Abstract

Sustainable innovation is important in Albania, a small transition economy facing pressures from digitalization, the green transition, and increased competition. Yet the country’s innovation system is still developing, and academia–business linkages remain weak. This article investigates how academia–business (A2B) collaboration contributes to firms’ sustainable innovation, addressing the lack of quantitative evidence from a country in the Western Balkans context. Building on innovation systems and resource-based perspectives, A2B cooperation is conceptualized as a multidimensional latent construct, capturing types of collaboration, key actors, and organizational drivers. Using survey data from 298 firms operating in Albania, collected in 2025, the study applies Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) to test whether the intensity and quality of A2B cooperation are linked to sustainable innovation outcomes. The findings indicate that collaboration is still limited and inconsistent, dominated by student internships and sporadic joint projects. However, the CB-SEM results confirm that more intensive and better-structured cooperation is strongly associated with higher levels of sustainable innovation. The study offers one of the first CB-SEM-based quantitative assessments of A2B collaboration and sustainable innovation in Albania and provides policy implications for strengthening innovation-oriented partnerships in transition economies.

1. Introduction

As economies face environmental pressures, rising societal expectations, and intensifying global competition, sustainable innovation has become a major concern for businesses and governments (Hermundsdottir & Aspelund, 2021). Sustainable innovation refers to the development of products, services, and processes that simultaneously improve economic performance, reduce environmental pressures, and create positive social outcomes (Bos-Brouwers, 2010; de Almeida Couto & Natário, 2023). In practice, this makes sustainable innovation more than a compliance issue. Many firms increasingly treat it as a way to remain competitive and build resilience during rapid technological change and wider sustainability transition (Aragón-Correa & Sharma, 2003; Hart & Dowell, 2011).

A growing body of research also highlights the role of academia–business collaboration in supporting innovation and sustainable development (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015; Jirapong et al., 2021; Rossoni et al., 2024; Xia et al., 2025). For firms, working with universities can open access to specialized knowledge, research infrastructure, and skilled human capital. For universities, these partnerships create opportunities to apply research in practical settings and engage with real industrial challenges (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015; Di Maria et al., 2019; Jirapong et al., 2021). While the intensity and form of cooperation vary, from internships to joint research and development (R&D), these relationships are generally assumed to strengthen firms’ innovation capacity and support sustainable development goals (Di Maria et al., 2019; Jirapong et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2025).

Yet collaboration is far from uniform across contexts. Evidence suggests that academia–business linkages are often weak in transition and emerging innovation systems (Landoni & Muradzada, 2024; Yang et al., 2025). The barriers most often discussed include limited institutional support, insufficient intermediary structures, low levels of R&D investment, and lack of trust between universities and enterprises (Albats et al., 2022; Alexandre et al., 2022; Çabiri & Qosja, 2023; Rossoni et al., 2024). These problems tend to be more intense in small and open economies where firms operate under strong competition pressure and must respond quickly to digitalization and increasing sustainability requirements. At the same time, empirical evidence on how A2B cooperation relates specifically to sustainable innovation outcomes in such contexts remains limited. In addition, collaboration is often measured in very broad ways, which makes it harder to understand how specific collaboration forms, actor relationships, and enabling conditions together shape innovation performance, especially in transition contexts.

This study examines whether A2B cooperation is associated with firms’ sustainable innovation performance in Albania. Albania provides a relevant setting: innovation capacity is still developing, and collaboration between universities and firms remains uneven. Two research questions guide the analysis: (i) Which firm-level drivers explain the collaboration between academia and business in Albania, particularly in relation to sustainable innovation? (ii) To what extent does A2B collaboration influence innovation outcomes, with a focus on sustainable innovation?

To address these questions, the study uses survey data collected in 2025 from 298 firms operating in Albania and applies CB-SEM. Collaboration and sustainable innovation are modeled as latent constructs, allowing the analysis to capture their multidimensional nature and test their overall association.

The article contributes in three ways. First, it provides one of the few quantitative analyses of A2B collaboration and sustainable innovation in Albania. Second, by modeling collaboration and innovation as latent constructs and testing their relationship through SEM, it offers a clearer view of how different dimensions of A2B interaction jointly shape firms’ innovation performance. Third, it derives policy implications for universities, firms, and public authorities seeking to design more effective instruments to foster sustainable innovation through A2B partnerships.

The article is organized as follows. The next section reviews the theoretical and empirical literature on academia–business cooperation and sustainable innovation and provides the contextual background of the study setting. The methodology section then presents the dataset, measurement model, and CB-SEM procedures. The final sections report on the findings, discuss their implications, and conclude.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Collaboration between academia and business is widely recognized as a key mechanism within national and regional innovation systems (Sjöö & Hellström, 2019; Varblane et al., 2008). Within innovation systems and Triple Helix frameworks, innovation is not only generated within companies but emerges through the interaction, institutional linkages, and knowledge exchanges among universities, firms, governments, and intermediaries (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000; Sjöö & Hellström, 2019). This is particularly relevant for emerging and transition economies, where companies’ internal R&D capacity is often limited and universities can provide access to scientific expertise, research infrastructure, and highly skilled human capital (Belitski et al., 2019; Varblane et al., 2008). Under pressures related to digitalization (Evans et al., 2023), sustainability demands, and competitive pressures (Samoilikova et al., 2023), collaboration becomes necessary as it can enhance innovation capacity and partially compensate for limited R&D investments (Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006).

From a firm-centered perspective, A2B collaboration can be understood as a capability-building mechanism. Building on the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities literature, firms increasingly rely on external knowledge and complementary resources that cannot be generated internally, and they must build capabilities that enable adaptation to environmental and technological change (Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006; Laursen & Salter, 2006; Teece, 2007). Collaboration with universities can support learning, strengthen absorptive capacity, and enhance firms’ ability to develop innovation outcomes. However, collaboration generates innovation benefits only when firms can recognize, assimilate, and apply external knowledge, when they possess absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Zahra and George (2002) distinguish between potential absorptive capacity (acquisition/assimilation) and realized absorptive capacity (transformation/exploitation), explaining why cooperation does not automatically translate into innovation. University–industry interaction can nurture these absorptive-capacity dimensions and strengthen firms’ ability to convert academic knowledge into innovation (Bishop et al., 2011). This argument is consistent with evidence showing that firms’ exploratory innovation capabilities are strengthened through involvement in Triple Helix collaboration networks (Ryan et al., 2018). Building on this, the present study models A2B cooperation as a strategic mechanism through which firms develop capabilities that translate into improved innovation performance, with particular attention to sustainability-oriented outcomes.

A2B collaboration is not a single activity but a multidimensional and evolving process (Alpaydın & Fitjar, 2024; Sjöö & Hellström, 2019; Yang et al., 2025). It involves multiple types of interaction (e.g., internships, joint research projects, technology transfer, shared laboratories) and engagement with diverse actors (firms, universities, research centers, investors, policymakers), and it is shaped by various organizational and institutional drivers (strategic orientation, funding, governance, trust) (Evans et al., 2023; Schofield, 2013; Yang et al., 2025). Importantly, collaboration types differ in depth and content of knowledge exchange, leading to differentiated innovation outcomes (Fitjar & Gjelsvik, 2018). Nevertheless, the literature still often operationalizes A2B cooperation broadly, offering limited clarity about which collaboration dimensions matter most for sustainable innovation and through what mechanisms. To address this gap, the present study conceptualizes cooperation as a multidimensional construct reflected in three sub-dimensions: types of cooperation (TCAB), actors of cooperation (ACAB), and cooperation drivers and mechanisms (CMAB).

These dimensions correspond to complementary theoretical mechanisms. First, TCAB captures the channels through which firms access knowledge and expertise consistent with the knowledge-based view and open innovation, where innovation depends on breadth and depth of knowledge sourcing (Laursen & Salter, 2006; Perkmann et al., 2013). Second, ACAB reflects the ecosystem and Triple Helix logic that collaboration outcomes depend on network diversity and the involvement of actors who enable coordination, financing, diffusion and commercialization (Alexandre et al., 2022; Albats et al., 2022; Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000). Third, CMAB captures the relational and governance mechanisms that reduce transaction costs and enable sustained cooperation, including innovation culture, trust, transparency, intellectual property (IP) management, incubators, and training programs (Bruneel et al., 2010; Muscio & Vallanti, 2014; Rossoni et al., 2024). In contexts characterized by weaker institutional support structures, such mechanisms may be particularly important, since trust-building, governance arrangements and intermediary support often compensate for gaps in funding and policy coordination (Ćudić et al., 2022; Kleiner-Schaefer & Schaefer, 2022).

Empirical research supports that collaboration with universities can strengthen firms’ innovation performance, including sustainable innovation outcomes (Arroyave et al., 2020; Jing, 2024; Nie et al., 2022). Universities provide research-based solutions such as resource-efficient approaches, circular economy models, and green technologies, while firms contribute market knowledge and implementation capacity (Adams et al., 2015; Bu et al., 2025; Klewitz & Hansen, 2014). At the same time, collaboration benefits are not automatic: barriers related to differences in goals and time horizons, IP concerns, bureaucracy, and administrative procedures often constrain the intensity and effectiveness of cooperation (Bruneel et al., 2010). Evidence shows that enabling conditions such as trust, prior collaboration experience, supportive governance, and resource availability shape whether cooperation becomes sustained and innovation-relevant (Alexandre et al., 2022; Albats et al., 2022; Muscio & Vallanti, 2014; Rossoni et al., 2024). This supports incorporating collaboration drivers and mechanisms as a central component of cooperation rather than as secondary contextual factors.

Finally, collaboration outcomes are influenced by the broader innovation-system environment. Comparative evidence from the European Union and Western Balkan countries indicates that stronger investments in knowledge development, networking, and R&D inputs are associated with higher A2B collaboration performance (Ćudić et al., 2022). Western Balkan economies, including Albania, tend to score low on these institutional and linkage conditions, reflecting weaker support environments for structured cooperation (Cvetanović et al., 2015; Despotovic et al., 2014; Kostoska & Hristoski, 2017). This implies that the effectiveness of A2B collaboration depends not only on firms’ internal capabilities but also on the presence of policy support, funding instruments and intermediary mechanisms that strengthen the innovation linkages (Ćudić et al., 2022). Against this background, the present study investigates how different dimensions of A2B cooperation shape sustainable innovation performance in the Albanian context.

2.2. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

The structural model explains how A2B cooperation is structured and how it affects firms’ innovation performance. Cooperation is considered a multidimensional capability-building process reflected in three connected dimensions: types of cooperation (TCAB), actors involved (ACAB), and drivers and mechanisms (CMAB). Together, these dimensions represent the main channels, network structures, and enabling conditions through which firms and universities develop stable and effective collaboration. Once collaboration is established, it is expected to positively influence innovation by expanding access to scientific knowledge, supporting learning and absorptive capacity, and strengthening innovation-related capabilities.

In the measurement model, innovation is specified as a construct reflecting sustainable innovation in a context-sensitive way. It is operationalized through two complementary dimensions: Characteristics of sustainable innovation (CSI), capturing positive sustainability-oriented outcomes (e.g., resource efficiency, environmental responsibility, economic and social impact), and challenges of sustainable innovation at home (CSIH), capturing barriers faced during implementation (e.g., infrastructure and financing gaps, regulatory complexity, weak entrepreneurship culture). Together, CSI and CSIH represent both innovation outcomes and the conditions under which sustainable innovation is pursued, consistent with sustainability innovation literature (Adams et al., 2015; Bu et al., 2025; Klewitz & Hansen, 2014). Building on this framework, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

- i.

- Hypotheses on building academia–business collaboration (H1–H3)

H1.

Types of A2B collaboration (TCAB) have a positive and statistically significant impact on building collaboration.

Building on the view that cooperation operates through multiple interaction channels, TCAB captures the breadth of engagement that firms and universities establish (Laursen & Salter, 2006; Perkmann et al., 2013). Prior research shows that no single collaboration form satisfies all motivations or knowledge needs; instead partners combine channels such as joint research, consultancy, student engagement, and technology transfer (D’Este & Patel, 2007). Empirically, involvement across multiple agreement types is associated with greater continuity and stronger relational foundations, including trust and coordination (Muscio & Vallanti, 2014). Therefore, broader use of TCAB is expected to strengthen the development of collaboration.

H2.

Engagement of A2B collaboration actors (ACAB) has a positive and statistically significant impact on building collaboration.

ACAB reflects the extent to which collaboration is supported by a sufficiently diverse set of participants and complementary roles. Within the Triple Helix, collaboration becomes stronger when university, industry, and government actors actively contribute to project formation and institutional arrangements (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000). Ecosystem and network studies similarly suggest that intermediaries, investors, and public agencies enhance collaboration by enabling coordination, resource mobilization, and commercialization pathways (Alexandre et al., 2022; Albats et al., 2022). Role clarity and the presence of “integration” actors can reduce fragmentation and strengthen collaborative processes (Gattringer et al., 2014). Hence, greater involvement of relevant actors is expected to increase the likelihood that collaboration forms and becomes institutionalized.

H3.

Drivers and mechanisms of the A2B collaboration model (CMAB) have a positive and statistically significant impact on building collaboration.

CMAB represents the governance and relational infrastructure that supports stable collaboration. Evidence distinguishes barriers linked to partners‘ orientations (differences in goals and time horizons) and transaction barriers (e.g., IP concerns and bureaucratic procedures), showing that collaboration is more likely to persist when trust, coordination routines and prior experience reduce uncertainty and friction (Bruneel et al., 2010). Institutional support mechanisms (including incentives and networking structures) also raise the probability that collaboration develops into a sustained arrangement rather than an isolated interaction (Muscio & Vallanti, 2014). More recent studies emphasize formal and informal mechanisms (e.g., innovation culture, IP arrangements, incubators, and support structures) as enabling conditions for embedding collaboration and making it innovation-relevant (Rossoni et al., 2024; Muscio & Vallanti, 2014). Accordingly, stronger drivers and mechanisms are expected to positively influence the building of collaboration.

- ii.

- Hypothesis on the impact of collaboration on innovation (H4)

H4.

Collaboration between academia and business has a positive and statistically significant impact on innovation.

Collaboration is expected to enhance innovation performance by improving firms’ access to research capabilities and problem-solving resources that may not be available internally (Brimble & Doner, 2007). Empirical evidence suggests collaboration supports innovation through technology acquisition, skills and human capital development, and the translation of research into firm-level applications (Lee et al., 2010). From a dynamic capabilities perspective, external knowledge and resources strengthen firms’ ability to integrate and reconfigure resources under technological and environmental change (Teece, 2007). Studies also indicate that innovation gains are stronger where partnerships are supported by formal coordination mechanisms and boundary-spanning structures such as liaison offices that facilitate multidisciplinary and explorative research (Lee et al., 2010; Lee, 2011). As barriers decrease and cooperation matures over time, collaboration can accelerate innovation processes and improve outcomes (Benedetti & Torkomian, 2011). Thus, collaboration is hypothesized to have a positive effect on sustainable innovation performance.

- iii.

- Hypotheses on the measurement of sustainable innovation (H5–H6)

H5.

Sustainable innovation characteristics (CSI) load positively and statistically significantly onto the latent construct of innovation.

CSI operationalizes innovation performance as sustainability-oriented outcomes consistent with literature emphasizing that innovation should reflect environmental and social outcomes alongside economic value (Adams et al., 2015; Klewitz & Hansen, 2014). Sustainability transitions research also highlights the role of collaborative innovation processes in accelerating sustainability-oriented change (Orecchini et al., 2012). Therefore, higher levels of CSI are expected to load positively on the innovation construct.

H6.

Sustainable innovation challenges at home (CSIH) load statistically significantly on the latent construct of innovation.

CSIH captures the constraints that shape the feasibility and intensity of sustainable innovation, including infrastructure, regulatory complexity, financing, and culture (Adams et al., 2015). Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) evidence shows that sustainable innovation is frequently hindered by resource limitations, limited awareness, and weak external support linkages (Klewitz & Hansen, 2014). Eco-innovation studies further associate financing constraints with institutional and market barriers, highlighting the importance of intermediaries and policy support in overcoming them (Polzin et al., 2016). Related work stresses that fragmented coordination and weak information infrastructures undermine innovation capacity (Jjagwe et al., 2024). Thus, CSIH is expected to load significantly on the innovation construct as a contextual constraint dimension that co-defines sustainable innovation engagement.

- iv.

- Hypothesis about the robustness of the model (Multi-Group SEM) (H7)

H7.

The relationship between collaboration and innovation remains positive and statistically significant in different subgroups according to company size, gender, educational background, study profile, and economic sector, confirming the structural robustness of the model.

Prior evidence from transition and emerging contexts suggests the magnitude of collaboration benefit may vary with the firm’s resources, leadership, and sectoral characteristics (Ćudić et al., 2022; Kleiner-Schaefer & Schaefer, 2022). Absorptive capacity theory predicts heterogeneous returns because firms differ in their ability to recognize, assimilate, and exploit external knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002). Differences in knowledge alignment and routines can further shape the effect size across contexts and sectors (Boschma, 2005). Yet, dynamic capabilities theory implies collaboration remains a general mechanism for resource reconfiguration and learning, supporting a consistent positive relationship even if the strength differs (Teece, 2007). Multi-group SEM enables testing whether this relationship holds across subgroups while allowing meaningful heterogeneity in coefficients (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000).

Given that the effectiveness of A2B cooperation depends on the broader institutional and innovation-system setting, the next section briefly contextualizes the empirical case in terms of innovation capacity, policy developments, and university–industry linkages.

2.3. Research Context

Sustainable innovation is a highly debated concept worldwide, including in Albania (Adams et al., 2015; Aldeanueva-Fernández & Contreras, 2025). Albania has made progress in digitalization, particularly through a major government campaign to provide online public services through the e-Albania portal, reducing costs for citizens and businesses, and increasing transparency (National Interoperability Framework Observatory [NIFO], 2024). At the same time, the cyberattacks on e-Albania in 2022, together with major data breaches involving bank-related accounts and other breaches, highlighted vulnerabilities in cybersecurity and data protection and the need for stronger innovation-related capabilities (Biberaj et al., 2022).

The institutional framework for innovation is evolving. The Ministry of Economy, Technology and Innovation is reportedly finalizing a new law on innovation and is expected to clarify the functioning of the ecosystem. An Innovation and Excellence Agency (Council of Ministers, 2023) has also been established within the ministry, with a vision oriented towards modernization, innovation and sustainability. In the “National Education Strategy 2021–2026”, a specific objective is the creation of joint cooperation projects between business associations and universities, with international support, including stronger technology transfer mechanisms and curriculum modernization (Ministry of Education and Sports, 2021).

Albania’s position in the Global Innovation Index (GII) confirms that the national innovation system still shows features of immaturity (World Intellectual Property Organization, 2025). In the 2025 edition, Albania ranks 67th overall among world economies. As shown in Table 1, Albania performs best is in Infrastructure (40th) and Institutions (47th), while it ranks much lower in Human capital and research (99th) and Knowledge and technology outputs (85th).

Table 1.

Innovation indices in Western Balkan countries.

Compared to other Western Balkan countries, Albania is below Serbia and North Macedonia in the overall index but performs better than Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia in some pillars, such as Institutions and Business sophistication. However, the country continues to lag behind in Human capital and research and Knowledge and technology outputs, which are areas where stronger academia–business collaboration may have the greatest relevance. These weaknesses are also influenced by path dependence from the centrally planned period prior to the 1990s, when university–industry relations were largely state-directed and market-oriented cooperation mechanisms were limited, contributing to persistent gaps in collaboration routines, intermediary structures, and trust-building processes that are central to the Triple Helix model.

The functioning of the Triple Helix Model of innovation requires adequate investments in R&D and skilled human capital. In 2024, R&D expenditure in Albania was only 0.19% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (see Table 2), compared to an EU average of 2.22% (OECD, 2025). Albania records the lowest share of R&D spending among Western Balkan countries, reflecting weak innovation inputs and limited capacity for knowledge generation and diffusion.

Table 2.

R&D expenditure in Western Balkan countries.

Existing studies on A2B collaboration in Albania underline both its importance and its limitations. Qejvani and Gjipali (2024) argue that universities can take the initiative to strengthen collaboration with the business sector to support capacity building, research and innovation. Çabiri and Qosja (2022) emphasize that such collaboration exists but remains largely driven by the need for skilled employees rather than by innovation-oriented partnerships, and it remains far from a fully developed “Triple Helix”. Similarly, a survey-based study by the Albania Investment Council (2021) reports that 63.4% of companies considered cooperation with academia necessary to respond to recent developments but also emphasizes weak trust and limited incentives for university involvement in R&D.

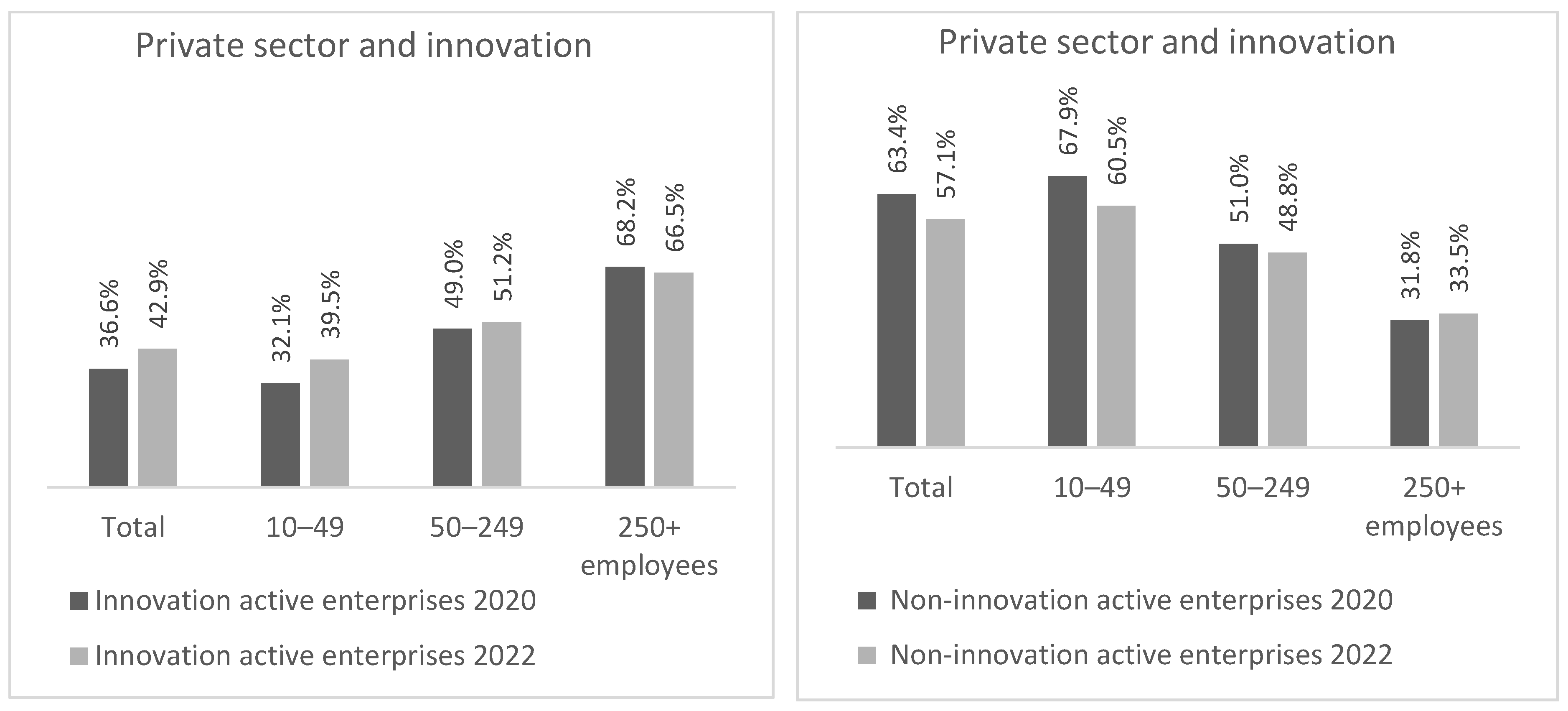

Finally, the broader economic structure reinforces the relevance of A2B collaboration. The OECD, “Economic Convergence Scoreboard for the Western Balkans 2025”, confirms the fundamental role of SMEs in the Albanian economy: in 2020–2023, 82% of employees in Albania worked in SMEs, the highest level in the Western Balkans, and well above the EU average of 64.5% (OECD, 2025). The Institute of Statistics data show an increase in enterprises incorporating innovation between 2018 and 2020 and 2020–2022, especially among SMEs (see Figure 1: Institute of Statistics [INSTAT], 2021, 2024b). However, the same reports highlight persistent constraints related to digitalization, access to finance, and professional capacities, suggesting that more structured and innovation-oriented collaboration between academia and business remains an important path for strengthening sustainable innovation outcomes.

Figure 1.

Private sector engaged in innovation projects. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the data from the Institute of Statistics [INSTAT] (2021, 2024b).

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Instrument Development and Measurement Model Specification

The survey was informed by expert focus groups conducted within the HORIZON-WIDERA-2022 project Upskilling Researchers for Sustainable Entrepreneurship based on Innovation Process Management (USE-IPM)1. A dedicated focus group on “Sustainability and responsible innovation” was held at the Faculty of Economics, University of Tirana, on 2 December 2024, bringing together experts from academia, business, innovation hubs, and legal/consulting practice. The discussion highlighted locally relevant themes, including innovation actors, stages of the innovation process, challenges of sustainable innovation, and perceived drivers of A2B collaboration, which were used to refine item wording and strengthen content validity and contextual relevance (Morgan, 1997; Hinkin, 1998).

Although the items were developed by the authors, the instrument followed a theory-driven process based on established construct streams. Focus groups supported contextual operationalization rather than inductive construct generation. Items were newly formulated but anchored in established conceptual definitions and prior measurement approaches. Constructs and hypothesized relationships were specified a priori, supporting confirmatory CB-SEM to assess the measurement and structural models.

The questionnaire was organized into thematic blocks covering (i) respondents and their firms’ characteristics, (ii) perceived relevance of A2B cooperation, (iii) collaboration channels and practices, (iv) actors, (v) drivers/mechanisms, and (vi) sustainable innovation outcomes and challenges. These were operationalized into the five SEM constructs used in the empirical model: TCAB (Types of cooperation), ACAB (Actors), CMAB (Drivers/mechanisms), CSI (Characteristics of sustainable innovation), and CSIH (Challenges of sustainable innovation at home). Table 3 presents item codes and construct groupings. Most items were closed-ended and measured on a 5-point Likert scale, with a small number of open-ended options to capture additional forms or constraints. This format is widely used in SEM-based survey research, as it provides sufficient response variability while limiting respondent burden (Byrne, 2016; Hair et al., 2018).

Table 3.

Measurement indicators.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample Description

In line with the study’s objective of strengthening A2B cooperation as a path towards sustainable innovation, the target population consisted of active firms in Albania, ensuring coverage across the main Institute of Statistics [INSTAT] (2024a) classification of production and services sectors. Data collection focused primarily on Tirana and Durrës, where 57.7% of Albanian businesses are located (National Business Center, 2024), and was conducted during March–June 2025. In total, 500 questionnaires were distributed both face-to-face and online. After data screening and quality checks, the effective response rate was 59.6%, resulting in a final sample (n = 298). Respondents were senior business representatives (e.g., owners/CEOs, general managers, human resources and finance managers, innovation officers) from firms operating in sectors such as information technology, manufacturing, agriculture, financial services, and tourism. SEM sample adequacy depends primarily on model complexity and parameter estimation; accordingly, the final sample meets common thresholds for confirmatory CB-SEM with reflective constructs and moderate model complexity (Bentler & Chou, 1987; Kline, 2023; Wolf et al., 2013). Table 4 summarizes respondents’ and firms’ characteristics to support assessment of sample coverage.

Table 4.

Overview of respondents.

3.3. CB-SEM Estimation Procedure

The study applies CB-SEM, implemented in the R environment using the lavaan package. CB-SEM was selected because the primary objective of the study is to test and confirm a theoretically grounded model derived from prior literature, rather than to pursue exploratory modeling. The analysis followed a standard two-step procedure consisting of (i) assessment of the measurement model and (ii) estimation of the structural model (Byrne, 2016; Hair et al., 2018; Kline, 2023).

Normality was checked before estimating the SEM. The dataset was first screened to ensure adequate internal consistency and factorability. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α, and distributional assumptions were examined using skewness and kurtosis. Following standard practice, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was then used to identify the underlying structure of the data and reduce the number of observed indicators by grouping items into coherent factors that reflect the intended constructs. The final measurement specification remained theory-driven and was subsequently evaluated confirmatory within the CB-SEM framework using overall model-fit indices and standardized factor loadings.

3.4. Measurement Quality and Factorability Diagnostics

Reliability analysis indicated high internal consistency across all constructs. Cronbach’s α values ranged from 0.78 to 0.86, exceeding the commonly recommended threshold of 0.70 and indicating satisfactory measurement reliability. In particular, the factors TCAB, ACAB, CMAB, and CSI showed very strong reliability (α = 0.86), whereas CSIH also demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.78). Normality diagnostics based on skewness and kurtosis supported the suitability of the data for SEM estimation. Table 5 reports the reliability statistics and distributional diagnostics (mean, standard deviation (SD), skewness and kurtosis) for all constructs included in the model.

Table 5.

Results of reliability analysis and normality test.

Factorability was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. All constructs demonstrated very good sampling adequacy, with KMO values ranging from 0.825 to 0.879, all above the recommended threshold of 0.80. Bartlett’s tests were statistically significant (χ2 ranged from 401.7 to 1151.51, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrices were not an identity matrix and that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Table 6 presents the KMO and Bartlett test results, confirming the suitability of the dataset for factor-based construct assessment.

Table 6.

Scale validity analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Equation Model Results

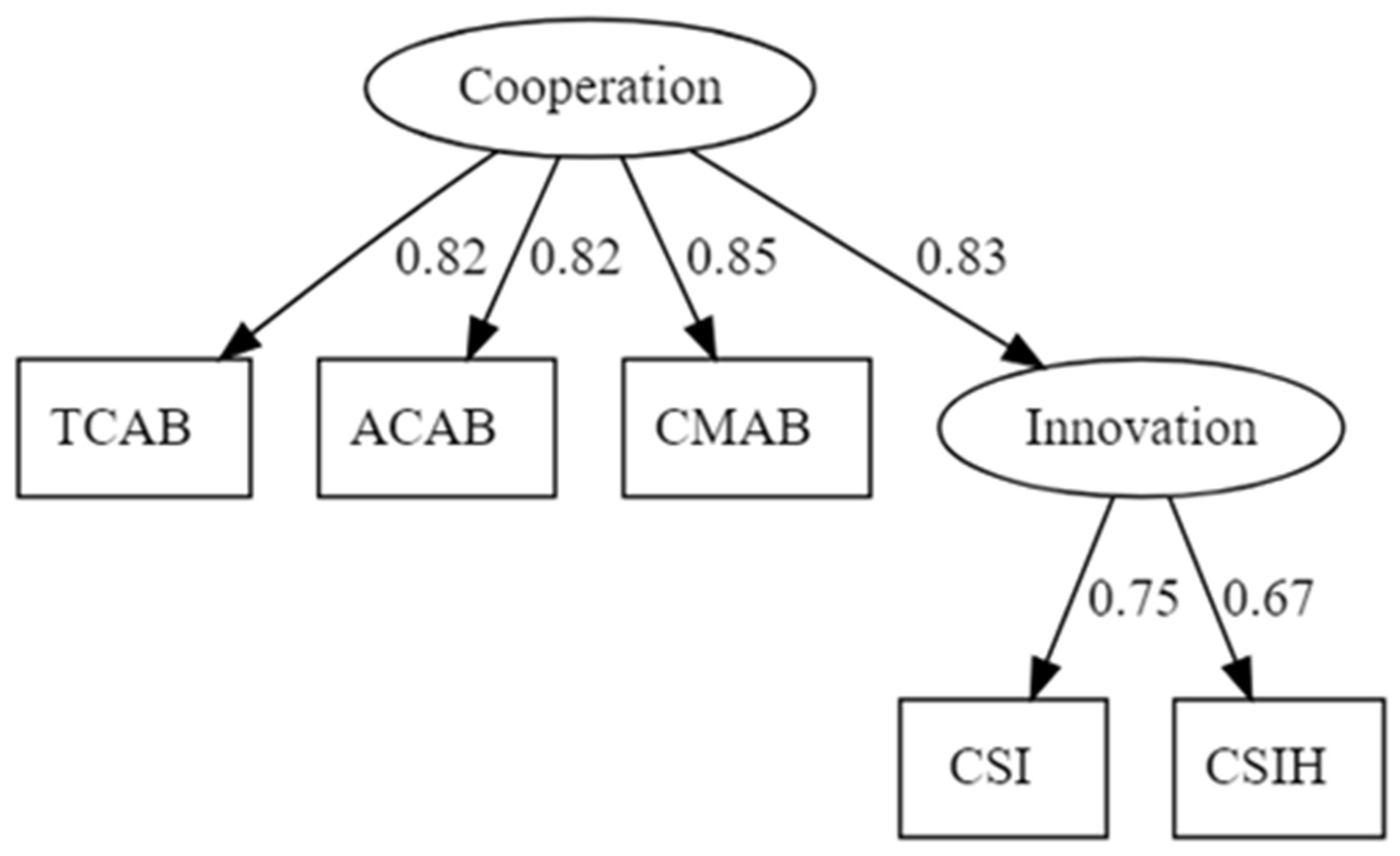

The SEM results show a very good fit to the data. Model fit indices meet commonly recommended thresholds (CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.988; TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index) = 0.987; RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.028; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.059), supporting the adequacy of the proposed structure. The three sub-dimensions of cooperation (TCAB, ACAB, and CMAB) contributed strongly and significantly to the latent construct “Cooperation” (standardized loadings from 0.82 to 0.85; p < 0.001). These results support the multidimensional measurement specification of Cooperation.

Similarly, the two dimensions of innovation (CSI and CSIH) loaded significantly as indicators of the latent construct “Innovation” (standardized loadings 0.67–0.75; p < 0.001). Therefore, H5 and H6 are supported. Structural estimation revealed a very strong and positive effect of Cooperation on Innovation (β = 0.829; p < 0.001), explaining about 69% of the variance of innovation. Accordingly, H4 is supported.

Table 7 reports standardized loadings for the measurement model, the estimated structural path coefficients, and overall model fit results.

Table 7.

Results of the SEM model.

Table 8 presents the explained variance (R2) of the endogenous latent constructs, indicating the model’s explanatory power.

Table 8.

Variance explained/Measurement contribution.

Figure 2 illustrates the CB-SEM model, including standardized loadings and the structural effect of Cooperation on Innovation. Cooperation is strongly characterized through three factors (TCAB, ACAB, and CMAB; loadings 0.82–0.85) and has a strong and significant impact on “Innovation” (β = 0.83), which is measured by CSI (0.75) and CSIH (0.67).

Figure 2.

Sub-dimensions of cooperation and effects on innovation. Source: SEM results by authors’ illustrations. Note: All presented coefficients are standardized and statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Table 9 confirms that “Cooperation” has a positive, strong, and statistically significant impact on “Innovation”. The regression coefficient (Estimate = 1.481) is high, with a z-value of 6.077 and a p-value < 0.001, confirming that the relationship is statistically significant. Accordingly, H4 is supported.

Table 9.

Results of regression analysis.

4.2. Item-Level Loadings and Key Contributors

To provide a more detailed interpretation of the constructs, item-level factor loading intervals and most influential indicators within each sub-variable are summarized. Within TCAB, the strongest forms of collaboration include the use of research laboratories, technological solutions provided by universities and bilateral research projects. For ACAB, entrepreneurs, investors, and research centers emerged as the most influential actors. CMAB was the strongest cooperation sub-construct, with innovation culture, educational programs and research incubators contributing most strongly. On the innovation side, CSI showed the strongest contribution through environmental responsibility, social impact, adaptability and flexibility, and circular economy practices. Furthermore, CSIH highlighted the core obstacles, particularly lack of public awareness and regulatory complexity.

Table 10 summarizes the factor loading intervals and the most influential items within each construct.

Table 10.

Summary of factor loading interval for each item.

4.3. Robustness Checks: Multi-Group SEM

To assess the stability of the proposed relationship across different organizational and demographic contexts, a multi-group SEM analysis was conducted. This methodological approach is recommended to evaluate the structural invariance of models by comparing path coefficients between latent constructs in different subgroups (Byrne, 2016; Hair et al., 2018).

Latent composites were constructed for “Cooperation” (constructed from dimensions of TCAB, ACAB, and CMAB) and “Innovation” (constructed from dimensions of CSI and CSIH). Subsequently, the sample was divided by company size, gender, education level and study profile. Structural regressions were estimated for each group with Innovation regressed on Cooperation. To improve inference robustness, 95% bootstrap confidence intervals were estimated using 1000 replications (Tibshirani & Efron, 1993).

Table 11 reports the sample size for each group, standardized path coefficients (β), 95% confidence intervals and R2 values. The comprehensive results provided an assessment related to the effects’ robustness and the potential presence of structural heterogeneity across groups (Kline, 2023).

Table 11.

Multi-group SEM results.

Across all subgroups, the relationship between Cooperation and Innovation remains positive and statistically significant in most subgroups, although its intensity varies somewhat across subgroups. The effect is strongest for medium-sized firms (β = 0.851, 95% CI [0.647, 1.039], R2 = 0.497) compared with large firms (β = 0.583) and small firms (β = 0.481). Regarding gender, both groups show similar coefficients, with a slightly higher impact among female respondents (β = 0.669) than among males (β = 0.579). According to education level, respondents with the second cycle of tertiary education group showed the strongest effect (β = 0.720), whereas the third cycle of tertiary education group displayed a low and unstable coefficient (β = 0.230), due to the very small sample size. Furthermore, the study profile of natural sciences demonstrated the highest effect (β = 0.790), suggesting that fields with a more pronounced research orientation benefit more from the collaboration mechanisms.

Overall, the multi-group SEM analysis confirms that the model is robust across different groups, reinforcing the validity of the main conclusions: cooperation between academia and business remains a crucial driver of innovation across company characteristics and respondents’ demographic profiles. Therefore, H7 is supported.

5. Discussion

The descriptive results indicate that collaboration between firms and universities in Albania remains underdeveloped. While 51% of respondents report having participated in collaborations with universities or research institutions, 49% report no such involvement. Moreover, 41% state that their company has never engaged in academia–business collaboration, whereas only a minority report collaborating regularly or continuously. These descriptive patterns suggest that, although collaboration exists, it is not yet a systematic practice for many companies in Albania, in line with previous evidence that the university-industry linkages in the country remain relatively weak (Çabiri & Qosja, 2022, 2023; Ćudić et al., 2022). From an innovation-systems perspective, this pattern suggests that key linkages and intermediary functions are not yet institutionalized. As a result, A2B cooperation is not yet a routine innovation mechanism. The sample mainly includes small and medium-sized firms, consistent with the broader structure of the Albanian economy. Most respondents hold tertiary education and work in service and professional sectors, consistent with the economy’s service-oriented business profile. Hypotheses H1–H3 proposed that the types of cooperation (TCAB), actors involved (ACAB) and cooperation drivers/mechanisms (CMAB) contribute positively to the formation of the collaboration construct. The SEM results confirm that all three dimensions load strongly and significantly on “Cooperation”, indicating that collaboration is shaped not only by the intensity of cooperation practices but also by ecosystem awareness and institutional support conditions. In descriptive terms, collaboration most frequently occurs through internships, joint research projects, knowledge transfer activities, training programs, and the use of university facilities. These channels are aligned with international evidence that student engagement, joint research and technology transfer are among the most common forms of academia–business interaction (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015; D’Este & Patel, 2007; Perkmann et al., 2013). The findings suggest that cooperation is often focused on skills development, while deeper, long-term co-development remains limited. This conclusion fits open innovation arguments that innovation depends not only on breadth but also on depth of knowledge integration.

The results further highlight that actors such as entrepreneurs, investors and research centers emerge as central contributors within ACAB, implying that A2B cooperation is set in a broader innovation ecosystem, beyond the traditional academia–business “dyad”. This finding aligns with evidence highlighting the role of intermediaries, ecosystem actors and market-oriented stakeholders in strengthening A2B cooperation outcomes (Alexandre et al., 2022; Albats et al., 2022). Respondents also identified several forms of support that could improve cooperation between companies and academia, including government incentives and funding, dedicated liaison offices, partnership agreements, networking activities and joint workshops, and awareness campaigns about the benefits of cooperation (Bu et al., 2025).

The strong role of CMAB suggests that innovation culture, educational programs and research incubators are perceived as critical enabling mechanisms, consistent with prior work highlighting the importance of intermediary structures, governance mechanisms and trust-building processes in effective A2B collaboration (Bruneel et al., 2010; Muscio & Vallanti, 2014). In the findings, the core supports identified are government incentives and funding (30%) and more networking activities and joint workshops (24%). This mirrors results from other Western Balkan and emerging economies, where limited funding and weak intermediary organizations are seen as key obstacles to collaboration (Ćudić et al., 2022; Kleiner-Schaefer & Schaefer, 2022). Hypothesis H4 proposed that A2B collaboration is positively associated with innovation. SEM results indicate a strong and statistically significant relationship between “Cooperation” and “Innovation”, suggesting that firms that engage more intensively and strategically in A2B collaboration tend to report higher levels of sustainable innovation. Importantly, this relationship should be interpreted as an association rather than a causal effect, given the cross-sectional and self-reported data. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with international literature linking A2B collaboration to knowledge acquisition, stronger dynamic capabilities and sustainability-oriented innovation (Arroyave et al., 2020; Bu et al., 2025; Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006; Laursen & Salter, 2006). The reported collaboration channels also reflect capability-building. Internships and training can strengthen skills, routines, and learning. However, the limited use of academic outputs suggests weak absorptive capacity. This may constrain how well cooperation translates into innovation. In the Albanian context, where the innovation system remains at an early stage, the findings suggest that strengthening A2B cooperation may represent an important way to support digital and green transition objectives. Hypotheses H5 and H6 propose that innovation is best captured through both sustainable innovation characteristics (CSI) and challenges of sustainable innovation at home (CSIH). The SEM results support this multidimensional conceptualization, as both CSI and CSIH load significantly on the latent “Innovation” construct. This indicates that innovation in transition settings is not only expressed through positive sustainability-oriented practices and outcomes but also shaped by persistent constraints such as weak infrastructure, limited financing, low public awareness, and regulatory complexity. Respondents also reported the technologies and innovation types adopted by their firms. Innovation activities were concentrated in domains linked to the digital and green transition. The most frequently adopted technologies and innovation types include artificial intelligence and big data solutions (37%), product or service innovation (17%), digitalization and automation of processes (16%), and renewable energy and green technologies (11%). This pattern is consistent with recent evidence suggesting that sustainability-oriented innovation is increasingly shaped by digital technologies, data-driven solutions, and green transition priorities (Arroyave et al., 2020; Bu et al., 2025). The descriptive results reinforce this interpretation: 62% of companies report not using technologies or research outputs developed by academia, highlighting a gap in absorptive capacity and knowledge transfer, consistent with findings in emerging markets where firms most often face information constraints and limited innovation capability (Kleiner-Schaefer & Schaefer, 2022).The multi-group SEM results show that the positive Cooperation–Innovation relationship remains statistically significant across subgroups defined by company size, managers’ gender, education level, and study profile, supporting H7. Although the relationship is stable across all groups, the strength of the effect varies. The effect was strongest among medium-sized firms, while it was comparatively weaker for small and large firms. Respondents with a natural science background also showed a stronger relationship, suggesting that research-oriented knowledge bases may enhance the innovation benefits of cooperation. This interpretation aligns with the cognitive proximity argument, which emphasizes that closer knowledge alignment facilitates interactive learning and knowledge transfer in collaboration settings (Boschma, 2005). These subgroup patterns are consistent with capability-based and absorptive-capacity perspectives, which suggest that firms differ in how effectively they translate external collaboration into innovation due to variations in resources, learning routines, and human capital (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002; Teece, 2007). Medium-sized firms may combine adequate organizational capacity with strong incentives to rely on external knowledge, while smaller firms may be constrained by limited resources and larger firms may have more internalized innovation routines. Regarding manager gender, the differences were modest, with slightly higher effects among female-led firms than male-led firms. This is consistent with emerging evidence from firms in emerging economies showing that female managers are positively associated with green and environmental innovation and that this relationship may depend on firm capacity (Mansour et al., 2024). However, these differences should be interpreted cautiously, as they may reflect strategic orientation and perception differences rather than structural divergence.

The survey indicates strong potential for expanding A2B cooperation, as 91% of companies express interest in participating in future joint R&D projects with universities. The main areas of interest are concentrated in digital technology and innovation (64%), data management and artificial intelligence (14%), and renewable energy and the circular economy (11%). The priorities reflect global trends in sustainable innovation, where digitalization, AI and green technologies are seen as key domains for collaboration with universities (Adams et al., 2015; Bu et al., 2025; Evans et al., 2023). At the same time, the gap between high stated interest and limited regular collaboration suggests that stronger enabling mechanisms are needed to translate intentions into sustained cooperative projects. In innovation-systems terms, the gap points to missing institutional support. Funding tools, intermediaries, and coordination platforms are needed to turn interest into long-term projects. This study has some limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional and based on self-reported responses, which limits causal inference; therefore, findings should be interpreted as associations consistent with the conceptual model rather than proof of causality. Second, reliance on a single survey source introduces the possibility of common method bias, although diagnostic checks were applied. Third, the instrument includes newly formulated measures adapted to a transition-economy context; despite satisfactory reliability, additional validation would strengthen comparability with other contexts. Finally, subgroup comparisons in multi-group SEM are limited by unequal group sizes (e.g., a very small doctoral-level group), which may reduce stability in specific estimates. Future research could address these limitations using longitudinal designs, multi-source data, and expanded sampling across sectors and regions.

6. Conclusions

This study shows that A2B cooperation in Albania is still limited and fragmented, even though stakeholders widely recognize its importance for sustainable innovation. Most cooperation remains concentrated in relatively basic activities, such as student internships and training, while deeper forms, such as joint research and co-created innovation projects, are still uncommon. At the same time, firms express clear interest in stronger links with academia, especially in digital technologies, artificial intelligence, and sustainable innovation. This gap between interest and practice suggests significant, yet underused, potential for expanding A2B partnerships.

The CB-SEM results also indicate that when A2B cooperation becomes more intensive and better organized, firms tend to achieve higher levels of sustainable innovation. The findings support treating cooperation as a multidimensional phenomenon shaped by the forms it takes, the actors involved, and the organizational mechanisms that enable collaboration. Moreover, the latent cooperation construct is strongly and statistically significantly associated with firms’ innovation performance. Notably, the relationship holds across firm size categories, implying that effective cooperation mechanisms can benefit not only large enterprises but also SMEs operating within an innovation system that is still developing. Overall, the evidence positions A2B cooperation as a capability-building path through which firms access complementary knowledge and translate it into sustainable innovation outcomes, even in the institutional conditions typical of transition economies.

From a policy perspective, progress is likely to come less from simply expanding the range or frequency of cooperation activities and more from strengthening the enabling mechanisms that make cooperation work over time, including predictable funding, intermediary capacity, transparency, and clear IP arrangements. This points to the need for stable, transparent instruments that support long-term partnerships: predictable funding for joint projects, stronger intermediary capacity to match firms with relevant academic expertise, and targeted capacity-building so both sides can manage collaboration more effectively. Policymakers can reinforce these efforts by reducing administrative and regulatory barriers and by clarifying expectations around engagement, including requirements for transparency and clear intellectual property arrangements. In line with the model’s emphasis on CMAB, the broader aim is to move from isolated initiatives toward an enabling infrastructure that makes cooperation repeatable, trusted, and results-oriented—particularly in areas linked to digitalization and the sustainable transition.

Future research could extend this analysis to other Western Balkan countries and use longitudinal and multi-source designs to strengthen causal inference. Mixed-method approaches may also offer deeper insight into how trust, governance, intermediary support, and absorptive capacity shape the innovation outcomes of academia–business cooperation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and B.L.; methodology, P.G., A.T. and S.P.; software, A.T.; validation, P.G., D.K. and B.L.; formal analysis, P.G. and A.T.; investigation, B.L.; resources, D.K.; data curation, A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G. and A.T.; writing—review & editing, P.G. and A.T.; visualization, A.T.; supervision, B.L.; project administration, P.G.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the 101120390-USE IPM-HORIZON-WIDERA-2022-TALENTS-03-01project, funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the European Research Executive Agency can beheld responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study employed two non-interventional methods (focus groups followed by a survey) and did not involve experiments, clinical procedures, or the collection of sensitive or identifiable personal data. In accordance with the Albanian legal and institutional framework governing research ethics and personal data protection (Law No. 109/2024), the study was classified as minimal risk; therefore, formal approval from an institutional ethics committee was not required under the regulations applicable at the time of data collection. All procedures were conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975; revised 2013). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions; however, anonymized data and the questionnaire are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| A2B | Academia–Business |

| ACAB | Actors of Cooperation Academia–Business |

| CMAB | Cooperation Model Academia–Business |

| CSIH | Challenges of Sustainable Innovation at Home |

| CSI | Characteristics of Sustainable Innovation |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GII | Global Innovation Index |

| IP | Intellectual Property |

| INSTAT | Institute of Statistics (Albania) |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| NIFO | National Interoperability Framework Observatory |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SMEs | Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises |

| TCAB | Type of Cooperation Academia–Business |

| WIPO | World Intellectual Property Organization |

Note

| 1 | See https://useipm.com/ (accessed on 16 June 2025). |

References

- Adams, R., Jeanrenaud, S., Bessant, J., Denyer, D., & Overy, P. (2015). Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(2), 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albania Investment Council. (2021). Improvement of transparency and investment climate. Available online: https://www.investment.com.al/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/AIC_On-the-Improvement-of-the-Investment-Climate-2015-2021.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Albats, E., Alexander, A. T., & Cunningham, J. A. (2022). Traditional, virtual, and digital intermediaries in university-industry collaboration: Exploring institutional logics and bounded rationality. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 177, 121470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeanueva-Fernández, I., & Contreras, F. (2025). Drivers and outcomes of sustainable innovation in the business and management field: A systematic literature review. Schmalenbach Journal of Business Research, 77, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, F., Costa, H., Faria, A. P., & Portela, M. (2022). Enhancing university–industry collaboration: The role of intermediary organizations. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 47, 1584–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaydın, U. A. R., & Fitjar, R. D. (2024). How do university-industry collaborations benefit innovation? Direct and indirect outcomes of different collaboration types. Growth and Change, 55(2), e12721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, S., & Al-Tabbaa, O. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J. A., & Sharma, S. (2003). A contingent resource-based view of proactive corporate environmental strategy. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave, J. J., Sáez-Martínez, F. J., & González-Moreno, Á. (2020). Cooperation with universities in the development of eco-innovations and firms’ performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 612465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belitski, M., Aginskaja, A., & Marozau, R. (2019). Commercializing university research in transition economies: Technology transfer offices or direct industrial funding? Research Policy, 48(3), 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M. H., & Torkomian, A. L. V. (2011). Uma análise da influência da cooperação universidade-empresa sobre a inovação tecnológica. Gestão & Produção, 18, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biberaj, A., Sheme, E., Rakipi, A., Xhaferllari, S., Kushe, R., & Alinci, M. (2022). Cyber-attack against E-Albania and its social, economic and strategic effects. Journal of Corporate Governance, Insurance, and Risk Management, 9(2), 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K., D’Este, P., & Neely, A. (2011). Gaining from interactions with universities: Multiple methods for nurturing absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 40(1), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Brouwers, H. E. J. (2010). Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(7), 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimble, P., & Doner, R. F. (2007). University–industry linkages and economic development: The case of Thailand. World Development, 35(6), 1021–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J., D’Este, P., & Salter, A. (2010). Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university–industry collaboration. Research Policy, 39(7), 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F., Tian, X., Sun, L., Zhang, M., Xu, Y., & Guo, Q. (2025). Research on the impact of university–industry collaboration on green innovation of logistics enterprises in China. Sustainability, 17(11), 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiman, B., & Veugelers, R. (2006). In search of complementarity in innovation strategy: Internal R&D and external knowledge acquisition. Management Science, 52(1), 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Ministers. (2023). Decision no. 620, dated 1 November 2023: On the establishment, organization and functioning of the Innovation and Excellence Agency. Available online: https://qbz.gov.al/share/gvUQMIvzSYqTUdB1SE0-XQ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Cvetanović, S., Ilić, V., Despotovic, D., & Nedić, V. (2015). Knowledge economy readiness, innovativeness and competitiveness of the Western Balkan countries. Industrija, 43(3), 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabiri, K. M., & Qosja, E. (2022). A synthesis of the current situation of university-industry cooperation in Albania following the Triple Helix Model. Economicus, 22, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabiri, K. M., & Qosja, E. (2023). Challenges of university–industry cooperation in Albania. International Journal of Management, Knowledge and Learning, 12(SI), 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ćudić, B., Alešnik, P., & Hazemali, D. (2022). Factors impacting university–industry collaboration in European countries. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Couto, J. P., & Natário, M. M. S. (2023). Sustainable Innovation. In S. O. Idowu, R. Schmidpeter, N. Capaldi, L. Zu, M. Del Baldo, & R. Abreu (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management (pp. 3544–3549). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotovic, D. Z., Cvetanović, S. Ž., & Nedić, V. M. (2014). Innovativeness and competitiveness of the Western Balkan countries and selected EU member states. Industrija, 42(1), 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University–industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36(9), 1295–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maria, E., De Marchi, V., & Spraul, K. (2019). Who benefits from university–industry collaboration for environmental sustainability? International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(6), 1022–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N., Miklosik, A., & Du, J. T. (2023). University-industry collaboration as a driver of digital transformation: Types, benefits and enablers. Heliyon, 9(10), e21017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitjar, R. D., & Gjelsvik, M. (2018). Why do firms collaborate with local universities? Regional Studies, 52(11), 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattringer, R., Hutterer, P., & Strehl, F. (2014). Network-structured university-industry collaboration: Values for the stakeholders. European Journal of Innovation Management, 17(3), 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2018). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage India. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S. L., & Dowell, G. (2011). A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermundsdottir, F., & Aspelund, A. (2021). Sustainability innovations and firm competitiveness: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280, 124715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Statistics (INSTAT). (2021). Innovation activities in enterprises. 2018–2020. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/media/8661/innovation_2018-2020_anglisht.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Institute of Statistics (INSTAT). (2024a). Active legal units by economic activity and size. 2024. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/en/themes/industry-trade-and-services/business-registers (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Institute of Statistics (INSTAT). (2024b). Innovation activities in enterprises. 2020–2022. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/media/13558/innovation_2020-2022.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Jing, L. C. (2024). How does university-industry collaboration drives the green innovation? SAGE Open, 14(3), 21582440241274500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirapong, K., Cagarman, K., & von Arnim, L. (2021). Road to sustainability: University–start-up collaboration. Sustainability, 13(11), 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jjagwe, R., Kirabira, J. B., Mukasa, N., & Amanya, L. (2024). The drivers and barriers influencing the commercialization of innovations at research and innovation institutions in Uganda: A systemic, infrastructural, and financial approach. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner-Schaefer, T., & Schaefer, K. J. (2022). Barriers to university–industry collaboration in an emerging market: Firm-level evidence from Turkey. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 47(3), 872–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J., & Hansen, E. G. (2014). Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kostoska, O., & Hristoski, I. (2017). IKT i inovacije za konkurentnost: Zapadni Balkan vis-à-vis Europske Unije. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci: Časopis Za Ekonomsku Teoriju i Praksu, 35(2), 487–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, M., & Muradzada, N. (2024). No interaction, no problem? An investigation of organizational issues in the university–industry–government triad in a transition economy. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27(2), 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. J. (2011). From interpersonal networks to inter-organizational alliances for university–industry collaborations in Japan: The case of the Tokyo Institute of Technology. R&D Management, 41(2), 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. J., Ohta, T., & Kakehi, K. (2010). Formal boundary spanning by industry liaison offices and the changing pattern of university–industry cooperative research: The case of the University of Tokyo. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(2), 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M., Shubita, M. F., Lutfi, A., Saleh, M. W., & Saad, M. (2024). Female CEOs and green innovation: Evidence from Asian firms. Sustainability, 16(21), 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Sports. (2021). National education strategy 2021–2026. Available online: https://arsimi.gov.al/en/arsimi-i-larte/reforma-ne-arsimin-e-larte/strategjia-kombetare-per-arsimin-2021-2026/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (Vol. 16). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Muscio, A., & Vallanti, G. (2014). Perceived obstacles to university–industry collaboration: Results from a qualitative survey of Italian academic departments. Industry and Innovation, 21(5), 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Business Center. (2024). Business demographics in Albania 2024. Available online: https://qkb.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Raport-Vjetor-per-Regjistrin-Tregtar-Regjistrin-e-Licencave-Autorizimeve-dhe-Lejeve-dhe-Regjistrin-e-Pronareve-Perfitues-2024.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- National Interoperability Framework Observatory (NIFO). (2024). Digital public administration factsheet: Albania. Interoperable Europe, European commission. Available online: https://interoperable-europe.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/inline-files/NIFO_2024%20DPAF_Albania_vFinal_rev.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Nie, L., Gong, H., Zhao, D., Lai, X., & Chang, M. (2022). Heterogeneous knowledge spillover channels in universities and green technology innovation in local firms: Stimulating quantity or quality? Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 943655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2025). Economic convergence scoreboard for the Western Balkans 2025. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchini, F., Valitutti, V., & Vitali, G. (2012). Industry and academia for a transition towards sustainability: Advancing sustainability science through university–business collaborations. Sustainability Science, 7(Suppl. 1), 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’Este, P., Fini, R., Geuna, A., Grimaldi, R., Hughes, A., Krabel, S., Kitson, M., Llerena, P., Lissoni, F., Salter, A., & Sobrero, M. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, F., von Flotow, P., & Klerkx, L. (2016). Addressing barriers to eco-innovation: Exploring the finance mobilisation functions of institutional innovation intermediaries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 103, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qejvani, O., & Gjipali, D. (2024). Business and academia collaboration: Empowering internationalization in Albania. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research and Development, 11(1 S1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossoni, A. L., de Vasconcellos, E. P. G., & de Castilho Rossoni, R. L. (2024). Barriers and facilitators of university-industry collaboration for research, development and innovation: A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly, 74(3), 1841–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P., Geoghegan, W., & Hilliard, R. (2018). The microfoundations of firms’ explorative innovation capabilities within the triple helix framework. Technovation, 76, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilikova, A., Kuryłowicz, M., Lyeonov, S., & Vasa, L. (2023). University-industry collaboration in R&D to reduce the informal economy and strengthen sustainable development. Economics & Sociology, 16, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, T. (2013). Critical success factors for knowledge transfer collaborations between university and industry. Journal of Research Administration, 2(44), 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöö, K., & Hellström, T. (2019). University–industry collaboration: A literature review and synthesis. Industry and Higher Education, 33(4), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. J., & Efron, B. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varblane, U., Mets, T., & Ukrainski, K. (2008). Role of university–industry–government linkages in the innovation processes of a small catching-up economy. Industry and Higher Education, 22(6), 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(6), 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Intellectual Property Organization. (2025). Global innovation index 2025: Innovation at a crossroads—Unlocking the promise of social entrepreneurship. World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S., Zhou, Y., Wang, Z., He, Q., & Parry, G. (2025). Enhancing green innovation through university–industry collaboration and artificial intelligence: Insights from regional innovation systems in China. The Journal of Technology Transfer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Wang, C., Ying, H., Jiang, H., & Fu, Z. (2025). Review on barriers and drivers of university–industry collaborative innovation: A stakeholder perspective. Sustainable Futures, 9, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.