Abstract

Workplace behaviors and employee outcomes, such as team functioning, job satisfaction, and intentions to leave, are crucial for healthcare quality and safety. It highlights the substantial productivity, societal, and economic costs of worker well-being. Against this backdrop, this study examines how two dimensions of organizational culture: ethical climate and perceived managerial competence, together with team support, relate to job satisfaction and turnover intention among healthcare professionals. A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was conducted with 430 physicians, nurses, and other clinical staff in public and private institutions across the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Using established scales and structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS, we first verified satisfactory reliability and construct validity via exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The structural model showed that ethical organizational culture and managerial competence are positively related to team support and, directly or indirectly, to higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intention. Team support was positively related to job satisfaction and negatively related to turnover intention and significantly mediated the effects of both ethical climate and managerial competence on these outcomes. In addition, job satisfaction was strongly and negatively correlated with turnover intention, underscoring its central role in retention.

1. Introduction

High-quality patient care depends not only on clinical expertise and technology, but also on the ability of healthcare organizations to retain skilled professionals and support their well-being. Persistent shortages of healthcare staff, combined with high turnover intention, threaten service continuity, increase recruitment and training costs, and undermine employee well-being. In this context, understanding why healthcare workers choose to stay or leave has become a strategic priority for managers, policymakers, and researchers. While individual factors such as personal resilience or career goals play a role, a growing body of evidence shows that employees’ decisions are strongly shaped by how they experience their organizational environment and culture, and by the extent to which that environment supports psychological safety and well-being. One important part of the internal environment in healthcare organizations is organizational culture, understood as a system of shared norms, values, assumptions, and persistent ways of working that are transmitted to new members and guide “how we do things here” (Akhavan et al., 2014; Schein, 2010). In the literature, organizational culture is typically treated as a multidimensional construct, with dimensions such as managerial competence, workload pressure, cohesion, organizational boundaries, and ethics (Hornsby et al., 2002; Rogg et al., 2001; Schwepker, 2001). Building on these dimensions, we focus on two theoretically silent dimensions: ethics and perceived managerial competence. Ethics, introduced by Victor and Cullen (1988), refers to employees’ shared perceptions of what constitutes right behavior and how ethical issues are handled in the organization. In healthcare, an ethical organizational culture is reflected in fair decision-making, openness to discussing ethical concerns, and consistent support for patient-centered values, which foster trust and psychological safety among staff (Santiago-Torner, 2025). Recent studies and reviews suggest that such climates are associated with higher job satisfaction (Xia et al., 2024), lower job-related stress (Jentsch et al., 2023), reduced moral distress, and reduced turnover intention among nurses and other health professionals (Ammari & Gantare, 2025). On the other hand, managerial competence reflects staff views of their manager’s ability to communicate, support, and fairly allocate work (Rogg et al., 2001). At the same time, the competency tradition in management research highlights managerial competence as a crucial factor of a healthy work environment (Boyatzis, 1993; McClelland, 1973; Woodruffe, 1993).

In independent care teams, feeling supported by colleagues fosters psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999; O’donovan & Mcauliffe, 2020) and is associated with more positive attitudes, higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intentions. Reviews in healthcare consistently show that organizational and coworker support are associated with higher job satisfaction (Griffin et al., 2001), and with lower burnout, stress, and turnover intention (Hebles et al., 2022). Ethical climate also predicts greater job satisfaction (Nugroho & Muafi, 2021), often via trust among colleagues (Li et al., 2022). Healthcare work is inherently team-based, delivered through interdependent multidisciplinary teams in which coworker support represents a critical social resource (Albarqi, 2024; House, 1981). In this line of research, job satisfaction is typically defined as a positive emotional evaluation of one’s job (Locke, 1976), whereas turnover intention, grounded in classic turnover models (March & Simon, 1958; Mobley, 1977; Mobley et al., 1979; Tett & Meyer, 1993) reflects employees’ conscious and deliberate willingness to leave the organization. Despite extensive work on ethical climate, leadership and support in healthcare, several important gaps remain. Many studies consider these constructs in isolation, focusing on ethical climate or leadership style alone, without modeling how specific dimensions of organizational culture, ethics, and managerial competence jointly shape staff outcomes. Second, the potential role of team support as a mechanism through which these cultural dimensions influence job satisfaction and turnover intention has been unexplored; mediation by team-level processes is often assumed but rarely tested explicitly in a single structural model. Moreover, empirical evidence that integrates these variables into one model remains limited in under-researched healthcare systems facing resource constraints and high workforce pressures.

To address these gaps, the present study proposes an integrated framework in which organizational culture (ethics and managerial competence) and team support act as key job resources that foster psychological safety and employee well-being, thereby shaping job satisfaction and turnover intention among healthcare professionals. Specifically, we examine (1) whether ethical organizational culture and perceived managerial competence are associated with higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intention, (2) whether team support is positively related to job satisfaction and negatively related to turnover intention, and (3) whether team support mediates the relationships between organizational culture and these outcomes. By testing this framework using structural equation modelling, this study contributes to behavioral science research on workplace behavior by (a) jointly modelling ethical climate and managerial competence as distinct cultural resources, (b) clarifying the mediating role of team support, and (c) extending evidence on staff retention to an understudied healthcare context.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Organizational Culture in Healthcare: Ethics and Managerial Competence

In line with organizational culture research in healthcare, we treat ethical climate and perceived managerial competence as two key dimensions of the broader organizational culture, rather than as a single undifferentiated culture construct. Each dimension captures a specific facet of how staff experience their work environment: shared ethical norms on the one hand, and day-to-day managerial behavior on the other.

Ethical climate, originally defined by Victor and Cullen (1988) as employees’ shared perceptions of appropriate behavior and the handling of ethical issues, is particularly salient in healthcare, where professionals routinely face value conflicts and resource constraints. Studies and systematic reviews in nursing and bioethics show that more positive ethical climates, characterized by fair procedures, openness to ethical concerns, and support for patient-centred values, are generally associated with higher job satisfaction, lower moral distress, and reduced turnover intention among health professionals (Ammari & Gantare, 2025; Kim et al., 2023; Victor & Cullen, 1988). Ethics is also discussed as a source of organizational legitimacy and long-term sustainability (Caldeira & Infante-Moro, 2025).

The managerial competence dimension builds on the competency tradition in management research, which views competencies as underlying characteristics linked to effective performance (Boyatzis, 1993; McClelland, 1973) and as observable behaviors in key managerial roles (Woodruffe, 1993). In the healthcare literature, perceived competence of nurse managers, reflected in how they staff units, manage resources, communicate, and support development, has been linked to higher job satisfaction and lower intention to leave among clinical nurses (Mirzaei et al., 2024). In this study, we therefore treat ethical climate and perceived managerial competence as analytically distinct but related dimensions of organizational culture that jointly shape how healthcare workers experience their institutions.

2.2. Team Support

The construct of team support builds on the broader literature on social support at work (House, 1981) and perceived organizational support (Eisenberger et al., 1986), which was later distinguished between support from the organization, supervisors, and co-workers. In healthcare, where work is organized through interdependent teams exposed to time pressure, high emotional load, and frequent ethical dilemmas, support from colleagues is not just a generic resource but a buffer against moral distress, role overload and isolation. Integrative reviews and empirical studies indicate that coworker and organizational support are positively associated with job satisfaction and intention to stay, and negatively associated with stress and turnover intention (Liu et al., 2025). In this study, we therefore conceptualize team support as a team-level construct that shapes how the broader organizational culture (ethics and managerial competence) is translated into individual attitudes.

2.3. Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention in Healthcare

The concept of job satisfaction has its roots in early organizational psychology (Hoppock, 1935) and is commonly defined following Locke (1976) as a positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences (Locke, 1976). In healthcare settings, this appraisal is strongly shaped by factors such as workload intensity, perceived fairness in staffing and scheduling, opportunities for professional development, quality of interprofessional relationships, and exposure to ethical conflict. On the other hand, the concept of turnover intention is grounded in classic turnover models (March & Simon, 1958; Mobley, 1977; Mobley et al., 1979) and is commonly defined, following Tett and Meyer (1993), as employees’ conscious and deliberate willingness to leave their organization (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Meta-analyses and systematic reviews consistently identify job satisfaction as one of the strongest predictors of nurses’ turnover intention (Kim & Kim, 2021), yet they also show that the magnitude of this link depends on contextual factors such as labor market alternatives, contract security, and perceived organizational support (O’Callaghan & Sadath, 2025). Our framework builds on this literature by treating job satisfaction and turnover intention as key attitudinal outcomes through which ethical climate, managerial competence, and team support may influence retention-relevant behavior.

2.4. Hypothesis Development

2.4.1. Organizational Culture and Team Support

From a job-resource and psychological-safety perspective, ethical climate and perceived managerial competence can be seen as relatively distal features of organizational culture that shape how teams function on a daily basis (Shadur et al., 1999). Shared norms of fairness and integrity signal that speaking up and helping colleagues is safe and worthwhile, while competent managers provide clarity, protect staff from undue blame, and model collaborative behavior (Eva et al., 2020; Swalhi et al., 2023). These cultural cues make it more likely that team members will exchange practical and emotional support in managing heavy clinical workloads (Açıkgöz & Günsel, 2011; Maffoni et al., 2020). We therefore expect that a stronger ethical climate and higher perceived managerial competence will be associated with greater team support.

H1.

Organizational Culture is positively associated with Team Support.

2.4.2. Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction

Job resources such as fair management, ethical norms, and supportive colleagues foster motivation and positive attitudes, including job satisfaction (Jankelová et al., 2023). In healthcare, where work is interdependent and emotionally demanding, ethical and competent management can provide structure, predictability, and recognition (Paksoy et al., 2017), while team support helps staff cope with workload and uncertainty at the bedside (Griffin et al., 2001). These resources are likely to shape how professionals appraise their jobs across domains such as workload, relationships, and perceived value. Accordingly, we expect that both organizational culture and team support will be positively related to job satisfaction.

H2.

Organizational Culture is positively associated with Job Satisfaction.

H3.

Team Support is positively associated with Job Satisfaction.

2.4.3. Ethics, Team Support and Turnover Intention

Classic turnover models suggest that when employees experience their organization as fair, predictable, and supportive, they feel less strain and are less inclined to consider leaving (Joe et al., 2018; Suwaidan et al., 2022). In healthcare, ethical norms (e.g., transparent decision-making, intolerance of unethical practices) and competent management (e.g., fair workload allocation, clear communication) can reduce frustration and moral distress, while supportive teams buffer stress and foster belonging (Abou Hashish, 2017; Nugroho & Muafi, 2021). These mechanisms should, in combination, be reflected in lower reported turnover intentions.

H4.

Organizational Culture is negatively associated with Turnover Intention.

H5.

Team Support is negatively associated with Turnover Intention.

2.4.4. The Mediating Role of Team Support

While ethical climate and managerial competence represent organization-level cultural resources, employees experience them partly through everyday interactions within their teams. Supportive team environments help translate ethical and competent management practices into positive employee outcomes (Džambić et al., 2025). Supportive teams can thus act as a proximal conduit through which broader cultural signals are translated into individual attitudes: when managers are perceived as competent and the organization as ethical, teams are more likely to coordinate, share workload, and provide emotional support, which in turn should be reflected in higher job satisfaction (Jankelová et al., 2023; Weng et al., 2016) and lower turnover intention (Joe et al., 2018; Zaheer et al., 2021). Moreover, evidence from organizational behavior research suggests that team climate mediates the relationship between ethical or managerial factors and turnover by increasing job satisfaction and emotional resilience (Zhu et al., 2017). On this basis, we propose team support as a key mediating mechanism between organizational culture and employee outcomes.

H6.

Team support mediates the relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction.

H7.

Team support mediates the relationship between organizational culture and turnover intention.

3. Materials and Methods

We used standardized questionnaires to collect data from healthcare professionals, physicians, nurses, and other clinical staff employed in public and private institutions across the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina; the data were analyzed using SPSS 25 and AMOS 23 to evaluate the validity of our working hypotheses The study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional design, with data gathered via a structured survey instrument. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was selected as the research context because it offers a coherent regulatory framework and a diverse mix of public and private institutions, which allowed for the consistent use of a single Bosnian-language instrument and yielded findings that are policy-relevant within one health system. The sample (N = 430) was obtained using non-probability (convenience sampling). Invitations were distributed via official institutional emails and on-site paper surveys, and because we did not have reliable information on the total number of eligible staff approached in each institution, precise response rates could not be calculated. Although convenience sampling and a cross-sectional design carry limitations, the sample size is well within acceptable bounds for SEM in exploratory contexts. Prior work shows that AMOS can yield reliable estimates with samples above 100 when model complexity is moderate and distributional assumptions are reasonable (Wolf et al., 2013). Methodological texts typically classify samples above 400 cases as “large” sample sizes (Orcan, 2020). Structural equation modeling (SEM) served as the primary analytic approach. Data analysis proceeded in several stages: (1) preliminary screening and descriptive statistics in SPSS; (2) exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine dimensionality and, where appropriate, refine the measurement scales; (3) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS to test the measurement model; (4) estimation of the structural model using SEM to assess the hypothesized paths; and (5) bias-corrected bootstrapped mediation analysis to evaluate indirect effects among the key constructs. This research aims to test systematic relationships among organizational ethics (ET), managerial competence (MC), team support (TS), job satisfaction (JS), and turnover intention (TI), specifically, that ET, MC, and TS are positively associated with JS and negatively associated with TI, and that higher JS is linked to lower TI. The proposed research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

3.1. Measures

All constructs were measured with established, validated scales using Likert-type agreement responses (strongly disagree–strongly agree). Organizational culture, ethics (ET) was measured with 6 items adapted from Koys and DeCotiis (1991) (e.g., formal code, enforcement, ethical policies; α = 0.907). Organizational culture; managerial competence (MC) used 8 items adapted from Rogg et al. (2001), reflecting communication clarity, support, respect, and fairness (α = 0.922) (Rogg et al., 2001). Team support (TS) was measured with 4 coworker-support items originating in Mottaz (1988) and subsequently used in service-work studies, capturing helpfulness, cooperative climate, and team effort (α = 0.861). Job satisfaction (JS) employed a 10-item scale drawn from the Generic Job Satisfaction Scale (Macdonald & Maclntyre, 1997) (α = 0.806). Turnover intention (TI) was measured with the standard 3-item scale by Michaels and Spector (1982) (α = 0.918). Item reduction followed standard recommendations (Hair et al., 2021). Indicators with low primary loadings or problematic cross-loadings were considered for removal only when doing so clearly improved internal consistency and convergent validity (higher Cronbach’s α, CR, and AVE). Item wordings are listed (Table 1) and all scales demonstrated acceptable to excellent internal consistency.

Table 1.

Constructs, measurement items, scales, and sources for all study variables.

3.2. Data Collection

This study was a non-interventional survey study based on self-administered questionnaires. Data were collected using an online and printed survey to maximize reach and accommodate institutional preferences. Healthcare institutions were contacted via their official email addresses, and full study documentation was provided to any institution that requested it. The questionnaire was translated from the official English scale language into the Bosnian language to minimize language barriers. The survey introduction clearly explained the aim and purpose of the study, and participation was entirely voluntary and fully anonymous. No personally identifying information was collected, and responses could not be traced back to individual participants or specific institutions. To assess potential common method bias from using self-report data at a single time point, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test. The first unrotated factor explained 51.08% of the variance, and multiple factors with eigenvalues >1 and a well-fitting multi-construct measurement model suggest that common method bias is unlikely to fully account for the observed relationships.

3.3. Sampling and Respondents

A total of 430 valid responses were obtained from employees of public and private healthcare institutions across the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A non-probability (convenience/voluntary) approach was used. Invitations were sent to official institutional emails, and printed questionnaires were distributed on-site. The Federation was selected because it offers a coherent regulatory context and a diverse mix of providers, enabling consistent use of the Bosnian-language instrument and policy-relevant insights within a single health system. Recruitment was challenging; strict privacy norms and concerns about data security made some professionals reluctant to participate, reducing response rates in some institutions and introducing potential nonresponse bias. Consequently, the sample should not be considered statistically representative of all healthcare workers in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and findings should be interpreted with caution in light of these sampling and nonresponse limitations, which are further elaborated in the limitations section. These limitations are considered when interpreting the results.

3.4. Demographic Profile of Respondents

Table 2 summarizes the demographic profile of respondents. The sample comprised 430 respondents, predominantly female (61.9%) and male (37.4%). Education levels were diverse: 39.5% held a bachelor’s degree, 35.3% a master’s degree, 18.4% a doctorate, and 6.7% a high-school degree. Ages clustered in the 30–40 (33.3%) and 20–30 (22.4%) ranges, followed by 40–50 (20.1%), 50–60 (17.3%), 60+ (4.2%), and 18–20 (2.1%). Most were married (60.7%), with 31.2% single, 5.5% divorced, and 1.8% widowed. Additionally, specialist doctors formed the largest group (33.7%), followed by resident doctors (18.5%) and junior doctors (13.2%); nurses (9.5%) and department heads (8.8%) were also well represented, while other roles (e.g., pharmacists, physiotherapists, radiology/laboratory staff, managerial posts) each accounted for ≤3%. The majority worked in public institutions (74.8%) versus private (24.5%) and were based in tertiary (42.6%), primary (39.5%), or secondary (17.9%) levels of care.

Table 2.

Demographic Profile of Respondents.

4. Results

Descriptive statistical analysis was used to summarize respondents’ demographic profiles and their assessments of the study variables (see Table 2), while the structural model was analyzed to test the hypothesized relationships. To achieve the study aims, structural equation modeling (SEM) served as the primary analytic technique. SEM was selected because it is widely used in the behavioral and social sciences and can simultaneously estimate multiple relationships among latent and observed variables, including mediation effects (Golob, 2003). SPSS 25 was used for preliminary checks and descriptive statistics, and AMOS 23 was used for CFA, SEM, and path analysis.

Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate internal consistency, with results ranging from acceptable to excellent. Within Organizational Culture, Ethics (6 items; α = 0.907) and Managerial Competence (5 items; α = 0.922) showed excellent reliability. Team Support demonstrated strong reliability (4 items; α = 0.861), Turnover Intention was excellent (3 items; α = 0.918), and Job Satisfaction was acceptable to good (3 items; α = 0.806). All coefficients exceeded the conventional 0.70 threshold, indicating that the measures were reliable and suitable for subsequent CFA and SEM. The internal consistency of the constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reliability analysis.

To examine the underlying factor structure of the scales and to verify that the items clustered as theoretically expected, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted. During exploratory factor analysis, items were evaluated using both statistical and conceptual criteria. Following common recommendations (Field, 2004; Hair et al., 2021) items were considered for removal if they showed (a) low primary loadings (<0.40), (b) substantial cross-loadings on multiple factors, or (c) redundancy in content relative to other items within the same scale. The pattern matrix (Table 4) yielded a clear five-factor solution that closely follows the proposed conceptual model. All Ethics items (ET_1–ET_6) loaded strongly on Factor 1 (loadings = 0.640–0.917), the Managerial Competence scale was reduced from 8 to 5 items by removing MC_1, MC_6, and MC_7 due to weak or cross-loadings where remaining Managerial Competence items (MC_2, MC_3, MC_4, MC_5, MC_8) loaded on Factor 2 (0.719–0.912). All Team Support items (TS_1–TS_4) loaded on Factor 3 (0.778–0.863). The three Turnover Intention items (TI_1–TI_3) loaded very highly on Factor 4 (0.840–0.978), while the Job Satisfaction scale was reduced from 10 to 3 items; the retained items were JS_3, JS_5, and JS_7, with the remaining items excluded for low cross-loadings where items (JS_3, JS_5, JS_7) loaded on Factor 5 (0.715–0.969). Indicators with factor loadings between the 0.40–0.71 range are candidates for deleting if removing them clearly improves the scale’s internal consistency or convergent validity beyond the recommended cut-off values, which was the case in this study (Hair et al., 2021). All primary loadings were well above the commonly recommended threshold of 0.40, indicating that each item contributed meaningfully to its respective factors.

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis.

Several statistical tests and benchmark criteria were considered to ensure that the factor analysis was appropriate. The Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy fell within the acceptable range (0.80–0.89), in line with the recommendations of Williams et al. (2010). In addition, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis (Williams et al., 2010). All items exceeded the recommended cut-off of 0.40, supporting sufficient shared variance among the variables, and the extracted factors together explained more than 60% of the total variance, meeting the standard proposed by Gaskin (2016).

The majority of items displayed factor loadings greater than 0.40, satisfying the criteria suggested by Field (2004), Hair et al. (1998) and Hair (2010). In line with Field (2004), Hair (2010) and Hair et al. (2021), items with weaker primary loadings (in the 0.40–0.70 range) and/or problematic cross-loadings were treated as candidates for removal and were deleted based on their impact on scale quality (Field, 2004; Hair, 2010; Hair et al., 2021; Hair et al., 1998). In the analyses, dropping the weakest items from the Managerial Competence and Job Satisfaction scales led to clear improvements in internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability) and convergent validity (higher AVE), while preserving the theoretical core of each construct. Factor correlations remained below 0.70, indicating limited multicollinearity among the components and aligning with acceptable thresholds reported by Gaskin (2016). Finally, internal consistency for all constructs was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, with values falling in the “good” (0.70 ≤ α < 0.90) to “excellent” (α ≥ 0.90) range. Taken together, these findings support the validity, reliability, and dimensionality of the constructs used in the study.

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Based on the results in Table 5, the measurement model demonstrates satisfactory reliability and validity. Composite reliability (CR) values for all five constructs were above the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.811 for Job Satisfaction to 0.922 for OC Managerial Competence, while MaxR(H) coefficients (0.835–0.980) provided additional evidence of internal consistency (Hair, 2010). Convergent validity was supported by average variance extracted (AVE) values greater than 0.50 for all constructs (AVE = 0.591–0.794), indicating that each latent variable explains more than half of the variance in its indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The square roots of the AVE estimates (0.769–0.891) were generally higher than the corresponding inter-construct correlations, and the maximum shared variance (MSV) remained below AVE for four of the five constructs, which supports discriminant validity. The strongest correlations were observed between Job Satisfaction and OC Managerial Competence (=0.772) and between OC Ethics and OC Managerial Competence (=0.773), reflecting their conceptual relatedness, yet the pattern of results still suggests that these constructs capture distinct aspects of the organizational context (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

Table 5.

Convergent and discriminant validity.

In addition, global fit indices from the confirmatory factor analysis in AMOS indicated that the five-factor measurement model provided an acceptable representation of the data (χ2(179) = 626.51, p < 0.001; χ2/df = 3.50; CFI = 0.935; TLI = 0.924; IFI = 0.935; NFI = 0.911; RMR = 0.062; GFI = 0.872; AGFI = 0.835; RMSEA = 0.076, 90% CI [0.070, 0.083]). Incremental fit indices for the measurement model (CFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.924, IFI = 0.935, NFI = 0.911) were all above the conventional 0.90 threshold, indicating good relative fit. By contrast, some absolute fit indices were more modest: GFI (0.872) and AGFI (0.835) fell slightly below the often-cited 0.90 benchmark, and RMR (0.062) was somewhat higher than the ideal < 0.05. However, some authors argue that GFI and AGFI are absolute fit indices that compare the specified model to a null model, with values closer to 1.00 indicating better fit (Byrne, 2016; Hu & Bentler, 1995; Jöreskog, 1993). The GFI and AGFI values lie in the high 0.80s and, when considered together with the strong incremental fit indices, point to borderline but still acceptable absolute fit. These indices are known to be sensitive to sample size and model complexity, and our model includes multiple latent constructs with reduced but still multi-item scales estimated on a heterogeneous, non-probability sample of healthcare professionals.

Interpreted together with the strong incremental indices and an RMSEA of 0.076 (90% CI [0.070, 0.083]), we view the overall measurement model fit as acceptable for a model of this complexity, while acknowledging that sample characteristics may have contributed to the borderline values on some absolute indices. Parsimony-adjusted indices were also satisfactory (PNFI = 0.777; PCFI = 0.797), and Hoelter’s critical N values (N = 145 at p = 0.05; N = 155 at p = 0.01) suggested that the sample size was adequate for the specified model.

4.2. Structural Model Results

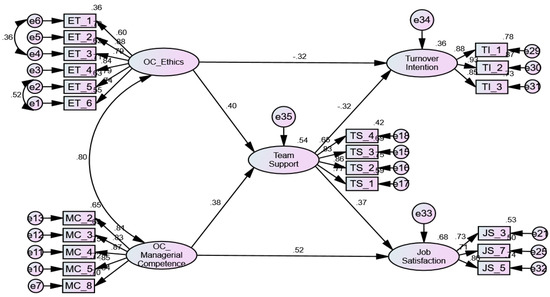

The structural equation model with Team Support specified as a mediator provides a clear picture of how the two dimensions of organizational climate relate to employees’ attitudes and intentions (Figure 2). Incremental fit indices for the structural model (CFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.935, IFI = 0.945, NFI = 0.921) again exceeded 0.90, and RMSEA (0.070) indicated a reasonable approximation error. Absolute indices showed a more borderline pattern: GFI (0.891) and AGFI (0.860) approached, but did not fully reach, the 0.90 guideline, and RMR (0.087) was slightly above the ideal cut-off. Given that GFI/AGFI and RMR are particularly sensitive to sample size, scale length, and model complexity, this pattern is not unexpected in a model with multiple latent variables, shortened scales, and a voluntary, heterogeneous clinical sample. Considered together with the incremental fit indices, RMSEA, and the theoretically coherent pattern of parameter estimates, we interpret the structural model as demonstrating adequate fit, while recognizing that sample characteristics may have constrained some of the absolute indices. OC Ethics shows a negative direct path to Turnover Intention (=−0.32), indicating that employees who perceive their organization as more ethical report lower intentions to leave. At the same time, OC Ethics is positively related to Team Support (=0.40), suggesting that an ethical climate is reflected in stronger perceptions of support within work groups. OC Managerial Competence also exerts positive effects on the social and attitudinal outcomes in the model: it predicts higher Team Support (=0.38) and has a relatively strong direct effect on Job Satisfaction (=0.52). In turn, Team Support is associated with higher Job Satisfaction (=0.37) and lower Turnover Intention (=−0.32).

Figure 2.

Research model and standard regression weights.

The mediation analysis further clarifies these mechanisms. In the tested model, OC Ethics and OC Managerial Competence were specified as independent variables, Team Support as the mediating variable, and Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention as outcomes. These paths indicate that employees who experience their organization as ethical and their managers as competent are more likely to feel supported by their teams, which is linked to greater satisfaction with their jobs and a reduced desire to leave the organization. Team Support thus functions as a key mechanism through which both OC Ethics and OC Managerial Competence are spread to individual outcomes: it helps channel the positive influence of the broader organizational climate into higher Job Satisfaction and lower Turnover Intention, while OC Ethics also retains a direct, protective effect against turnover intentions.

The structural model showed that both dimensions of organizational culture were significantly related to team processes and employee outcomes (Table 6). OC Ethics had a positive effect on Team Support (β = 0.396, C.R. = 5.016, p < 0.001), as did OC Managerial Competence (β = 0.381, C.R. = 4.933, p < 0.001), indicating that employees who perceive their organization as ethical and their managers as competent are more likely to experience supportive teams. Team Support, in turn, was negatively associated with Turnover Intention (β = −0.324, C.R. = −4.662, p < 0.001) and positively correlated with Job Satisfaction (β = 0.371, C.R. = 5.973, p < 0.001), suggesting that supportive team climates reduce employees’ intentions to leave while enhancing their satisfaction. OC Ethics also retained a significant direct negative effect on Turnover Intention (β = −0.322, C.R. = −4.648, p < 0.001), whereas OC Managerial Competence exerted a strong positive direct effect on Job Satisfaction (β = 0.523, C.R. = 8.157, p < 0.001). Taken together, these results confirm all hypothesized direct relationships between organizational culture, team support, job satisfaction, and turnover intention.

Table 6.

Summary of direct effects in the structural model.

Bootstrapped mediation analysis presented in Table 7 (5000 resamples) was conducted to examine whether Team Support transmits the effects of organizational climate to employee outcomes. The results showed that Team Support significantly mediated the relationship between OC Ethics and Turnover Intention (indirect effect = −0.165, 95% CI [−0.280, −0.088], p = 0.001) and between OC Ethics and Job Satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.109, 95% CI [0.054, 0.198], p = 0.001). Similarly, Team Support significantly mediated the links between OC Managerial Competence and Turnover Intention (indirect effect = −0.138, 95% CI [−0.280, −0.041], p = 0.004) and between OC Managerial Competence and Job Satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.092, 95% CI [0.044, 0.166], p = 0.001). In all cases, the confidence intervals did not include zero, confirming that the indirect effects are statistically reliable. Conceptually, these findings indicate that employees’ perceptions of an ethical climate and competent management reduce turnover intention and enhance job satisfaction in part because they foster stronger team support.

Table 7.

Summary of indirect effects in the structural model.

5. Discussion

This study examined how two dimensions of organizational culture, ethical climate and managerial competence, together with team support, relate to job satisfaction and turnover intention and have implications for psychological safety and employee well-being among healthcare professionals in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Using SEM, we found that both ethical organizational culture and perceived managerial competence were positively correlated with team support, that team support was in turn associated with higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intention, and that ethical climate and managerial competence also retained significant direct association with turnover intention and job satisfaction, respectively. Given the cross-sectional design, these relationships should be interpreted as patterns of statistical association rather than definitive causal effects.

Beyond confirming well-established links between culture, support, and attitudes, the configuration of paths in our model suggests a more effective pattern. Ethical climate was more strongly related to turnover intention than to job satisfaction, whereas managerial competence showed the strongest association with job satisfaction. One interpretation is that shared perceptions of fairness, integrity, and protection from unethical practices function as a “stay” signal in a context where staff face moral distress and high workforce pressure, while day-to-day managerial behaviors (clarifying expectations, backing staff, allocating work fairly) primarily shape how attractive the job feels on a daily basis. In other words, ethical climate appears more closely tied to whether people can imagine remaining in the organization, whereas managerial competence is more closely tied to how they evaluate their current work experience.

Bootstrapped mediation analyses further showed that team support significantly mediated the relationship between both cultural dimensions and job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Rather than functioning only through formal policies, cultural signals seem to be reflected in whether teams are experienced as cohesive, cooperative, and psychologically safe. At the same time, the significant direct associations from ethical climate and managerial competence to job satisfaction and turnover intention indicate that not all of their effects operate via team support; some may relate to more general perceptions of organizational justice, identity, or career prospects that go beyond immediate team dynamics.

These findings are consistent with prior research showing that ethical climates and competent management are central to staff well-being and retention in healthcare organizations. Studies have demonstrated that fair procedures, openness to ethical concerns, and support for patient-centered values reduce moral distress and are associated with higher job satisfaction and lower intention to leave (Abou Hashish, 2017; Suwaidan et al., 2022). Likewise, evidence from nursing and public-health literature suggests that nurse manager competence, particularly in staffing, communication, and developmental support, is a strong predictor of job satisfaction and reduced turnover intention (Mirzaei et al., 2024).

The strength of the path from managerial competence to job satisfaction, and from ethical climate to turnover intention, is particularly noteworthy. While both cultural dimensions contributed to team support, managerial competence showed the strongest direct relationship with job satisfaction, suggesting that the day-to-day behaviors of managers, communicating expectations, backing staff, and distributing workload fairly, may be especially important for how healthcare workers evaluate their jobs On the other hand, ethical climate showed a direct negative association with turnover intention even after accounting for team support, indicating that shared perceptions of fairness, integrity, and intolerance of unethical behavior are linked to employees’ willingness to remain in the organization above and beyond social support processes. The central role of team support as a mediator is aligned with the broader literature on social support at work. In line with previous studies, our data are consistent with the view that when healthcare professionals experience their teams as cooperative, helpful, and mutually supportive, they tend to report higher job satisfaction and lower intention to leave. The significant indirect paths from ethical climate and managerial competence to both outcomes via team support suggest that cultural and leadership are associated not only with formal structures and policies but also with everyday team dynamics.

Finally, the strong negative correlation between job satisfaction and turnover intention observed in this study is consistent with meta-analytic evidence in nursing research. This interpretation aligns with turnover theories as well as contemporary models emphasizing job resources, psychological climate, and social support as key levers for retention in high-demand healthcare settings. Nevertheless, because the data are cross-sectional, these patterns should be viewed as suggestive rather than as definitive evidence of underlying causal mechanisms. It is also important to interpret these findings in light of the measurement refinements undertaken. Several items from the original job satisfaction and managerial competence scales did not load strongly or showed problematic cross-loadings in this context and were therefore removed. As a result, the retained indicators capture somewhat narrower, more proximal aspects of satisfaction (e.g., overall evaluation, enjoyment) and managerial competence (e.g., communication, fairness, support), and our conclusions should be understood as referring to these facets rather than the full conceptual breadth of the original scales.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings provide several theoretical contributions to the literature on organizational culture, social support, and staff retention in healthcare.

First, by distinguishing between ethical climate and managerial competence as separate dimensions of organizational culture and modelling them simultaneously, the study shows that these constructs contribute uniquely to employee attitudes and intentions. In this sample, ethical climate was more strongly linked to turnover intention, whereas managerial competence was more strongly linked to job satisfaction. Rather than treating “culture” as a single, undifferentiated construct, these results support a more fine-grained view in which specific cultural dimensions may matter for different aspects of employee adjustment. Second, the results highlight team support as a key social mechanism linking organizational culture to individual outcomes. While previous studies have documented the main effects of ethical climate, leadership, and social support on job satisfaction and turnover, fewer have examined team support as an explicit mediator. This reinforces theoretical perspectives that locate job resources not only in formal structures and policies but also in proximal team processes and suggests that team climate deserves more explicit attention in culture–outcome models in healthcare. Third, the study contributes to the healthcare workforce literature in a Southeastern European context, where empirical evidence on organizational climate and retention remains comparatively limited. By demonstrating that a model derived largely from international research fits data from public and private institutions in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the study supports the cross-contextual relevance of ethical climate, managerial competence, and team support as core job resources, while also providing a basis for future comparative and longitudinal work in the region.

Finally, methodologically, the study strengthens the foundation of the constructs by combining exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, reporting convergent and discriminant validity, and testing mediation with bootstrapped confidence intervals. This provides an empirical platform for future work that may incorporate additional mediators (e.g., moral distress, burnout) or moderators (e.g., profession, level of care, contract type). At the same time, the need to remove several items from validated scales underlines that construct operationalizations may require careful re-examination when instruments are translated, adapted, or applied in healthcare systems with different organizational histories and resource pressures.

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

The findings also have clear implications for healthcare managers, hospital administrators, and policymakers concerned with workforce stability and quality of care. Although the study is cross-sectional and cannot establish causality, the observed patterns suggest several concrete levers that organizations can use to support staff well-being and retention.

First, the direct and indirect association between ethical climate and turnover intention suggests that ethics is not merely a compliance issue but a strategic retention resource. Healthcare organizations should ensure that codes of ethics are not only formally adopted but actively discussed, modeled by leaders, and integrated into everyday decisions about patient care, resource allocation, and conflict resolution. Practical steps include incorporating ethical dilemmas into regular team meetings, providing short ethics briefings or case discussions on wards, and ensuring that staff know how and where to report concerns safely. Visible action, when unethical behavior occurs together with open forums for discussing ethical tensions, may reduce moral distress and signal to staff that the organization stands behind its values rather than treating ethics as a purely formal requirement.

Second, the strong relationship between perceived managerial competence and job satisfaction underscores the importance of selecting and training managers not only on the basis of clinical or technical expertise but also on people-management skills. Training and development programs should explicitly focus on communication, fair workload distribution, constructive feedback, recognition, and conflict management. In practice, this may involve coaching new managers on how to give regular, balanced feedback; using transparent criteria when allocating shifts and responsibilities; and building routines for one-to-one check-ins where staff can raise concerns early. Organizations may also consider incorporating staff perceptions of managerial support and fairness into performance appraisals for leadership roles.

Third, because team support was a key mediator linking culture and leadership to job satisfaction and turnover intention, interventions that directly target team processes are critical. Examples include structured interdisciplinary rounds where all professions are invited to speak, peer mentoring systems for new staff, regular debriefings after difficult cases, and initiatives to improve handovers and cooperation across professions and shifts. Team leaders can use simple practices such as opening meetings by checking in on workload, explicitly inviting input from quieter members, and acknowledging mutual help to make psychological safety and support visible in daily work. Encouraging teams to jointly discuss workload, share responsibilities, and provide emotional as well as practical support can make organizational values tangible in everyday practice.

Given the strong link between job satisfaction and turnover intention, organizations should monitor satisfaction and perceptions of support regularly (e.g., through short pulse surveys or unit-level feedback). Units reporting low satisfaction and weak team support can then be prioritized for targeted interventions, coaching, or resource adjustments before turnover escalates. For policymakers and senior leaders, the results suggest that investments in ethical governance, leadership development, and team-based support structures are not peripheral “soft” initiatives but core components of a sustainable workforce strategy in high-demand healthcare settings.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings.

First, the cross-sectional design prevents strong causal conclusions. Although the model is theoretically grounded, it is possible that relationships are reciprocal (e.g., highly satisfied teams may also perceive their managers as more competent) or influenced by unmeasured third variables. Longitudinal and intervention studies are needed to test causal pathways more rigorously.

Second, the study relied on self-report data from a convenience sample of healthcare professionals in one national context. Self-report increases the risk of common method bias and social desirability, particularly for constructs such as ethics and managerial competence, where respondents may be motivated to present their organization and managers in a favorable light. The use of established scales and multi-factor modelling partially mitigates this concern, and we explicitly assessed common method variance using Harman’s single-factor test. The results suggested that a single factor did not dominate the variance structure, which is reassuring, but method and social desirability bias cannot be fully ruled out. Future research could incorporate objective indicators (e.g., turnover records, patient outcomes) and multi-source assessments (e.g., peer or supervisor ratings) to further reduce these concerns.

Third, there are important measurement limitations. During the factor-analysis process, we removed several items from the original validated scales (most notably 7 of 10 job satisfaction items and 3 of 8 managerial competence items) because they showed weak primary loadings or problematic cross-loadings and lowered reliability/validity indices. This data-driven reduction improved internal consistency and convergent validity of the retained indicators, but it also narrows the conceptual breadth of these constructs and may limit strict comparability with studies that use the full original scales. Moreover, because EFA and CFA were conducted on the same sample, the stability of the resulting measurement model should be interpreted with caution and replicated in independent datasets.

Fourth, although the sample included a range of professional roles and institutional types, it is not statistically representative, and certain groups (e.g., nurses vs. physicians, primary vs. tertiary care) may differ systematically in how they experience culture and support. In addition, healthcare work is organized in teams, and respondents were nested within units and institutions, yet our analyses relied on single-level SEM and treated responses as independent. Due to limited and uneven cluster sizes, we were not able to estimate multilevel models; consequently, team support was modelled as an individual perception rather than a fully aggregated team-level construct. This limits our ability to make inferences about genuinely collective team processes and cross-level effects. Multi-group SEM and multilevel SEM could be used in future work to test whether the model is invariant across professional categories, levels of care, or public vs. private institutions, and to separate team rom individual-level variance.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how ethical organizational culture, managerial competence, and team support jointly shape job satisfaction and turnover intention among healthcare professionals. Using structural equation modelling on survey data from 430 employees in public and private institutions, we found that both ethical climate and perceived managerial competence are positively related to team support, and that team support, in turn, is related to higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intention. Ethical climate also directly reduces turnover intention, while managerial competence directly enhances job satisfaction. Mediation analyses confirmed that team support partially transmits the effects of both cultural dimensions to these key attitudinal outcomes.

In conclusion, these findings highlight the importance of viewing staff retention not solely through the lens of individual resilience or financial incentives, but as a function of the broader organizational environment. Ethical norms, competent management, and supportive teams emerge as interdependent job resources that help healthcare workers feel valued, satisfied, and willing to remain in their organizations. For healthcare systems facing chronic workforce shortages and high demands, investing in these cultural and social resources is not a luxury but a strategic necessity. By strengthening the ethical climate, developing managerial competence, and actively cultivating team support, healthcare organizations can improve both staff well-being and the stability of the care they provide patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. (Aida Sehanovic); methodology, L.S. and N.H.; software, L.S.; validation, A.S. (Aida Sehanovic), N.H. and A.F.; formal analysis, L.S.; investigation, A.S. (Aida Sehanovic) and A.S. (Anida Sehanovic); resources, A.S. (Aida Sehanovic) and A.S. (Anida Sehanovic); data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S. (Aida Sehanovic), N.H., A.S. (Anida Sehanovic), S.K. and A.F.; visualization, L.S., A.S. (Anida Sehanovic); supervision, N.H., A.S. (Aida Sehanovic), S.K. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of JZU Dom Zdravlja Gradačac (Bosnia and Herzegovina) (protocol code 02-4361-2/25 and date of approval 28 August 2025) and Poliklinika “Medical Irac” Tuzla (Bosnia and Herzegovina) (date of approval 15 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abou Hashish, E. A. (2017). Relationship between ethical work climate and nurses’ perception of organizational support, commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intent. Nursing Ethics, 24(2), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açıkgöz, A., & Günsel, A. (2011). The effects of organizational climate on team innovativeness. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, P., Ebrahim Sanjaghi, M., Rezaeenour, J., & Ojaghi, H. (2014). Examining the relationships between organizational culture, knowledge management and environmental responsiveness capability. VINE, 44(2), 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarqi, M. N. (2024). Assessing the impact of multidisciplinary collaboration on quality of life in older patients receiving primary care: Cross sectional study. Healthcare, 12(13), 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammari, N., & Gantare, A. (2025). Ethical climate and turnover intention among nurses: A scoping review. Nursing Ethics, 32(5), 1434–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1993). The competent manager: A model for effective performance. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, R., & Infante-Moro, A. (2025). The importance of ethics in organisations, their leaders, and sustainability. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džambić, A., Hadziahmetovic, N., Sateeshchandra, N. G., Chelabi, K., & Fountis, A. (2025). Linking leadership and retention: Emotional exhaustion and creativity as mechanisms in the information technology sector. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N., Newman, A., Miao, Q., Wang, D., & Cooper, B. (2020). Antecedents of duty orientation and follower work behavior: The interactive effects of perceived organizational support and ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(3), 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2004). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (6th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis. Available online: https://statwiki.gaskination.com/index.php/CFA (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Golob, T. F. (2003). Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 37(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. A., Patterson, M. G., & West, M. A. (2001). Job satisfaction and teamwork: The role of supervisor support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (Ed.). (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Tatham, R. L., & Anderson, R. E. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebles, M., Trincado-Munoz, F., & Ortega, K. (2022). Stress and turnover intentions within healthcare teams: The mediating role of psychological safety, and the moderating effect of COVID-19 worry and supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 758438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppock, R. (1935). Job satisfaction. Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jankelová, N., Joniaková, Z., & Čambalíková, A. (2023). Factors supporting the job satisfaction of the middle healthcare management—The role of work conditions, managerial competencies and social support. Ekonomický Časopis, 71(6–7), 428–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, A., Hoferichter, F., Blömeke, S., König, J., & Kaiser, G. (2023). Investigating teachers’ job satisfaction, stress and working environment: The roles of self-efficacy and school leadership. Psychology in the Schools, 60(3), 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, S.-W., Hung, W.-T., Chiu, C.-K., Lin, C.-P., & Hsu, Y.-C. (2018). To quit or not to quit: Understanding turnover intention from the perspective of ethical climate. Personnel Review, 47(5), 1062–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1993). Testing structural equation models (Vol. 154). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., & Kim, E. G. (2021). A meta-analysis on predictors of turnover intention of hospital nurses in South Korea (2000–2020). Nursing Open, 8(5), 2406–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Kim, H., & Oh, Y. (2023). Impact of ethical climate, moral distress, and moral sensitivity on turnover intention among haemodialysis nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 22(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koys, D. J., & DeCotiis, T. A. (1991). Inductive measures of psychological climate. Human Relations, 44(3), 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Li, S., Jing, T., Bai, M., Zhang, Z., & Liang, H. (2022). Psychological safety and affective commitment among Chinese hospital staff: The mediating roles of job satisfaction and job burnout. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1573–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Yan, X., Xie, G., Lu, J., Wang, Z., Chen, C., Wu, J., & Qing, W. (2025). The effect of nurses’ perceived social support on turnover intention: The chain mediation of occupational coping self-efficacy and depression. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1527205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A. (1976). Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S., & Maclntyre, P. (1997). The generic job satisfaction scale: Scale development and its correlates. Employee Assistance Quarterly, 13(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffoni, M., Sommovigo, V., Giardini, A., Paolucci, S., & Setti, I. (2020). Dealing with ethical issues in rehabilitation medicine: The relationship between managerial support and emotional exhaustion is mediated by moral distress and enhanced by positive affectivity and resilience. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(5), 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D. C. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for “intelligence”. American Psychologist, 28(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, C. E., & Spector, P. E. (1982). Causes of employee turnover: A test of the Mobley, Griffeth, Hand, and Meglino model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(1), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A., Imashi, R., Saghezchi, R. Y., Jafari, M. J., & Nemati-Vakilabad, R. (2024). The relationship of perceived nurse manager competence with job satisfaction and turnover intention among clinical nurses: An analytical cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 23(1), 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W. H., Griffeth, R. W., Hand, H. H., & Meglino, B. M. (1979). Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaz, C. J. (1988). Determinants of organizational commitment. Human Relations, 41(6), 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, F. I., & Muafi, M. (2021). The effect of ethical climate and job satisfaction on turnover intention mediated by organizational commitment. JBTI: Jurnal Bisnis: Teori Dan Implementasi, 12(1), 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, C., & Sadath, A. (2025). Exploring job satisfaction and turnover intentions among nurses: Insights from a cross-sectional study. Cogent Psychology, 12(1), 2481733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’donovan, R., & Mcauliffe, E. (2020). A systematic review of factors that enable psychological safety in healthcare teams. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 32(4), 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcan, F. (2020). Parametric or non-parametric: Skewness to test normality for mean comparison. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 7(2), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paksoy, M., Soyer, F., & Çalık, F. (2017). The impact of managerial communication skills on the levels of job satisfaction and job commitment. Journal of Human Sciences, 14(1), 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogg, K. L., Schmidt, D. B., Shull, C., & Schmitt, N. (2001). Human resource practices, organizational climate, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Management, 27(4), 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2025). Moderating effects of telework intensity on the relationship between ethical climate, affective commitment and burnout in the Colombian electricity sector amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vols. 1–2). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Schwepker, C. H. (2001). Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the salesforce. Journal of Business Research, 54(1), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadur, M. A., Kienzle, R., & Rodwell, J. J. (1999). The relationship between organizational climate and employee perceptions of involvement: The importance of support. Group & Organization Management, 24(4), 479–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwaidan, H., Alsubaie, S., Nassani, A., & Aljarallah, K. (2022). The impact of organizational support and ethical climate on turnover intention: Job satisfaction as a mediator. Arab Journal of Administration, 43, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Swalhi, A., Mnisri, K., Amari, A., & Hofaidhllaoui, M. (2023). The role of ethical organisational climate in enhancing international executives’ individual and team creativity. International Journal of Innovation Management, 27(01n02), 2350010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.-J., Kim, S.-H., & Wu, C.-L. (2016). Underlying influence of perception of management leadership on patient safety climate in healthcare organizations—A mediation analysis approach. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 29, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B., Onsman, A., & Brown, T. (2010). Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruffe, C. (1993). What is meant by a competency? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 14(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W., Fan, Y., Bai, J., Zhang, Q., & Wen, Y. (2024). The relationship between organizational climate and job satisfaction of kindergarten teachers: A chain mediation model of occupational stress and emotional labor. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1373892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, S., Ginsburg, L., Wong, H. J., Thomson, K., Bain, L., & Wulffhart, Z. (2021). Acute care nurses’ perceptions of leadership, teamwork, turnover intention and patient safety—A mixed methods study. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X., Wholey, D. R., Cain, C., & Natafgi, N. (2017). Staff turnover in assertive community treatment (Act) teams: The role of team climate. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.