Abstract

The hospitality sector is an environment where leadership quality significantly impacts organizational performance and employees’ well-being. However, research on leadership styles in the Greek hotel industry remains limited. Using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), this research explores the connections between transformational, transactional, and passive leadership styles, as well as the employees’ outcome (extra effort, effectiveness, satisfaction). The survey was conducted among 211 hotel employees from the major Greek tourism areas. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) supported the MLQ structure, and multiple regression analyses were used to examine the hypothesized relationships. The findings indicate that transformational leadership is the primary factor positively associated with all three employee outcomes, with idealized influence and individualized consideration being the strongest predictors. Contingent reward (transactional leadership) is positively associated with several employee outcomes. Laissez-faire leadership has significant negative associations with extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction, while passive management-by-exception demonstrates some positive associations, making the situation difficult to interpret. These results verify the Full Range Leadership Model (FRLM) as a viable theoretical framework in the Greek hotel sector and offer a plethora of research-based guidelines to leadership program schedulers.

1. Introduction

The hospitality industry is a highly volatile and resource-demanding sector in terms of human capital globally (Belias et al., 2025), where the quality of leadership has a direct impact on the hotel company’s financial results, as well as the well-being of the employees and the level of customer service (Ali, 2024). In Greece, tourism and hospitality are major contributors to the country’s economy, accounting for a significant share of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employment. The tourism industry employs approximately 900,000 employees during high seasons and provides over 12 billion euros in revenue annually (SETE, 2022).

However, this sector is plagued by problems such as high employee turnover rates, emotional exhaustion, poor work–life balance, and fluctuating service quality (Belias et al., 2022b); all these issues have a direct effect on leadership performance (Kara et al., 2013; Davidson & Wang, 2011; Viterouli et al., 2025a; Belias et al., 2022a).

Despite the importance of leadership being widely recognized in the hospitality environment (García-Guiu et al., 2020), there are few empirical studies that have explored different leadership styles and their impact on employee outcomes in the Greek hospitality industry. This research fills an essential void by examining how the three leadership styles (transformational, transactional, and passive) influence employees’ extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction in four- and five-star hotels across the major Greek regions.

This study aims to validate the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) tool by Bass and Avolio (1993) in the Greek hospitality industry. After evaluating the MLQ tool in the Greek hotel industry, the authors will investigate the connection between different leadership styles and employee outcomes (extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction) in the Greek hotel industry. Bass and Avolio’s (1993) Full Range Leadership Model (FRLM) is derived from Burns’ (1978) ground-breaking work on transformational and transactional leadership, which was later broadened by Bass (1985). This model offers an inclusive framework for understanding leaders’ behaviors, ranging from passive–avoidant behaviors to transformational and transactional strategies (Bass & Avolio, 1993). This framework suggests that transformational and transactional leadership are not distinct sets of behaviors but rather different aspects that can be used simultaneously to varying extents (Avolio et al., 1999).

The MLQ-5x short form, which identifies the nine leadership dimensions in the three main styles and additionally measures the three leadership outcomes, has been validated across several organizational contexts and cultures, demonstrating strong psychometric properties (Antonakis et al., 2003; Avolio & Bass, 2004). By applying this well-established theoretical model to the Greek hotel sector, this study contributes to the knowledge of how global leadership values manifest within specific cultural and organizational environments.

The significance of this research is very considerable for both academic knowledge and the hospitality industry. From an academic perspective, the investigation contributes to a major gap in the research: although the MLQ tool has been widely used in manufacturing, healthcare, education, and the military, there has been little research on its use in the hospitality industry, especially in Southern European countries like Greece (Kim et al., 2023; Abolnasser et al., 2023).

The research on leadership in the hospitality sector has mainly drawn its data from the Western European and North American regions; little has been performed on the hospitality sector in the Mediterranean, which is influenced by different cultural values, family-owned business structures, and seasonal patterns of operation (García-Guiu et al., 2020; Ariza-Montes et al., 2017). Understanding the leadership style that has the greatest impact on employee outcomes provides the most practical guidance for leadership development programs, recruiting strategies, and performance management systems in Greek hotels (Tracey & Hinkin, 1994). With employees’ well-being receiving attention, along with organizational resilience and service quality recovery, the need to identify effective leadership strategies has become quite pressing for hospitality companies worldwide (Abolnasser et al., 2023).

The innovation of this study lies in several key domains. First, the present research represents a pioneering work in the comprehensive application of the MLQ tool in the Greek hotel industry; thereby, it offers solid empirical data on the validity and utility of the Full Range Leadership Model in an uncharted environment. Although some studies have examined the dimensions of leadership in hospitality settings, very few have considered all nine MLQ dimensions and three outcome variables simultaneously within a single national context (Quintana et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2023). Second, this work employs a highly thorough statistical approach, utilizing confirmatory factor analysis as one of the techniques to demonstrate the MLQ factor structure for the Greek hospitality industry. Thus, it meets the demand for local validation of leadership tools (Antonakis et al., 2003). Third, the study’s range of locations—extending beyond a single focus and encompassing major Greek tourism regions, such as Attica, Crete, and Chalkidiki—provides insight into leadership practices in diverse tourism markets and various operational contexts (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). Finally, examining the impact of leadership on the recovery period following the pandemic allows this study to reveal leadership changes during a pivotal moment for employees’ psychological health and organizational agility (Abolnasser et al., 2023).

Consequently, the research objectives of this study are presented as follows:

RO1: To validate the MLQ tool on the Greek hotel industry.

RO2: To examine the relationship between the transformational leadership style and the employees’ outcome (extra efforts, effectiveness, satisfaction).

RO3: To examine the relationship between the transactional leadership style and the employees’ outcome (extra efforts, effectiveness, satisfaction).

RO4: To examine the relationship between the passive leadership style and the employees’ outcome (extra efforts, effectiveness, satisfaction).

2. Literature Review

The theoretical framework of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) was introduced by Burns’ (1978) research on transformational and transactional leadership styles. This work was extended later by Bass’s (1985) empirical studies. According to Bass (1985), a leader’s behavior can be described from passive avoidant (laissez-faire) behavior through transactional to transformational behavior. The Full Range Leadership Model is described by these three leadership behaviors (Bass & Avolio, 1993). This comprehensive framework differs from earlier leadership theories by proposing that transformational and transactional leadership styles are not two separate entities but complementary dimensions that a leader can combine to varying degrees (Avolio et al., 1999).

The MLQ tool has evolved over the years of its implementation, with the most recent version of MLQ-5x Short Form representing the current standard tool for measuring three leadership styles. This measurement tool comprises 45 items that assess nine leadership dimensions and three leadership outcomes (Avolio & Bass, 2004). The development of this measurement tool focused on fulfilling psychometric concerns and improving construct validity (Antonakis et al., 2003). Several studies across different organizational environments have supported the fundamental element of the Full Range Leadership Theory, as they have revealed relationships between leadership styles and organizational outcomes such as employee performance, satisfaction, and commitment (Bass, 1990; Lowe et al., 1996).

The first leadership style measured by the MLQ tool is the transformational leadership. Transformational leaders motivate and encourage their followers to transcend their personal interests and commit to common organizational goals; this behavior can lead to higher levels of motivation, morality, and performance (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006). The transformational leadership style is considered to be extremely effective in the hospitality industry. A transformational leader used teamwork and motivation to inspire employees and achieve positive outcomes, such as commitment, empowerment, higher levels of performance, and service innovation (Della Lucia & Giudici, 2021).

Transformational leadership (TL) comprises five different but interrelated dimensions. Idealized influence (attributed) (IIA), which is also known as “Builds Trust,” measures the level to which leaders gain trust, inspire power, and go beyond their own interests to help the followers (Avolio & Bass, 2004). This dimension refers to the charismatic characteristics of a leader that make him/her respected and admired by the followers. Idealized influence (behavior) (IIB), also known as “Acts with integrity,” refers to the leader’s moral and ethical behavior. Leaders’ followers tend to imitate this behavior.

Inspirational motivation (IM), also known as “Encourages Others,” refers to leaders’ ability to articulate compelling visions, convey their beliefs in the followers’ capabilities, and use symbols to direct the followers’ energy (Bass, 1985; Avolio & Bass, 2004). Studies in the hospitality industry have revealed that inspirational motivation was one of the most significant factors in employees’ engagement and organizational identification.

Intellectual stimulation (IS), also called “Encourages innovative thinking,” refers to the leaders’ characteristics to develop creativity in employees, question existing beliefs, and ask employees for help in solving problems (Bass & Bass, 2008). Recent studies on hotel environments show that the dimension of intellectual stimulation helps hotel employees to develop new creative ideas in hotel services (Shafi et al., 2020).

Individualized consideration (IC), or “Coaches and develops people,” describes the ability of the leaders to focus on the developmental needs of the followers. In other words, leaders tend to act as mentors or coaches who provide personalized support to the followers (Bass, 1985). Recent research in the hospitality industry found that this dimension significantly affects employees’ performance by fostering personal relationships between leaders and followers. More specifically, it has been observed that when employees receive personal attention, their satisfaction increases significantly (Khalil & Sahibzadah, 2017; Khan et al., 2020).

The second leadership style measured by the MLQ tool is Transactional leadership (TSL). This leadership style refers to the exchange relationships between leaders and followers that are focused on rewards, punishments, and clarification of work requirements to achieve the goals determined by the organization (Bass, 1985; Bass et al., 2003). This leadership style emphasizes maintaining the organization’s stability, ensuring that standard procedures are followed, and achieving the short-term goals through defined expectations and performance-based outcomes (Avolio et al., 1999).

One of the dimensions of transactional leadership is Contingent reward (CR), also known as “Rewards achievement”. According to this dimension, transactional leaders outline, communicate, set goals, and reward employees when their performance is successful (Avolio et al., 1999; Bass et al., 2003). In other words, contingent rewards help specify employees’ roles and tasks, set performance criteria, and provide rewards when the goal is achieved (Goodwin et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2011). Regarding the hotel environment, contingent rewards have been recognized as key factors that can lead to employees’ extra effort, efficiency, and satisfaction (Quintana et al., 2014).

Management-by-exception (active) (MBEA), or “Monitors deviations and mistakes,” includes the capability of a leader to observe the performance of their followers. These types of leaders seek deviations from set standards and take the necessary corrective measures to prevent mistakes from escalating (Avolio & Bass, 2004). This dimension of leadership helps to maintain high performance standards.

Management-by-exception (passive) (MBEP), or “Fights Fires,” refers to the type of leaders who intervene to solve a problem, only after it becomes very serious and it deviates from performance standards (Hinkin & Schriesheim, 2008). Because this leader intervenes only when the problems have arisen and the situation has become very difficult, this dimension has been linked to less positive results than active management-by-exception.

Passive leadership (PasL) or laissez-faire leadership describes the absence of leadership when the leader tries to avoid making decisions, abdicates leadership responsibilities, and intervenes very little, even when correction is required (Bass & Avolio, 1995; Skogstad et al., 2007). This dimension, also known as “Avoids involvement,” measures the times the leaders refuse to get involved in significant issues, are absent when needed, delay responses to urgent situations, and fail to follow up on subordinates’ requests (Avolio & Bass, 2004).

Laissez–faire leadership is considered the most passive and least effective leadership style of the Full Range Leadership Model (Antonakis et al., 2003). Contemporary studies have confirmed the negative impacts of passive laissez-faire leadership. More specifically, research on the hotel industry has shown a strong negative relationship between passive leadership and employees’ engagement. In particular, the dimension of laissez-faire can lead to role conflict, role ambiguity, and interpersonal conflict (Kelloway et al., 2005; Skogstad et al., 2007). In a few words, the behavior of laissez-faire leaders in hotel environments who do not involve themselves in situations can easily lead to employee turnover. Consequently, if personnel are under-motivated and work under job pressure, they will likely be unwilling to continue their work; thus, the rate of employees’ retention would be low (Fouad, 2019; Mwesigwa, 2018).

Several empirical studies have discovered that laissez-faire leadership is directly connected with high levels of work stress and workplace bullying, and lower levels of work confidence. Moreover, these studies revealed that passive leadership is negatively correlated with employees’ burnout, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction in the hospitality industry (Guchait et al., 2016; Che et al., 2017; Glambek et al., 2018). The passive nature of laissez-faire leadership leads the followers to believe that their leader is not engaged with them, and he/she does not care about their development. This attitude can create negative interdependence, which can harm workplace outcomes (Hinkin & Schriesheim, 2008).

Apart from leadership styles, the MLQ instrument measures the impact of leadership on followers (Zerva et al., 2024; Ntalakos et al., 2023, 2024a, 2024c). Extra effort (EE), also known as “Generates extra effort,” measures the extent to which the leaders influence followers to put in more effort than is usual without them being asked for it (Avolio & Bass, 2004). Recent research has indicated that transformational leaders who communicate clearly and comprehensively, develop organizational goals, motivate employees to go beyond self-interests, and encourage them to put extra effort into difficult tasks (Douglas, 2012; Jackson et al., 2012). Regarding the hospitality industry, the two dimensions of idealized attribute (transformational leadership) and contingent reward (transactional leadership) have been identified as the key factors that can positively influence employees’ extra effort (Quintana et al., 2014).

Effectiveness (EF), or “Is productive,” measures the efficiency of leaders when they interact with different organizational levels (Avolio & Bass, 2004). According to Hinkin and Tracey’s (1994) research in the hospitality industry, the transformational leadership style has a direct impact on leaders’ effectiveness in areas such as communication openness, mission, and role clarity. Another study found a significant positive association between the dimensions of transformational leadership and the effectiveness of classroom and organizational leadership (Pounder, 2008).

Satisfaction (SF), or “Generates satisfaction,” evaluates the employees’ satisfaction with the leaders’ methods of working with others (Avolio & Bass, 2004). Transformational leadership can increase followers’ satisfaction when leaders direct followers to identify the organization’s goals (Bartram & Casimir, 2007; Bono & Judge, 2003). In the hotel environment, the implementation of transformational leadership can be seen as a source of trust, as followers believe leaders can combine the leadership roles with personality traits (such as showing concern for the followers’ needs) (Whitener et al., 1998). According to García-Guiu et al. (2020), three of four transformational leadership dimensions are sufficient to enhance hotel employees’ job satisfaction.

The hospitality industry is characterized by strong employee–customer interactions, high intensity, and complex operations. Since hotel employees are the primary aspect of the hotel company that delivers service quality, it is very important to understand how leadership affects employee outcomes (Kim et al., 2023). Several studies on the tourism industry suggest that transformational leadership is the main factor in driving employees’ job satisfaction, organizational identification, creativity, and task performance (Tracey & Hinkin, 1994; Hinkin & Tracey, 1994).

Empirical studies in Spanish hotels have shown that most transformational leadership dimensions (such as individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and idealized influence) can increase job satisfaction among both internal employees and external workers (García-Guiu et al., 2020). A similar study in six-star hotels in Saudi Arabia, conducted after the COVID-19 pandemic, found that transformational leadership has a significant and positive effect on the employees’ engagement, job satisfaction, and psychological well-being. In addition, these variables mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and employee well-being (Abolnasser et al., 2023).

Kim et al.’s (2023) research in Korean hotels revealed that the different dimensions of transformational leadership have varying effects on the identification with the organization and creativity. One of the most direct effects of transformational leadership was an increase in employees’ identification with the organization, which in turn enhanced employees’ creativity and task performance (Kim et al., 2023). From the same point of view, Teoh et al. (2022) suggested that the dimensions of transformational leadership (especially inspirational motivation and intellectual stimulation) have significantly influenced employee performance during challenging periods (Teoh et al., 2022).

Regarding transactional leadership, research in Spanish luxury hotels found that employee outcomes (extra effort, perceived efficiency, and satisfaction) are strongly and positively associated with contingent rewards and idealized attributes (Quintana et al., 2014). Research in the Egyptian hospitality industry has shown that transactional leadership has a positive effect on organizational agility. More specifically, this relationship is mediated by organizational trust and the use of ambidexterity, with contingent rewards serving as crucial motivational tools (Elbaz et al., 2023).

On the contrary, passive leadership has been connected with negative outcomes in the tourism and hospitality industry. More specifically, a study of hotels in the United States found that passive leadership is significantly and negatively correlated with employees’ engagement (Alonderiene & Majauskaite, 2016). Research in the Turkish hotel industry revealed that laissez-faire leadership did not significantly influence job satisfaction, suggesting that this leadership style was less effective than active leadership styles (Sürücü & Sagbas, 2021).

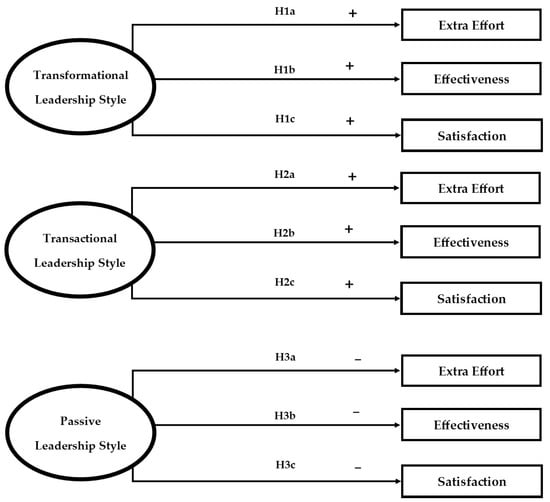

The literature review did not identify any significant empirical findings on the implementation of the MLQ measurement tool regarding the Greek hotel industry. Based on previous worldwide research, the authors formulated nine hypotheses to examine the validation and the relationship between different leadership styles and the employees’ extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction. These hypotheses, which are illustrated in Figure 1, are the following:

Figure 1.

Illustrated model of Research Hypotheses.

H1:

Transformational leadership is positively associated with the outcome of leadership.

H1a:

Transformational leadership is positively associated with the extra effort of employees.

H1b:

Transformational leadership is positively associated with the effectiveness of employees.

H1c:

Transformational leadership is positively associated with the satisfaction of employees.

H2:

Transactional leadership is positively associated with the outcome of leadership.

H2a:

Transactional leadership is positively associated with the extra effort of employees.

H2b:

Transactional leadership is positively associated with the effectiveness of employees.

H2c:

Transactional leadership is positively associated with the satisfaction of employees.

H3:

Passive leadership is negatively associated with the outcome of leadership.

H3a:

Passive leadership is negatively associated with the extra effort of employees.

H3b:

Passive leadership is negatively associated with the effectiveness of employees.

H3c:

Passive leadership is negatively associated with the satisfaction of employees.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sample

The sample for this research consists of hotel employees working in four and five-star hotels located in several areas of Greece. The Greek hotel sector is an essential industry, with a diverse structure and notable growth in the high-end market. The Hellenic Chamber of Hotels (HCH) released figures showing that Greece had 10,104 hotel units in 2024, spread over five-star categories (HCH, 2025). Analysis of the category distribution shows that the 2-star hotels are the largest group with 3251 units (32.2% of the total number of hotels). The following categories are 3-star, 4-star, and 5-star hotels (ICAP, 2025). Overall, the 3–5-star segments are 56% of the total number of hotels, hold 77% of total hotel rooms, and are responsible for 92% of the industry’s turnover; hence, these segments have the highest economic importance, although their number is lower than that of the lower-category establishments (GBR Consulting, 2025). The reason this study is limited to four- and five-star hotels is their economic importance and organizational features.

Between 2019 and 2024, the 5-star segment saw remarkable growth, with units increasing by 37% and rooms by 22%, whereas the 4-star sector rose by 14% in units and 8% in rooms (GBR Consulting, 2025). The 5-star segment in 2024 accounted for 40% of total hotel industry revenue, amounting to €11.5 billion, and the 4-star segment accounted for 39%, collectively making up 79% of the sectoral revenue (Research Institute for Tourism, 2025). Compared to smaller establishments, upscale hotels usually have a more formal corporate structure, advanced human resource management systems, and well-established leadership models, features that make it easier to conduct leadership style surveys and analyze their results (Ariza-Montes et al., 2017). Besides that, the four- and five-star hotels are the leading employers of the seasonal tourism workforce, which numbers around 900,000 in Greece. So, changes in leadership practices in these hotels will significantly affect employees’ well-being and the quality of service delivery in the Greek tourism economy (SETE, 2022).

Eventually, although the MLQ tool has been used in several different areas (such as public organizations, bank companies, and educational institutions), the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire has not been widely examined in the hotel industry; especially, in the Greek hotel industry, there is almost no empirical research to investigate the implementation of different leadership styles in hotel management.

The sampling method used for this study was stratified convenience sampling; it was applied in the main touristic areas of Greece: Chalkidiki, Crete, Attica, Peloponnese, Cyclades Islands, Dodecanese Islands, and Ionian Islands. The geographical stratification was attained by representing diverse tourism markets and different operational contexts (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016).

The hotels included in the specific study were selected from the Hellenic Chamber of Hotels (HCH) database (HCH, 2025). The hotel managers were contacted by the researchers via email or phone, and afterward, the questionnaires were sent to the managers to distribute to their subordinates. More specifically, this email invitation included a link to the online questionnaire and a brief description of the research and its purpose; it also noted that the participation was voluntary, anonymous, and complimentary.

The invitation was sent to 127 four and five-star hotels. Fifty-nine hotel managers agreed to participate in the research, twenty-three refused, and forty-five hotels did not respond. Eventually, 211 hotel employees completed the questionnaires. Data were collected from May to July 2025. All participants provided verbal consent, and the authors’ university Ethics Committee approved this study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

The electronic version of the questionnaire was hosted on Google Forms, and its form and style were designed using the Formfacade plugin. The authors had purchased the license for the specific plugin. In this version of Google Forms, there are quite a few methodological benefits such as: the participant receiving the same display in all cases, the system automatically checking the validation and the completeness of the questionnaire, the data being securely stored and encrypted, the reaction process being followed in real-time, and the number of errors made when copying the data reduced (Evans & Mathur, 2018). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample.

3.2. Research Instrument

As described in the Literature review, the measurement instrument used in this research is the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5x) by Bass and Avolio. This instrument measures supervisor’s behavior across three leadership styles: transformational, transactional, and passive leadership styles. Each leadership style consists of several dimensions. The transformational leadership style consists of five dimensions (Avolio & Bass, 2004; Ntalakos et al., 2024a):

- Idealized influence (attributed): This dimension is linked to a socially charismatic leader who is confident and assertive and channels his energies into high moral and ethical standards.

- Idealized influence (behavior): This dimension concerns the leader’s focus on the organization’s values, beliefs, and commitment to its mission and goals.

- Inspirational motivation: A characteristic of the leaders is to inspire their followers to be positive, have high aims, share a common vision, and talk with their followers to reach this vision.

- Intellectual stimulation: This aspect relates to the leader’s skill in encouraging followers to generate ideas they can use to develop solutions to their significant challenges.

- Individual consideration: This dimension refers to a leader’s ability to cater to the follower’s needs through coaching, fostering, and paying attention to them, thus making them happy.

The transactional leadership style consists of two dimensions:

- Contingent reward: This dimension outlines the roles, tasks, and requirements that the leader expects followers to perform. The followers, upon succeeding in meeting the necessary obligations, are thus rewarded both materially and psychologically.

- Management-by-exception (active): This dimension reflects an active leader whose main concern is ensuring that all standards are met.

Finally, the passive leadership style consists of two dimensions:

- Management-by-exception (passive): This dimension relates to the leader’s conduct of interfering only when noncompliance is detected or when errors have already occurred.

- Laissez-faire: In this dimension, the leader refuses to make any decisions, shirks responsibility, and does not want to exercise his authority. Basically, this kind of leader is merely an avoider of action.

Apart from the leadership styles, the MLQ tool measures the outcome of leadership. In other words, the MLQ measures employees’ behaviors related to the specific leadership styles. Employees’ behavior can be translated into extra effort, work effectiveness, and job satisfaction. All these dimensions are measured via a 5-point Likert scale: 0 = not at all to 4 = frequently, if not always.

To create a Greek version, the developers of the original instruments had to be given written permission. The adjustment process adhered to the guidelines for the back-translation methodology (Tsang et al., 2017; Kalfoss, 2019). First, two bilingual translators, both native Greek speakers with expertise in organizational behavior, independently translated the instruments from English to Greek. These two translations were combined into a single Greek version through joint discussion to resolve any differences and ensure the text’s conceptual clarity. Then, a different bilingual translator, who had no prior knowledge of the original English, translated the text from Greek back into English. The back-translated text was compared with the original instrument to identify any semantic discrepancies and confirm equivalence. The focus of this translation exchange was to maintain the essence of the concepts, the experiential components, and the semantic meanings of the items; however, these had to be in harmony with Greek cultural interpretations and linguistic norms. The differences found in the solution process were resolved through iterative refinement with consultation of a review panel with expertise in both leadership theory and the Greek organizational context. After that, the final Greek version was pilot-tested with a small group to ensure understanding and cultural suitability before its use in the main study.

3.3. Data Analysis

The research data were analyzed using the following statistical models: Descriptive statistics, Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, McDonald’s omega, Pearson coefficient, and Multiple Regression Models. The statistical programs used for the data analyses were: Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29, and Jamovi Desktop Statistical Open Software version 2.6.44.

4. Results

4.1. Examining the Validity—Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To verify the factor structure of the MLQ leadership styles instrument, the statistical technique of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used. The first leadership style examined via CFA was the transformational leadership style. CFA fit measures indicated that this model does not demonstrate good fit (only the measurement of SRMR is acceptable). Table 2 and Table 3 present these results.

Table 2.

Fit measures of CFA regarding the transformational leadership.

Table 3.

Factor loadings for the dimensions of transformational leadership.

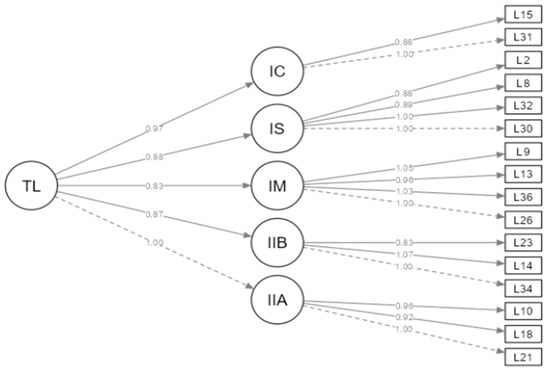

Due to the poor fit of the model, Items 6 and 29 were deleted (they had lower factor loadings), and a second-order CFA model was applied. This model showed good fit across three fit measures (CFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.899, SRMR = 0.039); thus, this model is accepted. Transformational leadership is the broader construct that explains the first-order factors (five dimensions) correlating. Figure 2 demonstrates the second-order CFA model.

Figure 2.

Second-order CFA model—Transformational leadership (Source: The figure was created by the authors).

The second leadership style of the MLQ tool (transactional leadership) was also validated through CFA methods. The results of the CFA showed a very good fit for the two dimensions of transactional leadership. Hence, the transactional leadership model is accepted for the Greek hospitality industry. More details are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Fit measures of CFA regarding transactional leadership.

Table 5.

Factor loadings for the dimensions of transactional leadership.

The third and final leadership style of the MLQ instrument (passive leadership) was validated via CFA. Similar to transactional leadership, passive leadership demonstrated a strong fit across the two dimensions. Thus, this model was accepted. Table 6 and Table 7 present model’s validity.

Table 6.

Fit measures of CFA regarding passive leadership.

Table 7.

Factor loadings for the dimensions of passive leadership.

Although the AVE in management-by-exception (passive) is low, each of the loading factors is acceptable; hence, in combination with the high values of the other fit measures, the authors decided to accept this model.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability Analysis, and Correlations

Table 7 exhibits the descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha, and McDonald’s omega. The last two coefficients are used to measure internal consistency—reliability of the variables. According to Table 8, most employees believe that, in their hotel working environment, the supervisor–manager adopts the transformational leadership style, since they have highly scored in the transformational leadership (M = 2.4327) and its dimensions. Similarly, many employees suggest that their supervisors implement the transactional leadership style (M = 2.3516) as they have also scored highly in the corresponding answers of transformational leadership (with its dimensions). On the contrary, the sample believes that their managers do not often follow a passive leadership style, as they have scored very low in this type of leadership (M = 1.3282).

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency of the variable.

Regarding the internal consistency of the leadership styles and their dimensions, both Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) have shown great consistency. Cronbach’s alpha (α) ranges from 0.630 to 0.970. Therefore, all values are acceptable and indicate good internal consistency. The same results are described in McDonald’s omega (ω), since all values range from 0.634 to 0.970.

All variables and their dimensions were examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality. The variables of leadership styles, their dimensions, and the outcomes of the leadership follow the normal distribution. Hence, to examine the correlations among the variables, the Pearson coefficient was used (Table 9). According to Table 9, transformational leadership exhibits very strong, positive, and significant correlations with all its dimensions as well as transactional leadership (and its dimensions); moreover, transformational leadership is significantly and positively related to leadership outcomes (extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction). On the contrary, transformational leadership shows a low, non-significant correlation with passive leadership and only one of its dimensions (laissez-faire). Similarly, the transactional leadership style (combined with its dimensions) shows strong and significant positive correlations with the three leadership outcomes. In contrast, transactional leadership is significantly lower and negatively connected with the two dimensions of passive leadership. Eventually, passive leadership is low and negatively correlated with extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction.

Table 9.

Correlations of the variables (Pearson Coefficient).

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

The first hypothesis, “H1. Transformational leadership is positively associated with the outcome of leadership,” includes three sub-hypotheses. To examine Hypothesis H1a (“Transformational leadership is positively associated with the extra effort of employees”), a multiple regression analysis was conducted. More specifically, the dimensions of transformational leadership are strongly, positively, and significantly associated with employees’ extra effort (). More specifically, the dimensions of transformational leadership can explain 82.3% of the extra effort. According to the sig. Column of Table 10, two dimensions are associated significantly with the variable of extra effort: idealized influence—attributed (p < 0.001), and individual consideration (p < 0.001). In other words, one unit of idealized influence—attributed can increase extra effort by 0.462 units, and one unit of individual consideration can increase extra effort by 0.319 units. Hence, hypothesis H1a is accepted.

Table 10.

Multiple Regression Model Measures for Hypothesis H1a.

Similar results were demonstrated regarding the second multiple regression model (Hypothesis H1b: “Transformational leadership is positively associated with the effectiveness of employees”). The results indicated that the dimensions of transformational leadership are strongly, positively, and significantly associated with employees’ extra effort (). More specifically, the dimensions of transformational leadership can explain 86.3% of the effectiveness. According to the sig. in Table 11, three dimensions are significantly associated with the variable of effectiveness: idealized influence—attributed (p < 0.001), individual consideration (p < 0.001), and individual consideration (p < 0.001). In other words, one unit of idealized influence—attributed can increase effectiveness by 0.343 units, one unit of individual consideration (p < 0.001) can increase effectiveness by 0.194 units, and one unit of individual consideration can increase effectiveness by 0.270 units. Hence, hypothesis H1a is accepted.

Table 11.

Multiple Regression Model Measures for Hypothesis H1b.

The third hypothesis (Hypothesis H1c: “Transformational leadership is positively associated with the satisfaction of employees”) was also examined using a multiple regression analysis model. The results showed that the dimensions of transformational leadership are strongly, positively, and significantly associated with employees’ satisfaction (). More specifically, the dimensions of transformational leadership can explain 82.9% of satisfaction. According to the sig. in Column of Table 12, two dimensions are significantly associated with the satisfaction variable: idealized influence—attributed (p < 0.001), and individual consideration (p < 0.001). In other words, one unit of idealized influence—attributed can increase satisfaction by 0.404 units, and one unit of individual consideration can increase satisfaction by 0.421 units. Hence, hypothesis H1c is accepted.

Table 12.

Multiple Regression Model Measures for Hypothesis H1c.

From the same point of view, similar results were revealed regarding the transactional leadership style and the outcome of leadership. These results refer to the second set of hypotheses H2. More specifically, the fourth multiple regression model showed a strong and positive relationship between transactional leadership and extra effort (). In particular, the one unit of contingent reward increases the variable of extra effort by 0.976 units. Hence, H2a hypothesis (H2a “Transactional leadership is positively associated with the extra effort of employees”) is accepted. More details are described in Table A1 of the Appendix A. Moreover, the fifth multiple regression model revealed a strong and positive association between transactional leadership and effectiveness (). In particular, the one unit of contingent reward increases the variable of effectiveness by 0.894 units. Hence, H2b hypothesis (H2b “Transactional leadership is positively associated with the effectiveness of employees”) is accepted. More details are described in Table A2 of the Appendix A. Finally, the sixth multiple regression model revealed a strong and positive relationship between transactional leadership and satisfaction (). In particular, the one unit of contingent reward increases satisfaction by 0.898 units. Hence, H2c hypothesis (H2c “Transactional leadership is positively associated with the satisfaction of employees”) is accepted. More details are described in Table A3 of the Appendix A.

The last set of hypotheses (H3a, H3b, and H3c) examines the association of passive leadership with the variables of extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction. More specifically, the seventh multiple regression model showed a significant and negative relationship between laissez-faire and extra effort (). Especially, the one unit of laissez-faire decreases the variable of extra effort by 0.643 units. On the contrary, the dimension of management-by-exception (passive) shows a positive relationship between this dimension and extra effort (one unit of MBEP increases the variable of extra effort by 0.334 units). Hence, H3a hypothesis (H3a “Passive leadership is negatively associated with the extra effort of employees”) is partially accepted. More details are described in Table A4 of the Appendix A. The eighth multiple regression model showed a significant and negative relationship between laissez-faire and effectiveness (p = 0.000 < 0.001). Especially, the one unit of laissez-faire decreases the variable of effectiveness by 0.661 units. On the contrary, the dimension of management-by-exception (passive) shows a positive relationship with effectiveness (one unit of MBEP increases effectiveness by 0.444 units). Hence, H3b hypothesis (H3b “Passive leadership is positively associated with the effectiveness of employees”) is partially accepted. More details are described in Table A5 of the Appendix A. The ninth and final multiple regression model showed a significant and negative relationship between laissez-faire and satisfaction (p = 0.000 < 0.001). Especially, the one unit of laissez-faire decreases the variable of satisfaction by 0.726 units. On the contrary, the dimension of management-by-exception (passive) shows a positive relationship between this dimension and satisfaction (one unit of MBEP increases the variable of satisfaction by 0.454 units). Hence, H3c hypothesis (H3c “Passive leadership is negatively associated with the satisfaction of employees”) is partially accepted. More details are described in Table A6 of the Appendix A.

5. Discussion

The primary purpose of the present study was to investigate the implementation of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire in the Greek hotel industry. Additionally, the authors examined the relationships between transformational, transactional, and passive leadership and their associations with employee outcomes (extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction). The results largely confirm the proposed hypotheses and align with the latest empirical studies in international hospitality research, while also uncovering undetected patterns specific to the Greek hotel context (García-Guiu et al., 2020; Abolnasser et al., 2023).

The results of this research strongly support Hypothesis H1 and its sub-hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H1c), demonstrating that transformational leadership significantly and positively associates with the three employees’ outcome variables. To be more precise, the two dimensions—idealized influence attributed and individualized consideration—were singled out as the most significant predictors of extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction. These results align with recent systematic studies that consistently identify transformational leadership as a key factor in enhancing employees’ satisfaction, motivation, and performance regarding the hospitality industry (Ali, 2024; Kim et al., 2023). The range of (82.3% to 86.3%) found in this study is indicative of the high association that transformational leadership has in the Greek hotel sector, possibly even to a greater extent than in other environments (Filani et al., 2025).

The strong impact of idealized influence across all three outcomes aligns with current research highlighting the critical role of trust-building and ethical leadership in the hospitality sector (Abolnasser et al., 2023). In the post-COVID-19 era, employees increasingly seek leaders who are faithful to their words and possess strong moral principles. Previous research shows that these leaders’ attitudes have a profoundly positive impact on the psychological well-being and job satisfaction of hotel employees (Abolnasser et al., 2023). The Greek hotel environment, characterized by strong interpersonal relationships and collectivistic cultural values, may further emphasize the significance of idealized influence as employees seek leaders who are trustworthy and ethical (García-Guiu et al., 2020).

Similarly, the major association of individualized consideration on employee outcomes aligns with recent findings from worldwide hospitality research. Kim et al. (2023) found that individualized consideration directly leads to organizational identification and creativity among Korean hotel employees, resulting in increased task performance. Regarding the Spanish hotel industry, García-Guiu et al. (2020) found that individualized consideration was one of three transformational factors sufficient to raise the level of job satisfaction among internal employees and outsourced workers. The characteristics of caring and support for development seem to be very important among hotel employees, as they often work in stressful situations, are at the frontline of customer service, and must perform emotional labor (Helalat et al., 2025).

One of the most interesting discoveries of this research is that intellectual stimulation shows a significant association with effectiveness alone, while the relationship with extra effort and satisfaction has not been observed. Although intellectual stimulation is associated with creative thinking, which usually elevates perceptions of productivity and organizational effectiveness, it may not induce employees to a higher level of extra effort or personal satisfaction (Teoh et al., 2022). Additionally, contemporary research in the Malaysian hospitality industry has revealed that the primary role of intellectual stimulation is to initiate creative problem-solving and the adoption of new behaviors, rather than quickly generating positive emotions such as satisfaction (Teoh et al., 2022). As a result, the Greek hotel sector, which is progressively focusing on service innovation and differentiation, can serve as a source of inspiration for leaders, helping them develop new solutions to operational issues (Shafi et al., 2020).

That employee outcomes are primarily influenced by transformational leadership is consistent with recent theoretical advances that question the traditional linear perspective on the impact of leadership styles on performance. Ali (2024) conducted a meta-analysis of transformational leadership in tourism and hospitality settings, revealing that the path by which transformational behaviors affect outcomes is significantly more complex than previously thought. It was previously known that contextual moderators, such as organizational size, market segment, and cultural dimensions, highly modify the strength and direction of the effects. This more context-dependent view is well supported by Helalat et al. (2025), whose study of hotels in Jordan found that work engagement is the primary mediator of the effect of transformational leadership on employee performance, indicating that the leadership-outcome link is indirect, operating through engagement. Likewise, Filani et al. (2025) illustrated in their study of Lagos hotels that the success of transformational leadership varies widely depending on organizational infrastructure and HR practices, with leadership behaviors having a greater impact in organizations with a strong performance management system.

These recent works change our perspective by focusing not on whether transformational leadership has an effect, but on how and under what conditions it leads to better results. This change in focus has significant implications for the interpretation of our Greek hotel data, in which the level of idealized influence and individualized consideration may be indicative of particular cultural expectations regarding leader-follower relationships in Mediterranean organizational environments.

Moreover, the findings of this study strongly support Hypothesis H2 with its sub-hypotheses (H2a, H2b, H2c), indicating that transactional leadership is positively associated with extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction. In fact, contingent reward was the only significant facet of transactional leadership, showing strong positive associations with all three outcomes ( values varying between 74.9% and 85.7%). This outcome is supported by another study of Spanish luxury hotels, which identified contingent reward as the most influential factor in positive employee outcomes (Quintana et al., 2014).

It is worth noting that management-by-exception (active) surprisingly did not have a significant association in this research. On the contrary, several previous studies indicate its important role in maintaining performance standards (Hinkin & Schriesheim, 2008). This result may indicate a cultural preference in the Greek hospitality sector for positive reinforcement over corrective action. In addition, this result may suggest that the monitoring and corrective aspects of transactional leadership, which are aimed at service environments, are less effective in those environments that require a high degree of autonomy and initiative (Elbaz et al., 2023; Ali et al., 2024). Another contemporary study in hospitality suggests that although contingent rewards remain effective, excessive monitoring may negatively affect employees’ inspirational motivation and creativity, which are essential for providing excellent service (Book et al., 2019).

The research findings partially support Hypotheses 3 and its sub-hypotheses (H3a, H3b, H3c), revealing a complex pattern. On one hand, laissez-faire leadership is negatively associated with the three outcome variables (extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction). On the other hand, management-by-exception (passive) surprisingly associates positively with these variables. The strong negative impact of laissez-faire leadership on extra effort (β = −0.643), effectiveness (β = −0.661), and satisfaction (β = −0.726) confirms recent research, which emphasized the catastrophic effects of passive leadership in the hospitality industry (Sürücü & Sagbas, 2021; Che et al., 2017).

The passive leadership results align with previous systematic reviews indicating that a laissez-faire leadership style increases job stress, workplace bullying, and emotional exhaustion; at the same time, it lowers job confidence and satisfaction in the hospitality industry (Guchait et al., 2016; Glambek et al., 2018). The lack of a leader’s intervention appears to be particularly important in the hotel industry, where employees are in a continuous and unpredictable interaction with customers and service problems that must be solved immediately with the help of a supervisor (Skogstad et al., 2007). According to Sürücü and Sagbas’s (2021) research on the Turkish hotel industry, the laissez-faire leadership style does not have a significant effect on job satisfaction, suggesting that it is incompatible with the dynamic, high-interaction nature of the hospitality environment (Sürücü & Sagbas, 2021).

On the contrary, the surprising positive associations between management-by-exception (passive) and all three outcome variables create a fascinating paradox that warrants cautious interpretation. This result differs from the conventional MLQ theory, which assumes that passive management-by-exception is a source of negative leadership behavior (Avolio & Bass, 2004). A potential reason for that can be found in recent research on leadership autonomy and employees’ empowerment in the hospitality environment. Baum (2015) highlighted that it is very important for the frontline employees to be empowered and able to make decisions without frequently consulting their supervisors. Under these circumstances, the passive management-by-exception dimension may not be considered a neglectful absence, but rather a delegation of authority and trust in employees’ competencies (Zhang & Bartol, 2010).

This interpretation aligns with recent research on servant and empowering leadership styles, which indicates that usually effective leaders refrain from dominating as they give their subordinates the opportunity to use their own judgment and creativity (Liden et al., 2015). In the Greek hotel industry, where experienced hospitality professionals are typically highly knowledgeable in operations, the lack of interference in daily activities (a feature of passive management-by-exception) may actually lead to an increase in autonomy, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. Nevertheless, this positive effect must be distinguished from the actual transfer of responsibility, which is a characteristic of laissez-faire leadership. Although management-by-exception (passive) refers to leaders who intervene when needed while maintaining distance most of the time, laissez-faire leaders avoid involvement even when help is obviously required (Hinkin & Schriesheim, 2008).

Recent studies have started to investigate these differences more carefully. Skogstad et al. (2015) found that the impact of laissez-faire leadership could spread over time; hence, the non-significant effects at the beginning could become significantly negative in longitudinal studies. According to Bagheri et al. (2015), the he long-term detrimental effects of a passive leadership style can erode organizational culture and employees’ well-being. Future research should focus on longitudinal designs to test whether the seemingly positive effects of management-by-exception (passive) remain valid over time or represent a temporary perception of autonomy that later turns into the feeling of being left alone.

6. Theoretical Implications

The findings of the present study contribute to the evidence that the Multiple Multifactor Questionnaire is a universally valid concept in the hospitality industry; this study also uncovered significant cultural and contextual differences. The main association of transformational leadership in explaining employee outcomes, along with the helping effect of contingent reward from transactional leadership, indicates that leadership in the Greek hotel environment requires a balanced approach. On the one hand, leaders should inspire and develop their employees with the implication of transformational leadership methods. On the other hand, supervisors should provide recognition structures through transactional mechanisms (Bond, 1998; Prabowo et al., 2018).

The MLQ’s successful validation in the Greek hospitality industry has a profound impact not only on cross-cultural leadership research but also on the revelation of cultural differences in leadership measurement. A series of recent studies on the Full Range Leadership Model’s validation across diverse cultures has shown that, while the model is universally applicable, it may require local adjustments.

To illustrate, Batista-Foguet et al. (2021), through their work with Spanish and American samples, challenged traditional beliefs about reflective measurement by uncovering formative factor structures in the MLQ, suggesting that cultural contexts shape how leadership dimensions form higher-order constructs. Meanwhile, Gruszczynska et al.’s (2022) Polish validation study culminated in an 18-item short form with a 3-factor structure comprising transformational-supportive, inspirational goal-oriented, and passive–avoidant leadership, thereby demonstrating that factor reduction is possible without compromising construct validity across various organizational settings. In their work with Iranian medical faculty, Bagheri et al. (2015) had to limit the MLQ to 18 items across six subscales, underscoring the need for adaptations to the instrument when working with Middle Eastern cultural norms and organizational hierarchies.

On the other hand, African studies of validation present contradictory results: while Ugwu and Okojie (2016) managed to reconfirm the full nine-factor MLQ structure in Nigerian organizational environments, Adarkwah and Zeyuan (2020) revealed a low correlation between the self-reported transformational leadership of the principals and teachers’ motivation in the Ghanaian schools. The current Greek hotel research, which managed to validate the nine-factor model except for having to use a second-order model for the removal of two items, thereby indirectly conforming to the comprehensive figures of the validation studies and implying that the Mediterranean hospitality cultures might be structurally similar to the Western organizational contexts, yet they operate differently.

Leading a Greek hotel team based on idealized influence (attributed) and individualized consideration, which prominently predicts staff behaviors, is not alien to, and even extends, a picture of recent international hospitality and organizational studies; at the same time, it uncovers local preferences in leadership behaviors. Carter et al. (2024) report that ‘personalized leadership’ was the most potent predictor of outcomes () in the Australian pharmacy setting, which is conceptually in line with the individualized consideration component that this study has identified; thus, the relationally focused leadership is possibly a dominant theme in the service-oriented professions of varying cultural backgrounds. The Nigerian validation work by Ugwu and Okojie (2016) also emphasized the transformational elements. However, it acknowledged that factors such as hierarchical organizational structures and power distance modulated the implementation of idealized influence behaviors in African organizations.

On the other hand, a Polish study identified inspirational, goal-oriented, and transformationally supportive leadership as distinct factors rather than as merged constructs (Gruszczynska et al., 2022), suggesting that the visionary and supportive sides of transformational leadership in Central European regions might be more independent. Such comparative results suggest that the core structures of the Full Range Leadership Model exhibit stable, universal applicability; nevertheless, cultural values, organizational contexts, and industry-specific demands moderate the relative significance and manifestations of particular leadership facets. Trust-building (idealized influence attributed) and providing personalized developmental support (individualized consideration) carried out in the Greek hotel industry probably point to the overlap of the Mediterranean cultural values that emphasize collectivism, the family business model widely seen in Greek hospitality, and the need for a high-touch service that is typical of the tourism sector. This cross-cultural interaction implies that leadership training programs should not only be tailored to organizational contexts but also to the specific cultural backgrounds of leaders and followers, thus going beyond Avolio and Bass’s (2004) initial claim of universal applicability to culturally intelligent implementation.

7. Practical Implications

The result of this research provides practical insights for hotel managers and HR professionals in the Greek hospitality sector. First, leadership development initiatives must align the training with the dimensions of idealized influence and individualized consideration, which, according to research, have the strongest effects on employee outcomes. For instance, specific ethical decision-making, trust-building communication, and personalized developmental support models could focus on providing developmental support to meet employees’ diverse needs (Abolnasser et al., 2023). Second, the organization should establish strong contingent reward systems that clearly connect performance, recognition, and promotion, as this transactional element has a considerable positive impact on motivation and satisfaction (Elbaz et al., 2023).

Hotel companies should develop psycho-structured leadership projects that combine formal education and experiential learning (Viterouli et al., 2025b). Recent studies in the hospitality industry have shown that a leadership training program is more successful when it incorporates role-playing, case study analysis of actual hotel situations, and a mentoring relationship between a senior leader and an emerging leader (Tracey & Hinkin, 1994). These programs should address the unique challenges of the hospitality environment, such as managing diversity and multicultural teams, handling customer service situations under pressure, and maintaining employee morale during seasonal fluctuations (Kara et al., 2013). Greek hotels should establish leadership academies or partnerships with hospitality management institutions to offer continuous professional development opportunities for supervisors and managers.

To implement individualized consideration, hotel managers must develop intricate employee assessment and development systems. Hotels are required to formulate personalized development plans for every employee. These plans would be related to specific career aspirations, skill deficits, and learning preferences (Kim et al., 2023). The content of regular one-to-one meetings between supervisors and subordinates should not only focus on performance evaluation, but also personal growth, career progression, and even work–life balance concerns (Khan et al., 2020). According to recent research on international hotels, leaders demonstrate a genuine interest in employees’ personal development and career goals, employees’ turnover intentions are significantly reduced, and their organizational commitment increases (Book et al., 2019). Greek hotels operating in competitive tourism markets could thus become employers of choice by differentiating themselves through investment in comprehensive employee development programs that manifest individualized consideration.

Recognition and reward systems should be restricted to guarantee their transparency, fairness, and alignment with the organization’s values. Contemporary research in luxury hotels indicates that the most effective contingent reward systems must provide a combination of incentives (such as bonuses, pay increases, and profit-sharing) as well as non-monetary recognition (such as employee-of-the-month programs, public acknowledgment, extra responsibilities, and career advancement opportunities) (Quintana et al., 2014). Hotels should define clear performance standards that employees understand and consider attainable. For these reasons, the reward criteria should be objective, measurable, and consistently applied across all departments (Elbaz et al., 2023). Moreover, recent research in the Egyptian hospitality sector reveals that when employees perceive reward systems as fair and transparent, they are more engaged with the organization (Elbaz et al., 2023). In the Greek hotel industry, hotel companies may benefit from real-time recognition tools, enabling managers and coworkers to instantly recognize excellent performance, which could foster a culture of continuous positive reinforcement.

Hotels’ human resource departments must create detailed recruitment and selection processes to evaluate candidates’ fit with transformational leadership cultures (Belias et al., 2025; Ntalakos et al., 2024b). Research within the hospitality sector has shown that when hotels hire individuals who recognize the need for ethical leadership and for teamwork, then transformational leadership practices are strengthened (García-Guiu et al., 2020). The selection interview should comprise behavioral questions that evaluate the candidates’ attitudes towards ethical dilemmas, their willingness to receive feedback, and their ability to work independently without much supervision (Filani et al., 2025). Furthermore, hotels should invest in comprehensive onboarding programs that introduce the hotel’s values, explain leadership expectations, and inform new employees about development resources, so they are aware of the hotel’s leadership culture from their first day (Abolnasser et al., 2023).

The focus of hotels’ performance management systems must shift towards integrating both outcome-based metrics and the behavioral aspects of leadership effectiveness. Teoh et al. (2022) discovered that conventional systems for performance evaluation, which usually emphasize financial results or customers’ satisfaction scores, may lead to the unintended consequence of merely facilitating the increase in transactional leadership behaviors by managers while ignoring the transformational ones. Therefore, hotels are recommended to install 360-degree feedback instruments that allow employees to express their opinions on their supervisors’ leadership behaviors. This would provide valuable data for leadership development interventions (Hinkin & Tracey, 1994). These evaluations should be conducted regularly and include specific action planning sessions, during which managers receive coaching in areas of development identified through the feedback (Kim et al., 2023). Greek hotels may use leadership effectiveness as a benchmark for measuring managers’ performance; hence, decisions on managers’ salaries and promotions may be partially based on employee feedback on leadership quality.

To reverse the effects of laissez-faire leadership style, hotels need to combat such a style actively. Organizations should regularly conduct leadership effectiveness assessments using valid instruments, such as the MLQ, to identify managers who exhibit high levels of passive–avoidant dimensions (Avolio & Bass, 2004). When a leader is identified as passive, the response should be immediate coaching through the manager’s intervention. The coaching focus should be on increasing the leader’s visibility, being more responsive to employees’ concerns, and more proactive in solving problems (Skogstad et al., 2007). Recent research in the Turkish hospitality industry reveals that laissez-faire leadership is more prevalent during periods of high workload and stress. As a result, during these periods, it is better to offer relaxation rather than additional work or support, and resources should also be empowered during peak seasons and in the face of operational challenges (Sürücü & Sagbas, 2021). Hotels should establish clear mechanisms to ensure that managers maintain regular contact with their employees, respond promptly to their requests, and actively participate in the department’s work, rather than remaining passive and isolated in administrative roles.

The key problems of the hospitality industry, such as high employee turnover, emotional exhaustion, and work–life imbalance, require targeted leadership interventions. Transformational leaders who focus on employees’ well-being, maintain their own work–life balance, and foster supportive team atmospheres have great potential to reduce employee burnout and the intention to quit (Abolnasser et al., 2023). Greek hotels should implement wellness programs that encompass stress management, offer employees flexible schedules, and regularly assess employees’ mental health and satisfaction in the hotel industry (Kara et al., 2013). By training leaders, managers could recognize burnout symptoms in employees, especially when they have lost their enthusiasm, have become absent, and the quality of service has been lowered without even notifying them. As a result, managers should respond by having supportive conversations and providing assistance to their employees before the problems escalate (Guchait et al., 2016). Hotels should plan to create cultures in which discussing job stress is a regular occurrence and in which people, rather than being stigmatized, are encouraged to seek support.

Furthermore, hotel companies need to leverage the use of the internet to enhance leadership effectiveness. Online platforms can facilitate more frequent and in-depth leader-member interactions, especially in large hotels where physical proximity between supervisors and employees may be limited (Book et al., 2019). Mobile applications can facilitate real-time recognition, allowing managers to instantly acknowledge excellent performance and share positive feedback with the entire team (Elbaz et al., 2023). Hotels are required to subscribe to learning management systems that offer employees unlimited access to professional development resources, enabling individualized consideration by accommodating different learning preferences and schedules (Filani et al., 2025). Additionally, data analytics tools can help identify trends in employees’ performance, engagement, and satisfaction. This could enable managers to take more proactive and personalized leadership actions (Teoh et al., 2022).

Greek hotels operating in family-owned or small-to-medium companies face leadership issues distinct from those in big companies and require a culturally sensitive approach. The research shows that in family-run hotel companies, leadership succession planning is the most important, as young employees of these family companies may not have received management training or may find it difficult to obtain the approval of the employees who have been with the company for a long time (Ariza-Montes et al., 2017). These types of organizations should consider external leadership coaching and mentoring programs to guide new leaders in acquiring the necessary transformational skills while preserving traditional organizational cultures (García-Guiu et al., 2020). Small hotels may not have a human resource department, and hence owner–managers must be provided with learning training that equips them with knowledge of employee development, performance management, and conflict resolution (Sürücü & Sagbas, 2021).

Finally, organizations in the hotel industry and hospitality education institutions in Greece should collaborate to establish leadership standards and certification programs that are valid throughout the hospitality industry. Recent research reveals that adopting specific leadership frameworks enables these organizations to share knowledge, benchmark, and achieve continuous improvement across the sector (Kim et al., 2023). One way these institutes can contribute to leadership excellence is by creating leadership excellence awards. These awards would acknowledge the hotels that demonstrate admirable leadership behaviors, encourage positive competition among hotels, and push organizations to dedicate more resources to leaders’ development (Tracey & Hinkin, 1994). Furthermore, hospitality management programs should integrate research-based leadership training that equips students with knowledge of leadership theories and the skills to practice both transformational and transactional leadership effectively in the hospitality industry (Teoh et al., 2022). The Greek hospitality industry will become more competitive, offer a better quality of service, and create better working conditions for thousands of tourism employees.

8. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this paper is instrumental in shedding light on hospitality leadership in Greece and in adapting the MLQ to a novel cultural context, several methodological and conceptual constraints need to be recognized. Additionally, there are suggestions for further studies that could build on and expand these results.

A relatively small sample size of 211 hotel employees that barely meets the minimum requirements for structural equation modeling (Wolf et al., 2013) is undoubtedly a limitation when validating complex multidimensional instruments such as the MLQ. According to the latest methodological guidelines, CFA models typically require 200–400 respondents to yield reliable results, especially when they include several latent factors with moderate-to-high loadings (Gaskin et al., 2025; Wolf et al., 2013). The sample in this study demonstrated adequate fit indices. The factor loadings in the study were, by and large, strong (most items exceeded 0.60); however, a larger sample would be more statistically sound, allowing detection of minimal differences between leadership dimensions, and would also provide greater generalizability. Subsequent validation studies in the Greek hospitality field would do well to include a sample of 300–500 participants to obtain more reliable parameter estimates and greater confidence in the factor structure’s invariance across different hotel segments and areas.

The cross-sectional design used in this paper has inherent limitations in this type of research and limits causal inference; at the same time, it might be a source of standard method variance (CMV). The entire dataset was collected at a single point in time via employee self-reports, which, in addition to shared method variance, might further inflate the correlation between the variables (So et al., 2025). Even though the authors tried to reduce confusion and bias (e.g., by maintaining respondents’ confidentiality and segmenting the predictor and outcome variables on the same questionnaire), they still could not eliminate CMV.

Several methodological investigations in the hospitality industry have shown that longitudinal studies significantly reduce standard method bias and improve construct validity compared to cross-sectional studies (So et al., 2025). Research that attempts to replicate the study’s results, using longitudinal methods with multiple measurement moments, is necessary to verify the temporary stability of the MLQ factor structure, identify changes in leadership styles and their effects, and provide support for causal relationships between leadership behaviors and employee outcomes.

Moreover, a multi-source approach to data collection (e.g., 360-degree assessments that include self-reports, peer evaluations, and subordinate ratings) would not only eliminate single-source bias but also provide a more comprehensive picture of leadership effectiveness (Antonakis et al., 2003).

The research was limited to four- and five-star hotels, so the findings cannot be generalized to other segments of the hospitality industry (e.g., budget hotels, boutique establishments, or restaurants). The unique features of upscale hotels, such as more formal hierarchies, greater organizational resources, and typical service expectations, may affect how leadership behaviors are expressed and how employees perceive them. Subsequent studies need to broaden MLQ validation across various hospitality contexts, including small-to-medium family-owned hotels, which constitute the majority of the Greek tourism sector; seasonal resort properties with temporary workforces; and other service sectors beyond hotels.

In addition, cross-cultural comparative studies investigating MLQ measurement invariance between Greek hotels and hospitality organizations and those in other Mediterranean countries (e.g., Italy, Spain, Portugal) will reveal the extent to which the current results reflect pan-Mediterranean cultural values rather than solely Greek organizational dynamics.

Even though the model fit is acceptable, it is necessary to recognize that removing two items from the transformational leadership scale and adopting a second-order factor structure may represent areas for refinement of the instrument. Recent critical reviews of the MLQ have revealed persistent psychometric issues, including very high intercorrelations among the dimensions of transformational leadership and difficulty differentiating some transactional and passive behavior types (Batista-Foguet et al., 2021). It raises a new question: why is there a positive correlation between management-by-exception (passive) and employee outcomes? This relationship should be studied further using qualitative research methods. Further research should be conducted using a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative validation with qualitative interviews, to examine how Greek hotel employees and managers understand and experience various leadership behaviors in real life. The findings could pave the way for culturally sensitive versions of the MLQ that retain cross-cultural comparability while capturing the nuance of context-specific leadership.