1. Introduction

Digital Transformation (DT) has become a strategic axis for the competitiveness and sustainability of organizations in today’s context. Emerging technologies are reshaping production processes, business models, and management practices, creating the need for new competencies, organizational structures, and adaptive cultures (

Battistoni et al., 2023;

Espina, 2025;

Jia et al., 2024). However, many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) still struggle to effectively integrate digitalization into their operations and strategies, especially in emerging economies where financial, technological, and human resources are limited (

de Mattos et al., 2024).

In the case of Peru, SMEs in Metropolitan Lima represent a significant part of the business fabric but show a low level of digital maturity and limited adoption of digital management practices (

Espina-Romero et al., 2024a). This situation highlights the challenge of strengthening Digital Competencies (DCs) and Digital Human Resource Management (DHRM) as essential factors to drive DT and consolidate an Organizational Culture (OC) oriented toward innovation and sustainability.

Several studies have shown that DCs are a strategic resource that enables companies to enhance their performance and adapt to changing technological environments (

Aghazadeh et al., 2024;

Proksch et al., 2024;

Rupeika-Apoga et al., 2022). Likewise, DHRM contributes to creating more flexible, collaborative, and learning-oriented work environments (

Böhmer & Schinnenburg, 2023;

Vrontis et al., 2022). Nevertheless, previous research has mainly focused on developed countries (

Delery & Doty, 1996;

Flunder, 1970), leaving empirical gaps on how these factors interact in Latin American SMEs.

OC also plays a determining role in digital change processes, as it influences employees’ disposition toward innovation and technology adoption (

Leso et al., 2023;

Malewska et al., 2024). However, there is no consensus on the direction and intensity of its relationship with DT and HR management, especially in contexts with lower technological maturity such as Peru.

Given this gap, it becomes necessary to analyze in an integrated way how DCs, DHRM, and OC contribute to the DT of SMEs in Lima. The research problem focuses on the lack of empirical evidence explaining the combined effect of these variables in emerging contexts, where digitalization progresses unevenly and organizational practices are still adapting. Within this framework, the general objective of the study is to analyze the effect of DCs, DHRM, and OC on the DT of SMEs in Lima.

Theoretically, the study is based on the Resource-Based View (RBV) (

Barney, 1991) and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) (

Teece et al., 1997), which explain how organizations develop, integrate, and reconfigure resources to respond to changing environments. From this perspective, DCs are conceived as a strategic resource that, when dynamically managed through DHRM, drives DT and fosters the development of an adaptable OC.

The value of this research lies in expanding the understanding of the role of digital capabilities and people management in the context of SMEs within an emerging economy. Moreover, it provides relevant empirical evidence for business leaders and policymakers interested in promoting sustainable digital transformation strategies.

The article is organized into six sections: the first corresponds to the introduction; the second, to the theoretical framework; the third, to hypothesis development; the fourth, to materials and methods; the fifth, to results; the sixth, to discussion; and the seventh, to conclusions. Based on this structure, the following section develops the theoretical framework of this study, addressing the main concepts, foundations, and relationships among the analyzed variables, as well as the contributions of previous research that support the proposed hypotheses.

2. Theoretical Framework

DT currently represents one of the main strategic challenges for SMEs, especially in emerging economies such as Peru, where financial, technological, and human resource constraints affect the pace and depth of change processes (

de Mattos et al., 2024;

Jia et al., 2024). This phenomenon cannot be analyzed in isolation, as it depends on multiple internal factors that interact with one another, such as DCs, DHRM, and OC (

Espina-Romero et al., 2024a,

2024b;

Leso et al., 2023). Understanding the relationship among these variables is crucial to explain the levels of adaptation, sustainability, and competitiveness that Lima’s SMEs can achieve in volatile and increasingly demanding market environments (

Costa Melo et al., 2023;

Malewska et al., 2024).

DCs are defined as the set of abilities that enable organizations to effectively implement and leverage digital technologies, encompassing both the strategic orientation toward digitalization and the technical and organizational capacity to integrate these technologies into processes (

Anwar et al., 2024;

Rupeika-Apoga et al., 2022). Recent research has linked these competencies with organizational resilience and business model maturity—determinants of innovation and sustainability in developing markets (

Aghazadeh et al., 2024;

Zhang et al., 2024).

Furthermore, DCs include digital leadership, platform management, and technological resilience (

Cheng et al., 2024;

Espina-Romero et al., 2023;

Noroño Sánchez, 2025). From the dynamic capabilities perspective, DCs constitute strategic resources that must be reconfigured according to environmental demands (

Teece et al., 1997;

Zhang et al., 2024). However, several authors warn that these competencies alone do not ensure sustainable transformation processes if they are not accompanied by an OC conducive to change (

Alshammari et al., 2024;

Isensee et al., 2023).

DT, on the other hand, is conceived as a complex, multi-phase process that ranges from process digitalization to business model innovation, supported by technologies associated with Industry 4.0 (

Battistoni et al., 2023;

Peixoto Rodríguez, 2025). This process involves not only adopting digital tools but also strategically integrating them to create economic, social, and environmental value, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (

Costa Melo et al., 2023;

Klein & Todesco, 2021).

According to

Dąbrowska et al. (

2022), DT constitutes a socioeconomic shift that simultaneously affects individuals, organizations, and ecosystems, while

Jia et al. (

2024) emphasize that, in SMEs, this process depends on internal factors such as culture and organization, as well as external ones related to customers and suppliers. Literature shows that, in emerging contexts like Peru, the shortage of specialized resources and firm heterogeneity reinforce the need to understand how SMEs integrate digitalization based on their internal competencies and capabilities (

de Mattos et al., 2024;

Espina-Romero & Guerrero-Alcedo, 2022).

DHRM is understood as the integration of digital technologies into human resource management processes, encompassing task automation, online training, digital communication, and data analytics for strategic decision-making (

Garg et al., 2022;

Vrontis et al., 2022).

Vahdat (

2022) argues that digital management constitutes a key mechanism for addressing current HR challenges, while

Böhmer and Schinnenburg (

2023) highlight its role in developing employees’ DCs. Similarly,

Alhamad et al. (

2022) emphasize its potential to foster creativity and online learning, while

Alhan (

2023) underscores its contribution to improving organizational collaboration and communication. However, debate persists regarding whether its influence on DT and OC is direct or mediated, as some studies view DHRM as an immediate driver of digitalization, whereas others consider it an indirect facilitator (

Garg et al., 2022;

Isensee et al., 2023).

In this context, OC emerges as a cross-cutting element that can act as both an enabler and a barrier to change processes. It is defined as the set of shared values, beliefs, and practices that shape internal dynamics and organizational performance (

Arabeche et al., 2022).

González-Tejero and Molina (

2022) highlight its role in fostering intrapreneurship and innovation, while

Leso et al. (

2023) and

Malewska et al. (

2024) point out that a flexible, innovation-oriented OC is crucial for successful DT in SMEs.

Isensee et al. (

2023) add that culture can be measured as an outcome of planned strategic actions, serving as a driver of both digital and sustainable development. Nonetheless, other studies reveal that not all cultural components carry equal weight in the success of digitalization—factors such as employee empowerment or innovation orientation produce differential effects (

Alshammari et al., 2024;

Peña & Caruajulca, 2024). For Lima’s SMEs, which face high competition and resource constraints, cultivating an OC aligned with digitalization is a determinant of competitiveness and sustainability (

Costa Melo et al., 2023;

Espina-Romero et al., 2024a).

Despite notable progress, the literature presents several gaps. First, most studies originate from developed countries, limiting understanding of DT in SMEs from emerging economies like Peru (

Cheng et al., 2024;

de Mattos et al., 2024). Second, there remains no consensus on the specific role of DHRM, as its impact on DT and OC has not been clearly established as direct, mediated, or conditional (

Böhmer & Schinnenburg, 2023;

Vrontis et al., 2022). Finally, few studies have simultaneously examined the interactions among DCs, DHRM, DT, and OC, particularly through structural models that account for mediation and moderation relationships (

Jia et al., 2024;

Zhang et al., 2024).

To address these limitations, the present study draws on two complementary conceptual frameworks. From the Resource-Based View (RBV) (

Barney, 1991), DCs are considered strategic assets that enable firms to achieve sustainable advantages over time. Meanwhile, the Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) (

Teece et al., 1997) provides a more flexible and adaptive perspective, explaining how organizations develop, integrate, and reconfigure their digital resources to adapt to changing environments. However, while the RBV has been criticized for its static nature, DCT faces challenges in empirical application, particularly in SME contexts (

de Mattos et al., 2024;

Zhang et al., 2024).

Thus, the hypotheses proposed in this study (

Figure 1) are grounded in the reviewed evidence. The literature suggests that DCs influence both DT and DHRM (

Aghazadeh et al., 2024;

Rupeika-Apoga et al., 2022); that DT and DHRM, in turn, impact OC (

Leso et al., 2023;

Malewska et al., 2024); and that indirect and mediated effects link all four variables (

Alshammari et al., 2024;

Isensee et al., 2023). These complex relationships are particularly relevant for Lima’s SMEs, as they reflect the need to build comprehensive digitalization strategies that strengthen competitiveness and sustainability in emerging contexts (

Costa Melo et al., 2023;

Espina-Romero et al., 2024a).

Taken together, the reviewed literature suggests that DT in SMEs should be understood as a process driven by the interaction between DCs, DHRM, and OC. DCs represent a strategic resource that enables firms to adopt and leverage digital technologies; however, their impact on transformation outcomes largely depends on how these competencies are developed, deployed, and sustained through digitally enabled human resource practices. In this sense, DHRM acts as a dynamic mechanism that translates digital skills into organizational routines, learning processes, and adaptive behaviors, thereby influencing both digital transformation and cultural change. OC, in turn, reflects the extent to which these human-centered digital practices are internalized and embedded within the organization, shaping employees’ openness to change and innovation. Grounded in the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory, this integrated perspective provides the theoretical foundation for examining the interrelationships among DCs, DHRM, OC, and DT within the proposed structural model.

Based on the conceptual and empirical review presented, theoretical relationships are identified that allow for the formulation of a structural model integrating DCs, DHRM, DT, and OC. Consequently, the following section presents the development of the hypotheses, supported by empirical evidence and the theoretical foundations previously discussed.

3. Development of Hypotheses

DCs represent a strategic resource that enables organizations to integrate technological tools into their processes and business models. These competencies encompass not only technical knowledge but also the ability to manage change and respond to digitalization challenges. Previous studies have shown that companies with higher levels of DCs tend to progress more rapidly and effectively in their DT processes (

Aghazadeh et al., 2024;

Rupeika-Apoga et al., 2022). In the case of SMEs in Lima, where competitive pressure and resource scarcity are determining factors, these competencies can make a decisive difference in the degree of technology adoption. Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. DCs positively influence the DT of SMEs.

Beyond their direct impact on DT, DCs play a central role in DHRM. The adoption of digital tools in people management—such as automation, virtual training, and online communication—depends on the digital readiness and skills of both leaders and employees (

Böhmer & Schinnenburg, 2023;

Vrontis et al., 2022). Accordingly, it is expected that a higher level of DCs will promote the adoption of DHRM practices in Lima’s SMEs. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. DCs positively influence DHRM.

DT not only implies technological changes but also cultural transformations within the organization. An OC open to innovation and learning facilitates the integration of digital technologies, fosters employee participation, and contributes to the sustainability of change (

Leso et al., 2023;

Malewska et al., 2024). Consequently, the following hypothesis is established:

H3. DT positively influences OC.

DHRM also has a relevant effect on OC. When human resource processes incorporate digital tools that promote transparency, communication, and training, they strengthen values such as collaboration, innovation, and trust in change (

Alhamad et al., 2022;

Alshammari et al., 2024). In the context of Lima’s SMEs, where work teams tend to be small, this influence can be even more significant. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4. DHRM positively influences OC.

While DCs influence both DT and DHRM, it is also reasonable to expect a direct effect on OC. Organizations that develop digital skills not only implement new tools but also generate changes in internal values, beliefs, and practices (

Cheng et al., 2024;

Espina-Romero et al., 2024a). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H5. DCs positively influence OC.

The literature also suggests that DHRM acts as a driver of DT. By digitalizing key functions such as training, communication, and data-driven decision-making, organizations create conditions that accelerate technological transformation (

Garg et al., 2022;

Vahdat, 2022). From this reasoning, the following hypothesis emerges:

H6. DHRM positively influences DT.

It is also necessary to analyze potential mediation effects among these variables. Several studies have shown that DCs, by facilitating the adoption of digital management practices, indirectly contribute to the advancement of DT (

Böhmer & Schinnenburg, 2023;

Zhang et al., 2024). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7. DHRM mediates the relationship between DCs and DT.

Similarly, DT may act as a mediator between DCs and OC. When firms apply their DCs in digitalization processes, these transformations can lead to cultural changes that promote innovation and adaptability (

Isensee et al., 2023;

Leso et al., 2023). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H8. DT mediates the relationship between DCs and OC.

It is also recognized that DCs strengthen DHRM, which in turn can enhance OC by introducing more collaborative, transparent, and innovative practices (

Alhan, 2023;

Peña & Caruajulca, 2024). For this reason, the following hypothesis is established:

H9. DHRM mediates the relationship between DCs and OC.

Finally, the relationship between DHRM and OC may also be mediated by DT. When HR processes become digitalized, this contributes to the implementation of new technologies, which in turn transform organizational values and behaviors (

Alshammari et al., 2024;

Costa Melo et al., 2023). From this reasoning, the final hypothesis is derived:

H10. DT mediates the relationship between DHRM and OC.

Once the hypotheses guiding this research have been formulated, it becomes necessary to describe the methodological approach that allows their empirical testing. Therefore, the following section details the study design, population and sample, instrument used, data analysis techniques, and ethical procedures employed during the investigation.

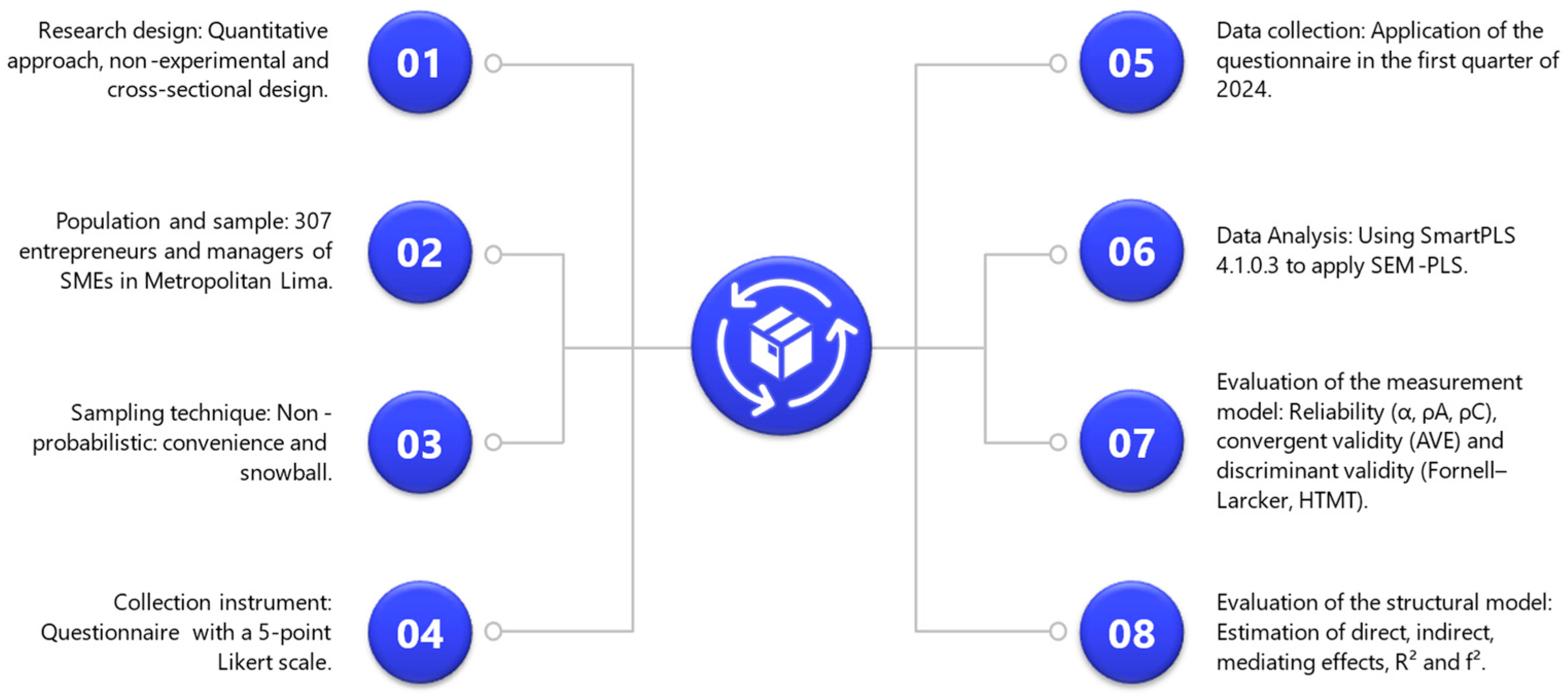

4. Materials and Methods

This research sought to examine the influence of DCs, DHRM, and OC on DT in SMEs in Lima. The study followed a non-experimental, cross-sectional design (

Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2018), as data were obtained at a single moment in time without applying any manipulation to the variables. A quantitative methodology was employed, using structured surveys and the partial least squares structural equation modeling technique (PLS-SEM), selected due to its effectiveness in analyzing complex models and its adequacy for non-probabilistic samples (

Hair et al., 2019).

4.1. Population and Sample

The study population was composed of entrepreneurs and managers from SMEs based in Metropolitan Lima, the area with the highest concentration of business activity in the country. The definitive sample included 307 business owners who were surveyed during the first quarter of 2024. All respondents were active entrepreneurs engaged in managerial or executive responsibilities, while those not currently involved in business operations were excluded. Although information on the participants’ educational level and professional experience was gathered, these data were used exclusively for descriptive purposes and did not serve as inclusion criteria.

The sampling method was non-probabilistic, using convenience and snowball techniques, which are suitable for exploratory studies requiring access to specific groups of entrepreneurs (

Etikan et al., 2016). The decision to maintain a sample size of 307 observations was based on the criteria of

Hair et al. (

2019), who indicate that this size is adequate for the application of the PLS-SEM method, ensuring sufficient statistical power.

Although the sampling strategy was non-probabilistic, the selected SMEs provide an analytically representative picture of the digital transformation dynamics in Metropolitan Lima. This region concentrates the largest share of SMEs in Peru and exhibits high heterogeneity in terms of sector, size, and digital maturity. Access to respondents was achieved through professional networks, entrepreneurial associations, and referrals, ensuring that participants held active managerial or decision-making roles. The sample size of 307 SMEs exceeds the minimum requirements for PLS-SEM analysis and allows for robust estimation of complex structural relationships, supporting the external analytical validity of the findings within similar urban SME contexts.

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of the respondents.

4.2. Data Collection Instrument

The instrument used was a structured questionnaire based on the validated version by

Espina-Romero et al. (

2024a), originally designed to measure four constructs: DCs, DHRM, DT, and OC. In this study, the four variables were retained, and the items were adapted to the context of SMEs in Lima without altering their conceptual structure. Each item was assessed using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), allowing the capture of entrepreneurs’ perceptions regarding the level of digital adoption, people management, and organizational culture in their companies (

Joshi et al., 2015).

4.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

The data were processed and analyzed using SmartPLS software version 4.1.0.3 (

Ringle et al., 2024), following the recommendations of

Hair et al. (

2019) for developing variance-based structural equation models. This method was selected for its robustness with small samples and its ability to simultaneously estimate direct, indirect, and mediating effects among latent variables.

The analysis was conducted in two main phases:

- (1)

Measurement Model Evaluation—verifying construct reliability and validity through indicators such as Cronbach’s alpha (

Cronbach, 1951), composite reliability (ρc), rho_A, and average variance extracted (AVE). Discriminant validity was confirmed using the

Fornell and Larcker (

1981) criterion and the HTMT ratio (

Henseler et al., 2015).

- (2)

Structural Model Evaluation—analyzing path coefficients (β), significance levels (t and

p), 95% confidence intervals, and coefficients of determination (R

2). Effect sizes (f

2) were also calculated to determine the magnitude of each relationship (

Cohen, 1988), as well as the mediating effects of DHRM and DT on the dependent variables, following the guidelines of

Nitzl et al. (

2016).

Given that data were collected using a single self-reported questionnaire, potential common method bias (CMB) was assessed. Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for less than 50% of the total variance, suggesting that common method bias is unlikely to be a serious concern in this study. In addition, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were examined and remained below the conservative threshold of 3.3, further supporting the absence of critical common method bias.

4.4. Ethical Considerations

All participants were informed about the objectives of the study, and their participation was voluntary and confidential. Anonymity and the protection of personal data were ensured in accordance with ethical principles of social research (

Resnik, 2018). The collected data were used exclusively for academic purposes.

4.5. Declaration on the Use of AI-Assisted Technologies

During the preparation and processing of this research, technological tools were used for support purposes, including Microsoft Word for grammar and style review, Microsoft Excel for statistical data processing, ChatGPT and DeepL for translation verification and text clarity improvement, and Google Scholar for source retrieval and verification. These tools did not replace the interpretation or scientific judgment of the authors.

Figure 2 shows the 8 steps of the methodology applied in this study.

After applying the described methods and validating the measurement instruments, data analysis was carried out using the PLS-SEM model. The results obtained are presented below, organized according to the stages of measurement and structural model evaluation.

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis of the Measurement Model

The results in

Table 2 show that all constructs in the model meet the minimum reliability and convergent validity criteria recommended in methodological literature. First, the factor loadings of all items exceed the recommended threshold of 0.700 (

Hair et al., 2019), indicating that each indicator adequately explains the variance of its corresponding construct. The highest values are observed in DCs, with loadings above 0.910 and up to 0.950, demonstrating a high explanatory capacity of the items. Although some items in OC (OC1 = 0.688) and DT (DT1 = 0.735; DT3 = 0.744) are close to the minimum threshold, they remain acceptable since they exceed the 0.600 cutoff point considered valid in exploratory stages (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Second, the Cronbach’s Alpha values range from 0.851 (DT) to 0.956 (DCs). According to

Nunnally and Bernstein (

1994), a value above 0.700 confirms the internal consistency of the construct; therefore, all results indicate a high level of reliability. Similarly, the rho_A and rho_C (Composite Reliability) coefficients reinforce this conclusion, presenting values between 0.856 and 0.968, all above the 0.700 threshold recommended by

Dijkstra and Henseler (

2015). This demonstrates that the indicators within each construct share sufficient common variance and that the items consistently measure their respective dimensions.

Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) also meets the

Fornell and Larcker (

1981) criterion, ranging from 0.621 (OC) to 0.884 (DCs). This result means that each construct explains more than 50% of the variance of its indicators, confirming convergent validity. The most robust case corresponds to DCs (AVE = 0.884), which reflects that its items are highly representative of the construct.

Overall, the results indicate that the measurement model used in the study demonstrates a reliable and valid structure, meeting the methodological standards suggested by

Hair et al. (

2019),

Henseler et al. (

2015), and

Fornell and Larcker (

1981). The internal consistency, composite reliability, and average variance extracted all exceed the minimum recommended values, providing strong empirical support for the variables included DCs, DT, DHRM, and OC within the context of SMEs in Lima.

5.2. Evaluation Based on the Fornell–Larcker Criterion

The

Fornell and Larcker (

1981) criterion is used to assess discriminant validity, that is, the ability of a construct to be distinct from the others within the model. According to this criterion, the square root of the AVE of each construct must be greater than the correlations between that construct and the others.

Table 3 shows the following results:

DHRM presents a diagonal value of 0.861, higher than its correlations with DT (0.637), DCs (0.754), and OC (0.563). This result indicates that DHRM exhibits greater variance with its own indicators than with the other constructs.

DT shows a diagonal value of 0.793, which is also greater than its correlations with DHRM (0.637), DCs (0.676), and OC (0.411). This result indicates that DT is clearly differentiated from the other constructs.

DCs reach a diagonal value of 0.940, higher than the correlations with DHRM (0.754), DT (0.676), and OC (0.435). The wide difference demonstrates excellent discriminant validity for this construct.

OC presents a diagonal value of 0.788, greater than its correlations with DHRM (0.563), DT (0.411), and DCs (0.435). Although the differences are not as large as in DCs, they still meet the methodological criterion.

According to

Henseler et al. (

2015) and

Hair et al. (

2019), these results confirm that adequate discriminant validity exists, since all constructs share more variance with their own indicators than with other constructs in the model. This implies that the study variables are statistically independent and do not exhibit problems of conceptual overlap. The importance of this finding lies in ensuring the conceptual independence of the constructs, which is essential for correctly interpreting the structural relationships within the research model (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981;

Henseler et al., 2015). Consequently, the results provide strong methodological support for proceeding to the analysis of the proposed hypotheses.

5.3. Assessment of Discriminant Validity Using the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) Criterion

The HTMT (Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio) is a modern criterion recommended by

Henseler et al. (

2015) to assess discriminant validity in structural equation models based on PLS-SEM. According to these authors, HTMT values should be below 0.900 (strict criterion) or 0.850 (conservative criterion) to confirm that the constructs are distinct from one another. The results in

Table 4 show the following:

DHRM–DT (0.715): a value below both the 0.850 and 0.900 thresholds, indicating that DHRM and DT are conceptually different and do not present overlap issues.

DHRM–DCs (0.805): although it is the highest value, it remains within the acceptable range (<0.900), confirming that DCs and DHRM are discriminant.

DT–DCs (0.744): also within the accepted range, showing that DT and DCs are adequately differentiated.

OC–DHRM (0.613), OC–DT (0.460), and OC–DCs (0.462): clearly low values, reinforcing the discriminant validity of OC in relation to the other constructs.

Overall, the findings indicate that all HTMT values remain below the 0.900 threshold. This demonstrates solid discriminant validity in the model, confirming that the constructs analyzed are different and do not assess the same concept. These results are consistent with the recommendations of

Hair et al. (

2019), who argue that applying both the Fornell-Larcker and HTMT criteria offers a more rigorous assessment of discriminant validity than relying on a single criterion.

5.4. Assessment of Direct and Mediating Effects

The results of the structural model show that not all the hypothesized relationships are significant, providing a clear view of the factors that truly drive DT and OC in SMEs in Lima (see

Table 5).

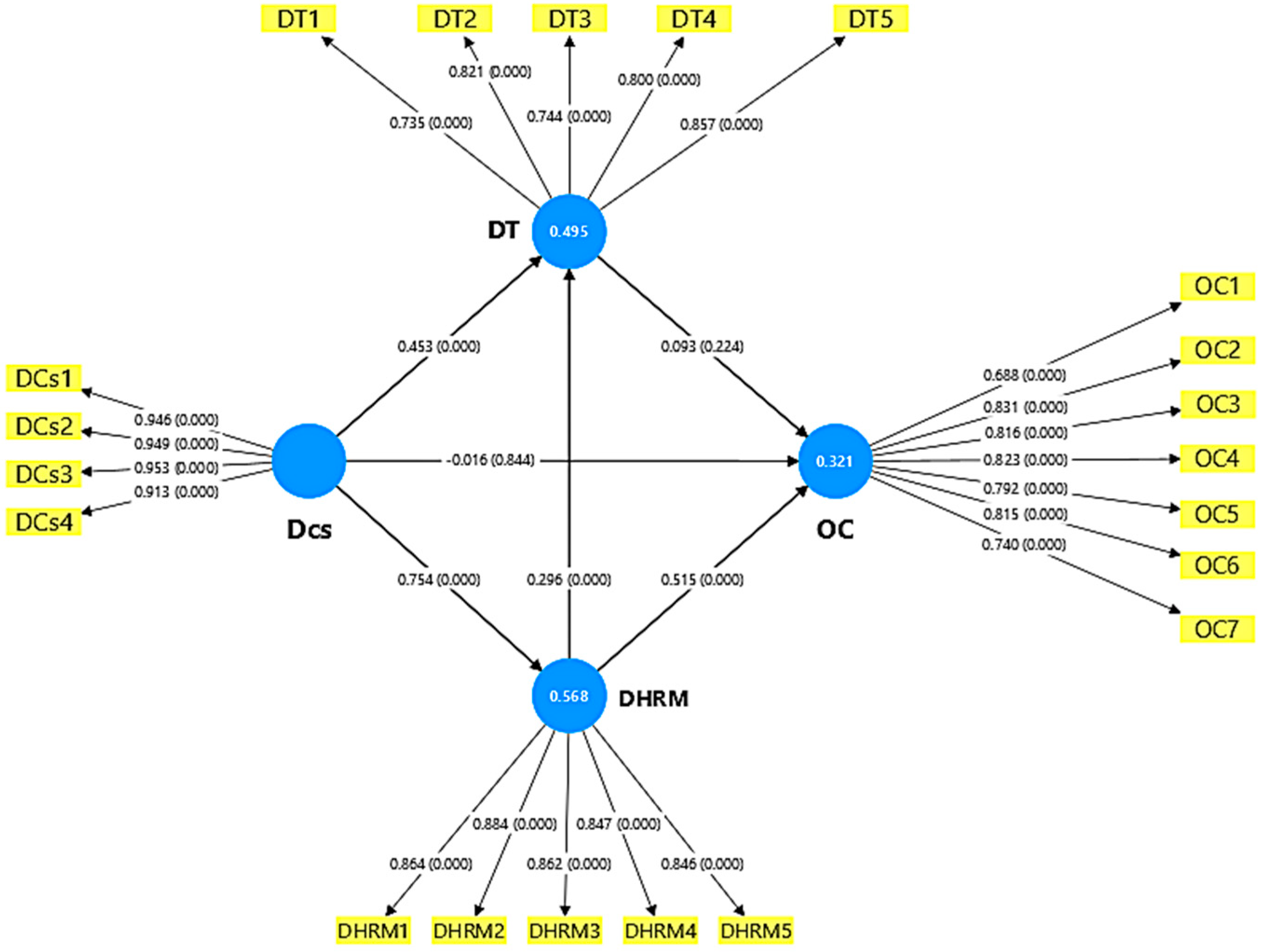

First, DCs exhibit a strong and significant direct effect on DT (β = 0.453, t = 6.881, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.317, 0.575]) and on DHRM (β = 0.754, t = 28.758, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.697, 0.801]). This confirms that DCs are a key strategic resource, explaining 49.5% of the variance in DT and 56.8% in DHRM. Regarding DHRM, the results reveal significant effects on OC (β = 0.515, t = 7.234, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.370, 0.650]) and on DT (β = 0.296, t = 4.268, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.159, 0.431]). This indicates that DHRM not only enhances organizational practices but also contributes to the advancement of DT.

On the other hand, DT does not show a significant direct effect on OC (β = 0.093, t = 1.215, p = 0.224, CI95% [−0.056, 0.244]), suggesting that in the context of Lima, technological transformation alone does not guarantee changes in internal values and practices. Likewise, DCs do not present a direct effect on OC (β = −0.016, t = 0.197, p = 0.844, CI95% [−0.188, 0.133]).

Regarding indirect effects, DCs significantly influence DT through DHRM (β = 0.223, t = 4.155, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.121, 0.332]). Similarly, DCs impact OC through DHRM (β = 0.388, t = 6.639, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.278, 0.505]). Both results confirm that DHRM is a key mediator within the model. In contrast, other indirect effects were not significant. This is the case for the paths DCs → DT → OC (β = 0.042, t = 1.166, p = 0.244, CI95% [−0.024, 0.118]) and DHRM → DT → OC (β = 0.028, t = 1.119, p = 0.263, CI95% [−0.013, 0.087]), ruling out DT as a mediator in these relationships.

In summary, the findings indicate that DHRM serves as the main bridge between DCs and organizational outcomes, both in terms of DT and OC. Conversely, DT does not exert a significant direct or mediating effect on OC in SMEs in Lima.

5.5. Evaluation of Effect Size in the Structural Model

The effect size (f

2) evaluates the specific contribution of each predictor construct to the endogenous variable in the structural model. According to

Cohen (

1988), the reference values are 0.020 (small), 0.150 (medium), and 0.350 (large). In PLS-SEM, f

2 complements R

2 by identifying the relevance of predictors beyond the level of explained variance (

Hair et al., 2019).

Table 6 presents the following findings:

DCs → DHRM (f2 = 1.314, p < 0.001): The effect is extremely large, far above the 0.35 threshold, confirming that DCs are the main determinant of DHRM. This result reinforces the strategic importance of DCs as a core capability.

DCs → DT (f2 = 0.175, p = 0.005): The effect is medium, indicating that DCs have a substantial influence on DT, although their impact is smaller than on DHRM. This suggests that DCs strengthen DT both directly and indirectly through DHRM.

DCs → OC (f2 = 0.000, p = 0.979): The effect is null and not significant, confirming that DCs do not directly impact OC. This finding is consistent with the direct effects analysis.

DHRM → DT (f2 = 0.075, p = 0.057): The effect is small with marginal significance (p ≈ 0.05). Although DHRM contributes to DT, its relative weight is limited.

DHRM → OC (f2 = 0.157, p = 0.003): The effect is medium and significant, confirming that DHRM plays a relevant role in strengthening OC. This demonstrates that DHRM is a key bridge for promoting cultural change.

DT → OC (f2 = 0.007, p = 0.597): The effect is practically null and not significant, indicating that in SMEs in Lima, DT does not have a substantial direct impact on OC. This aligns with the findings of the direct effects analysis.

Overall, the results highlight that DCs exert a very strong effect on DHRM and a medium effect on DT, while DHRM has a meaningful impact on OC. Conversely, DT does not directly modify OC, reinforcing the need to consider DHRM as the key mediator in organizational change processes.

5.6. Summary of Hypotheses Testing

To provide greater clarity and facilitate the interpretation of statistical results,

Table 7 presents a summary of the hypotheses testing. This table consolidates the findings from the analyses of direct, indirect, and effect size relationships, indicating whether each hypothesis was confirmed, not confirmed, or partially supported. Its inclusion allows for an easy comparison between the proposed relationships and the empirical evidence obtained, serving as a bridge to the discussion section.

Figure 3 displays the final structural model estimated with SmartPLS 4, including standardized coefficients and significance levels. Significant relationships were confirmed from DCs to DHRM and DT, as well as from DHRM to DT and OC. In contrast, the direct effects of DCs and DT on OC were not significant, confirming the mediating role of DHRM.

Statistical results provide empirical evidence supporting the relationships proposed in the theoretical model and the formulated hypotheses. Based on these findings, the next section develops the discussion, interpreting the observed effects and contrasting them with previous studies, relevant theories, and the specific characteristics of SMEs in Metropolitan Lima.

6. Discussion

The findings of this research demonstrate that DCs and DHRM are fundamental drivers for promoting DT and enhancing OC in SMEs in Lima, Peru. Out of the ten hypotheses formulated, six were fully supported, two received partial support, and two were not validated. The most significant effects appeared in the paths DCs → DHRM (β = 0.754) and DCs → DT (β = 0.453), followed by DHRM → OC (β = 0.515) and DHRM → DT (β = 0.296). These outcomes highlight the mediating role of DHRM, linking DCs with both organizational culture and transformation results, whereas DT does not exert either a direct or mediating influence on OC.

The confirmation of H1 and H2 aligns with previous findings that recognize digital competencies as essential strategic resources for organizational change (

Aghazadeh et al., 2024;

Rupeika-Apoga et al., 2022). However, this study extends prior work by applying the model to SMEs in an emerging economy, confirming that even with limited resources, digital skills significantly drive transformation and HR digitalization when supported by a learning-oriented culture. These findings strengthen the theoretical premise of the dynamic capabilities framework (

Teece et al., 1997), suggesting that digital competencies operate as flexible resources that allow organizations to adopt new technologies and maintain their competitiveness.

The favorable impact of DHRM on both DT and OC (H4 and H6) is consistent with the findings of

Vrontis et al. (

2022) and

Alhamad et al. (

2022), who showed that digitalized HR practices foster greater collaboration, transparency, and innovation. Nevertheless, the results also add novelty: the mediating role of DHRM (H7 and H9) provides empirical evidence that HR digitalization is not only a technological outcome but a strategic mechanism that links technical skills with cultural transformation and fosters continuous learning and organizational adaptability (

Medina, 2025).

Conversely, the lack of significance in the relationships DT → OC (H3) and DCs → OC (H5) differs from studies conducted in more advanced digital environments (

Leso et al., 2023;

Malewska et al., 2024). This discrepancy can be explained by contextual factors: Peruvian SMEs are still in early stages of digital maturity, where cultural transformation follows—rather than precedes—technological adoption. Thus, culture in these organizations remains reactive, evolving as a consequence of HRM and capability building, not as a direct product of technological change.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the literature by strengthening the integration of the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory, demonstrating that digital competencies and digital human resource management jointly enable digital transformation and cultural adaptation in SMEs (

Kero & Bogale, 2023). Rather than treating resources and capabilities as independent drivers, the findings refine both theoretical frameworks by showing that digital resources require dynamic, human-centered mechanisms to be effectively transformed into strategic organizational outcomes. In this sense, the study advances a more process-oriented understanding of digital transformation, emphasizing the interdependence between competencies, HR digitalization, and organizational culture.

From a practical perspective, the results highlight the importance of adopting human-centered digital transformation strategies in SMEs. Specifically, managers are encouraged to invest in digital upskilling initiatives, HR digitalization, and internal communication systems that foster learning, collaboration, and cultural alignment. These insights are also relevant for policymakers and business support institutions, which may leverage the findings to design training and funding programs aimed at enhancing the digital maturity of SMEs. Overall, the study underscores that sustainable digital transformation extends beyond the mere adoption of digital technologies and depends fundamentally on the strategic alignment between human resource practices and organizational cultural values.

6.2. Limitations and Considerations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer causal relationships or observe the dynamic evolution of digital transformation processes over time. Second, the use of non-probabilistic sampling techniques (convenience and snowball sampling) limits statistical generalization beyond the studied sample, as participation depended on accessibility and referral networks. Third, the geographical focus on SMEs located in Metropolitan Lima may constrain the external validity of the findings, as digital maturity levels, institutional support, and organizational practices may differ across regions. Nevertheless, the study achieves strong analytical validity by focusing on active SMEs in the country’s main entrepreneurial and digital hub, characterized by high sectoral and organizational heterogeneity.

Although procedural and statistical tests suggest that common method bias does not pose a significant threat, the use of a single self-reported survey may still introduce perceptual bias, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

6.3. Future Research Directions

To address these limitations, future research could adopt longitudinal designs to capture the temporal dynamics of digital transformation and organizational culture change. Additionally, comparative studies across multiple regions within Peru or across Latin American countries would help assess contextual differences in digital maturity and institutional environments. Future research could also employ probabilistic sampling strategies or mixed-method approaches to enhance generalizability and deepen understanding of SME digital transformation pathways. Finally, incorporating additional variables such as leadership styles, innovation climate, or digital resilience may further enrich the explanatory power of the model.