Abstract

Much focus is being dedicated to the development of innovative technologies for producing biodegradable polymers from plant biomass. It is proposed that annual and perennial herbaceous plants, such as miscanthus, be used as promising sources of cellulose. The component composition of miscanthus allows us to consider it as a raw material for obtaining cellulose. This paper proposes methods for cooking miscanthus lignocellulose raw materials, which allow sulfate cellulose to be obtained with a high yield (up to 52%). In the process of obtaining chemical–thermomechanical pulp, the product yield is 71%. The possibility of replacing unbleached sulfate pulp with a semi-finished product from miscanthus for paper production is considered. For all types of raw materials obtained, acceptable paper-forming properties are observed. The best strength and deformation properties are obtained for sulfate cellulose. The addition of this cellulose to the composition of waste paper fluting significantly increases the sheet density, elasticity, and energy capacity without losing tensile strength. Using miscanthus raw materials along with waste paper of grade MS 5B makes it possible to make a composite product. The resulting products have optimal mechanical properties for creating the middle layer of corrugated cardboard. Miscanthus cellulose can be considered a promising raw material for enhancing waste paper fluting. Altering the system composition utilizing miscanthus and waste paper enables a broad modification of the mechanical and optical qualities of the resultant paper. The recommended concentration of miscanthus fraction in waste paper fluting is 30%.

1. Introduction

The European packaging industry is actively abandoning single-use plastic products in favor of reusable and easily recyclable materials, which is enshrined in the new Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR), where one of the key goals is to prevent packaging waste and expand reuse and refill systems [1]. By 2030, all plastic waste should be recyclable, which will require a major upgrade of the infrastructure. In Russia, more than 26 billion plastic bags are utilized annually [2]. Paper bags are a natural alternative, but large-scale logging will be required to produce 26 billion bags per year. At present, in global practice, fibers for paper bags are obtained from the wood of fast-growing plantations (eucalyptus and pine), where trees reach commercial maturity on average in 6–13 years [3]. Of course, if we dramatically expand the manufacture of paper bags by cutting down virgin forests without restoration, this will lead to the loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, and more CO2 emissions [4,5,6].

As a result, there is an increasing interest in finding alternative sources of plant raw materials for the production of packaging that are not inferior to wood and do not pose additional environmental risks. Annual crops with high biomass yields are being investigated as an alternative to traditional wood raw materials in regions with limited forest resources, including sugar cane (bagasse), cereal straw (rice, wheat), corn and sorghum stalks, industrial hemp, and flax [7,8,9]. Annual plants produce a reasonably high yield of cellulose (up to 60–70% of the mass of the raw material) and require more moderate alkaline or sulfite cooking modes due to the low amount of contaminants, such as lignin [10].

Another of the most promising types of renewable raw materials for the production of paper and cardboard is miscanthus of various varieties [11]. Miscanthus, or fan grass (Latin: Miscánthus), is a genus of perennial herbaceous plants of the family Poaceae, used in landscape design. Miscanthus cultivation requires minimal agricultural inputs, grows well on marginal lands, and promotes carbon sequestration in the soil [12]. This frost-resistant cereal, starting from the second year of the plantation’s life and up to 20 years, annually yields up to 17 tons of dry biomass per hectare while remaining resistant to diseases, and does not require abundant fertilization. According to a study [13], during kraft cooking, miscanthus stems produce fibers with mechanical properties similar to cellulose from deciduous trees such as birch, aspen, and poplar. The yield of cellulose reaches 86% of the mass of the raw material, which is significantly higher than wood sources (up to 55%).

In addition, miscanthus provides access to a wide range of bioproducts and highly crystalline bacterial cellulose [14,15,16,17,18].

Several technological and economic challenges emerge when converting miscanthus into cellulose. Firstly, the high silica and ash content in the stem biomass leads to a sharp increase in the viscosity of black liquor and the formation of deposits in evaporators, waste heat boilers, and causticizers, which complicates the recycling of lime liquor and requires additional costs for equipment maintenance [19]. Secondly, the anatomical heterogeneity of miscanthus—a combination of parenchymatous cells, vessels, and nodes together with fibers—necessitates preliminary dry mechanical processing (crushing, classification of small particles), otherwise fines and shives impair pulp drainage and reduce the productivity of paper machines [20]. In kraft pulping, the yield of cellulose from miscanthus, although comparable to some wood species, is significantly lower than the yield of mechanical methods of processing lignocellulosic raw materials (80–90%), which requires large volumes of raw materials and increases the costs of transportation and storage [21].

Combined methods of processing lignocellulosic raw materials have become quite firmly established in the pulp and paper industry and have proven their effectiveness in solving the problems described above [22]. Combined methods are mainly used in wood processing, but now similar schemes are being increasingly introduced for working with agricultural waste. This is why the adaptation of combined methods to agricultural residues—especially to miscanthus—seems particularly promising. The optimization of pulping modes allow for the “soft” removal of lignin from miscanthus, preserving the length and strength of the fibers. In [19], it was shown that small changes in the alkaline charge, temperature, and cooking time of kraft pulp significantly affect the degree of lignin removal, the brightness of the resulting product, and the preservation of the fiber length. Paper [23] presents a combined method for obtaining cellulose from miscanthus Kamis (Miscanthus Anderss, group: technical, variety code: 8355069) harvested in 2013. The essence of this method lies in treating the raw material with a dilute solution of sodium hydroxide, and then with a nitric acid solution. Cellulose isolated in this way is characterized by the following quality indicators: ash content—0.34%, mass fraction of acid-insoluble lignin—1.45%, mass fraction of pentosans—9.4%, mass fraction of α-cellulose—89.4%, and degree of polymerization—990. The obtained cellulose is characterized by a high yield at the level of 42% in terms of raw materials or 88% in terms of native cellulose. A combined approach including the alkaline pretreatment of stems with NaOH and subsequent hydrodynamic cavitation is described in [24]. As a result, the total lignin removal reached 41.5%, and the α-cellulose content in the resulting pulp increased by 13.87% compared to the original material. At the same time, the average fiber length remained virtually unchanged (600–650 µm). The authors note that this scheme allows for a significant reduction in the volume of alkali (up to 30% compared to conventional kraft pulping), a reduction in energy costs for mechanical grinding, and the production of fibers with strength characteristics comparable to those of softwood.

Currently, the cooking of miscanthus is conducted mainly in laboratory and pilot test conditions, and only a few groups plan to scale these processes up to the industrial level [25]. In order to bring the technology to wide commercial use, detailed studies of alkaline, kraft, and semi-chemical pulping modes are needed; the goal is to gently remove lignin without damaging cellulose fibers [26]. Simultaneously, research is being conducted to develop biocomposites based on miscanthus fibers and biopolymer matrices (PLA, PHBV, etc.); such materials already have a high elastic modulus and improved barrier properties, but the fiber–polymer interface should be refined for stable additive distribution and reliable adhesion in packing [27].

All of this makes miscanthus a unique source of multicomponent raw materials for green chemistry and materials science. However, the technology for processing this cereal has not yet been brought to widespread industrial use. It is necessary to optimize the modes for the gentle removal of lignin and preservation of high-quality cellulose, as well as to develop materials in which miscanthus fibers will be combined with biopolymers, providing reliable barrier and mechanical properties in packaging. We assume that the choice of optimal conditions for cooking and processing lignocellulosic raw materials from miscanthus will allow high-quality raw materials to be obtained for the production of biodegradable packaging materials.

Hence, the main goal of the work was to develop approaches to obtaining cellulose-containing products based on miscanthus with a high yield of cellulose, and to evaluate the paper-forming properties and mechanical properties of the obtained products.

2. Materials and Methods

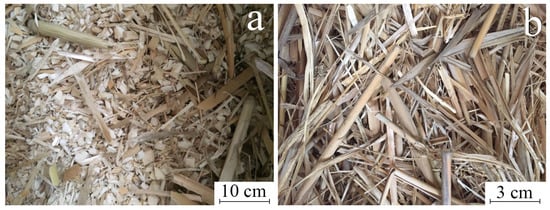

For the research, a sample of Kaluga miscanthus, variety KAMIS (Kaluga, Russia), was used in two versions: untreated stems and chopped stems (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Photos of miscanthus: cuttings (a) and stems (b).

2.1. Laboratory Brews

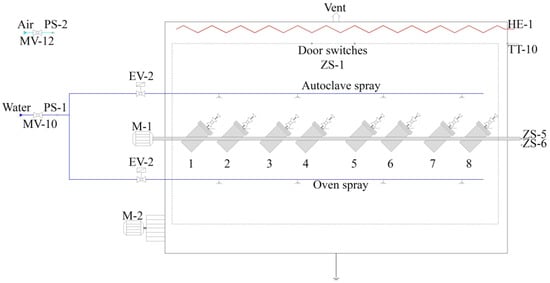

In laboratory conditions, a series of miscanthus cooking experiments using white liquor were simulated and carried out. A sample of miscanthus in the form of stems (pencils) was used as the raw material; immediately before cooking, the miscanthus stems were crushed to a segment length of 2.0–2.5 cm and soaked in hot water for 12 h. Cooking was carried out in an automated autoclave system CAS 420 (Figure 2), designed for modeling the sulfite and sulfate processes of the delignification of cellulose-containing raw materials in laboratory conditions.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the cooking unit.

The miscanthus weight for one experiment was 40 g (a.d.) of raw material, and the cooking hydromodule varied during the process from 3 to 5 units. The cooked mass of high-yield pulp (HYP) after cooking was subjected to hot grinding (T = 85 °C) in a laboratory CGA (centrifugal grinding apparatus—Jokro Refining mill (model P40120) RTA, Frank-PTI GmbH, Birkenau, Germany) in specialized glasses for 5 min until a fibrous state was reached. Cellulose of normal yield after cooking did not require hot grinding.

The washing of the welded samples to separate the spent lye was carried out in a laboratory tank with a perforated bottom (decanter). The upper decanter had a mesh with holes of 4 mm in diameter, and the lower decanter had a mesh of 40 mm.

The cooking conditions are presented in Table 1. To model the cooking process, kraft white liquor with the following characteristics was used: total alkali—114 g/L (as Na2O); active alkali—93.8 g/L (as Na2O); sulfidity—26.45%.

Table 1.

Process mode for cooking pulp from miscanthus.

2.2. Cellulose Analysis

The determination of the moisture content of the raw materials and cellulose was carried out in accordance with GOST 16932-93 (ISO 638-78) [28].

The yield of cellulose (B) was determined using the gravimetric method and calculated using the following formula:

where M1, M2—the mass of chips before cooking and pulp after cooking, and K1, K2—the dryness coefficients of chips before cooking and pulp after cooking.

The determination of the Kappa number (degree of delignification) was carried out in accordance with GOST 10070-74 [29].

2.3. Grinding and Preparation of Laboratory Samples

The samples were ground in a laboratory CGA mill at a mass concentration of 6%. The grinding process was controlled by determining the degree of mass grinding. The samples were prepared for testing. The degree of mass grinding was determined according to GOST 14363.4-89 [30] and the mass concentration according to GOST R 50068-92 [31].

The laboratory samples were manufactured using a sheet-casting machine from the Rapid-Köthen system (PTI, Laakirchen, Austria). The mass of the castings per 1 m2 corresponded to 125 g. The pressing of the castings was carried out using the machine’s press roller. Drying was carried out at a temperature of 105 ± 5 °C in the sheet-casting machine. Before testing, the samples were conditioned according to GOST 13523-78 [6,32] under conditions of constant air humidity equal to 50 ± 2 and a constant temperature of 23 ± 1 °C.

2.4. Mechanical Characteristics

The quality parameters of the laboratory samples were determined using standard methods: sample thickness was measured in accordance with GOST 27015-86 [33] using an SE 250 digital micrometer (AB Lorentzen & Wettre, Kista, Sweden); tensile strength and elongation at break in accordance with GOST 13525.1-79 [34] on a Testsystema 101 tester (MTS Systems Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA); bursting strength in accordance with GOST 13525.8-86 [35] on an L&W Bursting Strength Tester (CODE 180; L&W, Stockholm, Kista, Sweden); flat crush resistance (SMT) in accordance with GOST 20682-75 [36]; edgewise crush resistance (SST) in accordance with GOST 28686-90 [37]; and ring crush (RCT) in accordance with GOST 10711-97 [38].

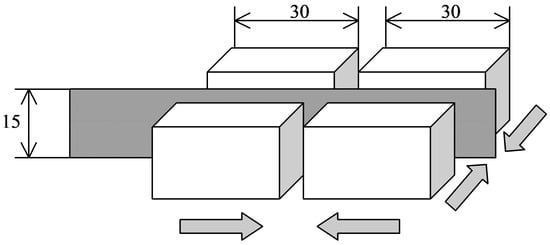

Compression strength was determined using the SCT method in accordance with GOST R ISO 9895-2013 [39] using an L&W Compressive Strength Tester (STFI, Code 152; L&W, Stockholm, Kista, Sweden). The measurement principle for SCT is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the determination of compressive strength using the SCT method (GOST R ISO 9895-2013. Paper and Cardboard. Determination of compressive strength. Short-distance test method between clamps) [39].

During the test, a linerboard specimen is placed between two clamps with a free test span of 0.7 mm. The test speed is 3 ± 1 mm/min. As the clamps move toward each other, the specimen shortens and the load in the strip increases.

All experiments were performed in triplicate and data was expressed as mean.

2.5. Microscopy

The morphology of the samples was assessed by optical microscopy using an Axio Imager microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany); the sample was placed between two cover glasses in a wet state.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Obtaining High-Yield Pulp from Miscanthus

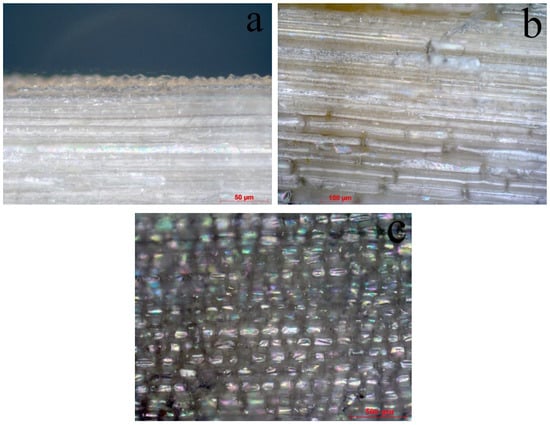

Figure 4 shows a microscopic analysis of the stems of the presented miscanthus sample. The ash content of the sample was determined to be 4.2%.

Figure 4.

Micrographs of the stem of miscanthus: (a) stem bark, (b) stem, (c) soft core.

Along the edge of the stem there is a thin yellowish bark consisting of living cells of the bark. This is followed by a narrow strip of dense white mechanical tissue of libyrizoforms, in which oblong thick-walled fibers run parallel to each other (Figure 4a). Next is the second layer of libyrizoforms (Figure 4b), which gives the stem rigidity. In the center there is soft parenchyma—loose spongy tissue with large intercellular spaces, responsible for storing nutrients and ensuring gas exchange inside the stem (Figure 4c).

The process of obtaining high-yield pulp (HYP) from miscanthus was simulated with the selection of the final cooking temperature and alkali consumption in accordance with the best technologies.

The raw material for obtaining sulfate HYP was a sample of miscanthus in the form of stems. Samples were crushed into segment lengths of 2.0–2.5 cm immediately before cooking and soaked in hot water for 12 h. Table 2 shows the results of cooking sulfate HYP from miscanthus in three different modes: the first (50 min at 160 °C), the second (50 min at 150 °C), and the third (30 min at 150 °C).

Table 2.

Results of cooking HYP from miscanthus.

For cooking mode No. 1 with a low alkali consumption (4%), the maximum yield of 54% of cellulose was obtained, but with a high Kappa number of 78 and a relatively low pH of 8.0. With an increase in alkali, the yield decreased to 45.9%, Kappa fell to 48.4, and pH rose to 8.7. In mode No. 2, the yields were more modest (from 42.7% to 38.0%). The Kappa number here quickly decreased from 77.9 to 14.8, and the pH changed from 8.3 to 10.5. In mode No. 3, with average alkali consumption (7–10%), the yields remained at a higher level (from 52.0% to 40.7%), the Kappa number decreased from 70.1 to 26.9, and the pH varied from 10.0 to 12.0. Thus, an increase in alkali consumption in all modes led to a decrease in the cellulose yield, but at the same time ensured deeper depolymerization of lignin (a decrease in the Kappa number) and an increase in the alkalinity of the sample.

A feature of miscanthus processing due to its structure is the increased hydromodulus (HM) of the cooking process; therefore, for the development of the HM process modes, it was adopted equal to 5:1. As can be seen from the presented data (Table 2), obtaining HYP from miscanthus with an acceptable lye pH after cooking is possible using a mode with a cooking duration of 30 min at a temperature of 150 °C. This mode is the most balanced and preferable for further scaling of the process of obtaining HYP from miscanthus.

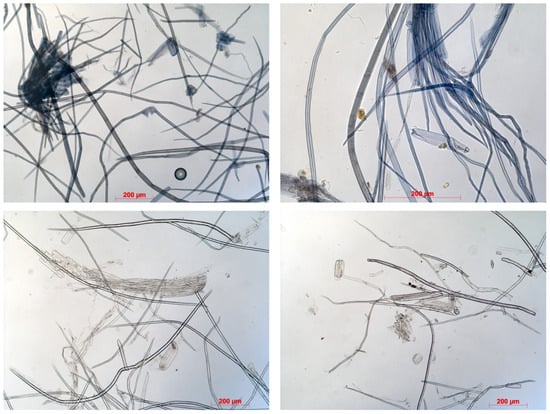

After cooking, the mixture of miscanthus and lye was ground in a CGA mill for 5 min. The degree of grinding after fiberization was 14–15 °SR, and after secondary grinding was 20–22 °SR. Figure 5 shows microphotographs of sulfate HYP fibers from miscanthus.

Figure 5.

Micrographs of sulfate HYP from miscanthus.

From the photographs it is evident that the fibers are uneven in length and width, contain a large number of vessels, and a large number of fiber bundles are observed. Along with the cellulose phase, the samples contain resin particles.

In production facilities for obtaining corrugated cardboard, cellulose (or semi-chemical agglomerate) is usually mixed with waste paper in the middle layer (fluting) masses [40]. In modern container paper mills, the proportion of secondary fibers is selected depending on the required properties of the resulting paper: for light and medium grades of fluting (typically C- and E-fluting), the waste paper content can reach 30–40%, and in less important (quality) products, the proportion of waste paper reaches 50–70% [41]. The use of waste paper allows for a reduction in the cost of the resulting products, reduces energy costs for cooking and washing, and reduces the environmental footprint of production. In products where high tensile strength and rigidity are critical, the proportion of waste paper is usually limited to 20–30% [42].

Samples of laboratory fluting were made from a composition of MS 5B waste paper and sulfate HYP from miscanthus. MS 5B waste paper in accordance with GOST 10700-97 [43] is waste from the production and consumption of corrugated cardboard, paper, and cardboard. Currently, in Russia, 95–96% of this type of waste paper is collected and sent for recycling. The fibers of this type of waste paper raw material are the strongest and most rigid. Table 3 clearly shows how the dimensions and behavior of the fibers change when adding ever larger shares of waste paper to miscanthus cellulose.

Table 3.

Structural and dimensional characteristics of the fibers of sulfate HYP from miscanthus and waste paper grade MS 5B.

The table shows how the average length and thickness of the composition fibers change depending on the proportion of miscanthus cellulose. If the fibers of miscanthus cellulose are, on average, slightly less than a millimeter (0.889 mm) and quite thin (24.1 μm), then for 100% wastepaper raw materials, these values increase to 1.28 mm in length and 28.1 μm in width, respectively. It is curious that the form factor remains approximately at the same level of about 88%, and only in pure waste paper does it drop slightly to ~85.5%; that is, the fibers still retain an elongated, ribbon-like shape. At the same time, the fiber roughness, which affects the adhesion between the layers of paper, first increases sharply from 117 to 165, and then fluctuates slightly, returning to 158 for 100% wastepaper raw materials. If we talk about elasticity and fragility, the average angle of fiber fracture with a small proportion of waste paper (25–75%) drops slightly to ~51°, which indicates flexibility, and in a sample made from pure waste paper it sharply increases to 57°; that is, the fibers become more brittle. The number of fracture sites per millimeter and per fiber also reaches its maximum either in the average composition or in pure waste paper—this means that waste paper fibers more often produce microcracks under loads. Finally, with the increase in waste paper, the “vascular” part noticeably decreases (the number of large pores in the sample drops from ~28,000 to ~4000) and the share of very short dust-like fibers decreases (from 10.2% to 6.2%), which generally indicates a more uniform and durable structure of the finished paper pulp. Adding waste paper to the fibrous composition of the sample allows the average fiber sizes in the paper web to be changed, making them longer and thicker, rougher, and, in some cases, more brittle, while reducing the amount of “small particles” and large pores, which can have a positive effect on the homogeneity and durability of the finished fluting.

The effect of a step-by-step increase in the proportion of waste paper in the paper composition on the strength and elasticity of fluting samples is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Quality indicators of samples of fluting based on a composition of sulfate HYP from miscanthus and waste paper grade MS 5B.

The obtained data indicate that the sulfate HYP from miscanthus is close to semi-celluloses from deciduous trees in a number of deformation parameters. The tensile strength characteristics (breaking load ~103 N, breaking length ~5750 m) and relative elongation (~2.5%) are comparable to what is described for non-wood semi-finished products: despite the lower strength, the high elongation reserve gives these papers an energy capacity close to beech or birch kraft pulp [21].

When using miscanthus cellulose, the density and thickness of fluting are about 0.606 g/cm3 and 197 µm, respectively; then, with the addition of 20% waste paper to the mixture system, the density slightly increases to 0.617 g/cm3, and the thickness remains virtually unchanged. A further increase in the proportion of waste paper in the composition of laboratory materials does not lead to significant changes in their quality characteristics. On the other hand, the mechanical strength of the laboratory fluting samples decreases as waste paper is added to the composition. The breaking load and breaking length decrease from 103 N and 5750 m for pure miscanthus to 81 N and 4500 m for a sample made from 100% waste paper, indicating a decrease in tensile strength. The stiffness indices of the samples—the resistance to the planar compression of a corrugated sample (SMT) and the breaking force under ring compression (RCT)—also steadily decrease, as does the resistance to compression at a short distance between clamps (SCT) and the conditional rupture pressure (P). It is interesting that the energy absorbed before rupture (TEA) initially increases slightly with the addition of 20% waste paper (up to 116.6 J/m2), but then drops noticeably, and in the sample made of pure waste paper, it is at the level of 78 J/m2. At the same time, the elastic modulus demonstrates the greatest drop (up to 257 MPa) with an increase in the proportion of waste paper—up to 80%—and is partially restored for the sample obtained from 100% waste paper, which is probably due to the peculiarities of the component composition of the waste paper itself. A small addition of waste paper of up to 20% to the miscanthus-based system allows the energy capacity of fluting to increase without losing density, but with an increase in the proportion of waste paper above 50%, the mechanical properties of the laboratory fluting samples deteriorate noticeably.

The presented data show that a small proportion of waste paper (approximately one fifth of the total mass of fibers) allows the density and energy capacity of corrugating paper to be increased without losing its integrity and elasticity. However, as soon as the proportions of waste paper and miscanthus become equal or when the first phase dominates, the tensile strength and rigidity indicators begin to decrease significantly, and the ability to absorb energy before failure decreases by one and a half to two times. The elastic modulus in samples with a waste paper proportion of 80% decreases especially noticeably, which indicates structural changes, probably caused by the heterogeneity formed in the system. Thus, from a practical point of view, the most interesting are compositions with a waste paper proportion not exceeding 20%, when high mechanical characteristics are still preserved and miscanthus cellulose savings are achieved. With larger proportions of recycled paper, the fluting properties are already too deteriorated to guarantee the requirements for the strength and durability of the finished product.

3.2. Development of Modes for Obtaining Chemical–Thermomechanical Mass

Modeling the process of obtaining chemical–thermomechanical mass (CTMM) allows one to estimate in advance how different cooking parameters—alkali consumption, process temperature, duration—will affect the key indicators of quality and cost-effectiveness of the technology without wasting resources on multiple full-scale experiments.

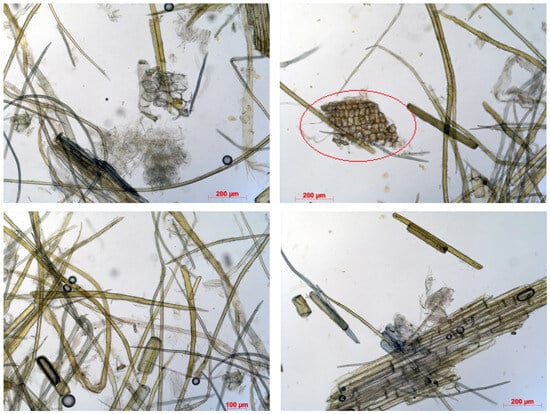

To obtain CTMM from miscanthus, an alkali treatment was used—3% white kraft liquor. In this case, approximately 71% of the fiber mass was extracted from the stems. The Kappa number was 88 and the spent alkaline solution had a pH of about 11.0. After steaming, the mixture of miscanthus and liquor was ground in a mill for 15 min. The degree of grinding of the mass after fibering was 14–15 °SR. The mass was characterized by high shivery, which was removed after processing the mass on a Sommervile apparatus (Rycobel Group, Deerlijk, Belgium, Sommervile SM-21 fiber classifier). Figure 6 shows micrographs of CTMM from miscanthus.

Figure 6.

Micrographs of CTMM fibers from miscanthus.

The microphotographs clearly show the heterogeneity of the mass, which is typical for mechanical masses, which is confirmed by the results of the Fibertester (Table 5). Undissolved parenchyma and bundles of unseparated fibers are clearly visible.

Table 5.

Structural and dimensional characteristics of the fibers of the pulp based on the composition of CTMM from miscanthus and waste paper grade MS 5B.

To assess the possibility of using CTMM in the composition of containerboard components, samples were made with different ratios of MS 5B waste paper and miscanthus CTMM with a grinding degree of 30 °SR. The results of the analysis of the structural and dimensional characteristics of the mass with different fiber compositions are presented in Table 5.

The combination of CTMM from miscanthus and waste paper allows the length, coarseness, and flexibility of the fibers to be adjusted: a small proportion of secondary material makes them longer and slightly rougher without losing elasticity, and pure waste paper produces the longest but also the most fragile and smooth fibers.

Quality indicators of fluting samples based on a composition of CTMM from miscanthus and waste paper grade MS 5B are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Quality indicators of fluting samples based on the composition of CTMM from miscanthus and waste paper grade MS 5B.

Miscanthus CTMM forms the softest and loosest sheet of paper for corrugating. Its density is minimal (≈0.408 g/cm3), the breaking length is about 1870 m, and the bursting values of R ≈ 70 kPa, RCT ≈ 93 N, and SCT ≈ 1.72 kN/m are also the lowest in the series. This indicates that the thermomechanical pulp from miscanthus itself is inferior in strength and rigidity to papers based on wood or waste paper cellulose.

The addition of CTMM to waste paper has a dramatic effect on deformation parameters; at 25% replacement of waste paper mass with thermomechanical mass, the destructive stress index of the sample already drops almost without compensation for the increase in elongation, and at 50% and higher proportions, the deformation at break is significantly reduced (and even inferior to pure waste paper fluting). This indicates that the thermomechanical mass from miscanthus worsens the mechanical characteristics of waste paper fluting.

Miscanthus CTMM under the current cooking conditions has low density and mechanical strength, which makes it unsuitable in its pure form for use in the composition of corrugated paper. The introduction of CTMM into waste paper fluting is only permissible at a moderate (up to 30%) content of miscanthus CTMM, at which the strength indicators remain at a level acceptable for corrugated packaging.

3.3. Technology of Obtaining Neutral Sulfite Semi-Cellulose (NSSC)

Next, the process of obtaining NSSC from miscanthus was simulated with the selection of the final cooking temperature and alkali consumption. The cooking modes are presented in Table 1, and the cooking results are in Table 7. Neutral sulfite liquor was used to simulate the cooking process. A feature of processing this type of raw material is the increased hydromodulus of the cooking process; therefore, a 7:1 ratio was adopted for working out the GM process modes.

Table 7.

Results of cooking NSSC from miscanthus.

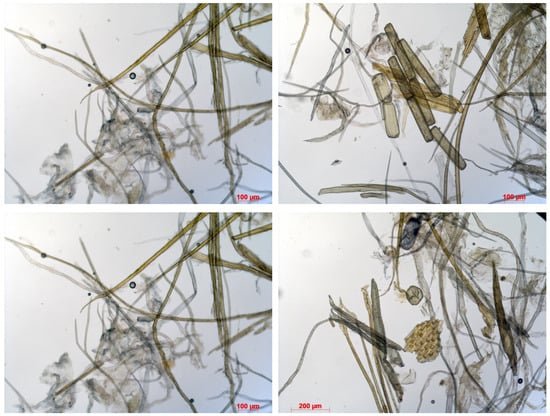

Table 7 clearly shows how the yield of the semi-finished product changes with increasing alkali consumption in the neutral sulfite cooking of miscanthus. With a relatively gentle mode with 20% alkali consumption, it is possible to obtain almost 55% of the cellulose mass; at the same time, the Kappa number of the resulting semi-finished product decreases, which indicates an increase in dissolved lignin in the spent liquor. When 25% of alkali is added, the yield drops to ≈49%, but the Kappa number decreases to ≈54, and the resulting semi-finished product is noticeably lighter. Figure 7 shows micrographs of the NSSC obtained from miscanthus.

Figure 7.

Micrographs of NSSC from miscanthus.

After cooking, the mixture of miscanthus and red liquor was ground in a CGA mill for 5 min. The degree of grinding was 14–15 °SR, and after secondary grinding was 20–22 °SR. Samples were made in the composition of waste paper grade MS 5B and NSSC from miscanthus, and the physicomechanical properties were determined in samples weighing 125 g/m2. The test results for the samples are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Quality indicators of fluting samples based on the composition of NSSC from miscanthus and waste paper grade MS 5B.

A look at Table 8 allows to draw several clear conclusions. Firstly, pure neutral sulfite semi-cellulose from miscanthus produces the thinnest fluting (density 0.568 g/cm3, thickness 206 µm), and its mechanical characteristics are the lowest: a breaking force of about 65 N, a breaking length ≈ 3680 m, and an energy absorption before breaking of only 37 J/m2. With the addition of waste paper, the density, strength, and energy absorption capacity begin to increase. Even 20% of secondary fibers increases the P to 171 kPa and TEA to 43 J/m2, and increases the breaking strength and length. At 50–80% waste paper, we already see a combination of good rigidity (SCT 2.9 kN/m, RCT 150–170 N) with high energy capacity (42–53 J/m2) and decent elongation (1.4–1.7%).

It is interesting that, at 100% waste paper, fluting becomes the densest and most durable (P 320 kPa, breaking load 82 N, TEA 78 J/m2), but the rigidity of the elastic structure (modulus E and tensile rigidity) drops slightly compared to the “golden mean” of 50–80%.

Thus, fluting/corrugating paper from pure miscanthus is too soft, and from 100% waste paper it is too rigid and less elastic. The best balance of strength, elasticity, and energy capacity is achieved with a moderate dose of recycled paper (approximately 50–80%), which allows the flexible adjustment of the properties of the middle layer of corrugated cardboard for specific technological tasks.

4. Conclusions

In the course of the work, a whole range of technologies were developed for obtaining cellulose containing products from miscanthus with a high yield and different degrees of delignification: high-yield pulp—about 52%, neutral sulfite semi-cellulose (NSSC)—55%, chemical–thermomechanical mass (CTMM)—71%, and bleached CTMM (BCTMM)—36%. All of the obtained samples demonstrate an average level of paper-forming properties, while it was HYP that showed the optimal mechanical and deformation indicators, turning out to be the strongest and most elastic. The addition of this cellulose to waste paper fluting significantly increases the sheet density, elasticity, and energy capacity without losing tensile strength.

Neutral sulfite semi-cellulose from miscanthus, due to its balanced combination of strength, rigidity, and elasticity, is capable of meeting the regulatory requirements for the middle layer of corrugated cardboard when mixed with MS 5B waste paper. Chemical thermomechanical pulp, although giving a very high fiber yield, is too “soft” and brittle in itself, but can be used in waste paper fluting in a proportion of up to 30% without the noticeable deterioration of mechanical characteristics. Bleached CTMM shows good potential for bleaching while maintaining sufficient strength, which makes it promising when it is necessary to obtain products with lighter tones.

Thus, sulfate HYP acts as a universal enhancer of waste paper fluting, NSSC provides a reliable compromise between rigidity and elasticity, CTMM provides the maximum yield adjusted for low strength, and BCTMM provides the ability to bleach thermomechanical pulp. The choice of a specific semi-finished product and its percentage content in the formulation of corrugating paper will allow the flexible adjustment of the properties of the middle layer of corrugated cardboard depending on the requirements for strength, elasticity, and the visual design of the finished packaging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., N.S., S.M. and I.M.; methodology, Y.S., N.S., A.P., D.K. and A.S. (Amanzhan Saginayev); software, G.S.; validation, Y.S., S.M., G.M. and I.M.; formal analysis, Y.S., A.P., A.S. (Ayauzhan Shakhmanova), I.M. and A.S. (Amanzhan Saginayev); investigation, A.P., S.M., I.S.L., E.P., I.K. and A.S. (Ayauzhan Shakhmanova); resources, S.M. and A.S. (Amanzhan Saginayev); data curation, Y.S., N.S., S.M., I.M. and F.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S., N.S., S.M. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.S., E.P., I.M. and G.M.; visualization, I.K., F.K., I.S.L. and G.S.; supervision, Y.S. and I.M.; project administration, Y.S., N.S. and I.M.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Preparation of the manuscript text was carried out within the State Program of TIPS RAS and was financially supported by the Moscow Polytechnic University within the framework of the P.L. Kapitsa grant program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/packaging-waste_en?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Available online: https://sdiopr.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/doc/Ms_JERR_85826.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Resquin, F.; Fariña, I.; Rachid-Casnati, C.; Rava, A.; Doldán, J.; Hirigoyen, A.; Inderkum, F.; Alen, S.; Olmos, V.M.; Carrasco-Letelier, L. Impact of rotation length of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. on wood production, kraft pulping, and forest value. iForest—Biogeosciences For. 2022, 15, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.; Lee, T.M.; Koh, L.P.; Brook, B.W.; Gardner, T.A.; Barlow, J.; Peres, C.A.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Laurance, W.F.; Lovejoy, T.E.; et al. Primary forests are irreplaceable for sustaining tropical biodiversity. Nature 2011, 478, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambilova, G.K.; Bukanova, A.S.; Kalauova, A.S.; Kalimanova, D.Z.; Abilkhairov, A.I.; Makarov, I.S.; Vinogradov, M.I.; Makarov, G.I.; Yakimov, S.A.; Koksharov, A.V.; et al. An Experimental Study on the Solubility of Betulin in the Complex Solvent Ethanol-DMSO. Processes 2024, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskakov, S.A.; Baskakova, Y.V.; Kabachkov, E.N.; Kichigina, G.A.; Kushch, P.P.; Kiryukhin, D.P.; Krasnikova, S.S.; Badamshina, E.R.; Vasil’ev, S.G.; Soldatenkov, T.A.; et al. Cellulose from Annual Plants and Its Use for the Production of the Films Hydrophobized with Tetrafluoroethylene Telomers. Molecules 2022, 27, 6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.S.; Golova, L.K.; Vinogradov, M.I.; Egorov, Y.E.; Kulichikhin, V.G.; Mikhailov, Y.M. New Hydrated Cellulose Fiber Based on Flax Cellulose. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2022, 91, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.S.; Budaeva, V.V.; Gismatulina, Y.A.; Kashcheyeva, E.I.; Zolotukhin, V.N.; Gorbatova, P.A.; Sakovich, G.V.; Vinogradov, M.I.; Palchikova, E.E.; Levin, I.S.; et al. Preparation of Lyocell Fibers from Solutions of Miscanthus Cellulose. Polymers 2024, 16, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Rehman, A.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.R.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, Z. Utilization of non-wood fibers as raw materials for pulp and paper production in Pakistan: A review. Pak. J. For. 2024, 74, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletto, P.; Mongardini, F.; Barberi, B.; Sannibale, M.; Brizzi, M.; Pignatelli, V. Papermaking pulps from the fibrous fraction of Miscanthus × Giganteus. Ind. Crops Prod. 2000, 11, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavyrkina, N.A.; Budaeva, V.V.; Skiba, E.A.; Gismatulina, Y.A.; Sakovich, G.V. Review of Current Prospects for Using Miscanthus-Based Polymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, D.; Surma-Ślusarska, B. Miscanthus × giganteus stalks as a potential non-wood raw material for the pulp and paper industry. Influence of pulping and beating conditions on the fibre and paper properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 141, 111744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-C.; Kuan, W.-C. Miscanthus as cellulosic biomass for bioethanol production. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 10, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Choi, G.-W.; Kim, Y.; Koo, B.-C. Bioethanol production by Miscanthus as a lignocellulosic biomass: Focus on high efficiency conversion to glucose and ethanol. BioResources 2011, 6, 1939–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A.; Belotti, M.; Rossetti, I. Bioethylene Production: From Reaction Kinetics to Plant Design. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13333–13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anestis, P.; Vasiliki, K. Utilization of aromatic plants residual biomass after distillation mixed with wood in solid biofuels production. Renew. Energy 2025, 248, 123198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, T.; Kim, H.S.; Shin, W.H.; Oh, J.-M.; Koo, S.-M.; Yu, B.J.; Yoo, H.Y.; Park, C. Enhanced Production of Bacterial Cellulose from Miscanthus as Sustainable Feedstock through Statistical Optimization of Culture Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, D.; Dybka-Stępień, K.; Surma-Ślusarska, B. Processing of Miscanthus × giganteus stalks into various soda and kraft pulps. Part I: Chemical composition, types of cells and pulping effects. Cellulose 2018, 25, 6731–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachimiak, K.; Wojech, R.; Wójciak, A. Comparison of miscanthus giganteus and birch wood nssc pulping part i: The effects of technological conditions on certain pulp properties. Wood Res. 2019, 64, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Danielewicz, D.; Surma-Ślusarska, B.; Żurek, G.; Martyniak, D.; Kmiotek, M.; Dybka, K. Selected grass plants as biomass fuels and raw materials for papermaking, Part II. Pulp and paper properties. BioResources 2015, 10, 8552–8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartler, N. Chemi-Thermo-Mechanical Pulping. In Pulp and Paper Chemistry and Technology, 3rd ed.; Fapet Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 1996; Volume 4 (Mechanical Pulping). [Google Scholar]

- Gismatulina, Y.A. Analysis of the quality of cellulose obtained by a combined method from miscanthus harvested in 2013. Fundam. Res. 2014, 6, 1195–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalagkas, D.; Börcsök, Z.; Pásztory, Z.; Gogate, P.; Csóka, L. Assessment of the papermaking potential of processed Miscanthus × giganteus stalks using alkaline pre-treatment and hydrodynamic cavitation for delignification. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, F.; Sánchez, J.L.; Arauzo, J.; Fuertes, R.; Gonzalo, A. Semichemical pulping of Miscanthus giganteus. Effect of pulping conditions on some pulp and paper properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3933–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixta, H. (Ed.) Handbook of Pulp; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; p. 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Reimer, C.; Wang, T.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of the Biocomposites of Miscanthus Biocarbon and Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV). Polymers 2020, 12, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 16932-93; Pulps. Determination of Dry Matter Content. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/18959/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 10070-74; Pulp and Semi-Pulp. Method for Determinating Kappa Number. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/17164/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 14363.4-89; Pulp. Preparation of Samples for Physical and Mechanical Tests. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/11288/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST R 50068-92; Pulps. Determination of Stock Concentration (Rapid Method). Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/19035/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 13523-78; Fibre Semi-Finished Products, Paper and Board. Method for Conditioning of Samples. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/14918/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 27015-86; Paper and Board. Methods for Determining Thickness, Density and Specific Volume. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2024. Available online: https://progost.com/gost/8593 (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 13525.1-79; Fibre Semimanufactures, Paper and Board. Tensile Strength and Elongation Tests. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/5617/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 13525.8-86; Fibre Intermediate Products, Paper and Board. Method for Determination of Resistance to Bursting. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/5667/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 20682-75; Paper for Corrugation. Method for Determining the Resistance of Corrugated Paper to Flat Compression (Concoro Medium Test). Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2024. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/16456/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 28686-90; Corrugating Paper. Method for Determination of Corrugating Resistance to Edge Compression. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/4969/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST 10711-97; Paper and Board. Method for Determination of Breaking Force by Ring Compression (RCT). Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/6333/?ysclid=mgtdlpbruz212831294 (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- GOST R ISO 9895-2013; Paper and Cardboard. Determination of Compressive Strength. Short-Distance Test Method Between Clamps. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2015. Available online: https://protect.gost.ru/document1.aspx?control=31&baseC=6&page=5&month=5&year=2014&search=&id=185308 (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

- Sheikhi, P.; Asadpour, G.; Zabihzadeh, S.M.; Amoee, N. An optimum mixture of virgin bagasse pulp and recycled pulp (OCC) for manufacturing fluting paper. BioResources 2013, 8, 5871–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.fibrebox.org/corrugated-is-recyclable?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sarkhosh Rahmani, F.; Talaeipoor, M. Study on production of fluting paper from wheat straw soda–AQ pulp and OCC pulp blends. Iran. J. Wood Pap. Sci. Res. 2011, 26, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 10700-97; Waste Paper and Board. Specifications. Russian State Standard: Moscow, Russia, 2023. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/6178/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Russian)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).