Abstract

Digital transformation and remote work continue to reshape the nature of work, yet the implications for salaries and promotions in SMEs continue to be poorly understood. This study investigates how reward allocation mediates the relationship between remote work and employee attitudes, addressing the organizational challenges of aligning human resource practices with digitalization work models in the European context based on the social exchange theory and data collected from n = 615 participants, primarily from SMEs, which were analyzed using PLS-SEM software and WarpPLS 7.0. The findings reveal that remote work not only strengthens workers’ engagement and satisfaction but also channels their efforts toward achieving outcomes and reward allocation, reducing the reliance on physical presence and visibility. Digital transformation enables SMEs to adopt more flexible and fairer HR practices, with remote work also contributing to organizational resilience, employee agility, and competitiveness. This research advances the theoretical understanding of HRM in the context of digital transformation, offering SMEs a guide to building a suitable reward system that promotes both individual well-being and sustainability.

Keywords:

digital transformation; promotion policies; remote work; salaries; SMEs; reward allocation JEL Classification:

M1; O3

1. Introduction

Digital transformation is reshaping the organizational landscape and how European SMEs organize work, distribute rewards, and manage people (). In this context, the adoption and integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) play a crucial role in transforming traditional work settings, introducing a new format for coordinating and collaborating with people (). To address these changes, organizations resort to digital transformation, which enables them to be more flexible, introduce new benefits, and develop new business models (). The adoption of remote work in SMEs is not only a cost-saving measure but also a strategic adaptation that enables digital technologies, helping them to be competitive and flexible in volatile environments () and allowing workers to carry out their activities and tasks remotely beyond the confines of an office (). Remote work offers significant benefits, including autonomy, reduced working hours, improved work–life balance, cost savings, and enhanced employee retention (; ; ). However, it adversely affects employee well-being, including overwork, negative emotions, gender labor division, gender discrimination, and stress, which could lead them to underperform and create an organizational crisis (). As a result, it leads to anxiety and worries about their survival and future development and job insecurity, prompting employees to ignore ethical boundaries and unquestioningly adopt unethical behaviors (; ). In light of this statement, the study highlights two critical gaps. The first relates to the limited research on how remote work affects reward allocation, specifically salaries and promotions. The second refers to the limited understanding of how digital transformation enables remote work in SMEs, influencing employee attitudes in the European context. By understanding and addressing these gaps, the following research question was posed: How does digital transformation-enabled remote work influence reward allocation mechanisms and their impact on employee attitudes in SMEs? By answering this question, our study makes four contributions. First, we extend remote work theory to the context of SME digital transformation through the identification of mechanisms like promotions and salary functions as performance-based drivers of fairness and employee development (). Second, we provide region-specific (on the European continent) insights into the organizational implications of remote work under technological maturity levels, cultural norms, and distinct labor regulations. Third, the validation of reward allocation in the relationship between remote work and employee attitudes provides mechanisms that explain digital transformation and work models that weigh organizational behavior in SMEs. Fourth, the highlighted link between reward systems and remote work conditions integrates social exchange theory with dynamic capabilities theory. With this in mind, the paper is structured as follows: In Section 1, we present the introduction, and in Section 2, we address the theoretical framework and the development of the hypothesis. In Section 3, we describe the research methodology. Section 4 is reserved for the research findings. In Section 5, we present the discussion and conclusions. Section 6 presents the research implications, and Section 7 presents theoretical and practical implications. Section 8 presents limitations and future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Remote Work and Digital Transformation

With the growing advances of digital transformation, an increasing number of SMEs are developing innovation strategies centered on digital organizational structures to improve their processes and increase competitiveness, as digital transformation can be seen as a process of building or participating in digital platform ecosystems to drive value and market expansion (). The process of transformation can blur traditional physical boundaries to acquire heterogeneous resources while simultaneously introducing competitive economic activities and new challenges to value creation propositions (; ). In this context, organizations need to reconfigure their coordination, communication, and delivery formats to extend their boundaries beyond physical offices.

Remote work has become the solution for this reconfiguration and has increased significantly over the past few years due to the widespread adoption of modern technologies (), which have substantially improved and simplified remote collaboration and communication (). This shift has become the “new normal”, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, when organizations were forced to change their work paradigms and operational models (). Remote work has emerged as a solution for maintaining operations that are becoming increasingly flexible, allowing organizations to adapt to rapidly changing environments ().

Therefore, this new work setting should be considered an organizational model that allows employees to perform their tasks from locations outside the traditional setting, enabling them to carry out their activities and functions remotely (). While this technology offers solutions for organizations, it has both positive and negative aspects that managers should address to ensure workers’ continuous well-being ().

In the broader context of remote settings, internal stakeholders have identified several negative outcomes regarding areas such as salary adjustments (; ), workforce promotion (; ), employee engagement (; ), commitment (; ; ), job satisfaction (; ; ), and worker performance (; ). On the other hand, managers highlight that implementing this technology has a positive impact on productivity, employee satisfaction, and organizational performance (). Nevertheless, both the positive and negative aspects of remote work hold weight in shaping reward allocation and employee attitude. Managers must carefully balance these factors to ensure that the use of this technology promotes productivity and employee well-being while addressing the challenges associated with this work model ().

2.2. Influences of Remote Work and Reward Allocation

While remote work has become a globally adopted practice, much of the existing literature review focuses on North America or presents generalized global perspectives. To address this gap, we restrict the study to the European context, where unique labor laws, cultural norms, and organizational practices shape reward-allocation mechanisms ().

In this study, we identified two factors related to reward allocation, (1) salaries and (2) promotions, which can also be explained through social exchange theory. This theory suggests that incentives and collaboration improve and foster employee attitudes (), reinforcing their development and performance. Remuneration has become one of the most debatable and controversial subjects for employees () due to its pervasive and influential form of motivation directly affecting workers’ behavior and attitudes towards the company (). According to (), this factor is one of the most significant tools in human resource management, playing a crucial role in retaining top talent and employees.

During our research, we observed that salaries have a positive influence on employee attitude, and in some cases, an impact on organizational performance (). Furthermore, to maintain competitiveness, managers need to improve employee salaries to attract and retain intellectual property and a skilled workforce ().

To provide a complementary lens in this study, we incorporate equity theory (), which posits that individuals evaluate fairness by comparing their inputs (skills and effort) and outcomes (promotion and salary) to those of others (). However, in most situations, managers do not consider remote work a valid reason for salary increase. Many organizations may view remote work as a benefit, offering flexibility and reducing commuting costs, thereby offsetting the need for higher pay (). The second factor concerns promotions, which are typically driven by the need for “advancement,” accomplishment, and growth (). This action encourages change, development, and exploration of novel and creative behaviors () among future managers and employees who aspire to advance in their careers.

According to (), promotion-focused employees adopt a more flexible approach to work, demonstrating adaptability, openness to experience, and a willingness to go beyond prescribed roles to seek ideal outcomes.

However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between promotions and remote work remains unexplored. There is a persistent concern that the lack of visibility and in-person interaction with managers may negatively impact promotion opportunities ().

Moreover, the growing interest in remote work practices and flexible work arrangements has led some organizations to reevaluate their promotion criteria, focusing more on results, innovation, and adaptability, qualities often demonstrated by remote workers (). This evolving perspective suggests that remote work has a positive impact on workforce promotion, particularly in organizations that embrace digital transformation and remote work as a core part of their operational model. In this sense, as we build on our evolving understanding of reward allocation in remote work contexts, this research seeks to empirically test two critical components (salary adjustments and workforce promotions) of reward allocation within the European context, where unique cultural and organizational dynamics remain largely unexplored. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Remote work positively influences salary adjustments in SMEs.

H2.

Remote work positively influences workforce promotions in SMEs.

2.3. Remote Work and Employees’ Attitudes in SMEs

Factors underlying employee attitudes in SMEs have attracted the attention of scholars such as () and (), have identified four essential factors in their studies, namely, (1) commitment, (2) engagement, (3) job satisfaction, and (4) performance, as the most prevalent in the current organizational context.

First, employee commitment is defined as a state in which an employee identifies with a specific organization’s values and goals (), reducing the likelihood of leaving the organization (). Such a commitment is related to the intensity of employees’ sense of belonging and involvement, which has a positive impact on individual work performance ().

The relationship between remote work and commitment has been investigated by authors such as (), (), and (). According to (), remote work can serve as a personal job resource, enabling the balancing of new work demands, space reconfiguration, innovation, collaboration, and flexible working conditions ().

When employees practice RW, supervision is often absent at home (). Consequently, workers need to effectively manage their time, structure their work, and set clear goals to continue developing proficiency in some of their daily tasks (). In addition, empirical evidence has been found on the spillover effect (), referring to positive behaviors and attitudes in one area, such as work-related autonomy and job satisfaction, influencing other areas, including employee commitment and performance ().

Employee commitment improves when remote work fosters a positive relationship that does not undermine engagement, thus leading to high levels of effectiveness in remote work environments. The second factor, engagement, is described as employee persistence, cognition, and a positive state of fulfillment (). However, () reports a satisfying and favorable mental state toward work, characterized by three essential elements: dedication, absorption, and vigor. The curiosity surrounding this phenomenon has led researchers to study it and deepen their understanding of commitment. As a result, () concluded that when employees are engaged, they tend to be highly self-efficacious, energetic, and more committed.

Additionally, when employees are engaged, they contribute positively to their organization by retaining and attracting support from coworkers and new customers (). Therefore, increasing employee engagement is crucial (; ), especially in a remote work setting. Furthermore, organizations that adopt this technology demonstrate greater agility and resilience, turning remote work into a strategic capability. This complement connects to dynamic capabilities theory (), which can be seen as a core mechanism for reconstructing and integrating internal and external resources in response to environmental changes ().

In addition, from a human perspective, employees who receive resources and benefits from the organization and their managers tend to be more motivated and engaged in the workplace (). However, () noted that one of their concerns with a shift to remote work is how worker engagement may be affected by stress.

Others, such as () and (), discuss the lack of supervision and control. Finally, () address the significant decline in internal organizational communication, which could lead to lower emotional investment. Given the possibility of a remote work setting and the constraints it entails, the key is to increase an employee’s engagement in the organization, creating conditions () that foster a better work environment and job satisfaction centered on their needs.

The third factor is job satisfaction, a key element and one of the most crucial factors in the organization’s progress (). Defined by () and (), job satisfaction is an employee’s positive feelings about their work position. () discuss job satisfaction as a positive attitude and a set of emotions that people have towards their jobs. However, the author emphasized the importance of employees who do not feel diminished, as they may otherwise quit.

According to (), several factors influence job satisfaction, which can be generally categorized at both individual and organizational levels. Personal factors that affect job satisfaction include age, gender, marital status, personality traits, education, and the socio-cultural environment (). On the other hand, institutional factors encompass working conditions within the organizational environment, management systems, salaries, relationships with managers, development opportunities, workplace communication, and opportunities for improvement ().

These factors are related to motivation theory, which posits that organizational factors are linked to job satisfaction (). It is also considered a valuable factor (job association) in the development and maintenance of an adequate level of satisfaction (). In the context of remote work, employees must address their concerns to perform their jobs effectively and achieve job satisfaction. Some of these hesitations include sharing personal information with their managers, interacting with every member of the organization, attending work-related meetings, and overcoming work isolation ().

Employee performance in the workplace is determined by the overall organization’s efficiency and productivity (). As previously stated, remote work allows employees to perform their tasks from locations outside the office ().

Based on the literature, the hypotheses are as follows:

H3.

Salary adjustments have a positive effect on employee attitudes.

H4.

Workforce promotions have a positive effect on employee attitudes in SMEs.

H5.

Remote work has a positive effect on employees’ attitudes.

H6.

Reward allocation mediates the relationship between remote work and employees’ attitudes.

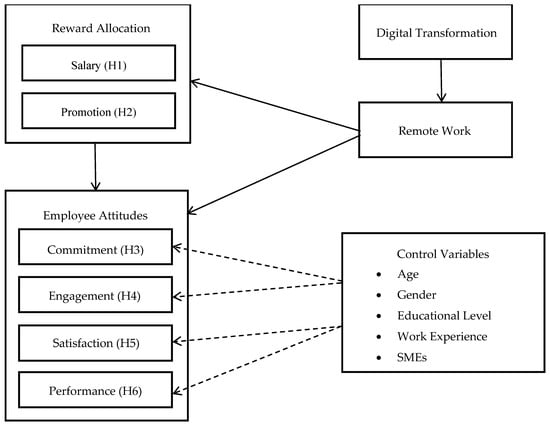

Based on the above hypothesis, it was determined that remote work affects salary adjustments and promotions, which in turn have a direct or indirect impact on commitment, engagement, job satisfaction, and performance. In that sense, the following conceptual model (Figure 1) was determined as follows:

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire and Measurements

Based on our research model, a structured questionnaire was developed to collect data from the European participants. The questionnaire has two main parts. The first comprised the characteristics of the respondents, including gender, age, education, country, industry, department, work experience, industry type, and company size. Section 2 includes the measurement of reward allocation (linked to SA and WFP), employee attitudes (linked to COM, ENG, JS, and WP), and remote work.

The reason for our choice for the items describing the reviewed constructs was based on previous studies: remote work (15 items; ), commitment (10 items; ; ; ), engagement (10 items; ; ), job satisfaction (5 items; ; ; ), salary adjustment (7items; (; ), workforce promotion (7 items; ; ), and performance (7 items; ; ). All items in this study were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7= strongly agree”).

(), (), and () recommended this scale, which is more accurate than a 5-point Likert scale. In addition, to create a more precise questionnaire with relevant information, the survey was sent to five professors specialized in management. The experts reviewed the content by providing feedback that led to improvements in the questionnaire before it was sent to the participants.

3.2. Scale Measurement

3.2.1. Reward Allocation

Reward allocation was measured using a scale adapted from previous studies on organizational rewards (; ; ; ). This measure includes two variables (salary adjustments and workforce promotions) that are distributed based on organizational performance. Salary adjustments were measured with items such as “I believe that salary adjustments are fairly distributed based on performance in the organization,” and workforce promotion was measured with items like “I believe that promotions in my organization are merit-based and equitable.”

3.2.2. Employee Attitudes in SMEs

Employee attitudes were measured using a combination of established scales. This variable includes dimensions such as commitment, engagement, job satisfaction, and performance. Commitment was measured in items like “I am loyal to my organization.” Engagement was measured using items such as “I feel enthusiastic about my work” and “I am fully absorbed in my task when working remotely.” Job satisfaction included items such as “I am satisfied with my current job responsibilities,” and performance included items like “I am willing to put in extra effort for the company’s success.”

3.2.3. Control Variables

Our study also considered control variables that could affect our results, namely, age, gender, education level, and work experience. For age measurement, we adopted the following categories. Age is considered a critical variable, as it can influence employee attitudes and career progression. Younger employees may have different perspectives, expectations, and adaptability to remote work than older employees do. Considering the number of positions in an organization, we used the gender variable to account for potential disparities in salary adjustments and promotions.

To measure work experience, we considered the following ranges: less than 5 years, 5–10 years, and more than 10 years. This variable may consider the levels of competence and job autonomy, which affect workers’ ability to work remotely and influence their likelihood of receiving promotions and salary adjustments. An academic degree determined whether the employee held a Ph.D., master’s, bachelor’s degree, secondary education, or basic education. These variables are correlated with job role, skill level, and career trajectory. Employees with higher expectations for promotions and salaries have positioned themselves to benefit from remote work arrangements. SMEs will be measured across three levels: early adopters, scaling adopters, and digitally mature companies. This variable (SMEs) reflects the organization’s capacity to integrate digital technologies, adapt to changing business models, and leverage remote work to enhance competitiveness and growth.

3.3. Sampling and Data Gathering

As previously mentioned, our study focuses on evidence from the European population, as this context provides a unique lens for examining the impacts of remote work on reward allocation and employee attitudes. The choice of the target population was driven by the exponential rise in organizations adopting remote work () as a valuable option, despite its widespread use during the COVID-19 pandemic. The online questionnaire used was Google Forms and was distributed from January to May of 2025. Initially, 800 invitations were screened, but only 615 responses were validated.

Due to the population’s location, a purposive sampling technique will be employed in this study to select participants who meet specific criteria, such as remote workers in various industries across the European continent, thereby ensuring the sample is relevant to the research objectives. This study employed an online survey to collect answers from the participants, which was anonymous and voluntary. Invitations were sent via LinkedIn, WhatsApp, email (), and other social media platforms due to the nature of this study. Participation represented a multitude of sectors, helping to provide a diversified perspective on remote work dynamics within SMEs.

However, only 615 responses were validated, mainly from Poland (25.37%), Portugal (28.29%), and the United Kingdom (19.51%). Table 1 presents the demographic profile showing that 63.41% of all respondents were male and 36.59% were female.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile.

Regarding ages, 32.2% were between the ages of 18 and 25 years old, 42.44% between ages 26 and 35 years old, 14.63% were 36–45 years old, 6.83% were 46–55 years old, 2.44% were 56–65 years old, and finally 1.46% were > 65 years old.

The countries with higher rates are Poland, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, while those with a lower rate include Spain, Greece, Belgium, Germany, France, Ireland, Finland, Lithuania, and the Netherlands. Participants were primarily employed in the technology (33.17%) and education (11.22%) industries, which have higher rates of remote work. Most participants were in the sales department (11.22%). Regarding the level of education, the participants with higher rates were bachelor’s degree with 35.61%, master’s degree with 32.2%, and secondary education with 24.39%.

Regarding work experience, 46.34% had worked in the organization for less than five years, 27.8% for 5–10 years, and 25.85% for more than ten years. Regarding institution type, 69.76% were from the private sector, 24.88% from the public, and 5.37% from a non-profit organization. In addition, 62.44% of the participants worked in SMEs and 37.56% worked in large corporations.

3.4. Data Analysis

Considering the nature of the causal relationships among the latent variables, we employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with WarpPLS 7.0 software package (). This software is particularly suitable for this study because of its ability to model complex relationships between multiple latent variables, including remote work, reward allocation (e.g., salary adjustments, workforce promotion), employee attitude (e.g., engagement, commitment, job satisfaction, and performance), and control variables (age, gender, education level, work experience, and SMEs). Given the exploratory nature of the study and its focus on theory development rather than strict theory confirmation, this software provides an appropriate methodological framework.

Moreover, the sample size of n = 615 aligns with the robustness of PLS-SEM (; ) in handling limited datasets, as opposed to covariance-based SEM, which often requires a large sample. In addition, it accommodates non-normal data distributions and enables the simultaneous evaluation of measurement and structural models, ensuring both construct validity and model predictive power. Previous research on remote work has demonstrated the utility of PLS-SEM in analyzing complex frameworks involving attitudinal outcomes, further supporting its application in this context (; ).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Testing

Several steps were implemented to test the measurement (outer) model. First, to establish the reliability indicator, the outer loadings of each latent variable should have a cut-off point of at least 0.60. In this sense, we excluded every load that scored less than 0.60 (i.e., RW7, COM5, SA2, SA8, WFP3, WFP5, WFP8, and JS3).

As shown in Table 2, the composite reliability (CR) values exceeded 0.7, indicating the good internal consistency of the constructs. The average variance extracted (AVE) values are above 0.5, indicating that the constructs capture more than half of the variance in their indicators, a strong sign of convergent validity (). These results demonstrate that the model meets the requirements of construct reliability and validity. The AVE values exceeded 0.5, namely commitment (0.502), job satisfaction (0.606), JS (0.532), and performance (0.607). However, some constructs, namely remote work, salary adjustments, workforce promotion, and engagement, presented AVE slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.5. These values do not compromise convergent validity due to Cronbach’s alpha and CR, for which all constructs exceeded the value of 0.70. (). Although AVE is a conservative criterion, a value below 0.50 may be acceptable when reliability is high (). The lower values of AVE are a consequence of a large number of indicators and moderate loading with some items. A re-analysis was performed by removing the lowest-loading items, which improved the AVE value without compromising reliability. Therefore, all the constructs were retained to preserve theoretical comprehensiveness and comparability with prior studies. Additionally, discriminant values were confirmed through the HTMT ratio, which remained below the recommended threshold, supporting the robustness of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Measurement model assessment.

Regarding discrimination validity, the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) approach was considered superior to ’s () approach. Table 3 shows that the HTMT values for the latent variables were below 0.90, except for ’s (), but with significance lower than 1.0.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity—HTMT ratio.

Furthermore, discriminant validity was established. In addition, in relation to the goodness-of-fit indices shown in Table 4, the fit indices of APC, ARS, AFVIF, AARS, GoF, SPR, RSCR, SSR, and NLBCDR were acceptable and adequate ().

Table 4.

Model fit and quality indices.

4.2. Structural and Model Assessing

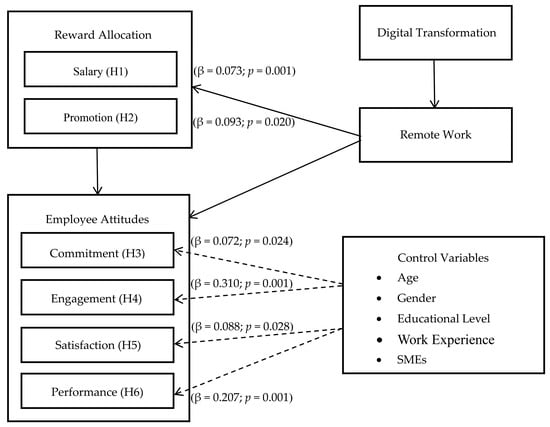

To understand the causal relationships between the latent variables investigated, the structural model was determined based on the following measures: path coefficients and their significance (p-value), R2, Q2, and size (f2). Figure 2 shows a representation of the structural model based on these results.

Figure 2.

Results of the inner model.

According to them, remote work had a positive and significant impact on salary adjustment (β = 0.073, p < 0.001), workforce promotion (β = 0.093, p < 0.020), commitment (β = 0.072, p < 0.024), engagement (β = 0.310, p < 0.001), job satisfaction (β = 0.088, p < 0.028), and performance (β = 0.207, p < 0.001).

As a result, all hypotheses were supported based on the values provided (R2) of the endogenous constructs. Remote work has a value of 0.591%, indicating a moderate level of explanatory power.

In the analysis, effect sizes (f2) were evaluated using guidelines, where values between 0.02 and 0.15 indicate a low effect size, values between 0.15 and 0.35 indicate a medium effect size, and values greater than 0.35 represent a large effect size.

Based on this analysis, we calculated the effect size (f2) for the path coefficients. According to (), the f2 values are as follows: The paths from RW to SA, WFP, and COM showed a low effect size, with f2 values of 0.009 and 0.005, respectively. These results indicate that remote work substantially affects both salary adjustment, workforce promotion, and commitment. Remote work and engagement had a small to medium effect size (f2 = 0.115). The RW and JS path of f2 = 0.025 represents a small effect size, influencing modest engagement. Similarly, the relationship between remote work and WP (f2 = 0.047) also exhibited a small effect size. The results in Table 5 show that low to medium effect sizes were found among all links between the latent variables. Subsequently, we assessed the Q2 values. The values of this measure should exceed zero to be considered medium, ≥0.25 meaningful, and ≥0.50 large. The values obtained are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Structural model and hypothesis testing.

Moreover, in Table 6, we conducted a multi-group analysis (MGA) to compare the impact of remote work across the six hypotheses related to reward allocation and employee attitudes. The findings of the MGA (Table 6) indicate no significant differences in the p-value or path coefficients between the two groups, meaning that there are no substantial differences in the influence of remote work on either variable.

Table 6.

Multi-group analysis (MGA).

Figure 2 illustrates the structural model results regarding reward allocation and employee attitudes, highlighting the indirect effects of the control variables.

5. Discussion

The current study aims to investigate the influence of remote work (RW) on organizational behavior, specifically its impact on reward allocation (salary and promotion) and employees’ attitudes (engagement, satisfaction, commitment, performance), while addressing the challenges of aligning HR and digital transformation.

To address this, a quantitative method was employed, using a survey to collect data from a sample of remote workers on the European continent. PLS-SEM software was used to analyze the collected data and test the hypotheses. The empirical data supported the proposed hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, and H6), indicating that remote work has significant and positive effects on work-related variables (i.e., SA, WFP, COM, ENG, JS, and WP) within the context of organizational behavior.

Through this study, it became clear that remote work is enabled by digital technologies (; ), which allow SMEs to reduce overhead costs, offer greater employee flexibility, and implement new reward systems.

In this context, it is possible to understand that there was an emphasis on productivity, efficiency, and fairness in salary and promotion decisions, reflecting how digital transformation supports outcome-based evaluation that moves beyond traditional physical presence ().

The results indicate that reward allocation focuses on exploring salary adjustments and workforce promotions within the context of remote work. Consistent with prior findings (), salary remains a persistent concern for remote employees. To increase sustainability in this format, participants considered the need to provide greater flexibility, an efficient work environment, recognition of workplace challenges, and performance improvement as factors for increased remuneration. Moreover, there is a shared belief that salary adjustments should be performance-driven rather than based on physical presence, and organizations should account for the cost savings experienced by remote workers when evaluating compensation.

Regarding promotion opportunities, this remains an essential concern for remote employees. Participants highlighted that work in a remote setting should not hinder career progression; instead, it should provide equal opportunities, continually enhancing their visibility within the organization and the recognition of their contributions, regardless of physical presence. The encountered data is supported by (), who discusses a newer approach to work being more flexible, adapted to employees’ needs, and open to new experiences. In hindsight, there is a shared belief that promotion prospects should be determined by factors such as value creation and performance, rather than the location where they were encountered.

Concerning employee attitudes, the data showed that engagement, satisfaction, and performance were the most relevant factors. Engagement in the organizational spectrum is viewed as associated with employee persistence, cognition, and a positive state of fulfillment (). However, (). Through this dimension, the higher the engagement, the greater the impact on the worker, which reflects the ability to retain and attract new customers.

Despite the physical distance, most of our participants felt more connected to the organization, which aligns with social exchange theory () and supports the development of a better work environment centered on their needs (). This work format enhances employees’ sense of responsibility for daily tasks and encourages them to exert greater effort to achieve their work goals.

Additionally, engagement alone may not fully address concerns about the lack of supervision and control (; ), but it can mitigate some issues by increasing accountability and teamwork. Through our research, we found that remote work has a positive impact on job satisfaction thanks to the benefits it offers. According to () and (), job satisfaction refers to how employees feel about their work. When correlating this definition with remote work, we observed that employees were more satisfied when working from home, having a positive impact on overall satisfaction. Remote work allows employees to maintain a healthier balance between their personal and professional lives, increasing job satisfaction, and it is considered beneficial for reducing the likelihood of quitting.

Contrary to () and (), we discussed stress-related issues. Our research indicates that remote work enhances employees’ ability to manage stress, leading to increased feelings of fulfillment. The participants recognized that their organizations created a work environment that enhanced job satisfaction and that their concerns were taken into account. Moreover, managers need to consider that employees may hesitate to share personal information, lack interaction with team members, and feel isolated at work ().

Furthermore, our results indicate that remote work has a positive influence on worker performance. Employee performance in the workplace is determined by the organization’s overall efficiency and productivity (). Our research demonstrates that RW improves workers’ overall performance by developing a stronger alignment with digital tools, achieving better outcomes within the organization, and improving reward mechanisms. The purpose of these actions is to divert the focus from physical presence to value creation. Moreover, there is an indication that age significantly moderates the relationship between variables like remote work and employee attitudes, whereas gender does not. The difference between these two is attributed to generational variations in digital literacy and fluency, work–life expectations, and career stage. Participants between the ages of 26 and 35 years old often perceive remote work as an opportunity to develop autonomy, flexibility, and professional growth, whereas older employees may associate it with challenges related to social interaction and adapting to digital workflows.

Although () considered remote work a benefit, it enables employees to deliver high-quality work when the right tools and environment are provided, allowing them to manage their time more effectively and complete their tasks and projects more efficiently. Even though these requisites have been met, employees still expect equitable compensation in remote work settings ().

These findings support and align with social exchange theory, which holds that salaries and promotions act as key signals of fairness. Rewards in remote contexts are based on outcomes rather than visibility, and the perceptions of equity increase, leading to motivation and satisfaction. Regarding dynamic capabilities theory, the study shows how SMEs leverage digital transformations in the reconfiguration of HR and reward systems with the ability to build adaptive and fair management practices.

6. Conclusions

Through the findings, it becomes apparent that digital transformation enables remote work by providing technological conditions for flexible work arrangements, which, in turn, influence how rewards are allocated and how workers respond to those practices. Salary adjustments and promotion opportunities are increasingly measured by the outcomes produced by the workers rather than physical presence, demonstrating a shift towards human resources practices and performance. Mechanisms like commitment, engagement, satisfaction, and performance support the principles of social exchange and equity theories, where fairness and reciprocity become a strong foundation for organizational relationships. However, remote work is seen as a tool that can enhance worker motivation, autonomy, and better alignment with the organizational goals. Factors such as engagement, job satisfaction, and performance have positive relationships with remote work, indicating that the more flexible the environment, the higher the ability to boost employee morale, dedication, and productivity.

These effects align with social exchange theory, showing that fairness perceptions and reciprocal exchanges remain central even when organizational interactions are virtual. In addition, the inclusion of control variables such as gender, education level, work experience, and SMEs status highlights that the level of competencies acquired, knowledge, and demographic factors play a role in understanding and shaping the guidelines for remote work. Conversely, age did not have a significant effect. Thus, SMEs undergo digital transformation, rely on digital literacy, adaptability, and accumulate expertise to implement better processes to improve performance. Demographic differences highlight the individual differences between employees but underscore the importance of human capital in enabling SMEs to leverage digital transformation for remote work practices and organizational competitiveness.

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical advancement of organizational behavior by empirically validating how remote work becomes a key influence on employee outcomes through the lens of reward allocation. First, this research broadens the understanding of how digital transformation is reshaping human resources practices, showing that salaries and promotions act as mechanisms linking remote work to employee attitudes. Second, traditional theories are often linked to reward allocation and face-to-face interactions. The findings suggest that, in remote work contexts, the mechanisms should focus on performance-based, meritocratic approaches, signaling a conceptual realignment in career progression. Third, according to Social Exchange Theory and Equity Theory, the findings underscore that remote work environments promote stronger engagement, satisfaction, and performance when employees perceive fairness in reward mechanisms, such as salary adjustments.

Furthermore, this study extends the existing theory by highlighting the diminished role of traditional promotion pathways in remote work contexts, where visibility is reduced and output-based assessment becomes more relevant. This action suggests a theoretical shift in how organizations conceptualize digital work settings, emphasizing meritocratic, performance-oriented metrics over face-to-face paradigms.

This research contributes to the discourse on how organizations may need to reconsider promotion criteria in the context of remote work. Visibility and proximity to managers are no longer considered direct factors in determining job satisfaction. Also, this research supports the notion that organizations should shift towards a result-oriented promotion system that emphasizes innovation and adaptability, particularly for remote workers.

7.2. Practical Implications

The practical implications provide actionable insights for policymakers and managers. With that in mind, this study has four implications. First, organizations should consider adjusting their compensation models to reflect the increase in productivity, performance, and flexibility associated with remote work, rather than relying on visibility or physical presence.

Second, the limited influence of remote work on promotion policies must be restructured to focus on measurable outcomes, creativity, and adaptability. Managers should develop new pathways that do not disadvantage remote employees due to their limited exposure. Third, strategies should address the specific needs of remote workers, such as providing the right tools and maintaining clear communication channels. This process includes adopting digital performance tracking tools, structured feedback systems, and skill-based career ladders.

Lastly, practical outcomes highlight the need for SMEs to invest in both digital literacy and infrastructure, as well as performance tools and the development of feedback systems, allowing systems to evolve fairly in remote work environments, while maintaining motivation and accountability.

8. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. One potential limitation is the self-reported nature of the data, which may have introduced social bias, leading participants to exaggerate their job satisfaction or commitment levels. To minimize this effect, the employment of a social desirability control scale (e.g., Marlowe—Crowne Social Desirability Scale) () would help to reduce that bias. In this regard, we attempted to ask some questions while developing the questionnaire to avoid incorrect answers and eliminate bias. Therefore, in recognition of this limitation, and as a future step, we propose an experimental study involving multiple respondents to facilitate one-on-one conversations and further refine our findings. Finally, we realize that adding control variables considerably increases the size effect (f2).

In the realm of future research, remote work continues to hold great potential not only to transform the way organizations conduct business but also to be a factor in ensuring competitive advantage. Therefore, it is essential to continue exploring remote work. To be more supportive of employees, increase efficiency, and improve work–life balance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.G.; methodology, D.M.G.; software, D.P.R.; validation, A.G.; investigation, A.G., D.P.R., D.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.G.; writing—review and editing, D.M.G.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, D.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external fund and the APC was funded by CINAMIL/Academia Militar, grant number [430556149/process number 4025030784].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the study was conducted independently and did not involve institutional resources, it does not fall under the university’s ethics review process. The study involved an anonymous online survey, with no collection of sensitive personal data, and therefore qualifies as exempt from formal ethical approval according to standard international ethical research principles.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jorge Simões for his insights regarding the topic and Manuel do Carmo, who is always available to help and contribute greatly to our learning in the field of statistics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RW | Remote Work |

| JS | Job Satisfaction |

| WFP | Workforce Promotion |

| WP | Worker Performance |

| SA | Salary Adjustments |

| SMES | Small and Medium Enterprises |

References

- Adamovic, M., Gahan, P., Olsen, J., Gulyas, A., Shallcross, D., & Mendoza, A. (2022). Exploring the adoption of virtual work: The role of virtual work self-efficacy and virtual work climate. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(17), 3492–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S. (2024). Impact of dimensions of organisational culture on employee satisfaction and performance level in select organisations. IIMB Management Review, 36, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R., Unnava, H. R., & Burnkrant, R. E. (2001). The moderating role of commitment on the spillover effect of marketing communications. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(4), 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, T., Uddin, M. S., Rahman, R., Uddin, M. S., Islam, M. R., Faisal-E-Alam, M., & Rahman, M. M. (2024). The moderating effect of system quality on the relationship between customer satisfaction and purchase intention: PLS-SEM & fsQCA approaches. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifuddin, N. A., & Ibrahim, D. (2021). Studies on the impact of work from home during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review. Jurnal Komunikasi Borneo (JKoB), 9, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (2000). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabei, S. D., Labrague, L. J., Miner Ross, A., Karkada, S., Albashayreh, A., Al Masroori, F., & Al Hashmi, N. (2020). Nursing work environment, turnover intention, job burnout, and quality of care: The moderating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 52, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshibly, H., & Alzubi, K. N. (2022). Unlock the black box of remote e-working effectiveness and e-HRM practices effect on organizational commitment. Cogent Business & Management 9, 2153546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuna, O. K., & Arslan, F. (2016). Impact of the number of scale points on data characteristics and respondents’ evaluations: An experimental design approach using 5-point and 7-point likert-type scales. International Journal of Market Research, (55), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelici, M., & Profeta, P. (2023). Smart working: Work flexibility without constraints. Management Science 70, 1343–2022. [Google Scholar]

- Astorquiza-Bustos, B., & Quintero-Peña, J. (2023). Who can work from home? A remote working index for an emerging economy. Telecommunications Policy, 47(10), 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, G., & Priyanka, S. (2023). Conceptual framework on successful implementation of hybrid work model for virtual IT employees. International Journal of Engineering Technologies and Management Research, 10(4), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehner, C. G., & Blackwell, M. J. (2016). The impact of workplace spirituality on food service worker turnover intention. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 13(4), 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusan, R. M. B. (2024). The spectre of generative AI over advertising, marketing, and branding. Journal of Future Media Studies, 1(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brenninkmeijer, V., & Hekkert-Koning, M. (2015). The relationships between regulatory focus, job crafting and work outcomes. Career Development International, 20(2), 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V., Schettino, G., Marino, L., Camerlingo, C., Smith, A., & Depolo, M. (2024). The new normal of remote work: Exploring individual and organizational factors affecting work-related outcomes and well-being in academia. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1340094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J., Parida, V., & Wincent, J. (2019). How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. Journal of Business Research, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., & Michailidis, E. (2018). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., & Vrontis, D. (2022). Does remote work flexibility enhance organization performance? Moderating role of organization policy and top management support. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgnet, B., Martin, L., Ndodjang, P., & Sutan, A. (2019). On the merit of equal pay: Performance manipulation and incentive setting. European Economic Review, 113, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, F., & Doran, J. (2020). COVID-19, occupational social distancing and remote working potential: An occupation, sector, and regional perspective. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 12(6), 1211–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, O., & Yıldırım, S. (2010). Job satisfaction in nurses and effective factors: Review. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Nursing Sciences, 2(1), 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Daouda, O. S., Hocine, M. N., & Temime, L. (2021). Determinants of healthcare worker turnover in intensive care units: A micro-macro multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE, 16(5), e0251779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. International Journal of Market Research, 50, 104–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N. E. (2011). Perceived pay communication, justice, and pay satisfaction. Employee Relations, 33(5), 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoeije, J., & Verbruggen, M. (2020). Between-person and within-person effects of telework: A quasi-field experiment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(6), 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. (2021). 5/7-point Likert scales aren’t always the best option: Their validity is undermined by lack of reliability, response style bias, long completion times and limitations to permissible statistical procedures. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R., & Johns, J. (2020). Recontextualizing remote working and its HRM in the digital economy: An integrated framework for theory and practice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(1), 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, R., Daellenbach, U., & Donnelly, N. (2024). Pastoral control in remote work. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 40(4), 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Habuer, & Fujiwara, T. (2024). Optimizing cell phone recycling process: Unraveling rational and emotional drivers of consumer recycling participation using PLS-SEM and fs-QCA. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 191, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54(2), 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandrita, A., Bastos, B., Gandrita, D. M., & Costa, D. (2022). Digitalization through pandemic crisis: Effects on technology, processes & human capital. Journal of Management and Business: Research and Practice, 14(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandrita, D. M. (2024). Technology and family business: From conceptualization to implementation in strategic planning—A perspective article. Journal of Family Business Management, 14(2), 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandrita, D. M., Gandrita, A., & Rosado, D. P. (2025a). Challenges and strategies of gamification in family businesses: The moderating effects of supervision and engagement. European Business Review, 37(3), 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandrita, D. M., Rosado, D. P., & Gandrita, A. (2025b). AI integration and strategic planning: Fostering inclusivity and strategic evolution in the workplace. Thunderbird International Business Review, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellis, Z. D. (2001). Job stress among academic health center and community hospital social workers. Administration in Social Work, 25(3), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genquiang, L., Yueying, T., Yong, M., & Min, L. (2024). Change or paradox: The double-edged sword effect of organizational crisis on employee behavior. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(2), 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M. R., Santoro, P. E., Borrelli, I., Rossi, M. F., Amantea, C., Daniele, A., & Moscato, A. (2023). TElewoRk-RelAted stress (TERRA), psychological and physical strain of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review Workplace. Health Safety, 71(2), 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günday, F., Taş, A., Abacıgil, F., & Arslantaş, H. (2022). Factors affecting job satisfaction and quality of work life in nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Adnan Menderes University Health Science Faculty, 6(2), 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J., & He, F. (2025). Acquisition of financial resources, dynamic capabilities, and embedding in corporate ecosystem platforms. Finance Research Letters, 86, 108451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoey, S., Peeters, T., & van Ours, J. C. (2023). The impact of absent co-workers on productivity in teams. Labour Economics, 83, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Iun, J., Liu, A., & Gong, Y. (2010). Does participative leadership enhance work performance by inducing empowerment or trust? The differential effects on managerial and non-managerial subordinates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iogansen, X., Malik, J. K., Lee, Y., & Circella, G. (2024). Change in work arrangement during the COVID-19 pandemic: A large shift to remote and hybrid work. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 25, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K., Yamamoto, I., & Nakayama, M. (2023). Potential benefits and determinants of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Japanese Household Panel Data. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 70, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A. W. (2025). How and when incentives and collaboration are effective in fostering supplier component innovation: Insights from social exchange theory. Journal of Business Research, 189, 115131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, U., Schnurr, B., Fuchs, C., Schreier, M., & van Osselaer, S. M. J. (2025). Signatures and de-objectification: How asking individual producers to sign their work increases work performance and work satisfaction. International Journal of Research in Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerman, K., Korunka, C., & Tement, S. (2022). Work and home boundary violations during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of segmentation preferences and unfinished tasks. Applied Psychology, 71(3), 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. S., & Jang, S. C. (2020). The effect of increasing employee compensation on firm performance: Evidence from the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, K., Ipsen, C., & Hansen, J. P. (2021). COVID-19 leadership challenges in knowledge work. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 9(4), 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2020). WarpPLS user manual: Version 7.0. ScriptWarp Systems. Available online: http://www.scriptwarp.com/warppls/UserManual_v_7_0.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Kortsch, T., Rehwaldt, R., Schwake, M. E., & Licari, C. (2022). Does remote work make people happy? Effects of flexibilization of work location and working hours on happiness at work and affective commitment in the German banking sector. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 159117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E. E., Ruderman, M. N., Braddy, P. W., & Hannum, K. M. (2012). Work–nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtaliqi, F., Miltgen, C. L., Viglia, G., & Pantin-Sohier, G. (2024). Using advanced mixed methods approaches: Combining PLS-SEM and qualitative studies. Journal of Business Research, 172, 114464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C. E., Arbuckle, S. A., & Holden, R. R. (2016). The Marlowe–Crowne social desirability scale outperforms the BIDR impression management scale for identifying fakers. Journal of Research in Personality, 61, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Roloff, M. E. (2008). ‘Organizational culture and compensation systems: An examination of job applicants’ attraction to organizations’. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 15(3), 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M. (2020). An equity theory perspective of online group buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., & Niu, Y. (2022). Do companies compare employees’ salaries? Evidence from state-owned enterprise groups. China Journal of Accounting Research, 15(3), 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, M., & Martin, D. (2019). Executive compensation and employee remuneration: The flexible principles of justice in pay. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino-Romero, J. A., Palos-Sanchez, P. R., & Velicia-Martín, F. (2024). Evolution of digital transformation in SMEs management through a bibliometric analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 199, 123014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety, availability, and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 7(1), 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Manuti, A., Giancaspro, M. L., Russo, V., Zito, M., & Cortese, C. G. (2020). Wellbeing costs of technology use during COVID-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability, 12(15), 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2008). Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P. M., Lit, K. K., & Cheung, C. T. (2022). Remote work as a new normal? The technology-organization-environment (TOE) context. Technology in Society, 70, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, C. J., & Chimereze, C. (2020). Brain drain among Nigerian nurses: Implications to the migrating nurse and the home country. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation (IJRSI), 7(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Okawara, M., Hirashima, K., Igarashi, Y., Mafune, K., Muramatsu, K., Nagata, T., & Ishimaru, T. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 infection on work functioning in Japanese workers: A prospective cohort study. Safety and Health at Work, 4(14), 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okojie, G., Alam, A. S. A. F., Begum, H., Ismail, I. R., & Sadik-Zada, E. R. (2024). Social support as a mediator between selected trait engagement and employee engagement. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 10, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, L., Veglianti, E., Zardini, A., & Rossignoli, C. (2024). Enhancing employees’ remote work experience: Exploring the role of organizational job resource. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 199, 123075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, L., & Jena, L. K. (2020). Mindfulness, remote engagement and employee morale: Conceptual analysis to address the “new normal”. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S. J., Rubino, C., & Hunter, E. M. (2018). Stress in remote work: Two studies testing the demand-control-person model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(5), 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. T. L., Liao, G.-Y., Shih, S.-P., Cheng, T. C. E., & Teng, C.-I. (2024). How gaming team participation fosters consumers’ social networks, communication, and commitment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 81, 103962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, P., & Saha, H. (2024). Mediating effects of occupational self-efficacy on the relationship of authentic leadership and job engagement. Business Analyst Journal, 45(1), 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S. I. (2006). Amin Rajan: Promotion of workforce diversity. Human Resource Management International Digest, 14(3), 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, G. L. (2016). Job satisfaction and turnover intent among hospital social workers in the United States. Social Work in Health Care, 55(7), 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saks, A. M. (2021). Caring human resources management and employee engagement. Human Resource Management Review, 32, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Martínez, I. M., Marques Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002a). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., & González-Romá, V. (2002b). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two-sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, L. J., & Thaler, J. (2024). Strategic communication in organizational change: Exploring the impact of two-sided messages on legitimacy judgments and commitment to change. European Management Journal, 43, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenberg, D., Benitez, J., Klos, C., Velamuri, V. K., & Spieth, P. (2021). Value creation and appropriation of software vendors: A digital innovation model for cloud computing. Information & Management, 58(4), 103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdaifat, E., Shudayfat, T., Al-Shdayfat, N., & Alshowkan, A. (2023). Understanding the mediating effects of commitment and performance on the relationship between job satisfaction and engagement among nurses. The Open Nursing Journal, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M. K. (2017). Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A. E., Ibrahim, Y., & Gabry, G. (2019). Unlocking the black box: Psychological contract fulfillment as a mediator between HRM practices and job performance. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M., Di Virgilio, F., Figueiredo, R., & Sousa, M. J. (2021). The impact of workplace spirituality on lecturers’ attitudes in tourism and hospitality higher education institutions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Mandolakani, F., & Singleton, P. A. (2024). Electric vehicle charging infrastructure deployment: A discussion of equity and justice theories and accessibility measurement. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 24, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, J., & Kammerlander, N. (2021). Digital transformation in family-owned Mittelstand firms: A dynamic capabilities perspective. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(6), 676–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, C. (2005). Adjusting teacher salaries for the cost of living: The effect on salary comparisons and policy conclusions. Economics of Education Review, 24(3), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboroši, S., Strukan, E., Poštin, J., Konjikušić, M., & Nikolić, M. (2020). Organizational commitment and trust at work by remote employees. Journal of Engineering Management, 10, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahlyan, D., Mahmassani, H., Stathopoulos, A., Said, M., Shaheen, S., Walker, J., & Johnson, B. (2024). In-person, hybrid or remote? Employers’ perspectives on the future of work post-pandemic. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 190, 104273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenaw, Z., Siyoum, M., Tsegaye, B., Werba, T. B., & Bitew, Z. W. (2021). Health professionals job satisfaction and associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, S., Rozin, D. R., Pitesa, M., Mitchell, M. S., & Pillutla, M. M. (2015). Unethical for the sake of the group: Risk of social exclusion and unethical pro-group behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, T., & Sarti, D. (2019). Themes and trends in smart working research: A systematic analysis of academic contributions HRM 4.0 for Human-centered Organizations. Advances Series in Management, 23, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero-Sánchez, R., Peña-Vinces, J., & Matos Ferreira, J. J. (2022). The effect of collectivism-based organisational culture on employee commitment in public organisations. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 83, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayasuriyan, G., & Balaji, K. (2023). Remote working—A boon or bane with regards to employee’s performance and job satisfaction. Journal of Propulsion Technology, 44(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaithilingam, S., Ong, C. S., Moisescu, O. I., & Nair, M. S. (2024). Robustness checks in PLS-SEM: A review of recent practices and recommendations for future applications in business research. Journal of Business Research, 173, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Song, Y., & Jiang, F. (2024). Are they more proactive or less engaged? Understanding employees’ career proactivity after promotion failure through an attribution lens. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 155, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., & Dhar, R. L. (2021). Linking frontline hotel employees’ job crafting to service recovery performance: The roles of harmonious passion, promotion focus, hotel work experience, and gender. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Sinha, S., Weston, J., Joyce, C., Shah, N., Sherman, K., Hecht, B., & Teevan, J. (2022). The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nature Human Behavior, 6(1), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J. J., Zhao, X., Park, K., & Shi, L. (2020). Sustainability condition of open innovation: Dynamic growth of Alibaba from SME to large enterprise. Sustainability, 12(11), 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xu, W., Yoon, S., Chen, W., & Parmenter, S. (2024). Workplace support, job autonomy, and turnover intention among child welfare workers in China: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Child Protection and Practice, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L., Wayne, S. J., & Liden, R. C. (2016). Job engagement perceived organizational support, high-performance human resource practices, and cultural value orientations: A cross-level investigation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(6), 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).