O.; Supervision, R.K., S.A. and M.O.; Project administration, R.K., S.A. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded and supported by SEGULA Technologies. We would like to thank SEGULA Technologies for their collaboration and for allowing us to conduct this research. We would also like to thank the engineers of the Autonomous Navigation Laboratory (ANL) of IRSEEM for their support. In addition, this work was performed, in part, on computing resources provided by CRIANN (Centre Regional Informatique et d’Applications Numeriques de Normandie, Normandy, France).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study are publicly available at https://www.nuscenes.org/.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mathieu Orzalesi was employed by the company SEGULA Technologies. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lu, Y.; Ma, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Chu, Q.; Yan, J.; Ouyang, W. Geometry uncertainty projection network for monocular 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3111–3121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Objects are different: Flexible monocular 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 3289–3298. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil, G.; Liu, X. M3d-rpn: Monocular 3d region proposal network for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9287–9296. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Urtasun, R. Are we ready for autonomous driving? the kitti vision benchmark suite. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RT, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 3354–3361. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar, H.; Bankiti, V.; Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Liong, V.E.; Xu, Q.; Krishnan, A.; Pan, Y.; Baldan, G.; Beijbom, O. nuScenes: A Multimodal Dataset for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Du, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Tan, X.; Feng, J.; Ding, E.; Wen, S. Monocular 3d object detection via feature domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, C.; Ni, K.; Ding, G. Geometry-guided domain generalization for monocular 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 6467–6476. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, A.; Fang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. Unsupervised domain adaptation for monocular 3d object detection via self-training. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1703.10593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1611.07004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, G.; Park, T.; Narasimhan, S.; Zhu, J.Y. One-Step Image Translation with Text-to-Image Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.12036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalefa, N.; El-Sheimy, N. Monocular Depth Estimation for Night-Time Images. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankadari, M.; Garg, S.; Majumder, A.; Kumar, S.; Behera, A. Unsupervised Monocular Depth Estimation for Night-time Images using Adversarial Domain Feature Adaptation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.01402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Song, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Self-supervised monocular depth estimation for all day images using domain separation. In Proceedings of the CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 12717–12726. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Q. Unsupervised Monocular Depth Estimation in Highly Complex Environments. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2107.13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Fu, H.; Gong, M.; Tao, D. Geometry-aware symmetric domain adaptation for monocular depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9788–9798. [Google Scholar]

- Atapour-Abarghouei, A.; Breckon, T.P. Real-time monocular depth estimation using synthetic data with domain adaptation via image style transfer. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 2800–2810. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Y.; Gong, M.; Fu, H.; Batmanghelich, K.; Zhang, K.; Tao, D. Learning Depth from Monocular Videos Using Synthetic Data: A Temporally-Consistent Domain Adaptation Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.06882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Jiang, Q. Monocular 3d object detection: An extrinsic parameter free approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7556–7566. [Google Scholar]

- Tonioni, A.; Poggi, M.; Mattoccia, S.; Di Stefano, L. Unsupervised domain adaptation for depth prediction from images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 2396–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, X.; Jia, L.; Peng, S. Asymmetric CycleGAN for image-to-image translations with uneven complexities. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, X.; Xuan, Z.; Hu, Z.; Peng, S. PCA-SRGAN: Incremental orthogonal projection discrimination for face super-resolution. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 1891–1899. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).