Abstract

Hybrid work not only redistributes where employees work; it also reshapes how they stay connected to their colleagues. Drawing on Communicate–Bond–Belong (CBB) theory, we examine how daily work location shapes employees’ team commitment in hybrid work environments through informal communication and knowledge sharing, and how these daily links depend on task interdependence. Using a daily diary study with 219 employees who work at least one day a week from home and one day a week in the office (1655 day-level observations), we applied multilevel structural equation modeling in Mplus 8.8 to capture within-person day-to-day fluctuations. Our findings show that on days when employees worked from home rather than in the office, they reported less informal communication and less knowledge sharing with colleagues, which in turn related to lower team commitment. These indirect effects suggest that it is not physical distance per se, but the loss of cue-rich, relationship-building and task-related exchanges that erodes commitment on remote days. We further show that task interdependence differentially qualifies these daily relationships: for informal communication, the positive association with commitment is stronger when task interdependence is low and weaker when interdependence is high. In contrast, the positive association between knowledge sharing and commitment becomes stronger at higher levels of task interdependence. Together, the results advance understanding of social dynamics in hybrid work environments and offer actionable guidance for leaders and organizations.

1. Introduction

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, telecommuting arrangements in organizations have increased substantially. While most employees were initially compelled to work from home, many came to value the benefits of remote work and wanted to continue working regularly from home even after lockdown restrictions were lifted (McPhail et al., 2024). Large international surveys reflect this shift, indicating that around one-third of employees now follow either a fully remote or a hybrid working model (Aksoy et al., 2022). Hybrid work is generally understood as an umbrella term for arrangements with at least one day a week working from home and one day a week working in the office (e.g., Grzegorczyk et al., 2021; Leonardi et al., 2024; Vartiainen & Vanharanta, 2024). Although such models promise benefits, such as improved work–life balance, greater flexibility, autonomy, and enhanced retention (Al-Habaibeh et al., 2021; Gajendran et al., 2024), they also reconfigure when, where, and how coworkers interact. This raises new questions about the conditions under which hybrid arrangements support, rather than undermine, core team processes such as coordination, knowledge sharing, and commitment (Leonardi et al., 2024).

To answer these questions, prior research has examined how working from dispersed locations affects teamwork, with a strong emphasis on outcomes such as performance and well-being (e.g., Handke et al., 2022; Toscano et al., 2025; Shockley et al., 2021). These studies show, among other things, that it is not physical distance per se that impedes teamwork but rather the lack of frequent, high-quality communication and the coordination difficulties created by asynchronous schedules, fragmented communication channels, and variable co-presence (Handke et al., 2020; Hinds & Mortensen, 2005; Shockley et al., 2021; Mabaso & Manuel, 2023). While these studies provide important first insights, they typically treat teamwork and communication as relatively stable, between-person characteristics (e.g., employees who work more vs. less remotely). This perspective may be appropriate in fully remote settings, but under hybrid work, team communication is better understood as context-dependent, day-to-day behavior that fluctuates with changes in work location. The prevailing focus on between-person variance has therefore obscured the dynamic nature of communication in hybrid teams and left theoretical gaps regarding how hybrid work shapes within-person fluctuations in employees’ communication with their coworkers over time.

Moreover, while existing studies have linked remote work to individual well-being and performance, fewer have examined its consequences for bonding and interpersonal relationships within teams (e.g., Chinyuku & Qutieshat, 2025; Mehrabi et al., 2025; Flavián et al., 2022). We address this gap by focusing on affective team commitment, which reflects how psychologically connected employees feel to their team. Although team commitment is a central antecedent of retention and the preservation of knowledge within organizations (Wombacher & Felfe, 2017), we still lack a fine-grained understanding of how hybrid work shapes it in employees’ daily working lives, and under which conditions remote work undermines versus sustains it. As hybrid work becomes more prevalent, organizations therefore need clearer, evidence-based guidance on how to design and manage communication in hybrid teams so that commitment is preserved rather than weakened (Grzegorczyk et al., 2021).

Drawing on Communicate–Bond–Belong (CBB) theory, we argue that commitment is built through communication: people communicate not only to exchange information but also to create bonds and satisfy belonging needs (Hall & Davis, 2017). To investigate the role of communication, we follow prior work and distinguish between relational communication, captured by informal, nonwork-related conversations, and task-oriented communication, captured by daily knowledge sharing (Lütjens & Felfe, 2025; Marlow et al., 2018). Both can foster commitment, but their effectiveness is constrained in remote work due to the lack of cue-rich, serendipitous encounters and ambient awareness (Lütjens & Felfe, 2025; Leonardi et al., 2024; Vartiainen & Vanharanta, 2024). Further, we propose that the extent to which communication translates into commitment depends on task interdependence, which describes how closely team members must work together to accomplish their tasks (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006).

In sum, we suggest that work location shapes core communication processes. On days when employees work remotely (vs. in the office), they engage in less informal communication and less knowledge sharing with their team members, which translates into lower same-day team commitment. Further, we propose that, in this context, task interdependence conditions how strongly informal communication and knowledge sharing translate into daily commitment. We test this model using a two-week daily diary design.

Our study makes four main contributions. First, we shift the focus from where people work to how work location alters core social and formal communication processes that underpin commitment. Drawing on daily variation in work location, informal communication, and knowledge sharing, we show that remote work is linked to team commitment indirectly through these two communication forms. This extends CBB theory by clarifying how informal communication and knowledge sharing jointly translate everyday talk into bonding and a sense of belonging (Hall & Davis, 2017). Second, by using a daily within-person design, we move beyond the dominant between-person perspective and demonstrate that communication and commitment are not static traits but fluctuate with employees’ day-to-day work context (e.g., Gajendran & Joshi, 2012; van Zoonen & Sivunen, 2022; Fuchs & Reichel, 2023). This approach allows us to capture how the same individuals experience different patterns of communication and commitment on remote versus office days. Third, by positioning task interdependence as a structural boundary condition for the daily communication–commitment link, we offer a clear contingency perspective on how commitment is created in hybrid teams. Fourth, we argue that hybrid work should be actively designed rather than merely permitted, and we derive practical recommendations for how organizations can preserve team commitment by encouraging informal, nonwork-related exchanges and improving knowledge-sharing processes.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Remote Work and Informal Communication

Informal nonwork-related communication refers to unplanned, spontaneous interactions that occur outside formal meetings and structural workflow (Singh & Denner, 2025). It encompasses brief exchanges before or after meetings, hallway chats, light-touch check-ins, or nonwork-related small talk that emerges organically in the flow of work (Kraut et al., 1990; Fay & Kline, 2011; Sias, 2008). These moments are low-stakes but socioemotionally rich. They enhance positive emotions at work and create opportunities to signal availability and warmth, share quick context, and reinforce a felt sense of connection (Fay & Kline, 2011; Holmes & Marra, 2004; Nardi & Whittaker, 2002; Methot et al., 2021). A suitable environment for informal communication at work is typically characterized by spatial and visual proximity, shared spaces, and small pockets of unstructured time. Open-plan offices, shared corridors, break areas, and pre- or post-meeting “buffer times” create frequent opportunities for incidental encounters and quick, low-effort greetings (Nardi & Whittaker, 2002; Kraut et al., 1990). In addition, informal exchanges are more likely when there is psychological safety and local norms that legitimize brief nonwork talk during the workday rather than treating it as a distraction (Fay & Kline, 2011; Sias, 2008). In such environments, employees can easily notice when others are present and approachable, which lowers the threshold to initiate short, relationship-building conversations.

While the impact of informal conversations was long neglected in team research, it has gained renewed attention with the rise of remote work and the accompanying decline in opportunities for informal contact (e.g., Begemann et al., 2024; Viererbl et al., 2022). Building on previous research that examined leader–follower informal communication in remote versus co-located settings and its relevance for transformational leadership, we likewise expect informal conversations between employees and their team members to decline on days they work from home compared to days they work in the office (Lütjens & Felfe, 2025). While co-presence creates a suitable environment for informal communication (e.g., spontaneous encounters in the break room), in remote work informal communication may decline due to the lack of rich social cues and situational affordances (Viererbl et al., 2022). Here, interactions are mediated and often pre-planned, with awkward turn-taking and fewer nonverbal signals (Lal et al., 2021). Even when contact occurs remotely, it is typically more goal-directed and time-bounded, and the absence of nonverbal cues makes others’ moods and emotions harder to read, hindering the formation of expressive ties (Wang et al., 2021; Tautz et al., 2022). Consequently, on remote workdays, informal exchanges with coworkers should decline relative to days in the office, not because employees are less motivated to connect, but because the interaction ecology affords fewer spontaneous openings for brief, relationship-building talk.

H1.

On days when employees work from home (vs. in the office), they report less informal communication with team members.

2.2. Remote Work and Knowledge Sharing

Beyond informal communication, we also expect knowledge sharing—as a more formal, task-focused component of communication—to decline on remote workdays. Knowledge sharing captures the exchange of know-how, advice, and contextual information that enables coordination and collective sensemaking. It thrives on visibility (knowing who knows what and who needs what), timing (catching issues early), and low initiation costs for quick questions and unsolicited tips (Kim & Yun, 2015). Office co-presence supports these conditions through overhearing, workplace visibility, and opportunistic encounters that trigger “just-in-time” help.

By contrast, remote work weakens ambient awareness (fewer cues about others’ availability and problems), increases the activation energy required to ask for or offer help (a message or meeting must be deliberately initiated), and shifts interaction to leaner or asynchronous media, which can slow clarification loops (Leonardi & Treem, 2020; Begemann et al., 2024; Tautz et al., 2022). Thus, we propose that on remote workdays (vs. office days), employees engage in less knowledge sharing with their coworkers.

H2.

On days when employees work from home (vs. in the office), they report less knowledge sharing with team members.

2.3. Communicate–Bond–Belong Theory and Team Commitment in Hybrid Work

Further, we argue that the physical separation of team members on remote workdays reduces employees’ current experience of team commitment because it disrupts the everyday interactions through which social bonds are created and sustained. Team commitment refers to employees’ affective attachment to and identification with their work group, and their desire to maintain membership and invest effort in it (Meyer & Allen, 1997). In other words, commitment reflects a felt bond with “my team” and a willingness to remain connected and contribute.

Building on CBB theory, we propose that declines in both informal communication and formal knowledge sharing under remote conditions are a primary reason why commitment wanes. CBB theory is an evolutionary and motivational theory of social interaction that starts from the assumption that humans possess a fundamental need to belong and to maintain close, enduring relationships because such ties were adaptive for survival and reproduction. This need to belong motivates people to invest their limited “social energy” in interactions that help them feel connected and valued by others (Hall & Davis, 2017). Communication episodes are central to CBB theory because it is especially through everyday, low-stakes interactions that communication is converted into interpersonal bonding and, over time, a felt sense of belonging (Hall & Davis, 2017; Goldsmith & Baxter, 1996). Experimental and diary studies show that engaging in episodes such as meaningful talk, catching up, joking around, or expressing affection is associated with greater closeness, lower loneliness, and higher daily well-being compared to more superficial or purely transactional exchanges (Hall et al., 2025; Mehl et al., 2010). Thus, CBB provides a mechanism linking the content and quality of everyday talk to the satisfaction of belongingness needs and to relational outcomes.

When these micro-episodes of everyday talk become rarer or harder to initiate, the bond-building cycle weakens and attitudes like commitment may erode. In CBB terms, it is the frequency, ease, and socioemotional tone of regular exchanges that sustains belonging. When remote work thins these cues and rituals, the pathway from communication to bonding and belonging can be disrupted, yielding to lower team commitment (Leonardi et al., 2024).

We first propose that informal, nonwork-related interactions serve at least three commitment-relevant functions. First, they signal genuine care by conveying warmth, recognition, and regard (Fay & Kline, 2011). In line with CBB, these socioemotional signals strengthen interpersonal bonds among team members and can accumulate into trust and belonging, core antecedents of affective commitment (McGrath et al., 2017; Koch & Denner, 2022). Second, informal communication helps team members get to know one another not only for work purposes but also on a personal level, which fosters perspective taking and a shared interpretive context (e.g., common language, inside jokes, micro-rituals) (Hinds & Mortensen, 2005). This everyday sensemaking strengthens team-building processes and smooths later coordination because people can better anticipate one another’s preferences and constraints (Denner et al., 2025). As identification with one another grows, so does the willingness to remain connected and invest effort. Third, regular informal touchpoints create opportunities to offer and receive encouragement, empathy, and small favors. These micro-interactions cultivate mutual support and reciprocity norms, stabilizing cooperation and strengthening commitment over time (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

Knowledge sharing can likewise support commitment through complementary mechanisms. First, sharing help, tips, and know-how is a prosocial act that triggers norms of reciprocity (Ahmad & Karim, 2019). When members experience fair give-and-take, they feel valued and indebted to the relationship, which deepens trust and strengthens affective commitment (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). From a CBB perspective, such episodes are relationship-promoting because they both help coworkers accomplish their goals and reinforce a sense of mutual reliance and value within the team (Hall & Davis, 2017). Second, when coworkers exchange know-how, work feels more doable and less frustrating; this raises collective efficacy and satisfies the basic psychological need for competence, increasing motivation to remain invested in the team (Naim & Lenka, 2017). Third, repeated knowledge exchanges build a shared mental model and transactive memory system: people know “who knows what,” which reduces coordination costs and uncertainty. This clarity fosters psychological safety and identification with the group (Brandon & Hollingshead, 2004). Taken together, dependable human connection in everyday moments of informal and knowledge-sharing exchanges should strengthen the affective bond to the team.

However, when dispersion reduces the frequency and ease of both informal communication and knowledge sharing, these functions may weaken (Lütjens & Felfe, 2025; Viererbl et al., 2022; Keppler & Leonardi, 2023). Trust may accrue more slowly, small misunderstandings may linger, and the everyday signals of mutual care and inclusion may be less visible (Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999). Teams may still meet to coordinate, but without the surrounding fabric of casual contact and fluid know-how exchange, relationships can feel thinner and more transactional (Begemann et al., 2024). Over time, this erosion may translate into lower affective commitment, reflected in a diminished willingness to identify with, invest in, and remain connected to one’s colleagues.

Thus, we suggest that working remotely does not reduce commitment directly. Rather, dispersion acts upstream by altering situational affordances for routine, low-stakes interaction. Informal communication and knowledge sharing then transmit that effect to commitment. This mediational view clarifies why similarly dispersed teams can nonetheless differ in members’ attitudes. What matters for commitment is not distance per se, but whether day-to-day interaction still contains enough socioemotionally rich moments to sustain bonding.

H3.

Informal communication with team members mediates the relationship between working from home and commitment.

H4.

Knowledge sharing with team members mediates the relationship between working from home and commitment.

2.4. Moderating Role of Task Interdependence

Task interdependence is a core structural feature of team design and a key contextual variable for team communication processes (Marlow et al., 2018). It captures the extent to which members depend on one another to accomplish their work (e.g., Kiggundu, 1983; Wageman, 2014). In highly interdependent teams, members must regularly coordinate, integrate their contributions, and adjust to one another’s actions. In low-interdependence teams, they can largely complete their tasks independently, with fewer demands for joint problem solving or real-time coordination. As such, task interdependence affects not only the workflow but also the relational affordances of the work: how often people interact, what those episodes look like, and how strongly communication feeds into relationship building and bonding (G. S. van der Vegt & van de Vliert, 2005).

Building on CBB theory (Hall & Davis, 2017), we conceptualize task interdependence as a structural boundary condition that shapes how efficiently day-to-day communication episodes are converted into belonging and, in turn, commitment. We propose two distinct mechanisms through which it influences the links from informal communication and knowledge sharing to commitment.

Regarding informal communication, we expect that high task interdependence weakens its effect on team commitment. In such teams, the task structure already embeds many of the socioemotional ingredients that informal communication usually supplies. When members’ tasks are tightly linked, they must coordinate frequently, share responsibility for outcomes, and depend on one another’s timely contributions (Kiggundu, 1983; Wageman, 2014). These task demands foster frequent interaction, mutual awareness, and a sense of shared fate, which are associated with stronger affective bonds and higher team commitment (G. van der Vegt et al., 2000; Courtright et al., 2015). From a CBB perspective, part of the bonding function of communication is already built into the task structure, so the incremental effect of additional informal communication on commitment is weaker.

In loosely coupled work settings, by contrast, where members can accomplish most tasks alone, informal communication episodes may be one of the few occasions in which employees experience the team as a meaningful social unit. In such contexts, small talk and light relational check-ins are not simply pleasant extras; they are key, low-stakes moments through which people invest social energy, receive cues of inclusion and regard, and renew their sense of belonging to the team. Accordingly, we expect informal communication to be particularly consequential for commitment when task interdependence is low.

Taken together, we propose that additional informal communication has less marginal impact on commitment in highly interdependent teams, whereas in low-interdependence teams informal exchanges carry more weight because they transform otherwise transactional or solitary work into a shared social experience. Put differently, when the work itself does not connect people, small talk has to do more of the bonding work. When the work already ties people closely together, informal talk becomes a “nice-to-have” rather than a primary driver of commitment.

H5.

Task interdependence moderates the relationship between informal communication and commitment such that the positive relationship is weaker when task interdependence is high (vs. low).

In contrast to the informal communication path, we propose that task interdependence amplifies the effects of knowledge sharing. In highly interdependent teams, members’ ability to complete their own tasks depends heavily on others’ input (Kim & Yun, 2015; Wageman, 2014). Under such conditions, knowledge sharing becomes indispensable for avoiding errors, resolving dependencies, and achieving joint goals. When colleagues proactively share expertise in this context, they not only facilitate performance but also signal reliability, care, and investment in the collective outcome (Marlow et al., 2018). From a CBB perspective, these knowledge-sharing episodes are precisely the type of communicative events in which people invest their “social energy” and experience themselves as valued, needed, and embedded in a shared endeavor (Hall & Davis, 2017). They help the team “get things done” while simultaneously strengthening feelings of bonding and belonging. Therefore, in highly interdependent teams, day-to-day fluctuations in knowledge sharing should translate more strongly into fluctuations in daily commitment.

In teams with low task interdependence, however, employees can often achieve their goals with limited input from others. Knowledge sharing can still be beneficial, but it is less central to task success and less tightly coupled to the experience of mutual dependence (Cummings, 2004). In CBB terms, these episodes draw on less social energy and may be less diagnostic of whether one is truly needed or deeply embedded in the group (Hall & Davis, 2017). When colleagues share knowledge in this context, it may be appreciated but not experienced as essential for goal attainment or as a defining signal of collective engagement. As a result, day-to-day variation in knowledge sharing should exert a weaker effect on how committed employees feel to their team.

H6.

Task interdependence moderates the relationship between knowledge sharing and commitment such that the positive relationship is stronger when task interdependence is high (vs. low).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

We collaborated with a professional market research firm to recruit participants from a nationwide online panel in Germany. After receiving an invitation, interested employees first completed a baseline online survey that captured demographic information (e.g., age, gender, industry) and the moderator, task interdependence.

Participation was restricted to full-time employees who (a) worked a conventional daytime schedule (e.g., roughly 9:00–17:00; no shift work), (b) primarily performed computer-based tasks, (c) worked at least one day per week from home and at least one day per week in the office, and (d) belonged to a team with at least two other members. Starting in the workweek following the baseline survey, eligible participants received two short online surveys per workday for ten consecutive workdays, delivered via email links. The afternoon survey assessed that day’s work location and communication with team members, and the evening survey assessed commitment. To encourage compliance, we sent automated reminders for incomplete daily surveys. Participants received €1.60 per survey and a €20.00 bonus for completing all 20 daily surveys. All procedures followed standard ethical guidelines, and participants provided informed consent.

Data collection yielded 219 participants who completed on average 7.56 days, resulting in 1655 person-day observations. Our sample (51.6% men, 48.4% women) comprised employees from multiple German industries, including public administration (19.1%), IT and telecommunications (16.9%), banking and insurance (10.2%), and the metal and electrical industry (10.2%). Mean age was 44.1 years (SD = 11.3). Most participants worked two (28.8%) or three (37.8%) days per week from home and reported an average team size of 7.2 members (SD = 3.6). We screened for implausible response times and incomplete strings of daily surveys.

Because participation in the daily surveys was voluntary on each day, not all employees provided responses for every measurement occasion. Missing data therefore primarily reflected skipped day-level surveys rather than item nonresponse. We assumed that data were missing at random (MAR) conditional on the observed variables and handled missingness using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) as implemented in Mplus with the MLR estimator. This approach uses all available information and yields unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors under MAR, while avoiding listwise deletion of participants with at least one missing day (Baraldi & Enders, 2010).

3.2. Measures

Task Interdependence (Baseline Survey). Task interdependence was measured with three items from Campion et al. (1993) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = does not apply at all, 5 = fully applies). Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.73. A sample item was “I cannot accomplish my tasks without information or materials from other members of my team.”

Work Location (Afternoon Survey). Following prior research (Shao et al., 2021), participants were asked each day to report whether they had worked from home or in the office on that day (1 = at home, 0 = in the office). ICC was 0.26.

Informal communication (Afternoon Survey). Informal communication was assessed with a six-item measure. Items were adapted from a previously used measure of leader–follower informal communication (Lütjens & Felfe, 2025; Bruhn et al., 2025b) and rephrased to refer to team members. In earlier work, small talk and deep talk were modeled as separate subdimensions. Here we conceptualize them as two facets of a broader construct of informal, nonwork-related communication. A confirmatory factor analysis supported a one-factor model: all six items loaded strongly on a single latent factor (standardized λs = 0.77–0.84), and internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.92). In an alternative model distinguishing small talk and deep talk, the two factors were highly correlated (r = 0.75), indicating that they reflect a common underlying construct. For parsimony and because our theoretical interest lies in the overall amount of informal communication, we therefore used the combined scale in all analyses. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often). ICC was 0.50. A sample item is: “Today I talked with members of my team about general topics such as hobbies, interests, and weekend activities”.

Knowledge Sharing (Afternoon Survey). To capture knowledge sharing, we used four items based on the team communication behaviors measure from Hartner-Tiefenthaler et al. (2022). Items were adjusted to the daily context and measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often). Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.73. ICC was 0.49. A sample item was “Today, my team members and I kept each other posted”.

Team Commitment (End-of-Day Survey). Daily team commitment was measured with four items from Felfe et al. (2006) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = does not apply at all, 5 = fully applies). Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.90. ICC was 0.61. A sample item was “Today, I feel particularly emotionally connected to my team”.

3.3. Analytical Approach

Given the hierarchical data structure (days nested within persons), we estimated multilevel path models. Work location was coded 1 = working from home and 0 = working in the office. To isolate within-person day-to-day effects, all day-level predictor variables (work location, informal communication, and knowledge sharing) were group-mean centered, such that a value of 0 reflects a person’s own average across all measurement days. Thus, the within-person coefficients for work location represent differences between an employee’s own remote and office days, over and above between-person differences in how often they work from home.

At the between-person level, task interdependence was grand-mean centered. Consequently, the between-person main effects can be interpreted as effects at an average level of task interdependence, and the cross-level interaction terms can be interpreted as how the within-person relationships between work location, informal communication, knowledge sharing, and team commitment change for employees whose task interdependence is higher or lower than the sample mean.

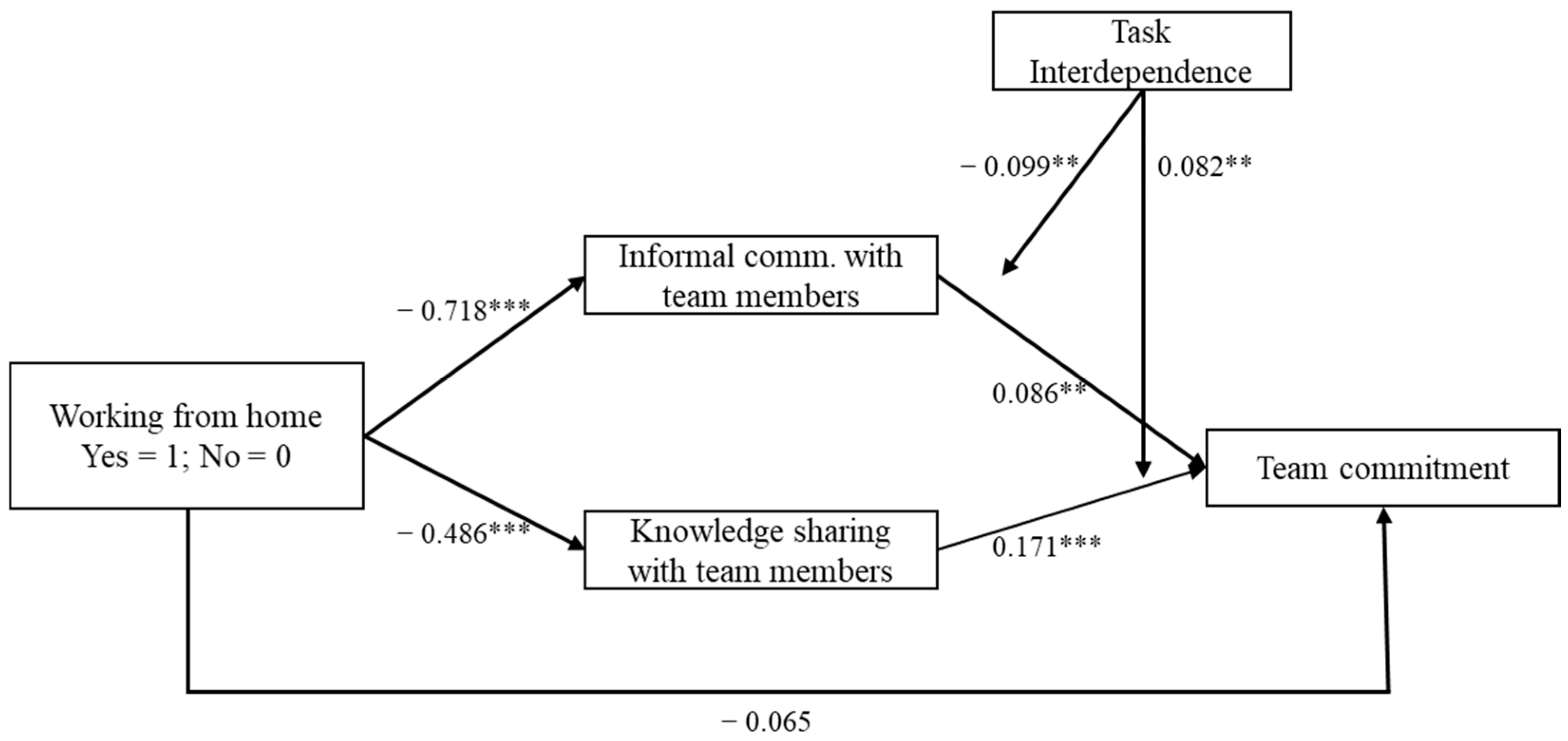

Models were estimated in Mplus 8.8 using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) with full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) for missing data. Figure 1 illustrates the modeled relationships, including the within-person indirect paths from work location via informal communication and knowledge sharing to team commitment and the cross-level moderation by task interdependence.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model and Results (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

To evaluate the construct validity of our day-level multi-item measures, we used multilevel confirmatory factor analysis. The three-factor CFA showed acceptable fit, χ2(74) = 1256.72, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.10 and fit the data better than any other plausible model, such as a model with informal communication and knowledge sharing forming a common factor: χ2(76) = 4115.77, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.68, TLI = 0.62, and RMSEA = 0.18.

In all multilevel models, we treat the unstandardized regression coefficients (b) as our primary effect size estimates and report them together with standard errors, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals.

4. Results

Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations appear in Table 1. Model estimates for hypothesis tests are demonstrated in Table 2 and displayed in Figure 1. Because work location is group-mean-centered (0 = working in the office, 1 = working from home), negative coefficients indicate lower values on remote workdays.

Table 1.

Full sample: Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations.

Table 2.

Results of the multilevel path model.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 postulated that on days employees work from home, they engage in less informal communication and knowledge sharing with their coworkers compared to days they work in the office. Results support both H1 and H2, demonstrating lower levels of informal communication (b = −0.72, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.82, −0.61]) and knowledge sharing (b = −0.49, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.61, −0.36]) on remote workdays.

Further, hypotheses 3 and 4 were supported. Regarding hypothesis 3, results demonstrate that at average task interdependence, daily informal communication is positively related to same-day team commitment (b = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.03, 0.14]). Also, the indirect effect of work location on commitment via informal communication is significant (b = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p = 0.003, 95% CI [−0.10, −0.02]). Regarding hypothesis 4, results show that at average task interdependence, daily knowledge sharing is positively related to same-day team commitment (b = 0.17, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.22]). In addition, the indirect effect of work location on team commitment via knowledge sharing was significant (b = −0.08, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.05]).

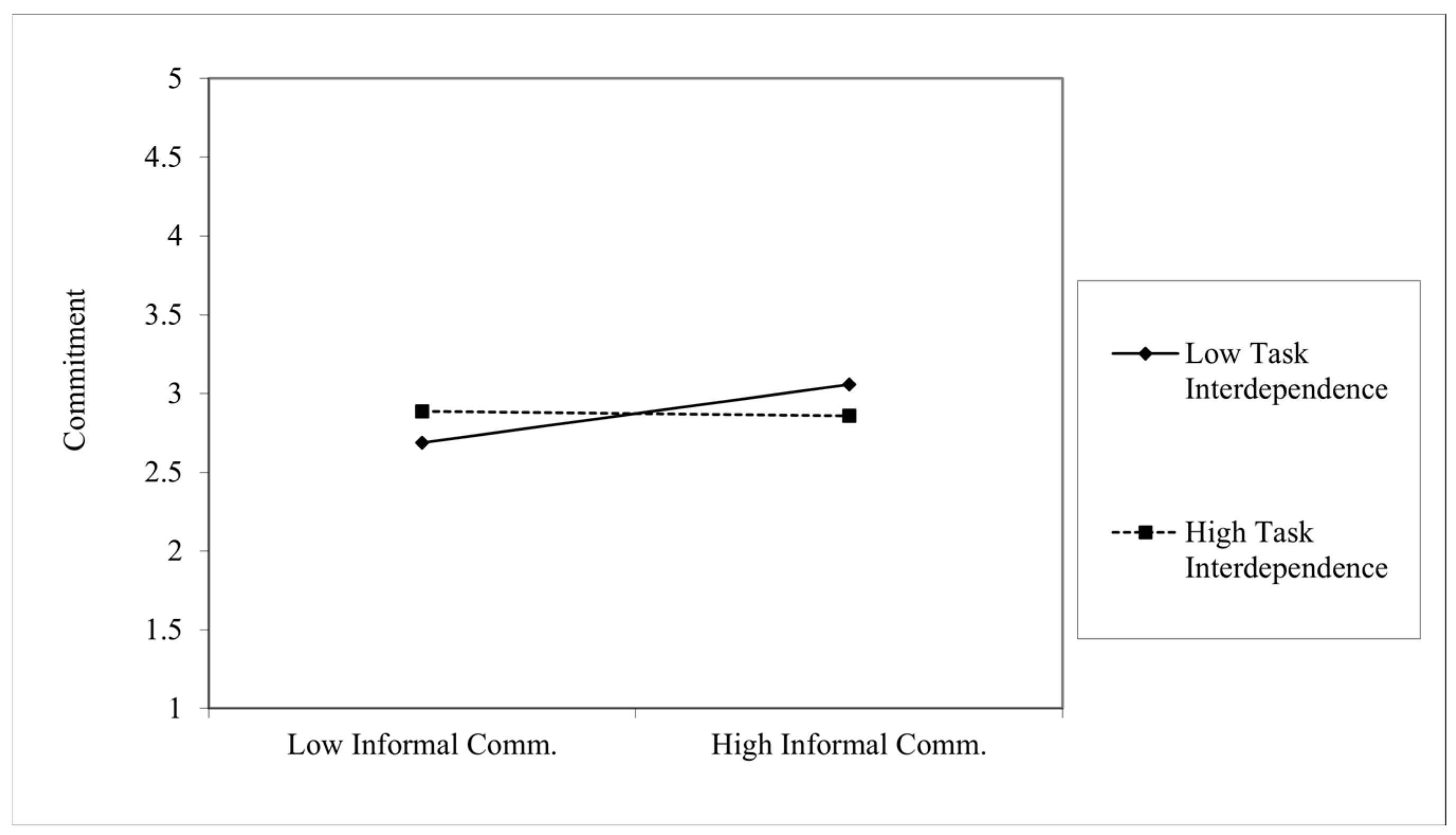

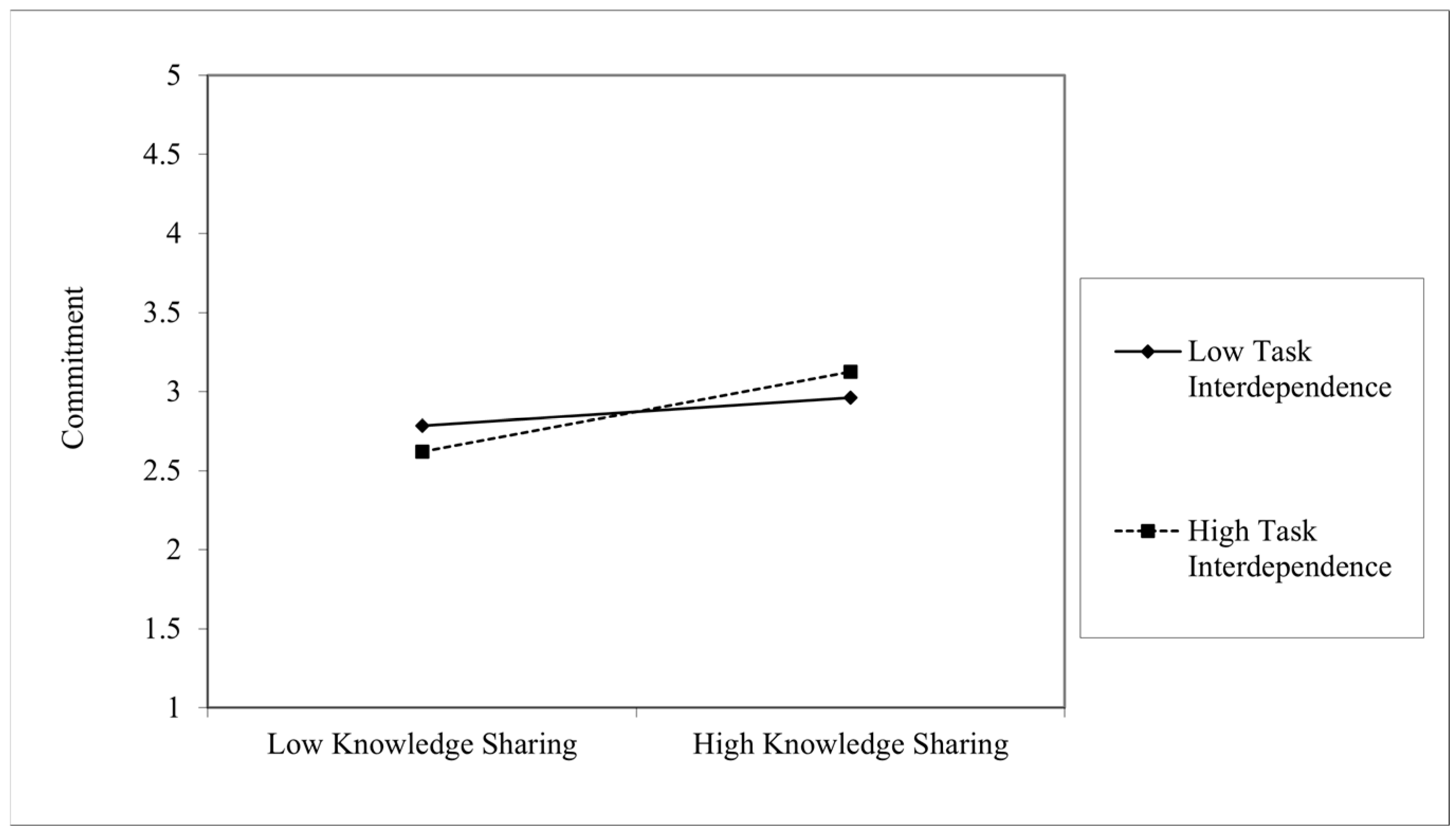

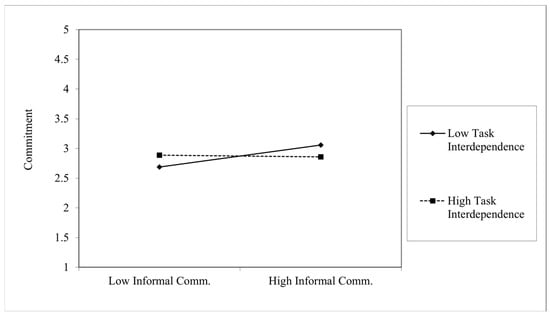

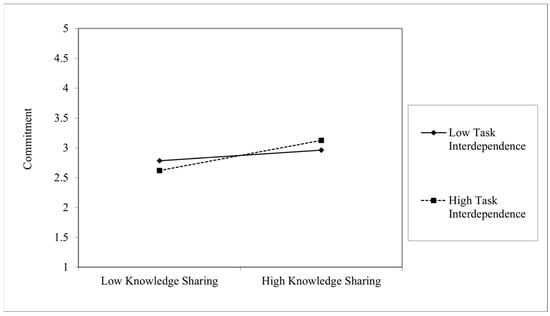

Finally, Hypotheses 5 and 6 proposed that task interdependence moderates both the link between informal communication and team commitment and the link between knowledge sharing and commitment. Consistent with our expectation, the positive relationship between informal communication and commitment is weaker when task interdependence is high (b = −0.10, SE = 0.03, p = 0.002, 95% CI [−0.16, −0.04]) while the positive relationship between knowledge sharing and commitment is stronger when task interdependence is high (b = 0.08, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.13]). Thus, hypotheses 5 and 6 are confirmed. The significant moderation effects are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect of task interdependence on the relationship between informal communication and commitment.

Figure 3.

Interaction effect of task interdependence on the relationship between knowledge sharing and commitment.

5. Discussion

In this study, we examined how informal communication and knowledge sharing relate to team commitment when employees work remotely versus co-located. Our findings show that on days when employees work from home, both informal communication and knowledge sharing with their coworkers are reduced. These attenuated day-level exchanges, in turn, are associated with lower team commitment. We also demonstrate the importance of task interdependence. When task interdependence is high, the positive effect of knowledge sharing on team commitment is strengthened, whereas informal communication becomes less critical for fostering team commitment. Taken together, our results suggest that working from different locations can hinder team commitment, but that communication and high task interdependence can partially buffer these negative effects.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our findings offer several implications for theorizing team communication and commitment in hybrid work environments. First, they provide process-level support for CBB theory in the context of hybrid teams and technology-mediated collaboration. Consistent with CBB’s core premise, we show that communication is critical for bonding with, and committing to, the team (Hall & Davis, 2017). We extend prior work by demonstrating that it is not only the frequency of communication that matters, but also its type (Gajendran & Joshi, 2012; van Zoonen et al., 2023; Shockley et al., 2021). Frequent exchanges of know-how and updates, as well as informal conversations, each contribute uniquely to a stronger affective bond with the team. This highlights informal communication and knowledge sharing as two complementary “conversion mechanisms” through which daily communication is transformed into bonding and a felt sense of belonging.

Second, our results underscore task interdependence as a core structural condition that shapes when and how communication translates into team commitment. In line with our theorizing, informal communication showed a stronger association with daily commitment in teams with low task interdependence, where the task design itself offers few opportunities for repeated interaction and shared fate. In such loosely coupled settings, informal exchanges fill a structural gap by providing occasions on which employees can experience the team as a meaningful social unit. By contrast, in highly interdependent teams, the work already embeds many of the socioemotional ingredients that foster commitment, so the incremental bonding effect of small talk is weaker. Much of the recent debate on remote work implicitly treats informal communication as uniformly beneficial, assuming that any reduction is harmful for relationships (Viererbl et al., 2022; Lütjens & Felfe, 2025; Bruhn et al., 2025b). Our multilevel findings support a more conditional view: informal, nonwork-related exchanges are positively related to daily commitment, but this association is stronger when task interdependence is low and weaker when it is high. Theoretically, this suggests that informal communication is best understood not as a universally potent resource, but as a structural “gap filler” that compensates for low bonding potential in the task design.

For knowledge sharing, we found a different pattern: its link with daily team commitment was stronger when task interdependence was high. In such teams, employees depend more on their team members to accomplish their work, so sharing information becomes more central and functions as a clearer signal that others are reliable, care about the team, and are invested in shared goals (G. S. van der Vegt et al., 2003). Our findings therefore add to theories of knowledge sharing and team communication by showing that sharing knowledge is not only instrumental for task accomplishment. It also carries relational weight, shaping how people feel about their team and signaling commitment to the collective (Lin, 2007).

Third, our study advances knowledge of remote work by shifting the focus from where employees work to how hybrid arrangements reconfigure the social infrastructure of daily interaction. Prior research on hybrid work and communication has largely examined between-person differences, treating work location and communication as relatively stable characteristics of jobs or teams (e.g., Gajendran & Joshi, 2012; Fuchs & Reichel, 2023). By contrast, our diary design shows that both work location and team communication fluctuate substantially from day to day, offering a more fine-grained picture of how hybrid work is actually lived. Modeling these processes at the within-person level also reduces concerns that stable between-person characteristics (e.g., team climate, personality, job role) confound the observed associations, because each employee effectively serves as their own control (Curran & Bauer, 2011).

Rather than treating hybrid work as uniformly beneficial or harmful for relationships, our results show that its effects on commitment depend on whether informal communication and knowledge sharing are preserved on remote days and on how interdependent the team’s tasks are. The same formal hybrid arrangement can thus lead to very different levels of bonding, depending on the team’s communication patterns and task structure. This suggests that theories of hybrid work should integrate both communication processes and features of team design and should do so at both between- and within-person levels, rather than relying on a simple office-versus-home perspective. More broadly, our findings indicate that understanding commitment in hybrid teams requires close attention to everyday communication episodes and to the broader structural conditions that shape how these moments are experienced and accumulate over time.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our research has several implications for managers, teams, and organizations working in hybrid environments. The central risk of hybrid work for team commitment does not stem from physical distance per se, but from how hybrid arrangements reshape day-to-day communication patterns. Accordingly, interventions should focus less on where people work and more on how they stay connected and communicate when they are dispersed.

First, organizations and leaders should deliberately create opportunities for regular informal exchanges and knowledge sharing. Examples include brief check-ins at the beginning of meetings, virtual coffee chats, informal virtual lunch breaks, or structured knowledge-sharing updates in shared channels (e.g., weekly “what I’m working on” posts; Tautz et al., 2025; Mabaso & Manuel, 2023). In hybrid teams, such practices are not “nice-to-have” add-ons but central mechanisms for maintaining a sense of belonging and shared understanding. Leaders can reinforce this by explicitly framing small talk and “keeping each other posted” as legitimate parts of work rather than distractions.

Second, managers should clarify communication norms and expectations for hybrid collaboration. This includes specifying availability windows, preferred channels for different purposes (e.g., chat for quick questions, video calls for complex topics, asynchronous documents for updates), and reasonable response times (Shockley et al., 2021; Dhawan & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2018). Ideally, these norms are developed jointly with team members rather than imposed top-down, for example, through a team workshop or retrospective. Co-creating “team communication agreements” can increase buy-in and ensure that rules fit both the task and the team’s preferences.

Third, our findings show that task interdependence shapes how communication translates into commitment, which has implications for coordination design rather than for structurally increasing interdependence itself. In teams with lower task interdependence, employees can often work largely on their own. Here, informal communication becomes particularly important because it creates a sense of social connection that the task structure does not automatically provide. In such teams, managers might prioritize lightweight social routines (e.g., brief personal check-ins at the start of meetings, rotating “coffee pairings”) and occasional in-person or virtual team events to sustain cohesion, especially on remote days (Tautz et al., 2025).

In highly interdependent teams, by contrast, coordination and knowledge exchange are already embedded in the work itself. For these teams, it is particularly important to design clear knowledge-sharing and coordination routines, such as regular stand-up meetings, shared task boards, or structured handover notes. Rather than trying to increase task interdependence further—which may create unnecessary workflow complexity and coordination costs—managers can focus on improving the quality and visibility of existing interdependencies: clarifying who depends on whose input, making progress transparent, and ensuring that critical information is easily accessible to all relevant members. In this way, knowledge sharing can both support effective coordination and more strongly foster team commitment.

Finally, organizations can support managers and teams by providing guidance and tools for digital communication. This may include training on leading hybrid meetings, selecting and using digital collaboration tools, and facilitating the creation of team-level communication agreements. HR and leadership development functions can also help teams periodically reflect on their hybrid communication practices (e.g., via pulse surveys or retrospectives) and adjust them as tasks, structures, or hybrid arrangements evolve.

Taken together, our results suggest that managers should treat informal communication and knowledge sharing as key “levers” of commitment in hybrid teams. Rather than redesigning tasks to increase structural interdependence, it is often more feasible and less risky to deliberately shape communication norms, routines, and tools so that employees remain socially connected with their team members and well-informed—regardless of whether they are working from home or in the office.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Even though our research provides important theoretical and practical contributions to understand team communication and commitment in hybrid work, our findings need to be interpreted in light of several limitations.

First, all focal variables were assessed via self-reports from the same source, which raises the risk of common method bias and same-source inflation (Podsakoff et al., 2024). To mitigate this risk, we included a relatively objective, low-inference predictor—daily work location (home vs. office)—in our diary design, as recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2024). In addition, we implemented several procedural remedies to reduce common method variance, including temporal separation of predictors and outcomes (afternoon vs. evening surveys), simplifying survey language, clarifying complex constructs, avoiding double-barreled questions, and varying response formats. To enhance participant engagement and minimize survey fatigue, we also selected a relatable topic (team communication and commitment) and kept the daily surveys brief. Nonetheless, as we cannot fully rule out common method bias and same-source inflation, future research should incorporate behavioral and observational data, such as digital communication logs, experience sampling of concrete interaction episodes, sociometric data, or peer and supervisor reports of communication and commitment, to better triangulate the investigated processes (Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2025).

Second, although our daily diary design temporally separated predictors and outcomes by assessing informal communication and knowledge sharing in the afternoon and team commitment in the evening, the data remain correlational. Thus, we cannot make strong causal claims. Our models are consistent with the idea that daily communication shapes same-day commitment, but reverse or reciprocal effects (e.g., feeling more committed leading to more informal interaction) and the influence of unmeasured third variables (such as stable team climate or prior-day commitment) cannot be ruled out. Future research employing longitudinal cross-lagged panel models and experimental manipulations of communication opportunities in hybrid teams would be valuable to more rigorously establish causal direction.

Third, because we aimed to isolate core mechanisms of remote work, communication, and commitment, we necessarily used simplified measures of work location and communication. Work location was assessed as a binary distinction between working from home versus in the office, which does not capture other relevant hybrid constellations, such as working from third places or coworking spaces, or mixed-location days (e.g., splitting time between home and office within a single day). Similarly, we focused on the frequency of informal communication and knowledge sharing without differentiating between communication channels (e.g., chat vs. video vs. face-to-face), types of informal talk (e.g., light small talk vs. more personal deep talk), or distinct forms of knowledge sharing (e.g., unsolicited help, troubleshooting, strategic updates; Daft & Lengel, 1986; Lütjens & Felfe, 2025; Bruhn et al., 2025a). Future research could refine these constructs by examining how specific content, media, and temporal patterns of communication differentially shape commitment in hybrid teams.

Fourth, our sample consists of German employees recruited via an online panel, working in a range of industries but within a single national and cultural context. This single-country design limits the generalizability of our findings. Hybrid work practices, norms for informal interaction, and expectations about knowledge sharing may differ across countries, sectors, and organizational cultures. For example, depending on the cultural context, some organizations may institutionalize virtual social rituals or formalize knowledge-sharing routines more strongly than others (Ardichvili et al., 2006). Future studies should therefore examine whether our pattern of findings generalizes to other countries, cultural contexts, occupational groups, and organizational forms, and explore how institutionalized communication norms or HR policies shape the communication–commitment link in hybrid teams.

Finally, while our study examined task interdependence as a key contextual moderator, future research could place even stronger emphasis on how different forms and degrees of team interdependence shape the communication–commitment link in hybrid work. When team members’ tasks are tightly coupled, hybrid arrangements may amplify coordination frictions, making informal communication (e.g., quick check-ins, spontaneous problem solving, relational “glue”) particularly important for maintaining shared understanding and a sense of belonging. In contrast, when interdependence is low and work can be completed more independently, informal communication may be less critical for sustaining commitment and may even be perceived as interruptive. Building on this logic, future studies could differentiate more precisely between workflow interdependence (e.g., sequential vs. reciprocal dependencies), goal/outcome interdependence, and temporal interdependence, and test whether each type creates distinct communication needs and therefore different pathways to commitment in hybrid teams. Such work would help clarify when informal interaction and knowledge sharing are most consequential under conditions of physical dispersion.

6. Conclusions

In sum, our study shows that hybrid work arrangements can subtly erode day-to-day commitment to the team by thinning out the very communication episodes through which belonging is typically built. On remote workdays, employees reported less informal communication and less knowledge sharing with coworkers, and these reduced exchanges were associated with lower same-day team commitment. At the same time, we demonstrate that these communication processes do not operate in a vacuum. Task interdependence fundamentally shapes when and how they matter. In loosely coupled teams, informal conversations are especially important because they provide one of the few opportunities to experience the team as a meaningful social unit. In highly interdependent teams, in contrast, knowledge sharing carries greater relational weight, as it signals mutual reliance, support, and shared investment in joint outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and J.F.; methodology, D.L. and J.F.; formal analysis, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L. and J.F.; visualization, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the project Digital Leadership and Health, funded by dtec.bw—Digitalization and Technology Research Center of the Bundeswehr. dtec.bw is funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

For our study, formal ethics approval was not required because no identifiable or sensitive personal data were collected, and participation involved minimal risk. The daily diary surveys focused on nonsensitive work-related perceptions (e.g., work location, communication patterns, and daily commitment) and did not address any topics that could reasonably cause psychological, social, or professional harm. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, and participants could withdraw at any time without penalty.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, F., & Karim, M. (2019). Impacts of knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(3), 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, C. G., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Dolls, M., & Zarate, P. (2022). Working from home around the world. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2022(2), 281–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habaibeh, A., Watkins, M., Waried, K., & Javareshk, M. B. (2021). Challenges and opportunities of remotely working from home during COVID-19 pandemic. Global Transitions, 3, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardichvili, A., Maurer, M., Li, W., Wentling, T., & Stuedemann, R. (2006). Cultural influences on knowledge sharing through online communities of practice. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, A. N., & Enders, C. K. (2010). An introduction to modern missing data analyses. Journal of School Psychology, 48(1), 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, V., Handke, L., & Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2024). Enabling and constraining factors of remote informal communication: A socio-technical systems perspective. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(5), zmae008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, D. P., & Hollingshead, A. B. (2004). Transactive memory systems in organizations: Matching tasks, expertise, and people. Organization Science, 15(6), 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, K., Krick, A., & Felfe, J. (2025a). Responding to followers’ warning signals. Applied Psychology = Psychologie Appliquee, 74(6), e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, K., Tautz, D., & Felfe, J. (2025b). The role of leader-employee communication in Health-oriented Leadership. Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie (GIO), 56(3), 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., & Higgs, A. C. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46(4), 823–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinyuku, C., & Qutieshat, A. (2025). The impact of remote work on building effective teams: Exploring the challenges of fostering team cohesion in remote work environments, A brief review of literature. International Journal of Advanced Business Studies, 4(2), 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, S. H., Thurgood, G. R., Stewart, G. L., & Pierotti, A. J. (2015). Structural interdependence in teams: An integrative framework and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1825–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. N. (2004). Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Management Science, 50(3), 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 583–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32(5), 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, N., Koch, T., Viererbl, B., & Ernst, A. (2025). Feeling connected and informed through informal communication: A quantitative survey on the perceived functions of informal communication in organizations. Journal of Communication Management, 29(1), 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, E., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2018, February 27). How to collaborate effectively if your team is remote. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/02/how-to-collaborate-effectively-if-your-team-is-remote (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Fay, M. J., & Kline, S. L. (2011). Coworker relationships and informal communication in high-intensity telecommuting. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 39(2), 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felfe, J., Schmook, R., & Six, B. (2006). Die bedeutung kultureller wertorientierungen für das commitment gegenüber der organisation, dem vorgesetzten, der arbeitsgruppe und der eigenen karriere [The importance of cultural values for commitment to the organization, superiors, work group, and one’s own career]. Zeitschrift für Personalpsychologie, 5(3), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Jordán, P. (2022). Virtual teams are here to stay: How personality traits, virtuality and leader gender impact trust in the leader and team commitment. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(2), 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C., & Reichel, A. (2023). Effective communication for relational coordination in remote work: How job characteristics and HR practices shape user–technology interactions. Human Resource Management, 62(4), 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R. S., & Joshi, A. (2012). Innovation in globally distributed teams: The role of LMX, communication frequency, and member influence on team decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajendran, R. S., Ponnapalli, A. R., Wang, C., & Javalagi, A. A. (2024). A dual pathway model of remote work intensity: A meta-analysis of its simultaneous positive and negative effects. Personnel Psychology, 77(4), 1351–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, D. J., & Baxter, L. A. (1996). Constituting relationships in talk a taxonomy of speech events in social and personal relationships. Human Communication Research, 23(1), 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk, M., Mariniello, M., Nurski, L., & Schraepen, T. (2021). Blending the physical and virtual: A hybrid model for the future of work. Bruegel Policy Contribution 14/2021. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/251067 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Hall, J. A., & Davis, D. C. (2017). Proposing the communicate bond belong theory: Evolutionary intersections with episodic interpersonal communication. Communication Theory, 27(1), 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. A., Holmstrom, A. J., Pennington, N., Perrault, E. K., & Totzkay, D. (2025). Quality conversation can increase daily well-being. Communication Research, 52(3), 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handke, L., Klonek, F., O’neill, T. A., & Kerschreiter, R. (2022). Unpacking the role of feedback in virtual team effectiveness. Small Group Research, 53(1), 41–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handke, L., Klonek, F. E., Parker, S. K., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Interactive effects of team virtuality and work design on team functioning. Small Group Research, 51(1), 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartner-Tiefenthaler, M., Loerinc, I., Hodzic, S., & Kubicek, B. (2022). Development and validation of a scale to measure team communication behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 961732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P. J., & Mortensen, M. (2005). Understanding conflict in geographically distributed teams: The moderating effects of shared identity, shared context, and spontaneous communication. Organization Science, 16(3), 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J., & Marra, M. (2004). Relational practice in the workplace: Women’s talk or gendered discourse? Language in Society, 33(03), 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1999). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science, 10(6), 791–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, S. M., & Leonardi, P. M. (2023). Building relational confidence in remote and hybrid work arrangements: Novel ways to use digital technologies to foster knowledge sharing. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 28(4), zmad020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiggundu, M. N. (1983). Task interdependence and job design: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 31(2), 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. L., & Yun, S. (2015). The effect of coworker knowledge sharing on performance and its boundary conditions: An interactional perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T., & Denner, N. (2022). Informal communication in organizations: Work time wasted at the water-cooler or crucial exchange among co-workers? Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 27(3), 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R. E., Fish, R. S., Root, R. W., Chalfonte, B. L., & Spacapan, S. (1990). Informal communication in organizations: Form, function, and technology. In S. Oskamp, & S. Spacapan (Eds.), Human reactions to technology: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology (pp. 145–199). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, B., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Haag, M. (2021). Working from home during COVID-19: Doing and managing technology-enabled social interaction with colleagues at a distance. Information Systems Frontiers: A Journal of Research and Innovation, 25(4), 1333–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2025). Dynamic interpersonal processes at work: Taking social interactions seriously. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 12(1), 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P. M., Parker, S. H., & Shen, R. (2024). How remote work changes the world of work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P. M., & Treem, J. W. (2020). Behavioral visibility: A new paradigm for organization studies in the age of digitization, digitalization, and datafication. Organization Studies, 41(12), 1601–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. (2007). To share or not to share: Modeling tacit knowledge sharing, its mediators and antecedents. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(4), 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütjens, D., & Felfe, J. (2025). Casual yet crucial: How informal nonwork-related communication shapes transformational leadership in hybrid work environments. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabaso, C. M., & Manuel, N. (2023). Performance management practices in remote and hybrid work environments: An exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 50, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S. L., Lacerenza, C. N., Paoletti, J., Burke, C. S., & Salas, E. (2018). Does team communication represent a one-size-fits-all approach?: A meta-analysis of team communication and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, E., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Garrosa, E., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., & Cheung, G. W. (2017). Rested, friendly, and engaged: The role of daily positive collegial interactions at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(8), 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhail, R., Chan, X. W., May, R., & Wilkinson, A. (2024). Post-COVID remote working and its impact on people, productivity, and the planet: An exploratory scoping review. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(1), 154–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, M. R., Vazire, S., Holleran, S. E., & Clark, C. S. (2010). Eavesdropping on happiness: Well-being is related to having less small talk and more substantive conversations. Psychological Science, 21(4), 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, H., Salamzadeh, Y., & Ramkissoon, H. (2025). Critical success factors of global virtual teams (GVTs): A study based on UK information technology experts’ opinion. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 31(3/4), 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, J. R., Rosado-Solomon, E. H., Downes, P. E., & Gabriel, A. S. (2021). Office chitchat as a social ritual: The uplifting yet distracting effects of daily small talk at work. Academy of Management Journal, 64(5), 1445–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J., & Allen, N. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naim, M. F., & Lenka, U. (2017). Linking knowledge sharing, competency development, and affective commitment: Evidence from Indian Gen Y employees. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(4), 885–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, B. A., & Whittaker, S. (2002). The place of face-to-face communication in distributed work. In P. Hinds, & S. Kiesler (Eds.), Distributed work (pp. 83–110). Boston Review. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-17012-004 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y., Fang, Y., Wang, M., Chang, C., & Wang, L. (2021). Making daily decisions to work from home or to work in the office: The impacts of daily work- and COVID-related stressors on next-day work location. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(6), 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, K. M., Allen, T. D., Dodd, H., & Waiwood, A. M. (2021). Remote worker communication during COVID-19: The role of quantity, quality, and supervisor expectation-setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(10), 1466–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, P. (2008). Organizing relationships: Traditional and emerging perspectives on workplace relationships. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, F., & Denner, N. (2025). Illuminating informal communication in organizations—A scoping review. Journal of Communication Management, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautz, D., Krick, A., & Felfe, J. (2025). Informal communication as a leadership tool. In Handbook of leadership (pp. 115–128). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tautz, D., Schübbe, K., & Felfe, J. (2022). Working from home and its challenges for transformational and health-oriented leadership. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1017316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, F., González-Romá, V., & Zappalà, S. (2025). The influence of working from home vs. working at the office on job performance in a hybrid work arrangement: A diary study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 40(2), 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vegt, G., Emans, B., & van de Vliert, E. (2000). Team members’ affective responses to patterns of intragroup interdependence and job complexity. Journal of Management, 26(4), 633–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vegt, G. S., & van de Vliert, E. (2005). Effects of perceived skill dissimilarity and task interdependence on helping in work teams. Journal of Management, 31(1), 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vegt, G. S., van de Vliert, E., & Oosterhof, A. (2003). Informational dissimilarity and organizational citizenship behavior: The role of intrateam interdependence and team identification. The Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, W., & Sivunen, A. E. (2022). The impact of remote work and mediated communication frequency on isolation and psychological distress. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(4), 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, W., Treem, J. W., & Sivunen, A. E. (2023). Staying connected and feeling less exhausted: The autonomy benefits of after-hour connectivity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96(2), 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen, M., & Vanharanta, O. (2024). True nature of hybrid work. Frontiers in Organizational Psychology, 2, 1448894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viererbl, B., Denner, N., & Koch, T. (2022). “You don’t meet anybody when walking from the living room to the kitchen”: Informal communication during remote work. Journal of Communication Management, 26(3), 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageman, R. (2014). The meaning of interdependence. In Groups at work (pp. 197–217). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology = Psychologie Appliquee, 70(1), 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wombacher, J., & Felfe, J. (2017). The interplay of team and organizational commitment in motivating employees’ interteam conflict handling. Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1554–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.