Abstract

This study examines the impact of perceived overqualification (POQ) on employee negative megaphoning behaviours, focusing on the mediating roles of work-related stress and job embeddedness. A mixed-methods design was employed across two complementary studies. Study 1 analysed two-wave survey data from 431 hotel employees in China using structural equation modelling (SEM) in Mplus. Study 2 utilised a scenario-based experiment with 107 participants from the education sector to validate the proposed relationships. Results from both studies demonstrated a positive association between POQ and three forms of negative megaphoning—internal, external, and anonymous social media megaphoning. Work-related stress and job embeddedness emerged as significant mediating mechanisms explaining how misfit perceptions translate into negative communication behaviours. This research advances person–job fit theory by identifying POQ as a meaningful antecedent to negative megaphoning and by illuminating the psychological pathways through which misfit affects employee communication. Practically, the findings highlight the importance of reducing work-related stress and enhancing job embeddedness to help service organisations mitigate the reputational risks associated with POQ.

1. Introduction

In today’s globally interconnected environment, the phenomenon of megaphoning—where employees share information about their organisation both internally and externally—has become a pivotal factor in shaping an organisation’s public image and reputation (Kim & Rhee, 2011). This issue is particularly salient in industries where customer satisfaction and organisational reputation are paramount (Ahmed, 2023). Positive megaphoning can significantly enhance an organisation’s reputation by highlighting outstanding service and a positive workplace culture. However, negative megaphoning can undermine trust and loyalty among customers and stakeholders, posing a significant threat to the organisation’s standing (Y. Lee, 2022b). Given its dual potential to amplify supportive or harmful narratives, understanding the conditions that foster negative megaphoning has become a pressing scholarly and practical concern.

Negative megaphoning is a particularly formidable challenge in many industries. Employees who share unfavourable information can rapidly amplify their message across various channels, including internal audiences (e.g., colleagues) and external audiences (e.g., family, friends), as well as anonymous social media platforms (Krishna, 2023). The widespread dissemination of negative information can inflict substantial damage on an organisation’s reputation, making it a critical concern for service-oriented industries, such as hospitality (Kang et al., 2023). Given the hospitality sector’s reliance on customer trust and positive word-of-mouth, the ripple effects of negative publicity are particularly damaging, underscoring the necessity for organisations to address this issue proactively. Despite increased scholarly attention, research has predominantly focused on the consequences of negative megaphoning, with limited insight into its psychological and contextual antecedents (Bochoridou & Gkorezis, 2024).

Previous research has underscored the detrimental effects of negative megaphoning on both employees and organisations (Y. Lee, 2022b). Specifically, when employees engage in negative megaphoning, they can severely tarnish the organisation’s reputation (Mazzei et al., 2012; Men, 2014). According to Y. Lee (2022b), perceptions of organisational injustice intensify negative emotions, thereby increasing negative megaphoning behaviours on internal platforms, external forums, and anonymous websites. Moreover, perceived injustice erodes the quality of the employee–organisation relationship, further encouraging negative megaphoning. Although studies such as Y. Lee and Kim (2020) have begun identifying relational antecedents of negative megaphoning, the antecedent literature remains limited, with little attention to job-based factors such as perceived overqualification and almost no examination of the psychological mechanisms linking misfit to negative megaphoning (Kim & Rhee, 2011; Y. Lee, 2022b; Y. Lee & Kim, 2020). Addressing this gap is vital for identifying early signals of employee discontent before reputational damage occurs.

In response to these gaps in the literature, scholars have called for further exploration into the antecedents of negative megaphoning. This study draws on person–job fit theory (Edwards et al., 2006) and focuses on perceived overqualification (POQ). POQ refers to situations where an employee’s qualifications—such as education, skills, and experience—exceed the requirements of their job, leading to underutilization of their abilities (Erdogan & Bauer, 2009; Hu et al., 2024), which may, in turn, influence negative megaphoning behaviours. According to person–job fit theory (Edwards, 1996), individuals who are overqualified experience a mismatch between their qualifications and role expectations (Khan et al., 2024). This disparity may limit their ability to interact effectively with their work environment, as it restricts opportunities to apply their skills (Bochoridou & Gkorezis, 2024). As a result, overqualified individuals may feel unchallenged, underutilised, or undervalued, which can decrease their organisational commitment (Erdogan & Bauer, 2021). By focusing on POQ as a theoretically meaningful misfit condition, this study positions perceived overqualification as a novel antecedent of negative megaphoning.

This study specifically focuses on POQ as an antecedent of negative megaphoning for several theoretical reasons. First, POQ is commonly regarded as a form of underemployment and is viewed as an unfavourable employment situation that impedes person–job fit (e.g., Cheng et al., 2020; Howard et al., 2022). POQ creates a sense of being underappreciated in one’s role, which is linked to a range of negative outcomes for both individuals and organisations (Erdogan & Bauer, 2021). According to Gabriel and Aguinis (2022), employees who perceive themselves as a “misfit” within their work environment are more likely to engage in behaviours such as complaining and negative gossip (Bai et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2022). Overqualified employees are particularly prone to developing unfavourable attitudes toward their work, including stronger intentions to leave, lower job satisfaction, and weaker organisational commitment (B. Ma & Zhang, 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). Additionally, they are more likely to experience reduced wellbeing and exhibit counterproductive behaviours in the workplace (Andel et al., 2022). Although POQ has been widely associated with various negative outcomes, its potential role in shaping employees’ externalised behaviours—such as negative megaphoning—remains unexplored.

Given the unexplored nature of this inquiry, the study posits that the relationship between POQ and negative megaphoning behaviour may not be direct. Rather, there may be underlying mechanisms through which POQ influences these behaviours. Drawing on person–job fit theory, we examine how POQ affects negative megaphoning through work-related stress and job embeddedness. Work-related stress refers to the dysfunction an employee experiences due to negative conditions or events in the workplace (Hassard et al., 2018; Saleem et al., 2024). Stress arises when an individual’s expectations exceed job duties (Judge & Colquitt, 2004), often exacerbated by feelings of understimulation and underutilization, which are common among overqualified employees (Bochoridou & Gkorezis, 2024).

Furthermore, job embeddedness refers to the degree to which employees feel connected to their jobs, organisations, and communities (Ampofo et al., 2017). It reflects the extent to which employees perceive compatibility between their roles and themselves (William Lee et al., 2014). OQ represents a misalignment between an employee’s skills, experience, and job demands, which can erode their sense of connection to the organisation and diminish their job embeddedness (Arasli et al., 2017; Duan et al., 2022). This misfit between employee qualifications and job demands weakens job embeddedness, potentially increasing the likelihood of negative megaphoning behaviours.

This study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature in several key ways. First, it explicitly identifies POQ as a novel antecedent of negative megaphoning, thereby expanding early-stage understanding of how person–job misfit shapes reputationally negative communication behaviours (Andel et al., 2022) and negative megaphoning behaviour (Y. Lee, 2022b). Second, the study expands literature by examining how POQ affects employees’ work-related outcomes, such as behavioural and emotional responses (Bochoridou & Gkorezis, 2024; Cheng et al., 2020). Third, by identifying work-related stress as a crucial mechanism through which POQ leads to negative megaphoning, the study deepens our understanding of POQ, stress, and negative employee behaviour (Hoboubi et al., 2017). Finally, this research demonstrates how job embeddedness mediates the relationship between POQ and negative megaphoning, showing that a lack of job embeddedness increases the likelihood of negative megaphoning behaviours directed at the organisation. Collectively, these contributions provide a more integrative and theoretically grounded account of why and how overqualified employees may engage in negative megaphoning, addressing a critical gap flagged in recent organisational communication research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Person–Job Fit Theory

Person–job fit theory explains how the match between an individual’s abilities and job demands influences attitudes and behaviour. When employees experience alignment, they are more satisfied, engaged, and psychologically secure. However, misfits—such as perceived overqualification (POQ), where employees’ skills exceed job requirements—create frustration, diminished motivation, and emotional strain. In our model, POQ represents a form of misfit that prevents employees from utilising their capabilities, thereby generating work-related stress as employees feel underchallenged and undervalued. This strain, consistent with person–job fit assumptions, shapes behavioural and relational outcomes. As stress increases, employees’ job embeddedness weakens because the job no longer feels compatible or rewarding, reducing their attachment to organisational roles and relationships. This combination of reduced embeddedness and elevated stress creates conditions in which employees are more likely to engage in negative megaphoning, using internal, external, or anonymous channels to express dissatisfaction. Thus, person–job fit theory provides the foundational logic linking POQ to negative megaphoning through stress and embeddedness.

2.2. POQ as a Predictor of Employee Negative Megaphoning Behaviour

Employees with person–job misfit are more likely to engage in negative megaphoning when they experience a lack of stimulation, often due to underutilization of their education, skills, and abilities (e.g., Howard et al., 2022; B. Ma & Zhang, 2022). This sense of understimulation often leads to frustration and job dissatisfaction, driving overqualified employees to adopt negative behaviours, such as sharing unfavourable opinions or openly criticising the organisation’s methods and policies (Y. Lee & Kim, 2020).

Luksyte and Carpini (2024) further highlight that employees who consistently face a lack of challenge in their roles often perceive their work environment as frustrating, dissatisfying, and unfair. These perceptions can trigger a cycle of negative feedback about the organisation’s strategies, workflows, and operational practices. Overqualified employees, in particular, are prone to viewing their work situation as unjust, especially when they feel that their qualifications and potential are underappreciated or underutilised (e.g., Y. Lee, 2022a; Y. Lee & Kim, 2017). Such emotions can foster negative attitudes toward the organisation and encourage the dissemination of negative information, both internally among colleagues and externally to individuals outside the organisation (Debus et al., 2023).

The person–job fit theory (A. L. Kristof-Brown et al., 2005) posits that employees are most effective when their abilities align with the demands of their jobs. Conversely, when there is a mismatch between an employee’s qualifications and job responsibilities, negative emotions and behaviours are likely to emerge, undermining individual wellbeing and workplace performance (e.g., Z. Liu et al., 2024; Luksyte & Carpini, 2024). This theory also provides insight into the occurrence of negative megaphoning. When overqualified employees perceive a gap between their capabilities and the responsibilities of their role, they may resort to negative megaphoning—expressing their dissatisfaction both internally and externally, including on anonymous platforms—as a means to cope with their frustrations (Cheng et al., 2020). In this context, overqualified employees often vent their frustrations by spreading negative opinions about their organisation to their networks—family and friends—and to broader, anonymous audiences on platforms such as social media and review websites. This behaviour serves as an outlet for their dissatisfaction and a way to express their discontent with the organisation (Kang & Sung, 2017).

Hypothesis 1.

POQ is positively related to employees’ (1) internal, (2) external, and (3) social media negative megaphoning behaviours.

2.3. Work-Related Stress as a Mediator

Work-related stress arises when employees experience negative psychological reactions due to a mismatch between their capabilities—such as education, skills, and experience—and the demands of their job (Hassard et al., 2018). Stress can also emerge when there is a discrepancy between an individual’s expectations and the requirements of their role (Johnson et al., 2005). Luksyte and Carpini (2024) assert that overqualified individuals often experience frustration and boredom in their roles due to a perception of underutilization, leading to a lack of challenging tasks. In other words, overqualified employees may experience psychological distress when their skills and abilities are not fully utilised in their work. This sense of being undervalued can contribute significantly to work-related stress (e.g., Culbertson et al., 2011; Maynard et al., 2015).

Work-related stress is a psychological process wherein individuals perceive that the demands of their work environment are taxing their resources. When employees perceive their work conditions as overwhelming, they are more likely to share negative experiences and grievances about their organisation (e.g., Fisher et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2005). J. S. Lee et al. (2013) note that stress can amplify feelings of losing control among employees, serving as a significant psychosocial risk factor in the workplace. This heightened stress can, in turn, increase the likelihood of negative megaphoning behaviours (Tam & Kim, 2023). According to Y. Lee (2022b), overqualified employees frequently express their dissatisfaction by sharing negative information about their organisation, both internally with coworkers and externally to their personal networks. These employees often highlight organisational flaws, either directly to colleagues or anonymously on digital platforms, increasing their likelihood of engaging in negative megaphoning.

The person–job fit theory (A. L. Kristof-Brown et al., 2005) suggests that individuals perform better when their skills, abilities, and values align with the demands of their job. Overqualification can be conceptualised as a person–job misfit, where the mismatch between an individual’s qualifications and their job requirements leads to dissatisfaction and stress (Sylva et al., 2019). Van Dijk et al. (2020) emphasise that overqualified employees experience a gap between the opportunities their jobs offer and the expectations or requirements they place on their roles. When these employees encounter work-related stress, they tend to express negative opinions about their organisation on various platforms (e.g., Miceli et al., 2009; Ravazzani & Mazzei, 2018).

Hypothesis 2.

Work-related stress mediates the relationship between POQ and negative (1) internal, (2) external, and (3) social media negative megaphoning behaviours.

2.4. Job Embeddedness as a Mediator

Job embeddedness refers to the extent to which employees are involved with and committed to their jobs, organisations, and communities (William Lee et al., 2014). Marasi et al. (2016) define job embeddedness as the constellation of factors that help retain employees within an organisation. These factors may include links, fit, and sacrifice, which bind employees to their roles (e.g., Peltokorpi & Allen, 2024; Shah et al., 2020). When employees perceive that their job is not a good fit, they may become less committed to the organisation and even begin to share negative views about it (Y. Lee, 2022a). Overqualified employees, in particular, may feel a sense of misfit or detachment from their roles due to discrepancies between their qualifications and the job requirements (Khan et al., 2022). As overqualified employees become more aware of this misalignment, they may feel disconnected from their jobs and organisations, leading to decreased job embeddedness (Andel et al., 2022).

A lack of job embeddedness can signal an absence of psychological attachment to the workplace, which may trigger negative megaphoning behaviour (Mallol et al., 2007). Overqualified employees, who often experience a lack of challenge or opportunity to utilise their skills fully, may express their dissatisfaction through negative megaphoning. These behaviours can manifest as complaints shared with colleagues or public criticism on external platforms (C. Ma et al., 2023). The rise of anonymous websites and social media further provides overqualified employees with an avenue to share their grievances in an unfiltered, often public manner, while remaining anonymous (e.g., Elbaz et al., 2022; Y. Lee, 2022b).

In this context, we argue that overqualified individuals, who are experiencing lower levels of job embeddedness due to a misalignment between their qualifications and job demands, may be more inclined to engage in negative megaphoning. Their negative relationship with their job and organisation may drive them to express grievances both internally and externally, including on anonymous online platforms.

Hypothesis 3.

Job embeddedness mediates the relationship between POQ and (1) internal, (2) external, and (3) social media negative megaphoning behaviours.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study 1. Field Survey

3.1.1. Sample and Procedure

The study collected self-reported survey data, including participants’ responses to validated measures of perceived overqualification, work-related stress, job embeddedness, and negative megaphoning behaviours, along with demographic information. Data were collected between March and May 2025 using a time-lagged design across 41 hotels in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China. Hotels were selected to represent both internationally branded five-star properties and locally operated establishments. We contacted hotel HR departments and general managers via email and follow-up phone calls to request participation. Upon receiving organisational approval, HR managers supported the participant’s recruitment process and served as distribution coordinators. Surveys were administered in person during scheduled briefing sessions, ensuring controlled distribution. Hotel employees were chosen because the hospitality sector is highly sensitive to employee communication behaviours, particularly negative megaphoning. Hotels depend on customer perceptions, service quality, and word-of-mouth reputation, making them especially vulnerable to internal or external negative messaging. Furthermore, hotel roles commonly involve interactional demands and emotional labour, conditions that heighten experiences of person–job misfit, such as perceived overqualification.

The surveys were administered in two rounds, with a three-week interval between them. The interval helps to reduce common method bias, provides temporal separation between predictors and outcomes, and allows key psychological processes (e.g., stress responses and fluctuations in embeddedness) to unfold without increasing participant attrition. Participants were recruited from both international hotels and locally operated establishments, ensuring diversity in perspectives on perceived overqualification within the hospitality industry (Ali et al., 2022; Usman et al., 2021).

Initially, we reached out to 650 employees, each of whom received a cover letter outlining the study’s objectives and emphasising the confidentiality of their responses. In the first phase of data collection, we focused on POQ, work-related stress, and job embeddedness. The second round focused on collecting data on negative megaphoning behaviour. To ensure the same individuals completed both surveys, participants were instructed to generate a unique, anonymous matching code known only to them. This code allowed us to match responses across waves without collecting any identifiable information. Of the initial 650 participants, 473 completed the first round of surveys, and 451 participated in the second round. After cleaning the data and removing incomplete responses, we obtained a final sample size of 431 respondents, representing a response rate of 66.30%. Demographic information for the final sample indicated that 54.61% of participants were male, while 45.39% were female. The average age of the respondents was 34.15 years, and their average tenure with the organisation was 4.02 years.

We employed Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) in Mplus (version 8.6) to analyse the data. To mitigate the risk of common method bias, we adopted a time-lagged design (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Additionally, to further assess the potential for common method bias, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test. This test involved loading all variables onto a single factor to check for the extent of variance explained by a single underlying factor. The results indicated that the single factor accounted for 28.34% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold (Harman, 1976), suggesting that common method bias is unlikely to be a significant concern in this study.

3.1.2. Measures

In this study, all constructs were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Perceived Overqualification

Perceived overqualification was assessed using a nine-item scale developed by Maynard et al. (2006). A sample item from the scale is: “My job requires less education than I have.”

Work-Related Stress

Work-related stress was measured using a five-item scale adapted from Lambert et al. (2006). A sample item is: “There are many aspects of my job that make me upset.”

Job Embeddedness

Job embeddedness was assessed using the seven-item global on-the-job embeddedness scale developed by Crossley et al. (2007). A sample item is: “It would be difficult for me to leave this organisation.

Negative Megaphoning Behaviour

Negative megaphoning behaviours were evaluated using a fourteen-item scale based on the work of Kim and Rhee (2011). The scale was divided into three sub-categories: Five items were used to assess external negative megaphoning, such as: “I talk to people around me (e.g., family, friends) about negative things regarding my organisation.” Six items were employed to assess internal negative megaphoning, such as: “I discuss negative experiences within my organisation with my colleagues.” Three items were used to evaluate negative megaphoning on anonymous platforms, with a sample item being: “I post negative comments or reviews about my organisation/company on anonymous websites.”

Control Variables

In this study, we controlled for employees’ age, gender, education, and tenure. Previous research has shown that these factors may be related to negative megaphoning behaviour (Y. Lee, 2022a), job embeddedness (Peltokorpi & Allen, 2024), and work-related stress (Hoboubi et al., 2017).

4. Results

4.1. Means and Correlations

As shown in Table 1, the means and correlations support the proposed hypotheses, with all relationships significant and in the expected direction.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and reliabilities.

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model demonstrated strong psychometric properties. All factor loadings exceeded 0.6 and were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Composite reliability (CR) values for each variable surpassed the acceptable threshold of 0.6, and average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.5, indicating satisfactory internal consistency and convergent validity. Furthermore, the square root of each AVE was greater than the correlations between constructs, confirming the discriminant validity of the measures. The structural model was subsequently evaluated. The hypothesised baseline model was compared with alternative models through nested model comparisons to identify the best-fitting model. Given that POQ is theorised to affect employees’ negative megaphoning behaviours directly, the study incorporated direct paths from POQ to various forms of negative megaphoning behaviour in the alternative models. However, these alternative models did not significantly outperform the baseline model, which exhibited a high overall fit. The six-factor model, which included POQ, job embeddedness, work-related stress, and negative megaphoning behaviour (internal, external, and social media), provided the best fit. The model fit indices are presented in Table 2: χ2(1772.150) = 1144, χ2/df = 1.54, RMSEA = 054, SRMR = 0.047, CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.938.

Table 2.

Measurement model comparisons—Study 1.

4.3. Common Method Bias

As this study employed a cross-sectional design, it is essential to address potential standard-method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Initially, Harman’s single-factor test indicated that 26% of the total variance could be explained by a single component, falling short of the 50% threshold. This suggests that no single factor accounts for most of the observed variability across multiple variables. Furthermore, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted, which produced a one-factor model with indicators of poor fit: χ2 (1385) = 8432.236, CFI = 0.438, TLI = 0.610, RMSEA = 0.108, and SRMR = 0.178. We also tested the variance inflation factor (VIF) (Kock, 2015). The dataset was not expected to exhibit significant common method bias, as indicated by a maximum VIF of 2.89, which is below the model cutoff of 5.

4.4. Hypothesis Results—Study 1

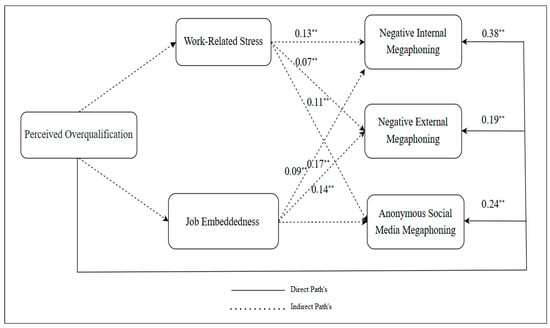

As presented in Table 3, we provide the results of Study 1, including both direct and indirect effects. The findings indicate a significant relationship between POQ and internal megaphoning (B = 0.38 **, SE = 0.05, CI = 0.28; 0.47). Similarly, POQ is positively related to external megaphoning (B = 0.19 **, SE = 0.06, CI = 0.07; 0.30) and anonymous social media megaphoning (B = 0.24 **, SE = 0.06, CI = 0.12; 0.35). In terms of indirect effects, POQ is positively related to internal megaphoning through work-related stress (B = 0.13 **, SE = 0.03, CI = 0.07; 0.18), external megaphoning (B = 0.07 **, SE = 0.03, CI = 0.01; 0.12), and anonymous social media megaphoning (B = 0.11 **, SE = 0.03, CI = 0.05; 0.16). Furthermore, POQ is positively related to negative internal megaphoning (B = 0.09 **, SE = 0.02, CI = 0.05; 0.12), external megaphoning (B = 0.17 **, SE = 0.03, CI = 0.11; 0.22), and social media megaphoning (B = 0.14 **, SE = 0.04, CI = 0.06; 0.21) via job embeddedness. Therefore, H1, H2, and H3 were accepted.

Table 3.

SEM results (Study 1 and Study 2).

4.5. Discussion—Study 1

The findings from Study 1 demonstrate a significant positive relationship between POQ and various forms of negative megaphoning—internal, external, and anonymous—among hospitality employees. Additionally, the results highlight the mediating role of work-related stress in the relationship between POQ and the different types of negative megaphoning. Similarly, job embeddedness was found to mediate the relationship between POQ and negative megaphoning behaviours. Drawing from the results, we argue that in the hospitality sector, where employee–customer interactions and organisational reputation are critical, overqualified employees often experience a misalignment between their skills and job demands, leading to increased frustration. This frustration can propel employees to engage in negative megaphoning, disseminating unfavourable information both internally within the organisation and externally to broader audiences. Given the importance of organisational reputation and employee wellbeing in the hospitality industry, it is crucial to address these dynamics. Reducing work-related stress and enhancing job embeddedness may help mitigate negative megaphoning behaviours, thereby protecting the organisation’s reputation and fostering greater employee satisfaction.

4.6. Study 2—Scenario-Based Experiment

4.6.1. Methods

To validate the findings of Study 1 and explore potential alternative explanations, a second study was conducted using a scenario-based experimental design (see Appendix A). The participants consisted of professional staff (N = 107; 42 women, 65 men) recruited from Universities across Guangdong Province, China. It is essential to acknowledge that non-academic university employees frequently encounter geographic constraints that may prompt them to accept positions for which they feel overqualified (McKee-Ryan & Harvey, 2011). As part of the recruitment process, contact information for all administrative employees at the selected universities was gathered through a comprehensive review of their respective websites.

4.6.2. Procedure

Before administering Study 2, the scenario was pretested and validated to ensure its clarity, realism, and effectiveness in depicting the intended conditions. The scenario underwent an initial evaluation by two academic experts in organisational behaviour, who reviewed it for conceptual accuracy and appropriateness for manipulating perceived qualification levels. Following expert review, the scenario was piloted with a small independent sample (n = 20) comparable to the target population. Participants assessed the scenario’s clarity, realism, and relevance using short evaluative items and provided open-ended feedback. Based on their responses, minor wording adjustments were made to enhance comprehension and strengthen the distinction between the overqualified and adequately qualified conditions. This pretesting process increases confidence that the scenario was understood as intended and provides a valid basis for examining participants’ responses. In addition, in the first phase of the experiment, participants were fully briefed about their rights and the voluntary nature of the study. They were explicitly informed that they could withdraw from the research at any point without consequence. After this, participants were asked to carefully read through hypothetical scenarios and imagine themselves in the position of the employee described in each.

4.6.3. Measures

In Study 2, we employed a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).” Participants were required to respond to all the questionnaire items, consistent with the procedure outlined in Study 1. All measures demonstrated acceptable reliability (α) based on the data collected in Study 2.

4.7. Results

4.7.1. Manipulation Check

Participants were randomly allocated to one of two conditions—overqualified or adequately qualified—using a between-subjects design. In the overqualified condition, participants were provided with a hypothetical scenario or information suggesting they were overqualified for their current job. In the adequately qualified condition, participants received information indicating they were adequately qualified for their job. After data collection, we analysed the results to examine whether participants in the overqualified condition demonstrated a higher propensity for negative megaphoning behaviour than those in the adequately qualified condition. Statistical analyses, including t-tests, were conducted to assess the significant differences between the two conditions.

The t-test results revealed that participants in the overqualified condition exhibited significantly higher levels of negative megaphoning behaviour across all types than those in the adequately qualified condition. Specifically, participants in the overqualified condition engaged in internal megaphoning (M = 4.00, SD = 0.88) significantly more than those in the adequately qualified condition (M = 2.30, SD = 0.85), with t(105) = 9.12, p < 0.001. Similarly, for external megaphoning, overqualified participants (M = 3.60, SD = 0.90) reported significantly higher levels of behaviour than those in the adequately qualified condition (M = 2.10, SD = 0.80), t(105) = 8.67, p < 0.001. Finally, for social media megaphoning, overqualified participants (M = 3.40, SD = 0.95) demonstrated more negative behaviour than the adequately qualified group (M = 2.00, SD = 0.85), with t(105) = 7.35, p < 0.001. These results confirm that participants in the overqualified condition were significantly more likely to engage in all forms of negative megaphoning behaviour compared to those in the adequately qualified condition.

4.7.2. Hypothesis Results—Study 2

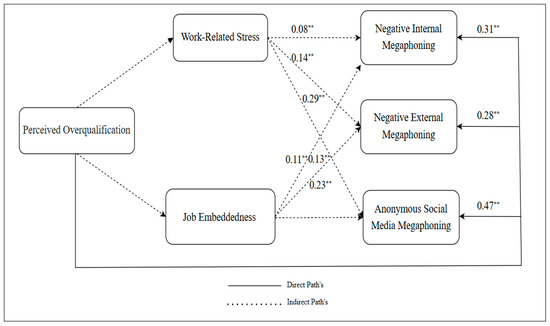

Table 1 presents the bivariate correlations between the main components of Study 2, and the results indicate that all correlations align with the expected directions. Table 3 outlines the direct and indirect effects for Study 2. The findings show a positive and significant relationship between POQ and internal megaphoning (B = 0.31 **, SE = 0.08, CI = 0.15; 0.47). Similarly, POQ is positively associated with both external megaphoning (B = 0.28 **, SE = 0.05, CI = 0.18; 0.38) and social media megaphoning (B = 0.47 **, SE = 0.06, CI = 0.35; 0.59). Regarding the indirect effects, POQ is positively related to negative internal megaphoning through work-related stress (B = 0.08 **, SE = 0.04, CI = 0.01; 0.16), external megaphoning (B = 0.14 **, SE = 0.07, CI = 0.01; 0.28), and social media megaphoning (B = 0.29 **, SE = 0.06, CI = 0.17; 0.41). Furthermore, POQ is positively related to negative internal megaphoning through job embeddedness (B = 0.11 **, SE = 0.05, CI = 0.01; 0.21), external megaphoning (B = 0.13 **, SE = 0.08, CI = 0.05; 0.21), and social media megaphoning (B = 0.23 **, SE = 0.09, CI = 0.05; 0.41). Therefore, these findings support the results from Study 1 and provide evidence for the acceptance of H1, H2, and H3.

5. General Discussion

Our study investigates the impact of POQ on various forms of negative megaphoning behaviour among employees in different sectors (hotels and universities). We conducted two studies: Study 1, which involved field surveys across multiple hotels, and Study 2, which focused on university professional staff through a scenario-based experiment. The results from both studies, as depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2, strongly support our hypotheses. The findings indicate that POQ triggers negative megaphoning because person–job misfit generates emotional strain and disrupts employees’ psychological attachment to the organisation. According to person–job fit theory, when employees feel their skills are underutilised, they experience cognitive dissonance and resource depletion, which manifests as frustration and reduced willingness to uphold the organisation’s positive image. This theoretical lens aligns with prior evidence showing that misfit encourages withdrawal and negative expression behaviours (Gabriel & Aguinis, 2022). Our results extend this understanding by demonstrating that misfit not only influences internal attitudes but also shapes outward communication behaviours.

Figure 1.

Research model showing direct and indirect effects of perceived overqualification on negative megaphoning via work-related stress and job embeddedness. Solid lines indicate direct paths; dotted lines indicate indirect paths. ** p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Results of the scenario-based experiment showing the direct and indirect effects of perceived overqualification on negative megaphoning, mediated by work-related stress and job embeddedness. Solid lines denote direct paths; dotted lines denote indirect paths. ** p < 0.01.

Moreover, our research highlights that work-related stress mediates the relationship between POQ and negative megaphoning behaviours. Specifically, overqualified individuals experience higher levels of stress, which increases the likelihood that they will share negative information. Kim and Rhee (2011) discussed the connection between job stress and negative workplace behaviours, emphasising that overqualified employees, who experience heightened stress, are more inclined to engage in negative communication. F. Liu et al. (2024) also stressed that stress facilitates the relationship between job-related factors and employee behaviour, playing a key role in amplifying dissatisfaction and resulting in negative expressions.

In addition, job embeddedness serves as a mediator between POQ and negative megaphoning behaviours, shedding light on the role of employees’ attachment and commitment to their organisations. When a mismatch occurs between an individual’s qualifications and job demands, their sense of job embeddedness may diminish (S. Liu et al., 2015). As employees feel overqualified, their connection to the organisation weakens, increasing their likelihood of engaging in negative megaphoning behaviours to express frustration and address the gap between their capabilities and the tasks they perform (Y. Lee, 2022b).

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes a significant contribution to the understanding of employee negative megaphoning behaviours due to person–job misfit. First, the findings reveal that POQ drives employees to engage in negative megaphoning behaviours both internally within the organisation and externally, including on anonymous online platforms. This suggests that negative megaphoning can be viewed as an emotional response (e.g., Y. Lee, 2022a; Y. Lee & Kim, 2020). The emotions of overqualified employees, particularly feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction, play a significant role in prompting them to share negative information about their organisation. This study provides one of the earliest empirical indications that POQ is a key driver of negative megaphoning behaviour (e.g., Khan et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2024). Our results suggest that the misalignment between employees’ qualifications and job demands, in line with person–job fit theory, can lead to dissatisfaction, which manifests in negative behaviours such as megaphoning. According to the person–job fit theory, when there is a mismatch between an individual’s abilities and the job’s requirements, it negatively affects job satisfaction and performance, which may trigger behaviours like megaphoning. Importantly, this strengthens theoretical understanding by positioning POQ not just as an attitudinal stressor, but as an antecedent that shapes employees’ external communication behaviour. This area has received limited attention in the megaphoning literature.

Second, work-related stress has long been studied in organisational behaviour literature and is linked to various negative outcomes (e.g., Deniz et al., 2015; Hassard et al., 2018). This study advances the literature on work-related stress by shedding light on the role of perceived overqualification in shaping negative megaphoning behaviours. Specifically, it demonstrates how overqualified employees may experience heightened work-related stress, leading them to express frustration and negative opinions about the organisation. This research deepens our understanding of how perceived overqualification influences employee behaviour and offers valuable insights into workplace communication dynamics. Building on Gilboa et al. (2008), who emphasised the role of stress in mediating the relationship between job stressors and behavioural outcomes, this study confirms that work-related stress is an important mediator of the relationship between POQ and negative workplace behaviours. Consistent with the person–job fit theory (A. Kristof-Brown & Guay, 2011), our findings suggest that POQ increases work-related stress due to person–job misfit. This stress, in turn, motivates employees to engage in negative megaphoning behaviours. Additionally, this study contributes to the literature on overqualified employees by examining how these individuals communicate negative aspects of their organisations across various platforms. Their primary motivation is the need to vent their work-related stress. Employees who experience a mismatch between their qualifications and job demands are more likely to experience stress, which drives them to share negative information about their organisations. Consistent with the person–job fit theory (A. Kristof-Brown & Guay, 2011), our findings suggest that POQ increases work-related stress due to person–job misfit. This stress, in turn, motivates employees to engage in negative megaphoning behaviours. Theoretically, this extends stress research by showing that stress-driven reactions may now include reputationally damaging behaviours that extend beyond internal organisational boundaries.

Third, this study provides a novel perspective on the role of job embeddedness as a mechanism linking POQ to negative megaphoning behaviours. Our findings extend the literature by suggesting that when there is person–job misfit, employees’ job attachment decreases. This reduction in job immersion or attachment leads to the emergence of negative megaphoning behaviours. Overqualified employees who perceive a mismatch between their qualifications and job demands become less connected to their organisation, thereby weakening their job embeddedness. With lower levels of job embeddedness, these employees are more likely to engage in negative megaphoning behaviours, including criticism of the organisation and management, both internally and externally (including on social media platforms). This study emphasises the critical role of job embeddedness in understanding how perceived overqualification shapes employees’ workplace behaviour. This study therefore contributes theoretically by identifying job embeddedness as a behavioural link between misfit and outward-facing communication, expanding embeddedness theory into the domain of employee voice and megaphoning.

5.2. Practical Implications

Organisations must ensure that employees’ talents are effectively utilised and recognised. Failing to address overqualification can lead to disengagement, increased stress, and weakened job attachment. Employers should create an environment where employees feel valued and engaged in meaningful work that matches their skills. The study highlights that a good person–job fit prevents negative megaphoning behaviours. Employees who feel underutilised are more likely to engage in negative communication, both internally and externally, including on social media. Organisations can reduce this by fostering feedback channels and addressing person–job misfit. Overqualified employees should be encouraged to discuss job mismatches with supervisors. This allows them to utilise their skills better and reduce frustration. Organisations can also alleviate stress by providing clear and honest job descriptions. Transparency helps employees align their expectations with the role, boosting trust and attachment and reducing stress. Furthermore, employee assistance programmes can support overqualified employees in managing stress and improving job satisfaction. These programmes, along with activities such as mentoring and participatory decision-making, can help employees feel more connected and reduce negative megaphone behaviours.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

A key limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which precludes establishing causal relationships between variables. To strengthen causal inference, future research should employ longitudinal or experimental designs that can capture temporal changes in POQ, work-related stress, job embeddedness, and megaphoning behaviours. Future research could address this by using longitudinal designs to examine the temporal dynamics among POQ, work-related stress, job embeddedness, and negative megaphoning behaviours. This would provide a clearer understanding of how these factors interact over time and help uncover causal pathways. Additionally, this study focused on the mediating roles of work-related stress and job embeddedness. Future research could explore the psychological and emotional factors that contribute to the relationship between POQ negativity and megaphoning. Feelings of uncertainty, psychological detachment, and strain could offer further insight into how mental health affects employees’ responses to POQ and related stressors. Future studies should also consider potential moderators, such as organisational factors (e.g., leadership styles, organisational culture, and job design) that may influence the relationship between POQ-negative megaphoning and the outcome. Examining individual differences—such as personality traits, coping mechanisms, and emotional intelligence—could help explain why some employees are more prone to engage in negative megaphoning behaviours in response to overqualification and work-related stress. In addition, future studies may incorporate multi-source or time-lagged data to reduce common method bias and improve methodological robustness. Including behavioural or digital trace measures of megaphoning (e.g., online postings, external reviews) may also provide a richer and more objective assessment of the phenomenon.

6. Conclusions

This study, guided by person–job fit theory, reveals that a misalignment between employees’ qualifications and job demands acts as a stressor, increasing work-related stress and reducing job embeddedness. These factors, in turn, are linked to a higher tendency towards negative megaphoning behaviours among overqualified employees in the hospitality and education sectors. Both the field survey and scenario-based experiment consistently demonstrate that POQ plays a crucial role in shaping employees’ negative workplace experiences and behaviours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.A., A.V.-M., N.C.-B., J.K., M.Z. and K.A.; Software, H.S.A.; Validation, M.Z.; Formal analysis, A.V.-M. and J.K.; Resources, N.C.-B. and J.K.; Data curation, A.V.-M.; Writing—original draft, H.S.A., A.V.-M., N.C.-B., J.K., M.Z. and K.A.; Writing—review & editing, H.S.A., A.V.-M., J.K., M.Z. and K.A.; Visualization, K.A.; Supervision, N.C.-B.; Project administration, H.S.A. and N.C.-B.; Funding acquisition, A.V.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ARUCAD Research Centre, Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design, Northern Cyprus, Turkey (ARUCAD-00432024-04, 4 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to restrictions, the data are not publicly available; however, they can be made available upon a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The Research would like to acknowledge Deanship of Scientific Research, Taif University for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Scenario 1: Overqualified Condition

“You are a highly qualified professional who has recently joined a new organisation. Despite your qualifications and expertise, your role mainly involves routine tasks that do not fully utilise your skills. You notice that many of your colleagues, who are less experienced than you, hold more responsible positions within the organisation. You often feel undervalued, believing you could contribute more effectively in a more challenging role. This sense of being overqualified for your current position leads to growing dissatisfaction and disengagement at work. As a result, you begin to experience symptoms of work-related stress, such as increased tension, irritability, and difficulty concentrating. You also start questioning your attachment and commitment to the organisation. You feel disconnected from your job and perceive a clear mismatch between yourself and your role. Due to this stress and reduced job embeddedness, you begin to display negative workplace behaviours, becoming increasingly critical of colleagues and supervisors, openly expressing dissatisfaction, and engaging in negative megaphoning.”

- Scenario 2: Adequately Qualified Condition

“You are a professional who has recently joined a new organisation. Your qualifications and experience closely match the requirements of your current role. The tasks assigned to you make good use of your knowledge and skills, and you feel that your responsibilities are appropriate for your level. You observe that your colleagues hold similar roles and levels of responsibility, and you feel fairly positioned within the organisation. Because your abilities align well with your job, you generally feel satisfied, valued, and comfortable in your role. You do not experience notable work-related stress beyond normal daily pressures, and you find it easy to focus on your tasks. You also feel connected to your job and maintain a sense of attachment and commitment to the organisation. As a result, you do not display negative workplace behaviours and do not feel inclined to criticise colleagues or supervisors or engage in negative megaphoning.”

| Appendix-Scale Items |

| Perceived Overqualification |

| My job requires less education than I have. |

| The work experience that I have is not necessary to be successful on this job. |

| I have job skills that are not required for this job. |

| Someone with less education than myself could perform well on my job. |

| My previous training is not being fully utilized on this job. |

| I have a lot of knowledge that I do not need in order to do my job. |

| My education level is above the education level required by my job. |

| Someone with less work experience than myself could do my job just as well. |

| I have more abilities than I need in order to do my job. |

| Work-Related Stress |

| A lot of the time, my job makes me very frustrated or angry. |

| I am usually under a lot of pressure when I am at work. |

| When I’m at work, I often feel tense or uptight. |

| I am usually calm and at ease when I’m working. |

| There are a lot of aspects of my job that make me upset. |

| Job Embeddedness |

| I feel attached to this organisation. |

| It would be difficult for me to leave this organisation. |

| I’m too caught up in this organisation to leave. |

| I feel tied to this organisation. |

| I simply could not leave the organisation I work for. |

| (R) It would be not easy for me to leave this organisation. |

| I am tightly connected to this organisation. |

| Internal Negative Megaphoning |

| (How often do you…) |

| Talk with your colleagues about the weaknesses of your organisation and its management? |

| Talk with your colleagues about negative aspects of your organisation? |

| Talk with your colleagues about the bad features of your organisation’s products and services? |

| Discuss negative experiences within your organisation with colleagues? |

| Criticise your organisation and its management with colleagues? |

| Complain to colleagues about frustrating or dissatisfying organisational policies, procedures, or practices? |

| External Negative Megaphoning |

| (How often do you…) |

| Talk to people around you (e.g., family, friends) about bad things regarding your organisation? |

| Agree with people who mention negative aspects of your organisation or department? |

| Actively criticise your organisation and management when speaking to people close to you? |

| Agree and reinforce negative opinions when hearing biased or uninformed criticism about your organisation? |

| Talk to neighbours and friends about how your organisation performs worse than other organisations? |

| Anonymous Social Media Megaphoning |

| (How often do you…) |

| Write negative comments or reviews about your organisation on anonymous websites (e.g., Glassdoor)? |

| Criticise your organisation and its management on anonymous websites (e.g., Glassdoor)? |

| Share posts or content about organisational problems on anonymous websites (e.g., Glassdoor)? |

References

- Ahmed, I. (2023). Fun at work and employees’ communication behavior: A serial mediation mechanism. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74, 1866–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Usman, M., Soetan, G. T., Saeed, M., & Rofcanin, Y. (2022). Spiritual leadership and work alienation: Analysis of mechanisms and constraints. The Service Industries Journal, 42(11–12), 897–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, E. T., Coetzer, A., & Poisat, P. (2017). Relationships between job embeddedness and employees’ life satisfaction. Employee Relations, 39(7), 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, S., Pindek, S., & Arvan, M. L. (2022). Bored, angry, and overqualified? The high-and low-intensity pathways linking perceived overqualification to behavioural outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(1), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H., Bahman Teimouri, R., Kiliç, H., & Aghaei, I. (2017). Effects of service orientation on job embeddedness in hotel industry. The Service Industries Journal, 37(9–10), 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Wang, J., Chen, T., & Li, F. (2020). Learning from supervisor negative gossip: The reflective learning process and performance outcome of employee receivers. Human Relations, 73(12), 1689–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochoridou, A., & Gkorezis, P. (2024). Perceived overqualification, work-related boredom, and intention to leave: Examining the moderating role of high-performance work systems. Personnel Review, 53(5), 1311–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Zhou, X., Guo, G., & Yang, K. (2020). Perceived overqualification and cyberloafing: A moderated-mediation model based on equity theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 164, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, S. S., Mills, M. J., & Huffman, A. H. (2011). Implications of overqualification for work–family conflict: Bringing too much to the table? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4(2), 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debus, M. E., Körner, B., Wang, M., & Kleinmann, M. (2023). Reacting to perceived overqualification: Uniting strain-based and self-regulatory adjustment reactions and the moderating role of formal work arrangements. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(2), 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, N., Noyan, A., & Ertosun, Ö. G. (2015). Linking person-job fit to job stress: The mediating effect of perceived person-organization fit. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J., Xia, Y., Xu, Y., & Wu, C. H. (2022). The curvilinear effect of perceived overqualification on constructive voice: The moderating role of leader consultation and the mediating role of work engagement. Human Resource Management, 61(4), 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R. (1996). An examination of competing versions of the person-environment fit approach to stress. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 292–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., Cable, D. M., Williamson, I. O., Lambert, L. S., & Shipp, A. J. (2006). The phenomenology of fit: Linking the person and environment to the subjective experience of person-environment fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A. M., Salem, I. E., Onjewu, A.-K., & Shaaban, M. N. (2022). Hearing employee voice and handling grievance: Views from frontline hotel and travel agency employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 107, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2009). Perceived overqualification and its outcomes: The moderating role of empowerment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2021). Overqualification at work: A review and synthesis of the literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S., Gillanders, D., & Ferreira, N. (2022). The experiences of palliative care professionals and their responses to work-related stress: A qualitative study. British Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, K. P., & Aguinis, H. (2022). How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Business Horizons, 65(2), 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61(2), 227–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press. [Google Scholar]

- Hassard, J., Teoh, K. R., Visockaite, G., Dewe, P., & Cox, T. (2018). The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoboubi, N., Choobineh, A., Ghanavati, F. K., Keshavarzi, S., & Hosseini, A. A. (2017). The impact of job stress and job satisfaction on workforce productivity in an Iranian petrochemical industry. Safety and Health at Work, 8(1), 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E., Luksyte, A., Amarnani, R. K., & Spitzmueller, C. (2022). Perceived overqualification and experiences of incivility: Can task i-deals help or hurt? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Zhu, Y., Ma, E., & Chen, C. (2024). How do you treat your ‘big fish’? The joint effect of perceived subordinates’ overqualification and managers’ personalities on knowledge hiding. The Service Industries Journal, 45, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P., & Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Colquitt, J. A. (2004). Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role of work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., Lee, E., Kim, Y., & Yang, S.-U. (2023). A test of a dual model of positive and negative EORs: Dialogic employee communication perceptions related to employee-organization relationships and employee megaphoning intentions. Journal of Public Relations Research, 35(3), 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., & Sung, M. (2017). How symmetrical employee communication leads to employee engagement and positive employee communication behaviors: The mediation of employee-organization relationships. Journal of Communication Management, 21(1), 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J., Ali, A., Saeed, I., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Contreras-Barraza, N. (2022). Person–job misfit: Perceived overqualification and counterproductive work behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 936900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, J., Zhang, Q., & Salameh, A. A. (2024). Look busy do nothing: Does professional isolation and psychological strain of overqualified employee leads to goldbricking behaviour? Career Development International, 29(7), 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-N., & Rhee, Y. (2011). Strategic thinking about employee communication behavior (ECB) in public relations: Testing the models of megaphoning and scouting effects in Korea. Journal of Public Relations Research, 23(3), 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJEC), 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. (2023). Relationships and identity fusion: Understanding antecedents of employees’ megaphoning behaviours in response to corporate misconduct-related crises. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 31(3), 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A., & Guay, R. P. (2011). Person–environment fit. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 3. Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (pp. 3–50). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Camp, S. D., & Ventura, L. A. (2006). The impact of work–family conflict on correctional staff: A preliminary study. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 6(4), 371–387. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. S., Joo, E. J., & Choi, K. S. (2013). Perceived stress and self-esteem mediate the effects of work-related stress on depression. Stress and Health, 29(1), 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. (2022a). An examination of the effects of employee words in organizational crisis: Public forgiveness and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Business Communication, 59(4), 598–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. (2022b). Employees’ negative megaphoning in response to organizational injustice: The mediating role of employee–organization relationship and negative affect. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(1), 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., & Kim, J.-N. (2017). Authentic enterprise, organization-employee relationship, and employee-generated managerial assets. Journal of Communication Management, 21(3), 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., & Kim, K. H. (2020). De-motivating employees’ negative communication behaviors on anonymous social media: The role of public relations. Public Relations Review, 46(4), 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Li, J., Lan, J., & Gong, Y. (2024). Linking perceived overqualification to work withdrawal, employee silence, and pro-job unethical behavior in a Chinese context: The mediating roles of shame and anger. Review of Managerial Science, 18(3), 711–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Luksyte, A., Zhou, L., Shi, J., & Wang, M. (2015). Overqualification and counterproductive work behaviors: Examining a moderated mediation model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Huang, Y., Kim, T. Y., & Yang, J. (2024). Perceived overqualification and employee outcomes: The dual pathways and the moderating effects of dual-focused transformational leadership. Human Resource Management, 63, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luksyte, A., & Carpini, J. A. (2024). Perceived overqualification and subjective career success: Is harmonious or obsessive passion beneficial? Applied Psychology, 73, 2077–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., & Zhang, J. (2022). Are overqualified individuals hiding knowledge: The mediating role of negative emotion state. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(3), 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Shang, S., Zhao, H., Zhong, J., & Chan, X. W. (2023). Speaking for organization or self? Investigating the effects of perceived overqualification on pro-organizational and self-interested voice. Journal of Business Research, 168, 114215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallol, C. M., Holtom, B. C., & Lee, T. W. (2007). Job embeddedness in a culturally diverse environment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasi, S., Cox, S. S., & Bennett, R. J. (2016). Job embeddedness: Is it always a good thing? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D. C., Brondolo, E. M., Connelly, C. E., & Sauer, C. E. (2015). I’m too good for this job: Narcissism’s role in the experience of overqualification. Applied Psychology, 64(1), 208–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D. C., Joseph, T. A., & Maynard, A. M. (2006). Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, A., Kim, J.-N., & Dell’Oro, C. (2012). Strategic value of employee relationships and communicative actions: Overcoming corporate crisis with quality internal communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 6(1), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee-Ryan, F. M., & Harvey, J. (2011). “I have a job, but…”: A review of underemployment. Journal of Management, 37(4), 962–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L. R. (2014). Why leadership matters to internal communication: Linking transformational leadership, symmetrical communication, and employee outcomes. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(3), 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, M. P., Near, J. P., & Dworkin, T. M. (2009). A word to the wise: How managers and policy-makers can encourage employees to report wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V., & Allen, D. G. (2024). Job embeddedness and voluntary turnover in the face of job insecurity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(3), 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravazzani, S., & Mazzei, A. (2018). Employee anonymous online dissent: Dynamics and ethical challenges for employees, targeted organisations, online outlets, and audiences. Business Ethics Quarterly, 28(2), 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S., Sajid, M., Arshad, M., Raziq, M. M., & Shaheen, S. (2024). Work stress, ego depletion, gender and abusive supervision: A self-Regulatory perspective. The Service Industries Journal, 44(5–6), 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I. A., Csordas, T., Akram, U., Yadav, A., & Rasool, H. (2020). Multifaceted role of job embeddedness within organizations: Development of sustainable approach to reducing turnover intention. Sage Open, 10(2), 2158244020934876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylva, H., Mol, S. T., Den Hartog, D. N., & Dorenbosch, L. (2019). Person-job fit and proactive career behaviour: A dynamic approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(5), 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, L., & Kim, S. (2023). Understanding conspiratorial thinking (CT) within public relations research: Dynamics of organization-public relationship quality, CT, and negative megaphoning. Public Relations Review, 49(4), 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M., Javed, U., Shoukat, A., & Bashir, N. A. (2021). Does meaningful work reduce cyberloafing? Important roles of affective commitment and leader-member exchange. Behaviour & Information Technology, 40(2), 206–220. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, H., Shantz, A., & Alfes, K. (2020). Welcome to the bright side: Why, how, and when overqualification enhances performance. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Lee, T., Burch, T. C., & Mitchell, T. R. (2014). The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Xia, B., Derks, D., Pletzer, J. L., Breevaart, K., & Zhang, X. (2024). Perceived overqualification, counterproductive work behaviors and withdrawal: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 39, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R., Tang, P. M., & Lee, S. H. (2022). The Gossiper’s high and low: Investigating the impact of negative gossip about the supervisor on work engagement. Personnel Psychology, 77, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.