Abstract

Despite growing scholarly interest in leadership within entrepreneurial settings, little is known about how relational leadership operates in informal, resource-constrained ecosystems. This study examines how entrepreneurial leadership fosters positive relational dynamics and collaborative resilience within Ecuador’s highly informal entrepreneurial ecosystem. Drawing on entrepreneurial cognition and relational leadership theories, it investigates how entrepreneurs act as informal leaders who cultivate trust, empathy, and mutual support in the absence of formal institutional structures. Using an original mixed-method lexical–clustering design, data were collected from 880 micro and small entrepreneurs in Quito, who categorized 75 entrepreneurial attributes using a forced-choice instrument. Two dominant narratives emerged: collaborative resilience (65%), defined by empathy, adaptability, and social cohesion, and structural vulnerability (35%), marked by bureaucracy, fear, and emotional strain. Gender differences revealed that women emphasize relational stress and communal coping, while men focus on structural barriers and operational constraints. The findings extend leadership research by demonstrating how positive relational processes enable entrepreneurs to transform adversity into collective strength. The study advances relational leadership theory by revealing its cognitive and emotional foundations in nontraditional contexts. It offers policy insights for designing inclusive, trust-based ecosystems that promote psychological safety, collaboration, and sustainable entrepreneurship in emerging economies.

1. Introduction

Comprehending the cognitive frameworks that entrepreneurs hold about entrepreneurship is essential, as these mental models shape intentions, decision-making, and ultimately the collective trajectory of economic ecosystems. Perceptions act as lenses through which opportunities are identified, risks assessed, and resources mobilized—processes that determine the survival, innovation, and scalability of ventures (; ; ). At the macro level, entrepreneurial mindsets foster job creation, market diversification, and social resilience, particularly in developing economies, where micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) underpin both employment and informal-sector activity.

Understanding these subjective interpretations is therefore critical for designing context-sensitive policies that facilitate transitions from subsistence to opportunity-driven ventures. At the same time, the cognitive dimension of entrepreneurship cannot be isolated from its social expression. The way entrepreneurs perceive, interpret, and communicate their experiences shapes the emergence of collective behaviors and organizational norms within entrepreneurial ecosystems. These intersubjective dynamics highlight that cognition is not only an individual process but also a relational one, connecting mental models with leadership and collaboration.

Beyond individual cognition, the concept of entrepreneurial leadership offers a valuable lens for understanding how entrepreneurs act as relational catalysts within their ecosystems. Entrepreneurial leadership emphasizes the capacity to inspire, mobilize, and coordinate others toward collective goals in environments marked by uncertainty and weak formal structures (; ). In emerging economies, entrepreneurs often perform informal leadership roles that compensate for institutional voids, fostering relational climates grounded in empathy, trust, and collaboration (; ). These dynamics align with positive organizational behavior (), which underscores adaptability and optimism as drivers of performance and well-being. Integrating this perspective allows for the reinterpretation of collaborative resilience not merely as an adaptive trait but as a leadership-driven relational process that cultivates cohesion, trust, and shared meaning within entrepreneurial communities.

Entrepreneurial cognition thus encompasses dimensions such as opportunity recognition, self-efficacy, optimism, and perseverance, all of which influence MSME innovation and success (; ). While previous studies have examined entrepreneurial mental models globally, none have explored how Ecuadorian entrepreneurs conceptualize and describe entrepreneurship. This gap is particularly relevant given the dynamic yet underexamined character of Ecuador’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, which plays a vital role in the country’s economic development.

The entrepreneurial landscape in Ecuador is characterized by a predominance of necessity-driven ventures, with 90.8% of early-stage entrepreneurs citing “lack of employment opportunities” as their primary motivation (). MSMEs dominate the economy—representing 95% of businesses and employing 60% of the workforce—yet face persistent barriers, including informality (53.5% of total employment), limited access to financing, and infrastructure deficits. Despite these constraints, Ecuador reports the highest Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) rate in Latin America at 32.7%, reflecting a resilient but low-innovation ecosystem concentrated in trade and food services (75% of TEA). Only 0.15% of entrepreneurs introduce new products or technologies, underscoring the importance of understanding how subjective interpretations of entrepreneurship shape behavior within this context.

These indicators are not merely economic but cognitive expressions of institutional distrust, aversion to technological risk, and a focus on short-term survival. Public policies frequently fail because they overlook these perceptions—for instance, offering formal credit to entrepreneurs who prefer informal financing networks (41%) or promoting innovation without addressing fear of failure (67.9%). Breaking this cycle requires understanding how entrepreneurs define and adapt to their environments.

Our research, therefore, examines a paradoxical ecosystem where high entrepreneurial activity coexists with structural vulnerabilities—reliance on family financing (41%), post-pandemic pessimism (67.9% reporting greater difficulty in starting businesses), and limited technological adoption despite 65% valuing social impact (). By contextualizing these contradictions, the study contributes to both theory and policy, showing how entrepreneurs navigate informality through adaptive cognition and relational networks.

Existing literature confirms that entrepreneurial mindsets shape intentions, strategic actions, and business outcomes (; ; ). Perceptions of risk, opportunity, and self-efficacy determine how entrepreneurs mobilize resources and capabilities, influencing competitiveness and resilience (; ; ; ). These cognitive models—formed through experience, values, and competencies—are inherently context-dependent, making it essential to decode them to design effective, locally attuned support systems.

This study seeks to understand how Ecuadorian entrepreneurs define and interpret entrepreneurship, and to reveal the cultural and psychological factors that shape their ventures. By analyzing entrepreneurs’ own descriptions, it demonstrates how interpretive lenses influence business trajectories and economic outcomes. Positioning subjective perceptions as a central force in Ecuador’s entrepreneurial journey, the study transcends purely structural explanations. It shows how localized narratives reshape institutional pathways, transforming cognitive barriers into drivers of development.

While Latin American entrepreneurship has been widely studied from structural and policy perspectives, empirical analyses of entrepreneurial cognition remain scarce and uneven across countries. Research in Mexico and Chile has focused mainly on institutional frameworks and innovation systems, while studies in Peru have examined necessity-driven entrepreneurship and informality at a descriptive level. Ecuador, despite exhibiting one of the highest rates of early-stage entrepreneurial activity in the region, lacks systematic cognitive analyses exploring how entrepreneurs perceive and define their activity. This study fills that gap by integrating cognitive and relational perspectives to reveal how subjective interpretations shape entrepreneurial behavior in contexts of informality and resource scarcity.

Examining the language entrepreneurs use to describe entrepreneurship offers a unique lens for decoding their perceptions, cultural nuances, and systemic challenges that are often overlooked in quantitative research. Language directly mirrors cognition and culture—the words chosen reveal implicit values and unarticulated experiences. Through lexical analysis, this research bridges subjective experience and structural reality, offering a multidimensional understanding of the Ecuadorian entrepreneurial mindset.

Building on these premises, the study advances a theoretical integration of entrepreneurial cognition and relational leadership. It conceptualizes collaborative resilience not as an individual psychological trait but as a leadership-driven relational process through which empathy, trust, and collective adaptation transform structural constraints into shared purpose. This perspective challenges traditional ecosystem models that focus solely on resources or institutions, emphasizing the socially constructed and emotionally embedded nature of entrepreneurial cognition. In doing so, it proposes a relational–cognitive framework that explains how positive leadership dynamics emerge in informal and uncertain environments, enriching both leadership and entrepreneurship theory.

Accordingly, this study analyzes how Ecuadorian entrepreneurs conceptualize entrepreneurship amid informality, systemic barriers, and limited innovation, unveiling two central narratives—collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability. Specifically, it aims to (1) identify and categorize the lexical patterns entrepreneurs use to describe entrepreneurship and their associated emotional and cognitive connotations; (2) apply clustering techniques to uncover perceptual archetypes and interpret their meanings in terms of collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability; and (3) examine gender-based differences in entrepreneurial perceptions, discussing their implications for theory, policy, and ecosystem development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurial Perceptions and Cognitive Frameworks

Entrepreneurial cognition theory emphasizes that individual perceptions and mental models strongly influence entrepreneurial intentions, strategic behavior, and ultimately venture performance. Understanding these cognitive frameworks provides the foundation for interpreting how entrepreneurs conceptualize and enact entrepreneurship across diverse contexts.

Entrepreneurship is widely recognized as a driver of economic growth, innovation, and social development (; ). However, perceptions of entrepreneurship vary considerably across individuals and societies, reflecting cultural, social, and economic nuances that shape how entrepreneurs define and experience their activity (). These perceptions serve as sociocognitive frameworks that shape entrepreneurial identities and guide how individuals narrate their ventures—as stories of empowerment or resignation—thereby directly influencing persistence or abandonment (; ). Understanding these perceptions is therefore essential to dismantle invisible barriers, challenge stereotypes, and foster ecosystems that promote resilient, context-aligned entrepreneurship (; ).

Entrepreneurial perceptions function as cognitive bridges between intention and action, sustaining engagement even under adverse conditions (; ). However, research often overlooks how these abstract perceptions crystallize into concrete narratives—such as resilience or survival—that entrepreneurs use to rationalize their decisions (; ). These narratives are culturally grounded: collectivist values and community motivations shape how entrepreneurship is interpreted (; ). In necessity-driven contexts, terms such as survival and informality denote adaptive strategies in which formal employment is scarce (). In contrast, in opportunity-driven settings, they emphasize innovation and scalability ().

Contextual factors such as education, prior experience, and institutional support also influence these perceptions. Although widely acknowledged (; ), few studies examine how these factors interact to generate narratives that legitimize entrepreneurship as a desirable career path or portray it as a last resort. Attitudinal traits such as risk tolerance and self-efficacy transform entrepreneurial interest into concrete action (), while realistic self-assessment aligns aspirations with feasible strategies under structural constraints (). However, most existing research privileges quantitative indicators over qualitative insights that could reveal how entrepreneurs internalize these attitudes as shared cultural narratives. The following section, therefore, situates these cognitive lenses within the institutional specificities of emerging economies, clarifying how context shapes the narratives entrepreneurs construct.

2.2. Cultural and Contextual Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies

Beyond individual cognition, entrepreneurship is shaped by social, cultural, and institutional contexts. In emerging economies—where informality and resource scarcity prevail—these conditions decisively influence entrepreneurial behavior and resilience.

Localized empirical studies are essential to capture such dynamics, as perceptions are neither universal nor static. Research by () and () shows that context-specific analyses reveal unique barriers—such as bureaucracy and limited financing—and enablers like community trust and family support. Nevertheless, few studies employ longitudinal designs that trace how perceptions evolve into narratives that justify persistence or abandonment. Understanding these shifts is key to developing policies that address regional challenges while leveraging local strengths. In necessity-driven contexts, interventions should emphasize financial inclusion and capacity development to transform subsistence logics into opportunity-oriented models ().

Perceptions shape not only entry into entrepreneurship but also its sustainability and capacity for reinvention. Entrepreneurs who view their ventures as aligned with personal values or social purpose demonstrate greater resilience and adaptability (; ), although this alignment often conceals tensions between economic return and social impact that can fragment narratives and lead to exits (). This paradox is evident in social entrepreneurship, where community-oriented motivation persists despite operational constraints. Fostering diverse entrepreneurial profiles, therefore, requires normalizing nontraditional paths and legitimizing varied notions of success (; ). Such diversity depends on institutional environments that determine which entrepreneurial forms are considered viable or legitimate.

Entrepreneurial cognition must thus be understood within its institutional environment. Mental models are shaped by informal norms, low-trust settings, and the availability of both material and symbolic resources. In emerging economies, this cognitive framing reflects a persistent tension between agency and structural constraint, as entrepreneurs interpret uncertainty through culturally embedded schemas (; ; ). These institutional pressures generate two dominant narratives: collaborative resilience, grounded in social capital and adaptability, and structural vulnerability, associated with bureaucracy, instability, and weak institutional support. Moreover, feminist and intersectional perspectives reveal that these cognitive frames are gendered—shaped by emotional labor, role expectations, and unequal access to resources (; ; ). Integrating these cognitive, institutional, and gendered dimensions provides a comprehensive basis for interpreting how entrepreneurs in emerging economies construct meaning around their experiences.

The intersection of relational leadership and positive organizational behavior provides a theoretical foundation for understanding collaborative resilience as a socially constructed capability. Relational leadership emphasizes the creation of trust-based, high-quality relationships that enable coordination and psychological safety in uncertain environments (; ). Positive organizational behavior complements this view by highlighting optimism, empathy, and adaptability as psychological resources that foster individual and collective well-being (). When combined, these perspectives reveal how affective and cognitive processes interact to generate collective resilience—transforming emotional energy, mutual trust, and prosocial motivation into collaborative strength. Within entrepreneurial ecosystems characterized by informality and resource scarcity, this integration explains how positive relational dynamics operate as informal leadership mechanisms that sustain cohesion and adaptive capacity under pressure.

2.3. Gendered Perspectives and the Lexicon of Entrepreneurship

Building on this interplay between cognition and institutional conditioning, language and discourse emerge as the most visible expressions of how entrepreneurs internalize and communicate their experiences. The words and metaphors used to describe entrepreneurship reveal underlying cognitive, emotional, and gendered structures that shape how societies understand and value entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurship, as a multifaceted and evolving concept, has been defined through multiple perspectives—innovation, risk-taking, value creation, and social impact—reflecting its contextual and interpretive diversity (; ). A synthesis of key terms used in scholarly literature is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Words Used by Scholars to Describe Entrepreneurship.

Because language mirrors thought, analyzing the words entrepreneurs and scholars use provides insight into how the phenomenon is conceptualized across contexts. Lexical studies highlight terms such as innovation, adaptability, creativity, and resilience as recurrent descriptors, underscoring both the complexity of entrepreneurship and the cognitive frameworks that sustain it. Understanding this lexicon allows researchers to trace how entrepreneurial discourse evolves and how gender, culture, and context shape its meaning.

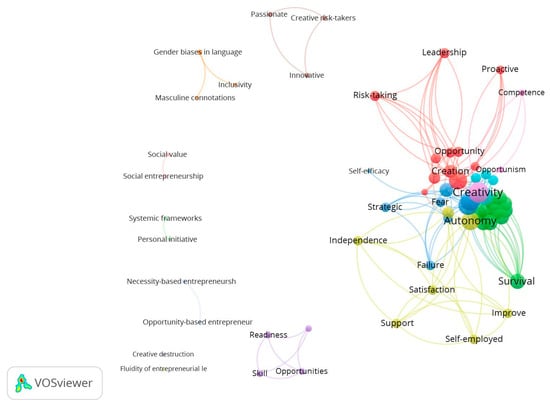

The co-occurrence network derived from bibliometric analysis (Figure 1) illustrates the core structure of entrepreneurial discourse. The central cluster revolves around innovation, creation, risk-taking, and leadership, consolidating innovation and strategic management as the central identity of entrepreneurship (; ). A secondary cluster differentiates between opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship (), reflecting the motivational duality that guides entrepreneurial behavior.

Figure 1.

Co-ocurrence map.

Complementary clusters highlight the social and gendered dimensions of entrepreneurship. Terms such as social entrepreneurship and social value underscore the collective orientation of entrepreneurial activity (), while linguistic studies expose gender biases that associate entrepreneurship with masculinity (; ). This aligns with the concept of a fluid entrepreneurial lexicon (), which evolves with changing socioeconomic realities.

Foundational notions such as creative destruction (), innovation, and resilience () reveal entrepreneurship as a disruptive yet adaptive phenomenon that links individual initiative, systemic transformation, and competitiveness. Altogether, the network demonstrates the polysemic and evolving nature of entrepreneurial language—where innovation, social impact, and linguistic critique intersect to shape how entrepreneurship is conceptualized and practiced across contexts.

In the Ecuadorian context, entrepreneurship plays a pivotal role within a constantly transforming economy. Portrayals in national digital media provide valuable insight into the country’s socioeconomic narratives. Recognizing that media content is not scientific literature, this study examined keywords and expressions used by Ecuadorian digital outlets to describe entrepreneurship between 2020 and 2025.

The comparison between academic and media vocabularies reveals substantial overlaps: terms such as necessity, employment, opportunity, bureaucracy, competition, fear, failure, risk, uncertainty, adaptation, support, skills, success, growth, and innovation dominate both domains. This convergence indicates that entrepreneurship is consistently framed across scholarly and social discourses, reflecting its centrality to Ecuador’s economic and cultural identity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Words Used by Ecuadorian Digital Media to Describe Entrepreneurship.

In this sense, discourse operates as both a cognitive and institutional artifact—reflecting how entrepreneurs make sense of their environment while reproducing the cultural logics that sustain it. Understanding these linguistic patterns thus becomes a methodological gateway for examining how cognition, emotion, and structure intertwine in entrepreneurial experience. Building on this theoretical foundation, the following section translates these conceptual dimensions into empirical design, using lexical analysis and clustering techniques to identify the cognitive archetypes that define Ecuadorian entrepreneurship.

3. Materials and Methods

The study population consists of micro and small entrepreneurs from the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (), which plays a fundamental role in the Ecuadorian economy and is established as one of the country’s main productive engines. The composition of the MSME population is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Total MSME Population.

Given that economic sectors such as services and trade account for 87.96% of all ventures, this study focuses on these two sectors. To ensure the statistical validity of the research, the sample size was calculated using an infinite-population approach, which is appropriate when the target population size is sufficiently large and not entirely known (Z = 1.96, p = q = 0.5, maximizing variability in the absence of prior information). Initially, a 3% margin of error (0.03) was considered, yielding a sample size of 1068 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Initial population and sample size.

The selection of participants began by identifying entrepreneurs from each sector, who were then asked to recommend others meeting the criteria of sector affiliation and more than three years of operation, ensuring that respondents had surpassed the start-up phase. This iterative process continued until the desired sample size was reached. Snowball sampling was adopted because no comprehensive database of Ecuadorian MSMEs exists, and a significant portion of entrepreneurs operate informally, outside official registries or associations. This method allowed access to a fragmented and otherwise invisible population, capturing the heterogeneity that defines the Ecuadorian entrepreneurial ecosystem and including perspectives typically excluded from probabilistic approaches.

To minimize potential bias, participants were intentionally drawn from diverse sectors and socioeconomic strata, with a limit on the number of referrals per respondent. Sectoral distribution within the sample was checked against the structure of the Metropolitan District of Quito to ensure balance. These measures strengthened validity by preventing overrepresentation of homogeneous networks and by achieving conceptual and theoretical representativeness, mirroring national MSME patterns by sector and gender rather than strict statistical representativeness. Although the findings are not statistically generalizable, they provide strong theoretical insight into cognitive and relational dynamics across heterogeneous networks.

After eliminating 188 incomplete surveys, the final analytical sample comprised 880 companies, raising the margin of error slightly from 3.0% to 3.3%, still below the 5% threshold typical for studies of this nature. This sample size provides adequate statistical power while maintaining methodological rigor and practical feasibility. Overall, the design balances accessibility with reliability, offering a robust empirical foundation consistent with the study’s objectives.

The final sample included 64.2% from services and 35.8% from trade; micro-enterprises (37.2%), small enterprises (61.7%), and medium-sized enterprises (1.1%). Gender representation was nearly balanced—51.25% men and 48.75% women—allowing for gender-based comparative analysis.

The Polydiagnostic Method of Forced-Choice Classifications rests on three theoretical pillars: forced-choice surveys, polydiagnostic evaluation frameworks, and diagnostic classification models (DCM). Forced-choice methodologies eliminate neutral responses, compelling participants to prioritize attributes, thereby reducing social desirability bias and improving data validity (; ; ; ). This design aligns with psychological principles emphasizing explicit decision-making to uncover latent preferences, making it particularly suitable for evaluating complex constructs such as entrepreneurial perceptions.

The polydiagnostic framework integrates multiple criteria to capture the multidimensional nature of behavior (). Evaluating attributes across emotional, cognitive, and contextual dimensions avoids oversimplification and enables a comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurship. For example, it allows for simultaneous assessment of resilience, creativity, and risk tolerance, reflecting how key traits interact to shape entrepreneurial success.

Finally, Diagnostic Classification Models convert forced-choice data into actionable profiles by identifying mastery levels of specific attributes. In entrepreneurship research, DCMs help classify individuals into distinct entrepreneurial archetypes, facilitating targeted interventions. Collectively, these three components produce a bias-resistant and multidimensional diagnostic approach, validated in organizational and psychological contexts (; ).

The instrument assessed entrepreneurs’ emotional and cognitive perceptions. Participants evaluated 75 entrepreneurial qualities, grouping them into five sets of three according to perceived relevance (Table 5). Scores ranged hierarchically from 5 (most representative) to 1 (least representative).

Table 5.

Entrepreneurial Qualities.

The reliability analysis using Omega coefficients (ω) confirmed strong internal consistency and adequacy of the survey. Both the total Omega (ω = 0.84) and Cronbach’s Alpha (α = 0.83) exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating solid overall reliability. The hierarchical Omega (ωh = 0.59) and its asymptotic value (ωha = 0.70) showed a moderate general factor effect, explaining 52% of the common variance and reinforcing the construct’s structural relevance.

Model fit indices further supported the instrument’s validity. The RMSEA value (0.093), while slightly above the ideal level, falls within the acceptable exploratory range (0.08–0.10) for complex multidimensional models (; ). This value reflects the inclusion of emotional, cognitive, and contextual factors rather than any specification error. Complementary indicators—standardized residuals ≤ 0.04, lower BIC for grouped factors, significant factor loadings (λ ≥ 0.20), and high factor score adequacy (R2 = 0.73)—confirm a coherent multidimensional structure and robust convergent validity.

Together, these results validate the instrument’s suitability for theoretical and applied analysis, ensuring that the derived outcomes consistently reflect the underlying construct and demonstrate the survey’s psychometric robustness.

3.1. Data Processing and Analysis

In this study, the authors conducted all analyses using the R programming environment (version 4.4.3) (). To analyze how entrepreneurs describe entrepreneurship, two main dimensions were evaluated: association intensity and characteristic popularity, applying categorization methods based on proportional intervals. This approach ensures standardized classification, allowing for meaningful comparisons between different characteristics regardless of their absolute values.

3.2. Calculation of Mean Association Intensity

Each characteristic evaluated in the study was analyzed to obtain its mean association intensity, calculated as the average of participants’ scores. Three categories were established:

- High intensity: Values in the upper third of the intensity range.

- Medium intensity: Values in the middle third.

- Low intensity: Values in the lower third.

The range was determined dynamically, setting zero as the minimum possible value and using the maximum observed value in the dataset to define category thresholds. The use of proportional intervals ensures an equitable distribution of categories, avoiding arbitrary cutoffs and enabling relative evaluation that adapts to the data distribution.

3.3. Calculation of Popularity

The popularity of each characteristic was defined as the percentage of participants who assigned the highest possible rating. The same criterion was applied, using three proportional intervals: 0 represented the lowest possible value, and the maximum observed value served as the upper limit. This approach standardizes classification and maintains consistency across different datasets, ensuring comparability.

The methodological procedures described above provide a rigorous framework for identifying and interpreting the cognitive structures that underlie entrepreneurial perceptions. Building on this design, the following section presents the main results derived from the lexical analysis and clustering models, illustrating how entrepreneurs’ language patterns reveal distinct conceptualizations of entrepreneurship in the Ecuadorian context.

4. Results

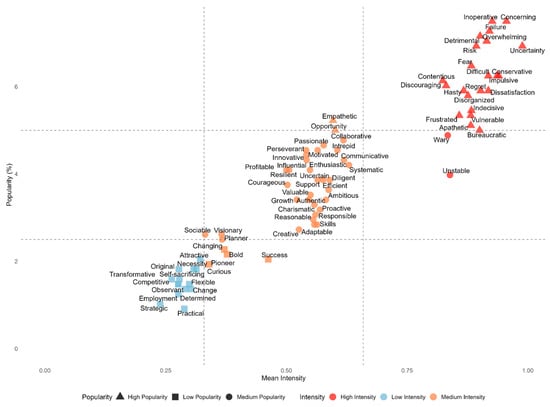

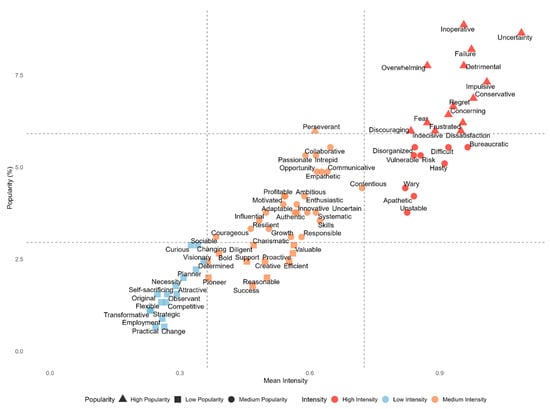

The values obtained were plotted in a scatter plot, with the X-axis representing the mean association intensity and the Y-axis representing popularity (%). To enhance the interpretability of the results, reference lines were included to divide the plot into nine quadrants according to intensity and popularity categories. The generated scatter plot provides a visual representation of the relationship between the mean association intensity and the popularity of each evaluated characteristic. The reference lines divide the space into nine regions, facilitating the identification of patterns in the perception of entrepreneurship.

- Upper-right cells (high intensity—high popularity): Characteristics that exhibit both strong association and high popularity. These elements are considered central to the concept of entrepreneurship because they are widely recognized and closely linked to the entrepreneurial context.

- Upper-middle cells (medium intensity—high popularity): Characteristics that are highly popular but have a moderate association with entrepreneurship. These aspects are commonly mentioned, although their connection to the entrepreneurial concept may be less pronounced.

- Upper-left cells (low intensity—high popularity): Characteristics that are very popular but weakly associated with entrepreneurship. These are traits or ideas frequently discussed but do not necessarily align with the core dimensions of entrepreneurship.

- Middle-right cells (high intensity—medium popularity): Characteristics with a strong association to entrepreneurship but lower popularity. These elements may be crucial to understanding entrepreneurship, although they are less commonly recognized.

- Central cells (medium intensity—medium popularity): Characteristics with moderate levels of both intensity and popularity. These traits or attributes are balanced in terms of frequency of mention and the strength of their association with entrepreneurship.

- Middle-left cells (low intensity—medium popularity): Traits that are somewhat popular but show a weak association with the entrepreneurial concept. These characteristics may reflect peripheral aspects of entrepreneurship that are frequently discussed but not deeply connected to the field’s core understanding.

- Lower-right cells (high intensity—low popularity): Characteristics with a strong association but limited popularity. These may represent crucial aspects of entrepreneurship that are underrepresented in discourse and warrant greater attention and recognition.

- Lower-middle cells (medium intensity—low popularity): Characteristics that are moderately associated with entrepreneurship but are less discussed. These could represent emerging or niche elements within the entrepreneurial space.

- Lower-left cells (low intensity—low popularity): Characteristics with weak associations and low popularity. These traits are less recognized and have a minimal impact on the general perception of entrepreneurship.

The use of proportional scaling on both axes ensured a standardized comparison of characteristics, while color coding and shape differentiation facilitated the identification of trends and groupings within the dataset. This visualization enabled strategic analysis of which aspects of entrepreneurship are most prominent and which may require further conceptual reinforcement. The results were also stratified by gender to reveal nuanced differences and support personalized interpretations.

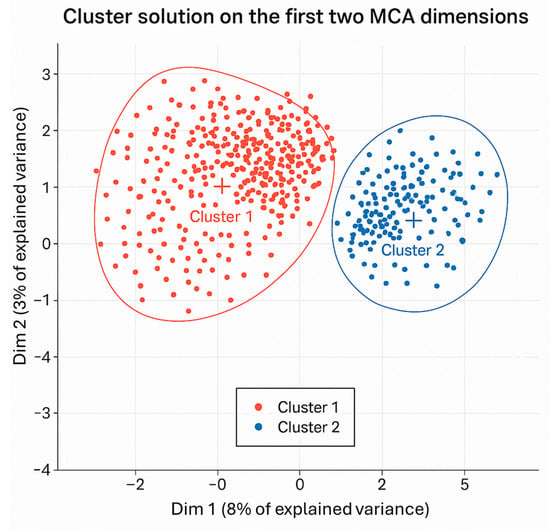

To identify participant profiles, the K-means clustering algorithm was applied following standard preprocessing steps: data loading, normalization, determination of the optimal number of clusters, and visualization. Variables were normalized using the scale() function to ensure equal contribution to distance calculations. The optimal cluster number was determined using the silhouette index method implemented by the fviz_nbclust() function from the factoextra package, selecting the value that maximized the index and thus provided the most significant internal homogeneity and separation.

Subsequently, the K-means algorithm was executed with the argument nstart = 25, which performs 25 random initializations and retains the solution minimizing within-cluster variance. The final cluster distribution was visualized using the fviz_cluster() function (factoextra), allowing for a precise observation of data groupings within the normalized feature space and straightforward interpretation of the resulting profiles (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intensity—Popularity (sample).

This methodological design ensures systematic collection of data on perceived entrepreneurial attributes while facilitating the multidimensional analysis of both the intensity and prevalence of associations. The approach supports reproducibility and provides insights into how diverse demographics conceptualize entrepreneurship.

The analysis of characteristics associated with entrepreneurship reveals a nuanced and profound human landscape. The most intense and recognized attributes are not those celebrating success or innovation but rather those reflecting the struggles, uncertainties, and challenges inherent to the entrepreneurial process. This finding highlights a collective narrative that positions entrepreneurship as a complex phenomenon, marked by powerful emotions and volatile contexts that demand resilience, adaptability, and courage.

Through this analysis, significant patterns emerge that help us understand how these characteristics shape perceptions and the overall experience of entrepreneurship. To facilitate interpretation, Figure 2 includes reference lines that divide the coordinate plane into nine quadrants based on intensity (x-axis) and popularity (y-axis). Each point represents one entrepreneurial attribute evaluated by participants. The position of the points, therefore, reflects how strongly each attribute is associated with entrepreneurship and how frequently it was prioritized across the sample.

4.1. Upper-Right Quadrant (High Intensity—High Popularity)

Summary of main figures. Attributes in this quadrant have average intensity ≥ 0.85 and popularity > 7%, making them the most representative traits in the dataset. The highest-frequency items are Fear, Failure, Uncertainty, Vulnerable, and Risk, each exceeding the 7% popularity threshold, with Overwhelmed, Regret, and Frustrated also appearing above mid-range values. Collectively, these indicators confirm that emotionally charged descriptors dominate the top-right area of the map before interpretation.

The upper-right quadrant (high intensity–high popularity) groups the set of words most strongly and frequently associated with the concept of entrepreneurship in the dataset. Empirically, these attributes have the highest average intensity scores and appear in more than 7% of all participant selections, making them central elements in the collective perception of entrepreneurship.

A distinctive pattern emerges in this quadrant: the most recurrent attributes are emotionally charged terms such as Fear, Failure, Uncertainty, Vulnerability, and Risk. Their high positioning along both axes indicates that respondents consistently associate entrepreneurship with instability, emotional exposure, and constant decision pressure. These terms dominate the upper-right space of the scatterplot, evidencing the salience of challenge-related language over success-oriented descriptors.

Complementary attributes with medium intensity but high popularity—such as Overwhelmed, Regret, and Frustrated—reinforce this trend by reflecting the cognitive load and emotional demand inherent in entrepreneurial activity. The predominance of these terms reveals a shared lexical field characterized by tension and volatility rather than triumph or optimism.

From a structural perspective, the upper-right quadrant thus reflects an empirical concentration of high-frequency, high-intensity words associated with the affective dimension of entrepreneurship. These attributes collectively portray entrepreneurship as a demanding and uncertain process, dominated by perceptions of risk, emotional effort, and adaptive pressure. Their descriptive clustering provides the empirical foundation for later analysis of dual narratives discussed in Section 5.

4.2. The Central Quadrant (Medium Intensity—Medium Popularity)

Summary of main figures. Items located in the central band exhibit a mean intensity of 3.2–3.8 and a popularity of around 4–6%. Recurrent terms include Adaptable, Collaborative, Creative, Resilient, Practical, Systematic, Flexible, Innovative, and Proactive, which together define a balanced, procedural profile of entrepreneurship prior to the interpretive discussion.

The words positioned in the central quadrant (medium intensity–medium popularity) represent attributes that participants consistently mention, but without the emotional or extreme emphasis observed in other areas of the lexical map. These traits occupy intermediate values on both axes—neither highly polarized nor marginal—indicating a balanced role within the collective perception of entrepreneurship.

From an empirical standpoint, this quadrant contains terms with average intensity values of 3.2–3.8 and medium-level popularity scores, appearing in approximately 4–6% of all responses. The most frequent words include Adaptable, Collaborative, Creative, and Resilient, along with Practical, Systematic, and Motivated. Together, these terms describe entrepreneurship in functional and procedural terms rather than emotional or symbolic ones.

The data suggest a cluster of attributes related to practical competence and operational discipline. Words such as Flexible, Innovative, and Proactive fall within the same range, reinforcing the view of entrepreneurship as a dynamic yet measured process that values organization and adaptability. Similarly, traits such as Empathetic, Collaborative, and Responsible occur with moderate frequency, indicating that social and relational dimensions are present but not dominant in the overall perception.

Overall, the central quadrant depicts the empirical midpoint of the entrepreneurial lexicon—composed of attributes that are moderately intense and moderately popular, bridging the gap between emotionally charged perceptions and peripheral technical skills. This descriptive profile serves as a reference point for the dual narratives analyzed in Section 5, where these traits are interpreted in relation to collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability.

4.3. The Lower-Left Quadrant (Low Intensity—Low Popularity)

Summary of main figures. This quadrant groups the least salient attributes, with popularity < 3% and the lowest mean intensity scores in the sample. Items are predominantly technical/operational—e.g., Practical, Strategic, Planner, and Observant—indicating peripheral relevance before the subsequent interpretation.

The set of words located in the lower-left quadrant (low intensity—low popularity) corresponds to attributes that appear infrequently and are weakly associated with the entrepreneurial construct. Their empirical findings indicate that respondents rarely prioritize these traits when describing entrepreneurship, suggesting a peripheral rather than a central role in the collective perception of the phenomenon.

From a quantitative standpoint, these attributes exhibit the lowest mean intensity values and appear in fewer than 3% of participant responses within the upper scoring ranges. Most belong to the technical or operational dimension of entrepreneurship, including terms such as Practical, Strategic, Planner, and Observant.

These characteristics cluster around functional and procedural aspects of entrepreneurial activity rather than emotional or social dimensions. Their presence in the dataset nonetheless reflects a layer of entrepreneurship oriented toward organization, foresight, and analytical behavior. While less visible in discourse, these terms contribute to mapping the diversity of cognitive associations identified in the lexical space.

Overall, the lower-left quadrant groups traits that are empirically marginal in both frequency and perceived relevance, contrasting with the highly emotional and widely recognized attributes in the upper-right quadrant.

4.4. Cluster 1 Analysis (Red): A Coherent and Multidimensional Entrepreneurial Profile

Summary of main figures. Cluster 1 includes 548 participants (62.3%) and shows a strong association between intensity and popularity (r = 0.914). High-intensity/high-popularity items center on Ambitious (0.908/5.47%), Collaborative (0.916/7.12%), Communicative (0.903/6.93%), Empathetic (0.878/8.21%), Innovative (0.808/7.12%), and Opportunity (0.923/8.03%), with Resilient, Perseverant, Charismatic, and Influential reinforcing the profile. Negative/passive terms (e.g., Apathy, Bureaucracy, Frustration, Uncertainty) remain below ~3%, confirming a predominantly positive–relational configuration prior to interpretation.

Cluster 1, which includes 548 participants (62.3% of the total sample), shows a strong positive correlation between trait intensity and popularity (r = 0.914). This statistical pattern confirms high internal consistency among respondents who assigned similar relevance to the same set of attributes. The cluster is therefore characterized by a coherent alignment between what participants most frequently selected and what they considered most representative of entrepreneurship.

The attributes with both high intensity and high popularity form the empirical core of this cluster. The most recurrent terms are Ambitious (0.908/5.47%), Collaborative (0.916/7.12%), Communicative (0.903/6.93%), Empathetic (0.878/8.21%), Innovative (0.808/7.12%), and Opportunity (0.923/8.03%). These words appear in the upper-right region of the clustering plot, indicating strong consensus that entrepreneurship is associated with proactive and relational attributes.

A secondary layer of descriptors—Resilient (0.755/6.57%), Perseverant (0.801/7.12%), Charismatic (0.836/5.29%), and Influential (0.786/6.57%)—shows medium intensity but relatively high popularity, adding nuance to the profile. Traits such as Risk (0.597/4.56%) and Profitability (0.719/6.57%) appear less frequently yet remain within the same conceptual cluster, denoting practical considerations linked to business performance.

Conversely, words with very low popularity—Apathy (1.28%), Bureaucracy (2.55%), Frustration (2.74%), and Uncertainty (2.92%)—register minimal co-occurrence within this group, evidencing a consistent avoidance of negative or passive attributes. This empirical contrast reinforces the homogeneity of the cluster and its concentration around proactive and relational characteristics.

Figure 3 illustrates the two clusters obtained through the K-means algorithm. The red area corresponds to Cluster 1, whose members share a closely aligned pattern of high-frequency, high-intensity responses. The graphical separation indicates a compact and internally homogeneous group, providing the empirical foundation for subsequent interpretation in Section 5.

Figure 3.

Cluster representation.

Overall, Cluster 1 represents a statistically coherent configuration in which positive, relational, and proactive attributes co-occur with high frequency and intensity. These results describe a multidimensional but internally consistent profile that will later be interpreted in theoretical terms of collaborative and pragmatic entrepreneurship.

4.5. Cluster 2 Analysis (Green): A Narrative of Systemic Vulnerability and Disillusionment in Entrepreneurship

Summary of main figures. Cluster 2 comprises 332 participants (37.7%) with a very high intensity–popularity association (r = 0.984). The most frequent items are Apathy (1.515/9.34%), Worrisome (1.617/13.55%), Discouraging (1.473/12.95%), Conflictive (1.611/13.86%), Frustrated (1.431/9.64%), Fear (1.506/10.54%), Regret (1.434/11.45%), Risk (1.383/10.84%), Uncertainty (1.605/13.55%), and Bureaucratic (1.530/9.04%). Favorable/relational terms (e.g., Innovative, Collaborative, Empathetic) occur at near-zero levels, quantitatively delimiting a constraint-centric profile prior to interpretation.

Cluster 2, comprising 332 participants (37.7% of the total sample), shows a very high positive correlation between trait intensity and popularity (r = 0.984). This indicates a substantial internal homogeneity in responses, suggesting that participants in this group consistently associated entrepreneurship with similar sets of attributes.

The most frequent terms in this cluster are Apathy (1.515/9.34%), Worrisome (1.617/13.55%), Discouraging (1.473/12.95%), Conflictive (1.611/13.86%), Frustrated (1.431/9.64%), Fear (1.506/10.54%), and Regret (1.434/11.45%). These words occupy the upper-left area of the cluster map, characterized by high intensity and moderate-to-high popularity values, indicating a predominant association of entrepreneurship with negative emotional states and operational constraints.

Additional descriptors such as Risk (1.383/10.84%), Uncertainty (1.605/13.55%), and Bureaucratic (1.530/9.04%) reinforce this trend, indicating that participants perceive entrepreneurship as linked to instability and administrative obstacles. A smaller subset of terms—Difficulty (1.572/10.84%), Impulsive (1.431/9.04%), and Indecisive (1.542/11.14%)—appear with high intensity but lower popularity, showing consistent recognition of these challenges even if less frequently mentioned.

Notably, positive or opportunity-related traits such as Innovative, Collaborative, and Empathetic register intensity and popularity values close to zero, indicating a limited presence of affirmative or relational terms within this cluster. This absence reinforces the cluster’s empirical coherence as a group focused on perceptions of limitation rather than possibility.

This cluster corresponds to the green group previously shown in Figure 3, which is clearly separated from the red cluster along both intensity and popularity dimensions. The compact grouping of points reflects its internal consistency and high agreement among participants.

Overall, Cluster 2 represents an empirical configuration dominated by negative affective and structural terms, with consistently high frequency and intensity values. These results describe a group of entrepreneurs whose lexical choices concentrate around perceived barriers, uncertainty, and emotional tension. The interpretation of this pattern—particularly regarding systemic vulnerability and its implications for entrepreneurial cognition—is developed in Section 5.

4.6. Comparative Synthesis: Cluster 1 vs. Cluster 2—Divergent Views on Entrepreneurship

Summary of main figures. The comparative contrast reveals two polarized yet internally coherent profiles: Cluster 1 (62.3%; r = 0.914) emphasizes collaboration, empathy, opportunity, and innovation; Cluster 2 (37.7%; r = 0.984) emphasizes uncertainty, bureaucracy, fear, and frustration. Table 6 summarizes the numerical gaps across agency, risk, emotional framing, and salient absences, providing the quantitative baseline before theoretical interpretation. The comparative analysis of Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 reveals two empirically distinct configurations of entrepreneurial perception, differentiated by their lexical composition, emotional tone, and association between intensity and popularity.

Table 6.

Epistemological Contrast between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2.

Cluster 1 groups attributes related to collaboration, empathy, and opportunity, while Cluster 2 concentrates on terms expressing uncertainty, bureaucracy, and fear. The correlation coefficients (r = 0.914 and r = 0.984, respectively) confirm that both groups are internally consistent yet polarized in their framing of entrepreneurship.

The quantitative contrast highlights that Cluster 1 emphasizes proactive and relational attributes, whereas Cluster 2 centers on structural and emotional obstacles. These differences delineate two dominant empirical tendencies within the dataset: one characterized by adaptive agency and positive social interaction, and another by perceived constraint and emotional strain. Together, they provide the empirical foundation for the theoretical discussion developed in Section 5.

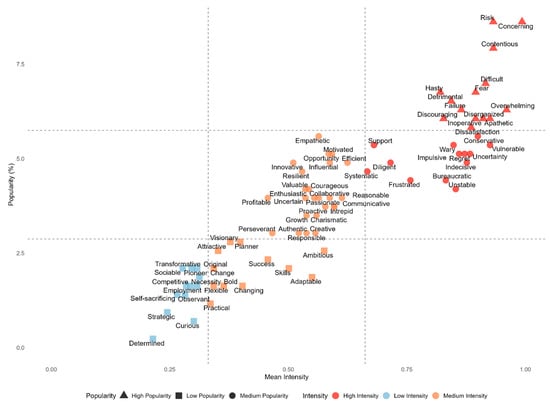

A subsequent gender-based comparison further refines these patterns, identifying convergences and divergences in how men and women describe entrepreneurship (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Intensity—Popularity (female).

Figure 5.

Intensity—Popularity (male).

Among women, the highest-intensity and most popular attributes include Worrisome (0.993/8.62%) and Risk (0.932/8.62%). These are followed by Contentious (0.932/7.93%) and Discouraging (0.828/6.06%), indicating that female participants associate entrepreneurship with emotional pressure and interpersonal complexity.

Among men, Uncertainty (1.089/8.65%), Impulsive (1.009/7.32%), Failure (0.973/8.21%), and Inoperative (0.956/8.87%) show the highest scores, reflecting stronger associations with operational instability and decision-making pressure. While women’s vocabulary reflects emotional and relational challenges, men’s emphasizes structural and behavioral difficulties.

In terms of collaboration, women show higher intensity for Support (0.681/5.36%), whereas men assign greater popularity to Collaborative (0.647/5.54%), distinguishing emotional support from strategic cooperation.

Both genders attribute limited importance to innovation-oriented traits—Innovative, Visionary, and Strategic—which register low intensity and popularity in both groups (below 5%). Personality-related terms show moderate gender differentiation: women emphasize Empathetic (0.564/5.59%) and Resilient (0.529/4.66%), whereas men prioritize Perseverant (0.612/5.99%) and Resilient (0.483/3.55%).

Finally, Failure and Fear emerge as high-frequency descriptors across genders, confirming that perceptions of uncertainty and emotional stress are common to all participants. These empirical findings provide the basis for the interpretive discussion in Section 5, where their theoretical implications are examined through the frameworks of entrepreneurial cognition and ecosystem resilience.

5. Discussion

Building on the empirical evidence presented in Section 4, this discussion interprets the identified lexical and clustering patterns through the theoretical lenses of entrepreneurial cognition and resilience. The analysis focuses on how emotional, relational, and structural dimensions interact to produce distinct cognitive models of entrepreneurship in emerging economies. These models reveal how individual agency and contextual constraint coexist within entrepreneurial experience, giving rise to two core narratives: collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability.

5.1. Dual Narratives of Entrepreneurship: Collaborative Resilience and Structural Vulnerability

This study identifies a fundamental duality in how Ecuadorian entrepreneurs perceive entrepreneurship: collaborative resilience, centered on empathy, adaptability, and social networks, and structural vulnerability, marked by bureaucracy, fear, and emotional strain. Though apparently opposed, these narratives are interrelated and reflect how entrepreneurs reinterpret global discourses within a highly informal and resource-constrained ecosystem.

Entrepreneurship in Ecuador thus emerges as a paradox that combines strength and fragility, opportunity and risk. Emotional tension acts not only as a barrier but also as a catalyst for learning and adaptation, confirming that vulnerability is integral to the construction of opportunities—a mechanism consistent with entrepreneurial cognition theory (; ).

Cluster 1 embodies collaborative resilience: a human-centered configuration grounded in empathy, networking, and pragmatic execution. Cluster 2 represents structural vulnerability: a cognitive response to systemic barriers and institutional fragility. Their coexistence reveals that entrepreneurship operates along a continuum between agency and constraint rather than as discrete conditions. Resilience, therefore, should be seen as a relational capability emerging from collective adaptation to uncertainty.

In this sense, collaborative resilience represents a leadership-driven mechanism through which entrepreneurs collectively mobilize emotional and cognitive resources to maintain cohesion under uncertainty. Rather than being an individual trait, it unfolds through relational processes—empathy, mutual trust, and shared learning—that mirror the principles of relational leadership () and positive organizational behavior (). These dynamics explain how leadership emerges organically in informal ecosystems, sustaining entrepreneurial motivation and social capital even in the absence of formal structures.

From a relational-leadership perspective, these narratives express not only cognitive frames but also leadership processes that shape how entrepreneurs engage with peers and networks. In the absence of formal hierarchies, many act as de facto leaders, cultivating trust-based relationships that foster collaboration under constraint. This extends ’s () notion of entrepreneurial leadership, emphasizing its affective and communal dimensions, where leadership arises from shared meaning rather than authority. Consequently, collaborative resilience appears as a form of positive leadership in which emotional intelligence and social cohesion replace structural power as sources of influence.

The narrative of collaborative resilience aligns with evidence linking social networks and adaptability to entrepreneurial success (; ). However, its relative neglect of structural barriers contrasts with findings from other emerging economies where institutions decisively shape entrepreneurial behavior (; ). Similar tendencies to individualize success while minimizing contextual adversity have been noted in Mexico and South Africa (; ).

Conversely, the narrative of structural vulnerability highlights a critical dimension of informal economies: risk as a systemic condition rather than a voluntary choice (). Consistent with prior research, short-term survival often replaces innovation as the dominant logic (; ), illustrating how structural barriers constrain opportunity creation while reinforcing reliance on informal networks.

These findings fulfill the study’s general objective by showing that Ecuadorian entrepreneurs conceptualize entrepreneurship through two interdependent yet contrasting narratives that together capture the cognitive and structural dualities that define entrepreneurship in emerging economies.

The analysis also advances entrepreneurial cognition theory by reframing resilience as a context-embedded cognitive process rather than an individual trait. Within fragile ecosystems, resilience arises from social interaction, shared meaning, and collective adaptation—integrating emotional intelligence and relational agency into cognitive models of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs thus do not merely react to adversity but reconstruct it through collaboration, extending cognition models toward socially constructed interpretations of uncertainty.

Moreover, the concept of collaborative resilience provides new conceptual vocabulary for entrepreneurship research. It explains how empathy, mutual trust, and solidarity operate as cognitive enablers that transform structural constraints into shared opportunities, bridging entrepreneurial cognition with relational leadership and positive organizational behavior. By positioning collaboration as both a cognitive and leadership process, the study contributes to a more integrative understanding of how entrepreneurs generate stability and purpose under systemic fragility.

Finally, the Ecuadorian case illustrates a recurring pattern across emerging economies—such as Mexico, South Africa, and Eastern Europe—where high entrepreneurial dynamism coexists with institutional fragility. The duality between collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability thus transcends national boundaries, representing a universal adaptive mechanism through which entrepreneurs convert adversity into communal strength. This comparative insight situates Ecuador within a global framework of relational adaptation, enhancing the external validity and theoretical resonance of the proposed model.

Taken together, these insights reaffirm that collaborative resilience constitutes a form of distributed relational leadership—an emergent process through which entrepreneurs collectively organize, learn, and sustain motivation in the absence of formal authority. By translating emotional intelligence and mutual trust into coordinated action, this leadership dynamic converts individual coping mechanisms into collective adaptability, reinforcing the theoretical bridge between entrepreneurial cognition and positive organizational behavior.

5.2. Lexical and Cognitive Patterns: Empirical Evidence of Perceptual Archetypes

Aligned with the first and second specific objectives, the integration of lexical and clustering analyses reveals two perceptual archetypes shaping entrepreneurial cognition: one oriented toward adaptive agency and another constrained by structural dependency. These archetypes expose the dynamic tension between effort and limitation that defines entrepreneurial reasoning in highly informal economies such as Ecuador’s.

The lexical prominence of emotional and pragmatic terms—particularly resilience, risk, and uncertainty—indicates that entrepreneurship is perceived less as innovation and more as adaptation to adversity. This finding challenges theoretical models that idealize risk tolerance () and underscores the need for context-sensitive frameworks of entrepreneurial behavior. In emerging economies, entrepreneurial agency often depends on informal social capital rather than on institutional mechanisms that remain inaccessible or unreliable (; ).

Beyond the dominant clusters, the low-intensity and low-popularity quadrant reveals a subtler cognitive dimension. Terms such as Practical, Strategic, and Planner, though peripheral in discourse, represent tacit competencies of organization and procedural control. Their low prominence suggests that technical reasoning and managerial foresight are undervalued in collective representations of entrepreneurship—despite their importance for operational stability under uncertainty. This dimension complements the emotional and social components of the dominant clusters, completing a multidimensional view of entrepreneurial cognition.

The contrast between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (Table 6) reinforces these archetypes. The first embodies proactive, human-centered agency, whereas the second reflects structural constraint and emotional exhaustion. Cognitively, entrepreneurs oscillate between optimism derived from collaboration and realism grounded in adversity. These dual configurations confirm the coexistence of affective and structural cognition, where informal mechanisms frequently substitute for institutional support.

At the theoretical level, these findings caution against romanticizing resilience. As noted by () and (), overemphasizing personal agency can obscure structural inequities and sustain narratives that individualize failure. Recognizing the coexistence of necessity- and opportunity-driven logics is therefore essential for designing policies that reflect cognitive diversity and contextual constraint.

Overall, the integration of lexical evidence and structural interpretation fulfills the study’s first two specific objectives, demonstrating that cognitive archetypes are embedded within the broader institutional realities of entrepreneurship in emerging economies.

5.3. Gendered Cognition and Practical Implications

Gender-based differences reveal that perceptions of entrepreneurship polarize along relational and structural dimensions, extending the findings of () and (). Women tend to frame entrepreneurship as an emotionally demanding process that depends on interpersonal support networks, reflecting the relational tensions of balancing economic activity with social and family responsibilities. Men, conversely, emphasize operational and structural barriers—such as uncertainty, impulsiveness, and failure—associated with the pressure to sustain business control in adverse environments. These patterns confirm that entrepreneurial cognition is mediated by gendered social roles, shaping how opportunities, risks, and responsibilities are perceived and managed.

These gendered configurations reveal complementary expressions of leadership and resilience. Women’s relational–emotional framing aligns with the principles of relational leadership (), emphasizing empathy, support, and collective learning as drivers of collaborative resilience. Men’s structural–operational framing, in turn, reflects goal orientation and problem-solving logics typically associated with instrumental leadership. Together, these perspectives illustrate that entrepreneurial ecosystems thrive on the coexistence of affective and instrumental leadership modes, confirming that gendered cognition is not merely a social difference but a structural resource for collective adaptation.

The lexical evidence further illustrates these contrasts. Women’s discourse prioritizes emotionally charged terms—Worrisome, Discouraging, Empathetic—suggesting a cognitive framing centered on relational responsibility and emotional resilience. Men’s vocabulary, dominated by Uncertainty, Impulsive, and Perseverant, reflects an instrumental approach oriented toward control and execution. Both groups experience entrepreneurship as stressful, yet they interpret that stress through different emotional and cognitive registers.

From a practical standpoint, these gendered patterns highlight the need for differentiated support mechanisms within entrepreneurial ecosystems. Programs for women should strengthen emotional support networks and confidence-building spaces, while those targeting men should focus on structured planning, long-term strategy, and reflective decision-making. At a systemic level, the general undervaluation of innovation among both groups suggests that success metrics in subsistence economies must be reframed to include sustainability, adaptability, and community-based collaboration as legitimate indicators of entrepreneurial performance.

Theoretically, these distinctions underscore the importance of incorporating gender as a structuring variable within models of entrepreneurial cognition, moving beyond universalist assumptions of rational decision-making. Recognizing the coexistence of emotional and structural cognition helps design inclusive policies that align cognitive diversity with institutional support, thereby fostering balanced resilience across genders.

These gender-based insights fulfill the third specific objective of the study by demonstrating how emotional and structural perceptions of entrepreneurship differ by gender and by providing an interpretive framework for designing inclusive, context-sensitive entrepreneurial ecosystems. Overall, Ecuadorian entrepreneurship is characterized by a dialectic between collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability, mediated by gendered cognition and contextual constraints. These findings extend theories of entrepreneurial cognition by emphasizing that resilience arises not solely from individual optimism but from collective adaptation within fragile ecosystems. The dual narratives identified here thus bridge micro-level emotional processes and macro-level institutional realities, offering a grounded understanding of entrepreneurship in emerging economies.

These findings also resonate with feminist and intersectional entrepreneurship research, which emphasizes that gender not only differentiates entrepreneurial experiences but also shapes the legitimacy of emotional and relational practices (; ; ). From this perspective, women’s greater focus on relational stress and emotional responsibility reflects the gendered labor of care that underpins many entrepreneurial ecosystems but often remains invisible in policy and theory. Men’s orientation toward structural control and operational challenges, by contrast, aligns with traditional narratives of autonomy and rational agency. Recognizing these differentiated cognitive patterns reveals how institutional and cultural systems reproduce inequalities by valuing instrumental over relational competencies.

Interpreted through this lens, collaborative resilience emerges as a gendered construct that redefines leadership in informal and resource-constrained contexts. Rather than viewing empathy and mutual support as secondary or “soft” attributes, feminist entrepreneurship theory reframes them as strategic resources that sustain collective well-being and long-term viability. This conceptual shift validates women’s relational agency as a form of entrepreneurial leadership that generates resilience through community-building and shared responsibility. Consequently, gendered cognition should be understood not only as a difference in perception but as a structural mechanism that determines access, recognition, and power within entrepreneurial ecosystems.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Contextual Contributions

This study demonstrates that Ecuadorian entrepreneurship is far from monolithic; rather, it represents a mosaic of experiences where global aspirations and local adversities intertwine. The coexistence of collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability illustrates how entrepreneurs in emerging economies construct meaning under conditions of informality and constraint. While existing literature often dichotomizes opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship, our results reveal their interdependence: resilience emerges not as the opposite of vulnerability, but as an adaptive response to it.

The study also contributes to leadership and organizational behavior research by positioning entrepreneurial leadership as a relational construct that transcends formal organizational boundaries. In highly informal ecosystems, leadership manifests through collaborative practices and positive interpersonal exchanges that sustain entrepreneurial activity under uncertainty. By conceptualizing entrepreneurs as relational leaders, the findings bridge entrepreneurship studies and leadership theory, revealing how empathy, adaptability, and social support function as mechanisms of collective resilience. This integration advances the understanding of how leadership fosters positive relationships and psychological safety within nontraditional organizational contexts.

From a theoretical standpoint, the findings advance the understanding of entrepreneurial cognition by highlighting how emotional and contextual dimensions coalesce into distinct perceptual archetypes. The integration of lexical analysis and clustering techniques provides an innovative methodological lens to uncover how entrepreneurs frame their challenges, interpret uncertainty, and negotiate identity within adverse ecosystems. This approach expands current models of entrepreneurial resilience and cognition, positioning language as a key mediating variable in understanding entrepreneurial behavior.

Contextually, the study situates Ecuador within the broader debate on entrepreneurship in developing economies, emphasizing how structural informality, institutional distrust, and gendered experiences shape entrepreneurial discourse. In line with (), the results suggest that persistence itself can be understood as a form of innovation in informal economies—an interpretation that reframes resilience as a creative, context-embedded capability rather than a purely psychological trait.

Conceptually, the integration of collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability advances entrepreneurship theory by connecting micro-level cognitive mechanisms with meso-level relational dynamics. By positioning resilience as a socially co-created process, the study extends existing frameworks of entrepreneurial cognition, leadership, and ecosystem resilience, providing a transferable lens for analyzing adaptive behavior in other emerging economies.

The integration of gendered cognition into this framework further refines the theoretical contribution of the study. By revealing how women and men differentially frame entrepreneurship—women through relational-emotional labor and men through structural and operational control—the findings extend entrepreneurial cognition theory toward a more inclusive understanding of how social roles shape decision-making and resilience. This perspective aligns with feminist entrepreneurship scholarship that recognizes empathy, care, and cooperation as legitimate dimensions of entrepreneurial agency, expanding the relational foundations of leadership theory within emerging economies.

Overall, these insights encourage a shift from rigid, universalist frameworks toward pluralistic approaches that recognize the diversity of entrepreneurial realities in emerging contexts. By acknowledging resilience as both an adaptive and transformative force, Ecuadorian entrepreneurship can be understood as a dynamic system where multiple narratives coexist, evolve, and collectively contribute to sustainable development.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

First, the use of snowball sampling, although necessary to access a highly informal and decentralized population, may have introduced social homophily biases that disproportionately weighted interconnected entrepreneurial networks in Quito. This limitation limits the generalizability of findings to rural or less-integrated regions, where entrepreneurial ecosystems may differ substantially.

Second, the forced-choice instrument, while ensuring methodological consistency, limited participants’ ability to express nuances beyond the 75 predefined attributes. Future studies could combine this technique with open-ended or qualitative approaches to capture richer interpretive dimensions.

Third, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) yielded an RMSEA of 0.093, which is close to the upper threshold of acceptability (0.08–0.10). Although this value aligns with standards for exploratory studies in complex contexts, it underscores the need for larger samples or alternative modeling strategies to refine latent constructs.

Fourth, the study did not examine how ethnicity, class, or geographic location intersect with gender disparities—a relevant gap in multicultural, regionally diverse contexts such as Ecuador. Addressing these dimensions could provide a more nuanced understanding of how sociocultural variables influence entrepreneurial cognition.

Finally, the absence of sectoral comparisons (e.g., trade versus manufacturing) may have obscured domain-specific differences in how entrepreneurship is conceptualized. Future research should incorporate cross-sectoral analyses to identify whether the identified cognitive archetypes vary across industries or value chains.

Future research should adopt a pluralistic methodological orientation to complement the lexical and clustering approach applied here. Ethnographic designs could capture the lived experiences and daily interactions through which collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability are negotiated in practice. At the same time, longitudinal studies would allow us to trace how cognitive and emotional perceptions evolve as ventures mature or confront crises. Mixed-method strategies combining qualitative narratives with quantitative network or discourse analyses could further illuminate the mechanisms through which relational leadership and gendered cognition shape entrepreneurial adaptation over time. Incorporating these methodological perspectives would enhance contextual sensitivity and provide a dynamic view of how resilience, emotion, and collaboration unfold within entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Despite these limitations, the study offers a solid empirical and conceptual foundation for subsequent research seeking to refine methodological tools and deepen contextual analyses of entrepreneurship in emerging economies.

In future applications, the relational–cognitive framework proposed here could be adapted to comparative studies across Latin American, African, and Asian entrepreneurial ecosystems. Such cross-regional replications would not only test the generalizability of the collaborative resilience model but also reveal how cultural and institutional conditions modulate its dynamics. By extending the mixed lexical–clustering methodology to diverse contexts, future research can refine the theoretical architecture of relational leadership and resilience in entrepreneurship.

6.3. Final Remarks

This study demonstrates that entrepreneurship in Ecuador is shaped by two interdependent social forces: collaborative resilience, grounded in empathy, adaptability, and social networks that foster community cohesion; and structural vulnerability, characterized by systemic barriers such as bureaucracy and fear of failure, which perpetuate socioeconomic exclusion. These contrasting narratives reveal the tension between agency and constraint that defines entrepreneurial behavior in emerging economies.

Gender disparities further nuance this picture. Women tend to associate entrepreneurship with relational stress and the need for emotional support, whereas men link it to operational and structural challenges. These findings reflect entrenched social roles that influence entrepreneurial cognition and performance differently. Addressing these disparities requires legitimizing informal economies—which represent more than half of total employment—and implementing inclusive policies that foster trust, reduce institutional inequalities, and enhance social mobility.

The results confirm the fulfillment of the objectives established in the Introduction. The lexical and clustering analyses made it possible to identify how Ecuadorian entrepreneurs conceptualize entrepreneurship, unveiling the coexistence of two cognitive archetypes—collaborative resilience and structural vulnerability. The gender-based analysis further revealed differentiated emotional and cognitive frameworks shaping entrepreneurial experiences. Collectively, these findings advance the theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial cognition and resilience in emerging economies and offer practical guidance for designing policies that promote inclusive, context-sensitive, and sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.-V.; methodology, G.G.-V., L.G.-V. and R.P.-C.; validation, G.G.-V., R.P.-C. and L.G.-V.; formal analysis, G.G.-V. and A.S.-R.; software, R.P.-C.; investigation, G.G.-V., A.S.-R., R.P.-C., L.G.-V. and R.M.-V.; data curation, R.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.-V.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-R.; visualization, L.G.-V., A.S.-R. and R.P.-C.; supervision, R.M.-V.; project administration, G.G.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not involve any clinical procedures, biomedical experimentation, or collection of sensitive personal data. Instead, the data were collected through anonymous surveys and interviews voluntarily completed by adult SME owner–managers, focusing solely on their business perceptions and general demographic characteristics. In Ecuador, according to Acuerdo Ministerial 4883 del Ministerio de Salud Pública (Registro Oficial Suplemento 173, del 12 de diciembre de 2013), ethical review by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Comité de Ética de Investigación en Seres Humanos (CEISH) is required only for biomedical or clinical research that may pose physical or psychological risks to participants. Our study, being observational, non-interventional, and of minimal risk, is exempt under this regulation. Nevertheless, we affirm that all procedures complied with the ethical standards of the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, including respect for informed consent, privacy, and voluntary participation. Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw at any point without consequence. No personal or identifiable information was recorded. The above is assumed to be an exemption from the ethical compliance requirement.

Informed Consent Statement