Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly positioned as an enabler of strategic renewal and competitiveness for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in emerging economies. However, its adoption remains limited and uneven, constrained by shortages of skilled talent, weak data infrastructures, and financial barriers. This study examines Ecuadorian SMEs as a representative case within this broader context, analyzing survey data from 385 firms to diagnose AI adoption patterns and validate a structural model linking AI adoption, dynamic capabilities, and strategic innovation performance. Results from Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) confirm that AI adoption enhances innovation and competitiveness both directly and indirectly through dynamic capabilities, specifically firms’ abilities to sense opportunities, seize them through innovation, and reconfigure resources. The model explains 41% of the variance in strategic innovation performance, providing robust empirical support for the proposed AI-Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness. The study clarifies how perceptual and contextual enablers of adoption (TAM/TOE) interact with capability-building mechanisms (RBV/DCT), offering a more integrated understanding of how SMEs assimilate AI under resource constraints. These findings demonstrate how SMEs translate early adoption into strategic advantage under conditions of uncertainty. The study also offers actionable guidance by showing that the most effective interventions for SMEs focus on strengthening foundational data and organizational capabilities rather than promoting complex AI systems beyond current readiness levels.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved from a field confined to technological research to a central driver of business transformation and competitiveness across industries (; ). In advanced economies, its strategic integration has reshaped operations, marketing, logistics, and innovation systems, enabling firms to become more agile, data-driven, and resilient (; ; ). Nevertheless, despite this global diffusion, the transition toward AI-enabled competitiveness remains highly uneven. The contrast between technologically mature ecosystems and resource-constrained emerging markets exposes persistent asymmetries in digital infrastructure, skills, and organizational readiness (; ; ). These disparities make the question of how SMEs in emerging economies can convert AI adoption into sustainable innovation and competitiveness both timely and critical.

Ecuador constitutes a representative case for examining AI adoption under resource constraints because its SME structure mirrors that of many emerging economies. Like Colombia and Peru, Ecuador’s productive fabric is dominated by micro and small firms with limited formalization, uneven access to digital infrastructures, and sectoral compositions centered on commerce, services, and light manufacturing. Similarly, Vietnam exhibits comparable patterns of capability scarcity, slow digital maturation, and fragmented adoption of advanced technologies. These parallels justify treating Ecuador as an analytically relevant context for understanding how structural constraints shape AI assimilation trajectories in emerging-economy SMEs.

In this broader landscape, Latin American SMEs face a combination of growing digital ambition and structural constraints, including limited financial capacity, fragmented infrastructure, and a shortage of AI-skilled professionals (; ; ; ). Ecuadorian firms, while increasingly aware of AI’s potential, still primarily use AI in marketing and customer-facing tasks, leaving core business processes largely untouched (; ). This situation exemplifies the paradox of technological modernization under scarcity: how can firms innovate sustainably when facing severe capability gaps? Understanding this tension provides not only empirical insight into an underexplored context but also theoretical opportunities to rethink how digital and dynamic capabilities emerge under constraints.

The originality of this study lies precisely in addressing that gap. Instead of viewing barriers to AI adoption merely as obstacles, this work reconceptualizes them as potential catalysts for capability development and strategic renewal. By integrating four complementary perspectives—the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, the Resource-Based View (RBV), and Dynamic Capabilities Theory—the study advances a unified explanation of how AI adoption translates into innovation and competitiveness under uncertainty (; ). The resulting AI-Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness captures this multi-stage transformation, bridging individual, organizational, and environmental dimensions. In doing so, it contributes to the broader debate on how AI-driven digitalization can strengthen firms’ dynamic and strategic capabilities, fostering resilience, innovation, and sustainable growth among SMEs in emerging economies (; ).

This article aims to explore the dual nature of barriers: rather than viewing them solely as obstacles, it argues that they also serve as levers for sustainable innovation and SME competitiveness. To this end, it builds on an empirical study conducted with 385 firms in Ecuador, which reveals both the low level of AI adoption and the structural constraints that hinder its expansion (). Based on this diagnosis, we propose the AI-Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness, which explains how SMEs in emerging contexts can transform their limitations into dynamic capabilities that promote both organizational resilience and business sustainability (; ). Grounded in this theoretical synthesis, the empirical analysis employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to validate the causal relationships among AI adoption, dynamic capabilities, and strategic innovation performance, bridging theory and evidence.

This study makes three key contributions. First, it provides an updated empirical analysis of AI adoption among SMEs in a developing country, a field in which evidence remains scarce (). Second, it introduces an interpretive approach that reconceptualizes barriers as potential drivers of innovation and sustainability (). Finally, it advances theoretical integration by combining the literature on artificial intelligence, sustainable innovation, and dynamic capabilities into a single explanatory model, offering actionable insights for researchers, managers, and policymakers (; ).

Beyond presenting Ecuadorian SMEs as a representative case of constrained digitalization, this study clarifies the broader relevance of examining AI adoption in resource-limited environments. Specifically, it explains how adoption emerges at the intersection of perceptual enablers (TAM/TOE) and adaptive capability-building processes (RBV/DCT). This allows the framework to reconcile two perspectives often treated as incompatible—rational, perception-driven adoption models and path-dependent, capability-based explanations—by conceptualizing AI adoption as an iterative, learning-oriented process rather than a discrete technological decision. This theoretical positioning enables the empirical findings to illuminate both adoption patterns and the mechanisms through which SMEs convert limited experimentation into capability development.

This study focuses on the four dominant SME sectors in Ecuador—commerce, services, manufacturing, and information technology—which together represent 86.28% of the national SME population. Agriculture, construction, and health were excluded because their technological processes, regulatory environments, and AI adoption pathways differ substantially from the functions analyzed in this study (e.g., marketing, finance, HR, logistics). These sectors, therefore, constitute analytically distinct cases rather than missing data, defining a clear boundary for the scope of this research.

2. Theoretical Framework

The adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has become strategically significant in recent years amid a global digital transformation that demands balancing operational efficiency, environmental sustainability, and social equity. However, recent studies reveal that the diffusion of AI among SMEs is highly uneven, showing persistent gaps between industrialized and emerging economies. For example, () and () document substantial disparities in AI adoption, attributing them to differences in human capital, digital infrastructure, and organizational capabilities. These findings align with other research suggesting that, although AI can act as a universal catalyst for innovation, its implementation without adequate organizational readiness may exacerbate pre-existing inequalities and foster technological dependence in developing countries (; ).

In the Latin American context, AI has been shown to improve business planning and forecasting among SMEs; however, adoption continues to face significant obstacles, including technological fragmentation and capability gaps. These dynamics underscore the need to understand the factors that drive or hinder AI adoption in SMEs from emerging economies, such as Ecuador. Additionally, it is important to analyze how these factors shape the development of digital and dynamic capabilities that sustain innovation and competitiveness amid uncertainty.

2.1. AI Adoption in SMEs: State of the Art in Emerging Contexts

Potential benefits and motivations. The literature consistently highlights the transformative potential of artificial intelligence (AI) for small and medium-sized enterprises. Its applications span operational optimization, cost reduction, service personalization, and enhanced data-driven decision-making. For example, SMEs can utilize AI in customer analytics, predictive maintenance, customer service chatbots, and logistics route optimization, achieving significant gains in productivity and service quality (; ). Recent studies in Europe indicate that integrating AI with other advanced technologies—such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data analytics—can further boost SME revenue growth by amplifying the value of digital transformation (). Likewise, research in emerging markets suggests that AI enables SMEs to respond more swiftly to environmental changes, becoming more resilient and innovative in the face of disruptions (; ; ; ). These findings support the notion that AI adoption, even in resource-constrained firms, can lead to improvements in sustainable performance—economic, social, and environmental—provided that the appropriate conditions are in place (; ).

Barriers and challenges in emerging contexts. Despite these potential benefits, SMEs face multiple technological, organizational, and contextual barriers that hinder effective adoption of AI.

From a technological perspective, the most salient constraints are limited access to high-quality data and to adequate computational infrastructure to implement advanced algorithms. Many SMEs lack integrated data platforms or up-to-date technologies, making it challenging to deploy scalable AI solutions.

At the organizational level, the shortage of qualified personnel and specialized AI knowledge remains a persistent challenge. Recruiting or training professionals skilled in data science, machine learning, or advanced analytics entails high costs that SMEs often cannot afford. Moreover, resistance to change and the absence of a digital culture within organizations further hinder adoption (; ; ). A high perception of risk and uncertainty about the return on AI investments also discourages decision-makers ().

In the environmental dimension, barriers include insufficient national-level digital infrastructure, unclear or nonexistent regulatory frameworks for AI, and weak institutional support for technological innovation among SMEs. Contextual factors such as market demand and competitive intensity also shape adoption behavior: in highly competitive sectors, SMEs feel stronger pressure to adopt AI to remain relevant, whereas in less dynamic environments, the perceived urgency is lower ().

A recent systematic review of the literature (2019–2024) highlights that digital infrastructure, organizational readiness, and governmental support are critical determinants of AI adoption in developing-country SMEs ().

In summary, the current state of the art (2023–2025) reveals a dual landscape: on one hand, a growing body of evidence demonstrating the benefits and successful cases of AI integration in SMEs; on the other, persistent structural barriers that hinder its diffusion in emerging contexts. This contrast underscores the importance of comprehensively analyzing AI adoption, taking into account technological, organizational, and environmental factors. It also involves examining the internal digital and dynamic capabilities that enable firms to overcome barriers and translate technological adoption into sustained competitiveness.

2.2. Technological and Organizational Approaches: TAM and TOE Framework

To understand the adoption of new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), models from information systems and technology management have been traditionally applied. One of the most influential is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), proposed by Davis, which argues that an individual’s attitude and intention to use a technology depend primarily on two perceptions: perceived usefulness—how beneficial the user believes the technology will be—and perceived ease of use—how easy it is to operate.

In the SME context, TAM suggests that managers and employees will adopt AI tools if they perceive them as advantageous for improving firm performance and not excessively complex to implement. Several studies applying TAM to SMEs have confirmed that analogous factors—such as relative advantage (similar to perceived usefulness) and technological compatibility with existing processes—positively influence the intention to adopt ().

However, TAM focuses mainly on the individual and internal perspective of adoption, without fully incorporating the external and contextual factors crucial to SMEs operating under resource constraints.

To address these limitations, the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, developed by (), offers a complementary, more systemic perspective. The TOE model proposes that the adoption of technological innovation depends on three interrelated dimensions:

- Technological factors, which include the characteristics of the technology (e.g., complexity, cost, availability, demonstrated usefulness);

- Organizational factors, encompassing firm-specific attributes (e.g., size, financial resources, human competencies, top management support, organizational culture);

- Environmental factors, which reflect external conditions (e.g., competitive intensity, customer and supplier pressure, government regulation, infrastructure, and institutional support).

Unlike the TAM, the TOE framework recognizes that the decision to adopt AI in an SME is influenced not only by user perceptions but also by the firm’s technological readiness, structural capacity, and the environmental conditions in which it operates.

Recent empirical evidence confirms the validity of the TOE framework in explaining AI and digital technology adoption among SMEs in different regions. For instance, a study in Saudi Arabia integrated TAM with TOE and found that relative advantage and compatibility (technology), sustainable human capital capacity and managerial support (organization), as well as market demand and government backing (environment), are all significantly associated with higher AI adoption in SMEs, which in turn improves operational and economic performance (). Likewise, research in India, Ghana, Egypt, and other developing countries shows that the availability of IT infrastructure, institutional support, and competitive pressures can either accelerate or slow down adoption decisions.

In summary, combining the TAM and TOE frameworks makes it possible to identify a comprehensive set of enablers—such as positive perceptions of usefulness, technological compatibility, organizational capacity, and external support—and barriers—such as perceived complexity, high costs, lack of skills, and unfavorable environments—that shape SMEs’ propensity to adopt AI solutions. However, these approaches mainly explain the decision and intention to adopt rather than the strategic outcomes of adoption. To understand how AI contributes to sustained innovation and competitiveness, it is necessary to extend the analysis beyond the adoption stage. This involves developing digital and dynamic capabilities that transform technological implementation into a lasting competitive advantage, as explored in the following section.

2.3. Resource-Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory

From a strategic management perspective, adopting artificial intelligence (AI) alone does not guarantee sustainable competitive advantages. The Resource-Based View (RBV) posits that a firm’s competitive advantage arises from the possession and deployment of resources and capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN).

Applied to AI, the RBV suggests that real strategic benefits emerge when a company integrates AI into its unique resource base and core processes in ways that competitors find difficult to replicate. In other words, simply adopting general-purpose AI tools—such as standard chatbots or cloud-based services—may enhance efficiency but seldom generate differentiation. These technologies, being widely accessible, eventually become technological commodities that fail to produce lasting advantage.

By contrast, when an SME combines AI with its intangible assets—for example, proprietary customer data, tacit market knowledge, or algorithms trained on its operational experience—AI becomes a unique strategic resource capable of providing a sustained competitive edge (; ).

Recent empirical evidence supports this view. (), analyzing European SMEs, concluded that internal capabilities such as expert personnel, an innovative culture, and visionary leadership have a greater impact on effective AI adoption than external support, underscoring that firms with stronger internal resources are more likely to integrate AI advantageously into their innovation strategies ().

In turbulent environments and emerging markets, however, what matters is not only the resources a firm currently possesses but also its ability to renew and reconfigure those resources as conditions change. This is where Dynamic Capabilities Theory becomes essential (). It emphasizes a firm’s ability to sense opportunities and threats in the environment, seize them by mobilizing and reallocating resources, and reconfigure its assets and routines to adapt to change.

Integrating AI into an SME can therefore be seen not merely as a technological decision, but as a catalyst for developing dynamic capabilities. For instance, employing AI in data analytics enhances a firm’s capacity to detect market shifts and customer preference changes (sensing); implementing AI pilot projects encourages management to redesign processes and business models (seizing); and the continuous incorporation of AI functionalities requires organizational restructuring, talent development, and change management (reconfiguring).

In this way, strategically aligned AI adoption builds a bridge toward continuous innovation: firms strengthen their learning, experimentation, and adaptation capacities, becoming more agile in innovating products, services, and processes. Recent studies confirm this linkage (). On one hand, AI acts as a tool that enhances dynamic capabilities by facilitating exploration, collaboration, and decision-making (e.g., decision-support systems, AI-enabled co-creation platforms). On the other hand, SMEs with more developed dynamic capabilities are better positioned to leverage AI for sustainable and resilient innovation in uncertain environments (; ).

It is important to note, however, that AI adoption also entails risks and challenges—such as dependence on external technology providers, algorithmic biases, and maintenance costs. Therefore, the development of robust internal capabilities, supported by external partnerships, becomes crucial to managing these risks effectively.

In summary, RBV and Dynamic Capabilities Theory add a strategic and integrative dimension to the theoretical framework. They explain how AI, once adopted, can—or cannot—generate sustainable innovation and long-term competitive advantage, depending on how deeply it is embedded within the firm’s resource base and how agile the organization is in renewing itself around the technology.

While Dynamic Capabilities Theory explains how firms renew, recombine, and leverage resources to generate performance under uncertainty, it does not fully account for how organizations with limited technological maturity initiate adoption or overcome early-stage constraints. Conversely, models such as TAM and TOE can explain intention and initial decision-making but cannot describe how post-adoption learning and reconfiguration processes unfold. This asymmetry indicates that no single framework can explain the complete pathway linking adoption, capability development, and strategic outcomes in resource-constrained SMEs. The integration of these perspectives is therefore not additive but necessary to capture the sequential and interdependent processes through which firms begin experimenting with AI and progressively build the adaptive routines that underpin strategic innovation.

2.4. Proposed Conceptual Framework: AI–Driven Dynamic Capabilities for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness

Building on previous theoretical approaches, we propose the AI–Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness. This framework explains how adopting artificial intelligence (AI) enables small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to develop organizational capabilities that transform technological adoption into strategic innovation and long-term competitiveness amid uncertainty.

In this model, the decision and extent of AI adoption by an SME are influenced by a multidimensional set of factors—technological, organizational, and environmental—derived from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework.

These factors include technological perceptions, such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, and compatibility with existing systems; organizational enablers, such as financial resources, managerial support, digital skills, and innovative culture; and environmental conditions, such as competitive pressure, customer demands, institutional support, and infrastructure readiness. Together, these elements act as contextual enablers or barriers that shape the likelihood and depth of AI implementation within SMEs ().

However, AI adoption is not conceived as an endpoint, but as a strategic mechanism that triggers capability development. Once integrated beyond isolated projects, AI initiates internal transformations that enhance the firm’s ability to sense opportunities, seize them through innovation, and reconfigure its resources and processes to adapt to changing environments.

These dynamic capabilities function as mediators between technological adoption and innovation outcomes, explaining how firms translate AI investments into superior performance. In this sense, AI adoption and dynamic capabilities are mutually reinforcing: digital technologies enable faster learning, experimentation, and adaptation, while strong dynamic capabilities allow firms to exploit AI more effectively to innovate and remain competitive.

Through this interplay, AI adoption fosters the emergence of digital capabilities—data-driven decision-making, predictive analytics, and digital collaboration—that complement and amplify dynamic capabilities. Together, they generate a synergistic capacity for strategic renewal and innovation in uncertain environments. This perspective reflects the growing recognition that AI’s competitive advantage lies not in the technology itself but in how organizations reconfigure their resources around it.

This integrative approach is necessary because TAM and TOE cannot explain why adoption remains superficial even when perceptions are favorable, whereas RBV and DCT do not account for how adoption begins in firms with limited resources. By combining these perspectives, the model reveals an emergent mechanism overlooked in prior research: SMEs initiate AI use in low-complexity, low-data functions—such as digital marketing—where complementary assets are minimal and only advance toward more demanding applications as capability-building progresses. This sequential pathway reconciles perception-based intention with the gradual formation of dynamic capabilities, addressing a long-standing tension between adoption-intention models and capability-based theories.

The need for an integrated framework becomes even more evident when considering the PLS-SEM results—particularly the strong effect of AI adoption on dynamic capabilities—which cannot be fully explained by DCT alone. While dynamic capabilities elucidate the mediating mechanism linking adoption and performance, they do not specify the antecedent conditions under which SMEs develop these capabilities or why adoption emerges only in low-complexity domains. TAM and TOE clarify these antecedent conditions by identifying the perceptual, technological, and environmental enablers that precede capability formation. In contrast, RBV explains how resource scarcity shapes both the trajectory of adoption and the pace of capability development. Their interaction yields a more comprehensive explanation of the empirical patterns observed, demonstrating that the integrated model captures mechanisms that no single theory can account for independently.

Notably, the synthesis of TAM, TOE, RBV, and DCT also reveals an emergent property absent from the individual frameworks: a phased, capability-dependent pattern of AI assimilation. SMEs first adopt AI in functions where data, skills, and process requirements are minimal; then translate these early experiments into basic sensing and reconfiguration routines; and only later expand adoption if these capabilities accumulate. Neither perceptual models nor capability-based theories predict this mechanism on their own. Its visibility arises precisely from the combination of perspectives, showing that the explanatory power of the framework exceeds the sum of its parts.

In summary, the AI–Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework integrates TAM, TOE, RBV, and Dynamic Capabilities Theory into a coherent causal logic in which (1) technological, organizational, and environmental factors determine the degree of AI adoption; (2) effective adoption strengthens dynamic capabilities by fostering learning, adaptation, and reconfiguration; and (3) these enhanced capabilities, in turn, drive strategic innovation performance and competitiveness. By articulating this causal sequence, the framework advances prior research beyond descriptive models of adoption, offering a theoretically grounded, empirically testable mechanism that links digital transformation to strategic innovation and organizational resilience in SMEs.

This framework also resolves a long-standing contradiction in the adoption literature by bridging TAM’s rational-choice assumptions with Dynamic Capabilities Theory’s emphasis on path dependency. In resource-constrained SMEs, AI adoption does not emerge as an entirely rational or historically determined process, but rather as an iterative learning process. Early adoption decisions—shaped by perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, and contextual readiness—enable low-complexity experimentation that gradually alters data practices, coordination routines, and decision-making processes. These incremental changes accumulate into sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities. In this way, perceptual enablers explain why firms take initial steps, while capability-building processes explain how those steps evolve into enduring organizational transformation, thus reconciling the rational-path-dependent divide.

Although the conceptual model is presented as a sequential process, the underlying mechanisms are inherently recursive. Dynamic capabilities theory suggests that weak innovation outcomes may erode managerial confidence, reduce future adoption intention, or reinforce conservative decision-making routines, thereby slowing subsequent capability development. In this sense, performance not only results from adoption and capability formation but also influences them through feedback loops. Recognizing these bidirectional effects clarifies that adoption trajectories are iterative and path-dependent rather than purely linear, and helps explain why SMEs may remain trapped in low-complexity, peripheral uses despite initial interest in AI.

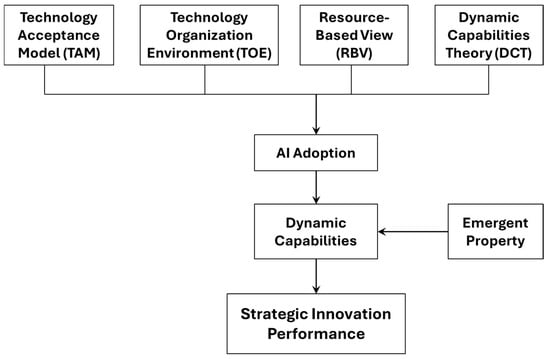

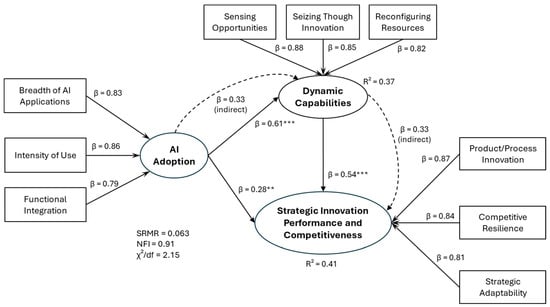

A visual representation of the integrated theoretical model is provided in Figure 1, summarizing how TAM, TOE, RBV, and Dynamic Capabilities Theory collectively structure the causal chain leading from AI adoption to dynamic capability formation and strategic innovation outcomes. The diagram also highlights the emergent property of the integrated framework: a sequential, capability-dependent pattern of AI assimilation that becomes visible only when the four perspectives are combined.

Figure 1.

Integrated Theoretical Framework Linking TAM, TOE, RBV, and Dynamic Capabilities Theory. This figure illustrates how the four theoretical foundations jointly explain the causal pathway from technological and organizational perceptions (TAM/TOE) to AI adoption, the emergence of Dynamic Capabilities (RBV/DCT), and the resulting Strategic Innovation Performance.

Importantly, this integrated perspective also suggests that the relationship between AI adoption and dynamic capability development may vary depending on the severity of resource constraints. SMEs facing significant technological, organizational, and financial barriers may activate more intensive sensing, learning, and reconfiguration routines once they commit to AI adoption, turning adversity into a catalyst for capability formation. This theoretical expectation motivates the inclusion of a moderation hypothesis in the empirical model, examining whether barriers strengthen the AI adoption → dynamic capabilities pathway.

2.5. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

Building on the theoretical foundations of the AI-Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness, this study examines how AI adoption enables SMEs to develop and leverage dynamic and digital capabilities that enhance innovation and competitiveness in volatile environments. The framework assumes that the strategic value of AI does not stem merely from the technology itself but from how firms integrate it into their resource base, learning processes, and adaptive routines.

2.5.1. Research Objectives

Obj. 1: Analyze the current state of AI adoption in Ecuadorian SMEs, identifying technological, organizational, and environmental enablers and barriers that influence adoption intensity and diversity.

Obj. 2: Examine how AI adoption contributes to the development of organizational dynamic capabilities in SMEs, particularly sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring abilities that enhance adaptability and innovation potential.

Obj. 3: Propose and empirically validate an integrated conceptual model linking AI adoption, dynamic capabilities, and strategic innovation performance and competitiveness. This framework explains how AI-driven digital capabilities strengthen firms’ strategic resilience and innovation outcomes amid technological and economic uncertainty.

2.5.2. Research Hypotheses

H1.

AI adoption in SMEs is positively influenced by technological, organizational, and environmental factors. Specifically, perceived advantages and ease of use (technological), the availability of internal resources and competencies (organizational), and a supportive institutional and market environment (environmental) increase the likelihood of AI adoption.

H2.

Effective AI adoption by SMEs has a positive impact on strategic innovation performance and competitiveness. Firms that integrate AI into their business processes achieve superior innovation outcomes—such as new product and process development, data-driven decision-making, and enhanced competitiveness in uncertain environments.

H3.

Organizational dynamic capabilities mediate and strengthen the relationship between AI adoption and strategic innovation performance and competitiveness. Specifically, AI adoption enhances a firm’s ability to sense opportunities, seize them through innovation, and reconfigure its resources, thereby translating technological adoption into sustained competitive advantage. SMEs with more developed dynamic capabilities derive greater strategic benefits from AI adoption than those with limited capabilities.

H4.

The positive effect of AI adoption on Dynamic Capabilities is stronger among SMEs facing severe technological, organizational, and financial barriers than among firms facing fewer constraints.

2.5.3. Conceptual Proposition

The AI-Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness posits a multi-stage causal chain in which technological, organizational, and environmental enablers lead to AI adoption, which in turn strengthens dynamic capabilities, ultimately enhancing strategic innovation performance and competitiveness.

This framework explains how AI adoption operates not merely as a technological choice but as a strategic mechanism that enables SMEs—particularly those in resource-constrained contexts such as Ecuador—to develop the adaptive capabilities and innovation potential that underpin firm competitiveness in turbulent environments.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological design of this study was conceived to ensure transparency, replicability, and statistical robustness in examining the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Ecuador. To address both diagnostic and causal objectives, the research followed a quantitative, sequential exploratory–confirmatory design composed of two complementary phases.

In the exploratory phase, descriptive and inferential analyses were performed to identify adoption patterns, sectoral and size-based differences, and perceived barriers. In the confirmatory phase, a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) approach was used to empirically validate the theoretical framework linking AI adoption, dynamic capabilities, and strategic innovation performance.

A structured and validated survey instrument served as the primary data source. Although the instrument included several dichotomous items to capture whether specific AI applications were present, the incorporation of a continuous Artificial Intelligence Adoption Intensity Indicator (IIIA) expanded analytical richness by quantifying the breadth and depth of AI integration across business functions.

The survey was applied to a stratified random sample of 385 SMEs, proportionally distributed by sector and firm size, which collectively represent over 86% of the national SME population. Instrument validation involved a two-stage process—expert review and a pilot test with 15 heterogeneous SMEs—to ensure clarity and content validity before large-scale deployment.

The section is organized as follows: Section 3.1 details the design and validation of the research instrument; Section 3.2 presents the population, sampling procedure, and proportional distribution of the sample; Section 3.3 describes the data processing and statistical techniques, including descriptive, inferential, and structural modeling methods; and Section 3.4 discusses methodological limitations and robustness safeguards.

3.1. Research Instrument

The primary research instrument used in this study was a structured and validated questionnaire designed to assess the degree of artificial intelligence (AI) adoption and the conditions influencing its implementation across Ecuadorian SMEs. The instrument operationalized the three central dimensions derived from the proposed conceptual framework:

- Access conditions. This dimension evaluated the resources and capabilities that enable firms to incorporate AI into their operations. The variables included:

- Availability of computing resources (hardware and software infrastructure);

- Internet connectivity suitable for AI applications;

- Existence of structured and accessible databases for AI-based analysis;

- Availability of qualified professionals with knowledge of AI systems;

- Financial capacity to invest in AI solutions.

- AI utilization. Respondents indicated whether their organizations had adopted specific AI applications across different business functions derived from the management and innovation literature:

- Marketing: customer service and sales, social media automation, customer data analysis, content generation, advertising optimization, market and trend analysis;

- Logistics: inventory optimization, order/shipping automation, route optimization;

- Human Resources: recruitment and selection, payroll management, employee performance evaluation;

- Finance and Internal Control: accounting automation, financial forecasting, fraud detection;

- Production and Innovation: design and prototyping, code assistants.

Each application was presented in a dichotomous format (yes/no) to ensure clarity and comparability across firms. To enhance analytical richness and move beyond simple binary reporting, responses were subsequently combined into a continuous Artificial Intelligence Adoption Intensity Indicator (IIIA)—a composite measure capturing both the breadth (number of functions) and the depth (number of tools) of AI adoption within each firm. Respondents were also invited to specify the exact platform or tool employed (e.g., ChatGPT, HubSpot AI, Google Ads AI). The survey did not request or record specific software versions, as this information was not essential to the analysis.

- 3.

- Barriers to adoption. To identify the main constraints affecting AI integration, firms indicated whether they experienced limitations in five areas: computing resources, internet connectivity, data availability, qualified professionals, and financial resources.

In addition to these three core dimensions, the questionnaire incorporated control variables describing organizational characteristics such as firm size (micro, small, medium) and sector (services, commerce, information technology, and industry). These variables were used for stratified analyses and group comparisons.

The final survey contained 22 items, mostly closed-ended dichotomous or categorical questions, complemented by open fields for specification. Average completion time was 15–20 min, minimizing respondent fatigue while maintaining adequate content coverage. These 22 items included all indicators required for the descriptive analyses, logistic regression, and PLS-SEM modeling used in this study. Dichotomous items capturing the presence of AI applications across business functions were combined to construct the AI Adoption Intensity Indicator (IIIA), and the reflective indicators used to operationalize Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Innovation Performance and Competitiveness were also derived from validated items embedded within the instrument. A complete list of the 22 items is provided in Appendix A, ensuring transparency and complete alignment between the questionnaire and the constructs included in the statistical models.

It is important to note that the AI Utilization items measure actual AI application usage, whereas the barrier items measure structural constraints. Although some adoption domains (e.g., accounting, financial forecasting) may be influenced by barriers related to data, skills, or resources, the constructs remain conceptually independent and were modeled separately.

Dynamic Capabilities were operationalized using three reflective dimensions consistent with the literature on sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring (; ). Sensing captured the firm’s ability to identify technological and market opportunities; seizing assessed the capacity to mobilize resources and implement innovation initiatives; and reconfiguring measured the ability to adjust structures, processes, and routines in response to environmental uncertainty. Each dimension was measured through validated reflective indicators adapted from prior studies on dynamic capabilities in emerging-economy SMEs ().

Strategic Innovation Performance and Competitiveness was measured through three complementary subdimensions: product/process innovation (the extent to which firms introduce new or improved products and processes), strategic adaptability (the ability to adjust strategies and decision-making based on changing environments), and competitive resilience (the capacity to maintain or strengthen market positioning under uncertainty). These were assessed using validated reflective items aligned with previous research on SME innovation and strategic competitiveness. Together, these indicators capture the multidimensional nature of innovation performance in resource-constrained contexts.

Validation Process

To ensure methodological rigor, the instrument underwent a two-stage validation process:

- Expert panel review. Seven university professors—four from administrative sciences and three from computer science, each with more than ten years of research experience—evaluated the instrument for content and face validity. They examined item wording, conceptual relevance, coverage of constructs, and logical flow. Consensus confirmed that the questionnaire was clear, internally coherent, and aligned with the study’s objectives.

- Pilot test. The pretested version was administered to 15 SMEs selected to represent the diversity of the four target sectors and firm sizes. The pilot’s purpose was procedural—to assess wording clarity, comprehension, and completion time—rather than statistical estimation. For pilots focused on usability and content validation, sample sizes between 10 and 30 cases are methodologically appropriate; thus, n = 15 is acceptable. Feedback led to minor lexical and sequencing adjustments to eliminate ambiguity and ensure smooth administration.

To further guarantee reliability and robustness, post-pilot psychometric checks were conducted on the full dataset (n = 385), including internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.80), composite reliability (CR > 0.80), and convergent and discriminant validity using Fornell–Larcker and HTMT criteria during the PLS-SEM stage.

Together, these procedures ensured that the instrument met recognized standards of clarity, validity, and reliability for large-scale survey research.

3.2. Population and Sampling

The sampling strategy was designed to capture a representative snapshot of Ecuador’s SME ecosystem while maintaining analytical rigor and proportional comparability across economic sectors and firm sizes. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Ecuador (), the national ecosystem of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) comprises over 1.2 million organizations, which are unevenly distributed across industries.

Given this magnitude and heterogeneity, a stratified random sampling procedure was adopted to ensure proportional representation across economic sectors and enterprise sizes. This dual stratification improves precision and reduces sampling error, thereby strengthening the external validity of the findings.

3.2.1. Sample Size Determination

The required sample size was computed using the infinite-population formula (Equation (1)), assuming a 95% confidence level (k = 1.96), maximum variability (p = q = 0.5), and a 5% margin of error (e = 0.05):

where

- n = sample size

- k = critical value from the normal distribution (1.96 for 95% confidence)

- p = expected proportion of success (0.5, used to maximize variability)

- q = 1 − p

- e = margin of error (0.05)

Thus, a minimum of 385 firms was required, providing sufficient statistical power for both descriptive and inferential analyses, including PLS-SEM.

To determine the minimum required sample size, the study used the standard infinite-population formula for proportion-based surveys (), which is widely recommended for large, heterogeneous business populations such as national SME ecosystems. The calculation assumed a 95% confidence level (k = 1.96), a 5% margin of error (e = 0.05), and maximum variability (p = q = 0.5). This approach ensures statistical representativeness and adequate power for multivariate analyses, including PLS-SEM. In line with methodological guidance for structural modeling (), using this formula ensures the sample meets the minimum recommended thresholds for model estimation and discriminant validity assessment. The resulting minimum sample size was 385 SMEs, which matched the final dataset.

3.2.2. Sectoral Stratification

To ensure analytical coherence, the study focuses on the four dominant SME sectors in Ecuador—commerce, services, manufacturing, and information technology—which together account for 86.28% of the national SME population (Table 1). Agriculture, construction, and health, which represent the remaining 13.72%, were excluded not because of their size but because their production structures, regulatory constraints, and technological processes differ fundamentally from the operational domains analyzed in this study (marketing, finance, HR, logistics, and process management). Including these sectors would have introduced structural heterogeneity, compromising construct validity for AI adoption, dynamic capabilities, and innovation performance. Their exclusion, therefore, reflects a deliberate analytical delimitation rather than missing data, allowing the model to capture adoption dynamics within the typical operational environments of mainstream urban SMEs.

Table 1.

Distribution of Ecuadorian SMEs and proportional sample size.

The resulting sectoral composition provides a robust, policy-relevant representation of Ecuador’s business structure, focusing on areas where AI adoption and innovation are most evident.

3.2.3. Size Stratification

In accordance with Ecuadorian legislation, enterprises were classified as micro (1–9 employees), small (10–49 employees), and medium A (50–99 employees). As shown in Table 2, microenterprises constitute the vast majority of SMEs (≈76%), a pattern mirrored in the sample.

Table 2.

Composition of the sample by firm size.

The underrepresentation of medium-sized firms reflects their actual scarcity in the national population rather than sampling bias. To mitigate potential “micro-firm skew,” results were analyzed using size-stratified weights and tested for group differences using ANOVA and the Kruskal–Wallis test (see Section 4.5). This ensures that patterns observed among microenterprises do not unduly dominate the aggregate interpretation.

3.2.4. Summary of Representativeness

The dual stratification by sector and size ensures that the sample accurately mirrors the structural composition of Ecuador’s SME ecosystem. The predominance of microenterprises reflects the empirical reality of the national economy and justifies the emphasis on resource-constrained innovation strategies. Small and medium firms were deliberately included to enable comparative analyses and capture heterogeneity in AI adoption maturity.

Although the study is based on cross-sectional, self-reported data—a limitation standard in organizational research—the design remains adequate for exploratory–confirmatory modeling. The use of validated instruments, proportional stratification, and multi-technique analyses (ANOVA, logistic regression, and PLS-SEM) collectively enhances the external validity and robustness of the findings.

In summary, the sampling strategy ensures that the data provide a statistically representative and analytically coherent foundation for diagnosing AI adoption patterns and testing the proposed theoretical framework within Ecuador’s SME landscape.

3.3. Data Processing

All data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and SmartPLS 4. The analytical procedure was structured to generate both a descriptive diagnosis of AI adoption patterns and inferential validation of the proposed causal framework.

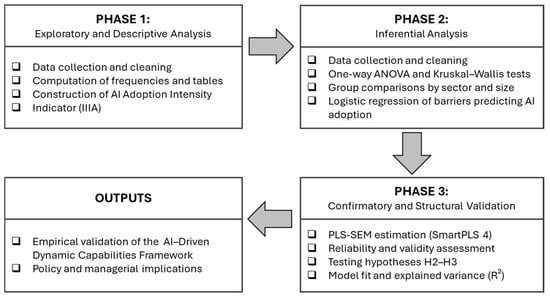

To ensure transparency and robustness, the analysis followed a multi-phase sequence that integrated descriptive, inferential, and structural modeling techniques suitable for categorical and continuous data. Figure 2 summarizes this analytical workflow, structured into three interconnected phases—exploratory, inferential, and confirmatory—which ensure methodological coherence between the descriptive diagnosis of AI adoption and the structural validation of the proposed framework.

Figure 2.

Analytical workflow of the study. Note: Authors’ elaboration based on survey data from 385 Ecuadorian SMEs.

Descriptive Statistics. Absolute and relative frequencies were computed for all variables to provide a detailed overview of adoption rates across business functions, the prevalence of perceived barriers, and the structural characteristics of the surveyed firms. Cumulative distributions and cross-tabulations were used to explore adoption diversity across sectors and firm sizes.

AI Adoption Intensity Indicator (IIIA). To move beyond the binary nature of adoption responses, an Artificial Intelligence Adoption Intensity Indicator (IIIA) was constructed. This continuous metric captures both the breadth of AI deployment (number of business functions using AI) and the depth (number of applications per function), thus quantifying adoption diversity.

The indicator is calculated as (Equation (2))

where represents the number of AI applications reported by firm i, and n is the total number of firms.

Values range from 0 (no AI use) to the maximum number of applications included in the instrument. This measure allows for continuous comparison of adoption intensity across firms, sectors, and size categories.

Example: Suppose three SMEs adopt AI in 3, 1, and 0 business functions, respectively. Substituting into the formula yields an average of 1.33, indicating that AI is used in slightly more than one function per firm. Higher IIIA scores denote broader functional integration, while lower scores indicate marginal adoption.

One-Way ANOVA. A one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tested mean differences in AI adoption levels across groups defined by economic sector (services, commerce, IT, and industry) and firm size (micro, small, medium). The null hypothesis stated that mean adoption levels do not differ significantly across groups. Where the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were met, parametric results were reported.

Kruskal–Wallis Non-Parametric Test. For variables not meeting parametric assumptions, the Kruskal–Wallis H test served as a robust non-parametric alternative to ANOVA. This test compared the median ranks of adoption and barrier variables among groups, providing validation of inter-group differences without requiring normal distribution of residuals.

Logistic Regression Model. To identify which structural barriers most strongly explain AI adoption, a binary logistic regression model was estimated. The dependent variable, AI adoption, was dichotomously coded as

- 1 = firm uses at least one AI application;

- 0 = firm does not use AI.

Independent variables included the five principal barriers identified in the literature: (i) limited computing resources; (ii) internet connectivity constraints; (iii) lack of structured databases; (iv) shortage of qualified professionals; and (v) insufficient financial resources.

Model adequacy was assessed using the −2 Log Likelihood, Cox & Snell R2, Nagelkerke R2, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (p > 0.05 indicating acceptable fit).

This procedure ensured that only statistically significant predictors were retained, thus isolating the barriers with the strongest explanatory power.

Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM Validation of Hypotheses H2 and H3)

To empirically validate the causal relationships proposed in the AI–Driven Dynamic Capabilities Framework for Strategic Innovation and Competitiveness—specifically Hypotheses H2 and H3 concerning the mediating role of Dynamic Capabilities—a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis was conducted using SmartPLS 4 software. This technique was selected because it is particularly suitable for exploratory research, small-to-medium sample sizes, and models combining formative and reflective constructs.

Model Specification. The structural model included three latent variables:

- AI adoption, measured through the breadth and intensity of AI applications implemented across different business functions (marketing, logistics, human resources, finance, and production).

- Dynamic capabilities, reflecting the firm’s ability to sense opportunities, seize them through innovation, and reconfigure its resources in response to environmental and market uncertainty.

- Strategic innovation performance and competitiveness, capturing improvements in products, processes, or business models that enhance innovation outcomes, adaptability, and long-term competitive advantage.

All measurement items were derived from the validated questionnaire and literature-based indicators (; ; ; ).

Estimation and Validation Procedure. Following (), (), and () the analysis proceeded in two stages:

- Measurement Model Evaluation, assessing internal consistency (Cronbach’s α, Composite Reliability), convergent validity (Average Variance Extracted, AVE), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker and HTMT criteria).

- Structural Model Evaluation, estimating standardized path coefficients, significance levels, and indirect (mediated) effects using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples.

Model adequacy was further assessed through R2 coefficients (explained variance), Stone–Geisser’s Q2 predictive relevance, and global goodness-of-fit indices, including the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and the Normed Fit Index (NFI).

Expected Relationships. Consistent with the conceptual framework (Figure 1), the structural model posits that:

- AI adoption exerts a positive effect on Strategic innovation performance and competitiveness (H2);

- AI adoption positively influences Dynamic capabilities (H3);

- Dynamic capabilities, in turn, positively affect Strategic innovation performance and competitiveness (H3);

- Dynamic capabilities partially mediate the link between AI adoption and Strategic innovation performance and competitiveness (H3).

The results of this analysis are reported in Section 4.6 (Structural Equation Modeling Results), where the direct, indirect, and total effects are presented along with model fit statistics and explained variance.

Moderation Test for H4. In addition to testing the direct and mediating effects proposed in H2 and H3, the empirical design incorporated a moderation test to evaluate H4. To examine whether technological, organizational, and financial barriers amplify the effect of AI adoption on dynamic capabilities, a multi-group PLS-SEM (MGA) procedure was implemented. A cumulative barrier index was created using the five constraint variables included in the survey (computing resources, internet connectivity, structured databases, qualified professionals, and financial capacity). Firms were classified into high-barrier and low-barrier groups using a median-split procedure, following established guidelines for MGA in PLS-SEM. The analysis relied on both Henseler’s MGA and a permutation test to determine whether differences in path coefficients between groups were statistically significant. This approach ensures a robust assessment of the “barriers-as-catalysts” argument underlying H4.

3.4. Methodological Limitations

Although the methodological design ensured proportional representation of Ecuadorian SMEs by sector and firm size, several limitations must be acknowledged.

- Underrepresentation of medium-sized enterprises. While the inclusion of medium-sized firms followed proportional criteria consistent with national statistics, their relatively small number in the overall population limits the robustness of size-based comparative analyses. This underrepresentation reflects the structural composition of Ecuador’s SME ecosystem rather than a sampling bias.

- Self-reported data. The study relied on managerial self-assessments, which may introduce perceptual bias—particularly when distinguishing between genuine AI applications (e.g., machine learning–based systems) and traditional digital tools (e.g., basic accounting or ERP software). To mitigate this issue, the questionnaire included clarifying examples of AI technologies, and subsequent analyses validated internal consistency and construct reliability (α, CR, AVE, HTMT) to ensure the coherence of measurement.

- Cross-sectional design. The survey provides a static snapshot of AI adoption at a single point in time, which limits its ability to capture sequential implementation or learning effects. Consequently, causality should be interpreted with caution. Future longitudinal or panel studies are encouraged to trace adoption trajectories and dynamic capability development over time.

- Exclusion of minor sectors. The focus on the four major sectors—services, commerce, information technology, and industry—ensured coverage of 86.28% of Ecuadorian SMEs. However, the exclusion of smaller sectors such as agriculture, construction, and health reduces the generalizability of findings to the entire SME population. This exclusion was an analytical decision aimed at maintaining sectoral comparability and statistical homogeneity across strata.

- Single-source survey bias. As data were collected from a single respondent per firm, common-method variance cannot be entirely ruled out. Nevertheless, procedural remedies were applied: items were clearly worded, anonymity was guaranteed, and method bias was checked through internal reliability diagnostics and bootstrapped PLS-SEM estimations.

Despite these constraints, the use of a stratified random sampling design, a validated instrument, and a multi-technique analytical approach (ANOVA, logistic regression, and PLS-SEM) considerably enhances the methodological robustness of the research. Taken together, these safeguards ensure that the results provide a reliable and representative diagnosis of AI adoption among Ecuadorian SMEs, as well as a sound empirical basis for testing the proposed AI–driven dynamic capabilities framework.

4. Results

4.1. Overall AI Adoption and Functional Distribution

The level of AI adoption among Ecuadorian SMEs is remarkably low and uneven. An AI Adoption Intensity Index (IIIA) was calculated to quantify overall adoption, yielding a value of only 0.04, indicating minimal integration of AI technologies on average. In practice, adoption is highly concentrated in a narrow set of business functions, primarily in marketing and customer-facing activities, with minimal implementation in finance, logistics, and human resources. This pattern is consistent with recent evidence from Ecuadorian microenterprises, where AI use is similarly minimal and confined to basic marketing tasks (). This implies a very low functional diversity in current AI use, as most firms employ AI in at most one area of operation.

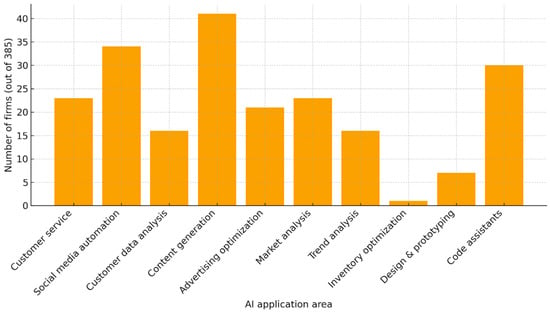

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of AI usage across primary business functions.

Figure 3.

Business functions in which artificial intelligence is applied.

Notably, certain functions show virtually no AI adoption. In particular, human resource management and internal control (accounting/auditing) had no instances of AI tools in use among the surveyed firms. Standard software applications in these areas (e.g., payroll systems, accounting packages) do not meet the defining criteria of AI and therefore were not counted. Likewise, core financial management and supply chain/logistics functions saw almost no AI-driven solutions deployed, aside from isolated experimental cases. For example, only one industrial firm reported using AI for inventory optimization (an operations/logistics task), and no SMEs applied AI to financial forecasting or fraud detection in the sample. This figure shows that marketing and IT are the only functions with notable AI adoption, whereas HR, finance, and internal control show no AI use in the sample. Professional tools used in non-AI fashion (e.g., standard accounting software) were excluded, reflecting broader evidence that digital transformation in accounting and financial processes among Ecuadorian SMEs remains limited to basic software rather than AI-capable systems ().

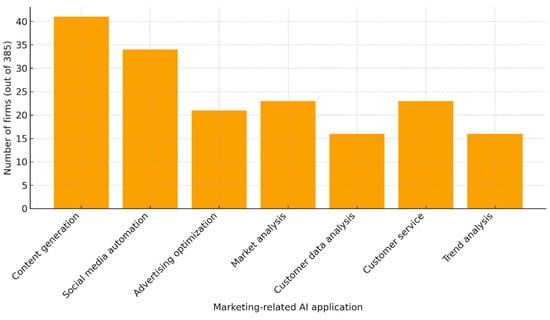

By contrast, marketing is the functional area with the greatest variety of AI applications (Figure 4). Most implementations were concentrated in content generation, social media automation, and market or trend analysis, reflecting the tendency of SMEs to adopt AI first in low-integration, customer-facing functions (). These results also align with recent evidence showing that generative AI is reshaping business behavior, consumer responses, and digital interaction models ().

Figure 4.

Use of artificial intelligence in marketing functions.

Additional marketing and sales uses, such as customer data analysis (for targeted marketing) and customer service chatbots, were reported by a smaller subset of firms. Within the IT/technology function, a modest level of AI use was noted, primarily in code-assistant tools (e.g., AI-based programming aids). These tools—such as GitHub Copilot or ChatGPT used for coding—were the only significant AI applications in IT departments, and even those were limited to a few tech-oriented companies. No other IT or cybersecurity applications of AI (e.g., AI-driven cybersecurity, network optimization) were recorded. This figure details the distribution of AI use within marketing-related activities. The highest usage is in advertising and digital marketing tasks—specifically automated content creation, social media management, online advertising optimization, and market trend analysis. Lesser but notable uses include customer analytics and AI chatbots for sales/customer service. These results demonstrate that marketing departments are leading the adoption of AI in Ecuadorian SMEs, whereas back-office functions are lagging.

To better understand what tools firms are using, specific AI software identified in each functional area was tabulated (Table 3).

Table 3.

AI tools reported by business functions.

For instance, marketing teams reported using content generation assistants such as Copy.ai and Canva AI, social media schedulers with AI features (e.g., Hootsuite AI), and analytics tools such as Brandwatch AI for market research. In customer service and sales, chatbots (notably ChatGPT-based services) are the primary AI tools deployed. Meanwhile, IT personnel in a few firms leveraged AI code assistants (e.g., GitHub Copilot or ChatGPT) to generate or debug code. These examples underscore that the current AI usage is limited to readily available AI-driven tools, often cloud-based services, rather than custom or integrated AI systems. Despite these individual examples, it must be emphasized that overall adoption remains very low—only a small fraction of firms use AI at all, and those that do tend to apply it in one or two specific tasks. This finding aligns with the notion of “partial adoption”, wherein SMEs experiment with a few AI applications rather than undertaking comprehensive AI integration.

4.2. AI Adoption by Sector

Patterns of AI adoption vary across economic sectors, reflecting differences in industry focus and digital maturity. Table 4 summarizes the absolute number and percentage of firms using AI applications in each sector (services, commerce, information technology, and manufacturing/industry).

Table 4.

Absolute and relative frequency of AI use by sector.

The data reveal that all sectors have low overall adoption, but the types of AI use differ markedly across sectors. Service and commerce firms—which together represent the bulk of the sample—primarily use AI for marketing and customer-facing functions, while industrial and IT sector firms (though fewer in number) account for most operational and technical AI applications.

In the services sector—which includes tourism, education, and professional services—AI adoption is primarily focused on marketing activities. About 13% of firms use AI for content generation and around 11% for social media automation (Table 4), confirming that digital marketing is the main entry point for AI. Other uses, such as customer chatbots or data analytics, appear in fewer than 10% of cases, while applications in logistics or product design are absent. A similar pattern emerges in commerce, where roughly 13% of firms use AI for marketing content creation and 12% for social media, with almost no adoption in back-office or operational areas. In both sectors, therefore, AI is limited to customer-facing processes and extends only sparingly to internal management, supply chains, or R&D.

By contrast, the industrial and IT sectors—which are more technology-intensive—show distinct patterns. Industrial firms display very low marketing AI use (~4%), but some adoption in technical operations, notably in inventory optimization and product design prototyping, where a few companies employ neural networks or generative design tools. The IT sector exhibits the most remarkable diversity of applications: 39% of firms use AI code assistants and about 11% apply AI to design or prototyping tasks (e.g., Figma AI). These rates far exceed those of non-technical sectors, highlighting their higher digital maturity. The contrast is striking—code-assistant tools are used by 39% of IT and 56% of industrial firms, compared with none in services or commerce—indicating that technical sectors are the early adopters of AI for production and development.

Overall, the sectoral analysis reveals a clear divide. Non-technical SMEs (services and commerce) have adopted AI mainly for marketing and even then only marginally. In contrast, technical sectors (IT and industry) use AI more broadly, including in core operational processes. These differences, statistically confirmed through ANOVA tests (Section 4.5), reflect how sector-specific factors—product nature and technical expertise—shape adoption behavior. The pattern mirrors international evidence: AI diffusion is markedly higher in technology-intensive industries and far lower in traditional service sectors. Notably, Table 4 shows that 56% of industrial firms report using code assistants, compared to none in services and commerce; this sectoral divergence in technical AI use is a non-trivial pattern that is further examined in the Discussion.

4.3. AI Adoption by Firm Size

The propensity to adopt AI technologies increases with firm size among Ecuadorian SMEs; however, even the largest medium-sized firms exhibit only partial adoption. In our sample, micro-enterprises (firms with <10 employees) exhibited the lowest levels of AI use, while small (10–49 employees) and medium (50–199 employees) enterprises were progressively more likely to implement AI. Table 5 presents the frequency of AI usage by company size, detailing the share of firms in each size category that utilize AI for various functions.

Table 5.

AI adoption by company size.

AI adoption among Ecuadorian SMEs increases with firm size but remains limited overall. Micro-enterprises, which make up most respondents, show minimal adoption across all functions—less than 10% in any category. About 9% use AI for content generation and 8% for social-media automation, while only 5% employ chatbots for customer service, and around 3–4% use AI for analytics or trend analysis. There are no reported applications in inventory management or product design, indicating an early exploratory stage focused on basic, low-cost tools for customer engagement (Table 5).

Small enterprises exhibit substantially higher adoption, particularly in marketing. Over half (≈56%) use AI for content creation and 44% for social-media automation—five times the rate of micro-firms. Around 12% employ AI for customer data or trend analysis. These firms typically implement one or two marketing-related applications rather than a comprehensive digital transformation, reflecting limited but targeted experimentation.

Medium-sized enterprises (50–199 employees) demonstrate the most extraordinary functional diversity. Half use AI code assistants for IT tasks, and about 25% apply AI to content generation, inventory optimization, or design/prototyping. Their higher adoption reflects greater financial and human resources, yet usage remains fragmented and project-based rather than organization-wide.

Overall, company size strongly influences adoption levels, as confirmed by one-way ANOVA (Section 4.5). Larger firms have the resources and skills to experiment with AI, whereas micro- and small enterprises lag due to financial and capability constraints. Still, even medium-sized firms show only partial integration, underscoring that Ecuadorian SMEs as a whole are at an early stage of AI diffusion and digital maturity.

4.4. Barriers to AI Adoption

Survey respondents were asked to identify which factors were hindering or preventing AI adoption in their organizations. The results show that SMEs face multiple concurrent barriers, with talent, data, and financial limitations being the most severe obstacles.

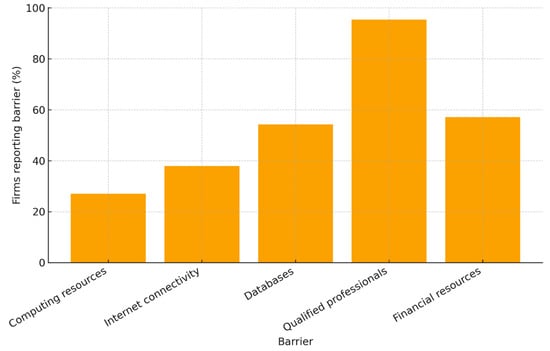

Figure 5 depicts the overall frequency with which each barrier was recognized, and Table 6 and Table 7 break down these frequencies by sector and by firm size, respectively. Every one of the five barriers surveyed was cited by at least 27% of firms, indicating that none of these challenges can be disregarded. This suggests a pervasive awareness of constraints even among companies not currently using AI.

Figure 5.

Frequency of barriers to AI adoption.

Table 6.

Barriers to AI adoption by sector.

Table 7.

Barriers to AI adoption by company size.

The most frequently reported barrier to AI adoption is the lack of qualified professionals. These barriers mirror findings from broader analyses of Ecuadorian SMEs, which highlight capability gaps, limited infrastructure, and financial constraints as key inhibitors of AI integration (). Almost all surveyed SMEs—95% of microenterprises and nearly all small and medium firms—identified insufficient AI skills as the main impediment to implementation. This confirms that, even when tools are accessible, the shortage of personnel capable of evaluating, integrating, and maintaining AI systems is the critical bottleneck.

The second significant barrier is the lack of structured data and databases. About 55% of micro-enterprises and 75% of medium-sized firms cited this limitation, compared with only 25% of small firms. Many SMEs still lack organized, digitized data sources, limiting their ability to apply machine learning or data-driven analytics effectively. The third most common constraint is limited financial capacity. Approximately 58% of microenterprises and 75% of medium-sized firms reported budget constraints. In comparison, only 31% of small firms did—possibly because basic AI tools are more affordable or because external support is available. Despite this variation, financing remains a significant obstacle after skills and data availability.

Infrastructure-related barriers were less frequent but still significant: 27% of firms reported insufficient computing equipment, and 38% reported poor internet connectivity. These issues disproportionately affect micro and small businesses, especially in regions with limited bandwidth or outdated hardware, further hindering AI deployment. Overall, these findings indicate that human capital and data limitations, more than cost or infrastructure, are the primary inhibitors of AI adoption among Ecuadorian SMEs—a pattern consistent with other developing economies.

Sectoral differences further illustrate these disparities (Table 6). Only 30% of IT-sector firms cited inadequate computing resources, versus over 50% in other sectors, and about 80% reported skill shortages compared with 95–100% elsewhere—confirming that tech-oriented firms possess relatively better talent and infrastructure.

These differences were statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis p < 0.001 for both computing resources and qualified professionals), while financial and connectivity barriers showed no significant variation across sectors (p > 0.2).

Barriers to AI Adoption by Company Size. Table 7 shows that medium-sized enterprises face the identified barriers almost uniformly.

For example, all medium firms reported a shortage of qualified professionals, while 75% cited both limited databases and financial constraints. By contrast, micro- and small enterprises acknowledged similar challenges but with slightly lower frequency, highlighting how the severity of barriers intensifies as firm size increases.

Barriers vary moderately by firm size (Table 7). All medium-sized enterprises reported a lack of qualified AI professionals (100%), and most cited insufficient data (72%) and limited financial resources (72%). Although these figures partly reflect their small number (n = 25), they underscore that even larger SMEs face severe capability shortages. Micro and small enterprises reported similar constraints, though the lack of structured databases differed significantly by size (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.041, η2 = 0.06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.11]): 72% of medium, 55% of micro, and only 25% of small firms identified this as a limitation. Smaller firms may not yet require data-intensive systems, whereas larger ones recognize the deficit more acutely.

By contrast, the shortage of skilled personnel is nearly universal (94–100% across all groups), and financial and connectivity constraints did not vary significantly by size (p > 0.05), confirming that these remain common challenges for Ecuadorian SMEs regardless of scale.

These barriers are interconnected, forming a collective obstacle to AI diffusion. The results are consistent with global studies that identify human talent, data infrastructure, and financial constraints as key inhibitors of SME digitalization. Complementary logistic regression analysis confirmed that these barriers significantly reduce the likelihood of AI adoption, with the skills gap emerging as the strongest predictor of non-adoption.

Encouragingly, more than 70% of non-adopting SMEs expressed intentions to implement AI, suggesting latent demand and readiness to adopt once conditions improve. This highlights the importance of targeted policy interventions—such as workforce training, data-sharing mechanisms, and financial incentives—to convert interest into effective adoption and bridge Ecuador’s SME digital capability gap.

4.5. Statistical Analysis of Differences

To verify the differences in adoption patterns described above, we conducted formal statistical tests. A one-way ANOVA was used to test for significant differences in AI usage across the four sectors and across the three size categories.

The ANOVA results (Table 8) reveal that sector significantly influences AI adoption in four application areas—social media automation, content generation, inventory optimization, and product design/prototyping (all p < 0.001).

Table 8.

One-Way ANOVA: Differences in AI Adoption by Sector and Size.

Service and commerce firms show higher adoption of marketing-related AI (≈12–13%) than industrial firms (≈4%). At the same time, inventory optimization and prototyping are concentrated in the industry and IT sectors, explaining the observed sectoral effect. For other applications (e.g., customer service, advertising, analytics), sectoral differences were nonsignificant (p > 0.05), indicating uniformly low adoption across industries.

Company size displayed the same pattern: significant effects for social media automation, content generation, inventory optimization, and design/prototyping (all p < 0.001), with larger firms adopting these tools more frequently. Customer service AI also varied modestly by size (p ≈ 0.03), driven by medium-sized enterprises (≈25%) versus micros (≈5%). No significant differences emerged for advertising optimization (p ≈ 0.08) or analytical uses (p > 0.2), confirming that these remain rare across firm sizes. These results corroborate previous findings—larger and more technical firms are consistently ahead in specific AI applications.

For barriers, Kruskal–Wallis tests showed only two significant differences (Table 9). The lack of computing resources varied by sector (p < 0.001), with IT firms reporting fewer hardware constraints. The absence of structured databases differed by firm size (p = 0.041), with medium-sized firms citing this limitation most frequently. Other barriers—connectivity, talent, and finance—showed no significant variation (all p > 0.05), confirming that skills shortages and financial constraints are pervasive across all SMEs. These findings align with expectations: IT firms face fewer infrastructure problems, whereas larger enterprises are more conscious of data requirements, reinforcing the descriptive patterns observed in Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.

Table 9.

Kruskal–Wallis Test for Barrier Differences.

In summary, the statistical analysis confirms the central patterns of AI adoption among Ecuadorian SMEs. Overall usage remains low but varies significantly across sectors and firm sizes. Marketing-related applications are more common in commerce and service firms, while technical uses—such as inventory optimization and prototyping—are concentrated in technology-intensive sectors. Larger firms consistently report higher adoption rates than micro-enterprises, particularly in these exact domains.