Abstract

Technology has become an essential part of the translation profession. Nowadays, computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools are extensively used by translators to enhance their productivity while maintaining high-quality translation services. CAT tools have gained popularity given that they provide a useful environment to facilitate and manage translation projects. Yet, little research has been conducted to investigate the usability of these tools, especially among Arab translators. In this study, we evaluate the usability of CAT tool from the translators’ perspective. The software usability measurement inventory (SUMI) survey is used to evaluate the system based on its efficiency, affect, usefulness, control, and learnability attributes. In total, 42 participants completed the online survey. Results indicated that the global usability of these tools is above the average. Results for all usability subscales were also above average wherein the highest scores were obtained for affect and efficiency, and the lowest scores were attributed to helpfulness and learnability. The findings suggest that CAT tool developers need to work further on the enhancement of the tool’s helpfulness and learnability to improve the translator’s experience and satisfaction levels. Further improvements are still required to increase the Arabic language support to meet the needs of Arab translators.

1. Introduction

Computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools are extensively used among translators to enhance their productivity, while concurrently allowing them to maintain high-quality translation services. According to Bowker [1], CAT tools can be defined as “any type of computerized tool that translators use to help them conduct their jobs.” These systems are designed to assist human translators in the production of translations. In the early 1980s, the American company Automated Language Processing Systems (ALPS, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) released the first commercially available CAT software (ALPS, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), the ALPS system. This early version included several tools, such as (among others) multilingual word processing, automatic dictionary, and terminology consultation [2]. With the advances in technology and reduction of their costs, more sophisticated systems have been developed over the years that offer advanced functionality and reasonable prices. Nowadays, the advances in translation technologies involve a shift toward cloud-based systems that provide a platform-independent environment to facilitate and manage translation projects.

Many researchers believe that advances in translation technology are need-driven, especially with the expansion of digital content and online users [1,2]. The constant demand on localization resulted in an increased pressure on translators to produce fast, yet high-quality translations. This shift in the translation industry placed a considerable importance on the technical skills of translators and their abilities to use CAT systems. Thus, many translator training programs have integrated technology in their curricula, thus offering translation trainees the opportunity to learn and use these tools.

However, research on the usability of these systems and the level of satisfaction among their users is rather scarce [3,4,5]. This research gap is more evident among Arab translators. Consequently, in this study, we examine the usability of CAT tools from the translator’s perspective. A software usability measurement inventory (SUMI) (http://sumi.uxp.ie/) survey is used to assess the system’s efficiency, affect, usefulness, control, and learnability attributes. The study’s findings are hoped to provide CAT tool developers with design directions based on the translator perspectives on the usability of these tools.

2. Related Work

2.1. Computer-Assisted Translation

CAT is a relatively new field that can be traced back to the 1980s along with the shift from machine translation with the use of computers to aid human translators. According to the European Association of Machine Translation, CAT tools refer to “translation software packages that are designed primarily as an aid for the human translator in the production of translations (http://www.eamt.org/index.php).” Unlike machine translation systems, in CAT, the translator is in charge of the translation process, while the use of these tools enhances the productivity by saving time and efforts. This is especially evident with repetitive tasks, such as searching for terms and maintaining consistency.

Modern CAT software, e.g., SDL Trados (SDL plc, Berkshire, UK), MemoQ (memoQ Translation Technologies, Budapest, Hungary), Wordfast (Wordfast LLC, New York, NY, USA), Memsource (Memsource a.s, Praha, Czech Republic) etc., support various functions to facilitate the translator’s job including the following:

- Translation Memory (TM): The TM is a database that stores the texts and their translations in the form of bilingual segments. They operate by providing the translators with suggestions by automatically searching for similar segments. This tool allows the translators to recycle or “leverage” their previous translations, especially with similar or repetitive texts without the need to re-translate [1,2].

- Terminology Management: This component resembles the translation memory in the reusability of segments; however, it works on a term level. This allows the translators to create a database to store and retrieve terms related to a specific field, client, or project. Once the term base is created, the translator has the ability to manually search for a specific term or allow the system to automatically search and display potential matches. The main advantage of these tools, in addition to saving time and efforts, is the enhancement of the translation consistency when translating terminology, especially in group projects where more than one translator is working on the same task [1,6].

- Project Management PM: The increased demand on translations and the expansion of the translation projects required the development of a system to support the management and automation of the translation process [7]. These tools include collaboration functions to increase team efficiency and consistency. Accordingly, these features enable the invitation of collaborators to edit and/or review translations within the system interface and allow collaborations to work in real-time on translation tasks. Other collaborative features also include segment edit history and tracking. Most PM software include a budgeting feature to allow the calculation of the expenditure and revenues, reporting and analytics tools used to help track translation progress, create and assign tasks to translators, and the evaluation of the task deadlines.

- Supporting Tools: Based on the degree of sophistication, most CAT packages come with supporting tools and functions, such as (a) a translation editor that supports bilingual file formats (the editor has several features similar to word processing programs, such as spell checkers and editing tools); (b) an optical character recognition (OCR) tool used to convert a machine-printed or handwritten text image into an editable text format; (c) a segment analyzer, to analyze the translation files to assist the translator understand how much work a translation will require based on the identification of texts that have already been translated and the type of texts that require translations and similarity rate calculations; (d) an alignment tool to automatically divide and link the source text segments and their translations to help create a translation memory more quickly; (e) a machine translation engine; and (f) quality assurance features.

2.2. CAT Tools Among Arab Translators

Despite the increased use of CAT tools among translators and language service providers around the world, several researchers have noticed reluctance in adopting these technologies in the Arab world [8,9,10,11,12,13].

Alotaibi [10] argues that this could be related to the negative attitudes toward Arabic machine translation that has failed to produce fully automated, high-quality outputs in the past. As a result, this reinforced the idea that there is no role for technology in the translation process. The complications of these tools can hinder their use among Arab translators. Alanazi [13] suggests that these tools sometimes fail to handle Arabic owing to its complex nature. Arabic has a rich morphology system in which words contain complex inflections. Unlike European languages, Arabic has a unique diacritic mark system, a text direction from right-to-left, and a different syntactic structure compared with other languages that render computer-assisted translation challenging and unreliable. In addition, earlier versions of CAT tools had several incompatibility issues with non-Roman character sets. The accuracy of Arabic OCR, segmentation, and alignment tools was disappointing and required a large amount of post-editing. These challenges were reported in several studies. In the study conducted by Thawabteh [9] to evaluate the challenges faced by Arab translators when they used CAT tools, the researcher highlighted several linguistic and technical limitations that included the inability to manage Arabic diacritics, morphological analysis, matching, and segmentation. The inability to convert files to readable forms, differences in text directions, alignment tools, and the ability to deal with tags were among the technical limitations reported in other studies [8,12,13].

Over the years, researchers and companies have worked closely on enhancing the compatibility of these systems and many of these tools can now handle various languages with acceptable levels of accuracy. However, more research is still needed to assess the usability and functionality of these tools with various users and in different contexts.

2.3. Usability of CAT

According to ISO [14,15], usability can be defined as “the capability of a software product to be understood, learnt, used, and that is attractive to the user when used in specified conditions.” It is considered as a key factor in software development and design. Usability involves three distinct attributes: (1) Effectiveness, i.e., the accuracy and completeness with which users achieve certain goals; (2) efficiency, i.e., the link between the accuracy and completeness with which users achieve certain goals and the resources expended in achieving them; and (3) satisfaction, i.e., the users’ comfort with and positive attitudes toward the use of the software [16].

Few studies examined the usability of some CAT tools [3,5,17,18,19]. These studies focused on the advantages and disadvantages of CAT tools from the translators’ perspectives that aimed at encouraging user-centered software design that takes into account user needs. In Lagoudaki [3], 874 professional translators were asked to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of translation memory systems. Several needs related to the functionality of these systems were identified, such as resource building, project management and quality control, search and translation assembly capabilities, and the facilitation of collaboration. The study revealed that usability and the needs of end-users are usually overlooked during the design and development of TM systems. The researcher suggests that software developers must make sure they address expected requirements, performance requirements, as well as existing requirements to satisfy users’ needs.

An ethnographic study by Asare [17] examined the perceptions of translators on CAT tool usability at a translation agency. Fourteen professional translators who worked in different organizational settings were observed and interviewed. The study revealed that although the translators expressed positive attitudes toward the translation technology, they also expressed some dissatisfaction with regard to the user interfaces, complicated features, and the lack of flexibility in these tools. These factors can impact the translation workflow and cause frustration. The findings show that there is a strong need for the optimization of translator workplaces and for the improvement of current translation environment tools.

Another ethnographic study was conducted by LeBlanc [18] in three translation firms in Canada that focused on the advantages and disadvantages of TMs when used at the workplace. Interviews and shadowing techniques were used to collect data on the translator perceptions of technology-enhanced working environments. The study found that most of the participants agreed that CAT tools enhanced the translation consistency and reduced repetitive work. However, their dissatisfaction revolved around the tool’s conception or design.

Vargas–Sierra [5] conducted a usability study to assess the students’ perception of SDL Trados Studio (SDL plc, Berkshire, UK), an extensively used desktop CAT software. The researcher asked 95 translation students to evaluate the efficiency, affect, usefulness, control, and learnability attributes of the software with the use of the SUMI questionnaire. Results showed that student opinions about the global usability of the software were within the average range, unlike its learnability that was below the average range. The only scale above average was that related to attribute affect. The researcher concluded that more emphasis is needed on the design of this CAT tool to adapt to the real needs of the translators.

In the context of Arab translators, Alanazi [13] conducted a study to examine translator perceptions of CAT tools and explore the challenges that can hinder the use of these tools. The researcher used an online survey and conducted an observational experiment with 49 translators. Results revealed a strong inclination by Arab translators to encourage and support the use of CAT tools despite the challenges. These challenges included segmentation, punctuation, and spelling. The researcher suggested that there was no relationship between the challenges experienced during the use of CAT tools and the expressed level of satisfaction.

To our knowledge, the usability of CAT tools among Arab translators has not yet been systematically investigated in that we have no statistically documented empirical evidence of this significant parameter. Thus, in this study we investigate the usability of extensively used CAT tools from the translator’s perspective based on the SUMI survey (see Supplementary Materials). The evaluation involves the system’s efficiency, affect, usefulness, control, and learnability attributes. The study’s findings aim at drawing the attention of CAT tool designers and developers to the real needs of translators to enhance their user experience and improve the levels of satisfaction.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, a description of the methodology of the study is presented including data collection and participants.

3.1. SUMI

In this study, we examined the usability of CAT tools to identify the perceived quality of such tools among Arab translators. The English version of SUMI was used in this study since the common language pair among Arab translators is Arabic < > English (https://etranslationservices.com/blog/languages/top-five-language-pairs-for-business/). SUMI is an internationally standardized method commonly used for measuring the usability of software. It is a questionnaire comprising 50 items designed to measure five defined factors: efficiency, affect, helpfulness, control, and learnability. The questionnaire was first introduced in 1986 by Kirakowski [20], and it has been validated and used in various usability studies since then [20,21]. Many scholars believe that SUMI provides a valid and reliable measurement of users’ perception of a software usability and user satisfaction [5,9,22,23,24,25,26]. The instrument is also recognized by ISO/IEC 9126 as an accepted measurement for the assessment of the end-user’s experience. The SUMI survey involves the following scales:

Efficiency: refers to the translator’s feeling that the tool is enabling them to perform their task(s) in a quick, effective, and economical manner; alternatively, at the opposite extreme, whereby the software is affecting the translator’s performance.

- Affect: indicates that the translator feels mentally stimulated and pleasant, or the opposite, i.e., stressed and frustrated as a result of interacting with the tool.

- Helpfulness: refers to the translator perceptions that the software communicates in a helpful way and assists in the resolution of any technical problems.

- Control: refers to the translator’s feeling toward how the tools respond in an expected and consistent way to various inputs and commands.

- Learnability: refers to the feeling that the translator has on becoming familiar with the software, and provides an indication that its tutorial interface, handbooks, etc., are readable and instructive. This also refers to re-learning how to use the software following a period during which it had not been used.

The survey also involves a global usability scale to assess the general feeling of satisfaction with the translator’s experience of the tool.

For each of the questionnaire’s 50 statements, the participants select one of three responses (“agree,” “undecided,” and “disagree”) to evaluate their attitudes toward the CAT tool (see Supplementary Materials). When the survey is completed, responses are scored and compared with a standardization database with a specialized program known as SUMISCO that is available in the SUMI evaluation package. The evaluation was based on a Chi-square test and its results. Given that the standardization database includes the ratings of acceptable software, a score in the range of 40–60 is comparable in terms of usability for most successful software products, while scoring below 40 indicates a below-average evaluation [20]. A copy of the survey is shown in Supplementary Materials.

3.2. Participants

According to Kirakowski [20], the minimum sample size required to participate in the evaluation with acceptable accuracy using SUMI ranged between 10–12 participants. In this study, 42 translators completed the survey. Their background information, including age, occupation, translation experience, and software skills and knowledge, is presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Participants’ background information.

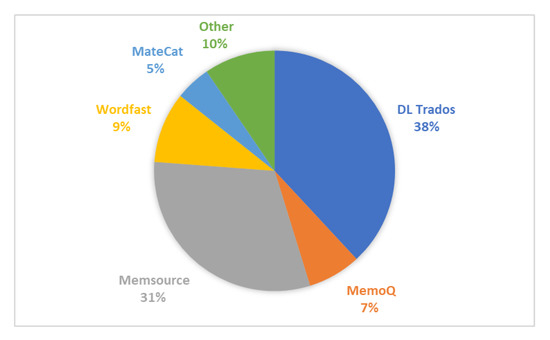

The participants were asked to specify the CAT tool they regularly used for their translation tasks. The survey showed that SDL Trados was the most popular CAT software among the participants followed by Memsource. MemoQ, Wordfast, mateCAT (mateCAT, Trento, Italy), and SmartCAT (SmartCAT Platform Inc, Boston, MA, USA), were also used by some translators, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools that are extensively used among participants.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis for SUMI

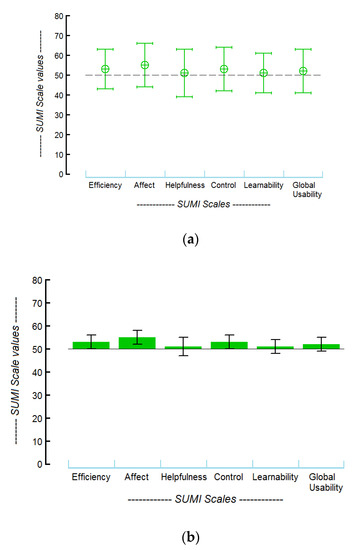

Table 2 below summarizes the results from the SUMI evaluation survey. The mean, standard deviation for the global usability scale, and each of the five usability subscales are presented. According to Kirakowski [21], the properties of the standard normal distribution indicate that over 68% of software will find a score on all the SUMI scales within one standard deviation of the mean, that is, between 40 and 60. Software that is above (or below) these points is already, by definition, well above (or below) average. When the value for a scale is above 50 (i.e., higher than the reference database), then the bar is shown in green. The average global score was 52.38, thus indicating that the usability of CAT tools is above the average and comparable to successful commercial systems. The mean values for all five subscales are also above average, wherein the higher scores were obtained for affect and efficiency, while the lowest scores were attributed to helpfulness and learnability. However, the difference is not significant, indicating generally consistent results that fall within the desired range. Figure 2a,b shows a comparison of quantitative usability measurements.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis for SUMI evaluation survey.

Figure 2.

(a) Means and Standard Deviation. (b) Means with 95% CIs.

4.2. Analysis of Strengths and Weaknesses

An itemized consensual analysis was conducted that calculated the value of Chi-square test for each of the 50 items and compared the distribution of the three response categories (agree, undecided, disagree) in the sample against the expected outcome from the standardization base.

The analysis showed that 21 items were worth considering as they yielded statistically significant results. Difference values of 0.50 or more, or −0.50 or less indicated major agreement (difference > +0.50) or major disagreement (difference < −0.50 negative). In contrast, difference values between 0.50 and −0.50 indicate a minor degree of agreement or disagreement. Analyzed results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Items indicating statistically significant results.

4.3. Analysis of Open-Ended Questions

The SUMI survey involved two questions on the best aspects of the CAT tools and on suggestions for improvement. Participant responses to the open-ended questions were analyzed with the Voyant Tools (Stéfan Sinclair & Geoffrey Rockwell, Montreal, QC, Canada) (https://voyant-tools.org/) that is an open-source, web-based system used for text analysis. It supports reading and interpretation of texts or corpus. Participants answers were entered in the system and the results are presented next.

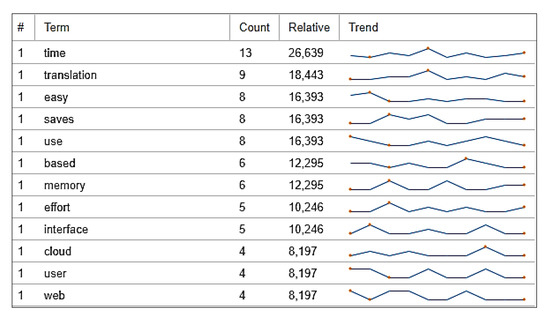

- What do you think is the best aspect of this software and why?

The responses to this question involved 488 total words and 228 unique word forms. The vocabulary density was 0.467 and the average number of words per sentence was 25.7. The analysis showed that the most frequent words in the corpus were time (13), translation (9), easy (8), saves (8), and use (8), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Most frequent words in participants’ responses on the best feature of CAT.

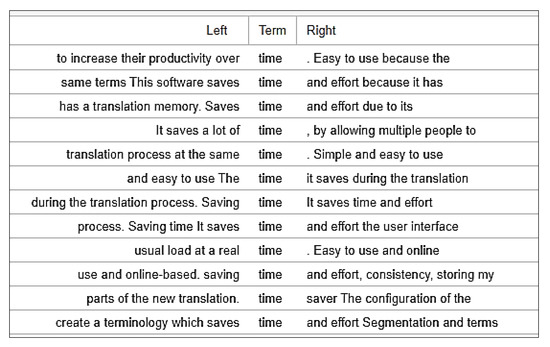

Phrase analysis showed that the most re-occurring phrases are “easy to use,” “saves time and effort,” “easy to use,” and “easy to learn.” A concordance analysis for the most frequent word is presented below in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Concordance results for the most frequent word in participants’ responses on the best feature of CAT.

- What do you think needs most improvement and why?

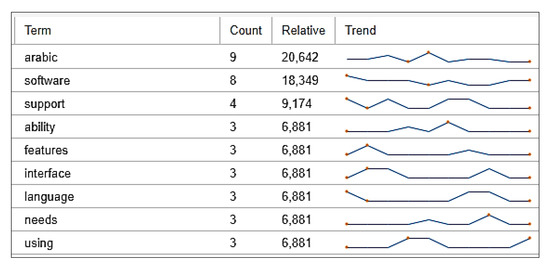

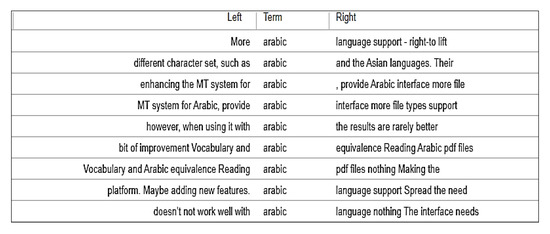

The responses to this question involved a corpus with 436 total words and 233 unique word forms. The vocabulary density is 0.534 and the average number of words per sentence is 25.6. The most frequent words in the corpus were the following: Arabic (9), software (8), support (4), ability (3), and features (3), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Most frequently used words in participants’ responses who suggested improvements for CAT.

Phrase analysis showed that the most reoccurring phrase was: “Arabic language support.” A concordance analysis for the most frequent word is shown below in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Concordance results for the most frequent word in suggested improvements to CAT.

5. Discussion

The SUMI analysis revealed that the average global score indicated that the usability of CAT tools is above average. All five subscales also scored above average. The higher scores were attributed to affect and efficiency, while the lowest scores were attributed to helpfulness and learnability. The itemized consensual analysis showed that a major agreement was obtained on three affect statements that included (a) reference of software recommendation to others, (b) enjoyment, and (c) satisfaction. This indicates the positive attitudes participants had toward CAT tools. Two helpfulness statements yielded major agreement responses among the participants. Both statements highlighted the effectiveness of the CAT tools. The efficiency of these tools received a major agreement response from users, i.e., on the statements describing the organization of the menus and the tool’s ease of use. Finally, a major agreement was also obtained on two control statements that described the tool’s navigation and speed. These results were also reflected in the comments provided by participants on the open-ended question regarding the best aspect of the software. Responses from participants highlighted how the software saved time and effort based on comments on the software’s ease of use and clarity. When asked to rate the importance of the software, 31% rated it as “Extremely Important” and 52% said it is “Important”. Such positive attitudes were reported in similar studies [5,13,17,18,27,28]. In Alanazi [13], the translators showed a high level of satisfaction toward the CAT tools despite the challenges they faced. Mahfouz [27] argues that positive attitudes towards CAT tools can be linked to the translator’s computer skills competence. With our participants, 45% were “experienced but not technical”, 38% “can cope with most software” while the rest 16% were “very experienced and technical” which might explain their positive attitudes towards the CAT tools.

Although results from the SUMI analysis yielded scores that were above average for all five subscales, i.e., >50, the lowest score was assigned to helpfulness and learnability. These two attributes were linked to the perceptions of the translators on how the system communicated in a helpful way and how it assisted in the resolution of any technical problems; on how familiar the translators were with the software; and on whether its tutorial interface, handbooks, etc., were readable and instructive. These findings were also confirmed by the participants’ comments on the improvement needed for these tools. One of the participants reported: “I would prefer to use software that is straightforward and without too many options and features that could confuse me while working,” and “The interface needs to be more user-friendly.”

These findings indicated that CAT tool developers needed to focus on the enhancement of the system’s helpfulness and learnability to improve the user’s experience and satisfaction levels. This was also suggested in other studies [5,13,27,29]. Moorkens and O’Brien [29] suggest that these tools can be improved by simplifying the interface and provide more features such as a variety of dictionaries and an internet search option.

On the same note, the participants’ suggestions for further improvement emphasized the need to enhance Arabic language support. The support needed includes Arabic character set, right-to-left text direction, OCR, and Machine Translation quality. As reported by some of the participants:

“Unfortunately, many documents I receive are PDFs or images. These require a software tool that can use its OCR features to recreate the text. The OCR is quite accurate when it is used on English texts, however, when using it with Arabic, the results are seldom better than 40%. This means that it is unreliable and thus cannot be used.”“Mostly the languages with different character set, such as Arabic and the Asian languages. Their character sets are still not processed well by most of the CAT software.”

According to Alanazi [13], despite the tremendous advances in the capabilities of CAT tools, there are several issues that have been left unsolved, even with the newest version, including segmentation, punctuation, Arabic script-related problems, and poor machine translation output. Thus, further improvements are still required to enhance the Arabic language support to attract more Arab translators.

6. Conclusions

Usability refers to the capability of a software product to be understood, learnt, and used, and is attractive to the user when used in specified conditions [14]. Despite the significance of usability studies in enhancing the user experience and satisfaction, research on the usability of CAT tools is rather limited, especially among Arab translators. In this study, we looked at the usability of extensively-used CAT tools from the translators’ perspective based on the SUMI survey. The evaluation involved the tool’s efficiency, affect, usefulness, control, and learnability attributes. The analysis revealed that the average global score was above average, which indicated a reasonable satisfaction rate. All five usability attributes were also above average, such that the highest scores obtained were attributed to affect and efficiency, while the lowest score was attributed to helpfulness and learnability. The findings suggest that CAT tool developers need to work more on the enhancement of the helpfulness and learnability attributes of the tools to improve the translator experiences and satisfaction levels. In addition, further improvements are still required to increase the Arabic language support to attract more Arab translators.

Although the sample size for this study (n = 42) is acceptable in most usability research, no attempts should be made to generalize the findings beyond the contexts of the study. Further work is still needed to examine the usability of CAT tools in various contexts and among different user groups. More evaluation studies should be conducted to independently investigate the usability of various features of CAT tools, e.g., the translation memory, the terminology management system, etc.

Other usability evaluation approaches can be employed to investigate further the usability of CAT tools among Arab translators.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/10/18/6295/s1, SUMI Survey, SUMI is an internationally standardized method commonly used for measuring the usability of software. It is a questionnaire comprising 50 items designed to measure five defined factors: efficiency, affect, helpfulness, control, and learnability.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by The Research Center for the Humanities, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University. The APC was funded by The Research Center for the Humanities, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bowker, L. Computer-Aided Translation Technology: A Practical Introduction; University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, J. The development and use of machine translation systems and computer-based translation tools. Int. J. Transl. 2003, 15. Available online: http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/WJHutchins (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Lagoudaki, P.M. Expanding the Possibilities of Translation Memory Systems: From the Translators Wishlist to the Developers Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2009. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10044/1/7879 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Krüger, R. Contextualising computer-assisted translation tools and modelling their usability. Trans.-Kom-J. Transl. Tech. Commun. Res. 2016, 9, 114–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sierra, C. Usability evaluation of a translation memory system. Quad. Filol. Estud. Lingüístics 2019, 24, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I. Computer-aided translation: Systems. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Technology; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, M. Translation management systems. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Technology; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 716–729. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, B. Arabic and computer-aided translation: An integrated approach. Transl. Comput. 2011, 33, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thawabteh, M. Apropos translator training aggro: A case study of the Centre for continuing education. J. Spec. Transl. 2009, 12, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, H.M. Arabic–English parallel corpus: A new resource for translation training and language teaching. Arab. World Engl. J. 2017, 8, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-jarf, P.R. Technology Integration in Translator Training in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Res. Eng. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Breikaa, Y. The Major Problems That Face English–Arabic Translators While Using CAT Tools. 2016. Available online: https://www.academia.edu (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Alanazi, M.S. The Use of Computer-Assisted Translation Tools for Arabic Translation: User Evaluation, Issues, and Improvements. Ph.D. Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA, 2019. Available online: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=kent1570489735521918 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- ISO IEC 9126-1:2001. Software Engineering-Product Quality Part 1-Quality Model; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. International Standard ISO/IEC 25022. In Systems and Software Engineering—Systems and Software Quality Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE)—Measurement of Quality in Use; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frøkjær, E.; Hertzum, M.; Hornbæk, K. Measuring usability: Are effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction really correlated? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1–6 April 2000; pp. 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, E.K. An Ethnographic Study of the Use of Translation Tools in a Translation Agency: Implications for Translation Tool Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/An-Ethnographic-Study-of-the-Use-of-Translation-inAsare/d72ddfa0d590921ec485121e4561988dd3d4cec7 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- LeBlanc, M. Translators on translation memory (TM). Results of an ethnographic study in three translation services and agencies. Transl. Interpret. 2013, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, M.; Pal, S.; Zampieri, M.; Naskar, S.K.; van Genabith, J. Improving CAT tools in the translation workflow: New approaches and evaluation. In Proceedings of the Machine Translation Summit XVII Volume 2: Translator, Project and User Tracks, Dublin, Ireland, 19–23 August 2019; pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kirakowski, J.; Corbett, M. SUMI—The software usability measurement inventory. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 1993, 24, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakowski, J. The Software Usability Measurement Inventory: Background and Usage. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P., Thomas, B., Weedmeester, E.B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Deraniyagala, R.; Amdur, R.J.; Boyer, A.L.; Kaylor, S. Usability study of the EduMod eLearning program for contouring nodal stations of the head and neck. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.S.; Hossan, M.I. Usability evaluation of a video conferencing system in a university’s classroom. In Proceedings of the 2016 19th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 18–20 December 2016; pp. 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weheba, G.; Attar, M.; Salha, M. A Usability Assessment of a Statistical Analysis Software Package. J. Manag. Eng. Integr. 2017, 10, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Alghanem, H. Assessing the usability of the Saudi Digital Library from the perspective of Saudi scholarship students. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Beijing China, 6–8 December 2019; pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, F.R.; Nabovati, E.; Bigham, R.; Khajouei, R. Usability evaluation of a comprehensive national health information system: Relationship of quality components to users’ characteristics. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 133, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfouz, I. Attitudes to CAT Tools: Application on Egyptian Translation Students and Professionals. AWEJ 2018, 4, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lek-Ciudin, I.; Vanallemeersch, T.; De Wachter, K. Contextual Inquiries at Translators’ Workplaces. In Proceedings of the TAO-CAT, Angers, France, 18–20 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moorkens, J.; O’Brien, S. User attitudes to the post-editing interface. In Proceedings of the Machine Translation Summit XIV: Second Workshop on PostEditing Technology and Practice, Nice, France, 2–6 September 2013; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).