Abstract

This research explores the language features used by leading consumer brands with successful marketing in their promotional messages. Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever were selected because they appear in Effie’s Most Effective Marketers’ Index and are active on a range of media platforms. A group of 225 marketing texts, made up of social media posts, video advertisement transcripts, and website content, was examined using a corpus-based method based on Biber’s MDA framework. The goal was to find common lexicogrammatical patterns in top consumer brands on five different dimensions. Many advertisements included personal pronouns, commands, and words that suggest possibility or necessity. The findings also show that most social media posts provided information, yet had a moderate impact on persuasion. Abstract nouns, passive voice, and formal connectors were found to make the website and press release texts the most impersonal and explicit. The research discovered that Unilever’s language was more informational and abstract, but McDonald’s language was mixed-purpose and non-abstract. Overall, the results indicate that brands use vocabulary and grammar to fit each platform, but maintain their brand identity. Thus, successful consumer brands use different lexicogrammatical patterns in various media to achieve their objectives.

1. Introduction

Currently, global brands are making efforts to build good relationships with their customers and highlight their unique brand identities. Previously, marketing research pointed out that a distinctive brand voice and identity help businesses form strong ties with their customers. Ahuvia et al. (2022) believe that treating a brand as a person and staying consistent helps build a loyal bond with consumers.

Well-known companies such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever invest significantly in strategic brand communication to foster these relationships and loyalty. Many rank these companies among the world’s most valuable and respected brands (e.g., they appear in the Effie Global Top 100) and praise them for their creative campaigns that focus on their audience. Examining the language used in digital messages can help us see how language affects the way people think and act when using the internet.

A brand’s communication is present on various channels, including advertising, social media, and the web, and it mixes helpful information with an appealing and convincing approach. Earlier investigations have shown that ads use emotions and beliefs to encourage consumers to make decisions. For example, they usually use the word “you” to make the content sound friendly and direct. Wu and Ren (2024) indicate that when ads use the personal pronoun, customers are more likely to feel connected to the brand and have a more positive perception of it. Branding experts also believe it is essential for a brand’s voice to be consistent everywhere to make it recognisable and match its individuality. A brand is characterised in part by its communication, which can express sincerity or excitement (Feng et al., 2024).

Brands have increasingly relied on digital discussions on social media in recent years. On social platforms, people use language to be friendly and connect, rather than to exchange information (Koo, 2022). Most famous brands are known to use a casual tone on social networks to build trust with customers. It has a distinct tone that differs from that typically used in a press release or on a product’s website. Biber’s (1991) MD is a method that analyses language data and groups similar features into various dimensions. This approach enables the analysis of how people use language differently in multiple situations. It is based on the complementary distribution of the linguistic features.

Every dimension indicates how a style can be either highly interactive and involved or highly informational, or how it can transition from narrative to non-narrative. Several researchers have employed this method to investigate various types of registers in the English language, such as academic discourse (Ali, 2024a), Reddit language (Ali, 2024b), political language (Westin & Geisler, 2002), and online genres such as blogs and tweets (Clarke & Grieve, 2017; Xiao, 2009). As far as lexicogrammatical preferences are concerned, Biber’s (2006) findings showed that using private verbs, personal pronouns, and contractions leads people to score better on dimension 1. Alternatively, academic writing employs many nouns, groups of words that often include prepositions and adjectives, to describe various things. Over time, MD analysis has been used to study online writing texts (Biber & Egbert, 2016) and news writing (Sheng & Li, 2024).

Although previous studies, such as Koteyko (2015), Doyle (2010), and Ortolani (2024), have employed MDA to explore register variations in marketing and advertising, their scopes are limited in various ways. They are often gendered, are based solely on British advertisements or are consumption specific. Additionally, some studies have extracted lexical dimensions related to fashion marketing, social influence, and trend-setting. In contrast, our study applies Biber’s multidimensional analysis to five top marketing brands from the Effie Index Top Marketers List of 2023, comparing them on two levels: inter-brand differences and across different communication channels, including YouTube ads, social media, and website content.

The purpose of the present study is to analyse marketing texts from five leading companies using the five dimensions introduced by Biber (1991). The study employs Biber’s five dimensions to investigate the lexicogrammatical patterns that contribute to successful brand messaging. First, the study examines whether the language used in advertisements, social media posts, and other online content differs. Second, it examines how the brand communications of various companies differ in lexicogrammatical features and what this might mean for their branding strategies.

Accordingly, the central research questions guiding this study are: How do leading global brands differ in their use of linguistic features across Biber’s five dimensions, and how do these differences vary by content type (advertisements, social media posts, and website content)?

2. Literature Review

Recently, researchers have turned to advanced language theories to understand how international brands engage with their customers (Fernández-Cavia, 2025; Cheng & Li, 2024; Chan, 2022). Biber’s MD Analysis is widely used because it examines language features using statistical techniques to identify the primary ways people interact through language. Through MD analysis of UK press advertisements, Koteyko (2015) identified 32 features that demonstrate persuasion and information in ads are composed of various interacting dimensions. It was found that four persuasive dimensions emerged, which were labelled as Involved Concerns, Static Evaluative Description, Exhortative High-Promise Discourse, and Beneficial Performance. All of these were identified through the use of intensifiers, imperatives, and superlatives. This means that advertising language serves multiple functions simultaneously, informing the consumers while also attempting to persuade them.

Other methods and approaches have also helped reveal patterns in brand language. Several studies combine statistical analysis of language with detailed examination of marketing texts to gain a clear overview and in-depth understanding. Al Falaq and Puspita (2021) have used Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to analyse how advertisements present various ideologies. This study demonstrates that brands can convey specific social values by selecting certain words in their advertising. Even a small ad can effectively communicate important ideas about consumerism, colonialism, or gender. Over the past few years, researchers in marketing linguistics (Diwanji et al., 2024) have increasingly relied on computational tools, such as sentiment analysis. Natural language processing is used in sentiment analysis to figure out if a brand’s messages are liked or disliked by the audience.

Over the past three decades, the MD approach has been employed to investigate how languages vary across different genres and in response to new forms of communication. According to Biber and Egbert (2016), writing on the Internet can be either interactive, as in blogs and discussion forums, or informational, as on webpages that do not change. Sardinha and Pinto (2019) discovered that audience participation and argumentation are expressed differently in digital texts. In 2024, Biber et al. (2024) demonstrated that MD analysis is beneficial in both written and spoken communication and that there are distinct differences in style. Clarke and Grieve (2019) demonstrated that the persuasive style of political speeches is linked to the speaker’s political party and ideology.

Several medical studies have focused on the discourse of marketing and advertising. Koteyko (2015) noted that advertisements in specific sectors tend to employ distinct language compared to those in other sectors, and Wu and Ren (2024) found that corporate blogs are both informational and interactive. Mendhakar (2022) noted that the patterns in MD can be used to predict the genre to which a text belongs. They reveal that MD analysis is effective for studying recent texts for commercial purposes, primarily in the area of strategic communication.

In marketing, the brand’s voice refers to using a consistent personality and tone across all channels. The brand personality model developed by Linsner et al. (2021) aligns well with the language expressions used. Surikova et al. (2022) point out that brand equity is built on the strength of a brand’s voice. According to Kervyn et al. (2021), pronouns and relational language shape people’s views of warmth and honesty in conversations. Chan (2022) believed that brands are partners in relationships, so effective communication should include traits such as empathy, active listening, and attention. Building relationships in language is shown by using “you,” an informal style, and expressions such as “we believe…”.

Rohach and Rohach (2021) find that ads create an illusion of a conversation by using rhetorical questions, commands, and everyday speech. Likewise, Cheng and Li (2024) believe that a brand’s tone should remain consistent across all platforms, but it should also adapt to suit each platform’s unique style. Ipaki et al. (2018) talk about the role of metaphor and identity in branding companies. Kwao et al. (2025) note that microblogging facilitates connections through the use of language. According to Mukhopadhyay and Jha (2025), utilising stance and engagement cues is essential for aligning a brand with its followers.

Foster et al. (2025) recently discovered that emotional and informal Facebook posts encourage people to interact more. Chaudhary (2022) also stated that using humour, emojis, and cultural references in social media posts helps build intimacy with others. According to Saikia and Bhattacharjee (2024) brands have a long-lasting impact on consumers that bonds a feeling of commitment and love. Alshammari (2025) argued that social interactions influence communication in a business context, and Yasin et al. (2025) demonstrated that using appropriate language enhances trust in marketing materials. This means that the way information is presented matters as much as the information itself.

Various studies using Multidisciplinary Discourse Analysis, Critical Discourse Analysis, sentiment analysis, and models of brand personality have been conducted on the influence of language in branding; however, few examine whether global brands apply the same voice and styling to different digital platforms. Most studies look at brands only in a single context or for one industry, rather than studying brand conversation on complementary distribution. For this reason, this study employs Biber’s MD analysis to examine how Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever utilise language in their websites, advertising, and social media to maintain a strong and consistent brand image.

H1 states that the type of content (advertisements, social media posts, and website content) exhibits significant systematic variation in its lexicogrammatical patterns. H2 argues that the lexicogrammatical choices of brand communications differ considerably between the companies (Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever). By applying Biber’s Multidimensional Analysis, this study intends to show that each company and each type of content employs distinct lexicogrammatical patterns, which provide an accurate linguistic fingerprint for each platform.

3. Methodology

3.1. Corpus Collection

The present study compiled a corpus of texts from the top five global brands: Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez International, and Unilever. The companies chosen appear in the Effie Global Top 100 and are active on a range of media platforms, making them representative of highly effective global marketers.

The scope of sampling was restricted to five of the world’s leading consumer brands—Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever—and three major communication channels: social media, video advertisements, and website content. These five companies were chosen on the basis of their ranking in the Effie Index Marketers 2023 (Effie Awards Index, 2023), which provides a globally recognized benchmark for marketing effectiveness. Although AB InBev was ranked first in the Effie Index, it was excluded from the study due to cultural considerations, leaving the next five leading companies as the focus of analysis.

The text sample for this study was chosen by applying the criterion-based sampling method. Official and publicly available sources for each brand were identified, including verified social media accounts, company websites, and official video advertisements shared on online platforms. To guarantee authenticity and consistency, only original texts written by the brands themselves were used; consumer comments, reposts, and third-party media content were not used.

From each brand, a balanced set of 15 social media posts, 15 video advertisement transcripts, and 15 website texts was collected, ensuring comparability across both companies and platforms. In total, the corpus comprised 225 texts, with 45 texts per company and 15 texts per channel. All texts were taken from the period 2020–2024 and limited to English-language material. This time frame was chosen as it represents the most recent stage in which these companies appeared in the Effie Global Top 100 Index, corresponding to their award-winning and globally recognized communication strategies. Aligning the sampling frame with this recognition strengthens the study’s relevance by ensuring that the texts analyzed reflect the latest, most effective, and most strategically significant brand communication practices.

The corpus comprises 225 texts, totalling approximately 50,000 words. Table 1 shows the different types of content and brands in the corpus. The content types are well-represented for each company. The majority of social media posts were brief, but other web texts, such as blog posts or press pages, were longer. To solve this, several short social media posts were combined, and long web articles were edited. All the texts were written in English. The first step was to tokenise and tag the text to facilitate the analysis.

Table 1.

Corpus composition by content type and company (number of texts).

3.2. Multidimensional Analysis Procedure

The study uses Biber’s Multidimensional (MD) framework, a corpus-based statistical model that groups co-occurring linguistic features into dimensions to reveal functional patterns of variation across texts. This model assumes that the use of language is not arbitrary and is determined by communicative purpose and that the number of large groups of linguistic features is reduced to interpretable dimensions that represent the underlying functions of discourse. Because the scoring process is entirely computational, it eliminates human intervention and subjectivity, allowing linguistic variation to be decided statistically. This makes the approach reliable and trustworthy, as results are based on objective, replicable measures rather than manual interpretation. The current paper looks at the initial five dimensions developed by Biber (1991).

Dimension 1 is named “Involved vs. Informational Discourse.” A high score suggests that the text is written in an engaging, interactive manner, using words like ‘I’, ‘you’, and ‘we’, as well as personal verbs, contractions, and emphatics. A negative score means the text is informative and impersonal (e.g., it uses more nouns, prepositions, and descriptive adjectives). Dimension 2 is referred to as “Narrative versus Non-narrative discourse”. High scores are typically found in texts that tell a story, as they often employ the past tense and third-person pronouns; conversely, negative scores are observed in texts that explain concepts. Dimension 3 is referred to as “Explicit vs. Situation-Dependent Discourse.” If the score is high, the text uses many details and specific phrases.

In contrast, a negative score indicates that the text relies heavily on context for its meaning. Dimension 4 is named “Overt Expression of Persuasion”. When a text achieves a high score, it suggests that its writing is persuasive or argumentative (because it often uses infinitives, modal verbs, conditional subordinators, and suasive verbs). Low scores indicate that the writing lacks many persuasive elements and tends to employ narratives or expository styles. Dimension 5 is called “Abstract or Non-Abstract discourse”. A positive score suggests that the writer tends to express ideas using impersonal and abstract structures, such as adverbials, passive forms, and nominalisations. When the score is negative, the writing is more direct, personal, and typically does not include abstract language or complex tools.

To operationalise the MD model, the study calculated dimension scores for each text using a systematic corpus-based procedure. It tagged the texts for the necessary linguistic features using a tool, the Multidimensional Analysis Tagger. The frequency of each feature was calculated for each text and normalised to 1000 words. The study used the factor loadings from Biber (1991) to compute the dimension score by assigning weights to each feature based on its contribution to that dimension. A positive-weight feature boosts the score, while a negative-weight feature reduces it. If the score is positive, the text exhibits more of that dimension than an average text; if the score is negative, the text exhibits less of it.

After completing the scoring, the study looked at the average scores for each content type and each company. It used one-way ANOVA to check for significant differences in each dimension: (a) by comparing the three types of content (Adverts, Social Media, Website Content) and (b) by comparing the five brands. For each ANOVA, the dependent variable was the dimension score for each text, while the independent variables were the type of content and the company/brand. To ensure the variances were equal, the study used Levene’s test; if this was not the case, the study rechecked the results with Welch’s ANOVA. If the overall F-test yielded a significant result (p < 0.05), the study used Tukey’s HSD test to identify the groups whose means differed. The analyses were done using SPSS 27. Mean and standard deviation values for each group’s dimensions were calculated to facilitate an understanding of the results. Qualitative interpretations were based on the quantitative results.

The findings and the information are transformed into a compelling story narrative that engages and enriches in finding the insights. It is shaped into applied research that elevates interest in researching further. This makes a profound impact by actually applying the theoretical conceptualization, hypothesis development, and empirical findings (Wang, 2025a, 2025b).

4. Results

The analysis first explains the general style of the brand’s communications across every dimension and then highlights the differences between content types and companies. Table 2 shows the average scores for dimensions by content type (for all brands), and Table 3 shows the average scores by company (for all content types).

Table 2.

Mean dimension scores (and standard deviations) for advertisements, social media posts, and website texts across the five brands.

Table 3.

Mean dimension scores (and standard deviations) for each brand (Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever) across the five linguistic dimensions.

They show the differences in the data. Table 4 presents the ANOVA results for each dimension, indicating which differences are statistically significant.

Table 4.

Results of one-way ANOVA tests showing differences in linguistic dimension scores across content types (advertisements, social media posts, and website texts).

4.1. Variation by Content Type

Table 2 shows that video advertisement transcripts, social media posts, and website content have different styles in certain areas. The most significant difference is observed on Dimension 1 (Involved vs. Informational). The results indicate that advertisements are much more involved with style (Mean = 10.35) than social media posts (Mean = −10.82) and website content (Mean = −3.04). So, ads here employ a more interactive and personal approach, while social media posts tend to be more informative. The results of the ANOVA in Table 4 demonstrate that content type affects Dimension 1 (F(2218) = 37.69, p < 0.001). The post hoc Tukey tests indicate that all the differences between the groups are significant: adverts are higher than both social media and website content (p < 0.001) and website content is higher than social media (p < 0.01). On average, social media posts are more informative and use fewer ways to involve the reader, whereas advertisements are the most engaging and interactive.

The results indicate that advertising texts often rely on second-person pronouns, instructing readers to take action and using strong emotional language, which helps keep the reader engaged. This is consistent with research by Fernández-Cavia (2025) on advertising, which reveals that many copywriters prefer to address readers directly. Refer to Figure 1. Interestingly, most of the social media posts had a plain, straightforward style. Many of them were written in an announcement style (for example, “We have opened a new store in Chicago” or “Nutrition facts: …”). As a result, D1 scores were strongly negative, indicating that the company focused on conveying information. The website content was somewhere in the middle: it was less casual than ads but not as short as tweets. It appears that the language used by brands varies significantly by channel, as their objectives differ across platforms. Ads try to get people’s attention and influence them rapidly (so they are written with a more involved style). At the same time, social media posts are generally brief updates, despite social media being thought of as a platform for conversation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean dimension scores across content types (advertisements, social media posts, and website texts).

All three content types are negative on Dimension 2 (Narrative vs. Non-narrative), indicating a non-narrative style, as expected, since brands rarely use stories in these contexts. The means are between −2.7 and −3.9, and as shown in Table 4, there is no significant difference between them (F(2218) = 0.68, p = 0.506). None of the content types relies heavily on narrative discourse; instead, they focus on explaining and persuading their audience. It is not surprising, since most social media stories in marketing are brief and focused on advertising, rather than personal experiences. This means that all content types on Dimension 2 have a non-narrative style, with no significant differences.

Dimension 3 (Explicit vs. Situation-Dependent Reference) does vary significantly by the type of content (F(2218) = 10.09, p < 0.001; see Table 4). The mean score for online ads is much lower (1.17) than for social media (6.07) and website content (6.66). If the score is high, it likely uses relative clauses and nominalisations to give many background details, but a low score tends not to do this. According to Tukey’s post hoc test, advertisements are significantly different from social media and website content. Still, social media and website content are not different from each other (p = 0.90). In other words, both social media posts and website texts use an open and detailed style of writing. At the same time, advertisements are more likely to be brief and tailored to the specific situation.

On dimension 5, there was no significant difference in Abstract vs. Non-Abstract Style based on the type of content (F(2218) = 1.48, p = 0.231). All kinds of content have scores close to zero or slightly below, and the variability is most significant for “Others,” as shown in the standard deviation (SD) in Table 4. It means that the use of abstract, impersonal language (such as nominal style and passives) is not always different in ads, tweets, or web pages. In every case, the communications blend abstract words (mainly in corporate talks or discussions about values) with more concrete terms (used to describe products or users). Since the ANOVA is not significant, the type of content channel does not have a strong influence on the abstractness of language in the data. An ad slogan could be particular (“Ice-cold refreshment”) or more abstract (“Open happiness”—Coca-Cola’s well-known tagline). A social post could also highlight major subjects, such as sustainability or community, or focus solely on a new flavour or store. It seems that the choice between abstract and concrete expression depends more on the message or subject than on the medium.

In conclusion, advertisements are more involved in their writing but are less elliptical or situation-based than website content. The sample’s social media posts were the most informative (D1 low) and as explicit as the web content (D3 high). Website content, such as web pages, was positioned in the middle for involvement and had a similar level of explicitness as social content. Persuasion markers and abstractness did not differ significantly across the types of arguments. Probably, these patterns result from the way each channel allows for communication: ads make quick impressions with a limited number of words, social posts deliver short bits of information, and web content provides all the details.

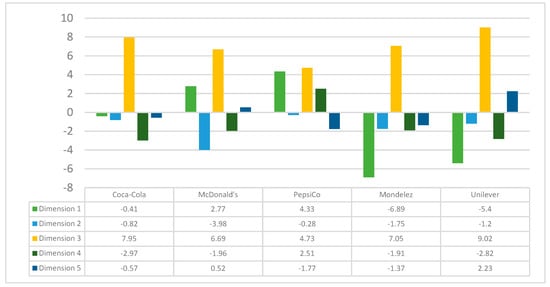

4.2. Variation by Company

This part of the analysis examines the five companies—Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever—on Biber’s five dimensions. As shown in Table 5, there are differences in the scores, and the ANOVA results indicate that these differences are statistically significant.

Table 5.

Results of one-way ANOVA tests showing differences in linguistic dimension scores across the five companies (Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever).

On Dimension 1, the companies exhibit statistically significant differences (F(4216) = 3.72, p = 0.006) among themselves. Some brands use more personal and interactive language than others. PepsiCo had the most D1 score (i.e., 4.33), with McDonald’s with a mean score of 2.77 coming in second and Coca-Cola (−0.41) close behind. In comparison, Unilever (−5.40) and Mondelez (−6.89) received negative scores, indicating that they tend to write in a more informational manner. The analysis of Tukey pairwise comparisons found that the difference between PepsiCo and Mondelez is statistically significant (mean difference ≈ 11.21, p = 0.017). PepsiCo’s communications are much more involved than Mondelez’s. There was nearly a substantial difference between McDonald’s and Mondelez (diff ≈ 9.65, p = 0.065) and between PepsiCo and Unilever (diff ≈ 9.73, p ≈ 0.03 by Welch test). Tukey tests did not find any significant differences between Coca-Cola and any of the other brands. The findings indicate that PepsiCo and McDonald’s use a more involved style, while Mondelez and Unilever prefer to share information; Coca-Cola is somewhere in between.

Most customer engagement in the digital era reflects the interactions of social media but also considers the essence of the development of strong, long-lasting consumer relationships (Herrada-Lores et al., 2025; Saikia & Bhattacharjee, 2024).

PepsiCo is marketing its brands and products for the youth, thus making a remarkable impact globally (Marx et al., 2022). On the other hand, McDonald’s frontal attacking strategy shifted to serving a nutritious menu to cater to the masses, making it more universally acceptable (Singireddy, 2020).

Mondelez company brands have stressed reducing CO2, water usage, and manufacturing wastages that would create a long-term benefit not only to the company but to the stakeholders at large (Tarczydło et al., 2023). Unilever’s brands’ integration of value-based strategies in the contemporary business micro and macro environments factors through the broader guidelines of the initiative taken by them, i.e., Unilever Sustainable Living Plan (USLP) (Tan, 2025).

Coca-Cola instills emotions with experience all the time again and again. It is a product like a man. It needs to be revived, to build personality, and to be attractive (Smilevska, 2024).

Refer to Figure 2. The mean score for PepsiCo on dimension 1 is the highest because its brand voice is engaging, youthful, and fun, leading to more involvement features in its ads and social media. McDonald’s often speaks in a friendly, informal way in many of its advertisements (“I’m lovin’ it” is a good example). On the other hand, Mondelez, which markets snack brands and often shares information about its initiatives, tends to use a simple factual approach. Since Unilever is a large company that frequently discusses sustainability and its values, it may employ a more informational style in many of its communications, resulting in a lower D1 score. Coca-Cola employs emotional advertising, but its average score was close to zero, which may suggest that while its ads are emotional, its other content, such as press releases, is not. PepsiCo stands out the most, as it is more personal and involved.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean dimension scores across the five companies (Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, PepsiCo, Mondelez, and Unilever).

On dimension 2, there were no noticeable differences among the companies (F(4216) = 0.77, p = 0.545). All brands had a negative score on D2 (ranging from −0.3 to −4.0; see Table 3), showing that none of them use storytelling in their marketing to customers. The slight differences (with McDonald’s at −3.98 being the lowest, indicating the least narrative) may be due to how each brand presents its information; however, the ranking is not statistically significant. All five brands emphasise non-narrative speech, using present-tense statements, descriptions, and commands instead of sharing stories or details about past events. This follows the advertising style of the genre, as stories are not the primary focus in these materials.

On Dimension 3, Unilever scored the highest (9.02), while PepsiCo scored the lowest (4.73), and the other companies had means ranging from 6 to 8 (Table 3). However, the ANOVA for D3 by company came very close to the conventional significance level (F(4216) = 1.916, p = 0.109). Even though Welch’s test was close to the limit (p = 0.049), Tukey HSD discovered that no combination between the groups was significant. This indicates that there is not much evidence that companies differ in how explicit they are when referring to themselves. Even so, it seems that Unilever’s texts are more complex (possibly because they often explain sustainability or health plans, using more clauses and nominalisations). Alternatively, PepsiCo’s tone might be more direct, suited to a younger audience since the test result is not significant at the 0.05 level. Most brands were found to have positive scores, which is understandable since the content is designed to be straightforward.

The most significant differences between companies were found on Dimension 4, specifically in the area of persuasion. In this case, the one-way ANOVA was significant (F(4216) = 3.30, p = 0.012), and the means show that PepsiCo is an outlier with a high score. PepsiCo’s D4 mean score is 2.51, while all other companies had negative scores, ranging from approximately −1.9 to −2.97. In Table 5, post hoc tests confirmed that PepsiCo’s D4 score is higher than both Mondelez’s and Unilever’s, and the difference is statistically significant (p = 0.029 and p = 0.012). This means that PepsiCo’s brand messages are more persuasive in this way than those of some of its competitors. Even though the differences between PepsiCo and Coca-Cola, or McDonald’s, were not significant (p > 0.1), Pepsi (2.51) still had the highest mean of all. Unilever had the lowest (−2.82) mean scores.

According to the findings, PepsiCo often uses language that directly urges people to buy, such as “you should try…”, “Don’t miss out”, “will improve”, or conditional statements. The company often employs marketing strategies that appeal to young people by using strong phrases and commands (e.g., the “Live for now” campaign)—this language frequently includes prediction modals (“will”), imperatives/infinitives (“Get to experience”), and so on. Unilever may tend to mention both corporate responsibility and facts about its products rather than try to persuade, which explains the brand’s lower D4 score. Mondelez, too, tends to discuss its snack brands and recipes straightforwardly, rather than using strong encouragement. It is surprising that Coca-Cola, which relies on emotions, did not do well on D4, as it uses emotions and pictures instead of direct language to persuade. McDonald’s employed both straightforward promotions and emotional branding, which resulted in average persuasive features. The study finds that PepsiCo tends to use more obvious persuasive language than some of its competitors, such as Unilever and Mondelez, which reflects the company’s bold marketing approach.

The differences between companies on Dimension 5 (Abstract vs. Non-Abstract) were not significant. The ANOVA found F(4216) = 2.342, p = 0.056, which is very close to the significance cutoff. The means (Table 3) reveal that Unilever is slightly more likely to use abstract, impersonal language (+2.23), whereas PepsiCo uses the most concrete and personal words (−1.77). At α = 0.05, all five brands were placed together as a homogeneous subset, but Unilever’s mean was separated from Pepsi’s. When the study examines the trend, it appears that Unilever’s messages are more formal and abstract, while PepsiCo’s are more focused on specific products, flavours, and youth experiences. Coca-Cola and McDonald’s had mean scores that were just slightly below zero. Even so, because p is 0.056, the brand effect on D5 might be significant if the study had a larger sample; however, for now, it concludes that there is no firm evidence of a difference. Except for Unilever, all brands have negative scores (except McDonald’s, which shows mixed-purpose discourse), as most marketing copy, even in business, avoids being too abstract to keep consumers interested.

PepsiCo’s brand-based results highlight its linguistic uniqueness, with the highest scores on D1 (involvement) and D4 (persuasion). Unlike Coca-Cola, Mondelez, and Unilever, which prefer to share information rather than persuade their readers (lower D1 and D4). All brands use a non-narrative approach (D2 low). The differences in how explicit or abstract the language was (D3 and D5) were not significant, but Unilever used more explicit and abstract language. The research suggests that some corporations employ more personal language, while others opt for a more formal approach, and these differences align with each brand’s character and marketing strategy.

The results of the present study support the hypotheses of the proposed research. H1, which posited that the linguistic style of the brand communications varies depending on content type, was proved. The results indicate a statistically significant difference in Dimension 1 (Involved vs. Informational Discourse), with the advertisements being highly involved, social media posts being informational, and the website’s content taking an intermediate stance. These differences were proved significant (p < 0.001) by ANOVA and Tukey HSD results. This proves the fact that the communicative channel is a potent factor of linguistic variation in brand discourse.

H2 suggested that the linguistic style of brand communications varies considerably between companies, which was supported by the results as well. Dimensions 1 and 4 were found to differ, with PepsiCo and McDonald’s being more involved and persuasive in their discourse, whereas Mondelez and Unilever were more informational. Even though not all dimensions, including D2 and D5, revealed an important brand-level effect, the findings, in general, reveal that brand identity shapes stylistic trends in corporate communication.

Overall, the results reveal clear patterns of linguistic variation across both content types and companies. Advertisements are highly involved, while social media posts are strongly informational, and website texts lie between. Social media and website content are more explicit, thereby supporting H1. At the company level, PepsiCo and McDonald’s use a more involved style, while Unilever and Mondelez favor a more informational approach. Unilever scores highest on explicit language and abstract style, whereas McDonald’s shows the lowest narrative score, which aligns with H2. These findings confirm that brand identity and communicative channel jointly shape distinctive stylistic trends in corporate discourse.

5. Discussion

This multidimensional analysis reveals how linguistic choices in brand communication reflect the underlying strategic objectives of companies across various platforms. The data highlights several key trends that illustrate how different content types and corporate identities shape language use. One of the most prominent findings concerns the influence of content type on linguistic style. Specifically, advertisements in the corpus were notably more involved and non-abstract, whereas social media posts, contrary to popular assumptions, were found to be considerably more informational.

This contrast challenges the widespread belief that social media is primarily an informal domain. Instead, our results suggest that top-tier brands strategically use social platforms not only for casual interactions but also for broadcasting succinct updates, announcements, and corporate news. Several factors may influence this pattern. For instance, the character limitations inherent in platforms like Twitter (now X), the visual dominance of platforms like Instagram, and the need to maintain consumer attention in a fast-paced digital environment encourage brevity and clarity. The concise nature of social posts, often characterised by their simplicity and avoidance of elaborate sentence structures or emotional appeals, reflects a deliberate effort to convey information efficiently.

By contrast, advertisements are designed to attract attention and elicit emotional responses from viewers. These texts commonly feature a high density of personal pronouns, direct imperatives, emotionally charged adjectives, and stylistic devices that simulate conversation, features aligned with Biber’s Dimension 1 (Involved vs. Informational). This linguistic characteristic of face-to-face interaction, often referred to as the “pseudo-dialogue” of advertising (Cook, 2001), helps advertisers construct a sense of immediacy and personal relevance. This conversational tone can be particularly effective in engaging readers, prompting emotional responses, and ultimately fostering brand loyalty.

Interestingly, the study’s data revealed that social media content, although sometimes phatic (e.g., using greetings, hashtags, or slogans), did not score high on D1. This could be due to the nature of the samples analysed; highly interactive forms of social engagement, such as banter in comment threads, personalised replies, or humorous memes, may have been underrepresented. Future research would benefit from a more granular categorisation of social media content, distinguishing between routine announcements, customer service interactions, and entertainment-driven posts (Koo, 2022).

A second significant finding centres on Dimension 3 (Explicit vs. Situation-dependent). Advertisements emerged as nearly situation-dependent, relying more heavily on the audience’s ability to infer meaning from context, visuals, and shared cultural knowledge. This aligns with the nature of visual media: a minimalist tagline, such as “Never Settle,” when paired with evocative imagery, can communicate a product’s superiority or lifestyle association without explicitly stating it. In contrast, social media posts and web content communication tend to be more explicit, employing complete sentences and clarifying clauses to ensure comprehension in the absence of accompanying visuals.

This contrast highlights the significance of context in determining language choice. High-context formats, such as video ads or Instagram stories, afford brands the flexibility to be concise in text while relying on visual storytelling. When communicating on corporate websites, through press releases or in stand-alone social media posts, the text needs to be more informative. This approach aligns with the principles of integrated marketing communications (Ang, 2021), where each channel supports the others, and the language is tailored to suit each one. The present study demonstrates that brands tailor their language to fit the unique characteristics of each communication channel.

The investigation revealed that brands develop their unique styles of communication, which reflect their market position. PepsiCo was found to be both highly interactive and persuasive. It fits with the brand’s lively and youthful image. Advertisers often use the word “you” and imperative verbs, together with encouraging phrases such as “You got this” or “Live for now,” to inspire their audience. Because of these features, brands tend to score high on Dimensions 1 and 4 (Involved and Persuasive), which can lead to increased emotional involvement and improved recall. Alternatively, Unilever and Mondelez used a more informative approach. The company’s language is similar to that used by corporations, which aligns with its focus on sustainability, health, and responsibility. This means using precise language to show that a company is sincere, credible, and transparent, which is important to today’s ethical consumers. Mondelez, which deals more with customers, chose to be clear rather than creative, possibly because they wanted their products to be easy to understand. Slogans such as “Snacking Made Right” convey what the brand offers straightforwardly, without telling a story.

It was surprising to see that Coca-Cola scored fairly moderately. Famous for its touching ads, Coca-Cola often uses straightforward slogans like “Taste the Feeling” in its language. They employ emotional language but lack the features that Biber’s framework considers essential for persuasion. Coca-Cola’s branding relies more on associative meanings, visual storytelling, and cultural resonance than on overt linguistic persuasion, which may explain its middling scores.

McDonald’s, in contrast, achieved higher involvement scores due to its use of colloquial and inclusive language (“I’m lovin’ it,” “McD’s”), supporting its family-friendly, down-to-earth image. Research on linguistic markers of brand personality (Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010) suggests that brands perceived as “sincere” use more first-person plural pronouns and conversational tone features evident in McDonald’s texts. This style fosters relatability and trust, particularly important for brands that market to families and diverse demographic groups.

An additional insight is that nearly all brand texts were non-narrative, scoring low on Dimension 2 (Narrativity). Despite the popularity of “brand storytelling” in marketing rhetoric, the analysis shows that short-form texts rarely employ narrative grammar. Instead, stories are implied visually or constructed across multiple forms of communication. Even video ads with clear storylines often feature non-narrative captions. Present-tense, generic language (“Moments like these matter”) prevails, maximising relatability and avoiding specificity that might alienate segments of the audience. This suggests that narrative branding is more of a thematic construct than a grammatical one.

Finally, our MD analysis confirms the presence of consistent, genre-based linguistic variation within branding discourse. Dimensions 1 (Involved), 3 (Explicitness), and 4 (Persuasion) provided the clearest differentiators across both media and brand identity. These findings correspond to the broader marketing literature on communication styles—whether hard-sell, soft-sell, emotional, or rational. Interestingly, Dimension 5 (Abstractness) was less prominent, perhaps because all brands analysed belong to the CPG (consumer packaged goods) sector, where concrete and sensory language is favoured. Abstractness may become more salient when comparing across industries, such as finance or technology.

The study offers an implication for using linguistic profiling in AI-driven marketing tools. With the growth in the number of generative language models being used to generate brand content, an MDA-based approach can help such systems adapt generated text to a brand voice. This not only creates more consistent automated communications but also enables the creation of AI-based evaluators to score or flag texts on the basis of how well they adhere to desirable linguistic dimensions. In essence, this AI and linguistic analysis will be more advanced and brand-consistent automated marketing in future.

By applying an MDA-based methodology, these systems can more effectively align generated texts with the distinctive voice of a brand. At the same time, the findings connect to research on electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), which demonstrates that linguistic framing strongly influences how consumers share, recommend, and amplify branded content (e.g., Berger, 2014; Kozinets et al., 2010; Peres et al., 2011). This suggests that the lexical-grammatical patterns identified here can be leveraged not only to train AI systems but also to enhance the effectiveness of WOM strategies. In turn, this contributes to more consistent and coherent automated brand communications.

This study reinforces the importance of linguistic adaptability in brand communication. Brands demonstrate pragmatic competence in adapting their linguistic style to suit the medium, audience, and strategic purpose. Biber’s multidimensional approach proves effective in capturing these variations, offering a framework for future research on digital discourse and commercial language. As marketing continues to evolve across new platforms, such analytical tools can help unpack the subtleties of how language constructs brand identity, fosters engagement, and drives consumer behavior.

While the present study offers a comprehensive multidimensional examination of linguistic variation across leading global brands, several methodological boundaries inevitably suggest future avenues for inquiry. First, the analysis focused on five high-performing consumer brands and three major digital channels. As noted by Wang (2025a, 2025b), clearly defining the scope of inquiry is essential, but such boundaries naturally open opportunities for follow-up studies. Future research may therefore benefit from extending MD-based comparisons to additional sectors, such as technology, luxury, or financial services, to determine whether similar stylistic patterns hold in domains with different communicative norms.

Second, contemporary digital environments increasingly integrate hybrid human–AI communication. Yoo et al. (2025) highlight how textual cues shape perceived credibility in interactions involving human-like virtual agents. Building on this insight, further studies could investigate how AI-generated brand messages, automated customer service discourse, or virtual influencers align with or diverge from the lexicogrammatical tendencies identified in human-produced brand content.

Third, the dataset represents a cross-sectional snapshot (2020–2024). Although this period captures current marketing practice, longitudinal corpora would allow researchers to observe how brand language adapts to evolving digital platforms, cultural shifts, or emerging communication formats.

Finally, the analysis centred on linguistic patterns rather than consumer interpretation. Future research could integrate MD analysis with behavioural metrics, such as engagement rates or perceived credibility, to explore how specific linguistic dimensions influence audience response.

Together, these directions reflect natural extensions of the present study and outline how subsequent research can deepen understanding of linguistic variation in strategic brand communication.

6. Conclusions

This study provided a multidimensional linguistic profile of strategic brand communications, revealing how top global brands shape their messaging across multiple stylistic fronts and the lexicogrammatical features they employ. Through a corpus-based analysis using Biber’s MD model, the study found that content type exerts a strong influence, with advertisements employing a highly involved, implicit style and social media posts tending toward an informational, explicit style, reflecting the distinct communicative demands of each channel. Statistical results indicated that involvedness (D1), persuasion (D4), and abstractness (D5) differed significantly between both brands and platforms, highlighting these as key lexicogrammatical levers in strategic communication. In comparison, narrativity (D2) and explicitness (D3) were relatively constant, which indicated that the style of storytelling and the dependence on contextual clues were the constant characteristics of brand discourse across media. The study also revealed meaningful differences between brands; some, such as PepsiCo, consistently use more persuasive language, whereas others, like Mondelez and Unilever, favour a more neutral and informative tone. These differences align with each brand’s marketing persona and strategy, illustrating that linguistic choices are a crucial part of constructing a brand identity.

The research contributes to both marketing and linguistics domains. For marketing practitioners, the findings highlight the importance of tailoring language to the medium and brand voice. Subtle shifts in phrasing—using “you” vs. avoiding it, choosing a slogan vs. a descriptive sentence—can cumulatively signal a brand’s personality (friendly vs. authoritative) and affect consumer engagement. Brands that excel in communication appear to modulate these features to reinforce their image consciously; for instance, a brand aiming to be seen as youthful might deliberately use more conversational syntax across all channels. For linguists and discourse analysts, this study extends multidimensional analysis into the realm of corporate communications, demonstrating that even within persuasive discourse there are multiple dimensions of variation that correlate with communicative intent (e.g., selling by logic/information vs. selling by emotion/engagement). It also underscores the value of MD analysis as a tool for quantitatively mapping those variations and connecting them to social-functional interpretations.

Meanwhile, a number of limitations are to be mentioned. The first being that the corpus has been reduced to five companies and three forms of digital content, which decreases the generalisability of the results. Linguistic styles may be different in other industries (e.g., luxury, technology, or non-consumer goods). Second, this research was based on the texts written in the English language, which does not include multilingual brand communication that could show more stylistic variation. Third, although the analysis found statistical differences between the dimensions, it did not directly quantify consumer reception, i.e., the association between linguistic characteristics and real viewer response is still inferential. Finally, the corpus was cross-sectional (2020–2024), and, therefore, does not show long-term linguistic changes or adaptation to new cultural contexts.

There are several avenues for further research. One approach would be to expand the dataset to include more brands and industries (technology brands, for instance, might employ different styles, while luxury brands might use more formal language, etc.) to determine if the patterns hold or if new dimensions emerge. Another worthwhile pursuit is a diachronic analysis: brand language likely evolves (for example, the rise of social media has generally made brand tone more casual since the 2010s). Applying MD analysis to historical brand corpora could quantify these shifts (as hinted by Biber’s work on historical change in registers). Additionally, incorporating consumer response data (such as engagement metrics or brand perception surveys) could validate whether the linguistic differences the study measured have tangible effects on consumer attitudes—for instance, does a higher D1 score correlate with higher social media engagement or brand “likeability”? Early evidence suggests that this is indeed the case, as more involved language fosters a stronger brand attitude; however, direct correlations in real-world brand contexts would be enlightening. Future research could also investigate how linguistic features, particularly lexical and grammatical preferences, vary between top-performing and lower-ranked brands to determine whether specific discourse strategies correlate with marketing success.

In summary, language is a powerful and flexible tool in the branding arsenal. The research in this study demonstrates that utilising various linguistic features in combination is essential to achieve optimal results and foster a strong relationship with consumers. Because brands now communicate in many different ways and across multiple cultures, utilising these linguistic aspects will be essential to maintain a consistent and flexible brand voice.

Funding

This research was funded by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University grant number [PSAU/2025/R/1447].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw anonymized data supporting the findings of this study are available on FigShare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30192937.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahuvia, A., Izberk-Bilgin, E., & Lee, K. (2022). Towards a theory of brand love in services: The power of identity and social relationships. Journal of Service Management, 33(3), 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Falaq, J. S., & Puspita, D. (2021). Critical discourse analysis: Revealing masculinity through L-men advertisement. Linguistics and Literature Journal, 2(1), 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. (2024a). A multidimensional analysis of academic writing: A comparative study of Saudi and British university students’ writing. World Journal of English Language, 14(2), 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. (2024b). Reddit’s linguistic diversity evolution: A multivariate study. Lege Artis. Language Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow, 9(1), 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M. M. (2025). Beyond the image: A quantitative investigation of effects of public relations strategies on personal branding, communication practices, and reputation management. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 15(1), e202509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, L. (2021). Principles of integrated marketing communications. Macquarie University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D. (1991). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D. (2006). University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D., & Egbert, J. (2016). Using multi-dimensional analysis to study register variation on the searchable web. Corpus Linguistics Research, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D., Larsson, T., & Hancock, G. R. (2024). Dimensions of text complexity in the spoken and written modes: A comparison of theory-based models. Journal of English Linguistics, 52(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T. H. (2022). How brands can succeed communicating social purpose: Engaging consumers through empathy and self-involving gamification. International Journal of Advertising, 42(5), 801–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A. (2022). Visual language of communication: Comics, memes, and emojis. International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences, 7(3), 001–005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., & Li, S. (2024). Fast fashion clothing brand marketing strategy: Take a fast fashion clothing brand called Uniqlo as an example. Finance & Economics, 1(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I., & Grieve, J. (2017, August 4). Dimensions of abusive language on Twitter. First Workshop on Abusive Language Online (pp. 1–10), Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, I., & Grieve, J. (2019). Stylistic variation on the Donald Trump Twitter account: A linguistic analysis of tweets posted between 2009 and 2018. PLoS ONE, 14(9), e0222062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G. (2001). The discourse of advertising (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Diwanji, V. S., Baines, A. F., Bauer, F., & Clark, K. (2024). Green consumerism: A cross-cultural linguistic and sentiment analysis of sustainable consumption discourse on Twitter (X). Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 45(4), 476–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. R. (2010). Mapping the world of consumption: Computational linguistics analysis of the Google text corpus. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effie Awards Index. (2023). Most effective marketers 2023. Available online: https://www.effieindex.com/ranking/?rt=6 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Feng, W., Xu, Y., & Wang, L. (2024). Innocence versus coolness: The influence of brand personality on consumers’ preferences. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 33(1), 14–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cavia, J. (2025). Playing with words. In Advances in marketing, customer relationship management, and e-services (pp. 1–20). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M. L., Egwuonwu, C., Vernon, E., Alarifi, M., & Hughes, M. C. (2025). Informal caregivers connecting on the web: Content analysis of posts on discussion forums. JMIR Formative Research, 9, e64757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrada-Lores, S., Palazón, M., Iniesta-Bonillo, M. Á., & Estrella-Ramón, A. (2025). The communication of sustainability on social media: The role of dialogical communication. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 19, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipaki, B., Movahedi, Y., & Amirkhizi, P. J. (2018). A research on the use of metaphor design in promoting brand identity. Journal of Graphic Engineering and Design, 9(2), 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervyn, N., Fiske, S. T., & Malone, C. (2021). Social perception of brands: Warmth and competence define images of both brands and social groups. Consumer Psychology Review, 5(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K. (2022). Phatic brand communication on social media [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta]. [Google Scholar]

- Koteyko, I. (2015). The language of press advertising in the UK. Journal of English Linguistics, 43(4), 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R. V., De Valck, K., Wojnicki, A. C., & Wilner, S. J. (2010). Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-Mouth marketing in online communities. Journal of Marketing, 74(2), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwao, L., Yang, Y., Zou, J., & Ma, J. (2025). A survey of approaches to early rumor detection on Microblogging platforms: Computational and socio-psychological insights. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 15(1), e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsner, A., Sotiriadou, P., Hill, B., & Hallmann, K. (2021). Athlete brand identity, image, and congruence: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 21(1/2), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K., Greenthal, E., Ribakove, S., Grossman, E. R., Lucas, S., Ruffin, M., & Benjamin-Neelon, S. E. (2022). Marketing of sugar-sweetened beverages to youth through U.S. university pouring rights contracts. Preventive Medicine Reports, 25, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendhakar, A. (2022). Linguistic profiling of text genres: An exploration of fictional vs. non-fictional texts. Information, 13(8), 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R., & Jha, D. (2025). Building brand loyalty in the digital age: The power of social media engagement. In R. Sharma, T. Maqableh, F. Rabby, R. Sharma, & R. Bansal (Eds.), Elevating brand loyalty with optimized marketing analytics and AI (pp. 133–158). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolani, K. O. (2024). The language of fashion from a multidimensional perspective. In Digital humanities looking at the world: Exploring innovative approaches and contributions to society (pp. 75–85). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, R., Shachar, R., & Lovett, M. J. (2011). On brands and word-of-mouth. SSRN Electronic Journal, 50(4), 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohach, O., & Rohach, I. (2021). Manipulation and persuasion in business advertising. Research Trends in Modern Linguistics and Literature, 4, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, W., & Bhattacharjee, A. (2024). Digital consumer engagement in a social network: A literature review applying TCCM framework. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 48, e12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, T. B., & Pinto, M. V. (2019). Multi-dimensional analysis: Research methods and current issues. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, D., & Li, X. (2024). A multi-dimensional analysis of interpreted and non-interpreted English discourses at Chinese and American government press conferences. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singireddy, M. (2020). McDonald’s: Global marketing. International Journal of Health & Economic Development, 6. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/6413d45eae7d1bb6a8547dfea55792b6/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2037330 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Smilevska, O. (2024). The marketing mix of Coca-Cola. Scientific Institute of Management and Knowledge, 62, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Surikova, J., Siroda, S., & Bhattarai, B. (2022). The role of artificial intelligence in the evolution of brand voice in multimedia. Molung Educational Frontier, 12(1), 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K. H. (2025). Integrating sustainability into the corporate strategy: A critical analysis of unilever’s sustainable living plan. University of Suffolk. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarczydło, B., Miłoń, J., & Klimczak, J. (2023). Experience branding in theory and practice. Case study. In Scientific papers of silesian university of technology. Organization & Management/Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Slaskiej. Seria Organizacji i Zarzadzanie. [Google Scholar]

- Tausczik, Y. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 29(1), 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. L. (2025a). Basic but frequently overlooked issues in manuscript submissions: Tips from an editor’s perspective. Journal of Applied Business & Behavioral Sciences, 1(2), 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. L. (2025b). Editorial: Demonstrating contributions through storytelling. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, I., & Geisler, C. (2002). A multi-dimensional study of diachronic variation in British newspaper editorials. ICAME Journal, 26(1), 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., & Ren, H. (2024). A multi-dimensional analysis of corporate blogs. Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 60(2), 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z. (2009). Quantile cointegrating regression. Journal of Econometrics, 150(2), 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, R., Ariffin, Z. Z., Mohamed, H. A., Zawawi, Z., Ghani, S. A., & Liaw, J. O. (2025). Islamic values in entrepreneurial marketing strategy. Advances in Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, and E-Services, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. W., Park, J., & Park, H. (2025). How can I trust you if you’re fake? Understanding human-like virtual influencer credibility and the role of textual social cues. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).