Abstract

The fast depletion of fossil fuels and growing concerns about environmental sustainability have increased interest in using biomass as a renewable energy source. Fast pyrolysis, a thermochemical conversion process, has emerged as a promising technique for converting biomass into valuable biofuels and bio-based chemicals. The aim of this literature review is to comprehensively analyze recent advances in biomass fast pyrolysis, focusing on the principles, process parameters, product yields, and potential applications of biomass fast pyrolysis. This comprehensive review, based on an in-depth analysis of 61 scientific papers and 4 patents, provides an overview of various biomass technologies (combustion, gasification, pyrolysis) used for biofuel production. It focuses on the principles, benefits and applications of these technologies and serves as a valuable resource for researchers, engineers and policy makers. Based on the wealth of information from rigorously selected sources, we explore the key process parameters and reactor types associated with each technology, providing insight into its efficiency and product composition.

Keywords:

fast pyrolysis; bio-oil; bio-fuel; bio-oil composition; biomass; pyrolysis oil; biofuel review; biomass review 1. Introduction

Energy consumption has been growing in recent years due to population growth and economic development. By 2040, energy demand will increase by 37%, according to the International Energy Agency [1]. Renewable energy resources are composed of lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose and are becoming more popular because of the harmful effect of the use of fossil fuels on the environment.

Biomass comprises organic material derived from plants. This material results from the use of sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into organic matter; this natural activity is named photosynthesis [2]. As biomass resources, we can cite wood waste, crops and their by-products, municipal solid waste, food processing waste, and aquatic plants and algae [2], as well as animal by-products and animal waste [3,4,5,6]. Biomass technology is one of the best natural substituents for fossil resources, used for heating, generating electricity, and transport fuels production, chemicals, and biomaterials production [2]. It is also a considerable source of sustainable energy because it does not contribute to the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere and, at the same time, helps in the recovery of degraded land and increases biodiversity [2]. Thanks to promising technological developments, biomass applications can be realized at a lower cost and with higher conversion efficiency, having a direct impact on jobs.

The use of biomass for liquid fuel production involves thermochemical technologies, biological strategies, and multiple other strategies. One of the most common downstream biofuel production technologies is pyrolysis, followed by mild and deep hydrotreating [7].

Fast pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of biomass in an anaerobic environment; it is characterized by high temperature (above 450 °C) and short residence time, producing biofuel with a high yield of up to 75% on a dry biomass basis.

Pyrolysis has been the subject of several works for the valorization of lignocellulosic biomass [8]. It consists of decomposing organic matter under the effect of heat in an inert atmosphere to produce gases, oils, and char. The three pyrolysis technologies, slow, fast, and flash, allow the process to be oriented towards the production of specific pyrolysis products depending on the processing conditions. Reactor technologies have been developed to produce pyrolysis oils, which have attracted increasing interest since the 1979 crisis. Indeed, these oils present an alternative to polluting fossil fuels. However, their application as fuel remains limited by their low calorific value (16–19 MJ/kg) due to their high water content (30%) and their richness in oxygenated compounds.

Biomass-based economies extension is limited by problems associated with refining fast pyrolysis oils that are highly oxygenated oils. This challenge is preventing the large-scale use of these oils. Oxygen content is not the only problem that affects the performance of bio-oils during storage, handling, and upgrading, however; it also depends on the type and reactivity of these oxygen-carrying functional groups [7].

The main objective of this research work is the valorization of date palms for the production of biofuels. This study will highlight the different stages of the process. We start by studying the pretreatment process for fast pyrolysis and the preparation of the raw materials for biofuel production.

We take into consideration in this review of the literature on fast pyrolysis the different synonyms used to describe the same phenomenon, in particular “fast pyrolysis”, “fast pyrolysis”, and “flash pyrolysis”. From now on, we will use the term fast pyrolysis.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the research methodology; Section 3 provides an overview of biomass with different types; Section 4 deals with the fast pyrolysis of date palm biomass with synthesis and depicts a technology watch on the production of biofuel from date palms via fast pyrolysis technology; and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Research Methods

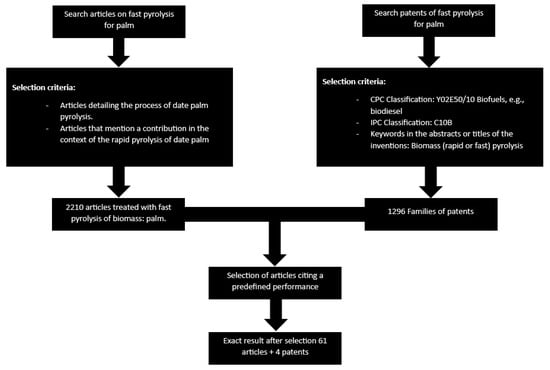

In this review, the research methodology followed was as follows (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Data extraction strategy.

3. Biomass Generalities

3.1. The Dry Process

The term “biomass” refers to all organic matter. This can include matter of vegetable (microalgae included), animal, bacterial or fungal (mushrooms) origin, which can be transformed into energy. The biomass is present in three forms, with very different physical characteristics: solids (for example, straw, plants, leaves, etc.), liquids (for example, vegetable oils, bio alcohols) and gases (for example, biogas. Produced from organic material undergoing anaerobic digestion, biogas is a combination of methane and carbon dioxide. Although commonly associated with biomass, it is actually a result of the fermentation of biomass and is not considered biomass gas) [9].

Energy derived from biomass is a renewable energy source that depends on the cycle of living plant and animal matter and is an energy born of the sun’s action through the phenomenon of photosynthesis [10]. This energy is reserved in the form of organic carbon, and its valorization requires specific processes according to the component used. Depending on the type of biomass and the technology used, the energetic valorization of the organic matter allows for producing three types of energy: the driving force for displacement, heat, and electricity [11]. According to the above, there are three methods of biomass valorization: the dry route, the wet route, and the production of biofuels.

The dry route of valorizing biomass mainly consists of thermochemical method; this mode include technologies such as combustion, gasification, and pyrolysis:

- -

- Combustion is a physical–chemical process producing heat through the complete oxidation of fuel in the presence of surplus air.

- -

- The hot water or steam obtained during combustion is mainly used in industry or in heating networks. This steam can be used in a turbine or a steam engine to produce mechanical energy. The production of electricity and heat from the combustion of biomass is called cogeneration [12].

- -

- Biomass gasification is a technology that uses plant material, bone meal, etc., to produce synthesis gas after a thermochemical reaction. The gasification process takes place in a specific reactor in four successive phases as follows: drying, pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction [13]. The gasification of biomass is one of the most important thermo-chemical transformation technologies, offering significant potential for the combination of various energy production systems. The gas generated through the gasification of biomass is an ecological alternative to the use of conventional petrochemical fuels for the generation of hydrogen, synthetic biofuels for transport, electricity and other chemical products. Gas from biomass contains CO, H2, CO2, CH4 and H2O, together with some organic impurities (tar, light hydrocarbon species) and other inorganic impurities (H2S, HCl, NH3), depending on the gasification process and operating conditions [14,15,16].

- -

- Biomass pyrolysis is the chemical decomposition of organic matter at high temperatures to obtain other products that it did not contain in the initial state; the product is obtained either in the form of gas or in the form of volatile matter. This operation is carried out mainly in the absence of oxygen or in an atmosphere that contains only a little oxygen to avoid oxidation and combustion of the organic matter; this technology does not produce a flame. Another variant of biomass pyrolysis is currently being used to treat contaminated biomass or organic household waste.

3.2. The Wet Route

The wet process of valorizing biomass is mainly represented by the methanation process, which is a technique depending on the decomposition of biomass by micro-organisms in a digester heated without oxygen, i.e., a process in an anaerobic environment.

Biogas is a product of the digestion of organic materials in an anaerobic environment. The digestate, which is the residue of the methanation process, is composed of non-biodegradable organic matter.

Supercritical water gasification (SCWG) and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), two successful methods for converting biomass into biofuels, have received increasing attention due to their fast reaction speed and the use of moist feed materials without the use of an energy-intensive drying process [17]. Gasification in supercritical water or hydrothermal gasification (HTG) displays the highest temperature and pressure among all hydrothermal conversion processes [18].

3.3. The Generations and Different Forms of Biomass

Biofuels are either solid (char), liquid (e.g., bio-oil from pyrolysis, Fischer–Tropsch products or methanol from synthesis gas, ethanol from sugar/starch fermentation, biodiesel from the transesterification of vegetable oils or animal fats) or gaseous (biogas from anaerobic digestion or methane and other light hydrocarbons from synthesis gas) [1].

If biomass is subjected to an elevated temperature in the absence of oxygen (pyrolysis), it is converted into solid carbon, gaseous and liquid products, which can be used as fuels. Liquid products include pyrolysis oil or bio-oil, with a density of around 1.2 kg/L. Bio-oil has a water content of 14 to 33% by weight, which cannot be easily removed by conventional methods (e.g., wastewater treatment, distillation), but bio-oil can be phase-separated above a certain moisture level, bearing in mind that the gross calorific value of bio-oil is generally between 15 and 22 MJ/kg, which is lower than the calorific values of conventional fuel oil (43.5 MJ/kg) and conventional heating oil (43–46 MJ/kg) [19].

There are three different generations of biofuel production in the biomass field: the first generation involves the production of biofuel from seeds, the second generation involves the production of biofuels from non-food crop residues, and the third generation involves the production of biofuel from microorganisms or from oil generated by microalgae.

The biofuels produced from biomass come in various forms: alcohols, pure vegetable oils, esters and biogas.

- -

- Alcohols are produced from the fermentation of plant starch or sugar, such as corn, beets, wheat, and sugar cane. The product obtained is called bioethanol.

- -

- Pure vegetable oils are generated through the simple cold pressing of oilseeds, notably rapeseed, sunflower and oil palm.

- -

- Esters are derived from oil plants and are obtained via a complex chemical transformation of the oils resulting from the pressing of the seeds.

Biogas is the gas generated by the fermentation of organic matter in an anaerobic environment. It is a combustible gas consisting mainly of methane and carbon dioxide [12].

3.4. Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Materials

Pyrolysis involves the decomposition by heat in the absence of air of an organic substance. It can be achieved under a vacuum or in the presence of an inert gas.

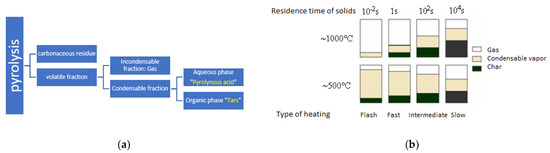

The pyrolysis products of lignocellulosic materials are a solid residue, charcoal, while the other products constitute a volatile fraction containing condensable and non-condensable materials (Figure 2a) [20]. The quality and quantity of the pyrolysis products and the composition of the volatiles depend on several parameters, among which are the characteristics of the treated material and the operating conditions. Indeed, three parameters are inseparable—the temperature, the heating rate, and the residence time. They greatly condition the yield and the distribution of solid, liquid, and gaseous products (Figure 2b). Pyrolysis processes are associated with either slow heating rates or fast heating rates. Fast pyrolysis processes at low temperatures are of great interest for oil production. Indeed, Figure 2b [20] indicates that the best oil yield is achieved at 500 °C under flash or fast pyrolysis conditions.

Figure 2.

(a) Diagram showing the different categories of pyrolysis products [20]. (b) Influence of heating rate (for the two temperatures of 773 K and 1273 K) on pyrolysis products as a function of temperature [20].

Fast pyrolysis at a high temperature is of great interest when one is interested in fluidized bed gasification processes, where the temperature is around 1173 K and the heating rate is high [21]. Fast pyrolysis offers several advantages, including maximizing gas production. Fast pyrolysis can also produce large quantities of gas, which can then be reformed to produce syngas. However, it is important to note that syngas itself is not directly used by many energy sources as it is considered a secondary energy source [22]. The resulting syngas, composed primarily of hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO), can be used in a variety of other energy systems and applications. It can be used as a versatile feedstock for other processes such as methanol synthesis, methane production or Fischer–Tropsch synthesis [23]. These downstream processes convert syngas into final energy products that can be used by various energy utilizations, including power plants, industrial applications or transportation systems [22,24].

3.5. Influence of the Parameters on the Products Used during Fast Pyrolysis

3.5.1. When the Temperature Increases

As we have seen previously, the biomass decomposes into three phases under the action of heat:

- -

- Condensable phase with oils composed of H2O, a number of organic substances and a number of inorganic substances. The inorganic substances are present in several forms. They include Ca, Si, K, Fe, Na, S, N, P, Mg and heavy metals [25]. The organic substances, frequently referred to as “tars”, are mostly polyaromatic hydrocarbons (molar mass between 78 and 300 g/mol) and aromatics [25,26]. The gaseous phase mainly includes H2O, CO, CH4, CO2, C2H4, H2, C2H2, and other heavier hydrocarbons, and the solid (char) phase mainly contains carbon with small amounts of hydrogen and oxygen. It also contains inorganic species.

With an increase in temperature, the quantity of gas produced by the various technologies increases [27], the amount of CO trained increases [28], the amount of hydrogen formed in the reaction increases with increasing temperature due to the gas phase cracking of the hydrocarbons, the amount of hydrocarbons formed diminishes in the temperature range 1873–2073 K [28], the amount of CH4 produced diminishes, and the amount of CO2 generated during the reaction increases.

Effect of residence time.

In the literature, the effect of residence time is found to be related to the temperature parameter in biomass pyrolysis technology [29]. The interactive effect of the residence time and temperature is the not necessarily well-accepted reduction caused by biomass pyrolysis for biomethanation. Boroson et al. [30] observed that as temperature and residence time increase, secondary reactions increase and tar molar mass decreases. A long residence time favors tar cracking and reforming [31]. On the contrary, a low residence time leads to a partial depolymerization of the lignin and encourages the production of bio-oils [32]. Fassinou et al. [33] discovered that when the vapor residence time is long, H2, CH4 and CO2 concentrations increase.

The C2H4 and C2H6 concentrations remained weakly influenced. Uddin et al. [34] described that a syngas produced via the pyrogasification of biomass for biomethanation favors the production of H2 with long residence times and high temperature [25,35,36].

Effect of pressure.

The work of Wafiq et al. [37] showed that pyrolysis of biomass is generally performed at high pressures compared to coal. Unlike temperature, the effect of partial pressure, as well as total pressure, is not a well-studied parameter in the literature.

The total pressure is fixed, on the one hand, in order to keep the system in the liquid state (light products, aqueous phase) at the reaction temperature and, on the other hand, in order to ensure solubility of hydrogen in the bio-oil [38]. The yield of CO2 increases with pyrolysis pressure, while the yield of high molecular weight gases like C2H4 and C2H6 decreases with increasing pyrolysis pressure up to 30 bar [38].

3.5.2. Influence of the Heating Rate

As the heating rate increases at a low temperature of about 773 K, the yield of biofuels produced in gases decreases, that of biofuels produced in condensable gases increases, and that of biofuels produced in carbon decreases [27].

When the heating rate increases at high temperatures, the efficiency of biofuel production in gases decreases. When the heating rate is high, it leads to the fast formation of gas, and thus a fast elevation of the pressure inside the particle with a sudden ejection of the gases produced. Meanwhile, the efficiency of biofuel production in condensable gases and coal decreases with an increasing heating rate [27].

According to a study that was conducted by Li et al. [39], the yield is low when the fast pyrolysis is performed at a temperature that varies between 773 K and 1073 K, while a high yield of H2rich gas is obtained at a high temperature (1073 K).

Another hypothesis was provided by Rolando Zanzi et al. [40]. Pyrolysis of oil palm husks was studied by using thermogravimetric analysis. The influence of heating rate on kinetic parameters (activation energy, frequency factor and reaction order) was investigated. Pyrolysis of oil palm shells was carried out in an inert atmosphere, using nitrogen as the medium gas. Experience shows that the kinetic behavior of the samples can be divided into three zones. The first zone lies within the temperature range 300–380 °C, the second between 380 and 450 °C and the third between 450 and 850 °C. The experimental results also showed that the activation energy was relatively constant despite the variation in heating rate. The different pyrolyzed biomasses and coal in a drop furnace showed that the heating rate had a significant effect on the distribution of pyrolysis products. The difference observed in the amounts of char formed by the biomass and coal is mainly attributed to the cellulose contained in the biomass. Indeed, the dehydration of cellulose into anhydrous cellulose, the intermediate compound responsible for the high char yields, takes place at temperatures below 573 K. Above this temperature, it is the volatile products that are formed in the majority. When the heating rate is very high, the residence time of the biomass at temperatures below 573 K is very low, and the dehydration of the cellulose does not take place. Little anhydrous cellulose is formed, and consequently, little char is formed. On the other hand, these conditions of high heating rate favor the formation of char with high porosity and high reactivity [40].

3.5.3. Influence of Particle Size

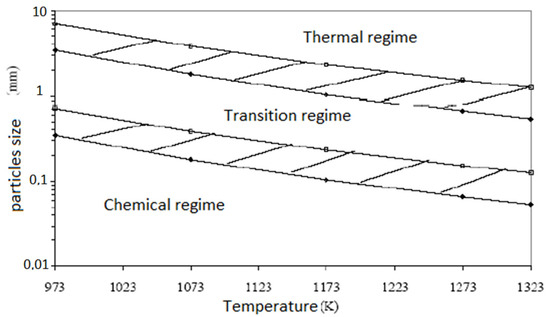

Wei, L [41] studied the effect of particle size (0.10 mm to 1.2 mm) on the formation of products of the fast pyrolysis of pine sawdust and apricot kernels at 1073 K. Mass and heat transfer have little influence on the formation of pyrolysis products in the case of particles with diameters less than 0.20 mm [41].

This is in accordance with the results in Figure 3. In contrast, for particles larger than 0.20 mm in diameter, pyrolysis is primarily controlled by mass and heat transfer within the particle [41]. This is in disagreement with the results in Figure 3, which indicate a transition regime, not a thermal regime, for particles with diameters between 0.2 and 1.2 mm.

Figure 3.

Pyrolysis regimes as a function of temperature and particle size [27].

In the literature, one finds many works concerning the influence of the size of the particles on the formation of the pyrolysis products. These works are generally carried out with particles whose size is between 0.1 and 2 mm. The results show that the smaller the particle size [28,42,43]:

- -

- The higher the gas yield.

- -

- The higher the H2 and CO yield

- -

- The more the quantity of CO + H2 synthesis gas increases

- -

- The larger the H2/CO molar ratio is

- -

- The more the yield of CO2 decreases

- -

- The more the hydrocarbon yield decreases. The gases are quickly expelled from a small particle, and therefore their residence time in the reactor is higher.

- -

- The more the yields of condensable gases and char decrease.

Several pyrolysis regimes are to be considered depending on particle size and temperature. In his work on biomass stratification, Dupont determined the boundaries between pyrolysis regimes as a function of temperature and particle size [35].

Figure 3 shows the pyrolysis regimes as a function of temperature and particle size [44]. The limits are not lines but thick hatched areas because they take into account uncertainties. This shows that the chemical reaction of pyrolysis is limiting for particles smaller than 0.1 mm at temperatures between 973 and 1100 K. In this case, the reaction is in the intrinsic regime.

Between 1173 and 1323 K and for particles between 0.1 mm and 1 mm, the reaction is in an intermediate situation, called the transition regime, which is neither a chemical nor a thermal regime. We are in the thermal regime for particles of several millimeters, with limitations caused by internal heat transfer.

3.5.4. Bio-Oil Composition

Biofuels offer an interesting alternative to traditional fossil fuels, which can be produced from different biomass feedstocks such as municipal, forestry, agricultural and industrial waste. The main component of biofuels is bio-oil, which contains a wide range of compounds. These can be categorized as acids, alcohols, esters, aldehydes, phenols, ketones, syringes, guaiacols, sugars, alkenes, aromatics, furans and various oxygenates. In addition, some nitrogen compounds can also be present. In the last decade, a large number of research groups have carried out in-depth studies on pyrolysis oil, a type of bio-oil, with a view to understanding its composition as well as its chemical and physical characteristics. This research has contributed to our knowledge of this increasingly complex substance and its potential applications as a renewable energy source [43,44,45,46,47]. Table 1 depicts the principal pyrolysis oil compounds determined and quantified.

Table 1.

Principal pyrolysis oil compounds determined and quantified by GC/MS (wt%) [44].

The date palm exists in Morocco. The palm groves cover an area of 50,000 hectares and are populated by 5 million plants. Morocco is thus ranked third in the Maghreb and seventh in the world for date palms [20], and in this context, the next section will be on the valorization of palm waste for biofuel production.

3.6. Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Waste

Solid waste from the palm tree includes trunks, leaves, empty bunches, fruit waste, and the cake that is a co-product of oil extraction from the nuts of the palm fruit. The press cake contains 6–15% oil, while the solvent-extracted cake contains no more than 3% oil [45]. The main components and some of the work carried out on oil palm waste are given in the tables below (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Main constituents of oil palm waste [48,49].

Table 3.

Existing works on the pyrolysis of waste from oil palm cultivation.

4. Summary of Existing Work on Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass

4.1. Synthesis of Recent Articles

A summary of recent articles on this subject is given in the following table (Table 4).

Table 4.

Recent papers on fast pyrolysis of biomass.

4.2. Technology Watch on the Production of Biofuel from Date Palms Using Fast Pyrolysis Technology

To construct a global perception of the fast pyrolysis of biomass, we conducted research ont the patents registered in this field.

The following table (Table 5) gathers the patents with the process used and the classification of the fast biomass pyrolysis: Y02E50/10 biofuels, e.g., bio-diesel, C10B, biomass (fast or fast) pyrolysis in titles, abstracts, the objective of the invention, palm in titles, abstracts, the objective of the invention, claims and three patents have been filed in the field of biomass pyrolysis.

Table 5.

Recent patents on fast pyrolysis of biomass.

This literature study allowed us to develop a better understanding of this subject, in particular, to determine the parameters of fast pyrolysis which influence the yield of bio-oil, which include temperature, residence time, pressure and the size of the studied particles. The literature describes several scenarios by varying these parameters. The best yields obtained vary between 70% and 80%. The table below (Table 6) shows the articles where the yield is high.

Table 6.

High yield research articles.

5. Conclusions

This review consists of recovering date palm waste through the process of fast pyrolysis to improve the liquid yield produced using this technology. There are several technologies that can be used to produce biogas: combustion, gasification, and pyrolysis.

According to a technology watch on biomass patents, there are 1296 patent families and 2210 articles on the subject of fast biomass pyrolysis of palm residues. Fast pyrolysis of date palms represents one of the most innovative and promising methods for biofuel production. Several experiments have shown that this technique provides a high yield of biofuel from date palm residues, which are considered an abundant and renewable source of biomass. However, it is important to take into account several parameters that have a direct influence on biofuel yield and the refining process. The chemical composition of date palm residues plays an important role in biofuel yield.

As explained in the article, the efficiency and yield of biofuel produced via fast pyrolysis depend on several key parameters, such as temperature, which directly influences the yield and quality of the biofuel produced. High temperatures can increase gas production, while low temperatures can favor biochar production. It is therefore important to strike a balance between these two aspects to maximize biofuel production while minimizing the formation of undesirable by-products. This process stabilizes the product, eliminates impurities and adjusts its properties to meet market requirements and standards. Various refining techniques can be used to purify and improve biofuel quality and performance, such as hydrogenation, distillation and deoxygenation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K. and M.B.; methodology, B.K., A.H. and F.K.-S.; validation, M.B. and F.K.-S.; data curation, B.K., A.H. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K. and A.H.; writing—review and editing, B.K., A.H., F.K.-S. and M.B.; resources, M.B.; supervision, F.K.-S. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Simpson, B.K.; Aryee, A.N.; Toldrá, F. (Eds.) Byproducts from Agriculture and Fisheries: Adding Value for Food, Feed, Pharma and Fuels; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes, R.E.; Luna, A.S.; Torres, A.R. Operating parameters for bio-oil production in biomass pyrolysis: A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 129, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Q. A review on the selection of raw materials and reactors for biomass fast pyrolysis in China. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 221, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzesińska, M.; Majewska, J. Physical properties of continuous matrix of porous natural hydroxyapatite related to the pyrolysis temperature of animal bones precursors. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 116, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Han, J.; Qiu, W.; Gao, W. Synthesis and characterisation of mesoporous bone char obtained by pyrolysis of animal bones, for environmental application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 2368–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Hou, Q.; Qian, H.; Bai, X.; Xia, T.; Lai, R.; Yu, G.; Ur Rehman, M.L.; Ju, M. Synthesis of mesoporous sulfonated carbon from chicken bones to boost rapid conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and carbohydrates to 5-ethoxymethylfurfural. Renew. Energy 2022, 192, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovikj, F.; McDonald, A.G.; Helms, G.L.; Garcia-Perez, M. Quantification of Bio-Oil Functional Groups and Evidences of the Presence of Pyrolytic Humins. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6505–6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouarzki, I.; Hazi, M.; Luart, D.; Len, C.; Ould-Dris, A. Comparison of direct and staged pyrolysis of the ligno-cellulosic biomass with the aim of the production of high added value chemicals from bio-oil. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016, 7, 1008–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Jendoubi, N. Inorganic Transfer Mechanisms in Bio-Mass Fast Pyrolysis Processes: Impacts of Lignocellulosic Resource Variability on Bio-Oil Quality. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Lorraine, Nancy, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, F.; van Eck, N.J.; Frey, M. The production of scientific knowledge on renewable energies: Worldwide trends, dynamics and challenges and implications for management. Renew. Energy 2014, 62, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, A. Optimisation de la Production d’Hydrogène par Conversion du Méthane dans les Procédés de Pyrolyse/Gazéification de la Biomasse. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Lorraine, Nancy, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yay AS, E.; Birinci, B.; Açıkalın, S.; Yay, K. Hydrothermal carbonization of olive pomace and determining the environmental impacts of post-process products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128087. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, L.J. Biomass gasification as an industrial process with effective proof-of-concept: A comprehensive review on technologies, processes and future developments. Results Eng. 2022, 14, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simell, P. Effects of gasification gas components on tar and ammonia decomposition over hot gas cleanup catalysts. Fuel 1997, 76, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Wooten, J.B.; Baliga, V.L.; Lin, X.; Chan, W.G.; Hajaligol, M.R. Characterization of chars from pyrolysis of lignin. Fuel 2004, 83, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Engvall, K.; Yang, W. Novel model for the release and condensation of inorganics for a pressurized fluidized-bed gasification process: Effects of gasification temperature. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6321–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Hydrothermal liquefaction and gasification of biomass and model compounds: A review. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 8210–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S.H. Gasification of Algal Biomass in Supercritical Water with the Potential of Energy and Nutrients Recovery. Ph.D. Thesis, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas, A. Competitive liquid biofuels from biomass. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déglise, X. Les conversions thermochimiques du bois. Rev. For. Française 1982, 34, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, C.F. Modelling of tar formation and evolution for biomass gasification: A review. Appl. Energy 2013, 111, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.R.; Tompsett, G.A.; Conner, W.C.; Huber, G.W. Aromatic Production from Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass-Derived Feedstocks. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausfelder, F.; Bazzanella, A. Hydrogen in the chemical industry. In Hydrogen Science and Engineering: Materials, Processes, Systems and Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roddy, D.J. A syngas network for reducing industrial carbon footprint and energy use. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 53, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H.B.; Seal, D.; Saxena, R.C. Bio-fuels from thermochemical conversion of renewable resources: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Biomass gasification: The understanding of sulfur, tar, and char reaction in fluidized bed gasifiers. Environ. Sci. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Couhert, C. Flash Pyrolysis at High Temperature of Ligno-Cellulosic Biomass and Its Components-Production of Synthesis Gas (No. FRNC-TH--7550). Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole des Mines de Paris, Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Makkawi, Y.; El Sayed, Y.; Salih, M.; Nancarrow, P.; Banks, S.; Bridgwater, T. Fast pyrolysis of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) waste in a bubbling fluidized bed reactor. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, S.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. Syngas biomethanation: Current state and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 358, 127436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroson, M.L.; Howard, J.B.; Longwell, J.P.; Peters, W.A. Product yields and kinetics from the vapor phase cracking of wood pyrolysis tars. AIChE J. 1989, 35, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, E.; Zeaiter, J.; Ahmad, M.N.; Kwapinska, M.; Leahy, J.J.; Kwapinski, W. The effect of temperature, residence time, and water-sludge ratio on hydrothermal carbonization of DAF dairy sludge. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 8, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Berruti, F.; Briens, C. Autothermal fast pyrolysis of waste biomass for wood adhesives. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassinou, W.F.; Van de Steene, L.; Toure, S.; Volle, G.; Girard, P. Pyrolysis of Pinus pinaster in a two-stage gasifier: Influence of processing parameters and thermal cracking of tar. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Daud WM, A.W.; Abbas, H.F. Effects of pyrolysis parameters on hydrogen formations from biomass: A review. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C.; Boissonnet, G.; Seiler, J.-M.; Gauthier, P.; Schweich, D. Study about the kinetic processes of biomass steam gasification. Fuel 2007, 86, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueras, J.; Benbelkacem, H.; Dumas, C.; Buffière, P. Biomethanation of syngas by enriched mixed anaerobic consortium in pressurized agitated column. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 338, 125548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafiq, A.; Reichel, D.; Hanafy, M. Pressure influence on pyrolysis product properties of raw and torrefied Miscanthus: Role of particle structure. Fuel 2016, 179, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. (Ed.) Progress in Thermochemical Biomass Conversion; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wang, L.; Koike, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tomishige, K. Steam reforming of tar from pyrolysis of biomass over Ni/Mg/Al catalysts prepared from hydrotalcite-like precursors. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2011, 102, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzi, R.; Sjöström, K.; Björnbom, E. Rapid pyrolysis of agricultural residues at high temperature. Biomass Bioenergy 2002, 23, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhu, H.; Liu, S. Characteristics of fast pyrolysis of biomass in a free fall reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2006, 87, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, A.; Vorobiev, N.; Schiemann, M.; Tarakcioglu, M.; Delichatsios, M.; Levendis, Y.A. Combustion details of raw and torrefied biomass fuel particles with individually-observed size, shape and mass. Combust. Flame 2019, 207, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinglan, H.; Chang, W.; Dingqiang, L.; Yao, W.; Dan, L.; Guiju, L. Production of hydrogen-rich gas from plant biomass by catalytic pyrolysis at low temperature. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 8884–8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.D.; Mondal, U. Valorization of Bio-Oils to Fuels and Chemicals; American Chemical Society (ACS): Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini, F. The biorefinery concept: Using biomass instead of oil for pro-ducing energy and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Vaccari, M.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Prasad, S.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Rtimi, S. Emerging technologies for biofuel production: A critical review on recent progress, challenges and perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Biofuels sources, biofuel policy, biofuel economy and global biofu-el projections. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Xiao, B.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S. Effect of particle size on pyrolysis of single-component municipal solid waste in fixed bed reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lua, A.C. Kinetic study on pyrolytic process of oil-palm solid waste using two-step consecutive reaction model. Biomass Bioenergy Biomass Bioenergy 2001, 20, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, M.H.; Hazwan, M. Extraction, Modification and Characterization of Lignin from Oil Palm Fronds as Corrosion Inhibitors for Mild Steel in Acidic Solution. Ph. D. Thesis, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga, V.J.C.; Arenas, C.E.R.I.K.A.; López, R.D.A.; Sánchez, L.C.M.; Zapata, B.Z.U.L.A.M.I.T.A. Biofuels production by fast pyrolysis of palm oil wastes (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Biotecnol. Sect. Agropecu. Y Agroind. 2012, 10, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Soon, V.S.Y.; Chin, B.L.F.; Lim, A.C.R. Kinetic Study on Pyrolysis of Oil Palm Frond. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2016; Volume 121. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.; Din, A.M.; Hameed, B.H. Pyrolysis of oil palm mesocarp fiber and palm frond in a slow-heating fixedbed reactor: A comparative study. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khor, K.H.; Lim, K.O.; Zainal, Z.A.; Mah, K.F. Small industrial scale pyrolysis of oil palm shells and characterizations of their products. Int. Energy J. 2009, 9, 532. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U., Jr.; Steele, P.H. Pyrolysis of Wood/Biomass for Bio-oil: A Critical Review. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 848–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deris, R.R.R.; Sulaiman, M.R.; Darus, F.M.; Mahmus, M.S.; Bakar, N.A. Pyrolysis Of Oil Palm Trunk (OPT). In Proceedings of the 20th Symposium of Malaysian Chemical Engineers (SOMChE 2006), UiTM Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia, 19–21 December 2006; Som, M.A., Veluri, M.V.P.S., Savory, R.M., Aris, M.J., Yang, Y.C., Eds.; University Publication Center (UPENA): Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2016; pp. 245–250. ISBN 983-3644-074. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, L.M.; Li, C.; Chew, J.J.; Aqsha, A.; How, B.S.; Loy, A.C.M.; Chin, B.L.F.; Khaerudini, D.S.; Hameed, N.; Guan, G.; et al. Bio-oil production from pyrolysis of oil palm biomass and the upgrading technologies: A review. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2021, 4, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, J.P. A Review of the Chemical and Physical Mechanisms of the Storage Stability of Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oils; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Din, A.T.; Hameed, B.H.; Ahmad, A.L. Pyrolysis Kinetics of Oil-Palm Solid Waste, Engineering. J. Univ. Qatar 2005, 18, 57–66. Available online: https://qspace.qu.edu.qa/bitstream/handle/10576/7932/060518-06-fulltext.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Al-Badri, H.T.; Lafta, S.J.; Barbooti, M.M.; Al-Sammerrai, D.A. The thermogravimetry and pyrolysis of date stones. Thermochim. Acta 1989, 147, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, L.B. Porosity Characteristics of Chars Derived from Different Lignocellulosic Materials. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 1999, 17, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahad, A.H.K.; Farhan, A.M.; Saleh, H.A. Using date stone charcoal as a filtering medium for automobile exhaust gases. Energy Convers. Manag. 1988, 39, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaak, P.; Knoef, H.; Stassen, H.E. Energy from Biomass: A Review of Combustion and Gasification Technologies; Technical Paper No. 422, Energy Series; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-8213-4335-1. [Google Scholar]

- Agblevor, F.A.; Besler, S.; Wiselogel, A.E. Fast pyrolysis of stored biomass feedstocks. Energy Fuels 1995, 9, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Al-Hattab, T.A.; Al-Hydary, I.A. Extraction of date palm seed oil (Phoenix dactylifera) by soxhlet apparatus. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2015, 8, 261. [Google Scholar]

- Lattieff, F.A. A study of biogas production from date palm fruit wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeguirim, M.; Dorge, S.; Trouvé, G.; Said, R. Study on the thermal behavior of different date palm residues: Characterization and devolatilization kinetics under inert and oxidative atmospheres. Energy 2012, 44, 702–709. [Google Scholar]

- Elmay, Y.; Jeguirim, M.; Dorge, S.; Trouvé, G.; Said, R. Evaluation of date palm residues combustion in fixed bed laboratory reactor: A comparison with sawdust behaviour. Renew. Energy 2014, 62, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.; Hari, T.K.; Yaakob, Z.; Sharma, Y.C.; Sopian, K. Overview on the production of paraffin based-biofuels via catalytic hydrodeoxygenation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 22, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, R.; Monteil-Rivera, F.; Lavoie, J.M. Conversion of lignin to aromatic-based chemicals (L-chems) and biofuels (L-fuels). Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 121, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, N.B.; Ibrahim, N.; Abd Hamid, M.K.; Hasbullah, H.; Ali, R.R.; Kasmani, R.M. Investigation of oil palm wastes’ pyrolysis by thermogravimetric analyzer for potential biofuel production. The 7th International Conference on Applied Energy—ICAE2015. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.W.; Koo, B.S.; Ryu, J.W.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, C.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kime, G.R.; Choi, S. Bio-oil from the pyrolysis of palm and Jatropha wastes in a fluidized bed. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 108, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnisa, F.; Wan Daud WM, A. A review on co-pyrolysis of biomass: An optional technique to obtain a high-grade pyrolysis oil. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 87, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vico, A.; Pérez-Murcia, M.D.; Bustamante, M.A.; Agulló, E.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; Sáez, J.A.; Paredes, C.; Perez-Espinosa, A.; Moral, R. Valorization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) pruning biomass by co-composting with urban and agri-food sludge. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastidas-Oyanedel, J.R.; Fang, C.; Almardeai, S.; Javid, U.; Yousuf, A.; Schmidt, J.E. Waste biorefinery in arid/semi-arid regions. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sait, H.H.; Hussain, A.; Salema, A.A.; Ani, F.N. Pyrolysis and combustion kinetics of date palm biomass using thermogravimetric analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Park, H.C. Method for Producing Bio-Oil Using Torrefaction and Fast Pyrolysis Process. Patent Number EP3388498A1, 17 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Freel, B.; Antunes, G.M.; Ribeiro, D.L.D.; Geoffrey, D.H. Integrated Process for the Pre-Treatment of Biomass and Production of Bio-Oil. Patent Number WO2017201598A1, 30 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, M. Systems and Methods for Re-Newable Fuel. Patent Number WO2022063926A2, 31 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, A.F.; Robert, G.G. Systems and Methods for Re-Newable Fuel. Patent Number WO2013090229A2, 20 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).