Abstract

The gas equation of state (EOS) serves as a critical tool for analyzing the thermal effects within the hydrogen storage tank during refueling processes. It quantifies the dynamic relationships among pressure, temperature and volume, playing a vital role in numerical simulations of hydrogen refueling, the development of refueling protocols, and ensuring refueling safety. This study first establishes a lumped-parameter thermodynamic model for the hydrogen refueling process, which combines a zero-dimensional gas model with a one-dimensional tank wall model (0D1D). The model’s accuracy was validated against experimental data and will be used in combination with different EOSs to simulate hydrogen temperature and pressure. Subsequently, parameter values are derived for the van der Waals EOS and its modified forms—Redlich–Kwong, Soave, and Peng–Robinson. The accuracy of the modified forms is evaluated using the Joule–Thomson inversion curve. A polynomial EOS is formulated, and its parameters are numerically determined. Finally, the hydrogen temperatures and pressures calculated using the van der Waals EOS, Redlich–Kwong EOS, polynomial EOS, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database are compared. Within the initial and boundary conditions set in this study, the results indicate that among the modified forms for van der Waals EOS, the Redlich–Kwong EOS exhibits higher accuracy than the Soave and Peng–Robinson EOSs. Using the NIST-calculated hydrogen pressure as a benchmark, the relative error is 0.30% for the polynomial EOS, 1.83% for the Redlich–Kwong EOS, and 17.90% for the van der Waals EOS. Thus, the polynomial EOS exhibits higher accuracy, followed by the Redlich–Kwong EOS, while the van der Waals EOS demonstrates lower accuracy. This research provides a theoretical basis for selecting an appropriate EOS in numerical simulations of hydrogen refueling processes.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global energy sector’s accelerated transition towards low-carbon and clean energy, hydrogen energy has emerged as a highly promising key component of the future energy system. Its significant advantages, including diverse sources, clean and pollution-free combustion products, and high energy density, have led to broad application prospects in transportation, power generation, industrial processes, and other fields, offering a new direction for addressing energy and environmental challenges [1].

Hydrogen storage technology is a core segment of the hydrogen industry chain, and its development level directly impacts the large-scale application and promotion of hydrogen energy. Current mainstream hydrogen storage methods include high-pressure gas storage, cryogenic liquid storage, and metal hydride storage. Among these, high-pressure gaseous hydrogen storage has become the most widely adopted mainstream method due to its simple structure, operational convenience, and relatively low energy consumption [2]. During high-pressure gaseous hydrogen refueling processes, the accurate determination of state parameters such as temperature and pressure within the storage tank is crucial. These parameters are key indicators for assessing the operational status of the hydrogen storage tank and are core elements for ensuring the safety and stability of the refueling process. However, under high-pressure conditions, the physical and chemical properties of hydrogen deviate significantly from those of an ideal gas. Factors such as intermolecular interactions and the volume of the molecules themselves exert a non-negligible influence on the gas state. The traditional ideal gas equation of state (EOS) cannot accurately describe the actual state of high-pressure hydrogen and is, therefore, unsuitable for directly calculating parameters such as temperature and pressure within the storage tank [3].

The gas EOS serves as a critical tool for analyzing the thermal effects inside hydrogen storage tanks during refueling. It quantifies the dynamic relationships between pressure, temperature, and volume, and is indispensable for the numerical simulation of hydrogen refueling, the development of refueling protocols, and safety assessments. Since van der Waals proposed the first EOS accounting for intermolecular forces (VDW EOS) in 1873, numerous researchers have conducted in-depth studies on gas EOS. The evolution of EOS has moved from general-purpose to specialized, high-precision models. It begins with concise but limited cubic equations (e.g., Van der Waals and the more advanced Peng–Robinson), progresses to more complex multiparameter formulations (e.g., Benedict–Webb–Rubin) for better accuracy, and culminates in modern Helmholtz free energy-based equations (e.g., NIST Leachman). These state-of-the-art models, offering great accuracy over wide ranges, are embedded in software like NIST REFPROP, signifying a shift from hand calculations to digital tools [4]. Chen et al. [3] proposed a simplified real gas EOS for hydrogen; compared against the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) reference data, it showed maximum errors of 1.1% and 3.8% within the temperature ranges of 253 K to 393 K and 173 K to 393 K, respectively. Nasrifar et al. [5] employed eleven different EOSs to predict various properties of standard hydrogen and identified the most suitable models through comparison with experimental data. Bai-gang et al. [6] proposed a high-precision EOS where the error in hydrogen consumption remained within 0.5% under specific pressure and temperature ranges. Kontogeorgis et al. [4] discussed the capabilities, limitations, current status, and future challenges of EOS, including those with general applicability. Peng et al. [7] proposed a new simplified virial-type EOS—the Virial–Peng–Long (VPL) EOS—where the third to fifth virial coefficients are expressed using empirically fitted formulas. Bilgili et al. [8], through simulation analysis of different real gas and ideal gas EOSs, found that different EOSs significantly impact the calculated tank temperature and pressure, and the refueling time also varies slightly depending on the EOS used.

As the technical requirements for hydrogen storage continue to increase, selecting an appropriate gas EOS to calculate the thermodynamic state within hydrogen storage tanks accurately has become a pressing issue in the field of hydrogen energy. This paper aims to investigate the application of different gas EOSs in calculating the thermodynamic state of high-pressure hydrogen storage tanks. Through a comparative analysis of results from various EOSs, this study aims to provide a scientific basis for selecting the appropriate EOS for practical engineering applications.

2. Development and Validation of a Hydrogen Storage Tank Model

2.1. Development of a Hydrogen Storage Tank Model

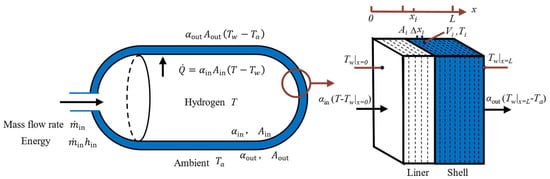

To investigate the effect of different gas EOSs on the calculation accuracy of temperature and pressure inside the storage tank, this study first establishes a zero-dimensional gas and one-dimensional tank wall model (0D1D) for the hydrogen storage tank, as shown in Figure 1. Experimental research in Ref. [9] indicates that the temperature distribution within the tank is relatively uniform during the hydrogen refueling process. Therefore, it is reasonable to treat the hydrogen gas zone as a zero-dimensional lumped-parameter model during refueling. The tank wall is considered a multi-layer structure, with heat conduction occurring sequentially through each radial layer. The temperature distribution within each cylindrical layer is assumed to be uniform.

Figure 1.

Zero-dimensional gas and one-dimensional tank wall model for the hydrogen storage tank.

During refueling process, the mass conservation of hydrogen can be expressed as [10]

where represents the mass of hydrogen in the storage tank (kg); represents the mass flow rate of hydrogen (kg/s).

Heat exchange occurs between the hydrogen and the inner wall of the storage tank. The energy conservation of hydrogen can be expressed as [11]

where represents the specific internal energy of hydrogen; represents the specific enthalpy of the inflow hydrogen (J/kg); and represent the temperature of the hydrogen and the temperature of the inner wall of the tank (K), respectively; represents the surface area of the inner wall of the tank (m2); represents the heat transfer coefficient between the hydrogen and the inner wall of the tank (W/m2/K); , is the Reynolds number; . and are the thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of the hydrogen; and are the inner diameter of the tank and the inlet injector.

Meanwhile, heat exchange occurs between the outer wall of the tank and the surrounding ambient air. The energy conservation of the tank wall can be expressed as [11]

where represents the average temperature of the tank wall (K); represents the specific heat capacity of the tank wall (J/kg/K); represents the mass of the tank wall (kg); and represent the temperature of the outer wall of the tank and the ambient temperature (K), respectively; represents the heat transfer coefficient between the outer wall of the tank and the ambient (W/m2/K); , , . is the Prandtl number of the air; , , , and are the thermal conductivity, dynamic viscosity, specific heat capacity at constant pressure, density and velocity of the air, respectively; is the outer diameter of the tank; represents the surface area of the outer wall of the tank (m2).

Heat exchange occurs internally inside the tank wall via thermal conduction. As shown in Figure 1, the middle part of the elliptical hydrogen storage vessel is a hollow cylinder, and both ends are hollow hemispheres. The wall thickness of the tank is much smaller than its inner diameter, so that the curvature effect can be neglected. Therefore, the one-dimensional radial problem in cylindrical or spherical coordinates can be simplified to a flat-plate model in Cartesian coordinates. After discretizing the tank wall into 15 concentric layers, each thin layer can be treated as a planar unit. This approach is the same as that used in Ref. [12]. The thermal conduction equations and the boundary conditions of the tank wall can be expressed as [12]

where represents the thickness of the tank wall (m); represents the density of the tank wall (kg/m3); represents the thermal conductivity of the tank wall material (W/m/K).

Once the hydrogen temperature inside the tank is calculated, the hydrogen pressure can be determined using real gas EOS. There are many types of real gas EOS, such as the Abel-Nobel EOS, the van der Waals EOS, and its modified forms like Redlich–Kwong, Soave, and Peng–Robinson. Another method is based on the database of the NIST, which can be expressed as

where R represents the universal gas constant, with a value of 8.314 J/mol/K. represents the molar mass of hydrogen, with a value of 2.0159 × 10−3 kg/mol. represents the hydrogen pressure inside the tank (Pa). represents the volume of the tank (m3). represents the compressibility factor. , , , , , and Z can be obtained from the database of the NIST.

2.2. Validation of the Hydrogen Storage Tank Model

Based on the MATLAB/Simulink (Version: 9.4.0.813654 (R2018a)) software platform, the 0D1D numerical model of a storage tank for the hydrogen refueling process was established. To verify the accuracy of the 0D1D numerical model of the hydrogen storage tank, the physical parameters and experimental data of a 90.5 L hydrogen storage tank with a nominal working pressure (NWP) of 70 MPa from Ref. [13] were used for comparative validation. The physical parameters of the tank are shown in Table 1, and the initial and boundary conditions are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of the hydrogen storage tank from the Ref. [13].

Table 2.

Initial and boundary conditions from the Ref. [13].

In our previous work [14], this 0D1D model underwent extensive validation. The simulation results agree well with the experimental data, as illustrated in Figure 3 of Ref. [14], further substantiating the validity of the one-dimensional thermal conductivity model for the elliptical hydrogen storage vessel.

3. Thermodynamic States in Storage Tank Calculated by Different EOSs

During the hydrogen refueling process, the pressure of hydrogen inside the tank is high. Under these conditions, using the ideal gas EOS will lead to significant errors, and a real gas EOS should be employed instead. Many types of real gas EOS can be used for hydrogen. A detailed review of the main has been conducted, and the limitations and advantages of each EOS have been identified, as shown in Table 3. Moreover, we conducted further analysis on several representative EOSs among them.

Table 3.

The main real gas EOSs used for hydrogen and their limitations and advantages.

3.1. van der Waals Equation of State

A famous and influential real gas EOS is the van der Waals EOS:

where a and b are the parameters, v is the molar volume of hydrogen (m3/mol). At the critical point of the substance, where T = Tc, p = pc and v = vc (Tc, pc, and vc represent the critical temperature, critical pressure, and critical molar volume of the substance), the following conditions hold: and . Thus, we can obtain

Then, at the critical point, solving Equations (8)–(10), it can be calculated that , , . Combining critical thermodynamic parameters of hydrogen obtained experimentally, namely Tc = 33.3 K, pc = 1.28 × 106 Pa, vc = 6.5 × 10−5 m3/mole [25], it can be calculated that a = 25.2 J·m3/kilomole2, b = 0.027 m3/kilomole.

3.2. Modified Forms for van der Waals Equation of State

To further improve the accuracy of the gas EOS, many modified forms for van der Waals EOSs have been proposed. Among them, the modifications of Redlich–Kwong, Soave, and Peng–Robinson are widely used.

The modified form of Redlich–Kwong can be expressed as [8]

The modified form of Soave can be expressed as [8]

where .

The modified form of Peng–Robinson can be expressed as [8]

Referring to the method adopted for Equation (8), the expressions for parameters a and b in the Redlich–Kwong, Soave, and Peng–Robinson EOSs were solved. The results are shown in Table 4. By substituting the experimentally obtained critical temperature Tc = 33.3 K, critical pressure pc = 1.28 × 106 Pa, and critical molar volume vc = 6.5 × 10−5 m3/mole of hydrogen into the expressions for parameters a and b in Table 4, the experimental values of a and b can be calculated.

Table 4.

Parameter values in different modified forms for van der Waals equation of state.

The Joule–Thomson inversion curve is a highly sensitive test for EOS, particularly near the critical point. It can therefore be used to evaluate the parameters in different forms of the EOS. The Joule–Thomson inversion curve data for hydrogen are from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Technical Note D-6807 (1972) [26]:

where , , and are the dimensionless form of reduced temperature, reduced pressure, and reduced molar specific volume (, , ). A0 = −15.5988252, A1 = 26.0321395, A2 = −9.7459013, A3 = 2.4207304, A4 = −0.49105816, A5 = 0.05932495, and A6 = −0.002913248.

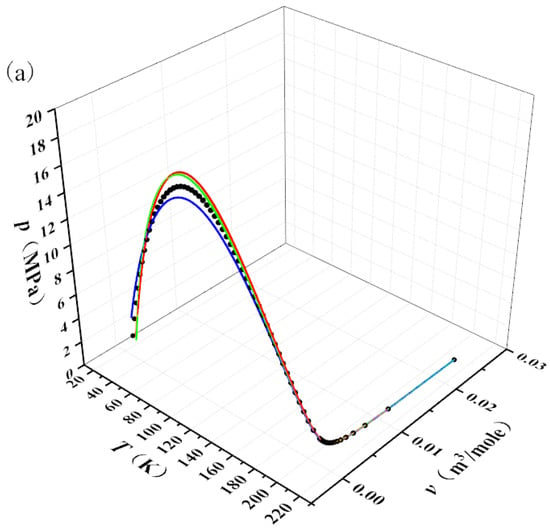

Set the range of from 0.9 to 6.28 with a step size of 0.01. This range ensures that both the temperature and pressure of hydrogen calculated by Equation (14) are positive. The Joule–Thomson inversion curve can be calculated using Equation (14). By combining the experimentally obtained critical temperature, critical pressure, and critical molar volume of hydrogen, the corresponding value of for the Joule–Thomson inversion curve can be calculated. Furthermore, since , , and , a three-dimensional spatial curve of (, , ) can ultimately be plotted, as shown by the black curve in Figure 2a, which can be regarded as standard data for the real gas EOS.

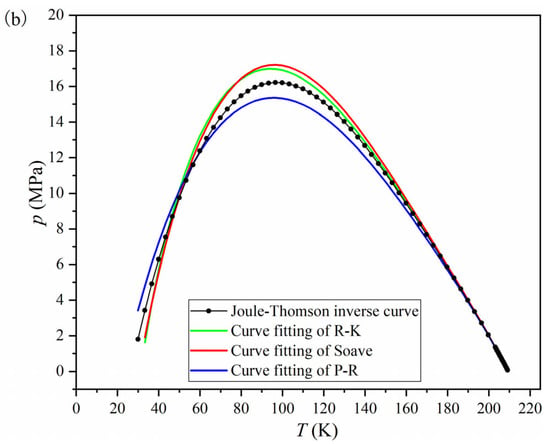

Figure 2.

Fitting results for modified van der Waals EOSs using the Joule–Thomson inversion curve. (a) Fitted curve in three-dimensional space. (b) Projection of the three-dimensional fitted curve onto the p–T plane.

The Redlich–Kwong EOS, Soave EOS, and Peng–Robinson EOS were used to fit the black curve in Figure 2a. During the fitting process, the value of parameter b was fixed to the experimental value listed in Table 4 to facilitate comparison between the fitted value and the experimental value of parameter a. The parameter values determined by the fitting are shown as the fitted values in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that the R2 obtained from fitting the three EOS are all greater than or equal to 0.99, indicating that the fitting process is accurate and reliable. The comparison between the fitted and experimental values of parameter a in Table 4 reveals that the relative error of parameter a in the Redlich–Kwong EOS is smaller. Figure 2b visually demonstrates that the fitted curve of the Redlich–Kwong EOS is closer to the standard Joule–Thomson inversion curve. Therefore, this study selects the Redlich–Kwong EOS for further research. Using the experimental values of parameters a and b, the specific form of the Redlich–Kwong EOS is determined as

where p is the pressure of hydrogen (Pa), T is the temperature of hydrogen (K), v is the molar volume of hydrogen (m3/mol), and R is the universal gas constant, with a value of 8.314 J/mole/K.

3.3. Polynomial Equation of State

Bourgeois and his collaborators argued that employing calculations based on the NIST database appears more suitable for simulating high-pressure hydrogen refueling processes than any other types of EOS [27]. However, data acquisition from the NIST database requires real-time table lookup operations, and the data are not presented in an explicit analytical form. In view of this, to enhance the convenience and efficiency of data usage, it is necessary to explore and develop a reliable equation that can directly represent NIST data in an explicit analytical form. This equation can be expressed as a polynomial, utilizing different parameter values to represent various thermophysical properties of hydrogen. The parameter values can be determined by fitting against data generated from the NIST database. This polynomial EOS will be a high-performance computational model specifically designed for hydrogen. Its customized architecture enables it to reproduce reference data within the target range accurately. Compared to the complex reference equations used in NIST REFPROP, its explicit polynomial structure offers a significant computational efficiency advantage, making it particularly suitable for numerical simulation scenarios that require high-frequency, high-precision thermodynamic calculations. First, the polynomial form of the EOS can be defined as

where represents the density of hydrogen (mol/L), T represents the temperature of hydrogen (K), and p represents the pressure of hydrogen (MPa). and are the parameters. When N = 5, the specific form of the polynomial EOS (Equation (16)) is given by

The hydrogen temperature varied from 223.15 K to 373.15 K in increments of 2 K, while the hydrogen pressure varied from 0.1 MPa to 100.1 MPa in increments of 2 MPa. Different combinations of temperature and pressure were employed, resulting in 3876 distinct hydrogen temperature–pressure data pairs. Calculations based on the NIST database were performed to obtain 3876 corresponding sets of (p, T, ρ) data. These data were used to fit the polynomial EOS (Equation (17)), and the parameter values are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Parameter values in the polynomial equation of state.

3.4. Pressure in Hydrogen Storage Tank Calculated by Different Equations of State

Based on the validated 0D1D model described above, simulation studies were conducted using the van der Waals EOS, Redlich–Kwong EOS, the polynomial EOS, and the NIST database-based method. For all cases, the refueling time was set to 3 min, which is the recommended refueling time for light-duty fuel cell vehicles according to the SAE J2601 hydrogen refueling protocol. The calculation results indicate that the choice of EOS has a minor impact on the computed hydrogen temperature but a significant effect on the computed hydrogen pressure.

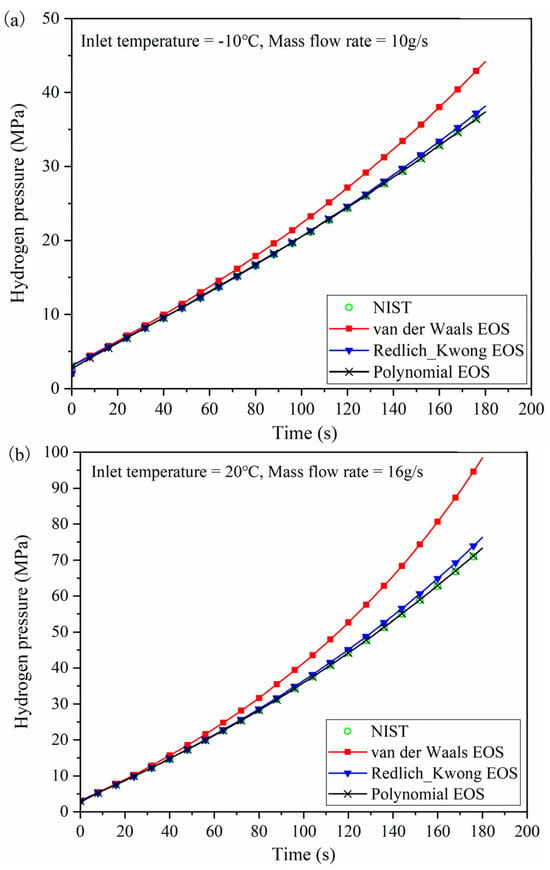

Figure 3 compares the hydrogen pressure calculated using different forms of the EOS. Figure 3a shows that when using the final hydrogen pressure calculated based on the NIST database as the benchmark, the relative error of the final hydrogen pressure calculated by the polynomial EOS is 0.30%, while it is 1.83% for the Redlich–Kwong EOS, and 17.90% for the van der Waals EOS. This indicates that the polynomial EOS aligns most closely with the NIST-based calculations, whereas the van der Waals EOS exhibits lower accuracy. The Redlich–Kwong EOS, a modified form of the van der Waals EOS, demonstrates higher accuracy than the van der Waals EOS, suggesting that the modifications have improved upon the original van der Waals EOS to some extent.

Figure 3.

Hydrogen pressure calculated using different EOSs under varying inlet temperatures and mass flow rates. (a) Inlet temperature of −10 °C, mass flow rate of 10 g/s. (b) Inlet temperature of 20 °C, mass flow rate of 16 g/s.

Figure 3b shows a similar trend to Figure 3a, but the final hydrogen pressure in Figure 3b is higher. The relative error between the van der Waals EOS and the NIST data is 34.57%, which is greater than the error observed in Figure 3a. This indicates that as the hydrogen pressure inside the tank increases, the deviation in the pressure calculated using the van der Waals EOS becomes more significant. In summary, due to the high hydrogen pressures encountered during the refueling process, using the NIST database-based calculations or the polynomial EOS can help reduce computational errors. Although the polynomial EOS offers high accuracy, it involves more coefficients and a relatively complex form. The Redlich–Kwong EOS provides relatively high accuracy with fewer parameters and a simpler form.

4. Conclusions

This study established and validated a zero-dimensional gas and one-dimensional tank wall model (0D1D) for a hydrogen storage tank. The parameter values in the van der Waals equation of state (EOS) and its modified forms (Redlich–Kwong, Soave, and Peng–Robinson) were calculated using mathematical methods. The accuracy of the modified forms for van der Waals EOS was examined using the Joule–Thomson inversion curve. A polynomial EOS was constructed, and the values of its parameters were determined. The hydrogen temperature and pressure calculated by the van der Waals EOS, the Redlich–Kwong EOS, and the polynomial EOS were compared against those calculated based on the NIST database. Within the scope of the initial conditions and boundary conditions set in this study, the results are as follows:

- (1)

- A lumped-parameter thermodynamic model integrating a zero-dimensional gas model and a one-dimensional tank wall model (0D1D) was developed for simulating the hydrogen refueling process. The model demonstrates high accuracy, as validated through comparative analysis with experimental data.

- (2)

- Among the modified forms for van der Waals EOS (Redlich–Kwong, Soave, and Peng–Robinson), the fitting curve of the Redlich–Kwong EOS more closely approximates the Joule–Thomson inversion curve, implying that the Redlich–Kwong EOS exhibits higher accuracy than the Soave and Peng–Robinson EOSs.

- (3)

- Using the final hydrogen pressure calculated by the NIST database as the benchmark, the relative error of the polynomial EOS is 0.30%, followed by 1.83% for the Redlich–Kwong EOS, and 17.90% for the van der Waals EOS. This indicates that the polynomial EOS exhibits higher accuracy, followed by the Redlich–Kwong EOS, while the van der Waals EOS demonstrates lower accuracy.

This research provides a theoretical basis for selecting an appropriate EOS in the numerical simulation of the hydrogen refueling process. Moreover, the van der Waals EOS and its modified forms (Redlich–Kwong, Soave, Peng–Robinson) in this article are all mean-field EOSs. However, hydrogen in practical settings may operate near metastable or near-spinodal conditions, where mean-field EOS become unreliable and fluctuations materially affect dynamics and control phase behavior [28]. Future work will incorporate intermolecular interactions details and thermal hydrodynamic fluctuations to extend the applicability of the current model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and J.X.; methodology, T.Y. and C.L.; software, X.W.; validation, Q.X.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, Q.X.; resources, C.Y. and J.X.; data curation, Q.X.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and Q.X.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and T.Y.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, C.Y.; project administration, H.L. and X.W.; funding acquisition, H.L. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (Fund name: 2024 China University–Industry Research Innovation Fund. Fund number: 2024MZ015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EOS | Equation of state |

| NWP | Nominal working pressure |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| PRR | Pressure ramp rate |

| SAE | Society of Automotive Engineers |

| 0D1D | Zero-dimensional gas and one-dimensional tank wall |

References

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Lang, J.; Yuan, W.; An, G.; Lei, T.; Yan, J. A comprehensive review of advances and challenges of hydrogen production, purification, compression, transportation, storage and utilization technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kareem, S.S.A.; Hassan, Q.; Fakhruldeen, H.F.; Hanoon, T.M.; Jabbar, F.I.; Algburi, S.; Khalaf, D.H. A review on physical and chemical hydrogen storage methods for sustainable energy applications. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 8, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zheng, J.; Xu, P.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Bie, H. Study on real-gas equations of high pressure hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 3100–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogeorgis, G.M.; Liang, X.; Arya, A.; Tsivintzelis, I. Equations of state in three centuries. Are we closer to arriving to a single model for all applications? Chem. Eng. Sci. X 2020, 7, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrifar, K. Comparative study of eleven equations of state in predicting the thermodynamic properties of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 3802–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai-gang, S.; Dong-sheng, Z.; Fu-shui, L. A new equation of state for hydrogen gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 932–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Long, X. A new simplified virial equation of state for high temperature and high pressure gas. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 015119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, M.; Yumşakdemir, R.F. Effects of real gas equations on the fast-filling process of compressed hydrogen storage tank. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Pan, X.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L. Experimental and numerical study on temperature rise within a 70 MPa type III cylinder during fast refueling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 10956–10962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Charge-discharge cycle thermodynamics for compression hydrogen storage system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5531–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. A dual zone thermodynamic model for refueling hydrogen vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 8780–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothuizen, E.; Mérida, W.; Rokni, M.; Wistoft-Ibsen, M. Optimization of hydrogen vehicle refueling via dynamic simulation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4221–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, T.; Ammouri, F.; Weber, M.; Knapik, C. Evaluating the temperature inside a tank during a filling with highly-pressurized gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11748–11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Xiao, J.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R.; Yang, T. Effects of filling strategies on hydrogen refueling performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waals, J.D.v.d. Molekulartheorie eines Körpers, der aus zwei verschiedenen Stoffen besteht. Z. Phys. Chem. 1890, 5U, 133–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, O.; Kwong, J.N.S. On the Thermodynamics of Solutions. V. An Equation of State. Fugacities of Gaseous Solutions. Chem. Rev. 1949, 44, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soave, G. Equilibrium constants from a modified Redlich-Kwong equation of state. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1972, 27, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.-Y.; Robinson, D.B. A New Two-Constant Equation of State. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1976, 15, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.; Webb, G.B.; Rubin, L.C. An Empirical Equation for Thermodynamic Properties of Light Hydrocarbons and Their Mixtures, I. Methane, Ethane, Propane and n-Butane. J. Chem. Phys. 1940, 8, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.I.; Kesler, M.G. A generalized thermodynamic correlation based on three-parameter corresponding states. AIChE J. 1975, 21, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leachman, J.; Jacobsen, R.; Penoncello, S.; Lemmon, E.W. Fundamental Equations of State for Parahydrogen, Normal Hydrogen, and Orthohydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2009, 38, 721–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, O.; Wagner, W. The GERG-2008 Wide-Range Equation of State for Natural Gases and Other Mixtures: An Expansion of GERG-2004. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2012, 57, 3032–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Pruß, A. The IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2002, 31, 387–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E.W.; Bell, I.H.; Huber, M.L.; McLinden, M.O. NIST Standard Reference Database 23: Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties-REFPROP, Version 10.0; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, F.W.; Salinger, G.L. Thermodynamics, Kinetic Theory, and Statistical Thermodynamics; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; Available online: http://narosa.com/books_display.asp?catgcode=978-81-85015-71-2 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Hendricks, R.C.; Peller, I.C.; Baron, A.K. Joule-Thomson Inversion Curves and Related Coefficients for Several Simple Fluids; NASA Technical Note D-6807; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1972; Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19720020315/downloads/19720020315.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Bourgeois, T.; Ammouri, F.; Baraldi, D.; Moretto, P. The temperature evolution in compressed gas filling processes: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2268–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulli, M.; Biferale, L.; Falcucci, G.; Sbragaglia, M.; Yang, D.; Shan, X. Metastable and unstable hydrodynamics in multiphase lattice Boltzmann. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 045304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).