Abstract

Institutions play a central role in shaping entrepreneurial behavior, yet much of the existing literature, even with the foundational insights of institutional economists such as Veblen, Mitchell, Commons, Coase, Ostrom, Williamson, and North, continues to view institutions as monolithic entities rather than as differentiated governance systems. This study addresses this gap by reconceptualizing institutions as multi-branch governance architectures in which legislative, executive, and judicial mechanisms interact to shape entrepreneurial outcomes, particularly in volatile emerging economies. The research asks how these disaggregated governance branches, mediated by institutional quality and external shocks, jointly influence entrepreneurial activity. Using Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) microdata for Iran over the period 2008–2020, merged with governance indicators and shock variables including sanctions and COVID-19, we employ pooled logistic regression to estimate the effects of governance functions and their policy mix interactions on Total Entrepreneurial Activity. The results show that executive policy quality has the strongest positive association with entrepreneurship, legislative coherence strengthens opportunity-driven activity, and judicial inefficiencies suppress entrepreneurial engagement by increasing uncertainty. Interaction effects further reveal that misalignment among governance branches weakens entrepreneurial activity, while coherent policy mixes mitigate the negative impact of external shocks. By integrating conceptual synthesis with empirical evidence, the study advances institutional theory, clarifies deficiencies in prevailing models, and demonstrates that entrepreneurial dynamism depends on the configuration and coordination of governance branches rather than on aggregate institutional scores. These insights provide policymakers with actionable guidance for designing coherent, adaptive, and resilient entrepreneurship-supporting ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Institutions play a foundational role in shaping economic behavior by structuring expectations, resolving transactional conflicts, and enabling coordination and trust within markets (Commons, 1950/1970). Their design and quality are particularly consequential for entrepreneurship, where institutional arrangements influence how opportunities are identified, created, and sustained over time. Building on the insights of institutional economics, a substantial body of research emphasizes that institutions affect entrepreneurial behavior primarily through their impact on transaction costs, incentives, and uncertainty (North, 1990; Hodgson, 1998; Williamson, 2010). Despite this rich literature, our understanding of how institutional governance mechanisms jointly shape entrepreneurial outcomes remains incomplete.

A key limitation of existing research lies in its treatment of institutions as largely monolithic constructs. Many empirical studies rely on aggregate indicators of institutional quality, economic freedom, or governance effectiveness, thereby obscuring the heterogeneity of institutional components and their distinct functions (Baumol, 1990; Sobel, 2008). In particular, the differentiated roles of legislative, executive, and judicial branches—and the ways in which these governance functions interact, coordinate, or conflict—are rarely examined explicitly. As a result, the internal dynamics of governance and the operation of policy mixes through which institutional strengths or weaknesses are translated into entrepreneurial outcomes remain underexplored, especially under conditions of political and economic volatility.

This study addresses this gap by advancing a multi-branch perspective on institutional governance and entrepreneurship. Rather than conceptualizing institutions as unified structures, the analysis disaggregates governance into legislative, executive, and judicial functions and examines how their interactions jointly shape entrepreneurial activity. By focusing on policy mixes and cross-branch complementarities, the study captures the mechanisms through which governance systems respond to external shocks and structural constraints. This approach departs from conventional institutional models by treating institutions as interacting rule-making and enforcement systems, whose combined configuration offers a more precise explanation of entrepreneurial dynamics in volatile and uncertain environments.

Guided by this perspective, the study examines how legislative, executive, and judicial governance branches—conditioned by institutional quality and external shocks—jointly influence entrepreneurial activity in emerging economies. Empirically, the analysis draws on firm-level data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, combined with macro-level governance indicators, to construct a unique dataset for Iran over the period 2008–2020. This context provides a particularly informative setting due to its evolving institutional architecture, recurrent external sanctions, and the systemic shock associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. By integrating micro-level entrepreneurial behavior with macro-level governance structures, the study contributes to institutional and entrepreneurship research by clarifying how governance configurations and policy mixes shape entrepreneurial responses to uncertainty. In doing so, it also offers policy-relevant insights for designing coherent and adaptive institutional frameworks aimed at strengthening entrepreneurial ecosystems in emerging economies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the theoretical framework and formulates the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data sources and outlines the empirical methodology. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 discusses the findings and highlights the theoretical, methodological, and empirical contributions of the study. Section 6 derives policy implications, with a particular emphasis on a policy mix perspective. Section 7 concludes the paper and finally, Section 8 outlines the main limitations of the study, along with directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Institutional Literature and Firm Activities

Drawing selectively on seminal contributions in institutional economics, including Veblen (1898), Commons (1924, 1934, 1936, 1950/1970), Coase (1937/1991), Williamson (1973, 1996, 2000, 2009, 2010), North (1990, 1991, 1997, 2005), V. Ostrom et al. (1961) and E. Ostrom (2005, 2009), this section develops a theoretical framework for deriving testable hypotheses on the causal relationship between institutional structures and firm activities. The framework analytically disaggregates institutions into their core elements and identifies the mechanisms through which their joint and systemic configuration affects economic performance and firm level outcomes. In particular, institutions are conceptualized as a system of differentiated yet interdependent governance branches, namely the legislative, executive, and judicial, whose coherence and functional alignment causally influence firm behavior by reducing transaction costs through effective rule making and enforcement. Accordingly, variation in the coordination and integrity of institutional components is expected to generate systematic differences in firm activities, thereby providing a clear foundation for hypothesis development.

Commons’s (1950/1970) concept of sovereignty distributed across government branches underpins the role of legislative, executive, and judicial functions in establishing collective rules that regulate behavior and reduce uncertainty. Coase (1937/1991) and Williamson (1996) emphasize transaction costs as fundamental constraints in both markets and governance, mitigated through institutional coordination. North (1990) extends this reasoning by focusing on imperfect contracts and the necessity of institutional trust. E. Ostrom’s (2005) concept of polycentric governance exemplifies adaptive institution design across varying layers of authority.

Building on these classical perspectives, this study engages deeply with the institutional logics’ literature, which documents the pluralistic coexistence and contestation of competing institutional logics shaping fields and organizations (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999, 2008; Thornton, 2002, 2004; Thornton et al., 2005; Friedland & Alford, 1991; Greenwood et al., 2010). This literature reveals how multiple logics simultaneously influence governance systems and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Complementing this, Bakir’s (2022) analytic eclecticism emphasizes the dynamic interactions among structure, institution, and agency, providing a rich lens to analyze entrepreneurial behavior under institutional complexity.

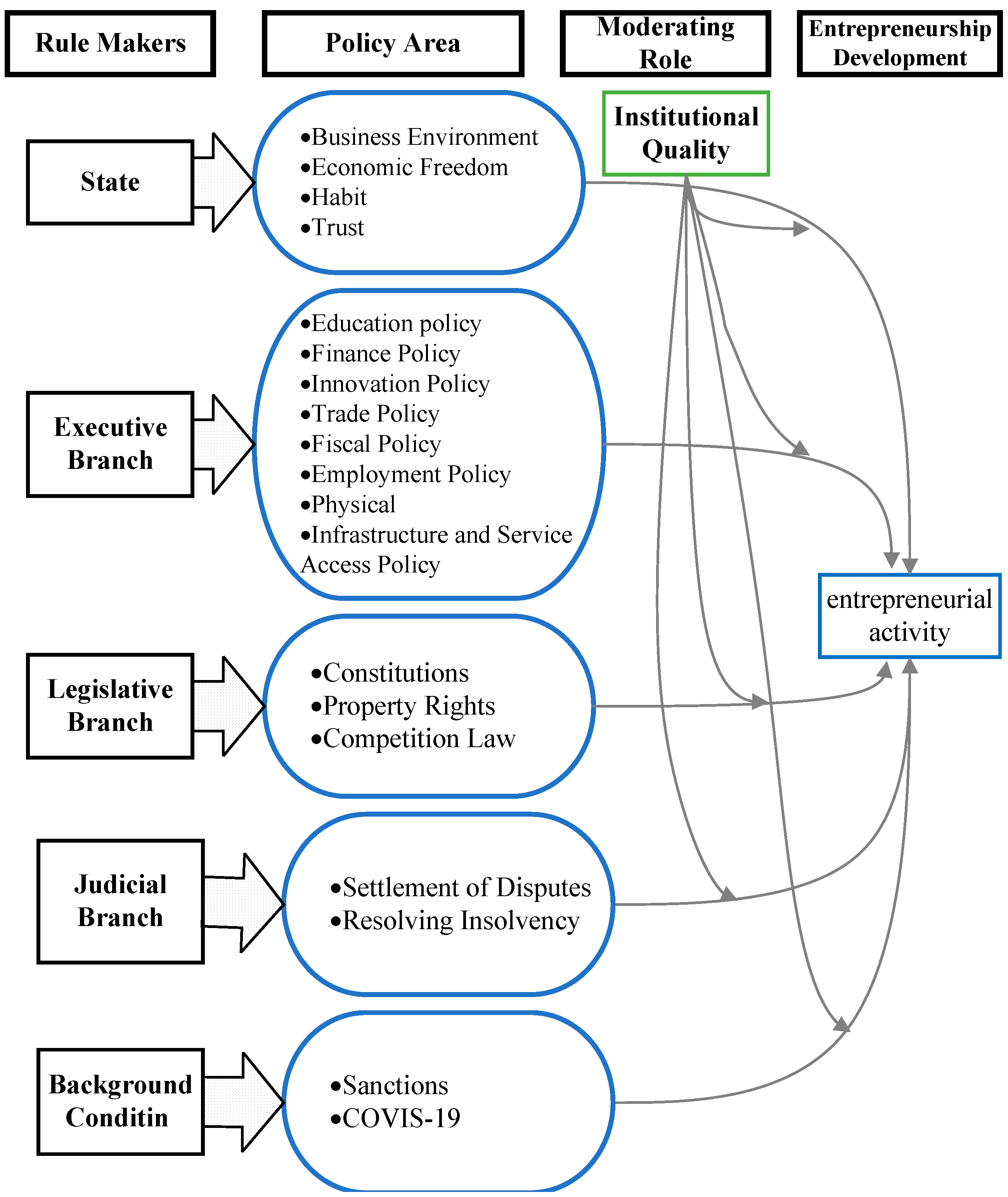

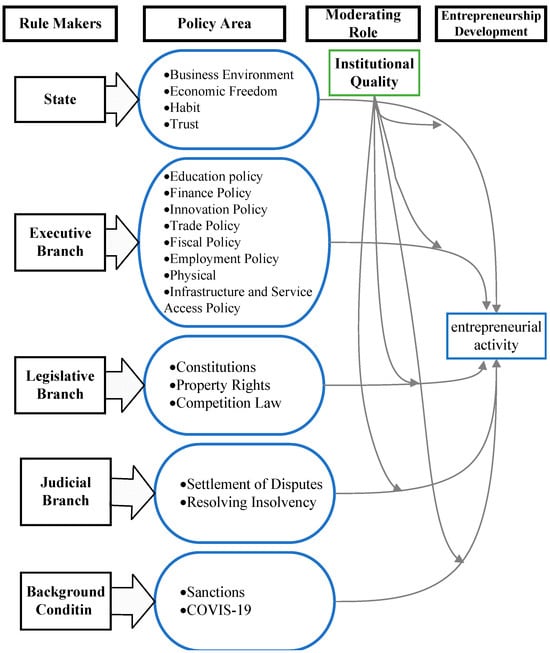

Table 1 motivates the shift from monolithic institutional views toward disaggregated analysis by identifying branch-specific mechanisms influencing entrepreneurship, complementing critiques of aggregate formal/informal dichotomies (Urbano et al., 2019). Figure 1 operationalizes this conceptual logic by detailing the interactive roles of governance branches in policy-making and enforcement, directly justifying Hypotheses 1 through 3: (a) coordinated branches reduce transaction costs promoting entrepreneurship (H1); (b) institutional quality moderates branch effects (H2); and (c) external shocks disrupt institutional coordination, affecting entrepreneurial outcomes negatively (H3).

Table 1.

Comparing research findings on institutions and entrepreneurship.

Figure 1.

Disaggregated institutional framework: Governance branches and entrepreneurship.

This framework emphasizes the state’s role via its three branches in shaping entrepreneurial environments, particularly through collective action, governance capacity, transaction cost reduction, and institutional trust. Institutional stickiness (Boettke et al., 2008) highlights the importance of historically and locally rooted institutions, which are more sustainable and effective than externally imposed ones, underscoring the necessity of adaptive governance and legal enforcement in entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Summing up, these perspectives establish a rigorous theoretical basis for disaggregating institutions and integrating pluralistic institutional logics with dynamic governance interactions to comprehensively understand their influence on firm activities and entrepreneurial performance.

2.2. Institutions and Entrepreneurial Activities

This subsection bridges institutional theory to entrepreneurship outcomes, supporting Hypothesis 1 by demonstrating how governance branch coordination shapes Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) through complementary policy mechanisms (Figure 1, center panel). Institutions define “rules of the game” enabling opportunity discovery and venture creation (Baumol, 1990; North, 1990).

Literature reveals critical gaps motivating disaggregation (Table 1): Urbano et al.’s (2019) 25-year review shows 70% of studies use North’s (1990, 2005) aggregate framework, categorizing formal institutions (political structures, property rights), informal norms (social beliefs), and regulatory dimensions-but overlooking branch-specific interactions. Su et al. (2017) identify red tape barriers (state size, corruption control, deregulation, tax/bankruptcy rules) yet analyze them monolithically. Moreover, Audretsch et al. (2022) find that property rights are central for emergent entrepreneurship, while interactions between corruption, government size, and formal institutions further moderate these effects. Audretsch (2023) notes that research on institutions and entrepreneurship has shifted from focusing on individual traits to emphasizing the role of institutions, policy, and culture, reflecting the growing recognition of the contextual and institutional determinants of entrepreneurial activity.

Institutional quality plays a critical role in shaping entrepreneurial ecosystems, as higher-quality institutions can reduce uncertainty, support resource access, and foster more sustainable entrepreneurship. While entrepreneurship education and ecosystem actors contribute to enterprise creation, sustainability-oriented practices can further leverage institutional voids, enhancing entrepreneurial outcomes and promoting the development of stronger long-term regional institutions (Webb et al., 2020; Stam, 2015, 2017; Audretsch et al., 2022, Audretsch et al., 2024).

Policies lower entry barriers, enhance resource mobility, and integrate markets (Campbell, 1992; Kirchhoff, 1993; Hindle, 2010; Thurik et al., 2013). Property rights, rule of law, and antitrust regulation foster productive entrepreneurship (Bhat & Khan, 2014; Boettke & Coyne, 2009, 2015), while institutional environments enable novel forms (Hwang & Powell, 2005). Entrepreneurs respond to quality/enforcement under uncertainty via creative destruction (Schumpeter, 1934), discovery (Kirzner, 1973), and risk-taking (Rothbard, 1985; Boettke, 2018). Inclusive institutions channel efforts productively; extractive ones stifle innovation (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012; Acemoglu et al., 2005; Z. J. Acs et al., 2018).

Drawing on Commons’ (1950/1970) concept of sovereignty across governance branches (Figure 1, left panel), coordinated legislative rules, executive implementation, and judicial enforcement are expected to reduce transaction costs and uncertainty. This policy coherence enables complementary functioning of institutional branches, enhancing market confidence and access to resources, and thereby predicting a positive effect on Total Early-stage Entrepreneurship Activity (TEA).

2.3. Highlighting Theoretical Research Gap

Table 1 synthesizes 25 years of institutional-entrepreneurship research (Urbano et al., 2019) against this study’s contributions, revealing a persistent gap: prior work treats institutions as monolithic or aggregate structures, overlooking their disaggregated, dynamic interactions via state branches. Our framework, rooted in Veblen, Commons, Coase, Williamson, North, and Ostrom, reconceptualizes institutions as rule-making systems comprising legislative (constitutions, property rights, competition law), executive (education, finance, innovation, trade, fiscal, employment, infrastructure policies), and judicial (dispute resolution, insolvency) functions whose interplay drives governance and entrepreneurial outcomes.

This disaggregation addresses limitations in dominant models by emphasizing policy instruments over static rules and extending beyond formal/informal dichotomies to capture branch-specific metrics for policy design. While institutional logics literature documents pluralistic coexistence and contestation of multiple logics shaping organizational fields (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999, 2008; Thornton, 2002, 2004; Thornton et al., 2005; Friedland & Alford, 1991; Greenwood et al., 2010), and analytic eclecticism highlights structure-agency-institution dynamics (Bakir, 2022), empirical applications to entrepreneurship remain field-level rather than governance-operationalized.

Our novelty bridges this gap by empirically testing branch interactions with policy mixes and shocks (e.g., sanctions, COVID-19), integrating logics’ multiplicity with agential responses in emerging economies like Iran. This approach offers granular, adaptive insights absent in aggregate analyses (Urbano et al., 2019; Su et al., 2017), linking transaction costs, trust, and institutional evolution to directly motivate hypotheses on institutional, quality, and contextual effects.

2.4. Hypotheses Development

H1 Justification: Institutional economics demonstrates institutions shape entrepreneurship by reducing uncertainty via transaction costs, regulatory barriers, financing access, and property rights security (Baumol, 1990; Coase, 1937/1991, 1960; Williamson, 1996, 2000; Thurik et al., 2013; Urbano et al., 2019). Commons’ (1950/1970) sovereignty across governance branches (Figure 1, left panel) advances this by disaggregating into rule-makers: executive (regulatory efficiency, tax incentives, education/finance/innovation/trade policies), legislative (property rights, competition laws, dispute mechanisms; Z. J. Acs et al., 2018), judicial (contract enforcement, due process; Commons, 1936; Williamson, 1991, 2009). Coordinated branches form transparent ecosystems lowering entry barriers (Campbell, 1992; Kirchhoff, 1993; Table 1), predicting positive TEA via “rules of the game” coherence (Boettke & Coyne, 2009, 2015; Su et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 1.

A business-oriented executive branch, supportive legislative framework, and efficient judiciary-jointly operating within coherent state-level institutional order-reduce transaction costs, enhance economic freedom, improve access to finance/antitrust protections/secure property rights, and positively influence entrepreneurial activity.

H2 Justification: Institutional quality moderates branch efficacy (Figure 1, center panel). Strong rule of law/regulatory efficiency amplifies governance effects (North, 1990; Sobel, 2008), while corruption distorts allocation/reduces trust (Tonoyan et al., 2010; Rothstein, 2011; Chowdhury et al., 2019), and uncertainty pushes informal networks (Knight, 1921; Coase, 1937/1991; North, 2005; Puffer et al., 2010; Webb et al., 2020; Deerfield & Elert, 2023). Higher quality strengthens formal institutions via reduced costs/trust (Su et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 2.

Institutional quality-including corruption control and uncertainty-moderates governance effects on entrepreneurship. Higher quality strengthens positive branch impacts by reducing transaction costs, increasing institutional trust, and lowering decision-making uncertainty.

H3 Justification: External shocks disrupt governance coordination (Figure 1, right panel), exacerbating uncertainty in Iran’s rentier economy undergoing structural transitions (low growth, unemployment, inflation, oil dependence; demand-side policies over human capital/innovation). Sanctions (US since 1979; Majidi & Zarouni, 2016; Afshar Jahanshahi & Brem, 2020) and COVID-19 disrupt supply chains/production/job losses, amplifying policy volatility, banking inflation constraints, and state-affiliated favoritism over private startups—pushing low-risk ventures despite resilience via indigenous knowledge, knowledge-based enterprises, VC/angel/grants, and digital economy potential (Davari & Najmabadi, 2018; Table 1 contextual factors).

Hypothesis 3.

External shocks (sanctions, COVID-19) negatively moderate institutional effects on entrepreneurial activity in Iran by exacerbating policy volatility, limited finance access, rent-seeking structures, and intellectual property/contract enforcement gaps—increasing uncertainty, transaction costs, and constraining innovation despite educated workforce resilience.

2.5. Conceptualizing the Institutional Environment

Building on foundational works by institutional economists—Veblen, Mitchell, Coase, Commons, Ostrom, Williamson, and North—this study presents a nuanced framework that departs from traditional monolithic conceptions of institutions. We disaggregate institutions into key rule-makers, emphasizing the distinct but interconnected roles of governance branches, laws, regulations, and policies in shaping entrepreneurial behavior. Commons highlights sovereign power in governance, Ostrom underscores the significance of adaptive public policy, and Williamson’s transaction cost economics explains how governance structures influence economic decision-making. Integrating these perspectives enables a comprehensive understanding of institutional factors driving business dynamics. Importantly, the framework incorporates external shocks, including economic sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing a detailed analysis of their impacts on entrepreneurial activity. As depicted in Figure 1, this framework underpins the empirical analysis by linking institutional rule-makers, contextual factors, and economic outcomes into a coherent model.

Furthermore, this paper offers actionable policy recommendations designed to foster a supportive institutional environment for entrepreneurship. It identifies critical mechanisms such as credit access, a favorable business climate, and effective antitrust legislation as fundamental to reducing transaction costs and promoting fair competition. Our findings stress the importance of targeted interventions to stabilize markets and minimize uncertainties facing new ventures. The study also advocates institutional reforms facilitated through collaborative governance among government agencies, civil society, and the private sector, aiming to strengthen entrepreneurial ecosystems. These policy insights are broadly applicable, offering guidance for both developed and emerging economies.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Methodological Foundations

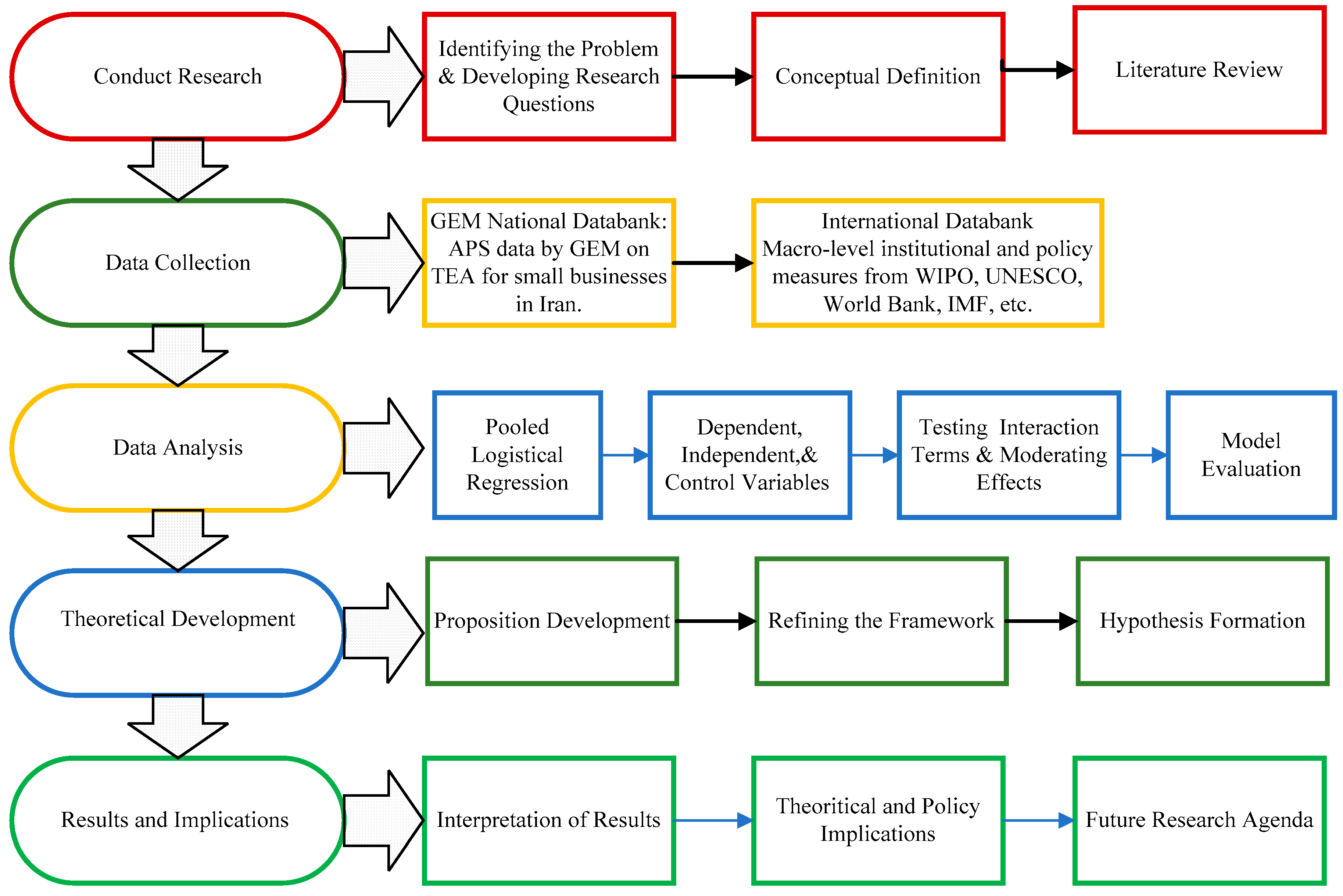

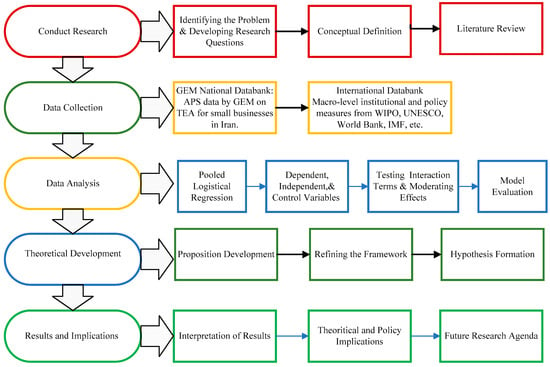

The research process, illustrated in Figure 2, begins with problem identification through a literature review, leading to research questions and concept definition. Theoretical development involved refining the framework, forming propositions, and developing hypotheses. Data collection included firm-level and macro-level institutional measures, analyzed using pooled logistic regression to test key variables, interaction terms, and moderating effects. Final model evaluation informed theoretical and policy implications, guiding the development of a future research agenda based on identified gaps.

Figure 2.

Research Methodological foundations.

This study employs a repeated cross-sectional observational research design using individual-level Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS) data merged with macro-level institutional and policy indicators. Given the non-experimental nature of the data, the analysis does not aim to establish causal effects but rather to identify patterned relationships and conditional associations across institutional dimensions. Accordingly, the estimated coefficients should be interpreted as indicative of structural alignment or misalignment within the governance environment, rather than as causal parameters reflecting policy interventions. This distinction is particularly important in contexts characterized by institutional volatility, where governance indicators may co-evolve with entrepreneurial activity.

Repeated cross-sectional designs are widely used in entrepreneurship and institutional research when panel data are unavailable or inappropriate due to survey structure, sample rotation, and respondent anonymity, as is the case with GEM APS data. This design allows researchers to identify patterned associations and institutional configurations across time without imposing assumptions of unit-level temporal continuity. In contexts characterized by institutional volatility, repeated cross-sections provide a suitable empirical strategy for examining how governance environments and entrepreneurial behavior co-evolve at the population level.

The inclusion of multiple interaction terms reflects the exploratory objective of the study, as interaction effects are central to the analysis because the theoretical contribution lies in identifying institutional alignment and misalignment rather than estimating isolated marginal effects. Rather than testing a single parsimonious causal mechanism, the modeling strategy is designed to surface how combinations of governance conditions jointly shape entrepreneurial outcomes. This approach is consistent with institutional and configuration-based perspectives, which emphasize that institutional effects are rarely isolated and often contingent on complementary or conflicting arrangements. As such, the results are interpreted as exploratory patterns that inform theory development, not as confirmatory estimates of isolated institutional effects.

Methodological Scope and Limits

The methodological scope of this study is explicitly non-causal. Given the observational and repeated cross-sectional nature of the data, the analysis does not seek to identify causal effects or policy treatment impacts. Instead, the purpose is to uncover configurational patterns and conditional associations among governance mechanisms, institutional quality, and entrepreneurial activity. Potential endogeneity, reverse causality, and omitted variable bias cannot be fully ruled out and are therefore acknowledged as limitations rather than addressed through causal identification strategies. These limitations are consistent with the study’s theory-building orientation and point to promising avenues for future research using longitudinal, quasi-experimental, or mixed-method designs.

3.2. Data

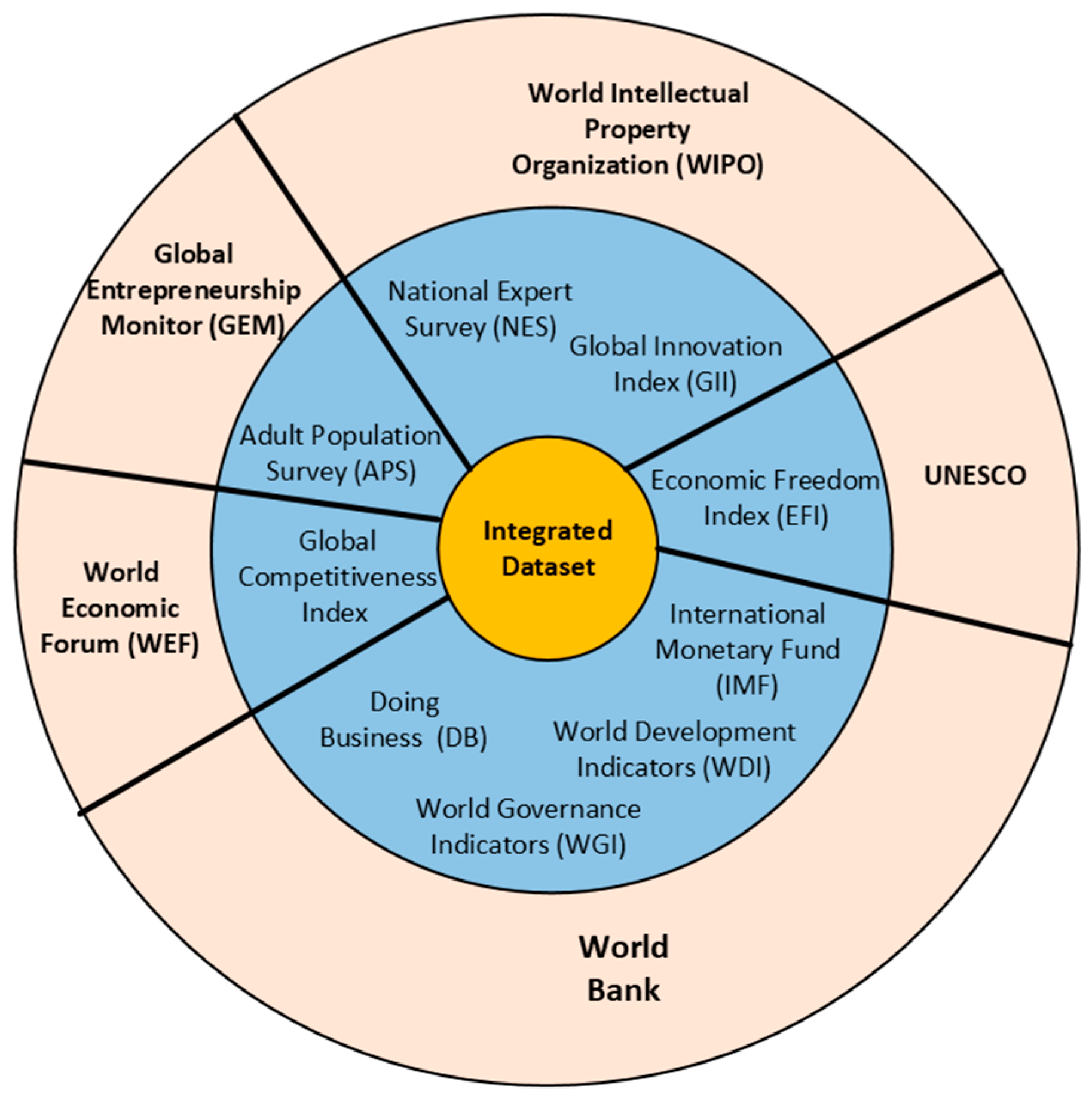

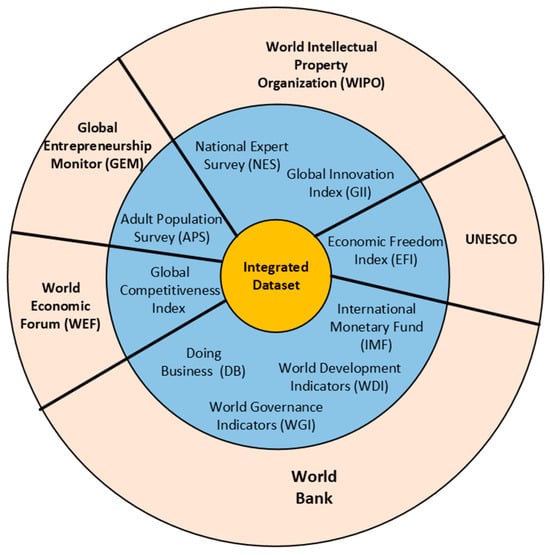

We construct the database using the Adult Population Survey (APS), an annual dataset from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). The data covers small businesses in Iran from 2008 to 2020. GEM’s key variable, total entrepreneurial activity (TEA), is a binary measure indicating whether an individual is engaged in starting or managing a business within the past 3.5 years. See Figure 3 for details.

Figure 3.

Integrated data sources.

Building on prior research examining national-level nascent entrepreneurial activity, this study used Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) as the dependent variable (Z. A. Acs et al., 2017; Bosma et al., 2018; Stel et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2005). Since GEM collects cross-sectional, not panel, data, autoregressive models were unsuitable. Propositions and framework adjustments preceded hypothesis formation. A pooled logistic regression framework analyzed the effects of policy and institutional factors on TEA, acknowledging that panel data techniques provide deeper insights into country-level dynamics. Diagnostic tests supported the pooled regression model, revealing minimal unit- or time-specific effects and confirming its suitability for identifying broad trends in entrepreneurial activity. Table 2 provides variable definitions.

Table 2.

Definition of variables and sources.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical findings aligned with the paper’s conceptual framework and institutional theory foundation. Results are reported thematically, corresponding to different governance functions and policy domains, rather than hierarchically by coefficient magnitude. Coefficient signs and statistical significance are interpreted in terms of directional associations and interaction tendencies, reflecting institutional alignment or misalignment across governance mechanisms. Given the conceptual proximity among several governance indicators and the likelihood of correlated institutional dynamics, the analysis emphasizes configurational patterns across models rather than isolated marginal effects (see Table 3). Accordingly, the findings highlight how particular institutional constellations are associated with higher or lower levels of entrepreneurial activity, without ranking governance mechanisms by strength or causal importance. All results are based on logit regression models reported in Table 4a,b and Table 5a,b.

Table 3.

The correlation matrix of variables.

Table 4.

Logit regression results, standard errors in parentheses, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Table 5.

Logit regression results with interactions, standard errors in parentheses, * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

4.1. Business Regulation and Market Institutions

This set of results primarily reflects legislative branch rule-setting and executive regulatory capacity, particularly in relation to competition policy, market access, and business regulation. Business environment and competition policies emerge as key drivers of Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA). As shown in Table 4a, anti-trust legislation positively affects TEA (Model 6: β = 0.079, p < 0.05), suggesting that competition fosters opportunity-based entrepreneurship. Business environment scores are similarly positive (Model 5: β = 0.011, p < 0.05), underscoring the value of regulatory stability.

These findings support Hypothesis 1, indicating that structured formal institutions reduce transaction costs and enhance trust. Conversely, tariff duties show a negative effect (Model 8: β = −0.111, p < 0.01), aligning with Transaction Cost Economics (TCE), where protectionism raises entry costs and limits market efficiency.

A transparent regulatory landscape encourages entrepreneurship, while trade barriers deter new ventures.

4.2. Financial Access and Legal Infrastructure

This subsection captures the combined influence of executive financial policy implementation and judicial enforcement capacity, particularly through access to finance and legal predictability mechanisms. Access to banking services and legal predictability significantly impact entrepreneurship. As shown in Table 4b, higher values of the banking services indicator—reflecting more restrictive or less accessible banking conditions—are associated with lower levels of TEA (β = −0.182, p < 0.01). But its interaction with control of corruption (CC × Banking Services) is negative (β = −0.027, p < 0.01), indicating that, under conditions of stronger corruption control, procedural and compliance requirements may further constrain effective access to finance.

Resolving insolvency positively influences TEA (β = 0.287, p < 0.01), suggesting that predictable legal outcomes reduce entrepreneurial risk.

These results reinforce Hypothesis 1, illustrating how efficient judiciary and finance access enhance entrepreneurship.

4.3. Innovation and Knowledge Economy Policies

The results in this subsection primarily reflect executive branch innovation and knowledge policies, conditioned by institutional quality and governance integrity. Innovation variables show context-dependent effects on TEA. In Table 5b, employment in knowledge-intensive services negatively affects TEA (β = −2.113, p < 0.01) but becomes positive when moderated by CC (β = 0.080, p < 0.01). Similarly, R&D transference is negative (β = −2.977, p < 0.01) but turns positive with CC interaction (β = 0.109, p < 0.01).

These outcomes support Hypothesis 2, confirming that institutional quality amplifies the positive effects of innovation policies on entrepreneurship.

Innovation boosts entrepreneurship only when governance is transparent and accountable.

4.4. Trade, Fiscal, and Education Policy

This set of findings reflects interactions between legislative trade and fiscal frameworks and executive policy implementation, particularly in education and economic governance capacity. Trade openness and education investment show conditional effects. Trade freedom is negatively related to TEA (β = −0.026, p < 0.01) but becomes positive with CC moderation (β = 0.057, p < 0.01). Government spending on non-tertiary education initially shows a negative effect (β = −6.990, p < 0.05) but turns positive when interacted with CC (β = 1.021, p < 0.01).

Fiscal variables like economic governance capacity (EGC) also exhibit interaction effects.

These results support Hypotheses 1 and 2, emphasizing that institutional quality determines whether trade and education policies support entrepreneurship.

4.5. The Moderating Role of Institutional Quality

Across the preceding analyses, control of corruption (CC) consistently emerges as a moderating condition shaping how governance and policy mechanisms translate into entrepreneurial outcomes. In Table 5a,b, its effects include:

- CC × Business Environment: Negative interaction, indicating that overregulation may limit flexibility.

- CC × Knowledge Employment: Positive interaction, enabling innovation spillovers.

- CC × Tariffs: Positive moderation, showing how clean governance offsets trade frictions.

These results affirm Hypothesis 2: good governance reduces uncertainty and enhances the effectiveness of entrepreneurship policy. Rather than restating individual effects, these interaction patterns are interpreted as evidence of institutional alignment or misalignment across governance domains.

4.6. Impact of the External Shocks

External disruptions significantly impact TEA. Sanctions and COVID-19 have negative effects (Sanctions: β = −0.342, p < 0.01; COVID-19: β = −0.179, p < 0.05). These shocks magnify internal vulnerabilities like policy instability and limited financing.

These results support Hypothesis 3, showing how external constraints exacerbate internal structural barriers to entrepreneurship.

4.7. Summary of Findings

These findings validate the proposed conceptual framework. Policy effectiveness is contingent on institutional strength, and reforms must balance oversight with efficiency to support entrepreneurial ecosystems in environments like Iran.

- Entrepreneurship is fostered by fair competition, legal predictability, and accessible finance.

- Innovation and education policies succeed in transparent institutional environments.

- Overregulation under anti-corruption initiatives can slow business activity.

- External shocks reduce TEA, especially where institutional resilience is weak.

5. Discussion and Contributions

Taken together, the findings support a configuration-based interpretation of entrepreneurial governance, in which entrepreneurial outcomes depend on the alignment and coherence among legislative, executive, and judicial functions rather than on isolated institutional strengths. Across the empirical analyses, governance mechanisms appear most effective when they operate as complementary components of a broader institutional configuration, while partial or uneven reforms are associated with weaker or inconsistent entrepreneurial responses.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurship and institutional economics by advancing a pattern-based interpretation of how governance and policy environments shape entrepreneurial activity in constrained contexts. Drawing on the foundational insights of institutional economists—including Veblen (1898), Commons (1924, 1934), Coase (1937/1991), Williamson (1996, 2000), E. Ostrom (2005, 2009), and North (1990, 2005)—the paper conceptualizes entrepreneurship as an outcome of interacting institutional arrangements rather than isolated regulatory or policy instruments. By integrating these theoretical traditions, the study develops an institutional framework that emphasizes systemic coherence, institutional complementarity, and alignment across governance domains.

Empirically, the study combines firm-level entrepreneurial data with macro-level institutional and policy indicators, merging sources such as GEM, WGI, WEF, GII, WIPO, IMF, and national datasets. This multi-layered approach allows for the examination of how formal governance structures, innovation policies, and financial conditions jointly shape entrepreneurial outcomes. The use of logit regression models is intended to identify directional associations and interaction tendencies rather than to rank institutional mechanisms by magnitude, which is consistent with prior cross-national institutional research where pseudo-R2 values tend to be modest due to high contextual heterogeneity.

Importantly, the analysis does not treat governance indicators as independent levers but as elements of a broader institutional configuration. This approach responds to critiques in the literature that overly reductionist models fail to capture the complexity of entrepreneurship in environments characterized by regulatory instability, uneven reform trajectories, and external constraints such as sanctions or macroeconomic shocks.

5.2. Interpreting Institutional Alignment and Misalignment

The empirical findings suggest that entrepreneurial outcomes in constrained environments are shaped less by the presence of individual governance mechanisms than by their alignment and coherence across institutional domains. In contexts such as Iran, where legal, regulatory, and political institutions evolve unevenly, improvements in one governance dimension may fail to stimulate entrepreneurship if complementary institutions lag behind. For example, innovation-supporting policies may generate limited impact when legislative instability, weak enforcement, or financial frictions undermine predictability and increase uncertainty for potential entrepreneurs.

Several associations that appear weak, insignificant, or even negative when viewed in isolation become more intelligible when interpreted through an institutional misalignment lens. Such patterns do not indicate institutional failure; rather, they signal partial reforms, sequencing problems, or coordination gaps across governance domains that can generate compliance costs, uncertainty, or transitional frictions. This interpretation aligns with institutional theory, which emphasizes that reforms implemented without systemic coordination can produce transitional frictions rather than immediate entrepreneurial gains.

Consistent with institutional and governance theories, entrepreneurship emerges not as a linear response to individual policy interventions but as a function of institutional constellations. The findings therefore highlight the importance of sequencing, complementarity, and coherence in governance reform. Entrepreneurial activity is more likely to flourish when regulatory clarity, financial access, innovation incentives, and enforcement credibility evolve in tandem, rather than through isolated or symbolic policy changes.

6. Policy Impacts and Policy Mix

6.1. Policy Impacts

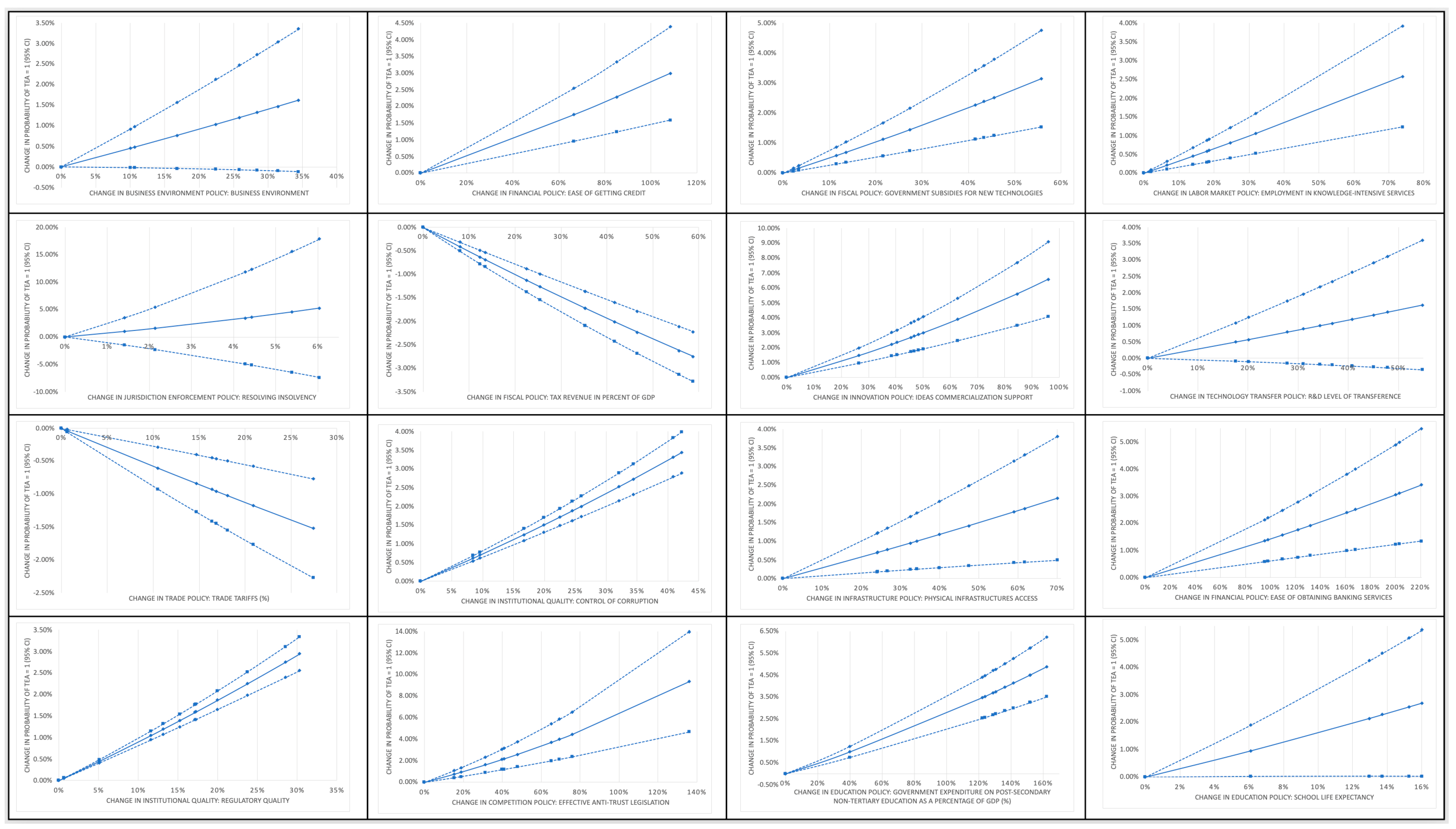

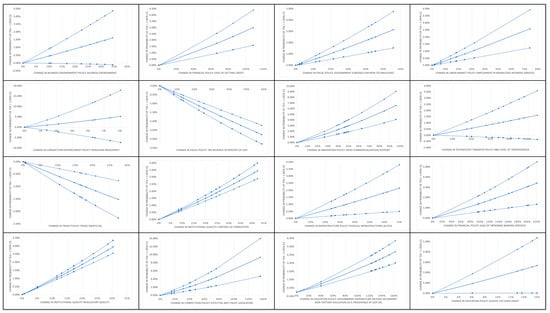

We analyze the impact of policy changes. To interpret the coefficients, we calculated the impact of a percentage increase in a policy measure on the probability of TEA = 1 in the logistic regression. The results for all policy and institutional measures, with a 95% confidence interval, are displayed in Figure 4. For instance, a 5% increase in jurisdiction and enforcement capacity, as proxied by resolving insolvency indicators, is associated with an estimated increase of approximately 15% in the probability of TEA = 1. However, a 20% increase in Innovation policy, as measured by support for idea commercialization, would result in only a 1% increase in the probability of TEA = 1. The analysis highlights the varying impacts of policy measures and institutional variables on entrepreneurial activity (TEA = 1), with corruption control (CC) playing a significant moderating role. Improved access to good banking services is associated with lower financial barriers and higher levels of entrepreneurial activity, but stringent CC can introduce procedural inefficiencies, diminishing this effect. Streamlined financial governance is essential to balance oversight with accessibility. Similarly, the interaction between government expenditure on post-secondary non-tertiary education (% of GDP) and CC shows that while high spending on education may initially appear inefficient, effective CC ensures transparency and better resource allocation, aligning educational investments with entrepreneurial needs.

Figure 4.

The impact of changes in policy and institutional measures in the probability of Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA).

Taken together, these results indicate that policy and institutional effects on entrepreneurship are conditional rather than additive. Improvements in individual policy domains—such as financial access, education spending, or infrastructure—do not uniformly translate into higher entrepreneurial activity unless they are embedded within supportive governance conditions. In this context, corruption control operates less as an independent driver and more as a conditioning mechanism that shapes whether policy interventions reduce uncertainty or introduce additional procedural frictions. The findings therefore do not imply a universal policy recipe but rather underscore the importance of context-sensitive policy mixes tailored to institutional capacity and external constraints.

This study reveals that CC plays a dual role in influencing entrepreneurship. For knowledge-intensive services, CC promotes knowledge spillovers, mitigating the negative effects of stable, high-paying jobs on entrepreneurship. While limited R&D commercialization can hinder entrepreneurial activity, strong CC helps overcome barriers and fosters trust, facilitating innovation into ventures. Additionally, physical infrastructure and service access support entrepreneurship by reducing costs and enhancing connectivity, although stringent CC may slightly hinder these benefits by causing delays in governance processes. The findings emphasize the need for governance frameworks that balance strong oversight with operational efficiency to optimize entrepreneurial outcomes.

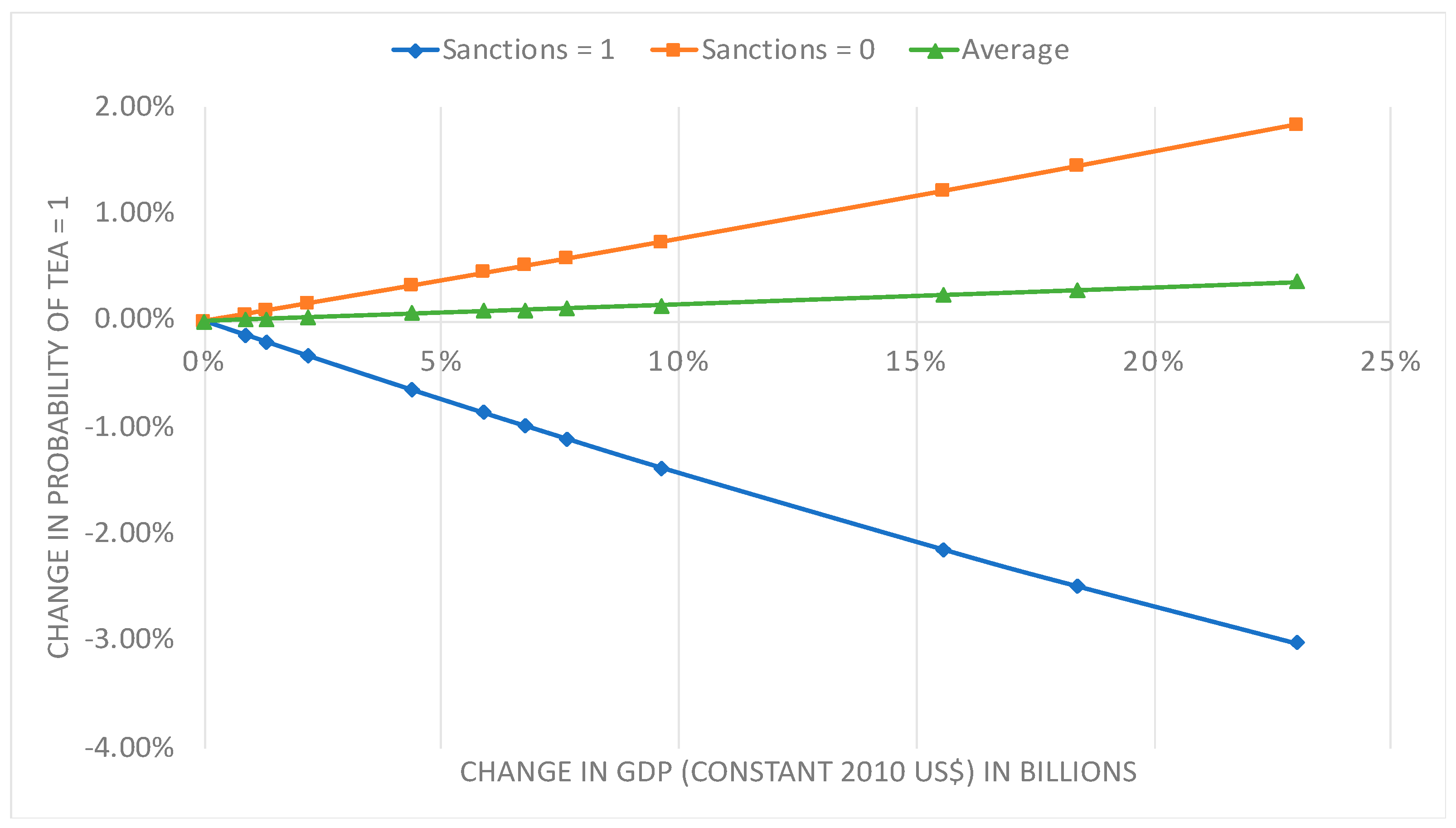

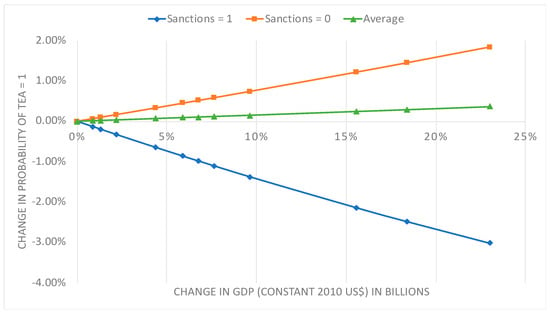

The figure illustrates the nonlinear interaction between GDP growth and sanctions on entrepreneurial activity (TEA = 1). A 10% increase in GDP results in an average 0.15% rise in total entrepreneurial activity (Figure 5). However, in the absence of severe sanctions (Severe sanctions = 0), this effect increases to a 0.75% rise in TEA, highlighting the positive impact of economic growth in a sanctions-free environment. Conversely, under severe sanctions (Severe sanctions = 1), the same GDP increase leads to a 1.4% decline in entrepreneurial activity, underscoring the disruptive effects of sanctions on the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Figure 5.

The impact of changes in GDP interacted with Sanctions (2018–2020) in the probability of Total.

These results indicate that macroeconomic growth alone is insufficient to stimulate entrepreneurship under conditions of severe institutional constraint. While GDP growth is positively associated with entrepreneurial activity in the absence of sanctions, the reversal of this effect under severe sanctions highlights how external shocks can neutralize or even invert the benefits of economic expansion. Sanctions appear to amplify uncertainty, disrupt financial channels, and weaken policy transmission mechanisms, thereby limiting the capacity of growth to translate into entrepreneurial opportunity. This finding underscores the importance of institutional and geopolitical context when interpreting standard growth–entrepreneurship relationships.

6.2. Integrated Framework for Policy Mix

A well-structured policy mix is essential for fostering entrepreneurship, as it addresses business challenges by integrating policy areas, behavioral dimensions, and institutional mechanisms. This article demonstrates how the policy mix framework shapes entrepreneurship policies by focusing on two interrelated components: the strategic component, which defines overarching goals, and the instrument mix, which combines specific policy tools. The effectiveness of a policy mix depends on its consistency, coherence, credibility, and comprehensiveness, as well as its ability to balance stringency, predictability, and flexibility in implementation (Rogge & Reichardt, 2016; Mavrot et al., 2019). From a governance perspective, these policy domains map onto distinct but interdependent functions of legislative rule-setting, executive policy implementation, and judicial enforcement, reinforcing the importance of cross-branch alignment in policy design.

The findings highlight the central role of regulatory frameworks and governance reforms in promoting entrepreneurial activity. Regulatory change typically emerges from complex political processes involving multiple stakeholders, including political leaders and interest groups (Jabotinsky & Cohen, 2020). By integrating institutional laws, regulatory reforms, and policy packages, policymakers can simultaneously enhance economic and trade freedom, improve access to finance, and strengthen anti-corruption mechanisms. A successful policy mix must therefore remain adaptable to emerging challenges-particularly those associated with technological development and financial markets-while maintaining institutional stability. The results underscore the need to balance such stability with entrepreneurial flexibility to support sustainable entrepreneurship.

Within this integrated framework, several policy domains play complementary roles. Economic and trade freedom reduce market restrictions and ensure open access to domestic and international markets, thereby creating a predictable environment for entrepreneurial entry and expansion. Regulatory efficiency-achieved through streamlined business registration, simplified tax systems, and effective insolvency regulations-lowers barriers for new firms and reduces uncertainty. Financial access and development, including improved banking efficiency and deeper financial markets, facilitate capital access and support entrepreneurial risk-taking. Innovation support policies, such as strengthened intellectual property protection and securities regulations, enable the funding and commercialization of new ideas. Finally, transparency and trust, reinforced through legal protections and anti-corruption measures, underpin confidence in the business environment and sustain long-term investment.

To foster entrepreneurship, the findings suggest the importance of aligning strategic objectives with well-coordinated policy instruments, creating a coherent, consistent, and credible environment for business creation and growth. By simultaneously addressing economic freedom, trade access, financial development, innovation support, and legal protections, such a policy mix can reduce entry barriers, stimulate innovation, and promote a competitive and sustainable economy. A comprehensive yet flexible approach is particularly important for Iran, where coordinated institutional reforms are necessary to build a dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem capable of supporting long-term economic growth.

7. Conclusions

This study set out to advance the understanding of entrepreneurial governance by examining how institutional structures and policy mixes shape entrepreneurial activity under conditions of heightened uncertainty. Drawing on foundational insights from institutional economics, particularly the contributions of Veblen, Commons, Coase, Williamson, Ostrom, and North, the article developed a multi branch conceptual framework that treats institutions not as monolithic entities but as interacting governance mechanisms. By disaggregating institutions into legislative, executive, and judicial functions, the study offers a configuration-oriented perspective in which entrepreneurship emerges from the alignment and coherence of institutional arrangements rather than from isolated policy instruments.

Empirically, the analysis demonstrates that entrepreneurial outcomes in constrained environments are shaped less by the presence of individual governance mechanisms than by their interaction, sequencing, and consistency across institutional domains. Institutional quality remains central, but its effects are mediated by the degree of coordination among governance branches and by the broader policy environment. External shocks such as international sanctions and the COVID 19 pandemic further condition these relationships by amplifying uncertainty and exposing institutional misalignments. In contexts such as Iran, fragmented or uneven governance responses tend to weaken entrepreneurial incentives, whereas coherent institutional configurations can partially offset adverse shocks and sustain entrepreneurial engagement.

The study makes several contributions to the literature. Theoretically, it advances a pattern-based interpretation of entrepreneurial governance that emphasizes institutional complementarity, systemic coherence, and alignment across governance domains. This approach extends existing institutional theories by showing how partial or uncoordinated reforms may generate transitional frictions rather than immediate entrepreneurial gains. Methodologically, the study combines firm level entrepreneurial data with macro level institutional, innovation, and financial indicators drawn from multiple international sources. By focusing on interaction tendencies and institutional configurations rather than ranking individual mechanisms by magnitude, the analysis responds to longstanding critiques of reductionist institutional models in heterogeneous and volatile contexts. Empirically, the findings validate the proposed framework and demonstrate that weak or negative associations should be interpreted as signals of institutional misalignment rather than evidence against the relevance of governance mechanisms.

From a policy perspective, the results underscore that improving entrepreneurial ecosystems in emerging economies requires more than incremental or symbolic reforms. Effective policy design depends on coherent policy mixes that align legislative stability, executive implementation capacity, judicial credibility, financial access, and innovation support. Entrepreneurship is more likely to flourish when reforms are sequenced and coordinated across institutional domains, thereby reducing uncertainty and compliance burdens for potential entrepreneurs. Governance systems that evolve unevenly risk undermining the intended effects of otherwise well-designed policies.

Summing up, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of entrepreneurship as a governance dependent and configuration driven process. By highlighting the role of institutional alignment, policy mixes, and systemic coherence, it offers both theoretical refinement and practical guidance for scholars and policymakers seeking to foster resilient and adaptive entrepreneurial ecosystems in emerging economies.

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurial governance by illustrating how institutional configurations, policy environments, and external shocks jointly shape entrepreneurial activity in constrained contexts. Grounded in institutional theory and empirically examined within the Iranian setting, the findings offer context-sensitive insights rather than universal prescriptions. At the same time, limitations should be acknowledged, which also point to important avenues for future research.

First, the observational and cross-sectional research design limits the ability to capture dynamic feedback effects between governance institutions and entrepreneurial activity over time. Institutional change and entrepreneurial responses are inherently evolutionary processes, and longitudinal data would allow future studies to examine how reforms unfold and how entrepreneurs adapt under shifting policy regimes.

Second, the reliance on observational data constrains causal inference, as endogeneity and reverse causality cannot be fully ruled out. While this study adopts a pattern-based, non-causal analytical approach, future research could employ quasi-experimental designs or exploit policy shocks—such as sanctions, regulatory reforms, or exogenous institutional changes—to strengthen causal interpretation.

Third, the single-country focus on Iran—characterized by sanctions, policy volatility, and structural constraints—may limit the generalizability of the findings to more stable institutional environments. Comparative studies across emerging economies with varying governance capacities would help clarify the boundary conditions of the institutional configurations identified here.

Finally, the study relies on available institutional indicators and policy proxies, which may not fully capture how entrepreneurs experience and interpret governance conditions in practice. Qualitative or mixed-method approaches, including interviews or field-based studies, could enrich understanding of how entrepreneurs navigate institutional uncertainty at the micro level.

Future research could build on this study by leveraging longitudinal GEM data, where available, to examine institutional change over time, or by combining repeated cross-sectional evidence with quasi-experimental approaches that exploit policy reforms or external shocks. Cross-country comparative analyses of governance configurations would further clarify how institutional alignment operates across different political and economic contexts. In addition, qualitative follow-up studies with entrepreneurs could provide deeper insight into how governance coherence and misalignment are perceived and acted upon at the firm level. These extensions would allow future research to further unpack the dynamic evolution of governance–entrepreneurship linkages identified in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M. and M.J.; methodology, M.A.M. and M.J.; software, M.A.M. and M.J.; validation, M.A.M. and M.J.; formal analysis, M.A.M. and M.J.; investigation, M.A.M. and M.J.; resources, M.A.M. and M.J.; data curation, M.A.M. and M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.M. and M.J.; writing—review and editing, M.A.M. and M.J.; visualization, M.A.M. and M.J.; supervision, M.A.M. and M.J.; project administration, M.A.M. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, 385–472. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty. Profile Book. [Google Scholar]

- Acs, Z. A., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z. J., Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Szerb, L. (2018). Entrepreneurship, institutional economics, and economic growth: An ecosystem perspective. Small Business Economics, 51, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A., & Brem, A. (2020). Entrepreneurs in post-sanctions Iran: Innovation or imitation under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty? Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(2), 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B. (2023). Institutions and entrepreneurship. Eurasian Business Review, 13(3), 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Desai, S. (2022). The role of institutions in latent and emergent entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Eichler, G. M., & Schwarz, E. (2024). Entrepreneurial ecosystems, institutional quality, and the unexpected role of the sustainability orientation of entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 62(2), 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, C. (2022). Why do comparative public policy and political economy scholars need an analytic eclectic view of structure, institution and agency? Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 24(5), 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S., & Khan, R. (2014). Entrepreneurship and institutional environment: Perspectives from the review of literature. European Journal of Business and Management, 6(1), 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Boettke, P. J. (2018). FA Hayek: Economics, political economy and social philosophy. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Boettke, P. J., & Coyne, C. J. (2009). Context matters: Institutions and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 135–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P. J., & Coyne, C. J. (2015). Entrepreneurship and development: Cause or consequence? In Austrian economics and entrepreneurial studies (pp. 67–87). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2008). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(2), 331358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N., Sanders, M., & Stam, E. (2018). Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. C. (1992). A decision theory model for entrepreneurial acts. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2019). Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. H. (1991). The nature of the firm. In The nature of the firm: Origins, evolution, and development (pp. 18, 33). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1937). [Google Scholar]

- Commons, J. R. (1924). Legal foundations of capitalism. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Commons, J. R. (1934). Institutional economics. Vol. I: Its place in political economy (Vol. 1). Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Commons, J. R. (1936). Institutional economics. The American Economic Review, 1(26), 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Commons, J. R. (1970). The economics of collective actions. University of Wisconsin Press. (Original work published 1950). [Google Scholar]

- Davari, A., & Najmabadi, A. D. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystem and performance in Iran. In Entrepreneurship ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) dynamics in trends, policy and business environment (pp. 265–282). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Deerfield, A., & Elert, N. (2023). Entrepreneurship and regulatory voids: The case of ridesharing. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(5), 1568–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. A. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell, & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, R., Díaz, A. M., Li, S. X., & Lorente, J. C. (2010). The multiplicity of institutional logics and the heterogeneity of organizational responses. Organization Science, 21(2), 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindle, K. (2010). How community context affects entrepreneurial process: A diagnostic framework. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(7–8), 599–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G. M. (1998). The approach of institutional economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(1), 166–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H., & Powell, W. W. (2005). Institutions and entrepreneurship. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 201–232). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jabotinsky, H. Y., & Cohen, N. (2020). Regulatory policy entrepreneurship and reforms: A comparison of competition and financial regulation. Journal of Public Policy, 40(4), 628–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, B. (1993). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capitalism. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit (Vol. 31). Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, A. F., & Zarouni, Z. (2016). The impact of sanctions on the economy of Iran. International Journal of Resistive Economics, 4(1), 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrot, C., Hadorn, S., & Sager, F. (2019). Mapping the mix: Linking instruments, settings and target groups in the study of policy mixes. Research Policy, 48(10), 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1997). Some fundamental puzzles in economic history/development. In W. B. Arthur, S. N. Durlauf, & D. A. Lane (Eds.), The economy as an evolving complex system II. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. C. (2005). Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing the sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325(5939), 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, V., Tiebout, C. M., & Warren, R. L. (1961). The organization of government in metropolitan areas: A theoretical inquiry. American Political Science Review, 55, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S. M., McCarthy, D. J., & Boisot, M. (2010). Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The impact of formal institutional voids. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, K. S., & Reichardt, K. (2016). Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: An extended concept and framework for analysis. Research Policy, 45(8), 1620–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, M. N. (1985). Professor Hébert on entrepreneurship. Journal of Libertarian Studies, 7(2), 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, R. S. (2008). Testing Baumol: Institutional quality and the productivity of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. (2017). Measuring entrepreneurial ecosystems. In Entrepreneurial ecosystems: Place-based transformations and transitions (pp. 173–197). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Stel, A. V., Carree, M., & Thurik, R. (2005). The effect of entrepreneurial activity on national economic growth. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J., Zhai, Q., & Karlsson, T. (2017). Beyond red tape and fools: Institutional theory in entrepreneurship research, 1992–2014. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(4), 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P. H. (2002). The rise of the corporation in a craft industry: Conflict and conformity in institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P. H. (2004). Markets from culture: Institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P. H., Jones, C., & Kury, K. (2005). Institutional logics and institutional change in organizations: Transformation in accounting, architecture, and publishing. In Transformation in cultural industries (pp. 125–170). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (1999). Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990. American journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–128). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Thurik, A. R., Stam, E., & Audretsch, D. B. (2013). The rise of the entrepreneurial economy and the future of dynamic capitalism. Technovation, 33(8–9), 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonoyan, V., Strohmeyer, R., Habib, M., & Perlitz, M. (2010). Corruption and entrepreneurship: How formal and informal institutions shape small firm behavior in transition and mature market economies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D., Aparicio, S., & Audretsch, D. (2019). Twenty-five years of research on institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What has been learned? Small Business Economics, 53, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T. (1898). Why is economics not an evolutionary science? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 12(4), 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J. W., Khoury, T. A., & Hitt, M. A. (2020). The influence of formal and informal institutional voids on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(3), 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (1973). Markets and hierarchies: Some elementary considerations. The American Economic Review, 63(2), 316–325. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (1996). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (2009). Informal institutions rule institutional arrangements and economic performance. Public Choice, 139, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (2010). Transaction cost economics: The natural progression. American Economic Review, 100(3), 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Autio, E. (2005). Entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth: Evidence from GEM data. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.