Abstract

Pedestrian inertial navigation technology plays an important role in indoor positioning technology. However, low-cost inertial sensors in smart devices are affected by bias and noise, resulting in rapidly increasing and accumulating errors when integrating double acceleration to obtain displacement. The data-driven class of pedestrian inertial navigation algorithms can reduce sensor bias and noise in IMU data by learning motion-related features through deep neural networks. Inspired by the RoNIN algorithm, this paper proposes a data-driven class algorithm, RBCN-Net. Firstly, the algorithm adds NAM and CBAM attention modules to the residual network ResNet18 to enhance the learning ability of the network for channel and spatial features. Adding the BiLSTM module can enhance the network’s ability to learn over long distances. Secondly, we construct a dataset VOIMU containing IMU data and ground truth trajectories based on visual inertial odometry (total distance of 18.53 km and total time of 5.65 h). Finally, the present algorithm is compared with CNN, LSTM, ResNet18 and ResNet50 networks in VOIMU dataset for experiments. The experimental results show that the RMSE values of RBCN-Net are reduced by 6.906, 2.726, 1.495 and 0.677, respectively, compared with the above networks, proving that the algorithm effectively improves the accuracy of pedestrian navigation.

1. Introduction

A successful outdoor positioning system based on the global positioning system (GPS) has been developed. However, satellite signals are weakened indoors, such as underground and inside large buildings, making GPS useless for positioning. Indoor navigation and positioning services can be made available to users through indoor location-based services, which can boost pedestrian travel efficiency and make it easier for managers to prioritize pedestrian traffic.

The demand for indoor positioning is increasing as personalized networks become more popular. Indoor positioning technologies rely on various technologies, such as Bluetooth [1,2], WiFi [3], machine vision [4], ultra-wide band (UWB) [5] and inertial navigation [6]. The first four technologies are highly precise and relatively mature. However, each of these technologies has its own challenges to consider. Bluetooth and WiFi can be affected by electromagnetic interference and indoor obstacles. Machine vision needs to take into account user privacy concerns. UBW requires advanced facility deployment. Finally, inertial navigation can be challenged by drift during extended operation. Despite these limitations, no single positioning technology can provide a stable high-accuracy positioning service. Multisensor fusion technology is currently under development to address this challenge. In the complex indoor environment, high-precision inertial navigation can provide a reliable positioning service for pedestrians for a short period of time when other positioning technologies are temporarily disabled by electromagnetic interference. Additionally, it can provide correction information for other positioning technologies because inertial navigation is not disturbed by external factors and does not rely on any external signals. Therefore, high-precision pedestrian inertial navigation has a high research value.

The development of microelectro mechanical technology has led to the inclusion of inertial measurement units (IMUs) based on these systems in smart devices such as mobile phones, watches and wristbands. The use of IMU sensors in these devices for inertial navigation is very convenient and does not require the purchase of additional expensive equipment. However, compared to platform-based inertial guidance, IMU sensors in smart devices have several limitations due to their lower cost and other factors. Specifically, they generally have lower accuracy and higher noise levels. Conventional techniques frequently use double-integration methods to solve for position coordinates based on acceleration data, in which positioning errors caused by sensor measurement errors can quickly increase and accumulate, in addition to the direct solution process itself generating some errors. How to effectively eliminate the cumulative error of positioning has been a hot research topic in the field of pedestrian inertial navigation positioning. Better localization accuracy can be attained using the Kalman filter and zero velocity update (ZUPT) algorithm together [7], but these methods require pedestrians to fix IMUs on their feet, which is not compatible with the usage scenarios of most smart devices. In addition, these methods require high measurement accuracy of IMU, resulting in the requirement of more expensive sensors [8], which has kept such algorithms in the laboratory stage.

Data-driven methods have been recognized in recent years as the most effective means to suppress error drift by transforming the inertial tracking problem into a data sequence learning problem. The algorithms simultaneously collect IMU data and ground truth trajectory data over a short period to regress motion parameters (e.g., velocity vector and heading) and are proven to outperform traditional heuristics in terms of navigation accuracy and robustness. Among them, RIDI [9] made a breakthrough in coordinate system normalization by using SVM to regress the walking velocity vector and achieve the first accurate estimation of pedestrian velocity in a real indoor environment. Influenced by the generalization ability of deep neural networks, RoNIN [10] proposed a new concept of motion model-based RIDI and constructed multiple neural network models to successfully predict high-precision trajectories. To reduce the cumulative error caused by continuous double integration, IONet [11] partitioned the IMU data into independent windows and used long short term memory (LSTM) [12] algorithm to regress the rate of change of pedestrian speed and heading for each window. TLio [13] merged relative state measurements of neural network outputs into a stochastic cloning Kalman filter to further reduce pedestrian attitude, velocity and sensor bias. To solve the problem of inaccurate smartphone pose estimation, IDOL [14] proposed a two-stage neural network framework that uses a recurrent neural network (RNN) to estimate device pose in the first stage and a combination of RNN and extended Kalman filter to estimate device position in the second stage. Wang [15] combined neural networks and ZUPT to recognize pedestrian walking patterns using multihead convolutional neural networks, and adaptively adjusted the step detection threshold based on the walking pattern recognition results.

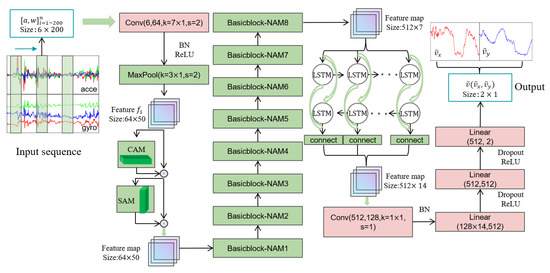

However, the existing data-driven methods still suffer from the problem of low navigation accuracy due to the simplicity of their network models. Taking inspiration from RoNIN, we have designed a new deep neural network model, called RBCN-Net (see Figure 1), to improve the ability of the network to regress pedestrian motion features. We achieve this by combining ResNet18 [16], bidirectional long short term memory (BiLSTM) [17], a convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [18], and a normalization-based attention module (NAM) [19]. By adding the attention mechanism, we address the problem of the network’s inability to distinguish the importance of features. To demonstrate the effectiveness of RBCN-Net, we conduct comparative experiments by constructing multiple network models using the VOIMU dataset to verify its ability to improve navigation accuracy.

Figure 1.

Overview of the method.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- To enhance the network’s ability to learn channel and spatial features, the NAM is added to each Basicblock of ResNet18, and the CBAM is added after the maximum pooling layer of ResNet18. Meanwhile, in order to enhance the network’s capability in long-range learning modeling, we add a BiLSTM network after the 8th Basicblock-NAM structure.

- (2)

- A dataset called VOIMU which contains 80 sets of IMU data of various walking routes with a total path length of 18.53 km and a time of 5.65 h. The ground truth trajectories are based on ocular inertial odometry. We will share all the datasets and codes for further research.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the network model; Section 3 presents the training data collection method, the data preprocessing steps, and the network model implementation details; Section 4 presents the experimental results and analysis; finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Description of the Algorithm

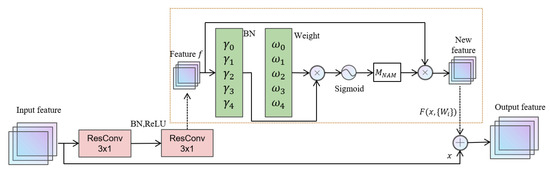

To solve the network performance degradation problem caused by the difficulty of convergence of training gradient dispersion as the depth of the network model increases in convolutional neural network (CNN) [20], ResNet [16] appends constant mapping to CNN to change the learning objective to the residual of the output and input features, making the output features contain more information than the input features. However, ResNet is unable to distinguish the importance between feature channels after feature extraction. As an efficient and lightweight attention mechanism, a normalization-based attention module (NAM) [19] does not require additional fully connected [21] and convolutional layers and instead highlights salient features using the variance metric between input feature channels.

2.1. Improved ResNet-NAM

Indoor positioning scenarios are characterized by a small amount of sensor data and high real-time requirements. Therefore, we choose ResNet18, which is a smaller network with the advantages of fast training speed and low risk of overfitting. ResNet18-1D version includes 8 Basicblock structures, and each Basicblock structure includes two 3×1 convolutional modules with the same number of channels. To distinguish the feature importance, this algorithm adds the NAM module after the 2nd convolution module of all the Basicblock structures. The Basicblock-NAM structure is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Basicblock-NAM structure.

The NAM calculates the variances between channels of the input feature vector f using the scale factor in the normalized BN. The variances are multiplied with the weight corresponding to each scale factor , and then the weights factor is obtained by the sigmoid activation function. The number of is the same as the number of feature channels, and the numerical magnitude reflects the importance of different feature channels. Finally, the output features are obtained by multiplying with the input feature vector element by element, and the input and output feature sizes remain constant. The weights are calculated as follows:

In Equation (1), is the proportion of the scaling factor among all scaling factors, f is the input feature vector of the NAM, and BN( ) is the inter-channel variance calculated as follows:

In Equation (2), and are the mean and standard deviation of the small batch f, and are trainable affine transformation parameters (scale and displacement). The improved ResNet18-NAM input and output features are related as:

In Equation (3), x and y are the input and output features of ResNet18-NAM, and is the residual mapping function. If the dimensions of the input features x and are the same, the values of the corresponding channels are added directly; otherwise, linear mapping is required to match them.

2.2. BiLSTM Structure

The inertial data collected by IMU devices follow a time-series pattern due to the highly repetitive nature of pedestrian pace. Santiago Cortés et al. [22] considered only CNN networks and ignored the time-series nature of the data. To fully learn the temporal correlation of inertial data features, enhance the long-range learning performance of deep neural networks and achieve more nonlinear transformations, a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network is added after the ResNet18-NAM in our algorithm. BiLSTM is a variant of LSTM [12] network, consisting of forward LSTM and backward LSTM stacking, which not only has the long-range sequence learning capability of LSTM model but also can better explore the backward and forward dependencies of inertial data. To obtain the BiLSTM output , the hidden state of the forward LSTM output and the hidden state of the backward LSTM output are connected. is calculated as follows:

In Equation (4), is the connection weight matrix from the forward LSTM to the output layer; is the connection weight matrix from the backward LSTM to the output layer; is the bias of the output layer.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Evaluation Indicators

The velocity vector predicted by the RBCN-Net is converted to the estimated coordinates , and the resulting trajectory is the estimated trajectory. As described in the previous section, real trajectories are generated from Google Tango data, and data frame i corresponds to real coordinates as . The evaluation benchmarks include root mean square error (RMSE) and average positioning accuracy (RTE). The RMSE provides a visual representation of the global agreement between the estimated and true trajectories [29], and the calculation formula is shown in Equation (11).

4.2. Experimental Environment and Hyperparameter Configuration

All studies in this paper were conducted on a laptop with a GPU configuration of GTX 1650. Because the training and testing results of the neural network model are strongly influenced by the parameters, so the learning rate is set to 0.0001 and the loss function of the model is compared every 20 epochs during the training process. The learning rate is reduced by a factor of 0.1 if the validation loss is not reduced. The batch size is set to 128 and the epochs are set to 1200. The training is completed in about 6 hours. The mean square error (MSE) loss function is used. It should be noted that the network will not converge if the initial learning rate for model training is set too large, causing the loss function value to oscillate.

4.3. Analysis of Validation Set Results

The evaluation metrics obtained for the validation set on the final trained RBCN-Net are shown in Table 1. The total trajectory length of the validation set is 1968 m, the average RMSE is 1.912, and the RTE values are all around 1%. It indicates that the model has excellent generalization performance on the validation set, and the error rate is not high. Meanwhile, the error of the validation set itself is relatively stable, with little difference between the same indicator parameters, because after normalization of the IMU coordinate system, the way the pedestrian manipulates the phone during data collection has little impact on the accuracy of navigation. The RMSE of NO.3 is higher than the other validation sets because the magnitude of the RMSE value is inversely proportional to the length of the trajectory.

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics of the validation set on the model.

4.4. Analysis of Test Set Results

In VOIMU, the test set contains twenty-four sets of experiments; the three groups with the best results and the three groups with the worst results are excluded, and nine experimental groups were randomly selected from the remaining test set for index evaluation. Table 2 displays the RBCN-Net evaluation indexes for the nine randomly selected experiments. The trajectory lengths of the nine groups of experiments totaled 1749 m, and the average RMSE and RTE were 2.07 and 1.45%, respectively. It indicates that the errors between the estimated trajectories and the real trajectories are small, all around the meter level, and the trajectory shapes match well. The RMSE and RTE of NO.2 are only 0.763 and 0.561%, which is a difficult positioning accuracy to be achieved by traditional inertial navigation methods [30].

Table 2.

Evaluation indexes of part of the test set.

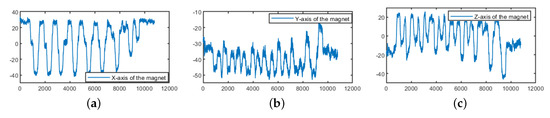

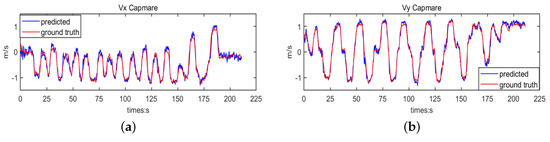

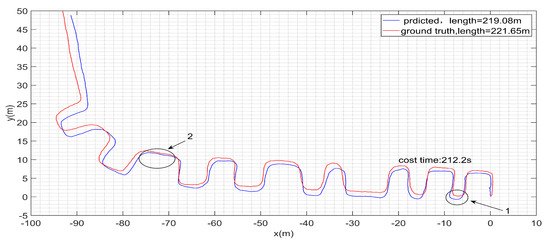

One more set of experiments was randomly selected among the nine sets for detailed data elaboration. The trajectory length of this experiment is 221.65 m and the time taken is 212.2 s. The raw magnet data of this experiment is shown in Figure 5. With each peak change, the magnetometer data’s magnitude varies in a pattern like a wave, and this corresponds to a pedestrian inflection event. In the case of short travel time, the pedestrian attitude obtained by solving the IMU data using the conventional attitude differential equation is closer to the actual attitude [31]. However, as the time increases, the solved heading angle error gradually becomes larger, which eventually makes the solved trajectory have a large heading angle deviation from the actual walking trajectory. In this paper, we use the RBCN-Net to fit the IMU data with the labels without considering the actual attitude of the phones with IMU. The set of experimental IMU data predicted by the RBCN-Net for the velocity vector versus the label is shown in Figure 6. The complete trajectory comparison is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 5.

The raw magnet data of this experiment. (a) X-axis magnetometer data, (b) Y-axis magnetometer data, (c) Z-axis magnetometer data.

Figure 6.

Velocity vector comparison. (a) versus , (b) versus .

Figure 7.

Comparison of the predicted trajectory and the real trajectorty.

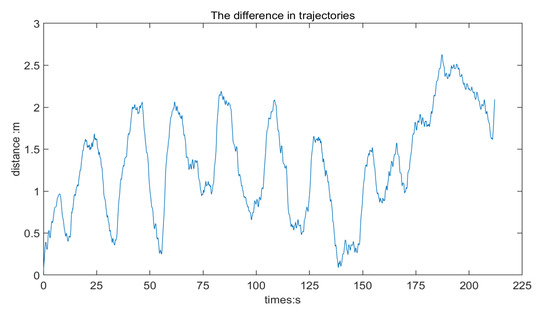

In Figure 7, the starting coordinates are both (0, 0), and the estimated and true end coordinates are (−91.32, 48.81) and (−93.09, 49.93), respectively, with an error of 2.24 m between the end coordinates. According to Newton’s first law of motion, the dual integration of the acceleration data is the trajectory length in the ideal case. However, in practice, sensor errors in IMU are unavoidable, and using the direct integration algorithm magnifies the errors exponentially. The estimated and true trajectory lengths of this experiment are 219.08 m and 221.65 m, respectively, with only 2.57 m difference. It indicates that the RBCN-Net completes the learning of dynamic and static error features in the acceleration data. There are some deviations between trajectories in region 1 of Figure 7, however, the trajectories in region 2 almost overlap with small errors, and the deviations are corrected rather than cumulative. The magnitude of the distance error between and at the same time t is shown in Figure 8, where the distance error oscillates between , indicating that the RBCN-Net effectively eliminates the inertial navigation system’s cumulative error. This experiment has an RMSE of 1.031 and an RTE of 0.603%.

Figure 8.

Distance error of coordinate points under simultaneous inscription.

4.5. Comparison of Base Network Models

The effects of different networks on pedestrian inertial navigation systems are investigated to validate the superiority of the proposed RBCN-Net. The four base models, CNN, LSTM, ResNet18 and ResNet50, are intended to be used in comparison experiments with the proposed RBCN-Net on the dataset VOIMU presented in this paper. The measured evaluation metrics are shown in Table 3. The RBCN-Net suggested in this research outperformed.

Table 3.

Position evaluation of five competing networks.

The other four networks with the best assessment metrics, an average RMSE of 2.079 and an average RTE value of 1.481%. ResNet50 and ResNet18 are second to RBCN-Net because the residual structure can effectively address the issue of network degradation. The LSTM network comes next. Although LSTM helps RNN’s long-term dependence issue to some level, it can still be challenging for longer-sequence data. The experimental outcomes are the poorest because CNN is not very well suited for learning time series.

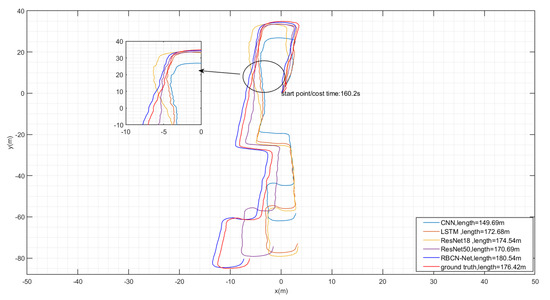

A randomly selected set of experiments in the test set was used for visual trajectory comparison, which had a total trajectory length of 176.42 m, took 160.2 s, and contained long straight lines and seven right-angle turns. The trajectory comparison is shown in Figure 9. The RBCN-Net predicted trajectory has the greatest overlap with the true trajectory. In the zoomed-in area, the pedestrian makes a second turn, and only this model predicts the route close to the true trajectory.

Figure 9.

Comparison of five competing networks trajectory and the real trajectory.

The specific evaluation indicators are shown in Table 4. RBCN-Net obtained an RMSE of 0.761, RTE value of 0.56%, and the endpoint coordinates differed by only 1.14 m in this experiment. RBCN-Net’s navigation accuracy is much better than other networks’. The effect is only second to the RBCN-Net is ResNet50, whose endpoint coordinates differ from the real coordinates by 9.52 m, and the RMSE value is 2.313, which is somewhat different from the true trajectory. ResNet18 and LSTM do not differ much from each other in this experiment.

Table 4.

Specific evaluation indicators.

4.6. Analysis of Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of CBAM, ResNet-NAM and BiLSTM for feature extraction, ablation experiments are conducted, and networks are designed to remove each module separately. The evaluation metrics of each model are measured on the previous test set, and the comparison results are shown in Table 5. Incorporating the NAM attention mechanism into the ResNet18 BasicBlock structure reduces the RMSE and RTE values of the ResNet-NAM model by 0.2 and 0.15, respectively. Adding CBAM after the maximum pooling layer reduces the RMSE and RTE values by 0.27 and 0.2, respectively. The above results confirm the effectiveness of the interactive assignment of feature weights by CBAM and NAM. In the proposed algorithm, the CBAM outperforms the NAM in terms of improving navigation accuracy. The addition of the BiLSTM layer to ResNet18 reduces the RMSE value by 0.93 and the RTE value by 0.68. This indicates that the BiLSTM is more important for the learning ability of time-related features than the attention mechanism. The addition of NAM and CBAM attention mechanisms to ResNet-LSTM reduces the RMSE value of 0.24, RTE value of 0.2, RMSE value of 0.39 and RTE value of 0.35, respectively. The RBCN-Net augments the ResNet-LSTM with both attention mechanisms, and the RMSE value is as low as 2.079 and the RTE value is as low as 1.481%. RBCN-Net reduces the RMSE value of 0.6 and the RTE value of 0.44 compared to ResNet-LSTM. RBCN-Net is more accurate for inertial data mapping compared with other models.

Table 5.

Comparison of results of ablation experiments.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

The data-driven class of inertial pedestrian navigation techniques faces the issue of low navigation accuracy brought on by straightforward network models. To solve this problem, the novel deep neural network RBCN-Net is proposed. On the dataset VOIMU used in this paper, networks including CNN, LSTM, ResNet18, ResNet50 and others are built and evaluated against RBCN-Net. The navigation accuracy is greatly increased with RBCN-Net, which also roughly matches the real trajectory.

The shortcoming of this paper is that the obtained trajectories are trajectories in two-dimensional planes, and are not adapted to indoor maps. Some unforeseen pedestrian behaviors, such as collisions, emergency turns, etc., cannot be handled by it. As a result, we will continue to develop our work to provide precise indoor localization on any mobile device, regardless of measurement units, users, or settings.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.Z. (Yiqi Zhu) and Y.Z. (Yanping Zhu); Software, J.Z. and B.Z.; Validation, Y.Z. (Yanping Zhu); Formal analysis, Y.Z. (Yiqi Zhu); Data curation, J.Z. and W.M.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z. (Yiqi Zhu) and J.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Y.Z. (Yanping Zhu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shan, G.; Park, B.; Nam, S.; Kim, B.; Roh, B.; Ko, Y. A 3-dimensional triangulation scheme to improve the accuracy of indoor localization for IoT services. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Pacific Rim Conference on Communications, Computers and Signal Processing (PACRIM), Victoria, BC, Canada, 24–26 August 2015; pp. 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, G.; Roh, B. A slotted random request scheme for connectionless data transmission in bluetooth low energy 5.0. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2022, 207, 103493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Yu, K.; Li, Q.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, W.; Hua, X.; Ma, W.; Chen, Z. Eight-diagram based access point selection algorithm for indoor localization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 13196–13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Shan, G.; Roh, B. A vision-based indoor positioning systems utilizing computer aided design drawing. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, Sydney, Australia, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 880–882. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, A.R.J.; Granja, F.S. Comparing ubisense, bespoon, and decawave uwb location systems: Indoor performance analysis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2017, 66, 2106–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, O.J. An Introduction to Inertial Navigation; No. UCAM-CL-TR-696; University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.; Gupta, A.K.; Händel, P. Foot-mounted inertial navigation made easy. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Busan, South Korea, 27–30 October 2014; Volume 22, pp. 695–706. [Google Scholar]

- Jao, C.; Shkel, A.M. A reconstruction filter for saturated accelerometer signals due to insufficient FSR in foot-mounted inertial navigation system. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Qi, S.; Yasutaka, F. RIDI: Robust IMU double integration. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Sachini, H.; Yasutaka, F. Ronin: Robust neural inertial navigation in the wild: Benchmark, evaluations, and new methods. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–1 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Lu, X.; Markham, A.; Trigoni, N. Ionet: Learning to cure the curse of drift in inertial odometry. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–3 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Graves, A. Long Short-Term Memory. Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2012; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Caruso, D.; Ilg, E.; Dong, J.; Mourikis, A.I.; Daniilidis, K.; Kumar, V.; Engel, J. Tlio: Tight learned inertial odometry. IEEE Robot. 2020, 5, 5653–5660. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Melamed, D.; Kitani, K. IDOL: Inertial deep orientation-estimation and localization. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2–9 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, H.; Xiong, H.; Men, A.; Zhao, F.; Xia, M.; Ou, C. Pedestrian dead reckoning based on walking pattern recognition and online magnetic fingerprint trajectory calibration. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 2011–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.01991. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Teng, Y.; Hoffmann, N. NAM: Normalization-based Attention Module. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.12419. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, L.O. CNN: A vision of complexity. Int. Bifurc. Chaos 1997, 7, 2219–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network in network. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.4400. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, S.; Solin, A.; Kannala, J. Deep learning-based speed estimation for constraining strapdown inertial navigation on smartphones. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 28th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), Aalborg, Denmark, 17 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohri, M.; Afshin, R.; Ameet, T. Foundations of Machine Learning, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Skog, I.; Nilsson, J.; Händel, P.; Nehorai, A. Inertial sensor arrays, maximum likelihood, and cramér–rao bound. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 64, 4218–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google: Project Tango. Available online: https://get.google.com/tango/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Leutenegger, S.; Lynen, S.; Bosse, M.; Siegwart, R.; Furgale, P. Keyframe-based visual–inertial odometry using nonlinear optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusebroek, J.M.; Smeulders, A.W.; Van, D.W.J. Fast anisotropic gauss filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2003, 12, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, J.; Jon, R.D. Gait analysis: Normal and pathological function. JAMA 2010, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, J.; Engelhard, N.; Endres, F.; Burgard, W.; Cremers, D. A benchmark for the evaluation of RGB-D SLAM systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.; Skog, I.; Händel, P.; Hari, K. Foot-mounted INS for everybody -an open-source embedded implementation. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Myrtle Beach, SC, USA, 23 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlström, J.; Skog, I.; Gustafsson, F.; Markham, A.; Trigoni, A.N. Zero-velocity detection—A Bayesian approach to adaptive thresholding. IEEE Sensors Lett. 2019, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).