Abstract

Although Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) is one of the strategic choices for digital transformation in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), its adoption remains constrained by leadership decision-making that must balance strategic aspirations with resource limitations and organizational inertia. Organizational leadership must face the dynamic and complex characteristics of digital transformation in the knowledge era. Drawing on Complexity Theory and integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Temporal Motivation Theory (TMT), and the Resource-Based View (RBV), this study proposes a conceptual framework reflecting distinct strategic leadership orientations. Following a qualitative approach based on semi-structured interviews with SME leaders and an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) this conceptual framework contributes by reframing GenAI adoption as a complex, nonlinear process rather than a straightforward diffusion model, that includes four strategic profiles (Strategic Adopters, Aspiring Adopters, Opportunistic Adopters, and Operational Stabilizers) that affect a dynamic relationship between three key adoption dimensions: intention, motivation, and resource allocation. SME leaders can benefit from a delimitation of their strategic and operational goals while overcoming adoption barriers.

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving technological landscape, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) face unprecedented opportunities and challenges. To build resilience and foster digital transformation, key factors such as dynamic capabilities, digital inclusion, leadership orientation, and knowledge management play a pivotal role (Sagala & Őri, 2024). Among emerging technologies, Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) stands out for its potential to enhance innovation, productivity, and competitiveness (Dwivedi et al., 2024). Unlike traditional AI, which analyzes existing data, GenAI creates new content in various formats—including text, images, video, or music—based on its training data (Goodfellow et al., 2020). Tools such as DALL-E, Gemini, Claude, and ChatGPT are transforming business approaches to creativity and content development (Mackenzie, 2024).

GenAI enables companies to automate content creation, personalize customer experiences, and prototype ideas rapidly (García-Madurga & Grilló-Méndez, 2023). Its transformative potential spans industries including marketing, design, tourism and entertainment. Yet, its adoption is not without disruption, especially in SMEs, where stable processes and limited resources dominate daily operations (Vial, 2021). Integrating GenAI challenges this stability, requiring strategic decisions about how to incorporate the technology: either through regenerative actions that reconfigure existing practices, or through adaptive actions that integrate GenAI into current structures. These decisions are shaped by organizational leadership (Haile, 2023) behavior, which influences how managers perceive change, mobilize resources, and guide their organizations through uncertainty in strategic processes (Yukl, 2012).

Despite growing interest, GenAI adoption among SMEs remains limited. In Spain, the adoption of AI continues to increase, although it remains modest in comparative terms. According to the latest report by the Observatorio Nacional de Tecnología y Sociedad (ONTSI), 11.4% of companies with 10 or more employees used AI in 2024, representing an increase of 1.8 percentage points compared with 2023 and more than 3 points relative to 2021 (ONTSI, 2025). Despite this upward trend, overall penetration remains limited, particularly among SMEs, which continue to face resource constraints, lack of knowledge, and organizational inertia that hinder broader adoption. These findings reveal the particular difficulties SMEs face when adopting disruptive technologies. While extensive literature exists on technology adoption, a critical gap remains in understanding how leadership behavior influences the adoption of disruptive technologies like GenAI in SMEs digital transformation efforts (Vial, 2021). This is significant because organizational leadership shapes the strategic alignment and digital transformation efforts must face the dynamic and complex (Vial, 2021) interactions among the relevant dimensions of the adoption process (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Barney, 1991; Steel & König, 2006) where multi-causal relationships must be taken into consideration (Peñarroya-Farell et al., 2023). In this vein, Organizational leadership must shift from a hierarchical to a more transformational leadership approach that can accommodate the adaptability required to integrate such technologies effectively. This study addresses this gap by exploring the role of Complexity Leadership Theory (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007) in understanding organizational leadership profiles to guide SMEs in strategic alignment for GenAI adoption.

It aims to generate insights into the interplay between leadership, strategic alignment, and innovation management in the SME context.

With this purpose in mind, the research addresses the following questions:

- To what extent can an organizational leadership perspective shed light on disruptive technology adoption in SMEs?

- To what extent can different organizational leadership profiles explain how SMEs maintain competitiveness while aligning with strategic objectives during the adoption of GenAI?

The next section presents the theoretical framework that underpins the research. By integrating perspectives from technology adoption models, motivational theories, and resource-based frameworks, the study aims to build a comprehensive understanding of how organizational leadership profiles influence GenAI adoption in SMEs.

2. Theoretical Framework: Understanding GenAI Adoption in SMEs

The integration of Generative AI (GenAI) in SMEs represents a transformative shift in business operations, yet its adoption remains complex (Babashahi et al., 2024). Existing research has highlighted resistance to change, technical constraints, and strategic alignment issues as key challenges (Dwivedi et al., 2024; Babashahi et al., 2024; Ooi et al., 2023). While previous studies offer valuable insights into AI implementation, a clearer understanding is needed on how SMEs navigate decisions around disruptive technologies like GenAI.

2.1. Models of Technology Adoption in SMEs

Technology adoption in SMEs has been widely analyzed using models like the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989), which emphasizes perceived usefulness and ease of use (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). Extensions of TAM (e.g., TAM3) have introduced contextual elements such as subjective norms and perceived risk (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). However, TAM has been criticized for overlooking external factors such as competition or regulation (Sun & Zhang, 2006) and for its limited attention to organizational readiness and leadership (Chau & Hu, 2002).

Rogers (2003) proposed the Diffusion of Innovations theory, highlighting early adopters and broad patterns of innovation diffusion. However, it pays less attention to the internal decision-making processes and leadership dynamics within firms.

Temporal Motivation Theory (TMT) (Steel & König, 2006) complements adoption models by emphasizing urgency and motivational factors. SMEs may adopt GenAI when immediate value is perceived (Khan & Khan, 2024), but risks and uncertainties often delay action (Higgins, 2006; Steel, 2007). Strategic planning mitigates these delays: well-defined transformation strategies facilitate faster adoption (Grant & Ashford, 2008), especially when motivational triggers such as training and leadership support are present (Meyer et al., 2022).

From a resource perspective, the Resource-Based View (RBV) (Barney, 1991) offers insights into how internal capabilities like human capital and digital infrastructure support adoption (Pfister & Lehmann, 2022). Dynamic capabilities such as resource reconfiguration (Teece et al., 1997; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000) are especially relevant when adopting emerging technologies.

Consequently, GenAI can be studied based on the effects of each one of the previously mentioned models; however, in dynamic, changing environments arising from the knowledge era and digital transformation efforts, the interactions among technology adoption frameworks, strategic resource management, and the temporal motivations embedded in the models cannot be ignored (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Barney, 1991; Steel & König, 2006).

For example, the motivation for technology implementation can influence perceptions of ease of use or even the perceived usefulness of technology adoption (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008), and conversely, perceptions of adoption can influence motivation (Chau & Hu, 2002; Khan & Khan, 2024). This mutual causality is also observed in the interaction between technology adoption and the strategic vision of resources (Pfister & Lehmann, 2022) and, finally, between the strategic vision of resources and motivation (Rogers, 2003; Grant & Ashford, 2008). In short, the usual linear models do not appear to be adequate for environments such as that of digital transformation and disruptive technologies (Peñarroya-Farell et al., 2023).

In this sense, this work assumes that integrating the three perspectives to achieve strategic alignment in digital transformation actions, such as the adoption of GenAI by SMEs, can be achieved through organizational leadership perspective (Haile, 2023).

2.2. Organizational Leadership and GenAI Adoption in SMEs

The performance of GenAI adoption in SMEs must be linked to support organizational goals. In this vein, from a dynamic capabilities’ lens (Teece, 2018), alignment ensures coherence between intention, motivation, and resource allocation. Organizational leadership (Haile, 2023) has established that developing a business strategy requires an organizational capacity that aligns the organization with strategic objectives. Organizational leadership is a dynamic organizational capability derived from transformational leadership (Millar et al., 2018), drawing on new leadership paradigms, such as distributed or shared leadership, and linked to the Complexity Leadership Theory (CLT) (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). This dynamic organizational capability (Haile, 2023) defines leadership within the organization as a management capacity that enables leaders to establish strategic objectives.

Organizational leadership must manage the complexity and uncertainty arising from the multi-causal interactions among the three adoption perspectives, the inherent characteristics of digital transformation, and the leadership actions involved in the process. This leadership must be able to adapt dynamically to this interaction and establish the appropriate balance of strategic priorities that should emerge from the adoption process. In this sense, the Complexity Leadership Theory allows us to consider organizational leadership as a balance between administrative, adaptive, and enabling processes (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). It proposes a vision of a Complex Adaptive System (CAS) that considers emerging situations, recombination capabilities, and self-adaptation efforts, enabling a shift from hierarchical leadership to a complex interplay between leaders and employees (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007).

2.3. A Complexity-Based Framework for SME Adoption

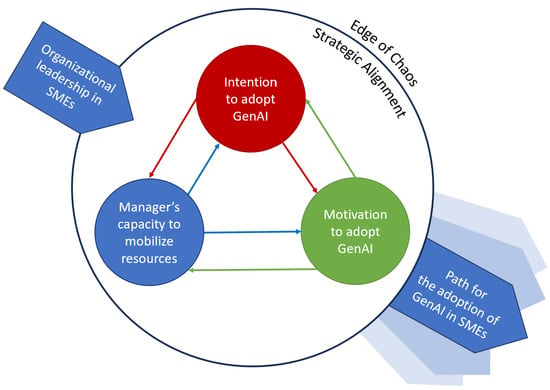

To address these limitations, this study integrates TAM, TMT, and RBV through the lens of Complexity Theory (Holland, 1992; Boulton et al., 2015) to propose a CAS model for Organizational leadership.

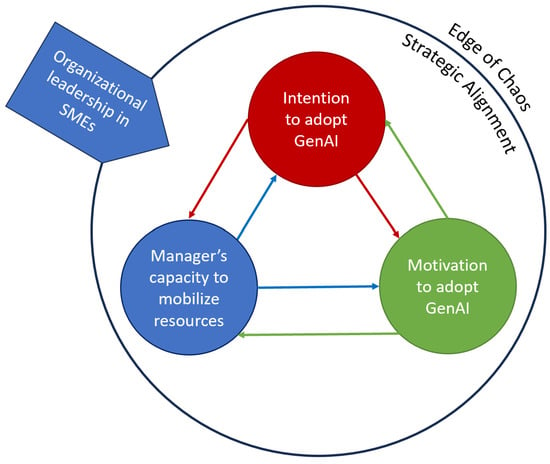

Figure 1 illustrates this complex system, placing strategic alignment as a key enabler that connects individual perceptions (TAM), motivational urgency (TMT), and internal capabilities (RBV). This holistic framework supports the interpretive analysis of SME leadership behaviors, offering deeper insight into the nonlinear nature of GenAI adoption.

Figure 1.

Complex system dynamics of Generative AI adoption in SMEs.

This model assumes that leadership in GenAI adoption can result in either an adaptive or an enabling process (Boulton et al., 2015; Chiva et al., 2010; Holland, 1992). In the first case, the leader adapts the adoption to the company’s characteristics and does not prioritize it. In the second case, the leader facilitates GenAI adoption and transforms the organization for effective alignment with GenAI’s capabilities. In the adaptive approach, the TAM, TMT, and RBV systems will behave in an adaptive manner, while in the enabling approach, all three systems will behave in an enabling manner.

This study presupposes that, contrary to linear adoption models, organizational leadership profiles can emerge from a complex interplay among TAM, TMT, and RBV systems that can lead to adoption behaviors that illustrate specific leadership profiles.

The next section outlines the study’s methodology, data collection, and analysis framework.

3. Methodology

This study examines how leadership behaviors influence GenAI adoption in SMEs while maintaining strategic alignment. Using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Eatough & Smith, 2007), it explores how individuals interpret their experiences (Smith et al., 2009) through a symbolic interactionist lens (Stryker, 2008), identifying both shared patterns and variations. To achieve this, a qualitative approach was employed to capture the complexity of leadership behaviors and decision-making in GenAI adoption. Semi-structured interviews provided rich, contextual insights, revealing patterns in leadership, challenges, and strategic alignment. A cross-sectional design (Bughin & van Zeebroeck, 2017) offers a snapshot of SME leaders’ experiences amid rapid technological change. By examining SMEs across various industries, the interpretivist approach explores leadership perceptions of balancing innovation and stability.

3.1. Data Collection

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews from May to December 2024, conducted face-to-face or via video conferencing based on participant availability. Each session lasted 30–45 min, following a flexible interview guide. The guide, piloted with two managers, included 20 questions exploring leadership strategies, challenges, and perspectives on GenAI adoption while maintaining competitiveness and strategic alignment.

3.2. Sample and Participant Selection

The study used purposive and convenience sampling to recruit 15 strategic leaders from Spanish SMEs across different industries. Participants were selected from an open innovation workshop focused on the use of Generative AI in export and internationalisation functions. This recruitment context explains the predominance of CEOs, Export Managers, and Commercial Directors in the final sample. These roles were deliberately targeted because, in many SMEs, strategic technology- and innovation-related decisions are concentrated in general management and commercial leadership rather than in specialised IT, operations, or finance departments. Consequently, although the sample is not sector-balanced, it reflects the organisational structures typical of SMEs and captures the viewpoints of those who most directly influence early GenAI adoption decisions in the current development state of the adoption of GenAI. Early adoption stage.

Given the exploratory purpose of the study and the emergent state of GenAI adoption in SMEs, a small-N, qualitative design was deemed appropriate. The sample size of 15 participants aligns with qualitative research standards aimed at generating conceptual insight rather than statistical generalisation. The goal was not to achieve industry-level saturation but to identify cross-cutting leadership patterns and behavioural configurations that emerge when SMEs begin engaging with GenAI. While the sample includes organisations with different levels of digital maturity, its composition reflects the participant pool from the workshop rather than a sector-stratified selection.

The over-representation of leaders from commercial and export functions introduces an interpretive bias towards content creation, strategic communication, and customer-facing applications of GenAI. However, this bias mirrors the reality that early adoption within SMEs often originates in management or commercial areas, where experimentation with new technologies is more feasible. This perspective was acknowledged as potentially underrepresenting GenAI applications in technical, operational, or financial processes, yet it nevertheless provided valuable insight into how strategic leaders made sense of GenAI’s potential and constraints within resource-limited environments.

Because the sample spans multiple industries yet remains small, its diversity should be interpreted as providing conceptual breadth rather than sector-specific granularity. This design supports the exploratory aim of identifying leadership-related mechanisms that influence GenAI adoption under heterogeneous organisational conditions. As noted in the limitations, the sectorally diffuse sample and the focus on roles linked to strategic and internationalisation functions constrain the transferability of the findings. Future studies could enhance the interpretive depth by incorporating operational and technical leaders and by using sector-focused sampling strategies. (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of Interviewed Managers.

In addition to the variables reported in Table 1, contextual information was collected to support interpretation of the findings. This included the approximate size of each firm (number of employees) and an assessment of its digital maturity level, derived from participants’ descriptions of existing tools, processes, and prior digital transformation initiatives. These contextual descriptors were not central to the study’s aims and are not presented in table format, but they were considered during the interpretive process to avoid overgeneralisation and to ensure that leadership behaviours were contextualised within each firm’s structural and technological conditions.

3.3. Data Analysis Tool

Data were analysed using a qualitative, interpretive approach informed by elements of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Smith et al., 2009), combined with thematic analysis techniques (Braun & Clarke, 2006). While IPA traditionally prioritises in-depth, idiographic examination of a small number of homogeneous participants, the present study adopted a partial and adapted use of IPA. Specifically, IPA was employed to guide the interpretive orientation of the analysis, focusing on how SME leaders make sense of GenAI adoption, while thematic analysis supported the identification of cross-case patterns across a heterogeneous sample.

Each interview was first analysed individually to preserve the idiographic sensitivity characteristic of IPA, allowing the researchers to capture the personal meaning-making processes expressed by each participant. Subsequently, codes and emergent concepts were compared across cases to identify shared themes. This configurational, cross-case stage departs from a strict IPA design but was considered appropriate given the exploratory aims of the study and the need to understand leadership behaviour across SMEs operating in diverse contexts.

This hybrid analytical strategy aligns with the study’s objective of uncovering leadership patterns rather than conducting a purely phenomenological reconstruction of each individual case. The approach preserves the interpretive depth of IPA while enabling a broader thematic synthesis. As acknowledged in the limitations section, this methodological adaptation represents a partial fit with IPA’s idiographic principles and reduces the depth traditionally associated with full IPA, but it provides an analytically coherent foundation for exploring leadership behaviours in early-stage GenAI adoption among SMEs.

Given the interpretive nature of the study, reflexivity was incorporated throughout the analytical process. The lead researcher and one of the coauthors have extensive professional experience in digital transformation and AI adoption in SMEs, which offers informed sensitivity but also potential biases in interpreting participants’ accounts. To mitigate this risk, reflexive notes were kept during coding, interpretations were cross-checked among co-authors, and participants were invited to review interview summaries to validate accuracy. These procedures aimed to ensure transparency and reduce the influence of prior assumptions on the development of themes and leadership patterns.

3.4. Data Analysis

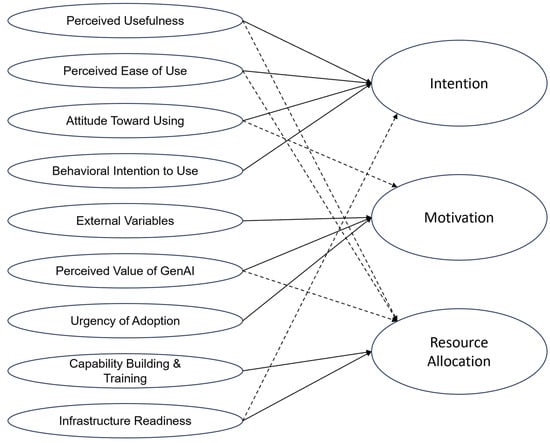

Using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), recurring topics were classified within the study’s theoretical framework. The key categories identified include Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, Attitude Toward Using, Behavioral Intention to Use, External Variables, Perceived Value of GenAI, Urgency of Adoption, Capability Building and Training, and Infrastructure Readiness. Figure 2 illustrates the nine categories and their relationship with the three main themes: Intention, Motivation, and Resource Allocation. As organizations function as complex systems (Anderson, 1999), several categories influence more than one theme, reflecting the interconnected nature of AI adoption. Solid lines indicate primary relationships, while dashed lines represent indirect influences, underscoring the dynamic and interdependent nature of decision-making. In line with recent literature, these interdependencies also reflect processes of mutual causality among technology adoption constructs, motivational mechanisms, and resource-based conditions (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008; Chau & Hu, 2002; Pfister & Lehmann, 2022). Motivation can shape perceptions of usefulness and ease of use, just as these perceptions can enhance or inhibit motivation; similarly, resource strategies influence motivational readiness and are themselves shaped by evolving adoption practices. Such reciprocal interactions highlight that linear models are insufficient for explaining adoption dynamics in contexts characterised by digital transformation and disruptive technologies, reinforcing the need for a complexity-informed interpretation of the data.

Figure 2.

Thematic map of key themes and their relationships. Solid lines indicate primary relationships, while dashed lines represent indirect influences.

4. Findings

4.1. Intention to Use GenAI Strategically in Their Companies

The intention analysis identified four key categories: (a) Attitude toward using GenAI, (b) Perceived ease of use, (c) Perceived usefulness, and (d) Behavioral intention to use. The results reveal a divide between leaders who view GenAI as a strategic necessity and those who remain doubtful or hesitant about its integration. A significant portion of leaders (f13, where f represents frequency) consider GenAI fundamental for business efficiency, reflecting strong confidence in its potential to enhance productivity and competitiveness.

“We see GenAI as a fundamental tool for managing large amounts of data efficiently.”(Manager 8)

“It will be as transformative as YouTube was for learning. GenAI adoption will grow exponentially as more people realize its value.”(Manager 4)

Manager 4 also views GenAI as “the next generational shift akin to the Industrial Revolution,” reflecting her strong belief in its transformative potential. However, a considerable number of managers (f9) express skepticism, suggesting uncertainty about its practical benefits or feasibility.

“The company has a strong innovation culture, implementing major technological advances. However, we are hesitant to adopt GenAI due to fears of losing control over proprietary information.”(Manager 7)

Some leaders (f4) take a more cautious stance, viewing GenAI merely as a complement rather than a transformative tool, which may limit its adoption to supporting rather than reshaping business processes. Others confess using it at a personal level but not strategically for their companies (f3).

“At a personal level, I have used ChatGPT, but we have not implemented it in the company.”(Manager 2)

Additionally, resistance from senior employees (f3) indicates internal barriers that could hinder implementation, emphasizing the impact of organizational culture and workforce adaptation on the adoption process. Age appears to be a factor in this resistance, as highlighted by Manager 12:

“Younger employees, particularly in marketing and sales, are more open to it.”(Manager 12)

Younger professionals, especially in tech-driven roles, are more likely to embrace GenAI, while older employees may resist due to unfamiliarity, usability concerns (Venkatesh et al., 2003), risk aversion (Morris & Venkatesh, 2000; Babashahi et al., 2024), and job security fears (Bélanger & Carter, 2008). Rogers’ Diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers, 2003) suggests younger employees adopt new technologies faster, whereas older workers benefit from structured training and leadership support (Zacher & Rosing, 2015). Adoption success depends on balancing accessibility with proper education and oversight, as some find GenAI intuitive (f7), while others see a need for supervision (f5) or additional training (f5).

“For our daily use, AI tools are intuitive. Once we understand how to phrase queries, the experience becomes seamless.”(Manager 3)

“Yes, it’s intuitive. The only challenge is verifying accuracy, as GenAI sometimes generates misleading information.”(Manager 11)

The need for learning may also reflect the evolving nature of GenAI tools, requiring continuous adaptation as capabilities expand. Additionally, access to advanced training materials provided by GenAI developers themselves may present a linguistic barrier. Manager 13 highlighted this challenge, noting that most documentation and learning resources for Gemini AI were only available in English:

“Much of the technical information is only available in English, making the learning curve steeper.”(Manager 13)

This suggests that non-English-speaking users may face additional obstacles when trying to deepen their expertise, potentially slowing down adoption and limiting the full exploitation of GenAI’s capabilities.

Interestingly, it was observed that those who used GenAI less frequently found it easier to use, while more experienced users felt they needed further training. This aligns with the Dunning-Kruger Effect (Kruger & Dunning, 1999), where lower-competence individuals overestimate their abilities, while experts recognize knowledge gaps. Rogers’ (2003) diffusion of innovations theory similarly suggests that early adopters may not fully grasp a technology’s complexities until deeper engagement reveals challenges.

The most cited GenAI application was content creation (f12), widely used for marketing, emails, and reports. Translations (f6) and marketing and sales (f6) also emerged as key uses, particularly in multilingual and international business contexts.

“I use GenAI extensively in export operations. It helps with translations, email structuring, and generating marketing ideas.”(Manager 4)

Beyond these primary functions, GenAI is also recognized for its role in automating administrative tasks (f3), supporting market research (f3), and managing documents (f2), reflecting its utility in enhancing efficiency by handling repetitive processes and structuring business information. Some businesses have also begun exploring its potential in customer support (f1), financial analysis (f1), and e-Commerce (f1), while others see value in its ability to aid in business presentations (f1), idea validation (f1), and decision-making (f1). However, the data also reveals some hesitation regarding its reliability. While many acknowledge its usefulness, one participant explicitly noted that GenAI is “useful but not reliable” (f1) (Manager 9), suggesting concerns about accuracy or consistency, while another stated that they saw “no use in production” (f1) (Manager 5), indicating skepticism about its applicability in core business operations.

“GenAI is useful for administrative tasks, but when it comes to the production floor, I simply don’t trust it and I don’t see how it can help us.”(Manager 5)

The findings indicate that while GenAI enhances content creation and efficiency, trust in its output’s limits adoption in strategic areas. Many businesses (f6) report no formal AI implementation, reflecting uncertainty, resource constraints, or a lack of strategic direction. In some cases, employees drive adoption (f5), experimenting with GenAI without direct leadership involvement. This bottom-up adoption suggests a leadership gap, where managers either overlook GenAI’s potential or hesitate to integrate it into strategy. Manager 2, an export manager in agrifood, exemplifies this—using GenAI personally while higher management resists innovation, relying on traditional, paper-based methods.

For some companies, financial constraints hinder adoption, with some seeking funding for implementation (f2) and others for training (f2). While these businesses see GenAI’s potential, cost remains a major barrier to scaling efforts. Findings suggest that interest in GenAI is high, but structured adoption is limited. Employee-driven use highlights a grassroots approach, while financial constraints slow broader adoption. For some SMEs, investment in infrastructure and training is essential to move beyond experimental use.

4.2. Motivation to Use GenAI in Their Companies

The motivation analysis revealed three major categories: (a) External variables affecting the implementation, (b) Perceived Value of GenAI, and (c) Urgency to implement GenAI. Despite the growing discourse around GenAI, no participant reported feeling pressured by competitors to implement it (f15). While media coverage had prompted some to experiment with the technology (f4), this was driven by curiosity rather than competitive necessity. Most respondents doubted that their competitors were using GenAI beyond basic content creation, and many believed that even this application was not widespread.

“I’ve noticed better-written texts from my competitors on LinkedIn, but I doubt they’re using GenAI for anything else.”(Manager 1)

The lack of perceived competitive pressure suggests that businesses do not yet see GenAI as a critical differentiator, potentially underestimating its long-term impact. However, Manager 10, CEO of the translation services, showcased the decline in business due to GenAI-based translation solutions.

“We have seen a decline in business as some clients have shifted to GenAI-based translation solutions instead of using our services.”(Manager 10)

This reflects a competitive shift driven by client behavior rather than industry peers, indicating that some sectors may experience disruption sooner than others. This aligns with Christensen’s (1997, 2013) Disruptive Innovation Theory, which explains how emerging technologies can displace traditional service providers by offering cheaper and more scalable alternatives. In this case, GenAI acts as a substitute technology (Bower & Christensen, 1995), replacing human translation for many routine tasks, thereby reducing the demand for professional translators. As a result, businesses in the translation sector must reconsider their strategic positioning.

While many SMEs do not yet perceive direct competition from GenAI adopters, market dynamics and changing customer expectations could accelerate the urgency for adoption, particularly in industries where GenAI serves as a direct substitute rather than a complement. The most cited benefit is improving efficiency (f8), showing that decision-makers view GenAI as a tool to streamline operations and reduce workload. Boosting productivity (f5) follows, reinforcing AI’s role in increasing output without added costs.

“It saves me significant time, especially in structuring emails and generating multilingual campaigns.”(Manager 4)

Improving creativity (f2) is mentioned less often, suggesting that SMEs focus more on GenAI’s practical applications than on its potential for innovation. Similarly, competitive advantage (f1) and internal transformation (f1) are rarely cited, indicating that most leaders see GenAI as a tool for incremental improvements rather than business model innovation.

These findings suggest that the primary motivation for adopting GenAI in SMEs is rooted in efficiency and productivity gains, rather than in transformative change. While a few companies see GenAI as a competitive differentiator, most seem to perceive it as a supporting tool rather than a strategic game-changer. This aligns with broader trends in SME digital adoption, where resource constraints and risk management often lead to gradual and pragmatic implementation rather than radical shifts in business operations (Mohamed & Weber, 2020).

Personal motivation (f7) is the primary driver of GenAI adoption, with external pressures playing a lesser role. Many participants do not see GenAI as an immediate priority (f 5), though some acknowledge growing urgency (f4), aligning with Temporal Motivation Theory (Steel & König, 2006), which links urgency to perceived proximity and expected value. Few leaders (f2), such as Manager 10 in translation services, see GenAI as a necessity, aligning with Perceived Strategic Urgency Theory (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000), where adoption is critical for survival.

Findings suggest GenAI adoption in SMEs remains voluntary, not necessity driven. Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) explains this reluctance: firms act more on imminent threats than potential gains. While urgency is rising for some, most SMEs still view GenAI as optional, potentially slowing widespread adoption.

4.3. Resource Allocation for GenAI in SMEs

The analysis of the Resource Distribution for GenAI revealed two major categories: (a) Resource Mobilization for Capability Building and Training, and (b) Infrastructure Readiness. The most frequently mentioned need is general GenAI training (f10), suggesting that many companies recognize a knowledge gap and seek foundational understanding. Additionally, specialized training in Sales and Marketing (f5) and International Expansion (f5) indicates a demand for GenAI education tailored to specific business functions.

“I recently reviewed an GenAI training course, but it seemed too technical for our sales team, so I didn’t proceed with it.”(Manager 12)

Meanwhile, a few companies are seeking funding for training (f4), reinforcing resource constraints may limit structured learning opportunities. GenAI automation (f1) appears as a niche training need, indicating that only a few businesses are considering deeper automation strategies. While training needs are widely acknowledged, many SMEs rely on self-learning through YouTube videos and other informal resources, as systematic and structured training programs remain scarce.

“I am starting to take some free online courses to better understand how it works.”(Manager 15)

This suggests that while interest in GenAI education is growing, access to high-quality, tailored training remains a challenge for SMEs, potentially slowing adoption and effective implementation. Infrastructure Readiness (IR) refers to the extent to which an organization possesses the necessary technological resources to effectively integrate and utilize artificial intelligence. This includes elements such as computing power, data storage, networking capabilities, and specialized GenAI tools. Within this framework, paid GenAI is not merely an auxiliary function but a critical component of a company’s infrastructure. The data reveals that a majority of businesses (f7) are not yet ready, indicating that technological limitations, lack of IT support, or outdated systems may hinder adoption. However, some companies (f5) are actively working on readiness, suggesting a transition phase where businesses recognize the need for upgrades but have not yet fully implemented them. Only a small number of SMEs (f3) report being fully prepared, highlighting that few businesses have the necessary infrastructure in place for seamless GenAI integration.

These findings suggest infrastructure is a major bottleneck in GenAI adoption, with technical barriers slowing implementation despite high motivation and perceived usefulness. Limited IT resources and digital transformation challenges hinder SMEs’ ability to leverage GenAI effectively. From a Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), digital infrastructure is a strategic asset, but financial constraints and a lack of AI talent (Rietmann, 2021) create a digital divide, favoring well-resourced firms. Without targeted investment, SMEs risk falling behind in AI-driven markets.

5. Discussion

5.1. Leadership Behavior and Disruptive Technology Adoption in SMEs

Addressing Research Question 1, the findings indicate that GenAI adoption in SMEs arises from the interaction among leaders’ intention, motivation, and resource allocation, rather than from their linear influence. This supports complexity-based views of organizational change, which conceptualize digital transformation as a nonlinear and interdependent process (Anderson, 1999; Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). Leadership behavior shapes GenAI adoption not by acting on isolated drivers but by influencing how these dimensions evolve together as part of a complex adaptive system.

From a technology acceptance perspective, perceived usefulness and ease of use (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000) do play a role, but the findings show that positive perceptions alone are insufficient. Their effect depends on the firm’s resource base and dynamic capabilities (Barney, 1991; Teece et al., 1997; Vial, 2021). Leaders often recognize GenAI’s value yet postpone adoption due to limited skills, IT readiness, or budget constraints, illustrating how TAM variables become conditioned by structural factors emphasized in the RBV.

Motivational mechanisms also contribute to this configuration. In line with Temporal Motivation Theory (Steel & König, 2006; Steel, 2007), urgency and perceived value interact with leaders’ risk perceptions. When urgency is low, even strong positive attitudes do not lead to action; when urgency increases, due to market pressures or operational needs—adoption may occur despite capability gaps. These findings reflect the temporal trade-offs that characterize SME decision-making (Higgins, 2006; Bughin & van Zeebroeck, 2017).

Complexity Leadership Theory offers an integrative explanation. Leaders operate across administrative, adaptive, and enabling roles (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007), and GenAI adoption is more advanced in firms where leadership fosters experimentation, learning, and capability development. Conversely, when leadership favors stability and control, adoption remains incremental or symbolic. This highlights that leadership influences not only attitudes or resources but the alignment among intention, motivation, and capabilities, which is essential in dynamic digital environments (Vial, 2021; Teece, 2018).

Overall, the results show that leadership behavior in SMEs functions as a coordinating mechanism that shapes the interplay of cognitive (TAM), motivational (TMT), and resource-based (RBV) elements. GenAI adoption becomes viable when these elements reinforce each other, rather than operate independently. This extends traditional adoption models by positioning leadership as the central factor that determines whether GenAI remains a peripheral tool or evolves into a driver of strategic renewal.

5.2. Leadership Profiles and the Dynamics of GenAI Adoption in SMEs

Table 2 provides the first integrative overview of how each manager in the study approaches GenAI across the nine analytical categories identified earlier in the thematic analysis. These categories, covering intention elements (Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, Attitude, Behavioral Intention), motivation elements (External Variables, Perceived Value, Urgency), and resource elements (Capability-Building and Infrastructure Readiness), are coded as either adaptive or regenerative. This classification reflects whether leaders engage with GenAI through incremental, risk-sensitive behaviors or through a future-oriented, transformative stance grounded in exploration and capability expansion.

Table 2.

Leadership approach classification.

It brings together the three theoretical lenses guiding the study. From a TAM perspective (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), adaptive vs. regenerative variation in usefulness and ease-of-use perceptions helps explain differences in technological intention and acceptance. The TMT dimension (Steel & König, 2006) is visible in how managers’ urgency and value perceptions combine to either motivate or delay adoption. Finally, the RBV perspective (Barney, 1991) is evident in the resource categories, where capability-building and infrastructure readiness impose clear constraints that shape leaders’ overall orientation.

On the other hand, it shows that no manager demonstrates a fully regenerative profile across all nine categories. Even leaders with strong transformative intentions often show adaptive behavior in resource-related categories, highlighting capability gaps common in SMEs (Pfister & Lehmann, 2022; Vial, 2021). This suggests that enthusiasm for GenAI does not automatically translate into investment, readiness, or strategic commitment, a finding consistent with early-stage diffusion conditions.

Ultimately, Table 2 serves as the analytical bridge between the individual-level coding and the four broader leadership patterns synthesized later in Table 6. By displaying how adaptive and regenerative behaviors cluster differently among managers, it becomes possible to trace how distinct configurations of intention, motivation, and resources give rise to the Strategic, Aspiring, Opportunistic, and Operational leadership profiles. It therefore plays a foundational role in transitioning from thematic codes to configuration-based theoretical interpretation.

The emergence of the four leadership profiles, Strategic Adopters, Aspiring Adopters, Opportunistic Adopters, and Operational Stabilizers, reflects the configurational interplay among intention (Table 3), motivation (Table 4), and resource allocation (Table 5). Rather than aligning with the sequential adopter categories proposed by Rogers (2003), these profiles arise from the non-linear, multi-causal interactions between leaders’ perceptions rooted in TAM (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), their assessments of urgency and value consistent with TMT (Steel & König, 2006; Steel, 2007), and the organization’s capabilities as described by the RBV and dynamic capabilities perspectives (Barney, 1991; Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2018). Drawing on Complexity Theory (Anderson, 1999) and Complexity Leadership Theory (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007), these leadership patterns can be understood as emergent states within a complex adaptive system, where leadership behavior, resource constraints, and perceived opportunities co-evolve. This lens helps explain not only why these four profiles form, but also how they stabilize or shift over time as feedback loops between intention, motivation, and capability development reinforce or alter adoption trajectories.

Table 3.

Summary of Intention Category (TAM-Aligned Variables).

Table 4.

Summary of Motivation Category (TMT-Aligned Variables).

Table 5.

Summary of Resource Allocation Category (RBV-Aligned Variables).

Strategic Adopters exhibit regenerative perceptions and behaviors across all three tables: high perceived usefulness and ease of use (Table 3), strong value-based motivation and urgency (Table 4), and proactive capability-building and infrastructure investment (Table 5). While these leaders resemble “innovators” in Rogers’ diffusion model, their trajectories are better explained by dynamic capabilities theory (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2018). Early investment reduces uncertainty, strengthens perceived value (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), and creates reinforcing loops in which resources, learning, and motivation amplify one another. Complexity theory conceptualizes this configuration as a high-change attractor, where experimentation and capability development reinforce strategic renewal.

Aspiring Adopters show regenerative intention in Table 3 but stronger constraints in motivational drivers (Table 4) and resource allocation decisions (Table 5). This creates a resource–motivation feedback loop (Steel & König, 2006; Higgins, 2006): limited resources reduce urgency, weakened urgency delays investment, and capability gaps reinforce hesitation (Barney, 1991; Pfister & Lehmann, 2022). Unlike Rogers’ “early majority,” who progress through predictable stages, these leaders operate within a fragile, path-dependent equilibrium. Complexity theory suggests that small interventions, policy incentives, market pressures, and access to shared digital infrastructures can shift their pattern toward Strategic Adopters, while persistent constraints can lock them into stagnation.

Opportunistic Adopters present adaptive intention (Table 3) and tactical motivation (Table 4), with selective and localized investment decisions (Table 5). Their behavior is less aligned with Rogers’ “early majority” and more consistent with local optimization within complex systems: immediate operational needs, symbolic pressures, or short-term opportunities shape adoption choices (Bughin & van Zeebroeck, 2017; Vial, 2021). Because these choices are not anchored in strategic alignment, they yield fragmented innovation, with isolated experiments seldom scaling into organization-wide transformation. Complexity theory describes this as a shallow adoption attractor, where movement is dynamic but non-transformative unless leaders link operational experimentation to strategic learning processes.

Operational Stabilizers exhibit adaptive intention, low motivational intensity, and minimal resource commitment across the three tables. While superficially resembling Rogers’ “late adopters,” their behavior is grounded in path dependence and self-reinforcing constraints: low perceived usefulness suppresses motivation, limited investment undermines IT readiness, and weak readiness validates initial perceptions (García-Madurga & Grilló-Méndez, 2023). Complexity theory frames this as a low-change attractor state, where the system stabilizes around non-adoption. Only significant external shocks, regulatory changes, competitive pressures, or structural policy interventions are likely to break this cycle.

Table 6 synthesizes how intention (Table 3), motivation (Table 4), and resources (Table 5) combine into the four leadership profiles. Importantly, these profiles should not be interpreted as fixed categories or natural stages. Complexity theory highlights that leadership configurations behave as dynamic states: firms may shift from one profile to another as perceptions evolve, resources are reconfigured, or environmental pressures intensify. This configurational view extends classical models, TAM (Davis, 1989), TMT (Steel & König, 2006), RBV (Barney, 1991), and Rogers’ diffusion theory, by showing that SME GenAI adoption emerges through iterative feedback loops rather than linear, predictable sequences.

The configurational analysis presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 shows that the four leadership profiles emerge from the interaction of intention, motivation, and resource allocation. These patterns are not linear stages of adoption, nor do they align with Rogers’ (2003) classical adopter categories. Instead, they represent complex adaptive states (Anderson, 1999), shaped by ongoing feedback between leadership behavior, organizational conditions, and emerging opportunities. Viewed through Complexity Leadership Theory (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007), these profiles illustrate how leadership actions and resource constraints co-evolve over time, producing distinct and dynamic pathways for GenAI adoption in SMEs.

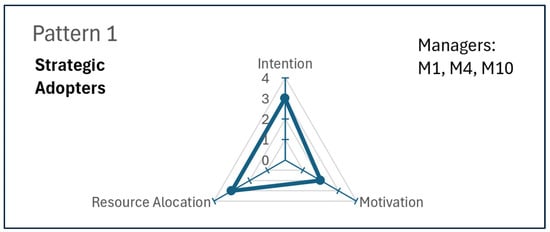

Pattern 1: Strategic Adopters. Figure 3 visualizes a configuration where regenerative intention, strong motivation, and proactive resource allocation co-evolve. Although these leaders resemble Rogers’ “innovators,” their behavior is best understood through the lens of dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2018). Early investments reduce uncertainty, strengthen perceived usefulness and ease of use (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), and create positive reinforcement cycles. The values correspond to the leadership approach in each dimension: 4 = Full Regenerative, 3 = Mid Regenerative, 2 = Mid Adaptive, and 1 = Full Adaptive. Complexity theory conceptualizes this as a high-change attractor, where experimentation, capability-building, and strategic alignment reinforce one another, accelerating transformation.

Figure 3.

Strategic innovator s pattern.

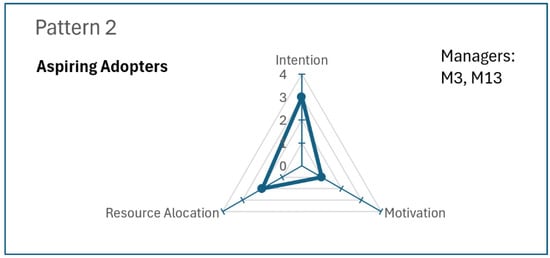

Pattern 2: Aspiring Adopters. Figure 4 illustrates a leadership configuration defined by regenerative intention but constrained motivation and capability gaps. This pattern reflects a resource–motivation feedback loop (Steel & König, 2006; Higgins, 2006): limited resources suppress urgency, lower urgency delays investment, and delayed investment reinforces the capability deficit (Barney, 1991; Pfister & Lehmann, 2022). Complexity theory explains this as a fragile equilibrium, a system easily shifted by small triggers (external incentives, client demands, shared tools) but equally prone to stagnation if constraints remain unresolved. This pattern does not directly correspond to Rogers’ framework but emerges as a distinctive leadership behavior within the complex systems perspective. Their presence highlights that GenAI adoption in SMEs is not purely a matter of intention but also of systemic readiness and resource mobilization (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Aspiring adopter’s pattern.

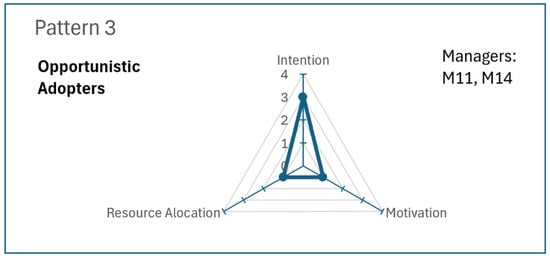

Pattern 3: Opportunistic Adopters. These leaders exhibit a high intention to adopt GenAI but lack intrinsic motivation and do not allocate sufficient resources for its implementation. Figure 5 depicts leaders who apply GenAI tactically to localized operational tasks rather than as part of strategic transformation. Rather than aligning with Rogers’ “early majority,” their behavior reflects local-optimization dynamics typical of complex systems. They pursue small, low-risk wins shaped by immediate pressures (Bughin & van Zeebroeck, 2017; Vial, 2021), but these isolated experiments rarely scale unless intentionally linked to organizational learning. This forms a shallow adoption attractor, where innovation is dynamic but lacks depth and integration. Rather than being true pioneers of digital transformation, these organizations engage in what could be considered symbolic adoption, demonstrating interest in GenAI without the necessary groundwork for meaningful integration. As a result, their efforts may stagnate, reinforcing the paradox where digital investments fail to translate into tangible competitive advantages (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Opportunistic adopter’s pattern.

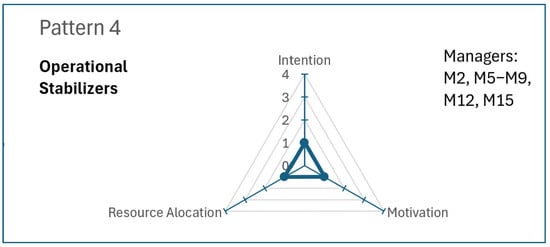

Pattern 4: Operational Stabilizers. These leaders follow a fully adaptive approach. They do not prioritize GenAI as a driver of change; instead, they focus on maintaining operational efficiency with minimal disruption. Figure 6 represents a configuration dominated by adaptive intention, low motivation, and minimal resource allocation. Although similar to late adopters, their inertia is driven less by resistance and more by path dependence and reinforcing loops: low perceived usefulness reduces motivation to invest, limited investment depresses IT readiness, and low readiness confirms leaders’ initial perceptions (García-Madurga & Grilló-Méndez, 2023). Complexity theory frames this as a low-change attractor, where small interventions have limited effect unless accompanied by external shocks or significant structural support.

Figure 6.

Operational Stabilizers” pattern.

While Rogers’ diffusion model remains a useful foundation, it lacks the nuance to fully capture the diversity of leadership behavior in GenAI adoption. Our analysis shows that early-stage adopters are not homogeneous, and crossing Moore (1991) Chasm requires more than technological readiness; it requires strong leadership, strategic clarity, and capability development.

Leadership is not a passive enabler, but an active force shaping the trajectory and depth of GenAI integration. Leaders who align intention, motivation, and resources are more likely to move beyond superficial use and unlock GenAI’s full potential. Conversely, leaders who delay investment or underestimate strategic alignment risk falling into the “digitalization paradox”, where adoption fails to deliver value.

Understanding these differentiated leadership behaviors equips practitioners and policymakers to better support SMEs by tailoring interventions to their specific stage and readiness in the adoption journey.

Beyond explaining how these configurations emerge, the typology also carries important managerial and theory-testing implications. From an organizational perspective, each profile reflects a distinct readiness path: Strategic Adopters illustrate how early investment and clear value articulation accelerate adoption; Aspiring Adopters demonstrate the need for targeted capability-building to overcome motivational and resource bottlenecks; Opportunistic Adopters highlight the risks of fragmented experimentation without strategic alignment; and Operational Stabilizers show how path dependence can limit technological renewal unless externally prompted. These profiles, therefore, help managers diagnose their organization’s current position and identify levers, such as urgency framing, skill development, or infrastructural upgrading, that could shift them toward more transformative trajectories. From a theoretical standpoint, the typology provides a foundation for future testing by offering empirically grounded configurations that can be operationalized using TAM, TMT, and RBV constructs and validated through comparative designs such as fsQCA or larger-scale quantitative studies. This underscores the typology’s potential not only as an interpretive lens but as a framework for cumulative theory building in the context of GenAI adoption in SMEs.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how SME leaders approach the adoption of Generative AI within the broader digital transformation challenges outlined in the Introduction. Consistent with prior work emphasizing the disruptive nature of GenAI and the structural limitations that SMEs face (Dwivedi et al., 2024; ONTSI, 2025; Vial, 2021), the findings show that adoption emerges from the interdependence of leaders’ intentions, motivational dynamics, and resource structures. By integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), Temporal Motivation Theory (Steel & König, 2006), the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2018), and complexity theory (Anderson, 1999), the study provides a holistic interpretation of how these elements interact in real SME environments.

The analysis identified four leadership profiles: Strategic Adopters, Aspiring Adopters, Opportunistic Adopters, and Operational Stabilizers, which illustrate that GenAI adoption does not follow linear or sequential pathways but emerges as a set of dynamic configurations shaped by feedback loops between leadership behaviour, perceived opportunities, and capability constraints. This perspective aligns with Complexity Leadership Theory (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007) and contributes theoretically by extending classical adoption models through an understanding of non-linear, emergent adoption dynamics in resource-constrained contexts.

From a managerial standpoint, the implications of the study are intentionally high-level and should be interpreted as orientational rather than prescriptive, given the exploratory qualitative design. The findings indicate that progression in GenAI adoption depends on leaders’ ability to articulate a clear strategic purpose, cultivate a realistic sense of urgency, and foster basic internal capabilities while working within constrained technological and financial resources (Vial, 2021; Teece, 2018). Rather than pursuing advanced or disruptive applications from the outset, SMEs appear to benefit from small-scale experimentation, structured learning, and incremental capability-building that reduce uncertainty and encourage employee engagement. Leadership behaviours that support knowledge sharing, enable experimentation, and integrate GenAI initiatives with existing resources can help shift SMEs from fragmented or ad hoc use to more coherent, strategically aligned adoption patterns, even when resource limitations remain significant. These insights reflect the adaptive, emergent practices observed among the SMEs in this study and align with the complexity-based understanding of digital transformation developed throughout the paper.

The study’s conclusions also reflect the influence of sample composition. Because participants were primarily managers in commercial, marketing, and internationalisation roles, the dominant use cases identified were content creation, translation, and communication tasks. This pattern should not be interpreted as evidence that GenAI’s value is limited to these functions. As highlighted in the Introduction and supported by existing research, GenAI also holds significant potential for forecasting, optimisation, and production-related decision-making (Hofmann et al., 2019; Ivanov & Dolgui, 2021), but these operational contexts were not represented in the dataset.

Overall, this study positions GenAI adoption in SMEs as a context-dependent, non-linear, and evolving process shaped by leadership configurations that emerge through the interaction of intention, motivation, and resource allocation. While the implications must be viewed within the constraints of an exploratory qualitative design, the findings offer a foundation for future research aimed at tracing how leadership configurations shift over time, how sectoral context conditions adoption dynamics, and how SMEs develop the dynamic capabilities needed to integrate GenAI more strategically and sustainably (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Diverse pathways to GenAI adoption in SMEs.

Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study is exploratory and relies on a qualitative, small-N design, which limits the transferability and generalizability of the findings (Smith et al., 2009; Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). As already clarified in Section 3, the study employed a partial and adapted use of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). This adaptation departs from IPA’s idiographic and homogeneous-sample requirements and prioritizes cross-case pattern identification over full phenomenological depth. Such a methodological choice represents a formal limitation, as it affects the interpretive coherence and idiographic richness typically expected in IPA studies, and should be taken into account when interpreting the emergent leadership profiles.

A second limitation concerns the heterogeneity and diffuse nature of the small sample, which included leaders from diverse sectors, functions, and levels of digital maturity. While this heterogeneity enabled the identification of broad leadership configurations, it may also have introduced interpretive bias. In particular, the predominance of participants from commercial, marketing, and internationalisation roles likely contributed to the prominence of content-creation use cases observed in the findings. This sectoral bias constrains the study’s ability to speak to GenAI adoption in operational, manufacturing, logistics, or supply-chain contexts, where GenAI may support forecasting, optimisation, or anomaly detection (Hofmann et al., 2019; Ivanov & Dolgui, 2021). Future studies should consider more targeted, sector-specific sampling strategies to enhance interpretive depth and reduce functional bias.

A third limitation relates to the study’s geographical focus. The sample consists solely of SME leaders operating within the Spanish context, which may limit the applicability of the findings to different institutional, cultural, or regulatory environments. Cross-national comparative work would allow for a deeper understanding of how leadership configurations interact with varying digital maturity levels and policy frameworks (Vial, 2021).

These limitations open several avenues for future research directly connected to the study’s methodological constraints. Future studies could adopt longitudinal qualitative designs to examine how leadership configurations evolve over time as SMEs progress through different stages of GenAI adoption. Alternatively, comparative or mixed-methods approaches, including fsQCA or causal-comparative designs, could provide stronger insight into the configurational conditions under which specific leadership profiles emerge. Finally, sector-focused samples and idiographically coherent IPA studies would allow researchers to deepen understanding of leadership sense-making in specific organizational environments while preserving IPA’s methodological integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.-F., M.V. and F.M.; Methodology, M.P.-F., M.V. and S.K.S.R.; Software, M.P.-F. and M.V.; Validation, M.P.-F. and S.K.S.R.; Formal analysis, M.P.-F. and S.K.S.R.; Investigation, M.P.-F. and M.V.; Resources, M.P.-F.; Data curation, M.P.-F. and M.V.; Writing—original draft, M.P.-F. and F.M.; Writing—review & editing, M.P.-F., M.V., S.K.S.R. and F.M.; Visualization, M.P.-F. and M.V.; Supervision, F.M.; Project administration, F.M.; Funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the ethical procedures of La Salle—Universitat Ramon Llull (Barcelona, Spain), this type of non-experimental qualitative research—based on anonymized voluntary interviews and not involving the collection of personal or sensitive data—does not require formal approval from the university’s Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative data used in this study consist of transcribed interviews that contain contextual and potentially identifiable information. For privacy and ethical reasons, these data cannot be made publicly available. However, the authors are willing to provide access to anonymized excerpts or coding outputs upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, P. (1999). Complexity theory and organization science. Organization Science, 10(3), 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babashahi, L., Barbosa, C. E., Lima, Y., Lyra, A., Salazar, H., Argôlo, M., de Almeida, M. A., & de Souza, J. M. (2024). AI in the workplace: A systematic review of skill transformation in the industry. Administrative Sciences, 14(6), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, F., & Carter, L. (2008). Trust and risk in e-government adoption. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 17(2), 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, J. G., Allen, P. M., & Bowman, C. (2015). Embracing complexity: Strategic perspectives for an age of turbulence. OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995). Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave. Harvard Business Review, 73(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughin, J., & van Zeebroeck, N. (2017). The best response to digital disruption. MIT Sloan. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, P. Y., & Hu, P. J. (2002). Investigating healthcare professionals’ decisions to accept telemedicine technology: An empirical test of competing theories. Information & Management, 39(4), 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, R., Grandío, A., & Alegre, J. (2010). Adaptive and generative learning: Implications from complexity theories. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(2), 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. M. (2013). The innovator’s solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Pandey, N., Currie, W., & Micu, A. (2024). Leveraging ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based applications in the hospitality and tourism industry: Practices, challenges, and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, V., & Smith, J. A. (2007). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In C. Willig, & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 179–194). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Madurga, M.-Á., & Grilló-Méndez, A.-J. (2023). Artificial intelligence in the tourism industry: An overview of reviews. Administrative Sciences, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A., & Bengio, Y. (2020). Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM, 63(11), 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M., & Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, G. A. (2023). Organizational leadership: How much does it matter? British Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(3), 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (2006). Value from hedonic experience and engagement. Psychological Review, 113(3), 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, E., Sternberg, H., Chen, H., Pflaum, A., & Prockl, G. (2019). Supply chain management and Industry 4.0: Conducting research in the digital age. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 49(10), 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J. H. (1992). Complex adaptive systems. Daedalus, 121(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2021). A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Production Planning & Control, 32(9), 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U., & Khan, K. A. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in hospitality and tourism marketing: Perceptions, risks, benefits, and policy implications. Journal of Global Hospitality and Tourism, 3(1), 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, A. H. (2024). Artificial intelligence: Friend or foe? The Science Teacher, 91(2), 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J., de Reuver, M., & Bouwman, H. (2022). Motivational triggers in SME digital transformation: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Small Business & Enterprise Development, 29(3), 403–426. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, C. C., Groth, O., & Mahon, J. F. (2018). Management innovation in a VUCA world: Challenges and recommendations. California Management Review, 61(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N., & Weber, R. (2020). Digital transformation in SMEs: The role of resources and financial constraints in adoption. arXiv, arXiv:2002.11623. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G. A. (1991). Crossing the chasm: Marketing and selling high-tech products to mainstream customers. Harper Business. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M. G., & Venkatesh, V. (2000). Age differences in technology adoption decisions: Implications for a changing workforce. Personnel Psychology, 53(2), 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONTSI. (2025). Indicadores del uso de inteligencia artificial en España 2024 (Edición 2025–Datos 2024). Observatorio Nacional de Tecnología y Sociedad. Available online: https://www.ontsi.es (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Ooi, K.-B., Tan, G. W.-H., Al-Emran, M., Al-Sharafi, M. A., Capatina, A., Chakraborty, A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Huang, T.-L., Kar, A. K., Lee, V.-H., Loh, X.-M., Micu, A., Mikalef, P., Mogaji, E., Pandey, N., Raman, R., Rana, N. P., Sarker, P., Sharma, A., … Wong, L.-W. (2023). The potential of generative artificial intelligence across disciplines: Perspectives and future directions. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 65, 76–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñarroya-Farell, M., Miralles, F., & Vaziri, M. (2023). Open and sustainable business model innovation: An intention-based perspective from the Spanish cultural firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(2), 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, P., & Lehmann, C. (2022). Digital value creation in German SMEs—A return-on-investment analysis. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 36(4), 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne—Psychological Journal, 20(1), 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietmann, C. (2021). Digital pioneers in the periphery? Toward a typology of rural hidden champions in times of digitalization. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 36(2), 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sagala, G. H., & Őri, D. (2024). Exploring digital transformation strategy to achieve SMEs resilience and antifragility: A systematic literature review. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 37, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P., & König, C. J. (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 889–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S. (2008). From Mead to a structural symbolic interactionism and beyond. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., & Zhang, P. (2006). The role of moderating factors in user technology acceptance. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(2), 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2018). Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(3), 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., & McKelvey, B. (2007). Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(4), 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Bala, H. (2008). Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sciences, 39(2), 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. (2021). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. In Managing digital transformation (pp. 13–66). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. (2012). Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(4), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., & Rosing, K. (2015). Ambidextrous leadership and team innovation. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(1), 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).