Abstract

Nowadays there is a growing interest among consumers for functional food products, and edible flowers could be a solution to fulfill this demand. Edible flowers have been used throughout the centuries for their pharmaceutical properties, but also in some areas for culinary purposes. There is a great variety of edible flowers, and numerous studies are available regarding their chemical composition and potential antioxidant and functional characteristics. Therefore, the present work focuses on gathering a vast amount of data regarding edible flowers. Phytochemical content, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content and antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP, ABTS, etc.) of more than 200 edible flowers are presented. The main phytochemicals belong to the groups of phenolic acids, flavonoids, carotenoids and tocols, while great variability is reported in their content. The present study could be a useful tool to select the edible flowers that can be served as sources of specific phytochemicals with increased antioxidant activity and evaluate them for their safety and potential application in food industry, during processing and storage.

Keywords:

edible flowers; phytochemicals; antioxidant; total phenolic content; total flavonoid content; DPPH; FRAP; ABTS 1. Introduction

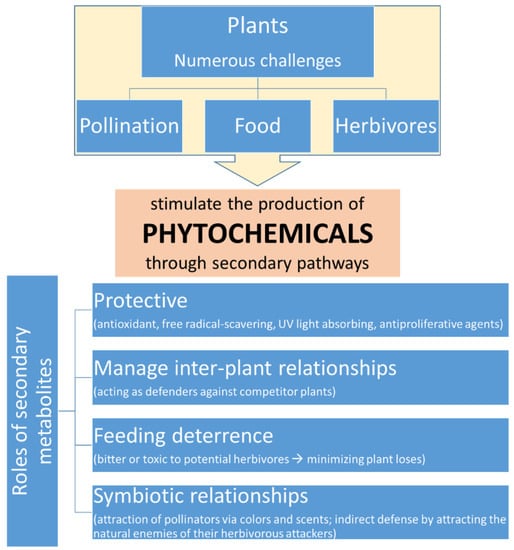

The word phytochemicals is derived from two Greek words “φυτό” and “χημικά”, which mean plants and chemicals, respectively. Therefore, phytochemicals are chemical compounds that are derived from plants. According to the most common definition, phytochemicals are defined as bioactive non-nutrient plant compounds in fruits, vegetables, grains, and other plant foods that have been linked to reducing the risk of major chronic diseases [1]. However, in plants they are produced through secondary biochemical pathways due to environmental stimulations and as a response to various challenges. They play several roles during all stages of plant growth and are essential for their survival (Figure 1) [2]. These roles may explain several characteristics and properties of phytochemicals such as their taste, color or even aroma. In the case of taste, phytochemicals may be bitter or even toxic (in interactions with nervous systems of animals) in order to limit their consumption from herbivores. Some of them present characteristic colors and aromas in order to attract the necessary pollinators or the enemies of herbivores by producing a mixture of phytochemicals as a response to tissue damage [2].

Figure 1.

Phytochemicals and their role in plants.

Flowers are parts of plants that also contain amounts of several phytochemicals, and therefore they have been used since ancient times for their potential therapeutic properties in medicine or for culinary purposes [3]. Nowadays, the results of several research studies support these potential health properties of edible flowers, known since ancient times. In addition, these studies concluded that it is mainly the antioxidant activities of such compounds that are responsible for these health benefits, since they are linked with the prevention of several diseases (Figure 2). Therefore, various recent review articles are available reporting the potential health benefits of phytochemicals from edible flowers [3,4,5,6].

Figure 2.

Potential health benefits linked with edible flowers.

Edible flowers are sources of a variety of bioactive compounds, and the most common include phenolic acids, flavonoids, carotenoids, tocols and terpene compounds. However, some other compounds in lower concentrations may also be detected, such as alkaloids, nitrogen-containing compounds and organosulfur compounds [7,8].

As already mentioned, there are several works available regarding the functional characteristics of edible flowers; however, the majority of them focus on the health benefits, and in some of them a brief description of the main compounds is presented [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The aim of the present study is to provide a detailed presentation of the main compounds detected in edible flowers and the possible antioxidant activity. In the present work, more than 200 edible flowers, analyzed in different studies, have been collected and presented.

This comprehensive review was based on a search in electronic databases such as Scopus and Google Scholar and related articles regarding edible flowers, as well as their total phenolic content and antioxidant activity. The keywords used were ‘edible flower’ and each one of the terms ‘antioxidant’, ‘total phenolic content’, ‘total flavonoid content’, ‘phenolic acids’, ‘flavonoids’, ‘carotenoids’, ‘tocols’ and ‘terpenes’, found in the title/abstract/keywords. Subsequently, a systematic review related to the phenolic compounds of edible flowers and their antioxidant properties was performed. An attempt was made to mainly include works from the last 5–10 years.

2. Phytochemicals

2.1. Phenolic Compounds

From a chemical point of view, phenolic compounds, or simply polyphenols, are compounds that possess at least an aromatic ring containing one or more hydroxyl groups and/or their functional derivatives such as esters, methyl esters, glycosides, etc. In edible flowers and in plants in general, they are mainly found as a conjugated form with one or more glucose residues joined to the hydroxyl groups or directly to an aromatic carbon resulting to glycosides (the main form found in nature) [9]. Phenolic compounds have numerous actions in the plant, participating in the mechanisms of growth, reproduction and plant protection [10]. However, they are well-known for their antioxidant activities in humans after consumption. In edible flowers, two main groups of phenolics are usually highlighted due to their bioactive potential and their content, namely phenolic acids (hydroxycinnamic and hydroxybenzoic acids) and flavonoids (flavones, flavanones, flavonols, flavanols and antocyanins) [4,6,7,8].

2.1.1. Total Phenolic Content

The most common and simple method for the estimation of total phenolic content (TPC) is the colorimetrical assay based on Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. However, this method usually overestimates the TPC of samples since all the compounds with an active hydroxyl group(s) may react with the reagent and give a positive result [11,12]. Such compounds, apart from the phenolics, include reducing sugars, ascorbic acid and others. Despite that, this method is the most commonly used, and therefore is the same method used for the extracts of edible flowers. The TPC of more than 200 edible flowers, expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per g in dry weight (DW) or fresh weight (FW), are presented in Table 1 and Table 2 [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Table 1.

Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g DW) of several edible flowers.

Table 2.

Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g FW) of several edible flowers.

In studies where TPC was expressed in DW, the highest values were reported for Rosa rugosa (312 mg GAE/g DW), Carpobrotus edulis (299 mg GAE/g DW), Rosa chinensis (285 mg GAE/g DW) and Rhododendron simsii Planch (250 mg GAE/g DW), while the lowest were reported for Agave salmiana and Aloe vera (4.6 mg GAE/g DW). In studies where TPC was expressed in FW, the highest values were reported for Rosa hybrid (35.8 mg GAE/g FW) and Limonium sinuatum (34.2 mg GAE/g FW), while the lowest were reported for Iris japonica (0.6 mg GAE/g FW) and Lilium candidum L. (0.9 mg GAE/g FW).

The results in Table 1 and Table 2, also revealed the main problem of TPC estimation through Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. This method is highly affected by the raw material, extraction method and duration of reaction for color development. Therefore, in some cases, almost identical results were obtained for the same flower, such as Matricaria recutita (26.5 mg GAE/g DW [20] and 26.4 mg GAE/g DW [18]); in other cases, a small difference occurred, such as Siraitia grosvenorii (12.8 mg GAE/g DW [20] and 22.2 mg GAE/g DW [18]); but completely different values may also be reported, such as Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (36.9 mg GAE/g DW [18] and 7.4 mg GAE/g DW [16]) and Tropaeolum majus (62.7 mg GAE/g DW [18] and 11.8 mg GAE/g DW [16]).

In the abovementioned studies, Rosa species are in the top five edible flowers with the highest TPC. Similar results with high TPC of Rosa species are also reported in other studies with edible flowers [22,23]. It is also interesting that the TPC of some edible flowers is higher than vegetables, common edible fruits and nontraditional tropical fruits reported in the literature [24,25].

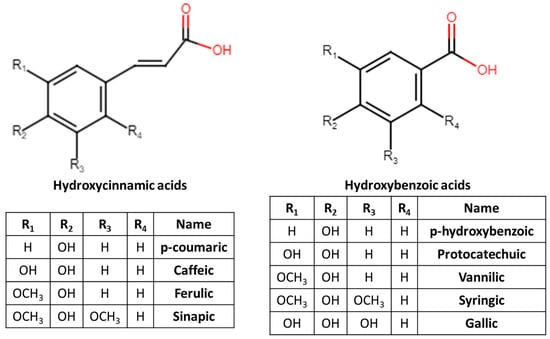

2.1.2. Phenolic Acids

Phenolic acids can be divided into two groups: the hydroxycinnamic acids, comprising a three-carbon side chain (C6–C3) structure (Table 3); and hydroxybenzoic acids, comprising a C6–C1 structure (Table 4), which can be found as free substances or conjugated (Figure 3) [10]. Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives include p-coumaric, caffeic, ferulic, sinapic and chlorogenic (5-O-caffeoylquinic acid) acids [1,8]. In the group of hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives belong, among others, p-hydroxybenzoic, protocatechuic, vanillic, syringic, ellagic and gallic acids [1,8]. They are usually part of a complex structure such as lignins and hydrolyzable tannins, but they can also be found in the form of sugar derivatives and organic acids [1]. Homogentisic acid has been detected in several edible flowers such as Bidens pilosa, Brunfelsia acuminata, Calliandra haematocephala, Chaenomeles sinensis, Dianthus caryophyllus, Dianthus chinensis, Flos chrysanthemi, Gerbera jamesonii Bolus, Gladiolus hybrids, Helianthus annuus, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, Ipomoea cairica, Jatropha integerrima, Lantana camara, Limonium sinuatum, Magnolia soulangeana, Malvaviscus arboreus, Orostachys fimbriatu, Osmanthus fragrans, Pelargonium hortorum, Rhapniolepis indica, Rhododendron simsii Planch, Rhoeo discolor, Rosa hybrid, Salvia splendens and Strelitzia reginae Aiton [13].

Table 3.

Major hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives detected in some edible flowers.

Table 4.

Major hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives detected in some edible flowers.

Figure 3.

The major hydroxycinnamic and hydroxybenzoic acids.

2.1.3. Flavonoids

Flavonoids, a class of low-molecular-weight phenolic compounds, are an important group of natural products, which are characteristic compounds and the largest group of secondary metabolites in plants [27]. In plants, flavonoids, as all the phenolic compounds, participate in the mechanisms of growth and protection. Many flavonoids are the main flower pigments in most plants. Flavonoids can be easily divided in several subgroups; however, this review will be focus on anthocyanins, flavones and flavanones, and flavanols and flavonols.

The total flavonoid content (TFC) of more than 100 edible flowers is presented in Table 5 and Table 6. The TFC of 65 edible flowers showed a wide variation from 0.7 to 85.3 mg CAE (catechin equivalents)/g DW, with a more than 120-fold difference. The highest TFC was reported in flowers of Osmanthus fragrans (85.3 mg CAE/g DW), Lonicera japonica (52.5 mg CAE/g DW), Coreopsis tinctoria (29.3 mg CAE/g DW), Helichrysum bracteatum (28.59 mg CAE/g DW) and Armeniaca mume (28.50 mg CAE/g DW). On the other hand, the lowest TFC was reported in Cucumis sativus Linn. (0.7 mg CAE/g DW), Hylocereus undatus (0.8 mg CAE/g DW) and Hemerocallis citrina (0.9 mg CAE/g DW). This study concluded that Chrysanthemum species may contain higher flavonoids than Rosa species [20].

Table 5.

Total flavonoid content (mg CAE/g DW) of several edible flowers [20].

Table 6.

Total flavonoid content (mg RE/g DW or mg QE/g DW) of several edible flowers.

The TFC of 23 edible flowers, expressed as mg rutin equivalents per gram of dry weight (mg RE/g DW) varied from 0.5 to 71.5 mg RE/g DW with a 159-fold difference. Osmanthus fragrans (Thunb.) Lour had the highest total flavonoid content (71.5 mg RE/g DW), followed by Lavandula angustifolia Mill (27.4 mg RE/g DW), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (18.8 mg RE/g DW), Perennial chamomile (16.0 mg RE/g DW) and Chamomilia (15.7 mg RE/g DW). Gomphrena globose Linn had the lowest TFC (0.5 mg RE/g DW), followed by Redartfulplum tea (0.7 mg RE/g DW) [18].

Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins and their derivatives are water-soluble flavonoids and natural pigments that are responsible for the color of flowers. Their color depends mainly on pH, but metal ion and copigments may also affect it. They are responsible mainly for the red, blue and purple color of flowers. The term anthocyanins is derived from two Greek words, anthos (flower) and cyano (blue), and therefore its meaning is “blue from flowers”. Anthocyanins and their color in flowers play a significant role in plants since they are responsible for the correct pollination. The color of flowers is necessary to attract the pollinators (birds and insects). In addition, for humans, anthocyanins have been correlated with plants with increased antioxidant activity and therefore with high nutritional value. Anthocyanins are present in nature mainly in their aglycon form, also called anthocyanidin. There are six common anthocyanidins, namely pelargonidin, cyanidin, delphinidin, peonidin, petunidin and malvidin, which are linked to one or more glycosidic units [28].

The variations in qualitative and quantitative composition of anthocyanidins are responsible for the variations of colors in flowers, even among the different cultivars of the same species [5,7]. In general, specific anthocyanidins have been correlated with specific colors in flowers. For example, pelarginidin is scarlet and delphinidin is more bluish. Therefore, the anthocyanidins of pink, scarlet, red, red-purple and magenta flowers are cyanidin and/or pelargonidin with or without peonidin, while in cyanic flowers, which are purple, violet and blue, mainly the anthocyanidins, delphinidin and its methylated derivatives, petunidin and malvidin are present [29]. In addition, regarding the total anthocyanin content (TAC), there is a small correlation with the flower color (blue = red > rose > yellow = orange > white) [30]. In the case of Hibiscus syriacus L., the red flowers presented higher TAC than purple and pink, with values of 3.2 mg/g, 1.87 mg/g and 1.61 mg/g (DW), respectively [31]. Benvenuti et al. [30] studied twelve species of cultivated edible flowers and reported the presence of a high TAC up to 14.4 mg cyn-3-glu eq./100 g FW and large variation from 0.35 to 14.4 mg cyn-3-glu eq./100 g FW. The highest concentrations (as mg cyn-3-glu eq./100 g FW) were reported for flowers from Petunia × hybrid (red 14.4 mg/100 g; rose 12.9 mg/100 g), Viola × wittrockiana (blue 13.6 mg/100 g; red 12.4 mg/100 g), Dianthus × barbatus (red 13.4 mg/100 g; rose 10.6 mg/100 g), and Pelargonium peltatum (red 12.5 mg/100 g), while the lowest were reported in white or orange flowers such as Tagetes erecta (orange 0.75 mg/100 g), Viola × wittrockiana (white 0.35 mg/100 g), Dianthus × barbatus (white 0.73 mg/100 g) and Calendula officinalis (orange 0.47/mg 100 g). In addition, Janarny et al. [32] studied twenty-eight species of fresh edible flowers from Sri Lanka using the pH differential method. Concentrations higher than 100 mg cyn-3-glu eq./100 g DW were reported for flowers from Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (200 mg/100 g), Carrica papaya (140 mg/100 g), Punica granatum (118 mg/100 g) and Ixora coccinea (157 mg/100 g), while the lowest concentrations below 3 mg cyn-3-glu eq./100 g DW were reported for flowers from Cassia auriculata, Duriozibethinus, Calendula officinalis (2 mg/100 g), Musa spp (0.8 mg/100 g) and Madhuca longifolia (0.6 mg/100 g).

Some extracts from edible flowers presented important contents of total anthocyanins, and therefore they have been proposed for potential applications in the food industry both for natural colorants and antioxidants. The ethanolic extract (0.01% HCl in 50% ethanol) of Titanbicus (a hybrid of Hibiscus moscheutos × H. coccineus (Medic.) Walt.) flowers presented total monomeric anthocyanin content (mg Cy3-G/g extract) of 2.7 mg/g for Artemis (white/pink), 6.0 mg/g for Rhea (pink) and 47.1 mg/g for Adonis (red) [33]. Furthermore, the ethanolic extracts of Viola wittrockiana and Antirrhinum majus flowers were 5.7 and 0.3 (µg/mg DW), respectively [34].

Flavones and Flavanones

Flavones and flavanones are two classes of flavonoids present in edible flowers. Flavanones have the structure of 2,3-dihydroflavone, but without a double bond between C2 and C3, making C2 chiral. On the other hand, flavones contain the double bond between C2 and C3 [8]. In edible flowers, flavanones such as hesperidin, naringenin, isosacuratenin, heridictol and their derivatives and flavones such as luteolin, apigenin, acacetin, chrysoeriol and their glucosides have been detected (Table 7).

Flavones, in addition to their functions to help plants to adapt to their surrounding environment, have been also correlated with numerous health benefits in humans, including antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer activities [35]. Among 70 edible flower samples in China, flavones were only detected in seven, and mainly apigenin [36]. The highest content was detected in Tropaeolum majus (53.6 μg/g DW apigenin), followed by Helichrysum bracteatum (10.4 μg/g DW apigenin and 7.4 μg/g DW chrysin) and Matthiola incana (10.9 μg/g DW apigenin). Flavanones derived from edible flowers have been correlated with potential antiaging properties. More specifically, flavanones such as hesperetin, hesperidin, neohesperidin and naringin have been extensively studied for their antiaging properties [37]. In general, flavanones, and especially hesperidin and hesperetin, have been correlated with several health benefits [38]. In a study of the phenolic composition of edible flowers of distinct colors used in foods and drinks, hesperidin and naringenin were the main flavanones [39]. The highest content of flavanones was detected in Cosmos sulphureus Cav. (yellow color and 1661 μg/g FW) and the lowest in Begonia × tuberhybrida Voss. (light red color and 3.7 μg/g FW). Cosmos sulphureus Cav., Clitoria ternatea L. and Dianthus chinensis L. were the edible flowers with the highest content of both flavanones (hesperidin and naringenin). However, the same study reported a low bioaccessibility of these flavanones compared to other phenolic compounds, with the highest value of 11% detected in Dianthus chinensis L. It is well-known that hesperidin, as a rutinoside, is more difficult to be absorbed, compared to hesperitin, which can be absorbed directly in the small intestine. Hesperidin should be first fermented by the intestinal microorganisms in order to become more easily absorbed. The flavanone composition of 70 edible flowers from China revealed mainly hesperitin (up to 2162 μg/g DW), naringin (up to 28,001 μg/g DW) and naringenin (up to 1187 μg/g DW) [36]. Hesperitin was detected in the majority of edible flowers, followed by naringin and naringenin. However, among the 70 flower samples, hesperitin was only detected in seven, naringin in four, and naringenin in three.

Table 7.

Major flavones and flavanones detected in several edible flowers.

Table 7.

Major flavones and flavanones detected in several edible flowers.

| Flavones/Flavanones (and Their Derivatives) | Flower | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acacetin | Chrysanthemum morifolium | [40] |

| Apigenin | Chrysanthemum indicum L., Chrysanthemum lavandulifolium, Chrysanthemum morifolium, Clitoria ternatea L., Florists chrysanthemum, Helichrysum bracteatum, Matthiola incana, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Rosa rugose, Tagetes erecta L., Tropaeolum majus | [36,41,42] |

| Chrysoeriol | Tree peony flowers, Hemerocallis fulva | [43,44] |

| Chrysin | Chrysanthemum morifolium, Helichrysum bracteatum | [36] |

| Eriodictyol | Fengdan Bai (tree peony), Impatiens walleriana, Chrysanthemum morifolium | [45,46,47] |

| Hesperetin | Amygdalus persica, Chrysanthemum indicum, Chrysanthemum lavandulifolium, Chrysanthemum morifolium, Citrus aurantium L., Gomphrena globose, Hylocereus undatus, Musa basjoo Sieb. et Zucc. | [36,48] |

| Hesperidin | Citrus aurantium L., Rosa chinensis, Torenia fournieri, Clitoria ternatea L. | [39,48] |

| Luteolin | Chrysanthemum indicum L., Chrysanthemum morifolium, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Lonicera japonica Thunb., Viburnum inopinatum | [41,47,49,50] |

| Naringenin | Amygdalus persica, Helichrysum bracteatum, Nymphaea hybrid, Begonia × tuberhybrida Voss., Rosa chinensis, Torenia fournieri, Clitoria ternatea L. | [36,39] |

| Naringin | Citrus aurantium, Rhododendron simsii Planch, Rosa chinensis, Nymphaea hybrid | [36] |

Flavonols

Flavonols are usually the group of flavonoids with the higher content in edible flowers, even among total phenolic compounds [7,51]. This group of flavonoids has a double bond between C2 and C3 and a carbonyl at C4. Glycosylation normally occurs at C3 as mono-, di-, or triglycosides, while there is also the possibility for glucuronidation [10]. The most frequently determined flavonols in edible flowers are quercetin, quercitrin and isoquercitrin, hyperoside, rutin and other quercetin derivatives, kaempherol and its derivatives, isorhamnetin and its derivatives and myricetin and its derivatives (Table 8). Although almost all flowers present high (>2200 mg/100g Dianthus pavonius) or low concentrations of flavonols (<1 mg/100 g), according to Demasi et al., [17], flowers of Centaurea cyanus (0.9 mg/100 g), Taraxacum officinale (1.8 mg/100 g), Tagetes patula (0.5 mg/100 g) and Calendula officinalis (1.7 mg/100 g), are very poor in flavonols, while in flowers of Bellis perennis, Salvia pratensis and Borago officinalis, flavonols are lacking completely. In the same study, quercitrin was the main flavonol in Rosa pendulin, Robinia pseudoacacia and Tropaeolum majus; quercetin in Leucanthemum vulgare, Paeonia officinalis and Rosa canina; and isoquercitrin in Dianthus pavonius, Geranium sylvaticum, Lavandula angustifolia, Leucanthemum vulgare, Mentha aquatic and Rosa canina.

Table 8.

Major flavonols detected in some edible flowers.

Flavanols

The major flavanols detected in edible flowers are catechin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, epicatechin gallate and epigallocatechine gallate. There is no double bond in flavanols between C2 and C3 and no carbonyl in the ring C (C4), resulting in two chiral carbons (C2 and C3), and therefore four possible diastereomers: (+)-catechin (2R,3S), (-)-catechin (2S,3R), (+)-epicatechin (2R,3R) and (-)-epicatechin (2S,3S) [10]. Flavanols are the compounds that have been detected in the majority of edible flowers and especially the two main representatives of the group catechin and epicatechin (Table 9). In a study with 26 edible flowers, only 5 presented very low content of flavanols, namely Dianthus carthusianorum, Leucanthemum vulgare, Taraxacum officinale, Trifolium alpinum and Calendula officinalis, while in Borago officinalis no flavanols were detected [17]. In addition, in the majority of cases, epicatechin prevailed on catechin. Among the health benefits that have been associated with the consumption of these two flavanols are the decrease in body mass index [64], the prevention of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases by improving the blood flow and the exertion of antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic properties [65].

Table 9.

Edible flowers with important content of catechin and epicatechin [13,17,18].

2.2. Carotenoids

Carotenoids are the most widely distributed pigments in nature, with yellow, orange, red and even purple colors. They are lipophilic isoprenoid pigments that are synthesized by photosynthetic organisms (algae, plants, cyanobacteria) but are also present in some bacteria, fungi and animals. They are present in leaves, but they observed mainly in autumn when chlorophylls are degraded, providing the orange-like color to them. Humans, like the majority of animals, cannot synthesize them, and therefore they take them through their diet by consuming plants. The Carotenoids Database [66] currently provides information on 1204 natural carotenoids in 722 source organisms, and these numbers continuously increase. The majority of them, based on C number, belong to the C40 group (>93%), although carotenoids with C30, C45 and C50 also occur. Carotenoids are classified into two main groups: the carotenes that are formed exclusively by carbon and hydrogen atoms, and the xanthophylls that contain oxygen. Some characteristic examples of the first group are α-carotene, β-carotene and lycopene, while in the latter are lutein, zeaxanthin, astaxanthin, fucoxanthin and peridinin [67,68]. In plants, carotenoids play essential roles in photosynthesis and photoprotection. In humans, their consumption is very important since they are precursors of vitamin A and they have been linked with several beneficial functions in human health such as eye, brain and heart health, cancer prevention, maternal and infant nutrition, skin-UV protection, fertility, immune modulation/stimulation, etc. [69].

In the case of U. leptophylla from Costa Rica, petioles presented the highest content of carotenoids (16.1 mg/100 g DW) followed by stems (14.9 mg/100 g DW) and flowers (12.4 mg/100 g DW). In the case of flowers, lutein was the major compound (9.3 mg/100 g DW) followed by β-carotene (1.8 mg/100 g DW), but zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin and α-carotene were also detected in lower concentrations [70]. In a recent study with flowers of Helichrysum italicum subsp. Picardii Franco, a carotenoid content of 6.79 mg/100 g DW was reported [71]. Similar values (5.8 mg/100 DW) were reported in the case of Centaurea cyanus [72]. Higher values (24.7 mg/100 g DW) were reported for the flowers of Camellia japonica, and even higher (181.4 mg/100 g DW) for Borago officinalis [72]. Finally, a correlation between color of flower and total carotenoid content was reported in the case of flowers of Viola × wittrockiana (pansies; white 21.6, yellow 58.0 and red 109.2 mg/100 g DW) [72].

2.3. Tocols

Tocols are a group of compounds that includes tocopherols (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol) and tocotrienols (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocotrienol) and they are synthesized only by plants and photosynthetic microorganisms. They are well-known for their antioxidant activity and their linkage with vitamin E. Although all of them are considered part of the vitamin E group [73], only α-tocopherol has been tested and shown to prevent vitamin E deficiency disease, and therefore only α-tocopherol can be called vitamin E [74]. They contain a polar chromanol ring linked to an isoprenoid-derived hydrocarbon chain, and the presence of the phenolic hydroxyl group provides their antioxidant activity [75]. This antioxidant activity is based on the ability to stop the propagation phase of the oxidative chain reaction through the donation of a phenolic hydroxyl group of the chromanol ring to free radicals in order to stabilize them [76]. Therefore, the main function of these compounds is to act as a lipid-soluble antioxidant protecting photosynthetic membranes from oxidative stress.

Edible flowers contain tocols, some of them in significant amounts (Table 10). However, these concentrations are affected by the method of extraction. Moreover, in some cases, the tocol content is higher in petals than stems or petioles [70]. Flowers with the highest content of tocols are Calendula officinalis L. (60.9 mg/100 g DW), Viola × wittrockiana (yellow) (24.9 mg/100 g DW), Moringa oleifera Lam. (21.0 mg/100 g DW) and Urtica leptophylla (11.1 mg/100 g DW) [70,72,77,78]. It is mainly tocopherols that are detected, but in some cases, a small quantity of tocotrienols is also present in dried flowers such as Urtica leptophylla (1.1 mg/100 g DW) and Borago officinalis L. (0.5 mg/100 g DW) [70,79]. Usually, α-tocopherol is the dominant compound, ranging from 52 to 93 % of total tocopherol content, followed by γ-tocopherol. In the cases of Amaranthus caudatus L. and Juglans regia L., where low concentrations of tocopherols were detected, β-tocopherol and δ-tocopherol were the dominant compounds, respectively [80,81].

Table 10.

Total tocopherol content of several edible flowers from recent studies.

2.4. Terpenes

The essential oil of edible flowers contains several volatile and aromatic compounds, which also belong to secondary metabolites of plants. They have been used for centuries in cosmetics and medicine, and due to their bioactive components are well-known for their antimicrobial, antioxidant and antipest activities [87]. The main components of flowers’ essential oils belong to the group of terpenes; however, the final composition of each essential oil depends on species (Table 11). In general, the main compounds detected in edible flowers’ essential oil are linalool, α-pinene, 1,8-cineole, eugenol, camphor and camphene.

Table 11.

Major terpenes detected in some edible flowers’ essential oils.

3. Antioxidant Activity of Edible Flowers

Chemical reactions that involve electron transfer between electron-rich molecules to an oxidizing agent, which undergoes reduction, is called oxidation [102]. The oxidizing agents, or simply oxidants, are usually forms of free radicals that have unpaired electrons such as hydroxyl, alkoxyl and reactive oxygen species [3]. These oxidants are very reactive and attack other molecules. The mechanism by which these oxidants (free radicals) usually work involves three main steps: (a) initiation (the number of free radicals increases); (b) propagation (the total number of radicals remains constant and the reaction spreads); and (c) termination (the number of free radicals decreases) [102]. Antioxidants are compounds that prevent the oxidation of systems, and edible flowers contain numerous such compounds. There are two main classes of antioxidants: those that actively inhibit oxidation reactions (primary antioxidants) and those that inhibit oxidation indirectly by mechanisms such as oxygen scavenging, binding pro-oxidants, etc. [103]. Phenolic compounds present in edible flowers may act both as primary antioxidants and secondary antioxidants. Two mechanisms are available for the action of primary antioxidants: the hydrogen-atom transfer (an antioxidant compound quenches free-radical species by donating hydrogen atoms) and the single-electron transfer (an antioxidant transfers a single electron to aid in the reduction of potential target compounds) [102]. Finally, phenolic compounds have the ability to bind with potentially pro-oxidative metal ions operating as secondary antioxidants [104].

Antioxidant activity has been correlated with the maintenance of good health in humans, and therefore is very important to develop analytical protocols to evaluate it to several food products, including edible plants. The first important step to evaluate the antioxidant activity, in plant-based materials, is the extraction of the antioxidant compounds. There are several extraction methods available and each one has its benefits and negatives, and therefore its selection is very crucial for the final estimation of antioxidant activity [105]. Furthermore, for the quantification of antioxidant activity of edible flowers’ extracts, there are several methods available that may be categorized based on the chemistry of the reactions involved. The methods that pertain to the mechanisms of hydrogen-atom transfer include oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay, while those that pertain to the mechanisms of single-electron transfer include Ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay and Cupric-reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) assay. However, there are also methods that pertain to both mechanisms, such as Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay, 2,2-azinobis (3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay or DPPH• (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical cation) assay [102]. In the case of edible flowers, all of these methods have been applied for the estimation of antioxidant activity (Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14).

Table 12.

Antioxidant activity (FRAP and ABTS in DW) of several edible flowers.

Table 13.

Antioxidant activity (FRAP and ABTS in FW) of several edible flowers.

Table 14.

Antioxidant activity (DPPH, μmol TE/g in DW) of several edible flowers.

There are numerous studies in food products that have found a correlation between the TPC and antioxidant activity; however, there are also some studies available that were not able to confirm such correlation. As already highlighted, the mechanisms of antioxidant activity are very complicated and they are affected by a wide range of variables [102]. In addition, since different assays for evaluation of antioxidant activity are available and based on different mechanisms, it is common to detect a correlation between, for example, TPC and DPPH assay, and not for FRAP assay. In the studies where a correlation was observed, this was attributed to the antioxidant capacity of phenolic compounds; while in the studies where the correlation was absent, this was attributed to other compounds, not quantified by TPC analysis, which had antioxidant activity. In a study with 65 edible flowers from China, the correlations between TPC and antioxidant capacities were 0.6344 for DPPH, 0.7587 for ABTS and 0.8588 for FRAP. The correlations between TFC and antioxidant capacities were 0.3265, 0.2435 and 0.2205, respectively [20]. In a similar study with 51 edible flowers, positive linear correlations between total antioxidant capacities and TPC (R2 = 0.911 and 0.954 for FRAP and TEAC values, respectively) were reported. Similar results were reported for water-soluble and fat-soluble fractions [13]. Lower correlations were reported in a study with 23 edible flowers [18]. More specifically, in the case of TPC, the correlations were 0.9589 for ABTS, 0.6333 for DPPH and 0.5991 for FRAP; and in the case of TFC they were 0.2598, 0.0794 and 0.6188, respectively. All these studies confirm that there is not a specific pattern for the correlation of TPC and TFC with the antioxidant capacity and especially by using different antioxidant assays. In general, there is a positive correlation between TPC and antioxidant activity, something that it is not the case for TFC.

4. Toxic and Antinutritional Compounds in Edible Flowers

Although edible flowers have been used throughout centuries for culinary purposes, there is still a need for research studies to evaluate the presence of antinutritional compounds or even compounds with potential toxic properties. Such compounds, which have been reported in foods, include saponins, tannins, phytic acid, protease and amylase inhibitors, antivitamin factors, alkaloids, etc. [106]. Compared to other food products, fewer studies are available for potential antinutritional and toxic compounds in edible flowers. In the case of antinutritional compounds, studies revealed that flowers of Yucca filifera contain undesirable saponins with hemolytic activity [107], flowers of Erythrina americana and Erythrina caribaea contain trypsin inhibitor enzymes and those of Agave salmiana show hemagglutinating activity [61]. However, the traditional common practices applied in culinary uses of edible flowers, such as cooking/boiling and their main use as garnishment, usually reduce their content or even eliminate them and minimize the risk of high intakes, respectively [8]. A characteristic example is the flowers of the Erythrina species that contain a high content of alkaloids, but before intake traditionally people cook/boil them and remove the water in which the flowers are cooked, thus reducing the alkaloid concentration [108].

Another important factor that affects the potential toxicity of edible flowers is their source and origin. More specifically, their cultivation should be very careful in order to avoid contamination by the excessive use of agrochemicals or potential polluted soil, etc. Furthermore, there are several plants that are similar in different countries using different common names, or on the other hand, the use of the same common name for plants from several species. All these suggest that it is very important to perform a complete chemical characterization of every new flower before proposing it for edibility [8]. As already mentioned, there are few studies available, compared to the numerous edible flowers, regarding their potential toxicity. The majority of them use Ames mutagenicity assay in combination with specific analyses in animal models. Most of them concluded that there is no evidence for the toxicity of edible flowers and their extracts when used in an appropriate dosage. Some recent studies evaluated the toxic potential of extracts from Nasturtium officinale [109], marigold flower [110], Bombax ceiba [111], Hibiscus rosa-sinensis [112] and Butea monosperma [113], revealing their safety.

However, in a study with extracts of Hibiscus sabdariffa flowers, although they presented biological activities, they also had toxic effects when consumed for long periods and may increase side effects of certain drugs when coadministered with them [114]. Extracts from Hibiscus sabdariffa L. also proved toxic in an animal model study [115]. All the above revealed that there is a need for more studies regarding the safety of each possible edible plant. Furthermore, some aspects regarding the correlation of edible flowers and potential food allergies should be clarified [116].

5. Conclusions

In the present review article, more than 200 edible flowers are presented alongside with their TPC, TFC and antioxidant activity. Moreover, the most important classes of phytochemicals compounds are reported. Edible flowers may play a very important role to fulfill the growing demand of consumers for natural functional foods. Indeed, edible flowers may find applications in the food industry (food ingredients, beverages, food coloring, floral hydrolates, syrups and jams) or in the biomedical industry as raw material for the extraction of valuable compounds with nutraceutical potentials and health benefits. However, edible flowers are very popular on a small scale. In order to industrialize and increase their production, there is a need to deal with their low lifetimes, their availability in a specific time of year and the need for the application of appropriate drying methods. Edible flowers, over centuries, have been proven as carriers of significant amounts of phytochemicals, belonging to the groups of phenolic acids, flavonoids, carotenoids, tocols and others, which can be incorporated in traditional foods to increase their functionality. Although there are numerous studies regarding the phenolic content and the antioxidant activity of edible flowers, their high numbers all over the world demand for more studies. The present study may be very useful in order to select specific edible flowers with increased phytochemical content and functionality, since not all of them contain significant amounts, to further evaluate their incorporation in food products and also their stability during processing and storage. Furthermore, the present review also revealed the low number of research studies regarding the safety of such edible flowers and extracts, and in particular their potential toxicity. The antinutritional compounds contained in edible flowers are also an issue and more work is needed. Therefore, it is proposed to carry out more in-depth research studies for each edible flower, covering all the above mentioned issues, in order to appropriately and safely use them as ingredients in functional foods.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, R.H. Potential synergy of phytochemicals in cancer prevention: Mechanism of action. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3479S–3485S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Wightman, E.L. Herbal extracts and phytochemicals: Plant secondary metabolites and the enhancement of human brain function. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabawati, N.B.; Oktavirina, V.; Palma, M.; Setyaningsih, W. Edible flowers: Antioxidant compounds and their functional properties. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Bhargava, B. Phytochemicals from edible flowers: Opening a new arena for healthy lifestyle. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 78, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janarny, G.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P.; Ranaweera, K.K.D.S. Nutraceutical potential of dietary phytochemicals in edible flowers—A review. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrajda-Brdak, M.; Dąbrowski, G.; Konopka, I. Edible flowers, a source of valuable phytonutrients and their pro-healthy effects–A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 103, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Li, M.; Yin, R. Phytochemical content, health benefits, and toxicology of common edible flowers: A review (2000–2015). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56 (Suppl. S1), S130–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, E.D.O., Jr.; Di Gioia, F.; Rouphael, Y.; Ferreira, I.C.; Caleja, C.; Barros, L.; Petropoulos, S.A. The compositional aspects of edible flowers as an emerging horticultural product. Molecules 2021, 26, 6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba, F.J.; Esteve, M.J.; Frígola, A. Bioactive components from leaf vegetable products. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2014, 41, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murkovic, M. Phenolic Compounds: Occurrence, Classes, and Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarpa, A.; González, M.C. Approach to the content of total extractable phenolic compounds from different food samples by comparison of chromatographic and spectrophotometric methods. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 427, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.N.; Li, S.; Li, H.B.; Xu, D.P.; Xu, X.R.; Chen, F. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of 51 edible and wild flowers. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 6, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo-Espinoza, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Tlahque, J.; Santiago-Saenz, Y.O.; Aguirre-Mancilla, C.L.; Reyes-Fuentes, M.; López-Palestina, C.U. Nutritional composition, bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of wild edible flowers consumed in semiarid regions of Mexico. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, A.; Grzeszczuk, M. Nutritional and biological value of five edible flower species. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2019, 47, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, R.; Kałwik, J.; Juszczak, L. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of the selected edible flowers grown in Poland. Acta Univ. Cinbinesis Ser. E Food Technol. 2021, 25, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demasi, S.; Caser, M.; Donno, D.; Enri, S.R.; Lonati, M.; Scariot, V. Exploring wild edible flowers as a source of bioactive compounds: New perspectives in horticulture. Folia Hortic. 2021, 33, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.L.; Chen, S.G.; Xie, Y.Q.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Luo, C.X.; Gao, Y.Q. Total phenolic, flavonoid and antioxidant activity of 23 edible flowers subjected to in vitro digestion. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsi, E.; Tsiaka, T.; Ioannou, A.G.; Mantanika, V.; Strati, I.F.; Panderi, I.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Sinanoglou, V.J. In vitro and in silico studies to assess edible flowers’ antioxidant activities. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yu, X.; Maninder, M.; Xu, B. Total phenolics and antioxidants profiles of commonly consumed edible flowers in China. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 1524–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.; Antunes, M.; Fernandes, W.; Campos, M.J.; Azevedo, Z.M.; Freitas, V.; Rocha, J.M.; Tecelão, C. Physicochemical and nutritional profile of leaves, flowers, and fruits of the edible halophyte chorão-da-praia (Carpobrotus edulis) on Portuguese west shores. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Deng, M.; Lv, Z.; Peng, Y. Evaluation of antioxidant activities of extracts from 19 Chinese edible flowers. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, L.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Mao, S.; Shen, C. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacities of 10 common edible flowers from China. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, C517–C525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.S.M.; Alves, R.E.; de Brito, E.S.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Saura-Calixto, F.; Mancini-Filho, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities of 18 non-traditional tropical fruits from Brazil. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Luo, Q.; Sun, M.; Corke, H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2157–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucekova, Z.; Mlcek, J.; Humpolicek, P.; Rop, O. Edible flowers—Antioxidant activity and impact on cell viability. Open Life Sci. 2013, 8, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascual-Teresa, S.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T. Anthocyanins: From plant to health. Phytochem. Rev. 2008, 7, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashina, T. Contribution to flower colors of flavonoids including anthocyanins: A review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Bortolotti, E.; Maggini, R. Antioxidant power, anthocyanin content and organoleptic performance of edible flowers. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 199, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Chong, S.; Yan, S.; Yu, R.; Chen, R.; Si, J.; Zhang, X. Identification and quantitative analysis of anthocyanins composition and their stability from different strains of Hibiscus syriacus L. flowers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 177, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janarny, G.; Ranaweera, K.K.D.S.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P. Antioxidant activities of hydro-methanolic extracts of Sri Lankan edible flowers. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 35, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chensom, S.; Shimada, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Yoshida, K.; Kondo, T.; Katsuzaki, H.; Hasegawa, S.; Mishima, T. Determination of anthocyanins and antioxidants in ‘Titanbicus’ edible flowers in vitro and in vivo. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Barrio, R.; Periago, M.J.; Luna-Recio, C.; Garcia-Alonso, F.J.; Navarro-González, I. Chemical composition of the edible flowers, pansy (Viola wittrockiana) and snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) as new sources of bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 2018, 252, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Doseff, A.I.; Grotewold, E. Flavones: From biosynthesis to health benefits. Plants 2016, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Meenu, M.; Xu, B. A systematic investigation on free phenolic acids and flavonoids profiles of commonly consumed edible flowers in China. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 172, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, B.; Huang, W.; Amrouche, A.T.; Maurizio, B.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Tundis, R.; Xiao, J.; Zou, L.; Lu, B. Edible flowers as functional raw materials: A review on anti-aging properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Schluesener, H. Health-promoting effects of the citrus flavanone hesperidin. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais, J.S.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Dantas, A.M.; Silva, B.S.; Lima, M.S.; Borges, G.C.; Magnani, M. Antioxidant activity and bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds in white, red, blue, purple, yellow and orange edible flowers through a simulated intestinal barrier. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 109046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Dong, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, A. Flavonoids and caffeoylquinic acids in Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat flowers: A potentially rich source of bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji-Naito, K.; Saeki, H.; Hamano, M. Inhibitory effects of Chrysanthemum species extracts on formation of advanced glycation end products. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisoon, O.; Siriamornpun, S.; Weerapreeyakul, N.; Meeso, N. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of edible flowers from Thailand. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xue, J.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, S.; Xue, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X. Composition of peony petal fatty acids and flavonoids and their effect on Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 155, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.L.; Lu, C.K.; Huang, Y.J.; Chen, H.J. Antioxidative caffeoylquinic acids and flavonoids from Hemerocallis fulva flowers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8789–8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Yang, C.; Beta, T.; Liu, S.; Yang, R. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of the edible tree peony flower and underlying mechanisms of preventive effect on H2O2-induced oxidative damage in Caco-2 cells. Foods 2019, 8, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, E.D.O., Jr.; Pereira, E.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Calhelha, R.C.; Soković, M.; Hassemer, G.; Garcia, C.C.; Caleja, C.; Barros, L. Chemical composition and bioactive characterisation of Impatiens walleriana. Molecules 2021, 26, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, S.; Xue, S.; Yang, D.; Li, L. Effects of drying methods on phenolic components in different parts of Chrysanthemum morifolium flower. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, K.; Hu, W.; Hou, M.; Cao, D.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, A.; Yu, J.; Guo, B. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of total phenolics from Citrus aurantium L. blossoms and evaluation of free radical scavenging, anti-HMG-CoA reductase activities. Molecules 2019, 24, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksathan, R.; Rachkeeree, A.; Puangpradab, R.; Kantadoung, K.; Sommano, S.R. Phytochemical and nutritional compositions and antioxidants properties of wild edible flowers as sources of new tea formulations. NFS J. 2021, 24, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kang, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, Y.H. Effect of high pressure and treatment time on nutraceuticals and antioxidant properties of Lonicera japonica Thunb. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 54, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.C.; Barros, L.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C. Edible flowers: Emerging components in the diet. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarte, N.; Cejudo-Bastante, M.J.; Hurtado, N.; Heredia, F.J. First accurate profiling of antioxidant anthocyanins and flavonols of Tibouchina urvilleana and Tibouchina mollis edible flowers aided by fractionation with Amberlite XAD-7. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 2416–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-García, L.; Romero-Márquez, J.M.; Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Esteban-Muñoz, A.; Giampieri, F.; Sumalla-Cano, S.; Battino, M.; Quiles, J.L.; Llopis, J.; Sánchez-González, C. Unravelling potential biomedical applications of the edible flower Tulbaghia violacea. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Bhandari, P.; Singh, B.; Gupta, A.P.; Kaul, V.K. Reversed phase-HPLC for rapid determination of polyphenols in flowers of rose species. J. Sep. Sci. 2008, 31, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Pugliese, A.; Bonesi, M.; Tenuta, M.C.; Menichini, F.; Xiao, J.; Tundis, R. Edible flowers: A rich source of phytochemicals with antioxidant and hypoglycemic properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.L.; Hua, S.; Ye, J.H.; Zheng, X.Q.; Liang, Y.R. Flavonoids and volatiles in Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat flower from Tongxiang County in China. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 3817–3821. [Google Scholar]

- Liang-Yu, W.; Hong-Zhou, G.; Xun-Lei, W.; Jian-Hui, Y.; Jian-Liang, L.; Yue-Rong, L. Analysis of chemical composition of Chrysanthemum indicum flowers by GC/MS and HPLC. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Fang, J.; Liu, M.; Niu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, H. An on-line high-performance liquid chromatography–diode-array detector–electrospray ionization–ion-trap–time-of-flight–mass spectrometry–total antioxidant capacity detection system applying two antioxidant methods for activity evaluation of the edible flowers from Prunus mume. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1414, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.C.; Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C. Edible flowers as sources of phenolic compounds with bioactive potential. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, D.G.; Barros, L.; Maciel, G.M.; Brugnari, T.; Modkovski, T.A.; Fachi, M.M.; Pontarolo, R.; Pinela, J.; Ferreira, I.C.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Bioactive profile of edible nasturtium and rose flowers during simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriada-Bernal, L.G.; Almaraz-Abarca, N.; Delgado-Alvarado, E.A.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T.; Ávila-Reyes, J.A.; Torres-Morán, M.I.; González-Elizondo, M.D.S.; Herrera-Arrieta, Y. Flavonoid composition and antioxidant capacity of the edible flowers of Agave durangensis (Agavaceae). CyTA-J. Food 2014, 12, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisoon, O.; Konczak, I.; Siriamornpun, S. Potential health enhancing properties of edible flowers from Thailand. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Ortega, H.; Pereda-Miranda, R.; Abdullaev, F.I. HPLC quantification of major active components from 11 different saffron (Crocus sativus L.) sources. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1126–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Souto, E.B.; Cicala, C.; Caiazzo, E.; Izzo, A.A.; Novellino, E.; Santini, A. Polyphenols: A concise overview on the chemistry, occurrence, and human health. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2221–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananingsih, V.K.; Sharma, A.; Zhou, W. Green tea catechins during food processing and storage: A review on stability and detection. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Carotenoids Database. Available online: http://carotenoiddb.jp/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Rodriguez-Concepcion, M.; Avalos, J.; Bonet, M.L.; Boronat, A.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Hornero-Mendez, D.; Limon, M.C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Palou, A.; et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: Metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 70, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as natural functional pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggersdorfer, M.; Wyss, A. Carotenoids in human nutrition and health. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 652, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Arroyo, A.; Toro-González, C.; Sus, N.; Warner, J.; Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M.; Frank, J. Vitamin E and carotenoid profiles in leaves, stems, petioles and flowers of stinging nettle (Urtica leptophylla Kunth) from Costa Rica. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primitivo, M.J.; Neves, M.; Pires, C.L.; Cruz, P.F.; Brito, C.; Rodrigues, A.C.; de Carvalho, C.C.; Mortimer, M.M.; Moreno, M.J.; Brito, R.M.; et al. Edible flowers of Helichrysum italicum: Composition, nutritive value, and bioactivities. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Ramalhosa, E.; Pereira, J.A.; Saraiva, J.A.; Casal, S. Borage, camellia, centaurea and pansies: Nutritional, fatty acids, free sugars, vitamin E, carotenoids and organic acids characterization. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K.; Chojnacka, A.; Górnicka, M. Tocopherols and tocotrienols—Bioactive dietary compounds; what is certain, what is doubt? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzi, A. Tocopherols, tocotrienols and tocomonoenols: Many similar molecules but only one vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahoon, E.B.; Hall, S.E.; Ripp, K.G.; Ganzke, T.S.; Hitz, W.D.; Coughlan, S.J. Metabolic redesign of vitamin E biosynthesis in plants for tocotrienol production and increased antioxidant content. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E.; Rémésy, C. Is the in vitro antioxidant potential of whole-grain cereals and cereal products well reflected in vivo? J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.C.; Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Nutritional and chemical characterization of edible petals and corresponding infusions: Valorization as new food ingredients. Food Chem. 2017, 220, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, Â.; Bancessi, A.; Pinela, J.; Dias, M.I.; Liberal, Â.; Calhelha, R.C.; Ćirić, A.; Soković, M.; Catarino, L.; Ferreira, I.C.; et al. Nutritional and phytochemical profiles and biological activities of Moringa oleifera Lam. edible parts from Guinea-Bissau (West Africa). Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Pereira, J.A.; Saraiva, J.A.; Ramalhosa, E.; Casal, S. Phytochemical characterization of Borago officinalis L. and Centaurea cyanus L. during flower development. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roriz, C.L.; Xavier, V.; Heleno, S.A.; Pinela, J.; Dias, M.I.; Calhelha, R.C.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L. Chemical and bioactive features of Amaranthus caudatus L. flowers and optimized ultrasound-assisted extraction of betalains. Foods 2021, 10, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, A.; Fizeșan, I.; Vlase, L.; Rusu, M.E.; Cherfan, J.; Babota, M.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Tomuta, I.; Popa, D.S. Enhanced recovery of phenolic and tocopherolic compounds from walnut (Juglans regia L.) male flowers based on process optimization of ultrasonic assisted-extraction: Phytochemical profile and biological activities. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberal, Â.; Coelho, C.T.; Fernandes, Â.; Cardoso, R.V.; Dias, M.I.; Pinela, J.; Alves, M.J.; Severino, V.G.; Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L. Chemical features and bioactivities of Lactuca canadensis L., an unconventional food plant from Brazilian Cerrado. Agriculture 2021, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cervantes, J.; Sánchez-Machado, D.I.; Cruz-Flores, P.; Mariscal-Domínguez, M.F.; de la Mora-López, G.S.; Campas-Baypoli, O.N. Antioxidant capacity, proximate composition, and lipid constituents of Aloe vera flowers. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 10, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockowandt, L.; Pinela, J.; Roriz, C.L.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Barros, L.; Bredol, M.; Ferreira, I.C. Chemical features and bioactivities of cornflower (Centaurea cyanus L.) capitula: The blue flowers and the unexplored non-edible part. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskienė, R.; Venskutonis, P.R. Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Narcissus poeticus L. Flowers for the Isolation of Volatile Fragrance Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandim, F.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Fernandes, Â.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L. Chemical composition of Cynara cardunculus L. var. altilis heads: The impact of harvesting time. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B.; Mujumdar, A.S. Edible flower essential oils: A review of chemical compositions, bioactivities, safety and applications in food preservation. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, C.C.; Devi, S.; Dash, S.K.; Mishra, R.K. Antibacterial potential assessment of Jasmine essential oil against E. coli. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 70, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalagatur, N.K.; Mudili, V.; Kamasani, J.R.; Siddaiah, C. Discrete and combined effects of Ylang-Ylang (Cananga odorata) essential oil and gamma irradiation on growth and mycotoxins production by Fusarium graminearum in maize. Food Control 2018, 94, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosimi, S.; Rossi, E.; Cioni, P.L.; Canale, A. Bioactivity and qualitative analysis of some essential oils from Mediterranean plants against stored-product pests: Evaluation of repellency against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky, Cryptolestes ferrugineus (Stephens) and Tenebrio molitor (L.). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2009, 45, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabulal, B.; George, V.; Dan, M.; Pradeep, N.S. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activities of the essential oils from the rhizomes of four Hedychium species from South India. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2007, 19, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerbetçi, T.; Özsoy, N.; Demirci, B.; Can, A.; Kültür, Ş.; Başer, K.C. Chemical composition of the essential oil and antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts from fruits and flowers of Hypericum lydium Boiss. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 36, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannes, W.A.; Mhamdi, B.; Sriti, J.; Jemia, M.B.; Ouchikh, O.; Hamdaoui, G.; Kchouk, M.E.; Marzouk, B. Antioxidant activities of the essential oils and methanol extracts from myrtle (Myrtus communis var. italica L.) leaf, stem and flower. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Castellanos, P.P.; Bishop, C.D.; Pascual-Villalobos, M.J. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of flowerheads of garland chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum coronarium) against agricultural pathogens. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazdar, M.; Sadeghi, H.; Hosseini, S. Evaluation of oil profiles, total phenols and phenolic compounds in Prangos ferulacea leaves and flowers and their effects on antioxidant activities. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, E.; Poiata, A.; Hancianu, M.; Tzakou, O. Chemical composition and in vitro antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of flower heads and leaves of Santolina rosmarinifolia L. from Romania. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 21, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, R.; Medici, A.; Andreotti, E.; Fantin, C.; Muzzoli, M.; Dehesa, M.; Romagnoli, C.; Sacchetti, G. Chemical composition and biological activities of Ishpingo essential oil, a traditional Ecuadorian spice from Ocotea quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. (Lauraceae) flower calices. Food Chem. 2004, 85, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.U.; Ding, Y.C.; Ye, X.Q.; Ding, Y.T. Antibacterial effect of cinnamon oil combined with thyme or clove oil. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 1482–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Gu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cui, H. Characterization of chrysanthemum essential oil triple-layer liposomes and its application against Campylobacter jejuni on chicken. LWT 2019, 107, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, B.; Marques, A.; Ramos, C.; Neng, N.R.; Nogueira, J.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Nunes, M.L. Chemical composition and antibacterial and antioxidant properties of commercial essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N.; Singh, V.K.; Dwivedy, A.K.; Das, S.; Chaudhari, A.K.; Dubey, N.K. Cistus ladanifer L. essential oil as a plant based preservative against molds infesting oil seeds, aflatoxin B1 secretion, oxidative deterioration and methylglyoxal biosynthesis. LWT 2018, 92, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, B.D.; Kerrihard, A.L.; Amarowicz, R.; Pegg, R.B. Phenol-based antioxidants and the in vitro methods used for their assessment. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012, 11, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Janitha, P.K.; Wanasundara, P.D. Phenolic antioxidants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1992, 32, 67–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.; Miller, N.; Paganga, G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants 2017, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Dhewa, T. Plant food anti-nutritional factors and their reduction strategies: An overview. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2020, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, A.; López-García, S.; Basurto-Peña, F. Content of nutrient and antinutrient in edible flowers of wild plants in Mexico. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2007, 62, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mateos, R.; Lucas, B.; Zendejas, M.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Martínez, M.; Sotelo, A. Variation of total nitrogen, non-protein nitrogen content, and types of alkaloids at different stages of development in Erythrina americana seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 2987–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, M.; Miguel, M.D.; Felipe, K.B.; Gribner, C.; Moura, P.F.; Rigoni, A.G.R.; Fernandes, L.C.; Carvalho, J.L.S.; Hartmann, I.; Piltz, M.T.; et al. Acute and sub-acute oral toxicity studies of standardized extract of Nasturtium officinale in Wistar rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 108, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, A.; Hina, S.; Mazhar, S.; Kalim, I.; Ijaz, A.; Zahra, N.; Masood, S.; Asif, M. Stability of lutein content in color extracted from marigold flower and its application in candies. Pak. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 31, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjari, M.M.; Gangoria, R.; Dey, Y.N.; Gaidhani, S.N.; Pandey, N.K.; Jadhav, A.D. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of Bombax ceiba flowers against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Hepatoma Res. 2016, 2, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ghosh, D.; Sagar, N.; Ganapaty, S. Evaluation of antioxidant, toxicological and wound healing properties of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. (Malvaceae) ethanolic leaves extract on different experimental animal models. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2016, 50, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Gupta, S.; Ahmad, S. Toxicology of the aqueous extract from the flowers of Butea monosperma Lam. and it’s metabolomics in yeast cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojulari, O.V.; Lee, S.G.; Nam, J.O. Beneficial effects of natural bioactive compounds from Hibiscus sabdariffa L. on obesity. Molecules 2019, 24, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Arruda, A.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Vieira, M.D.C.; Arena, A.C. Safety assessment of Hibiscus sabdariffa after maternal exposure on male reproductive parameters in rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 39, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucarini, M.; Copetta, A.; Durazzo, A.; Gabrielli, P.; Lombardi-Boccia, G.; Lupotto, E.; Santini, A.; Ruffoni, B. A snapshot on food allergies: A case study on edible flowers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).