Abstract

Theabrownins are macromolecular compounds with many hydroxyl, carboxyl, and phenolic functional groups. They are usually extracted from dark tea, in which they are present at low concentrations. In this paper, a low-cost microbial liquid fermentation method was established by inoculating Aspergillus niger with minced tea extract as the raw material. After applying the Box–Behnken and response surface approach design, the optimum fermentation conditions in the fermentor were determined to be an 8% (80 g/L) sucrose concentration, 1:31 (0.03226 g/mL) solid–liquid ratio, 4.141 × 106 CFU/mL bacterial liquid concentration, 5 d fermentation time, 28 °C fermentation temperature, 187 r/min (rpm) rotation speed, and an oxygenation of 0.5 V/V·min (V). After fermenting about 168 h, the theabrownins content reached the maximum of 28.34%. The total phenolic content of the liquid-fermented theabrownins was 25.74% higher than that of solid fermentation. Acidic functional groups were determined, indicating that the phenolic hydroxyl groups were the main acidic groups of the theabrownins. The antioxidant activity of theabrownins was verified by measuring the potassium ferricyanide reducing power, hydroxyl radical scavenging rate, superoxide anion radical scavenging rate, and 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging rate of solid- and liquid-fermented chabein. The results of this study show that the production of theabrownins by the liquid fermentation of Aspergillus niger is fast, high in yield, and has antioxidant activity, which provides a basis for industrial production of theabrownins.

1. Introduction

Theabrownins (TB) are macromolecular compounds with many hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amino groups [1]. They are soluble in water but insoluble in chloroform, n-butanol, ethyl-acetate, and other organic solvents [2]. Theabrownins are abundant in Pu-erh tea. Theabrownins are mainly derived from the solid-state fermentation of Pu-erh tea. Theabrownins have diverse bioactivities, such as lowering hypertension and hyperglycemia [3,4,5,6], and have antioxidant [5], anti-cancer [7,8,9,10,11], and antimicrobial properties [12]. They also help with weight loss [6,13]. The hydroxyl, carboxyl, and other functional groups in the structure of theabrownins can scavenge DPPH free radicals and have strong antioxidant properties for both hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals [14,15,16]. Therefore, obtaining theabrownins quickly and efficiently is a popular research topic in tea scientific research.

A series of problems such as a long production cycle, low production efficiency, high consumption of human and material resources, high costs, and poor safety have affected the development and utilization of theabrownins obtained from the solid fermentation of Pu-erh tea. Many researchers have increased the theabrownins content of Pu-erh tea [17] by attempting to inoculate it with different microorganisms, supplementing the fermentation with exogenous enzymes, and improving the fermentation conditions [18]. The production of theabrownins by liquid fermentation with specific microorganisms provides a high-efficiency method to control the production environment and can be easily automated [19,20]. Aspergillus niger is the dominant strain in the solid-state fermentation of Pu-erh tea, and when inoculated with Aspergillus niger solid-state fermented tea, the tea sample aroma is strong and pure, with a special mushroom fragrance, and the soup color is dark brown [21].

However, the large amount of waste from green tea production is not reasonably utilized, which affects the economic value of the tea industry. Therefore, in this study, in order to produce theabrownins quickly and efficiently, we report a new, rapid, and highly controlled process for consistently producing theabrownins from infusions of crushed green tea via the liquid fermentation of Aspergillus niger.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemical Reagents

Crushed green tea was obtained from Yiwanjia Ecological Agriculture Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhenyuan County, Guizhou, China). Anhua dark tea was obtained from Anhua Jindao Tea Co., Ltd. (Hunan, China), and the fermentation process of Anhua dark tea is the traditional way, including killing green, rolling, piling, and drying.

All chemical reagents used were analysis-grade, unless otherwise stated. Ferric chloride, Tris HCl, 1,1-diphenyl-2-trinitrophenyl hydrazine, and gallic acid (GA) were obtained from Thermo Fisher (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Calcium acetate, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, and disodium hydrogen phosphate were purchased from Chengdu Jinshan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). N-butanol and ethyl acetate were purchased from Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Barium chloride and pyrogallol were purchased from Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Chloroform and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Chongqing Chuandong Chemical Group Co., Ltd. (Chongqing, China). Oxalate was purchased from Chongqing Jiangchuan Chemical Co., Ltd. (Chongqing, China). Vitamin C (VC) was purchased from Shanghai Shisi Hewei Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Salicylic acid was purchased from Beijing Solebo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Absolute ethanol was purchased from Tianjin Beichen Fangzheng Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). Ferrous sulfate was purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China).

2.2. Strains

Aspergillus niger (accession number: CCTCCNO: M2020905) was isolated by the Institute of Fungal Resources, Guizhou University. It was stored at 4 °C on potato dextrose agar medium (PDA). Before inoculation, Aspergillus niger was cultured on PDA at 28 °C for 5 d [22]. The spores were washed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution. The spore concentration was adjusted to 1 × 107 CFU/mL to inoculate the crushed green tea infusion [23].

2.3. Preparation of Crushed Green Tea Infusion

Crushed green tea powder infusions were obtained by boiling in water at 100 °C for 15 min (1 g tea powder in 50 mL water). It was shaken for 3 min, and then the slurry was filtered to obtain a clear tea infusion [4]. This infusion was pasteurized (80 °C, 30 min) [24] and cooled down to 25 °C to inoculate Aspergillus niger.

2.4. Optimization of Theabrownins Liquid Fermentation Process

Based on a previous single-factor experiment, the optimal culture parameters of each single factor affecting the production of theabrownins were determined [25]. The concentration of sucrose was 8% (80 g/L), the ratio of material to liquid was 1:30, and the bacterial concentration was 1 × 107 CFU/mL. The mixture was fermented at 28 °C for 5 d.

2.4.1. Single-Factor Plackett–Burman Experimental Design

The formation of theabrownins is influenced by many factors; therefore, according to the results of the previous single-factor pre-experiment, the Plackett–Burman design was used to determine the significant influencing factors. The sucrose concentration (SC), feed–liquid ratio (FLR), bacterial concentration (BC), fermentation days (FD), fermentation temperature (FT), and rotation speed (RS) were optimized. Each variable was represented by high and low levels. A Plackett–Burman experiment (N = 12) was designed (Table 1), and significant influencing factors were determined through analysis [26,27].

Table 1.

Plackett–Burman experimental design factor levels and codes.

2.4.2. Significant Factors Box–Behnken Test Design

In this paper, based on the Plackett–Burman test, the material–liquid ratio, bacterial liquid concentration, and rotational speed were taken as independent variables. The response surface methodology of three factors and three levels was designed by Box–Behnken test [28,29,30]. The independent factors were coded as −1, 0, and +1, which indicated low, medium, and high levels. The response value of the theabrownins content was used to examine the degree of influence of each factor on the response value to determine the optimal culture conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Box–Behnken test design factor level and code.

3. Fermenter Study

The optimal culture conditions obtained by the Box–Behnken test were further verified for 10 L and 100 L fermentors. The fermentation broth seeds cultured for 24 h were inoculated in the tea broth of the fermenter at 8%. The fermentation temperature was 28 °C, the oxygen flux was 0.5 V/(V, min), and the speed was 187 r/min to screen the fermentation time.

Determination of Theabrownins Content

The theabrownins content was determined by a systematic method with a slight modification [18]. The sample (15 mL) was shaken in n-butanol (15 mL) for 3 min. After the layers were separated, the aqueous layer (2 mL) was added to 2 mL of distilled water, 2 mL of saturated oxalic acid solution, and diluted to 25 mL with 95% ethanol. The absorbance (A) was measured at 380 nm with an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Shanghai Jinghua Technology Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and 95% ethanol was used as a blank control. The calculation formula of theabrownins content was:

where m is the mass of the sample (g); w (wt.%) is the moisture content of the sample; 7.06 is a conversion factor under the same operating conditions. The multiplier of 0.72 was used as a correction factor to represent changes in the ratio of tea powder to water before and after fermentation.

4. Determination of the Chemical Composition of Theabrownins

4.1. Theabrownins Extraction

- (1)

- Solid-state fermented theabrownins extraction. Pulverize Anhua dark tea and pass it through a 40 mesh sieve and then soak it with 95% ethanol (1:9, w:v) at room temperature until colorless. Ethanol was removed by suction filtration, and the tea residue was extracted in 50 °C distilled water (1:20, w:v) three times (3 h each time). The combined tea solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant was concentrated by rotary evaporation (55 °C) to 1/10 of its initial volume. The concentrate was extracted twice with chloroform (1:1, v:v) and three times with ethyl acetate (1:1, v:v), and the aqueous layer obtained after extraction with n-butanol four times (1:1, v:v) was mixed with absolute ethanol for 12 h (1:4, v:v). Then, it was centrifuged at 4000× g rpm for 20 min, and the precipitate was collected and vacuum freeze-dried to obtain solid-state fermented theabrownins samples, which were stored at 4 °C for later use [31].

- (2)

- Liquid-state fermented theabrownins extraction [32] involved sterilizing the broth at 80 °C for 30 min after vacuum suction filtration, followed by concentration by rotary evaporation (55 °C) to 1/10 of its initial volume. The subsequent experimental steps were the same as those of solid-state fermentation to obtain theabrownins. Aspergillus niger liquid-fermented theabrownins samples were stored at 4 °C for later use.

4.2. Detection of Tea Polyphenols in Theabrownins

- (1)

- Preparation of gallic acid standard curve: Gallic acid standard solutions were prepared with concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg/mL. In total, 10% Folin phenol reagent was added to 1.0 mL of the standard solutions and shaken. After reacting for 5 min, 4 mL of 7.5% Na2CO3 solution was added and shaken for 1 h at room temperature. The absorbance at 765 nm was measured with a glass cuvette, and the standard curve was drawn.

- (2)

- Detection of total phenolic content in theabrownins: 1 mL of the prepared 0.2 mg/mL theabrownins solution was transferred to a test tube. The subsequent steps were performed according to the above detection steps. This was calculated as follows:where A is the absorbance of the sample test solution (µg/mL), V is the sample volume (mL), d is dilution factor (1 mL was typically diluted to 100 mL—a dilution factor of 100), SLOPEstd is the gallic acid standard curve slope, w is the sample dry matter content (%), and m is the sample mass (g).

4.3. Determination of Acidic Functional Groups in Theabrownins

(1) A sample (0.02 g) was added to 20 mL of 0.1 M NaOH, diluted to 50 mL with BaCl2 solution (0.75 M), shaken for 30 min, and filtered quickly. The residue was washed in a volumetric flask. The filtrate was titrated with 0.1 M HCl, and the pH of 8.4 was used as the endpoint. A blank test was also conducted [33]. This was calculated as follows:

where is the titration volume (mL) of HCl standard solution, V2 is the volume of the HCl standard solution consumed by titration (mL), M1 is the HCl standard solution concentration (M), and m1 is the sample mass (g).

(2) Determination of carboxyl groups: A 0.05 g sample was added to 10 mL of NaOH solution (0.1 M) and then shaken to fully dissolve the sample. Then, 10 mL of 0.1 M HCl solution was added, diluted to 50 mL with Ca(CH3COO)2 (1 M), and shaken for 20 min. Then, the solution was filtered, and the residue and volumetric flask were washed with distilled water without carbon dioxide. The filtrate was titrated with 0.1 M NaOH standard solution, the titration endpoint was pH 8.4, and a blank test was conducted [34]. This was calculated as follows:

where V3 is the volume of NaOH standard solution consumed by blank titration, V4 is the volume of NaOH standard solution consumed by sample titration, M2 is the concentration of the NaOH standard solution, and m2 is the mass of the sample (g).

4.4. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of Theabrownins

4.4.1. Determination of the Reducing Power of Potassium Ferricyanide

Phosphate buffer solution (2.5 mL, pH 6.6, 0.2 M) and 2.5 mL of 1% (w/v) potassium ferricyanide solution were added to 1 mL of solid-state fermented theabrownins, liquid-fermented theabrownins, and VC, respectively, and the reaction was carried out in a water bath at 50 °C for 20 min [35]. Then, it was quickly cooled, 1 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 3000× g r/min for 10 min. Distilled water (2.5 mL) and 0.5 mL of 0.1% ferric chloride were added to 2.5 mL of the supernatant, mixed well, and then allowed to stand for 10 min [36]. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm.

4.4.2. Hydroxyl Radical (OH) Scavenging Ability of Theabrownins

In total, 2 mL of FeSO4 solution, 2 mL of H2O2 solution (6 mM), and 2 mL of salicylic acid solution (6 mM) were added to 1 mL of solid-state fermented theabrownins solution, 1 mL of liquid-fermented theabrownins solution, and 1 mL of VC solution, respectively. The mixtures were centrifuged at 5000× g r/min for 5 min after standing for 30 min. Then, the absorbance A1 at 510 nm was measured. A blank control was set up, and the absorbance A0 was measured. The same volume of distilled water was used to replace the salicylic acid solution, and the absorbance A2 of the sample solution was measured [37,38]. This was calculated as follows:

where A0 is the absorbance of the blank, A1 is the absorbance of the sample, and A2 is the absorbance of the sample in the system.

4.4.3. Superoxide Anion (O2−•) Scavenging Ability of Theabrownins

Tris-HCl buffer solution (4.5 mL, pH 8.2, 50 mM) was preheated in a water bath at 25 °C for 20 min. Then, the preheated solution was added to 1 mL of solid-state fermented theabrownins solution, 1 mL of liquid-fermented theabrownins solution, and 1 mL of VC solution, respectively. Then, 0.4 mL of pyrogallol solution (25 mM) was added, mixed well, and reacted in a 25 °C water bath for 5 min. Then, 1 mL of HCl (8 M) solution was added to stop the reaction, and the absorbance B1 at 299 nm was measured. The same volume of distilled water was used to replace the pyrogallol solution, and the absorbance B2 of the sample solution was measured [39,40]. This was calculated as follows:

where B0 is the absorbance of the blank, B1 is the absorbance of the sample, and B2 is the absorbance of the sample in the system.

4.4.4. Theabrownins Scavenging DPPH Free-Radical Ability

A DPPH free-radical solution (2 mL; 2 × 10−4 M) prepared with anhydrous ethanol was added to 2 mL of the solid-state fermented theabrownins solution, liquid-fermented theabrownins solution, and VC solution. The mixtures were reacted for 30 min in the dark, and their absorbance at 518 nm C1 was measured. To eliminate the sample’s influence, 2 mL of the sample and 2 mL of absolute ethanol mixture were used to measure the absorbance, C2, [41,42]. The calculation formula is as follows:

where C0 is the absorbance of the blank, C1 is the absorbance of the sample, and C2 is the absorbance of the sample in the system.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Plackett–Burman Experimental Results

Through Plackett–Burman experimental and variance analysis (Table 3 and Table 4), the significant influencing factors affecting theabrownins production were screened from six factors.

Table 3.

Plackett–Burman experimental design and response values.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance in Plackett–Burman experimental analysis.

Using Design Expert 10 software (Statease Inc. Minneapolis, MN, USA) for data processing, the F-value of the model was 61.91, which is very significant (p < 0.01). The total determination coefficient of the model was R2 = 98.41%, and the correction determination coefficient was R2adj = 99.39%, indicating that the test data can be explained by the model. The single factors affecting the production of theabrownins were X2 > X3 > X6 > X5 > X4 > X1, among which X2, X3, and X6 had significant effects on the theabrownins content (p < 0.01). Therefore, three significant influencing factors, X2, X3, and X6, were selected for the Box–Behnken test.

5.2. Box–Behnken Test Results

The process for generating the tea browning content was optimized by a Box–Behnken experimental design based on the Plackett–Burman experiment to determine significant influencing factors. To evaluate the mutual interactions of the independent and dependent variables, the R2 value, F-value, and p-value were determined from the modeled responses. The data were analyzed by variance (Table 5). R2 = 95.87% and R2adj = 99.39% for the theabrownins content, indicating significant regression (p < 0.01) and a non-significant lack of fit (p = 0.44 > 0.05). This shows that the model can be used to optimize the process to produce theabrownins by Aspergillus niger fermentation. For both responses, the results indicate that the degree of precision was high, and the experimental data were reliable. The results show that the model can be used to optimize the process to produce theabrownins by Aspergillus niger. The quadratic polynomial equation obtained by regression fitting was Y = 28.86 + 2.66X2 + 0.67X3 + 0.54X6 + 0.21X2X3 − 0.16X2X6 + 1.13X3X6 −6.01X22 −1.44X32 −1.73X62.

Table 5.

Box–Behnken optimized design and results.

5.3. Response Surface Interaction Analysis

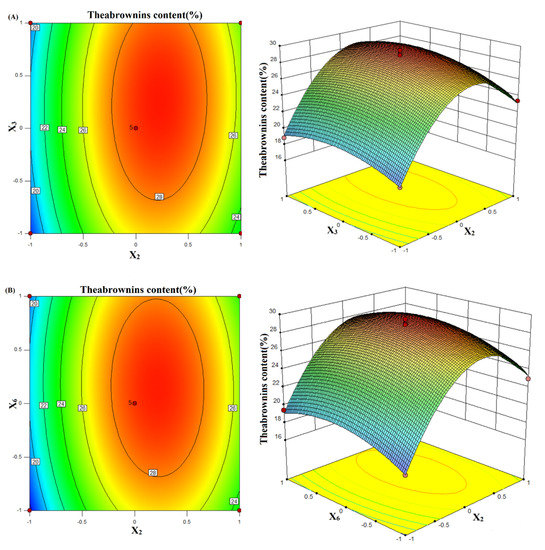

To better understand the interactions between these variables, the response surface diagram of the model was produced. When the feed–liquid ratio (X2) was constant, the theabrownins content gradually increased as the concentration of the bacterial solution (X3) increased (Figure 1A). The maximum theabrownins content was reached when the concentration of the bacterial solution was about 1 × 107 CFU/mL. A higher or lower concentration of the bacterial solution resulted in lower theabrownins content. At the same time, when the concentration of the bacterial solution was constant, the content of theabrownins gradually increased with the material–liquid ratio. The theabrownins content reached the maximum when the solid-to-liquid ratio was 1:30. A higher or lower ratio resulted in lower theabrownins content. The ovality in the contour line was smaller, which proved that the interaction between the two factors had no significant effect on the theabrownins content. It can be seen from Table 6 that the p-value of the AB interaction = 0.3678 > 0.05, indicating an insignificant impact.

Figure 1.

Contour line and response surface of the effect of the interaction between the feed-liquid ratio (X2) and bacterial concentration (X3) on the theabrownins content (A). Contour lines and response surface of the effect of the interaction of feed–liquid ratio (X2) and rotation speed (X6) on the theabrownins content (B). Contour lines and response surface of the effect of the interaction of bacterial concentration (X3) and rotation speed (X6) on the theabrownins content (C).

Table 6.

Box–Behnken test variance analysis.

When the rotational speed was constant, the theabrownins content gradually increased with the feed–liquid ratio (X2) (Figure 1B). When the ratio was 1:30, the theabrownins content reached the maximum. When the feed–liquid ratio continued to increase, the theabrownins content gradually decreased. When the feed–liquid ratio remained unchanged, the theabrownins content gradually decreased upon increasing the rotation speed. When the rotation speed (X6) was 180 r/min, the theabrownins content reached the maximum value, and then upon further increasing the rotation speed, the theabrownins content gradually decreased again. The ovality in the contour line was smaller, which proved that the interaction of the two factors had no significant effect on the theabrownins content. It can be seen from Table 6 that the p-value of the AC interaction = 0.4954 > 0.05, and the effect was not significant.

When the rotation speed (X6) was constant, the theabrownins content gradually increased with the bacterial concentration (X3) (Figure 1C). When the concentration of the bacterial solution was about 1 × 107 CFU/mL, the theabrownins content reached the maximum value, and the theabrownins content gradually decreased with the continuously increasing the rotation speed. The ellipticity in the contour line was larger, which proves that the interaction between the two factors significantly affected the theabrownins content. Table 6 shows that the p-value of BC interaction was less than 0.01, and the effect was extremely significant.

5.4. Verification of the Predicted Optimal Conditions

The theabrownins content of liquid fermentation using Aspergillus niger was predicted to be 29.341% under the predicted optimal conditions of an 8% (80 g/L) sucrose concentration, 1:31 (0.03226 g/mL) solid–liquid ratio, 4.141 × 106 CFU/ mL bacterial liquid concentration, 5 d, 28 °C, and 187 r/min rotation speed. To confirm the validity of the model, an experiment was conducted using the predicted optimum conditions, and the experimental theabrownins content was (29.07% ± 0.15%). The error value between the predicted and experimental results was 0.93%, confirming the validity of the model.

5.5. Expanded Culture in a 10 L Fermentor

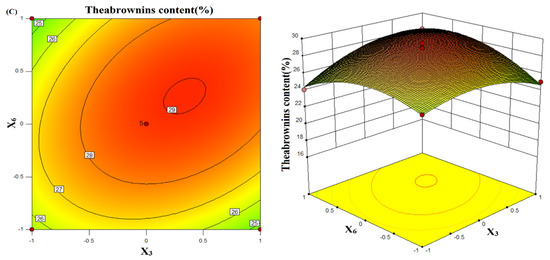

It can be seen from Figure 2 that the curves of theabrownins content and mycelium dry weight in a 10 L fermentor were similar. This indicates that more Aspergillus niger mycelium resulted in a higher extracellular enzymatic activity secreted by Aspergillus niger. The theabrownins content increased upon increasing the mycelium dry weight. At about 168 h, the theabrownins content and mycelium dry weight reached the maximum values of 28.34% and 2.26 g/100 mL, respectively. Subsequently, likely due to autolysis of Aspergillus niger, the enzyme activity and the theabrownins content decreased. The optimal conditions were 7 L of medium in a 10 L fermentor and a fermentation time of 168 h.

Figure 2.

Variation curve of theabrownins content (A) and mycelial dry weight (B) in a 10 L and 100 L fermentor with fermentation time.

5.6. Expanded Culture from a 100 L Fermentor

Figure 2A shows that the curves for theabrownins production were similar when using either a 100 L or 10 L fermentor. The theabrownins content in the early stage when using the 100 L fermentor was higher than of the 10 L fermentor. This may be because of the sufficient nutrients Aspergillus niger proliferated rapidly in the 100 L fermentor. However, due to limited growth space and nutrients gradually depleted, the theabrownins output in the middle and late stages was gradually slowed down. It can be seen from Figure 2B that the mycelium dry weight in the 100 L and 10 L fermentors was roughly the same. When fermented for 168 h, the theabrownins content and mycelium dry weight in the 100 L fermentor reached the maximum level of 27.17% and 2.102 g/100 mL, respectively. Therefore, based on the above results, the expanded culture of theabrownins produced by liquid fermentation in a 100 L fermentor was achieved.

5.7. Analysis of the Chemical Composition of Theabrownins in Liquid Fermentation of Aspergillus niger

5.7.1. Analysis of Total Phenolic Content in Theabrownins

The total phenolic content of liquid-fermented theabrownins was significantly higher than that obtained by solid-state fermentation (p < 0.05). The total phenolic content of liquid-fermented theabrownins was 25.74% (Table 7).

Table 7.

The content of total phenols in theabrownins obtained from solid-state fermentation and liquid-state fermentation.

5.7.2. Determination of Acidic Functional Groups in Theabrownins

There was a significant difference between liquid-fermented theabrownins acidic functional groups and solid-state fermented theabrownins’ acidic functional groups, as shown in Table 8 (p < 0.05). The total acidic groups, carboxyl groups, and phenolic hydroxyl groups in liquid-fermented theabrownins were 27.93%, 7.32%, and 20.28%, respectively (Table 8). The content of phenolic hydroxyl groups was higher than that of carboxyl groups in both fermented theabrownins, indicating that phenolic hydroxyl groups were the main acidic groups of theabrownins, which was consistent with the literature [34].

Table 8.

The content of acidic functional groups of theabrownins in solid and liquid fermentation.

5.8. Antioxidant Activity Analysis of Theabrownins

5.8.1. Determination of the Reducing Power of Potassium Ferricyanide

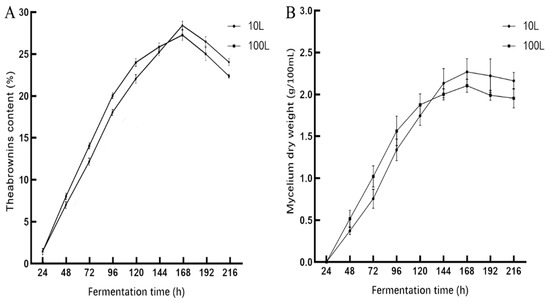

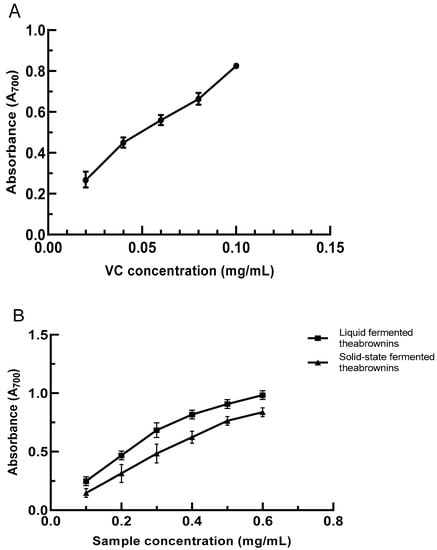

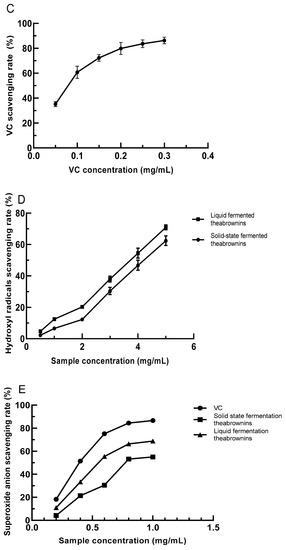

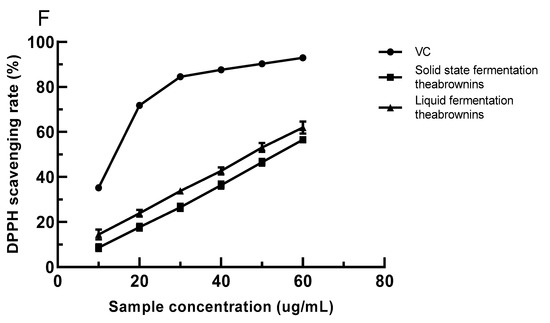

A substance’s reduction ability is a key manifestation of its oxidation resistance. Electron supply capacity is the key to the antioxidant activity of phenolic substances. The electron-donating ability of the substance was evaluated by potassium ferricyanide reduction force method, and the reduction force of the substance was determined; the higher the absorbance at 700 nm, the stronger the reducing force. A stronger reduction ability indicates a higher oxidation resistance. In the concentration range of 0.02–0.1 mg/mL, the reduction force of VC had a linear relationship with concentration (Figure 3A), and the linear regression equation was y = 7.300× + 0.1100 (R2 = 0.9966). In the concentration range of 0.1–0.6 mg/mL, the reduction capacity increased with the concentration. The reduction capacity of theabrownins obtained by solid-state fermentation was less than that of liquid fermentation, but their reduction capacity was lower than that of VC (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) The reducing power of VC concentration; (B) solid- and liquid-fermented theabrownins reducing power; (C) VC scavenging ability of hydroxyl radicals; (D) solid-state and liquid-fermented theabrownins scavenging ability of hydroxyl radicals; (E) the scavenging ability of VC and solid- and liquid-fermented theabrownins on superoxide anion free radicals; (F) the scavenging ability of VC, liquid-fermented, and solid-state fermented theabrownins by DPPH.

5.8.2. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activities

Hydroxyl radicals are strongly oxidizing free radicals generated during human metabolism. They can lead to a series of diseases, such as gastric ulcers and cancers [43]. The phenolic hydroxyl groups of theabrownins can combine with metal ions to prevent the generation of hydroxyl free radicals. Upon increasing the theabrownins concentration in the range of 0.5–5 mg/mL, the scavenging rate of hydroxyl radicals increased. When the concentration of theabrownins was 5 mg/mL, and the clearance rates of theabrownins in solid-state and liquid fermentation were 62.39% and 70.91%, respectively. The scavenging rate of theabrownins to hydroxyl radicals was lower than that of VC (Figure 3C,D).

5.8.3. The Scavenging Ability of Theabrownins to Superoxide Anion Radical (O2−•)

The superoxide anion is a reactive oxygen radical that harms the body by disrupting normal cell functions and affecting amino acids and other biomolecules [44]. When the concentration of theabrownins in solid-state and liquid fermentation was 0.2 mg/mL, the clearance rates were 4.22% and 11.04%, respectively. When the concentration was 1 mg/mL, the clearance rates were 55.07% and 68.78%, representing increases of 92.33% and 83.94%, respectively (Figure 3E). The clearance rate of liquid-fermented theabrownins was better than that of solid-fermented theabrownins, both of which were lower than that of VC. According to the calculated IC50 value, the superoxide radical scavenging effect of the liquid-fermented theabrownins, solid-fermented theabrownins, and VC were 0.5152, 0.4473, and 0.4100 mg/mL, respectively.

5.8.4. The DPPH Free-Radical Scavenging Ability of Theabrownins

DPPH is commonly used to determine the free-radical scavenging ability of materials [41,45]. The scavenging ability of VC was stronger than that of solid- and liquid-fermented theabrownins when the sample concentration was in the range of 10–60 μg/mL (Figure 3F). The scavenging rate of DPPH free radicals was linearly correlated with the solid- and liquid-fermented theabrownins, and the scavenging rate of liquid-fermented theabrownins was higher than that obtained by solid-state fermentation. The IC50 values of VC and liquid- and solid-fermented theabrownins were significantly different (p < 0.05) and were 18.34, 33.11, and 34.18 µg/mL, respectively. The DPPH free-radical scavenging capacity of theabrownins may be linked to their active phenolic hydroxyl groups.

6. Discussion

It is well known that theabrownins are a substance beneficial to the human body [46,47]. It is usually extracted from solid-state fermented Pu-erh tea, which has a long fermentation period and low yield. In previous studies, many researchers have tried to increase the content of theabrownins in Pu-erh tea by inoculating different microbial fermentation [25,37]. Liquid fermentation can better control the fermentation environment, short fermentation, cycle and high yield [37]. In this study, response surface design and Box–Behnken analysis showed that the optimum conditions for the production of theabrownins by liquid fermentation with Aspergillus niger were 8% (80 g/L) sucrose concentration, 1:31 (0.03226 g/mL) solid–liquid ratio, 4.141 × 106 CFU/ mL bacterial liquid concentration, 5 d, 28 °C, and 187 r/min rotation speed, resulting in a high theabrownins content during liquid fermentation by Aspergillus niger. This study shows that the total phenol content of liquid-fermented theabrownins is higher than that of traditional solid-fermented Anhua dark tea, and there was a significant difference between liquid-fermented theabrownins’ acidic functional groups and traditional solid-fermented Anhua dark tea’s acidic functional groups. The hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in the structure of theabrownins can scavenge DPPH free radicals and have strong antioxidant activity against hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals. The bioactive components of theabrownins have attracted more and more attention and are widely used in medical and health foods [7]. In this study, the antioxidant activity of theabrownins by liquid fermentation was verified to be stronger than that of theabrownins by traditional solid-fermented Anhua dark tea.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, crushed green tea from tea processing was used as the raw material and then inoculated with Aspergillus niger for liquid fermentation. Theabrownins were rapidly produced, which greatly reduced the cost and improved the theabrownins production efficiency. This study showed that it was feasible to prepare theabrownins by liquid fermentation of Aspergillus niger using crushed green tea as the raw material. After broken green tea was inoculated with Aspergillus niger for liquid fermentation, the ingredients displayed significant modification. This provides a theoretical basis for the industrial production of theabrownins. Theabrownins produced by the liquid fermentation of broken tea can be further processed and used in functional food ingredients, the food colorant industry, and as a natural food preparation of functional foods, which provides the possibility for the diversified development and utilization of theabrownins.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, C.-Y.L.; investigation, C.W. and C.-Y.L.; resources, X.-Z.Y. and Y.-J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, L.-T.L.; visualization, C.W. and C.-Y.L.; supervision, L.-T.L., funding acquisition, L.-T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Demonstration on the Key Technology of Aroma Material Collection in Green Tea Processing (Qiankehe Support (2021) General 111), the Laboratory Opening Project of Guizhou University (SYSKF2022-020), and the Guizhou Science and Technology Planning Project (Qiankehe Support (2021) General 111) to Litang Lu.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gong, J.; Tang, C.; Peng, C. Characterization of the chemical differences between solvent extracts from pu-erh tea and dian hong black tea by cp–py–gc/ms. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 95, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Peng, C.; Chen, T.; Gao, B.; Zhou, H. Effects of theabrownin from pu-erh tea on the metabolism of serum lipids in rats: Mechanism of action. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, H182–H189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Hong, F.; Yang, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, X. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of pu’er tea extract on the regulation of metabolic syndrome. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2011, 17, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Xue, Z.; Xue, X.; Huang, G.; Huang, K.; He, X.; Xu, W. Hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-atherosclerotic effects of tea before and after microbial fermentation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Peng, Y.; Liu, B.; Cui, W.; Liu, X. Anti-obesity, anti-atherosclerotic and anti-oxidant effects of pu-erh tea on a high fat diet-induced obese rat model. J. Biosci. Med. 2019, 07, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zheng, X.; Ma, X.; Jiang, R.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, S.; Wang, S.; Kuang, J. Theabrownin from pu-erh tea attenuates hypercholesterolemia via modulation of gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jiang, C.; Wu, M.; Mei, R.; Yang, A.; Tao, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhao, X. Theabrownin induces cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest of oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma in different pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 664003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Zhou, L.; Yan, B.; Yan, L.; Liu, F.; Tong, P.; Yu, W.; Dong, X.; Xie, L.; Zhang, J. Theabrownin triggers DNA damage to suppress human osteosarcoma u2 os cells by activating p53 signalling pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 4423–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, H.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Chen, X. Physicochemical and colon cancer cell inhibitory properties of theabrownins prepared by weak alkali oxidation of tea polyphenols. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Song, W.; Wu, Z.; Li, X. Characterization of theabrownins prepared from tea polyphenols by enzymatic and chemical oxidation and its inhibitory effect on colon cancer cells. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Feifei, W.; Wangdong, J.; Bo, Y.; Xin, C.; Yingfei, H.; Weiji, Y.; Wenlin, D.; Qiang, Z.; Yonghua, G. Theabrownin inhibits cell cycle progression and tumor growth of lung carcinoma through c-myc-related mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yen, G.C.; Wang, B.S.; Chiu, C.K.; Yen, W.J.; Chang, L.W.; Duh, P.D. Antimutagenic and antimicrobial activities of pu-erh tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, A.; Du, H.; Liu, Y.; Qi, B.; Yang, X. Theabrownin from fu brick tea exhibits the thermogenic function of adipocytes in high-fat-diet-induced obesity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11900–11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, C.; Gong, J.; Sirisansaneeyakul, S. Antioxidative effect of large molecular polymeric pigments extracted from zijuan pu-erh tea in vitro and in vivo. Kasetsart J.-Nat. Sci. 2013, 47, 739–747. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yan, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Yu, W.; Dong, X.; Yao, L.; Shan, L. Theabrownin induces apoptosis and tumor inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma huh7 cells through ask1-jnk-c-jun pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, S.; Peng, C.; Zhao, D.; Xia, X.; Tan, C.; Wang, Q.; Gong, J. Theabrownin isolated from pu-erh tea regulates bacteroidetes to improve metabolic syndrome of rats induced by high-fat, high-sugar and high-salt diet. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 4250–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, C.; Gong, J. Effects of enzymatic action on the formation of theabrownin during solid state fermentation of pu-erh tea. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2412–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, H.; Gao, X.; Yue, P. High-theabrownins instant dark tea product by aspergillus niger via submerged fermentation: A-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase inhibition and antioxidant activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 5100–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, M.; Chen, M.; Li, M.; Gao, X. Influence of eurotium cristatum and aspergillus niger individual and collaborative inoculation on volatile profile in liquid-state fermentation of instant dark teas. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Durgo, K.; Chisti, Y.; Gong, J.; Sirisansaneeyakul, S.; Komes, D. Physicochemical properties and biological activities of a high-theabrownins instant pu-erh tea produced using aspergillus tubingensis. LWT 2018, 90, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Ma, C.; Ren, X.; Xia, T.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Production of theophylline via aerobic fermentation of pu-erh tea using tea-derived fungi. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, T.; Chen, M.; Zu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Lu, H.; Yue, P.; Gao, X. Untargeted and targeted metabolomics reveal changes in the chemical constituents of instant dark tea during liquid-state fermentation by eurotium cristatum. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Ling, T.-J.; Su, X.-Q.; Jiang, B.; Nian, B.; Chen, L.J.; Liu, M.-L.; Zhang, Z.-y.; Wang, D.-P.; Mu, Y.-Y.; et al. Integrated proteomics and metabolomics analysis of tea leaves fermented by aspergillus niger, aspergillus tamarii and aspergillus fumigatus. Food Chem. 2020, 334, 127560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salar, S.; Jafarian, S.; Mortazavi, A.; Nasiraie, L.R. Effect of hurdle technology of gentle pasteurisation and drying process on bioactive proteins, antioxidant activity and microbial quality of cow and buffalo colostrum. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 121, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, M.; An, T.; Zu, Z.; Song, P.; Chen, M.; Yue, P.; Gao, X. Preparation of instant dark tea by liquid-state fermentation using sequential inoculation with eurotium cristatum and aspergillus niger: Processes optimization, physiochemical characteristics and antioxidant activity. LWT 2022, 162, 113379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Gao, X.; Yue, P. Multiple responses optimization of instant dark tea production by submerged fermentation using response surface methodology. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.S.A.; Shindia, A.A.; Ali, G.S.; Yassin, M.A.; Hussein, H.; Awad, S.A.; Ammar, H.A. Production and bioprocess optimization of antitumor epothilone b analogue from aspergillus fumigatus, endophyte of catharanthus roseus, with response surface methodology. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2021, 143, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, J.P.; Manikandan, S.; Thirugnanasambandham, K.; Nivetha, C.V.; Dinesh, R. Box–behnken design based statistical modeling for ultrasound-assisted extraction of corn silk polysaccharide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Dao, T.P.; Nguyen, D.C.; Lam, T.D.; Do, S.T.; Toan, T.Q.; Huong, N.; Vo, D.V.; Giang, B.L.; Nguyen, T.D. Application of box–behnken design with response surface methodology for modeling and optimizing microwave-assisted hydro-distillation of essential oil from citrus reticulata blanco peel. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 542, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, L.; Liao, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Zeng, L. Effects of brewing conditions on the phytochemical composition, sensory qualities and antioxidant activity of green tea infusion: A study using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2018, 269, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Qi, G.; Xu, T.; Chen, S.; Liu, T.; Huang, Y. Optimal extraction parameters of theabrownin from sichuan dark tea. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Du, L.; Xiao, D.; Li, C.; Xu, Y. Comparative study on theabrownins in pu-erh tea and its powder fermented in liquid state. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 30, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vattem, D.A.; Lin, Y.T.; Labbe, R.G.; Shetty, K. Phenolic antioxidant mobilization in cranberry pomace by solid-state bioprocessing using food grade fungus lentinus edodes and effect on antimicrobial activity against select food borne pathogens. Innov. Food Sci. Emerging Technol. 2004, 5, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Gong, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; He, J.; Li, B. Quantitative determination of functional groups in theabrownine from pu-erh tea based on bacl_2 and ca(ch_3coo)_2 precipitation methods. Chem. Ind. For. Prod. 2010, 30, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tarafdar, A.; Kumar, Y.; Kaur, B.P.; Badgujar, P.C. High-pressure microfluidization of sugarcane juice: Effect on total phenols, total flavonoids, antioxidant activity, and microbiological quality. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, l. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from four auriculariales. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 229, 115407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Ma, C.; Ma, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, B.; Xia, T. Comparative analysis of chemical constituents and antioxidant activity in tea-leaves microbial fermentation of seven tea-derived fungi from ripened pu-erh tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 142, 111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Feng, C.; Wang, X.; Gu, H.; Yang, L. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils from barks of pinus pumila using microwave-assisted hydrodistillation after screw extrusion treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 166, 113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, S.; Marklund, G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 47, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Improved pyrogallol autoxidation method: A reliable and cheap superoxide-scavenging assay suitable for all antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabalan, R.; Subathradevi, P.; Marimuthu, S.; Sathishkumar, M.; Swaminathan, K. Changes in free-radical scavenging ability of kombucha tea during fermentation. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettasinghe, M.; Shahidi, F. Scavenging of reactive-oxygen species and dpph free radicals by extracts of borage and evening primrose meals. Food Chem. 2000, 70, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutas, B.E. The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: Current state. Nutr. J. 2015, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Fan, C.; Dong, W.; Gao, B.; Yuan, W.; Gong, J. Free radical scavenging and anti-oxidative activities of an ethanol-soluble pigment extract prepared from fermented zijuan pu-erh tea. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, A.; García-Borrego, A.; Jiménez-Araujo, A.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; Sindic, M.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G. Phenolic extracts obtained from thermally treated secondary varieties of dates: Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Kim, E.-M.; Lee, E.-S.; Park, N.H.; Hong, Y.D.; Jung, J.-Y. Theabrownin in black tea suppresses uvb-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression in hacat keratinocytes. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2022, 27, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Shan, B.; Peng, C.; Tan, C.; Wang, Q.; Gong, J. Theabrownin-targeted regulation of intestinal microorganisms to improve glucose and lipid metabolism in goto-kakizaki rats. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 1921–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).