Abstract

This study aims to analyze how women’s empowerment in sustainable entrepreneurial leadership transforms social, environmental, and economic challenges into growth opportunities within B Corps-certified companies in Latin America. A total of 9536 companies were identified in the global B Corps registry, of which more than 1000 belonged to the Latin America and Caribbean directory. Particular attention was given to 130 companies located in Chile, with a presence in countries such as Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina. The methodology adopted a post-positivist approach with a hermeneutic analysis rooted in organizational studies, using the Straussian grounded theory method. Testimonies from 16 female entrepreneurs were explored, identified through the B Corps directory and the main social media networks of the B system in Latin America. This approach enabled a deeper understanding of the human complexity surrounding sustainability, equity, and gender equality. Findings show that female leadership promotes inclusive and strategic actions that challenge traditional structures and generate positive impacts. Five categories emerged: female entrepreneurial leadership; gender equality stakeholders; social contribution; women’s economic development; and sustainable decision-making. These converge in the central category of female empowerment in sustainable entrepreneurial leadership. In conclusion, the emerging theory expands the understanding of women-led leadership in Latin America, revealing socially responsible business models that promote sustainability, inclusion, and challenge dominant power structures in the business world.

1. Introduction

This study examines business policies that promote a sustainable vision and gender equality in women-led enterprises, based on the conviction that organizations play a fundamental role in the development and construction of equitable societies (Parsons & Krugell, 2022). In this context, business policies serve as an essential tool for driving transformations toward higher levels of justice, while reflecting the political will of the sectors to address inequality issues affecting women in the Latin American region (Atkinson & Penrod, 2022).

The varying levels of progress regarding gender equality across Latin American countries reveal that there is still a long road ahead, especially concerning the strengthening of state capacities for the effective implementation of business policies aimed at reducing gender gaps Acevedo-Duque et al. (2021a). Despite the good practices and recommendations on female leadership to improve the business environment and productivity, inclusion stands out as a key component for increasing productivity through this leadership style within organizations (Ahl et al., 2023; Merkley et al., 2025).

However, the materialization of this aspect faces considerable challenges during its implementation (Columbus et al., 2020; Košíková et al., 2025). In response to this situation, Sistema B establishes defined criteria for good practices, urging companies to reflect on their activities and obtain certifications by adopting B principles.

In this context, it becomes imperative to make visible both the economic and social impacts of B Corps to influence the business sector, civil society, and governmental institutions (Columbus et al., 2020; Patel & Dahlin, 2022). This, in turn, will contribute to creating environments that promote inclusion more sustainably in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In this regard, human resource management plays a fundamental role in companies seeking to adopt a new management paradigm in the 21st century in Latin America (Paelman et al., 2021). This requires highly qualified collaborators with adequate competencies to occupy managerial roles. In doing so, leaders ensure stability and success in the markets where their products, goods, and services operate (Diez-Busto et al., 2022).

However, it is relevant to highlight that, since the reopening of businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic situation, business management has been characterized by actions led by both formal and informal figures, emerging from the cultural, social, and political principles of their environment. In this scenario, the role of women entrepreneurs and their social impact stands out, along with their function in society according to gender (Fonseca et al., 2022).

Although the old paradigms that limited organizational management exclusively to men associating it with strong, robust, intelligent, and perseverant characteristics have been overcome (Bulmer et al., 2021), the importance of providing opportunities to women in managerial roles has also been recognized, considering this inclusion as an essential condition to promote equality (Sterbenk et al., 2022). Nevertheless, knowledge gaps still persist regarding how business policies oriented toward sustainability and gender equality impact women-led enterprises in Latin America and how they contribute to closing gender gaps in organizational leadership.

This study explored the testimonies of organizations led by women who have demonstrated competencies and skills by establishing and certifying their ventures internationally (Fonseca et al., 2022). Furthermore, it analyzed the gender implications in business leadership globally, identifying the essential qualities and competencies to build credibility, trust, reputation, sustainability, and competitiveness in the market (Carlsson-Kanyama et al., 2010).

The management of female entrepreneurial leadership in Latin America and the Caribbean has gained significance in recent years due to its impact on sustainability and gender equality. However, despite advances, significant barriers persist for women in business management (Ullah et al., 2021). Business policies aimed at sustainability and gender equality have been identified as key factors in overcoming these barriers and promoting inclusive business growth (Hoobler et al., 2018). This study focuses on B Corps-certified companies in Latin America, particularly in countries like Chile, Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil, due to their representativeness and commitment to responsible business practices (Aparisi-Torrijo & Ribes-Giner, 2022).

The objective is to analyze how business policies aimed at sustainability and gender equality impact women-led enterprises in these countries, within the framework of the new 21st-century management paradigm. The research questions guiding this study are as follows: (1) How do business policies aimed at sustainability and gender equality impact women-led enterprises in Latin America and the Caribbean, considering the new 21st-century management paradigm? (2) How do these policies contribute to closing gender gaps and strengthening female leadership within this new business management paradigm?

With these questions, the present study sought to demonstrate the impact of entrepreneurial female leadership within the new management paradigm of 21st century B Corps. Grounded theory and labor inclusion indicators of women and youth, publicly available in the B Corps directory, were used as the basis. Inclusion is presented as one of the most significant challenges facing Latin America and the world, with women and youth being the most affected populations.

For this reason, the structure of this document includes, after the Introduction, a literature review that frames this study and defines its purpose; the Materials and Methods Section, which seeks to explain the processes from a hermeneutical perspective; the Results Section, which presents a new theory; followed by the Discussion and Conclusion.

2. Background

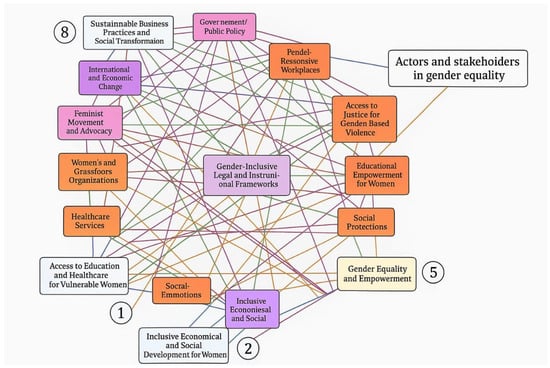

2.1. Actors and Stakeholders in Gender Equality from a Business Management Perspective

Addressing cutting-edge trends within organizations requires the incorporation of female leadership. This concept attributes qualities to a collective, not only from a psychological perspective but also considering social, public management, and business-related factors that have been critically examined (Reichert et al., 2021; Sidani et al., 2015). These categorizations often reflect stereotypical views of reality, characterizing approaches that seek to assess the effects of contributions and management styles from a labor role perspective (Siegel et al., 2020). However, it is acknowledged that completely avoiding such categorization may be challenging, especially when addressing current adaptation trends in the business world.

Nevertheless, although the academic literature has made progress in recognizing the value of female leadership, significant gaps persist in understanding how these leadership traits influence specific organizational contexts, particularly within startups, emerging economies, and sustainability driven enterprises. Zhang et al. (2022) emphasize this shortcoming, observing that current studies often generalize the impact of female leadership without accounting for variations in industry type, organizational culture, or stages of business development.

This lack of differentiation limits the development of more nuanced and context sensitive theoretical models, highlighting the need for targeted research. Figure 1 below reinforces this perspective by illustrating a network of entrepreneurial associations across Latin America including ASEM (Mexico), ASEC (Colombia), ASEP (Peru), ASECH (Chile), and ASEA (Argentina) alongside initiatives such as Mujeres del Pacífico. These organizations actively promote inclusive leadership and female entrepreneurship, underscoring the importance of studying how gendered leadership manifests within diverse, locally grounded innovation ecosystems (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Company Certification B Corps. Source: Mujeres del Pacifico https://mujeresdelpacifico.org/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

In response to this, Mujeres del Pacífico has conducted and managed various studies aimed at understanding and analyzing women entrepreneurs and their ecosystems across Latin America, particularly in countries such as Chile, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina (Ullah et al., 2021). These investigations have been grounded in extensive field experience and the systematic collection of information derived from daily, direct engagement with women entrepreneurs (Aparisi-Torrijo & Ribes-Giner, 2022).

As a result, the organization has positioned itself as a key entity in generating valuable knowledge for government bodies, multilateral institutions, and civil society organizations, with the goal of supporting, making visible, and strengthening female entrepreneurship in the region. In Chile, for instance, 40 companies were recognized, including Mujeres del Pacífico, for their commitment to sustainable development. This organization strives to generate tangible impact in alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

However, as Zhang et al. (2022) caution, many of these initiatives lack rigorous evaluation of the long-term impact of female leadership on sustainability, innovation, and business resilience indicators. The existing literature tends to focus on qualitative descriptions or case studies, leaving limited quantitative evidence that would allow for systematic comparison of female leadership outcomes against other styles. This limitation represents a key opportunity for future research aimed at measuring and comparing organizational performance under different leadership approaches, using mixed methodologies and longitudinal studies (Joga-Elvira et al., 2021).

This theoretical review supports various propositions derived from research suggesting that women exercise leadership differently from men (Aparisi-Torrijo & Ribes-Giner, 2022). Women tend to employ more consensual and mediating criteria when leading, in addition to using specific strategies to achieve successful results aligned with the strategic planning goals of their businesses (De Masi et al., 2021). However, there is still limited research on how these strategies adapt to contexts of crisis, digital transformation, or regulatory changes, which could enrich the academic debate and provide applicable evidence for the development of inclusive public policies and management models (Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014).

2.2. Women Entrepreneurs and Their Impact as B Corporations

It is argued that the leadership of women entrepreneurs, focused on the sustainability of their processes, adopts a resilient and innovative management model (Rzemieniak & Wawer, 2021). Within this new perspective, work processes are reconfigured, assuming a leadership role characterized by impartiality, enthusiasm, determination, and dedication. This vision highlights a form of leadership that has been historically overlooked, as research on gender differences in business leadership has tended to focus on male experiences, neglecting the specific contributions of women (Hoobler et al., 2018).

Their commitment impacts society, the environment, and their collaborators, emphasizing their ability to implement strategies that promote work–life balance, integration, commitment, and coordination within their teams (Hristov et al., 2021). This unique ability grants women entrepreneurs a privileged quality to humanize the business environment, aligning with people-centered values and acting as a social agent. However, despite these contributions, unanswered questions remain about how cultural and structural characteristics influence women’s capacity to lead sustainably, which could represent a critical gap in the current literature.

This phenomenon was evidenced in the Women’s Entrepreneurship Tour held in Chile in 2016, funded by the Chilean Economic Development Agency (Corfo) and supported by ASELA Asociación de Emprendedores de Latinoamérica. (s.f.) (2025). As part of the study, data were collected from more than 2000 women entrepreneurs to characterize the profile of Chilean women entrepreneurs. The research included a review of major global and Latin American studies on gender gaps and entrepreneurship.

Despite this progress, there are still gaps in understanding how institutional support structures and public policies in various Latin American countries such as Chile, Colombia, Peru, Paraguay, Argentina, Mexico, and Uruguay facilitate or hinder the success of women entrepreneurs, particularly within the context of B Corps. The current literature does not comprehensively address how these countries impact the effective implementation of B Corps strategies led by women, highlighting the need for studies more focused on the intersection between gender and each nation’s local context (Hoobler et al., 2018).

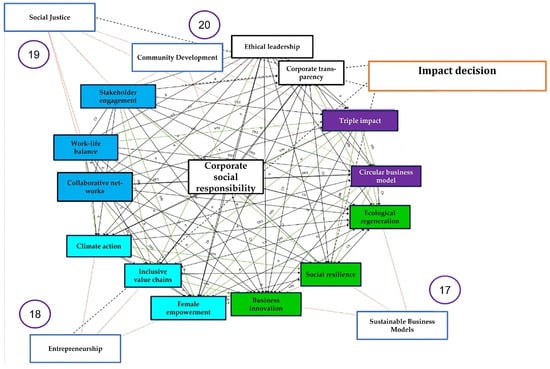

Regarding the connection between women-led ventures and B Impact, there is conceptual diversity among authors when addressing the term “B Corps”. B Corps are defined as hybrid companies that combine social goals with corporate social responsibility (Diez-Busto et al., 2020). B Corps that adopt innovative approaches and challenge traditional management paradigms are led by individuals with the power and legal obligation to consider interests beyond those of shareholders when making decisions (Diez-Busto et al., 2020) (see Figure 2). However, the available literature does not fully address how cultural, economic, and political differences between countries such as Chile, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina influence the implementation of these models in B Corps managed by women.

Figure 2.

B Corps company certification. Source: https://www.sistemab.org/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

In particular, it is relevant to note that the unit of analysis—composed of countries such as Chile with a presence in other nations like Colombia, Peru, and Paraguay, and expanding into markets such as Argentina and Mexico presents a unique landscape. B Corps operating in these contexts, whether headquartered in Chile or with a regional presence in Latin America, face diverse challenges in adopting and implementing sustainability and social responsibility strategies (Post & Byron, 2015). This scenario highlights the need for a more granular approach that considers local specificities within the global framework of B Corp and explores the differences and similarities in how women entrepreneurs in different national contexts manage these businesses under the B model.

This gap in the literature presents a valuable opportunity to examine how public policies and institutional support mechanisms across different Latin American countries shape the success or failure of women entrepreneurs within the B Corp model (Ryan & Morgenroth, 2024). Future research should explore how national contexts particularly in countries like Chile, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil influence the adoption and outcomes of B Corps strategies led by women.

Such analysis would provide deeper insight into the intersection between gender, sustainability, and entrepreneurship in the region (Javed et al., 2023). Figure 2 illustrates the multidimensional impact areas assessed in B Corps certification: governance, workers, community, environment, and customers; these are central to understanding how women entrepreneurs navigate and lead in organizations committed to generating social and environmental value. This visual reinforces the complexity and systemic nature of the B Corp model and highlights the importance of examining gender dynamics within each of these interconnected pillars (see Figure 2).

2.3. Female Leadership in Sustainable Enterprises: Demystifying and Addressing Realities

The progress of women in leadership has slowed down (Duque et al., 2024). Women’s representation in the workforce and executive positions is one of the main topics of the Global Gender Gap Report 2023 by the World Economic Forum, which measures gender parity in 146 countries (Duque et al., 2024). Over the past eight years, the proportion of women hired in management positions has steadily grown by about 1% annually worldwide, according to the report.

However, this trend began to reverse in 2022, bringing the 2023 rate back to 2021 levels. Data show that, in 2023, women made up almost 42% of the workforce but held just over 32% of senior management positions, such as directors and vice presidents (B Lab, 2024). The World Economic Forum warns that progress towards gender equality has significantly slowed, and at the current pace, it will take 131 years to achieve full parity between men and women.

Clearly, leadership among women entrepreneurs aims to foster humanized business management capable of generating excellent results by harmonizing values (Diez-Busto et al., 2020). This approach focuses not only on business excellence but also on making enterprises attractive to those who operate them.

This perspective is defined as the process of seeking business balance, using concentration, coordination, and equilibrium as key skills (Diez-Busto et al., 2020). These skills, combined with experience, allow for analyzing the company’s history and projecting it sustainably in the long term. Moreover, strategies are implemented to achieve business success under female leadership.

The goal is to close existing gaps in women-led entrepreneurship, achieve gender equality, and empower all women (De Masi et al., 2021). This approach helps create a source of learning and promotes sustainable and inclusive economic development. In line with the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), B Corps managed by women align to drive six specific objectives: financial inclusion, skills improvement in education, gender equality, work for developing countries, reduction in inequality, and assistance in building impact ecosystems (De Masi et al., 2021)

This reflects how humanity has evolved towards sustainability, although differences persist that influence participation in social, cultural, and political activities, affecting the presence of women leaders in companies (González-Díaz et al., 2021). The leadership capacity of women is highlighted, as they demonstrate competence in leading personal and collective lives, proving their ability to lead groups in society. This approach aims to serve as an intermediary to protect personal and collective interests through a sense of responsibility and commitment, showcasing women’s authenticity as leaders in 21st-century organizations.

2.4. Theoretical Articulation: Female Leadership, Sustainability, and the B Corp Model

Female leadership in the business context has been the subject of analysis in various studies, highlighting its distinctive characteristics in terms of style and approach, which tend to be more collaborative, inclusive, and focused on team well-being (De Masi et al., 2021). These approaches, based on empathy and consensual decision-making, are increasingly valued in a business environment that seeks to transform its role in society and adopt sustainable practices. However, there is still limited explicit articulation between female leadership styles and sustainable business models, particularly within B Corps.

B Corps, defined by their dual commitment to social and environmental impact alongside economic profitability, require leaders capable of aligning financial objectives with broader societal and ecological needs (Diez-Busto et al., 2020). In this context, female leadership presents a distinct advantage through its capacity to foster a more holistic business approach that balances profit-making with positive social and environmental transformation (Hristov et al., 2021). However, while the existing literature often highlights the strengths of female leadership in B Corps, it tends to overlook the complex role that public policies play in shaping the development and effectiveness of women-led B Corps. A deeper analysis of how national policy frameworks such as those aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Beijing Platform for Action influence female entrepreneurship within the B Corp movement is necessary to fully understand these dynamics and their impact on sustainability outcomes.

The analysis of the existing literature reveals that while the potential of female leadership to drive more human and ethical business management is recognized, the evidence of how this leadership specifically affects sustainability metrics within the B Corp model remains limited (Ryan & Morgenroth, 2024). This gap is particularly notable in the Latin American context, where cultural, economic, and political particularities significantly influence the implementation of sustainability strategies in B Corps led by women. In this regard, it is essential to consider how differences in regulatory frameworks and public policies in countries like Chile, Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina affect women’s ability to lead businesses that not only seek profitability but also promote social equity and environmental sustainability (Paeleman et al., 2024).

On the other hand, female leadership also faces both internal and external challenges in implementing sustainability strategies. Internally, women entrepreneurs must overcome structural and cultural barriers that have historically limited their access to leadership roles in the business field (Hoobler et al., 2018). Externally, social expectations and governmental regulations may create tensions regarding how to balance economic goals with sustainability objectives. These tensions require critical reflection on the role of public policies and institutional support structures in creating an environment that favors female leadership within the B Corp model.

This analysis leads us to conclude that while female leadership holds significant potential for promoting sustainable business models, the lack of solid theoretical articulation between these elements limits our understanding of how they are interconnected (Acevedo-Duque et al., 2023). It is imperative, therefore, that future research not only recognizes the positive impact of female leadership on sustainability but also critically addresses the obstacles and challenges women leaders face in this context. Furthermore, the cultural and structural specificities of each country must be considered to design more effective support models that allow for female entrepreneurs to successfully implement sustainability strategies within the B Corp framework.

3. Materials and Methods

This research adopts a qualitative approach, as it considers human beings as knowledge producers and seeks to understand reality through the construction of meanings and the appreciation of social heterogeneity (González-Díaz et al., 2021). The research employs a methodological structure that is neither linear nor predetermined but emerges during this study’s development through an inductive process that reconstructs the realities of the subjects investigated from their natural environment. This study adopted a qualitative approach based on the post-positivist grounded theory method by Strauss and Corbin (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to develop a substantive theory that explains the studied phenomenon. An emergent and inductive design was used, reconstructing the realities of the subjects investigated in their natural environment.

3.1. Participants and Data Sources

A total of 9536 companies registered in the B Corps Registry worldwide were identified (B Lab, 2024). From this set, over 1000 belonged to the B Companies Directory in Latin America and the Caribbean, of which 130 are located in Chile, with origins and presence in other countries such as Peru, Paraguay, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Additionally, research was conducted on the main social networks of the B system in Latin America and the Caribbean, where interesting testimonies from businesswomen were found, reflecting their approach to serving a society that needs to promote sustainability (Birks & Mills, 2015).

Out of the 130 certified companies in the mentioned countries, approximately 70% were dedicated to services, consulting, talent acquisition, and technology, while only 16 focused on the entrepreneurship support industry (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). These 16 B Companies were selected based on their alignment with this study’s theoretical interests: they are led by women, focus on entrepreneurship support, maintain updated B certification as of 2023, and have expanded operations to multiple Latin American countries. The selection process was guided by theoretical sampling, which prioritized rich sources of information over statistical generalizability (Conlon et al., 2020).

The companies were identified through a combination of structured searches in the official B Companies Directory and a review of public content shared via the B System’s regional social media (Daumé et al., 2009; B Lab, 2024). This approach enabled the identification of organizations with high visibility, validated leadership practices, and sectoral influence in promoting sustainability and inclusion.

A theoretical sampling strategy was applied using inclusion and exclusion criteria that considered (1) women-led organizational leadership, (2) geographic expansion to at least one other Latin American country, (3) minimum of three years of operation, and (4) available public testimony reflecting the organization’s values and practices (McLean et al., 2020).

The final sample size, consisting of 16 companies, was established based on the criterion of theoretical saturation (McLean et al., 2020). This was identified empirically by observing that, after the detailed analysis of the first 12 organizations, no new relevant categories or concepts emerged from the data, indicating sufficient thematic and conceptual recurrence (Denzin, 2001). This criterion was applied through a process of open and axial coding, during which repetitive interpretative patterns and a lack of new information in the last interviews analyzed were documented (González-Díaz et al., 2021). The four additional cases were included to confirm the stability and consistency of the emerging theory, thereby strengthening the analytical validity of this study (Krejić et al., 2018). It is worth noting that no refusal or dropout rates were recorded during the data collection process.

The unit of analysis covered dimensions such as industry, number of certified companies, origin/presence, product or service, and impact (see Table 1). These organizations operate in various sectors of entrepreneurship according to the B Corp system in Latin America and the Caribbean (B Lab, 2024).

Table 1.

Unit of analysis: women-led companies in the entrepreneurship support industry.

3.2. Data Collection Processes

The data were collected from testimonies of women entrepreneurs and representatives of the B System in Latin America and the Caribbean, information that is publicly available, showcasing their management practices and impact strategies within the industries they represent (B Lab, 2024). Additional testimonies were gathered from public sources such as social media publications from the B System and the official B Corps directory, which provided access to genuine and diverse perspectives on female leadership in these types of organizations (B Lab, 2024). The analysis focused on identifying experiences, perceptions, and challenges expressed by these leaders regarding sustainable management and the economic and social impact of B Corps. This approach ensured the authenticity and representativeness of the information, complementing the analysis with a broad and contextualized view of the phenomenon under study.

As part of the axial coding phase, a code density table and a co-occurrence matrix were developed. These tools allowed for us to visualize the frequency and interconnection of codes across all data units (Denzin, 2001). The highest-density codes such as transformational female leadership, female economic empowerment, and social impact and Sustainability were also the most interrelated, appearing together in more than 60% of the analyzed segments. These findings contributed to the consolidation of theoretical categories and the interpretive network presented in the results.

3.3. Data Coding, Analysis, and Interpretation

The data coding, analysis, and interpretation process followed an iterative and emergent approach grounded in the principles of open, axial, and selective coding. This method facilitated the identification of emerging categories and the development of a substantive theory, as proposed by González-Díaz et al. (2021). Rooted in the Straussian perspective (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, 1998), this approach supports an argumentative framework that recognizes the complexity of human reality, particularly in relation to sustainability, equality, and equity, which cannot be reduced to purely physical or material categories.

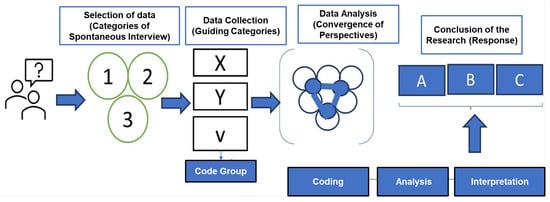

To ensure rigor and coherence in the qualitative process, five hermeneutical phases adapted from González-Díaz et al. (2021) were implemented. Figure 3 illustrates this analytical sequence, visually representing the transition from initial data collection to the convergence of perspectives and the formulation of conclusions. This figure is particularly relevant, as it clarifies the logical flow and methodological depth of the coding process, reinforcing the transparency and validity of the interpretive results (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Source: Naturalistic research route for management studies González-Díaz et al. (2021).

- Stage 1. Problem question (PQ): This study addresses key questions that challenge different approaches to the problem and guide the direction of the research. The methodology was applied based on the perspectives of the informants on each specific topic. How do corporate policies focused on sustainability and gender equality impact women-led businesses in Latin America and the Caribbean, considering the new management paradigm of the 21st century? Additionally, how does female entrepreneurial leadership influence the implementation of these policies, and what is its contribution to the creation of more inclusive and sustainable business environments, in line with labor inclusion indicators for women and youth?

- Stage 2. Collection of spontaneous categorical testimonies (RTEC): The construction of the RTEC was based on three approaches applied to key informants without establishing categories a priori, which allowed for the identification of emerging categories inductively.

- Stage 3. Guiding categories (GCs): Open coding was applied based on the word cloud, which facilitated the grouping of codes into guiding categories that address the trends, challenges, and proposals of corporate policies in the management of B Corps in Latin America for female entrepreneurial leadership. Two researchers participated in the coding process to increase inter-categorical validity. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus, and the analytical process was documented to ensure methodological transparency.

- Stage 4. Convergence (C): The convergence of informants was grouped according to the guiding categories using the quotes and open codes, and a semantic network was established.

- Stage 5. Analysis and interpretation of results (AIR): The software program Atlas.Ti9 was used to generate semantic networks with open codes, rooting tables, and density charts, which allowed for the interpretation of the results and the development of substantive theory.

3.4. Ethical Criteria

Qualitative validity and methodological integrity were ensured through the application of data triangulation strategies, reflexivity, and verification of theoretical saturation (De Masi et al., 2021). Feedback was provided to participants to corroborate the coherence and credibility of the findings, and a continuous reflexivity approach was adopted to minimize biases and influence the research process ethically. Additionally, information was obtained from public data in the B Corps directory [https://www.sistemab.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2024)] (B Lab, 2024), as well as from the main social media networks of the companies included in the B System, ensuring compliance with ethical principles according to the Helsinki Declaration. The confidentiality of information was protected through the storage of data on a restricted access server.

4. Results

The results of this research are significant, as after using the grounded theory methodology, it stood out for its ability to describe the researched phenomenon in great detail, allowing for the discovery of the research theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This approach is chosen by many researchers because it enables immersion in the reality of the studied phenomenon (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In this research, it allowed for adjusting the direction and framework of the investigative interest in real time as new findings and information emerged from the hermeneutic approach, guiding categories, and the identified code group (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Hermeneutic approach.

To strengthen the transparency and methodological rigor of the qualitative phase of this research, the following table presents a synthesis of the main categories, their frequency of appearance, co-occurrences, and the codes identified through axial coding and constant comparative analysis. This matrix serves to evidence the analytical saturation reached and supports the thematic robustness of the categories developed (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Code density and co-occurrence table.

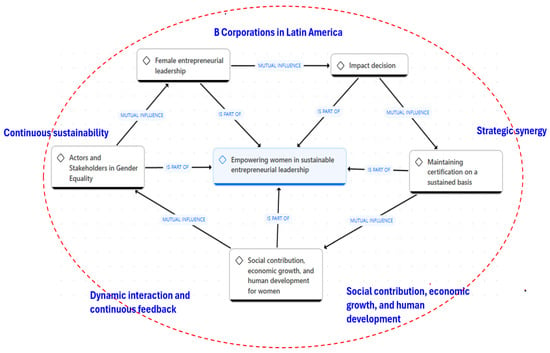

This central category emerges as a dynamic and multifaceted process that links the five emerging categories: entrepreneurial female leadership (PC-01); actors and stakeholders in gender equality (PC-02); social contribution, economic growth, and human development for women (PC-03); sustaining certification (PC-04); and impact decision (PC-05).

4.1. Result Category Outcome: Entrepreneurial Female Leadership (PC-01)

Entrepreneurial female leadership emerges as the foundation of the central category by representing the role of women as agents of change in the business world (Birks & Mills, 2015). This leadership not only challenges traditional paradigms but is also defined by an inclusive and strategic vision involving sustainable practices. The results from the testimonies show that entrepreneurial female leadership refers to the role and leadership qualities exercised by women in the business field (Askarzadeh et al., 2025) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Category outcomes: Entrepreneurial female leadership (PC-01).

This type of leadership involves women’s ability to start, lead, and manage business projects, whether as individual entrepreneurs, small business owners, or leaders in larger organizations (Patra & Lenka, 2024). The findings from the studied data show that entrepreneurial female leadership is distinguished by the unique perspective, skills, and strategies that women leaders bring to the business world. It includes the ability to make informed decisions, effectively manage resources, and create inclusive work environments (Kakeesh, 2024). It is seen as a manifestation of strategic vision in the business field, where women assume leadership and management roles that go beyond the economic realm by integrating sustainable practices. One of the interviews stated:

“Our business aims to reduce deforestation rates in Chilean territory and other regions of Latin America. We also contribute to the recovery of the Tropical Dry Forest ecosystem, which now only accounts for 8% of what originally existed in our region”.(C002, S, CL, CO, MX)

Additionally, some businesswomen have implemented strategies that combine business growth with corporate social responsibility focused on the well-being of their staff and environmental commitment. One participant said: “The leadership of our company focuses on more than 50% of our turnover being allocated to social housing projects, providing support to low-income families” (C018, CL, P, S).

These practices highlight a female leadership model focused on social impact and environmental sustainability:

“Our contribution through consultations and projects to corporations and foundations represents more than 20% of our turnover. Additionally, more than 30% of our profits are directed to benefits for workers. We also implement a strong waste recycling plan”.(C012, CL, S)

The testimonies reflect the participants’ ability to generate employment, which could reduce social vulnerability: “Our initiative stands out for leading the creation of jobs in vulnerable communities, the use of natural fibers, and raising awareness about the importance of the consumer in the value chain” (C009, CL, AR, P, U). Another businesswoman stated: “The leadership of our company is focused on more than 50% of our turnover being allocated to social housing projects, providing support to low-income families. Every time we eat, we choose the world we want to live in.” (C018, CL, P, S,) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Testimony of Carolina Colagreco, co-founder and head of supply and product development at CARNE company (B Lab, 2024).

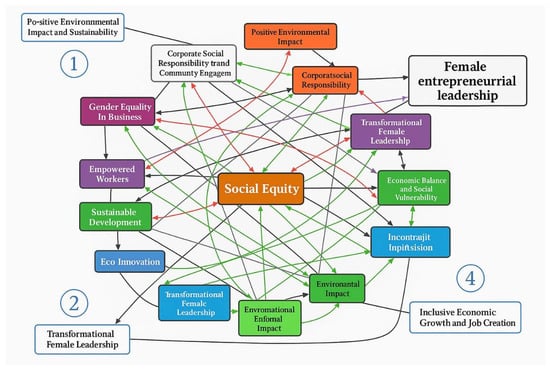

4.2. Result Category: Actors and Stakeholders in Gender Equality (PC-02)

This category highlights the importance of building strategic alliances with key stakeholders to promote gender equality and the empowerment of women in the workplace and society, driven by entrepreneurial leadership that fosters inclusive and equitable policies (Schmidt et al., 2024). The commitment to gender equality and the empowerment of women is universally agreed upon by Member States and encompasses all areas of peace, development, and human rights. The gender equality mandates universally agreed upon by the United Nations Member States are based on the United Nations Charter, which unequivocally reaffirmed the equality of rights for women and men (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Category: Actors and stakeholders in gender equality (PC-02).

The Fourth World Conference on Women held in 1995 advocated for the integration of a gender perspective as a fundamental and strategic approach to achieving commitments to gender equality (Tzanakou et al., 2024). The resulting Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action urge all stakeholders involved in development policies and programs, including United Nations organizations, Member States, and civil society actors, to take action in this regard (Kos et al., 2024). Additional commitments are included in the final document of the twenty-third special session of the General Assembly, the Millennium Declaration, and various resolutions and decisions from the United Nations General Assembly, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, and the Commission on the Status of Women.

The findings show that women entrepreneurs are committed to the principle of gender equality through the implementation of inclusive business policies and the promotion of socially equitable labor practices (Balkmar et al., 2024). One interviewee expressed how her company has integrated policies that support its social, economic, and environmental commitment, without overlooking the empowerment of women in the workplace:

“Our enterprise has policies that support its social, economic, and environmental commitment. Its main objective is to accompany clients with payment difficulties at each stage of the process, helping them recover their credit stability; it also offers services that contribute to the quality of life of Chilean women. 76.77% of its workforce is women, and they are part of populations that, in the national context, face barriers to accessing formal employment. Certified in standards that guarantee the quality of its services. It also measures and compensates for its environmental impact, reaffirming its commitment to caring for the planet”.(C012, CL)

There was also evidence of specific inclusive business strategies for women in exclusionary situations, by creating job opportunities that can contribute to the social development of their communities: “Our business slogan focuses on offering employment to women with barriers to employment and providing opportunities to people facing labor challenges, while promoting and facilitating recycling initiatives in the area.” (C008, CL, CO, PE, PAR).

It was also found that women’s entrepreneurial leadership extends to addressing the health needs of women in the lowest income brackets: “The clinic treats more than 50 patients annually, 80% of whom are low-income women with complex pathologies, offering them all maxillofacial rehabilitation services free of charge or at very low cost.” (C033, S, CL)

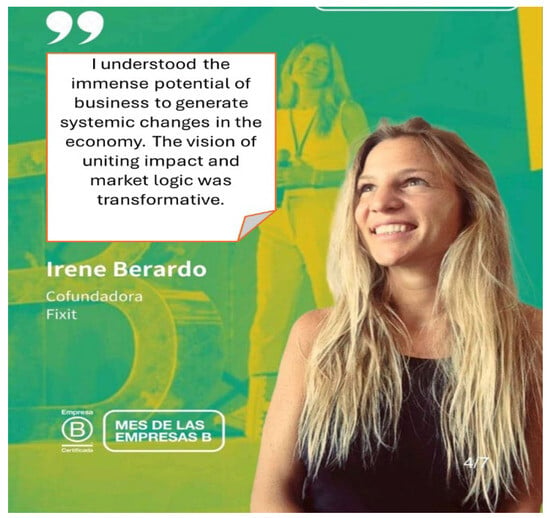

On the other hand, there is evidence of a gender equality approach that encompasses the personal development and empowerment of women by investing in women’s education and cultural development. One businesswoman stated:

“Our company seeks to make significant contributions to the education of single mothers and to culture in order to achieve the integral development of individuals and transform society. To achieve this goal, we offer comprehensive solutions for schools and cultural proposals in the areas of children’s literature, gender equality, and religion. I understood the immense potential of businesses to generate systemic changes in the economy. The vision of combining impacts and market logic was transformative”.(C046, CL. ARG) (see Figure 7) Figure 7. Testimony of Irene Berardo, co-founder of the company Fixit (B Lab, 2024).

Figure 7. Testimony of Irene Berardo, co-founder of the company Fixit (B Lab, 2024).

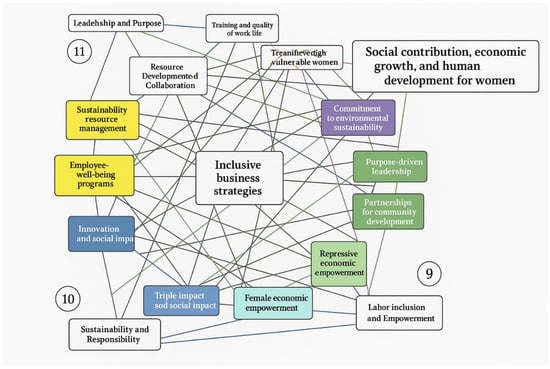

4.3. Result Category: Social Contribution, Economic Growth, and Human Development for Women (PC-03)

Women entrepreneurs in B Corps not only drive economic growth but also foster comprehensive human development in their communities by empowering vulnerable women and promoting environmental sustainability (Guo et al., 2024). When the number of employed women increases, economies grow. According to studies conducted in countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and some non-member countries, an increase in women’s participation in the workforce or a reduction in the disparity between female and male participation in the workforce leads to faster social and economic growth and impact (Ali et al., 2022) (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Category: Social contribution, economic growth, and human development for women (PC-03).

Human development is linked to labor inclusion and economic empowerment. A business vision was found that combines social responsibility through workforce qualification and work life quality, along with a commitment to environmental sustainability. The businesswomen stated:

“Our company strengthens its workforce by training its staff in labor matters and for a better quality of life, develops recreational activities, promotes the care and preservation of the environment, as well as waste control with certified companies. It also supports the Belén Educa foundation by offering job opportunities to young women in vulnerable situations”.(C081, CL)

There is evidence of female entrepreneurial leadership that integrates women’s economic empowerment, purpose-driven leadership, and environmental sustainability. This approach aligns with the B Corps vision, as business success is measured in economic terms and desirable social and environmental impacts. One entrepreneur stated about her company:

“Lácteos Tronador (…) cares for animal welfare, employing a productive model that enables the feeding of cows in a natural environment, monitoring their health and caring for the fields and rooms. On the other hand, they aim to be leaders in sustainability in the industry, using green water for irrigation and room washing, and incorporating organic fertilizers and biostabilizers into the fields. Finally, they are committed to the community of female workers, creating alliances through foundations, with schools and technical institutes, promoting local hiring and fostering the professional development of their workers”.(C087, P, CL)

Additionally, businesses led by women are characterized by innovative leadership that extends to social and territorial regeneration through triple impact initiatives. One entrepreneur shared:

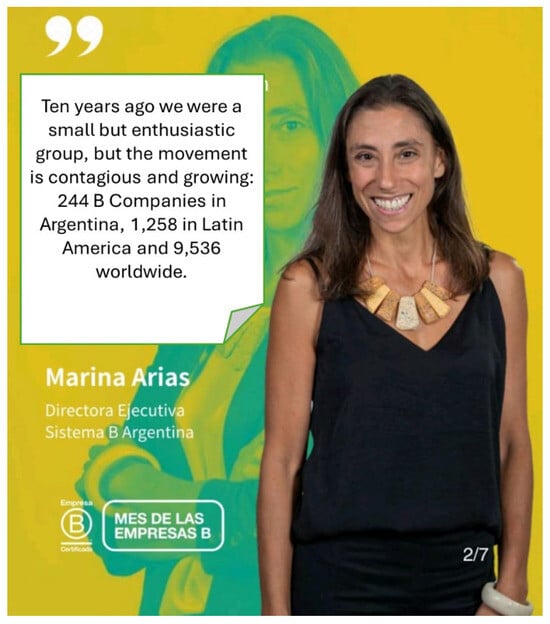

“Our company was created with the motivation to be an empirical experience of triple impact social entrepreneurship originating from rural reality, to know from practice how to enter the market with products full of awareness. From that experience, we aim to generate alliances, inspire, and support others in developing purpose-driven ventures that contribute to territorial regeneration and the heart of the human being. Ten years ago, we were a small but enthusiastic group, but the movement is contagious, and it keeps growing: 244 B Corps in Argentina, 1258 in Latin America, and 9536 worldwide”.(C141, CL, CO, PAR, AR) (see Figure 9) Figure 9. Testimony of Mariana Arias, executive director of Sistema B, Argentina (B Lab, 2024).

Figure 9. Testimony of Mariana Arias, executive director of Sistema B, Argentina (B Lab, 2024).

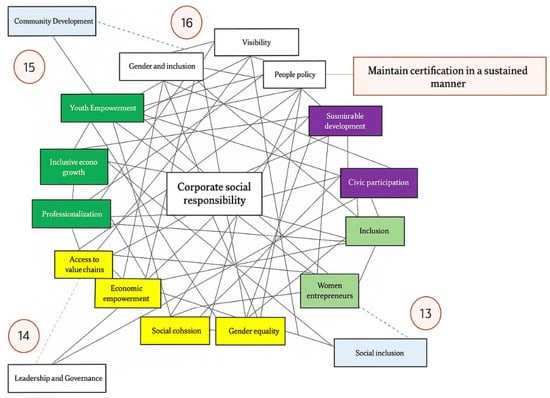

4.4. Category: Maintaining Certification in a Sustained Manner (PC-04)

The sustained maintenance of B Corporation certification reflects a genuine commitment to sustainability and inclusion (Pedersen et al., 2025). This category illustrates how women leaders incorporate ethical and sustainable practices into their business models, fostering a more just and equitable corporate environment. Among the array of best practices and recommendations for improving the environment and productivity of a company, the inclusion factor stands out as a key component in improving productivity. However, this aspect faces challenges in its implementation (Keser Kurşun et al., 2024) (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Category: Maintaining certification in a sustained manner (PC-04).

In response to this situation, Sistema B generates clear parameters for best practices, in which companies reflect on their activities and can certify themselves in implementing B principles (Keser Kurşun et al., 2024). For this reason, the economic and social contributions of B Corporations need to be highlighted to ensure that their practices influence other business sectors, civil society, and government institutions that can create environments favoring inclusion in Latin America.

Inclusion is highlighted as a key component in improving the productivity and competitiveness of B Corporations (Ali et al., 2022; Bringas-Fernández et al., 2024). In this sense, women entrepreneurs develop comprehensive support ecosystems for entrepreneurship, favoring gender equity, social cohesion, and inclusive economic growth:

“We are focused on supporting the economic empowerment and professionalization of women entrepreneurs in Latin America, through providing training, connecting them with key resources, access to value chains, and giving them visibility, as well as creating the largest network of women entrepreneurs in the region”.(C141, CL)

Investment in education and knowledge transfer reflects a real commitment to gender equity and the economic empowerment of women:

“We generate financial resources for the development of educational projects for women who want to become entrepreneurs. We transfer cutting-edge knowledge from the School of Engineering to society. We provide specialized services to solve specific problems and develop large-scale, relevant, and diverse projects for people”.(C041, CL)

Women entrepreneurs project their commitment to gender equality, equal pay between men and women, and an organizational mission grounded in social justice and labor well-being. One entrepreneur stated:

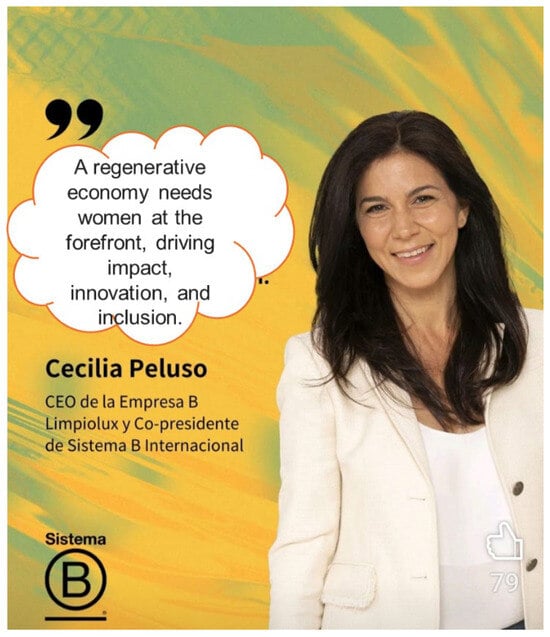

“The company promotes gender equality within the organization by ensuring equal pay between men and women and fostering gender parity through the incorporation of women at all organizational levels and areas. The company has a written People Policy that promotes the development of each member’s full potential and establishes clear rules regarding discrimination, workplace harassment, and sexual harassment. A regenerative economy needs women at the forefront, driving impact, innovation, and inclusion”.(C042, S, CL) (see Figure 11) Figure 11. Testimony of Cecilia Peluso, CEO of the B Corporation Limpiolux and Co-chair of Sistema B Internacional (B Lab, 2024).

Figure 11. Testimony of Cecilia Peluso, CEO of the B Corporation Limpiolux and Co-chair of Sistema B Internacional (B Lab, 2024).

4.5. Result Category: Impact Decision (PC-05)

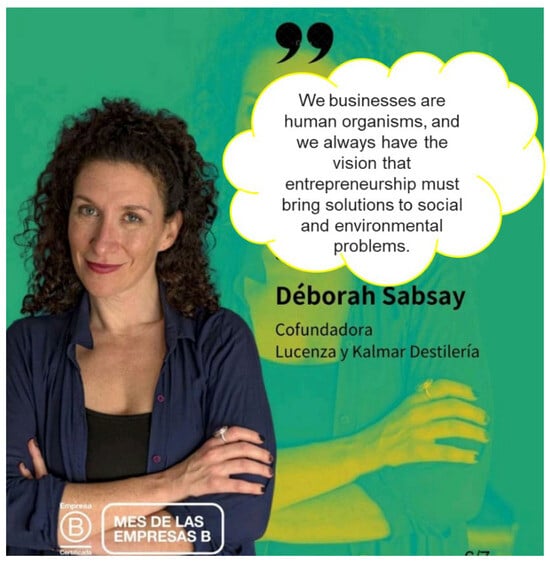

This refers to an impact that transcends the strategic and reveals an ethical and responsible leadership inherent in female empowerment in the business realm. Women leaders integrate social and environmental goals into their decisions, which can foster sustainable business changes (Boni et al., 2024). Increasingly, businesses and entrepreneurs are seeking transparency and measuring their social and environmental impacts (see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Category: Impact decision (PC-05).

B Corporations are not perfect, but they commit to continuous improvement and place their socio-environmental business purpose at the core of their business model (Sanchez-Chaparro et al., 2024). They thoroughly evaluate and analyze the five most relevant areas of their business: governance, workers, clients, community, and environment (Cruciata et al., 2024). This approach allows for a thorough review of all these areas to identify potential areas for improvement and opportunities to be change agents in the economy, protecting the mission while enhancing the triple impact (economic, social, and environmental).

An innovative business leadership model was revealed, based on a circular business model, which maximizes resource use and minimizes waste, thus reducing the environmental footprint (Villela et al., 2021). For example, a textile entrepreneur stated:

“Our company significantly addresses the environmental impact generated by waste in the textile industry. With a Hilana towel, we recycle what a person would recycle in eight years. We manufacture new products from textile waste, leveraging not only the raw material but also the dyeing process. Hilana products go through no chemical or dyeing processes, being 100% environmentally friendly”.(C075, CL, UR)

A well-directed impact decision capitalizes on ecological and social regeneration opportunities through the redefinition of urban space use and circus arts as a transformative tool that could promote resilience and emotional well-being. One interviewee said of her company:

“Companies are human organisms, and in us, there is always the view that entrepreneurship must attract solutions to social and environmental problems”.(C102, CL, GUAT, UR, BR) (see Figure 13) Figure 13. Testimony of Déborah Sabsay, co-founder of Lucenza and Kalmar Distillery (B Lab, 2024).

Figure 13. Testimony of Déborah Sabsay, co-founder of Lucenza and Kalmar Distillery (B Lab, 2024).

4.6. Result of the Emerging Substantive Theory

The emerging substantive theory on women’s empowerment in sustainable entrepreneurial leadership within B Corps in Latin America shows that it reconfigures economic and social challenges as strategic opportunities for inclusive growth and business sustainability (Kim, 2021). This process is achieved through a dynamic and continuous interrelation of five key categories within their business models: female entrepreneurial leadership, actors and stakeholders for gender equality, impact-driven decision-making, sustained certification maintenance, and social contribution, economic growth, and human development for women (Acevedo-Duque et al., 2021b) (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Emerging substantive theory.

The mentioned categories mutually influence each other in a cyclical process that simultaneously generates strategic synergies, co-construction of female empowerment, and permanent sustainability (Attanasio et al., 2025). It is interpreted as a phenomenon that redefines business practices through inclusive, socially responsible, and sustainable business models. This reconfiguration could promote gender equality and human development and consolidate itself as a transformative mechanism that strengthens social cohesion and inclusive growth (Pollmeier et al., 2025).

This substantive theory explains how female empowerment is configured as a dynamic process of entrepreneurial leadership. This process challenges traditional patriarchal structures and redefines business practices by building sustainable, equitable, and socially responsible business models (Pollmeier et al., 2025). Furthermore, it promotes gender equality and human development, establishing itself as a transformative mechanism that strengthens social cohesion and inclusive growth.

5. Discussion

This study, developed through grounded theory, enabled the construction of a substantive explanatory theory about female entrepreneurial leadership in B Corporations in Latin America. Through inductive procedures (Saiz-Álvarez et al., 2020; Boni et al., 2025), an emerging theoretical framework was built that critically engages with previous approaches. Unlike studies such as Boni et al. (2025), which address female leadership from a normative or functional lens, this work proposes a dynamic, emancipatory, and context-based perspective developed from the voices and experiences of the protagonists themselves.

5.1. Theoretical Articulation and Central Category

The central category identified female empowerment in sustainable entrepreneurial leadership acts as the core that articulates and integrates all emerging categories. This notion represents an integrative and transformative process in which women leading B Corporations turn social, economic, and cultural challenges into opportunities for equitable and sustainable growth (Kassemeier et al., 2022; Dudycz, 2022). As noted by Ferioli et al. (2022), this type of leadership intentionally incorporates gender equality, social responsibility, and human development into business models.

The theory developed argues that female empowerment not only enables a new form of leadership but also transforms organizational structures by challenging dominant patriarchal logics. This aligns with Ahl et al. (2023), who emphasize the disruptive nature of female leadership in relation to traditional power schemes.

5.2. Contributions and Contrasts with the Literature

The findings reinforce and expand the existing theoretical corpus. Authors such as Rzemieniak and Wawer (2021), Montiel Vargas (2022), and Gong et al. (2022) had already demonstrated the value of female leadership in processes of innovation and sustainability. However, this study goes further by proposing a situated understanding of the phenomenon, highlighting the role of collaboration networks, entrepreneurial sisterhood, and political advocacy as key dimensions of empowerment.

Moreover, the results align with prior studies that show how women entrepreneurs promote more horizontal and inclusive structures (Spitsin et al., 2022). It is confirmed that female leadership constitutes an emancipatory process that helps overcome structural barriers and contributes to building a fairer and more resilient business environment.

5.3. Emerging Theoretical Propositions

From the data analysis and the grounded theory developed, the following theoretical propositions emerged:

- P1: Female empowerment drives the transformation of leadership toward strategic, ethical, and sustainable models, challenging traditional hierarchical structures.

- P2: Women leaders in B Corporations integrate values of social justice, human development, and gender equity into their business vision, turning their organizations into platforms for structural change.

- P3: Interaction with support networks and collaborative communities strengthens female leadership, multiplying its social and economic impact.

These propositions contribute to the consolidation of an alternative theoretical framework on leadership and sustainability in Latin American contexts.

5.4. Final Synthesis of the Discussion

In conclusion, this research contributes a comprehensive framework explaining how female leadership in B Corporations in Latin America constitutes a transformative, emancipatory process deeply tied to sustainable development (Boni et al., 2024). By grounding the theory in local realities and the life trajectories of women leaders, it offers a robust and actionable perspective for academic, political, and business agendas aimed at fostering equity and sustainability.

6. Conclusions

Female empowerment in sustainable entrepreneurial leadership manifests as a dynamic and transformative process that challenges hegemonic patriarchal structures. The results of this study support the emergence of a substantive theory that contributes to the development of inclusive, equitable, and socially responsible business models that, in turn, foster inclusive economic growth and promote sustainable human development. This theory positions women not only as agents of change within organizations but also as key actors in redefining the values and purposes of business activity in a sustainability-driven world.

This research highlights that women’s leadership styles, when rooted in sustainability principles, tend to prioritize long-term value creation, ethical responsibility, and community well-being. These traits contribute to reshaping conventional notions of entrepreneurial success, moving away from short-term profit maximization toward a more holistic vision of impact. In this sense, the empowerment of women in leadership positions serves as a catalyst for broader institutional transformations that benefit not only organizations but also the societies in which they operate.

Moreover, this study suggests that female empowerment in sustainable entrepreneurship can act as a mechanism for democratizing access to leadership roles, reducing structural inequalities, and creating business ecosystems grounded in fairness and inclusion. This not only supports the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (particularly SDG 5 and SDG 8) but also fosters innovation through diverse leadership perspectives. When empowered, women entrepreneurs become powerful agents for ecological consciousness, social justice, and economic resilience, especially in emerging economies like those in Latin America.

By framing women’s leadership as a strategic component of sustainability, this research contributes to the urgent global conversation about the future of business in the face of climate, social, and economic challenges. The substantive theory derived from this study emphasizes the need for systemic changes in how entrepreneurship is taught, practiced, and supported, placing gender equity and sustainability at the core of transformative business models. Therefore, these conclusions not only validate the theoretical contribution of the research but also call for immediate action from policymakers, educators, and business leaders.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research offers important theoretical insights by conceptualizing female empowerment not only as a leadership practice but as a transformative force within sustainable entrepreneurship. This study advances the understanding of how gender perspectives intersect with sustainability principles in the context of B Corporations in Latin America. It contributes a novel theoretical framework that integrates ethical leadership, gender equity, and sustainable innovation, enriching the academic discourse on inclusive and sustainable business practices.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings have substantial practical implications. The proposed theory can guide the design of inclusive business policies and the implementation of leadership strategies aimed at enhancing women’s agency and participation. It also has practical applications in environmental sustainability by informing the development of responsible business practices in areas such as energy efficiency, waste and resource management, and the integration of circular economy strategies. B Corporations can apply this theory to promote business models grounded in ethics, equity, and environmental stewardship.

To foster sustainable and inclusive growth, it is essential to implement policies that actively support female entrepreneurship. These policies should enhance leadership skills, improve access to financing and networks, and foster environments in which women can thrive. Organizations must cultivate cultures of respect, diversity, and collaboration. Additionally, academic institutions should adapt entrepreneurship education by incorporating critical gender perspectives, ethical leadership, and care economy principles into curricula to better prepare future leaders.

6.3. Limitations

Although this study supports the proposed theory, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted in a specific geographical context within certain Latin American countries, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions with different cultural or economic conditions. Future studies could broaden this scope to assess wider applicability. Second, the focus was solely on women leaders, excluding perspectives from other relevant stakeholders such as partners, employees, and clients. Including these voices could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics in women-led enterprises. Finally, the qualitative nature of the study limits broad generalizations. Complementary quantitative research could help validate and extend these findings to larger populations.

6.4. Future Research Directions

Future studies should aim to test the applicability of the theory in diverse cultural and geographic contexts. Comparative studies with other sustainable business models would also be valuable to identify shared practices and unique approaches in managing social and environmental impacts. Expanding the scope to include a wider range of voices within organizations could further validate and strengthen the theoretical framework proposed in this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A.; methodology, Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A.; software, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; validation, Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A.; formal analysis, Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A.; investigation, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; resources, Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A.; data curation, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; writing—original draft preparation Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A.; writing—review and editing, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; visualization, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; supervision, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; project administration, Á.A.-D. and R.A.-B.; funding acquisition, Á.A.-D., R.A.-B., S.A.D.F., O.B.-S., G.C.-Á., M.M.F.-M. and C.V.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested by writing to the corresponding author of this publication.

Acknowledgments

To all entrepreneurial women who dare to showcase good leadership and their contribution to the care of resources in their nations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acevedo-Duque, Á., Gonzalez-Diaz, R., Vargas, E. C., Paz-Marcano, A., Muller-Pérez, S., Salazar-Sepúlveda, G., Caruso, G., & D’Adamo, I. (2021a). Resilience, leadership and female entrepreneurship within the context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America. Sustainability, 13, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á., Gonzalez-Diaz, R., Vega-Muñoz, A., Fernández Mantilla, M. M., Ovalles-Toledo, L. V., & Cachicatari-Vargas, E. (2021b). The role of B companies in tourism towards recovery from the crisis COVID-19 inculcating social values and responsible entrepreneurship in Latin America. Sustainability, 13, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á., Álvarez-Herranz, A. P., & Artigas, W. (2023). Contribution to the country brand through the sustainability of production processes in Chile: B Corp. Retos Revista de Ciencias de la Administración y Economía, 13(26), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H., Berglund, K., Pettersson, K., & Tillmar, M. (2023). Women’s contributions to rural development: Implications for entrepreneurship policy. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30, 1652–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Yan, Q., Irfan, M., Ameer, W., Atchike, D. W., & Acevedo-Duque, Á. (2022). Green investment for sustainable business development: The influence of policy instruments on solar technology adoption. Frontiers in Energy Research, 10, 874824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi-Torrijo, S., & Ribes-Giner, G. (2022). Female entrepreneurial leadership factors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 18(4), 1707–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASELA—Asociación de Emprendedores de Latinoamérica. (s.f.). (2025). ConnectAmericas. Available online: https://connectamericas.com/company/asela-asociaci%C3%B3n-de-emprendedores-de-latinoam%C3%A9rica?language=es (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Askarzadeh, F., Lewellyn, K., Fainshmidt, S., & Judge, W. Q. (2025). Entrepreneurial orientation and underconformity to female board representation norms. Journal of Management Studies, 62(2), 539–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C. L., & Penrod, C. (2022). Empowerment or limitation? A critical exploration of American state women-owned business programs. Public Organization Review, 22(2), 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, G., Battistella, C., & Chizzolini, E. (2025). B-Corp certification: Systematic literature review and research agenda. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 35, 3729–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkmar, D., Lindvert, M., & Ljunggren, E. C. (2024). Masculinity in Scandinavian tech entrepreneurship: Male technology entrepreneurs negotiating gender (in) equality. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 16(3), 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- B Lab. (2024). Why B corps matter. Available online: https://www.sistemab.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Boni, L., Calderini, M., & Bengo, I. (2024). It’s time for impact: An analysis of the prosocial signals in social enterprises. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, L., Fini, R., & Toschi, L. (2025). How B Corps are hybrid? Unpacking hybridity in social enterprises. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34, 4436–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringas-Fernández, V., López-Gutiérrez, C., & Pérez, A. (2024). B-CORP certification and financial performance: A panel data analysis. Heliyon, 10(17), e36915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, E., Riera, M., & Rodríguez, R. (2021). The importance of sustainable leadership amongst female managers in the Spanish logistics industry: A cultural, ethical and legal perspective. Sustainability, 13, 6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson-Kanyama, A., Juliá, I. R., & Röhr, U. (2010). Unequal representation of women and men in energy company boards and management groups: Are there implications for mitigation? Energy Policy, 38(8), 4737–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbus, A. B., Lu, P. W., Hill, S. S., Fields, A. C., Davids, J. S., & Melnitchouk, N. (2020). Factors associated with the professional success of female surgical department chairs: A qualitative study. JAMA Surgery, 155(11), 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, C., Timonen, V., Elliott-O’Dare, C., O’Keeffe, S., & Foley, G. (2020). Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciata, P., Pulizzotto, D., & Beaudry, C. (2024). First impressions on sustainable innovation matter: Using NLP to replicate B-lab environmental index by analyzing companies’ homepages. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 205, 123455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumé, H., Langford, J., & Marcu, D. (2009). Search-based structured prediction. Machine Learning, 75, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, S., Słomka-Gołębiowska, A., Becagli, C., & Paci, A. (2021). Toward sustainable corporate behavior: The effect of the critical mass of female directors on environmental, social, and governance disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(4), 1865–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K. (2001). Interpretive interactionism (Vol. 16). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Busto, E., Sanchez-Ruiz, L., & Fernandez-Laviada, A. (2020). Protocolo: Revisión sistemática de literatura sobre B-Corp. WPOM-Working Papers on Operations Management, 11(1), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Busto, E., Sanchez-Ruiz, L., & Fernandez-Laviada, A. (2022). B corp certification: Why? How? and what for? A questionnaire proposal. Journal of Cleaner Production, 372, 133801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudycz, T. (2022). Does share capital mater for company performance? Economic Research—Ekonomska Istraživanja, 35(1), 3035–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, Á. E. A., dos Santos, T. L., de Sousa Ferreira, A. C., Verges, I. Y., & Ubal, N. P. (2024). Liderazgo femenino emprendedor: Un enfoque de politicas empresarales en la gestión de empresas del sistema b en america latina. Boletim de Conjuntura (BOCA), 18(54), 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, M., Gazzola, P., Grechi, D., & Vătămănescu, E. M. (2022). Sustainable behaviour of B Corps fashion companies during Covid-19: A quantitative economic analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 374, 134010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L., Silva, V., Sá, J. C., Lima, V., Santos, G., & Silva, R. (2022). B Corp versus ISO 9001 and 14001 certifications: Aligned, or alternative paths, towards sustainable development? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(3), 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X., Lin, A., & Chen, X. (2022). CEO–CFO gender congruence and stock price crash risk in energy companies. Economic Analysis and Policy, 75, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Díaz, R. R., Acevedo-Duque, Á., Guanilo-Gómez, S., & Cruz-Ayala, K. (2021). Ruta de Investigación Cualitativa—Naturalista. Una alternativa para estudios gerenciales. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 28, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., & Hu, X. (2024). Cross-cultural patterns of gender differences in STEM: Gender stratification, gender equality and gender-equality paradoxes. Educational Psychology Review, 36(2), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J. M., Masterson, C. R., Nkomo, S. M., & Michel, E. J. (2018). The business case for women leaders: Meta-analysis, research critique, and path forward. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2473–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I., Appolloni, A., Chirico, A., & Cheng, W. (2021). The role of the environmental dimension in the performance management system: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 293, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M., Wang, F., Usman, M., Gull, A. A., & Zaman, Q. U. (2023). Female CEOs and green innovation. Journal of Business Research, 157, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joga-Elvira, L., Jacas, C., Joga, M. L., Roche-Martínez, A., & Brun-Gasca, C. (2021). Pilot study of socio-emotional factors and adaptive behavior in young females with fragile X syndrome. Child Neuropsychology, 27, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakeesh, D. F. (2024). Female entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 26(3), 485–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassemeier, R., Haumann, T., & Güntürkün, P. (2022). Whether, when, and why functional company characteristics engender customer satisfaction and customer-company identification: The role of self-definitional needs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 39(3), 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser Kurşun, E., Albadra, D., & Emmitt, S. (2024). Social sustainability in architectural practice: Examining experiences of architectural offices in B-Corp certification in the United Kingdom. Archnet-IJAR. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2021). Certified corporate social responsibility? The current state of certified and decertified B Corps. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(6), 1760–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, Ž., Mažgon, J., & Gaber, M. A. (2024). Academic standards and gender equality. Educar, 60(2), 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košíková, M., Šenková, A., Kolesárová, S., & Šambronská, K. (2025). A study of customer satisfaction with Slovakian spa companies: An importance-performance analysis. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 17(2), 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejić, N., Krklec Jerinkić, N., & Rožnjik, A. (2018). Variable sample size method for equality constrained optimization problems. Optimization Letters, 12, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K. C., Syed, M., Pasupathi, M., Adler, J. M., Dunlop, W. L., Drustrup, D., Fivush, R., Graci, M. E., Lilgendahl, J. P., Lodi-Smith, J., McAdams, D. P., & McCoy, T. P. (2020). The empirical structure of narrative identity: The initial Big Three. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(4), 920. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2019-21395-001. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkley, K., Pacelli, J., Sun, F., & Twedt, B. (2025). Common media holding companies and the uniqueness of business press content. The Accounting Review, 100(1), 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel Vargas, A. (2022). Las Empresas B (B Corps) y la regulación de las sociedades con propósito (benefit corporations) en Derecho comparado. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 141, e82253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paeleman, I., Guenster, N., Vanacker, T., & Siqueira, A. C. O. (2024). The consequences of financial leverage: Certified B Corporations’ advantages compared to common commercial firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 189(3), 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paelman, V., Van Cauwenberge, P., & Vander Bauwhede, H. (2021). The impact of B corp certification on growth. Sustainability, 13(13), 7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R., & Krugell, W. (2022). Policy uncertainty, the economy and business. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 25(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. C., & Dahlin, P. (2022). The impact of B Corp certification on financial stability: Evidence from a multi-country sample. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 31(1), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, B. C., & Lenka, U. (2024). Female entrepreneurial support requirements: Post pandemic ecosystems in India. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 26(4), 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., Walker, L. S., & Woehr, D. J. (2014). Gender and perceptions of leadership effectiveness: A meta-analysis of contextual moderators. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E. R. G., Andersen, K. R., Pedersen, F. H., & Bjartmarz, T. K. (2025). Ritual or reform? Untangling the B Corp certification process from a routines perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(2), 1864–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmeier, T., Hirschmann, M., & Fisch, C. (2025). Exploring the signaling effect of B Corp certification in entrepreneurial finance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 493, 144978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C., & Byron, K. (2015). Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of management Journal, 58(5), 1546–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]