Abstract

This mixed-methods study investigates the strategic management of digital transformation in Bulgarian schools by analysing principals’ self-reported leadership practices and styles. Using data from a nationally representative sample (N = 349) gathered through the SELFIE tool, complemented by 30 in-depth interviews, the research examines how school leaders understand and enact their roles as digital leaders within a context of fragmented policies and uneven digital capacity. Quantitative results reveal a central paradox: although 89.7% of principals claim to actively support teachers’ digital innovation, only about half report having a formalised digital strategy. This imbalance between strong operational support and weak institutionalisation reflects the dominant approach to school digitalisation in Bulgaria. Qualitative cluster analysis identifies three leadership profiles: (1) a strategic–collaborative profile, characterised by long-term planning, partnerships, and data-driven decisions; (2) a supportive–collaborative profile focused on teacher communities and context-specific professional development but lacking strategic vision; and (3) a balanced–pragmatic profile oriented toward measurable improvements and adaptive responses. Triangulation with national assessment data shows that leadership styles align with institutional contexts: high-performing schools tend to apply strategic–collaborative leadership, while lower-performing schools adopt pragmatic, adaptive approaches. The study argues that digital transformation requires context-sensitive frameworks recognising multiple developmental trajectories, highlighting the need for differentiated policies that support strategic institutionalisation of existing digital innovations while addressing structural inequalities.

1. Introduction

Successful digital transformation in education requires a systemic approach that goes beyond the introduction of specific technologies or platforms and is grounded in their strategic use to reshape managerial roles, organisational models, and pedagogical practices. A key condition for advancing this process is the development of school capacity that integrates leadership, reflective pedagogical approaches, and digital infrastructure to ensure sustainable educational outcomes. In an increasingly digitalised learning environment, school leaders must develop the ability to navigate rapidly evolving technological landscapes so that technologies become drivers of school development and innovation (Timotheou et al., 2023; Okunlola & Naicker, 2024). European policy frameworks emphasise digital competence and digital maturity as multidimensional constructs that address not only technical provision but also strategic planning, pedagogical innovation, and cultural change within school organisations (Kampylis et al., 2015; Conrads et al., 2017). Initiatives such as the eLearning Action Plan (2001) aim to provide comprehensive support for the digitalisation of education, highlighting the importance of teacher training, technology integration in teaching and learning, the development of appropriate digital content, and the promotion of partnerships among stakeholders (European Commission, 2001). Subsequently, the emphasis on technology integration and the development of digital competences is strengthened in policy documents such as Rethinking Education (European Commission, 2012) and the Survey of Schools: ICT in Education (2013) (European Commission, 2013). This trajectory culminates in the Digital Education Action Plan (2021–2027), which articulates a vision for a highly effective digital education ecosystem and the development of advanced digital skills from an early age (European Commission, 2020).

Within this broader context, the Bulgarian education system follows overall European trends while displaying several characteristics of its own. National policy documents—the National Strategy for Introducing ICT in Schools (2005–2008), the Strategy for the Effective Application of ICT in Education and Science (2014–2020), and the Strategic Framework for Education, Training and Learning (2021–2030)—outline a shift from infrastructure-focused provision towards a more visionary approach to digital transformation (Mizova & Peytcheva-Forsyth, 2024). Recent years have seen investments in STEM centres, digital libraries, cloud-based platforms, teacher competence development, and innovative school initiatives. Nevertheless, persistent challenges remain, including regional disparities in resources, limited access to high-quality professional development, and a lack of systematic mechanisms for assessing digital maturity. Despite considerable progress in policy formulation and increasing acknowledgment of the pivotal role played by school principals, there remains a notable paucity of empirical research examining how digital leadership is conceptualised and enacted in practice—especially in contexts marked by fragmented policy implementation and disparities in institutional capacity. While normative instruments such as the DigCompOrg framework (Kampylis et al., 2015) delineate the structural components of digitally mature organisations, current understanding of the variety of leadership strategies that arise in response to divergent school contexts, resource distributions, and performance levels is insufficient. Much of the extant literature presumes linear pathways to digital maturity; however, there is limited insight into how principals in diverse institutional settings address the challenges associated with balancing operational support for innovation and the strategic institutionalisation of digital practices.

School principals play a key role in the transition towards digital maturity, acting as mediators between policy priorities and school-level practice and combining the functions of strategic visionaries, administrators, and leaders of pedagogical change (Fullan & Boyle, 2014; Caneva & Pulfrey, 2023). International research shows that principals’ digital leadership is one of the strongest correlates of sustainable technological innovation and the development of a culture of learning (Anderson & Dexter, 2005; Castaño Muñoz et al., 2023). In the Bulgarian context, digital leadership is enacted within conditions of fragmented policies, uneven digital capacity, and pronounced local and regional disparities. A nuanced understanding of how principals navigate these multifaceted conditions—balancing the immediate demands of operational support for pedagogical innovation with the imperatives of sustained, long-term strategic planning—constitutes a critical prerequisite for advancing sustainable digital transformation within educational systems.

This study seeks to address these research gaps by investigating how school principals in Bulgaria conceptualise and enact digital leadership within an environment characterised by fragmented policy landscapes, uneven digital capacity, and pronounced socio-economic disparities. Situated within the framework of the SUMMIT project (Sofia University Marking Momentum for Innovation and Technological Transfer, No. BG-RRP-2.004-0008), and employing the DigCompOrg framework, the present analysis integrates quantitative self-assessment data with qualitative examination of leadership narratives to address two interrelated research questions:

- RQ1

- How do school principals assess key aspects of the strategic management of digitalisation within their organisations?

- RQ2

- What profiles of digital leadership emerge from principals’ declared leadership styles and managerial practices, and what are the defining characteristics of these profiles?

Drawing on a combination of nationally representative survey data (N = 349) and in-depth interviews (N = 30), this study advances the understanding of digital leadership not as a uniform developmental trajectory, but rather as a context-sensitive configuration of practices shaped by institutional capacity, resource availability, and performance stability. The findings underscore the need for differentiated policy approaches that accommodate multiple pathways toward digital maturity, instead of imposing standardised models.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Digital Leadership and Managerial Strategies for Developing Organisational Maturity

In the school context, strategic management refers to principals’ systematic planning, resource allocation, and decision-making processes aimed at aligning digital initiatives with institutional priorities and pedagogical objectives (Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010). Unlike administrative management, which addresses routine administrative tasks, strategic management involves setting a long-term vision, engaging stakeholders, monitoring implementation, and responding adaptively to changing conditions. In the context of digital transformation, this extends beyond the acquisition of technological resources to include building organisational cultures, supporting professional learning, and developing data-informed practices that sustain pedagogical innovation (DigCompOrg framework; Kampylis et al., 2015).

The concept of digital leadership emerges at the intersection of leadership theory and the technological transformation of education—evolving from ICT/IT leadership, focused primarily on resource and infrastructure management (Yee, 2000), towards e-leadership and digital leadership, which emphasise cultural and pedagogical change within schools (Chamakiotis & Panteli, 2011; Fisk, 2002; Sağbaş & Erdoğan, 2022). In this context, e-leadership is understood as the ability to exert influence within digitally mediated environments and to employ management systems for data exchange and e-communication in order to support more informed decision-making and more effective stakeholder interaction (Gurr, 2004). Digital leadership encompasses an understanding of technology and its meaningful integration across key institutional processes—management, teaching, learning, assessment, and community engagement—while simultaneously fostering digital competence among teachers, students, and parents (ISTE, 2009; Conrads et al., 2017). It involves a transformation, ethical commitments to equitable access, and the promotion of a culture of innovation and collaboration (Carey, 2011; Fullan, 2013).

Within the model of digitally mature educational organisations reflected in the DigCompOrg framework, leadership is a central mechanism for sustainable capacity-building: strategic resource management, integrated pedagogical approaches, and the active involvement of all stakeholders. It is conceptualised as a multidimensional process of managing change, encompassing vision, professional development, ethical practice, and the cultivation of a lifelong learning culture (Kampylis et al., 2015). Having outlined digital leadership as a multidimensional construct oriented towards capacity-building, the subsequent section traces the evolution of this concept by reviewing key theoretical frameworks that operationalise its constituent dimensions for application at the school level.

2.2. Evolution of the Concept and Key Frameworks

The development of the notion of digital leadership reflects a shift from an instrumental focus towards organisational and pedagogical transformation: initially centred on infrastructure provision and technical support (European Commission, 2001) and on ICT/IT leadership concerned with resource management and operational decision-making (Yee, 2000; Hollingsworth & Mrazek, 2004; in Jameson, 2013); subsequently evolving into e-leadership, which emphasises social influence within digitally mediated environments (Avolio et al., 2000; Chamakiotis & Panteli, 2011), and into digital leadership, which aims at rethinking school culture and developing innovation ecosystems (Fisk, 2002; Sağbaş & Erdoğan, 2022).

An integrative reference point in this evolution is the DigCompOrg framework (Kampylis et al., 2015), which defines seven areas: leadership and governance, teaching and learning practices, professional development, assessment, content and curricula, collaboration, and infrastructure. It forms the conceptual foundation of the SELFIE tool, implemented in over 7500 schools across Europe to support 360-degree institutional self-assessment (Bocconi & Lightfoot, 2021). Description of SELFIE instrument is presented in Section 3.3.2. Parallel to this, the ISTE NETS-A standards (2009/2018) outline five domains—visionary leadership, digital-age culture, professional practice, systemic improvement, and digital citizenship—used both for (self-)evaluation of leadership practice and for designing professional development programmes (ISTE, 2009, 2018; Arafeh, 2015; Metcalf & LaFrance, 2013; Esplin et al., 2018).

Other key conceptual foundations include the learning organisation model (Senge, 1990), which focuses on domains such as shared vision, personal mastery, team learning, mental models, and systems thinking, as well as the Unified Model of Effective Leader Practices (Hitt & Tucker, 2016). According to this model, principals’ leadership is the second most influential factor in student learning outcomes after teaching quality—primarily through the mechanisms of vision, culture, and school conditions that shape the instructional environment. The model identifies five domains (vision and goals; improvement of instruction; professional capacity; supportive organisation; and community engagement) and 28 specific practices that can be strengthened through targeted preparation (Hitt & Tucker, 2016).

Taken together, these frameworks converge on several core principles central to the present study. First, they conceptualise digital leadership as extending beyond technical competence to include strategic vision, pedagogical transformation, and active stakeholder engagement. Second, they underscore the pivotal role of principals in cultivating organisational cultures that foster innovation and continuous learning. Third, they acknowledge that digital maturity is achieved through iterative, context-dependent processes rather than through uniform linear trajectories. The DigCompOrg framework, which underpins the SELFIE tool employed in this study, offers a particularly valuable perspective for analysing principals’ self-reported practices, as it synthesises these dimensions into a comprehensive model of organisational digital capacity. The following section explores how these principles are operationalised by principals through specific leadership styles and managerial practices.

2.3. Principal Leadership for Developing School Digital Capacity: Styles and Effective Practices

Before examining specific leadership approaches, it is important to clarify the analytical distinction employed in this study. Managerial practices refer to the specific, observable actions that school leaders take to enhance digital capacity, such as organising professional development, supporting innovation, and using data to inform decision-making. Leadership style, on the other hand, refers to the dominant logic or strategic orientation that shapes how these practices are selected, combined, and enacted in response to institutional contexts. Conceptually, leadership style represents the more abstract pattern within which individual practices function as instrumental manifestations. This distinction enables the study to identify not only what principals do, but also how and why they do it, revealing the strategic coherence, or lack thereof, underlying their approaches to digital transformation.

The school principal is a central figure in digital transformation, with leadership styles and practices shaping the level of digital maturity within the school. Research indicates that successful principals combine approaches in ways that respond to contextual realities and staff needs (Maulana et al., 2024; Tømte, 2024). While teachers are the primary implementers of digital practices within classrooms, principals’ leadership determines the strategic direction, resource allocation, and organisational conditions that enable or constrain teachers’ capacity for technology integration. Understanding principals’ conceptions of their leadership role therefore requires careful attention to how they support and shape teachers’ professional agency within the broader institutional context.

Transforming leadership (Bass, 1985; Burns, 2012) is a dominant model associated with developing a vision, motivating teachers, and stimulating innovation through intellectual stimulation and individualised support. This is a key style that motivates and inspires staff, creates a sense of purpose and meaning, and unites students, teachers, and school personnel around a shared commitment to high academic achievement. It involves individual consideration, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, and personalised influence. Transformational principals are found to be more likely to promote technology integration and to support teachers’ professional development (Afshari et al., 2009).

Authentic leadership builds on ideas from transformational, servant, and ethical leadership, emphasising strong self-reflection, value-driven behaviour, and an awareness of the leader’s own identity and principles. Studies highlight that this leadership style fosters environments of trust, engagement, and ethical practice that are conducive to sustainable innovation and a positive school culture (Carey, 2011; Fullan, 2014).

Servant leadership (Greenleaf, 1977; as cited in Greenleaf, 2013) and distributed leadership (Spillane, 2006) emphasise collective responsibility and the involvement of teacher-leaders and ICT coordinators. Leadership is understood as a social process enacted by multiple actors, with shared responsibility and dynamically distributed roles. In this model, the principal restructures the organisation to expand leadership capacity (e.g., through delegated roles)—an approach particularly relevant in large schools and contexts with limited resources (Gronn, 2002; Spillane, 2006). This study does not favour any single leadership style as universally optimal. Instead, it recognises that effective digital leadership across diverse school contexts may incorporate elements from multiple approaches, for example, combining transformational vision with distributed implementation, or balancing the responsiveness of servant leadership with the demands of strategic planning. The qualitative analysis therefore remains open to identifying hybrid or context-specific configurations of leadership practices.

At an operational level, principals deploy a range of leadership practices. Research indicates a shift in the role of ICT coordinators (and, implicitly, principals) from a focus on infrastructure maintenance (the “electronic gatekeeper” role) towards an emphasis on how technology can enhance the pedagogical experience of teachers and students (the “pedagogical visionary” role) (McDonagh & McGarr, 2015).

Principals are decisive actors in successful technology integration by cultivating supportive school cultures and structures for professional development (Leithwood & Seashore-Louis, 2011; Fullan, 2014). They facilitate change at all stages—from initiating and planning digital school strategies to ensuring sustainable implementation of technology-enhanced pedagogical innovations (Fullan & Quinn, 2015). Within technological initiatives such as one-to-one (1:1) computing models, principals coordinate various resource types—human, social, and managerial (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). Strategic management of resources and data is essential for effective technology implementation in schools. Principals must plan and allocate financial and material resources for building and maintaining digital infrastructure, providing software and digital tools, and supporting teachers’ professional learning (Dexter, 2019; Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010). Their digital leadership also involves the use of school information systems for data-informed decision-making and for monitoring and evaluating teacher and student performance, thereby supporting continuous improvement of the educational process (Richardson & Sterrett, 2018; Schrum & Levin, 2016). As digital leaders, principals articulate a clear, shared vision and establish a supportive environment for effective technology adoption, motivating school teams to develop digital competences and pursue high performance (ISTE, 2018; Schrum & Levin, 2016).

In summary, the leadership role of the school principal in digitalisation is that of a strategic visionary, change agent, and transformational leader who actively models, supports, and facilitates technology integration while building capacity and promoting collaboration across the entire school community, including through the effective management of data and resources.

2.4. Contextual Factors and Challenges in the Implementation of Digital Leadership

The successful enactment of digital leadership is closely linked to a range of contextual factors, including infrastructure, resources, policy, organisational culture, and socio-economic conditions. Financial and technological constraints represent major barriers, as evidenced by SELFIE data across European countries: insufficient funding, outdated infrastructure, and weak technical support hinder digitalisation efforts (Castaño Muñoz et al., 2023; Peytcheva-Forsyth & Mizova, 2025). Many principals do not fully recognise their roles as technological leaders or lack the required competencies; investments frequently remain limited to hardware, without a coherent pedagogical vision or a conceptual framework for its use. The digital competence of teachers and students is a critical factor—misalignment between formal policy-driven expectations and actual skill levels can generate resistance to change (McDonagh & McGarr, 2015; Timotheou et al., 2023). At the school level, digital technologies are often adopted passively or in a formal manner by principals and leadership teams, without critical evaluation of their implications for strategic management, pedagogical practice, and student learning.

Well-structured professional development for teachers in digital pedagogy—particularly personalised and context-specific forms—shows strong correlations with successful technology integration in teaching practice (Castaño Muñoz et al., 2023).

Cultural and organisational factors such as teacher workload, lack of time for experimentation, and limited opportunities for technology-related training also affect the effectiveness of leadership strategies (Peytcheva-Forsyth & Mizova, 2025).

All these contextual factors can be categorised according to the extent to which principals can control them. External factors, which are largely beyond the influence of individual principals, include national policy frameworks, funding mechanisms, the socio-economic composition of student populations, and regional infrastructure disparities. Internal factors, which principals can influence more directly, include decisions on school-level resource allocation, the design of professional development programmes, the cultivation of collaborative cultures, and the selection of specific digital tools and platforms. However, even these internal factors are influenced by external circumstances: principals in well-resourced urban schools have more scope for strategic flexibility than those in under-resourced rural areas. This uneven distribution of agency helps explain the diversity of leadership approaches that principals adopt in response to digitalisation imperatives.

Comparative studies of principals’ digital leadership highlight variations across systems: in the United States, NETS-A standards foster structured leadership practices (Dexter, 2019; Pautz & Sadera, 2017), whereas in more centralised systems such as Turkey, approaches tend to be predominantly administrative (Banoğlu et al., 2023). The European context of school digitalisation—including Bulgaria—is characterised by fragmentation and the need to adapt international frameworks, particularly with respect to preparing principals for digital leadership (Peytcheva-Forsyth & Mizova, 2025).

2.5. The Bulgarian Context of Digitalisation and Managerial Perspectives

National strategic documents, such as the Strategy for the Digitalisation of Education 2021–2030 and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, set ambitious goals for the integration of STEM, cloud technologies, and digital competences across all levels of the education system. Managerial challenges in Bulgaria include persistent disparities between urban and rural schools in terms of resources and access to professional development. Particularly critical issues involve the lack of high-speed internet, outdated equipment, uneven development of principals’ leadership competences, and shortages of qualified staff (MoE, 2021, pp. 28–30).

Findings from the SUMMIT project, based on the SELFIE tool, reveal a phenomenon of “social desirability”, whereby principals tend to assess their schools’ digital maturity more favourably than the actual situation would suggest. This highlights the need for methodologically validated instruments to support objective evaluation and strategic planning (Peytcheva-Forsyth & Mizova, 2025).

In addition, several features of the Bulgarian school system directly influence the functioning of educational institutions:

- Limited institutional capacity to mitigate the effects of disadvantaged socio-economic conditions (poverty, bilingualism, low parental education). “In Bulgaria, the difference in mathematics performance between students with advantaged and disadvantaged socio-economic status is 108 points, which exceeds the OECD average of 93 points” (Bulgaria results from participation in PISA, 2022, p. 24).

- “Educational segregation”—schools operate within specific socio-economic settings and a competitive environment. Funding mechanisms based on “per student and per class” combined with demographic characteristics often lead to the clustering of students with similar abilities and results within the same schools. “PISA 2018 data show that in OECD countries nearly one-third (29%) of the variance in student performance is attributable to school-level factors. In Bulgaria, this figure reaches 55%, placing the country alongside Germany, the Netherlands, Israel, and others” (Bulgaria results from participation, 2018, p. 49).

- Quasi-market conditions and the push towards school autonomy, without mechanisms that incentivise quality over quantity of students (Parvanova, 2020). As a result, the school system can be described as highly fragmented, encompassing a diverse range of managerial visions, practices, and leadership styles—including those related to digitalisation. Each school, depending on its context, characteristics, and current state of development, integrates digitalisation differently and conceptualises its significance through distinct paradigms—strategic, operational, educational, administrative, etc.

These structural features of the Bulgarian school system carry direct consequences for how principals conceptualise and enact digital leadership. In high-performing schools serving advantaged populations, principals could leverage digitalisation to maintain a competitive advantage and attract students, emphasising innovation and strategic partnerships. In contrast, in schools serving disadvantaged communities or operating under resource constraints, principals are often compelled to prioritise basic infrastructure and compensatory measures, positioning digitalisation as a means to mitigate rather than exacerbate current disparities. The high degree of between-school variance in student outcomes (55% in Bulgaria compared to the OECD average of 29%) indicates that principals’ leadership approaches, including their digital strategies, are likely to vary systematically across schools’ socio-economic profiles and performance levels. This context-dependent variation underpins the present study’s focus on identifying typological profiles of digital leadership, rather than presupposing a single normative model.

This review has established that digital leadership encompasses strategic vision, pedagogical transformation, and stakeholder engagement, as defined in frameworks such as DigCompOrg and ISTE. However, there is limited empirical evidence on how principals enact these dimensions in practice, particularly in fragmented policy contexts with uneven capacity and pronounced social and economic differences. The Bulgarian context is an example of this: although policy documents set out ambitious digitalisation goals, school principals must address persistent infrastructural deficits, regional inequalities, and institutional fragmentation, which influence the feasibility and forms of digital leadership.

Against this background, the present study examines principals’ self-reported leadership practices and managerial strategies using an integrated mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative self-assessments with qualitative cluster analysis. The study questions the idea of digital leadership as a uniform developmental trajectory, instead conceptualising it as context-sensitive configurations of practice, conditioned by institutional capacity and performance stability. The research aims, methodological design, and analytical procedures are detailed in the following section.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Aim

In accordance with the research objectives outlined in the introduction, this study considers how school principals in Bulgaria conceptualise and enact their roles as digital leaders in a context of fragmented policies and uneven digital capacity. Specifically, the research is designed to (a) analyse principals’ self-assessments of key aspects of strategic digital management and (b) identify typological profiles of digital leadership based on principals’ declared styles and managerial practices, alongside the contextual factors that shape these profiles.

The methodology combines nationally representative quantitative data (N = 349) with in-depth qualitative analysis (N = 30) to reveal overarching trends and the underlying mechanisms shaping principals’ leadership approaches.

3.2. Approach and Research Design

The study adopts a mixed sequential design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018), integrating quantitative and qualitative phases (quan → QUAL). This notation reflects the priority of the qualitative phase, which constitutes the core of the study—namely, the identification and conceptualisation of digital leadership profiles. The methodology is grounded in inductive logic aligned with the principles of constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014).

The design consists of two main stages:

- Quantitative stage (quan): A nationally representative survey (N = 349) mapping general trends in school leaders’ self-assessments regarding the strategic management of digitalisation. This stage provides the national contextual framework. The qualitative sample (N = 30) is a structurally defined subset of the quantitative sample (N = 349), selected through quota sampling to ensure maximum variation.

- Qualitative stage (QUAL): An in-depth analysis of managerial conceptions and practices through a two-step procedure with 30 school principals: preliminary written questionnaires followed by semi-structured interviews, thematic coding, and cluster analysis. The aim is to achieve deep understanding and conceptualisation of leadership styles and managerial strategies.

Data integration is carried out sequentially: the quantitative results establish the broad national context, while the qualitative analysis reveals the mechanisms and strategies underpinning the aggregated models/profiles/patterns. The analysis follows the principles of constant comparison (Corbin & Strauss, 1990) and the iterative flexibility characteristic of the constructivist grounded theory tradition (Charmaz, 2014). Although the qualitative sample was pre-structured, the analytical process itself was emergent—additional data (institutional indicators, such as national external assessment results) were incorporated to empirically validate emerging digital leadership profiles and practices, reflecting the adaptive nature of the study.

3.3. Quantitative Phase

3.3.1. Sample

The quantitative phase is based on a nationally representative, stratified cluster sample of 359 schools, drawn from a target population of 1967 general education schools (grades 1–12, excluding vocational schools and special educational needs centres). The sample size was determined using the standard formula for proportions in finite populations, with a 95% confidence interval and a maximum sampling error of 4.6%, assuming p = 0.5.

Schools were stratified by (a) administrative region (28 NUTS 3 regions); (b) settlement type (village, town, or regional capital); (c) school type (primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, profiled gymnasium, or other); and (d) school size (small: ≤100 students; medium: 101–300 students; large: >300 students). Within each stratum, schools were randomly selected with probability proportional to size (PPS). The achieved sample size of 349 schools (a response rate of 97.2%) ensures national representativeness and enables robust subgroup analyses.

In each school, one educational leader was surveyed—either the principal, a vice-principal, or the head of the ICT unit responsible for digitalisation—resulting in N = 349 respondents. Including ICT coordinators reflects the distributed nature of digital leadership in Bulgarian schools. According to Ordinance No. 15 on Educational Specialists (Article 29), heads of ICT departments are responsible for planning and implementing technology integration, serving as a link between national digitalisation policies and the specific needs of individual schools. As informatics specialists with pedagogical training, they have the formal authority to formulate digital strategies and develop institutional digital maturity. This justifies their inclusion as valid respondents on questions relating to school governance.

3.3.2. Instrument

This study employed the official Bulgarian adaptation of the SELFIE Questionnaire (Self-reflection on Effective Learning by Fostering the Use of Innovative Educational Technologies), developed by the European Commission for institutional self-assessment of digital transformation in school environments (European Commission, JRC, 2018). The instrument is conceptually grounded in the European Commission’s DigCompOrg framework and is designed to support collective reflection within school organisations on their digital capacity and practices. For the purposes of this study, the subscale “School Governance” was used, comprising eight indicators measuring the strategic management of digitalisation. The ‘School Governance’ subscale was selected because it directly measures principals’ strategic management of digitalisation, which is the core focus of RQ1, including digital strategy development, innovation support, data-driven decision-making, and partnership development. These dimensions align with the conceptualisation of leadership as the central mechanism for organisational digital capacity-building in the DigCompOrg framework (Kampylis et al., 2015). Although SELFIE includes subscales for teaching practices and student perspectives, the governance dimension captures the strategic decisions made by school leadership teams at an institutional level, making it the most appropriate instrument for examining principals’ self-assessments of their leadership role. The scale covers key aspects related to the formulation and updating of the digital strategy, support for innovation, data-informed decision-making and partnerships, resource provision, and ethical considerations in the use of technology. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), with an additional “not applicable” option to ensure relevance across diverse educational contexts. The adaptation of the instrument to the Bulgarian context was carried out in alignment with the original structure and wording, ensuring functional equivalence and comparability of the empirical data with international studies employing SELFIE.

3.3.3. Psychometric Properties

The scale adapted for the Bulgarian context demonstrates high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83). Corrected item-total correlations range from 0.45 to 0.68, and the α value when individual items are removed remains within the range of 0.79–0.83, confirming the stability and homogeneity of the construct.

3.3.4. Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

The survey was administered online between March and May 2024, with participation entirely voluntary and anonymous. In accordance with ethical standards, all participants signed a written informed consent form, which explicitly detailed the aims and procedures of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw at any point without negative consequences. The consent form clearly stated that all collected data would be processed and analysed exclusively in anonymised form, with no possibility of identifying individual participants. It was explicitly indicated that the results may be used for academic publications, reports to the Ministry of Education and Science, and other analytical, expert, and scientific outputs aimed at improving educational practice, in full compliance with data protection and confidentiality requirements under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The data were processed and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26. Descriptive statistical methods were applied (means, standard deviations, frequency distributions), together with independent-samples t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for group comparisons, and Pearson correlation analysis to examine relationships between variables. In the present publication, and in response to the first research question, we report the descriptive statistics outlining the general picture of school leaders’ self-assessments regarding the strategic management of digitalisation.

3.4. Qualitative Phase

3.4.1. Sample

The qualitative component includes an in-depth analysis of 30 preliminary written questionnaires and 30 semi-structured interviews with school leaders from 30 schools representing diverse regions, institutional types, and school sizes. Participants in this analytical subsample were selected through quota and expert sampling to ensure maximum thematic saturation and contextual diversity. The analytical sample of 30 schools constitutes a structured subset of the national sample of 349 schools. The participants in the qualitative study are presented in Table 1 according to key demographic and professional characteristics.

Table 1.

Profile of participants in the qualitative study by main characteristics.

3.4.2. Instruments

The qualitative phase employed a two-step procedure: (1) a preliminary written questionnaire concerning school policies and strategies related to digitalisation and (2) semi-structured interviews (N = 30) with school principals. The interviews followed an open-ended protocol that allowed flexibility for probing emerging themes. All interviews were conducted online, audio-recorded (with informed consent), and transcribed verbatim for the purposes of analysis.

3.4.3. Analysis

An inductive thematic coding procedure was undertaken, whereby the categories and their constituent codes were generated directly from the empirical material (Braun & Clarke, 2006) through a detailed analysis of the content of the five most extensive interviews, without the imposition of any prior framework. The abstracted codes were then thematically consolidated and organised into a comprehensive codebook structured around four key thematic categories:

- Leadership and change management;

- Collaboration and networks;

- School digitalisation;

- Contextual challenges and constraints.

The four thematic categories emerged by means of iterative consolidation of codes derived from the initial analysis of the five most extensive and comprehensive interviews. Codes related to principals’ decision-making approaches, vision articulation, and change strategies were grouped under “Leadership and Change Management.” Codes concerning partnerships, professional communities, and inter-school networks were grouped under “Collaboration and Networks.” Codes explicitly focusing on technology adoption, digital tools, and pedagogical integration formed “School Digitalisation.” Finally, codes identifying barriers, constraints on resources, and external constraints (e.g., policy guidelines, infrastructure deficits, funding limitations) were consolidated as “Contextual Challenges and Constraints.” This categorisation was confirmed by team discussion and applied consistently across all 30 interview transcripts. The categories are intentionally broad to accommodate the diversity of principals’ narratives while supporting systematic comparison across cases.

Cluster analysis and co-occurrence analysis were applied to identify the characteristics of leadership styles and to map the frequency and patterns of managerial practices. The coding process was iterative, involving double reading of all transcripts. To ensure interpretive rigour, the emerging system of codes was discussed within the research team, with disagreements resolved through consensus.

During the identification of digital leadership profiles, the resulting clusters were examined in relation to contextual variables (school type, region, size). It was found that these structural characteristics did not reveal systematic patterns that could explain cluster membership. This observation shifted the analytical focus towards student educational outcomes as a potential indicator of institutional context. Following the study’s inductive logic, a comparative analysis of student achievement (National External Assessment and State Matriculation Examination data for 2022–2024) was undertaken to characterise the institutional environments associated with different digital leadership profiles. The specific procedures for processing these data are detailed in the Results section, as this methodological step emerged in response to empirical insights during the analysis.

Case Similarity and Cluster Formation

The analytical sample of 30 schools includes institutions varying in type, size, and geographical location. This diversity suggests potential differences in leadership styles and managerial practices related to digitalisation. For the purposes of the analysis, a case similarity procedure was applied to group schools into clusters based on shared characteristics of digital leadership, managerial styles, and practices. In this study, cluster formation is used as a qualitative analytical procedure, grounded in the interpretation of thematic convergences, rather than as a quantitative method for statistical classification.

The approach aligns with principles of data reduction based on empirical characteristics (Guest & McLellan, 2003), where numerical coefficients function as heuristic tools for visualising relationships among codes and structuring large volumes of qualitative data. The final typology, however, is the result of an abductive analytical process—a recursive form of “double fitting” between emerging empirical patterns and theoretical concepts (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). In this sense, the clusters represent interpretive constructs, rather than predefined categories; they emerge through an iterative synthesis of observed thematic patterns and theoretical frameworks of digital leadership. The analysis was conducted in two phases:

Phase 1—Selection of the codes forming the basis of the case similarity analysis

The size of the sample and the diversity of cases generated a substantial number of themes and sub-themes present across the analysed schools. The codebook for the categories “Leadership and Change Management” and “Collaboration and Networks”, which outline the leadership practices and styles, is provided in Appendix A.

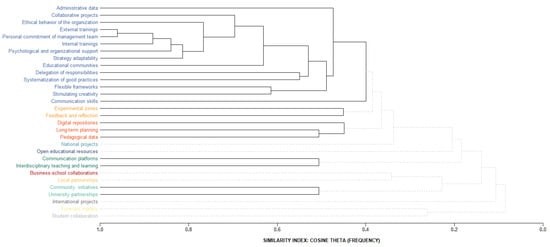

The codes from the categories “Leadership and Change Management” and “Collaboration and Networks” were analysed using Coding Co-occurrence Within Case, applying the Cosine theta coefficient (Figure 1). The Cosine theta coefficient ranges from 0 to 1. This method enables the identification of thematic relationships between codes, particularly when working with large volumes of qualitative data (Troussas et al., 2023; Romero & Ventura, 2020; Kalita et al., 2025).

Figure 1.

Similarity links between codes.

Based on the agglomeration matrix of codes (Table 2), the case similarity analysis was conducted using only those codes that formed links with a similarity coefficient ≥ 0.5. The choice of the 0.5 threshold is based on three empirical criteria specific to the present corpus of texts (interviews):

Table 2.

Agglomeration matrix of codes.

- Empirical saturation: When the threshold falls below 0.5, the number of connected codes increases exponentially (e.g., at 0.4, 52 codes are included), which introduces noise and diminishes interpretative clarity. When the threshold exceeds 0.6, only nine codes remain, which eliminates important nuances. The 0.5 threshold represents an elbow point at which thematic richness and analytical precision are optimally balanced.

- Interpretative distinctiveness: Analysis of the dendrogram (Figure 1) shows that at a coefficient ≥ 0.5, clearly delineated thematic groups emerge, allowing the identification of conceptually related managerial practices.

- Thematic representativeness: The 18 selected codes appear in interviews with at least 40% of the school principals, ensuring a balance between representativeness and specificity.

This approach follows the principle that the optimal similarity threshold depends on the properties of the specific textual corpus (Niekler & Jähnichen, 2012) and must achieve a balance between sufficient breadth of code coverage (comprehensiveness) and the ability to interpret the codes in a meaningful and traceable way (interpretability) (Guest & McLellan, 2003).

This procedure highlights the core practices—the codes that co-occur within textual segments and delineate the core of the managerial approaches declared by the principals.

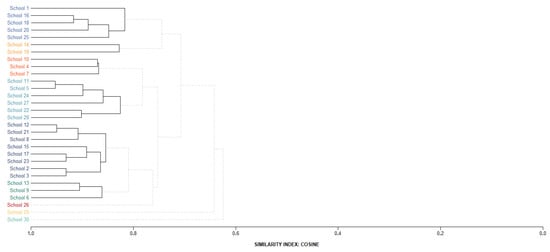

Phase 2—Clustering of the schools in the analytical sample

The case similarity analysis of the schools (Figure 2) identifies six clusters at a similarity coefficient above 0.8. Three schools fall outside the clusters as outliers. The choice of the 0.8 threshold is based on a sensitivity analysis in which thresholds between 0.7 and 0.9 were varied:

Figure 2.

Clustering of the schools.

The 0.8 threshold maximises within-cluster homogeneity while preserving interpretative distinctiveness, following the principle of conceptual parsimony—achieving the smallest possible number of typological categories that still capture the maximal variation in the data (Collier et al., 2012). This approach aligns with the understanding that typologies must strike a balance between conceptual precision (clearly delineated types) and analytical manageability (a sufficiently small number of categories to allow for meaningful interpretation). Possible variations in code clusters are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variation in code clusters.

The similarity coefficient (Cosine) ranks schools with values above 0.8, with three schools falling outside the clusters and identified as outliers. Six clusters are formed, each comprising a different number and type of schools. The distribution of schools across the six clusters by location, size, and type is presented in Section 4.2.1.

For the subsequent analysis, Cluster 1, Cluster 4, and Cluster 5 were selected, comprising 63.3% of the sample (19 out of 30 schools). The selection follows the logic of purposeful sampling with maximum variation, recommended for abductive analysis (Patton, 2014; Vila-Henninger et al., 2024), and is based on four criteria:

- Representativeness: The three clusters encompass two thirds of the sample, ensuring empirical breadth and a sufficiently robust basis for theoretical generalisation.

- Maximum variation: They demonstrate the full spectrum of managerial approaches—from highly strategic and resource-rich (Cluster 1), through balanced, pragmatic models emphasising results (Cluster 5), to strongly adaptive approaches focused on operational support (Cluster 4). This varied selection makes it possible to identify both shared and context-specific practices (Vila-Henninger et al., 2024).

- Analytical clarity: These clusters exhibit the most clearly expressed and conceptually coherent patterns, with high internal homogeneity, which facilitates the interpretative synthesis between empirical observations and theoretical constructs.

- Theoretical productivity: They represent contrastive cases (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012), whose comparison reveals the mechanisms through which digital leadership adapts to varying institutional contexts.

The remaining three clusters (11 schools; 36.7%) are not excluded due to low quality, but because of a different analytical rationale:

- Cluster 2 (2 schools) and Cluster 6 (3 schools): Their very small size limits the possibility of identifying stable patterns across the principals’ narratives.

- Cluster 3 (3 schools): Displays high internal heterogeneity, suggesting the presence of hybrid or transitional forms—schools combining elements of different leadership styles without a clearly dominant logic.

- Outliers (3 schools): Represent unique configurations requiring a separate, case-by-case analysis beyond the scope of a typological approach.

This selection follows the principle of conceptual parsimony (Collier et al., 2012), which justified the focus on those types yielding maximal analytical return within a limited space for presentation. A detailed examination of the remaining clusters would increase descriptive completeness but without a proportional increase in theoretical productivity (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). These clusters remain candidates for future analysis, pending additional data that would allow the validation of their hybrid characteristics.

Analysis of Managerial Practices Within Clusters

Within the selected clusters, a coding co-occurrence analysis was applied to all 30 codes from the categories “Leadership and Change Management” and “Collaboration and Networks” in order to capture the full range of activities and leadership styles, rather than focusing solely on the 18 codes with a similarity coefficient ≥ 0.5 that shaped the cluster formation.

While the core codes (the 18 with coefficients ≥ 0.5) delineate the fundamental structure of digital leadership and underpin the clustering, the remaining codes may play a complementary—or even pivotal—role within specific clusters. This logic follows the distinction between core and surface codes in thematic analysis (Guest & McLellan, 2003). The core codes define the structural backbone of the clusters, while the surface codes reveal context-specific nuances in managerial practices across different institutional profiles. Including all codes enables the identification of unique combinations of practices characteristic of each cluster.

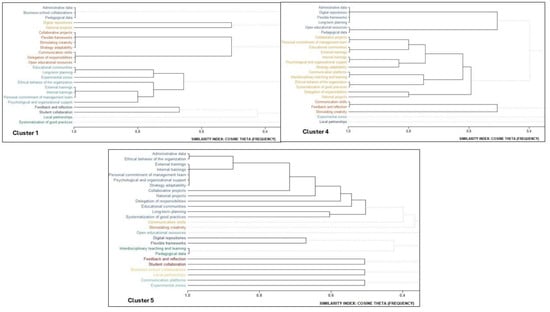

Analytical Procedure

The results of the coding co-occurrence analysis for the three main clusters are presented in Figure 3. The clustering of codes was conducted using a similarity coefficient ≥ 0.5. The selection of this threshold was grounded in the empirical properties of the data:

Figure 3.

Connections between codes in the analysed clusters.

- At higher thresholds (e.g., 0.6–0.7), all codes merge into only 2–3 groups, limiting the ability to identify specific roles and practices of leaders across clusters.

- At lower thresholds (e.g., 0.3–0.4), the same codes appear in a single overarching group common to all clusters, resulting in the loss of distinct connections emerging from principals’ reported actions, attitudes, and judgements.

A threshold of 0.5 provides an optimal balance between identifying shared patterns and preserving context-specific differentiation.

The analysis of code co-occurrence across the three clusters reveals distinct patterns of interconnections within each cluster. The variation in leadership styles and managerial practices is visualised through:

- Differences in the number of subclusters of codes (i.e., groups of interrelated practices);

- Differences in the number of codes within each subcluster (indicating the complexity and breadth of managerial approaches);

- Differences in the strength of links between specific codes and subclusters (indicating the centrality or peripheral nature of certain practices).

The interpretative logic follows an abductive approach (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012): the dendrograms (Figure 3) present the empirical patterns of code co-occurrence, but the naming and conceptualisation of the leadership styles (e.g., strategic–collaborative, balanced–pragmatic) result from an iterative synthesis of

- The visual clustering patterns (which codes tend to co-occur);

- The textual content of the interviews (what principals explicitly say);

- Theoretical frameworks of digital leadership (how leadership is conceptualised in the literature).

This process is qualitative in nature and aims to identify interpretive models of leadership styles and practices related to digitalisation in Bulgarian schools, rather than to define statistical categories.

Illustration of the Interpretative Process

To illustrate the transition from dendrograms to the naming of leadership styles:

Empirical observations (from the dendrogram of Cluster 1):

- The codes “long-term planning” + “professional learning communities” + “internal/external training” + “personal commitment of school leadership” form a tightly connected group (coefficient > 0.8).

- The codes “collaborative projects” + “school–business partnerships” + “encouraging creativity” form a second strongly connected group.

- Textual confirmation (from Cluster 1 interviews):

- Principals consistently speak about “vision”, “a multi-year perspective”, “strategic planning”.

- They emphasise “teamwork”, “professional communities”, “sharing experience”.

- Theoretical conceptualisation:

- The combination of long-term planning + systematic training + partnerships aligns with strategic leadership (Hallinger & Heck, 2011).

- The emphasis on communities + shared experience + collaboration aligns with collaborative leadership (Harris & DeFlaminis, 2016).

Abductive conclusion: Cluster 1 demonstrates a “strategic–collaborative leadership style”—a managerial approach that combines a long-term vision with collective enactment.

The same logic is applied to Cluster 4 and Cluster 5, analysing their distinctive combinations of codes and associated interview content.

3.4.4. Sequential Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Table 4 illustrates how the two samples are sequentially integrated within the mixed-methods design.

Table 4.

Sequential integration of quantitative and qualitative samples.

- The quantitative sample provides representativeness and a picture of typical strategic digital management practices.

- The qualitative sample enables the identification of typological profiles, specificities, and mechanisms underlying principals’ self-assessments—enhancing the interpretative power and depth of the research strategy and providing contextual meaning to the numerical quantitative results.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), national legislation, and established principles of research ethics. All participants provided written informed consent, which included information about the aims of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw at any time. Additional consent for audio recording was obtained for the interview phase.

Anonymity was ensured through data coding and the removal of all identifying information. Audio recordings and transcripts were securely stored with restricted access. Participants were informed that the results may be used for academic publications and education policy analyses, with strict adherence to data protection and confidentiality principles. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sofia University St Kliment Ohridski (reference No. 93-P-289/19 December 2023).

4. Results

4.1. Principals’ Assessments of Key Aspects of the Strategic Management of Digitalisation in Their Schools

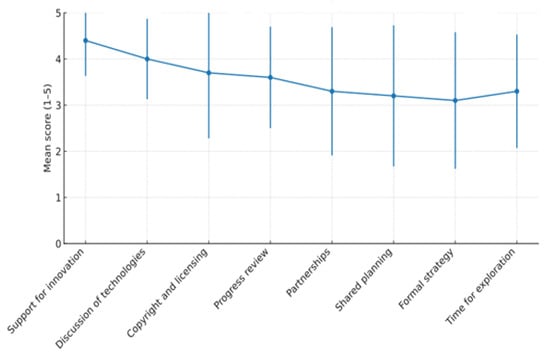

In response to the first research question (RQ1), which concerns how school leaders evaluate key aspects of the strategic management of digitalisation within their organisations, an analysis was conducted based on data from the School Governance subscale of the SELFIE for Schools instrument, developed in alignment with the DigCompOrg framework (N = 349; α = 0.831). This domain comprises eight indicators measuring strategic managerial practices related to digitalisation. School leaders provided their self-assessments for each item using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, with an additional “not applicable” option where a given practice did not apply to their context.

The results across the eight indicators outline a multifaceted profile of strategic management practices in schools. The overall mean score is 3.6 (SD ≈ 0.8), indicating a moderately high level of endorsement of digital management practices, albeit with clear variation across the individual indicators (items). Figure 4 presents the quantitative values of each dimension within this profile.

Figure 4.

Profile of strategic managerial practices based on mean scores from the SELFIE for Schools instrument.

Support for teachers to experiment with new methods based on digital technologies (support for innovation) emerges as the strongest developed aspect (M = 4.4; SD = 0.77; Mo = 5), endorsed by 89.7% of respondents. The minimal proportion of “not applicable” responses (0.6%) indicates that this practice is perceived as universally relevant and not dependent on school-specific contextual factors. This result suggests the presence of an established pedagogical culture in which technological experimentation forms part of teachers’ professional identity. A similar pattern is observed for discussions concerning the advantages and disadvantages of digital technologies (M = 4.0; SD = 0.87; Mo = 4). The high level of agreement (79.3%) and the low share of “not applicable” responses (0.9%) indicate that reflection on digitalisation is a well-established managerial practice. Nevertheless, the mode (Mo = 4, not 5) indicates a more moderate level of establishment and consolidation of this practice, suggesting that discussions are likely held regularly but do not always lead to strategic decision-making. More ambiguous results appear for indicators related to the introduction and application of formal managerial practices. The implementation of copyright and licencing procedures shows a relatively high mean score (M = 3.7; Mo = 4), yet also a notable proportion of “not applicable” responses (8.3%). This suggests that while the majority of schools implement copyright norms, nearly one in ten institutions do not view this as a relevant managerial priority. Monitoring progress in technology-enhanced learning (M = 3.6; Mo = 4; 57% agreement) appears to be a more problematic aspect. Here, there is no full consolidation of opinions, and the variance in scores is higher (SD = 1.10), which likely indicates instability in the monitoring and evaluation cycle of digital processes.

Substantial challenges are also evident in indicators relating to “external” collaboration in technology integration and the adoption of a digital strategy. The use of technologies in partnerships yields a mean of M = 3.3 (Mo = 3), with almost 10% marking the item as “not applicable”. A similar pattern is found for the collaborative development of a digital strategy (M = 3.2; Mo = 4), where “not applicable” reaches 13.8%—the highest proportion across the entire scale. This is a concerning signal: in approximately one out of every seven schools, teachers do not participate in strategic planning, which hinders collective engagement with digital transformation.

The existence of a digital strategy is among the lowest-rated indicators (M = 3.1; Mo = 3). Fewer than 50% of principals confirm that their institution has a formalised strategy, while 12.3% report that this issue is not applicable at all. This result reflects a structural deficit: while digitalisation is supported at the level of pedagogical practice, the strategic framework—the organisational foundation—remains insufficiently developed. Providing time for methodological exploration of digital technology use (M = 3.3; Mo = 3) is also characterised by low cumulative agreement (44.4%), with 5.2% of respondents marking “not applicable”. This finding reflects, to some extent, persistent systemic difficulties related to the inability to guarantee protected time for teachers and pedagogical staff to experiment and engage in professional growth. In practical terms, this limits the potential for introducing innovations into the educational process.

In summary, the analysis of principals’ self-assessments of the strategic management of digitalisation in Bulgarian schools reveals a marked dissonance between the well-established culture of pedagogical support for innovation and the limited institutionalisation of sustainable managerial practices. The data clearly show that school leadership teams consistently encourage teachers to experiment with technology and maintain an environment in which the discussion of pedagogical innovation is an important component of school life. At the same time, strategic planning for digitalisation at organisational level remains underdeveloped. A substantial proportion of schools lack a formally articulated digital strategy and collaboratively shared planning, and it is precisely on these indicators that the highest proportions of “not applicable” responses are recorded. This indicates not only that some schools lack a systematic framework for digital transformation, but also that the strategic management of digital processes remains weakly embedded in practice. This manifests in three concrete ways: (1) fewer than 50% of schools report having a formalised digital strategy; (2) 13.8% of principals indicate that teachers do not participate in strategic planning; and (3) inter-institutional collaboration for technology integration is limited, with nearly 10% reporting it as “not applicable.”

The absence of well-established policies, the limited involvement of pedagogical teams in managerial decisions, and the deficits in inter-institutional collaboration related to technology integration constrain the advancement of digitalisation at the organisational level.

Fragmentation in the approach is further reinforced by resource constraints—particularly in relation to the time allocated for professional development and the conditions enabling methodological exploration and the introduction of new practices. Limited access to such resources further hinders the timely adoption and diffusion of innovations within the school environment. In addition, issues related to copyright and licencing often remain undervalued, which may have implications for both teaching and administrative work. In conclusion, while schools in Bulgaria demonstrate a high level of commitment to and support for pedagogical innovation, the effectiveness of digital transformation remains constrained by the lack of strategic coherence, insufficient institutional support, and weak horizontal collaboration. The identified constraints can be distinguished by the degree of control principals exercise over them. Internal factors, such as time allocation for professional development (M = 3.3), participation of teachers in strategic planning (13.8% report “not applicable”), and systematisation of collaborative practices, fall within principals’ managerial authority, although they are affected by resource availability. External factors, including the absence of formalised digital strategies in nearly 50% of schools, limited inter-institutional collaboration (10% report “not applicable”), and infrastructure constraints affecting copyright implementation (8.3% “not applicable”), reflect systemic deficits that lie largely outside individual school control and require policy-level interventions. This uneven distribution of agency underscores the need for multi-level support: while principals can strengthen internal processes, such as fostering innovation cultures and protecting time for professional learning, sustainable digital transformation requires addressing external structural barriers through national policy guidelines, funding mechanisms, and regional professional development activities.

These findings highlight the need for targeted policies for developing digital leadership, expanding teacher participation in managerial processes, and implementing systemic measures for sustainable resource provision and inter-school partnership.

4.2. Managerial Practices and Leadership Styles in School Digitalisation

4.2.1. Cluster Analysis

In response to the second research question (RQ2), which concerns what profiles of digital leadership can be identified, based on principals’ declared styles and practices, a cluster analysis was conducted on the analytical sample of 30 schools. Following the procedures described in Section 3.4.3, six clusters were identified at a similarity coefficient above 0.8, with three schools falling outside the clusters as outliers. For the subsequent analysis, Cluster 1, Cluster 4, and Cluster 5 were selected, comprising 63.3% of the sample (19 out of 30 schools), based on criteria of representativeness, maximum variation, analytical clarity, and theoretical productivity.

The characteristics of the schools within the three selected clusters are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the cases within the clusters.

4.2.2. Analysis of Managerial Practices and Leadership Styles Within the School Clusters

The analytical procedures for identifying leadership styles within clusters are described in Section 3.4.3. Coding co-occurrence analysis was applied to all 30 codes from the categories “Leadership and Change Management” and “Collaboration and Networks.” The results for the three main clusters are presented in Figure 3, revealing distinct patterns of code interconnections characteristic of each cluster.

Based on the analysis of code co-occurrence patterns and principals’ interview narratives, three leadership styles were identified. The following sections present the managerial practices and leadership characteristics of each cluster.

Cluster 1: Strategic–Collaborative Style

General characteristics

Cluster 1 is characterised by a proactive and strategically oriented approach to digitalisation, in which technologies are conceptualised as instruments for long-term institutional transformation rather than as tactical solutions to immediate problems. This leadership approach relies on planned and purposeful action, continuous adaptation, and strong alignment between leadership, resources, partnerships, and professional communities. The main constraints include resource shortages, the ongoing need for staff training, and the varying levels of digital competence among teachers. The time horizon is long-term, with sustained steps implemented progressively over several years.

Illustrative quotations:

“Our goal is for digital technologies to become a natural part of teachers’ and students’ everyday work.”

Thematic configurations: Core linkages between practices

The co-occurrence analysis (Figure 3, Cluster 1) reveals six key configurations of strongly interconnected practices (similarity coefficient ≥ 0.8) that shape this leadership style:

- Communication and Open Resources (coefficient 1.0)

Linked codes: Communication skills + Open educational resources

Interpretation: Open dialogue and the sharing of digital materials emerge as drivers of innovation. Principals emphasise active use of digital platforms and the systematic exchange of resources within the teaching staff.

Textual confirmation:

“Teachers genuinely make active use of this platform.”

- 2.

- Collaboration and Creativity (coefficient 0.95)

Linked codes: Collaborative projects + Encouraging creativity

Interpretation: Joint initiatives are seen as catalysts for innovation. Principals deliberately encourage technology integration through project-based learning and teamwork.

Textual confirmation:

“We encourage the introduction of information technologies in teaching, including through financial support.”

- 3.

- Strategic Planning and Professional Communities (coefficient 0.91)

Linked codes: Long-term planning + Professional learning communities

Interpretation: Strategic thinking is reinforced by professional networks that provide continuity and shared expertise. Principals emphasise the priority of pedagogical integration of technologies.

Textual confirmation:

“What matters most is the use of digital technologies in teaching.”

- 4.

- Systematic Training and Leadership Engagement (coefficient 0.88)

Linked codes: Internal training + External training + Leadership personal engagement

Interpretation: A combination of internal knowledge exchange and external professional development, actively supported and often modelled by the principal, creates a culture of continuous learning. Leadership involvement is not merely declarative but operational.

Textual confirmation:

“I always ask the students whether there is anything I can improve.”

- 5.

- Partnerships and Data-Driven Decisions (coefficient 0.85)

Linked codes: School–business partnerships + Pedagogical data

Interpretation: External partnerships (particularly with the business sector) and the use of performance data form the basis for managerial decision-making. Technologies are integrated through real projects with innovative components (e.g., artificial intelligence).

Textual confirmation:

“They are our partners in a number of projects… the focus was on the use of artificial intelligence…”

- 6.

- Strategic Adaptability (coefficient 0.82)

Linked code: Adaptability of the strategy (central standalone code)

Interpretation: Careful, step-by-step introduction of new technologies according to contextual needs is a defining characteristic. Principals balance innovation with the risk of overload.

Textual confirmation:

“We need to approach this very carefully so as not to overwhelm teachers.”

Synthesis: Managerial Practices and Leadership Style

Key practices

- Systematic internal training and exchange of expertise;

- Participation in external professional development;

- Building partnerships with external organisations and the business sector;

- Use of pedagogical and administrative data to inform decisions;

- Encouraging creative and innovative projects.

Leadership Style: Strategic–Collaborative

Characterised by

- A strong focus on communication and feedback;

- Promotion of collaboration and team culture;

- Long-term strategic planning;

- Context-sensitive adaptability;

- Active support for professional development.

Leadership in Cluster 1 is personally engaged in the process of digitalisation: principals not only articulate the vision but actively participate in its implementation through training, feedback, and partnerships.

Cluster 4: Supportive–Collaborative Style

General characteristics

Cluster 4 conceptualises digitalisation as a combination of technological enhancement and pedagogical development aimed at student engagement, interactive learning, and collaborative work. The style is moderately proactive yet characterised by a need for clearer strategy and long-term planning. Support is provided through internal and external training, the exchange of good practices, communication platforms, and project work. Constraints include the absence of a comprehensive school-wide vision for digitalisation, the need for structured planning, and various administrative limitations. The time horizon is medium to long term, with an emphasis on the future clarification of goals.

Illustrative quotations:

“Digital technologies help students engage actively with the learning material; they make learning more interesting and interactive.”

Thematic configurations: Core linkages

- Innovative resources and competence-based selection (coefficient 1.0)

Linked codes: Open educational resources + Pedagogical data

Interpretation: Integration of innovative instructional tools combined with monitoring digital competence during recruitment.

Textual confirmation:

“Children learn with Envision from an early age—one computer, many mice…”

- 2.

- Communication and reflection (coefficient 0.96)

Linked codes: Communication skills + Feedback and reflection

Interpretation: Emphasis on informal information exchange and experience-sharing among all team members, regardless of hierarchy.

Textual confirmation:

“The good thing is that we communicate a lot, and when someone has a solution to a problem, they are not afraid to share it. It doesn’t matter which part of the team they belong to…”

- 3.

- Platforms for interdisciplinary integration (coefficient 0.93)

Linked codes: Communication platforms + Interdisciplinary teaching

Interpretation: Technologies facilitate interactive teaching and collaboration between teachers with varying levels of digital competence.

Textual confirmation:

“We have a practice where the technology teacher works with a colleague who wants to use technology in class. When they combine forces, one does not worry about the technology and leads the lesson…”

- 4.

- Leadership engagement and project work (coefficient 0.90)

Linked codes: Collaborative projects + Leadership personal engagement

Interpretation: Principals actively encourage participation in projects and provide feedback through systematic observations.

Textual confirmation:

“Every observation is followed by a discussion.”

- 5.

- Ethics and systematisation of practices (coefficient 0.88)

Linked codes: Ethical conduct of the organisation + Systematisation of good practices

Interpretation: Combination of copyright compliance (integrated into the curriculum) with mentoring and exchange of practices.

Textual confirmation:

“Sharing good practices; mentoring.”

- 6.

- Need for strategic vision (coefficient 0.85)

Linked codes: Digital repositories + Long-term planning

Interpretation: Technology and platforms exist, but a comprehensive strategic framework is lacking.

Textual confirmation:

“The school does not have a clearly developed vision and strategy for integrating technologies into the learning process. Perhaps we need to work in this direction…”

- 7.

- Personalised internal training (coefficient 0.82)

Linked codes: Internal training + Psychological and organisational support

Interpretation: Internal training is adapted to teachers’ needs through surveys and peer-to-peer sharing.

Textual confirmation:

“When courses are organised within the school, they can be personalised according to each teacher’s needs…”

- 8.

- External training and professional communities (coefficient 0.79)

Linked codes: External training + Professional learning communities

Interpretation: Encouragement to participate in qualification courses and formation of working groups for mutual support.

Textual confirmation:

“Participation in qualification courses has a significant effect on teaching quality…”

Synthesis of managerial practices and leadership style

Key practices:

- Establishing professional learning communities and working groups;

- Organising internal and external training;

- Encouraging collaborative projects;

- Systematising and discussing good practices;

- Ensuring ethical use of digital resources;

- Maintaining digital repositories and platforms.

Leadership style: Supportive–Collaborative

Characterised by

- Active involvement of school leadership in observation and support;

- Encouragement of exchange among colleagues regardless of hierarchy;

- Commitment to ethical standards;

- Flexibility in adapting training to staff needs;

- Absence of systematic long-term planning in some schools.

Cluster 5: Balanced–Pragmatic Style

General characteristics

Cluster 5 is characterised by a pragmatic, results-oriented approach in which digitalisation is conceptualised as a tool for improving the quality of education through interdisciplinary integration, data use, and systematic/regular teacher qualification. Support is provided through access to pedagogical and administrative data, internal and external training, and active leadership engagement. Challenges include administrative constraints, ethical regulation, and the need to adapt practices to different institutional contexts. The time horizon is medium term, with clearly defined steps planned over several years.

Illustrative quotations:

“What contemporary digitalisation allows us to do is to work in a multidisciplinary way…”

Thematic configurations: Core linkages

- Interdisciplinary integration and data-driven approach (coefficient 0.89)

Linked codes: Interdisciplinary teaching + Pedagogical data

Interpretation: Digitalisation is used to support interdisciplinary connections and to monitor learning outcomes, combining pedagogical innovation with empirical oversight.

Textual confirmation:

“I monitor the learning outcomes in Computer Modelling and Information Technologies and observe open lessons.”

- 2.

- Leadership engagement and organisational support (coefficient 0.87)

Linked codes: Leadership personal engagement + Psychological and organisational support

Interpretation: The principals provide both structural and emotional support, including releasing teachers from lessons and facilitating pedagogical discussions.

Textual confirmation: