An Assessment of the Roles of the Government, Regulators, and Investors in ESG Implementation in South Africa: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Discussion on the Key Actors in ESG Practices

2.1. Role of Investors in ESG Implementation

2.2. Role of Regulators in ESG Implementation

2.3. Role of Government in ESG Implementation

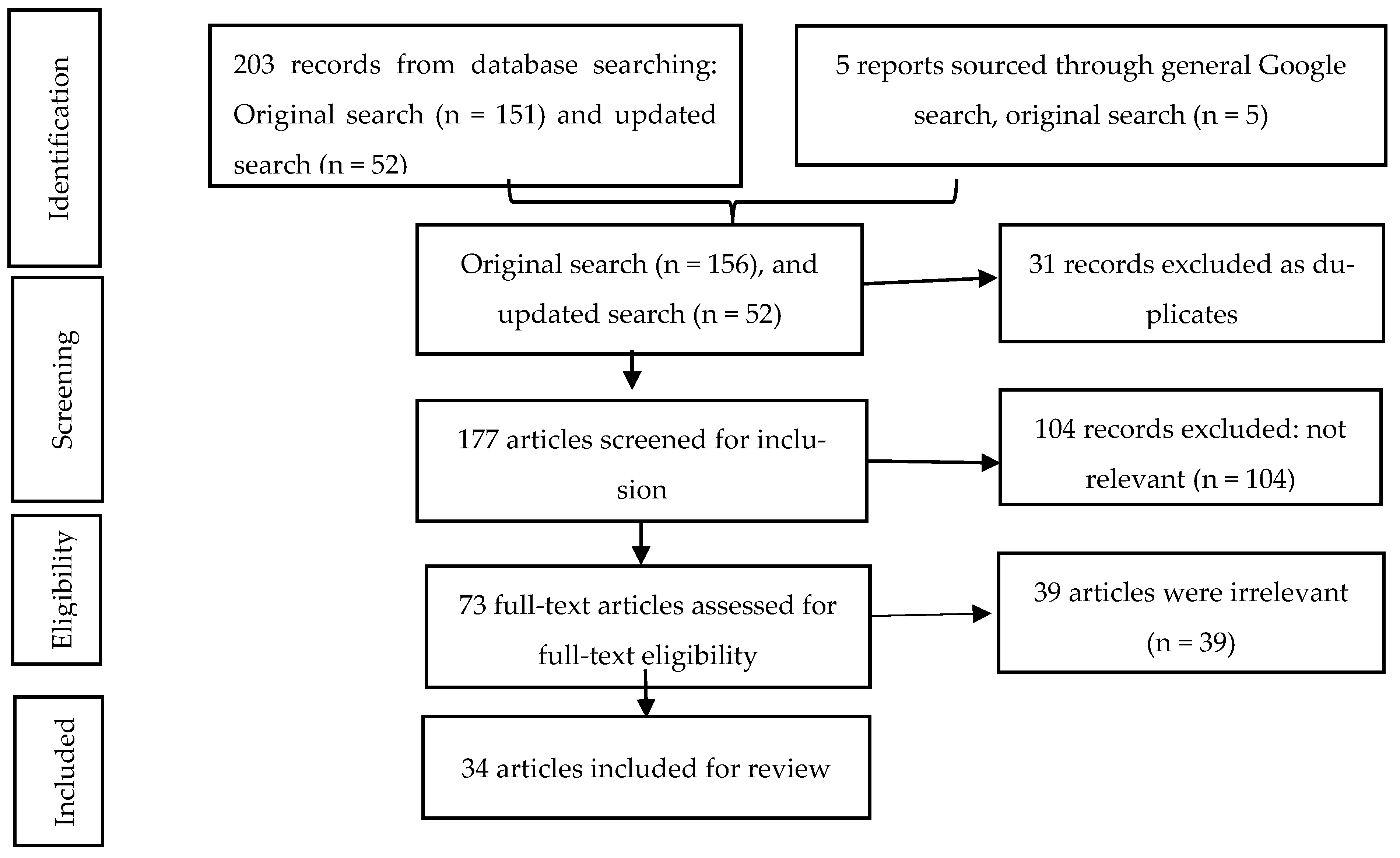

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Question Formulation

3.2. Identification of Relevant Articles

3.3. Study Selection

3.4. Vetting Process

3.5. Metadata

3.6. Compiling, Summarising, and Reporting the Results

4. Review of Selected Articles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environment, social, and governance |

| PRI | Principles for responsible investing |

| CRISA | Code for responsible investing in South Africa |

| B-BBEE | Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment |

| IoDSA | Institute of Directors South Africa |

| JSE | Johannesburg Stock Exchange |

| SRI | Socially responsible investment |

| SSEs | Sustainable stock exchanges |

Appendix A. Data Characterisation Screening Forms

References

- Akbarialiabad, H., Taghrir, M. H., Abdollahi, A., Ghahramani, N., Kumar, M., Paydar, S., Razani, B., Mwangi, J., Asadi-Pooya, A. A., Malekmakan, L., & Bastani, B. (2021). Long COVID, a comprehensive systematic scoping review. Infection, 49(6), 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, F., Hossain, M. R., Elrehail, H., Rehman, S. U., & Almansour, B. (2023). Environmental disclosures and corporate attributes, from the lens of legitimacy theory: A longitudinal analysis on a developing country. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 32(3), 342–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q., Salman, A., & Parveen, S. (2022). Evaluating the effects of environmental management practices on environmental and financial performance of firms in Malaysia: The mediating role of ESG disclosure. Heliyon, 8(12), e12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, M., & Bienstock, C. C. (2014). Corporate sustainability: An integrative definition and framework to evaluate corporate practice and guide academic research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 76, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, D. (2020). An index to measure the integrity of investment companies investing responsibility. Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, 5(5), 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrey, E. (2023). ESG as an innovative tool to improve the efficiency and financial stability of financial organizations. Procedia Computer Science, 221, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M., Gan, C., & Nadeem, M. (2022). Regulating non-financial reporting: Evidence from European firms’ environmental, social and governance disclosures and earnings risk. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(3), 495–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, W. T., Ani, D. A., Subranta, A., Solissa, F., & Wiriatmaja, N. U. (2024). Sustainable financial strategies: Analyzing the role of ESG in corporate financial performance and risk management. The Journal of Academic Science, 1(6), 813–820. [Google Scholar]

- Aubry, J. P., Chen, A., Hubbard, P. M., & Munnell, A. H. (2020). ESG investing and public pensions: An update. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College State and Local Pension Plans, 74, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bester, V., & Groenewald, L. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and artisanal mining: Towards a fresh South African perspective. Resources Policy, 72, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S. (2020). Evolution of ESG reporting frameworks. In Values at work: Sustainable investing and ESG reporting (pp. 13–33). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M., & Lagasio, V. (2021). An overview of the European policies on ESG in the banking sector. Sustainability, 13(22), 12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burival, Z. (2021). The emerging importance of the TCFD framework for South African companies and investors. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.za/our_research/publications/?33962/TCFD-framework-importance (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Caporale, G. M., Gil-Alana, L., Plastun, A., & Makarenko, I. (2022). Persistence in ESG and conventional stock market indices. Journal of Economics and Finance, 46(4), 678–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassim, R. (2022). An analysis of trends in shareholder activism in South Africa. African Journal of International and Comparative Law, 30(2), 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cort, T., & Esty, D. (2020). ESG standards: Looming challenges and pathways forward. Organization & Environment, 33(4), 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C. A., & Matos, F. (2023). ESG maturity: A software framework for the challenges of ESG data in investment. Sustainability, 15(3), 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSipio, A. (2023). ERISA fiduciary duties and ESG funds: Creating a worthy retirement future. Drexel Law Review, 15, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Peña, L. D. C., Castillo Delgadillo, V. M., & Mario Iván, C.-V. (2022). Financial firm’s performance: A comparative analysis based on ESG metrics and net zero legislation. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hage, J. (2021). Fixing ESG: Are Mandatory ESG Disclosures the Solution to Misleading Ratings? Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 26(2), 359. [Google Scholar]

- Fairfax, L. M. (2023). Dynamic disclosure: An exposé on the mythical divide between voluntary and mandatory ESG disclosure. Texas Law Review, 101, 273–337. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, R. (2020). The evolution and alignment of institutional shareholder engagement through the King and CRISA reports. Journal of Global Responsibility, 11(2), 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, D. G., & Ivanov, I. T. (2023). Gas, guns, and governments: Financial costs of anti-ESG policies. Gas, guns, and governments: Financial costs of anti-ESG policies (Working Paper No. 2023-07). Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamporcaro, S. (2011). Sustainable and responsible investment in emerging markets: Integrating environmental risks in the South African investment industry. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Giamporcaro, S., & Viviers, S. (2014). SRI in South Africa: A melting-pot of local and global influences. In C. Louche, & T. Hebb (Eds.), Critical studies on corporate responsibility, governance and sustainability (Vol. 7, pp. 215–246). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A. (2024). Danish pension fund divests from oil and gas firms expanding in production. Available online: https://www.netzeroinvestor.net/news-and-views/danish-pension-fund-divests-from-oil-and-gas-firms-expanding-in-production (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Hasselgren, A., Kralevska, K., Gligoroski, D., Pedersen, S. A., & Faxvaag, A. (2020). Blockchain in healthcare and health sciences—A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 134, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herringer, A., Firer, C., & Viviers, S. (2009). Key challenges facing the socially responsible investment (SRI) sector in South Africa. Investment Analysts Journal, 38(70), 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V. H., & Park, S. K. (2019). ESG disclosure in comparative perspective: Optimizing private ordering in public reporting. Journal of International Law, 41, 249–327. [Google Scholar]

- IFC. (2020). Sustainable finance practices in South African retirement funds (p. 66). Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA). Available online: https://www.fsca.co.za/Documents/South%20Africa%20Retirement%20Funds%20-Sustainable%20Finance%2004-02-21.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- ILO. (2022). Environmental Social Governance (ESG) and its implications for medium-sized enterprises in Africa (p. 31) [Training Guide]. International Labour Organisation. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_dialogue/%40act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_848406.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Johnson, R., Mans-Kemp, N., & Erasmus, P. D. (2019). Assessing the business case for environmental, social and corporate governance practices in South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongh, D., Ndlovu, R., Coovadia, C., & Smith, J. (2007). The State of responsible investment in South Africa (2007). UNISA Centre for Corporate Citizenship. UNEP. Available online: http://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/The_State _of_Responsible_Investment_01.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Jonsdottir, B., Sigurjonsson, T. O., Johannsdottir, L., & Wendt, S. (2022). Barriers to using ESG data for investment decisions. Sustainability, 14(9), 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaedi, J. (2024). Understanding the role of finance in sustainable development: A qualitative study on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices. Golden Ratio of Finance Management, 4(2), 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P., Sautner, Z., Tang, D. Y., & Zhong, R. (2021). The effects of mandatory ESG disclosure around the world. SSRN Electronic Journal, 62, 1795–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, J. F., & Montecinos-Pearce, A. A. (2021). ESG reporting: Empirical analysis of the influence of board heterogeneity from an emerging market. Sustainability, 13(6), 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, N. (2023). International best practice and a revised code for responsible investing in South Africa. South African Law Journal, 140(3), 550–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F. J., & Johnstone, S. (2023). Applying ‘Deep ESG’ to Asian private equity. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 13(2), 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvhengo, V. (2013). Public pension funds and socially responsible investment in South Africa: A case study of the Public Investment Corporation [Master’s thesis, University of Cape Town]. OpenUCT. Available online: https://open.uct.ac.za/items/a1c34c39-afbb-4b60-ae4c-86bb252651aa (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Magness, V. (2006). Strategic posture, financial performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(4), 540–563. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, A., Ding, D., & Hasan, M. M. (2021). Corporate social responsibility: Business responses to coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. SAGE Open, 11(1), 215824402098871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans-Kemp, N., & Van Zyl, M. (2021). Reflecting on the changing landscape of shareholder activism in South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 24(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, F., van der Lugt, C. T., & Mans-Kemp, N. (2022). Mainstreaming environmental, social and governance integration in investment practices in South Africa: A proposed framework. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 15(1), 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A., Orduna-Malea, E., Thelwall, M., & López-Cózar, E. D. (2018). Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of Informetrics, 12(4), 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenda, F. R., Sibanda, M., Chikodza, E., & Gumbo, V. (2022). Bankruptcy prediction for private firms in developing economies: A scoping review and guidance for future research. Management Review Quarterly, 72(4), 927–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubane, P., Prinsloo, A., & Van Rooyen, N. (2014). Sustainability reporting patterns of companies listed on the Johannesburg securities exchange. Public Relations Review, 40(2), 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milazi, M. A. (2016). South African banks footprint in SADC mining projects: Environmental, social and governance principles (p. 60). Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa. Available online: https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/files/documents/sa_banks_report-final-lowres.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Mohammad, W. M. W., & Wasiuzzaman, S. (2021). Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosure, competitive advantage and performance of firms in Malaysia. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, D. M. (2022). Sustainable investing and fiduciary obligations in pension funds: The need for sustainable regulation. American Business Law Journal, 59(4), 621–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. A., Yousaf, I., Karim, S., Tiwari, A. K., & Farid, S. (2023). Comparing asymmetric price efficiency in regional ESG markets before and during COVID-19. Economic Modelling, 118, 106095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Treasury. (2021). Financing a sustainable economy: Technical paper 2021 (p. 60). National Treasury South Africa. Available online: https://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/press/2021/2021101501%20Financing%20a%20Sustainable%20Economy.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Nyiwul, L., & Iqbal, B. A. (2022). Evidence on divestment motives: An overview. Global Trade and Customs Journal, 17(11/12), 501–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbuka, B. A., & Fakoya, M. (2016). Does consideration of environmental, social and governance issues by institutional investors influence social responsible investment decisions in South Africa? Journal of Accounting and Management, 6(2), 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ozili, P. K. (2022). Green finance research around the world: A review of literature. International Journal of Green Economics, 16(1), 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D. K., Kumar, R., & Kumari, V. (2023). Glasgow climate pact and the global clean energy index constituent stocks. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 19(10), 2907–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, R. (2021). ESG and its implications for the nexus of business, society and regulatory legislation in South Africa (p. 5). KPMG. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/za/pdf/2021/esg-the-context-of-south-africa.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastun, A., Makarenko, I., Kravchenko, O., Ovcharova, N., & Oleksich, Z. (2019). ESG disclosure regulation: In search of a relationship with the countries’ competitiveness. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17(3), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, L., Visser, M., & Giamporcaro, S. (2010). Responsible investment: A vehicle for environmentally sustainable economic growth in South Africa. SSRN Electronic Journal, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajgopal, S. (2022, April 21). ESG—A defense, a critique, and a way forward: An evidence-driven pragmatic perspective. Forbes. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ratner, S. R. (2001). Corporations and human rights: A theory of legal responsibility. The Yale Law Journal, 111, 443–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo Alamillos, R., & De Mariz, F. (2022). How can european regulation on ESG impact business globally? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(7), 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renström, T. I., Spataro, L., & Marsiliani, L. (2021). Can subsidies rather than pollution taxes break the trade-off between economic output and environmental protection? Energy Economics, 95, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M. H. (2021). Environmental, social and governance performance and financial risk: Moderating role of ESG controversies and board gender diversity. Resources Policy, 72, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, K., & Atkins, J. (2013, November 13–15). The ebbing hegemon? An evolutionary perspective on the emergence of holistic governance and the efficient role of institutional investors in environmental, social and governance issues (ESG). United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment-UNPRI Conference, Reading, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P. K., & Chudasama, H. (2021). Pathways for climate resilient development: Human well-being within a safe and just space in the 21st century. Global Environmental Change, 68, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamelos, C. (2023). Corporate sustainability and ESG factors in Greece and Cyprus: Compliance, laws and business practices, towards a holistic approach. InterEULawEast: Journal for the International and European Law, Economics and Market Integrations, 9(2), 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strine, L. E., Smith, K. M., & Steel, R. S. (2021). Caremark and ESG, perfect together: A practical approach to implementing an integrated, efficient, and effective caremark and EESG strategy. Iowa Law Review, 106, 1885–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Taplin, R. (2021). ESG and good corporate governance in relation to the use of pension funds: Comparison between the United Kingdom and South Africa (the report). Interdisciplinary Journal of Economics and Business Law, 10, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., Levac, D., Ng, C., Sharpe, J. P., Wilson, K., Kenny, M., Warren, R., Wilson, C., Stelfox, H. T., & Straus, S. E. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. (2016). Experience and lessons from South Africa. UNEP. [Google Scholar]

- Viviers, S. (2014). 21 years of responsible investing in South Africa: Key investment strategies and criteria. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 7(3), 737–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviers, S., Bosch, J. K., Smit, E. V. D. M., & Buijs, A. (2008). Is responsible investing ethical? South African Journal of Business Management, 39(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviers, S., & Els, G. (2017). Responsible investing in South Africa: Past, present and future. African Review of Economics and Finance, 9(1), 122–155. [Google Scholar]

- Viviers, S., & Mans-Kemp, N. (2021). Successful private investor activism in an emerging market. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(1), 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviers, S., & Smit, E. V. (2015). Institutional proxy voting in South Africa: Process, outcomes and impact. South African Journal of Business Management, 46(4), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Sun, Z. (2022). Does the environmental regulation intensity and ESG performance have a substitution effect on the impact of enterprise green innovation: Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. A., & Nagy, D. M. (2021). ESG and climate change blind spots: Turning the corner on SEC disclosure. Texas Law Review, 99, 1453. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington-Smith, M. D., & Giamporcaro, S. (2021). ESG materiality: Insights from the South African investment industry. In I. Y. Gok (Ed.), Advances in finance, accounting, and economics (pp. 217–240). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X., Li, Z., Xu, J., & Shang, L. (2022). ESG disclosure and corporate financial irregularities—Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 332, 129992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainullin, S., & Zainullina, O. (2021). Scientific review digitalization of corporate culture as a factor influencing ESG investment in the energy sector. International Review, 1–2, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article Title | Authors | Methodology | Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsible investing in South Africa: past, present, and future | Viviers and Els (2017) | Document analysis | Government, investors |

| Key challenges facing the socially responsible investment (SRI) sector in South Africa | Herringer et al. (2009) | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | Investors |

| Does consideration of environmental, social, and governance issues by institutional investors influence socially responsible investment decisions in South Africa? | Ogbuka and Fakoya (2016) | Qualitative content analysis | Investors |

| An index to measure the integrity of investment companies investing responsibility | Andrew (2020) | Triangulation | Government, regulators, investors |

| Persistence in ESG and conventional stock market indices | Caporale et al. (2022) | Rescaled range analysis and fractional integration techniques | Investors |

| Sustainable finance practices in South African retirement funds | IFC (2020) | Survey | Investors |

| Environmental, social, governance (ESG) and its implications for medium-sized enterprises in Africa | ILO (2022) | Training guide | Government |

| ESG materiality insights from the South African investment industry | Worthington-Smith and Giamporcaro (2021) | Survey | Investors |

| South African banks’ footprint in SADC mining projects: environmental, social, and governance principles | Milazi (2016) | Content analysis | Government, regulators |

| Reflecting on the changing landscape of shareholder activism in South Africa | Mans-Kemp and Van Zyl (2021) | Semi-structured interviews | Investors |

| Encouraging sustainable investment in South Africa: CRISA and beyond | Locke (2023) | Historical narrative and analysis | Regulators |

| Sustainability reporting patterns of companies listed on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange | Maubane et al. (2014) | Content analysis | Regulators |

| The state of responsible investment in South Africa | Jongh et al. (2007) | Survey | Investors |

| The evolution and alignment of institutional shareholder engagement through the King and CRISA reports | Foster (2020) | Historical narrative and analysis | Government, investors |

| Assessing the business case for environmental, social, and corporate governance practices in South Africa | Johnson et al. (2019) | Quantitative analysis | Investors |

| ESG and good corporate governance in relation to the use of pension funds: comparison between the United Kingdom and South Africa (the report) | Taplin (2021) | Library-based research | Investors |

| Corporate social responsibility and artisanal mining: towards a fresh South African perspective | Bester and Groenewald (2021) | Survey | Government |

| Successful private investor activism in an emerging market | Viviers and Mans-Kemp (2021) | Binary logistic regression | Investors |

| Institutional proxy voting in South Africa: process, outcomes, and impact | Viviers and Smit (2015) | Content analysis and interviews | Investors |

| The ebbing hegemon? An evolutionary perspective on the emergence of holistic governance and the efficient role of institutional investors in environmental, social, and governance issues (ESG) | Sharif and Atkins (2013) | Library-based research | Investors |

| SRI in South Africa: a melting pot of local and global influences | Giamporcaro and Viviers (2014) | Content analysis | Government, regulators, investors |

| Sustainable and responsible investment in emerging markets: integrating environmental risks in the South African investment industry | Giamporcaro (2011) | Empirical qualitative survey | Government, investors |

| Responsible investment: a vehicle for environmentally sustainable economic growth in South Africa | Pretorius et al. (2010) | Desktop research and interviews | Regulators, investors |

| 21 years of responsible investing in South Africa: key investment strategies and criteria | Viviers (2014) | Content analysis and semi-structured questionnaires | Government, investors |

| ESG investing and public pensions: an update | Aubry et al. (2020) | Library-based research | Investors |

| Regulating non-financial reporting: evidence from European firms’ environmental, social, and governance disclosures and earnings risk | Arif et al. (2022) | Propensity score matching technique | Government |

| ESG disclosure in comparative perspective: optimising private ordering in public reporting | Ho and Park (2019) | Comparative analysis | Regulators, investors |

| Financing a sustainable economy | National Treasury (2021) | Survey and questionnaires | Government, regulators |

| Mainstreaming environmental, social, and governance integration in investment practices in South Africa | Marais et al. (2022) | Questionnaires and semi-structured interviews | Investors |

| The emerging importance of the TCFD framework for South African companies and investors | Burival (2021) | Survey | Regulators, investors |

| Experience and lessons from South Africa: an initial review | UNEP (2016) | Scoping review | Government, investors |

| Public pension funds and socially responsible investment in South Africa: a case study of the Public Investment Corporation | Luvhengo (2013) | Case study approach | Government |

| Is responsible investing ethical? | Viviers et al. (2008) | Content analysis | Investors |

| An analysis of trends in shareholder activism in South Africa | Cassim (2022) | Content analysis | Regulators |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chawarura, W.I.; Sibanda, M.; Mamvura, K. An Assessment of the Roles of the Government, Regulators, and Investors in ESG Implementation in South Africa: A Scoping Review. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060220

Chawarura WI, Sibanda M, Mamvura K. An Assessment of the Roles of the Government, Regulators, and Investors in ESG Implementation in South Africa: A Scoping Review. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060220

Chicago/Turabian StyleChawarura, Wilfreda Indira, Mabutho Sibanda, and Kuziva Mamvura. 2025. "An Assessment of the Roles of the Government, Regulators, and Investors in ESG Implementation in South Africa: A Scoping Review" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060220

APA StyleChawarura, W. I., Sibanda, M., & Mamvura, K. (2025). An Assessment of the Roles of the Government, Regulators, and Investors in ESG Implementation in South Africa: A Scoping Review. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060220