1. Introduction

In today’s context, diversity, inclusion, and personal development within organizations have become essential aspects for ensuring sustainability, social responsibility, and business competitiveness. However, despite the growing social and regulatory attention given to these issues, the influence of board characteristics on the promotion of corporate equality has, until now, received limited attention in academic literature. This conceptual gap restricts our understanding of how governing bodies can act as drivers of change in implementing diversity and inclusion policies, particularly within the European environment, which is increasingly shaped by stricter and more demanding regulations.

In this study, we introduce a new variable called “Corporate Equality.” This variable is defined in this study as a composite measure that reflects a company’s commitment to diversity and inclusion (D&I) within its structure and organizational practices. Based on the methodology of Refinitiv’s Global Diversity and Inclusion Index, the variable is constructed from 24 standardized indicators across four fundamental pillars: diversity (e.g., gender, ethnicity, or age in the workforce and governing bodies), inclusion (policies and practices that foster integration and fairness), people development (initiatives for training, promotion, and retention of diverse talent), and news/controversies (publicly available information affecting the company’s reputation in these areas). However, for our purposes, we focus only on three pillars: diversity, inclusion, and people development. We exclude the news/controversies pillar due to its exogenous nature in relation to internal practices and potential media coverage bias. We reproduce the analyses as a robustness test, including this pillar, and confirm that the qualitative conclusions remain unchanged. The information is collected and processed by ESG data analysts, ensuring both quality and comparability across companies globally. Thus, “corporate equality” not only captures firms’ current performance in D&I but also reflects structural and sustained efforts toward a more equitable and inclusive organizational culture.

Equal opportunities and non-discrimination are essential rights recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (

ONU, 1948). Nevertheless, in recent years, initiatives such as “Me Too” and “Black Lives Matter” have highlighted the importance of diversity and equity, creating greater social and political pressure on companies to commit to these areas (

Manoharan et al., 2021;

Shohaieb et al., 2022). Moreover, equality within companies cannot only be understood as a matter of internal policies, but also as part of social identity dynamics and cultural stratification. In this regard,

Navarro and Zaragoza (

2024) analyze how gender and other dimensions of social stratification operate jointly within institutional contexts, which reinforces the need to examine business practices from a structural and intersectional perspective.

In this context, stakeholders expect organizations to demonstrate greater transparency in their actions and outcomes regarding diversity and inclusion as part of their D&I policies (

Vuontisjärvi, 2006). Despite growing interest, published literature on these topics remains limited (

Manoharan et al., 2021;

Shohaieb et al., 2022).

Moreover, the adoption of Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, dated 22 October 2014, marked a significant milestone in regulating non-financial and diversity disclosures by large companies and certain groups. This directive, which amended Directive 2013/34/EU, established for the first time the obligation to disclose information on the diversity policies implemented by companies, the objectives set in this regard, and the results achieved. This regulatory framework aims to enhance corporate transparency on matters related to inclusion and diversity, thereby responding to increasing stakeholder demands.

In this regard, the characteristics of the board of directors play a fundamental role in ensuring compliance with diversity, inclusion, and personal development policies. This approach reinforces stakeholder trust in organizations operating in an increasingly demanding environment.

This research positions itself as a pioneering contribution in the field of corporate governance and corporate equality, addressing a dimension that has so far received little attention in the academic literature. Specifically, we explore how board characteristics influence corporate equality, focusing on diversity, inclusion, and personal development. While previous studies have analyzed these dimensions as separate constructs, our study goes further by investigating board characteristics as transformative factors in implementing diversity, inclusion, and personal development practices. Thus, the findings not only fill a gap in the existing literature but also provide a conceptual and practical framework for achieving greater organizational equity.

The results indicate that the presence of women on the board, the proportion of non-executive members, and the frequency of meetings positively influence corporate equality. Conversely, board tenure does not have a significant effect on corporate equality. Board size exerts a positive effect only on the personal development dimension, while cultural diversity shows a positive influence exclusively on the diversity dimension. Finally, board member compensation has a negative impact on corporate equality.

The literature review suggests that the presence of women on boards fosters a more inclusive organizational culture, as noted by

Gould et al. (

2018b) and

Kirsch and Wrohlich (

2020), who argue that women’s presence on boards enhances diversity policy initiatives, contributing to greater equality at both leadership and organizational levels. Similarly, evidence confirms that the participation of non-executive directors, who are generally more socially sensitive and responsive to stakeholder demands, also results in improvements in corporate equality (

Huse, 2005;

Konrad et al., 2008).

In contrast, the hypothesis regarding the influence of board tenure was not confirmed, which aligns with previous studies suggesting that institutions with long-serving board members may resist change and limit innovation in diversity policies (

Baum et al., 2000;

Levinthal & March, 1993). Likewise, board size exhibited a positive effect only on specific dimensions, such as personal development, suggesting that larger board structures may facilitate the implementation of employee development and training programs.

In Europe, regulatory reinforcement in non-financial disclosure enhances the traceability of D&I policies; however, there is a lack of plausible causal evidence at the board level. This study’s contributions are as follows: (i) European approach with a 2012–2023 panel, (ii) disaggregation by pillars (diversity, inclusion, development), (iii) systematic EF/EA contrast guided by Hausman and AIC/BIC, and (iv) map of actionable board levers for corporate policy. Against this backdrop, we pursue three objectives: (O1) to quantify how board gender diversity, independence, tenure, size, cultural diversity, meeting attendance, and compensation relate to overall corporate equality; (O2) to examine whether these associations differ across the diversity, inclusion, and personal development pillars; and (O3) to contextualize effects by firm attributes (size, age, internationalization). Accordingly, we test seven hypotheses (H1–H7) and address the following research question aligned with O1–O3: what is the relationship between the characteristics of the board of directors and corporate equality?

This study addresses a gap in the literature by extending research on board characteristics and examining the relationship between these characteristics and corporate equality among companies included in the Euro Stoxx 300 Index, a benchmark of major European corporations, thereby ensuring adequate representativeness. The period analyzed covers the years from 2012 to 2023, allowing us to study economic and financial dynamics over more than a decade, including the potential effects of significant events such as the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other relevant macroeconomic factors.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows to provide a structured and coherent analysis. First, we present a comprehensive literature review, serving as a theoretical basis to contextualize the study and justify the hypotheses. Next, we detail the research methodology, precisely describing the analytical techniques, data used, and statistical approach to ensure the validity and reliability of the results. Subsequently, we present the findings, accompanied by a detailed analysis of how they were obtained. Finally, the paper concludes with a critical discussion of the results, comparing them with previous research and outlining key conclusions, highlighting both their practical and academic relevance, as well as possible avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Diversity and inclusion have become a top priorities for many organizations, driven by an increasing emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion as key factors of sustainability and competitiveness. In this context, the board of directors plays a crucial role, as its characteristics and dynamics can directly influence organizational policies, strategies, and cultures related to equality.

This analysis aims to explore how the characteristics of the board of directors can promote or limit corporate equality, taking into account both the structural barriers and the opportunities that emerge in today’s business environment.

The following section presents a comprehensive review of the main theoretical and empirical findings related to these variables, thereby establishing the conceptual framework and the hypotheses that guide the analysis of this study.

2.1. Presence of Women on the Board of Directors

Many studies have analyzed the relationship between the presence of women on boards of directors and ESG practices, particularly within the social, environmental, and governance pillars (

Amorelli & García-Sánchez, 2023). However, less attention has been paid to the relationship between the proportion of women on boards and diversity, inclusion, and personal development within organizations (

Monteiro et al., 2022).

A relevant concept in this context is the “trickle-down effect,” which describes the process through which women in leadership positions positively influence female representation at lower hierarchical levels (

Gould et al., 2018a,

2018b). The appointment of women to executive positions acts as a catalyst for increasing the representation of women in subordinate roles, thereby achieving greater diversity within the company (

Gould et al., 2018a).

For this impact to be effective, women in leadership roles need to demonstrate both the desire and the ability to work on behalf of other women and to advocate for their interests (

Cohen & Huffman, 2007;

Gould et al., 2018a). In this regard,

Konrad et al. (

2008) found that nearly all the women directors they interviewed reported that they supported other women, either directly or indirectly, within their organizations. This included actions such as providing advice, engaging with women’s networks, requesting diversity reports, or developing programs aimed at fostering inclusion. These actions not only strengthen the professional development of women but also reinforce the collective responsibility of promoting gender equality.

In turn, the studies by

Kirsch and Wrohlich (

2020) found that many women in leadership roles aimed to raise awareness about gender equality, advocating for its inclusion on the organizational agenda. In fact, when the percentage of women on boards increases, it helps promote female leadership, reduce the gender pay gap, and draw greater attention to work–life balance (

Latura & Weeks, 2023). Moreover, they support women in advancing their careers through professional development policies, particularly when they are mothers (

Latura & Weeks, 2023).

In this context,

Latura and Weeks (

2023) emphasize that providing employees with childcare services to improve work–life balance encourages more women to seek executive positions. This may indicate that the presence of women on the board indirectly influences female leadership. Likewise, other solutions to improve work–life balance could include implementing flexible schedules, remote work, childcare subsidies, on-site childcare facilities, or additional allowances (

Latura & Weeks, 2023).

A recent survey conducted by

Cranet (

2023) shows that 23% of companies in Italy provide employees with workplace childcare services, a figure considerably higher than the European Union’s average of 9%.

These studies suggest that women in leadership roles not only directly advocate for female representation in executive positions but also support women at lower levels of the organizational hierarchy. This comprehensive approach fosters a more inclusive, equitable, and development-oriented organizational culture.

Complementarily, a direct relationship has been found between the presence of women on boards at the strategic level and the implementation of practices that foster diversity (

Srikant et al., 2021). Previous research supports this trend, indicating that women leaders are more likely to endorse and implement policies that promote female representation in leadership roles and enhance work–family balance. Overall, these findings suggest that boards of directors with higher female representation tend to promote greater inclusion (

Dobbin et al., 2011;

Glass & Cook, 2016;

Ingram & Simons, 1995).

Additionally, scholars such as

Glass et al. (

2016) argue that female executives demonstrate stronger initiative and promote diversity practices within organizations, thereby fostering greater overall organizational diversity.

Based on all the above, it seems reasonable to establish that a higher percentage of women on the board of directors exerts a stronger positive impact on corporate equality. For this reason, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. The presence of women on the board of directors positively influences corporate equality.

2.2. Proportion of Non-Executive Members

The proportion of non-executive members exerts a significant positive influence on inclusion, diversity, and employee development within the organization due to their independence, ethical focus, and lack of influence from personal interests.

On the one hand, according to stakeholder theory, originally developed by

Freeman and McVea (

2001), non-executive members are more committed to ensuring that social objectives are achieved, which leads companies to become more actively involved in initiatives related to diversity and inclusion. These members often face pressure to respond to stakeholders on social issues related to inclusion, personal development, and organizational diversity, as participation in such initiatives can enhance both their individual and corporate reputations (

Post et al., 2015).

Several studies have shown that boards with a higher proportion of non-executive directors tend to be more effective in developing and implementing inclusive policies. For example, research by

Nadeem (

2021) suggests that organizations with a greater number of non-executive directors are more likely to undertake social projects more regularly.

Similarly,

Ibrahim and Angelidis (

1995) found that social sensitivity within boards of directors is more pronounced in companies with a larger proportion of non-executive members, as these individuals are more likely to design and adopt ethical codes that include standards on equal opportunities, diversity, and inclusion. Additionally, as the proportion of non-executive members increases, so does the social pressure to meet the highest ethical and social standards, thereby promoting the creation of more inclusive organizational environments for employees.

In this way, the presence of non-executive board members is essential for the formulation and implementation of ethical codes within the organization, as well as for ensuring their broader diffusion and adoption, thereby helping to achieve minimum standards of diversity, inclusion, and employee development. This trend has been especially evident in the United States, Europe, and Canada (

Rodriguez-Dominguez et al., 2009).

Therefore, we argue that non-executive directors generally demonstrate greater social sensitivity and respond to stakeholder demands by promoting initiatives that enhance organizational diversity and strengthen inclusion. This, in turn, positively affects both the company’s reputation and its social and corporate performance. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2. The proportion of non-executive members on the board of directors positively influences corporate equality.

2.3. Tenure of Board Members

The tenure of board members exerts a significant influence on inclusion and employee personal development within organizations, a relationship that can be analyzed from various perspectives.

First, according to

Hambrick and Fukutomi (

1991), directors’ tenure can be divided into distinct phases over the course of their service on the board. These phases are characterized by different levels of attention, behavior, and ultimately by variations in organizational performance depending on the stage. Specifically, a director’s tenure can bring both strengths and weaknesses, depending on the phase of service they are experiencing (

Miller & Shamsie, 2001).

During the early stages of their tenure, directors are more likely to take risks and demonstrate greater initiative in acquiring new knowledge. As years progress, they expand their knowledge and skills, improving business strategies (

Wu et al., 2005). However, in the later stages of their tenure, directors tend to become more conservative, risk-averse, and less adaptable to changing environments (

Levinthal & March, 1993;

Miller, 1991) which can negatively affect overall organizational performance.

On the other hand, recent studies suggest that the influence of board member tenure is multifaceted and context-dependent (

Simsek, 2007;

Souder et al., 2012). According to

Luo et al. (

2014), directors’ tenure can positively affect the relationship between the company and its employees. The learning accumulated by directors through their board tenure enables them to better understand employees’ needs and limitations (

March, 1991).

Additionally, when board members actively engage in understanding their employees’ needs, employees tend to feel more valued by the organization, which in turn increases their confidence, motivation, and commitment. In this way, employees’ personal development is enhanced, as their job satisfaction rises, internal promotion opportunities increase, and career advancement is strengthened (

Hatch & Dyer, 2004;

Hitt et al., 2001).

Furthermore, as directors accumulate more years on the board, they tend to focus less on external information and more on the internal needs of the organization (

Levinthal & March, 1993). This implies that long-tenured directors primarily draw on resources and routines already established within the organization (

Baum et al., 2000), allowing them to obtain higher quality information directly from employees and to better identify inclusion and diversity needs in the workplace (

Barnett & Pontikes, 2008).

However, board member tenure can also lead to negative effects related to inclusion and diversity. One of the main challenges is resistance to change. As directors remain in their positions for longer periods, they become less receptive to new trends and social demands. This creates obstacles to the adoption of inclusive policies and limits the organization’s ability to innovate in inclusion practices (

Levinthal & March, 1993).

Similarly, familiarity with established routines can be beneficial, but it may reduce flexibility in implementing inclusive policies that promote a more diverse work environment. This can lead to stagnation, as directors focus on what they already know instead of adapting to new challenges and evolving social expectations (

Baum et al., 2000).

Based on the above, it is reasonable to conclude that longer board tenure may exert a stronger influence on corporate equality. For this reason, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3. The tenure of board members positively influences corporate equality.

2.4. Board Size

The scientific literature indicates that both overly small and excessively large boards entails significant disadvantages. On the one hand, a larger number of board members tends to increase diversity, which can enhance creativity and innovation within the organization (

Hillman et al., 2007). However, a large board can produce adverse effects, such as reducing the effectiveness of diversity due to a more rigid hierarchy and a broader distribution of power (

Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 2007;

Winter & Nelson, 1982). This reduction in autonomy among members (

Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 2007;

Papadakis, 2006), may ultimately weaken the positive impact of gender diversity on decision-making.

In contrast, organizations with smaller boards are often more likely to encourage creativity and positively affect diversity and inclusion (

Gong et al., 2013;

Hannan & Freeman, 1984;

Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000). These more compact structures allow for greater flexibility and a more direct emphasis on integrating diverse perspectives.

Bohnet et al. (

2016) argue that diversity challenges are exacerbated in large, homogeneous boards compared to smaller boards that exhibit a similar lack of heterogeneity. Likewise,

Rai et al. (

2024) contend that large, homogeneously composed boards often emerge from less diverse and inclusive selection processes. This not only perpetuates inequalities in representation but also increases resistance to integrating members from underrepresented groups compared with smaller boards.

Additionally, other studies support the idea that the number of directors on the board significantly influences workplace inclusion and diversity. With more members, there is a greater diversity of opinions and perspectives.

Post et al. (

2015) argue that boards with more directors tend to be more sensitive to social demands and, therefore, are more inclined to promote gender equality, cultural diversity, and workplace inclusion.

Similarly,

Nadeem (

2021) finds that a higher number of board members is associated with greater implementation of diversity and inclusion policies. According to

Konrad et al. (

2008), larger boards foster inclusion because they are better able to integrate employees’ social needs.

Based on the relationship between employees and the board,

Luo et al. (

2014) argue that a larger board are better able to empathize with employees and understand their needs, enabling the development of policies that support personal development and inclusion. Thus, large boards tend to enhance the representation of diverse interests.

Conversely, there are disadvantages associated with having a large number of directors on the board.

Souder et al. (

2012) warn that large boards may face difficulties in reaching agreements quickly and efficiently due to the greater diversity of opinions, which can hinder the implementation of inclusive policies.

In summary, board size influences inclusion, diversity, and personal development practices. However, for this relationship to be effective, there must be a clear commitment to inclusion and diversity within the organization. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4. Board size positively influences corporate equality.

2.5. Cultural Diversity on the Board

Cultural diversity refers to the ethnic and racial differences among members of the board of directors. While characteristics such as race and ethnicity are visible traits, similar to gender diversity, these variations also encompass less obvious traits, such as language, religion, values, norms, and beliefs.

After taking on the challenge of increasing gender diversity on boards, organizations are also committed to promoting cultural diversity in corporate governance. Due to persistent racial inequalities, many organizations are considering structural transformations that aim to enhance cultural diversity within their boards of directors (

Posner, 2020).

A study titled the “Black Corporate Directors Time Capsule Project” conducted by

Barry Lawon Williams (

2020) developed a 40-question survey targeting 50 Black directors to “capture their experiences,” with 74% of whom were men and 26% women. Over their careers, these directors served on a total of 274 corporate boards, and more than 60% had served on five or more boards. According to

Williams (

2020), nearly two-thirds of the directors reported that they had to address certain issues differently due to being Black, particularly regarding organizational diversity. Respondents agreed that their most important contribution was to promote diversity throughout the organization.

Other findings revealed that culturally diverse boards are more likely to promote diversity within the company and to appoint executives from different racial and ethnic backgrounds (

Williams, 2020). Additionally, the research indicated that boards with two or more directors from different cultures tend to demonstrate greater responsiveness due to their diverse perspectives and experiences, and that organizational diversity remained their primary priority, in contrast to boards that lacked cultural diversity (

Williams, 2020).

Furthermore,

Van Knippenberg et al. (

2004), note that cultural diversity encourages boards to be more creative and innovative, which can lead to the implementation of more inclusive policies that take into account for differences among employees.

When directors come from different cultures, they are better equipped to foster a work environment where diversity is valued and respected. In this context,

Ely and Thomas (

2001) argue that culturally diverse boards are more likely to create an environment in which employees feel respected and valued, as these directors are deeply committed to promoting inclusion and diversity within the organization.

Achieving organizational diversity and inclusion also sets an example for employees, reinforcing the perception of equal opportunities. According to

Singh (

2008), employees feel more included when they see that the organization is committed to these values and that such principles are prioritized at the highest levels of management.

Moreover,

Montoya et al. (

2021) argue that multiracial groups exhibit greater resilience. This suggests that having a culturally diverse board can provide benefits when facing challenging situations. This resilience is further supported by

Bowman (

2010), who argues that developing cognitive skills fosters critical thinking, implying that a diverse board can help cultivate an inclusive mindset among other members of the organization.

Despite the benefits, cultural diversity on boards can also create communication challenges and potential problems for the organization.

Stahl et al. (

2010) note that if not well managed, cultural differences can lead to conflicts of ideas, resulting in inefficient decision-making and poorly implemented diversity and inclusion policies. However, these challenges can be mitigated through strong governance and effective communication among board members.

Based on this, the study anticipates a positive relationship between cultural diversity within the board and corporate equality. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5. Cultural diversity on the board of directors positively influences corporate equality.

2.6. Frequency of Board Meetings

The frequency of board meetings serves as an important indicator for evaluating the level of activity and operational commitment of this governing body (

Laksmana, 2008).

For the board of directors to efficiently address organizational challenges and meet the demands of stakeholders, directors often need to restructure both the topics discussed and frequency of board meetings. This restructuring aims to achieve greater organizational diversity and inclusion, fostered by a wider range of knowledge, skills, and experiences brought to board discussions (

Forbes & Milliken, 1999;

Milliken & Martins, 1996).

According to

Machold et al. (

2011) and

Zhang (

2010), the leadership ability of the board chair is crucial for ensuring director participation in meetings and facilitating their contributions to achieving corporate objectives. Moreover, scholars such as

Kanadlı et al. (

2018) argue that the chair’s leadership contributes to greater representation of minorities, who are often marginalized in board meetings as explained by social categorization theory (

Zhu, 2014). Allowing minorities the opportunity to express their opinions freely and on equal terms with majority directors, is considered a key element for reducing biases and achieving organizational equality and inclusion (

A. Kakabadse et al., 2018;

N. K. Kakabadse et al., 2015). Therefore, the board chair plays a central role in motivating active participation and in promoting a higher frequency of board meetings (

Gabrielsson et al., 2007).

Additionally, the participation and frequency of board members in meetings lead to deeper discussion and greater prioritization of inclusion and diversity issues.

Forbes and Milliken (

1999) emphasize that the ability to address diversity and inclusion challenges depends largely on the effectiveness of board meetings.

Carter et al. (

2003) suggest that higher meeting frequency promotes an organizational culture that values diversity as a strategic priority. By repeatedly addressing diversity and inclusion matters, board members are more likely to implement policies that integrate underrepresented groups within the organization.

Furthermore, board members’ commitment to attending meetings not only promotes inclusion and diversity but also enhances employees’ professional development in the workplace.

Huse (

2005) highlight that meetings focused on human capital facilitate the implementation of training programs, mentorships, and promotion opportunities. These programs not only increase job satisfaction but also improve employees’ career prospects.

In line with the above, it can be argued that greater frequency of board meetings promotes inclusion, diversity, and workplace development by addressing these issues more consistently as a result of higher levels of attendance.

Based on this, the study posits that board meeting attendance exerts a positive influence on corporate equality. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6. The frequency of board meetings positively influences corporate equality.

2.7. Board Member Compensation

Board member compensation typically comprises four distinct elements. First, they receive a fixed allowance comparable to that of directors in other companies. Second, they have access to a performance-linked incentive system, which includes both immediate and deferred rewards based on objectives such as financial performance. Third, they are offered the option to purchase shares under preferential conditions. Finally, their compensation package includes benefits derived from restricted stock plans and special retirement schemes (

Murphy, 1998).

Linking compensation to equality, diversity, and personal development in the workplace can be an effective way to attract the attention of stakeholders, as it demonstrates the company’s commitment to achieving corporate equity, fairness, and equality (

Roy, 2023).

One measure to reduce inequality within an organization, particularly income inequality, is to increase employee participation in decisions regarding board member compensation (

Lin et al., 2024).

According to

Lin et al. (

2024), employee involvement in setting compensation encourages more extensive negotiation between directors and employees, thereby helping to reduce wage disparities within the company.

Currently, it is estimated that approximately 27% of S&P 500 companies link board member compensation to inclusion, diversity, and personal development objectives (

Mercer, 2021).

The proportion of compensation linked to these three pillars typically ranges between from 10% to 20% in many companies, which seems to be a balanced amount to promote equality, diversity, and personal development. However, a proportion below 5% is generally considered insufficient to achieve meaningful change (

Roy, 2023).

However, a study by

Leslie et al. (

2017) found that some companies overcompensate female executives in an effort to increase the proportion of women on boards and meet diversity, inclusion, and personal development targets, while inequality continues to persists in other positions.

Moreover, board member compensation directly affects directors’ motivation to steer company strategies toward inclusion and diversity objectives. When compensation is contingent upon organizational outcomes, directors are more likely to exert effort to meet these goals (

Boyd, 1994).

In this regard,

Devers et al. (

2007) agree that clearly defined incentives drive boards toward more inclusive management, leading to the implementation of policies that increase diversity at senior levels and foster employee development in the workplace.

Furthermore, adequate and competitive board compensation help attract directors with strong experience and high qualifications in talent and organizational diversity management. In this way, an appropriate compensation structure acts as a lever for aligning board strategic decisions with employee needs, strengthening workforce professional development (

Brick et al., 2006).

In contrast, a thorough review of the literature suggests that board compensation may not directly affect employee diversity, inclusion, and development, since other, more complex factors may influence these outcomes.

First, board compensation typically depends on financial performance objectives, not necessarily on social goals such as inclusion or organizational diversity (

Bebchuk & Fried, 2004).

Additionally, inclusion, diversity, and personal development in the workplace are often related to intangible aspects of organizational culture, human resource management, and stakeholder objectives.

Aguilera et al. (

2007) argue that inclusion and diversity policies are motivated by a combination of social and cultural norms as part of an ethical commitment, rather than by board compensation.

It is also important to note that the relationship between compensation structure and the existence of diversity, inclusion, and personal development appears to be more incidental than causal. Outcomes in diversity and inclusion primarily derive from the board’s internal strategies rather than from financial incentives. For this reason,

Post et al. (

2015) argue that the board’s social interests and ethical commitment are more decisive determinants than board members’ pay structures.

In conclusion, while board compensation may influence the company’s strategic performance, it does not appear to have a significant impact on inclusion, diversity, and personal development. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7. Board member compensation does not positively influence corporate equality.

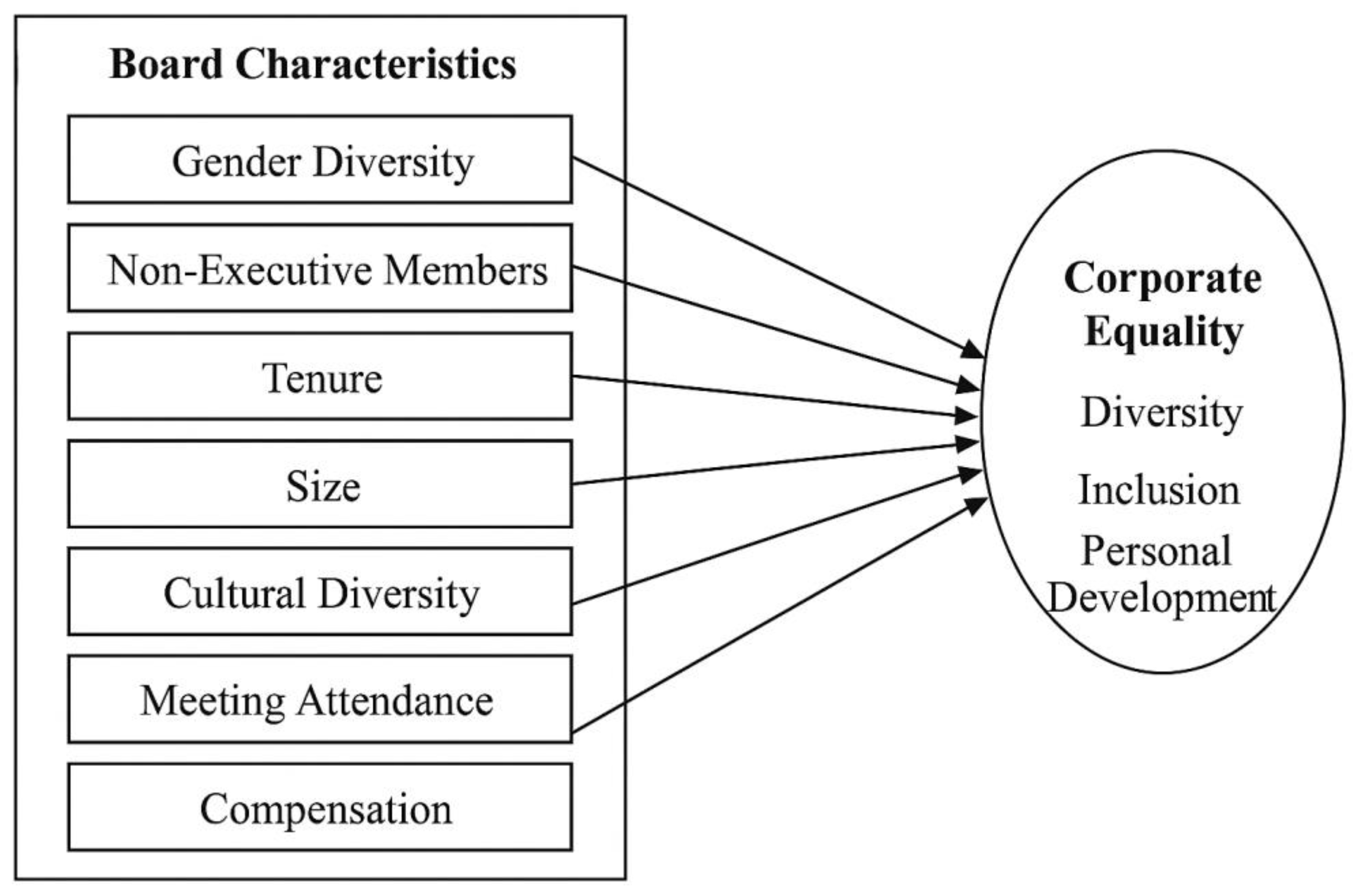

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework developed in this study, which summarizes the hypothesized relationships among board characteristics and corporate equality. The model proposes that seven board characteristics (gender diversity, proportion of non-executive members, tenure, board size, cultural diversity, meeting attendance, and compensation) influence corporate equality, conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing diversity, inclusion, and personal development.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the main descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study. Regarding the dependent variables analyzed, the overall TRDIR score (TRDIRSC) has a mean of 59.68 and a median of 59.5, reflecting a moderate assessment. The standard deviation of 8.02 indicates moderate variability, with values ranging from 32 to 82.75.

The diversity score (TRDIRDSC) has an average of 44.07 and a median of 45, suggesting relatively lower performance in this dimension. However, the wide standard deviation of 13.31 and the range from 0 to 79 indicate considerable dispersion in diversity among the companies analyzed.

For the inclusion score (TRDIRINSC), the mean is 32.57 and the median is 31, making inclusion the weakest-performing dimension, which could indicate an area for improvement. The high standard deviation of 23.63 and the full range from 0 to 100 reflect significant variability in inclusion practices.

Finally, the personal development score (TRDIRPDSC) has a mean of 54.44 and a median of 56, showing an intermediate assessment compared to the other dimensions. The standard deviation of 15.29 and the range of 0 to 94 highlight a wide dispersion in personal development practices among companies.

Regarding board characteristics, board gender diversity (BGD) averages 31.34% with a median of 33.33%. There is notable variability, as some boards have no female representation, while others reach up to 66.67%.

The average proportion of non-executive members on boards (NEM) is 89.67%, with a median of 92.86%, indicating a strong tendency toward independence. Some boards are fully independent, with 100% non-executive composition.

The average tenure of board members (TBM) is 3.51 years, with a median of 4 years, indicating moderate stability and turnover, with values ranging from 1 to 12 years. Board size (BSZ) averages 12.54 members, with a median of 12 and a range of 3 to 30 members, showing significant variability in board composition.

Regarding board cultural diversity (BCD), the mean is 31.53% and the median is 23.53%, suggesting that while some boards reach 100% cultural diversity, others have minimal representation.

Average board meeting attendance (BMA) is 94.95%, with a median of 97%, reflecting high commitment from board members. In some cases, attendance reaches 100%, demonstrating notable engagement.

Finally, the average board member compensation (BCO) shows limited variation among the companies analyzed, indicating a relatively homogeneous compensation structure across firms.

Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation matrix between the explanatory variables and the dependent variables used to analyze corporate equality in companies.

Regarding the overall TRDIR score (TRDIRSC), all variables show significant correlations except for NEM, TBM, and BCD, providing preliminary evidence of linear associations among the variables.

For diversity (TRDIRDSC), the strongest correlations are observed with BGD, BSZ, BCD, BCO, LSA, and EMP. These significant suggest that these factors are strongly linked to the diversity dimension of corporate equality.

In the case of inclusion (TRDIRINSC), significant correlations are found with NEM, TBM, BSZ, BCO, LSA, and EMP. Conversely, negative correlations, such as those with BCD and MTB, reveal opposite association patterns, suggesting potential trade-offs in how these factors relate to inclusion practices.

Finally, for personal development (TRDIRPDSC), significant correlations are observed with BGD, BSZ, LSA, and EMP. Weaker negative relationships with variables such as MTB and TBM are also noted, indicating less stable association patterns within this dimension.

Table 4 presents the Pearson correlation matrix among the explanatory variables. The results indicate that there are no high correlations among these variables. Therefore, the results suggest the absence of severe multicollinearity in the regression models.

Moreover, to ensure the absence of collinearity issues within the set of variables employed, a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis was conducted. The results reported in

Table 5 indicate that there are no significant collinearity concerns among this set of variables. All VIF values are below the commonly accepted threshold of 5 (

Craney & Surles, 2002), suggesting that multicollinearity is unlikely to materially affect the estimation and interpretation of the specified models.

After confirming the absence of multicollinearity problems, the influence of board characteristics on the corporate equality practices implemented by companies is analyzed.

First, the effect on the TRDIRSC variable is examined. The results in

Table 6 show three models: an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model, a fixed-effects model, and a random-effects model. All three models were found to be statistically adequate based on the F-statistic (

Santos-Jaén et al., 2023). Based on the Hausman test results (

p-value < 0.05), Model 3 (random effects) is rejected in favor of Model 2 (fixed effects) (

Valls Martínez et al., 2023). Furthermore, according to the Akaike Information Criterion (

Akaike, 1974) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (

Schwarz, 1978), where lower values indicate a better model, the most appropriate model is Model 2, the fixed-effects model.

The fixed-effects model results show how some corporate governance variables influence corporate equality in companies. Gender diversity on the board (BGD) has a positive coefficient of 0.111 and is highly significant, suggesting that an increase in gender diversity is associated with an increase in TRDIRSC. The proportion of non-executive members (NEM) also shows a positive coefficient of 0.109. On the other hand, the variable capturing board member compensation (BCO) shows a negative and significant effect of −0.884, also highly significant, suggesting that higher compensation is associated with lower equality practices in companies. The remaining board-related variables do not show any significant influence. Regarding financial variables, only assets (ASS) show a positive and highly significant effect of 0.771.

In this fixed-effects model, the coefficient of determination (R

2) indicates that 31.43% of the variance in the TRDIRSC variable is explained by the model. Therefore, it can be accepted that this model exhibits an acceptable explanatory power (

Hair et al., 1998).

Once the TRDIRSC variable, which reflects a global corporate equality index, was analyzed, the focus shifted to the indices capturing its three specific components: diversity (TRDIRDSC), inclusion (TRDIRINSC), and people development (TRDIRPDSC).

Starting with corporate equality regarding diversity within the company, the results in

Table 7 present three models analyzing the TRDIRDSC variable. As in the previous case, an OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) regression model, a fixed-effects model, and a random-effects model were proposed. All three models were found to be statistically adequate based on the F-statistic (

Santos-Jaén et al., 2023). Based on the Hausman test results (

p-value < 0.05), Model 6 (random effects) was rejected in favor of Model 5 (fixed effects) (

Valls Martínez et al., 2023). Additionally, according to the Akaike (

Akaike, 1974) and Bayesian (

Schwarz, 1978) information criteria, where lower values indicate a better model, the Fixed Effects Model 5 was identified as the most appropriate.

The results of this fixed-effects model show that gender diversity on the board (BGD) has a positive coefficient of 0.410 and is highly significant, suggesting that an increase in gender diversity is associated with an increase in the dependent variable. The proportion of non-executive board members (NEM) also shows a positive coefficient of 0.286 and is highly significant, indicating that a higher percentage of non-executive members on the board is associated with better outcomes for TRDIRDSC. Furthermore, the results show that cultural diversity (BCD) positively and significantly influences diversity-related equality with a coefficient of 0.062. Regarding financial variables, only assets (ASS) show a positive influence of 3.211 and are highly significant.

In this fixed-effects model, the coefficient of determination (R

2) indicates that 27.7% of the variance in the TRDIRDSC variable is explained by the model. Therefore, this specification can be considered to exhibit an acceptable explanatory power (

Hair et al., 1998).

Next, the analysis is repeated, this time focusing on the variable that measures corporate equality from the perspective of employee development (TRDIRPDSC). The results in

Table 8 present three models analyzing this variable. As in previous analyses, an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model, a fixed effects model, and a random effects model were estimated. All three models were found to be statistically adequate based on the F-statistic (

Santos-Jaén et al., 2023). According to the Hausman test results (

p-value > 0.05), Model 8 (fixed effects) was rejected in favor of Model 9 (random effects) (

Valls Martínez et al., 2023). Additionally, using the Akaike (AIC) (

Akaike, 1974) and Bayesian (

Schwarz, 1978) (BIC) Information Criteria, where lower values indicate a better model, Model 9 of random effects was identified as the most appropriate.

The results of this random effects model show that the proportion of non-executive members (NEM) has a positive and significant coefficient of 0.151, indicating that a higher percentage of non-executive members on the board is associated with better outcomes in the variable analyzed. Similarly, the board size (BSZ) has a positive and significant effect, with a coefficient of 0.554. This positive effect is also observed for board meeting attendance (BMA), with a coefficient of 0.313. Conversely, cultural diversity on the board (BCD) shows a negative effect, with a coefficient of −0.044, on the variable reflecting inclusion within the company.

Regarding financial variables, sales (LSA), sales (LVA), and the market-to-book ratio (MTB) show a significant influence on corporate equality as measured from the perspective of employee development. Assets (ASS) also exert a positive and significant effect.

In this random effects model, the R

2 coefficient indicates that 23.32% of the variance in TRDIRPDSC is explained by the model, representing an acceptable explanatory power (

Falk & Miller, 1992;

Hair et al., 1998).

Finally, the analysis is conducted on the variable capturing the inclusion of people within companies (TRDIRINSC). The results in

Table 9 present three models analyzing this dependent variable. As in previous analyses, an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model, a fixed-effects model, and a random-effects model were proposed. All three models were found to be statistically adequate based on the F-statistic (

Santos-Jaén et al., 2023). According to the Hausman test results (

p-value > 0.05), Model 11 (random effects) was rejected in favor of Model 12 (random effects) (

Valls Martínez et al., 2023). Additionally, based on the Akaike Information Criterion (

Akaike, 1974) and Bayesian Information Criterion (

Schwarz, 1978), in which lower values indicate a better model, the Model 12 with random effects was identified as the most appropriate.

The results of this random-effects model show that gender diversity on the board (BGD) has a positive coefficient of 0.129 and is highly significant, suggesting that an increase in gender diversity is associated with a rise in the TRDIRINSC variable. The proportion of non-executive members (NEM) also shows a positive coefficient of 0.134 and is highly significant, indicating that a higher percentage of non-executive board members is associated with better outcomes in TRDIRINSC. Finally, board meeting attendance (BMA) has a positive coefficient of 0.139 and is significant, implying that higher attendance at meetings is positively associated with TRDIRINSC.

Regarding financial variables, results show a positive and highly significant influence of sales (LSA), leverage (IND), and employees (EMP).

In this random-effects model, the R

2 coefficient indicates that 26.1% of the variance in TRDIRINSC is explained by the model, representing a weak but acceptable explanatory power (

Falk & Miller, 1992;

Hair et al., 1998).

Diagnostic tests were conducted for all the estimated models to ensure the robustness of the results. The Breusch–Pagan test and the Wooldridge test indicated no evidence of heteroskedasticity or serial correlation in any of the models (

p > 0.05). In addition, the Durbin–Watson statistics ranged between 1.7 and 2.3 across specifications, suggesting the absence of first-order autocorrelation and confirming model stability. Taken together, these results confirm that the estimations are reliable and internally consistent for all the regression models presented above (

Wooldridge, 2010).

Table 10 presents a detailed analysis of the influence of the independent variables on the dependent variables, as well as the results related to the hypotheses proposed in this study. The results indicate that certain characteristics of the board of directors have a significant impact on scores related to corporate equality.

The findings show that three board characteristics—gender diversity (BGD), the proportion of non-executive members (NEM), and board meeting attendance (BMA)—have a positive and significant effect on the general index (TRDIR), diversity (TRDIRDSC), and inclusion (TRDIRINSC) scores. This supports hypotheses H1, H2, and H6, underscoring the importance of these variables in promoting policies related to diversity and inclusion within corporate governance.

On the other hand, board member tenure (TBM) does not show a significant effect on any of the analyzed corporate equality variables, leading to the rejection of hypothesis H3. Board size (BSZ) only shows a positive impact on the variables related to people development (TRDIRPDSC), which is insufficient to support hypothesis H4, resulting in its rejection.

Regarding board cultural diversity (BCD), a positive effect is observed on diversity (TRDIRDSC) and a negative effect on people development (TRDIRPDSC), leading to the rejection of hypothesis H5. Finally, board member compensation (BCO), although showing a negative effect only on the global corporate equality variable, supports hypothesis H7.

In summary, the econometric results show that the choice between fixed-effects (FE) and random-effects (RE) models varies according to the nature of the dependent variable analyzed. In the case of the overall corporate equality index (TRDIRSC) and the diversity dimension (TRDIRDSC), the Hausman test indicated that FE models were the more appropriate, as they better capture firm-specific heterogeneity and provide robust estimates. Conversely, for the dimensions of personal development (TRDIRPDSC) and inclusion (TRDIRINSC), the RE models offered a more efficient specification, as the Hausman test did not reject the null hypothesis of no systematic differences between RE and FE. This combined use of FE and RE models ensures that the estimations are both statistically consistent and efficient, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of the findings across the different dimensions of corporate equality.

5. Discussion

An analysis has been conducted on how board characteristics influence corporate equality using a sample of companies included in the Euro Stoxx 300 index, a benchmark of leading European firms, for the years 2012 to 2023. This study confirms a positive and significant effect of gender diversity on corporate equality. The presence of women on boards improves scores for the overall corporate equality index as well as in the pillars of diversity and inclusion. These results align with research by (

Gould et al., 2018a),

Konrad et al. (

2008),

Kirsch and Wrohlich (

2020),

Latura and Weeks (

2023) and

Glass et al. (

2016), who argue that female executives show greater initiative and promote diversity practices within organizations, driving greater organizational diversity. When analyzing data from countries with similar socio-political contexts (such as OECD countries, Europe, or North America), corporate culture and norms are likely to influence outcomes in a similar way. These studies suggest that women not only advocate directly for female representation in executive roles but also support women at lower hierarchical levels. This comprehensive approach fosters a more inclusive, equitable, and development-oriented organizational culture.

A positive and significant relationship is also confirmed between independent board members and corporate equality. Independent directors are more likely to ensure that social objectives are met, leading the company to engage more in initiatives related to diversity and inclusion. These findings are consistent with research by

Nadeem (

2021),

Phillips-Wren (

2018), and

Shohaieb et al. (

2022), who note that independent directors are more prone to develop ethical codes that include standards on equal opportunity, diversity, and inclusion. This tendency has been particularly evident in the United States, Europe, and Canada (

Rodriguez-Dominguez et al., 2009).

Regarding the impact of board tenure on corporate equality, results show no significant effect on any of the analyzed equality variables, leading to the rejection of Hypothesis H3. These findings are consistent with studies by (

Baum et al., 2000) and (

Levinthal & March, 1993) which indicate that board tenure can be an obstacle to adopting inclusive and diversity policies due to resistance to change and familiarity with established routines, reducing flexibility in policy implementation. In contrast, they differ from studies by

Luo et al. (

2014) which argue that learning acquired by directors through board tenure helps them better understand employees’ needs and constraints. This discrepancy may be explained by temporal and regional contexts:

Luo et al. (

2014) focused on publicly traded U.S. companies between 2000 and 2010, whereas

Baum et al. (

2000) studied Canadian firms from 1971 to 1996, highlighting more traditional environments that hinder innovation in diversity and inclusion policies among longer-tenured members.

Similarly, regarding board size, it only shows a positive impact on variables related to personnel development. This aligns with

Luo et al. (

2014) who argue that a larger number of directors improves the board’s capacity to understand employees’ needs, enabling policies that foster personal development and inclusion. However, the findings contradict research such as

Souder et al. (

2012) which warns that large boards may struggle to reach quick and effective consensus due to the number of opinions, complicating the implementation of inclusive policies. The difference could be attributed to the fact that large boards face greater coordination challenges in the European context, where firms must respond quickly to regulatory demands on inclusion and diversity.

Regarding board cultural diversity, results show a positive impact on diversity, consistent with (

Williams, 2020),

Van Knippenberg et al. (

2004),

Montoya et al. (

2021) and

Bowman (

2010), who emphasize that boards with two or more directors from different cultural backgrounds have greater responsiveness due to diverse perspectives and experiences, and prioritize diversity within the company compared to boards lacking cultural diversity. Additionally, directors from different cultures are better equipped to foster a work environment that values and respects diversity. However, board cultural diversity shows a negative impact on personnel development, which aligns with studies like

Stahl et al. (

2010), indicating that without effective management, cultural differences can lead to idea conflicts and inefficient decision-making, resulting in inadequate diversity and inclusion policies.

When examining board meeting attendance, results show a positive and significant effect on the overall index, diversity, and inclusion. This aligns with studies by

Forbes and Milliken (

1999) and

Carter et al. (

2003), suggesting that higher attendance promotes an organizational culture that values diversity as a strategic priority. Regularly addressing diversity and inclusion topics encourages board members to implement policies integrating underrepresented groups into the organization.

Finally, the study finds that board member compensation only has a negative effect on the overall corporate equality variable. This is consistent with

Bebchuk and Fried (

2004),

Aguilera et al. (

2007), and

Post et al. (

2015), who argue that board compensation is typically tied to financial objectives rather than social goals such as inclusion or organizational diversity. Inclusion and diversity policies are often driven by a combination of social and cultural norms as part of an ethical commitment rather than by board member compensation. However, these findings differ from

Devers et al. (

2007) and

Brick et al. (

2006), who found a positive relationship, arguing that clear and well-defined incentives push boards toward more inclusive management, implementing policies that increase diversity at senior levels and foster employee development. The discrepancy may be due to the European context, where compensation is more regulated and tied to predefined criteria, limiting its impact on strategic board behavior.

The effects vary depending on the type of company and do not follow a ‘straight line’ relationship. Additional analyses show that they are stronger in large companies with a more international presence; furthermore, when the board is very large or very culturally diverse, the benefits stagnate or diminish. It is consistent with the fact that coordinating more people makes work more expensive and complicated, and that great diversity can lead to the formation of subgroups. It is therefore advisable to set board composition targets tailored to the size and international profile of each company.

6. Conclusions

This section consolidates the study’s contributions by distinguishing between theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and avenues for future research, thereby enhancing the readability and traceability of the main takeaways.

6.1. Summary of Findings

Despite the growing interest in how companies manage diversity, inclusion, and employee personal development, the existing literature is very limited (

Shohaieb et al., 2022). Implementing policies to achieve diversity, inclusion, and personal development goals can improve corporate strategies and policies, so understanding the factors that positively or negatively influence them is crucial (

Maj, 2018;

Shimeld et al., 2017). However, existing literature on this topic is very limited (

Monteiro et al., 2021). To address this gap, this study examines how corporate governance characteristics including gender diversity, independence, tenure, board size, cultural diversity, attendance at meetings, and compensation of board members influence corporate equality.

Using a sample of companies included in the Euro Stoxx 300 index, a benchmark of leading European companies, for the years 2012 to 2023, this study demonstrates how the characteristics of the board of directors influence corporate equality.

This study contributes to the academic literature by analyzing in depth how board characteristics, such as gender diversity, tenure, independence, size, cultural diversity, attendance at board meetings, and board member compensation, influence corporate equality in leading European companies of the Euro Stoxx 300 index. Through a longitudinal approach (2012–2023) and robust methodology, the study reveals specific relationships that have been little explored, such as the impact of tenure and cultural diversity on diversity and inclusion, as well as the relevance of attendance at meetings and the independent composition of the board. In addition, it provides a European contextual framework that reflects how local regulations and demands shape the effectiveness of these practices, enriching the academic debate on diversity, inclusion, employee personal development, and corporate governance.

Our research offers several key conclusions. First, gender diversity on boards positively influences corporate equality. The literature review suggests that women not only directly advocate for female representation in executive positions but also support women at lower levels of the organizational hierarchy. This comprehensive approach fosters a more inclusive, equitable, and development-oriented organizational culture, achieved through initiatives such as providing childcare services for employees to improve work–life balance, implementing flexible schedules, remote work, and childcare subsidies.

Second, the presence of non-executive directors exerts a positive influence on corporate equality, as independent board members display greater social sensitivity and responsiveness to stakeholder demands, leading to the implementation of diversity and inclusion projects that enhance both corporate reputation and social performance.

Third, board tenure shows a negative relationship with corporate equality. Longer-serving directors may become resistant to change and less responsive to emerging social trends, which can hinder the adoption of inclusion policies and reduce innovation in equality management.

Fourth, board size has a positive effect on personal development practices. Larger boards incorporate a greater diversity of perspectives and expertise, enabling more effective decision-making on employee development and inclusion policies.

Fifth, cultural diversity among board members enhances corporate diversity but can hinder employee development when not properly managed. While culturally diverse boards bring valuable perspectives and sensitivity to social issues, ineffective coordination can lead to conflict and slow decision-making, reducing the effectiveness of inclusion policies.

Sixth, board meeting attendance positively affects corporate equality, as greater participation reflects stronger commitment to diversity and inclusion. Regular discussions of these topics promote concrete policies to integrate underrepresented groups within organizations.

Finally, board member compensation shows a negative association with corporate equality. Since compensation is generally tied to financial rather than social objectives, it does not effectively incentivize inclusion and diversity initiatives. Equality-related policies tend instead to emerge from ethical and cultural commitments rather than monetary rewards.

Moreover, this research adopts a longitudinal perspective (2012–2023) that captures both cross-sectional and temporal variations in board characteristics and equality practices. This time frame encompasses periods of significant disruption—such as the post-2008 financial recovery and the COVID-19 pandemic—that influenced corporate governance priorities across Europe. Although no time dummies were included, these contextual effects are indirectly captured through the panel structure. Firm-level heterogeneity, such as company size, age, and degree of internationalization, may also condition the magnitude of these relationships. Larger and more mature firms tend to exhibit more institutionalized equality and inclusion practices, whereas smaller or younger firms may respond more reactively to regulatory and social pressures. These contextual insights help interpret the variability in the findings and provide valuable guidance for future research.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

The findings obtained have important theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical point of view, this study advances the understanding of the relationship between the board of directors and corporate equality, providing evidence of how different board characteristics influence diversity, inclusion, and personal development in the organization. Although board characteristics have been widely studied in recent years, most researchers have addressed the impact of board structure on ESG practices and corporate social responsibility. However, there is a gap in the literature on how these characteristics influence workforce diversity, equality, and personal development. Therefore, this study represents a significant contribution to current literature by addressing a gap in this field. By conducting this exhaustive research, we have identified and analyzed aspects that had previously been overlooked, enriching the field with original and relevant findings.

6.3. Practial Implications

The practical implications that emerge from analyzing the influence of corporate governance on promoting equality, inclusion, and personal development in organizations constitute an essential guide for effectively implementing socially responsible policies.

First, increasing the presence of women on boards should be a priority. According to

Gould et al. (

2018a) and

Konrad et al. (

2008), female representation on boards acts as a catalyst for inclusive initiatives, promoting an organizational culture that values equity and fosters female representation at all hierarchical levels. Therefore, companies can set clear and measurable goals to increase female participation in leadership roles through quota policies or specific mentorship programs, promoting equal opportunities and professional development for women (

Latura & Weeks, 2023).

Second, the autonomy and independence of board members should be strengthened as a mechanism to ensure objectivity and rigor in overseeing equality-related practices. As

Huse (

2005) suggest, the presence of non-executive directors, free from conflicts of interest, facilitates decisions that prioritize diversity and inclusion, in addition to promoting social audits and corporate social responsibility programs that enhance an inclusive culture within the organization. Therefore, companies should establish policies that foster board independence and promote periodic evaluations of its performance in labor equality.

Third, promoting greater participation in board meetings is essential to maintain sustained commitment to diversity and inclusion policies.

Aguilera et al. (

2007) emphasize that high attendance and participation in meetings allow discussion of essential topics related to equality and personal development, facilitating the design and implementation of effective programs in these areas. Consequently, organizations should establish monitoring mechanisms for effective participation, such as structured agendas, diversity and inclusion training, and incentive systems that recognize board member engagement.

Likewise, board size and cultural diversity should be strategically considered.

Monteiro et al. (

2021) suggest that larger and multicultural boards provide varied perspectives that enrich decision-making in equality and development policies. Therefore, companies could periodically review board composition, seeking to balance the number of members and promote a culture of respect and appreciation for cultural diversity, thereby fostering an inclusive environment that positively impacts internal policies.

Finally, the management of compensation policies should align with equality and personal development objectives.

Aguilera et al. (

2007) warn that remuneration systems should promote ethical and motivating practices that incentivize behaviors aligned with an inclusive culture. Consequently, companies can design incentive schemes that recognize and reward commitment to diversity policy, participation in inclusion training, and implementation of initiatives that foster employee personal and professional development.

Beyond firm-level actions, the practical implications of this article for companies are to set thresholds for gender diversity and for the proportion of non-executive directors, ensure disciplined meeting practices with a published calendar, quorum targets and attendance records, and implement internal metrics with trackable objectives for inclusion and people development; for regulators, they entail aligning codes of corporate governance with diversity and inclusion goals, standardising the traceability and disclosure of board and committee attendance and agendas, requiring a consistent set of KPIs with external assurance, and promoting remuneration alignment with social objectives; and for investors, they involve integrating signals from board composition and processes into voting policies and equality-oriented engagement strategies, requiring KPIs and plans with milestones and accountable owners, and setting thresholds for action and escalation in cases of persistent non-compliance.

6.4. Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the sample is restricted to companies included in the Euro Stoxx 300 Index, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to non-European or smaller firms. Second, the analysis relies on secondary data from the Refinitiv Eikon database, which, although standardized, may not capture qualitative dimensions of equality practices. Third, the empirical design focuses exclusively on linear relationships, without exploring possible non-linear or interaction effects among governance variables. These more complex relationships could reveal threshold effects or diminishing returns in how board characteristics influence corporate equality.

Finally, the analysis does not account for sector-specific differences in diversity and inclusion dynamics, which could affect the results.

6.5. Future Research Directions

Future studies could address these limitations in several ways. Cross-country comparative research, including firms from different institutional contexts such as North America, Asia, or Latin America, would enrich understanding of how cultural and legal frameworks condition the governance–equality nexus.

Moreover, qualitative approaches, such as interviews or content analysis of sustainability reports, could provide deeper insights into how boards internalize equality and inclusion principles.

In addition, exploring non-linear models and moderating effects (e.g., industry, ownership structure, or corporate culture) would help identify boundary conditions and intensity thresholds in the relationship between board characteristics and equality outcomes.

Finally, integrating emerging topics, such as artificial intelligence in board decision-making or gender-inclusive digital governance, could open new research avenues in the evolving field of equality-driven corporate governance.