Learning-Aided Adaptive Robust Control for Spiral Trajectory Tracking of an Underactuated AUV in Net-Cage Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Vehicle Model and Control Objective

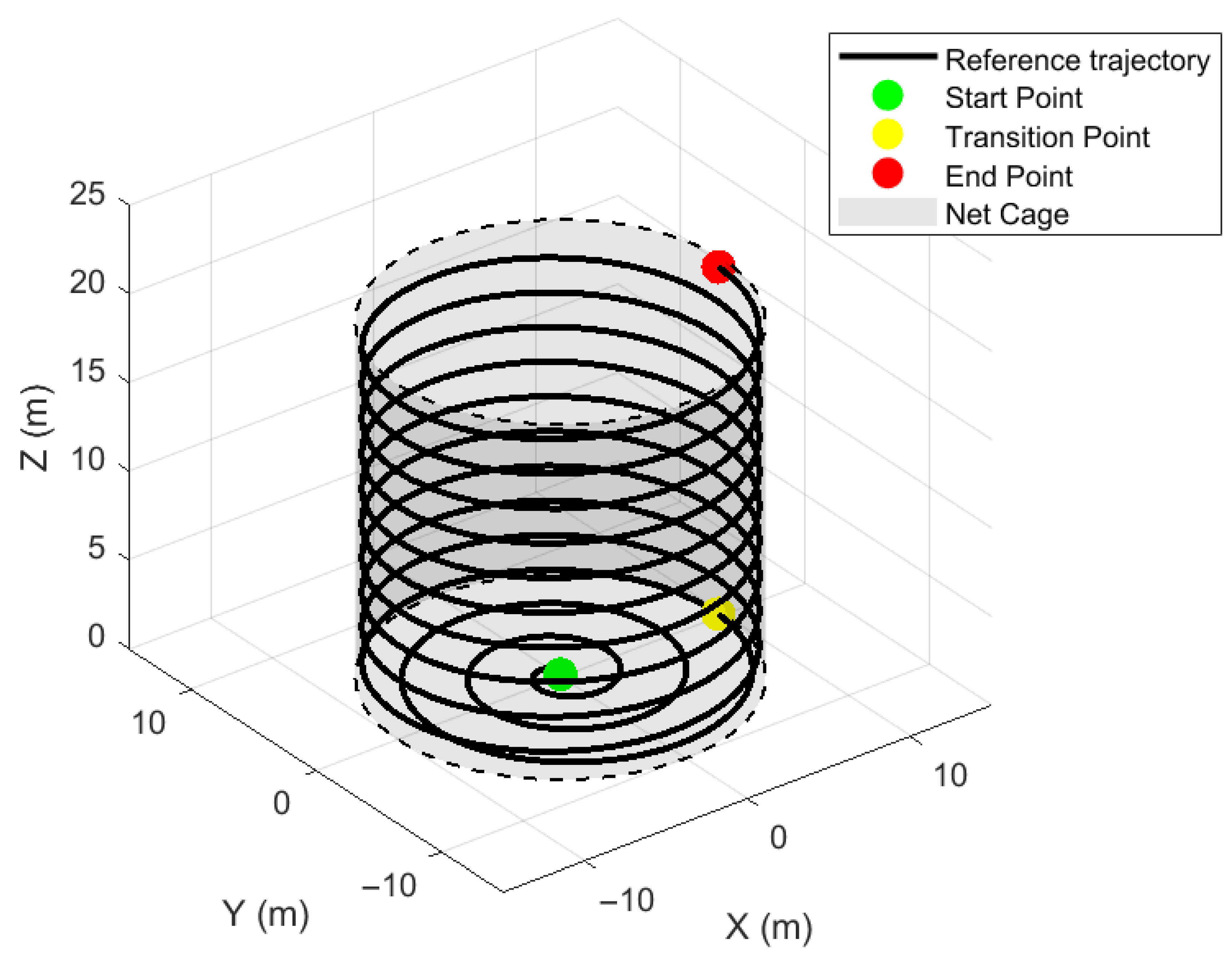

2.1. Underactuated AUV Model

2.2. Control Objective

3. Controller Design

3.1. Kinematics Controller Design

3.1.1. Iterative Learning Feedforward Compensation

3.1.2. Error Dynamics Model for Trajectory Tracking

3.1.3. Kinematic Control Law Based on FFC-LOS

3.2. Dynamic Controller Design

3.2.1. Online Parameter Identification via Projection and Rate-Limited RLS

3.2.2. Adaptive Robust Control Law

3.3. Closed-Loop Stability Analysis

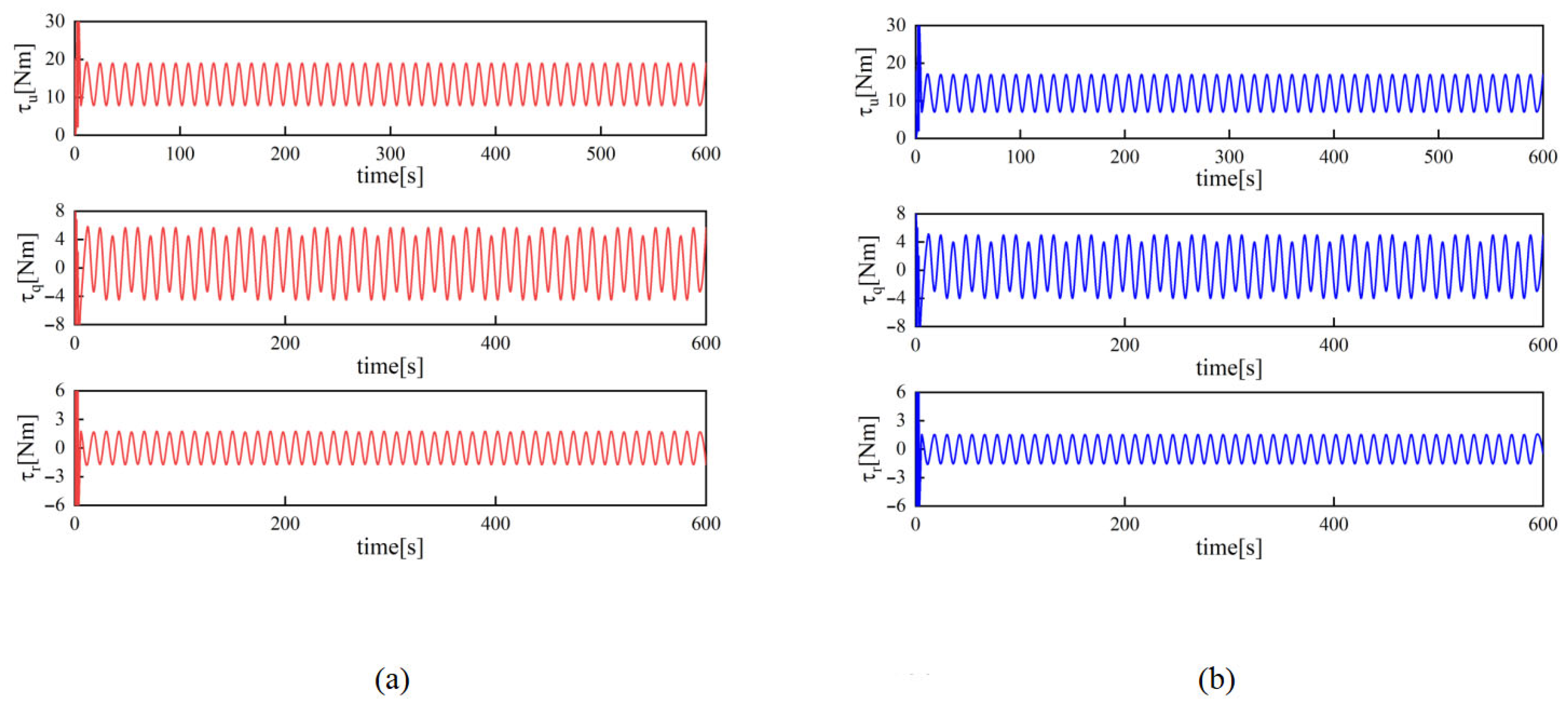

4. Simulation Setup and Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUV | Autonomous Underwater Vehicle |

| LARC | Learning-Aided Adaptive Robust Control |

| ARC | Adaptive Robust Control |

| ILC | Iterative Learning Control |

| RLS | Recursive Least-Squares |

| LOS | Line-Of-Sight |

| FFC-LOS | Feedforward-Compensated Look-Ahead Guidance |

| RC | Robust Controller |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| UUB | Uniform Ultimate Boundedness |

| ISS | Input-to-State Stability |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| DOF | Degree(s) of Freedom |

| Q-filter | Low-Pass Q-Filter |

References

- Li, D.; Du, L. AUV Trajectory Tracking Models and Control Strategies: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawhar, I.; Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J.; Zhang, S. An Architecture for Using Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Wireless Sensor Networks for Underwater Pipeline Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 15, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qiao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, R.; An, D.; Wei, Y. Three-Dimensional Path-Following Control System for Net-Cage Inspection Using Bionic Robotic Fish. Inf. Process. Agric. 2022, 9, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degorre, L.; Fossen, T.I.; Chocron, O.; Delaleau, E. A Model-Based Kinematic Guidance Method for Control of Underactuated Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 152, 106068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, M.; Li, D. A Double-Loop Control Framework for AUV Trajectory Tracking under Model Parameters Uncertainties and Time-Varying Currents. Ocean Eng. 2022, 265, 112566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalving, B. The NDRE-AUV Flight Control System. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 1994, 19, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmokadem, T.; Zribi, M.; Youcef-Toumi, K. Terminal Sliding Mode Control for the Trajectory Tracking of Underactuated Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2017, 129, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, M.; Qiao, L. Dynamical Sliding Mode Control for the Trajectory Tracking of Underactuated Unmanned Underwater Vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2015, 105, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Yan, Z.; Yang, Z. Trajectory Tracking Control of an Underactuated AUV Based on Backstepping Sliding Mode with State Prediction. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 181983–181993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadegan, F.; Shojaei, K.; Sheikholeslam, F.; Chatraei, A. A Novel Approach to 6-DOF Adaptive Trajectory Tracking Control of an AUV in the Presence of Parameter Uncertainties. Ocean Eng. 2015, 107, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.; Torres, J.; Creuze, V.; Chemori, A. Trajectory Tracking for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle: An Adaptive Approach. Ocean Eng. 2019, 172, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, L.; Jouvencel, B. Robust Nonlinear Path-Following Control of an AUV. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2008, 33, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Subudhi, B. Design of a Steering Control Law for an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Using Nonlinear H-Infinity State Feedback Technique. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 90, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Teng, Y.; Wei, S.; Xiong, H.; Ren, H. Robust H-Infinity Control of an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle with Riccati-Equation Solution Interpolation. Ocean Eng. 2018, 156, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Meléndez-Useros, M.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Boada, B.; Boada, M. Motion Planning and Robust Output-Feedback Trajectory Tracking Control for Multiple Intelligent and Connected Vehicles in Unsignalized Intersections. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Zhang, D.; Li, C.; Gong, Z.; Venkatesan, R.; Jiang, F. Localization and Data Collection in AUV-Aided Underwater Sensor Networks: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Netw. 2019, 33, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Cheng, B. Disturbance Suppression and Neural-Network Compensation Based Trajectory Tracking of an Underactuated AUV. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Ma, G. Adaptive Optimal Trajectory Tracking Control of AUVs Based on Reinforcement Learning. ISA Trans. 2023, 137, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Tomizuka, M. Adaptive Robust Control of SISO Nonlinear Systems in a Semi-Strict Feedback Form. Automatica 1997, 33, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yao, B.; Wang, Q. Integrated Direct/Indirect Adaptive Robust Contouring Control of a Biaxial Gantry with Accurate Parameter Estimations. Automatica 2010, 46, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Yao, B. Indirect Adaptive Robust Control of Hydraulic Manipulators with Accurate Parameter Estimates. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2011, 19, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.S.; Chen, Y.; Moore, K.L. Iterative Learning Control: Brief Survey and Categorization. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2007, 37, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, S.S.; Shen, D.; Orabi, M.; Kors, D.; Jaafar, R.H. Iterative Learning Control: Practical Implementation and Automation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 1858–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, D.A.; Tharayil, M.; Alleyne, A.G. A Survey of Iterative Learning Control. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2006, 26, 96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, S. Model–Data-Driven Learning Adaptive Robust Control of Precision Mechatronic Motion Systems with Comparative Experiments. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 78286–78296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhou, R.; Guo, Q.; Ma, L.; Hu, C.; Luo, J. Spatial Trajectory Tracking of Underactuated Autonomous Underwater Vehicles by Model–Data–Driven Learning Adaptive Robust Control. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Application Context | Adaptability to Uncertainty | Handles Repetitive Tasks? | Data Requirements | Stability Guarantees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed LARC (This Work) | Net-Cage Spiral Inspection | High (RLS + Robust Term) | Yes (via ILC) | Model-based + past trial data | UUB |

| LARC (Guo et al. [26]) | General 3D Trajectory | High (RLS + Robust Term) | Yes (via ILC) | Model-based + past trial data | UUB |

| Helix Controller (Chen et al. [3]) | Net-Cage Helical Path | Low (Fixed Parameters) | Implicitly (path-specific) | Model-based | Not specified |

| RL-based Control [16] | General 3D Trajectory | High (Learned Policy) | Possible (with task framing) | Large interaction dataset | Probabilistic/none |

| SMC [7,8,9] | General 3D Trajectory | High (Robust to Bounds) | No | Model-based (sliding surface) | Asymptotic/UUB |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Main body length | 396 mm |

| Main body width | 300 mm |

| Main body height | 122 mm |

| Total weight | 4 kg |

| Total buoyancy | 39.2 N |

| Performance Indices | LARC | ARC | RC | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total MAE | 1.7408 | 2.6462 | 3.6197 | 4.8502 |

| Total MSE | 1.2619 | 2.8407 | 5.3929 | 9.4220 |

| MAE (xe) | 0.027663 | 0.05186 | 0.072081 | 0.094767 |

| MSE (xe) | 0.001164 | 0.004808 | 0.007609 | 0.010173 |

| MAE (ye) | 0.059487 | 0.144279 | 0.155064 | 0.247647 |

| MSE (ye) | 0.004993 | 0.029337 | 0.028299 | 0.070097 |

| MAE (ze) | 0.119767 | 0.195581 | 0.235349 | 0.296163 |

| MSE (ze) | 0.014677 | 0.03896 | 0.056167 | 0.08886 |

| MAE (ψe) | 0.940407 | 1.458872 | 1.966173 | 2.532558 |

| MSE (ψe) | 0.888218 | 2.134347 | 3.881607 | 6.432326 |

| MAE (θe) | 0.593488 | 0.795628 | 1.19107 | 1.67907 |

| MSE (θe) | 0.352837 | 0.633248 | 1.419246 | 2.820502 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Z.; Huang, D.; Yang, F.; He, H.; Liang, F.; Voitasyk, A. Learning-Aided Adaptive Robust Control for Spiral Trajectory Tracking of an Underactuated AUV in Net-Cage Environments. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10477. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910477

Zhu Z, Huang D, Yang F, He H, Liang F, Voitasyk A. Learning-Aided Adaptive Robust Control for Spiral Trajectory Tracking of an Underactuated AUV in Net-Cage Environments. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10477. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910477

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Zhiming, Dazhi Huang, Feifei Yang, Hongkun He, Fuyuan Liang, and Andrii Voitasyk. 2025. "Learning-Aided Adaptive Robust Control for Spiral Trajectory Tracking of an Underactuated AUV in Net-Cage Environments" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10477. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910477

APA StyleZhu, Z., Huang, D., Yang, F., He, H., Liang, F., & Voitasyk, A. (2025). Learning-Aided Adaptive Robust Control for Spiral Trajectory Tracking of an Underactuated AUV in Net-Cage Environments. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10477. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910477