Abstract

Background: The field of smart devices and physical activity is evolving rapidly, with a wide range of devices measuring a wide range of parameters. Scientific articles look at very different populations in terms of the impact of smart devices but do not take into account which characteristics of the devices are important for the group and which may influence the effectiveness of the device. In our study, we aimed to analyse articles about the impact of smart devices on physical activity and identify the characteristics of different target groups. Methods: Queries were run on two major databases (PubMed and Web of Science) between 2017 and 2024. Duplicates were filtered out, and according to a few main criteria, inappropriate studies were excluded so that 37 relevant articles were included in a more detailed analysis. Results: Four main target groups were identified: healthy individuals, people with chronic diseases, elderly people, and competitive athletes. We identified the essential attributes of smart devices by target groups. For the elderly, an easy-to-use application is needed. In the case of women, children, and elderly people, gamification can be used well, but for athletes, specific measurement tools and accuracy may have paramount importance. For most groups, regular text messages or notifications are important. Conclusions: The use of smart devices can have a positive impact on physical activity, but the context and target group must be taken into account to achieve effectiveness.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Stimulating physical activity is a very important part of improving health. When planning investments in programmes to promote physical activity, it is important to consider the factors that influence participation in sports. For example, gender may play a role in sporting habits [1]. However, when examining the development of sporting habits, it is important to highlight the role of adolescent influences such as parental attitudes, fitness, academic achievement, gender, and financial background [2,3]. In addition, the importance of housing conditions should be emphasised and has been highlighted in several studies [4,5].

Community support, facilitation of access, and participation in sports clubs can play a major role in improving sporting habits [6]. However, the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in 2019 had a major impact on community activities and could have had a significant impact on sporting habits, especially if they were community- or team-based [7]. One study has shown that coaching can have a positive impact on individuals’ attitudes towards sports during this period [8]. However, it should also be noted that the use of this method by individuals would require significant human resource capacity. To overcome this, Internet of Things (IoT) devices could be used to provide remote supervision in sports coaching [9,10].

The need to measure physical activity has existed for decades, but prior to the advent of wearable measurement devices, this was done using self-report questionnaires, which were not accurate [11,12,13,14]. The first wearable devices used to measure physical activity were mainly based on acceleration, measuring speed, duration, number of steps, and stride length, while more advanced devices categorised movements into categories such as sitting, standing, and walking [15,16,17]. These devices were usually attached to the limbs or waist and performed no function other than measuring physical activity [17]. The objective metrics they provide reduce the subjectivity inherent in survey methods and can be used in large groups [18,19]. Accelerometers can also be used in younger as well as older populations [20,21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, they can be used regardless of gender, even to detect sex differences [25,26]. Heart rate monitoring is valid enough to be used to create broad physical activity categories (e.g., very active, somewhat active, sedentary) but lacks the specificity needed to estimate physical activity in individuals [27].

As devices have evolved, physical activity meters have become more compact and convenient. The most commonly used devices are smartwatches, smart bracelets, and smartphones. Newer devices are capable of simultaneously measuring parameters such as exercise, activity intensity, respiratory rate, cardiac output (ECG), and body surface temperature [28]. Physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE) and different intensity profiles measured with such devices can be linked, providing a framework for the personalisation of wearable devices [29]. However, there is currently a need to improve the accuracy of measurements [30,31,32].

The use of wearable devices to monitor physical activity is predicted to grow more than five-fold in half a decade [29]. With the advances in wearable technology and the increasing demand for real-time analytical monitoring, devices will undergo significant development in the future through materials science, integrated circuit construction, manufacturing innovation, integrated circuit fabrication, and structural design [33]. By monitoring new parameters, measurements for physiological and health purposes will be possible, allowing professionals to make diagnoses and treatment decisions, thereby improving healthcare and supporting research [34]. The effectiveness of wearable smart devices can be improved not only by the development of new measurable parameters and accuracy but also by the inclusion of new technologies such as virtual reality or artificial intelligence analysis in the future [35,36].

1.2. Objectives

The use of smart devices can therefore be a good way to increase physical activity. However, as many factors influence sporting habits and thus the measures to promote sports, we need to carry out thorough research to prepare real interventions. A considerable amount of literature on the subject has become available, particularly in recent years. To establish the basis for further research, studies on smart devices and physical activity between 2017 and 2024 were collected by searching two major literature databases (PubMed, National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Maryland, USA and Web of Science, Clarivate, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, London, United Kingdom) and then organising the results through a suitable filtering process. This study can help in designing practical research and learning about previous research. This article aims to present the latest research on the use of smart devices during physical activity and identify the target groups, the impact of the usage of devices with different options, and the expectations of the populations studied. This can contribute to a better design of research on physical activity and smart devices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Searching Strategy, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We searched in PubMed and Web of Science databases. In both databases, we ran the search on 25 March 2024 using the following search terms and relationships: (physical activity) AND (smart device) AND ((income) OR (sex) OR (age) OR (education)). We surveyed articles published from 1 January 2017 to 25 March 2024.

We used the two databases mentioned above because they are considered as scientific databases in the field of health and social sciences, and we can be sure that the publications published there have been properly peer-reviewed. We have also considered using open databases such as Google Scholar, but these yield tens of thousands of results for the queries we have used. Furthermore, such databases usually do not have the option to export the results to Excel or other files, so manually recording a large number of hits would be time-consuming. Other databases could of course be included in similar searches.

The keywords in the query were selected based on several scientific articles. We aimed to examine factors that influence both physical activity [37,38,39] and smart device usage [40] patterns. Taking into account several articles, the four factors included in our research (income, gender, age, and education) were found to be appropriate when examined from both perspectives.

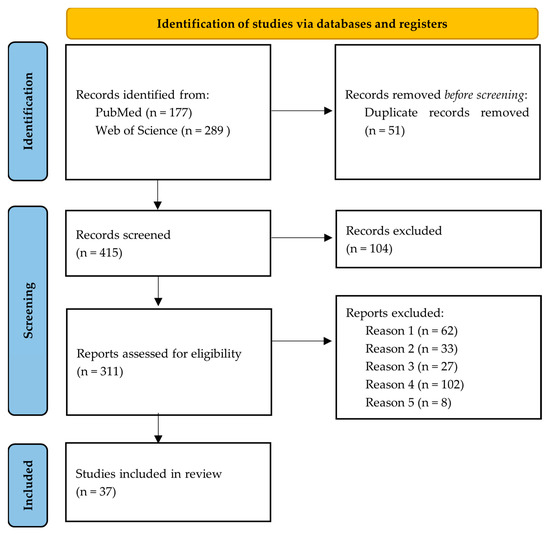

The results of both database queries were input into automatically generated Excel spreadsheets, and the duplicates were removed. We included articles and reviews and excluded article commentaries and proceeding papers. We also did not include studies that we could not access through our institution. The filtering and selection process and the number of articles per step are shown in Figure 1. Papers were filtered by title and abstract, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Article selection process based on PRISMA 2020 [41].

Table 1.

Criteria for inclusion of relevant literature (own ed.).

The main criterion was to examine the impact of smart devices on physical activity. This was mainly examined in terms of sociodemographic indicators and motivation. It was important that physical activity was mainly considered as a health determinant in the studies processed. On this basis, we excluded papers from the analysis that examined the topic from a technological point of view, e.g., architecture or accuracy of the equipment. In addition, exclusion criteria were also applied if the study did not examine the use of smart devices from a physical activity perspective or did not present smart devices (e.g., it examined the impact of social media). Those articles that did not contain concrete results or were non-professional, rather science-promoting, were not further analysed. We also excluded studies that did not include any IT tools at all. Based on the criteria, the articles that could be included and the articles that were filtered out were marked, and we did not work with the excluded articles. After this, the results were then analysed from a content perspective.

2.2. The Selection Process

The search returned 177 results for PubMed and 289 for Web of Science. In the selection process, 51 duplicates were deleted, and 104 articles were not available through our institution or were of the wrong type of scientific paper. After the exclusion criteria were applied, only 37 articles were further processed.

3. Results

3.1. Main Findings and Citation

Table 2 shows all the articles we have processed. The table shows each article’s serial number, reference number, author abbreviation, title, journal, and year of publication. We have also summarised the main findings of the studies. In the next three columns, we display the citation count of the article, the average of the journal’s impact factor, and the citation count of the article normalised by the journal’s impact factor. In the last column, we display the period for which the average impact factor was calculated.

Table 2.

Summary table of the articles included in the study, their main findings, and their average citations (own ed.).

3.2. Citation of the Articles

Articles with a normalised citation above 15 were considered strong. The most cited article is reference No. 37 with a value of 55.88, which is very high. This is followed by article No. 29, which has a much lower normalised citation count of 16.3. Article No. 32 is also considered outstanding with 15.84, as are article No. 20 with 15.44 and article No. 15 with 15.35.

In the normalised Impact Factor table (Table 2), the first six highlighted articles can be classified into two large groups. On the one hand, the articles deal with applications used by athletes (articles No. 29 and 32). Another group deals with mobile measuring devices used in everyday life, precisely with cases in which the measurement is evaluated by specialists (articles No. 37, 13, 15, 20). In both cases, there is no individual monitoring of the processes, but specialists are involved through communication.

3.3. Definition of Target Groups and Their Geographical Location

The studies have been processed from a content point of view. During the content processing of the articles, four main groupings were implemented according to the group targeted by the study of the impact of smart devices:

- Physical activity stimulation in a group of healthy people;

- Smart devices and physical activity of patients;

- Examining the impact of smart devices on the performance of competitive athletes;

- Smart devices for health protection among the elderly.

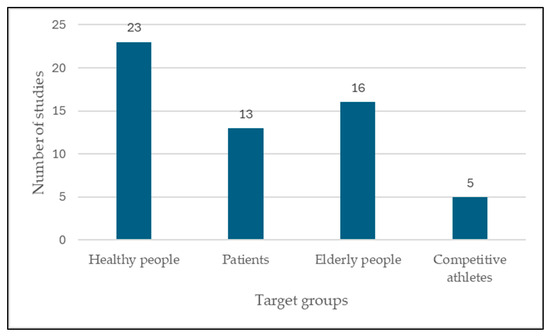

Figure 2 shows how many articles mentioned a target group. An article could have addressed more than one of the target groups we have identified, so adding up the number of articles gives a higher number than the number of articles included in the study. Most of the studies were carried out on healthy people (23 studies). After that, the most common target group was elderly people (16 papers), followed by patients (13 articles) and competitive athletes (5 studies).

Figure 2.

Number of studies by target groups mentioned.

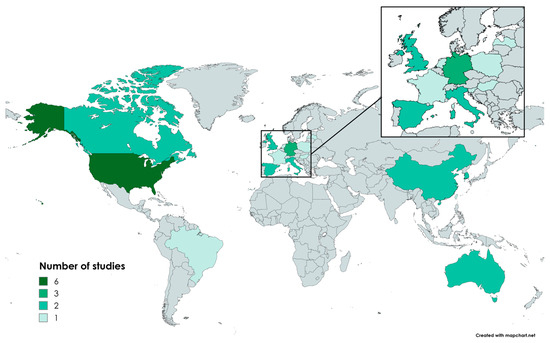

Looking at the studies, we found a very heterogeneous picture in terms of geographical location (Figure 3). In terms of country distribution, the country with the largest number of studies was the United States of America (six studies). Germany had three studies. Two studies per country were conducted in Australia, Spain, the Republic of Korea, Italy, Canada, the United Kingdom, and China. France, Taiwan, Hungary, Brazil, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia, and the Netherlands were mentioned in one article per country. In this case, some articles described research carried out in several countries, and some articles, mainly review articles, did not specify the country. The number of occurrences added together also does not match the number of articles included in the research. Our findings were therefore mostly related to the Americas and Europe.

Figure 3.

The geographical location of the target groups of the studies (own ed.).

3.4. Most Frequently Used Devices and Keywords

We also looked further at the type of smart device that each research study focused on (Table 3). This showed that most studies favoured smartwatches, smart bracelets, and smartphones. This may be because most people have access to these devices, so the research did not require additional investment, and users were more comfortable with their own devices. Smartwatches and smart bracelets are very similar in both appearance and function; although smart bracelets may have fewer features, they are also cheaper, so it is understandable that we found similar results in terms of their usage. Five studies did not specify the type of smart device used; these were generally review-type articles. Fifteen studies also used other devices such as accelerometers, GPS trackers, and smart scales. If we aggregate the number of devices, used the result is more than 37, which was the number of studies examined. This is because there were several cases where more than one wearable device was used in a study.

Table 3.

Distribution of studies by type of smart device studied (own ed.).

While analysing the scientific articles, we also observed the diversity of keywords, so we aggregated the keywords and their occurrence in the studies. A total of 161 keywords that occurred 208 times were identified. We then aggregated the keywords that differed only in conjugation. The most frequent keywords and their occurrence are shown in Table 4. It can be observed that the most frequent keyword, “Physical activity” (which we also used when preparing the queries), was used in the articles only 11 times. The second most common was the related word “Exercise”, followed by “Wearables”, “Wearable device”, “Smart device”, and “Activity trackers”, which also showed similarities. Finally, the terms “Mobile health” and “Digital health” were included in the table with three occurrences each. Other keywords, many of which are synonyms of these terms (e.g., mobile health—mHealth), occurred one or two times and are not marked in the table.

Table 4.

Most common keywords by number of occurrences (own ed.).

From these data, we can conclude that the use of keywords in scientific articles is very varied, often with only conjugation or phrasing differences, but this is a significant factor when we are running searches. The citability of an article can be greatly influenced by the chances of finding it when searching individual databases, so authors may want to assess the most commonly found keywords that fit the topic when creating an article and use them in the publication.

3.5. Target Groups’ Expectations, Expected Characteristics

Twenty-one of the scientific articles examined what each of the target groups expected from the tools or what features were important to them. These are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Target groups and their expectations of smart devices (own ed.).

Device features are also important because users’ needs and the supporting structure surrounding the device—often overlooked aspects—are crucial to long-term adoption [42].

The attitude of users influences the outcome of the use of the tools. Subjects who wore and checked their watches more often were more likely to change their exercise habits. So overall, it is not the smart device per se but the attitude towards the device and movement that is significant. These attitudes can be positively influenced by the design of a device that is convenient and comfortable for the user [43].

We have made additions concerning gamification. One article suggests that this method is particularly effective for older people and women, while another suggests that it is effective for children. Some of the studies analysed did not include any indication of the characteristics that users would prefer in relation to smart devices. This usually requires qualitative measurement, but most of the studies used quantitative data and did not use qualitative questionnaires or interviews, so it was not always possible to highlight these important characteristics in the articles.

4. Discussion

4.1. Stimulating Physical Activity among Healthy Individuals

In the target group of healthy people, the expectations of smart devices were as follows: Accuracy and ease of use were the most important, both mentioned in two articles. In addition, the number of measurable parameters, achievable goals, the possibility to compete with others, and rewards were also important, with one occurrence each. We also have to mention three subgroups in this respect, children, elderly, and women. In all three cases, gamification proved to be an even more useful feature. The reason for this, in our opinion, may be that gamification can provide them with the greatest experience and thus have a significant motivational effect (Table 5).

4.2. Smart Devices and Physical Activity of Patients

For the target group of patients, ease of use and the delivery of messages and notifications were the most important factors; the latter should be personalised where possible. The second most important parameter was therefore personalisation. The reason for this may be that not all devices are uniformly suited to the patients’ special conditions, as each patient’s condition is different, even if they have the same disease. However, it should also be mentioned that too much personalisation may be at the expense of ease of use, which was also an important factor in this target group. In addition, we can highlight accuracy, coaching, and competition as other important requirements (Table 5).

4.3. Improving the Performance of Athletes

For athletes, not too many expectations have been set. However, accuracy was clearly the most important, as it is more important for them to have accurate results from movement-related measuring tools so that they can draw the right conclusions about their performance. Data security is also an important factor for them, as this is sensitive business data for professional athletes. The possibility of forecasting is also an essential built-in element as it can help athletes to improve their results and plan a suitable training programme. It is important that the size of the device is small and the power consumption is low as this is the target group that would use these devices the most, and comfort and frequency of charging are essential for long-term use (Table 5).

4.4. Stimulating Activity among Elderly People

For senior people, ease of use and coaching were the main expectations for smart devices. We found two articles on each. These are not surprising findings, as external support and ease of use of devices can be of high importance for elderly people. Another important parameter for them is data security, and in addition, gamification emerged as a factor influencing usage. This may have a positive impact on motivation, as gamified devices can motivate older people to exercise regularly and use smart devices in this way (Table 5).

5. Conclusions

The existing literature predominantly examines the impact of smart devices on physical activity within the United States and Europe, highlighting substantial citation rates but also a wide variation in keyword usage. The most frequently used keywords were physical activity, exercise, wearables, wearable device, smart device, activity trackers, mobile health, and digital health. To enhance accessibility, we propose refining and standardising keyword selection.

Our review identifies various factors influencing smart device impact, including demographics such as age, gender, income, education, and marital status, suggesting tailored interventions based on target populations: healthy individuals, patients, competitive athletes, and the elderly.

Effective interventions hinge on intrinsic motivation, with healthy people benefiting from regular notifications or text messages, while the elderly require user-friendly interfaces and gamification strategies. Patients need notifications and easy-to-use, customisable devices. Athletes prioritise accurate data collection and predictive capabilities from smart devices. Additionally, heightened attention to data protection is warranted, given both user concerns and potential risks associated with data collection.

On the basis of normalised impact factor, the most cited articles focus on athletes and mobile measuring devices used in everyday life, in cases where the measurement is evaluated by professionals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.T. and I.B.; methodology, P.T. and K.T.; formal analysis, K.T. and P.T.; resources, K.T.; data curation, K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.; writing—review and editing, I.B., P.T. and K.T.; visualisation, K.T.; supervision, I.B. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blanco-García, C.; Acebes-Sánchez, J.; Rodriguez-Romo, G.; Mon-López, D. Resilience in Sports: Sport Type, Gender, Age and Sport Level Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, R.; Gravenor, M.B.; Rees, A.; Knox, G.; Hill, R.; A Rahman, M.; Jones, K.; Christian, D.; Baker, J.S.; Stratton, G.; et al. Factors associated with low fitness in adolescents—A mixed methods study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, K.M.; Longacre, M.R.; MacKenzie, T.; Titus, L.J.; Beach, M.L.; Rundle, A.G.; Dalton, M.A. High school sports programs differentially impact participation by sex. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pavón, D.; Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Chillón, P.; Castillo, R.; Artero, E.G.; Martinez-Gómez, D.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G.; Rey-López, J.P.; Gracia, L.A.; et al. Influence of socioeconomic factors on fitness and fatness in Spanish adolescents: The AVENA study. Pediatr. Obes. 2010, 5, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guszkowska, M.; Kuk, A.; Zagórska, A.; Skwarek, K. Self-esteem of physical education students: Sex differences and relationships with intelligence. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2016, 4, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Golle, K.; Granacher, U.; Hoffmann, M.; Wick, D.; Muehlbauer, T. Effect of living area and sports club participation on physical fitness in children: A 4 year longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, W.R. Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends for 2022. ACSM’S Health Fit. J. 2022, 26, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.; Rodda, K.; Begg, S.; O’Halloran, P.D.; Kingsley, M.I. Exercise and COVID-19: Reasons individuals sought coaching support to assist them to increase physical activity during COVID-19. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2021, 45, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Tong, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, S. The optimization of intelligent long-distance multimedia sports teaching system for IOT. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2018, 52, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Cloud storage–based personalized sports activity management in Internet plus O2O sports community. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2018, 30, e4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baecke, J.; Burema, J.; Frijters, J.E. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 36, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Hartman, T.J.; Leon, A.S. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E. Assessment of Physical Activity by Self-Report: Status, Limitations, and Future Directions. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71 (Suppl. 2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.L.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, R.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Global positioning system: A new opportunity in physical activity measurement. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scruggs, P.W.; Beveridge, S.K.; Eisenman, P.A.; Watson, D.L.; Shultz, B.B.; Ransdell, L.B. Quantifying Physical Activity via Pedometry in Elementary Physical Education. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-C.; Hsu, Y.-L.; Yang, C.-C.; Hsu, Y.-L. A Review of Accelerometry-Based Wearable Motion Detectors for Physical Activity Monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10, 7772–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Al-Awlaqi, M.A.A.H.; Li, M.; O’grady, M.; Gu, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, N. Wearable IoT enabled real-time health monitoring system. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Yu, W.; Han, X. Wearable heart rate monitoring intelligent sports bracelet based on Internet of things. Measurement 2020, 164, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Gill, K.; Ondrak, K.S.; McMurray, R.G. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddoch, C.J.; Mattocks, C.; Deere, K.; Saunders, J.; Kirkby, J.; Tilling, K.; Leary, S.D.; Blair, S.N.; Ness, A.R. Objective measurement of levels and patterns of physical activity. Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, J.J.; Penpraze, V.; Hislop, J.; Davies, G.; Grant, S.; Paton, J.Y. Objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviour: Review with new data. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, A.; Teng, D.; Chen, L.; Ko, S.B.; Shi, Y.; McCrosky, C.; Basran, J.; Del Bello-Hass, V. A wearable device for physical activity monitoring with built-in heart rate variability. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Beijing, China, 11–13 June 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allet, L.; Knols, R.H.; Shirato, K.; de Bruin, E.D. Wearable Systems for Monitoring Mobility-Related Activities in Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2010, 10, 9026–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consolvo, S.; Everitt, K.; Smith, I.; Landay, J.A. Design requirements for technologies that encourage physical activity. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Pate, R.R.; Sallis, J.F.; Freedson, P.S.; Taylor, W.C.; Dowda, M.; Sirard, J. Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirard, J.R.; Pate, R.R. Physical Activity Assessment in Children and Adolescents. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuo, Y.; Marzencki, M.; Hung, B.; Jaggernauth, C.; Tavakolian, K.; Lin, P.; Kaminska, B. Mechanically Flexible Wireless Multisensor Platform for Human Physical Activity and Vitals Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2010, 4, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strain, T.; Wijndaele, K.; Dempsey, P.C.; Sharp, S.J.; Pearce, M.; Jeon, J.; Lindsay, T.; Wareham, N.; Brage, S. Wearable-device-measured physical activity and future health risk. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, E.; Golaszewski, N.M.; Bartholomew, J.B. Estimating Accuracy at Exercise Intensities: A Comparative Study of Self-Monitoring Heart Rate and Physical Activity Wearable Devices. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunn, J.A.; Navalta, J.W.; Fountaine, C.J.; Reece, J.D. Current state of commercial wearable technology in physical activity monitoring 2015–2017. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Wen, D.; Liang, L.; Jia, Y.; Gao, L.; Lei, J. Evaluating the Validity of Current Mainstream Wearable Devices in Fitness Tracking Under Various Physical Activities: Comparative Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Singh, A.; Gupta, V.; Arya, S. Advancements and future prospects of wearable sensing technology for healthcare applications. Sens. Diagn. 2022, 1, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.J.; Al-Baraikan, A.; E Rademakers, F.; Ciravegna, F.; van de Vosse, F.N.; Lawrie, A.; Rothman, A.; Ashley, E.; Wilkins, M.R.; Lawford, P.V.; et al. Wearable technology and the cardiovascular system: The future of patient assessment. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e467–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Wearable Immersive Virtual Reality Device for Promoting Physical Activity in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Sensors 2022, 22, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahavandi, D.; Alizadehsani, R.; Khosravi, A.; Acharya, U.R. Application of artificial intelligence in wearable devices: Opportunities and challenges. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 213, 106541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, L.; Shields, M.A. Investigating the Economic and Demographic Determinants of Sporting Participation in England. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 2002, 165, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, B.R.; Ruseski, J. The Economics of Participation and Time Spent in Physical Activity; Working Paper No. 2009-9; Department of Economics, University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, K.; Breuer, C. The influence of socio-demographic indicators economic determinants and social recognition on sport participation in Germany. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, S324–S331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elena-Bucea, A.; Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T.; Coelho, P.S. Assessing the Role of Age, Education, Gender and Income on the Digital Divide: Evidence for the European Union. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 23, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.; O’Shea, E.; Kenny, L.; Barton, J.; Tedesco, S.; Sica, M.; Crowe, C.; Alamäki, A.; Condell, J.; Nordström, A.; et al. Older Adults’ Experiences with Using Wearable Devices: Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-synthesis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e23832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, H.-Y. Smart wearable devices as a psychological intervention for healthy lifestyle and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, W.; Kim, S.; Yu, C.; Woo, S.; Kim, K. Analysis of Health Management Using Physiological Data Based on Continuous Exercise. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2021, 22, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, T.; Amelard, R.; Wong, A.; Hughson, R.L. Extracting aerobic system dynamics during unsupervised activities of daily living using wearable sensor machine learning models. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 124, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golbus, J.R.; A Pescatore, N.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Shah, N.; Kheterpal, S. Wearable device signals and home blood pressure data across age, sex, race, ethnicity, and clinical phenotypes in the Michigan Predictive Activity & Clinical Trajectories in Health (MIPACT) study: A prospective, community-based observational study. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e707–e715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Ma, Q. The effects and patterns among mobile health, social determinants, and physical activity: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2021, 2021, 653. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Cárdenas, J.D.; Rodríguez-Juan, J.J.; Smart, R.R.; Jakobi, J.M.; Jones, G.R. Validity and reliability of an iPhone App to assess time, velocity and leg power during a sit-to-stand functional performance test. Gait Posture 2018, 59, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, T.B.; del Pozo-Cruz, B.; White, R.L.; Sanders, T.; Kirwan, M.; Parker, P.D.; Vasconcellos, D.; Lee, J.; Owen, K.B.; Antczak, D.; et al. A monitoring system to provide feedback on student physical activity during physical education lessons. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhu, S.; Li, W.; Yang, P. Design and Development of an Intelligent Skipping Rope and Service System for Pupils. Healthcare 2021, 9, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.H.; Tse, A.C.Y.; Wu, C.S.T.; Mak, Y.W.; Lee, U. Temporal association between objectively measured smartphone usage, sleep quality and physical activity among Chinese adolescents and young adults. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ráthonyi, G.; Ráthonyi-Odor, K.; Bendíková, E.; Bába, É.B. Wearable Activity Trackers Usage among University Students. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2019, 8, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.-Y.; Liao, Y.; Huang, H.-Y. Smart Wearable Device Users’ Behavior Is Essential for Physical Activity Improvement. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 29, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonze, B.D.B.; Padovani, R.D.C.; Simoes, M.D.S.; Lauria, V.; Proença, N.L.; Sperandio, E.F.; Ostolin, T.L.V.D.P.; Gomes, G.A.D.O.; Castro, P.C.; Romiti, M.; et al. Use of a Smartphone App to Increase Physical Activity Levels in Insufficiently Active Adults: Feasibility Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART). JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e14322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo-Peña, A.I.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Fernández-Ruano, M.L. Influence of gamification on perceived self-efficacy: Gender and age moderator effect. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2020, 22, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żarnowski, A.; Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M. Use of Mobile Apps and Wearables to Monitor Diet, Weight, and Physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Adults in Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e937948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, T.; Ha, J.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Jeon, G.; Cho, S. Physical Activity Pattern of Adults with Metabolic Syndrome Risk Factors: Time-Series Cluster Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e50663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Leaver, C.; Bourget, C. Diffusion of the Digital Health Self-Tracking Movement in Canada: Results of a National Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Nasseri, N.; Pöttgen, J.; Gezhelbash, E.; Heesen, C.; Stellmann, J.-P. Smartphone Accelerometry: A Smart and Reliable Measurement of Real-Life Physical Activity in Multiple Sclerosis and Healthy Individuals. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminorroaya, A.; Dhingra, L.S.; Nargesi, A.A.; Oikonomou, E.K.; Krumholz, H.M.; Khera, R. Use of Smart Devices to Track Cardiovascular Health Goals in the United States. JACC Adv. 2023, 2, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, C.L.; Powell, L.; Potter, S.; Parker, J.; A Mountain, G.; Bartlett, Y.K.; Farwer, J.; O’Connor, C.; Burns, J.; Cresswell, R.L.; et al. The Use of a Smartphone App and an Activity Tracker to Promote Physical Activity in the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Randomized Controlled Feasibility Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e16203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolovska, J.; Ostrovska, K.; Pahirko, L.; Varblane, G.; Krilatiha, K.; Cirulnieks, A.; Folkmane, I.; Pirags, V.; Valeinis, J.; Klavina, A.; et al. Impact of interval walking training managed through smart mobile devices on albuminuria and leptin/adiponectin ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.S.; Small, D.S.; Harrison, J.D.; Hilbert, V.; Fortunato, M.P.; Oon, A.L.; Rareshide, C.A.L.; Volpp, K.G. Effect of Behaviorally Designed Gamification with Social Incentives on Lifestyle Modification Among Adults with Uncontrolled Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2110255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauguel-Moreau, M.; Naudin, C.; N’guyen, L.; Squara, P.; Rosencher, J.; Makowski, S.; Beverelli, F. Smart bracelet to assess physical activity after cardiac surgery: A prospective study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, G.; Carver, K.; Curry, S.; Darby, A.; Sydes, A.; Symonds, S.; Wilson, K.; McGregor, G.; Auton, K.; Nichols, S. Changes in patient activation following cardiac rehabilitation using the Active+me digital healthcare platform during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cohort evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormel, H.L.; van der Schoot, G.G.F.; Westerink, N.-D.L.; Sluiter, W.J.; Gietema, J.A.; Walenkamp, A.M.E. Self-monitoring physical activity with a smartphone application in cancer patients: A randomized feasibility study (SMART-trial). Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3915–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Blarigan, E.L.; Dhruva, A.; E Atreya, C.; A Kenfield, S.; Chan, J.M.; Milloy, A.; Kim, I.; Steiding, P.; Laffan, A.; Zhang, L.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Physical Activity Tracker and Text Messages to Promote Physical Activity During Chemotherapy for Colorectal Cancer: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (Smart Pace II). JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e31576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Blarigan, E.L.; Chan, H.; Van Loon, K.; Kenfield, S.A.; Chan, J.M.; Mitchell, E.; Zhang, L.; Paciorek, A.; Joseph, G.; Laffan, A.; et al. Self-monitoring and reminder text messages to increase physical activity in colorectal cancer survivors (Smart Pace): A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Maxwell-Smith, C.; Cavalheri, V.; Boyle, T.; Román, M.L.; Platell, C.; Levitt, M.; Saunders, C.; Sardelic, F.; Nightingale, S.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of Promoting Physical Activity in Regional and Remote Cancer Survivors (PPARCS). J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, J.; Lopes, S.I.; Clemente, F.M.; Moreira, P.M.; Rico-González, M.; Bezerra, P.; Rodrigues, L.P. Wearables and Internet of Things (IoT) Technologies for Fitness Assessment: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesner, M.; Zowalla, R.; Suleder, J.; Westers, M.; Pobiruchin, M. Technology Adoption, Motivational Aspects, and Privacy Concerns of Wearables in the German Running Community: Field Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pobiruchin, M.; Suleder, J.; Zowalla, R.; Wiesner, M. Accuracy and Adoption of Wearable Technology Used by Active Citizens: A Marathon Event Field Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Egido, J.M.; Ortega, E.; Verdu-Conesa, I.; Cejudo, A.; Torres-Luque, G. Using Smart Sensors to Monitor Physical Activity and Technical–Tactical Actions in Junior Tennis Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barricelli, B.R.; Casiraghi, E.; Gliozzo, J.; Petrini, A.; Valtolina, S. Human Digital Twin for Fitness Management. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 26637–26664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaskey, M.A.; Schättin, A.; Martin-Niedecken, A.L.; de Bruin, E.D. Making More of IT: Enabling Intensive Motor Cognitive Rehabilitation Exercises in Geriatrics Using Information Technology Solutions. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4856146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, I.-Y.; Kim, H.R.; Lee, E.; Jung, H.-W.; Park, H.; Cheon, S.-H.; Lee, Y.S.; Park, Y.R. Impact of a Wearable Device-Based Walking Programs in Rural Older Adults on Physical Activity and Health Outcomes: Cohort Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioranzato, M.; Comoretto, R.I.; Lanera, C.; Pressato, L.; Palmisano, G.; Barbacane, L.; Gregori, D. Improving Healthy Aging by Monitoring Patients’ Lifestyle through a Wearable Device: Results of a Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Šetinc, M.; Dolničar, V. Benefits of a Wearable Activity Tracker with Safety Features for Older Adults: An Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).