Abstract

The growth of generative artificial intelligence (GAI), remarkably, Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, converts the educational environment by empowering intelligent, data-driven education and curriculum design innovation. This study aimed to assess the integration of LLMs into higher education to foster curriculum design, learning outcomes, and innovative work behaviour (IWB). Specifically, this study investigated how LLMs’ perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) can support educators to be engaged in IWB—idea generation (IG), idea promotion (IP), opportunity exploration (OE), and reflection (Relf)—employing a web-based survey and targeting faculty members. A total of 493 replies were obtained and found to be valid to be analysed with partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). The results indicated that PU and PEOU have a significant positive impact on the four dimensions of IWB in the context of LLMs for curriculum development. The evaluated model can assist in bridging the gap between AI technology acceptance and educational strategy by offering some practical evidence and implications for university leaders and policymakers. Additionally, this study offered a data-driven pathway to advance higher education IWB through the adoption of LLMs.

1. Introduction

Large Language Model (LLM) technologies have shown exceptional potential in creating text, understanding language, and decision-making (Elshaer et al., 2025). These technologies have reinvented how learning is created, delivered, and managed within the academic framework (Dwivedi et al., 2023). Notably, LLMs are increasingly being employed to support curriculum design, enhancing the learning process and tailoring educational practices; as a result, several challenges and opportunities have emerged in higher education (Kasneci et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023). The successful application of LLMs in the higher education environment largely depends on faculty members’ acceptance and actual usage. Faculty members are not only the end-users of these technologies but also serve as key enablers for demonstrating how AI-driven technologies can be applied in education and curriculum design (Belda-Medina & Kokošková, 2024; Kong et al., 2024). Nonetheless, studies examining how faculty members perceive and use LLM tools in innovative ways for academic purposes remain scarce. While several previous studies focus mainly on the pedagogical aptitude of AI technologies, few have investigated the human factors impacting their effective integration into curriculum development (Ouyang et al., 2022).

The “Technology Acceptance Model” (TAM), first introduced by Davis (1989), can act as a theoretical background for understanding these human dimensions. As per TAM, two main factors—perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU)—can reshape people’s intentions and behaviour toward the acceptance of this emerging AI technology. These two factors have been widely validated in educational settings (Messmann & Mulder, 2012; Carmeli et al., 2006) and can offer a strong framework for evaluating educators’ perceived reactions to the integration of LLM tools. Yet, while TAM can successfully predict usage, it cannot explain how such usage can be translated into innovative work behaviour (IWB) that supports curriculum development and teaching development. In this context, IWB can offer a principal corresponding lens. IWB incorporates the processes through which people can recognise opportunities, create novel ideas, foster them within the corporation, and participate in reflective experiences to improve the outcomes (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). In university education, such behaviours are essential for acquiring approachable, data-driven, and forward-looking courses (Carmeli et al., 2006; De Spiegelaere et al., 2014). Nonetheless, little is understood about how technology acceptance predicts IWB among faculty members in the context of AI-driven curriculum advancement, particularly regarding the application of LLMs. This gap underscores the urgent need for empirical research testing the relationships between the two TAM factors (PU and PEOU) and the four IWB dimensions (opportunity exploration, idea generation, idea promotion, and reflection) to clarify how LLMs can predict academic innovation.

The later advancements in generative artificial intelligence (GAI), mostly LLMs, categorise these systems as a mature algorithmic engine that can develop curriculum content, program feedback, and safeguard complex instructional-created tasks. This algorithmic capability can transform LLMs from simple tools into proactive decision-support systems within the learning contexts (Yan et al., 2024). Accordingly, users’ acceptance of GenAI is not only a matter of interface satisfaction, but echoes deeper behavioural reactions to algorithmic consistency, trust, validity, and data-informed decision support (Guizani et al., 2025). Furthermore, this paper used PLS-SEM, which is a computationally thorough statistical technique that can manage latent constructs and their interrelationships as algorithmic computation graphs (Henseler et al., 2009; Sarstedt et al., 2021). By integrating the algorithmic nature of GenAI systems with the computational modelling capacity of PLS-SEM, the current study bridges behavioural theory and algorithmic processes to test computationally based phenomena in applied settings.

The main aim of this paper is to test the impact of technology acceptance (PU and PEOU) on the four dimensions of IWB in the higher education context of integrating LLMs into curriculum advancement. Accordingly, the following two main objectives can be explored: (1) testing the proposed structural model (TAM impacts on IWB) and assessing the predictive ability of technology acceptance factors on faculty members’ IWB employing PLS-SEM; and (2) offering a theoretical and practical understanding of how LLMs tools can promote innovation-oriented curriculum development and learning decision-making in university education.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. Section 2 aimed to review relevant prior literature on TAM and IWB and their interrelationships to justify the research hypotheses. Section 3 presented the research materials and methods. Section 4 presented the empirical results from the PLS-SEM analysis. Section 5 discussed the results obtained and elaborated more on the theoretical and managerial implications. Finally, Section 6 addressed the research limitations and opportunities for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

The advent of LLM tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and DeepSeek ushered in a new era of intelligent automation in higher education. These AI tools have demonstrated the ability to process natural language, synthesise complex information, and provide customised learning support, making them particularly valuable in the university context (Kasneci et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023). LLMs are gradually being implemented to improve curriculum development, the evaluation process, and academic writing, enabling faculty members to develop data-driven, tailored pedagogical models (Dwivedi et al., 2023). Based on the “Theory of Reasoned Action” (Fishbein and Ajzen (1975)), the two dimensions of TAM (PU and PEOU) can influence people’s behaviour toward technology adoption.

Furthermore, although existing literature has investigated LLM adoption via TAM and explored academic innovation separately, to the best of our knowledge, no prior research has integrated these domains to determine how technology acceptance’s cognitive antecedents (PU and PEOU) translate into multidimensional IWB. By showing that the perceived usefulness and ease of use of LLMs significantly predict opportunity exploration, idea generation, idea promotion, and reflective innovation in curriculum design, the study extends TAM into educational innovation, thus offering empirical evidence on how AI tools can drive transformative pedagogical practices. Furthermore, while previous studies have looked at the pedagogical aptitude of AI or TAM in isolation, the empirical integration of TAM factors (PU and PEOU) and the four IWB dimensions (OE, IG, IP, and Refl.) represents the primary theoretical contribution intended to seal this theoretical gap. Consequently, this work is both theoretically novel and highly practical for institutions aiming to leverage AI for enhanced curriculum development and faculty innovation.

PU signifies people’s belief that adopting a certain type of technology can enhance job performance (Davis, 1989). PU displays the performance expectations and the benefits of technology adoption (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). In the higher education context, when faculty members perceive LLM technologies as helpful for enhancing learning quality, curriculum development, and student teaching, they are more likely to adopt and creatively implement them (Kong et al., 2024; Messmann & Mulder, 2012) energetically. Recent research has argued that PU not only fosters technology acceptance but also drives innovative and proactive working (De Spiegelaere et al., 2014; Kparl & Iddris, 2024; Messmann & Mulder, 2012). When faculty members recognise that LLMs can streamline complex academic tasks, support knowledge discovery, and enable curriculum innovation, the perceived usefulness of these tools acts as a cognitive stimulus for a creative, opportunity-seeking attitude. This is consistent with Amabile’s (1988) “Componential Theory of Creativity”, which suggests that perceived capability and perceived task value (both related to usefulness) can stimulate internal drivers and innovation in the workplace. Likewise, “Social Cognitive Theory,” introduced by Bandura (1986), argues that outcome expectations can influence people’s behavioural participation. PU thus operates as an antecedent of innovative commitment, reshaping how faculty members can translate technological affordances into profound educational experiences (Wang et al., 2025; An et al., 2022). In the setting of employing LLM in curriculum design, PU is anticipated to positively influence the four main factors of IWB as initially suggested by Messmann and Mulder (2012)—namely, opportunity exploration (OE), idea generation (IG), idea promotion (IP), and reflection (Refl.). OE encompasses the recognition and pursuit of new opportunities for professional development (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). When faculty members perceive LLM tools as helpful in improving efficiency and the learning innovation process, they are more likely to discover novel pedagogical engagements (Dwivedi et al., 2023). Research has suggested that PU can encourage people to participate and learn new technologies (Kong et al., 2024; Rafique et al., 2022), confirming the assumption that PU can drive faculty members’ exploration of opportunities to use LLMs in curriculum development.

H1.

PU positively and significantly influences OE among faculty members adopting LLMs.

IG describes the development of new solutions or concepts for progressing the working processes (Kparl & Iddris, 2024). Studies have shown that when people perceive that technology tools are valuable for achieving their goals, they are more inclined to participate in creative problem-solving and idea generation (Kparl & Iddris, 2024). In educational contexts, PU has been exposed to maximise faculty members’ creative participation with technology and their commitment to advancing innovative teaching designs (Teo, 2011). Therefore, faculty members who perceive LLMs as an advantage are more likely to generate ideas that improve curriculum content and the student learning process.

H2.

PU positively and significantly influences IG among faculty members adopting LLMs.

IP comprises convincing others to defend and execute innovative ideas (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). Faculty members who recognise LLMs as a useful tool are not only more innovative but also more convinced of the need to defend their adoption within the university. PU has been linked with improved communication efficiency, advocacy for technological innovation, and collaboration (Imran & Kantola, 2020; An et al., 2022). The integration of GenAI, particularly LLMs, introduced a novel pattern of cognitive augmentation that basically improved the pathways between PU and creativity-related behaviors, such as IG and IP. Unlike traditional learning technologies or former rule-based AI systems, LLMs have the capacity to autonomously create comprehensive, domain-related, and contextual adaptive content, which functions as a prevailing cognitive incentive that supports creative thought functions. Recent studies revealed that GenAI systems can improve divergent thinking, widen cognitive search context, and facilitate intellectual abilities by offering users unexpected relationships, different framings, and rapid ideation creation (Franceschelli & Musolesi, 2025; Qu et al., 2024). In an academic setting, when faculty members perceive that LLM tools can significantly enhance academic outcomes, they become more proactive in fostering these tools among their colleagues and administrators.

H3.

PU positively and significantly influences IP among faculty members adopting LLMs.

Reflection (the last dimension of IWB) describes the process of assessing and learning from past experiences to enhance future practices (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). Faculty members who recognise LLMs as a useful tool are more willing to participate in reflective practices to improve their use of technology in learning and curriculum design. Research on e-learning adoption argues that PU can improve reflective engagement and continuous learning behaviours among faculty members (Wang et al., 2025; Kong et al., 2024). Perceiving LLMs as a beneficial tool can thus promote self-assessment and professional advancement, which can contribute to sustainable innovation.

H4.

PU positively and significantly influences reflection among faculty members adopting LLMs.

PEOU is the level to which people believe that adopting a certain technology will be free of physical and mental energy. PEOU is a main dimension of the TAM framework as introduced by Davis (1989). PEOU can minimise cognitive and procedural limitations to technology adoption, thus freeing people’s cognitive abilities for higher-order processes such as creative thinking, exploration, and reflective activities (Sweller, 1988). When faculty members view LLMs as easy to operate, they are more likely to practice with these AI tools, use employee tool results to inform pedagogical ideas, and enthusiastically foster and filter innovations in curriculum development. Social-cognitive views further argued that ease of use can improve self-efficacy and outcome expectancies, thereby stimulating innovative and proactive attitudes (Bandura, 1986). Previous empirical evidence in educational contexts suggested that PEOU can predict not only adoption intention but also subsequent innovative and creative practices (Huang et al., 2025; Teo, 2011; Zhao et al., 2024). OE needs sufficient time, high curiosity, and low resistance to practice with new AI tools and applications (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). Suppose an LLM is perceived as easy to use. In this case, faculty members are more likely to explore additional features, assess pedagogical reliability, and identify curriculum gaps that these AI technologies can address. Lower interaction costs and a shorter learning curve encourage exploratory experimentation (Kong et al., 2024; Rafique et al., 2022). Empirical evidence supported this assumption and indicated that perceived usability of AI tools is positively linked to exploratory use and the search for novel opportunities in the work environment (Spours, 2025; Wu et al., 2024).

H5.

PEOU positively and significantly influences OE among faculty members adopting LLMs.

IG depends on the cognitive resources applied for alternative thinking and analysis (Amabile, 1988). AI technologies that can reduce heavy interaction are more likely to free cognitive capacity for creative tasks (Sweller, 1988). Thus, when LLM platforms are intuitive, instructors can concentrate on ideas—adaptation, integration, and dissemination of machine-generated content into curriculum design innovations (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Kasneci et al., 2023). Previous research has examined the link between LLM use and innovation and found that PEOU can foster creative performance and idea creation in both educational and workplace settings (Mashhadi & Dehghani, 2025; An et al., 2022).

H6.

PEOU positively and significantly influences IG among faculty members adopting LLMs.

IP includes disseminating, persuading, and preparing support for innovative ideas (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). If faculty members find that LLM applications are easy to use, they are more positive and competent in practice demonstrations and provide evidence-based suggestions to support the adoption of LLMs among peers and supervisors (Tang et al., 2023; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). Ease of use also decreases resistance to discussing new ideas, maximising the willingness to champion innovative ideas (Wang et al., 2025). Previous research papers indicate that perceived usability increases users’ inclination to share, support, and implement AI technological innovations in the workplace (Börekci & Çelik, 2024; Davis, 1989; Hu et al., 2025; Mashhadi & Dehghani, 2025).

H7.

PEOU positively and significantly influences IP among faculty members adopting LLMs.

Reflection, as a dimension of IWB, is the deliberate assessment of practice to create learning and enhancement (Messmann & Mulder, 2012). Ease-of-use AI technologies can lower the procedural burden of practice and data collection, facilitating regular, focused reflection on learning outcomes and on how LLMs can contribute to achieving learning goals. Additionally, high PEOU can foster self-efficacy and willingness to participate in constant improvement loops (Bandura, 1986; Tierney & Farmer, 2011). Previous empirical evidence from the e-learning and educational technology literature indicates that PEOU can promote teachers’ reflective use of AI tools and ongoing pedagogical improvement (Ahmad Malik et al., 2025; Kong et al., 2024; Nissim & Simon, 2025).

H8.

PEOU positively and significantly influences faculty members’ reflection when adopting LLMs.

3. Research Methods

This study employed a hypothesis-testing quantitative research approach rooted in the positivist study paradigm to explore the associations between the use of LLMs and IWB in higher education curriculum development. A deductive strategy was used, whereby the research hypotheses were mainly derived from previous literature. Primary data were obtained through a structured survey administered with a cross-sectional research design. The proposed relationships were analysed by “Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling” (PLS-SEM), which is adequate for the prediction-oriented research design with multiple latent constructs and complex relationships.

3.1. Data Collection

The present paper used a quantitative, cross-sectional research approach to assess the impact of technology acceptance (PU, and PEOU) on the four main dimensions of IWB (IG, IP, OE, and Refl.) in the context of integrating LLMs into higher education curriculum design. The study targeted a sample of faculty members enrolled in public and private universities in the eastern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). The Eastern region was selected due to the intensity of higher education institutions and ongoing efforts toward digital transformation and AI adoption in the learning process. A convenience sampling method was used, an approach widely used in social and educational contexts when access to a whole population frame is not possible (Etikan et al., 2016). The sample included faculty members from numerous academic colleges and disciplines, safeguarding diversity in educational specialisation, academic rank, and practice level in AI learning technologies. While the study sample offers valuable insights into faculty adoption of LLMs within a swiftly modernising educational setting, caution is warranted when generalising the findings to regions with different levels of technological maturity. Future research papers should extend data collection to more regions to improve representativeness and strengthen its validity.

Data were gathered using a web-based survey designed in Google Forms to simplify participation and ensure secure contributions. The designed questionnaire was pilot tested with a group of 25 faculty members to ensure its clarity and the reliability and validity of the included measurement items. Very minor amendments were made based on participants’ feedback regarding the wording of the items. These amendments were confined to small wording improvements to expand clarity and readability without altering the real conceptual meaning of the variables. Examples involve modifying ambiguous words, simplifying phrase structure, and adjusting the consistency of terminology across variables (e.g., adding “for me” to the following original phrase “It is easy to integrate LLM-generated ideas into curriculum design.” It has been revised to “It is easy for me to integrate LLM-generated ideas into curriculum design.” for more clarity). The final version of the survey link was disseminated via institutional emails and academic or social networks (e.g., WhatsApp). Contribution to the survey was voluntary, and participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, with clear consent obtained at the beginning of the questionnaire. The online survey remained open for 4 weeks during the second semester of 2025. Participants were reminded three times through follow-up emails to improve response rates. A total of 493 valid replies were obtained after the exclusion of incomplete surveys. This sample size exceeds the suggested minimum requirements for PLS-SEM, which typically require at least 10 times the number of structural paths (32 paths in our study) pointing from the latent constructs (Hair et al., 2021a).

The final valid dataset (493) was collected from faculty members enrolled in five major universities in the Eastern Region of KSA: King Faisal University (38%), Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (26.7%), University of Hafr Albatin (14.4%), Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University (12.9%), and the Arab Open University (8%). Regarding the academic rank, the obtained sample included lecturers (27%), assistant professors (42%), associate professors (21%), and full professors (10.1%). In terms of discipline, participants were from diverse academic disciplines. The majority were from the social science discipline (60%), followed by the natural disciplines (40%). Furthermore, respondents had a wide range of teaching experience: 32% had <5 years, 38% had 5–10 years, and 30% had >10 years.

3.2. Measures

In this study, the researcher derived the questionnaire items from previously validated and tested empirical studies. Technology acceptance was operationalised into two dimensions based on the TAM developed by Davis (1989). Each of the two dimensions (PU and PEOU) of the TAM scale has six reflective items. A sample item of PU is “LLMs help me make better, data-informed decisions in curriculum planning”. Likewise, a sample item of PEOU is “It is easy for me to integrate LLM-generated ideas into my curriculum design”. Furthermore, four dimensions were employed to measure IWB, as described by Messmann and Mulder (2012). The four reflective dimensions are EO (four items), of which a sample item is “I attend workshops or webinars to stay informed about innovations in curriculum development”; IP (seven items), of which a sample variable is “I lead discussions on the potential impact of LLMs on teaching methodologies in faculty meetings”; IG (six items), where a sample item is “I suggest innovative teaching methods that incorporate LLMs to improve student engagement.”; and reflection (three items), where a sample item is “I reflect on personal teaching practices to identify areas for further integration of LLMs”. Questions were assessed based on a five-point Likert scale, where (strongly disagree = 1) and (strongly agree = 5).

3.3. Common Method Bias (CMB) Analysis

The independent and dependent questionnaire items were collected by the same respondent (a faculty member), thus CMB may be a concern in this study (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To resolve this issue, “Harman’s single factor” analysis was conducted. The results indicated that the unrotated one-factor extraction option explained 39% of the variance, which is below the suggested cutoff of 50%. These results give evidence that CMB cannot affect the scale validity. Furthermore, the “variance inflation factor” (VIF) values for all the scale items were <5, as depicted in Table 1. These results indicated that neither multicollinearity concern nor CMB issue posed a critical problem in this study (Lindell & Whitney, 2001).

Table 1.

Outer model results.

Harman’s single-factor test is a relatively weak diagnostic of CMV and, on its own, cannot offer an adequate explanation that CMV is not a serious issue. Accordingly, more robust procedures, such as f2 effect sizes and bootstrapped confidence intervals (see Table 2), are recommended.

Table 2.

Bootstrapping confidence intervals and f2 results.

The bootstrapped confidence intervals offer additional evidence that CMV is unlikely to be a serious issue in this study. Across all structural paths, the 95% confidence intervals are stringently positive (e.g., PEOU → IG: 0.178–0.349; PEOU → reflection: 0.165–0.326; PU → IP: 0.522–0.630; PU → reflection: 0.545–0.691), implying that the impacts remain statistically significant on repeated resampling and are not reliant on a single sample. This outline is inconsistent with the expectation that substantial CMV would produce unstable estimates and confidence intervals that tend to widen and cross zero, thereby undermining the robustness of the relationships (Kline, 2015; Podsakoff & Organ, 1986).

The results of f2 scores offered more evidence that the structural relationships in the study model are not mainly driven by CMV. According to the recommended threshold, f2 scores of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988; Hair et al., 2021b). In the current findings, paths from PEOU to the four dimensions of IWB show small effects (f2 = 0.088–0.137), whereas paths from PU displayed medium-to-large effects (f2 = 0.315–0.685). This differentiation in effect size magnitudes across constructs implies that variance in the endogenous variables is not uniformly inflated by a single method factor (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

4. Study Results

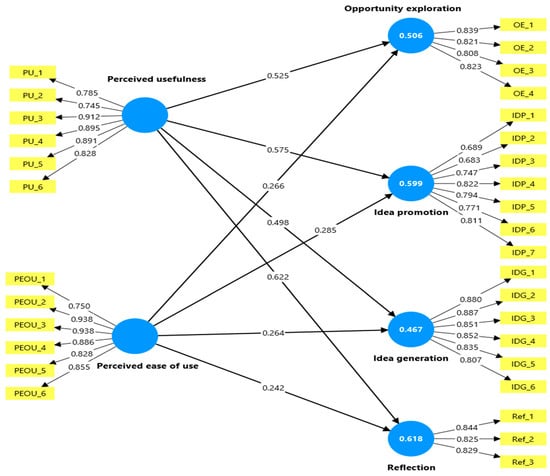

Given the exploratory and predictive nature of this research, PLS-SEM was used as the primary analytical technique rather than the more commonly employed traditional covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) methods (Leguina, 2015). PLS-SEM is particularly well-suited for research that focuses on predicting key target dimensions and exploring complex theoretical interrelationships rather than on accurate model confirmation (Hair et al., 2019). Unlike CB-SEM, which must meet model fit criteria before theory testing and requires strict assumptions of normality and large sample sizes, PLS-SEM offers greater flexibility by handling non-normal data distributions and can deal with smaller to medium sample sizes (Sarstedt et al., 2021). PLS-SEM was adopted following well-established procedures for model specification, estimation, and reporting. To improve clarity and reproducibility, the modelling workflow is depicted as an algorithmic chain of steps. First, the conceptual model was defined by specifying two exogenous technology-acceptance constructs (PU and PEOU) and four endogenous innovation outcomes in curriculum design (IG, IP, OE, and reflection). Each dimension was operationalized as a reflective latent unobserved variable with multiple items adapted from prior studies (as detailed in the Measurement Section 4.1). Second, the dataset was cleaned (detecting any missing values, normality, and outliers), and the final dataset was inserted into the PLS-SEM software V4, where both the measurement and structural models were specified using the path diagram shown in Figure 1, The data analysis was run employing SmartPLS software version. 4. The analysis was conducted in two stages as recommended by (Henseler et al., 2009): (1) the evaluation of the measurement model, assessing reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the study constructs; and (2) the assessment of the structural model, investigating the study hypotheses and the explanatory power (R2) for each endogenous dimension. More specifically, the empirical procedure can be structured following the pseudo-algorithm. This approach specifies the inputs (constructs, indicators, sample size, software version, and bootstrap settings), outputs (loadings, path coefficients, R2, f2, confidence intervals), and decision rules, thereby allowing other scholars to replicate the study model with comparable data and software.

Figure 1.

The research model.

4.1. Measurement Model (Stage One)

As depicted in Table 1 and presented in Figure 1, all standardised factor loadings (SFL) were extended from 0.638 to 0.936, beyond the recommended minimum score of 0.60 as argued by Hair et al. (2012), “Composite Reliability” (CR) was assessed employing Chin’s (1995) method, which is precisely fits PLS-SEM, to assess internal consistency reliability. Both “CR and Cronbach’s alpha” values for factors were found to exceed the score of 0.70, confirming adequate internal consistency, as presented in Table 1. To evaluate construct validity (convergent and discriminant validity), we reviewed the “Average Variance Extracted” (AVE) per Hair et al.’s (2012) recommendations; an AVE score of 0.50 supports proper convergent validity. As shown in Table 1, all AVE values exceed this benchmark, confirming that the measurement scale has a good convergent validity. Discriminant validity was evaluated using three criteria: (1) “heterotrait–monotrait” (HTMT) ratio presented in Table 3, Fornell–Larcker criterion depicted in Table 4, and Table 5 cross-loadings assessment in Table 5. Following Chin (1995), HTMT scores should be below the value of 0.90. As depicted in Table 3, all factors showed an HTMT value below this benchmark, confirming a satisfactory discriminant validity. Additionally, as presented in Table 4, the square root of AVE for each dimension was compared with its correlation with all other factors in the study. The outcomes in Table 4 showed that the diagonal numbers (square roots of the AVE) for all constructs exceeded their inter-construct correlations, supporting good discriminant validity. Furthermore, the cross-loading output in Table 5 showed that each factor loading for all items is highly loaded on its predetermined dimension as compared to other dimension which gives additional support for adequate discriminant validity (Leguina, 2015).

Table 3.

HTMT matrix.

Table 4.

Fornell–Larcker matrix.

Table 5.

Cross-loading scores.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing Results

Before testing the research hypotheses, the model’s predictive capability was assessed using two key indicators: the coefficient of determination (R2) and the Stone–Geisser’s Q2 criterion (Hair et al., 2017). As illustrated in Figure 1, the two exogenous TAM constructs (PU and PEOU) jointly accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance across the four IWB dimensions. Particularly, the model explained 50.6% of the variance in OE, 59.9% in IP, 46.7% in IG, and 61.8% in reflection (Refl.). In addition, the Q2 values, which assess cross-validated redundancy through the blindfolding procedure, were all greater than zero for the endogenous constructs (IG, Q2 = 0.459; IP, Q2 = 0.593; OE, Q2 = 0.497; Ref, Q2 = 0.612). These positive Q2 values confirm that the model has adequate predictive relevance, demonstrating its robustness and reliability in explaining and forecasting faculty members’ innovative behaviours in the context of LLM integration in higher education.

The study model has eight direct hypotheses. To calculate statistical significance, a bootstrapping option in PLS-SEM with 5000 resamples was used, as per Hair and Alamer’s (2022) recommendations. The PLS-SEM results, comprising the path coefficients (β), related to t-statistics (t), and significance levels (p), are pictured in Figure 1 and presented in Table 6 to decide whether to accept or reject the tested hypothesis.

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing results.

As presented in Table 6 and depicted in Figure 1, all eight direct hypotheses were supported. Precisely, perceived usefulness (PU), as a dimension of technology acceptance, was found to have a direct, positive, and significant impact on the four dimensions of innovative work behaviour among faculty members adopting LLMs. More specific, PU showed a strong positive significant impact on OE (β = 0.525, t = 9.197, and p < 0.001), IP (β = 0.575, t = 20.924, and p < 0.001), IG (β = 0.498, t = 10.398, and p < 0.001) and reflection (β = 0.622, t = 16.731, and p < 0.001), supporting H1, H2, H3 and H4. Likewise, PEOU, as a dimension of technology acceptance, showed a strong positive significant impact on OE (β = 0.266, t = 4.655, and p < 0.001), IP (β = 0.285, t = 8.352, and p < 0.001), IG (β = 0.264, t = 6.083, and p < 0.001) and reflection (β = 0.242, t = 5.904, and p < 0.001), supporting H5, H6, H7, and H8. It is worth noting that, although all eight proposed hypotheses were confirmed, the results demonstrate that PU is the dominant driver of IWB among faculty members adopting LLMs. Across all four IWB dimensions, PU showed a substantially higher path coefficient (β = 0.622) than PEOU. This pattern underscored that faculty members’ IWBs are driven mainly by the PU and real value of LLMs rather than by PEOU alone.

5. Discussion and Implications

The results of this paper revealed that perceived usefulness (PU), as a main dimension in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), has a positive and direct significant relationship with all four factors of innovative work behaviour (IWB) among faculty members integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) into university education curriculum design. More specifically, PU was found to have a strong influence on opportunity exploration (OE), idea promotion (IP), idea generation (IG), and reflection. These findings provide empirical support for hypotheses H1 through H4 and emphasise the key role of perceived technological value in promoting faculty members’ innovation. These results align consistently with TAM (Davis, 1989) which argued that people’s perceptions of technology’s usefulness can significantly reshape their behavioural commitment and performance outcomes. Those faculty members who view LLMs as beneficial tools for improving their teaching efficiency, curriculum development, and decision-making are more likely to explore new pedagogical opportunities and participate in creative, reflective innovation procedures. These results supported earlier studies in educational technology that argued that PU can play a predictive role in shaping educators’ technology-driven participation and innovative learning behaviours (Kong et al., 2024; Rafique et al., 2022; Teo, 2011).

From a psychological perspective, these relationships can be partially explained through “Amabile’s Componential Theory of Creativity” (Amabile, 1988), which suggests that both intrinsic motivation and perceived task value (both associated with PU) are dominant factors in the creativity and innovation process. When faculty members recognise that LLMs can meaningfully enhance their work outcomes (i.e., facilitating content development, improving student evaluation, or promoting research), they are more likely to invest in emotional and cognitive resources to generate and encourage novel ideas. Correspondingly, “Social Cognitive Theory” (Bandura, 1986) argued that people can act innovatively when they expect positive performance consequences from using such a tool or skill, findings consistent with the current findings supporting the positive influence of PU on the four IWB factors. The strong, positive, significant impact of PU on idea promotion and reflection specifically indicated that perceived usefulness not only energises creative ideation but also fosters confidence and engagement in executing innovations. These results align with the findings of An et al. (2022), who argued that perceived performance outcomes from digital AI tools can improve both the encouragement of innovation and reflective evaluation of work procedures. Likewise, the strong predictive power in this paper revealed that PU can operate as a cognitive driver for innovation and workplace creativity (Imran & Kantola, 2020).

The results also revealed that PEOU, one of the main elements of TAM, showed a strong, significant, and positive relationship with all four dimensions of IWB: opportunity exploration (OE), idea promotion (IP), idea generation (IG), and reflection. These findings offer strong evidence in support of hypotheses H5 through H8, indicating that when faculty members recognise LLM-based methods as easy to use, they are more likely to engage in a reflective, innovative academic performance. The significant and positive associations of PEOU with all four dimensions of IWB align with the foundational premise of the TAM (Davis, 1989), which argues that perceived ease of use can increase people’s willingness to adopt and practice a technology. In this context, when educators perceive that adopting LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT) requires nominal cognitive effort, they are more likely to search for new learning opportunities, create innovative curricular designs, and react to how AI tools can be integrated into pedagogical experiences.

These findings are aligned with previous studies confirming that PEOU can enhance user self-confidence, reduce technological stress, and advance intrinsic motivation (all of which can influence creative engagement and innovative practices). Teo (2011) and Venkatesh and Davis (2000) stated that when educators confront simple, intuitive applications, they can develop convincing behavioural intentions toward technology-based innovation. Similarly, An et al. (2022) claimed that the ease of incorporating digital learning tools can significantly influence learners’ innovative curriculum design by fostering self-efficacy and minimising change resistance. The link from PEOU, idea generation, and reflection is remarkably aligned with “Self-Determination Theory,” which is introduced by Deci and Ryan (2012), and argues that independence and recognised competence can foster creative participation. When faculty members feel that LLMs are easy to use and require very limited technical skill, they feel more self-sufficient and qualified, which fosters their willingness to practice, reflect, and iterate on new educational tools.

The stronger influence of PU over PEOU in predicting IWB can be understood through the motivational demands of innovative behaviours. IWB incorporates cognitively intensive and proactive behaviours such as creating novel ideas, promoting them within the organisation, and reflecting critically on learning practices. These behaviours necessitate substantial psychological effort and commitment, making outcome expectations a central driver. Drawing on Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986) and expectancy-value models (Vroom, 1964), PU acts as a powerful motive that aligns with faculty members’ aspirations to obtain meaningful academic results. In contrast, PEOU primarily minimises cognitive load but does not, by itself, offer sufficient motivational pressure to engage in complex, change-oriented behaviours. Therefore, faculty are more likely to be involved in IWB when they perceive LLMs as a means that creates tangible, high-value advantages, which can explain the consistently larger path coefficients (β = 0.622) detected for PU across all IWB factors.

From a theoretical perspective, this paper has sought to extend the TAM by integrating IWB, demonstrating that technology usefulness and ease of use can predict different levels of the innovation process, from opportunity exploration and idea generation to idea promotion and reflection. While TAM has been commonly employed to predict adoption behaviour, few studies have empirically linked it to behavioural consequences reflecting enduring innovation (Dwivedi et al., 2023). This paper thus contributed to sealing this theoretical gap, specifically in the emerging setting of AI and LLM implementation in the education environment. Likewise, the findings support the argument that PU and PEOU are not a reactive belief, but a proactive enabler of innovation (a tool through which technology acceptance can be transformed into a creative and reflective working behaviour). By giving empirical evidence that validates the link between TAM and IWB, this paper offered a base for trying to develop a holistic and comprehensive models that explain the psychological and behavioural pathways through which digital AI tools can foster academic innovation.

From a practical standpoint, the results provide valuable insights for university managers and policymakers seeking to foster a helpful integration of LLMs and other AI-based tools into the higher education context. First, university leaders’ efforts should focus on maximising the perceived usefulness of LLM tools by clearly demonstrating their capacity to enhance learning quality, curriculum design, and research innovation. This could be accomplished by organising workshops and training sessions that demonstrate how LLMs can minimise routine workload, improve content validity, and accelerate innovative pedagogical development (Kasneci et al., 2023). Second, given the strong, significant impact of PU and PEOU on IP, IG, OE, and reflection, policymakers in higher education in KSA should develop an educational environment that rewards innovative ideas and reflective learning practices. Designing innovative research or curriculum grants, multidisciplinary AI learning labs, or “faculty members’ innovation circles” might foster shared reflection, idea generation, and promotion. Finally, university leaders should ensure that university technology resources meet faculty members’ needs to enhance the perceived value of LLM tools. As previous research indicates, training sessions that focus on pedagogical and technological content simultaneously improve both PU and ensuing innovative behaviour (Kong et al., 2024).

It is worth noting that this study is classified mainly as an explanatory, variance-based paper of TAM and IWB in the employment of GenAI for curriculum development, rather than as an algorithmic optimisation system that can be benchmarked using standard performance metrics such as accuracy or precision. Existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) papers on AI-enhanced curriculum development mainly focused on technical architectures that create, adapt, or categorise learning content and assess them employing metrics such as student learning benefits, involvement indicators, or efficiency improvements in curriculum design workflows (e.g., Li, 2025; Wong & Looi, 2024; Neendoor, 2024). By contrast, the current study employed PLS-SEM to estimate how PU and PEOU of GenAI relate to four dimensions of instructors’ IWB in curriculum design (IG, IP, OE, and reflection), with path coefficients, effect sizes (f2), and explained variance (R2) as key outcomes (Hair et al., 2021b; Sarstedt et al., 2021). Although this design did not allow a direct benchmarking against methodical SOTA tools, it can offer a complementary influence by quantifying the behavioural and psychological mechanisms through which GenAI tools are likely to exert impact in higher-education curriculum development and by offering empirically grounded effect sizes that can act as behavioural weights in forthcoming optimisation-oriented SOTA models.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Like any other study in the social sciences, the current study has several limitations that should be acknowledged to inspire future research. First, a cross-sectional research design was adopted, which might limit the ability to establish causal inferences between the research variables. Future research can adopt a longitudinal design to track changes in faculty members’ innovation behaviours over a more extended period, with LLMs integrated into the academic context. Second, the study sample was obtained from faculty members at Eastern Region universities in KSA, which might not fully account for cultural variations across other regions in KSA. A future research paper could extend the geographic coverage to include additional areas. Additionally, future research might investigate mediating (i.e., self-efficacy, digital trust, or institutional support) or moderating variables that provide a more detailed explanation of how and when technology acceptance predicts IWB, such as year of experience—already captured in the current sample—may play a critical moderation role in shaping whether PU translates into higher levels of IG, IP, and reflection. More experienced faculty members might either leverage LLMs more strategically due to larger pedagogical knowledge or adopt them more cautiously due to rooted teaching routines. Finally, a comparative multigroup analysis between LLM users and non-users could emphasise the transformative possibility and ethical considerations of AI tools in the academic work setting.

7. Conclusions

This paper explored the impact of TAM’s two constructs (PU and PEOU) on the four dimensions of IWB among faculty members employing LLMs in their higher education curriculum design. The PLS-SEM report of the valid responses from 493 faculty members enrolled in five KSA universities located in Eastern Region showed that PU and PEOU can have a positive and significant impacts the four dimension on the four dimensions of IWB (OE, IG, IP, and Refl.). These results underlined that when faculty members perceive LLMs tools as valuable and easy to use, they are more inspired to participate in an innovative curriculum design process. From a theoretical viewpoint, this study tried to extend the TAM by offering empirical evidence that links its two factors to a multidimensional innovation consequence, thus supporting that technology acceptance can act as a cognitive antecedent of IWB. This study further bridged the gap between the TAM and workplace innovation studies, contributing to the nuanced understanding of how AI-based applications can foster reflective and creative participation in the academic environment. Practically, the study offered actionable steps for university leaders and policymakers. Improving faculty members’ perceptions of LLM tools’ usefulness and ease of use through targeted training sessions, peer support networks, and university motivation can hasten digital innovation in curriculum design.

To this end, the paper offered more than empirical insights into faculty members’ acceptance and innovative usage of LLMs. The study provided an initial framework to guide higher education organisations as they navigate the accelerating shift to AI-driven curriculum transformation. By explaining the behavioural and psychological mechanisms that shape faculty members’ engagement with GenAI, the paper supported higher education institutions in developing evidence-based policies that encourage meaningful, future-ready pedagogical innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.; methodology, I.A.E.; software, I.A.E., M.A., C.K. and A.M.S.A.; validation, I.A.E.; formal analysis, I.A.E.; investigation, I.A.E.; resources, I.A.E.; data curation, I.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.E., M.A., C.K. and A.M.S.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A.E.; visualization, I.A.E.; supervision, I.A.E.; project administration, I.A.E.; funding acquisition, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Project No. KFU260358].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (Approval code KFU260358), with the approval granted on 25 July 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad Malik, I., Ahmyaw Adem, S., & Rasool, A. (2025). Understanding the adoption of educational AI tools in Sub-Saharan African higher education: A theory of planned behaviour-based analysis. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2546126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- An, F., Xi, L., Yu, J., & Zhang, M. (2022). Relationship between technology acceptance and self-directed learning: Mediation role of positive emotions and technological self-efficacy. Sustainability, 14(16), 10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Belda-Medina, J., & Kokošková, V. (2024). ChatGPT for language learning: Assessing teacher candidates’ skills and perceptions using the technology acceptance model (TAM). Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börekci, C., & Çelik, Ö. (2024). Exploring the role of digital literacy in university students’ engagement with AI through the technology acceptance model. Sakarya University Journal of Education, 14(2), 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., Meitar, R., & Weisberg, J. (2006). Self-leadership skills and innovative behavior at work. International Journal of Manpower, 27(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1995). Partial least squares is to LISREL as principal components analysis is to common factor analysis. Technology Studies, 2(2), 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences [Internet]. L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 416–436). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- De Spiegelaere, S., Van Gyes, G., De Witte, H., Niesen, W., & Van Hootegem, G. (2014). On the relation of job insecurity, job autonomy, innovative work behaviour, and the mediating effect of work engagement. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(3), 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., & Wright, R. (2023). So what if ChatGPT wrote it? Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges, and implications of generative conversational AI. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., AlNajdi, S. M., & Salem, M. A. (2025). Measuring the impact of large language models on academic success and quality of life among students with visual disability: An assistive technology perspective. Bioengineering, 12(10), 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 10(2), 130–132. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/fisbai?all_version (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Franceschelli, G., & Musolesi, M. (2025). On the creativity of large language models. AI & Society, 40(5), 3785–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizani, S., Mazhar, T., Shahzad, T., Ahmad, W., Bibi, A., & Hamam, H. (2025). A systematic literature review to implement large language model in higher education: Issues and solutions. Discover Education, 4(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., & Alamer, A. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021a). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021b). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics, & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing (Vol. 20, pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., Wang, H., & Xin, Y. (2025). Factors influencing Chinese pre-service teachers’ adoption of generative AI in teaching: An empirical study based on UTAUT2 and PLS-SEM. Education and Information Technologies, 30(9), 12609–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C., Tsai, H.-J., Liang, H.-T., Chen, B.-S., Chu, T.-H., Ho, W.-S., Huang, W.-L., & Tseng, Y.-J. (2025). Development of an automotive electronics internship assistance system using a fine-tuned llama 3 large language model. Systems, 13(8), 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M. K., & Kantola, J. (2020). Review of industry 4.0 in the light of sociotechnical system theory and competence-based view: A future research agenda for the human dimension. Technology in Society, 63, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., & Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, S. C., Yang, Y., & Hou, C. (2024). Examining teachers’ behavioural intention of using generative artificial intelligence tools for teaching and learning based on the extended technology acceptance model. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kparl, E. M., & Iddris, F. (2024). Factors influencing the adoption of chatgpt for innovation generation: A moderated analysis of innovation capability and gender using utaut2 framework. Global Scientific and Academic Research Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 3(12), 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, A. (2015). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. (2025). AI-enhanced curriculum design and deep-learning-based assessment in international sports communication education. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE), 21(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi, A., & Dehghani, H. (2025). Examining knowledge management factors in college students’ acceptance of engineering language MOOCs: An extended TAM approach. European Journal of Education, 60(4), e70253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmann, G., & Mulder, R. H. (2012). Development of a measurement instrument for innovative work behaviour as a dynamic and context-bound construct. Human Resource Development International, 15(1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neendoor, S. (2024, November 23). AI & curriculum: The shocking impact you need to know! Digital Engineering & Technology|Elearning Solutions|Digital Content Solutions. Available online: https://www.hurix.com/blogs/four-proven-metrics-to-assess-ais-impact-on-curriculum-design/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Nissim, Y., & Simon, E. (2025). The diffusion of artificial intelligence innovation: Perspectives of preservice teachers on the integration of ChatGPT in education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 51(2), 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F., Zheng, L., & Jiao, P. (2022). Artificial intelligence in online higher education: A systematic review of empirical research from 2011 to 2020. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 7893–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Du, P., Che, W., Wei, C., Zhang, C., Ouyang, W., Bian, Y., Xu, F., Hu, B., & Du, K. (2024). Promoting interactions between cognitive science and large language models. The Innovation, 5(2), 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafique, H., Almagrabi, A. O., Shamim, A., Anwar, F., & Bashir, A. K. (2022). Investigating the acceptance of mobile library applications with an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Computers & Education, 182, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J., Tan, S., & Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT and the future of assessment in higher education. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research (pp. 587–632). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Spours, K. (2025). Socialized systems of generative artificial intelligence and the roles of technological organic intellectuals. Systems, 13(11), 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Zainal, S. R. B. M., & Li, Q. (2023). Multimedia use and its impact on the effectiveness of educators: A technology acceptance model perspective. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. (2011). Factors influencing teachers’ intention to use technology: Model development and test. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2432–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2011). Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M., Chen, Z., Liu, Q., Peng, X., Long, T., & Shi, Y. (2025). Understanding teachers’ willingness to use artificial intelligence-based teaching analysis system: Extending TAM model with teaching efficacy, goal orientation, anxiety, and trust. Interactive Learning Environments, 33(2), 1180–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. H., & Looi, C. K. (2024). Advancing the generative AI in education research agenda: Insights from the Asia-Pacific region. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 44(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Zhang, S., Ma, Z., Yue, X.-G., & Dong, R. K. (2024). Unlocking potential: Key factors shaping undergraduate self-directed learning in AI-enhanced educational environments. Systems, 12(9), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Sha, L., Zhao, L., Li, Y., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Chen, G., Li, X., Jin, Y., & Gašević, D. (2024). Practical and ethical challenges of large language models in education: A systematic scoping review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(1), 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q., Chen, Y., & Liang, J. (2024). Attitudes and usage patterns of educators towards large language models: Implications for professional development and classroom innovation. Academia Nexus Journal, 3(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.