Abstract

The highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) is a promising fruit species due to its high nutritional value and health benefits. This study, conducted between 2020 and 2024, monitored the phenological and pomological characteristics of 32 different blueberry cultivars grown in the Czech Republic. The evaluation was carried out according to Czech Republic standardized methodologies, BBCH (Biologische Bundesanstalt, Bundessortenamt und Chemische Industrie) and GRIN (Genetic Resources Information Network), and included parameters such as fruit size, flavor, aroma, firmness, color, and soluble solids content (SSC in °Brix). The correlation between individual traits was assessed, along with their phenotypic stability. The results showed that all cultivars exhibited high pomological values, making them suitable for breeding programs. The cultivars ‘Collins’ and ‘Patriot’ received the highest flavor ratings. Firmness, aroma, and color traits were found to be correlated with consumer preferences. The interannual coefficient of variation (CV) obtained for the evaluated blueberry cultivars differed for both pomological and phenological traits, allowing the identification of genotypes with high stability (CV ≤ 10%) and their potential use in targeted breeding programs and industrial production. The ‘Pink Lemonade’ blueberry cultivar, in particular, combines unique color characteristics with a strong aroma. Overall, this study provides valuable insights for future breeding efforts aimed at improving blueberry quality and cultivar adaptability under different cultivation conditions.

1. Introduction

Vaccinium corymbosum L., also known as the northern highbush blueberry, is a perennial shrub species native to North America and a member of the Ericaceae family. It grows optimally in temperate climates with adequate rainfall or irrigation. Compared to most fruit crops, it has unique agroecological requirements, notably a strong need for acidic soils with a pH of 3.8 to 4.5 [1,2,3]. V. corymbosum is a deciduous, multi-stemmed shrub with no principal axis or trunk that typically reaches 1–3.0 m in height. It produces alternately arranged simple leaves and develops corymbose clusters of bell-shaped flowers that range in colors from white to pale pink [4,5,6,7,8].

The agricultural and commercial importance of highbush blueberry lies in the high nutritional quality and biological value of its fruit. It has been scientifically proven that blueberry consumption may help reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, neurodegenerative processes, and certain cancers. The wide range of beneficial effects of blueberries on human health is due to their high content of biologically active compounds, especially polyphenols, which are characterized by strong antioxidant activity [9,10,11,12]. Fresh blueberries are also a source of carotenoids and other vitamins. [13,14,15]. Due to their high nutritional value and beneficial functional properties, blueberries occupy a leading position in the fresh fruit market. Over the past two decades, the global blueberry market has experienced a dramatic increase in production. In contrast, blueberry cultivation in the Czech Republic has been reduced to only a handful of small or family farms, managing plots on the order of tens of hectares. In addition, these farms are not recorded by the Czech Ministry of Agriculture as a separate statistical commodity; therefore, there is no official nationwide production data for blueberries. Nevertheless in recent years, the area under blueberry cultivation in the Czech Republic has been steadily increasing, indicating that this crop may have significant potential in Czech fruit production. Moreover, blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) exhibit substantial genetic and biochemical diversity across cultivars, wild clones, and hybrids [16], which underscores the breeding potential for adaptation to local conditions and market demands. The growing demand for this crop has a significant impact on the export dynamics of the Czech Republic, which have seen a significant increase in shipment volumes since 2020 [17]. In this context, interest is growing in producing both high-quality planting material and varieties that can meet growers’ diverse needs.

Due to blueberry’s high commercial potential, a detailed understanding of its phenological and pomological traits is crucial for the breeding and selection of regionally adapted cultivars. Currently, intensive breeding is being conducted, focusing on various aspects of blueberry production and fruit quality [18,19]. Priority traits include adaptation to abiotic factors, such as phenological adaptability to regional conditions, the need for a shorter chilling period in warmer areas and increased frost tolerance in cooler zones, tolerance to elevated soil pH, and resistance to spring and autumn frosts, as well as to ultraviolet radiation [20]. At the same time, considerable attention is given to production-related traits, including high yield, fruit size, and suitability for mechanized harvesting [21], as well as taste [22], fruit color [18,23], appearance, and texture [24,25]. Consequently, breeders are increasingly focused on identifying genotypes that exhibit desirable agronomic traits, making them suitable for use as material in modern breeding programs. In this context, preserving and maintaining diverse agricultural genetic resources worldwide have become clear priorities. These collections safeguard valuable genetic diversity and provide a foundation for selecting cultivars adapted to evolving environmental conditions and market demands. Therefore, the main objective of our study was to evaluate the pomological and phenological traits of 32 different highbush blueberry cultivars, and their suitability for breeding and cultivation under the environmental conditions encountered in the Czech Republic. Results from this work will also help identify the most promising cultivars for commercial cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted between 2020 and 2024 at the Genetic Resources Department of the Research and Breeding Institute of Pomology Holovousy Ltd. (RBIP). The highbush blueberry cultivars evaluated were planted in the genebank of the RBIP, which was established in 1989 as part of the fruit germplasm collections in Holovousy, a village in eastern Bohemia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Blueberry germplasm collection (field cultivation).

This locality (coordinates: 50°22′31″ N 15°34′39″ E) is situated in the Jičín District of the Hradec Králové Region in the Czech Republic. It has an average annual temperature of 8.4 °C and an average precipitation of 663.5 mm [26]. The field was irrigated, and crop management followed standard plantation management practices. Annual sanitary pruning was performed in March and April to develop and maintain the proper size and shape of the bushes, and dead, broken, or diseased branches were pruned back to live wood. A mulch layer composed of shredded bark and coniferous wood was applied under the Vaccinium corymbosum bushes to maintain soil moisture and suppress weed growth. The center row between the plants was kept by mowing the grass regularly to prevent erosion and to facilitate the movement of agricultural machinery for agrotechnical interventions and plantation management.

2.1. Plant Material

The experiment included 32 cultivars of Vaccinium corymbosum L. (highbush blueberry). Three to six bushes were planted for each cultivar at an altitude of 320 m.

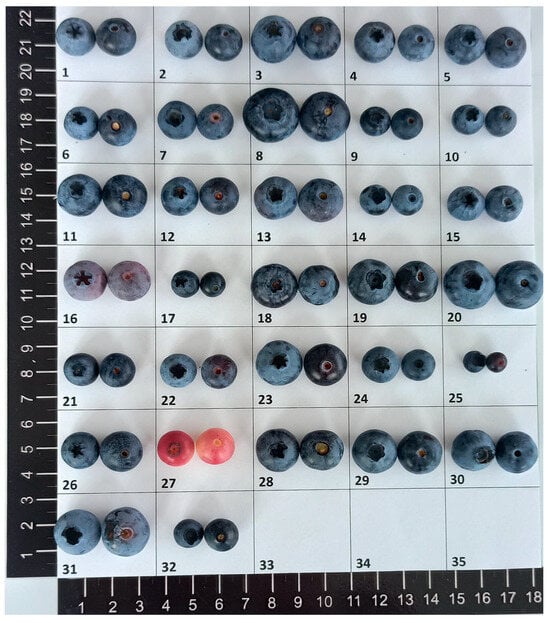

Fruits from a collection of 32 different blueberry cultivars were harvested at maturity and evaluated for pomological traits (Figure 2). ‘Bluecrop’ was used as a commercial standard.

Figure 2.

Appearance of the blueberry cultivars evaluated. 1—Bluecrop (standard commercial cultivar; C), 2—Berkeley, 3—Blu Jay, 4—Blue Gold, 5—Blue Ray, 6—Bluetta, 7—Bluhaven, 8—Brigitta, 9—Burlinton, 10—Collins, 11—Coville, 12—Croatan, 13—Darow, 14—Duke, 15—Early Blue, 16—Elliott, 17—Gila, 18—Goldtranbe, 19—Herbert, 20—Chandler, 21—Iranka, 22—Jersey, 23—Nelson, 24—Northland, 25—November, 26—Patriot, 27—Pink Lemonade, 28—Rancocas, 29—Spartan, 30—Sunrise, 31—Toro, and 32—Weymouth.

The phenological and pomological traits were assessed using the nine-point classification scale established for blueberries in the GRIN Czech database, which is the national documentation system for plant genetic resources in the Czech Republic. This system, adapted from the globally recognized GRIN-Global platform developed in cooperation with the USDA Agricultural Research Service, provides standardized and detailed characterization data for particular crops including blueberries.

2.2. Evaluation of the Pomological Traits

For the purpose of evaluation, 100 representative fruits were selected to reflect the average morphological and qualitative characteristics of the given cultivar. For pomological traits, the evaluation was carried out on a representative sample of 10 fruits. Descriptive analysis and sensory properties were subjectively assessed by 4 trained experts specialized in fruit quality evaluation, with prior experience in pomological sensory analysis, following the recommended procedures of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). The pomological evaluation of the fruit was assessed using rating scales as follows: fruit size (1—very small, up to 90 g/100 fruits; 3—small, 90–119 g; 5—medium, 120–159 g; 7—large, 160–199 g; and 9—very large, over 200 g); length-to-width ratio (3—width greater than length; 5—width equal to length; and 7—width less than length); surface glossiness (3—dull/waxy; 5—moderately glossy; and 7—highly glossy); and skin color (1—grayish-blue; and 2—dark blue to black). When the color was not specified in the classifier, we used a verbal description (‘Pink Lemonade’). Firmness (3—low; 5—medium; and 7—high); acidity (3—low; 5—medium; and 7—high); aromatic intensity (1—imperceptible; 3—faint; 5—medium; 7—aromatic; and 9—very aromatic); and flavor quality (1—unsatisfactory; 3—acceptable; 5—good; 7—very good; and 9—excellent) were also assessed. Soluble solids content (SSC) was expressed in °Brix using digital hand refractometer (Bellingham + Stanley Ltd., model Brix 54, Tunbridge Wells, Kent UK).

2.3. Evaluation of the Phenological Traits

The phenological stages were identified according to the BBCH scale for blueberries. The BBCH scales represent a unified coding system for describing phenologically similar growth stages in mono- and dicotyledonous plants. The beginning of flowering was established when 30% of the flowers had opened (BBCH 63). The end of flowering was established when 70% of the flower had fallen. The onset of ripening was established when 30% of the fruits had reached maturity (BBCH 893). Flower and fruit set were evaluated on a scale of 1–9 (1—absent, 3—weak, 5—intermediate, 7—high, and 9—very high). The start and end of flowering, as well as the beginning of ripening, were recorded as the number of days from the start of the calendar year. The weight of 100 fruits was determined by weighing one hundred randomly selected, fully ripe berries from each cultivar. The total weight (in grams) was measured using an analytical balance (RADWAG, model PS 4500.R2, Radom, Poland) with an accuracy of ±0.01 g.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis of the results was performed using Minitab 19 statistical software (Minitab LLC (1829 Pine Hall Rd State College, PA, 16801-3008, USA), 2019), including the calculation of standard deviations.

All values were averaged to obtain means for individual characteristics, and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated to describe the variance of the evaluated values. SDs were computed using the following formula:

where takes on each value in the set, is the statistical mean of the set of values, and n is the number of values. The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated using the following formula:

The standard error of the mean (SE) was calculated using the formula:

The evaluated cultivars were categorized into three groups according to the degree of variability, based on generally accepted criteria for the interpretation of the coefficient of variation:

Low-to-negligible variability—The CV does not exceed 10%, the population is considered homogeneous, and the mean values derived from it are representative.

Moderate variability—The CV does not exceed 30%, the trait is considered to show average variability, and the resulting indicators are of moderate reliability.

High variability—The CV exceeds 30%, the population is considered heterogeneous, and the mean values are not regarded as representative.

Pearson’s correlations were used to calculate the correlation coefficients between different combinations of pomological traits. The resulting coefficients were interpreted using the following scale:

- Up to 0.20—very weak correlation;

- From 0.21 to 0.50—weak correlation;

- From 0.51 to 0.70—moderate correlation;

- From 0.71 to 0.90—strong correlation;

- Above 0.91—very strong correlation.

A statistical analysis of the experimental data was performed using Minitab 19 software (Minitab LLC, 2019). Prior to conducting a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), the data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Tukey’s post hoc test was used to identify significant differences between means at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pomological Traits

Overall, blueberry cultivars showed high quality across multiple pomological traits (Table 1). Specifically, the cultivars ‘Collins’ and ‘Patriot’ achieved the highest average flavor ratings, consistently scoring a maximum of 9 points across all years. These two cultivars also demonstrated minimal year-to-year variability in flavor expression, with coefficients of variation below 10% (Table 2). This indicates a high degree of trait stability, positioning both cultivars as strong candidates for use as parental genotypes in breeding programs aimed at improving sensory quality.

Table 1.

Pomological evaluation of blueberry fruits (2020–2024).

Table 2.

Coefficient of variation for traits in blueberry cultivars (%).

A broader group of cultivars, including ‘Brigitta’, ‘Blue Gold’, ‘Blue Ray’, ‘Berkeley’, ‘Elliott’, ‘Goldtraube’, ‘November’, ‘Pink Lemonade’, and ‘Spartan’, achieved average flavor scores ranging from 7 to 8 points, corresponding to the “very good” category. Within this group, the coefficients of variation for flavor ranged from low (≤10%) to moderate (10–30%), suggesting consistent trait expression across years and environmental conditions. These cultivars may also be considered valuable donors of favorable sensory attributes in targeted breeding efforts exceeding ‘Bluecrop’, used in our study as a commercial standard.

All tested cultivars met high standards for pomological traits, including fruit size, shape, firmness, color, and flavor (Table 1). However, the importance of individual traits may differ across global markets, because consumer preferences for fruit attributes, such as sweetness, firmness, and flavor intensity, vary significantly between regions [20,27]. Nevertheless, traits such as flavor and sugar content have consistently emerged as primary drivers of consumer choice for fresh-market blueberries [18,22,28,29]. The high, stable performance of selected cultivars with respect to these traits underscores their strategic value in breeding programs aimed at developing new, high-quality genotypes suited to regional cultivation and market demands. The cultivar ‘Chandler’ achieved the highest average fruit weight (339.9 g per 100 berries), differing significantly from the commercial standard ‘Bluecrop’, whereas ‘November’ recorded the lowest value among the examined cultivars. Traditionally, breeding efforts have predominantly prioritized yield improvement over enhancing organoleptic qualities [3,22].

While the present study primarily focused on the comprehensive evaluation of phenological and pomological traits across blueberry cultivars, the complex interplay between phenological phases and fruit flavor characteristics warrants further investigation. Although our data provide a robust overview of flavor variability, establishing direct relationships between particular developmental stages of the plant (e.g., flowering or ripening periods) and specific flavor characteristics remains difficult because these traits are shaped by numerous environmental and genetic factors. Previous research has likewise shown that the timing of these developmental phases—together with ecological and post-harvest conditions—plays a key role in modulating flavor formation [30]. This underscores the need for more targeted studies to unravel the nuanced connections between developmental stages and sensory qualities.

Nevertheless, there has been a significant increase in interest regarding the optimization of fruit flavor profiles [31]. Concurrently, there has been a growing trend of integrating sensory evaluations using trained tasting panels with multi-omics methodologies to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of flavor determinants [32]. Recent investigations in blueberries and tomatoes have revealed that up to 50% of variation in consumer preferences can be attributed to sugar and acid levels [31]. Therefore, in addition to sensory evaluation, it is advisable to consider the chemical composition of the fruits, particularly the sugar:acid ratio. Although the ‘Berkeley’ cultivar had the lowest soluble solids content (11.3%) and ‘Bluecrop’ had the highest (16.6%), statistical analysis did not reveal significant differences between these two cultivars. Based on these results, any of the tested cultivars may serve as a potential donor for the soluble solids content trait. However, cultivars with a coefficient of variation not exceeding 10% for SSC should be prioritized, as this indicates trait stability and its heritability [32].

Another important organoleptic trait that significantly influences consumer cultivar selection is aroma intensity. Results from the correlation analysis indicate a strong relationship between aroma and flavor attributes, as evidenced by a high correlation coefficient (0.72). However, despite the fact that acidity scores ranged from 3 to 5 points, no positive correlation was found between this trait and SSC, aroma, or flavor attributes. It is well established that consumers generally prefer cultivars with moderate acidity levels because excessive sweetness can lead to negative sensory perceptions among tasters and consumers [18,31,33].

Among the evaluated cultivars, ‘Bluetta’, ‘Bluegold’, ‘Blueray’, ‘Duke’, and ‘Toro’ exhibited superior fruit firmness, while the control cultivar ‘Bluecrop’ showed a comparatively lower value of 5.4 points. These cultivars can therefore be considered promising donors of fruit firmness for use in advanced breeding programs. Significant variability in textural properties among cultivars was observed, which is consistent with previous findings associating these differences with cell wall structure and the biochemical composition of fruit tissues [34,35,36,37]. Fruit firmness is widely recognized as a key quality attribute that influences consumer preference, post-harvest performance, and suitability for large-scale production. Consequently, it is one of the most critical morphological traits assessed during the breeding process [25,31,34,36]. Genotypes with excessively soft fruit are typically excluded during the initial selection phase due to their limited commercial viability [32,33]. The increasing adoption of mechanized harvesting and extended supply chains further accentuates the importance of selecting cultivars that can maintain structural integrity during handling and transportation [15,23,35,37,38,39].

‘Croatan’, ‘Coville’, ‘Herbert’, ‘Iranka’, ‘Jersey’, ‘November’, ‘Rancocas’, and ‘Weymouth’ were identified as promising donors of fruit with a dark blue surface color, a trait linked to higher levels of phenolic compounds, particularly anthocyanins. These dark-colored berries are presumed to have enhanced antioxidant capacity, which supports previous findings linking pigmentation intensity to bioactive compound content [18,23].

Fruit appearance is a critical factor in consumer acceptance [24,25,40], with color being one of the most influential morphological characteristics affecting perceived quality. Although darker surface color has traditionally been preferred by consumers due to its association with nutritional value and visual appeal, recent market trends indicate a rising interest in cultivars bearing lighter-colored berries, particularly in the fresh fruit sector [39]. These emerging preferences reflect a diversification of consumer demand and suggest the potential for targeted breeding strategies that incorporate both dark and light fruit color profiles to meet the needs of different market segments.

It is worth noting that many blueberry cultivars exhibit a waxy bloom on the surface of the fruit, which can influence the visual perception of berry color. However, the results of the correlation analysis indicate a moderately weak association between the presence of a waxy coating and perceived color (r = 0.5). This suggests that, within the scope of our study, the waxy coating appears to play only a partial role in overall color evaluation; however, we acknowledge that in some cultivars and under certain conditions, it could be regarded as an indicator of freshness.

In addition to their high nutritional value, certain blueberry cultivars also warrant attention for their ornamental potential in lawn and landscape design [41]. In particular, the cultivar ‘Pink Lemonade’ cultivar combines excellent flavor characteristics with visually striking pink berries, enhancing its ornamental appeal and supporting its use in landscape design.

3.2. Phenological Traits

Climate change has received significant attention in recent years and is widely discussed for its potential implications for berry fruits [42]. In our study, we therefore highlight commonly reported concerns—such as the vulnerability of early-flowering cultivars to late spring frosts and the influence of elevated summer temperatures on fruit firmness. High temperatures lead to excessive softening of the berries, which hinders or even prevents their transportability and long-term storage (e.g., ‘O’Neil’, ‘Snowchaser’, ‘Misty’, ‘Lobos’, and ‘Han’ cultivars). The present study revealed that the flowering period among the evaluated cultivars ranged from 102 to 133 days (Table 3), indicating the presence of a broad spectrum of potential donors with diverse phenological traits. Based on the onset of flowering, the cultivars were provisionally classified into three phenological categories: early flowering (102–111 days), midseason (112–122 days), and late flowering (125–133 days). For example, ‘Early Blue’ and ‘Bluhaven’ were categorized as early and midseason flowering types, respectively, while most other cultivars fell within the late-flowering group. In regions with a high risk of spring frost, breeding programs should prioritize developing late-flowering cultivars. Breeding programs focused on developing late-flowering cultivars are increasingly relevant in this context, as this trait reduces the risk of spring frost damage [43,44,45,46,47]. Conversely, in areas where early fruit ripening is a priority, selection should consider the duration and dynamics of the ripening period in addition to flowering time.

Table 3.

Phenological evaluation of blueberry cultivars, 2020–2024.

According to the literature, the cultivar ‘Duke’ is characterized by a tendency toward rapid deacclimation [20], which may limit its effectiveness as a donor of phenological traits in breeding efforts.

Though they are also substantially influenced by abiotic factors and genotype-by-environment interactions, phenological traits such as the onset of flowering and fruit ripening, exhibit a high degree of heritability in blueberry genotypes [48,49].

The length of the ripening period is an equally important criterion in cultivar selection for commercial planting and breeding program design. Blueberries ripen gradually, enabling a prolonged supply of fresh produce to the market. Among the evaluated cultivars, ‘Early Blue’ had the shortest ripening period (25 days), while ‘Northland’ had the longest (43 days).

Short-ripening cultivars include ‘Early Blue’ (25 days), ‘Duke’ (27 days), ‘Goldtraube’ (27 days), ‘Jersey’ (27 days), ‘Pink Lemonade’ (27 days), ‘Burlington’ (27 days), ‘Collins’ (28 days), and ‘Elliott’ (28 days). Those with extended ripening periods include ‘Berkeley’ (37 days), ‘Blu Jay’ (37 days), ‘Darow’ (39 days), ‘Patriot’ (40 days), ‘Northland’ (43 days), ‘Coville’ (42 days), and ‘Nelson’ (38 days). The remaining cultivars had intermediate ripening durations of approximately 30–35 days.

Using cultivars with an extended ripening period is economically advantageous because it allows for staggered harvest times and ensures continuous supply of fresh produce. In contrast, cultivars with a short ripening period are optimal for single or concentrated harvests, which is particularly beneficial for mechanized picking. Cultivars with intermediate ripening times offer a versatile solution and are most commonly used in industrial-scale production.

3.3. Cultivar Description

Description of the Evaluated Cultivars

Bluecrop (C)

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firmer than average, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is stronger than average. The flavor is very good. The ripening period is extended, lasting approximately 5 weeks.

Bluetta

The fruits are small, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is very good. The ripening period is extended and lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Brigitta

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy and grayish dark-blue in coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is above average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is very good. The ripening period is extended, lasting approximately 5 weeks.

Bluhaven

The fruits are very large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull and grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is very good. The ripening period is extended and lasts approximately 4.5 weeks.

Blu Jay

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width nearly equal to the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firmer than average, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is average. The flavor is above average. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Blue Gold

The fruits are very large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4.5 weeks.

Blue Ray

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4.5–5 weeks.

Berkeley

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is moderately firm, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Burlington

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Croatan

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4.5 weeks.

Coville

The fruits are medium-sized, and the width exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is weak. The flavor is good. The ripening period lasts approximately 6 weeks.

Collins

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is excellent. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Darow

The fruits are very large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is better than good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5.5 weeks.

Duke

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is above average. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Early Blue

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firmer than average, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is good. The ripening period lasts approximately 3.5 weeks.

Elliott

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is less firm than average, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Gila

The fruits are small, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firmer than average, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is weaker than average. The flavor is good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Goldtraube

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is moderately firm, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Herbert

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is average. The aroma is above average. The flavor is good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Chandler

The fruits are very large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Iranka

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is moderately glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Jersey

The fruits are small, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is above average. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Nelson

Fruits are very large, width exceeds length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. Flesh is of medium firmness, and acidity is below average. Aroma is medium. Flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5.5 weeks.

Northland

Fruits are small, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 6 weeks.

November

The fruits are very small, with a width that nearly equals the length. The surface is moderately glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is low. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Patriot

Th fruits are very large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is low. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is excellent. The ripening period lasts approximately 6 weeks.

Pink Lemonade

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width that nearly equals the length. The surface is moderately glossy with a pink coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is low. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is excellent. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Rancocas

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is moderately glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Spartan

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is low. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Sunrise

The fruits are large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is pronounced. The flavor is very good. The ripening period lasts approximately 4 weeks.

Toro

The fruits are very large, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is dull with a grayish-blue coloration. The flesh is very firm, and the acidity is average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is average. The ripening period lasts approximately 5 weeks.

Weymouth

The fruits are medium-sized, with a width that exceeds the length. The surface is slightly glossy with a dark-blue coloration. The flesh is of medium firmness, and the acidity is below average. The aroma is medium. The flavor is good. The ripening period lasts approximately 6 weeks.

4. Conclusions

Through comprehensive multi-year investigations, a set of elite cultivars was identified that combine superior pomological, especially organoleptic, properties with advantageous phenological characteristics. This makes them suitable both for both commercial cultivation and as genetic donors of key agronomic traits. Notably, ‘Collins’ and ‘Patriot’ exhibited the highest flavor quality with consistent trait stability, positioning them as prime candidates for enhancing sensory attributes in breeding efforts. Cultivars such as ‘Bluetta’, ‘Bluegold’, ‘Blueray’, ‘Duke’, and ‘Toro’ were distinguished by their fruit firmness, a critical attribute underpinning suitability for mechanized harvesting and postharvest handling. Regarding fruit coloration ‘Croatan’, ‘Coville’, ‘Herbert’, ‘Iranka’, ‘Jersey’, ‘November’, ‘Rancocas’, and ‘Weymouth’ emerged as valuable sources of dark pigmentation for breeding objectives. The cultivar ‘Elliott’ proved to be highly stable in terms of fruit weight compared to the other cultivars evaluated. In the phenological evaluation of traits such as the onset of flowering, the end of flowering, and flower set, the cultivars ‘Early Blue’ and ‘Sunrise’ exhibited moderate variability, while all other tested cultivars showed low variability for these traits. The cultivar ‘Bluecrop’ (c) was characterized by high stability, particularly in phenological parameters such as the end of ripening and the length of the ripening period, which represents significant potential for breeding aimed at regulating fruit ripening time and for the cultivation of blueberries in industrial plantations with the possibility of mechanized harvesting. Delineating cultivars with diverse flowering and ripening phenologies across climatic zones offers strategic opportunities to optimize harvesting logistics and prolong fresh fruit availability in the market. These findings collectively provide a robust foundation for targeted breeding programs that integrate multiple economically important traits, thereby supporting the development of improved cultivars that meet production efficiency and consumer preference standards. Future studies integrating meteorological records with detailed pomological data and quantitative quality studies are also planned to investigate environmental influences related to global climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P., M.M. and J.S.; methodology, L.P. and M.M.; validation, J.S. and B.K.; formal analysis, L.P. and M.M.; investigation, L.P. and M.M.; resources, L.P. and M.M.; data curation, J.S. and B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, L.P., M.M. and J.S.; visualization, L.P. and M.M.; supervision, J.S. and B.K.; project administration, J.S. and B.K.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Programme on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources and Agrobiodiversity, No.: MZE-62216/2022-13113/6.2.4 and grant No. RO1525.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank František Švec for English proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Liliia Pavliuk, Michaela Marklová, Boris Krška and Jiři Sedlak were employed by the company Research and Breeding Institute of Pomology Holovousy Ltd. All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Messiga, A.J.; Haak, D.; Dorais, M. Blueberry Yield and Soil Properties Response to Long-Term Fertigation and Broadcast Nitrogen. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 230, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, W.; Lyu, L.; Li, W. Growth and Physiological Characteristics of Four Blueberry Cultivars under Different High Soil pH Treatments. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 197, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Shao, T.; Long, X.; Rengel, Z. Effects of Soil Properties and Microbiome on Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) Growth. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.; Lyrene, P.; Finn, C.; Vorsa, N.; Lobos, G. Blueberries and Cranberries. In Temperate Fruit Crop Breeding; Narendra Publishing: Delhi, India, 2008; pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, M.J.; Retamales, J.B. Cane Productivity and Fruit Quality in Highbush Blueberry Are Affected by Cane Diameter and Location within the Canopy. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2017, 82, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamales, J.B.; Hancock, J.F. Crop Production Science in Horticulture Series; CABI: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, M.J.; Retamales, J.B.; Hanson, E.J.; Araya, C.M. Relationship between Cane Age and Vegetative and Reproductive Traits of Northern Highbush Blueberry in Chile and United States. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 310, 111775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, S.; Araya-Alman, M.; Moggia, C.; Lobos, G.; Calderon, F.; Espinoza, S. Plant Morphology and Fruit Quality Traits Affecting Yield and Post-Harvest Behavior of Two Highbush Blueberry Cultivars in Central Chile. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.; Adams, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, R.; Sand, D.; Scheuller, H.; Heber, D. Blackberry, Black Raspberry, Blueberry, Cranberry, Red Raspberry, and Strawberry Extracts Inhibit Growth and Stimulate Apoptosis of Human Cancer Cells In Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 54, 9329–9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconeasa, Z.; Leopold, L.; Rugină, D.; Ayvaz, H.; Socaciu, C. Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Properties of Anthocyanin Rich Extracts from Blueberry and Blackcurrant Juice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 2352–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent Research on the Health Benefits of Blueberries and Their Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Goyali, J. In Vitro Propagation and Variation of Antioxidant Properties in Micropropagated Vaccinium Berry Plants—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwińczuk, W. Micropropagation of Vaccinium Sp. by In Vitro Axillary Shoot Proliferation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 11013, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchovski, C.; Biasi, L. In Vitro Establishment of ‘Delite’ Rabbiteye Blueberry Microshoots. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappai, F.; Garcia, A.; Cullen, R.; Davis, M.; Munoz del Valle, P. Advancements in Low-Chill Blueberry Vaccinium corymbosum L. Tissue Culture Practices. Plants 2020, 9, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.S.; Debnath, S.C. Genetic Diversity of Blueberry Genotypes Estimated by Antioxidant Properties and Molecular Markers. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Němcova, V.; Buchtova, I. Situace a Výhledová Zpráva Ovoce 2024; Ministry of Agriculture: Praha, Czech Republic, 2024.

- Olmstead, J.; Colquhoun, T.; Levin, L.; Clark, D.; Moskowitz, H. Consumer-Assisted Selection of Blueberry Fruit Quality Traits. HortScience 2014, 49, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, S.; Zurawicz, E. The High-Bush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) Breeding Programme in Poland. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1017, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, G.; Hancock, J. Breeding Blueberries for a Changing Global Environment: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strik, B. Blueberry Production and Research Trends in North America. Acta Hortic. 2006, 715, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieman, D.; Zhu, G.; Resende, M.; Lin, T.; Nguyen, C.; Bies, D.; Rambla, J.; Schneider-Beltran, K.S.; Taylor, M.; Zhang, B.; et al. A Chemical Genetic Roadmap to Improved Tomato Flavor. Science 2017, 355, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftner, R.; Polashock, J.; Ehlenfeldt, M.; Vinyard, B. Instrumental and Sensory Quality Characteristics of Blueberry Fruit from Twelve Cultivars. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 49, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, M.F.; Grace, M.; Xiong, J.; Kay, C.; Bassil, N.; Hummer, K.; Ferruzzi, M.; Lila, M.; Iorizzo, M. Diversity in Metabolites and Fruit Quality Traits in Blueberry Enables Ploidy and Species Differentiation and Establishes a Strategy for Future Genetic Studies. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthart, M.; Gezan, S.; Carvalho, M.; Schwieterman, M.; Colquhoun, T.; Bartoshuk, L.; Sims, C.; Clark, D.; Olmstead, J. Identifying Breeding Priorities for Blueberry Flavor Using Biochemical, Sensory, and Genotype by Environment Analyses. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prskavec, K.; Sedlak, J.; Paprštein, F.; Mrkvica, L.; Metelka, L. Padesát Pět Let Meteorologických Pozorování v Holovousích (1955–2009); Výzkumný a Šlechtitelský Ústav Ovocnářský Holovousy s.r.o.: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, J.; Olmstead, J.W. Breeding for the Ideal Fresh Blueberry; Growing Produce: Willoughby, OH, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farneti, B.; Khomenko, I.; Grisenti, M.; Ajelli, M.; Betta, E.; Algarra Alarcón, A.; Cappellin, L.; Aprea, E.; Gasperi, F.; Biasioli, F.; et al. Exploring Blueberry Aroma Complexity by Chromatographic and Direct-Injection Spectrometric Techniques. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sater, H. Understanding Blueberry Aroma Origin, Inheritance, and Its Sensory Perception by Consumers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clingeleffer, P.R.; Davis, H.P. Assessment of Phenology, Growth Characteristics and Berry Composition in a Hot Australian Climate to Identify Wine Cultivars Adapted to Climate Change. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 28, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, V.; Ferrão, L.F.V.; Tieman, D.M.; Bliznyuk, N.; Sims, C.; Klee, H.J.; Munoz, P.; Resende, M.F.R. Metabolomic Selection for Enhanced Fruit Flavor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115865119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, L.; Dhakal, R.; Dias, R.; Tieman, D.; Whitaker, V.; Gore, M.; Messina, C.; Resende, M. Machine Learning Applications to Improve Flavor and Nutritional Content of Horticultural Crops through Breeding and Genetics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2023, 83, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrão, L.; Rampazo Amadeu, R.; Benevenuto, J.; Oliveira, I.; Munoz del Valle, P. Genomic Selection in an Outcrossing Autotetraploid Fruit Crop: Lessons from Blueberry Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 676326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappai, F.; Benevenuto, J.; Ferrão, L.; Munoz del Valle, P. Molecular and Genetic Bases of Fruit Firmness Variation in Blueberry—A Review. Agronomy 2018, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giongo, L.; Poncetta, P.; Loretti, P.; Costa, F. Texture Profiling of Blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) during Fruit Development, Ripening and Storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 76, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.; Giongo, L.; Cappai, F.; Kerckhoffs, H.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Hutchins, D.; East, A. Blueberry Firmness—A Review of the Textural and Mechanical Properties Used in Quality Evaluations. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 192, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, V.; Giacalone, G.; Rolle, L. Mechanical Behaviour and Quality Traits of Highbush Blueberry during Postharvest Storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Hongdi, L.; Kang, L.; Jinman, G.; Gai, Y.; Yunlong, D.; Sun, H.; Li, Y. Identification and Expression Analysis of MATE Genes Involved in Flavonoid Transport in Blueberry Plants. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Pico, J.; Gerbrandt, E.M.; Dossett, M.; Castellarin, S.D. Comprehensive Anthocyanin and Flavonol Profiling and Fruit Surface Color of 20 Blueberry Genotypes during Postharvest Storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 199, 112274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, K.; Stafne, E.; DeVetter, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Takeda, F.; Williamson, J.; Yang, W.; Cline, W.; Beaudry, R.; et al. Blueberry Producers’ Attitudes toward Harvest Mechanization for Fresh Market. HortTechnology 2018, 28, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollert, F. Blueberries for the Home Garden—The Lubera Edibles Assortment. Available online: https://gaertnerbuch.luberaedibles.com/en/blueberries-for-the-home-garden-8211-the-lubera-edibles-assortment-p67 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Tasnim, R.; Drummond, F.; Zhang, Y.-J. Climate Change Patterns of Wild Blueberry Fields in Downeast, Maine over the Past 40 Years. Water 2021, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, L.J.; Ogden, E.L.; Ehlenfeldt, M.K.; Vinyard, B. Cold Hardiness, Deacclimation Kinetics, and Bud Development among 12 Diverse Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Genotypes under Field Conditions. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2005, 130, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, J.M. Chilling Regimes Affect Bud Break in Tithlue’ Rabbiteye Blueberry. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1976, 101, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.F.; Nelson, J.W.; Bittenbender, H.C.; Callow, P.W.; Cameron, J.S.; Krebs, S.L.; Pritts, M.P.; Schumann, C.M. Variation among Highbush Blueberry Cultivars in Susceptibility to Spring Frost. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1987, 112, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, K.; Neuendorff, E.; Nimr, G.; Clark, J.; Fernandez, G. Cold Injury of Southern Blueberries as a Function of Germplasm and Season of Flower Bud Development. HortScience A Publ. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1991, 26, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Pliszka, K. Comparison of Spring Frost Tolerance among Different Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) Cultivars. Acta Hortic. 2003, 626, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P. Effects of Year and Genotype on Flowering and Ripening Dates in Rabbiteye Blueberry. HortScience 1985, 20, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C.; Hancock, J.; Mackey, T.; Serce, S. Genotype × Environment Interactions in Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium sp. L.) Families Grown in Michigan and Oregon. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2003, 128, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).