Abstract

LiDAR is a technology that uses lasers to measure the position of elements. Measuring the laser travel time and calculating the distance between the LiDAR and the surface requires the calculation of eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the convergence matrix. SVD algorithms have been proposed to solve an eigenvalue problem, which is computationally expensive. As embedded systems are resource-constrained hardware, optimized algorithms are needed. This is the subject of our paper. The first part of this paper presents the methodology and the internal architectures of the MUSIC processor using the Cyclic Jacobi method. The second part presents the results obtained at each step of the FPGA processing, such as the complex covariance matrix, the unitary and inverse transformation, and the value and vector decomposition. We compare them to their equivalents in the literature. Finally, simulations are performed to select the way that guarantees the best performance in terms of speed, accuracy and power consumption.

1. Introduction

The MUSIC algorithm (Multiple Signal Classification) is known as one of the best algorithms for estimating multipath angles. It decomposes the covariance matrix into eigenvalues to obtain eigenvectors of the signal and the noise. Its advantage is good resolution. One of the downsides is that you must use a lot of data. In addition, the signals cannot be changed during treatment, and they must be decorrelated.

It is an algorithm that allows active spatio-temporal separation of multipath. At first, it was developed in the time domain, but later it became improved thanks to the spatial dimension that was added. However, as an active algorithm, it needs periodic sending of a known signal.

The DOA allows base stations to locate users, to allow reuse of the same communication frequencies within the same cell by forming separate beams for each of these users, without interference or interference that could deteriorate the quality of communication. This method is called Spatial Division Multiple Access or Spatial Division Multiple Access. In addition, precise knowledge of the directions and arrival times would be sufficient to properly estimate the propagation channel without having to resort to a preamble as is done in mobile radio communication. Another example of application is the very precise identification of directing a phone call after an emergency so that the rescue team can be dispatched to the appropriate location. This last example is even more practical, because unlike the technologies currently in use such as GPS and the triangulation of base stations, one would be able to clearly identify an apartment in a building block even with several floors [1,2,3].

Several algorithms for determining the direction of arrival of beams relative to the antenna array already exist, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. The general operating principle of these algorithms is to obtain, from the data collected, a spectrum or a pseudo-spectrum indicating, depending on the direction of observation, the importance or not of a source in this direction.

Among these algorithms, there is lane formation which gives an estimate of the power coming from the target direction. On the other hand, the spectrum obtained is much less precise than those with high-resolution algorithms. The maximum likelihood is a high-resolution algorithm based on iterative calculations of conditional probabilities, but effective in the case of coherent interference. Considered the most widely used for DOA applications, the MUSIC algorithm [4] is highly accurate even in the presence of noise. MUSIC exploits the subspaces generated by the eigenvectors resulting from a decomposition upstream of the covariance matrix of the signals received. Its main weakness besides the heavy computing time is the mediocrity of the estimate in the presence of interference from a coherent wave to the signal incident to the network. To correct this imperfection, the technique of spatial smoothing [5] is often combined with MUSIC [6,7]. The list is not exhaustive, there are more algorithms such as Estimation of Signal Parameters via Rotational Invariance Techniques (ESPRIT) [4,5,6,7,8], Capon and even others, based on neural networks ideal for real-time applications [9,10]. The latter, however, give less precise results. All these methods justify their existence through the compromise between precision and the heaviness of the computation time for applications requiring real-time processing. This last limitation, namely the heavy computing time, is less and less limiting due to the development of very high-density integrated circuits, grouped under the acronym of VLSI (Very Large-Scale Integration). These are endowed with incomparable computing power from structures based on parallelism and allowing extremely short operating cycles [11,12,13].

In [14] the authors propose to further decrease the execution time of this parallel method. In particular, each parallel unit of the proposed method uses one coordinate rotation digital computer (CORDIC) period per iteration, while more are required by the traditional counterparts, such that the eigenvalue decomposition of the MUSIC algorithm. In [15] the authors use Cyclic Jacobi method to implement EVD processor, which can achieve hardware simplification. To reduce the latency, this paper proposes using the neural network model to calculate the values of arctangent, sine and cosine function instead of using the traditional CORDIC (Coordinate Rotation Digital Computer) method. The proposed NN-based Cyclic Jacobi EVD processor was operated at 250 MHz in TSMC 90 nm CMOS technology. This paper consists of a simulation phase and a prototyping phase. The simulation will make it possible to develop the MUSIC algorithm and validate its operating principle with the Xilinx Vivado software. Prototyping will consist of migrating this algorithm to a platform based on an FPGA circuit to verify its technical feasibility and evaluate its performance. It is in this prototyping phase that various constraints may arise, related to the precision of the calculations, the speed of execution (real-time operation) and the testability of the system. The implementation of the MUSIC algorithm for real-time processing will exploit several advanced techniques, including frequency sub-band averaging which will artificially reduce the level of inter-correlation between echoes. These techniques will increase execution speed and push memory limits.

One of our contributions in this research concerns the covariance matrix. Exploiting the Hermitian symmetry characteristic of the covariance matrix, the multiplication operations affect only half of the matrix, the other half is deduced by a simple sign change. Another contribution concerns the choice of an EVD decomposition technique with a minimum computational burden while maintaining good precision. The selected candidate is the Jacobi method.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present signal representation and covariance matrix. In Section 3, we handle the hardware architecture design based on Cyclic Jacobi Method. In Section 4 we provide a comparison and a discussion of this work with other research. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

The subspace methods are based on the spectral decomposition of the covariance matrix of the signals coming from the sensors. They separate the characteristic space of the covariance matrix of the global signal into eigen signal subspace and noise subspace using an eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix. The MUSIC method is an example of this type of method which was first proposed by Schmidt R.O. in 1986 [4] to estimate the directions of arrival of signals. This method can detect several near sources and has better performance than the conventional beam forming method provided that these sources are uncorrelated or weakly correlated. If the sources are strongly correlated, this method requires modification by the uncorrelated algorithms.

The LiDAR system receives signals emitted by radiating sources on which an additive noise is superimposed. It is assumed that the signals emitted by these sources are stationary, centered and not correlated with the additive noise. The P sources are placed in a far field, therefore assumed to be the point.

Let be the signal vector observed by the LiDAR system:

We define the directional vector or the model which corresponds to a perfect transfer signal of the sources by a Gaussian function. The model signal corresponds to a perfect signal where the echo is diluted with samples. The vector is in the form:

- •

- : Vector of the amplitudes of the signals emitted by the P sources at the instant t;

- •

- : Matrix of directional vectors of dimension ;

- •

- : Additive noise vector on the N sensors.

The P signals from the sources are assumed to be independent, the covariance matrix of these sources is then:

With the power of the ith source (obstacle) that we want to locate.

It was also assumed that the signals emitted by these sources are stationary, centered and not correlated with the noise (white noise), we can therefore deduce the covariance matrix:

where

- •

- : covariance matrix of the source signals of dimension ;

- •

- : ambient noise covariance matrix of dimension , where is the noise variance and I is the identity matrix;

In practice, we estimate the covariance matrix from a finite number of temporal samples in the form:

where is the signal vector sampled at time k and T is the number of samples.

The spectral decomposition of the covariance matrix R into eigen elements to separate the signal subspace from the noise subspace can be expressed in the following form:

where ∧ is the diagonal matrix of the eigenvalues of the matrix R and U is the matrix formed of the eigenvectors corresponding to the eigenvalues of the matrix R (classified in decreasing order). Therefore, we have:

And with , where and represent, respectively, the matrices of the eigenvalues associated with the signal subspace and with the noise subspace. The eigenvectors forming corresponding to the smallest eigenvalues are orthogonal to the column vectors of the transfer matrix A:

Therefore, we have:

This orthogonality is due to the fact that the vectors of the signal subspace generate the same subspace as the column vectors of the source transfer matrix and as is orthogonal to we therefore have the columns of which are also orthogonal to those of . To estimate the directions of arrival of the sources, the model of the source vector must be known.

The orthogonality of the directional vectors with the eigenvectors of the noise subspace is then characterized by a projection of the signal subspace on the noise subspace (this is why the MUSIC method is also called projection subspace algorithm) and we seek the values for which the noise subspace is orthogonal to the signal subspace, which corresponds to the directions of arrival of the waves. The angular spectral function obtained by the MUSIC method makes it possible to determine the values of for which this function is maximum, and it is defined in the following form:

where is the ith vector of the matrix resulting from the noise subspace.

It should be noted that is not a real spectrum (it is a measure of the distance between two subspaces), it gives us peaks corresponding to the exact directions of arrival of the waves but does not tell us about the power of the sources.

The classical MUSIC method requires that the source signals be completely uncorrelated so that the estimation of their directions of arrival is correct. However, the rank of the covariance matrix R is always equal to the number of completely uncorrelated signals, so as soon as there is a strong correlation between two signals, the rank of this correlation matrix is reduced by one unit, which implies an underestimation of the number of directions of arrival of the waves and the MUSIC algorithm is no longer directly applicable in this case.

As described in the previous part, the classical MUSIC method is based on the spectral decomposition of the covariance matrix R for the estimation of the directions of arrival of the waves. The covariance matrix R is decomposed into P larger eigenvalues as well as smaller values.

The eigenvectors corresponding to the P largest eigenvalues construct a signal subspace that is identical to the A source transfer matrix and the eigenvectors corresponding to the smallest eigenvalues construct a noise subspace.

Through the property of orthogonality between the directional vectors of the signals with the vectors constituting the noise subspace, the null points, i.e., the arrival directions, are thus determined [16,17,18].

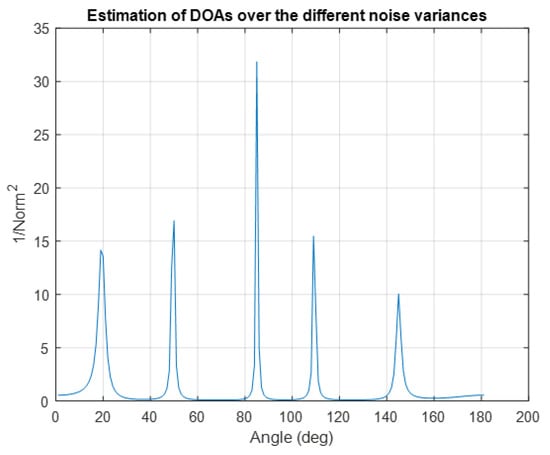

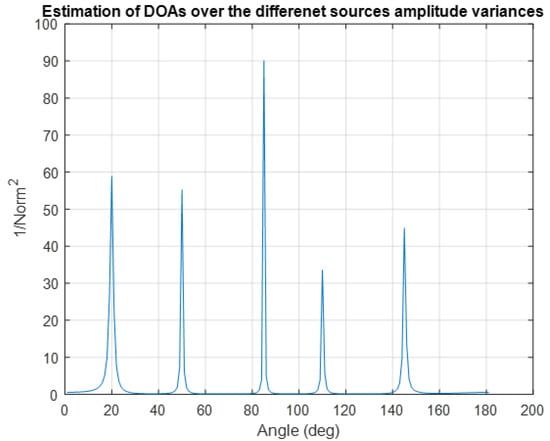

Considering incident sources with DOAs randomly selected from [0°, 180°] and adopting uniform linear array with element spacing , The number of snapshots, and the SNR is 0 dB, we present the spectra and DOA estimation results, Estimate DOA on different noise variances in Figure 1 and Estimate DOA on different source amplitude variances, respectively, in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

DOA Estimation for SNR = 0 db, Snapshot Number = 100, P = 5 and DOA = [20°; 50°; 85°; 110°; 145°] (different noise variances).

Figure 2.

DOA Estimation for SNR = 0 db, Snapshot Number = 100, P = 5 and DOA = [20°; 50°; 85°; 110°; 145°] (different source amplitude variances).

3. Hardware Architecture

We illustrate in Table 1,the performance of some existing DOA estimation algorithms via numerical simulations (MUSIC [4], 1-svd [19], OGSBL [20] and SPA [21]).

Table 1.

The computational complexity of DOA estimation algorithms.

The MUSIC processor hardware architecture is made up of three parts:

- Covariance matrix.

- EVD processor.

- Minimum detector.

3.1. Covariance Matrix

- Signals of 512 or 1024 samples.

- Amplitude only, no phase information.

- Several sequences of the same scene available, from 1 to 48.

- The matrix containing the input sequences .

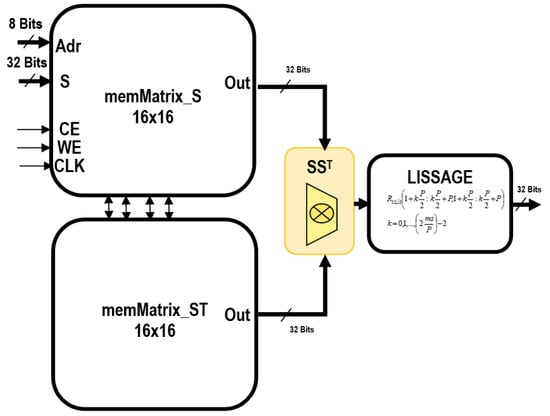

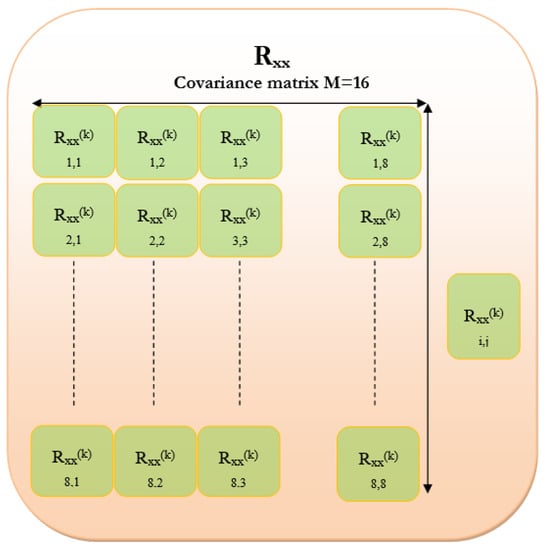

The matrix is represented by Equation (14), it is a square matrix of dimensions and each of the two dimensions is equal to the number of samples of the signals. Since the signals are strongly correlated, the covariance matrix undergoes spatial smoothing when it is created. Spatial smoothing will allow the proper decomposition of the covariance matrix even if the signals are coherent and will improve the detection of echoes in noisy signals. The covariance matrix is previously declared and filled with 0. It is filled by adding square covariance sub-matrices, where each of the dimensions is of magnitude P, the spatial smoothing parameter specified as an input parameter. Figure 3 represents the hardware architecture of covariance matrix.

Figure 3.

Hardware architecture of covariance matrix.

Its value is usually 16, if not somewhere between 8 and 32. Eventually, the smoothed covariance matrix is created this way:

where .

We used CORE Generator (from IPs) instead of using programs (.vhd). CORE Generator is a tool with graphical interface allowing the creation of modules of higher complexity including memories, mathematical functions, communications interfaces, etc. allowing us to optimize the modules created to exploit the unique characteristics of each Xilinx FPGA.

We used the CORE Generator tool to generate a RAM with 256 elements with a size of 32 bits to store the S signal. Note from Table 2, the number of slices 325 is almost and the No. of IOBs is 74 that is almost of Virtex XCV1000e-8bg560 FPGA.

Table 2.

Hardware resource utilization of the design (RAM with CORE Generator).

We also used a multiplier with the CORE Generator and you find the synthesis results in Table 3. We can also use the multiplication with the CORE Generator:

Table 3.

Hardware resource utilization of the design (Multiplier with CORE Generator).

After verification testing, we changed the design a bit using the Floating Point block and a memory block to store the data temporarily using CORE Generator.

In this architecture, we used two blocks Floating Point and memMatrix_Rss bits.

We used the CORE Generator tool to generate a RAM with bits to store the result of the multiplication with the Floating block.

3.2. EVD Processor

3.2.1. Cyclic Jacobi Method

In this part, we want to present the Cyclic Jacobi method which is often used for the calculation of eigenvalues and vectors. With this method, we try to bring the matrix to a diagonal shape to find everything. Its eigenvalues and eigenvectors, and this by a sequence of orthogonal transformations [22,23,24].

This section describes the basic principle of the Cyclic Jacobi method [25,26]. It can be implemented with a simple iterative rotation plan process. This method makes it possible to solve problems of symmetric eigenvalues by applying a sequence of orthonormal rotations on the left and right sides of the matrix R [27].

With J is the rotation multiple of cyclically by , which is called a Jacobi sweep, the exponent and N denote the transpose operation and array length.

where is a rotation of an orthonormal plane on an angle in the plane with , and . The symmetric matrix R is transformed into by a rotation is defined by Equation (Section 3.2.1) [28,29].

On the other hand, the execution of a similarity of transformation

The decomposition of the covariance matrix is obtained by factorizing the matrix with three matrices with Q is an orthogonal matrix and ∧ is a diagonal matrix which contains the values of the matrix . The Jacobi method makes it possible to iteratively calculate the eigenvalues as follows [30,31]:

With

With is orthogonal plane of rotation with the angle in the plane and ( and )

After running all the pairs . The matrix converges to the matrix ∧ which contains all the eigenvalues .

We did some research on Jacobi’s method and on the applications of this method in FPGA circuit, we found some improvements of this method especially in [32]. The idea here is to divide the covariance matrix into element dimension sub-matrix the sub-matrices are shown in Equation (23) [32].

The process of diagonalization of the matrix is represented by Equation (20) with the following conditions .

where

The angle of rotation is defined by:

The eigenvectors of the covariance matrix are represented by , these vectors are calculated by an iterative process with the Jacobi method with [2,32].

;

With is a element sub-matrix and .

3.2.2. Calculation of Eigenvalues

The idea here is to divide the covariance matrix Equation (23) into sub-matrices of element dimensions the sub-matrix is presented by Equation (24).

With

The process of iterative calculation of the covariance matrix by the Jacobi method is presented by Equation (26).

With and

The rotation matrix is obtained according to the following formula:

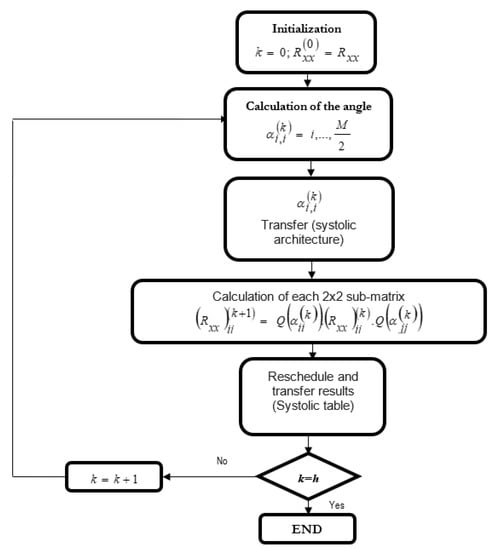

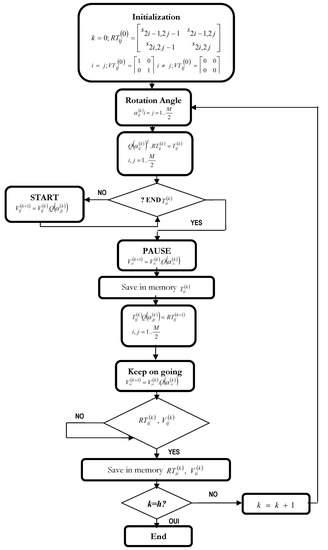

In Figure 4 one can describe the various stages of computation of the eigenvalues of the sub-matrices.

Figure 4.

Flowchart for the calculation of eigenvalues by sub-matrices by Jacobi’s method.

The angle of rotation is defined by Equation (37). In our case since the symmetric covariance matrix.

The preceding flowchart explains the various stages of calculation of the eigenvalues.

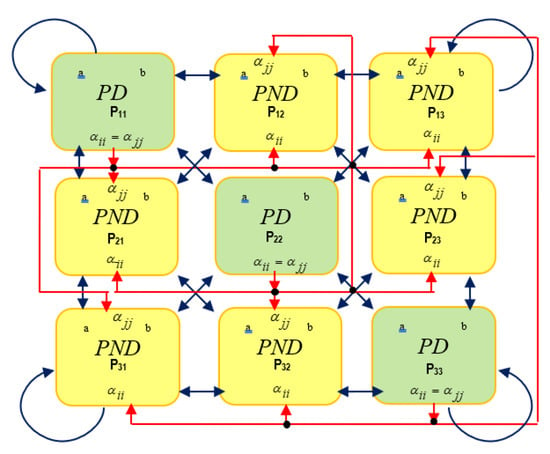

Figure 5 represents the hardware architecture of the covariance matrix with . Figure 6 represents the systolic operating architecture for the decomposition of eigenvalues and vectors.

Figure 5.

Covariance matrix M = 16.

Figure 6.

Systolic operating architecture for the decomposition of eigenvalues and vectors.

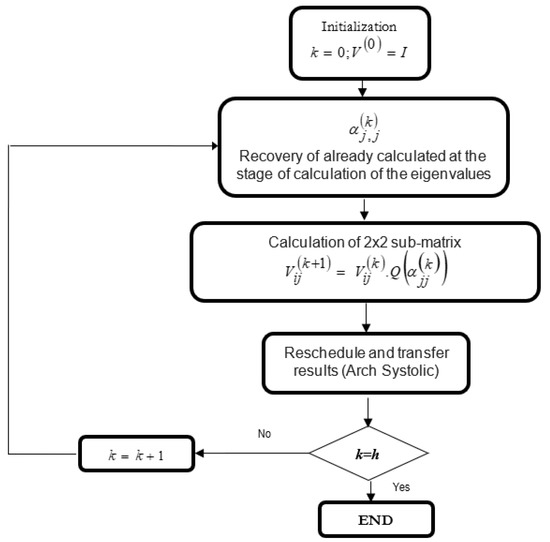

3.2.3. Computation of the Eigenvectors

The eigenvectors of the covariance matrix are represented by the vector , these vectors are calculated by an iterative process with the Jacobi method with .

The angle of rotation necessary for eigenvector sub-matrices is generated at the eigenvalue stage, in particular diagonal sub-matrix types [2].

3.2.4. Architecture for the Calculation of Eigenvalues and Eigenvalues

When the implementation of the flowchart shown in Figure 7, we can see that there are basically four operations, regardless of the platform hardware chosen to implement the algorithm.

Figure 7.

Flowchart for calculating eigenvectors using sub-matrices of elements based on Jacobi’s method.

- Calculation of the angle of rotation.

- Transfer the angles from the diagonal matrix to the non-diagonal matrix.

- Multiplication or double rotation operation in each sub-matrix.

- Reordered and transferred results from sub-matrix.

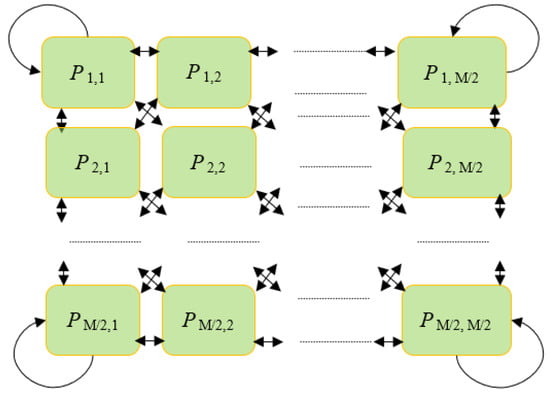

3.2.5. Systolic Architectural

- contains four sub-matrix elements

- From each diagonal processor it is possible to calculate the rotation angles

- Angles are sent to NDPs in the same row and column as DP (used to calculate angles)

- CORDIC is used to calculate the angles of rotation.

- Each NDP processor needs two angles and (in the case of DP processor it is the same angles )

- NDP angles are sent from DPs that are associated with the same line

- Each processor at the angles necessary to perform the double multiplication, to do this we will use the CORDIC architecture.

- With a single rotation the off-diagonal elements of DP are cancelled on the other hand the off-diagonal elements of NDP are modified.

- Even in double rotation the diagonal elements approach zero, but they are not cancelled.

DP: Diagonal Processor; NDP: Non-Diagonal Processor

Figure 8 shows the architecture of elements to obtain eigenvalues.

Figure 8.

Architecture of elements to obtain eigenvalues.

3.2.6. Application of CORDIC for the Calculation of Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors by the Jacobi Method

Starting from the fact that:

The angle of rotation in each DP can be calculated as follows:

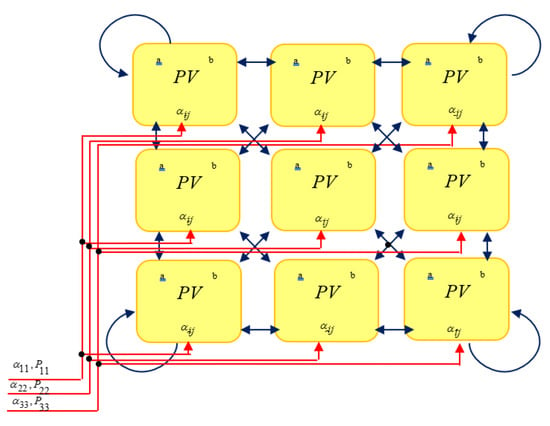

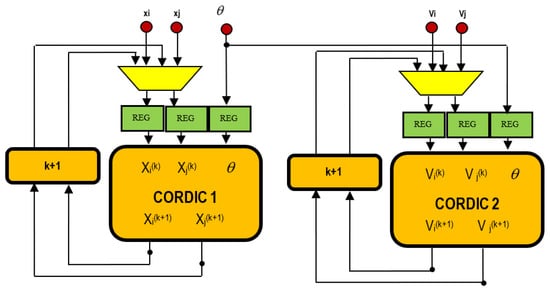

Figure 9 shows the systolic architecture to obtain eigenvalues.

Figure 9.

Systolic architecture to obtain eigenvalues.

Figure 10 shows the systolic architecture to obtain eigenvectors.

Figure 10.

Systolic architecture to obtain eigenvectors.

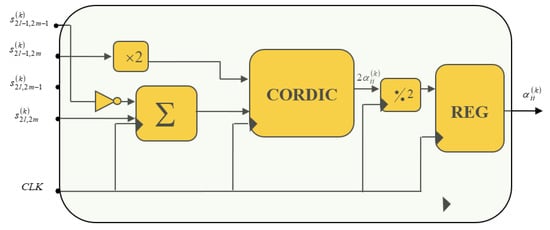

Figure 11 shows the material architecture of the rotation angle calculation block using the Jacobi method.

Figure 11.

Material architecture.

The double rotation is carried out for all the processors for the computation of the eigenvalues using the CORDIC. Each processor is defined by these angles , and these elements (a, b, c and d) in our case the four elements of the sub-matrix [2].

where

Analysis Equation (33) shows that this expression is equivalent to the coordinate vector rotation . The angle and a rotation vector also an angle .

We ask ourselves now:

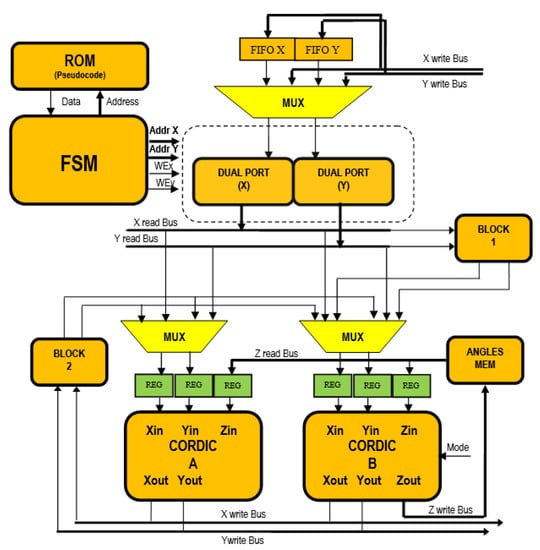

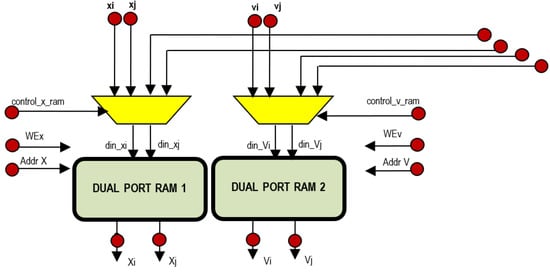

Figure 12 presents the first part of our design where there are two memory blocks DUAL port Ram 1 and 2, two multiplexers and the inputs/outputs signals.

Figure 12.

Dual Port Ram 1 and 2.

The idea here is to optimize the hardware architecture and the speed of calculation of the values and eigenvectors. The principle of operation of the new architecture is based on the systolic architecture. After initialization and loading of data in each processor, the operating sequence of this architecture according to the Jacobi method is described as follows [33,34]:

- Calculate the angles of rotation in the DPs.

- Double rotation for the computation of the eigenvalues and simple rotation of eigenvectors.

- The results of internal reordering in each processor and transmitted to adjacent processors

Due to the symmetry of the matrix, the classical Brent systolic structure can be reduced to a triangular systolic structure, thus eliminating NDPs corresponding to the lower triangular matrix. With this simplification, if the size of the input matrix is , the number of NDPs are reduced Equation (41).

- FSM: The FSM is responsible for decoding the information in the ROM memory and changing according to the necessary information of the control signals and the addresses of the DP memory.

- FIFO memories: Used to temporarily store the eigenvectors in each iteration when the data bus is occupied by a DP phase.

- CORDIC modules: We will use two CORDIC-A and CORDIC-B modules with circular coordinates, whose internal structure is identical. The difference between the two is that the module only works in a rotation mode, while B in a rotation and vectorization mode.

- Block 1: This block is composed of registers, multiplexers and addition/subtraction. Its function is to successfully generate, from data from other blocks, the inputs of CORDIC B.

- Block 2: Implements the information and the exchange of values between the first and the second eigenvalues of phase rotation, according to expression Equation (31). This block prevents the passage through the DP in the transition between the first and the second rotation, which does not limit the bandwidth of the DP. Memory angles (Angles): Present rotation angles generated in the CORDIC B. Depending on the calculation that the FSM is working the system processes one angle or another is archived.

- Dual-Port (DP): Used to store the matrix and the identity matrix. In addition, this memory is used to store temporary data at each iteration.

Figure 13 shows the second part of our design; where we find the two CORDICs 1 and 2, temporary registers, multiplexers and the input/output signals. The input vector, (, ), is expressed as a pair of numbers in signed format. The input rotation angle, radians Theta, is expressed as a signed number. The output vector (, ), is expressed as a pair of signed numbers of format . In our case, the input/output width is set to 32 bits and the output vector (, ) is scaled to compensate for the CORDIC scaling factor.

Figure 13.

CORDIC_IP.

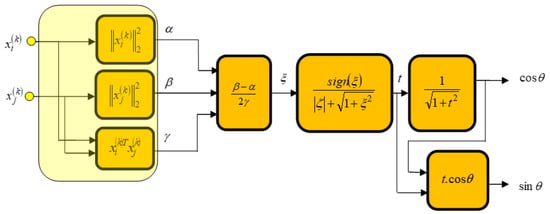

Figure 14 presents the third part of our design, this module allows the calculation of the angle , where: , and

Figure 14.

Part 3 (IP Angle Calculation).

Figure 15 shows the flowchart for calculating values and eigenvectors based on the systolic architecture, the technique used here shows us how we can optimize the hardware architecture and how we can save computing time.

Figure 15.

Flowchart for the calculation of vectors and eigenvalues.

This technique is effective, in practical applications, in the embedded field and especially in LiDAR applications which requires a lot of hardware calculation. Table 4 shows the optimal results of the implementation of our method on FPGA.

Table 4.

Hardware resource utilization of the design (Dual Port Ram 1and 2).

Table 5 presents the inputs/outputs of the hardware implementation for part 2 which is intended for the calculation of the angle.

Table 5.

Inputs/Outputs-Cordic (Project File: Part 2).

Table 6 presents the hardware resource use of Part 2: CORDIC_IP. The used values of the look-up-table (LUT), Flip-Flop (FF), and Slices were 8404, 8536 and 4640, respectively.

Table 6.

Hardware resource utilization of the design (Part 2: CORDIC_IP).

4. Discussion

In [35] the authors present the implementation of finding direction of arrival of the signal to an array system using MUSIC algorithm. The solution includes finding general eigenvalues and used Jacobi algorithm for the calculation of eigenvalues and eigenvectors, which uses rotation mode to realize Eigenvalue decomposition to reduce computations and finally achieve real-time array direction finding [36,37]. In [38] the authors present parallel Jacobi EVD Methods on integrated circuits. Table A1 in the appendix shows complexity times of different well-known algorithms.

Our work focuses, rather, on the synthesis and architectural implementation of an embedded processor on which the MUSIC algorithm dedicated to LiDAR applications are implemented. The MUSIC algorithm is a second-order estimator which is based on the subspaces obtained by the eigenvalue and eigenvector decomposition of the covariance matrix of the signals from the sensors. To estimate echo delays, this new algorithm, simulated and tested with real data, demonstrated high estimation accuracy despite low signal-to-noise ratios and significant overlapping of echoes. The algorithm makes it possible, among other things, to distinguish very close echoes. It was necessary to perform an eigenvalue decomposition to project the received signals into a subspace orthogonal to the source signal subspace. The realized processing processor provides a lot of softness and flexibility, on the one hand, while exploiting the parallel processing resources available in the FPGA to the maximum, to allow the real-time execution of the MUSIC algorithm. This has several advantages, among them we enumerate:

- shorter development time;

- lower cost for small series (less than 10,000 units);

- possibility of porting from FPGA design to an ASIC version faster and cheaper;

- modern FPGAs are very high performance and contain enough memory to accommodate a fast processor core to run software.

The comparison with related work clearly demonstrates that our design can strike a satisfactory balance between resource consumption and computing time cost and is suitable for deployment on embedded devices with a limited resource budget. Table 7 summarizing the allocation of FPGA resources to the implemented proposed EVD processor.

Table 7.

Performance comparison of our design and selected previous pieces of research.

5. Conclusions

The hardware implementation of MUSIC was a major challenge of this paper. Implementing it in its intrinsic form on an FPGA would have required a lot of resources and computation time. Thus, our first intervention addressed the covariance matrix. Taking advantage of the Hermitian symmetry characteristic of the covariance matrix, the multiplication operations performed in parallel concerned just half of the matrix, and the other half was reconstituted by a simple sign change. The other intervention concerned the choice of an EVD decomposition technique with a low computational load and good accuracy. The best candidate was the Jacobi method. This iterative method led to the development of a new serial architecture, allowing the decomposition into real eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The performance of the proposed processor is improved using the systolic architecture. We have achieved very satisfactory results, with a Virtex-E FPGA resource allocation of less than 50% and a processing time per turn of 15.42 s Our immediate action following this research will be to extend the exploitation of our FPGA in real use cases in several sectors such as medical, aeronautical, automotive and space.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and W.A. and I.E.G.; methodology, R.G. and A.S.; software, R.G., W.A. and A.S.; validation, J.F. and I.E.G.; formal analysis, R.G. and A.S.; investigation, I.E.G. and J.F.; resources, J.F. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Umm Al Qura University under grant no 22UQU4361156DSR01.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| LD | Linear Dichroism |

| AOA | Angle Of Arrival |

| MUSIC | MUltiple SIgnal Classification |

| DOA | Direction Of Arrival |

| ESPRIT | Estimation of Signal Parameters via Rotational Invariance Techniques |

| FPGA | Field Programmable Gate Array |

| EVD | EigenValue Decomposition |

| DP (aka PD) | Diagonal Processor |

| NDP (aka NPD) | Non-Diagonal Processor |

| NN | Neural Network |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| LUT | LookUp Table |

| DSPs | Digital Signal Processing Elements |

| FF | Flip-Flop |

| VHDL | Very High-Speed Integrated Circuit Hardware Description Language |

| LE | Logic Element |

| ML | Maximum Likelihood |

| DP | Dual Port |

| FIFO | First In First Out |

| FSM | Finite State Machine |

| LiDAR | Light Detection And Ranging |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Time Complexity.

Table A1.

Time Complexity.

| Algorithms | Time Complexity |

|---|---|

| Jacobi’s algorithm | |

| Hestens method | |

| Tridiagonalization + Symmetric QR iteration | |

| Tridiagonalization + Divide and Conuer method |

References

- Abusultan, M.; Harkness, S.; LaMeres, B.J.; Huang, Y. FPGA implementation of a Bartlett direction of arrival algorithm for a 5.8 ghz circular antenna array. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 6–13 March 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, I.; Mazo, M.; Lazaro, J.L.; Jimenez, P.; Gardel, A.; Marron, M. Novel HW Architecture Based on FPGAs Oriented to Solve the Eigen Problem. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2008, 16, 1722–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J. The Algebraic Eigenvalue Problem; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. Multiple emitter location and signal parameter estimation. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1986, 34, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.U.; Kwon, B.H. Forward/backward spatial smoothing techniques for coherent signal identification. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1989, 37, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.A.; Tayem, N.; Butt, M.O.; Soliman, A.H.; Alhamed, A.; Alshebeili, S. FPGA Hardware Implementation of DOA Estimation Algorithm Employing LU Decomposition. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 17666–17680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.A.; Tayem, N.; Soliman, A.H.; Radaydeh, R.M. FPGA-Based Hardware Implementation of Computationally Efficient Multi-Source DOA Estimation Algorithms. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 88845–88858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Jeon, H.; Lee, S.; Jung, Y. Scalable ESPRIT Processor for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation of Frequency Modulated Continuous Wave Radar. Electronics 2021, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadoon, M.A.G.; Ali, N.T.; Dama, Y.; Zuid, A.; Jones, S.M.R.; Abd-Alhameed, R.A.; Noras, J.M. A New Low Complexity Angle of Arrival Algorithm for 1D and 2D Direction Estimation in MIMO Smart Antenna Systems. Sensors 2017, 17, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumar, O.A.; Siyau, M.F.; Sattar, T.P. Comparison between MUSIC and ESPRIT direction of arrival estimation algorithms for wireless communication systems. In Proceedings of the The First International Conference on Future Generation Communication Technologies, London, UK, 12–14 December 2012; pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, I.; Mazo, M.; Lázaro, J.L.; Gardel, A.; Jiménez, P.; Pizarro, D. An Intelligent Architecture Based on Field Programmable Gate Arrays Designed to Detect Moving Objects by Using Principal Component Analysis. Sensors 2010, 10, 9232–9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.E.; Rojas, J.F.; Goberville, N.A.; Alzubi, H.; AlRousan, Q.; Wang, C.R.; Huff, S.; Rios-Torres, J.; Ekti, A.R.; LaClair, T.J.; et al. Development of an Energy Efficient and Cost Effective Autonomous Vehicle Research Platform. Sensors 2022, 22, 5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Suganuma, N.; Yoneda, K.; Aldibaja, M. Real-time object classification for autonomous vehicle using LIDAR. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Informatics and Biomedical Sciences (ICIIBMS), Okinawa, Japan, 24–26 November 2017; pp. 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; He, Q.; Liu, Y. Accelerating Parallel Jacobi Method for Matrix Eigenvalue Computation in DOA Estimation Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 6275–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Huang, K. A Low Latency NN-Based Cyclic Jacobi EVD Processor for DOA Estimation in Radar System. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, ISCAS 2020, Sevilla, Spain, 10–21 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedsaid, A.; Amira, A.; Bouridane, A. Improved SVD systolic array and implementation on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Conference on Field-Programmable Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 15–17 December 2003; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andraka, R. A Survey of CORDIC Algorithms for FPGA Based Computers. In Proceedings of the 1998 ACM/SIGDA Sixth International Symposium on Field Programmable Gate Arrays, FPGA 1998, Monterey, CA, USA, 22–24 February 1998; Cong, J., Kaptanoglu, S., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, I.B.; Jiménez, P.; Mazo, M.; Lázaro, J.L.; Vicente, A.G. Implementation in Fpgas of Jacobi Method to Solve the Eigenvalue and Eigenvector Problem. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), Madrid, Spain, 28–30 August 2006; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malioutov, D.; Cetin, M.; Willsky, A.S. A sparse signal reconstruction perspective for source localization with sensor arrays. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2005, 53, 3010–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xie, L.; Zhang, C. Off-grid direction of arrival estimation using sparse Bayesian inference. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 61, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xie, L.; Zhang, C. A discretization-free sparse and parametric approach for linear array signal processing. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 4959–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Khare, K. CORDIC-based window implementation to minimise area and pipeline depth. IET Signal Process. 2013, 7, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Delosme, J.; Morf, M. Highly Concurrent Computing Structures for Matrix Arithmetic and Signal Processing. Computer 1982, 15, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto Oliveira de Souza Junior, C.; Bispo, J.; Cardoso, J.M.P.; Diniz, P.C.; Marques, E. Exploration of FPGA-Based Hardware Designs for QR Decomposition for Solving Stiff ODE Numerical Methods Using the HARP Hybrid Architecture. Electronics 2020, 9, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bouganis, C.; Cheung, P.Y.K. Hardware architectures for eigenvalue computation of real symmetric matrices. IET Comput. Digit. Tech. 2009, 3, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H.; Vandenbosch, G.A.E. Hardware acceleration of MUSIC based DoA estimator in MUBTS. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP 2014), The Hague, The Netherlands, 6–11 April 2014; pp. 2561–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wei, P. Hardware efficient architectures of improved Jacobi method to solve the eigen problem. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Computer Engineering and Technology, Chengdu, China, 16–18 April 2010; Volume 6, pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, R.P.; Luk, F.T. The Solution of Singular-Value and Symmetric Eigenvalue Problems on Multiprocessor Arrays. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1985, 6, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmel, J.; Veselic, K. Jacobi’s Method is More Accurate than QR. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 1992, 13, 1204–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, D.; Leupers, R.; Ascheid, G. A Scalable, Multimode SVD Precoding ASIC Based on the Cyclic Jacobi Method. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2016, 63, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, M.; Biagetti, G.; Crippa, P.; Falaschetti, L.; Manoni, L.; Turchetti, C. Singular Value Decomposition in Embedded Systems Based on ARM Cortex-M Architecture. Electronics 2021, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ichige, K.; Arai, H. Design of Jacobi EVD processor based on CORDIC for DOA estimation with MUSIC algorithm. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications, Lisboa, Portugal, 15–18 September 2002; pp. 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Huang, X.; Fu, H.; Yang, G. Jacobi Solver: A Fast FPGA-based Engine System for Jacobi Method. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 6, 4459–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, M.; Pasca, B. High-Performance QR Decomposition for FPGAs. In Proceedings of the FPGA’18, 2018 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays, Monterey, CA, USA, 25–27 February 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devendra, M.; Manjunathachari, K. DOA estimation of a system using MUSIC method. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Engineering Systems, Guntur, India, 2–3 January 2015; pp. 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Peng, C.; Jiang, X.; Ouyang, S. Hardware design and implementation of DOA estimation algorithms for spherical array antennas. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), Guilin, China, 5–8 August 2014; pp. 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.D. Off-Grid Direction-of-Arrival Estimation Using Coprime Array Interpolation. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2018, 25, 1710–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Götze, J.; Jan, G.E. Parallel Jacobi EVD Methods on Integrated Circuits. VLSI Des. 2014, 2014, 596103:1–596103:9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ichige, K.; Arai, H. Implementation of FPGA based fast DOA estimator using unitary MUSIC algorithm [cellular wireless base station applications]. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE 58th Vehicular Technology Conference. VTC 2003-Fall (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37484), Orlando, FL, USA, 6–9 October 2003; Volume 1, pp. 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).