Abstract

Many Korean local governments have enacted ordinances that enable resident participation in the supervision of public construction projects, yet an implementation gap persists between the legal framework and actual engagement. This study thus examined causes of and strategies for residents’ participation in defect reporting and the role of resident supervisor using a sequential embedded design. Administrative data from local governments were analyzed, followed by 94 survey data from resident representatives. Awareness about the defect reporting and role of resident supervisor was low, while support and intention for participation were higher. Awareness, perceived ordinance effectiveness, and support for resident participation were associated with intention, whereas financial rewards showed no significant association. These results suggest that insufficient awareness and trust—not lack of motivation—are the primary barriers, indicating the need to shift from offering rewards to targeted communication, procedural transparency, and capacity-building. This study’s contribution is its mixed-methods empirical assessment of this gap, informing the design of resident-participation policies by prioritizing awareness campaigns, procedural transparency, and training for resident supervisors.

1. Introduction

In Korea, construction defects remain a source of accidents and complaints. According to a press release by the Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport (2025), of the 1774 cases reviewed in 2024, 1399 were identified as defect-related, resulting in a defect rate of 78.9%, which has increased annually since 2020. In response, local governments have enacted Construction Defect Prevention Ordinances (CDPOs) to enable resident participation in construction supervise and defect-reporting, thereby encouraging public involvement. In response, local governments have enacted CDPOs to enable resident participation in construction supervision and defect reporting through three core programs: the defect-reporting program, the reward program, and the Resident-Participatory Supervision Program (RPSP). These schemes aim to prevent defects by engaging citizens rather than relying solely on oversight by public agencies.

Democratic governments often produce more policies than they can implement (Xavier et al., 2024), and policy success depends on administrative capacity during their implementation and monitoring (Adam, 2025). In Korea, despite higher-level statutes and many local ordinances that institutionalize resident participation, actual engagement is limited. This reveals an implementation gap between institutional design and practice.

This study investigates the causes of the implementation gap in Korea’s defect-reporting program and RPSP and identifies policy levers to activate substantive participation. Using a sequential embedded mixed-methods design, we link ordinance and implementation records (defect reports, reward payments, RPSP activity) with a survey of resident representatives in Dongjak-gu, Seoul. We examine determinants of participation intention, focusing on scheme awareness, perceived policy effectiveness, and institutional trust, relative to prior experience, attitudes toward monetary rewards, and perceived procedural inconvenience. We also analyze the widespread absence of defect-reporting records across local governments and propose policy directions to improve uptake and performance.

This study’s unique contribution is to deliver a mixed-methods empirical assessment of the implementation gap in Korea’s resident participation schemes and to translate the findings into focused policy directions—raising awareness, strengthening procedural trust, and building participation capacity. Despite nationwide legal frameworks for resident-participatory schemes in construction defect prevention, their actual use remains rare and largely unmeasured. To date, no empirical study has quantified the implementation gap or tested its determinants using administrative records and resident-level data. This matters now because defect rates are rising (78.9% in 2024) while defect-reporting and RPSP activity remain negligible across jurisdictions that have enacted ordinances. This study empirically quantifies the implementation gap and tests whether awareness and institutional trust, rather than prior experience or monetary incentives, shape participation intention.

2. Literature Review

This section synthesizes legal and theoretical foundations for resident-participatory governance in construction oversight. It maps Korean frameworks and positions awareness, perceived effectiveness, and institutional trust as determinants of participation. It identifies the research gap and derives the research questions.

2.1. Legal Frameworks to Prevent Construction Defects

Citizens have long pressed to be more involved in governance decisions that affect their lives (Mitlin, 2021), with resident-participatory governance emerging as a concept that goes beyond simple information sharing to actively address social problems through communication among the public, experts, stakeholders, and decision-makers. In the context of construction projects, such participation is expected to prevent quality issues and help mitigate public concerns about projects. In Korea, to promote resident participation, both national and local governments have established policies, with ordinances continuing to be actively revised and enacted in recent years.

Higher-level legislation, such as the Local Contract Act and the Framework Act on the Construction Industry, provides the legal basis for two main types of local ordinances: CDPOs and Contract Review Committee Ordinances (CRCOs). Both streams of ordinances are designed to work toward the ultimate legislative purpose of proactively preventing construction defects through resident participation. One key program is the Resident Participation Supervision Program (RPSP), which involves residents with expertise who visit construction sites and inspect the construction process. The Enforcement Decree of the Local Contract Act (Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2023) includes the roles and administrative elements of resident supervisors.

From the historical research efforts, the causes of inadequate quality management in construction have been identified as poor supervision, lack of staff training, managers’ low prioritization of quality, and time constraints (Lambers et al., 2025). Agnieszka and Rosane (2019) emphasize that, to prevent defective construction, the necessity and independence of third-party supervisors should be strengthened. Oladinrin et al. (2017), meanwhile, argue that whistleblowing in construction projects can prevent the serious consequences and economic losses resulting from undiscovered fraudulent activities. In this context, these legal instruments are designed to prevent defective construction by considering residents as potential independent supervisors or whistleblowers.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations of Resident Participation

In the urban development and construction sector, resident participation is recognized as a key factor in improving the quality of decision-making, enhancing policy acceptance, and fostering sustainable development. As highlighted in Hofer et al. (2024), residents are recognized as key actors in collective local development initiatives. Moving beyond traditional survey or public hearing methods, innovative participation approaches such as citizen-led living labs and online platforms are being introduced, enabling citizens to act as opinion contributors, monitors, and evaluators. Such changes transform residents from passive participants to co-managers of urban public spaces, thereby further enhancing the effectiveness and impact of participation programs (Suomalainen et al., 2022).

Arnstein (1969) conceptualized citizen participation as an eight-rung ladder ranging from non-participation through tokenism to genuine citizen power, arguing that authentic participation requires redistribution of power from officials to citizens. Verba et al. (1995) developed the Civic Voluntarism Model, positing that citizens participate when they can (resources), when they want to (motivation and efficacy), and when they are asked (mobilization through networks). Coleman (1988) theorized social capital as resources embedded in social structures that facilitate collective action, and Putnam (2000) linked networks and norms of civic engagement to generalized trust and government performance.

Resident participation has been studied across diverse sectors, including urban planning, large-scale infrastructure construction, and environmental management. In urban planning and spatial management, research has addressed urban heritage preservation (Zhou et al., 2023), the management of privately owned public spaces (Jung et al., 2024), and the maintenance of urban green areas (Bressane et al., 2024). In infrastructure and construction projects, studies have examined large-scale infrastructure development (Li et al., 2012; Xiao & Hao, 2025), mega transport infrastructure (Erkul et al., 2016), and public works, including c Other studies discussed estuarine water quality management (Tseng et al., 2021) and disaster management planning (Pearce, 2003), indicating that resident-participatory governance spans multiple policy domains beyond the construction sector.

The roles of residents can largely be divided into four categories. First, in their role as information providers, residents can report problems with public services or assess satisfaction through surveys (Hilgers & Christoph, 2010). Second, residents can act as opinion contributors and evaluators, providing feedback within decision-making processes such as project planning or design (Li et al., 2012). Third, they may perform monitoring and oversight functions, such as inspecting violations in privately owned public spaces or monitoring river environments (Jung et al., 2024). Lastly are cases where residents are deeply involved in projects as active and direct participants, organizing workshops or leading small-scale experimental initiatives (Park & Fujii, 2023).

Based on the typology of resident participation discussed above, defect reporting can be understood as an information provider role, while the RPSP relates to monitoring and supervision roles. Recognizing these distinctions is essential when evaluating how such policies function in practice, which underscores the need for analytical approaches that examine not only outcomes but the implementation process itself (Hudson et al., 2019).

To investigate policy effectiveness, Jung et al. (2024) employed a mixed-methods approach, supplementing quantitative analysis results with interviews and integrating both data types in the interpretation stage, with Xiao and Hao (2025) adopting a similar approach that deepened interpretation through qualitative analysis following quantitative knowledge-mapping analysis. These studies mainly used case study methods based on interviews and secondary data. This method of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, such as integrating survey data with interview insights, offers a more balanced and comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

2.3. Research Gap and Questions

As examined in the literature review, diverse studies on civic participatory governance have been conducted in the fields of construction and urban development. In particular, numerous studies have explored participatory planning and design in the field of urban architecture (Bernasconi & Blume, 2025; Diep et al., 2022; Iversen & Dindler, 2014; Ng et al., 2023, 2024; Shimizu & Almazán, 2024; Slingerland et al., 2022). Nevertheless, a research gap remains: no study has conducted follow-up tracking or evaluations, nor proposed policy improvements for preventing construction defects through resident-participatory schemes.

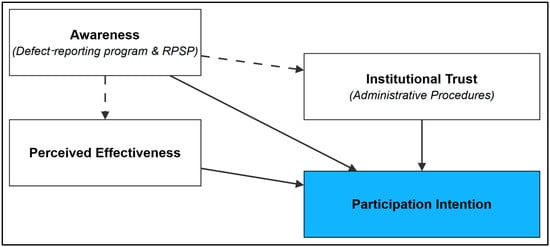

Based on the theoretical foundations discussed, this study conceptualizes that residents’ participation intention. These factors are (1) awareness of the programs, (2) perceived effectiveness of these programs, and (3) institutional trust in the administrative procedures that manage them. These relationships are illustrated in the conceptual framework below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Solid arrows denote hypothesized associations; dashed arrows denote theorized reinforcing paths.

This framework, which emerges from the reviewed literature, leads to the following research questions designed to empirically investigate these relationships and the current state of implementation.

Accordingly, this study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1. What is the current state of the implementation gap in resident-participation schemes for construction defect prevention, as observed from administrative data?

- RQ2. To what extent do residents possess awareness and experience of current resident-participation schemes?

- RQ3. What are the key determinants influencing residents’ intention to participate in these schemes (focusing on awareness, institutional trust, and perceived effectiveness)?

3. Methodology

This section describes the sequential embedded mixed-methods design, data sources, measures, and analytic strategy. It explains how administrative records and the survey are integrated to address the research questions.

3.1. Research Framework

The objective of this study is to empirically identify the causes of insufficient implementation and the critical design factors of resident-participatory schemes for construction defect prevention. Accordingly, this study addresses the following research questions using a sequential embedded design. This approach allows quantitative data (administrative records, surveys) to first identify the scale of implementation gaps and participation patterns (RQ1, RQ2). The embedded qualitative phase then provides an in-depth explanation of the mechanisms and barriers (RQ3), bridging what the data show with why those patterns exist.

First, to examine the current state of the implementation gap in resident-participation schemes for defective construction prevention (RQ1), relevant ordinances and administrative performance records will be analyzed using descriptive statistics. Second, to assess residents’ awareness and experiences (RQ2), this study conducts a survey of resident representatives, measuring awareness, perceived effectiveness, and related factors through descriptive statistics and factor analysis. Finally, to identify the key determinants of residents’ intention to participate and explore policy alternatives (RQ3), major variables are derived from the survey analysis, and a qualitative thematic analysis of open-ended responses will be carried out to examine barriers and improvement needs in depth.

This study is distinctive in its empirical investigation of implementation gaps in resident-participation schemes for defect prevention. It employs a mixed-methods design that combines administrative data with survey results. By demonstrating the limitations of existing schemes with evidence, the study proposes policy improvements from the residents’ perspective. This approach contributes to both theoretical and practical advances in governance and policy studies.

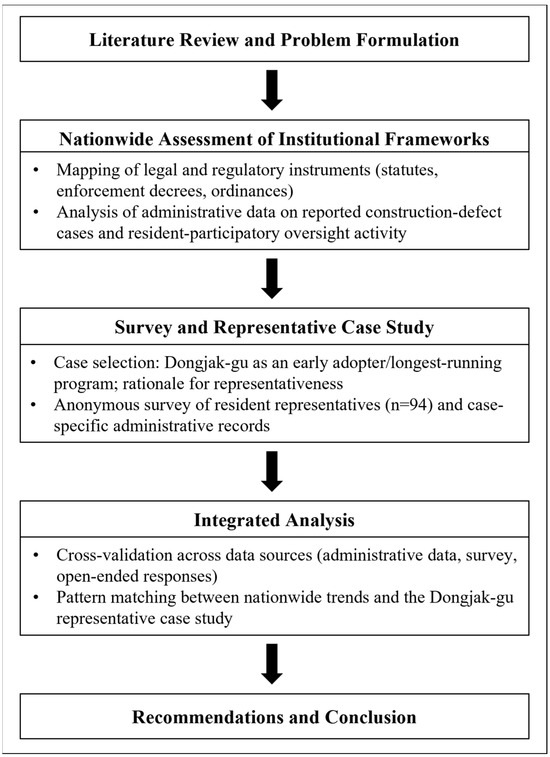

Figure 2 illustrates the research procedure of this study. A sequential embedded design was applied, with the quantitative phase forming the primary design, and the qualitative phase subsequently integrated to complement the interpretation of the quantitative results. This study first analyzed the characteristics of local government ordinances to determine the institutional feasibility. After identifying the current situation using administrative data (quantitative analysis), a survey was conducted to explore the causes and context, with a qualitative analysis used to complement the interpretation of these results.

Figure 2.

Research framework of this study.

The research framework proceeded in three stages: identifying national trends, conducting an in-depth analysis of a representative case (Dongjak-gu), and linking these findings to national-level policy discussions. At the national level, the extent of institutional adoption was quantitatively reviewed. Hypotheses regarding underlying causal mechanisms were then refined by examining cases of early adoption and long-term operation. Finally, the results were integrated into policy implications from an analytical generalization.

Specifically, in the first stage of administrative data analysis, and despite the widespread adoption of the RPSP and the reward program in most local governments, an implementation gap was identified, leading to the second stage: survey design. To diagnose the causes of this gap, survey questions were structured around key explanatory variables such as ‘awareness of the schemes’, ‘perceived effectiveness’, and ‘trust in participation’. For the quantitative data analysis, the study employed descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation analysis, chi-square tests (or Fisher’s test), and the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) method for multiple testing correction. For the qualitative analysis, a thematic analysis was performed on open-ended responses.

3.2. Data Sources and Collection

3.2.1. Legislative Corpus

We collected the full texts of CDPOs and CRCOs from the National Law Information Center, covering 126 and 237 ordinances, respectively, and coded resident supervisors’ authorization, roles, and procedures. To link legal design to practice, we also obtained 2021–2025 records on defect reports, reward payments, and RPSP-supervised works via the national Open Government Portal to assess operational uptake.

The Local Contract Act (Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2023) includes the legal basis for resident supervisor participation as follows: “Article 16 (Supervision) … (2) the head of a local government or a contracting officer shall entrust the representative of residents … as a supervisor (‘resident supervisor’) … (3) Any resident supervisor may communicate residents’ suggestions … or request correction of illegal or unjust acts …”. Furthermore, the Enforcement Decree of the Local Contract Act (Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2024) includes the roles and administrative elements of resident supervisors.

The mandatory provisions of the Local Contract Act stipulate that resident supervisors are included in the CRCO, and most local governments have adopted this. So far, the scheme has mainly spread in a top-down manner, with CDPO thus far adopted by 14 out of 17 (82%) metropolitan-level governments and 126 out of 226 (56%) municipal-level governments. Although the Seoul Metropolitan Government does not operate a CDPO, 17 out of 25 autonomous districts of Seoul (68%) have introduced it themselves. Most recently, it was enacted in May 2025 in Nam-gu (Busan Metropolitan City Nam-gu, 2025).

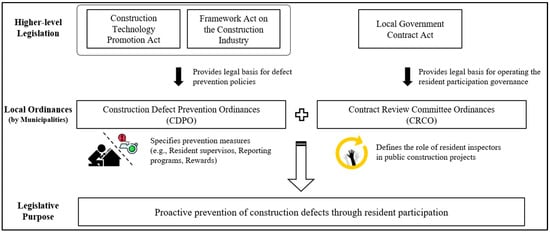

Figure 3 summarizes this legal framework. Higher-level laws provide a basis for local ordinances: Construction Defect Prevention Ordinances (CDPOs) and Contract Review Committee Ordinances (CRCOs). CDPOs specify prevention measures, while CRCOs define resident inspector roles. These ordinances work together to prevent construction defects through resident participation.

Figure 3.

Legal Framework for Resident Participation in Construction Defect Prevention.

3.2.2. Administrative Data

The use of administrative data for decision-making is a common approach in policy and scheme evaluation within the public sector (Zanti et al., 2022), and in this study, they were collected as follows: Full texts of ordinances were obtained from the National Law Information Center, operated by the Ministry of Government Legislation of Korea (Ministry of Government Legislation of Korea, 2025). 126 CDPO related to defect prevention and 237 related to resident supervisors were collected, with the characteristics of each then analyzed to determine the roles and scope of residents

Based on the ordinance analysis results, it was determined which local governments’ administrative data were required. Subsequently, through Korea’s Information Disclosure Portal (Ministry of the Interior and Safety, 2025), data on defect-reporting records, records of reward disbursements, and the number/scale/type of public projects with resident supervisors between 2021 and 2025 were collected from the corresponding local governments. Ultimately, records of defect reporting were obtained from 10 local governments, while records of resident-participatory construction supervision were collected from 20 local governments with populations of 500,000 or more that responded. All administrative data were publicly disclosed, aggregated, and anonymized; thus, individual consent was not required.

3.2.3. Survey

Dongjak-gu has been operating the RPSP since 2005, and in 2012, it became the first among Seoul’s autonomous districts to introduce and operate the reward program for defect-reporting, leading the study to select it as a representative case for early adoption and long-term operation of resident participation schemes; as such, the survey was distributed to all 526 resident representatives in Dongjak-gu through relevant officials, with responses collected anonymously through Google Forms. A total of 94 valid responses were received (17.9% response rate). All administrative data were publicly disclosed, aggregated, and did not contain personal identifiers

The questionnaire was designed to measure various aspects, including residents’ experience of construction and suspected related defects; awareness of the defect-reporting program, reward program, and RPSP; policy design preferences; attitudes toward resident participation; and reporting and participation intention. To facilitate smooth survey collection, questions employed a 2-point or 3-point scale coded as 0/1 or 0/1/2 for analysis.

Survey questions were developed based on a review of relevant ordinances, prior research, preliminary interviews, and administrative data. For example, in the category of construction suspected defects experience, respondents were asked “Yes/No” if construction work had taken place near their residence in the past three years, and if they had ever suspected encountering construction defects or experienced inconvenience at a construction site. To assess program awareness, respondents were asked “Yes/No” if they were aware of the program for reporting construction defects, the reward program, and the RPSP. Regarding policy design preferences, support for lowering the eligibility criteria for facilities subject to reporting was assessed using a 3-point scale of “Disagree/Neutral/Agree”. Table 1 presents key examples of survey items across four main categories: experience with construction and defects, awareness of resident-participation schemes, evaluation and preference, and perceptions and participation intention. The complete list of survey items is provided in Appendix A. Additionally, open-ended responses were collected regarding “suggestions or opinions for improving the schemes”.

Table 1.

Survey Items and Variables (Examples).

The questionnaire was reviewed by legal experts and officials from relevant ministries to ensure its validity. Subsequently, a pilot survey was conducted to set the sample size, recruitment method, and period, and to improve the questionnaire’s clarity by addressing ambiguous questions and difficulty levels. Thus, the survey focused on comprehensively understanding residents’ perceptions and intentions and collecting quantitative and qualitative data.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study conducted quantitative and qualitative analyses to identify the causes of the implementation gap between the legal framework and its practical utilization, as observed through the administrative data analysis. For the quantitative data analysis, the survey data were used to examine the factors affecting the ‘intention to participate as a resident supervisor’ (dependent variable) within the group of resident representatives who were most likely to be aware of the schemes. This outcome variable was measured using a 3-point ordinal scale (‘No’/0, ‘Unsure’/1, ‘Yes’/2). This multi-level measurement was chosen over a binary (Yes/No) scale to differentiate clear refusal from mere hesitation (‘Unsure’). This distinction is critical for capturing respondents who may lack awareness but are not inherently opposed to participation.

To achieve this, the distribution of key variables was examined using descriptive statistics, with cross-tabulation and chi-square tests (or Fisher’s exact test) performed. The main independent variables included ‘awareness of the defect-reporting program’, ‘awareness of the reward program’, ‘awareness of the RPSP’, ‘perceived effectiveness of the ordinance’, and ‘support for resident participation’. All variables were coded such that a higher value indicated ‘greater awareness/support/intention,’ and the strength of association between them was assessed using Cramer’s V. Additionally, to control for the accumulation of Type I errors due to multiple testing, the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR method was applied at a significance level of 5%.

The qualitative data analysis focused on identifying specific barriers and improvement requirements for scheme implementation that are difficult to grasp through a quantitative analysis alone, based on open-ended responses. By analyzing meaningful opinions collected from a total of 19 resident representatives, in-depth perceptions and suggestions from stakeholders most directly engaged with the programs were obtained.

Finally, we integrated the quantitative and qualitative results with administrative records; qualitative themes were used to assess alignment with the associations between awareness/support and participation intention, to clarify the null effects of monetary rewards and direct defect experience, and to corroborate the implementation gap.

4. Results

This section presents empirical results on three fronts: ordinance adoption and administrative activity, survey findings, and qualitative insights. It quantifies the implementation gap and tests associations between awareness, perceived effectiveness, institutional trust, and participation intention.

4.1. Adoption of Ordinances

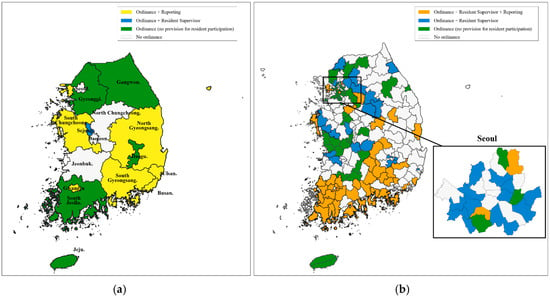

It was confirmed that the legal basis for resident participation in preventing construction defect schemes is broadly established across local governments in Korea, and Figure 4 below visually represents the status of these ordinance adoptions. As of 2025, 14 out of 17 (82%) metropolitan governments (Figure 4a) and 126 out of 226 (56%) basic local governments (Figure 4b) have provisions for such schemes. In the case of the Seoul Metropolitan Government, there is no ordinance at the city-hall level, but as shown in the enlarged map of Figure 4b, 17 out of 25 autonomous districts (68%), including Dongjak-gu, have independently adopted and are currently implementing their own ordinances. This adoption confirms the legal framework is in place, setting a baseline to measure the implementation gap.

Figure 4.

Visualization of Resident Participation in Construction Defect Prevention Ordinances; Metropolitan Level (a) and Municipal Level (b).

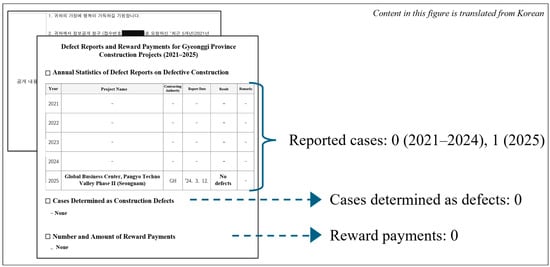

However, in contrast to the widespread enactment of CDPOs, the actual implementation performance of the scheme is considerably low, indicating a significant gap between the intention of institutional design and implementation performance. An analysis of defect-reporting records and reward disbursement records from 10 major local governments revealed that most local governments had no records or very few, with eight locations—Incheon Metropolitan City, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, Seoul Nowon-gu, Jeollanam-do, Paju, Gwangju Metropolitan City, and Busan Metropolitan City—possessing no records during the period. Gyeonggi-do made one report in 2025, but it did not lead to defect processing (Figure 5), and Bucheon City had only one case out of six reports judged a defect, with no reward disbursements, signifying that the resident reporting and reward program is virtually inactive. This pattern illustrates the implementation gap, indicating that legal policies alone have not yet translated into active operation of the schemes.

Figure 5.

Sample Administrative Data; Reported Cases (Gyeonggi-do, 2021–2025).

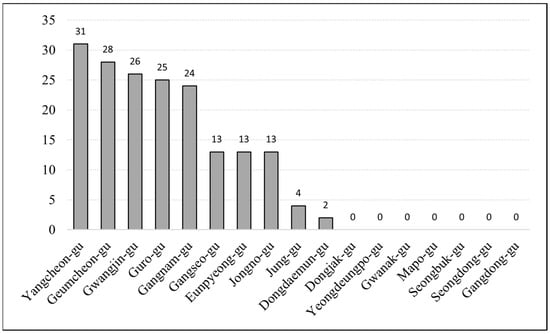

The operational status of the RPSP revealed similar problems. Figure 6 displays the number of supervised cases by district in Seoul, indicating that most autonomous districts—except for a few such as Yangcheon-gu and Geumcheon-gu—recorded very limited or no activity. Moreover, an analysis of performance data from 20 local governments revealed that the resident participation scheme was not being properly implemented, with nine local governments, including the Seoul Metropolitan Government headquarters, possessing no operational records. Meanwhile, the activities of the 11 local governments that reported performance were centered on facilities closely related to daily life, such as roads, parks, and landscaping, with activities surveyed being mainly site tidying or safety inspections. This is far from the original purpose of inspecting construction defects in large-scale construction or infrastructure facilities. This trend indicates both a quantitative gap in participation levels and a qualitative gap in implementation focus, pointing to a misalignment between the scheme’s policy intent and its actual field application.

Figure 6.

Number of Cases for Resident-Participatory Supervise by District, Seoul (2021–2025).

These results from administrative data provide an answer to RQ 1 by demonstrating that despite a broad legal framework, both the defect-reporting and RPSP schemes are barely utilized in practice. This significant implementation gap highlights the need for further analysis of its underlying causes.

4.2. Survey Results

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

Although Dongjak-gu was the first district in Korea to adopt the resident-participation scheme and has operated it the longest, it recorded no cases and possesses no operational records of resident inspections on construction defects during the observation period (2021–2025). With no outcomes observed even under favorable conditions of early adoption and long-term operation, this important case, in particular, indicates the limitations of the scheme. The results of the descriptive statistics analysis for the main variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency and Percentage Distributions of Survey Variables.

Key results are summarized as follows: First, the majority of respondents, 63.83%, reported having experience with nearby construction within the past three years. However, the proportion who suspected construction defects or experienced direct inconvenience was relatively low at 15.96%.

Overall, awareness of resident participation schemes was found to be low, with only 28.72% of respondents aware of the defect-reporting program, and a mere 13.83% aware of the reward program. Awareness of the RPSP was also low at 22.34%, indicating insufficient promotion of the schemes.

In contrast, support for policy improvements was high: A majority of respondents supported lowering the eligibility criteria for construction project reporting (51.06%), increasing the report reward (65.96%), and raising the stipend for resident supervisors (56.38%). Regarding the perceived effectiveness of the scheme, ‘neutral’ was the most common response (56.38%), but positive evaluations indicating ‘effective’ (37.23%) were more frequent than ‘ineffective’ (6.38%).

Finally, 81.91% expressed support for resident participation itself, indicating a largely positive attitude. When asked about their ‘intention to participate as a resident supervisor’, ‘yes’ was the most common response at 45.74%, followed by ‘unsure’ (32.98%) and ‘no’ (21.28%), confirming a high potential intention for participation. These descriptive statistics, which detail residents’ low awareness of the schemes (e.g., 13.83–28.72%) and their experiences with nearby construction, provide an answer to RQ 2.

4.2.2. Cross-Tabulations and Association Tests

To identify factors associated with residents’ intention to participate as resident supervisors, a cross-tabulation analysis was performed along with chi-square tests. Fisher’s exact test p-values were derived when the assumption of the minimum expected cell frequency was violated. To control for the accumulation of Type I errors due to multiple testing, the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR method was applied at a significance level of 5% to determine significance (q < 0.05). To assess the effect size, or the strength of association these categorical variables, Cramer’s V coefficient was calculated. Detailed analysis results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Chi-square/Fisher Tests and Cramer’s V for Participation Intention (n = 94).

The analysis revealed that 4 out of 10 variables showed a statistically significant association with residents’ intention to participate as resident supervisors. Among these significant variables, ‘support for resident participation’ showed the highest statistical significance (p < 0.001), indicating that residents with a more positive view of resident participation schemes had a higher intention to participate as resident supervisors; however, in terms of the strength of association (Cramer’s V), ‘awareness of the defect-reporting program’ (V = 0.314) demonstrated the strongest relationship with participation intention, followed by ‘awareness of the RPSP’ (V = 0.300). By contrast, both ‘support for resident participation’ and ‘perceived effectiveness of the schemes’ had a Cramer’s V value of 0.269, indicating a small to moderate effect size. These results confirm that residents’ awareness of existing schemes plays a comparably stronger association with participation intention, consistent with the statistical findings reported above.

Conversely, direct experience variables such as ‘experience with nearby construction’ (p = 0.838) or ‘experiences with suspected defects/inconvenience’ (p = 0.715) showed no statistically significant relationship with participation intention. Furthermore, attitudes toward financial rewards, such as ‘support for expanding the reward program’ (p = 0.910) or ‘support for raising the stipend for resident supervisors’ (p = 0.513), were not found to significantly associated with participation intention, suggesting that residents’ motivation for participation may be related to their positive perceptions of and trust in the schemes, rather than direct experiences of inconvenience or monetary reward. This analysis of associations identifies the key determinants—such as ‘awareness of the defect-reporting program,’ ‘awareness of the RPSP,’ ‘perceived effectiveness,’ and ‘support for resident participation’—that are significantly associated with participation intention, thereby addressing RQ 3.

4.3. Qualitative Insights from Open-Ended Responses

The final question of the survey asked residents to provide open-ended opinions on how the schemes could be improved, aiming to understand their in-depth perceptions, which are difficult to grasp through quantitative data alone. Insightful responses were gathered from a total of 19 respondents, and the results of their analysis by major themes are as follows.

- 1.

- Strengthening Promotion

The most frequently expressed opinion concerned the lack of adequate promotion of the resident-participation schemes, leading to low awareness. One respondent noted, “I first learned about the programs through this survey,” while many called for stronger promotional efforts to increase resident engagement, aligning with the quantitative results in Section 4.2.1, where only 22.34% of respondents were aware of the RPSP. In this way, the qualitative data strongly support the conclusion that insufficient promotion is the primary factor contributing to low awareness. One respondent stated that “even if a budget is allocated for resident participation, it is useless if promotional efforts and administrative agencies lack genuine commitment,” highlighting the need for stronger administrative initiatives to ensure effective operation of the schemes.

- 2.

- Institutional Trust in Administrative Procedures

Transparent micro-municipal administration fosters residents’ trust and engagement by combining efficient management with active information disclosure (Cristofaro et al., 2025). In the open-ended responses, transparency of information and procedural trust were also highlighted as crucial prerequisites for effective resident participation. The opinion that “confidentiality must be assured to guarantee personal information of reporters is not disclosed” suggests the need to reduce the risks associated with participation. Furthermore, there was strong demand for overall construction transparency, including “notification of contract details during construction,” “disclosure of construction information,” and “selection of experts without corruption”. One respondent also presented a balanced perspective, suggesting that “experts and residents should be appropriately involved,” but “personal inconvenience complaints should be limited to avoid hindering smooth construction”.

- 3.

- Expertise of Resident Supervisors

Residents suggested specific ways to enhance the quality of participation, with one respondent acknowledging that “resident participation may have limited utility in highly technical fields such as construction safety management” and proposed “utilizing a group of retired experts from relevant fields”. Another suggested “operating education programs for resident supervisors and selecting individuals after evaluating those who have completed the training,” demonstrating a perspective on the necessity of securing professional expertise.

These qualitative analysis results provided a contextual explanation for the reality that residents remain unaware of the schemes’ existence (4.2) and the failures to implement the scheme, even when established (4.1). They also demonstrated that residents are willing to offer constructive alternatives to genuinely advance the resident participation schemes, such as professional training, information disclosure, and the utilization of retired experts, rather than simply raising complaints.

Taken together, these qualitative opinions complement the quantitative patterns, explaining why participation remains low despite supportive attitudes. Statistical results (Section 4.2) identified low awareness and low perceived effectiveness as key factors hindering participation. The open-ended responses corroborate this: insufficient promotion explains the low awareness, while limited transparency and expertise concerns explain the low perceived effectiveness. This integration supports an explanatory path where low awareness leads to low trust and effectiveness concerns, which results in weak participation, thereby bridging the study’s quantitative and qualitative strands.

5. Discussion

This section examines mechanisms linking awareness, procedural trust, and perceived effectiveness to participation, and considers alternative explanations. It draws design and implementation guidance from the evidence and outlines limitations and directions for future research.

5.1. Interpreting the Results

The main findings of this study confirmed that despite the widespread adoption of CDPO, they have not been sufficiently activated, resulting in very weak performance in practice, clearly demonstrating an implementation gap between the legal basis of the resident participation schemes and their field operations.

According to the survey in Section 4.2, awareness of the schemes among resident representatives in Dongjak-gu, Seoul, was only 28.72% for the defect-reporting program, 13.83% for the reward program, and 22.34% for the RPSP, indicating a severe lack of promotion of the resident participation schemes. Our qualitative analysis strongly suggests that this inadequacy is the fundamental factor associated with low resident awareness, with many respondents stating they learned about the resident participation scheme for the first time through this survey. It can be inferred that this lack of awareness and subsequent lack of participation appear to be linked in a vicious cycle where the schemes’ function is weakened. Hao et al. (2022) noted that “the inability of citizens to advise on government issues due to lack of information and empowerment programs … also affects the extent to which citizens participate in the governance process,” and our findings are consistent with this conclusion.

Our cross-tabulation analysis showed that several factors were statistically significantly associated with resident participation intention. It is crucial to interpret these findings as associative rather than causal, as the cross-sectional design cannot establish the direction of the relationship. The significant factors were ‘support for resident participation,’ ‘perceived effectiveness of the scheme,’ ‘awareness of the defect-reporting program,’ and ‘awareness of the RPSP’. Conversely, direct experience variables such as ‘experience with nearby construction’ or ‘experiences with suspected defects/inconvenience,’ or ‘attitudes toward financial reward’ were not significantly associated with participation intention, suggesting that the motivation for participation is strongly associated with trust in and awareness of the schemes, rather than monetary reward or direct inconvenience.

The association between participation intention, perceived effectiveness, and institutional trust aligns with international research on participatory governance. Prior studies show that citizen trust increases when authorities act fairly and when participation is perceived as effective (Reichborn-Kjennerud et al., 2021). These results indicate that procedural trust and perceived efficacy are key factors sustaining participation. Public institutions would therefore benefit from engaging residents who distrust but still participate, as well as those who lack trust and do not participate.

In contrast, other studies emphasize incentive-based participation. Research on community-based monitoring highlights tangible personal outcomes as motivators (Wehn & Almomani, 2019), and work on sustainable development and green building points to fiscal incentives as participation drivers (Kumar et al., 2024; Mecca & Mecca, 2023). Such instruments can reduce investment risks, accelerate the return on investment, and provide leverage to encourage private actors. In this study, participation functions as administrative oversight rather than personal benefit, suggesting that procedural trust and perceived efficacy outweigh monetary incentives.

Moreover, the low awareness among resident representatives, who are typically deeply involved in local governance, suggests that awareness among general residents is even lower. An interview with the Dongjak-gu official in charge also revealed that about 4 million KRW (approximately 3000 USD) is spent annually, primarily on posters. This poster-centric approach suggests that active promotion efforts have been limited

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study refines theories of participatory governance, implementation, and institutional trust by showing that legal adoption does not translate into engagement unless residents recognize the schemes and trust the procedures. The findings support a cognitive pathway in which awareness and perceptions of fair and transparent processes strengthen procedural trust and perceived efficacy, which in turn predict participation intention. Normative support is necessary but insufficient, and the weak associations of monetary rewards and direct defect experience align with institutional trust and intrinsic motivation perspectives. In construction oversight, residents function as independent monitors analogous to third-party inspection and whistleblowing, making credible procedures more consequential than extrinsic incentives. The sequential embedded design also shows how mixed data can identify mechanisms behind implementation gaps and yields propositions for mediation among awareness, trust, efficacy, and participation.

5.3. Policy Design Implications and Recommendations

Since there may be differences between policies’ intended formulation and actual implementation, their success or failure cannot be judged solely on their outcomes; instead, a continuous process of monitoring and evaluating how various policy components operate in the field is essential (Hanberger, 2001). The implementation gap identified in this study highlights the importance of such continuous evaluation and improvement, leading to the following policy implications.

First, active and strategic promotion of the schemes, along with resident participation platforms, is needed. A synthesis of survey results and qualitative thematic analysis of open-ended responses shows that scheme awareness is remarkably low, which is associated with to a lack of impetus for participation. To address this, residents should be provided with platforms to voice their opinions, allowing promotional effects to be maximized. For example, community assemblies serve as an essential means to empower residents, enabling them to collectively express their views and participate in decisions about how public resources are allocated. Therefore, a multi-faceted promotional strategy is required, going beyond simple notices or postings, to help residents genuinely engage with and understand the schemes.

Second, there needs to be a shift toward policy designs that enhance trust and efficacy rather than monetary reward. The results showed that expanding report rewards or raising the stipend for resident supervisors was not significantly associated with participation intention; instead, perceived effectiveness of the scheme and support for resident participation schemes were found to have a greater association. Our qualitative analysis also highlighted the need for efforts to enhance participation efficacy, such as strengthening the protection of reporters’ identities, transparently disclosing reporting procedures and outcomes, and disclosure of relevant information, such as sharing success stories that led to actual improvement of construction quality. Beyond institutional mechanisms, participation also hinges on personal, psychological, and even physiological capacities (Vasiliades et al., 2021), since these factors fundamentally shape citizens’ willingness and capacity to engage.

Third, we propose strengthening the professionalism and systematic nature of participation. Given that the RPSP is overly focused on safety inspections or maintaining site cleanliness, but has not extended this mindset to substantive inspection of construction defects, the study proposes institutional improvements to enhance the quality of participation. These include utilization of retired experts as well as providing general resident participants with education on types of construction defects and inspection items. Strengthening professionalism in this way can contribute to increasing the effectiveness of participation and establishing trust in the schemes.

Based on these three directions, we propose the following concrete implementation modules. These practices are not yet widespread—which itself underscores the systemic implementation gap identified in this study. However, a few pioneering municipalities have recently begun to pilot them, providing valuable and timely precedents:

- Transparency and resident participation module: pre-construction resident briefings with public minutes; contractor photo/video logs of key construction phases verified by the supervising engineer and viewable by the resident advisory panel; and resident advisory panel attendance at completion and progress inspections with brief public summaries and a simple online dashboard. Precedents include Gwanak-gu, Eunpyeong-gu, Sejong, Namyangju, Paju (briefings); Gyeonggi-do and Gwanak-gu (photo/video logs); and Gwanak-gu and Goyang (inspection attendance). These measures target awareness and procedural trust, which are associated with participation intentions in our data.

- Whistleblower protection protocol: apply the Public Interest Whistleblower Protection Act to defect reports and RPSP activities; provide anonymous intake, non-retaliation notices, separation of identifiers from case files, and time-bound status updates. Several districts explicitly adopt these protections (e.g., Nowon-gu, Dobong-gu, Mapo-gu, Seongdong-gu, Seongbuk-gu, Eunpyeong-gu, Gyeonggi-do, Paju, Jeju City).

- Modular Defect-Prevention Training: Modular defect-prevention training for site supervisors and resident supervisors can be added, drawing on Eunpyeong-gu and Gyeonggi-do provisions. This measure directly targets the professionalism concerns and lack of expertise highlighted in the qualitative analysis.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has methodological constraints. The cross-sectional survey in a single district (Dongjak-gu) with 94 resident representatives, coupled with sparse and heterogeneous administrative participation records, limits causal inference, statistical power, precision, and cross-jurisdiction comparability. The 3-point self-reported measures may attenuate associations and introduce recall, selection, and social desirability bias.

Given the single-district cross-sectional design and the small number of participation events, precision and causal inference are limited. Accordingly, transferability is strongest to urban Korean local governments with similar legal design, low promotion intensity, and trust environments, and weaker where strong fiscal incentives or distinct administrative routines prevail. Readers should assess alignment of institutional design, promotion intensity, and trust conditions before applying these findings.

Future research should employ multi-district comparative and longitudinal designs; randomized or quasi-experimental tests of promotion, transparency, and trust-building interventions; larger samples that include general residents; and link survey constructs to observed behaviors (defect reports, RPSP enrollment and participation). Mediation analyses connecting awareness, procedural trust, perceived efficacy, and participation can also test the proposed mechanisms.

6. Conclusions

In Korea, the legal basis for resident participation in preventing defective construction has been established through higher-level statutes and regulations, with many local governments enacting ordinances to create a legal framework. Nevertheless, records from the defect-reporting program and the RPSP remain minimal, indicating an implementation gap. This study empirically examined that gap, its underlying causes, and potential strategies to overcome it. Using a sequential embedded design, we combined national administrative data with a survey and open-ended responses from resident representatives in Dongjak-gu, a representative case.

The study’s main findings revealed that despite legal frameworks, resident participation scheme performance is poor, and resident awareness is exceptionally low. Critically, the intention to participate was not associated with monetary rewards or direct inconvenience. Instead, it was significantly linked to awareness of the schemes, perceived effectiveness, and normative support for participation. This suggests that residents’ engagement is primarily driven by procedural trust and perceived efficacy, not by simple extrinsic incentives.

These findings provide crucial insights for both theory and practice. Theoretically, they demonstrate that legal adoption of participatory governance is insufficient without mechanisms that build cognitive awareness and procedural trust. Practically, they offer a clear directive for policymakers: to close the implementation gap, efforts must shift away from a focus on monetary incentives and toward active promotion to build awareness, and transparent, reliable procedures to enhance perceived efficacy and institutional trust. Strengthening this trust-based pathway is the key to activating resident participation and improving construction oversight.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.W.K. and D.C.S.; Methodology, E.W.K.; Software, Y.J.S.; Validation, K.J.K.; Investigation, Y.J.S.; Resources, D.C.S.; Data Curation, K.J.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.W.K.; Writing—Review & Editing, N.C. and D.C.S.; Visualization, Y.J.S.; Supervision, D.C.S.; Project Administration, N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University research grant in 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17430433. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Complete Survey Items and Variables

| Category | Variable Name | Survey Question | Response Options | Analysis Coding |

| Experience with Construction & Defects | Nearby construction in the past three years | “Within the past three years, has construction work taken place near your residence?” | Yes/No | 0/1 |

| Suspected defect/inconvenience | “Have you ever suspected construction defects or experienced inconvenience at a construction site?” | Yes/No | 0/1 | |

| Awareness of Resident-participation Schemes | Awareness of defect-reporting program | “Are you aware of the program for reporting construction defects?” | Yes/No | 0/1 |

| Awareness of reward program | “Did you know that a monetary reward is offered for reporting construction defects?” | Yes/No | 0/1 | |

| Awareness of RPSP | “Were you aware of the resident-participatory supervise program?” | Yes/No | 0/1 | |

| Evaluation & Preference | Support for lowering the eligibility threshold | “Should the eligibility threshold for reportable facilities be lowered (e.g., from KRW 300 million)?” | Disagree/ Neutral/ Agree | 0/1/2 |

| Support for expanding the reward program | “The maximum reward by grade is KRW 1,000,000. Do you support increasing it?” | Yes/No | 0/1 | |

| Support for raising the stipend for resident supervisors | “Resident supervisors receive a stipend. Do you think it should be increased?” | Yes/No | 0/1 | |

| Perceived effectiveness of the scheme | “Do you think the ordinance is implemented effectively to prevent construction defects?” | Ineffective/ Neutral/ Effective | 0/1/2 | |

| Perceptions & Participation Intention (Outcome) | Support for resident participation | “How do you view resident participation in supervise?” | Oppose/ Neutral/ Support | 0/1/2 |

| Intention to participate as a resident supervisor | “Would you be willing to participate as a resident supervisor in the future?” | No/ Unsure/ Yes | 0/1/2 |

References

- Adam, C. (2025). More policies, more work? An epidemiological assessment of accumulating implementation stress in the context of german pension policy. Regulation & Governance, 19(3), 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka, Z., & Rosane, H. (2019). Defects in newly constructed residential buildings: Owners’ perspective. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 37(2), 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, C., & Blume, L. B. (2025). Theorizing architectural research and practice in the metaverse: The meta-context of virtual community engagement. International Journal of Architectural Research, 19(1), 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A., Loureiro, A. I. S., & Almendra, R. (2024). Community engagement in the management of urban green spaces: Prospects from a case study in an emerging economy. Urban Science, 8(4), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busan Metropolitan City Nam-gu. (2025). Busan metropolitan city Nam-gu ordinance on the prevention of faulty construction work. Official Local Ordinance Portal. Available online: https://www.elis.go.kr/alrpop/alrDtlsPop?alrNo=26290116000027&histNo=001 (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Korean)

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, M., Cucari, N., Zannoni, A., Laviola, F., Monda, A., Liberato Lo Conte, D., Schilleci, P., Girma Haylemariam, L., & Mare, S. M. (2025). Micro-municipal administration: A review and network-based framework. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 38(4), 448–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, L., Mulligan, J., Oloo, M. A., Guthmann, L., Raido, M., & Ndezi, T. (2022). Co-building trust in urban nature: Learning from participatory design and construction of nature-based solutions in informal settlements in east Africa. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 4, 927723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkul, M., Yitmen, I., & Çelik, T. (2016). Stakeholder engagement in mega transport infrastructure projects. Procedia Engineering, 161, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanberger, A. (2001). What is the policy problem? Methodological challenges in policy evaluation. Evaluation, 7(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C., Nyaranga, M. S., & Hongo, D. O. (2022). Enhancing public participation in governance for sustainable development: Evidence from Bungoma county, Kenya. SAGE Open, 12(1), 21582440221088855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgers, D., & Christoph, I. (2010). Citizensourcing: Applying the concept of openinnovation to the public sector. International Journal of Public Participation, 4(1), 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, K., Wicki, M., & Kaufmann, D. (2024). Public support for participation in local development. World Development, 178, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B., Hunter, D., & Peckham, S. (2019). Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: Can policy support programs help? Policy Design and Practice, 2(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, O. S., & Dindler, C. (2014). Sustaining participatory design initiatives. International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 10(3–4), 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S., Lee, J. S., & Kim, S. (2024). citizen oversight of public spaces: Evaluating public participation in managing privately owned public spaces. Urban Affairs Review, 61(4), 1071–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Legislation Research Institute. (2023). Act on contracts to which a local government is a party. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=62665&lang=ENG (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Korea Legislation Research Institute. (2024). Enforcement decree of the act on contracts to which a local government is a party. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=65546&lang=ENG (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Kumar, R., Singh, R., Goel, R., Singh, T., Priyadarshi, N., & Twala, B. (2024). Incentivizing green building technology: A financial perspective on sustainable development in India. F1000Research, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambers, R., Lamari, F., Skitmore, M., & Rajendra, D. (2025). Key residential construction defects: A framework for their identification and correlated causes. Construction Innovation, 24(6), 1425–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. H. Y., Ng, S. T., & Skitmore, M. (2012). Evaluating stakeholder satisfaction during public participation in major infrastructure and construction projects: A fuzzy approach. Automation in Construction, 29, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecca, U., & Mecca, B. (2023). Surfacing values created by incentive policies in support of sustainable urban development: A theoretical evaluation framework. Land, 12(12), 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Government Legislation of Korea. (2025). National law information center. Available online: https://www.elis.go.kr/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport. (2025). Disclosure of top construction companies by defect rulings for multi-family housing, H1 2025. Available online: https://www.molit.go.kr/USR/NEWS/m_71/dtl.jsp?lcmspage=1&id=95090790 (accessed on 28 August 2025). (In Korean)

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety. (2025). Information disclosure portal. Available online: https://www.open.go.kr/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Mitlin, D. (2021). Citizen participation in planning: From the neighbourhood to the city. Environment and Urbanization, 33(2), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P., Li, Y., Zhu, S., Xu, B., & van Ameijde, J. (2023). Digital common(s): The role of digital gamification in participatory design for the planning of high-density housing estates. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 3, 1062336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P., Zhu, S., Li, Y., & van Ameijde, J. (2024). Digitally gamified co-creation: Enhancing community engagement in urban design through a participant-centric framework. Design Science, 10, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladinrin, O. T., Ho, C. M. F., & Lin, X. (2017). Critical analysis of whistleblowing in construction organizations: Findings from Hong Kong. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 9(2), 04516012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Fujii, S. (2023). Civic engagement in a citizen-led living lab for smart cities: Evidence from South Korea. Urban Planning, 8(2), 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L. (2003). Disaster management and community planning, and public participation: How to achieve sustainable hazard. Natural Hazards, 28(2), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, K., McShane, I., Middha, B., & Ruano, J. M. (2021). Exploring the relationship between trust and participatory processes: Participation in urban development in Oslo, Madrid and Melbourne. Nordic Journal of Urban Studies, 1(2), 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, S., & Almazán, J. (2024). Participatory construction and management methods for wooden architecture: The ‘Bauhäusle’ at the university of Stuttgart. The Journal of Architecture, 29(5–6), 688–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingerland, G., Murray, M., Lukosch, S., McCarthy, J., & Brazier, F. (2022). Participatory design going digital: Challenges and opportunities for distributed place-making. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 31(4), 669–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, S., Tahvonen, O., & Kahiluoto, H. (2022). From participation to involvement in urban open space management and maintenance. Sustainability, 14(19), 12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H., Newton, A., Gong, G., & Lin, C. (2021). Social–environmental analysis of estuary water quality in a populous urban area. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 9(1), 00085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliades, M. A., Hadjichambis, A. C., Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Adamou, A., & Georgiou, Y. (2021). A systematic literature review on the participation aspects of environmental and nature-based citizen science initiatives. Sustainability, 13(13), 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wehn, U., & Almomani, A. (2019). Incentives and barriers for participation in community-based environmental monitoring and information systems: A critical analysis and integration of the literature. Environmental Science & Policy, 101, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, F., Knill, C., Steinbacher, C., & Steinebach, Y. (2024). Bureaucratic quality and the gap between implementation burden and administrative capacities. The American Political Science Review, 118(3), 1240–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H., & Hao, S. (2025). Public participation in infrastructure projects: An integrative review and prospects for the future research. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 30(2), 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanti, S., Berkowitz, E., Katz, M., Nelson, A. H., Burnett, T. C., Culhane, D., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Leveraging integrated data for program evaluation: Recommendations from the field. Evaluation and Program Planning, 95, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T., Zang, T., Jiang, J., Yang, X., & Ikebe, K. (2023). Analysis of the influencing factors of social participation awareness on urban heritage conservation: The example of Suzhou, China. Sustainability, 15(3), 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).