Abstract

This study explores the relationship between Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) quality and team cohesion within the Croatian banking sector. Drawing from relationship-based leadership theories, we investigate how the quality of dyadic relationships between leaders and team members influences team cohesiveness in a hierarchical, regulated organizational environment. Using validated instruments (LMX-7 and adapted Group Environment Questionnaire), we surveyed 76 employees across 10 teams. Results demonstrate a strong positive correlation between LMX quality and team cohesion (r = 0.854, p = 0.002). Our findings contribute to understanding how relationship-based leadership practices can foster stronger team dynamics in knowledge-intensive organizational contexts, with implications for leadership development in banking and similar professional services sectors.

1. Introduction

Leadership research has progressively evolved from trait-based paradigms toward relationship-centered approaches that emphasize the quality of interactions between leaders and team members (Northouse, 2010). Among these frameworks, Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory has emerged as a particularly robust lens, recognizing that leaders develop differentiated relationships with individual team members (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). These relationships range from high-quality exchanges characterized by mutual trust, respect, and reciprocal obligations to low-quality exchanges that remain transactional and limited to formal role requirements.

Simultaneously, organizational scholarship has identified team cohesion—reflecting interconnectedness, solidarity, and unity—as crucial for team effectiveness, particularly in knowledge-intensive contexts (Salas et al., 2005). In banking environments, where complex financial products, regulatory compliance, and risk management require seamless coordination among specialists, team cohesion becomes essential for operational excellence. Despite extensive independent research on LMX and cohesion, empirical evidence linking these constructs within the regulated, hierarchical environment of banking remains scarce. While theoretical reasoning suggests that high-quality exchanges foster psychological safety and shared identity that strengthen cohesion, systematic empirical testing of these propositions remains nascent.

Recent empirical evidence from 2024 has begun to illuminate the complex mechanisms through which LMX influences team dynamics. In the banking sector, Dar et al. (2024) demonstrated that psychological safety serves as a critical mediating mechanism linking LMX quality to discretionary work behaviors. Similarly, Bormann and Brattström (2024) highlighted the importance of LMX differentiation, finding that variability in relationship quality significantly predicts followers’ psychological strain. Furthermore, Yao et al. (2024) revealed that LMX quality amplifies the beneficial effects of positive leadership emotions on team psychological safety, while Bennouna et al. (2024) confirmed that high-quality relationships promote safety compliance in high-risk environments.

This study addresses these theoretical and empirical gaps by investigating the relationship between LMX quality and team cohesion within banking sector teams. Specifically, we examine the primary association between LMX and overall cohesion, the dimensional specificity regarding task and social cohesion, and the influence of contextual factors. Our research contributes by extending LMX theory beyond a dyadic focus to examine how aggregated relationship quality influences collective team properties.

We conducted this research in a Croatian banking institution. The banking sector provides an ideal empirical context given its combination of hierarchical structures and knowledge-intensive teamwork. Moreover, Croatia represents a distinct empirical setting characterized by the post-transitional context of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). This environment typically exhibits a unique duality: high power distance and adherence to formal hierarchy, coexisting with collectivist cultural norms where interpersonal relationship connections are pivotal for business operations.

To address these objectives, this study poses the following Research Questions (RQs): RQ1: Is there a positive relationship between average LMX quality and overall team cohesion in banking teams? RQ2: How does LMX quality differentially relate to task cohesion, social cohesion, and individual attraction to the group? RQ3: Does the relationship between LMX and cohesion remain robust when controlling for team size and tenure?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory: Evolution and Core Principles

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory represents a fundamental shift from traditional leadership approaches by focusing on the dyadic relationship between a leader and each individual member (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Rooted in social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), LMX posits that leaders develop differentiated relationships with subordinates based on interpersonal compatibility and trust. These relationships range from high-quality exchanges—characterized by mutual trust, respect, and reciprocal obligations—to low-quality, transactional exchanges limited to formal role requirements (Dansereau et al., 1975).

The evolution of LMX theory has progressed from the initial discovery of “vertical dyad linkages” and the identification of in-groups and out-groups, toward a more prescriptive “Leadership Making” model. This later stage advocates that effective leaders should strive to develop high-quality partnerships with all team members rather than selectively privileging a few, thereby democratizing relationship quality (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Contemporary research has further expanded to a multilevel perspective, recognizing that dyadic relationships do not exist in a vacuum but aggregate to influence team-level outcomes. This systems-level view investigates how the average quality of relationships (LMX mean) and the variability of those relationships (LMX differentiation) within a team collectively shape the social architecture and effectiveness of the work unit (Henderson et al., 2009).

2.2. Team Cohesion: Conceptualization and Dimensions

Team cohesion represents “the total field of forces which act on members to remain in the group” (Festinger, 1950, p. 274), reflecting both interpersonal attraction and commitment to group goals and tasks. Cohesion manifests as psychological unity, emotional bonding, and collective identification that motivate members to maintain membership and coordinate efforts (Carless & De Paola, 2000). In organizational contexts, cohesive teams demonstrate shared understanding, mutual support, open communication, effective coordination, and resilience when facing challenges (Beal et al., 2003).

Early cohesion research treated the construct unidimensionally, but contemporary frameworks recognize distinct facets. Carron et al. (1985) developed the Group Environment Questionnaire distinguishing between: (1) task cohesion—degree of unity and commitment toward achieving group objectives; and (2) social cohesion—interpersonal attraction and quality of member relationships independent of task pursuits. Additionally, they differentiated individual versus group referents, yielding four dimensions: individual attractions to group-task, individual attractions to group-social, group integration-task, and group integration-social.

Building on this foundation, Carless and De Paola (2000) adapted the framework for work teams, proposing three core dimensions particularly relevant to organizational settings:

Task Cohesion refers to collective commitment to achieving shared goals, coordinating efforts, and maintaining focus on work objectives. In task-cohesive teams, members understand their interdependencies, align individual contributions with collective aims, and persistently pursue performance targets despite obstacles (Beal et al., 2003).

Individual Attraction to Group captures personal satisfaction with team membership and desire to maintain affiliation. This dimension reflects the extent to which individuals find the team personally rewarding, compatible with their values, and worthy of continued involvement (Carless & De Paola, 2000).

Social Cohesion encompasses interpersonal relationship quality, including friendship bonds, social support, enjoyment of interactions, and emotional connections among members. Socially cohesive teams feature trust, mutual respect, open communication, and willingness to spend time together beyond work requirements (Festinger, 1950).

Research identifies multiple factors influencing cohesion development. Team composition factors include size (smaller teams typically more cohesive), similarity among members (homogeneity facilitating bonding), and stability (longer tenure enabling relationship development). Structural factors encompass task interdependence (requiring coordination), proximity (physical or virtual), and clearly defined roles. Leadership behaviors including participative decision-making, supportive communication, and fair treatment also foster cohesion (Salas et al., 2005).

Cohesion consequences are predominantly positive. Meta-analyses demonstrate moderate to strong relationships between cohesion and team performance (Beal et al., 2003), with effects particularly pronounced when performance depends on behavioral processes rather than simply aggregating individual contributions. Cohesive teams exhibit superior communication effectiveness, enhanced knowledge sharing, more constructive conflict resolution, greater member satisfaction, reduced absenteeism and turnover, and increased innovation (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009). However, research also documents potential downsides including groupthink, resistance to change, and social loafing when cohesion develops around social rather than task dimensions without performance norms.

2.3. Linking LMX and Team Cohesion: Theoretical Mechanisms

Although LMX and team cohesion have often been studied separately, compelling theoretical logic suggests that the quality of leader-member relationships fundamentally shapes team cohesiveness through several interconnected mechanisms: generalized exchange, psychological safety, and social identity.

First, high-quality LMX relationships foster generalized exchange systems. When leaders invest trust and support in team members, they model reciprocity norms that extend beyond the specific dyad. Team members who experience high-quality exchanges internalize these behaviors and generalize them to their peers, creating a supportive environment where reciprocity becomes a collective norm (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). This diffusion strengthens social cohesion by enhancing interpersonal bonds and task cohesion by aligning individual efforts with collective goals.

Second, leader-member relationship quality serves as a primary antecedent of psychological safety. Leaders who establish authentic, supportive relationships signal that interpersonal risk-taking is safe and that unique contributions are valued (Edmondson, 1999). As this safety aggregates from individual dyads to the team level, it creates a climate where members feel secure enough to communicate openly, admit errors, and rely on one another. This collective psychological safety is essential for the mutual vulnerability and deep connection that characterize cohesive teams.

Third, LMX influences cohesion through resource distribution and social identity. In traditional differentiation models, scarce resources create competition between in-group and out-group members, fragmenting the team. However, when leaders adopt a “Leadership Making” approach—developing high-quality relationships with multiple members—they foster perceptions of equity and shared identity (Bauer & Erdogan, 2010). By engaging with diverse members, leaders bridge potential subgroups and emphasize a salient team identity. This reduces fragmentation and strengthens members’ emotional attachment to the collective (social cohesion) and their motivation to achieve shared objectives (task cohesion).

In summary, high-quality LMX relationships act as a catalyst, transforming individual dyadic interactions into emergent team properties by establishing norms of reciprocity, ensuring psychological safety, and reinforcing a unified team identity.

To synthesize the theoretical arguments presented above and clarify the specific relationships examined in this study, we propose a conceptual model. This model illustrates the hypothesized influence of Leader-Member Exchange quality on the three distinct dimensions of team cohesion: task cohesion, social cohesion, and individual attraction to the group, mediated through the mechanisms of reciprocity, trust, and psychological safety. The conceptual framework guiding this research is visually represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of LMX and Team Cohesion.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Context

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to investigate the relationship between leader-member exchange quality and team cohesion within an organizational context. The research was conducted in a major Croatian banking institution during the fourth quarter of 2023, capturing relationship dynamics and team processes during a period of relative organizational stability, thereby minimizing potential confounding effects from major restructuring or crisis events.

The banking sector provides an particularly appropriate empirical context for examining LMX-cohesion relationships for several reasons. First, banking operations inherently require substantial teamwork, with complex financial products and services necessitating coordination among specialists with diverse functional expertise (risk management, compliance, customer relations, operations). Second, the sector’s hierarchical organizational structures and formalized authority relationships create clear leader-member dyads amenable to LMX measurement. Third, contemporary banking faces significant environmental pressures—digital transformation, fintech competition, evolving regulations—making effective leadership and team functioning increasingly critical for organizational success. Finally, the professional services context resembles settings where much leadership research has been conducted, facilitating comparison with existing literature while extending geographic and cultural scope through the Croatian European setting.

The studied organization employed traditional team structures with designated team leaders holding formal supervisory authority over team members. Teams were relatively stable in composition, with most members having worked together for multiple years (mean team tenure = 6.5 years, SD = 5.2), allowing sufficient time for relationship development and cohesion formation. Teams varied in size and functional focus but shared similar organizational contexts, performance management systems, and cultural environments.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical framework outlined in Section 2, this study tested three primary hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Leader-member exchange quality is positively related to overall team cohesion. Specifically, teams characterized by higher-quality LMX relationships will demonstrate greater cohesiveness than teams with lower-quality LMX relationships.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Leader-member exchange quality is positively related to each dimension of team cohesion. Specifically:

- H2a: LMX quality is positively related to task cohesion

- H2b: LMX quality is positively related to individual attraction to group

- H2c: LMX quality is positively related to social cohesion

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The positive relationship between LMX quality and team cohesion (both overall and dimensional) will remain statistically significant when controlling for team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure.

These hypotheses derive from social exchange theory and the theoretical mechanisms linking dyadic leader-member relationships to collective team properties, as elaborated in Section 2.3.

3.3. Participants and Sampling

The study sample comprised 76 banking employees distributed across 10 distinct work teams within the organization. This included 10 team leaders (13.2% of the sample) occupying formal supervisory positions, and 66 team members (86.8%) reporting to these leaders. All participants were full-time permanent employees engaged in core banking operations rather than temporary, contract, or support staff, ensuring meaningful ongoing relationships amenable to LMX measurement.

The sample demographics reflected the banking workforce composition:

Gender distribution: 25 males (32.9%) and 51 females (67.1%), mirroring the gender composition typical of contemporary European banking sectors where female employees predominate in many operational and customer-facing roles.

Age distribution: The sample spanned five age categories: 20–30 years (n = 3, 3.9%), 31–40 years (n = 25, 32.9%), 41–50 years (n = 29, 38.2%), 51–60 years (n = 17, 22.4%), and 61–70 years (n = 2, 2.6%). The median age bracket of 41–50 years reflects a mature, experienced workforce with substantial organizational tenure.

Educational attainment: Participants reported secondary education (n = 17, 22.4%), higher vocational degrees (n = 10, 13.2%), and university degrees (n = 49, 64.5%). The predominance of university-educated employees (approximately 65%) aligns with banking sector requirements for analytical capabilities and professional expertise.

Organizational and team tenure: Organizational tenure ranged from 0 to 29 years (M = 10.2 years, SD = 8.7), while team tenure ranged from 0 to 26 years (M = 6.5 years, SD = 5.2). The substantial tenure indicates stable employment relationships providing ample opportunity for LMX development and cohesion formation, though also potentially introducing career stage effects warranting statistical control.

Teams varied considerably in size, ranging from 2 to 28 members (M = 7.6, SD = 8.0). This variation, while potentially introducing heterogeneity, reflects authentic organizational reality where different functional requirements necessitate different team configurations. The modal team size of 4–5 members aligns with research suggesting optimal sizes for relationship development and cohesion, though some larger teams reflected consolidated operational units. All teams possessed designated formal leaders with supervisory authority, ensuring comparable structural contexts for LMX relationship examination.

Sampling employed a census approach within participating teams rather than probabilistic sampling, inviting all members of identified work units to participate. This approach maximized response rates within teams, enabling more reliable team-level aggregation. The organization’s human resources department identified appropriate work teams meeting study criteria (stable membership, designated leader, minimum six-month existence) and facilitated access. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with no incentives provided beyond contributing to organizational understanding of leadership effectiveness.

The achieved response rate was approximately 92% of invited employees, reflecting strong engagement facilitated by organizational support and leadership endorsement. Non-response appeared randomly distributed across teams without systematic patterns suggesting response bias, though limited sample size precludes definitive non-response analysis.

3.4. Measurement Instruments

Leader-member exchange quality was assessed using the LMX-7 scale developed by Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995), the most widely-validated and extensively-utilized unidimensional LMX measure. The instrument comprises seven items capturing overall relationship quality through questions addressing mutual understanding, trust, support, obligation, and professional respect.

Responses were provided on five-point Likert scales with anchors varying by item but consistently ranging from minimal to maximal relationship quality (e.g., 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “completely,” or 1 = “extremely ineffective” to 5 = “extremely effective”). Individual item scores were summed to create total LMX scores ranging from 7 to 35, with higher scores indicating superior relationship quality.

Following established guidelines (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), we interpreted scores using the following thresholds: 7–14 (very low quality), 15–19 (low quality), 20–24 (moderate quality), 25–29 (high quality), and 30–35 (very high quality). These categories facilitate substantive interpretation while maintaining continuous measurement for statistical analyses.

The LMX-7 scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability in this sample, with Cronbach’s α = 0.873 for the complete sample, α = 0.857 for team members’ ratings of their relationships with leaders, and α = 0.889 for leaders’ ratings of relationships with members. These reliability coefficients exceed conventional thresholds (α ≥ 0.70) and align with reliability estimates reported across diverse cultural contexts, supporting measurement adequacy.

Team cohesion was measured using an adapted version of Carless and De Paola’s (2000) work team cohesion scale, which itself derives from the Group Environment Questionnaire originally developed for sports teams by Carron et al. (1985). The 10-item instrument assesses three conceptually-distinct cohesion dimensions:

Task Cohesion (4 items): Unity and shared commitment toward achieving team objectives. Example items: “Our team is united in trying to reach its goals for performance” and “Members of our team do not stick together outside of work time.”

Individual Attraction to Group (2 items): Personal satisfaction with team membership and desire to maintain affiliation. Example items: “This team is one of the most important social groups to which I belong” and “Some of my best friends are on this team.”

Social Cohesion (4 items): Quality of interpersonal relationships and social bonds among members. Example items: “Members of our team would like to spend time together in the off-season” and “Members of our team rarely party together.”

Items were rated on five-point Likert scales (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Six items (2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10) were reverse-scored such that higher values consistently indicated greater cohesion. Individual items were summed to create total cohesion scores (range: 10–50) and dimension subscale scores.

We interpreted total cohesion scores using the following thresholds: 10–15 (very low), 16–20 (low), 21–30 (moderate), 31–40 (high), and 41–50 (very high). These categories facilitate interpretation while maintaining continuous scoring for analyses.

Internal consistency reliability for the complete cohesion scale was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.678) when aggregated to team level, though lower than the LMX scale. This moderate reliability likely reflects the multidimensional nature of cohesion and the relatively small number of items per dimension. Importantly, reliability at the team level (aggregated mean responses) exceeded individual-level reliability (α = 0.342), supporting team-level aggregation as theoretically appropriate and empirically justified.

3.5. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected via online questionnaires administered through Google Forms, a secure, user-friendly platform enabling anonymous participation and automated data capture. Survey links were distributed by the organization’s human resources department via email to all eligible participants with leader endorsement emphasizing voluntary participation and confidentiality assurances.

The questionnaire comprised three sections: (1) demographic and contextual items (8 questions covering gender, age, education, role, team identification, team size, team tenure, organizational tenure); (2) LMX-7 items (7 questions); and (3) team cohesion items (10 questions). Both leaders and members completed identical LMX items, with leaders rating relationships with each team member and members rating relationships with their leader, enabling dyadic analysis. All participants completed cohesion items referencing their specific team.

Surveys remained open for three weeks during November-December 2023, with two email reminders sent at weekly intervals to non-respondents. No monetary or material incentives were provided, though participants received summary feedback about aggregate (de-identified) findings after analysis completion.

This research received approval from the University of Zagreb Faculty of Economics Ethics Committee (approval protocol PDS-20-2022). The study adhered to ethical principles including voluntary informed consent, confidentiality protection, anonymity, right to withdraw, and organizational permission. Participants received information sheets explaining research purposes, procedures, data handling, and contact information for questions or concerns. Consent was indicated through survey completion after reviewing information.

All data were anonymized immediately upon collection, with no personally-identifiable information collected or retained. Team identifications employed numeric codes without revealing functional areas or leaders’ names. Data were stored securely in password-protected files accessible only to the research team, and will be retained for five years per institutional policy before secure destruction.

3.6. Data Analysis Strategy

Data analysis proceeded through multiple stages encompassing preliminary data screening, psychometric evaluation, and hypothesis testing. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27.0, with data initially organized in Microsoft Excel before importation for analysis.

3.6.1. Preliminary Analyses and Data Screening

Prior to hypothesis testing, we conducted comprehensive preliminary analyses to assess data quality and measurement properties. Missing data patterns were examined to determine whether absent values appeared randomly distributed or systematically related to participant characteristics. Missing data proved minimal, affecting less than 2% of responses across all variables and appearing randomly distributed without systematic patterns. We employed listwise deletion for affected cases, a conservative approach justified by the minimal missing data prevalence and absence of systematic patterns suggesting informative missingness.

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, ranges, and frequency distributions were calculated for all variables to characterize the sample and identify potential data entry errors or implausible values. Visual inspection combined with statistical diagnostics confirmed data integrity without anomalies requiring correction. Distributional properties were assessed through histogram examination, Q-Q plots, and formal normality tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, Shapiro–Wilk) to determine whether distributions approximated normality sufficiently for parametric statistical procedures. While some variables exhibited mild departures from perfect normality, these deviations remained within acceptable limits for the robust parametric methods employed, particularly given the continuous nature of key variables and moderate sample size.

3.6.2. Psychometric Evaluation

Internal consistency reliability was assessed for multi-item scales using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, with α ≥ 0.70 considered acceptable per conventional psychometric standards (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Item-total correlations were examined to identify potentially problematic items demonstrating weak relationships with scale totals, though no items required elimination based on these diagnostics. The LMX-7 scale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.873 overall; α = 0.857 for members; α = 0.889 for leaders), while the cohesion scale showed adequate reliability at the team level (α = 0.678) despite lower individual-level reliability (α = 0.342), consistent with cohesion’s conceptualization as a collective property best assessed through aggregated perceptions.

3.6.3. Correlation Analysis

Bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients examined associations between LMX quality, overall team cohesion, cohesion dimensions (task cohesion, individual attraction to group, social cohesion), and control variables (team size, organizational tenure, team tenure). Correlation magnitudes were interpreted using Cohen’s (1988) conventional guidelines: |r| = 0.10–0.29 indicating small associations, 0.30–0.49 indicating medium associations, and ≥0.50 indicating large associations. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-tailed tests with α = 0.05 as the criterion, applying Bonferroni corrections when conducting multiple comparisons to control Type I error inflation. Correlation analysis served both descriptive purposes—characterizing bivariate relationships among study variables—and diagnostic purposes, identifying potential multicollinearity concerns and informing subsequent regression modeling.

3.6.4. Regression Analysis

Multiple regression models tested primary hypotheses regarding whether LMX quality significantly predicted cohesion outcomes while statistically controlling for potential confounding variables. We estimated separate regression models for overall team cohesion and each cohesion dimension (task cohesion, individual attraction to group, social cohesion) as dependent variables. In each model, LMX quality served as the focal independent variable, with team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure included as statistical controls to isolate LMX effects from potentially confounding structural and temporal factors.

Standardized regression coefficients (β) indicated the relative magnitude of each predictor’s unique contribution to explaining variance in the dependent variable, facilitating interpretation of effect sizes on a common metric. Coefficient of determination (R2) values quantified the proportion of variance in cohesion outcomes explained collectively by the predictor set, with adjusted R2 values accounting for the number of predictors relative to sample size. Statistical significance of individual regression coefficients was evaluated at α = 0.05, while overall model significance was assessed through F-tests.

Critical regression assumptions were verified through comprehensive residual diagnostics. Linearity between predictors and dependent variables was confirmed through scatterplot examination. Independence of observations was assumed based on sampling design, though we acknowledge potential modest dependency within teams addressed through supplementary analyses. Homoscedasticity (constant error variance across predicted values) was assessed through residual plots examining whether residual spread remained consistent across the range of fitted values. Normality of residuals was evaluated through Q-Q plots and formal tests. Multicollinearity among predictors was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF), with all VIF values well below the conventional threshold of 10, indicating multicollinearity did not pose concerns for coefficient estimation or interpretation.

3.6.5. Level of Analysis Considerations

Team cohesion conceptually represents a collective, team-level property reflecting shared perceptions and emergent group processes rather than merely aggregated individual attitudes1. Accordingly, primary analyses aggregated individual cohesion responses to team-level means (n = 10 teams). To justify aggregating individual responses to the team level, we calculated intraclass correlation coefficients and interrater agreement indices. The results ICC(1) = 0.11, ICC(2) = 0.47, mean rwg = 0.42) indicate sufficient between-group variance to justify aggregation, although the values for ICC(2) and rwg reflect the statistical constraints imposed by the small sizes of several functional teams in our sample. Given these metrics and the theoretical conceptualization of cohesion as a shared property, we proceeded with team-level analysis. Additionally, given the modest team-level sample size, we conducted supplementary individual-level analyses to verify the robustness of relationships.

3.7. Use of Artificial Intelligence

In preparing this manuscript, generative artificial intelligence tools (specifically, Claude AI by Anthropic) were utilized exclusively to assist with translating the original text from Croatian to English. The authors certify that all AI-generated outputs were rigorously reviewed, manually verified, and edited by the research team to ensure accuracy, conceptual integrity, and adherence to the original academic intent. AI was not used for data generation, analysis, or scientific interpretation.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

The final sample comprised 76 participants distributed across 10 work teams within the banking organization (Table 1). Demographic analysis revealed a predominantly female sample (67.1%, n = 51) with males constituting 32.9% (n = 25), reflecting typical gender distributions in contemporary European banking operations. The age distribution demonstrated a mature workforce, with the largest proportion in the 41–50 age bracket (38.2%, n = 29), followed by 31–40 years (32.9%, n = 25), 51–60 years (22.4%, n = 17), and minimal representation in the youngest (20–30 years: 3.9%, n = 3) and oldest brackets (61–70 years: 2.6%, n = 2). Educational attainment was high, with 64.5% holding university degrees (n = 49), 13.2% possessing higher vocational qualifications (n = 10), and 22.4% having completed secondary education (n = 17).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables.

Organizational tenure ranged from 0 to 29 years (M = 10.2, SD = 8.7), while team tenure spanned 0 to 26 years (M = 6.5, SD = 5.2), indicating substantial organizational experience and relationship development opportunities. Team sizes varied considerably from 2 to 28 members (M = 7.6, SD = 8.0), reflecting diverse functional requirements across organizational units.

Descriptive statistics revealed that LMX quality averaged 29.51 (SD = 4.82), falling within the “high quality” range (25–29) approaching “very high quality” (30–35). This suggests predominantly positive leader-member relationships characterized by mutual trust, respect, and support. The distribution showed negative skewness (−1.24), indicating clustering toward higher quality relationships with relatively few low-quality exchanges, consistent with organizational selection and socialization processes that promote relationship development.

Overall team cohesion averaged 38.90 (SD = 5.47), positioning within the “high cohesion” range (31–40). Among cohesion dimensions, task cohesion (M = 16.68, SD = 1.85) and social cohesion (M = 16.12, SD = 2.34) contributed most substantially to total cohesion, while individual attraction to group (M = 6.11, SD = 1.92) showed more modest levels, suggesting teams demonstrated greater unity around objectives and interpersonal bonds than purely individualized attachment.

4.2. Measurement Reliability

Internal consistency reliability coefficients confirmed the psychometric adequacy of study measures (see Table 2). The LMX-7 scale demonstrated excellent reliability both overall (α = 0.873) and when examined separately for team members’ ratings (α = 0.857) and leaders’ ratings (α = 0.889), substantially exceeding conventional thresholds and aligning with extensive prior validation research.

Table 2.

Internal Consistency Reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha).

The internal consistency for the overall team cohesion scale (α = 0.678) is marginally below the conventional 0.70 threshold. However, we consider this acceptable for the present study for several reasons. First, the construct of cohesion is inherently multidimensional, comprising distinct task and social facets, which naturally yields lower internal consistency than unidimensional measures. Second, the subscales consist of a relatively small number of items (3–4 items), which mathematically constrains Cronbach’s alpha values. Finally, given that our primary analysis relies on team-level aggregation, the stability of the aggregated group means is robust enough to support the regression analyses performed. Importantly, team-level reliability substantially exceeded individual-level reliability (α = 0.342), empirically supporting theoretical rationale for aggregating cohesion responses to the team level where the construct conceptually resides.

4.3. Inter-Correlations Among LMX Items

Before examining relationships between constructs, we assessed internal structure of the LMX measure through inter-item correlations (Table 3). All LMX items demonstrated statistically significant positive correlations (p < 0.01), ranging from moderate (r = 0.286 between items 5 and 7) to strong (r = 0.775 between items 3 and 7), confirming that items coherently measured a unified relationship quality construct. This pattern supports treating LMX as a unidimensional construct rather than requiring multidimensional disaggregation.

Table 3.

Inter-Item Correlations for LMX-7 Scale.

4.4. LMX Quality Across Teams

Examining LMX quality at the team level revealed substantial variation across units (Table 4). Six teams (Teams 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8) demonstrated very high average LMX quality (M ≥ 30), three teams (Teams 3, 6, 9) showed high quality (25 ≤ M < 30), and one team (Team 10) exhibited moderate quality (20 ≤ M < 25). This distribution indicates that most teams featured strong leader-member relationships, though notable variation existed, providing variance necessary for examining LMX-cohesion relationships.

Table 4.

LMX Quality and Team Cohesion by Team.

Visual inspection suggested correspondence between LMX and cohesion levels, with teams featuring higher LMX quality generally demonstrating greater cohesion. Notably, the single team exhibiting moderate LMX (Team 10) also showed moderate cohesion, while teams with very high LMX predominantly displayed very high or high cohesion. This pattern provided preliminary descriptive support for hypothesized LMX-cohesion relationships, subsequently tested through inferential statistics.

Regarding cohesion dimensions, task cohesion contributed 43.1% to total cohesion scores on average, social cohesion contributed 41.4%, and individual attraction contributed 15.5%. This distribution suggests that unity around goals and interpersonal relationship quality represented primary cohesion sources, while purely individualized team attachment played a more modest role.

4.5. Bivariate Correlations: LMX and Cohesion

Pearson correlation analyses examined bivariate associations between LMX quality, team cohesion (overall and dimensions), and control variables at the team level (Table 5). Results revealed a strong positive correlation between LMX and overall team cohesion (r = 0.854, p = 0.002), indicating that teams characterized by higher-quality leader-member relationships demonstrated substantially greater cohesiveness. This large-magnitude correlation provided strong initial support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 5.

Correlations Among Study Variables (Team Level, N = 10).

Examining cohesion dimensions separately, LMX demonstrated a strong positive correlation with social cohesion (r = 0.734, p = 0.016) and task cohesion (r = 0.681, p = 0.030), both achieving statistical significance. The correlation with individual attraction to group, while substantial (r = 0.585), did not reach conventional significance thresholds (p = 0.075), likely reflecting limited statistical power at the team level (n = 10) and potentially suggesting that LMX more strongly influences collective properties (task unity, interpersonal bonds) than purely individualized team attachment. These findings provided partial support for Hypothesis 2, with significant effects for two of three cohesion dimensions.

Control variables showed minimal associations with LMX or cohesion outcomes. Team size demonstrated negligible correlations with LMX (r = −0.035, p = 0.697) and cohesion (r = −0.136, p = 0.702). Organizational tenure showed modest negative correlations with LMX (r = −0.235, p = 0.071) approaching but not reaching significance, suggesting potential modest effects of career stage. Team tenure showed positive but non-significant correlations with LMX (r = 0.148, p = 0.258). Overall, control variables appeared relatively independent of focal constructs, reducing concerns about substantial confounding.

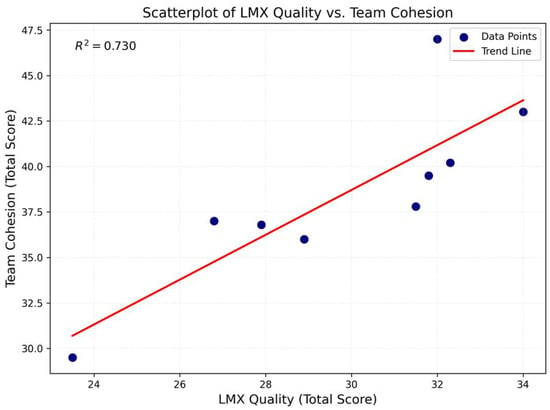

To further illustrate the robust relationship identified in our statistical analysis, Figure 2 presents a scatterplot of LMX Quality versus Team Cohesion for the ten studied teams. The inclusion of the regression line highlights the strong positive linear trend (R2 = 0.730), visually confirming that teams with higher-quality leader-member exchanges consistently demonstrate superior levels of overall cohesion

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of LMX Quality and Team Cohesion with Regression Trend Line.

4.6. Regression Analysis: LMX Predicting Team Cohesion

To test whether LMX significantly predicted team cohesion while controlling for potential confounds and to quantify effect magnitude, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression analysis (Table 6). Results demonstrated that LMX quality significantly and substantially predicted overall team cohesion.

Table 6.

Regression Analysis: LMX Predicting Overall Team Cohesion.

The unstandardized regression coefficient (B = 1.262, SE = 0.271) indicated that each one-unit increase in LMX quality predicted a 1.262-unit increase in team cohesion, holding other factors constant. The standardized coefficient (β = 0.854) confirmed a very strong effect size. This relationship achieved high statistical significance (t = 4.649, p = 0.002), and the model explained 72.9% of variance in team cohesion (R2 = 0.729, Adjusted R2 = 0.695).

Given the small team-level sample size (N = 10), we interpret this substantial effect size (R2 = 0.729) with necessary caution. We calculated 95% confidence intervals to assess the stability of the estimate. The interval for the LMX coefficient [0.64, 1.89] does not encompass zero, confirming the robustness of the positive relationship. The fact that the lower bound of the confidence interval is relatively high (0.64) suggests that the effect of LMX on cohesion is not only statistically significant but also practically potent, even in the most conservative estimation. However, the width of this interval suggests that while the direction of the effect is definitive, the precise magnitude of the impact may vary across broader populations, and the high explained variance should be understood within the context of this specific sample.

Model diagnostics confirmed that regression assumptions were adequately met. Residual plots showed no systematic patterns suggesting violations of linearity or homoscedasticity. Residuals approximated normal distribution based on Q-Q plot examination. The Durbin-Watson statistic (1.89) suggested minimal autocorrelation. Variance inflation factors remained low (VIF = 1.12), ruling out multicollinearity concerns.

We next examined whether LMX predicted specific cohesion dimensions, estimating separate regression models for task cohesion, individual attraction to group, and social cohesion as dependent variables (Table 7).

Table 7.

Regression Analyses: LMX Predicting Cohesion Dimensions.

LMX significantly predicted task cohesion (B = 0.392, β = 0.681, p = 0.030), explaining 46.3% of variance. For each unit increase in LMX, task cohesion increased by 0.392 units. This large effect indicated that high-quality leader-member relationships substantially enhanced collective commitment to team goals and coordinated task pursuit.

LMX also significantly predicted social cohesion (B = 0.496, β = 0.734, p = 0.016), explaining 53.9% of variance—the strongest dimensional effect. Each unit increase in LMX predicted a 0.496-unit increase in social cohesion. This suggested that quality leader-member relationships particularly enhanced interpersonal bonds, mutual support, and relationship quality among team members beyond task requirements.

The relationship between LMX and individual attraction to group, while positive and moderate in magnitude (B = 0.374, β = 0.585), approached but did not achieve conventional significance (p = 0.075), explaining 34.2% of variance. This marginal result may reflect statistical power limitations or potentially indicate that LMX influences collective properties more strongly than purely individualized team attachment, which may depend more heavily on personal factors beyond leadership relationships.

These findings provided partial support for Hypothesis 2, with LMX significantly predicting two of three cohesion dimensions (task and social cohesion) with large effect sizes, while showing suggestive but non-significant effects for individual attraction.

4.7. Control Variable Effects

To test Hypothesis 3 regarding whether LMX-cohesion relationships remained significant when controlling for structural and temporal factors, we estimated hierarchical regression models. Following recommendations for testing incremental variance (Cohen et al., 2003), we entered control variables (team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure) in the first step, followed by LMX quality in the second step. This sequential approach allows assessment of whether LMX explains variance in team cohesion beyond demographic and structural characteristics.

Prior to regression analysis, we examined multicollinearity diagnostics. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all predictors ranged from 1.00 to 1.82, well below the conservative threshold of 3.0 (Hair et al., 2010) and the commonly cited threshold of 10 (O’Brien, 2007), indicating no concerning multicollinearity among predictors.

To test Hypothesis 3 regarding whether LMX-cohesion relationships remained significant when controlling for structural and temporal factors, we estimated regression models including team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure as control variables alongside LMX (Table 8).

Table 8.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Predicting Team Cohesion (n = 10 teams).

Results demonstrated that LMX remained a strong and statistically significant predictor of team cohesion (B = 1.16, β = 0.787, p = 0.014) even when controlling for team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure. The addition of LMX in Model 2 substantially improved model fit, with ΔR2 = 0.730 (p < 0.01), indicating that LMX explains an additional 73.0% of variance in team cohesion beyond the control variables. The full model explained 83.8% of variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.708), with LMX contributing the vast majority of explained variance. The confidence interval for the LMX coefficient [0.43, 1.90] excludes zero, further confirming statistical significance. The Durbin-Watson statistic (2.53) falls within the acceptable range (1.5–2.5), indicating no problematic autocorrelation.

None of the control variables achieved statistical significance in the final model. Team size showed negligible effects (β = −0.053, p = 0.697). Organizational tenure demonstrated modest negative effects approaching but not exceeding statistical significance (β = −0.235, p = 0.071), potentially suggesting slight decreases in cohesion with longer organizational experience, though this effect remained tentative. Team tenure showed positive but non-significant effects (β = 0.148, p = 0.258).

These findings supported Hypothesis 3, confirming that LMX-cohesion relationships reflect genuine associations between relationship quality and team functioning rather than artifacts of team size, membership stability, or organizational experience. The robustness of LMX effects across model specifications strengthens confidence in substantive conclusions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Principal Findings

This study examined the relationship between leader-member exchange quality and team cohesion within banking sector teams, addressing a significant gap in organizational leadership research. Our investigation yielded three principal findings that collectively advance understanding of how relationship-based leadership influences team dynamics in complex organizational settings.

First, we found a strong positive correlation (r = 0.854, p = 0.002) between LMX quality and overall team cohesion, with high-quality leader-member relationships explaining approximately 73% of variance in team cohesiveness. This substantial effect persisted even when controlling for team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure, demonstrating robustness across model specifications. Second, dimensional analyses revealed that LMX significantly predicted both task cohesion (β = 0.681, p = 0.030) and social cohesion (β = 0.734, p = 0.016), with particularly strong effects on interpersonal relationship quality among team members. Third, the relationship between LMX and individual attraction to group, while positive and moderate (β = 0.585), approached but did not achieve conventional significance (p = 0.075), suggesting potential differential effects across cohesion facets.

These findings provide compelling empirical support for theoretical propositions linking relationship-based leadership to collective team properties, extending LMX theory beyond traditional dyadic frameworks while offering practical insights for leadership development in professional services contexts.

5.2. Theoretical Implications and Interpretation

Our findings make important theoretical contributions by demonstrating how dyadic leader-member relationships aggregate to influence collective team properties. While traditional LMX research has predominantly focused on individual-level outcomes1, our results suggest that when leaders develop high-quality relationships with multiple team members, these individual exchanges create positive spillover effects that fundamentally alter team-level dynamics. The magnitude of the observed effect, LMX explaining 73% of cohesion variance, indicates that relationship quality acts as a potent driver of team functioning, potentially outweighing structural or compositional antecedents.

The robust relationship between LMX and cohesion empirically supports the mechanism of generalized exchange outlined in our theoretical framework. Rather than remaining isolated within dyads, the trust and support demonstrated by leaders appear to establish team-wide reciprocity norms. When members observe these high-quality exchanges, they likely extend similar supportive behaviors horizontally to peers, strengthening the interpersonal bonds that constitute cohesion.

This dynamic is particularly evident in the strong prediction of social cohesion (β = 0.734). We interpret this finding through the lens of psychological safety: in a high-compliance banking environment, a leader who cultivates high-quality exchanges creates a ‘safe container’ that reduces interpersonal risk. This dynamic is likely amplified by the distinct Croatian cultural context described in the introduction. In such a setting, a leader who bridges the hierarchical gap through personal connection (LMX) signals that the rigid structure can be navigated safely, prompting members to rely more on each other for social support.

Regarding task cohesion, the significant relationship (β = 0.681) suggests that high-quality relationships facilitate the transition from individual motivation to collective commitment. By ensuring equitable access to information and resources, leaders likely foster shared mental models and reduce the competitive “hoarding” often seen in low-LMX environments. This confirms that relational leadership is instrumental not only for social climate but also for coordinating unified task pursuit.

Furthermore, our observation that teams with uniformly high LMX (e.g., Teams 1, 4, 5) exhibited the highest cohesion supports the “Leadership Making” model’s prescription to democratize relationship quality. Conversely, the lower cohesion in the team with moderate average LMX suggests that without a broad distribution of high-quality relationships, teams may suffer from fragmentation. Finally, the marginal effect of LMX on ‘individual attraction to group’ suggests a boundary condition: relationship-based leadership appears to drive emergent collective properties (shared norms, unity) more powerfully than idiosyncratic individual attachments, which may depend more on personal factors beyond the leader’s direct influence.

5.3. Comparison with Previous Research

Our findings align with and extend prior empirical research examining LMX-team outcome relationships. Boies and Howell (2006) reported that higher team-average LMX related to greater team efficacy and reduced intra-team conflict, though they examined efficacy rather than cohesion specifically. Our results complement their findings by demonstrating effects on cohesion while revealing larger effect magnitudes (r = 0.854 vs. their r ≈ 0.45), potentially reflecting methodological differences or contextual variation.

Banks et al. (2014) meta-analyzed team-member exchange (TMX) research, finding moderate positive relationships between TMX and team outcomes (ρ ≈ 0.35). While TMX focuses on peer rather than leader relationships, our findings suggest that LMX may similarly or perhaps more strongly predict team outcomes, with our observed correlations substantially exceeding typical TMX effect sizes. This raises intriguing questions about relative influence of vertical (leader-member) versus horizontal (peer-peer) relationships on team functioning, warranting direct comparative investigation.

Bauer and Erdogan (2010) found that justice climate moderated LMX differentiation effects on team outcomes, with differentiation proving less detrimental in high-justice climates. Our findings extend this perspective by suggesting that high average LMX itself may create justice perceptions and trust climate that buffer potential negative differentiation effects, though our design precluded formal moderation testing. Future research examining interplay among LMX level, differentiation, and justice climate would provide valuable theoretical integration.

Research by Gajendran and Joshi (2012) demonstrated that LMX positively predicted innovation in distributed teams through enhanced communication frequency and member influence on decisions. Our findings complement their work by showing strong LMX effects in co-located teams and extending outcome focus to cohesion. Together, these studies suggest that LMX benefits generalize across team configurations (co-located vs. distributed) and outcome domains (cohesion, innovation), reinforcing relationship quality as a fundamental driver of team effectiveness.

Our effect sizes substantially exceed those typically reported in leadership-outcome research, where meta-analytic correlations often fall in the 0.20–0.40 range (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). The observed r = 0.854 represents an exceptionally large effect, raising questions about potential inflation from common method variance, small sample size instability, or unique contextual factors. However, multiple considerations suggest genuine large effects rather than artifacts: (1) we aggregated individual responses to team level, which can amplify relationships by removing individual-level noise; (2) cohesion conceptually depends heavily on relational dynamics directly influenced by leadership; (3) the banking context features stable teams with extended relationship development time; and (4) results remained robust across analytical specifications.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the theoretical and practical contributions of this study, several important limitations warrant acknowledgment and careful consideration when interpreting our findings. The sample size at the team level (N = 10) is relatively small, which constrains statistical power and precludes the use of complex multilevel modeling techniques (e.g., HLM, structural equation modeling). While the confidence intervals calculated confirm the robust direction of the LMX-cohesion relationship, the wide intervals and large effect sizes (R2) observed should be interpreted with caution regarding their precise magnitude and stability across broader populations. The small number of teams also limits our ability to detect nuanced moderating effects or non-linear relationships. Future research utilizing larger, multi-organizational samples is necessary to validate these findings and allow for more rigorous multilevel inference.

While theoretical grounds support examining cohesion as a collective property, the empirical aggregation statistics (ICC(2) = 0.47, mean rwg = 0.42) were modest, largely reflecting the mathematical sensitivity of these indices to our small team sizes. Consequently, while meaningful between-team variance was detected (ICC(1) = 0.11), team-level inferences should be interpreted with appropriate caution regarding the strength of within-group agreement.

The cross-sectional research design captures relationships at a single point in time, preventing definitive causal inferences. While our theoretical model posits that LMX quality influences team cohesion development, reciprocal effects, where cohesive teams foster higher-quality leadership relationships or where third variables simultaneously influence both constructs, cannot be ruled out with our current design. The observed associations, while theoretically grounded and statistically robust, remain correlational rather than causal. We strongly recommend that future studies employ longitudinal or experimental designs to track how leadership interventions shape cohesion trajectories over time and establish temporal precedence.

The reliance on self-reported measures for both independent and dependent variables introduces the potential for common method variance, which may artificially inflate observed relationships. Although we employed validated scales, guaranteed anonymity to reduce social desirability, and found theoretically consistent patterns across cohesion dimensions (suggesting construct validity), same-source bias remains a concern. Furthermore, in hierarchical cultures with high power distance like Croatia, employees may exhibit a tendency towards socially desirable responding when rating supervisors, potentially inflating LMX scores due to deference to authority or fear of repercussions. Future studies would benefit from incorporating objective performance metrics, behavioral observations, or multisource data (e.g., evaluating cohesion through independent observation or peer ratings, measuring LMX from both leader and member perspectives) to triangulate findings and reduce method variance.

The study was conducted within a single banking institution in Croatia, which presents both strengths and limitations. While focusing on one organization controls for organizational culture, structure, and industry-specific factors—thereby reducing confounding variables—it simultaneously limits generalizability to other cultural, industrial, or organizational contexts. The Croatian banking sector’s unique characteristics, including post-transitional institutional context, high power distance cultural norms, regulatory environment, and hierarchical structures, may moderate the observed relationships in ways not captured by our analysis. Comparative studies examining these dynamics across different national cultures (particularly low power distance contexts), less hierarchical industries, or alternative organizational forms (e.g., flat structures, virtual teams) would provide valuable boundary conditions and enhance understanding of when and where relationship-based leadership most strongly influences team outcomes.

Despite these limitations, we believe our findings make meaningful contributions to LMX and team cohesion studies while identifying clear directions for future research to build upon and extend this initial investigation.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the relationship between leader-member exchange quality and team cohesion within banking sector teams, addressing a significant theoretical gap at the intersection of dyadic leadership relationships and collective team dynamics. Our findings provide compelling empirical evidence that high-quality leader-member relationships substantially predict team cohesiveness, with LMX explaining approximately 73% of variance in overall team cohesion. This robust association persisted when controlling for team size, organizational tenure, and team tenure, and manifested particularly strongly for task cohesion and social cohesion dimensions, though effects for individual attraction to group remained marginal.

These results make important theoretical contributions by extending LMX theory beyond its traditional dyadic focus to demonstrate how individual leader-member relationships aggregate to influence emergent collective properties. The magnitude of observed effects—substantially exceeding typical leadership-outcome relationships—suggests that relationship quality represents a particularly potent driver of team functioning, challenging perspectives that prioritize structural or compositional factors as primary cohesion determinants. Our findings support theoretical mechanisms wherein high-quality exchanges model reciprocity norms, create psychological safety and trust climates, facilitate equitable resource distribution, foster collective identity, and enhance communication infrastructure—processes that collectively strengthen the bonds, shared commitment, and unity characteristic of cohesive teams.

From a practical standpoint, findings underscore the strategic importance of relationship-based leadership for organizations navigating complex environments. For banking practitioners, these findings necessitate a shift from purely technical training to relational competency development. Given our finding that LMX most strongly predicts social cohesion (β = 0.734), training initiatives should prioritize the cultivation of emotional intelligence and trust-building capabilities, moving beyond a sole focus on technical task management. We recommend implementing structured mentorship programs where senior leaders actively model inclusive LMX behaviors. Furthermore, banks could introduce rotational leadership assignments within teams to disrupt static in-group/out-group dynamics and conduct ‘empathy audits’ to ensure leaders are fostering the psychological safety required for cohesion. Specifically, organizations should invest in developing leaders’ relational competencies—active listening, empathy, trust-building, individualized consideration, authentic engagement—alongside traditional technical and strategic capabilities. Leadership development should embrace the “leadership making” philosophy advocated by LMX theory, encouraging leaders to offer all team members opportunities for high-quality relationship development rather than concentrating exchanges among select favorites. This inclusive approach appears optimal for fostering the broadly distributed relationship quality that maximizes team-level cohesion while avoiding the differentiation effects that can fragment teams and undermine collective functioning.

Performance management and reward systems should recognize and incentivize relationship-building efforts and team development accomplishments, not exclusively individual performance outcomes. Leaders who successfully develop strong relationships enabling high team cohesion and effectiveness warrant recognition even when external constraints limit absolute performance levels. Organizations must create cultures and support systems—adequate time for relationship-building, coaching and mentoring resources, senior leadership modeling—that enable rather than obstruct relationship-focused leadership.

The contemporary shift toward virtual and hybrid work arrangements following the COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the importance of intentional relationship-building, as the incidental interactions and informal connections that naturally develop in co-located settings require deliberate cultivation in distributed contexts. Leaders managing virtual teams must leverage technology tools, establish relationship-focused rituals, and develop competencies specific to building trust and cohesion across distance. Our findings, though derived from co-located teams, reinforce that relationship quality fundamentally matters for team functioning regardless of physical configuration, suggesting that virtual contexts demand enhanced rather than reduced attention to relationship dynamics.

In VUCA environments—characterized by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity—that increasingly define contemporary business landscapes, team cohesion and the relationships fostering it provide invaluable organizational capabilities. Cohesive teams built on high-quality leader-member relationships demonstrate superior communication enabling rapid coordination during change, psychological safety facilitating experimentation and learning, collective resilience buffering stress and preventing burnout, and collaborative creativity driving innovation. These capabilities prove particularly critical when navigating digital transformation, competitive disruption, and strategic reorientation that banking and similar sectors currently face.

While our findings provide robust evidence for LMX-cohesion relationships within our specific context, several important limitations warrant acknowledgment. The cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inference, modest team-level sample size limits statistical power and generalizability, common method variance potentially inflates correlations, and single-organization Croatian banking context raises questions about cultural and organizational boundary conditions. Future research employing longitudinal designs, larger multi-organizational samples, objective outcome measures, cross-cultural comparisons, and examination of mediating mechanisms and moderating contingencies would address these limitations while extending theoretical understanding.

Despite these limitations, this study makes valuable contributions to both theory and practice. Theoretically, we extend LMX theory to collective levels of analysis, demonstrate substantial effects on team cohesion with magnitudes exceeding typical leadership research, and provide empirical support for theoretical mechanisms linking dyadic relationships to emergent team properties. Practically, we offer evidence-based guidance for leadership development, selection, and performance management while highlighting relationship quality as a strategic organizational capability particularly valuable in complex, dynamic environments.

As organizations increasingly rely on teams to accomplish complex, interdependent work requiring coordination across diverse expertise, and as leadership paradigms evolve from command-and-control toward collaborative, empowering approaches, understanding how micro-level relationships shape macro-level team dynamics becomes ever more critical. This research contributes to that understanding while identifying promising directions for continued inquiry into the relational foundations of effective teamwork in contemporary organizations.

The banking sector and similar professional services contexts face unprecedented challenges requiring organizational agility, innovation capacity, and workforce resilience. Leaders who invest in building authentic, supportive, high-quality relationships with their team members create not merely satisfied individuals but cohesive collectives capable of coordinating effectively, adapting rapidly, and performing excellently even amid turbulence and uncertainty. In an era where sustainable competitive advantage increasingly derives from human and social capital rather than purely technological or financial resources, the quality of relationships within organizations may prove among the most strategically consequential factors determining long-term success.

Our findings suggest that organizations neglecting relationship quality and treating leadership as primarily technical or strategic rather than fundamentally relational do so at considerable cost—fragmenting teams, undermining cohesion, and sacrificing the collective capabilities that high-quality relationships enable. Conversely, organizations that recognize, develop, reward, and institutionalize relationship-focused leadership position themselves to build the cohesive, high-performing teams essential for thriving in complex contemporary business landscapes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H. and M.B.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B., D.H. and A.S.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B.; resources, D.H.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, D.H. and A.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, D.H.; project administration, D.H.; funding acquisition, D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our study relied exclusively on voluntary and fully anonymous questionnaires. No identifying information, personal data, nor sensitive categories were collected, and no intervention or risk to participants was involved. Therefore, according to the ethical regulations of both the University of Zagreb and the Faculty of Economics & Business, University of Zagreb, formal Ethics Committee or IRB approval is not required for this type of minimal-risk, anonymous survey research. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, including informed consent, voluntary participation and protection of confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Banks, G. C., Batchelor, J. H., Seers, A., O’Boyle, E. H., Pollack, J. M., & Gower, K. (2014). What does team-member exchange bring to the party? A meta-analytic review of team and leader social exchange. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(2), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2010). Differentiated leader-member exchanges: The buffering role of justice climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1104–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennouna, A., Boughaba, A., Djabou, S., & Mouda, M. (2024). Enhancing workplace well-being: Unveiling the dynamics of leader-member exchange and worker safety behavior through psychological safety and job satisfaction. Safety and Health at Work, 15(4), 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Boies, K., & Howell, J. M. (2006). Leader-member exchange in teams: An examination of the interaction between relationship differentiation and mean LMX in explaining team-level outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(3), 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, K. C., & Brattström, A. (2024). Leader-member exchange differentiation and followers’ psychological strain: Exploring relations on the individual and on the team-level. Current Psychology, 43, 23115–23129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, S. A., & De Paola, C. (2000). The measurement of cohesion in work teams. Small Group Research, 31(1), 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey-Campbell, M., & Martens, M. L. (2009). Sticking it all together: A critical assessment of the group cohesion-performance literature. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(2), 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansereau, F., Graen, G., & Haga, W. J. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role-making process. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13(1), 46–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, N., Kundi, Y. M., & Umrani, W. A. (2024). Leader-member exchange and discretionary work behaviors: The mediating role of perceived psychological safety. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(4), 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1950). Informal social communication. Psychological Review, 57(5), 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajendran, R. S., & Joshi, A. (2012). Innovation in globally distributed teams: The role of LMX, communication frequency, and member influence on team decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, D. J., Liden, R. C., Glibkowski, B. C., & Chaudhry, A. (2009). LMX differentiation: A multilevel review and examination of its antecedents and outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(4), 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northouse, P. G. (2010). Leadership: Theory and practice (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E., Sims, D. E., & Burke, C. S. (2005). Is there a “Big Five” in teamwork? Small Group Research, 36(5), 555–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J., Zhang, Z., & Brett, J. (2024). How do leaders’ positive emotions improve employees’ psychological safety in China? The moderating effect of leader-member exchange. Heliyon, 10(3), e25481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.