Abstract

The current agent-based evolutionary models for animal communication rely on simplified signal representations that differ significantly from natural vocalizations. We propose a novel agent-based evolutionary model based on text-to-audio (TTA) models to generate realistic animal vocalizations, advancing from VAE-based real-valued genotypes to TTA-based textual genotypes that generate bird songs using a fine-tuned Stable Audio Open 1.0 model. In our sexual selection framework, males vocalize songs encoded by their genotypes while females probabilistically select mates based on the similarity between males’ songs and their preference patterns, with mutations and crossovers applied to textual genotypes using a large language model (Gemma-3). As a proof of concept, we compared TTA-based and VAE-based sexual selection models for the Blue-and-white Flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana)’s songs and preferences. While the VAE-based model produces population clustering but constrains the evolution to a narrow region near the latent space’s origin where reconstructed songs remain clear, the TTA-based model enhances the genotypic and phenotypic diversity, drives song diversification, and fosters the creation of novel bird songs. Generated songs were validated by a virtual expert using the BirdNET classifier, confirming their acoustic realism through classification into related taxa. These findings highlight the potential of combining large language models and TTA models in agent-based evolutionary models for animal communication.

1. Introduction

Agent-based modeling has contributed significantly to our understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of social behaviors [1], particularly the emergence of communicative interactions [2,3,4]. Models based on this approach demonstrate how simple individual-level interactions among agents yield the evolution of signaling behaviors. However, the signals in these models differ from those observed in real-world communication systems in terms of their complexity. For example, in abstract models, signals are represented using numbers and symbols, which are qualitatively different from the complex communication signals produced by organisms in nature.

On the other hand, deep learning techniques are contributing to computational bioacoustics [5], and generative models have been used to study animal communication and ecoacoustics. Variational autoencoders (VAEs) [6] have demonstrated effectiveness in modeling latent variables in both experimental and ecological acoustic data [7] and have recently shown promise in synthesizing bird songs [8]. Beguš et al. proposed a method that explored the latent space of a generative model trained on sperm whale vocalizations. By pushing latent variables to their extremes and applying causal inference techniques, their approach reveals interpretable and biologically meaningful acoustic features, offering a novel framework for investigating unknown communication systems [9].

It should be noted that text-to-audio (TTA) models, as an emerging generative audio model category that includes AudioGen [10] and Stable Audio [11] models, have gained attention for their ability to synthesize general and realistic audio based on textual descriptions. While TTA models have progressed in music generation and human speech creation, their application to animal sound generation remains limited. Additionally, with the rapid development of large language models (LLMs), their generative capabilities for text can be used in the genetic operations within evolutionary models [12]. Suzuki et al. recently proposed an evolutionary model of personality traits related to cooperative behavior using an LLM [13]. In the model, linguistic descriptions of personality traits related to cooperative behavior are used as genes, and the LLM is asked to slightly modify the parent gene toward cooperative or selfish. They demonstrated the emergence and collapse of cooperative relationships based on the evolution of various types of personality trait descriptions, which simple computational models could not represent. Fernando et al. proposed a framework that utilizes prompts to describe mutation methods, effectively enhancing genetic evolution [14]. These discussions suggest that a TTA model can be used to construct an agent-based evolutionary model in which individuals interact with each other based on realistic vocalizations derived from text-based genetic descriptions. Furthermore, it is possible to discuss the effects of the emerging vocalizations in the models on individual behavior in real ecology.

Our objective is to extend agent-based models to biological evolution by harnessing the rich and realistic generative capabilities of generative models. Such advances could lay the groundwork for future interactions with real ecological systems. As a preliminary approach, Suzuki et al. constructed an agent-based evolutionary model for animal vocalizations utilizing a VAE, exemplified through case studies on several bird species (e.g., the Japanese Bush-Warbler (Horornis diphone) [15] and the Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus) [16]). They focused on a sexual selection model, inspired by the mathematical model of sympatric speciation by sexual selection [17], where male song and female preference genotypes were represented as vectors within the 2D latent space of a VAE trained to reconstruct songs of the focal species. Spectrogram images generated from these vectors were interpreted as vocalizations and song preferences. Females probabilistically choose males based on the similarity between the spectrogram images of males’ songs and their own preference spectrogram images. The results indicated that clear and moderately complex vocalizations were preferentially selected during the evolutionary process and sometimes exhibited segregation of the population, potentially leading to sympatric speciation. However, their evolutionary model still faced several limitations. First, the evolutionary process was strongly constrained by the limitations of the latent space, leading to rapid population convergence. Second, the diversity of the generated songs was restricted to interpolation within the training data space. This could be due to the specific properties of the latent space.

To explore further possibilities of applying generative models with different genotype spaces, this study extends the above approach by replacing the VAE with a TTA model. The TTA model enables us to assume a more flexible genetic space based on linguistic expressions and diverse vocal representations. This approach, which couples generative models (e.g., LLM) with an agent-based model, has recently been referred to as a generative agent-based model (GABM) and has been used to model complex social systems [18]. While many pilot studies have focused on the dynamics of human social systems, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have proposed such approaches to understanding the evolution of biological and ecological systems. This trend of applying generative AI is expanding across species, including research into sequence-based dolphin communication (DolphinGemma) [19] and unified bioacoustic analyses across multiple taxa (the Earth Species Project [20]).

We fine-tuned the text-to-audio model, Stable Audio Open 1.0 (Stability AI) [11], using a dataset of Blue-and-white Flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana) songs collected in a field recording in a forest in Japan as part of a project of field observations of the spatial behavior of individual birds based on robot audition [16,21]. The trained model is expected to generate songs that share characteristics with, but are not identical to, those of the focal species, based on various textual descriptions of the species’ songs. These descriptions serve as genes encoding both male songs and female preferences in the model. Additionally, we utilize a large language model (LLM), Gemma-3 (Google) [22], to express genetic mutations in textual form.

Because the previous preliminary analysis [15,16] did not discuss the evolution process in detail, we also constructed a VAE-based evolutionary model using the same dataset and methods as Suzuki et al. [16], in addition to the TTA-based model, for comparison. We conducted multiple evolutionary experiments with both models and analyzed the evolutionary dynamics of the genotypes and phenotypes through visualization and quantitative methods. Our results demonstrate that the TTA-based model promotes greater diversity in evolved songs while preserving the biological characteristics of similar species’ songs, compared to the VAE-based model. This highlights its potential to generate diverse artificial bird songs under biologically realistic constraints.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the field recording dataset and describes the training procedures for the two generative audio models (the VAE and TTA). Section 3 details the two evolutionary models and their implementation. Section 4 defines two quantitative metrics used to analyze the evolutionary dynamics. Section 5 presents visualization and quantitative results of evolutionary experiments based on the VAE evolutionary model and the TTA evolutionary model. Finally, the Section 6 summarizes the findings, highlights the advantages of the proposed TTA-based evolutionary model, and proposes directions for further research.

2. The Dataset and Generative Audio Models

2.1. The Field Recording and the Dataset

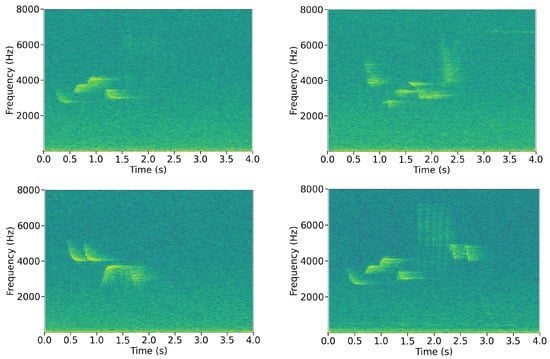

We selected the Blue-and-white Flycatcher (BAWF, Cyanoptila cyanomelana) as the target bird species for our evolutionary experiments. This summer bird is widely distributed in Japan, known for its clear and melodious vocalizations. Field recordings of the BAWF were conducted in the Inabu Field, an experimental forest of the Field Science Center, Graduate School of Bioagricultural Sciences, Nagoya University, in central Japan (Figure 1). The recording trials were conducted on 5 June 2024 using a 16-channel microphone array system (Chirpy type-S; System in Frontier Inc., Tokyo, Japan) in 16-bit, 16 kHz format. We manually selected 100 sound clips of the songs from the recording (11:00 a.m. to 11:20 a.m. on 5 June 2024) as the training samples (Figure 2). The duration of each clip was 4 s.

Figure 1.

Recording field.

Figure 2.

Example spectrograms of the four main song types of the Blue-and-white Flycatcher in the dataset. Color intensity represents signal strength.

We constructed two generative audio models to implement different phenotype expressions from genotype using the dataset. One model was a VAE model that converts numerical genotypes into spectrograms of bird songs proposed in a previous study [15,16]. The other was a TTA model that generates the audio (wave files) of songs from text-based genotypes, which was newly introduced in this study. In the training of both models, we did not apply data augmentation (e.g., noise injection, time stretching, or pitch shifting), as such operations could introduce artificial features inconsistent with real bird songs and thereby reduce the ecological validity of the generated songs after training.

All of the codes and data used in the paper will be made available after publication.

2.2. Variational Autoencoder Training

The first model was a convolutional variational autoencoder (VAE) designed to learn a latent representation of the recorded bird songs, based on the architecture described by Suzuki et al. [16]. The model architecture follows a typical encoder–decoder framework. The encoder comprises eight convolutional layers with progressively increasing channel sizes (1→8→16→32→64) and three downsampling operations, reducing the input spectrogram dimensions from 496 × 128 to 62 × 16. The resulting feature maps are flattened and passed through three fully connected layers, which compress them into a two-dimensional latent representation. In the variational setting, two separate branches estimate the mean and variance parameters of the latent distribution. The decoder mirrors the encoder in a symmetric architecture to reconstruct the input spectrograms. We adopted this network architecture following the study on latent space visualization, characterization, and generation of diverse vocal communication signals [23].

A total of 1004 s sound clips of the above recording data were converted into grayscale spectrogram images 496 × 128 pixels in size and used as the training data. The VAE, with a two-dimensional latent space, was trained for 2000 epochs using a batch size of 16 and the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1 × 10−4. The training objective combined a binary cross-entropy reconstruction loss with a Kullback–Leibler divergence term, weighted by a factor of 3, to encourage both accurate reconstruction and a well-structured latent space.

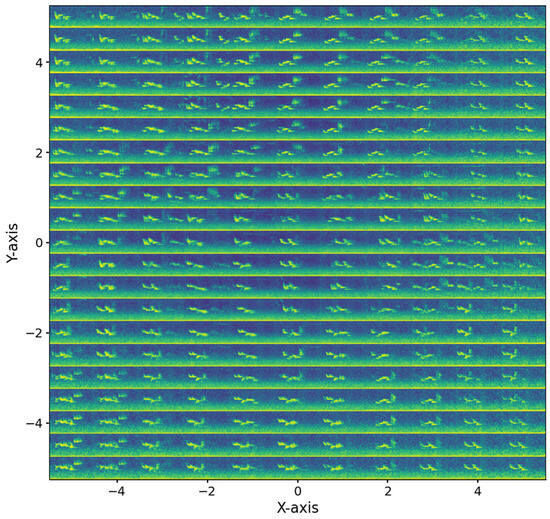

After training, representative spectrograms were generated by sampling across the two-dimensional latent space. These spectrograms were mapped back into the audio domain and visualized within the latent space coordinate system (Figure 3). The generated songs reproduced key acoustic features of the original bird songs and showed increasing variation and noise with a greater distance from the origin.

Figure 3.

Latent space of Blue-and-white Flycatcher songs encoded by the VAE. Songs near the origin in the center are most similar to the songs of wild birds in the field. Color intensity represents signal strength.

2.3. Text-to-Audio Model Fine-Tuning

The second model was constructed by fine-tuning the pre-trained Stable Audio Open 1.0 model developed by Stability AI [11] under the Stability AI Community License (© Stability AI Ltd., London, UK; license details available at https://huggingface.co/stabilityai/stable-audio-open-1.0/blob/main/LICENSE.md, accessed 1 September 2025) (powered by Stability AI). This text-to-audio generative model utilizes transformer diffusion techniques, allowing it to produce artificial sounds based on text prompts. The model architecture combines a transformer-based language encoder, which processes textual prompts into conditioning vectors, with a diffusion-based audio decoder that iteratively generates waveforms from noise. For further details, see the model website: https://huggingface.co/stabilityai/stable-audio-open-1.0 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

We used the audio files of the above 100 sound clips as training samples for fine-tuning. We paired these files with a textual prompt, “The bird song of a Blue-and-white Flycatcher in the quiet forest in the morning”, for training. This text prompt was designed to reflect the essential components of animal soundscapes, namely the species’ characteristics, its natural habitat, and the typical vocalization period. The training was conducted using the official training toolkit available at https://github.com/Stability-AI/stable-audio-tools (accessed on 1 September 2025) and the publicly available pretrained model, which was carried out for 30 epochs with a batch size of 64 and 16-bit mixed precision. The optimizer used was AdamW, with a learning rate of . The loss function was the mean squared error (MSE), applied to waveform reconstruction in accordance with the denoising score matching objectives.

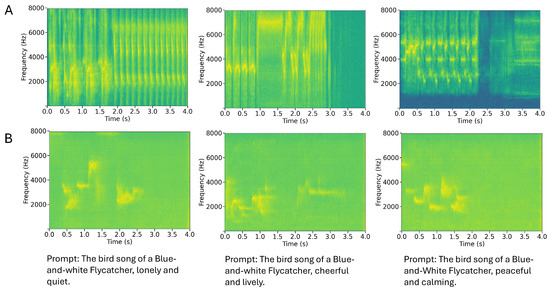

Figure 4 shows several examples of the songs generated by the models before and after fine-tuning using different additional prompts with various descriptions of songs, such as “lonely and quiet”. The sounds generated with the original model appear to be vocalizations of some species, but they differ from those of the BAWF before fine-tuning. After fine-tuning, the generated songs exhibit diverse and unique acoustic structures. For instance, compared with the original BAWF recordings (Figure 2), they differ in their syllable composition, frequency modulation patterns, and temporal rhythms. Nevertheless, the generated songs consistently preserve the properties of the BAWFs’ songs, including a typical frequency range of 2–8 kHz, an overall vocalization duration of approximately 3 s, and a multi-syllabic structure with short inter-syllable intervals. Based on visual inspection of the spectrograms and an auditory evaluation of the songs generated in the experiments, we think that the fine-tuned TTA model was able to generate songs similar to the original BAWF songs, although more concrete evidence is still required.

Figure 4.

The generated songs by the original and fine-tuned TTA models. Color intensity represents signal strength. (A) Before training with prompts; (B) after training with the same prompts.

We employed the BirdNET classifier [24] as a virtual expert to examine whether the generated songs preserved the natural vocalization patterns of the BAWF. The songs were classified as multiple species, implying they shared realistic acoustic properties with related taxa that are acoustically similar to the BAWF. This supports that the generated songs retained BAWF-relevant properties. Details are given in Section 4.3 and Section 5.3.

In addition, although this is unclear, there appears to be some similarity in the properties (e.g., temporal changes) between the sounds produced with the same prompt. This suggests that the additional descriptions in each prompt, at least in part, are reflected in the acoustic properties of the generated songs, implying that different prompts can yield diverse BAWF-like songs.

3. Evolutionary Models

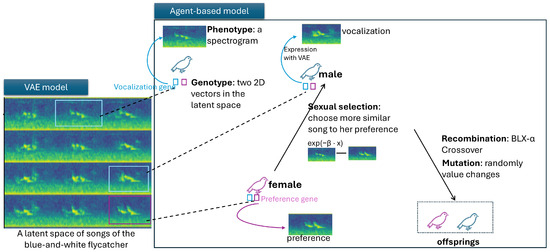

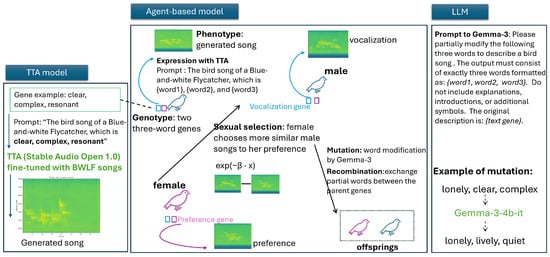

We implement the evolutionary model by Suzuki et al. [16], which uses a VAE (Figure 5). Then, we introduce the extended version incorporating a text-to-audio model and a large language model (Figure 6). Inspired by the mathematical model of sympatric speciation by sexual selection proposed by Higashi et al. [17], we assume that each individual in both evolutionary models possesses a genotype composed of two components: one gene encoding a male vocalization trait and the other encoding the corresponding female preference. This dual-gene structure mirrors the theoretical framework in which the coevolution of male secondary sexual traits (vocalization) and female mating preferences can lead to divergent evolution and reproductive isolation.

Figure 5.

The evolution model based on a VAE model. Color intensity of spectrograms represents signal strength.

Figure 6.

The evolution model based on a text-to-audio model. Color intensity of spectrograms represents signal strength.

In our evolutionary models, females select the male whose song is most similar to their preferred acoustic template, which is commonly assumed in mathematical models for sexual selection. As for bird songs, this rule is grounded in the theoretical framework that females possess auditory templates, which have been demonstrated across multiple functions, including species recognition, individual discrimination of neighbors versus strangers, and mate–offspring recognition [25,26,27]. Given the versatility of these auditory template mechanisms in various social contexts, they may extend to mate choice decisions [28]. The formation of this preferred acoustic template can involve both learning and innate factors. Our evolutionary model focuses on the latter, assuming that the template is primarily determined by genetic constraints. We computationally implement this innate template as a preference spectrogram. Consequently, the process of mate choice is modeled by calculating the similarity between a male’s song spectrogram and this internal reference, with the female selecting the male who provides the closest match.

3.1. The Evolutionary Model Based on the VAE

In this model (Figure 5), we assume two populations, each composed of N males and N females. Each individual has two real-valued genes. Each gene represents a 2D vector (or position) in the latent space, described by a pair of (x, y) coordinates (Figure 3). One gene is used to generate a song spectrogram vocalized by a male, and the other is used to generate a female preference spectrogram using the VAE, with (x, y) as the latent vector. In the initial population, both genes’ x and y coordinates are generated randomly within the range .

In each generation, females select one male from all males with a probability proportional to , where is a coefficient and x is defined as

where , , and and denote the pixel values at position in the male’s song spectrogram and the female’s preference spectrogram, respectively. x is the average difference in pixel values between the male’s song spectrogram and the female’s preference spectrogram.

Therefore, each female stochastically selects the male whose vocalization spectrogram is closest to her preference spectrogram. Two offspring are generated from the parental genes, incorporating both recombination and mutation. One is randomly assigned as male and the other as female.

Recombination is modeled as BLX- crossover [29] with a probability , which is a crossover method designed to produce offspring genes by combining the characteristics of the parents’ real-valued genes within a defined range. Mutation is modeled as the addition of a normal random value with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation to the original value, occurring in each x or y coordinate value with a probability . The trials are conducted over T generations.

3.2. The Evolutionary Model Based on the Text-to-Audio Model

Unlike the VAE-based evolutionary model, the genes for vocalization songs and preferences consists of two three-word texts describing some properties of songs (e.g., “clear, complex, resonant”). One is a gene used to generate a song vocalized by a male, and the other is a gene used to generate a female preference song (Figure 6). The gene expression involves utilizing the vocalizing gene or the preference gene to construct a prompt to generate a song of the BAWF. The prompt for gene expression is formatted as

The bird song of a Blue-and-white Flycatcher, which is {word1}, {word2}, and {word3}.

Here, {word1}, {word2}, and {word3} represent the three words from the corresponding three-word text gene. This prompt is used to generate a corresponding song using the fine-tuned model of Stable Audio Open 1.0, as mentioned above. This prompt can help the generated songs closely resemble the original songs of the BAWF while being different from them. We expect this genotype definition and the associated mutation/recombination mechanisms to enable the following features for representing birdsong variations and their genetic–phenotypic relationships. The semantic structure of the three-word genotype captures relationships between descriptive words representing distinct acoustic components (e.g., tone, rhythm, emotion), where semantic combinations enhance the expressiveness through richer acoustic features. Word diversity arising from mutation operations—including synonym substitution and semantic neighborhood sampling—encompasses the breadth of the available vocabulary, expanding the genotype search space and evolutionary potential. Syntactic variation is constrained by the fixed three-word format, maintaining structural consistency while enabling gradual evolutionary changes.

It should be noted that our goal is not to create songs that directly match the described properties but rather to use the creative ability of the TTA model to generate novel BAWF-like songs guided by these descriptions.

The sexual selection process in the TTA-based evolutionary model is the same as that in the VAE-based evolutionary model. In each generation, females select one male with a probability proportional to , where is a coefficient and x is defined in Equation (1). Two offspring are generated from the parental genes, incorporating both recombination and mutation. One offspring is randomly assigned as male and the other as female. The trials are conducted over T generations. A mutation is performed on each text gene of parents using a large language model named Gemma-3-4b-it, which is a 4.3-billion-parameter instruction-tuned model developed by Google and available at Hugging Face (https://huggingface.co/google/gemma-3-4b-it (accessed on 1 September 2025)). The mutation is introduced by a defined prompt with a probability . The prompt used is as follows:

Please partially modify the following three words to describe a bird song. The output must consist of exactly three words formatted as: word1, word2, word3. Do not include explanations, introductions, or additional symbols. The original description is: {text gene}.

Recombination will exchange partial words between the two vocalizing genes or the two preference genes of the parents of a male and a female with a probability . Each gene in the initial population was randomly generated by a large language model (LLM) using a prompt that instructed the model to produce three words describing a bird song. The prompt is as follows:

Generate three words to describe a birdsong. These words can be positive, negative, or neutral, and should represent different aspects of the sound. Use the format: word1, word2, word3. Please make sure that you do not add explanations or introductions. For example: sweet, lilting, vibrant.

For example, the prompt may generate an initial genotype “melodious, bright, rhythmic” (male gene) and “gentle, clear, harmonious” (female preference gene). A mutation might modify a single word from “bright” to "vibrant”, producing the offspring genotype “melodious, vibrant, rhythmic”. Recombination might combine two parent genotypes “melodious, vibrant, rhythmic” and “sweet, complex, flowing” to generate the offspring genotypes “melodious, complex, flowing” and “sweet, vibrant, rhythmic”.

4. Quantitative Analysis

To quantitatively analyze the evolutionary dynamics of genotypes and phenotypes in both evolution models, we defined two quantitative metrics. One is the diversity (D) of a set of vectors in the male song and female preference genotypes. The other is the affinity (A) between two sets of vectors, which seeks to capture how well females can select males that match their preferences.

4.1. Diversity

We define the diversity (D) of a vector dataset , where each represents a vector (i.e., a gene representation of an individual), as the average cosine distance among all pairs in the dataset:

denotes the cosine distance between vectors and . A larger value of D indicates that the dataset is more dispersed in the d-dimensional space, suggesting greater variability or diversity among the vectors.

Specifically, this metric can be used to quantify the diversity of genotypes or phenotypes as follows. In the VAE-based evolutionary model, the D value can be computed from the two-dimensional genotype vectors of individuals (i.e., coordinates) in each generation to evaluate the genotypic diversity within the population. The phenotype diversity in each generation can be assessed by converting evolved songs into vectors using wav2vec 2.0 and then calculating the corresponding D value. In the TTA-based evolutionary model, both textual genotypes and song phenotypes of each generation can be represented as vectors using SentenceTransformer and wav2vec 2.0, and their D values can be computed to measure the genotypic and phenotypic diversity within the population.

4.2. Affinity

In addition, we define the affinity (A) between two datasets and as the average of the maximum cosine similarities between them, where each (e.g., a male vocalization gene representation) or (e.g., a female preference gene representation) is a vector:

is the cosine similarity between vectors and . A larger value of A indicates that the vectors in the two vector datasets are more closely aligned, suggesting stronger mutual affinity between them. We use this metric to determine how well females can select males that match their preferences, assuming vectors are male song genotypes and female preference genotypes. A higher affinity value indicates that the population contains males whose songs closely match female preferences, enabling more effective mate selection.

In both of our evolutionary models, we assume that females select males whose vocalizations are most similar to their own preferences. Under the influence of sexual selection, the evolutionary models might drive the coevolution of male traits and female preferences. By applying the two metrics to both genotypes and phenotypes in the population during evolution, we can effectively quantify the dynamics of coevolution in each model. In the evolutionary process, higher diversity in genotypes or phenotypes may indicate an exploratory evolutionary trend, with the population undergoing further divergence, potentially accompanied by the emergence of novel genes or songs. Conversely, higher affinity in genotypes or phenotypes reflects stronger perceptual matching, indicating the presence of tightly matched male–female pairs within the population for more effective sexual selection.

These two metrics were applied to quantitatively analyzing the overall evolutionary dynamics of male and female genotypes (or phenotypes) in experiments with both evolutionary models. Moreover, since the two evolutionary models differ fundamentally in how they represent genotypes and phenotypes and the number of experimental trials differs (100 for VAE vs. 6 for TTA), it is difficult to directly statistically compare the D or A values of genotypes and phenotypes between them to compare the evolutionary dynamics. Instead, we can assess the effects of the model types on genotype and phenotype evolution by examining how these metrics change over generations within each model. By projecting the genotypes and phenotypes of the VAE-based evolutionary model and the TTA-based evolutionary model into a two-dimensional vector space and analyzing the temporal trends in their D values, we can evaluate whether and to what extent each model promotes diversity in genotypes or phenotypes.

4.3. BirdNET Classification as a Virtual Bird Song Expert

As another approach, we used BirdNET (https://github.com/kahst/BirdNET-Analyzer (accessed on 1 September 2025)), a deep-learning-based system for automatic bird sound recognition widely applied in ecological research [24]. This network enables us to assess the species identity of generated songs by comparing them against a trained database of known bird species. When we input the wave file of a bird song, we obtain the probability distribution of the classification of the species in the wave file. We use this distribution as a proxy of the classification of songs by a virtual bird song expert and focus on the frequently classified species and compare their properties with those of the BAWF.

5. Results

5.1. An Evolutionary Experiment Based on the VAE Model

For the VAE evolution model, the parameter settings were as follows: , , , , , , , and . The same parameter settings were used to conduct 100 independent evolutionary trials. Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate the visualization and a quantitative analysis of the evolutionary dynamics of male vocalization genes and female preference genes in the experiments with the VAE-based evolutionary model.

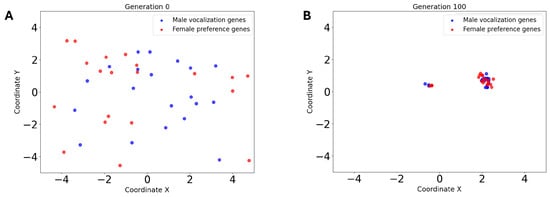

Figure 7.

The evolution of male vocalization genes and female preference genes in the VAE-based evolutionary model. (A) Distribution of male vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) in the initial population in a trial. (B) Distribution of male vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) in the final population in the same trial.

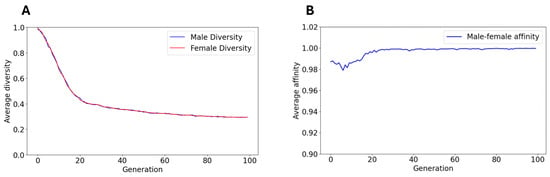

Figure 8.

The evolutionary dynamics of male vocalization genes and female preference genes in the VAE-based evolutionary model. (A) Average diversity changes in male vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) throughout the evolutionary process over 100 trials. (B) Average affinity changes between male vocalization genes and female preference genes throughout the evolutionary process across 100 trials.

Figure 7A shows the distribution of male vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) in the 2D latent space at initial generation in a typical experimental trial. Both genes were randomly distributed in the space. Figure 7B shows the distribution at the final generation. The male vocalization genes and female preference genes clustered into two groups, and both converged to similar positions. These results suggest that the male vocalization genes and female preference genes became aligned in the sexual selection process.

Due to the probabilistic nature of the initial population and the evolution process, we extracted the overall tendency of the evolutionary dynamics of the population by aggregating the results from 100 experimental trials. We computed the diversity of male vocalization genes and female preference genes, as well as the affinity between them at each generation within every independent evolutionary trial. These results were then averaged across trials to quantify the overall evolutionary dynamics of the population.

Figure 8A shows the average diversity changes in male vocalization genes and female preference genes in the evolution process over 100 trials. Both male vocalization genes and female preference genes showed similar patterns of diversity changes throughout evolution. Starting from high initial diversity (around 1.0), both gene types rapidly declined to approximately 0.4 by the 20th generation, indicating strong convergence within the population. Figure 8B shows the average affinity changes between male vocalization genes and female preference genes in the evolution process over 100 trials. The affinity remained consistently high throughout evolution, starting from 0.99, briefly declining to 0.98, and then increasing to nearly 1.0 by the 20th generation. The brief decline in affinity to 0.98 reflects the initial disruption of the mate selection efficiency as sexual selection toward multiple target phenotypes begins to operate. Then, it was followed by rapid improvements attributed to a runaway process [30], in which female selection reinforces the propagation of preferred male traits in the population, leading to mutual adaptation between male vocalization genes and female preference genes and their coevolution toward several specific regions of the latent space. The average diversity converged to approximately 0.3, indicating that the population did not converge completely to a single genotype but rather formed multiple clusters, consistent with Higashi et al.’s prediction of sympatric speciation [17], as observed in Figure 7B.

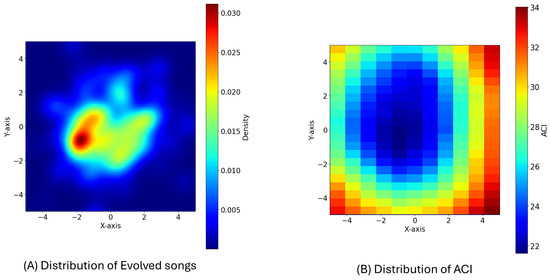

We also investigated the pattern of evolved songs using the Acoustic Complexity Index (ACI) [31], a measure commonly used in ecoacoustics to detect biological sounds in field recordings. The ACI measures temporal changes in the sound intensity across frequency bins. High ACI values are complex or noisy temporal variations in the sound intensity within frequency bins, while low ACI values represent more consistent sound intensity patterns over time. Figure 9A shows the frequency distribution of the male vocalization genes at the final generation in 100 trials, using a kernel density estimation (KDE). The vocalization gene distribution of the final generation shows that the selected songs are generally distributed over a narrow area around the origin, with a bias toward negative x values (−2) compared to the initial generation. Figure 9B shows the distribution of the ACI for the corresponding spectrograms in the latent space (Figure 3). As illustrated by the ACI distribution, the evolutionary process tended to avoid regions of the latent space with high ACI values due to high noise and instead favored regions of songs with a lower ACI, characterized by low noise and relatively clear acoustic structures. This suggests that the properties of phenotypes, such as the clarity of vocalizations, which cannot be represented in simple and abstract models, may drive the sexual selection of secondary character traits, like bird songs.

Figure 9.

(A) The frequency distribution of male vocalization genes at the final generation across 100 trials; (B) distribution of the Acoustic Complexity Index (ACI) of spectrograms in the latent space (Figure 3). In both figures, red indicates higher values, and blue indicates lower values.

In sum, the VAE evolutionary model exhibits inherent selection pressure favoring songs near the latent space’s origin, where the training data’s characteristics are most accurately represented. Importantly, the acoustic features of the generated songs significantly influence the evolutionary trajectories, yielding clustering of the evolved population. A comparative analysis by Suzuki et al. [16] using coordinate-based rather than spectrogram-based fitness showed even stronger convergence to the origin, demonstrating that the complexity and acoustic properties of the vocalizations themselves shape the evolutionary dynamics and can partially counteract homogenization pressures.

5.2. The Evolutionary Experiment Based on the Text-to-Audio Model

We then conducted experiments using the proposed TTA-based evolution model. The parameter settings were as follows: , , , , . The same parameter settings were used to conduct six independent evolutionary trials. We used different parameter settings from those in the VAE-based model, particularly fewer trials, due to the significantly higher computational cost of the TTA-based model. While this precludes a direct quantitative comparison between the two approaches, we focus on a qualitative analysis of the evolutionary dynamics, examining the scenario of evolved textual genotypes and their corresponding generated songs.

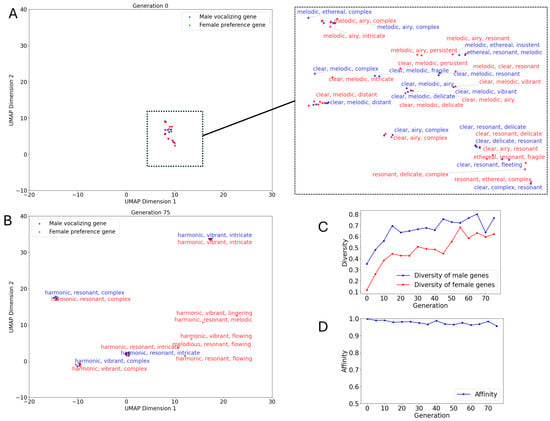

We investigate the evolutionary dynamics of genotypes and phenotypes in the results of the TTA-based evolution model. Both male vocalization genes and female preference genes, represented as texts, were transformed into 2D vectors using the SentenceTransformer (https://pypi.org/project/sentence-transformers (accessed on 1 September 2025)) package in Python (version 3.10) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [32]. As for phenotypes, we used the wav2vec 2.0 model [33] and UMAP [32] to transform the evolved male songs and female songs into the 2D vectors. Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the visualization and quantitative analysis of the evolved genes and evolved songs.

Figure 10.

The evolution dynamics of population genotypes based on the text-to-audio evolutionary model. (A,B) The distribution of male vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) in the initial and final populations within the latent space. (C) Average diversity changes in males vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) throughout the evolutionary process over 6 trials. (D) Average affinity changes between male vocalization genes and female preference genes throughout the evolutionary process across 6 trials.

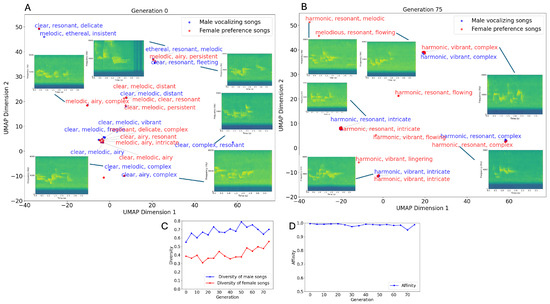

Figure 11.

The evolution dynamics of population phenotypes based on the text-to-audio evolutionary model. (A, B) The distribution of male evolved songs (blue) and female evolved songs (red) in the initial and final populations within the latent space. (C) Average diversity changes in males songs (blue) or female songs (red) throughout the evolutionary process over 6 trials. (D) Average affinity changes between male songs and female songs throughout the evolutionary process across 6 trials.

Figure 10A,B illustrate the distribution of male vocalization genes (blue) and female preference genes (red) in the 2D latent space for the initial and final populations. In the initial population, male vocalization genes and female preference genes are concentrated within a narrow region of the latent space. This suggests that the genes in the initial population were constructed from a limited set of descriptive words related to song properties (e.g., “clear”, “melodic”, “complex”).

However, the complex mapping from texts to songs based on the TTA model brought about phenotypic diversification. Figure 11A,B illustrate the distribution of male evolved songs and female evolved songs at the initial and final populations in the same experimental trial as that in Figure 10A,B. In the initial population, male and female songs were scattered across the latent space, in contrast to the narrowly concentrated distribution observed in the genotypes. This suggests that phenotypes encoded by textual genotypes generated inherent diversity in the latent space. Nevertheless, some similar acoustic patterns marked by textual genotypes were still observed in the phenotypic distribution. For example, songs encoded by the descriptors “melodic, airy, complex” and “clear, complex, resonant” shared low-frequency characteristics.

Considering the variability in the initial textual genes and songs of populations across different experimental trials, it was necessary to quantify the general evolutionary dynamics in the TTA-based evolution model using the results from multiple independent experiments. We analyzed the average diversity changes in male vocalization genes, female preference genes, male songs, and female songs, as well as the average affinity between male vocalization and female preference genes and between male and female songs, across six experimental trials, as shown in Figure 10C,D and Figure 11C,D.

Both the genetic and phenotypic diversity increased throughout evolution (Figure 10C and Figure 11C). The diversity of male vocalization genes and female preference genes gradually increased as evolution progressed, driven by LLM-based mutations that continuously introduced novel genetic variants into the population. Meanwhile, the affinity between male vocalization genes and female preference genes remained consistently high throughout the evolutionary process (Figure 10D), indicating that sexual selection pressure maintained the affinity (almost 1.0) between male songs and female preferences despite increasing the diversity. Similarly, the average diversity of evolved songs exhibited an increasing pattern throughout the evolutionary process while maintaining high affinity between male and female songs (Figure 11D). Notably, the phenotypic diversity exceeded the genetic diversity from the initial populations, demonstrating that the TTA model enhanced diversification through the complex text-to-audio conversion process, which inherently generated additional phenotypic variation beyond what was encoded in the textual genotypes alone.

This evolution process brought about high diversity in both genes and songs at the final generation, as shown in Figure 10B and Figure 11B. The male vocalization genes and female preference genes expanded their distribution range in the latent space and formed several distinct clusters. Meanwhile, within each cluster (e.g., the “harmonic, resonant, complex” cluster and the “harmonic, vibrant, complex” cluster), male vocalization genes and female preference genes exhibited a pronounced tendency to converge. This implies that as evolution progresses, mutations introduced by the LLM continually introduce novel gene components (e.g., “flowing” or “harmonic”) into the population, thereby expanding the distribution range of evolved genes in the latent space.

Male and female songs also formed several clusters and showed convergence in the latent space, matching the pattern seen in the evolved genotypes (Figure 10A,B). We also found that some vocalization patterns from the initial population reappeared in specific phenotype clusters. For example, songs encoded by “harmonic, vibrant, complex” showed low-frequency features. This suggests that although sexual selection drives male and female songs to become more similar, facilitating the spread of certain vocal patterns within the population, the complex relationships between genotype and phenotype in the TTA model lead to further diversification of the evolved songs. However, how this complex relationship promotes song diversification remains to be investigated further—for example, whether the sentiment characteristics of textual genotypes [34] can influence the sentiment attributes of the generated songs.

In summary, the TTA-based evolutionary model exhibited fundamentally different dynamics compared to those in the VAE-based model. Quantitative analyses showed that across different independent evolutionary trials, the diversity index (D) of male vocalization genes and female preference genes gradually increased over generations, and a similar increasing trend was observed for male and female songs (Figure 10C and Figure 11C). Despite the increase in diversity, the affinity index (A) remained consistently high (close to 1.0) throughout the evolutionary process (Figure 10D and Figure 11D). This pattern contrasts with that in the VAE-based model, where the affinity remained consistently high while the diversity decreased over generations. Therefore, the TTA-based evolutionary model promoted genetic and phenotypic diversification through LLM-based evolutionary processes. The emergence of multiple co-adapted clusters, each representing independent vocalization-preference relationships, indicates that the TTA model can capture both the diversifying effects of novel mutations and the stabilizing effects of sexual selection. This dual capacity makes the TTA-based approach particularly promising for modeling realistic evolutionary scenarios where diversity and coordination must coexist.

5.3. Species-Specific Acoustic Characteristics in Evolved Songs

We observed that as evolution progressed, the genotypes changed, yet evolved songs retained their structural similarity (e.g., the “clear, melodic, complex” song in Figure 11A and the “harmonic, vibrant, intricate” song in Figure 11B), suggesting that evolved songs consistently retained core acoustic characteristics.

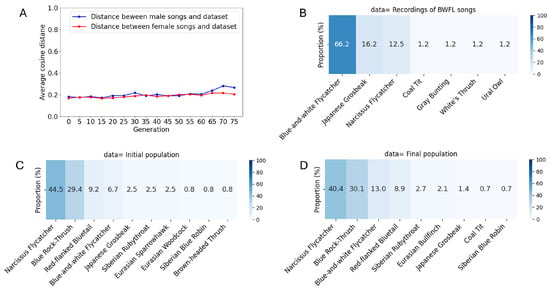

To investigate this pattern, we calculated the cosine distance between male and female songs and the original BAWF songs from the training dataset in each generation. Figure 12A shows that throughout the evolutionary process, the cosine distances remained consistently low at around 0.2 with a slight increasing trend, indicating that the evolved songs maintained the characteristics of the original BAWF songs, and the songs generated by the TTA-based evolutionary model could be regarded as realistic vocalizations of the BAWF with a higher similarity.

Figure 12.

Analysis of distances between evolved songs and real recordings, and species classification patterns. (A) Average cosine distance of male (blue) and female (red) songs to the original songs. (B) The classification results for the original BAWF recordings. (C) The classification results fpr the evolved songs in the initial populations over 6 trials. (D) The classification results for the evolved songs in the final populations over 6 trials.

We classified the original recordings and evolved songs from the initial and final populations using BirdNET to evaluate whether the evolved songs retained species-specific acoustic signatures. BirdNET occasionally failed to process some inputs; for each successfully processed audio file, we selected the highest-confidence classification from multiple results and calculated ratios from 80 of 102 (100 dataset + 2 additional ones) recordings for original recordings and 146 of 180 generated songs for evolved songs of initial and final population. In Figure 12B, most of the original recordings were correctly classified as belonging to the BAWF, while some were identified as belonging to the Japanese Grosbeak (Eophona personata) and the Narcissus Flycatcher (Ficedula narcissina), likely due to acoustic similarities in the frequency ranges and temporal structures. In contrast, Figure 12C,D show that the initial and evolved songs were classified as belonging to a mixture of species, with the Narcissus Flycatcher and the Blue Rock Thrush (Monticola solitarius) being dominant, while BAWF identification remained relatively low. This is plausible since these species’ songs are acoustically similar to those of the BAWF and sometimes misidentified by birders. It should be noted that the particular individual BAWF recorded for our dataset exhibited songs that somewhat resembled those of the Narcissus Flycatcher, likely due to vocal learning from this heterospecific species. Therefore, this suggests that the TTA model preserved the natural vocalization patterns within related species with similar song properties despite introducing variation. Indeed, the Blue-and-white Flycatcher (BAWF), the Narcissus Flycatcher (Ficedula narcissina), and the Blue Rock Thrush (Monticola solitarius) are all muscicapid species, which supports the model’s capacity to generate vocalizations of related taxa. The BAWF and the Narcissus Flycatcher are classified as having “easily confused songs” [35], while the Blue Rock Thrush produces vocalizations described as “beautiful songs reminiscent of the Blue-and-white Flycatcher’s warbling” [36]. These acoustic convergences indicate that our fine-tuned TTA model can synthesize novel vocalizations for acoustically similar species within the family Muscicapidae.

By comparing the classification results of the original recordings (Figure 12B) and evolved songs (Figure 12C,D), we also have reason to believe that the TTA model fosters the creation of novel bird songs: the original recordings were predominantly identified as the BAWF, whereas the evolved songs were classified into a broader range of species that have similar acoustic properties, with the Narcissus Flycatcher and the Blue Rock Thrush being dominant. This indicates that the songs generated by the model not only preserved species-specific natural vocalization patterns but also introduced novel acoustic variants. Such novel songs played an important role in driving phenotypic divergence in our TTA-based evolutionary model. According to the sexual selection model of Higashi et al. [17], when there is no strong directional selection pressure, mutual variations in male traits and female preferences can trigger a runaway process through positive feedback, ultimately leading to population divergence. In our framework, novel songs can be regarded as such extreme variations; thus, under sexual selection, they may promote the coevolution of female preferences and male songs, potentially contributing to population divergence.

Notably, Figure 12D shows an increased BAWF classification frequency in the final population, indicating that evolutionary dynamics may drive the evolved songs toward the natural vocalization patterns of the target species. This might be because the properties of the BAWF’s songs became more prevalent among the generated songs. These results demonstrate that the TTA-based evolution model promotes song diversity while preserving and refining species-specific natural vocalization patterns, supporting its potential for ecological applications.

In summary, by comparing the cosine distances of evolved songs with the original recordings, we quantitatively demonstrated their acoustic similarity, while the automatic classification results from BirdNET, used as a virtual expert, showed that the songs generated by the TTA-based evolutionary model preserved species-related natural vocalization patterns while introducing novel acoustic variants. Together, these results indicate that the songs generated by the evolutionary model can be regarded as realistic vocalizations with potential applications in ecological systems.

6. Conclusions

We proposed a novel agent-based evolutionary model for animal vocalizations based on text-to-audio (TTA) models, extending previous VAE-based approaches. We applied both evolutionary models to the Blue-and-white Flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana)’s songs and compared their evolutionary dynamics under sexual selection.

Both models successfully generated population clustering through coevolutionary processes but with markedly different scales of differentiation. The VAE-based model drove rapid convergence into distinct clusters, demonstrating sexual selection dynamics consistent with Higashi et al.’s sympatric speciation predictions. However, this differentiation was limited to a narrow region near the latent space’s origin, with the diversity rapidly declining from the initial random state and constraining evolved vocalizations to well-reconstructed patterns from the training data.

In contrast, the TTA-based model achieved extensive differentiation across a broader phenotypic space. LLM-based mutations continuously introduced novel acoustic features, enabling sustained diversification (increasing diversity throughout evolution) while maintaining the clustering dynamics. The model produced multiple co-adapted vocalization-preference clusters distributed across the wider semantic space, maintaining high affinity throughout evolution and demonstrating successful runaway sexual selection with enhanced exploratory potential.

Species-specific acoustic preservation was validated for the TTA-based model through an automated classification analysis, which revealed that evolved songs maintained patterns similar to those in related flycatcher species and increasingly converged toward the natural characteristics of the BAWF during evolution. While the VAE model likely preserved some species-specific features through the training constraints, the TTA approach demonstrated a superior capacity for large-scale differentiation while maintaining ecological relevance.

This study demonstrates the potential of integrating large language models and text-to-audio models into agent-based evolutionary modeling for animal communication research. The TTA-based approach generates biologically plausible yet novel vocalizations across broader phenotypic ranges than previous methods, offering new avenues for understanding evolutionary dynamics in natural communication systems. Our very preliminary pilot experiment provides initial evidence of potential ecological relevance: evolved songs classified as belonging to the BAWF elicited approaching and singing behaviors from wild individuals in a forest environment, while white noise control stimuli did not. The positive responses to evolved songs are consistent with previous findings [16]. Beyond these preliminary observations, this research establishes a methodological framework that bridges computational modeling and biological reality. The ability to generate diverse, species-appropriate vocalizations through text-based genetic representations opens new possibilities for testing evolutionary hypotheses, exploring acoustic communication mechanisms, and developing tools for ecological research, regardless of specific behavioral outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.Z., R.S.; methodology: H.Z., R.S.; software: H.Z., R.S.; validation: H.Z.; formal analysis: H.Z., R.S., T.A.; investigation: H.Z., R.S.; resources: H.Z., R.S.; data curation: H.Z., R.S.; writing—original draft preparation: H.Z., R.S.; writing—review and editing: H.Z., R.S., T.A.; visualization: H.Z., R.S.; supervision, R.S., T.A.; project administration: H.Z., R.S.; funding acquisition: R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI 24K15103 and JST SPRING JPMJSP2125.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental research procedures were approved by the Nagoya University Animal Care and Use Committee (ID: I240001-001 and I250001-001).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All codes and data used in this study are publicly available at 10.6084/m9.figshare.30173386 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| TTA | Text-To-Audio |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| ACI | Acoustic Complexity Index |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

| BAWF | Blue-and-white Flycatcher |

References

- Bianchi, F.; Squazzoni, F. Agent-based models in sociology. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2015, 7, 284–306. [Google Scholar]

- Fulker, Z.; Forber, P.; Smead, R.; Riedl, C. Spontaneous emergence of groups and signaling diversity in dynamic networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2210.17309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.; Dragićević, S.; White, R. Model testing and assessment: Perspectives from a swarm intelligence, agent-based model of forest insect infestations. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 39, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Brinkman, B.A.W. Evolution of innate behavioral strategies through competitive population dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, D. Computational bioacoustics with deep learning: A review and roadmap. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Ogunfunmi, T. An overview of variational autoencoders for source separation, finance, and bio-signal applications. Entropy 2021, 24, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guei, A.C.; Christin, S.; Lecomte, N.; Hervet, É. ECOGEN: Bird sounds generation using deep learning. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2024, 15, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguš, G.; Gero, S. Approaching an unknown communication system by latent space exploration and causal inference. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.10931. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuk, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Polyak, A.; Singer, U.; Défossez, A.; Copet, J.; Parikh, D.; Taigman, Y.; Adi, Y. Audiogen: Textually guided audio generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.15352. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Z.; Parker, J.D.; Carr, C.; Zukowski, Z.; Taylor, J.; Pons, J. Stable Audio Open. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.14358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, S.-H.; Wu, J.; Feng, L.; Tan, K.C. Evolutionary computation in the era of large language model: Survey and roadmap. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2024, 29, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Arita, T. An evolutionary model of personality traits related to cooperative behavior using a large language model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, C.; Banarse, D.; Michalewski, H.; Osindero, S.; Rocktäschel, T. Promptbreeder: Self-referential self-improvement via prompt evolution. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16797. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, R.; Sumitani, S.; Ikeda, C.; Arita, T. A Modeling and Experimental Framework for Understanding Evolutionary and Ecological Roles of Acoustic Behavior Using a Generative Model. In Proceedings of the ALIFE 2022 Conference, Trento, Italy, 18–22 July 2022; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, R.; Harlow, Z.; Nakadai, K.; Arita, T. Toward integrating evolutionary models and field experiments on avian vocalization using trait representations based on generative models. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Vocal Interactivity In-and-Between Humans, Animals and Robots, Kos, Greece, 6 September 2024; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi, M.; Takimoto, G.; Yamamura, N. Sympatric speciation by sexual selection. Nature 1999, 402, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarzadegan, N.; Majumdar, A.; Williams, R.; Hosseinichimeh, N. Generative agent-based modeling: An introduction and tutorial. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2024, 40, e1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzing, D.; Starner, T.; Google DeepMind Team. DolphinGemma: How Google AI Is Helping Decode Dolphin Communication. Google AI Blog. 14 April 2025. Available online: https://blog.google/technology/ai/dolphingemma/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Robinson, D.; Hagiwara, M.; Hoffman, B.; Cusimano, M. NatureLM-audio: An Audio-Language Foundation Model for Bioacoustics. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.07186. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, R.; Matsubayashi, S.; Nakadai, K.; Okuno, H.G. HARKBird: Exploring acoustic interactions in bird communities using a microphone array. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2017, 27, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Kamath, A.; Ferret, J.; Pathak, S.; Vieillard, N.; Merhej, R.; Perrin, S.; Matejovicova, T.; Ramé, A.; Rivière, M.; et al. Gemma 3 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.19786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainburg, T.; Thielk, M.; Gentner, T.Q. Latent space visualization, characterization, and generation of diverse vocal communication signals. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S.; Wood, C.M.; Eibl, M.; Klinck, H. BirdNET: A deep learning solution for avian diversity monitoring. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 61, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, P. A comparative approach to vocal learning: Song development in white-crowned sparrows. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1970, 71, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatcroft, D.; Qvarnström, A. Genetic divergence of early song discrimination between two young songbird species. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 0192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, P.K.; Beecher, M.D.; Horning, C.L.; Campbell, S.E. Recognition of individual neighbors by song in the Song Sparrow, a species with song repertoires. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1991, 29, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, W.A.; Nowicki, S. The Evolution of Animal Communication: Reliability and Deception in Signaling Systems; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eshelman, L.J.; Schaffer, J.D. Real-coded genetic algorithms and interval-schemata. In Foundations of Genetic Algorithms; Whitley, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; Volume 2, pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti, N.; Farina, A.; Morri, D. A new methodology to infer the singing activity of an avian community: The Acoustic Complexity Index (ACI). Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, Y.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 12449–12460. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.-H.; Im, S.-K. Sentiment Analysis by Using Naïve-Bayes Classifier with Stacked CARU. Electron. Lett. 2022, 58, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical College. Detailed Bird Vocalization Guide. J-Eco Bird Song Encyclopedia. 2025. Available online: https://www.caretech.ac.jp/topic/bird/birdsong2.html (accessed on 27 August 2025). (In Japanese).

- Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. Why Does the Blue Rock Thrush Expand into Inland Areas. Available online: https://www.yamashina.or.jp/hp/yomimono/isohiyodori_mrkawachi.html (accessed on 27 August 2025). (In Japanese).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).