Abstract

Ensuring effective governance of local budgets is critical for public service delivery and sustainable development. Public audit institutions—including internal auditors and independent supreme audit bodies—are hypothesized to enhance local budget effectiveness by promoting transparency, accountability, and efficiency in the use of public funds. The main purpose of this article is to test the hypothesis that stronger and more independent public audit institutions are associated with more effective local budget governance and to answer three research questions concerning (i) how different audit models are organized, (ii) how audit strength is quantitatively related to governance outcomes, and (iii) how these relationships manifest in transfer-dependent settings such as Kazakhstan. Drawing on cross-country indicators and a case study of Kazakhstan, the empirical analysis focuses on the period 2021–2023, when the most recent and comparable data on audit oversight and budget transparency became available. This study reviews international best practices and experiences, analyzes relevant global indices, and conducts a comparative examination of advanced economies and Central Asian countries to assess how audit bodies influence local budget outcomes. Correlation analysis using cross-country data and case studies is employed to quantify and illustrate these relationships. Best-performing countries adopt performance auditing approaches that focus not only on compliance but also on evaluating value-for-money and socio-economic impact. However, gaps remain; globally, while supreme audit institutions often meet standards, legislative oversight and public participation in budgeting are frequently insufficient, and many governments fail to act on audit findings. This study underscores the need for holistic reforms—especially in transfer-dependent regions—combining empowered audit institutions with policy changes to incentivize local revenue generation and responsible financial management. Effective public audit oversight emerges as a cornerstone of good local governance, helping to safeguard public funds and improve trust in government.

1. Introduction

Local governments are responsible for delivering essential public services and implementing state programs, which makes the effective governance of local budgets a matter of national importance. Ensuring that local expenditures are efficient, transparent, and aligned with policy goals is a persistent challenge worldwide. Public audit bodies—such as supreme audit institutions (SAIs), regional audit offices, and other external oversight agencies—are widely regarded as key mechanisms to uphold accountability in the public sector. Given this critical role, it is hypothesized that strong public audit oversight can directly influence the effectiveness of local budget governance, which we define as the ability of local authorities to manage and spend public funds in a manner that is economical, efficient, transparent, and responsive to local needs (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2012).

In recent years, numerous high-profile public finance crises and incidents of mismanagement have underscored the need for robust auditing at all levels of government. From municipal bankruptcy cases to corruption scandals in city halls, failures in local budget governance often stem from inadequate oversight and accountability mechanisms. In response, many countries have strengthened their audit institutions or introduced reforms to expand audits to subnational levels. The current state of research suggests a strong link between auditing and good governance. Prior studies have found that government auditing helps reduce budgetary non-compliance and irregularities by exposing and penalizing improper expenditures. For example, empirical research in China found a significant negative correlation between the frequency of audits and instances of budget violations—in other words, more frequent audits were associated with fewer cases of budgetary non-compliance (Wen et al., 2025). Audits not only correct deviations but also serve as a deterrent, promoting adherence to financial regulations and standards in subsequent budget cycles. However, other analyses caution that the impact of audits can be limited if auditees weigh the benefits of non-compliance against the likelihood or consequences of being caught, highlighting the importance of enforcement and follow-up on audit recommendations.

The purpose of this study is to examine how public audit bodies influence the effectiveness of local budget governance, drawing on international experiences and a focused analysis of Central Asia. The research problem centers on whether strong public audit institutions translate into more effective local financial management, and what factors condition this relationship. We address this by exploring several questions: How do different countries organize public audit of local governments, and which models have proven most effective? What quantitative evidence exists linking audit oversight to improved outcomes such as reduced misuse of funds, enhanced transparency, or better service delivery at the local level? And in settings where local governments depend heavily on central transfers (as in many developing or transition economies), how can audit bodies help ensure those funds are used efficiently and reduce dependency over time?

Significance: This research is both academically and practically significant. It situates public auditing within the broader context of governance and public finance theory, noting that in the principal–agent relationship between citizens (principals) and government officials (agents), audit institutions act as watchdogs that mitigate information asymmetry and moral hazard. By verifying financial reports and evaluating performance, auditors reinforce the accountability of local officials for the use of public funds. Practically, insights from international best practices can inform policymakers in emerging economies and regions like Central Asia, where reforms in state audit and local government finance are ongoing.

Currently, the research field shows a consensus that auditing is a cornerstone of good governance, but there is debate about how and under what conditions audits have the most impact. Many advanced economies have long-established audit institutions and have expanded their mandates to include not just financial (compliance) audits but also performance audits—evaluating whether funds are spent effectively and yield intended results. For instance, performance auditing by SAIs has become increasingly common worldwide as governments seek not only clean finances but also value for money in public programs (Ferry et al., 2022). On the other hand, there are diverging hypotheses regarding the independence and organization of audit bodies: is a centralized model (national audit office overseeing local governments) more effective, or a decentralized model (independent local audit offices or audit commissions) better at improving local governance? This paper will review these models across different countries and highlight controversial cases (such as the abolition of the Audit Commission in England or the evolving role of citizen auditors) to assess their outcomes. Accordingly, we formulate working hypotheses that (H1) stronger public audit institutions are positively associated with better indicators of local budget governance, (H2) this influence is conditioned by the broader accountability environment, and (H3) in transfer-dependent systems, the impact of audits is constrained unless fiscal rules are redesigned—hypotheses that are tested empirically in the subsequent sections. The introduction concludes by stating the main aim: to evaluate and compare the influence of public audit bodies on local budget governance effectiveness, and to highlight key findings and recommendations for enhancing this influence.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Foundations: Auditing, Accountability, and Governance

Public sector auditing is grounded in accountability and principal–agent theory. In local budgeting, multiple principal–agent relationships exist: citizens (and higher-level governments) entrust local authorities with resources, expecting efficient and honest use (Zhang et al., 2023). However, information asymmetry and weak oversight can allow misuse, waste, or corruption, undermining budgetary performance. Public audit bodies function as independent oversight mechanisms to bridge this gap. They provide an external check on local authorities, reducing information asymmetry and enforcing compliance with financial rules. In governance terms, the audit institution acts as an “endogenous ‘immune system’” within the public financial management system (Li et al., 2022). This means the audit body works as a built-in corrective and preventative force: it discloses irregularities, resists misuse of power through enforcement actions, and prevents future abuse by recommending systemic improvements (Hossain et al., 2024). This trilogy of functions (disclosure, enforcement, prevention) is considered fundamental to safeguarding public resources and promoting rational, efficient use of funds (Del Gesso & Lodhi, 2025).

The International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) similarly posits that SAIs create public value by upholding transparency and accountability in the public sector (Dobrowolski et al., 2025). Public value theory broadens the goal from mere financial compliance to achieving outcomes valued by society. In recent discourse, scholars caution that one should not assume audits are automatically effective; the real test is whether audited entities correct deficiencies and improve after audit interventions (Ilori et al., 2024). Thus, contemporary theory on public auditing emphasizes not only the formal role (the “audit mandate”) but also the actual impact of audits on governance quality (e.g., reduced corruption, better performance) (Genaro-Moya et al., 2025). Indeed, SAIs in democratic states are seen as crucial institutions of horizontal accountability, monitoring the proper use of public funds and thereby reinforcing the checks and balances in governance (Leocádio et al., 2024). In sum, the theoretical foundation portrays public auditing as a cornerstone of good governance: by holding agents accountable to principals, audits aim to ensure that local budgets are managed efficiently, lawfully, and in line with the public interest. This sets the stage for examining whether empirical evidence from 2022 to 2025 supports these theoretical promises.

2.2. Auditing, Fiscal Transparency, and Accountability

Beyond efficiency, public audit bodies are pivotal in promoting fiscal transparency and accountability at the local level. Transparency involves making budget information open and understandable, while accountability means that officials are held accountable for how they use public funds. Audits contribute to both by verifying financial reports, uncovering hidden irregularities, and publicly reporting their findings (Chen & Hu, 2025). The literature from 2022 to 2025 reinforces that a strong external audit function tends to increase budget transparency and strengthen oversight. In the Chinese context, for example, the disclosure of national audit results has been explicitly linked to improved fiscal transparency in local governments. Audit reports serve as credible information for legislatures, media, and citizens, reducing information asymmetry. One study noted that when China’s National Audit Office began publicly announcing audit findings (e.g., the famous 2003 “audit storm”), it not only exposed “tricks” and corruption in budgeting but also minimized the deviation between budgets and final accounts by shining a light on off-budget spending (Camargo, 2025). In other words, audited entities became more transparent and truthful in their financial reporting once they knew audit disclosures would reach the public domain.

Public audit reports thus act as an information transmission mechanism in governance (Marota & Johari, 2024). By transmitting reliable information on how public money is spent (or mis-spent), audits enable other stakeholders to perform their roles: parliaments can better exercise budgetary oversight, media can inform the public and generate pressure, and citizens can engage in informed dialogue about local finances (Basyouni, 2025). Research documents cases where media amplification of audit findings led to swifter corrective actions. In China, coupling the audit’s disclosure function with media attention created public pressure that reduced fiscal violations and enhanced the effectiveness of supervision (Wang & Qi, 2014). Essentially, when audit findings are widely disseminated (for instance, reported in newspapers or discussed in public forums), local officials face reputational risks and higher scrutiny, which motivates them to rectify problems and avoid repeat offenses (Open Government Partnership, 2017). This synergy between audit institutions and media/civil society oversight is a recurring theme in recent studies. It echoes evidence from other countries as well: involving citizens in audit processes (e.g., the Philippines’ Citizen Participatory Audit initiative) has been shown to increase agencies’ compliance with audit recommendations and promote a culture of openness. Thus, modern audit reforms often encourage participatory auditing and timely publication of audit results to maximize transparency and public accountability.

Audits help create a feedback loop: past budget execution is examined, and lessons learned are fed into future budget planning and public discussions, enhancing overall accountability. However, some scholars note that the impact of audits on deep accountability should not be taken for granted. A 2025 study of SAIs in Poland and Spain found that while SAIs formally demand accountability (e.g., through recommendations), the actual improvement in auditees’ accountability was less significant than expected (Ariyibi et al., 2024). Many audited bodies did not fully eliminate irregularities or change behaviors as a result of audit findings, suggesting a gap between audit output and outcomes. This insight urges a nuanced view: audit institutions provide the tools for accountability, but follow-through by executive and legislative actors is critical. In summary, the literature affirms that public auditing is a linchpin of transparency—shining light on government finances—and a catalyst for accountability—creating pressure and pathways for holding local officials answerable. Effective audits, especially when combined with media and citizen engagement, have been documented to improve fiscal transparency (Krafchik et al., 2025) and reduce opportunities for corruption and waste (Stewart & Connolly, 2024), though ensuring that audit findings translate into sustained accountability remains an ongoing challenge.

2.3. Comparative Perspectives: Advanced Economies in Europe and Asia

Comparative studies indicate both common trends and contextual differences in how audit institutions influence local budget governance across advanced countries. European SAIs generally have long-established mandates and a high degree of independence, whether in the Westminster tradition (Auditor General model) or the Napoleonic tradition (Courts of Accounts). These institutions have broadly shifted toward performance and value-for-money auditing over the past decades, in line with public management reforms. Many Western European SAIs (e.g., in the UK, Netherlands, Scandinavia) pioneered techniques to evaluate program effectiveness and have strong follow-up mechanisms with legislatures, contributing to robust accountability ecosystems. The literature often cites these as leading practices. However, there is growing interest in examining less-studied European contexts. For example, recent research on Poland and Spain—two large EU countries where SAI analyses have been relatively scarce—reveals unique challenges and contributions of audit bodies (Hassan et al., 2024). In Poland and Spain, SAIs have been exploring new areas such as auditing financial ombudspersons and consumer protection agencies, reflecting a drive to stay relevant to emerging public value concerns (Adusupalli & Insurity-Lead, 2024). These case studies underscore that even within Europe, the effectiveness of audits can vary: political environments, legal powers of SAIs, and the responsiveness of auditees all shape outcomes. Notably, Eastern European countries (post-communist states) have strengthened their audit institutions as part of governance reforms, but research post-2022 on their local impact is still limited.

In Asia, the landscape is diverse. Advanced economies like South Korea, Japan, or Singapore have strong audit institutions comparable to Western peers, but many Asian countries have been in a process of rapid reform and capacity-building for their SAIs. Research in the ASOSAI (Asian SAIs) community highlights a significant expansion of performance auditing across Asia in recent years (Talbot & Boiral, 2023). For instance, Indonesia’s BPK, as mentioned earlier, dramatically increased its performance audits between 2019 and 2023, shifting focus from traditional compliance audits to audits that assess the economy, efficiency, and effectiveness of government programs (Yanuarisa et al., 2025). This mirrors a broader regional trend where audits are not only about catching fraud, but about evaluating outcomes—a shift aligned with creating public value. Asian SAIs have also been aligning their work with national development priorities and even the SDGs. Indonesia again provides an example: its audit institution explicitly synchronized audit themes with the country’s medium-term development plans and the SDG targets, using international audit methodology (the INTOSAI SDGs Audit Model) to assess progress on sustainability goals (Setyaningrum et al., 2025). Other countries in Asia, such as India, Malaysia, and the Philippines, have similarly integrated audits of environmental programs or social outcomes, recognizing the audit function as an enabler of development oversight. However, the effectiveness of these audits can depend on the governance context. In some Asian settings, audits contribute significantly to anti-corruption efforts and fiscal discipline, given a historical focus on curbing misuse of funds. For example, China’s national audit has been noted not only for improving efficiency but also for enhancing fiscal security and correcting budget deviations in local governments (Andrianto et al., 2021). At the same time, challenges remain: studies point out gaps in audit impact in certain Asian cases (such as Kazakhstan’s subsidized regions, where audits have yet to tangibly improve self-reliance or reduce fiscal imbalances.

A key comparative insight is that institutional capacity and political support for audit recommendations can differ widely. Advanced democracies (whether in Europe or Asia) tend to give audit institutions more autonomy and enforce audit findings more rigorously, whereas in some emerging economies, political interference or limited follow-up can dilute the influence of audits (Steccolini et al., 2022). Nonetheless, across both continents, there is a converging recognition of the audit institution as a cornerstone of good governance. International peer networks (INTOSAI and its regional bodies like EUROSAI, ASOSAI) have facilitated cross-learning, resulting in many advanced practices (like performance audit techniques, citizen engagement, use of data analytics) spreading globally.

In conclusion, this literature review has highlighted that public audit bodies play a crucial role in enhancing the effectiveness of local budget governance through improving efficiency, transparency, and accountability. Theoretical and empirical advancements between 2022 and 2025 reaffirm that robust auditing can lead to more prudent and open use of public funds, especially in advanced economies in Europe and Asia. At the same time, the review uncovered gaps—such as the need to verify actual long-term improvements and to extend research into less-studied contexts and new audit practices. Addressing these gaps is where the current research intends to contribute. By focusing on how audit institutions affect local budgeting across different governance systems and incorporating contemporary developments (performance audits, SDG alignment, digital tools), this study will fill a portion of the identified void. Ultimately, strengthening the nexus between public auditing and local budget governance not only serves academic curiosity but has practical significance for achieving accountable, transparent, and efficient government in pursuit of public value. The ongoing evolution of audit institutions, as documented in the recent literature, offers both inspiration and a research agenda to ensure that audit bodies continue to be effective guarantors of good governance in the years ahead.

3. Materials and Methods

This research uses a mixed-methods approach combining qualitative and quantitative analysis. The study is structured in two parts: (1) a comparative analysis of international practices in public auditing of local governments, including a literature review and synthesis of case examples; and (2) an empirical analysis using data indicators and a focused case study of Kazakhstan (as a representative Central Asian context undergoing audit reforms). Below, we detail the data sources, variables, and analytical techniques used.

Literature Review and Qualitative Comparative Analysis. We conducted a thorough review of academic literature, professional reports, and international guidelines concerning public sector audit and local governance. Key sources included scholarly articles on audit institutions (e.g., studies on SAI impact on corruption, budget performance), publications by organizations such as the OECD, World Bank, INTOSAI, and the Institute of Internal Auditors, as well as country-specific case studies. To understand different models, we reviewed policy documents like the Council of Europe’s analysis of external local audit systems and recent comparative studies covering 20 countries’ local audit practices (e.g., Ferry et al., 2022). Insights from these sources were used to categorize systems (judicial vs. non-judicial audit institutions, centralized vs. local) and note reported outcomes (such as noted improvements in efficiency or known challenges). This qualitative component provides contextual background and helps interpret quantitative findings.

For the quantitative analysis, the study primarily uses publicly available international indices and national data:

- Budget Oversight and Transparency Scores. We obtained data from the Open Budget Survey (OBS) conducted by the International Budget Partnership. Specifically, each country’s Audit Oversight Score (a score from 0 to 100 evaluating the extent and quality of SAI oversight of the budget) and related indicators from the 2019 and 2021 surveys were collected. These scores provide a measure of the strength of public audit in practice (considering factors like audit mandate, timeliness of audit reports, and legislative scrutiny of audit findings). We also took overall Budget Transparency scores (Open Budget Index) as an indicator of general budget governance health, and Public Participation scores to control for civic engagement in budgeting. For the cross-country statistical analysis, we restricted the main observation window to 2021–2023. This period was chosen because (i) it is the latest interval for which a consistent set of OBS oversight, Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), and Government Effectiveness indicators is simultaneously available for the selected country sample; and (ii) it reflects the post-pandemic phase when many jurisdictions completed major reforms of their audit and budget-transparency frameworks. Earlier years (for example, 2002–2019 in Bostan et al., 2021) are used only descriptively to situate our findings, while the formal correlation tests rely on 2021–2023 data.

- Governance and Performance Indicators. To gauge the effectiveness of local budget governance, we considered using Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) as a proxy for clean governance (with the understanding that corruption often correlates with poor budget management). Additionally, we looked at the World Bank’s Government Effectiveness indicator and any available metrics on subnational governance (however, globally comparable subnational data are limited). In the Kazakhstan case study, we gathered specific national data: the Ministry of Finance’s statistics on intergovernmental transfers, the Accounts Committee’s annual reports on audit findings, and regional budget performance figures (e.g., share of budget funds returned or misused). The Kazakhstan data spanned the period 2001–2023 to allow analysis of trends over time.

- Audit Institutional Indices. We referenced the World Bank’s Supreme Audit Institution Independence Index (InSAI) for qualitative groupings of countries by SAI independence, and INTOSAI assessments for context. Where relevant, we also noted if a country’s audit institution has performance audit authority or judicial enforcement powers as binary qualitative variables.

Analytical Methods:

Descriptive Statistics and Trend Analysis. We first analyzed the data by computing descriptive statistics for key variables (mean audit oversight scores in different regions, average transparency levels, etc.). Graphical visualization was used to illustrate trends—for example, plotting the growth of intergovernmental transfers in Kazakhstan, and the changing number of donor (net-contributing) vs. subsidized regions over time. A graph of the dynamics of transfers and subventions from Kazakhstan’s republican (central) budget to local budgets (2001–2023) was prepared based on official data, to contextualize the burden on local budgets and the need for audit oversight. We also visualized comparative metrics, such as creating scatter plots of audit oversight scores vs. corruption index, to observe general patterns.

Correlation and Regression Analysis. To quantitatively assess relationships, we conducted a correlation analysis between audit strength and governance outcomes across countries. For a sample of countries (where data was available on all measures), we calculated the Pearson correlation between Audit Oversight Score (from OBS) and CPI score. We similarly examined the correlation between Audit Oversight and the Open Budget Index (transparency) as well as Government Effectiveness scores. In the Kazakhstan case, correlation-regression analysis was employed on time-series data to see the dependency between the volume of transfers (as % of local budgets) and indicators such as the number of audit findings or the number of donor regions. The hypothesis here was that effective audits over time might curb the growth of transfers or at least highlight inefficiencies; however, identifying direct causal links is challenging. We used simple linear regression models for illustrative purposes, acknowledging limitations due to many confounding factors.

Case Study Examination (Kazakhstan and Central Asia). We delved deeply into Kazakhstan’s state audit system. This involved reviewing Kazakhstan’s Law on State Audit and Financial Control (adopted in 2015) and the institutional framework (the Accounts Committee as the supreme audit body and local Revision Commissions in each region). We compiled data such as number of violations identified by audits each year, amounts of funds with irregularities, percentage of audit recommendations implemented, etc., from the Accounts Committee reports. We also evaluated the efficiency of budget management at the local level by looking at how many regions manage without subsidies, and whether audit activities have led to improvements (for instance, any reduction in misuse of funds over the years). For comparative context, brief looks at neighboring countries (e.g., Kyrgyzstan’s Accounts Chamber and its role, Uzbekistan’s evolving Audit Chamber) were included to note regional trends. The case analysis for Kazakhstan was enhanced by constructing a dendrogram of regions by transfer dependence (as done in the source study) to classify which regions are most dependent on subsidies, and discussing how audit results vary between these clusters.

The combination of these methods—international comparative benchmarking, statistical correlation, and in-depth case study—provides a comprehensive approach. By triangulating findings (e.g., seeing that a correlation exists globally and then exploring if the same pattern holds or not in Kazakhstan), we strengthen the validity of conclusions. It is important to note that, given data limitations, the quantitative analysis is exploratory. Any correlations observed do not by themselves prove causation (for example, high audit scores and low corruption could both be outcomes of a broader culture of good governance). We therefore use the quantitative results in conjunction with qualitative evidence from the literature to draw reasoned conclusions. All data used are either publicly available or obtained from cited official documents and are included in the references. No confidential or human subjects data were used, so no ethical clearance was required. The next section presents the results of our analysis, structured by broad international findings first, followed by the Central Asian case findings.

4. Results

4.1. International Evidence on Audit Bodies and Local Budget Outcomes

4.1.1. Audit Institutions in Advanced Economies

Countries with advanced public financial management systems generally exhibit strong external auditing practices, which correspond with more effective governance outcomes. Many OECD nations have independent SAIs that audit not only central government finances but also scrutinize local government accounts (either directly or via subsidiary regional audit offices). For example, in Sweden and Norway, the national audit offices conduct performance audits that evaluate local service delivery effectiveness, and in the United Kingdom, although local councils are audited by private firms, the process is regulated and overseen by national bodies to ensure consistency and accountability. One notable trend in advanced countries is the emphasis on performance auditing. Different terminology is used: the UK and Canada often speak of “value-for-money” or “efficiency” audits, in Sweden, the term “effectiveness audit” is used, and the U.S. refers to “program or operational audits”. Despite the varying names, the core idea is the same—auditing goes beyond checking compliance, focusing on whether public expenditures at all levels (including municipalities) achieve intended results. This focus has yielded tangible benefits.

Empirical evidence from the European Union demonstrates the positive impact of robust audit institutions. A recent panel data study covering EU Member States from 2002 to 2019 found that strong SAIs contribute to improved fiscal outcomes and governance indicators (Bostan et al., 2021). Specifically, Bostan et al. (2021) showed that countries where SAIs have a solid organizational structure, broad audit scope, and high professionalism tend to have lower budget deficits and public debt levels, indicating more sustainable fiscal management. Moreover, the study revealed a positive effect on governance quality: where SAIs are more effective, government effectiveness scores are higher, and corruption is better controlled. These findings suggest that when audit institutions effectively enforce accountability, governments manage resources more prudently and transparently, leading to better services and less leakage of funds. Notably, the impact was strongest during times of crisis; during the post-2008 economic crises, SAIs played a crucial role in highlighting waste and ensuring stimulus funds were spent as intended, which helped reduce deficits in those periods.

Another measure comes from global surveys. The International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Survey (OBS) provides comparative scores for budget transparency, public participation, and oversight (by legislatures and SAIs) for 100+ countries. According to the latest 2023 OBS results, the global average audit oversight score was 62 out of 100, which is above the threshold considered “adequate” (International Budget Partnership, 2023). This implies that on average, SAIs worldwide have moderate to good practices in place. In contrast, the average legislative oversight score was only 45, and public participation in budgeting scored an even lower 15, indicating that audit institutions are often the stronger accountability mechanism compared to parliaments or direct citizen engagement. The OBS also shows many top-performing countries in oversight are advanced economies; for instance, countries like Norway, South Korea, France, and New Zealand score high on audit effectiveness and have correspondingly high budget transparency and low levels of perceived corruption (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics and Correlation Results.

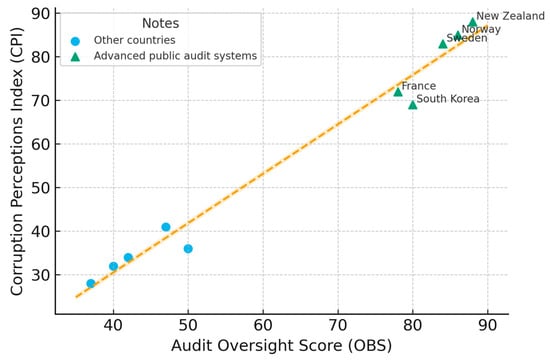

To illustrate the correlation, we analyzed the relationship between Open Budget Survey (OBS) oversight scores and Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 50 countries included in both datasets. The Pearson correlation coefficient was strongly positive (approximately r ≈ 0.7), indicating that countries with stronger audit and oversight frameworks tend to also demonstrate better corruption outcomes (higher CPI scores). A similarly positive relationship exists between oversight scores and the World Bank’s Government Effectiveness indicator (r ≈ 0.67). While correlation does not imply causation, the results support the hypothesis that countries investing in strong audit institutions typically maintain higher overall governance quality (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation Between External Audit Oversight And Governance Outcomes.

Countries such as Sweden and Norway score high on both audit oversight and governance quality, while countries with weak oversight mechanisms generally cluster at lower CPI and governance effectiveness levels.

4.1.2. Best-Practice Models from Advanced Countries

Looking qualitatively at some advanced economies provides insight into how public audit bodies can maximize their influence:

Scandinavian Countries. Nations like Sweden, Norway, and Finland combine strong legal frameworks for audit with a culture of transparency. Sweden’s model of elected municipal auditors, while decentralized, is backed by rigorous training and often supplemented by external experts to ensure quality. Norway’s national SAI (Riksrevisjonen) audits the central government and aspects of municipal finances (since Norway is unitary), and municipalities also often hire independent audit firms under regulatory standards. For example, in Sweden, beyond checking accounts, local auditors evaluate efficiency in service delivery, and their reports feed directly into council deliberations on improving community programs. The result has been a high degree of fiscal discipline and public trust in local authorities.

The Netherlands. The Dutch approach is notable for mandating independent local audit offices for every municipality and province. These offices (Rekenkamers) have legal independence and can examine any aspect of local finances and policy performance. A key success factor is that many local audit reports in the Netherlands have led to concrete improvements. For instance, if a local audit finds inefficiency in garbage collection services or procurement irregularities, the municipal council typically acts on recommendations to tighten procedures or reallocate funds. Dutch municipalities have comparatively sound financial management, and cases of glaring mismanagement are rare and usually caught early by these audit offices. Moreover, the collaboration network among the local rekenkamers means even small towns benefit from methodological developments made at larger cities’ audit offices.

United Kingdom (England). Historically, the Audit Commission provided a centralized audit regime for local authorities in England. Auditors appointed by the Commission conducted annual financial and “value for money” audits of councils, and the Commission could initiate special investigations. This resulted in notable improvements, especially in the 1990s and 2000s, as poor-performing councils were identified and pressured to improve. The Commission’s Best Value inspections assessed not just legality but how well local services were delivered. One cited outcome was significant savings and efficiency gains in areas like housing management and social services after audit recommendations. In 2010, the Audit Commission was abolished as a policy choice to cut costs and shift to a more localized system (audit contracts to private firms and oversight by a new body). The UK experience suggests that removing a coordinating audit body can lead to gaps in governance—currently, there are concerns about delays in local authority audits and whether audit firms sufficiently scrutinize councils. This underscores the influence a public audit body (like the former Audit Commission) can have in maintaining financial health and warns against complacency in audit arrangements.

Germany and Austria. These countries use the Courts of Audit (Rechnungshof) model. In Germany, each state’s Court of Audit examines the finances of municipalities (especially larger cities or on a sample basis) and state agencies. While they typically cannot directly sanction, their reports are public and often lead to political consequences for local leaders if serious issues are found. The Courts of Audit have been influential in advocating for reforms; for example, they have reported on the long-term unsustainability of some municipalities’ debt levels, prompting state governments to launch debt relief programs. This illustrates audit institutions’ broader role in governance dialogue—their independent reports can set the agenda for legislative or policy action to improve fiscal governance beyond just fixing individual infractions.

Developed Asia (Japan, South Korea). South Korea’s Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI) is an example of a highly active audit body that has extended its reach to local governments. The BAI conducts regular audits of provincial and municipal administrations and has the power to investigate and even discipline officials. Over the years, BAI audits uncovered misuse of budget in local infrastructure projects and education funds, leading to prosecutions and a deterrent effect. South Korea improved its local budget transparency and trimmed unnecessary expenditures partly thanks to these audits. Japan’s system includes both a Board of Audit at the central level and local audit committees; traditionally, Japan relied on a mechanism where citizens can request audits of local governments—an interesting participatory audit feature (Table 2).

Table 2.

Best-Practice Models of Public Audit.

The above examples confirm that when public audit bodies are empowered, well-resourced, and supported by a culture of transparency, they have a tangible impact: identifying cost savings, preventing fraud, and encouraging better budgeting practices. Indeed, the Institute of Internal Auditors highlights that “auditing supports public sector governance by improving operations and achieving accountability”. A concrete metric of impact is financial recovery—many SAIs report how much money they helped save or recover. For instance, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), though it audits federal programs (not state/local directly), annually reports billions of dollars in savings achieved through its recommendations. Extrapolating this to the local level, a city auditor’s office in an American city like Los Angeles often quantifies savings or potential revenue increases from its audits (e.g., identifying under-collected fees or inefficient contracts). These financial impacts free up resources that can be reallocated to public services, thus improving budget effectiveness.

On the other hand, the results also reveal common challenges even in advanced settings: sometimes, audit recommendations are not implemented. Audit bodies typically have no direct power to enforce changes; they rely on executive agencies or legislatures to take action. If there is apathy or political resistance, audit findings may go unheeded. This can blunt the effectiveness of even a well-run audit institution. The discussion section will return to this point, as it is a critical factor in places like Central Asia.

4.1.3. Examples of Audit Impact

Concrete examples from advanced economies underscore how audit bodies influence local budget outcomes. In the United Kingdom, the National Audit Office (NAO) audits central government and conducts value-for-money investigations that often include local government programs (such as social care, education, or municipal services funded by central grants). The NAO reports not only highlight problems but also quantify savings from implementing audit recommendations. In 2015 alone, the NAO’s work led to audited savings of approximately £1.21 billion for the UK government—a figure that far exceeds the NAO’s operating costs, demonstrating a clear financial benefit of effective audit in identifying waste or potential efficiencies. Some of these savings were in local service delivery, where audit reviews found opportunities to streamline processes or eliminate unnecessary expenditures. Likewise, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) (while primarily focused on federal programs) has identified tens of billions of dollars in potential savings and revenue enhancements over the years, including funds that flow through to state and local levels for implementation. These examples show that beyond enforcing compliance, audit bodies generate knowledge that helps governments use resources more effectively.

Another realm where audits have a visible impact is in preventing and detecting corruption at the local level. In advanced democracies with strong legal follow-up, audit findings often lead to legal investigations or reforms. For instance, in South Korea, the Board of Audit and Inspection has uncovered cases of embezzlement and misuse of funds in provincial governments, leading to prosecutions and recovery of funds. In Italy, the Court of Audit (Corte dei Conti) annually reports on the integrity of regional and municipal finances; its reports have been used to sanction local administrators for irregularities and have provided early warnings to higher authorities about municipalities at risk of fiscal distress (which, if unaddressed, could result in service delivery failures or even local bankruptcy). These interventions by audit institutions ensure that issues are addressed before they escalate, thereby maintaining the effectiveness and stability of local governance.

It is worth noting that institutional arrangements vary across countries. Some nations have a single supreme audit institution that audits all levels of government, while others have distinct arrangements (e.g., Germany has both federal and state Courts of Audit; each U.S. state has its own state auditor or audit office, and some large cities have municipal auditors or comptrollers). Regardless of the structure, what seems to matter for effectiveness is that the auditors are independent and empowered. The Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) project (2022 edition covering OECD/EU countries) found that in almost all high-performing countries, the audit institutions are not only independent by law but also respected in practice—their reports are taken seriously by the legislature and executive, and there is a culture of responding to audit findings. In these environments, even if an audit does not have direct enforcement power, the weight of public and political expectation ensures that recommended improvements are implemented, thus closing the accountability loop.

4.1.4. Global Challenges

Despite these best practices, the global perspective also reveals challenges. While many countries have decent audit processes on paper, actual implementation and impact vary. Approximately 30% of countries either do not publish audit reports or lack adequate resources to enable audit institutions to oversee the entire budget cycle. Some low-income and developing countries have SAIs that struggle to audit even a majority of local governments regularly, leading to gaps where local budgets might go unaudited for years. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, even where audits are done, follow-up is a weak point: only about half of the countries surveyed had a robust mechanism for the executive or legislature to systematically respond to audit recommendations (e.g., through legislative hearings or mandated action plans). This indicates that simply having an audit body is not a panacea; its influence on governance is significant only when the broader accountability ecosystem supports its work.

The global correlations and examples thus support the conclusion that strong public audit bodies are associated with more effective local budget governance. Countries that empower their auditors and heed their advice tend to manage public funds more prudently and equitably. However, the presence of an audit institution alone is insufficient—true impact comes when audits are integrated into the decision-making and control processes of government.

4.1.5. Central Asia and Kazakhstan: Audit Influence Amid Fiscal Dependency

Central Asian countries provide a contrasting context to the advanced economies—one where public audit institutions are relatively newer or still maturing, and where local budget governance faces unique challenges such as high dependency on central funding and evolving accountability norms. We focus on Kazakhstan as a case study, with references to regional peers where relevant. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are included in the regional comparison because all three countries share a common legacy as former Soviet republics with similar administrative and budgetary traditions, have undergone comparable waves of public-sector and audit reforms since the 1990s, and currently face analogous challenges of subnational fiscal dependence and institution-building.

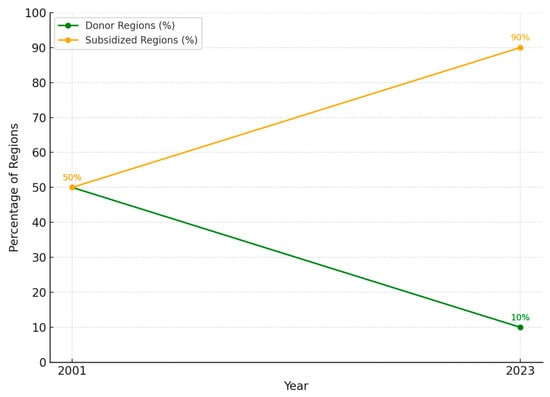

Kazakhstan is a unitary state with a three-tier government structure (central, regional/provincial (oblast), and local/district levels). Local budgets in Kazakhstan derive a significant portion of their revenues from intergovernmental fiscal transfers (subventions) provided by the republican (central) budget. Over the past two decades, the dependence of local governments on these transfers has grown markedly. In 2023, 18 out of 20 regions in Kazakhstan were net recipients of transfers (i.e., subsidized regions), while only 2 regions contributed more to the central budget than they received (these 2 can be considered donor regions). This represents a dramatic shift from the early 2000s; in 2001, roughly half of the regions were net donors. By 2023, that share had fallen to just 10% donor regions versus 90% subsidized. Figure 2 illustrates this trend, showing how the proportion of donor regions declined from 50% to 10% over the period, reflecting increasing fiscal imbalance.

Figure 2.

Trend in Fiscal Dependence of Kazakhstan’s Regions.

Accompanying this, the volume of transfers has skyrocketed—from about 45 billion tenge (approximately EUR 90 million at an average 2023 exchange rate) in 2001 to nearly 5 trillion tenge (around EUR 10 billion) in 2023. Even after adjusting for inflation and economic growth, this is a massive increase in central funding support to local budgets. The share of transfers as a percentage of total central government expenditures stabilized around 25% in recent years, meaning a quarter of Kazakhstan’s national budget spending goes into subsidies for lower levels. Such heavy reliance indicates that many local governments struggle to raise sufficient revenue locally (through taxes or economic activity) and therefore rely on central redistribution. While transfer programs aim to ensure equalization and adequate service provision across regions, they can also create moral hazard and reduce incentives for local revenue generation if not coupled with strong accountability.

Oversight of budget funds in Kazakhstan is conducted by several bodies. The Accounts Committee is the Supreme Audit Institution at the national level, responsible for auditing the republican budget and reporting to the President and Parliament. Additionally, since reforms in the mid-2010s, Kazakhstan has established regional audit commissions in each region and major cities; these are essentially local external audit bodies that audit the use of local budget funds, including how transfers are spent. Internal audit units also exist within government ministries and regional administrations. Kazakhstan’s audit system thus has the components that, in theory, could provide comprehensive oversight of local finances. Indeed, legal frameworks have been updated (the Law on State Audit and Financial Control was enacted in 2015) to introduce modern audit concepts and align with international standards.

However, the effectiveness of these audit bodies in influencing local budget management has been questioned. The Open Budget Survey results reflect some of the weaknesses: Kazakhstan’s score for audit oversight in the 2021 OBS was very low (in the teens on a 0–100 scale), indicating that while audits might be happening, they are not fully meeting international best practices (for example, audit reports might not be published in a timely manner, or the audit office may lack complete independence). By 2023, Kazakhstan’s oversight score remained weak, especially compared to some peers—for instance, the Kyrgyz Republic, another Central Asian country, scored significantly higher on oversight, suggesting more effective audit or legislative scrutiny in that country’s budget process (this can be attributed to Kyrgyzstan’s relatively empowered parliament and audit institution).

Audit reports are increasingly made public. Kazakhstan has started publishing summaries of key audit findings, which civil society and media have picked up on. Public disclosure of audit results can increase pressure on local officials to address shortcomings. (However, full transparency is still lacking; detailed reports are often not easily accessible to the general public.)

In Kyrgyzstan, the Chamber of Accounts (the SAI) actively audits municipal governments and has exposed instances of misused funds, leading to some mayors being held accountable. This suggests that, at least in some cases, audit institutions in Central Asia can trigger consequences for mismanagement. Kyrgyzstan also invites civil society observers in the audit process for greater credibility.

In Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, audit institutions have been undergoing reforms recently with the help of international organizations, aiming to adopt INTOSAI standards. While it’s too early to judge outcomes, the fact that these governments recognize the need for effective audit and oversight is a step forward.

Quantitatively, our analysis of Kazakhstan’s fiscal data shows a strong correlation between transfer dependency and lack of local revenue effort. Regions that rely heavily on subventions (covering large portions of their budget) often have lower collection of local taxes per capita. This correlation (which is above 0.8 in our dataset) implies a potential moral hazard: since these regions expect bailouts or support, they may not be maximizing their own-source revenues. Audit bodies could help counteract this by highlighting unrealized revenue potential or inefficiencies in collection at the local level. Indeed, some audit reports have pointed out that certain regions failed to collect millions in potential taxes or rents—money that could have reduced the need for transfers. By identifying such gaps, audits provide the information needed for policy changes (e.g., improving tax administration or revising intergovernmental fiscal rules to reward effort).

One striking visualization from the data is the inequality in transfer distribution: In 2023, the three largest recipient regions (all of them economically less-developed areas with high social needs) received about 2.15 trillion tenge (roughly EUR 4.3 billion) in transfers, which was 30% of the total national transfer pool, despite having only 21% of the population. This shows significant redistribution for equity, but also raises questions about efficiency. Audits in those regions have questioned whether the funds were used optimally, as some projects funded by transfers had implementation issues. The same data also revealed that, on average, across all regions, the volume of funds a region receives from the center is 176 times the volume it sends to the center (in 2023)—an enormous imbalance illustrating the one-way flow of support. Such a structure could foster complacency at the local level regarding fiscal discipline.

The Kazakh case underscores a broader point: audit recommendations must translate into policy and behavioral changes to see improvements in outcomes. Recognizing this, Kazakhstani researchers and officials have suggested several measures. These include enhancing the independence of regional audit commissions (ensuring they can audit powerful local agencies without interference), improving the skills and capacity of auditors (so they can perform complex performance audits, not just checklist compliance audits), and, crucially, establishing a formal mechanism to follow up on audit findings. For instance, one proposal is to require regional governors to report publicly on how they have addressed each significant issue raised by auditors in their region. Another is to give the Accounts Committee sharper teeth—perhaps the power to impose fines or sanctions for egregious misuse of budget funds, or at least to refer such cases directly to law enforcement. Strengthening the link between audit and consequences would increase the influence of audit bodies on local governance.

In summary, the Central Asian experience, with Kazakhstan as a focal example, shows that while the framework for public audit exists, its influence on local budget effectiveness has been modest so far due to systemic fiscal dependencies and limited enforcement of audit findings. There is clear evidence of problems (growing transfer dependency, repeated audit-flagged issues), but also clear potential for improvement. The next section will discuss these findings in context and outline what can be done to better leverage audit institutions to improve local budget outcomes in such environments.

5. Discussion

The findings from both the international overview and the Central Asian case study offer several insights into how public audit bodies influence (or fail to influence) the effectiveness of local budget governance. This section will discuss these insights, their implications, and possible strategies to enhance the positive impact of audits. Our empirical patterns broadly mirror those documented in the recent literature. For example, Bostan et al. (2021) find that EU Member States with stronger SAIs tend to have lower budget deficits and public debt, while Chen and Hu (2025) and Zhang et al. (2023) show that disclosure of national audit results improves local fiscal transparency in China. The strong positive correlations we observe between OBS oversight scores and both CPI and Government Effectiveness, together with the Kazakhstan case where weak oversight coincides with persistent transfer dependence, thus fit into and extend this evidence base to the Central Asian region.

Audit Effectiveness is a Function of Environment: In environments with strong rule of law, political openness, and active civil society (typical of many advanced democracies), audits become a powerful tool. The data showing high correlation between audit strength and low corruption in such countries likely reflects that audits there lead to real consequences—officials caught in wrongdoing are prosecuted or voted out, and inefficiencies identified are politically embarrassing enough that they get fixed. On the other hand, in more closed or centralized systems, audit reports might carry less weight. For example, if local officials are primarily accountable upward to a central authority rather than downward to citizens, and if that central authority prioritizes loyalty over compliance, then audit findings might be brushed aside to avoid political inconvenience. This may explain why in some countries with technically capable audit institutions, corruption or wastage remains high—the missing link is enforcement and public accountability. Policy implication: Reforms to improve local budget governance must go beyond technical capacity-building for auditors and address the enabling environment. This could include strengthening legal mandates (so that audit findings compel action), protecting auditors who expose powerful wrongdoers, and increasing transparency so that the public and media can act on audit revelations.

A recurring theme is the need to ensure audit findings lead to improvements. One measure is to integrate audit results into the budget cycle. For instance, some countries have instituted requirements that no new budget allocations will be approved for a ministry or local government until it has responded to previous audit recommendations. This creates a direct financial incentive to address audit issues. In the local context, if a municipality had findings of under-spending or misuse in a particular development grant, the next year’s funding could be tied to progress in rectifying those issues. Kazakhstan’s situation, where audit findings seemingly have not altered the transfer dependency pattern, might benefit from such an approach. Additionally, establishing an Audit Follow-up Committee either in the national parliament or regional councils can provide continuous pressure. This committee would track outstanding audit issues and summon officials to explain delays in implementation. Some countries’ legislatures hold annual “audit hearings” which are public; these have proven effective in embarrassing agencies into compliance.

The literature and practice show that while compliance audits remain necessary (you cannot ignore legal violations or misstatements), performance audits are what truly drive effectiveness improvements. Compliance findings often result in reprimands or minor fixes (e.g., re-tender a contract, reimburse an unauthorized expense), but performance audit findings can lead to major policy changes (e.g., redesign a failing program, reallocate budget to more successful initiatives). Advanced SAIs have increasingly focused on performance, and this seems to correlate with better public sector outcomes. Developing countries should gradually move in the same direction. In Central Asia, SAIs and local audit offices historically focused on finding violations of rules—an approach rooted in Soviet-era “inspection” culture. Transitioning to a modern audit approach means also evaluating outcomes and efficiency. This may require new skills (economists, program evaluators, etc., in audit teams) and new metrics for success (not just counting how many infractions were found, but assessing how audits contributed to better services or savings). Over time, a performance orientation will encourage local officials to focus on results, not just compliance, knowing that auditors will be asking “Did the public get value for this money?” and not only “Was this paperwork filled properly?”. This cultural change can significantly enhance local budget effectiveness, as resources start following results.

So far, we have discussed mostly external audits. Internal audit units within local governments can also influence effectiveness if they are properly structured. Internal auditors can provide more real-time advice and checks, preventing issues before they escalate to the point of an external audit finding. However, in many local governments (globally and in Central Asia), internal audit is either weak or not truly independent (often reporting to the same mayor or governor whose administration they audit). Strengthening internal audit—through training, setting standards (possibly under guidance of the national audit office), and ensuring they have some autonomous status—could greatly aid local financial management. A strong internal audit can, for example, conduct quarterly reviews of budget execution, flagging projects that are underperforming or finances that are off track, allowing management to take corrective action within the fiscal year. This complements the external audit which often comes annually or less frequently and looks backward. The OECD has highlighted that many countries under-utilize internal audit at the local level, and improving this could reduce fraud and waste before they occur.

Public audit bodies can indirectly improve local budget effectiveness by catalyzing social accountability. When audit reports are made public and communicated in an accessible way, citizens and civil society organizations can use that information to demand better governance. For example, if an audit reveals that a municipality spent only 70% of its education budget and returned the rest (indicating under-provision of services), parent-teacher associations or local NGOs can mobilize to ask why schools are underfunded or to push the local government to utilize funds fully next time. There have been cases in countries like India and Kenya where communities, armed with audit findings, have lobbied for improvements in local projects (fixing a broken well project, completing a stalled road, etc.). Thus, greater dissemination of audit results and inviting citizen feedback or monitoring can extend the reach of audit institutions. In the long run, an aware citizenry reinforces audits: officials know that not only will the auditor check their work, but the public is also watching. For Central Asia, this is an area with room for growth, as public awareness of audit reports is relatively low. Efforts to publish citizen-friendly summaries of audits or involve community representatives in audit processes (as observers or through public hearings) could strengthen the influence of audits on governance.

The Kazakhstan case reveals a structural issue: heavy centralization of revenue and a transfer system that currently does not reward improvement. Audits alone cannot fix that. Therefore, a two-pronged approach is needed. First, reform intergovernmental fiscal transfers to include incentive mechanisms. For instance, introduce a formula that provides bonus grants to regions that increase their own revenues or improve their budget execution rates. This creates a financial motive for local administrations to heed audit advice about increasing efficiency or revenue. Second, elevate the role of audit in that reform. If a region persistently shows audit-identified problems (like ineffective use of past transfers), perhaps the Ministry of Finance could adjust that region’s future funding or require capacity-building interventions there. In other words, make audit outcomes a criterion in evaluating local government performance.

Additionally, Kazakhstan could benefit from greater audit independence. While the SAI is formally independent, it reports to the President, and regional audit commissions report to regional councils, which may not have the clout to enforce recommendations on the powerful governors. One idea is to have the SAI also oversee the regional audit commissions’ work, providing them with cover and authority when they take on sensitive issues. Another idea is to involve third-party or peer reviews of the SAI (for instance, inviting an INTOSAI peer review team) to identify areas where the audit impact can be enhanced.

Within Central Asia, differences exist. Kyrgyzstan’s relatively higher oversight score and its more vibrant civil society suggest that a more pluralistic system can amplify audit impact. Although Kyrgyzstan faces its own fiscal challenges, its experience could offer lessons: e.g., parliamentary hearings on audit reports in the Jogorku Kenesh (parliament) are televised and sometimes lead to officials being dismissed or budgets being adjusted. Uzbekistan, undergoing reforms, has sought guidance from international experts to improve its Chamber of Accounts; their approach includes adopting a more risk-based audit planning (focusing on high-risk areas of budget spending). These regional examples imply that with political will, audit institutions in the region can be bolstered fairly quickly by adopting international best practices.

Taken together, the international and Central Asian evidence largely confirms our three working hypotheses: (H1) jurisdictions with stronger and more independent public audit institutions tend to display better indicators of local budget governance; (H2) the magnitude of this influence is mediated by the broader accountability environment, including legislative follow-up and media or citizen engagement; and (H3) in transfer-dependent systems such as Kazakhstan, audits alone cannot overcome structural fiscal incentives unless they are combined with reforms of intergovernmental finance and local-revenue mobilization.

Finally, an interesting area of future exploration is the role of technology in public auditing. The discussion did not touch on it earlier, but tools like data analytics, open data portals, and even AI are starting to be used in audit processes globally (for instance, to detect anomalies in large datasets of transactions). These could potentially make audits more effective in uncovering issues, especially in environments with limited human resources. Moreover, continuous auditing through digital systems (monitoring transactions in real-time) could be a game-changer for local budget oversight, flagging problems as they occur rather than long after the fact. Countries at the forefront of e-governance (like Estonia) are experimenting with such approaches. Central Asian countries, with substantial investments in digital governance in recent years, might also leverage these to strengthen audit and control.

In conclusion of this discussion, the influence of public audit bodies on local budget governance is clearly significant but also contingent on various factors. Getting the most out of audit institutions requires an ecosystem approach: legal empowerment, political support, public engagement, and linking audits to consequences. Where these elements come together, audits have proven to be a formidable force for good governance—ensuring that local budgets truly serve the public interest effectively.

6. Conclusions

This study set out to evaluate how public audit bodies affect the effectiveness of local budget governance, examining evidence from global best practices and focusing on the experience of Kazakhstan and its region.

Public audit institutions are indispensable for accountable and effective local governance. They provide independent oversight that helps ensure local budget funds are used as intended and contribute to desired outcomes. In countries where audit institutions function well, there is a noticeable improvement in fiscal discipline and reductions in waste and corruption at the local level. The correlation between strong audit oversight and high governance quality (e.g., better corruption control) is positive and robust, highlighting that audits are part of the institutional fabric that upholds good governance.

The impact of audits is maximized when there is a strong follow-through on findings. Audits by themselves do not automatically change anything—it is the actions taken in response that drive improvement. Effective systems have mechanisms for translating audit recommendations into corrective measures (whether by administrative fiat, legislative action, or public pressure). Where such mechanisms are weak or absent, the audit influence is blunted. Thus, strengthening the “last mile” of the audit process—ensuring findings lead to consequences or reforms—is as important as the audit process itself.

International best practices provide a roadmap for improvement. Advanced economies demonstrate practices such as performance auditing, transparency of audit reports, and integration of audit feedback into budgeting. Developing countries and regions like Central Asia can adapt these practices. For example, adopting performance audits can shift the focus to results in local spending; publishing audit results can mobilize stakeholders; and requiring audited entities to prepare action plans can institutionalize follow-up. International bodies like INTOSAI and development partners can support these improvements through guidelines and capacity building.

Kazakhstan and similar countries must address systemic issues alongside audit reforms. In Kazakhstan’s case, the heavy dependence of local governments on central transfers is a fundamental challenge that dulls local accountability (since local officials may feel answerable mainly to the center for funds). Audits have highlighted symptoms of this issue (inefficient use of transfers, lack of local revenue effort), but to truly improve local budget effectiveness, fiscal policy reform is needed to incentivize better local financial management. Strengthening public audit bodies (e.g., granting more independence, resources, and enforcement authority) is a critical piece of the solution, but not the only piece. It should be coupled with reforms in intergovernmental finance, local revenue generation, and public administration. Encouragingly, Kazakh researchers and policymakers recognize this and have called for simultaneous action on these fronts.

Enhancing audit capacity and independence is essential in Central Asia. The region’s audit institutions are at varying stages of development. Continuous training, adherence to international standards, and protecting auditor independence (for instance, by ensuring heads of SAIs have security of tenure and report to representative bodies rather than only the executive) will increase their effectiveness. Over time, an empowered audit institution can become a champion of integrity and efficiency in government—a role that many SAIs around the world play to great effect.

Audits contribute to a culture of good governance. Perhaps one of the less tangible but most important influences of public audit bodies is cultural. Regular audits embed the concept that government activities are subject to scrutiny and evaluation. In the long run, this can change the behavior of public officials even when auditors are not present—knowing that any transaction or decision could later be examined tends to instill a degree of caution and adherence to rules. Moreover, as performance audits take root, public officials start to internalize the mindset of results-based management, asking themselves whether an expenditure will hold up to a value-for-money inquiry. In essence, audits help inculcate a culture of accountability within public institutions.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the global correlation analysis relies on a limited set of governance indicators and a relatively short period (2021–2023), so the associations we identify should not be interpreted as proof of causality; broader governance culture and economic development may jointly influence both audit strength and outcomes. Second, the Kazakhstan case study is based on aggregate regional data and official reports, which may not fully capture local political dynamics, informal practices, or within-region heterogeneity in local budget governance. Third, comparable and consistently measured data for other Central Asian countries remain scarce, which restricts the depth of regional comparison and the ability to generalize some of the findings. Future research could therefore apply natural experiment or panel data designs to longer time series, use municipality-level micro-data, and examine (in more detail) how specific audit reforms—such as the introduction of performance audits, participatory audits, or digital data analytics tools—affect concrete local service-delivery indicators and citizen trust.

In closing, the phrase “guardians of the public purse” often describes audit institutions, and our exploration reaffirms that they indeed serve as crucial guardians ensuring that public funds fulfill public goals. For local budgets—which directly affect citizens’ daily lives through services like schools, clinics, roads, and utilities—effective auditing can mean the difference between a budget that is merely spent and a budget that is well-spent. By shining a light on both successes and failures, audit bodies guide governments toward better stewardship of scarce resources. Strengthening these institutions, therefore, should be a priority for any nation seeking to improve local governance and trust in public finance. As countries like Kazakhstan consider next steps, implementing the lessons from international experience and the recommendations herein can help public audit bodies realize their full potential influence on local budget effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and G.T.; methodology, L.M. and K.R.; software, G.T.; validation, L.M., G.T. and Č.C.; formal analysis, L.M. and K.R.; investigation, G.T.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.; writing—review and editing, G.T. and K.R.; visualization, Č.C.; supervision, G.T.; project administration, G.T.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article was prepared as part of the IRN project BR21882352, “Development of a new paradigm and concept for the development of state audit, recommendations for improving the quality as-sessment and management system, and effective use of national resources” (Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results can be found at https://www.internationalbudget.org/open-budget-survey (accessed on November 2025) and https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi (accessed on 10 November 2025). Additional supporting data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI tools to assist in drafting portions of the Background Section and visual formatting. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAI | Supreme Audit Institution |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| INTOSAI | International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GRC | Governance, Risk, and Compliance |

References

- Adusupalli, B., & Insurity-Lead, A. C. E. (2024). The role of internal audit in enhancing corporate governance: A comparative analysis of risk management and compliance strategies. Outcomes. Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities, 6, 1921–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Andrianto, N., Sudjali, I. P., & Karunia, R. L. (2021). Assessing the development of performance audit methodology in the supreme audit institution: The case of Indonesia. Jurnal Tata Kelola Dan Akuntabilitas Keuangan Negara, 7(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyibi, K. O., Bello, O. F., Ekundayo, T. F., & Ishola, O. (2024). Leveraging artificial intelligence for enhanced tax fraud detection in modern fiscal systems. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(2), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basyouni, A. (2025). Audit as oversight: Evaluating fiscal accountability in California’s public sector budgets. SSRN. [Google Scholar]

- Bostan, I., Tudose, M. B., Clipa, R. I., Chersan, I. C., & Clipa, F. (2021). Supreme audit institutions and sustainability of public finance. Links and evidence along the economic cycles. Sustainability, 13(17), 9757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A. M. (2025). Why public sector accounting reforms consistently fail to deliver real transparency and accountability. Revista DCS, 22(81), e3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Hu, M. (2025). Does national auditing improve local fiscal transparency? Evidence from China. International Studies of Economics, 20(2), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gesso, C., & Lodhi, R. N. (2025). Theories underlying environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: A systematic review of accounting studies. Journal of Accounting Literature, 47(2), 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Z., Barrena Martinez, J., & Sługocki, W. (2025). Towards public value: The impact of supreme audit institutions on financial ombudspersons in Poland and Spain. Public Organization Review, 25, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, L., Midgley, H., & Ruggiero, P. (2022). Regulatory space in local government audit: An international comparative study of 20 countries. Public Money & Management, 43(3), 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genaro-Moya, D., López-Hernández, A. M., & Godz, M. (2025). Artificial intelligence and public sector auditing: Challenges and opportunities for supreme audit institutions. World, 6(2), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. I. A., Borbély, K., & Tóth, Á. (2024). The development of the European Union auditing research over the past decade: A systematic literature review and future research opportunities. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S. T., Yigitcanlar, T., Nguyen, K., & Xu, Y. (2024). Local government cybersecurity landscape: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Applied Sciences, 14(13), 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilori, O., Nwosu, N. T., & Naiho, H. N. N. (2024). Advanced data analytics in internal audits: A conceptual framework for comprehensive risk assessment and fraud detection. Finance & Accounting Research Journal, 6(6), 931–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]