Abstract

Quantum melting is the phenomenon of cold (zero-temperature) melting of a pressure-ionized substance which represents a lattice of bare ions immersed in the background of free electrons, i.e., the so-called one-component plasma (OCP). It occurs when the compression of the substance corresponds to the zero-point fluctuations of its ions being so large that the ionic ordered state can no longer exist. Quantum melting corresponds to the classical melting curve reaching a turnaround point beyond which it starts going down and eventually terminates, when zero temperature is reached, at some critical density. This phenomenon, as well as the opposite phenomenon of quantum crystallization, may occur in dense stellar objects such as white dwarfs, and may play an important role in their evolution that requires a reliable thermoelasticity model for proper physical description. Here we suggest a modification of our unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model in the region of quantum melting, and derive the corresponding Grüneisen parameters. We demonstrate how the new functional form for the cold shear modulus can be combined with a known equation of state. One of the constituents of the new model is the melting curve of OCP crystal which we also present. The inclusion of quantum melting implies that the modified model becomes applicable in the entire density range of the existence of the solid state, up to the critical density of quantum melting above which the solid state does not exist. Our approach can be generalized to model melting curves and cold shear moduli of different solid phases of a multi-phase material over the corresponding ranges of mechanical stability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Quantum Melting

Classical melting curve, the melting temperature as a function of density, is ever-rising. In reality, at extremely large densities, the phenomenon of quantum melting is theoretically predicted to occur [1]: the classical melting curve will turn around, go down, and terminate when zero temperature is reached. In other words, there is a transition from a solid to a liquid at at extreme compressions. It happens because of the quantum delocalization of electrons, since the electron vibrational energy increases with electron density as while the binding energy increases only as [2]. One can also associate quantum melting with the classical Lindemann picture: when the substance is compressed so much that the ratio of the amplitude of the zero-point fluctuations of ions to the average inter-ionic distance reaches some threshold value [1]), the ionic ordered state can no longer exist, thus the system is liquid at any density larger than the critical one. Recently the two-dimensional (2D) analog of quantum melting was detected experimentally in a 2D electron system at very low temperatures (25 mK) and high magnetic field (8 T) in a hole-doped GaAs quantum well [3]. Both the formation of a 2D ordered structure (the so-called Wigner electron lattice) and its subsequent transformation into a more disordered structure (an electron fluid), that is, quantum melting, was directly observed.

In the three-dimensional case, the phenomenon of quantum melting is usually studied theoretically, and in this work we will carry out such theoretical study in the one-component plasma (OCP) model of a material, which consists of some type of charged particles (atomic nuclei, for example) immersed into a rigid neutrlizing background of electrons which makes the system electrically neutral but does not screen Coulomb interactions between the charged particles.

As discussed in more detail below, quantum melting, as well as the opposite phenomenon of quantum crystallization, may occur in dense stellar objects such as white dwarfs, and may play an important role in their evolution that requires a reliable thermoelasticity model for a proper physical description. Here we suggest a modification of our own unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model in the region of quantum melting. We start with a brief review of this thermoelasticity model.

1.2. Unified Analytic Melt-Shear Thermoelasticity Model

Unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model describes both the melting temperature and cold () shear modulus of a solid substance as functions of density () at all densities and all temperatures from zero to Such model is required for multiple applications including constitutive modeling for plastic deformations at extremes of temperature and pressure numerical calculations of elastic and shock wave propagation, and even calculations of the oscillations of low-mass astrophysical objects. The original version of the model was introduced by ourselves in 2003–2004 [4,5] and is based on the analytic model for the Grüneisen parameter,

where the parameters , , and q can be determined from ambient data by solving a system of three algebraic equations [4,5]. Equation (1) in conjunction with

and

yields

and

where two s are conveniently chosen reference densities, usually those that correspond to for and to the ambient melting point for Then is given by the Preston-Wallace [6] model:

The thermoelastic softening parameter may be density dependent. Note that when i.e., density-independent, and G along the solidus approximately satisfy the relation [4,7,8]

for arbitrary The model can be constructed for any substance, and is applicable at any and any A table containing model parameters for 28 elemental solids and 4 alloys can be found in Ref. [9].

For polymorphic (multi-phase) materials, the --q values for the ambient solid structure may differ significantly from those for the high-P structure(s), and therefore the model may fail in its description of those high-P structure(s). The case of a multi-phase solid was considered in detail in Ref. [10]. In this case, the above equations are replaced with

and

where

and

Hence, in contrast to the previous case where a set of parameters describes both G and for a polymorphic material they are described by their own individual sets: for G and for In this case the only common parameters of G and is [10]

where Z is the atomic number of the material. This stems from the fact that, if two different s are introduced for G and separately, fitting to the set of 32 values of the corresponding leads to [9] while [10]; therefore

Then, in view of (8), (9),

where and are the corresponding reference densities, usually taken as those at ambient P. Just as for the original model, once the value of is fixed the values of the remaining pairs of parameters for both G ( and ) and ( and ) can be determined from solving a system of two algebraic equations containing the corresponding ambient data (see Ref. [10] for more detail).

Note that, since in a general case neither Equation (7) nor its counterpart (as follows from (4), (5))

holds. However, as Therefore, in this limit both Equations (7) and (15) hold. The validity of (15) also follows from (8), (9) with

It is the thermoelasticity model of a polymorphic material that will be modified in the region of quantum melting. This modification is the subject of what follows.

2. Methods

Below we briefly review the thermodynamics of cold OCP the essential features of which will be used in our further development of the unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model in the region of quantum melting. We will follow Ref. [11].

2.1. Cold Free Electron Gas

For the electron subsystem alone, usually two parameters are introduced, the (dimensionless) density parameter, and the average number density (number of particles per unit volume), related to each other via

The average energy per electron, is the sum of the three terms,

where

Here is the average zero-point kinetic energy, and and are the Fermi momentum and Fermi energy, respectively. is the well-known expression for the electron “exchange energy”:

while all higher order terms are lumped into the “correlation energy” the calculation of which is model dependent.

2.2. Electron and Ion Subsystems Combined

Now consider the actual substance at with (mass) density composed of nuclei of mass number A and atomic charge (atomic number Z), by combining its electron and ion subsystems. Let n be the average number density of electrons, and the dimensionless density parameter defined analogously to s above:

so that

Here measures the mean inter-electron distance in the units of the Bohr radius.

If M is the mass of the charged particles (protons) and their charge, then is the length scale (the ion Bohr radius), and Ry the energy scale (the usual rydbergs for electrons). M is related to A as

The coupling parameter of a quantum ion-electron plasma reads

where is the ion Fermi energy and a the mean inter-ionic distance. It then follows from (16) and (17) that

With one finally obtains

2.3. Quantum Melting of OCP

The melting of OCP was addressed in several studies using quantum Path-Integral Monte Carlo (PICM) simulations. Two distinct regimes were identified which convert to each other smoothly. First, classical melting regime: the melting of non-degenerate ions in low-density limit In this regime the (classical) melting curve is increasing normally and is defined by the (classical) OCP coupling parameter

such that along the melting curve [12] (and references therein). Hence, the equation for the classical OCP melting curve is

Second, cold quantum melting regime: the melting of highly degenerate ions in high-density limit In this regime the melting curve reaches the turnaround point and goes down; the thermodynamics properties depend solely on which is the quantum OCP coupling parameter.

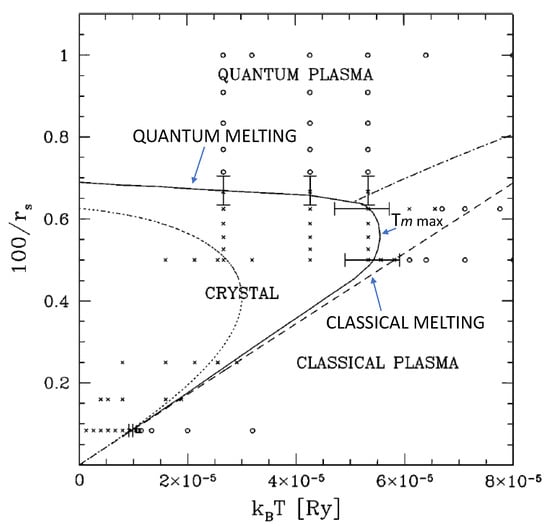

Figure 1 shows the phase diagram of OCP. The two regimes discussed above are clearly distinguishable. The turnaround point of the OCP melting curve corresponds to the maximum melting point

Figure 1.

The phase diagram of OCP. The datapoints with error bars and the solid line as their best fit come from PIMC simulations of Ref. [13]. The short-dashed line represents the results of the theoretical calculations of Ref. [14]. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Ref. [13]; APS Reuse and Permissions License RNP/22/NOV/059640 of 2 November 2022.

The OCP melting curves based on the results of [13,14] have different from each other by a factor of ∼2; nonetheless, they converge on the critical value of (the termination point of the melting curve) of or It was independently established [15] that at the critical density for the quantum melting for bosons and for fermions. The above OCP value of is consistent with boson’s

Ref. [13] does not offer a functional form for the best fit to the PIMC data. In the absence of a consistent theory of OCP that, if existed, would describe its entire melting curve analytically, we have to suggest the analytic form of the OCP melting curve based on the relevant physical arguments. Such arguments are: (i) the OCP melting curve terminates (hits zero) at a critical density that corresponds to some critical in Figure 1, (ii) it is a function of which is (iii) singular at the singularity is related to quantum melting. This point is discussed in more detail in Conclusions. Thus, the following (simplest analytic) functional form immediately suggests itself:

where is the classical OCP melting curve defined in Equation (21). The main features of the above functional form is that does terminate at and does exhibit a singularity as its derivative diverges. Now, the best fit to the data brings up the value of Before we carry out our own fitting, let us rewrite in a more suitable form. As follows from Equations (19) and (21),

Hence, we look for the best fit to the PIMC data of Ref. [13] of the functional form

With the best fit of the above form leads to

The turnaround point corresponds to the solution of i.e.,

Hence, Note that in Figure 1 the maximum melting temperature corresponds to The plot of Equation (24) with virtually coincides with the solid line in Figure 1.

With Equation (19) leads to

The maximum melting temperature corresponds to density associated with The use of (26) in Equation (19) gives

Then, the value of is i.e.,

Our value of is consistent with that of Ref. [14]: (for bosons, and ≈15,000 for fermions).

3. Results

We are now ready to add quantum melting to the unified analytic melt-shear model discussed in Introduction.

3.1. Quantum Melting Added to the Unified Analytic Melt-Shear Model

In view of the results of the previous section on the entire melting curve of OCP with its both classical and quantum segments combined, and taking into account the fact that in the limit the melting curve of the unified analytic melt-shear model, Equation (14), smoothly converts to the classical OCP melting curve (21) (having the correct prefactor of in the formula for in the limit is one of the conditions on the parameters and (with fixed), the entire melting curve having both classical and quantum segments combined is

with from (25) and from (27), where is the (classical) model melting curve (14). Indeed, since scales with in view of (19), the analogs of formulas (22)–(24) in terms of are those in which is replaced with Thus,

Equation (31) is the entire melting curve of a solid substance including the region of its quantum melting.

Let us derive the corresponding Grüneisen parameter. As follows from (9),

where is the (classical) Grüneisen parameter (11).

The maximum melting T corresponds to the solution of or Hence, at that corresponds to At densities the second and third terms of are negligibly small (that is, ). Hence, in view of (32), reduces to

or

With from (25) and from (27), Equation (34) gives in agreement with (28) obtained based on the corresponding values of and

We can now repeat the above procedure for the cold shear modulus and suggest its modification because of quantum melting. First, we have to choose the corresponding critical density at which the cold shear modulus terminates. The most obvious choice is that the critical density for cold G is the same as that for , i.e., Indeed, if it were larger than then, since terminates at and only liquid exists at higher density, there would have been a density region in which liquid has a non-zero shear modulus, apparently quite an unphysical situation. If it were smaller than there would have been a density region in which a solid has zero shear modulus, as unphysical situation as the previous one. Thus, the critial density for both G and must be the same.

Second, we have to choose the exponents in the formula analogous to Equation (30). In the absence of the corresponding theory that would guide us as regards this choice we make the assumption that the corresponding exponents are exactly the same as for , i.e.,

where is the (classical) model shear modulus (13). Formula (35) implies that the relation (15) is exact, i.e., The constancy of this combination of G and derives in the dislocation-mediated melting model and is the main signature of this model [16] based on which the original unified analytic melt-shear model was developed [4]. The assumption that the behavior of G is exactly the same as that of implies the identical assumption that dislocation melting mechanism operates in OCP. In fact, if was demonstrated in Ref. [17] that dislocation-mediated melting model describes the melting of alkali metals and reproduces its main features such as the values, dislocation densities at melt, etc. With respect to many of its physical properties, an alkali metal can be regarded as a body-centered cubic (bcc) lattice of point positive ions in a uniform background of free electrons, i.e., a one-component plasma. Indeed, it is well known that the deviations of alkali-metal Fermi surfaces from perfect spheres are of order 1% or less, clear evidence that the valence electrons are very nearly free. In addition, the ratio of ionic radius to half the interatomic distance increases from 0.4 in Li to only 0.7 in Cs [17], hence the overlap between alkali ions is small, and so to a good approximation the ions are effectively point charges. Hence, alkali metals do represent a good approximation of OCP. Therefore, if dislocation-mediated melting mechanism operates in alkali metals, it may well operate in the actual OCP, which fully justifies our choice of the corresponding exponents in Equation (35).

Then, as in the case of considered above,

which is the entire cold shear modulus of a solid substance including the region of its quantum melting.

The corresponding Grüneisen parameter comes from Equation (8):

where is the (classical) Grüneisen parameter (10). The maximum value of G corresponds to the solution of or Again, as in the case of at densities the second and third terms of are negligibly small (that is, ). Hence, reduces to

or

With from (25) and from (27), Equation (39) gives

Since [10]

To conclude this section, we estimate the value of where is the OCP molar volume that corresponds to the density region For this estimate we take with Then, using (29) and (42),

The corresponding value of where Pa cm/K is the Boltzmann constant and is the atomic volume that corresponds to being the Avogadro number, is therefore

Note that this value of is consistent with that of where is the ambient melting point, tabulated in Ref. [4] for 22 elemental solids; all the 22 values lie in the interval (more specifically, for 11 bcc solids and for 11 face-centered cubic (fcc) ones).

Table 1 summarizes the values of the five parameters associated with the unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model in the limit of quantum melting. We note that the two of them related to appear here for the first time; the other three are consistent with independent theoretical calculations as discussed above.

Table 1.

Five parameters associated with the unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model in the limit of quantum melting.

3.2. Quantum Melting Added to the Unified Analytic Cold EOS-Shear Modulus Model

Now we can add quantum melting to the unified analytic cold equation of state (EOS)-shear modulus model developed in Refs. [5,9,18] in which the shear modulus part of the unified melt-shear model discussed above is combined with the cold EOS. This is done based on the following relation for cold bulk and shear moduli (subscript “c” refers to is identical to in Equation (13)) [9,18]:

where is the cold bulk modulus. In Equation (45), and where is some (fixed) density. It then follows from Equations (8) and (45) that

which is the modified Slater-Dugdale-MacDonald-Vashchenko-Zubarev formula of ref. [18]. Note that the Grüneisen in (46) is identical to that in Equation (10) [9,18]. In what follows we discuss a practical example of the unified analytic cold EOS-shear modulus model with the inclusion of quantum melting.

4. Discussion

4.1. Unified Analytic Cold EOS-Shear Modulus Model with Holzapfel’s EOS

Here we illustrate the inclusion of quantum melting in the cold EOS-shear modulus model using a well-known example of a cold EOS. We note that quantum melting can be included in this model with any cold EOS, because for any cold EOS the corresponding analytic form of can be easily found from solving the differential Equation (46) with from Equation (37).

As our example of the inclusion of quantum melting in the cold EOS-shear modulus model, consider Holzapfel’s cold EOS which is widely used in high-pressure studies since it has the correct ultrahigh-pressure limiting form [5] . Holzapfel’s EOS is

Note that a cold EOS should not terminate at the critical density of quantum melting because, in principle, it can describe the cold liquid phase at densities above the critical one. In other words, in contrast to either shear modulus or melting curve, a cold EOS can be continuous across quantum melting. With

and from (47), Equation (46) yields identical to in Equation (37) which, being used in Equation (8), yields identical to that in Equation (36). Adding Equation (31) for the corresponding melting curve to Equations (36) and (45)–(48) will constitute unified analytic EOS-melt-shear model with quantum melting (in our case of Holzapfel’s EOS; any other EOS can be used instead, for which the analytic form of Equation (48), will be modified appropriately).

4.2. Example: Beryllium

Consider beryllium () as an example of the application of quantum melting to a real material. In this case Equation (27) gives g/cc. The corresponding values of and are, respectively, g/cm g/cm GPa and K. The values of the five parameters used in the analytic form of , Equation (13), come from the ambient data on Be found in the literature and are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Five parameters of the unified analytic melt-shear thermoelasticity model of Be associated with its shear modulus.

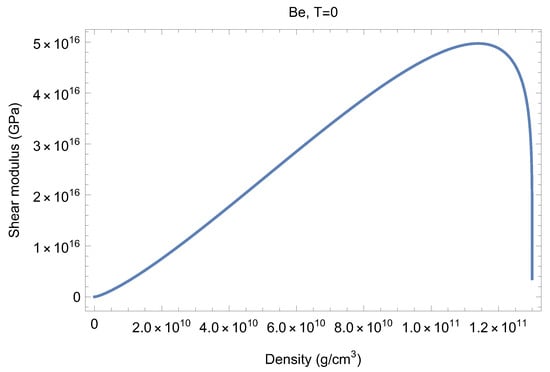

The cold shear modulus of Be in the unified analytic melt-shear model with quantum melting included is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The cold G of Be in the unified analytic melt-shear model with quantum melting included. G terminates at a critical density of g/cm.

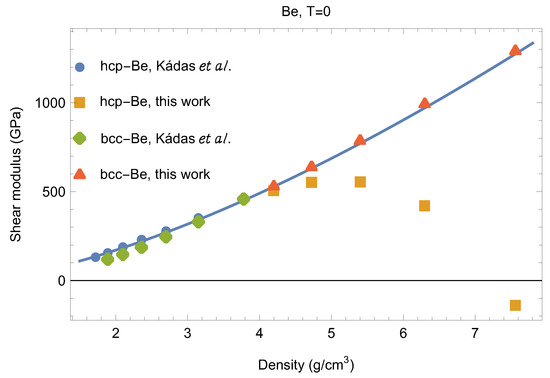

Figure 3 details the previous figure as its lower-density portion. It compares the unified analytic melt-shear model with quantum melting included to the theoretical calculatons on the cold G of Be. Specifically, the values of cold G for both hcp-Be and bcc-Be were both calculated by ourselves using first principles based software VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulations Package) and are taken from Refs. [19,20] as independent theoretical calculations on hcp-Be and bcc-Be, respectively.

Figure 3.

The lower-density portion of Figure 2: the cold G of Be in the unified analytic melt-shear model with quantum melting included (blue curve) vs. the theoretical caluclations described in the text.

5. Conclusions

We have presented the modification of the unified analytic melt-shear model of a multi-phase material by the inclusion of quantum melting, and derived new analytic forms for the melting temperature, cold shear modulus, and the corresponding Grüneisen parameters as functions of density including the density region of quantum melting. We have demonstrated how the new analytic form for the cold G combines with EOS in the unified analytic cold EOS-shear modulus model, on an example of a known EOS, namely, Holzapfel’s one. The modification of the unified analytic melt-shear model by the inclusion of quantum melting implies that the modified model becomes applicable in the entire density range of the existence of the solid state, up to the critical density of quantum melting above which the solid state does not exist. Our approach can be generalized to model melting curves and cold shear moduli of different solid phases of a multi-phase material over the corresponding ranges of mechanical stability; for instance, hcp-Be in Figure 3 is mechanically unstable at densities larger than g/cm This will be the subject of further studies.

In addition to formulas for and already discussed in the literature before, we have derived the formulas for and Equations (40) and (42). We have also obtained the analytic form of the melting curve of OCP, Equations (21) and (30), which will be useful for numerous applications associated with the thermodynamics of stellar objects.

The new unified analytic melt-shear model with quantum melting included can be used to analyze physical phenomena in white dwarfs and other dense stellar objects. As noted by Mochkovitch and Hansen [21], deviations from the classical melting curve of OCP towards the region of quantum melting become significant for densities g/cm This corresponds to g/cm for a He white dwarf and g/cm for a C white dwarf. Since these white dwarfs can exits in nature, the phenomenon of quantum melting may occur in their cores. Another phenomenon, the opposite of quantum melting but ultimately related to it, namely, quantum crystallization, may play an important role in the evolution of dense stellar objects such as white dwarfs since the cooling rate for a white dwarf strongly depends on the phase of the matter in the star: whether free thermal motion (in a liquid) of lattice vibrations (in a solid) are the central cooling mechanism [22].

We will now dwell on one of the features of the new modified analytic melt-shear model. As follows from Equations (32) and (37) which describe Grüneisen function common to both G and as approaches i.e., this Grüneisen function diverges to minus infinity. In fact, starts going down from its classical limiting value of at densities much lower than at at a slightly higher etc. The divergence of a Grüneisen parameter at a cold quantum phase transition is a well-known phenomenon; see, e.g., Ref. [23] for a review, or a more recent Ref. [24] for the case of a symmetry-enhanced 1st-order quantum phase transition. Let us consider this phenomenon in some more detail.

The Mie-Grüneisen-Debye equation of state of a solid reads where E is the total energy, and the Grüneisen is identical to that in Equation (8) or Equation (46). Then

which transforms into

where is the thermal expansion coefficient, is the sound velocity (S being entropy), and is the (isobaric) specific heat. Thus, in or case of the quantum melting, the divergence of the Grüneisen function of a solid on approaching quantum melting is related to the divergence of the ratio at the critical density; in other words, the thermal expansion is more singular than the specific heat, which is indeed the case for quantum melting since, at the quantum critical point (QCP), the solid ceases to exist and, accordingly, its thermal expansion exhibits a singularity of becoming unidirectional: the solid does not exist at but only at hence, it cannot be “negatively” thermally expanded (i.e., contracted) past In other words, in this case the Grüneisen parameter diverges because the QCP has no characteristic energy which is being suppressed to zero by shutting down thermal expansion above the QCP. A similar behavior is observed in, e.g., the case of a magnetic-field-driven quantum phase transition on approaching the QCP from the ordered state [23]. Here the divergence occurs as the characteristic energy of the phase transition is suppressed to zero by the tuning parameter in such a way that, once again, the thermal expansion becomes more singular than the specific heat [23].

Author Contributions

Methodology, L.B. and D.L.P.; investigation, L.B. and D.L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, D.L.P.; project administration, D.L.P.; funding acquisition, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out under the auspices of the US DOE/NNSA.

Data Availability Statement

All the data discussed in this work are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Naftali Burakovsky who, while being a student at LANL, initiated the research presented in our work, and created the prototype of the unified analytic melt-shear model modified by the inclusion of quantum melting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kirzhnits, D.A. Extremal states of matter (ultrahigh pressures and temperatures). Sov. Phys. Uspekhi 1972, 14, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.A. Phase Diagrams of the Elements; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.; Hunt, B.M.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; West, K.W.; Ashoori, R.C. Sharp tunnelling resonance from the vibrations of an electronic Wigner crystal. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Greeff, C.W.; Preston, D.L. Analytic model of the shear modulus at all temperatures and densities. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 094107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L. Analytic model of the Grüneisen parameter at all densities. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2004, 65, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D.L.; Wallace, D.C. A model of the shear modulus. Solid State Commun. 1992, 81, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L. Analysis of dislocation mechanism for melting of elements. Solid State Commun. 2000, 115, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L.; Silbar, R.R. Melting as a dislocation-mediated phase transition. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 15011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L. Unified model of the Grüneisen parameter, melting temperature, and shear modulus. Recent Res. Dev. Phys. 2004, 5, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Burakovsky, L.; Luscher, D.J.; Preston, D.; Sjue, S.; Vaughan, D. Generalization of the unified analytic melt-shear model to multi-phase materials: Molybdenum as an example. Crystals 2019, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpeter, E.E.; Zapolsky, H.S. Theoretical high-pressure equations of state including correlation energy. Phys. Rev. 1967, 158, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabrier, G.; Douchin, F.; Potekhin, A.Y. Dense astrophysical plasmas. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Ceperley, D.M. Crystallization of the one-component plasma at finite temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabrier, G. Quantum effects in dense Coulombic matter—Application to the cooling of white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 1993, 414, 695. [Google Scholar]

- Ceperley, D.M.; Alder, B.J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L.; Silbar, R.R. Analysis of dislocation mechanism for melting of elements: Pressure dependence. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L. Dislocation-mediated melting: The one-component plasma limit. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 63, 067402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burakovsky, L.; Preston, D.L.; Wang, Y. Cold shear modulus and Grüneisen parameter at all densities. Solid State Commun. 2004, 132, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádas, K.; Vitos, L.; Ahuja, R.; Johansson, B.; Kollár, J. Temperature-dependent elastic properties of α-beryllium from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 235109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádas, K.; Vitos, L.; Johansson, B.; Kollár, J. Structural stability of β-beryllium. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 035132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochkovitch, R.; Hansen, J.P. Fluid-solid coexistence curve of dense coulombic matter. Phys. Lett. 1979, 73A, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpeter, E.E. Energy and pressure of a zero-temperature plasma. Astrophys. J. 1961, 3, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandia, R.; Siegrist, T.; Besara, T.; Schmiedeshoff, G.M. Grüneisen divergence near the structural quantum phase transition in ScF3. Philos. Mag. 2019, 99, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneke, C.; Vojta, M. Divergence of the Grüneisen ratio at symmetry-enhanced first-order quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 174420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).