Abstract

Breast cancer is a primary cause of human deaths among gynecological cancers around the globe. Though it can occur in both genders, it is far more common in women. It is a disease in which the patient’s body cells in the breast start growing abnormally. It has various kinds (e.g., invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, medullary, and mucinous), which depend on which cells in the breast turn into cancer. Traditional manual methods used to detect breast cancer are not only time consuming but may also be expensive due to the shortage of experts, especially in developing countries. To contribute to this concern, this study proposed a cost-effective and efficient scheme called AMAN. It is based on deep learning techniques to diagnose breast cancer in its initial stages using X-ray mammograms. This system classifies breast cancer into two stages. In the first stage, it uses a well-trained deep learning model (Xception) while extracting the most crucial features from the patient’s X-ray mammographs. The Xception is a pertained model that is well retrained by this study on the new breast cancer data using the transfer learning approach. In the second stage, it involves the gradient boost scheme to classify the clinical data using a specified set of characteristics. Notably, the experimental results of the proposed scheme are satisfactory. It attained an accuracy, an area under the curve (AUC), and recall of 87%, 95%, and 86%, respectively, for the mammography classification. For the clinical data classification, it achieved an AUC of 97% and a balanced accuracy of 92%. Following these results, the proposed model can be utilized to detect and classify this disease in the relevant patients with high confidence.

1. Introduction

Following cardiovascular diseases, cancer has been the second-leading cause of human deaths on our planet. Based on the Saudi Ministry of Health, it is the most frequent type of cancer among Saudi women, which could also be observed in men but rarely [1]. It has been observed that the eastern region of Saudi Arabia has the highest breast cancer rate [2]. It has also been observed that the hereditary factor in breast cancer accounts for less than 10% of the total recorded cases. Within the regional context, the eastern region exhibits the highest incidence rate of 48%. It is worth noting that breast cancer is the leading cancer affecting women worldwide, with an annual incidence exceeding two million cases, which results in over half a million deaths each year.

Over the past few decades, there have been significant advances in computing machines in terms of both hardware and software. Today, most desktop PCs are equipped with large on-chip caches, GPUs, and multicore CPUs to efficiently process computationally expensive data, e.g., images and/or videos. Due to these advances, researchers around the globe are using these machines for machine learning applications such as artificial intelligence. With the advent of the latest deep learning technologies, it has now become practical to train different learning models (e.g., convolutional neural networks (CNN)) on large-scale datasets.

No doubt, the field of deep learning has significantly evolved over the past few years. In this regard, the research community has developed numerous robust and resilient algorithms. However, researchers also developed different large-scale image and video datasets for the purpose of training deep learning models. Most importantly, some developers went one step ahead and trained many deep CNN models (e.g., Xception, VGG16, ReseNet50, GoogleNet, and SqueezeNet) on large-scale datasets to learn about features of a vast variety of images such as cups, planes, watches, flowers, mice, and others. These trained CNN models (called the pretrained deep CNN (P-DCNN) model) are now open for the public to use for any other application.

With the approach of transfer learning, the P-DCNN models can be well-trained even on small image datasets, thereby bringing slight modifications to their last 2D-convolutional and classification layers. Due to this reason, today the medical imaging community and researchers are both trying their level best to use these deep learning schemes to increase cancer screening accuracy. Though breast cancer is serious and challenging to treat, it is preventable if detected in the preliminary stages, as compared with other cancers.

According to the Saudi Ministry of Health, early detection using mammography may significantly reduce the mortality rate, e.g., up to 30%. However, its late detection may worsen the patient’s condition and result in the patient’s death [3]. Based on the spirit of these highlights, this study is strongly focused on the following aspects:

- Reviewing the state-of-the-art in the breast cancer paradigm.

- Surveying the standard image processing breast cancer detection schemes.

- Analyzing contemporary deep learning schemes for cancer detection.

- Training DCNN models on the local hospital (King Fahad University’s Hospital Medical) data and reporting the final classification accuracy as well.

- Developing a fully automated tool to extract keywords describing the mammogram images according to the BI-RADS descriptors from the unstructured report and then using it to classify the resultant breast cancer, if any.

- Building two models for detecting breast cancer: one using mammogram images and the other using clinical reports.

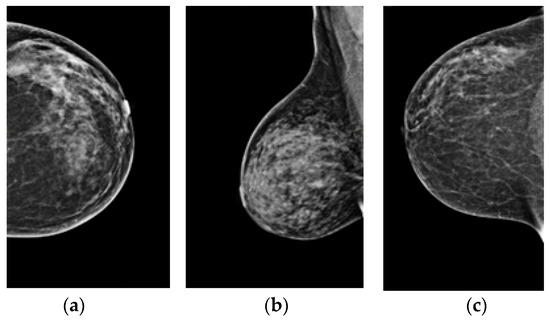

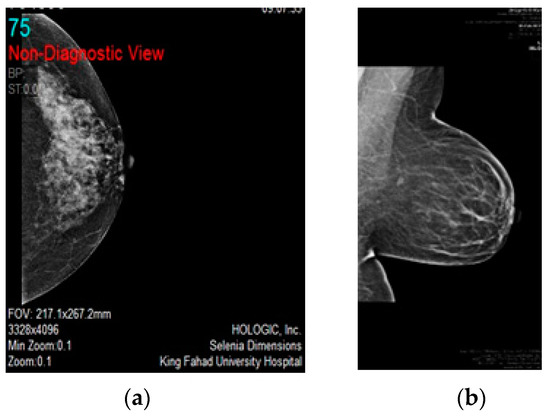

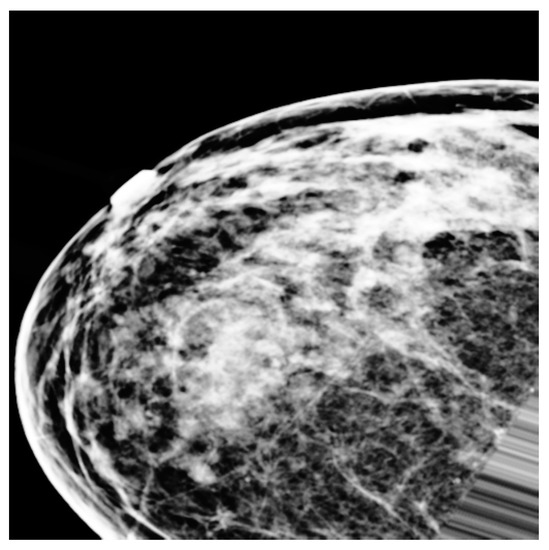

Figure 1a–c shows three types of breast cancer: benign, malignant, and normal mammograms, respectively. The early detection of breast cancer using a mammogram is an essential tool. It may reduce the breast cancer mortality rate and improve prognosis by detecting the subtle signs of early malignancy that can be easily missed by a general radiologist or less experienced breast radiologist [4]. Usually, a small, node-negative tumor under 10 mm in diameter may be effectively treated in nearly 90% of cases. However, this percentage lowers to about 55% when local-regional nodal involvement is present and 18% when distant metastases are present [5].

Figure 1.

(a–c) Benign, malignant, and normal mammograms, respectively.

Several innovative algorithms for digital mammography based on deep learning have been developed due to increased interest in using AI for medical imaging. The employment of AI-based systems as independent readers for mammography interpretation has been shown in several studies to boost radiologist productivity in terms of turnaround time, sensitivity, and specificity [6,7,8,9,10]. Most radiologists are using the BI-RADS (Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System) lexicon and reporting framework for breast imaging, including mammography, ultrasound, and MRI. The American College of Radiology created it as a quality control and risk assessment tool [11].

Mammograms are more suspicious of cancer if the mass is not circumscribed, has a high density, has a non-conforming shape, or is associated with macrocalcifications such as those found in the amorphous, coarse heterogeneous, fine-pleomorphic, or fine-linear branching forms in a grouped, linear, or segmental pattern [11]. Expert radiologists were never surpassed by the AI algorithms; however, an AI algorithm integrated with the judgment of radiologists in a single-reader screening module improves the overall system’s accuracy.

Numerous AI algorithms can be used to construct a robust system for detecting and classifying breast cancer. In the following sections, the authors highlight a selection of the commonly used AI schemes and P-DCNN models. Both machine learning and deep learning are used in a variety of medical research areas, such as diagnosis, prognosis, and decision support systems [12,13].

1.1. Gradient Boost (GB)

In terms of prediction speed and accuracy, gradient boosting is an approach that stands out among others. Errors are a common occurrence in machine learning algorithms, e.g., bias errors and variance errors. The gradient boost approach aids in reducing the model’s bias accuracy. The gradient-boosting approach gives equal weight to all data points in a decision tree. As a result, the misclassified points are given more weight than the points that were classified correctly. These models are provided with their decision stump to improve the initial stump’s forecast accuracy [14].

1.2. InceptionV3

Since 2014, the P-DCNN models have become widespread, delivering significant advances in many benchmarks. More extensive models and huge processing costs increase the quality of most tasks. At the same time, computational efficiency and low parameter counts are critical for use cases such as mobile vision and enormous data. With an error rate of 21.2% and 5.6%, Inception-V3 sets a new standard for single crop assessment using the 2012 ILSVR classification.

The approach requires far less computation than the best previously reported solutions for denser networks. Additionally, Inception-V3 proved that high-quality findings might be obtained with as little as pixel, and receptive field resolution. This might benefit systems that detect small objects. The use of batch-normalized auxiliary classifiers and label smoothing in combination with a low parameter count allows for the training of high-quality networks on training sets that are inherently small [15].

1.3. Xception

Xception is a term referring to Google’s extreme version of Inception. It is a unique P-DCNN model inspired by Inception in which the modules of Inception are substituted with depth-wise separable convolutions. Furthermore, it shows that the architecture of Xception outperforms that of Inception-V3 marginally on the ImageNet dataset for which Inception-V3 was built. Moreover, it also outperforms Inception-V3 incredibly on a more extensive image classification dataset, including 350 million pictures and 17,000 classes. Since Xception’s structure has the same parameters as Inception-V3, the performance gains are not due to increased capacity but to more efficient usage of the model’s hyperparameters [16].

1.4. InceptionResNetV2

The Inception-ResNet-V2 is pre-trained on a set of millions of images. Those images may be divided into one thousand different categories (i.e., classes) using the network’s 164 layers. Thus, the network’s feature representations for various images have become more complex. Class probabilities are calculated using a collection of image input dimensions of . It is created using Inception’s structure and the residual link. The convolutional filters of many sizes are merged with residual connections in the Inception-Resnet block. In addition to avoiding the degradation issue caused by deep structures, residual connections help save training time [17].

1.5. CNN

Convolutional neural networks (CNN) are a form of the artificial neural network (ANN) model. It enables the extraction of more complex representations for picture material despite traditional image recognition, which requires the user to specify the characteristics of the target picture. The CNN accepts images; raw pixel data trains the model and automatically extracts features for improved categorization. However, CNN is prone to overfitting if not managed appropriately, i.e., the model may get over-trained to the point that it is unable to generalize to new data [18].

The rest of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 describes background work, which includes binary and multi-level classifications of breast cancer. Section 3 elaborates on the structure and design of the proposed “AMAN” system. Results and discussions are carried out in Section 4. Finally, the conclusion and future work are highlighted in Section 5.

2. Related Work

Literature reveals that breast cancer is the earliest kind of cancer that has been known in humans. Although this illness has been extensively investigated and studied to mitigate its consequences, it is still considered the worst disease ever. In the last few years, many new procedures and strategies have been developed for the early identification of breast cancer in contemporary cancer detection and diagnostics using artificial intelligence. Most of these approaches use cutting-edge technology, e.g., image segmentation. This section offers numerous implementations of AI-based cancer detection and diagnostic systems, including but not limited to breast cancer, lung cancer, and liver cancer.

Deep learning is a subset of artificial intelligence (AI), which has made tremendous progress in medicine over the past few years. No doubt, early detection has always played a vital role in cancer detection. It can boost long-term survival rates, as medical imaging is commonly used to diagnose, track, and follow-up after cancer therapies [19]. Deep learning technology can help expert clinicians’ qualitative understanding of cancer imaging, such as volumetric tumor delineation, cancer stage, mutations, and an assessment of the effect of diseases on neighboring organs and the intensity of anti-cancer therapies [20]. Deep learning schemes are used in numerous cancer applications, e.g., lung, liver, gastric, esophageal, and breast cancer, which is mentioned in Section 2.2.

Gulum et al. [21] argued that it is essential to include medical staff in the design process of any deep learning algorithm. This act would result in reducing the misclassification rate and building trust between the system, medical staff, and patients. For high-risk decisions such as cancer, just defining where the network should look is insufficient, as most AI models for cancer detection do via post-hoc methods. As a result, the research is currently focused on easily interpretable deep learning for cancer detection and a novel ad-hoc method for developing explanations for deep learning models in a medical context.

2.1. Binary Classification of Breast Cancer

Priyanka et al. [22] review the limitations of machine learning in medical images, especially for cancer detection, which have been surpassed by the optimization of deep learning techniques. Xiong et al. [23] showed a three-dimensionality increasing in the identification of breast cancer, particularly abnormal and less malignant tumors. Both screening and identification mammography help screen the population. Three-dimensional (3D) mammography identified an increased rate of breast tumors in the axillary nodes. In addition, it also identified an increased number of breast cancers in the axillary lymph nodes.

Yi et al. [24] proposed a scheme to determine the tumor diagnostic performance of a digital breast biopsy in patients with non-calcified breast cancer. In this study, 106 females with invasive non-calcifying breast tumors who had DBT and FFD mammography were analyzed. Two radiologists who were blinded to the clinicopathological information assessed all DBT and FFDM pictures to determine the tumor grade (1–3) and analyzed the clinicopathological and imaging characteristics associated with the tumor visibility. Adding DBT to FFDM did not increase the early identification of non-calcified breast tumors in women with high-density breasts.

Lin et al. [25] advocated the merging of adversarial networks to deal with the mammography category imbalance and data scarcity. By merging the mass patches with the healthy breast pictures, a generative model is utilized to mimic mass development on normal tissue. The produced synthetic pictures are then used as complementary aberrant data to improve the stability of deep learning-based mass detector training and, consequently, the robustness of the final model. Breast mammograms contain synthetic masses, as positive samples may be generated using existing normal images. Extensive studies on the widely available breast dataset indicated a considerable increase in detection performance, demonstrating the usefulness of the suggested technique.

Kim et al. [26] elucidated the mechanisms underlying mammography screening’s inability to identify second cancer in females with a personal history of breast tumors. Individuals with later tumor recurrence and monitoring mammography within one year of recurrence are included in the data. When cells grow out of control in the breasts and form a tumor, breast cancer starts. Breast cancer signs include an increase in breast size, fluid discharge from the nipple, pain, and a lump in the breast [27]. Detecting and classifying breast cancer in the early stages of its growth can allow patients to have successful treatments to improve survival and healing [20].

In optical mammograms, the method of mass detection is image preprocessing and image segmentation, which divide an image into regions such that in each field one or more properties are homogeneous. Feature extraction is the method of image segmentation used in the classification of micro-calcifications. Classifiers play a significant role in implementing computer-aided mammography diagnosis, and the selection of features (FS) is an essential part of any machine learning task [28]. In real life, the principal available methodology to examine breast cancer is mammography (which is a type of X-ray). It is based on human observation, knowledge, and perception. Zanona et al. [29] proposed image processing with the aid of ANN computation for computerized sign detection and breast cancer exploration with an accuracy of almost 99%.

Badawy et al. [30] carried out a study to detect breast cancer using mammogram segmentation by using a double thresholding procedure to apply borders to the original image in the final segmented image. This approach is used for all biomedical images. One of its significant benefits is the reduction in processing time and storage area. The outcome indicates whether a person has breast cancer and shows the sections where the tumor is developing, providing satisfactory results for detecting breast cancer. Watanabe et al. [31] performed an early-stage analysis to detect breast cancer using the cmAssis algorithm, an AI-based deep learning CAD algorithm, to generate a successful result. As AI is used in cancer detection, its accuracy is based on several things. Researchers search for the effect of focus quality on the cancer detection algorithm’s efficiency. The results showed a steady decrease in the efficiency of the cancer detector with the expected out of focus (OOF).

Kohlberger et al. [32] developed a CNN (ConvFocus) to detect and rate OOF regions automatically at an accuracy level that suits a pathologist across the types of tissue, biopsy, and stain. Kumari et al. [33] proposed a system to predict breast cancer. The k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) classifier produced the highest accuracy compared with linear regression (LR) and support vector machines (SVM). In addition, researchers also used the filter method to pick the pertinent features from the available ones. This system reduces the cost of therapy because it can predict breast cancer at an early developmental stage.

Khan et al. [34] proposed a framework using transfer learning to detect and classify breast cancer. The goal of transfer learning is to apply the information learned during the solution of one problem to another in a similar scenario. In the proposed framework, features have been extracted from breast cytology images using three different CNN architectures (e.g., ResNet50, GoogleNet, and VGG16). Using transfer learning, all CNN architectures are integrated to improve classification accuracy, and then the researchers used the average pooling classification to classify the cells into malignant and benign.

Gao et al. [35] suggested a shallow-deep CNN distinguish breast cancer cases, whether benign or malignant, by combining two models. Firstly, they developed a shallow CNN that forms virtual recombinant images from low-energy images. Secondly, they developed a deep CNN to extract new features from low-energy images. The ensemble models are then recombined to classify the case using a decision tree called a gradient-boosting tree. A new mammogram categorization model using CNN was implemented by Mohsin et al. [36] for breast cancer detection, which categorizes cases into normal, malignant, and benign. They proposed two algorithms: convolutional neural network-discrete wavelet (CNN-DW) and convolutional neural network-curvelet transform (CNN-CT). Their findings validate the importance and effect of the proposed model.

Nasser et al. [37] suggested using super-resolution images to enhance the efficiency of CAD system texture analysis methods based on ultrasound images. To find tumors and differentiate between benign tumors. When a tumor is not spreading to the body, it is not cancer. It is classified as a malignant tumor when it can spread to other parts of the body [38]. Consequently, they demonstrated that their super-resolution-based approach increases the measured texture methods’ efficiency and exceeds the state of the art to classify benign/malignant tumors [37].

A breast computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) approach was suggested by Wang et al. [39] using mammogram images for the premature diagnosis, identification, and treatment of breast cancer based on feature fusion with deep CNN features. The mass detection process was based on deep sub-domain CNN features, and this approach was clustered by US-ELM to isolate the abnormal tissues. Using CNN, morphological features, texture features, and density features, the feature integration process incorporates deep features. After that, to distinguish benign and malignant breast masses, the mass diagnosis phase used ELM. The ELM has a better impact on classification than classifiers of multi-dimensional features. This experiment is superior to most existing methods of breast cancer diagnosis.

Chen et al. [40] proposed DenseNet, which is a deep learning classification model trained on 7173 historical tests before Sep 2017 and thereafter on 1194 instances. For the cross-validation and test sets, receiver operating characteristics generated by the DenseNet model predictions were greater than those generated by radiologist assessments. The DenseNet model produces excellent diagnostic performance, with an AUC score of 79%. Shah et al. [41] demonstrated breast cancer detection by classifying mammograms as malignant or benign using a range of variables. The proposed algorithm collects features from mammography pictures using a DCNN based on a highway network.

For the purpose of identifying breast masses via the use of textural description, spectral clustering, and support vector machines, Ahmadi et al. [42] proposed a full process-integrated technique for constructing a CAD system. Breast regions of interest are discovered automatically from mammogram images using gray-scale improvement and data cleaning to achieve this. Yamanaka et al. [43] showed the importance of machine learning. The recent improvement in AI-based image analysis may help in routine pathology detection. These studies may help pathologists make more exact and prompt diagnoses of patients. Furthermore, GradCAM finds previously unknown essential histological features for newer pathological findings and research goals for disease comprehension.

To enhance the accuracy of breast cancer detection, Sun et al. [44] examined feature fusion diagnosis using images from several modalities. Two hundred and one individuals with mammography and breast MRIs were retrospective. When compared to a single modality, the accuracy of MRI is superior to that of mammography.

Lahoura et al. [45] claimed that an extreme learning machine (ELM) is a form of ANN with great promise for classification. Three academic disciplines are brought together in the scope of this research paper: For starters, ELM is used in the detection of breast cancer in women who have already been diagnosed. After that, characteristics of no consequence are omitted using the gain ratio feature selection strategy. Finally, a remote breast cancer diagnostic technique is proposed that uses ELM, a cloud computing-based technology. The cloud-based ELM’s performance compared to that of many innovative illness detection systems. The WBCD data set proves that the cloud-based ELM technique beats the other models. Both the standalone and cloud settings, which were evaluated, yielded excellent performance results for ELM. The most important outcomes of the experiment show that the accuracy attained was high.

Kavitha et al. [46] proposed a new novel. The suggested method uses adaptive fuzzy-based median filtering to remove noise from mammogram images. Image segmentation is utilized by multi-level thresholding. An extractor model of cabinet-based features is proposed for the detection of breast cancer with this new detection approach. Rath and Sahoo [47] utilized a suitable threshold based on the Legendre neural network with a single layer and developed a computational technique for detecting and segmenting breast cancer. The three main steps of the method are image preprocessing, segmentation of mammograms using adaptive thresholding, and post-processing. The suggested segmentation method has a training stage with thirty images and a testing stage with 151 images from the MIAS standard database. The proposed model has high accuracy.

Das et al. [48] discussed two methods. In the first technique, pre-trained models were developed from scratch. The second approach employs the same principles as the first, except that all models have been fine-tuned via transfer learning. For this effort, the research explored convolutional neural network modifications. Experiments were conducted on two distinct datasets, and both datasets showed superior performance from the fine-tuned network. Rampun et al. [49] utilized deep ensemble learning. The proposed approach is built upon AlexNet with modifications to fit the classification problem. Following that, model selection selects the top three outcomes based on their validation accuracy throughout the validation phase. The results of the experiments show that combining the best models (ensemble networks) results in over 80% classification accuracy and area under the curve.

Masni et al. [50] introduced a unique computer-assisted diagnosis technology. The proposed CAD system can detect and classify simultaneously. The system was trained and evaluated using a public dataset. The method distinguishes benign from malignant tumors with high accuracy. For detecting breast cancer, Alhanahnah et al. [51] proposed a novel high-accuracy technique. This approach includes two stages. The first stage is preparing input images (mammography) for feature and pattern extraction using image processing methods. In the last stage. The collected features are then fed into two kinds of supervised learning models: the back propagation neural network (BPNN) model and the logistic regression (LR) model. According to the results, the LR model used more characteristics than the BPNN.

Choudhury et al. [52] compared three widely used machine learning algorithms and approaches for breast cancer prediction: Random Forest, k-NN (k-Nearest-Neighbor), and Naïve Bayes. As a training set, the Wisconsin Diagnosis Breast Cancer data set was used to assess the performance of several machine learning algorithms in terms of essential metrics such as accuracy and precision. The random forest, k-NN, and Naïve Bayes had exceeded the accuracy of 94.7%, 95.9%, and 94.4%, respectively. To predict breast cancer, M.O.F. et al. [53] proposed a deep neural network with feature selection algorithms. The proposed method is evaluated using several assessment benchmarks, such as train accuracy. The suggested method’s simulation results are promising, with an accuracy of 99.42%. The proposed technique is considered efficient and exact in predicting breast cancer based on experimental simulations and statistical data analysis.

The emergence of computer-assisted diagnostics programs aided radiologist mammography screening significantly. Since RCNN is computationally expensive, faster R-CNN was combined with an integrated mammographic CAD in this work by Jamil et al. [54] for simultaneous mass detection and segmentation. Bordering the lesions boxes with information on the lesions positions and sizes was performed for breast cancer detection and categorization of malignant or benign lesions. The bordered boxes were manually labeled by an expert radiologist for the image preprocessing part, and the CAD used a vertical and horizontal rotation of images to enhance the training dataset.

This retrospective study by Frazer et al. [55], which is based on artificial intelligence prediction models and ResNet as its foundation, proves the integration of mammography characteristics extraction and cancerous and non-cancerous regions detection in the image. To enhance the data quality, contrast adjustment, and background cropping with text removal (BCTR) have been proven to increase the performance of pre-trained models. Furthermore, using more training data shows a consistent improvement in performance. The study used mammographic images that were annotated by radiologists to show the regions of proven cancer by biopsy.

This study by Shen et al. [8] developed an approach—a prediction algorithm capable of effectively establishing the diagnosis on screening mammography that can aid radiologists. This method trained the images in two ways: the first one used the mammograms’ interpretations by the radiologists, while the second one only relied on the cancer status that was mentioned on the mammogram image. Krithiga and Geetha [56] used a deep-CNN approach to contribute to the detection, segmentation, and labeling of cell nuclei in breast tumors using anisotropic diffusion and a multilevel model in detecting the nuclei, which were then combined to produce a highly accurate nMSDeep-CNN model with a noticeably short computation time. Following detection, the cells are sorted into two categories: normal and cancerous, using a 10-fold cross-validation procedure.

Conte et al. [57] discovered that MRI has the highest sensitivity for detecting benign and malignant tumors. Consequently, they developed and validated a two-step CAD technique using DCE–MRI images to identify infiltrated from situ breast tumors. The first phase employs a threshold algorithm to find tumor-like patches. Using a machine-learning technique for feature extraction, the second stage classified the site as invasive breast cancer. The ROI Hunter software recognized 75% of tumor volumes during the segmentation process, but it also had an interactive feature that allowed the manual insertion of regions overlooked by the automatic detection/segmentation procedure.

Liu et al. [58] utilized the images of breast cancer slides in this research. To train and assess the model, researchers used two freely available datasets from the Internet. The images were randomly sampled into patches, and this study contributes to the reduction of false positives by increasing the ratio of these patches in the sample. As a result, the AUC and efficiency both improved significantly. Ruiz et al. [59] compared 101 radiologist evaluations of DM test groups against an AI system’s ability to diagnose malignancy. Each DM exam was scored by a radiologist, and the real detection rate was calculated. In total, there were 7 malignancies and 52 false positives among the 5082 screenings. In the seven tumors discovered through screening with low-risk ratings, all but one were considered clearly visible.

Kristina et al. [60] The application of artificial intelligence to identify benign breast mammography images in the context of breast cancer detection is discussed and evaluated in this article. One of the models proposed by A. Rodriguez-Ruiz et al. was investigated. The proposed artificial intelligence system is capable of accurately determining if a breast is cancer-free while also significantly lowering the number of false positives. As a result, artificial intelligence could boost digital mammography’s reliability. Sechopoulos et al. [61] report that multi-layered CNNs have made significant advancements in AI-based computer systems for detecting breast cancer risks. Mammography reveals the location of a suspicious breast mass. As a result, any method that involves automated DM image assessment should flag any suspect findings. The study suggested therapeutic applications for AI-assisted digital breast tomosynthesis interpretation and decision-making.

Transpara is a mammography-based automated breast cancer detection system. The system was employed by Ruiz et al. [7] The main functionality of the system is that it uses CNN and image analysis by combining data from various locations, knowing that each location has a value between 1 and 100 that represents the likelihood of malignancy (with 100 representing the highest suspicion). A final algorithm compares all locations discovered in the right and left breast images from 1 to 10, with 10 being the most likely to have cancer. Mayo et al. [62] AI-based and FDA-approved CAD algorithms were evaluated in terms of false positives per image (FPPI) on mammograms. A retrospective review of 250 full-field digital mammograms was conducted. Cases with no AI-CAD markings made up 48% of the total, while only 17% of the cases had conventional CAD markings. Research has shown that decreasing FPPI by 69 percent can reduce the reading time per case by 17%.

Swapna et al. [63] review the approaches recently considered to identify breast cancer. According to the findings of this study, using mammogram images as a dataset is the most effective method of detecting breast cancer. Patients will receive less radiation, the operation will be less expensive, and most importantly, the technology will be more accessible. Further, when it comes to classification, other methods are regarded as less accurate than sequential minimal optimization.

According to Golden et al. [64], the IEEE Institute sponsors the competition. Even though several teams submitted algorithms that were not deep learning-based, CNN fared significantly better. The top five algorithms outperformed pathologists, if not marginally. Adachi et al. [65] Facebook AI Research’s RetinaNet, a one-stage object detector, was utilized to train the AI system in this research to detect and assess cancer risk. RetinaNet’s creators claim that one-stage detectors trail two-stage detectors due to a class imbalance. Or, in other words, radiologists using AI had an AUC of 88.9, while non-AI radiologists had an AUC of 84.7. In [66], the authors employed two publicly available datasets to train and test a model using a faster area convolutional neural network. More training images were created via data augmentation. It also performed post-processing on several image attributes to decrease false positives. The proposed model outperformed all existing ultramodern algorithms using histopathology images, according to the study.

Chen et al. [67] evaluated medical mammograms for cancer detection using computer vision. Using previous image-based cancer research, the study built a more adaptive CAD detection method using modern cloud computer architecture. Breast cancer image segmentation in CAD uses low-level thresholds, region-based methods, and mathematical morphology. Naz et al. [68] The researchers examined existing techniques for breast cancer, explaining how the detection works in detail and focusing on classifications that are based on CNN, which have proven to show hopeful outcomes in the identification and classification of breast cancers in particular.

In [69], the study uses infrared images of the breast rather than mammograms, which indicate that the area with the highest thermal activity is most likely to be malignant. This was carried out using a pre-trained hemispheric model and deep learning. Cropping and grayscale conversion were used to preprocess the images in the study. The proposed model in this study achieved a greater degree of accuracy.

Hinton et al. [70] aimed to develop masking approaches for women with cancer after the reduction of breast density. A virtual lesion was constructed by adding a Gaussian profile to the mammograms, which mimics tumor sizes and lesion size ranges. It was calculated using the intrinsic quality factor (IQF). Silalahi et al. [71] demonstrated a method for automatically identifying and classifying lesions as malignant or benign. The breast database in FFDM format was used for the data set. The study employed two CNN-based machine learning frameworks with different schemes. It achieved an accuracy greater than 90%.

Ragab et al. [72] suggested a system that could classify benign and malignant tumors on mammography using deep learning and two segmentation methods to classify breast tumors. The first method manually delineated the ROI using circular outlines, as tumors in the DDSM were tagged with a red contour. In comparison, the second method uses the region-based method. The results are obtained using the DDSM and CBIS-DDSM. The best accuracy is 87.2% by using SVM. Eltrass & Salama [73] suggested a system for breast tumor diagnosis contingent upon five stages. The dataset was real clinical mammograms from the MIAS and DDSM, with clinical data for age and breast mass. The experimental findings show an accuracy of 98.16%.

Yap et al. [74] suggested detecting mass in FFDM. This approach uses the Faster R-CNN model to detect breast mammograms in OMI-DB, which has 80,000 FFDMs. It may be used within the clinical environment because it accepts the suspected masses’ input and output within the mammogram. Ansar et al. [75] developed a CNN classifier with training images from benign and cancerous tissues using a MobileNet-based architecture. DDSM is the world’s largest openly available mammography dataset, with over 2500 trials. For DDSM and CBIS-DDSM, the outcomes are 86.8%.

Zheng et al. [76] developed the DLA-EABA for breast tumor diagnosis utilizing sophisticated computational techniques and classic computer vision technologies. The system employs CNN-based transfer learning to perform diagnostic and prognostic tasks on breast tumors. Compared with other systems, the experimental system showed an excellent accuracy of 97.2%. Kumar et al. [77] developed ML methods for classifying cancerous and benign tumors, in which the system learns from prior information and can anticipate the class of the newest input. The performance of ML methods was evaluated using Wisconsin cancer datasets. The experimental findings show that SVM methods produce greater accuracy.

Raman et al. [78] suggested a DL and NN classifier for feature extraction, and the DDSM 1 dataset was used. The proposed ensemble model uses deep learning-based, pre-trained image processing. The NN was utilized to maximize the robust features retrieved from the ensemble models. The work was conditioned to distinguish benign from malignant tumors. It results in an accuracy of 0.88. Sundaram et al. [79] emphasized a detection system based on CNNs that utilizes DL to categorize mammogram pictures into benign, cancerous, or normal. The suggested approach uses CNNs to classify breast masses using medical image processing. The findings are compared to the k-NN classifier. The experiments employed three datasets. The proposed CNN model has higher accuracy with the three datasets.

Sayed et al. [80] evaluated the YOLO-V3 detector for breast cancer detection and classification. First, it converts the DICOM-formatted mammograms from the breast dataset to images without sacrificing any information, then it finds cancer in FFDM and automatically distinguishes between malignant and benign lesions. The feature extractors are ResNet and Inception. The outcomes are that the YOLO-V3 system is the most effective, and to achieve high accuracy, YOLO’s classification network is replaced by ResNet and Inception-V3.

Korial et al. [81] provided a system-supported mammography image for the purpose of early cancer detection. The suggested system was assessed using a knowledge set of 500 mammography pictures and a CNN model for training and testing. Deep learning technology was utilized to detect changes in tissue in the mammography images evaluated. On the other hand, the suggested technique estimates risk factors for unaffected individuals and uses this risk factor as a monitoring indicator for at-risk patients. The gathered data illustrates the suggested system’s efficiency in terms of high accuracy and a decrease in the effort required by medical professionals to help patients.

Adel et al. [82] used a classification system that consisted of three primary stages. The dataset is first extracted using image processing algorithms, and then it is subjected to data pretreatment procedures. Furthermore, they employ categorization algorithms based on machine learning. The dataset consisted of 34 individual patients, some of whom had numerous lesions while others had only one. The model has the highest level of precision, which is 0.94. Deep learning using a YOLO detector should be implemented and investigated for breast lesion identification from mammograms, according to Antari et al. [83] There are 2620 patients in the dataset, which is divided into 43 volumes. Each instance had four mammograms, each with two distinct breast slides (i.e., MLO and CC). The maximum accuracy was 0.99, while the average was 0.97. The only important disadvantage is that CAD systems were used to detect breast cancer.

Meenalochini et al. [84] investigated how machine learning techniques affect mammography image classification automation. Breast cancer is classified and identified using machine learning. They classified the dataset into three stages: pre-processing, feature extraction, and classification. They needed specified features collected and picked from mammography pictures (intensity, size, shape, and texture). The method’s outcome has an accuracy of 0.94. Muduli et al. [84] tested a model using two widely used datasets, DDSM and MIAS. The DDSM dataset has 1500 mammography pictures, 479 of which are benign, 519 normal, and 502 of which are cancers. MIAS includes 326 images. There are 207 normal images, 119 abnormal images, and 68 normal and 51 cancer types among the abnormal photographs. Furthermore, the MIAS dataset has a precision of 0.99 (normal vs. aberrant) and 0.98 (cancers vs. noncancers) for the DDSM dataset. Finally, there were constraints such as reduced learning speed, local minimum trapping, and more learning epochs.

Rajeswari et al. [85] advocated employing characteristics taken from the Hough transform to classify mammograms. A two-dimensional transform is the Hough transform. It is used in images to isolate the attributes of a specific shape. SVM was used to get 95 mammography pictures for the dataset. Getting images, preprocessing them, and extracting features using the Hough transform and SVM classification are among the approaches employed. The precision is 0.94.

2.2. Multi Classification of Breast Cancer: Analysis and Discussion

Numerous examinations have shown the effectiveness of the CNN model for multi-class breast cancer classification. For example, Sharma et al. [86] used the balanced public dataset to assess two machine learning breast cancer detection approaches. It uses the Humoment and Harlicka textures for the first approach. In addition, pre-existing networks are employed as feature extractors and model-based models for the second approach. The pre-trained network with SVM is the best for breast classification.

Dabass et al. [87] combine Gabor, wavelet, and structure-based information set features to improve mammography cancer diagnosis. To construct a ubiquitous information set, the intuitionistic fuzzy set is introduced. These characteristics are assessed on annotated private and public datasets using the hesitancy-based Hanman transform classifier. This classifier embodies and models the uncertainty in errors between training and test features. The proposed techniques achieve 100% accuracy for multi-class classification on public and private datasets, which is superior to existing methods. It will help radiologists discover breast cancer earlier.

In addition, breast problems such as calcifications, lumps, asymmetry, and carcinomas may be better managed with deep CNN. First, Khan et al. [88] used ResNet50, i.e., P-DCNN. Then, an improved deep learning model was created, in which the learning rate is one of the essential qualities while training the neural network. The suggested approach adapts the learning rate depending on changes in error curves throughout the learning process. The model classified masses, calcifications, carcinomas, and asymmetry mammograms with an accuracy of 88%.

Josh et al. [89] use deep learning and ultrasound pictures to screen for breast cancer. Based on the experimental results, deep learning may aid radiologists in clinical applications by accurately predicting clinical outcomes from 2D B-mode ultrasound images. The suggested technique achieves 96.31% accuracy, 92.63% sensitivity, and 96.71% specificity. It can process ultrasound picture frames per second, making it a very efficient machine. This technique outperforms earlier methods in real-time computer-aided diagnosis of breast tumors and benign-malignant categorization.

Weiming et al. [90] used a two-stage deep learning and machine learning architecture to classify breast digital pathology pictures into normal tissue, benign lesions, ductal carcinoma in situ, and invasive cancer. The suggested technique reached an overall accuracy of 85.19% for multi-classification and 96.30% for binary classification (abnormal versus normal). The suggested two-stage method might be used to classify breast pathology pictures and help pathologists diagnose breast cancer.

Alzubaidi et al. [91] developed a network to increase its breadth. Histopathological breast image categorization using a unique two-branch deep CNN as invasive cancer, in situ carcinoma, benign lesion, and normal tissue imaging is classified by the network using a public dataset. An advantage of the proposed network is that gradient propagation is possible. The proposed network outperforms earlier approaches by 83.6% by dividing the training set into patches and images. The public’s unseen test images were also classified with 89.4% accuracy.

Nguyen et al. [92] are scaling original images to build the CNN model and classify breast cancer. The model categorizes and finds breast cancer images from the public dataset. There are four benign and four malignant subclasses in this set. The proposed approach will automatically classify these breast cancer images into eight classifications, potentially saving lives globally. A new method for SURF selection by Kaur et al. [93] included pre-processing and intrinsic feature extraction using K-mean clustering. A decision tree model outperforms the recommended automated DL approach using K-mean clustering with MSVM. The method’s ACC rates for normal, benign, and malignant cancer are 95%, 94%, and 98%, respectively. SVM outperforms MLP and J48+K-mean clustering WEKA manual techniques in sensitivity, specificity, and ROC areas. The SVM, KNN, LDA, and Decision Tree results were 96.9%, 93.8 percent, 89.7%, and 88.7%, respectively.

Finally, Nawaz et al. [94] suggested classifying breast malignancies into subclasses such as lobular carcinoma. The model outperforms other models in multi-class breast cancer classification with %95.4 accuracy using a public dataset.

A literature review shows the effectiveness and potential of deep learning techniques, including CNNs, RNNs, integration with radiomics, and transfer learning, in enhancing breast cancer detection. These approaches offer promising avenues for improving diagnostic accuracy, helping with early detection, and contributing to more effective treatment strategies.

3. Proposed Framework—AMAN

The AMAN is a breast cancer detection system aiming to aid doctors and specialists facing difficulties while detecting breast cancer tumors, as shown in Figure 1. The goal of this system is to help cancer doctors and specialists make a critical decision in diagnosing breast cancer, especially in ambiguous cases when the mammogram images of the breast are not clear enough to make the decision.

Moreover, the clinical report that goes with these images will be used to enhance decision support. To perform our system, the authors will use a combination of AI tools on the cloud and the Saudi Arabian dataset from the King Fahad University Hospital to develop a system that will detect breast cancer early and reduce mortality. The system’s main target is to help the relevant breast cancer doctors and specialists in the field.

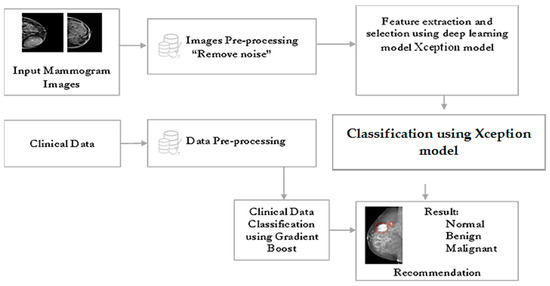

Figure 2 displays a block diagram of the proposed AMAN’S system. Mammogram images will be inserted into the system model, which will apply a pre-processing procedure in which the image will be enhanced and formatted using deep learning techniques, and it will segment the image into multiple parts to detect and find the tumor. Furthermore, the BI-RADS descriptors will be inserted into the system model that will apply data preprocessing to classify the tumor. Moreover, the system will implement the most correct model, the Xception model, to classify the mammogram images and the gradient boost to classify the clinical data based on our experiments to predict the tumor of the imported mammogram image and display the detection result as either normal, benign, or malignant.

Figure 2.

Proposed AI model.

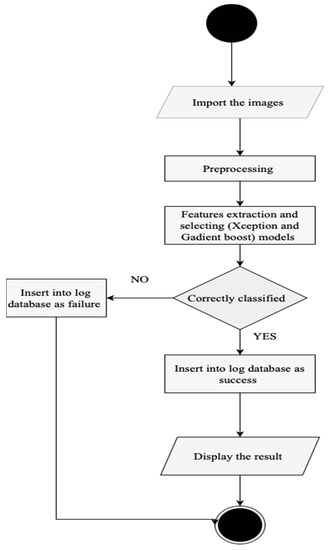

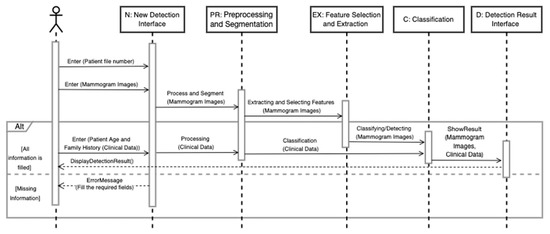

The AMAN system (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) is expected to be usable and acceptable to the end-user; it should have a straightforward and interactive interface. It must also be robust and secure to prevent system failures and damage. Credibility is a vital attribute of the system since it needs to use sensitive patient information and keep it safe from loss or damage.

Figure 3.

AMAN system procedure.

Figure 4.

View detection result sequence diagram.

3.1. Dataset Descriptions

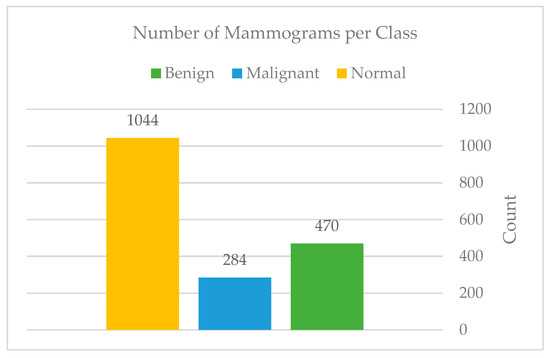

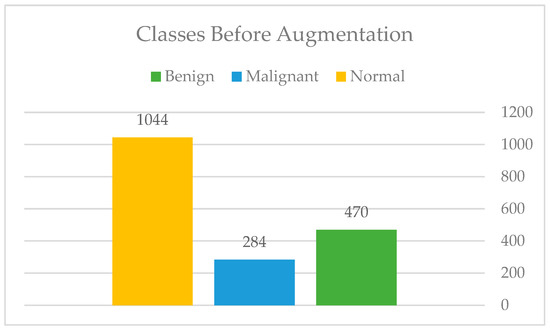

The authors collected all mammography examinations after receiving ethical approval from the Standing Committee for Research Ethics on Living Creatures (SCRELC) at Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University (IAU). These examinations are from King Fahad Hospital of the University (KFUH), affiliated with IAU in Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The dataset consists of 1802 craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views of bilateral breast images: 474 benign, 284 malignant, and 1044 normal.

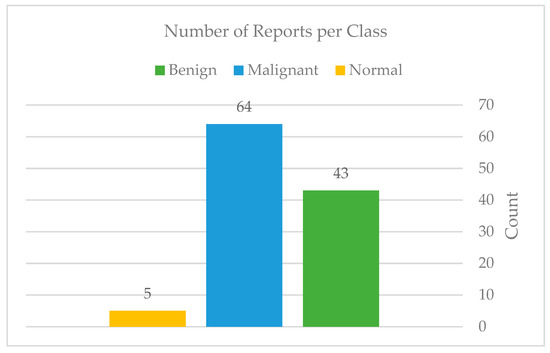

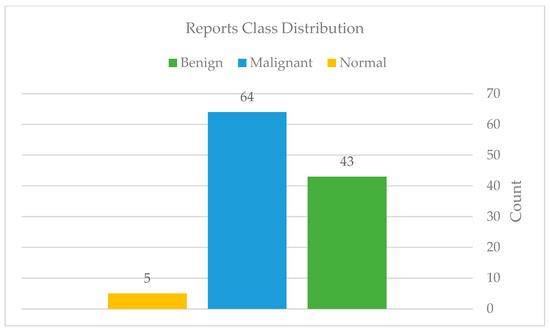

In our contribution, the authors expanded our dataset by adding 114 files of reported findings detected on mammography by the hospital’s radiologist; these reports follow the BI-RADS lexicon according to the American College of Radiology (ACR) classification. The reports include 44 benign, 65 malignant, and 5 normal examinations. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the number of mammograms and reports per class, respectively. Furthermore, no earlier research has used or published this data. Each patient has two different views of the right and left breast (MLO): mediolateral oblique and cranial caudal (CC). This resulted in four images for each patient. The authors gathered data from patients who had already had digital mammograms recently, considering the variety in terms of classes such as normal, benign, and malignant.

Figure 5.

Mammograms per each class.

Figure 6.

Total of reports per each class.

In this paper, two approaches have been investigated to provide a solid decision to the radiologists at the most suspicious and complicated stage: BIRADS-4. The first approach applies deep learning models to mammogram images for further classification, while the second approach applies machine learning models to clinical reports to extract the relevant features, contributing to a more consistent interpretation of screening mammography findings. The experiments with both approaches will be explained in the following sub-sections.

3.2. Mammogram Classification Using Deep Learning

In this dataset, the mammogram classification was incredibly challenging due to the high variation in breast shapes, density, and tumor size. Inevitably, extracting mammogram features is commonly done in two ways: using data annotation if the dataset is small, and using pre-trained models for feature extraction targeting larger datasets, which has proven to achieve good results in this field. As a result, due to the size of our dataset, manual data annotation was not possible. Thus, several pre-trained deep learning models on ImageNet have been compared to find the most suitable model for correctly classifying mammograms into three classes: benign, malignant, and normal. The deep learning model was implemented on the cloud using Google Collab Pro for GPU utilization. Multiple Python libraries have been used to implement the model, such as TensorFlow and Keras V2.8, NumPy V1.21.6, and Pandas ver. 1.3.5, Matplotlib V3.2.2, Sklearn V1.0.2, and OpenCV V4.1.2.

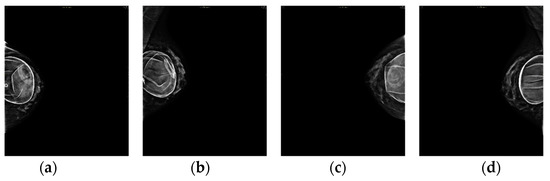

3.3. Preprocessing

The dataset was subjected to a number of pre-processing procedures. The goal of pre-processing is to remove noise from the dataset so that the models can perform at their best. As a start, the authors manually extracted and categorized the images into three classes: benign, normal, and malignant. Then, all records were reviewed to see whether there were any duplicates at this step. In addition, as Figure 7 shows, four breast implants have been removed in all the mammograms the authors selected, resulting in a total of 1798 mammograms. The breast implants were removed to prevent any confusion in the model.

Figure 7.

(a–d) Four breast implants: left (CC), left (MLO), right (CC), and right (MLO), respectively.

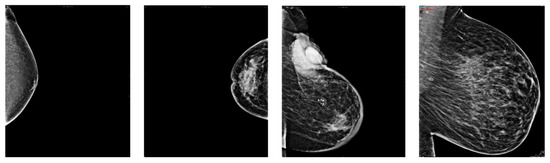

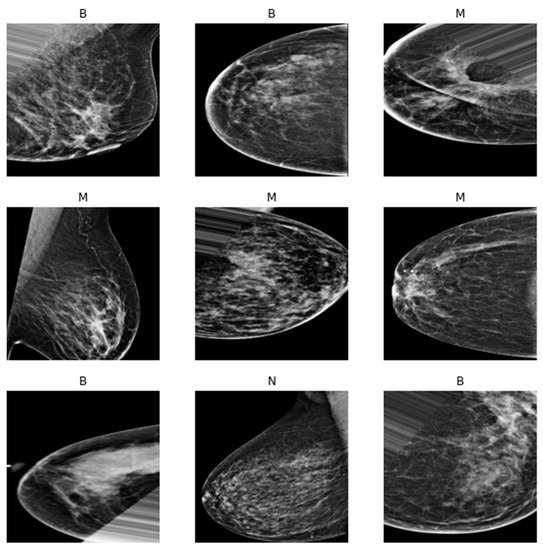

The mammography was then processed to remove as much noise as possible. Noise removal includes manual cropping of the mammogram’s background and text. The manual cropping was crucial due to the high variety of breast shapes, sizes, and mammogram quality. Figure 8 will show a sample of this wide variety.

Figure 8.

Breasts variety sample.

In terms of the number of mammograms, the patients’ data covered most of the upper part of the breast, as shown in Figure 9a. In contrast, some breast views were in between an upper data part and a lower data part, as shown in Figure 9b. This was vital to remove because it significantly increased the computational time and reduced the mammogram quality in the upcoming phases, e.g., resizing.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Text over breast and breast view in between data, respectively. Removing noise from mammogram images–for confidentiality reasons, authors omitted the patient’s name and ID number from the image.

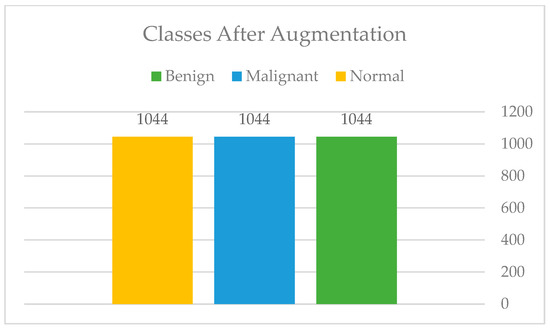

After the manual cropping, only those images that fall within the categories of benign and malignant were augmented so that the total number of images in each category was equal to that of normal images. Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the difference before and after applying the augmentation to the minority classes. Moreover, Figure 12: Augmentation sample clearly shows that the augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, zoom, filling, and brightness were only applied to the benign (B) and malignant (M) classes, while the normal (N) class remained intact.

Figure 10.

Classes before augmentation.

Figure 11.

Classes after augmentation.

Figure 12.

Augmentation sample.

In addition, after the augmentation, to improve the classifiers’ accuracy, the authors have performed some pre-processing techniques using OpenCV, such as Gaussian blur to reduce the noise, intensity normalization, and histogram equalization to enhance the edges and show the tumor clearly. Oddly, combining the three methods resulted in a decrease in performance for all the classifiers. The last step is, naturally, the resizing of this pre-processing, see Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Preprocessing sample.

3.4. Experimentations

In this section, some of the finest deep-learning models for breast cancer detection and classification have been tested and compared against each other. The following is a breakdown of the classifiers’ experiments.

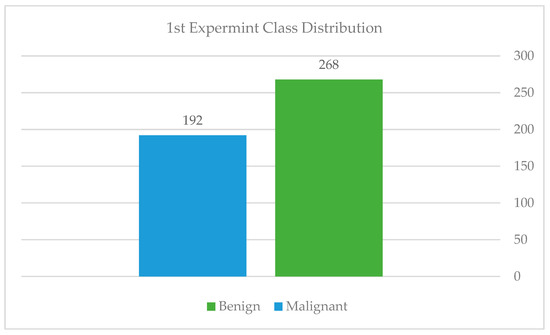

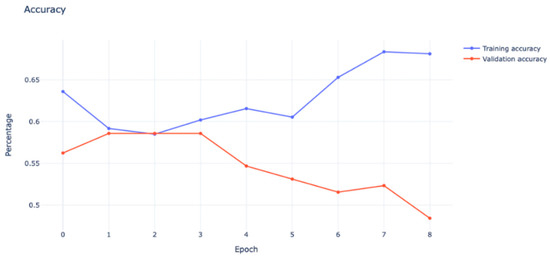

3.4.1. First Experiment

To assess the model’s performance when trained from scratch on mammography features, the authors first used a simple convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture, as detailed above. Five convolutional layers with filter values ranging from 16 to 128, five max-pooling layers, four dropout layers with a rate of 0.2 to minimize overfitting, and finally, one fully connected layer with 516 filters are used. ReLU was used as the activation function in the hidden layers, while the sigmoid was used in the output layer. We selected the sigmoid function because, at this point, we had just 460 mammography images from KFUH for binary classification cases, as shown in Figure 14. Due to the dataset’s small size, we used the Holdout cross-validation (CV) technique to divide it into eighty training samples and 20 testing samples. According to Figure 15, after fitting the model, we noticed an underfitting problem, not to mention a difficulty with the testing accuracy. This is why we contacted the radiology department to obtain more mammography images of benign and malignant tumors, as well as data on the “normal” class.

Figure 14.

Class distribution of the first experiment.

Figure 15.

Model underfitting.

As can be seen from the graph, the validation accuracy was heading in the negative direction, which showed a bad model performance that could not be improved by increasing the number of epochs.

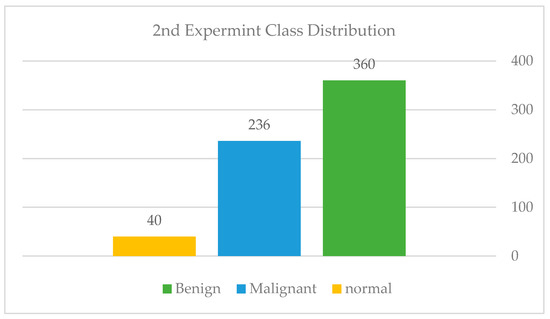

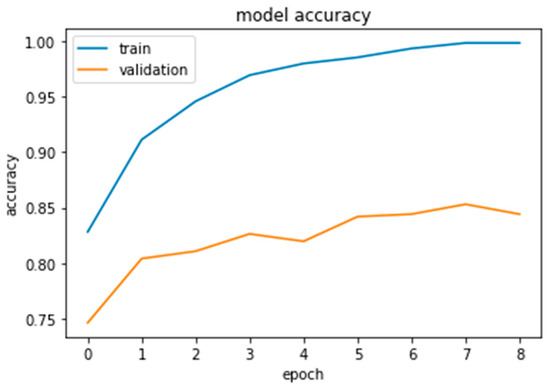

3.4.2. Second Experiment

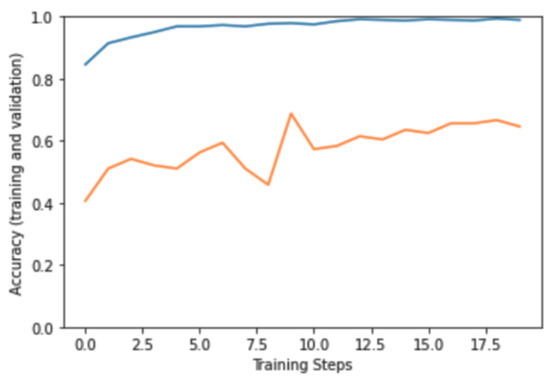

After collecting more samples from KFUH, we have acquired 637 mammography images from all three classes. The dataset at this point consisted of 636, as shown in Figure 16. We followed a different approach where we experimented with our dataset using pre-trained models to see how the model performed on this enlarged data. The InceptionResNetV2 model was used and fine-tuned on our dataset. Although the model was subjected to several optimization and preprocessing techniques, which are shown in Table 1, it still suffered from huge overfitting, as shown in Figure 17. Model overfitting (blue: training, orange: validation). The training accuracy was almost 98%, while the testing accuracy reached only 65% at best.

Figure 16.

Class distribution of the second experiment.

Table 1.

Techniques used to address the overfitting.

Figure 17.

Model overfitting—blue: training, orange: validation.

3.4.3. Third Experiment

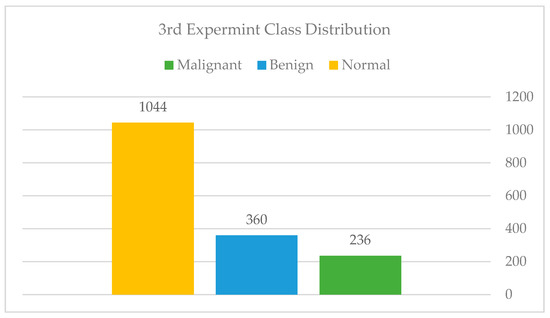

We attempted to address the issues raised in the prior experiment in this experiment. To begin, we called the radiologist to request further training data, particularly in the normal class, which had the fewest samples. After gathering and extracting the data, we arrived at a total of 1640 images. The distribution of classes in this experiment is depicted in Figure 18: Class distribution of the third experiment—Imbalanced.

Figure 18.

Class distribution of the third experiment—Imbalanced.

Additionally, we employed a technique known as stratified cross-validation. This method ensures that each class has the same proportion of its distribution in each fold; the technique is well-known for its ability to manage highly skewed datasets. The dataset was divided between 60% training samples, 20% validation samples, and 20% testing samples.

The model in this experiment was inspired by Sakib et al. [95] to address multi-classification difficulties in chest radiographs used to detect COVID-19. The model structure is as follows: a stack of convolutional layers, with each layer reducing the filter size by a factor of half. Then a stack of fully connected layers is created, with each consecutive layer reducing the filter size by a factor of half. Furthermore, as documented on the official TensorFlow website, the leaky rectified linear unit (LeakyReLU) activation function was found to be helpful in reducing overfitting. Thus, we employed the LeakyReLU and Adam optimizer functions along with data augmentation for all classes to further mitigate overfitting.

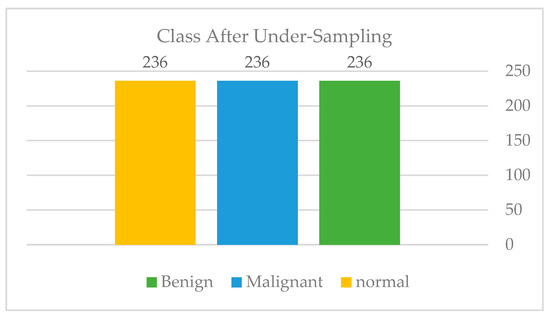

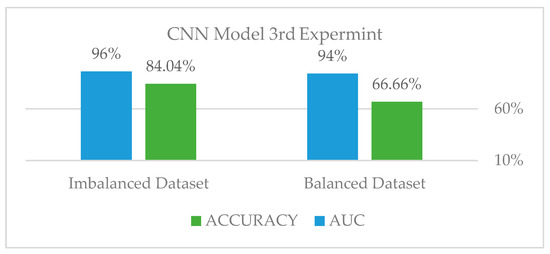

On the testing set, the data augmentation and stratified k-fold validation performed very well. Using five-folds, our strategy enabled us to achieve an AUC of 96.32 percent and an accuracy of 84 percent on the imbalanced dataset. However, we applied the exact approach to a balanced dataset via under-sampling, as shown in Figure 19: Class distribution of the third experiment—balanced, to determine whether the model can be improved further. As shown in Figure 20: Third experiment results in comparison and shown in Table 2, the results decreased drastically, leading us to conclude that the issue is extremely dependent on obtaining sufficient data.

Figure 19.

Class distribution of the third experiment balanced.

Figure 20.

The third experiment results comparison.

Table 2.

Class Distribution.

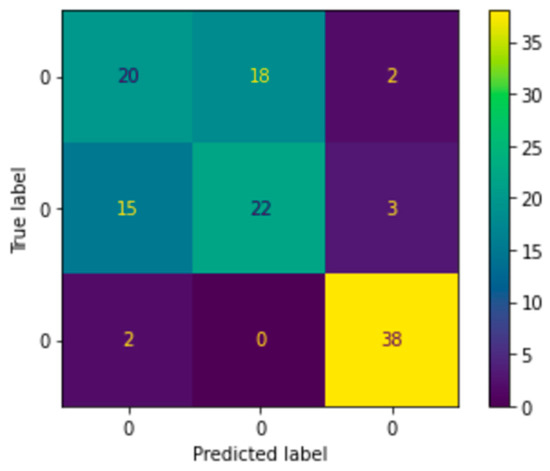

As illustrated in the balanced dataset’s Confusion Matrix Figure 21, which was displayed to analyze the problem in depth, the model properly classified the normal classes but was unable to distinguish between the benign and malignant classes. Thus, that is how we got to the next problem and the findings that came with it.

Figure 21.

Third experiment confusion matrix.

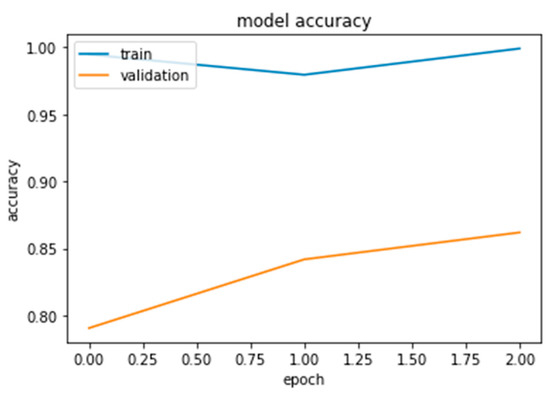

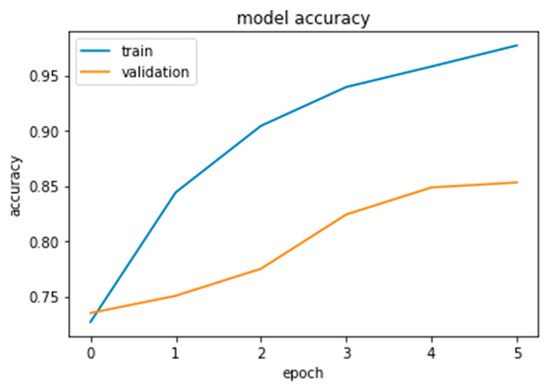

3.4.4. Fourth Experiment

As this is the final experiment, we tried to resolve the issues the authors encountered and then analyzed the difficulties to come up with a solution. The approach was to collect more data, both benign and malignant, until we reached a total of 1802. Additionally, to crop the photos to reduce computing time and noise in the dataset and to augment the data for the minority class only until it reaches the majority class. The authors increased the validation distribution by 5% in this experiment to see the effect. Sixty percent of the dataset was divided into training samples, twenty-five percent into validation samples, and fifteen percent into testing samples, as shown in Figure 22, Figure 23 and Figure 24.

Figure 22.

Xception results.

Figure 23.

InceptionResNetV2 results.

Figure 24.

Inception-V3 results.

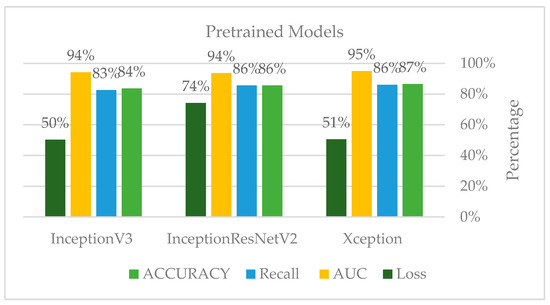

Furthermore, the authors conducted this experiment using pre-trained models to figure out their effect on feature extraction and to shorten the computational time associated with the stratified 5-fold cross-validation procedure. The three models considered for this study, Xception, Inception Residual Network, and Inception, were all well-known for their exceptional performance in the classification and diagnosis of breast cancer, as well as in medical imaging in general [96].

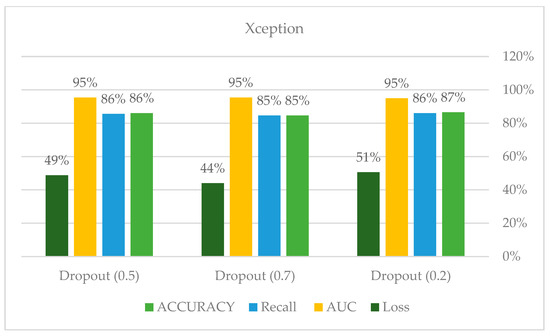

As shown in Figure 25 and Figure 26, compared to other tests, these models produced satisfactory results. Even though overfitting was still evident, we attempted to alter the dropout rate and record the results. Only Xception performed better than the others, and a dropout of 0.5 was the ideal value for all models.

Figure 25.

Third experiment results.

Figure 26.

Xception model hyperparameters.

3.4.5. Imbalanced Data Sampling Technique

The authors employed two strategies to address the imbalance in our dataset during our exterminations. To begin, we began using data augmentation for all classes in the third experiment, which demonstrated an increase in accuracy. Additionally, in the third experiment, under-sampling was utilized, as shown in Figure 11, to determine whether the model would perform better on a balanced dataset.

As a result, the model did not outperform the imbalanced dataset experiment; nonetheless, the findings clearly demonstrated the need for additional training data, as all models and experiments demonstrate. However, no SMOTE or oversampling of images was used in our model; rather than duplication, we aim to increase the variation in our dataset in order to increase the model’s generalization. Additionally, the authors employed data augmentation to create a balanced training set for the final experiment, as shown in Figure 13: Augmentation sample; this strategy significantly boosted our accuracy and yielded the best results.

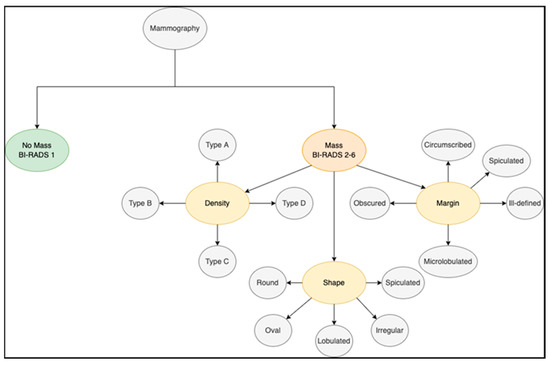

3.5. Breast Cancer Classification Using BI-RADS Descriptors

The breast imaging reporting and data system, or BI-RADS, is a reporting system set up by the ACR that supplies a universal language and reporting schema. It can be used for mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When it comes to mammogram images, BI-RADS supplies a reporting system for breast cancer findings. The KFUH dataset consists of examination reports that follow the BI-RADS classification system. As seen in Table 3, the system is divided into seven categories: BI-RADS 0 to 6 [11].

Table 3.

BI-RADS Categories.

Recently, the development of computer-assisted diagnosis methods for breast cancer based on the BI-RADS terminology has received significant attention. The utilization of classification algorithms has resulted in an astonishing level of diagnostic accuracy [97]. None of these diagnostic tools, however, utilized both image-based and BI-RADS descriptor-based methods. Using machine learning, we feel, will be a step toward a more standard interpretation of mammography findings. This tool can be shared across radiologists as a decision-making aid, leading to more trustworthy patient treatment. The machine learning model was implemented on the cloud using Jupyter Notebook.

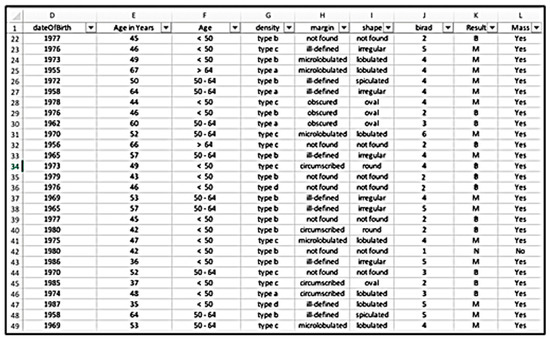

3.5.1. Preprocessing

The BI-RADS system (Figure 27) employs specific descriptors to characterize tumors. These are the density, shape, and margin descriptors. Each of these has its own category, as illustrated in Table 3. Our strategy is to classify mammography findings using these descriptors as features. In addition, patient age was added as a predictive variable because it has been established as a significant risk factor for breast cancer. Several preprocessing approaches were applied to our KFUH dataset to obtain the best results possible.

Figure 27.

BI-RADS categories.

To begin, the hospital reports were collected in “.docx” format; to help the operations, these reports were converted to “.txt” files using the doc2txt library. Following that, we designed a data extraction tool that converts unstructured reports to structured tabular data in an Excel sheet using BI-RADS descriptors as columns and their categories as rows, as seen in Figure 28. The tool was created by combining text processing techniques and Python libraries such as NumPy and Pandas. Although this tool was robust enough to collect all available data, we found a few difficulties since various radiologists describe their findings differently. As a result, there was a great deal of noise and missing data that required substantial cleaning and organization. For instance, one of the primary characteristics that supported our approach was the patient’s age. However, the reports only revealed the patient’s date of birth, which required us to calculate the patient’s age. Additionally, to improve classification, we switched the age from a numerical to a categorical variable. This was accomplished by classifying individuals’ ages into three categories: those under the age of 50, those between the ages of 50 and 64, and those over the age of 64. This method has been used successfully in previous studies [97].

Figure 28.

Data extraction tool.

After completing the necessary preprocessing, only 114 reports remained, consisting of the class distribution as seen in Figure 29.

Figure 29.

Reports classes distribution after preprocessing.

3.5.2. Feature Extraction

This stage transforms the tabular data into useful information for classification. To keep things simple, we eliminated tests with a BI-RADS category of 0, which indicates that the examination is incomplete and requires more imaging evaluation. Additionally, we did not divide BI-RADS category 4 into categories 4A, 4B, and 4C. We chose number 4 as a representation of the other sections. The categorical BI-RADS descriptors serve as features in our approach. The label “Mass” was used to categorize the findings into two groups: mass and no mass. This was done to differentiate between normal and abnormal examinations, as the presence of a mass shows the presence of a benign or malignant tumor. Moreover, we provided the feature “Result” as a label for our classification target, which includes the values “N” for normal, “B” for benign, and “M” for malignant. To prepare our features for use as inputs to our model, we used Scikit-Learn’s hot encoding technique to encode categorical features as a numeric array.

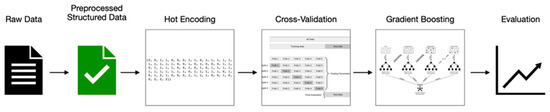

3.5.3. Classification

After preprocessing, the number of examinations that remained was quite modest. As a result, deciding which classifier to employ was challenging, as we were unable to obtain more examinations from the hospital. We expected to experience issues such as bias or variance error due to the size of our dataset. As a response, after completing an extensive study to find models that would be suitable for our case, we chose to work with Scikit-Learn’s gradient boost classifier. This classifier is a tree-based algorithm that generates a prediction model from a collection of weak prediction models. It applies to both regression and classification problems. However, in our study, we will use it to categorize examinations into three classes: normal, benign, and malignant. In other words, we will employ a multiple-class classification model. Gradient boosting, thankfully, provides this form of classification. Furthermore, one of the reasons we chose this classifier is that it helps us minimize the model’s bias, accuracy, and overfitting. Figure 30: A machine learning model road map illustrates the road map of our work.

Figure 30.

Machine learning model road map.

3.5.4. Model Fine-Tuning

Considering the size of the target dataset, there is still a possibility of overfitting. As a result, we chose to use the cross-validation technique to split our dataset. This method of splitting enables the generation of a test set from a subset of the existing data. As a result, it is not required to specify the validation set while performing this procedure. The basic strategy, named k-fold cross-validation, divides the training set into a smaller number of sets. In our model, we used five splits as the number of k-folds. After conducting several experiments, we made some modifications to fine-tune the parameters based on our target. These changes were applied to the number of estimators; we reduced it from 100 to 30. These changes improved our results, which will be addressed in further detail in the results sections.

4. Results and Discussion

In the proposed approach, the authors divided the evaluation measures into two categories based on two forms of classification: hard and soft classification. Soft classifiers explicitly calculate the conditional probability for each class before performing classification based on the estimated probabilities. Hard classifiers, on the other hand, are solely concerned with the classification decision boundaries and do not generate the likelihood of categorization. Both validation and testing data were subjected to these approaches.

4.1. Hard Classification

The authors utilized balanced accuracy for the hard classification because we are dealing with a multi-class classification. Our cross-validated model achieved 96% accuracy on our training data, 95% on our validation data, and 92% on our testing data.

4.2. Soft Classification

We utilized the ROC-AUC with the averaging type ‘ovr’ for the soft classification. “ovr” stands for one-vs.-rest. It calculates the AUC of each class in comparison to the others. This applies the same logic to the multiclass situation. Our cross-validated model achieved 99% accuracy on our training data, 97% on our validation data, and 97% on our testing data.

Both types of classification yielded comparable results. However, the soft probabilistic classification provided a higher testing score. This may be due to the class imbalance situation we have in our dataset. Additionally, it is well known that when it comes to imbalanced classification, accuracy is insufficient. The accuracy of a model can lose its validity if the class distributions have a large amount of skew. That is why we will be considering the classifier’s performance with ROC-AUC analysis.

4.3. Discussion

As described previously, multiple experiments were conducted on mammogram classification using several partitioning criteria, hyperparameter optimizations, incremental pre-processing, and balanced data sampling strategies to acquire the best performance for all classifiers examined. The initial experiment did not produce satisfactory results due to the lack of training data. When we received more data in the second experiment, the accuracy increased slightly, but we were still suffering from model overfitting. The study’s limitation is data availability—the availability of large and diverse datasets for training deep learning models.

Acquiring a comprehensive dataset that includes various breast cancer cases, demographics, and imaging modalities can be challenging. As a result, we attempted to use the cross-validation technique in conjunction with a stratified strategy in order to adequately address the imbalanced class. Thus, we conducted the third experiment and observed a significant improvement in accuracy. To address the class imbalance, we attempted under-sampling to reach the minority class; nevertheless, this experiment was not successful. Additionally, cross-validation was computationally intensive, which is why we chose to employ pre-trained models. Since it takes a long time to train from scratch, extract the features, and perform the validation splits.

In the fourth experiment, we addressed the overfitting problem by using pre-trained models. We experimented with dropout values to boost the findings further; for each classifier, a particular dropout value was ideal. We have achieved outstanding achievements by utilizing the resources available to us. However, if we had additional data, the models would likely perform much better. On the other hand, the BI-RADS descriptor classification model yielded a high testing score compared to the previous studies. However, the study has a restriction in terms of the number of examinations included in the dataset. We cannot assure that the sample selected was generalizable to the entire population because we removed a considerable proportion of those examinations that had missing results during data cleaning. Additionally, the data extraction tool built to extract features from examination reports was exclusively designed to function with the report structure used by King Fahad University’s Hospital. As a result, our methodology may not be suited to all practices. The suggested deep learning AMAN system is depicted in the AMAN system and is based on the results of all experiments. The maximum accuracy was achieved while consuming the fewest computational resources and using the fewest resources for image and clinical data processing.

5. Conclusions

The eastern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has the highest number of breast cancer cases among women. To combat this issue, this study proposed the AMAN system, which is based on the deep learning approach. While it uses the Xception model to extract features from the breast mammograms, it also uses the gradient boast methodology to classify the cancer type. In contrast with traditional breast cancer detection schemes, AMAN exhibited the highest accuracy while finding and classifying breast cancer. As it is well-trained on the patient’s mammograms, it can safely detect and classify breast cancer in relevant patients.

In the probable future, the authors aim to integrate these two models (i.e., Xception and gradient boast) being developed in this study to get more reliable results in the future and deploy the AMAN system in real-time applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.I.; Methodology, N.M.I. and B.A.; Software, B.A., F.A.J., M.A.Q., R.I.A. and S.A.A.; Validation, K.R.A., M.A., A.F.A.-M. and H.M.A.; Formal analysis, M.A.Q. and R.I.A.; Investigation, B.A., F.A.J., M.A.Q., R.I.A. and S.A.A.; Data curation, A.F.A.-M.; Writing—original draft, B.A. and R.I.A.; Writing—review & editing, N.M.I., F.A.J., M.A.Q., S.A.A., K.R.A., M.A., H.M.A. and F.J.; Supervision and manuscript major revision, F.J.; Project administration, N.M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IRB: 2021-09-026, 8 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study via the concerned hospital as highlighted “Institutional Review Board Statement”.

Data Availability Statement

Data were obtained from King Fahd Hospital of Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University and are available from the authors with the permission of King Fahd Hospital of the University.

Acknowledgments

First: we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to God, the Almighty, for showering us with blessings during our research work, enabling us to conclude the research successfully. Furthermore, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to Nida Aslam for her guidance and help with the methodology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Health Days 2020—World Cancer Day. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/HealthDay/2020/Pages/HealthDay-2020-02-04.aspx (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- استشارية أشعة لـ عكاظ: %10 وراثة سرطان الثدي.. والشرقية تتصدر في الإصابات—أخبار السعودية | صحيقة عكاظ. Available online: https://www.okaz.com.sa/news/local/2043496 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/wh/Breast-Cancer/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Marmot, M.G.; Altman, D.G.; Cameron, D.A.; Dewar, J.A.; Thompson, S.G.; Wilcox, M. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: An independent review. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2205–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant, M.; Allemani, C.; Berrino, F.; Coleman, M.P.; Aareleid, T.; Chaplain, G.; Coebergh, J.W.; Colonna, M.; Crosignani, P.; Danzon, A.; et al. Breast Carcinoma Survival in Europe and the United States: A Population-Based Study. Cancer 2004, 100, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]