Abstract

In order to mitigate the risks of losing key personnel and their innate tacit knowledge resources, this paper explored a framework for reducing knowledge loss in South African public sector enterprises (PSEs) through the integration of knowledge management (KM) and human resource management (HRM) strategies. The study used a quantitative research design, administering survey questionnaires to 585 randomly selected employees in three South African PSEs. The survey yielded a 25% response rate and was analysed using Statistical Analysis Software, resulting in a Cronbach alpha of 0.94. The findings of the exploratory factor analysis showed that a framework for reducing knowledge loss can be developed by integrating HRM practices and focusing on seven factors: knowledge loss recognition, knowledge management practices, human resource training, organisational culture, recruitment practices, employee retention, and organisational barriers. Three important components constitute the developed framework for knowledge loss minimization. Tacit knowledge loss was recognised as a critical strategic issue based on the results of the chi-square test for independence and logistic regression. This realisation, along with control and intervention variables, created the three main components of the framework. This paper explored the Knowledge Loss Reduction framework, focusing on South African PSEs as a case, to help organisations address the complex tacit knowledge loss prevalent in public and commercial firms worldwide. It contributes to the knowledge-based view, focusing on knowledge-absorptive and -retentive capacities and praxis in knowledge (risk) management and human resource management.

1. Introduction

Success in running knowledge-intensive business enterprises such as public sector enterprises (PSEs) in the modern knowledge-driven competitive environment and economy is greatly dependent on the efficient management, protection, and retention of firm-specific tangible and intangible resources. Globally, PSEs are crucial for national economies and are found in industries like energy generation and distribution, public water utilities, mining, aviation, rail, research and development, and banking. They are seen as the foundation of a knowledge-based economy and competitiveness, having a significant impact on the global economy (Benassi & Landoni, 2019; Saxen & Das, 2022). The South African Government sees PSEs as essential tools for expanding the economy, promoting public infrastructure investments, generating employment, and creating a conducive business environment (Gumede, 2018). However, a number of these businesses struggle constantly with the phenomenon of organisational tacit knowledge loss, which is exacerbated by an increased human resources mobility, a lack of knowledge management (KM) practices, knowledge-driven human resource management practices (HRMPs), knowledge-driven organisational culture and structures, and organisational barriers or factors (Phaladi, 2024a; Azaki & Rivett, 2022). In South Africa, several scholars have highlighted the serious implications of the risks associated with high turnover, an ageing workforce, and a lack of human resource retention strategies leading to immense tacit knowledge loss, which threaten the capability of PSEs to deliver on their developmental mandate (Azaki & Rivett, 2022; Okharedia, 2019; Phaladi, 2023). Knowledge loss poses various risks, namely a loss of competitiveness and innovation capability; reduced social capital; and decreased organisational learning, organisational effectiveness, and sustainability (Durst et al., 2023; Durst & Zieba, 2020; Massingham, 2018; Brătianu, 2018).

Increased human resources mobility in global knowledge-based competition complicates the management of intangible knowledge-assets, resulting in increased risks emanating from the loss of tacit knowledge in public and commercial enterprises around the globe (Serenko, 2023; Allen & Vardaman, 2021). Such developments have heightened the need to accelerate, invest in, and leverage the smooth management of knowledge-based assets, which are seen as sources and means of wealth creation and capture by private enterprises operating in environments of rapid technological revolution (Boisot, 1999). The competitiveness of enterprises is greatly dependent on the investment of distinctive management processes aimed at safeguarding the firm-specific collection of difficult-to-trade intangible knowledge assets (Teece et al., 1997). However, PSEs across the globe are being lamented and flagged for lacking the management investment capability to effectively mitigate the risks inherent in intangible (tacit) knowledge assets such as the competencies, expertise, and skillsets of their most valuable human resources (Souto & Bruno-Faria, 2022; Saxen & Das, 2022; Kumar, 2020). Knowledge loss risk has been the subject of intense research over the last decade. Scholars indicate that it affects several public enterprises in various sectors of the economy, such as nuclear companies; energy and power generation; water; developmental banking institutions; and the mining and manufacturing sectors (Zieba et al., 2022; Sumbal et al., 2021; IAEA, 2017; Okharedia, 2019; Vlasov & Panikarova, 2015).

Extant research posits that the discipline and practice of human resource management (HRM) have a crucial role to play in the mitigation and management of firm-specific tacit knowledge in order for public enterprises to avoid and mitigate against knowledge loss risks and the adverse consequences thereof (Phaladi et al., 2024; Shujahat et al., 2020). Gürlek (2020) averred that the efficient management of organisational knowledge to avoid its loss and associated risks is contingent upon human resources and the management thereof within public and private companies. Phaladi and Ngulube (2024) agreed with Gürlek (2020) that workers within state enterprises are carriers (sources) of much organisational tacit knowledge. These human resources apply their much-needed knowledge, competencies, and skillsets to produce goods and services to ensure that PSEs contribute to the economic developmental agenda of the country and assist the government in addressing socio-economic challenges and positioning the country in the global economy (Gumede, 2018; Phaladi & Ngulube, 2022). However, they face the significant risks of tacit knowledge loss and high rates of attrition in their human resources (Souto & Bruno-Faria, 2022).

From an academic and practical standpoint, this study is extremely pertinent, particularly in the light of PSEs’ inadequate retention policies, ageing workforces, and rising workforce mobility in the knowledge-based competitive economy. This study aims to contribute to the knowledge management and HRM literature by addressing organisational knowledge loss and reducing gaps in the literature. While research on knowledge loss, skills shortages, turnover, and knowledge transfer challenges has been conducted independently, many scholars have overlooked the importance of human resource management in ensuring the effective management of such knowledge loss risks (Gope et al., 2018; Zaim et al., 2018). Practical HRM components like talent recruitment, training, succession planning, and reward management systems play a crucial role in knowledge transfer and retention, as well as in building desired knowledge-oriented behaviours and practices. Public enterprises in South Africa are grappling with issues like ageing technical employees, skills shortages, and brain drain, primarily from a skill and HRM perspective (Phaladi, 2021). Tacit knowledge loss is a concern not just for knowledge management but also for HRM, highlighting its critical role in knowledge transfer and retention. This paper is an empirical study on the knowledge loss reduction framework, which proffers control factors and intervention factors for organisations to effectively tackle the perplexing tacit knowledge loss besieging many private and public enterprises around the globe, using South African PSEs as a case to develop such a framework in a particular context. No such research paper exists in the extant literature. Moreover, the study is interdisciplinary in approach and theoretically framed within the resource-based and knowledge-based theories of the enterprise, using South African public enterprises as a case to contribute to HRM and KM and focusing on knowledge loss risk management.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Relevant Theoretical Lenses

Using South African public enterprises as a case, the study is conceptually framed within the resource-based and knowledge-based theories of organisation in order to contribute to HRM and KM, particularly knowledge in terms of loss risk management. The resource-based theory (RBT) highlights human resource management practices as a long-term competitive advantage and productivity source (Barney, 2001; Wright et al., 2001), while the knowledge-based theory (KBT) highlights intangible assets like knowledge, skills, and competencies as drivers of enterprise competitiveness, innovation, and sustainability that require protection, particularly in public businesses (Takeuchi, 2013; Grant, 1996; Boisot, 1999). Public sector enterprises, often known as state-owned enterprises (SOEs), are seen as systems that generate knowledge, utilise substantial resources, and explore knowledge (Phaladi et al., 2024; Benassi & Landoni, 2019). The preceding theoretical reflection implies that employees (human resources) within PSEs are carriers and sources of intangible assets such as tacit knowledge, expertise, and the skillsets required to execute business strategies and operations. It is for this reason that several scholars call for firms to invest in the necessary organisational capabilities to absorb and protect enterprise-specific knowledge. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) and Andersén (2012) introduced two key theories, namely knowledge absorptive and protective capacities, which enhance the main KBT theoretical logic in research and firms. Absorptive capacity denotes the capability to recognise, obtain, modify, and employ external information (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). According to Andersén (2012, p. 440), “protective capacity” refers to a company’s ability to maintain or slow the rate at which organisational intangible resources, such as knowledge, talents, and skills, depreciate or are lost by keeping such knowledge assets hidden from rivals. However, according to existing research, PSEs are at serious risk of knowledge loss because of voluntary or involuntary human resource turnover (Phaladi & Ngulube, 2024; Kumar, 2020; Azaki & Rivett, 2022). Massingham (2018) inferred that an organisation’s output, productivity, organisational memory, social capital, learning, and external information flow can all be adversely affected by the tacit knowledge lost when employees leave. Such complexities of firm tacit knowledge loss significantly impact the knowledge-based theory and related research, theories, and praxis.

2.2. Review of the Literature

2.2.1. Knowledge Management Practises (KMPs)

The knowledge-based theory urges companies to prioritise investment in managing organisational intangibles to enhance their performance, competitive edge, productivity, and innovation (Grant, 1996). The knowledge-based view emphasises the importance of safeguarding organisational tacit knowledge assets through the implementation of effective knowledge management practices. Knowledge management practices are firm-specific processes that enhance knowledge-absorptive and -protective capacities (Phaladi & Ngulube, 2022; Andersén, 2012; Gürlek, 2020). Zaim et al. (2018) suggested that knowledge management practices should encompass strategies for knowledge generation, discovery, use, sharing, and protection within business enterprises. Research shows that KMPs significantly impact organisational performance (Dalkir, 2023; Kianto et al., 2017) as they foster a knowledge-driven culture, behaviours, processes, and innovation within organisations. Furthermore, KMPs guide and shape a desired knowledge-driven culture inclusive of activities and behaviours, thereby enhancing organisational performance. However, research shows that large business enterprises such as PSEs around the world are lagging in key KMPs (Souto & Bruno-Faria, 2022; Kumar, 2020; Sandelin et al., 2019). Recent research emerging from South African PSEs has lamented that they are also lagging behind in key knowledge-driven practices, culture, and leadership, largely because KM is underdeveloped in many such public enterprises (Phaladi, 2024a; Phaladi & Marutha, 2023; Azaki & Rivett, 2022). Knowledge management (KM) is crucial for success in the global knowledge economy and, ideally, PSEs must invest in appropriate KM capacity to develop effective knowledge management practices. According to Gope et al. (2018, p. 650), KMPs offer a crucial organisational framework and basis for increasing KM capabilities in businesses. Procedures and tactics targeted at creating, using, and safeguarding firm-specific knowledge resources should be part of these processes. Phaladi and Ngulube (2022, p. 3) observe that businesses spend money on acquiring knowledge resources in order to outperform their rivals and gain a competitive edge. However, they will never be able to maintain their performance unless they make investments in knowledge-driven procedures for the management and safeguarding of these knowledge assets.

2.2.2. Human Resource Management Practices (HRMPs)

According to the RBT put forward by Barney (2001), knowledge-oriented HRMPs are believed to have a major impact on an organisation’s competitiveness, innovation, and sustainability (Sarfraz et al., 2023; Hussinki et al., 2017). The importance of HRM in managing or mitigating tacit knowledge loss risks cannot be overstated. In order to prevent possible loss risks and harm to organisations like PSEs, HRM plays a crucial role in tacit knowledge management. To prevent the loss of organisational tacit knowledge, several conceptual papers and a small number of empirical investigations suggest that HRMPs or systems are crucial (Le, 2024; Sarfraz et al., 2023). According to the conceptual paper by El-Farr and Hosseingholizadeh (2019), aligning HRMPs with KM is crucial for enhancing business performance. The acquisition, application, development, sharing, and retention of important business knowledge may be facilitated directly or indirectly by traditional HRMPs like hiring and selection, learning and development, compensation and rewards systems, organisational design, performance management, and retention systems (Kianto et al., 2017). Knowledge acquisition and absorptive ability are directly linked to HRM recruiting practices through the identification and sourcing of knowledge workers with the necessary knowledge, competences, and skillsets (Phaladi, 2023). However, according to Phaladi (2023), South African PSEs are always struggling to source mission-critical knowledge workers and replenish or protect their intangible knowledge assets, which are mostly lost as a result of excessive staff turnover. Serenko (2023), Allen and Vardaman (2021), and Sokolov and Zavyalova (2020) agreed that finding, sourcing, and keeping human resources with these qualities is the biggest risk facing HRM departments in businesses. Training and development initiatives are crucial for companies to retain human capital assets as they build motivation and commitment (Delery & Roumpi, 2017). These practices are known as knowledge-driven because they nurture a knowledge-oriented culture, knowledge management, and innovation capability in companies, thereby contributing to the overall success of the firm. Compensation and rewards practices in companies can impact the cost and results of knowledge management processes either positively or negatively, either facilitating or hindering the development of a KM culture (Shafagatova & Van Looy, 2021). The global knowledge economy is experiencing a talent war, making the retention of talent and knowledge workers a complex issue for many organisations. Ideally, public sector enterprises in knowledge-based economic competition should invest in identifying, recruiting, and developing knowledge workers globally. However, retention and tacit knowledge loss remain significant challenges in strategic management and public sector organisations (Galan, 2023; Durst et al., 2020). Public sector enterprises face mobility issues, an ageing workforce, and a lack of retention practices. Despite these challenges, they remain critical drivers of economic growth and GDP in both developed and developing economies (Bahl et al., 2019). Although several scholars have recently made general claims about the importance of HRMPs in knowledge management, none of the studies have examined the critical role that HRMPs may play in actually reducing the risks of knowledge loss, especially in PSEs. The current study emphasises the importance of protective capacity in HRM, as the previous literature has primarily focused on knowledge worker retention, overlooking the crucial role of human resources in effective management and knowledge reduction.

2.2.3. Knowledge Loss Risk Management

Knowledge risk management (KRM), particularly knowledge loss risk management, is a new research area that significantly improves organisational performance by enhancing innovation, agility, success, sustainability, and growth. KRM involves identifying, analysing, and responding to risks related to the creation, application, and retention of organisational knowledge (Durst et al., 2019). It equips business leaders, managers, and decision-makers with strategies to predict and respond to knowledge-related risk incidents (Souto & Bruno-Faria, 2022). According to Durst et al. (2023), knowledge risk assessment is crucial for managing private and public enterprises as it assesses the likelihood and potential impact of knowledge failure, and strategic responses can enhance their resilience. The focus of this study is on a specific type of knowledge risk, namely that knowledge loss is complex, involving factors like employee turnover; an ageing labour force; unexpected deaths; accidents; and retirement, which can negatively impact organisational performance and sustainability (Durst et al., 2023; El Khatib & Ali, 2022; Hill, 2020). According to Phaladi (2024b) and Kumar (2020), PSEs are especially impacted by knowledge loss brought on by problems with human resource mobility since they are knowledge-intensive, knowledge-generating, and learning organisations. A comprehensive, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to knowledge loss risk management has not been provided in the existing literature, which has primarily examined knowledge loss concerns from a knowledge management (KM) perspective. In general, there are currently very few scholarly tracts on knowledge (loss) risk management, and even fewer empirical investigations exist (Durst et al., 2023; Zieba et al., 2022). Moreover, there is a dearth of conceptual and empirical studies identifying the relevance of strategic HRM policies in managing the risks associated with organisational knowledge loss. First and foremost, whenever an organisation has personnel turnover, human knowledge is most at risk (Phaladi et al., 2024; Phaladi, 2023). By employing an interdisciplinary approach to empirically examine the role of HRMPs and KMPs in knowledge loss risk management, the study aims to close this gap and create a framework for public enterprises to mitigate knowledge loss.

2.2.4. Organisational Barriers, Culture, and Structures

The management of organisational tacit knowledge is significantly influenced by the culture and structure of the organisation (Dalkir, 2023; Gürlek, 2020), which helps in reducing associated risks. Resource-based view theorists (Barney et al., 2001) argue that institutional culture is a company-specific resource that gives companies a competitive edge in the knowledge-based economy. Organisational culture, based on values and beliefs, influences behaviours and initiatives and can either positively or negatively impact knowledge exchange and retention (Phaladi, 2024b; Matoškova & Smĕšna, 2017). Aligned to knowledge-based theory logic, Gurlek and Tuna (2018) suggested that a knowledge-oriented organisational culture can give a firm a competitive edge by making it difficult for rivals to replicate its strategies and innovation initiatives. A knowledge-driven organisational culture is one that is unique to a certain enterprise and helps permit or encourage the exchange of information in order to reduce the risk of losing it. According to Gürlek (2020), a company’s culture shapes the social interaction setting that determines how knowledge is created, shared, and used in certain situations. By the same token, an organisation’s structural composition may have a beneficial or injurious impact on the creation, sharing, use, and retention of knowledge, depending on how it is structured (Ayatollah & Zeraatkar, 2019). Phaladi (2024b) bemoaned HRM departments’ inability to support knowledge-centric structural configurations and noted that PSEs are falling behind in essential responsibilities and structures to assist the reduction in knowledge loss vulnerabilities. Studies have also identified additional institutional factors or barriers that impede the facilitation of knowledge loss risk management behaviours within the cultural context of organisations, including silo mentalities, red tape, a lack of trust, knowledge hoarding, and a lack of knowledge-driven incentives, recognition, and leadership (Rutten et al., 2016; Phaladi, 2024a). These organisational factors and barriers contribute to knowledge stickiness in companies (Szulanski, 1995). Competitors or the outside world will find it more difficult to obtain knowledge that has become stickier. Absorptive capacity, or the absence of it, can lead to knowledge stickiness within organisations and hinder its transfer (Szulanski, 1995; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

3. Methodology

Philosophically grounded in positivism, the study used a quantitative research design, administering survey questionnaires to 585 randomly selected employees in three South African public sector enterprises (PSEs) that operate in the water, developmental finance, and compliance and regulatory sectors. Survey participation was requested from nine PSEs operating in South Africa’s five economic sectors, including the water industry, developmental banking institutions, service public sector firms, regulatory sector, and research and development sector. However, of the nine PSEs, only three granted permissions to participate in the quantitative portion. These SOEs received the online survey questionnaire between August 2020 and November 2020 when the country was under coronavirus lockdown laws, rendering the researcher with limited opportunities to do follow-ups or increase the response rate.

Quantitative information was gathered from workers at the chosen PSEs using probability sampling (Straits & Singleton, 2018). With the help of human resource managers, the survey instrument was dispersed at random to workers in three PSEs with internet and email access. By using questionnaires, researchers may gather quantitative data and analyse it quantitatively using measurements and statistics (Straits & Singleton, 2018). In order to assure ethical concerns, the researcher obtained informed consent, kept confidentiality and anonymity, and used the survey questionnaire in a subset of PSEs. As shown in Appendix B, questions based on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree were employed. The survey yielded a 25% (145) response rate from the targeted 585 respondents and was analysed using Statistical Analysis Software, resulting in a Cronbach alpha of 0.94. According to Hair et al. (2014), one statistical method to model the interrelationships between variables is exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The goal of this study was to identify the variables that may be included in a framework to lessen knowledge loss. Therefore, EFA was employed to eliminate redundant questions or variables from the survey instrument and focus on significant variables for the study and framework development. A response rate of 145 respondents (25%) was deemed adequate for EFA. Determining the coefficient between variables and factors in the instrument was the goal of applying EFA to the quantitative data collected through the survey instrument. Research indicates that for EFA investigations, a response rate of at least 120 respondents is sufficient to determine the correlation co-efficiency between the variables and factors (Hair et al., 2014). This paper was taken from a larger PhD project that aimed to create a model for mitigating knowledge loss in South African PSEs by incorporating HRMPs and KMPs, including organisational culture, structures, and barriers or factors (Phaladi, 2021). SAS version 8.4, EFA, chi-square, and logistic regression were used to identify key components in order to build a model on knowledge loss mitigation for the primary research.

4. Results

Three components comprise the quantitative analysis. The first is the examination and display of all variables’ responses and charts; the second is the outcome of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA); and the third is the use of logistic regression and chi-square analysis to determine which variables are important in the framework’s development.

4.1. Structural Detection

Data appropriateness for factor analysis was assessed using structural detection. To ascertain whether factor analysis may help reduce redundant data across variables, three tests were run. The first test, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, established whether a collective correlation is present. There are fifty-six variables in the data, which were first divided into six groups as follows:

- Appreciation or acknowledgement of tacit knowledge loss;

- Practices for knowledge management;

- HRM hiring/recruitment procedures;

- Human resource training and development procedures;

- Retention strategies for staff; and

- Culture within the organisation.

The Table 1 below shows a collective correlation between the 56 variables based on the p-value. The p-value suggests that there are no common causes at the 5% level of significance, rejecting the null hypothesis.

Table 1.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

This result suggests that reducing the 56 variables to a smaller number of components by factor analysis can be advantageous.

The second test is a correlation analysis applied to determine pairwise correlation between the variables. The results indicate the existence of significant relationships amongst the variables, as illustrated in Table 1 and Appendix A.

Kaiser’s Measure of Sample Adequacy (MSA) is the third test, whereby MSA values are categorised by Kaiser (1974) as either undesirable (below 50%) or magnificent (at least 90%). There is a requirement for structural identification as evidenced by the total MSA score of 82.5%, which is within the meritorious category. In this investigation, the partial correlation varied between 52.5% and 90.5%. A minimum MSA value of 50% is regarded as acceptable by Hair et al. (2006), provided that all 56 factors are considered in this analysis.

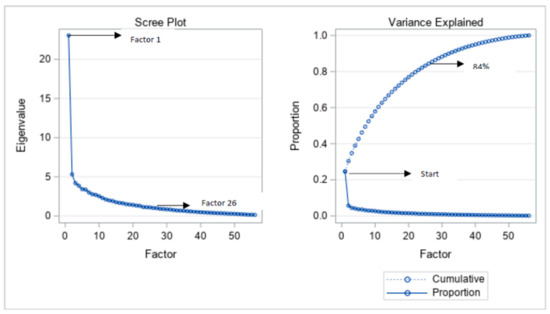

4.2. Determining the Number of Factors

The number of variables that can be utilised to create a framework for minimising organisational knowledge loss is determined in this section. The greatest number of components that may be correctly employed to construct a framework for decreasing organisational knowledge loss is determined by using the eigenvalue criteria. Factors with an eigenvalue greater than one are considered by the eigenvalue criteria. An eigenvalue indicates how much variation a factor accounts for. When this criterion is met, any factor with a variance greater than one is deemed significant. There are 26 factors with eigenvalues greater than one, according to Figure 1, Table 2, and Appendix A.

Figure 1.

The variance explained plot. Source(s): Author’s work.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients of factors and variables.

According to the variance explained plot, 84% of the variance in the framework for reducing organisational knowledge loss can be attributed to the 26 components.

4.3. Combining Similar Variables into Groups

The process of identifying important variables in each component is guided by the correlation that exists between the variables and the related factors, as illustrated in Table 2 below. Smaller sample numbers necessitate higher correlation coefficients, and vice versa. Variables in this study will be deemed significant if their correlation coefficients are 50% or higher. For a sample size of between 120 and 150, a correlation of 50% is deemed practically significant (Hair et al., 2014).

The contribution of a variable to a factor is taken into consideration in addition to the correlation between factors and variables. Factors with a single significant variable and those with less than 50% of the variation in each factor are deleted (as illustrated in Table 2). The Table 2 below lists the final elements and variables for the framework designed to lessen organisational knowledge loss.

The logistic regression and chi-square analyses will use the seven factors listed in the preceding table. Factor 12 pertains to the recognition of knowledge loss and will be used to derive responses for a dependent variable. The variable with a larger correlation with the factor will be the surrogate variable. The other factors will be independent variables in the chi-square and logistic regression. As with the dependent variable, the surrogate variable will be the one with a larger correlation with the factor.

For a knowledge loss mitigation framework, knowledge management practices and HRMPs are spread into seven factors, as illustrated in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Factors and corresponding labels.

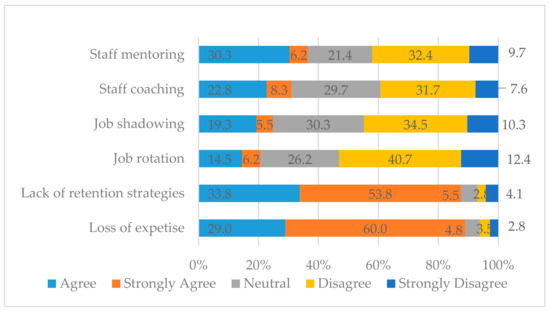

The chart below (Figure 2) presents the share of each variable on the response categories for knowledge management practices, beginning with recognising knowledge loss as a strategic organisational problem. A significant 89% of respondents believe that knowledge loss is caused by a loss of expertise and 88% by a lack of retention strategies. A small percentage (6–7%) believe that knowledge loss is not caused by these factors. KMPs such as job shadowing and job rotation remain problematic areas in PSEs, with 45–53% believing that their companies do not apply these practices as knowledge-driven practices. Moreover, 21–25% believe that they do, but 26–30% are less informed about the issue. Furthermore, most respondents (39–42%) find staff coaching and mentoring as KMPs problematic, while 21–30% are less informed about these practices. Overall, knowledge management practices need to address knowledge loss effectively.

Figure 2.

Summary of the responses for KMPs. Source(s): author’ own work.

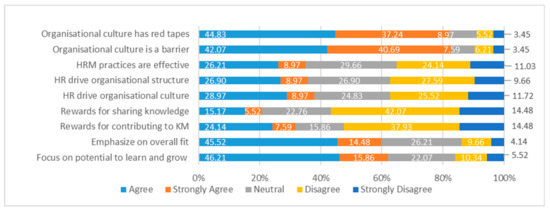

The chart above shows the share of each variable on the response categories for HRMPs in their PSEs, as illustrated in Figure 3. A majority of the respondents (more than 80%) believe that there are barriers in their organisations, which has a negative impact on knowledge management. More than half of the respondents indicated that their PSEs do not reward contributions to KM and knowledge sharing. The survey revealed that 35.18% of respondents believe that their HRM procedures effectively support knowledge management, while 35.17% believe that their PSEs’ HRM procedures are ineffective. The result suggests that PSEs are not employing knowledge-driven HRM methods to mitigate knowledge loss risks. In addition, 37.25% of respondents believe that their HRM units are not driving organisational structures supporting KMPs, while 35.87% believe that HRM is the driving force behind such structures. The study revealed diverse opinions on HRM’s role in promoting a knowledge-driven organisational culture, with 37.94% promoting a knowledge-centric culture and 37.24% indicating that it does not drive firm-specific knowledge-centric behaviours and culture. Most of the respondents stated that their PSEs fail to acknowledge and reward their contributions to KM and knowledge sharing. The statistical analysis of the research also included recruitment tactics as a crucial component. The analysis indicates that this variable likely played a significant role in facilitating the acquisition of the necessary competencies and abilities. The HRM selection process, according to 62.07% of respondents, prioritises an employee’s learning and growth capacity, while over 60% prioritise their overall fit within their organisation.

Figure 3.

Summary of the responses for HRMPs. Source(s): author’s work (2021).

Finding the elements that significantly contribute to a framework for minimising knowledge loss was achieved through a factor analysis. According to the findings, a framework for reducing knowledge loss may be created by concentrating on seven elements: corporate culture, recruiting procedures, organisational barriers, staff retention, training, KMPs, and knowledge loss awareness/recognition. These elements comprise human resource management and knowledge management practices. Therefore, in order to effectively reduce organisational knowledge loss, public sector enterprises are encouraged to invest in these elements.

4.4. Chi-Square and Logistic Regression

This test was used to ascertain whether a statistically significant relationship existed between the independent variables, as illustrated in Table 4 below. When a substantial association is found, it means that the factors may be combined to create a framework. These variables represent KM and HRM. The p-value is used to calculate the probability of the null hypothesis being true and two independent variables being statistically independent. A large p-value indicates a high probability of the two variables not being related, and a 5% level of significance is used.

Table 4.

Test for independence.

The above Table 4 presents p-values for testing the absence of correlations amongst the independent variables. All the p-values are smaller than the significance level of 5%, signifying a significant correlation amongst the independent variables.

This relationship indicates that the integration of HRMPs and KMPs can be effectively realised through these variables. Nevertheless, this information does not present guidance on how the framework can be assembled. The application of logistic regression provides more insight into the variables.

- Logistic regression

The purpose of logistic regression is to forecast the likelihood that an event will occur. In this research, it was used to model the response variable (knowledge loss) and the independent variables (organisational culture, human resource retention, recruitment procedures, human resource training, KM techniques, and organisational barriers). Odds ratios are applied to quantify the recognition or realisation of knowledge loss. The odds ratio is a measurement that enumerates the effect of exposure.

- Bivariate test for significant variables

The bivariate test establishes whether an independent variable significantly influences the dependent variable in a one-to-one ratio (the one-to-one connection does not take the effect of the other factors into consideration). Once more, the likelihood that an independent variable would not significantly affect the identification of knowledge loss is calculated, as illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bivariate test.

The p-values signify that a model that looks into the variables in isolation cannot be effective in lessening knowledge loss, with the exception of human resource retention practices. The p-value for staff retention practices is less than a 5% level of significance, implying that retention practices are effective without the other variables, which will consequently prevent knowledge loss. Since the variables cannot be studied in isolation, the predictive probabilities cannot be computed for this analysis. For this reason, odds ratios will be the only focus of the analysis.

The table below shows that PSEs with recruitment practices that facilitate or support KM activities appreciate knowledge loss twice as much compared to public enterprises with other recruitment practices that do not support KM. In addition, the appreciation of knowledge loss is almost three times for PSEs that have KMPs. These practices are considered control factors since they allow for the recognition or appreciation of enterprise knowledge loss, as illustrated in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Odds ratio.

On the other hand, the recognition of knowledge loss is less observed with the training of organisational members, human resource retention practices, organisational culture, and institutional barriers. These are intervention variables since the loss of applied knowledge is less appreciated currently.

Succinctly, there should be two stage control variables in the framework for mitigating knowledge loss.

The first step will occur during the recruitment phase. As a precautionary step, recruitment practices will be used throughout this time. The focus needs to be on overall fit, personality, norms, and values in order to identify and recognise factors that could lead to knowledge loss.

The second-stage control factor will focus on KMPs such as staff coaching and staff mentoring. In this phase, KMPs such as staff coaching, staff mentoring, etc., are implemented as a preventative measure. The focus should be on training and developing employees in a way that enables them to use what they have learned.

It should be mentioned that knowledge loss may still occur even in the event that the control elements are implemented successfully due to unanticipated events. Therefore, it is essential that state-owned businesses include intervention aspects in their framework for reducing knowledge loss.

5. Discussion

The study’s primary goal was to provide a framework for combining HRM and KM techniques to reduce knowledge loss. There is no holistic management intervention when knowledge loss risks are just studied and managed from the standpoint of knowledge management practice and discipline. In line with the knowledge-based view of the firm (Grant, 1996), knowledge loss risks can negatively impact the sustainability and performance of PSEs if these organisational vulnerabilities are not mitigated (Durst et al., 2023; El Khatib & Ali, 2022; Souto & Bruno-Faria, 2022). On a positive note, there is a realisation or recognition that knowledge loss is a significant strategic issue in PSEs that requires management intervention. The research findings revealed that knowledge loss is a significant organisational problem, with 89% of respondents identifying it as resulting from expertise loss and lack of retention strategies. However, a small percentage believe that this is not the case. Despite the strategic recognition of knowledge loss as a risk, HRMPs often fail to effectively mitigate such risks. Moreover, knowledge management practices like job shadowing and job rotation are still problematic, with 45–53% believing that their PSEs do not apply them effectively. Staff coaching and mentoring are also considered problematic in the selected PSEs. The survey revealed that knowledge loss in PSEs is primarily caused by inadequate retention initiatives, the retirement of an ageing workforce, and voluntary resignations. According to the survey, most public sector enterprises do not have specific KM roles, strategies, or structures in place. While KM was institutionalised in the organisational structures and cultures of a lesser percentage of state-owned businesses, many of their HRM procedures were not set up to work with knowledge management systems and initiatives. Furthermore, the survey found that several knowledge management strategies were lacking in the vast majority of public sector businesses (Phaladi & Ngulube, 2022). These included knowledge harvesting, succession planning, coaching and mentoring techniques, employment rotations, job shadowing, and plans for engaging retired knowledgeable workers.

The study indicates that public sector enterprises are not effectively utilising knowledge-driven HRM strategies to mitigate knowledge loss risks. Dalkir (2023) suggests that HRM procedures are essential in helping to facilitate and promote knowledge management. However, KM was found to be unsupported by HRMPs in most public enterprises. The majority of respondents believe their PSEs fail to acknowledge and reward their contributions to knowledge management. Whilst the lack of retention strategies was detrimentally affecting knowledge-protective capacity and knowledge management capacity, recruitment, training, and development practices were found to be knowledge-centric and positively contributing to knowledge absorptive capacity and knowledge creation capacity. Recruitment tactics are also a crucial component, with 62.07% of respondents prioritising an employee’s learning and growth capacity, and over 60% prioritising their overall fit within the organisation. Building organisational absorptive ability will be greatly aided by PSEs’ emphasis on learning and growth potential in their hiring procedures.

Knowledge stickiness was caused by a lack of other KM strategies, as well as a deficiency in knowledge-driven incentive and recognition systems (Phaladi, 2021). HRMPs can significantly influence and reinforce organisational values, norms, and behaviours towards a knowledge-driven culture (Dalkir, 2023; Gürlek, 2020), thus in the process helping to build organisational absorptive and protective capacity to manage knowledge risks. However, the study reveals varied views on HRM’s role in fostering a knowledge-driven organisational culture, with 37.94% promoting a knowledge-centric culture and 37.24% arguing that it does not drive firm-specific knowledge-centric behaviours. Organisational culture that is not knowledge-centric or friendly can lead or add to complexity in knowledge stickiness in certain PSEs, thus affecting knowledge sharing and increasing the risk of knowledge loss. Furthermore, PSEs are not effectively utilising knowledge-driven HRMPs to mitigate knowledge loss risks, with most respondents believing that HRM units are not driving organisational structures supporting KMPs. This finding confirms previous research that established that PSEs around the world are lagging behind in the key structures and roles supporting the management of knowledge and its associated risks (Azaki & Rivett, 2022; Kumar, 2020; Shujahat et al., 2020; Sandelin et al., 2019). Therefore, PSEs may enhance knowledge sharing, lower barriers to effective risk mitigation of knowledge loss, and increase their organisation’s capacity to assimilate and protect their intangible knowledge assets by investing in these knowledge-driven initiatives (Phaladi, 2024a).

The survey reveals that more than 80% of respondents believe that there are barriers in their organisations negatively impacting knowledge management. The study also showed that organisational silos and bureaucracy in state-owned businesses acted as roadblocks to efficient tacit knowledge loss management. Organisational culture is also a barrier to the effective management of knowledge loss risks in PSEs. The research confirms that the enterprise culture significantly influences the barriers and enablers to effectively manage knowledge loss risk (Iqbal et al., 2025; Phaladi, 2024a; Souto & Bruno-Faria, 2022).

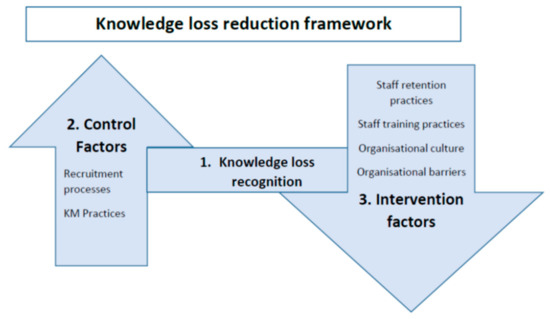

The goal of the suggested knowledge loss mitigation framework (as illustrated in Figure 4 below) is to assist public sector enterprises in integrating knowledge management and human resource management practices, but it is not meant to be a dictatorial structure.

Figure 4.

Framework for tacit knowledge loss mitigation. Source(s): author’s own work.

Three important components make up the developed framework for knowledge loss mitigation in public enterprises. Knowledge loss was recognised as a critical strategic issue based on the results of the chi-square for independence and logistic regression. This realisation, along with control and intervention variables, created the three main components of the framework, as discussed below.

- 1.

- Acknowledgement of knowledge loss as a key strategic concern

Only when PSEs see knowledge loss as a strategic concern can knowledge loss be reduced. Knowledge loss is a major organisational issue, and the framework for integrating knowledge management and human resource management techniques for the reduction in knowledge loss suggests that any integration attempt should start with the awareness of knowledge loss. Consequently, public sector businesses should prioritise investing in their organisational human resources and firm-specific knowledge, expertise, and skillsets in their business strategies as long-term sources of competitive edge and sustainability. The loss of institutional knowledge needs to be addressed as a major organisational problem in order for it to be managed probably. Once there is such a level of acknowledgement of tacit knowledge loss, the framework proposes that the control factors can be applied to control the loss of knowledge.

- 2.

- Control factors

The control factors amplify the recognition of the issues related to knowledge loss and are deployed to control it. In this instance, hiring procedures that prioritise a candidate’s overall personality, values, and social norms boost the likelihood of identifying knowledge loss by 2.2 times during the entrance stage. Stated differently, the findings showed that PSEs with recruiting procedures that facilitate knowledge management activities identify knowledge loss twice as frequently as those public enterprises with recruitment practices that do not support KM. Furthermore, PSEs with KMPs recognise that tacit knowledge loss is nearly three times more for publicly owned enterprises that do have KMPs in place. These are elements of control because they make it possible to identify knowledge loss. It should be mentioned that knowledge loss may still occur even in the event that the control elements are implemented successfully due to unanticipated events. Therefore, it is imperative that public sector businesses incorporate intervention considerations into their framework for reducing knowledge loss.

- 3.

- Intervention factors

Intervention factors are used to lessen knowledge loss when knowledge loss is realised or recognised and causes are under control. To prevent knowledge loss, it is necessary to identify, implement, and invest in staff retention strategies; staff training and development strategies; organisational culture; and eliminating organisational barriers as intervention variables. Public enterprises ought to allocate resources towards these intervention variables as a means of mitigating the loss of knowledge. The study found that retention policies are issues that need to be addressed. Knowledge-driven incentive and compensation schemes must be put in place if company-specific human and knowledge resources are to be retained. This will significantly improve the ability to safeguard knowledge and lessen its stickiness.

Public sector enterprises should continue investing in knowledge-driven HRM training and development practices and should present organisational members with opportunities to regularly renew their competencies, knowledge, and skills. Employee development and training is how new knowledge is developed, absorbed, and acquired. Therefore, in state-owned firms, training and development techniques enhance the capacity to absorb information and aid in the production of new knowledge.

Additionally, organisational culture in PSEs requires intervention. It is impossible to overstate the contribution that HRMPs provide to an organisational knowledge-driven culture. Organisational values, conventions, and behaviours toward a knowledge-driven culture within the organisation may be shaped, encouraged, and reinforced by human resource management methods. If organisational culture is in line with and motivates the necessary knowledge-related behaviours and efforts, it may offer a vital, non-physical infrastructure for efficient knowledge loss risk management.

Knowledge stickiness is impacted by organisational obstacles, which impede knowledge transfers within PSEs (Szulanski, 1995). Public sector firms should remove institutional hurdles or barriers linked to a silo mindset and red tape in order to address this at the intervention stage. Additionally, it is important to address any organisational hurdles that affect the efficient management and mitigation of knowledge loss.

Insofar as resource-based and knowledge-based theories of the firm are concerned, the research findings of this study confirm that enterprise tacit knowledge attrition issues are intrinsically linked to firm-specific human resources. PSEs will unavoidably lose sources of their competitive advantage, innovation capability, and sustainability as a result of employee voluntary and involuntary turnover, which remains the main trigger of the loss of tacit knowledge. As a result, they will be unable to fulfil their function in a developmental state and lose their economic power as key instruments for socio-economic development. Intangibles like knowledge assets are important production drivers in the knowledge economy, according to the firm’s RBT and KBT (Barney, 2001; Grant, 1996). Regarding knowledge-absorptive capacity, the research indicates that HRMPs, including hiring and training strategies, significantly contribute to knowledge-absorptive capacity by acquiring workers’ innate knowledge, skills, and abilities whilst also developing these intangible assets through capacity development programmes, despite their limitations. Similarly, many South African public sector businesses have undeveloped KMPs (Maphoto & Matlala, 2022), which limits their ability to absorb, share, assimilate, and retain both new and current knowledge assets. Furthermore, the absence of knowledge management practices indicates that PSEs are not adequately protecting themselves against the risks associated with firm-specific tacit knowledge loss (Phaladi & Ngulube, 2022). Insofar as knowledge stickiness theory is concerned, key barriers such as knowledge-unfriendly business cultures and structures, silos, red tape, and the absence of knowledge-driven rewards, recognition, and HRM strategies will continue to increase knowledge stickiness. Therefore, such increased levels of knowledge stickiness will make it difficult for tacit knowledge to flow easily across business units and between employees within PSEs. Pertaining to knowledge-protective capacity, PSEs are not able to develop the requisite capacities and capabilities for the protection of enterprise-specific knowledge assets due to a lack of knowledge-oriented HRMPs, such as succession planning, job rotation, shadowing, coaching, mentoring, compensation, and rewards.

6. Theoretical Implications

This study expands RBT, KBT, and other relevant theories such as knowledge absorption, protection, and stickiness by demonstrating how these theories apply specifically to the phenomenon of tacit knowledge loss, KM, and HRMPs in the context of PSEs in South Africa. Unlike previous research, this study, using an interdisciplinarity approach, examined the unique relationship between knowledge management, HRM, organisational culture, and barriers in an important economic sector facing knowledge loss risks and evolving regulatory demands. The theoretical contribution of this study lies in recognising tacit knowledge (loss) as a critical strategic issue (Grant, 1996) that requires an interdisciplinary strategy to address and maintain PSEs’ competitive advantage, sustainability, and economic relevance. According to this study, business executives and knowledge managers need to invest in and retain their employees as well as their intangible assets, like knowledge, skillsets, organisational culture, and leadership in order to successfully address the complex issues of tacit knowledge loss in PSEs. The study suggests a clear connection between RBT and KBT in handling the complex issues related to knowledge loss risks, since managing knowledge effectively to prevent its loss depends largely on managing organisational culture (intangible asset) and tangible assets such as human resources. Since controlling organisational culture (an intangible asset) and tangible assets like human resources are crucial for efficiently managing knowledge to prevent its loss (Galan, 2023; El Khatib & Ali, 2022), RBT and KBT are useful theoretical tools for resolving the complex challenges connected to knowledge loss risks (Durst et al., 2023; Massingham, 2018; Barney, 2001; Barney et al., 2001; Grant, 1996). By showing that enterprise intangible resources, such as HRMPs and organisational culture (Gürlek, 2020), can dynamically interact with knowledge management processes to improve the effective mitigation of knowledge loss risks and consequently enhance competitive advantage, this study challenges and extends RBT and KBT, which are primarily focused on tangible and intangible resources. Insofar as knowledge absorptive capacity theory is concerned, the study has proven that HRMPs such as recruitment, learning, and development play a positive role in the sourcing and development of the firm-specific human and intangible assets, knowledge sharing, and organisational absorptive capacity.

Iqbal et al. (2025) and Cohen and Levinthal (1990) concur that knowledge sharing plays a crucial role in fostering a positive organisational culture and enhancing absorptive capacity. Notwithstanding their drawbacks, these approaches are crucial in fostering the production and acquisition of knowledge, which increased PSEs’ capacity to absorb knowledge. However, the same cannot be said about the methods used to retain human resources in South African PSEs. Insofar as knowledge protective capacity theory (Andersén, 2012) is concerned, human resource retention procedures are not knowledge-driven, which means that they do not assist PSEs in developing the skills and capacities required to safeguard enterprise-specific knowledge assets. Furthermore, the study extends knowledge stickiness theory (Szulanski, 1995) by demonstrating that silo mindsets and red tape in organisations have a major impact on knowledge stickiness. Through the proposed knowledge loss reduction framework, this study suggests that businesses should remove these obstacles during interventions to ensure effective management and prevent knowledge loss.

7. Practical Implications

From a practical perspective, the findings and proposed framework of this study advocate for PSEs to adopt knowledge-driven HRM strategies that foster or promote an open, co-operative, implicit knowledge-sharing and learning-oriented organisational culture. Such a management approach should be triggered by PSEs recognising tacit knowledge loss as a critical strategic issue. In a nutshell, the journey towards the effective mitigation of tacit knowledge loss in knowledge-intensive organisations such as PSEs will not succeed until and unless these executives recognise it as a major strategic concern. Effective HRMPs and KMPs can help mitigate challenges like employee turnover and knowledge loss in public enterprises (Sarfraz et al., 2023; Shujahat et al., 2020; Kianto et al., 2017). By investing in these knowledge-driven activities, PSEs will be able to improve knowledge sharing; reduce obstacles to the effective risk mitigation of knowledge loss; and strengthen their organisation’s ability to absorb and safeguard their intangible knowledge assets (Phaladi, 2024a). For efficient management and a decrease in organisational knowledge loss, the study suggests that HRMPs be matched and incorporated into KM (Le, 2024; Phaladi, 2024b; Phaladi et al., 2024). To guarantee that knowledge management is completely institutionalised, HRM practitioners should also create and oversee plans to integrate a knowledge-centric organisational culture, structures, and procedures. In this sense, leaders at all organisational levels must be knowledge-oriented. In order to help PSEs integrate their HRM and KM processes and lessen the severe risks of losing vital, firm-specific people and knowledge resources, the research provides a baseline framework for knowledge loss mitigation.

8. Limitations and Future Research

The survey study took place in a limited number of public enterprises in the South African context. Therefore, its research findings may not be transferrable and generalisable to other PSEs outside the country. Similar research could be undertaken in other South African PSEs that were not part of the sample. The suggested framework provides educative support for KM practitioners, HRM executives, strategists, and policy developers to enhance their understanding of managing organisational knowledge assets and mitigating associated risks. The results are indicative of the significance of HRM’s role in the management and research on organisational knowledge loss risks. Future studies could be conducted in other different economic sector contexts to test the framework and validate the findings of the study. It may help for future studies to explore the research issues highlighted in the study from interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, and mixed-methods perspectives in order to generate a diverse, complementary, and comprehensive picture of the phenomenon. Although the original research findings may be applicable to other comparable PSEs in South Africa, they are not very generalisable to PSEs in other sectors that were not included in the sampled businesses. In many PSEs in South Africa, knowledge management and knowledge loss risk management are undeveloped practices. This context-specific South African situation makes it difficult to control tacit knowledge loss risks through HRM alignment and integration with KM. Additionally, it is possible that the findings would not apply to PSEs in other nations, especially in countries where KM is fully developed management practice. To improve the present research, discussion, policies, and practice on risk management for tacit knowledge loss, the survey tool utilised in this study might be further explored in PSEs and private firms in other nations that are faced with comparable issues of tacit knowledge loss. Future research in South Africa may also examine the proposed framework elements qualitatively to create a more complete picture, as the construction of the suggested framework mostly relied on statistical data.

9. Conclusions and Recommendations

According to the research findings, public sector enterprises should prioritise employee retention strategies to mitigate knowledge loss risks, with a focus on firm-specific human and knowledge resources as key strategic resources. This is in line with the resource-based and knowledge-based theories of the firm (Barney et al., 2001; Grant, 1996). The study also suggests that HRMPs should be more knowledge-centric to facilitate knowledge management and reduce knowledge loss. In relation to knowledge-absorptive capacity, the study concludes that knowledge-driven recruitment practices should be proactive in sourcing the necessary knowledge and skills, thereby increasing knowledge-absorptive capacity. Investments in capacity development opportunities with organisational intentions are also recommended to boost knowledge creation and absorptive capacity. Overall, the research concludes that recognising firm-specific human and knowledge resources as key strategic resources is crucial for effective retention strategies. The researcher suggests that PSEs should create employee retention strategies that enhance the retention of firm-specific knowledge resources, thus enhancing their knowledge-protective or -retentive capacity.

The researcher suggests that HRMPs are crucial in addressing the challenges in effective knowledge management in public enterprises. Moreover, HRMPs can shape and reinforce organisational values, norms, and behaviours towards a knowledge-driven culture. To assess the organisation’s readiness for embedding knowledge-related behaviours and cultures, HRM practitioners should conduct organisational culture assessments and employee engagement surveys. Moreover, HR managers should lead the process of conceptualising knowledge management functions, roles, and job profiles to address structural issues. The study suggests that knowledge-oriented leadership is crucial to address structural issues and cultural barriers within organisations. It also suggests that PSEs should start investing in knowledge management practices to minimise the risk of knowledge loss. The challenges highlighted threaten the performance and sustainability of public sector enterprises (Phaladi, 2024b; Phaladi & Ngulube, 2022) as they may not be able to deliver on their developmental mandate if firm-specific human and knowledge resources are not properly managed. In order to lessen the risks of losing vital employees and associated knowledge assets, a framework for integrating knowledge management and human resource management methods is advocated. Regarding knowledge stickiness theory, the study infers that silo mindsets and red tape in PSEs significantly influence knowledge stickiness, suggesting that firms should eliminate these barriers during interventions to ensure efficient management and mitigate knowledge loss. Researching and managing knowledge loss risks solely from the perspective of the KM discipline and practice lacks holistic management intervention.

9.1. Policy or Practical Recommendations Based on the Key Findings

9.1.1. Recognition of Knowledge Loss

The study revealed that organisational tacit knowledge loss is primarily due to employee turnover and inadequate retention strategies, negatively impacting the knowledge base and protective capacities of PSEs.

- I

- The study concludes and recommends that recognising knowledge as a crucial firm-specific strategic issue is the first step towards guaranteeing efficient knowledge transfer and retention of important enterprise knowledge.

- II

- Employees and their knowledge should be acknowledged and treated as sources of long-term competitive advantage.

- III

- To reduce the risks related to knowledge loss, PSEs must give top priority to the development of personnel retention plans as well as knowledge transfer and retention plans.

9.1.2. Talent Recruitment Strategies (Control Factor)

For PSEs that participated in the survey, hiring new staff to replace departing personnel has proven to be expensive. HRM executives must address this by paying their most valuable and deserving workers fairly. Employees tend to stay longer and contribute a significant amount of their valuable knowledge and experience to the system when they are paid competitive market-related compensation. Some of the strategies proposed include the following;

- I

- A competitive recruitment strategy should incorporate attractive benefits and perks to ensure employee satisfaction, engagement, and overall well-being.

- II

- Communicating a competitive recruitment system to potential candidates will highlight the company’s value of their knowledge and skills, thus fostering confidence and integrity within the system.

- III

- Branding PSEs as learning- and knowledge-based organisations will certainly ensure that HRM practitioners attract potential candidates, creating a positive impression of a company that values learning and growth.

- IV

- Most PSEs lack the articulation of knowledge management and behavioural competencies in talent acquisition, which should be prioritised alongside KM attributes.

- V

- Talent recruitment practices should emphasise KM traits like knowledge sharing, teamwork, creativity and innovation attitudes, a learning and development attitude and culture, coaching, mentoring, networking, and collaborative behaviours amongst potential candidates.

- VI

- Promoting existing staff with knowledge-oriented behaviours in recruitment practice will enhance the employee value proposition, foster a sense of value, and contribute to the PSEs’ success.

9.1.3. Knowledge Management Practices (Control Factor)

The study’s conclusions made it abundantly evident that PSEs must make investments in procedures or plans meant to lessen knowledge loss and strengthen knowledge management skills. Such procedures should include, but are not limited to, the following;

- I

- Knowledge management techniques should serve as crucial control variables for the efficient management of institutional knowledge loss in order to address the issues of staff turnover and the resultant knowledge loss, as was mentioned in the previous sections.

- II

- Knowledge managers working in partnership with HRM practitioners should be involved in conducting knowledge loss audits to identify potential knowledge risk areas and devise strategies to mitigate these identified risks.

- III

- Create programmes for knowledge workers who are retiring to guarantee that their skills, knowledge, and experience are shared and preserved.

- IV

- Establish expert forums wherein experienced and retiring professionals are urged to spearhead information exchange initiatives within their areas of expertise.

- V

- Implement worker job rotation so they may experience a variety of company procedures. This will guarantee the dissemination, grounding, and integration of tacit knowledge throughout business process units.

- VI

- Knowledge harvesting must be included into PSEs’ fundamental business operations.

- VII

- To guarantee efficient knowledge transfer and retention, knowledge management practitioners in PSEs must create and support communities of practice in areas of core expertise.

- VIII

- PSEs should invest in suitable information and communication technologies and tools to enhance collaboration and KM processes.

- IX

- Working with HRM executives or departments, KM practitioners should conduct exit interviews to identify potential knowledge gaps and develop strategies to address them.

9.1.4. Human Resource Retention Strategies (Intervention Factor)

The study suggests that PSEs should prioritise the development of employee retention strategies to mitigate the risks of enterprise-specific tacit knowledge loss as follows:

- I

- Business and HRM executives in PSEs should create a highly committed cohort of knowledge workers, especially in core competence areas to avoid adverse impacts on their developmental agenda.

- II

- The researcher emphasises the need for PSEs to implement effective staff retention strategies to mitigate the negative impact of employees leaving public sector enterprises.

- III

- They should subscribe to the resource-based view in their strategic orientation and formulation, which should locate the importance of firm-specific workers in business strategies.

- IV

- In the same vein, HRM executives in PSEs should embed knowledge-based strategies in their planning in order to prioritise the retention of enterprise-specific knowledge assets as sources of sustainable competitive advantage. Such a strategic approach will naturally translate into systems, structures, and processes aimed at safeguarding their organisational intangible assets.

- V

- PSE companies should value, nurture, and keep employees engaged to prevent them from leaving or being enticed by competitors.

- VI

- HRM executives should drive the development and implementation of staff retention policies that will help facilitate tacit knowledge sharing through inter-generational knowledge transfer, job rotation and job shadowing, and succession planning.

- VII

- To deal with the risks of ageing and retiring experts, HRM and business executives in PSEs should ensure that post-retirement contracting includes knowledge transfer, coaching, and mentoring of the younger generations of workers.

- VIII

- Employees often seek better pay and benefits in the job market and HRM practitioners often complain about their public sector companies lacking market-related salaries and benefits. Therefore, PSEs should foster a positive enticing work culture by offering competitive pay and a healthy work–life balance.

- IX

- A knowledge-oriented compensation management regime is needed to acknowledge employees’ personal knowledge and skills, as voluntary turnover is primarily due to inadequate competitive remuneration strategies.

- X

- To mitigate this challenge, HRM practitioners should enhance their remuneration policies by offering counteroffers or salary increases to retain their mission-critical workers.

9.1.5. Talent Development Strategies (Intervention Factor)

The following training and development strategies are recommended for HRM executives:

- I

- HRM executives should devise knowledge-oriented training and development methods that provide staff members with chances to keep their knowledge and skillsets up to date.

- II

- HRM practitioners in PSEs should develop training and development practices that intentionally contribute to the acquisition, assimilation, and creation of new knowledge amongst employees.

- III

- HRM departments at PSEs should create policies to guarantee that training and development opportunities yield a return on investment.

- IV

- A return-on-investment approach might help HRM professionals prove the value of their training and development expenditure and their contribution to building organisational knowledge bases and skillsets.

- V

- HRM practitioners should integrate e-learning platforms and collaboration tools in retaining tacit knowledge.

- VI

- HRM executives should not just train for the sake of it, they should train to have an impact on their organisational knowledge base and knowledge management capacity.

9.1.6. Organisational Culture and Structures (Intervention Factor)

The study recommends that HRM practitioners in PSEs should address issues related to enterprise culture management, structures, and barriers, fostering knowledge-driven cultures, structures, and behaviours. This should include the following:

- I

- Practices in human resource management should be developed in such a way that they have the required power to mould, propel, and strengthen organisational norms, beliefs, and behaviours in the direction of a knowledge-driven culture.

- II

- HRMPs in PSEs should be designed in such a way that they help to shape, advance, and reinforce organisational norms, attitudes, and behaviours towards a knowledge-driven culture. For example, through incentivizing and rewarding employees for creating and sharing their knowledge, such knowledge-oriented HRM approaches will assist to cement a culture that is knowledge bent, thus in the process helping in building knowledge-absorptive and retention capacities.

- III

- PSEs, as learning and knowledge-based organisations, should promote and reinforce the desired behaviours to enhance knowledge management capacities and processes.

- IV

- HRM practitioners ought to be known for their practices in supporting knowledge production, application, sharing, and retention.

- V

- This can be accomplished in the following ways: (a) obtaining the necessary knowledge and skills about the science and praxis of KM; (b) providing job-specific and knowledge-based training and development interventions to employees; (c) promoting performance contracting on knowledge management; (d) conceptualising knowledge management in structures; and (e) putting in place knowledge-driven compensation and rewards systems. Such a comprehensive approach is more likely to result in positive, knowledge-centric PSEs, which will maximise the retention of tacit knowledge and in the process mitigate against inherent knowledge loss risks.

- VI

- HRM executives should play a significant role through staff involvement and the communication of their companies’ knowledge culture vision once the system, in its entirety or in its component pieces, is in place.

- VII

- HRM executives should ensure that their HRM initiatives are in line with the organisation’s knowledge management vision so that they are able to support knowledge-driven enterprise culture, behaviours, and practices. In that way, HRM executives will be serving as champions for knowledge management initiatives, behaviours, cultures, and processes.

- VIII

- To determine the level of preparedness for integrating the necessary knowledge-related behaviours and cultures, HRM departments should conduct employee engagement surveys and organisational culture evaluations. HRM departments might assist in guiding staff members towards the intended knowledge-centric organisational culture based on the findings of such evaluations.

9.1.7. Organisational Barriers (Intervention Factor)

To effectively mitigate knowledge loss risks in the PSEs, the following practices are recommended;

- I

- Institutional obstacles including the lack of knowledge-driven hiring, silos, red tape, recognition, and incentive programs must be removed.

- II

- The development and use of knowledge-driven reward and recognition systems, spearheaded by HRM departments, will help to solve this issue. The required knowledge management and associated risk management behaviours should be shaped and encouraged via rewards.

- III

- To guarantee that a knowledge risk culture is fostered from the very beginning of the hiring process, human resource managers should include knowledge management behavioural characteristics in their talent acquisition programmes.

- IV

- Knowledge-oriented leadership is essential for public sector organisations. Knowledge-oriented leadership should be mirrored and translated into actual organisational structures, processes, and strategies supporting knowledge management as the standard management practice to address knowledge loss minimization. To ensure that effective knowledge management strategies are used, knowledge-centric leadership should also assist in identifying and removing any organisational barriers.

- V

- To promote knowledge-driven behaviours and cultures and remove potential barriers to effective mitigation of knowledge loss risks, organisational culture intervention like entropy scores and culture surveys are essential. Therefore, HRM executives should be in a position to run such interventions.

Funding

The article is extracted from a doctoral project funded by grants from Tshwane University of Technology and the University of South Africa. The APC was funded by the Durban University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study followed the University of South Africa’s Department of Information Science Ethics Committee’s ethical guidelines, ethical clearance approval (References #: 2020-DIS-0018) before data collection to ensure compliance with institutional and international research ethics standards.

Informed Consent Statement

The study involved participants who were informed about the research objectives, procedures, risks and rights, and their right to withdraw without consequence, and their written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the University of South Africa’s ethical policies.

Data Availability Statement

This study’s data are accessible upon reasonable request but may be restricted due to ethical and confidentiality agreements to protect participant privacy.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses gratitude to public sector enterprises in South Africa that participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has declared no conflict of interest related to this research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KBT | Knowledge-based theory |

| KM | Knowledge management |

| KMPs | Knowledge management practices |

| KRM | Knowledge risk management |

| HRM | Human resource management |

| HRMPs | Human resource management practices |

| PSEs | Public sector enterprises |

| RBT | Resource-based theory |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Eigenvalues.

Table A1.

Eigenvalues.

| Eigenvalue | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.0624710 | 17.7488257 | 0.2467 | 0.2467 |

| 2 | 5.3136453 | 1.1289751 | 0.0568 | 0.3035 |

| 3 | 4.1846702 | 0.3219382 | 0.0448 | 0.3483 |

| 4 | 3.8627320 | 0.4414459 | 0.0413 | 0.3896 |

| 5 | 3.4212860 | 0.0565490 | 0.0366 | 0.4262 |

| 6 | 3.3647371 | 0.3654880 | 0.0360 | 0.4622 |

| 7 | 2.9992490 | 0.2261573 | 0.0321 | 0.4942 |

| 8 | 2.7730917 | 0.0872697 | 0.0297 | 0.5239 |

| 9 | 2.6858220 | 0.1658955 | 0.0287 | 0.5526 |

| 10 | 2.5199265 | 0.2292394 | 0.0270 | 0.5796 |

| 11 | 2.2906871 | 0.1845670 | 0.0245 | 0.6041 |

| 12 | 2.1061201 | 0.1233277 | 0.0225 | 0.6266 |

| 13 | 1.9827923 | 0.0754389 | 0.0212 | 0.6478 |

| 14 | 1.9073534 | 0.1567255 | 0.0204 | 0.6682 |

| 15 | 1.7506278 | 0.0797255 | 0.0187 | 0.6869 |

| 16 | 1.6709023 | 0.0522239 | 0.0179 | 0.7048 |

| 17 | 1.6186784 | 0.1108546 | 0.0173 | 0.7221 |

| 18 | 1.5078239 | 0.0513008 | 0.0161 | 0.7383 |

| 19 | 1.4565231 | 0.0522371 | 0.0156 | 0.7538 |

| 20 | 1.4042860 | 0.0736920 | 0.0150 | 0.7689 |

| 21 | 1.3305940 | 0.0398661 | 0.0142 | 0.7831 |

| 22 | 1.2907279 | 0.1487147 | 0.0138 | 0.7969 |

| 23 | 1.1420131 | 0.0241579 | 0.0122 | 0.8091 |

| 24 | 1.1178553 | 0.0311689 | 0.0120 | 0.8211 |

| 25 | 1.0866863 | 0.0637296 | 0.0116 | 0.8327 |

| 26 | 1.0229567 | 0.0343031 | 0.0109 | 0.8436 |

| 27 | 0.9886536 | 0.0781787 | 0.0106 | 0.8542 |

| 28 | 0.9104750 | 0.0305848 | 0.0097 | 0.8639 |

| 29 | 0.8798902 | 0.0383027 | 0.0094 | 0.8734 |

| 30 | 0.8415874 | 0.0240626 | 0.0090 | 0.8824 |

| 31 | 0.8175248 | 0.0693815 | 0.0087 | 0.8911 |

| 32 | 0.7481433 | 0.0427112 | 0.0080 | 0.8991 |

| 33 | 0.7054322 | 0.0261233 | 0.0075 | 0.9067 |

| 34 | 0.6793089 | 0.0277614 | 0.0073 | 0.9139 |

| 35 | 0.6515475 | 0.0367111 | 0.0070 | 0.9209 |

| 36 | 0.6148363 | 0.0409891 | 0.0066 | 0.9275 |

| 37 | 0.5738473 | 0.0174857 | 0.0061 | 0.9336 |