Abstract

Innovative technology enterprises are recognized internationally as an important pillar in modern economic activity. This paper presents the findings from a research combining qualitative and quantitative methods, with the specific goal of identifying and verifying the characteristics that affect their survival and growth. Results from an in-depth longitudinal qualitative case study, that examines a mature and constantly growing (in its 10-year operation) technologically innovative enterprise, reveal that a number of characteristics pertaining to both the profile of the entrepreneurial team, as well as of the employees, significantly affect company survival and growth in this context. Moreover, we recognize and analyze three stages in its evolution: an initial “evolutionary” growth (infancy and youth), followed by a “revolutionary” (crisis), and a second “evolutionary” (maturity) stage. Our findings are further corroborated and enriched through a survey with N = 27 entrepreneurs in innovative technology startups. We contribute to existing literature on innovative technology entrepreneurship, by identifying characteristics that entrepreneurs and employees should bear, towards its survival and growth. Moreover, a practical application of the life cycle approach is described for technologically innovative companies. Finally, a specific prescription that can help guide future theoretical and practical endeavors in innovative technology entrepreneurship is also provided accordingly.

Keywords:

entrepreneurship; innovative; survival; liability of newness; organizational; culture; employee; case study; viability; growth; longitudinal 1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is generally defined as the “creation of new enterprise” (Low 2001; Low and MacMillan 1988), or “the process of extracting profits from new, unique, and valuable combinations of resources in an uncertain and ambiguous environment” (Amit et al. 1993). It is, moreover, considered as a great force of economic activity, that contributes to the positive growth of various economic indices and economic development in general (Szabo and Herman 2012). Furthermore, entrepreneurship is critical, in order to exploit the potentials of innovative technology (Rogers and Larsen 1984; Wärneryd 1988).

Entrepreneurship research has a history of focusing on a number of questions, such as “Why do some new ventures succeed while others fail? What is the essence of entrepreneurship? Who is most likely to become a successful entrepreneur and why? How do entrepreneurs make decisions? What market, regulatory, and organizational environments foster the most successful entrepreneurial activities?” (Amit et al. 1993). However, a complete and robust explanatory, predictive, or normative theory that would cover such issues is difficult to compile, mainly due to the inherent interdisciplinary nature of entrepreneurship. Integrating perspectives and applying analytic, empirical and experimental tools from a range of fields can be applied, in order to answer some of these fundamental questions (Amit et al. 1993). More importantly, there is no one answer towards why some new ventures succeed, while others fail (Amit et al. 1993; Cooper 1993).

Arguably, one of the most important forms of entrepreneurship is that of technology entrepreneurship. Technology entrepreneurship is a concept that appears to remain quite elusive. This new manifestation of entrepreneurship is also termed as digital entrepreneurship, e-entrepreneurship, cyber-entrepreneurship, or technopreneurism (Foo and Foo 2000; Carrier et al. 2004; Davidson and Vaast 2010; Hafezieh et al. 2011; Ngoasong 2015). Technology entrepreneurship is broadly defined as forming new ventures and transforming existing businesses by developing novel digital technologies and/or novel usages of such technologies (European Commission 2015). Likewise, a number of studies concentrate mostly on the development of novel technologies, highlighting that the digitalization can be generated by technology advances, such as the internet and e-business, mobile and cloud computing, social media and big data, augmented reality and wearable computing, to mention a few (Davidson and Vaast 2010; O’Reilly 2007; Onetti et al. 2012). At the same time, following on from Hull et al. (2007), some degree of digitalization can be derived by new ways of usage of digital technologies, such as: the digital nature of a product or service; its digital distribution; the degree of digital marketing or selling, other internal or value chain operations, or their combination.

Establishing and running a technology entrepreneurship venture differs from starting a traditional venture. Technology ventures go beyond simply adapting and using digital technologies. To them, the role of technology has undergone a transformation as an inherent part of the value proposition (Oestreicher-Singer and Zalmanson 2013). Digital technologies are both the trigger for entrepreneurial activities, and the enabler that supports them (Lusch and Nambisan 2015). The question of how starting a digital venture differs from starting a traditional venture therefore grows more important (Hull et al. 2007), and there is a need to understand the opportunities and hazards unique to technology entrepreneurship (Okkonen 2004). The starting point of this research is hence an interest in the exploration of technology entrepreneurship.

Clearly, designing and setting up a technology venture is in part an ‘art’. Research indicates that the probability of survival is rather limited for new organizations in general (Freeman et al. 1983), and for technology-based firms in particular (Nesheim 1997). Stinchcombe (1965) labeled this phenomenon the ‘liability of newness,’ and argued that new organizations’ general resource poverty, lack of legitimacy, and weak ties to external actors provide them with reduced capacity when competing with established players. A startup requires a decade to establish itself: 20% of startups fail in their first business year, 60% by their fifth year, 75% are not successful by the tenth year, and only 10% of them even survive past that point (Lai and Lin 2015). A number of organizational life cycle models have been proposed in the literature, that involve a transition from an initial “entrepreneurial” phase, to a later phase, in which the firm is dominated by a more bureaucratic type of managerial system (Smith and Miner 1983). Three different stages of corporate growth can also be discriminated accordingly: the initial “entrepreneurial”, maturity, and decline phases (Yang 2012). As most new firms collapse in the post-entrepreneurial phase, understanding what businesses in their early entrepreneurial phase can do in order to ensure their continued survival and growth is important, towards decreasing the high failure rate of new firms (Lai and Lin 2015).

The higher a company’s growth rate, the lower its likeliness of failure (Platt and Platt 1990), and hence, the higher its chances for survival. Many of the activities that new organizations engage in to create wealth take place within the domains of innovation and growth (Ireland et al. 2001). Innovation has been characterized as “the engine that drives revenue growth” in organizations (Patterson 1998), and the basis for organizational survival (Hurley and Hult 1998). Moreover, innovation capability has a significant impact on long-term corporate growth (Yang 2012). However, pursuing innovations is not necessarily associated with survival during the early stages of firm development, as a startup’s innovativeness is in fact negatively associated with its subsequent survival, and entrepreneurs’ greater appetite for risk magnifies this negative association (Hyytinen et al. 2015). Bankrupt firms generally register lower profitability, slower total assets growth, and poorer financial performance (Platt and Platt 1990). Moreover, the effect of the industry on which a company operates is also significant on its growth (Platt and Platt 1990). In the context of this research, we adopt the following definition of corporate growth: “the percentage increase in total assets of a corporation” (Berry 1971). Although the opposite may be assumed at first glance, small companies may in fact be more prone to grow. In fact, corporate size is either unrelated or, in some cases, even negatively related to corporate growth (Berry 1971).

The main research objective of this study can be articulated as follows: to examine the factors that affect the survival and growth of innovative technology entrepreneurship ventures in their initial “entrepreneurial” stage of maturity.

In order to address this objective, a literature review has initially been conducted to create an understanding of the theoretical focus areas. Then, a description of the research methodology is presented. This leads to a presentation of the empirical findings, on the basis of three specific research questions on the linkage between key factors and technology entrepreneurship viability and growth. Finally, an overall conclusion on the research is reached, including suggestions for further research. To do so, this particular study followed a longitudinal case study as the method, to identify the role of key factors in relation to technology entrepreneurship. Identifying the catalytic effect of employees’ and entrepreneurs’ characteristics on the survival and growth of new innovative technology firms, we perform a quantitative study to confirm, as well as expand on, our findings. Specific characteristics with regards to the profile of entrepreneurial teams, as well as employees in such ventures, are recorded and suggested as important to keep aboard new innovative technology firms, in order to increase their chances for survival and growth.

Hence, this research contributes to existing literature on innovative technology entrepreneurship, by identifying and verifying the characteristics that entrepreneurs and employees should bear towards the survival and growth of innovative technology entrepreneurship. Moreover, a practical application of the life cycle approach is described for technologically innovative companies, as we analyze and explain the successive movement of such a company in its maturity, through three stages: an initial “evolutionary” growth (infancy and youth) stage, followed by a “revolutionary” (crisis) stage, and a second “evolutionary” (maturity) stage. Finally, we also provide specific prescription that can help guide future theoretical and practical endeavors in innovative technology entrepreneurship accordingly.

2. Background

2.1. Innovative Entrepreneurship

The emergence of innovative entrepreneurship broadly and positively affects economic development (Aspelund et al. 2005). Highly innovative technological entrepreneurship has, for example, led to Japan impressively prospering since the end of the Second World War (Wärneryd 1988). It is also still considered instrumental in fostering the competitive market economy of the 21st century, as it is a key factor for modern economic development and government policy in the areas of science, education, and intellectual property (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe 2012). Furthermore, it is perceived of as essential to sustain economic growth and development, especially in emerging EU market economies and/or economies struggling to overcome the negative effects of the economic crisis (Szabo and Herman 2012), such as, for example, the Greek economy. Moreover, lack of entrepreneurial activities, and especially innovative entrepreneurship, is one of the major factors blamed for the loss of momentum in the economic development of west European countries and the US (Wärneryd 1988).

Although digital entrepreneurship research has so far been fragmented, divergent and slow to respond to practice, it is rapidly acquiring legitimacy and an identity, as well as growing and becoming more interdisciplinary (Zaheer et al. 2019). The innovative technology industry is full of interesting stories where innovative research ideas were utilized in enterprises that started out small, but rapidly grew into large enterprises (Wärneryd 1988). The rise and reign of Silicon Valley firms is characteristic of this phenomenon that concurrently led to “Silicon Valley fever” that has spread to nations worldwide, including China (Rogers and Larsen 1984). However, innovative enterprises face additional liabilities compared to other new ventures, due to the fact that they need to be both new and different at the same time (Amason et al. 2006).

In innovative technological entrepreneurship, technology itself is rarely the main cause of corporate failure: it is the human and attitudinal components that are most vulnerable instead (Rogers and Larsen 1984). Various parameters affect the creation and successfulness of innovative entrepreneurship. The existence of opportunity is considered to be important in entrepreneurship (Murphy 2017), and has a significant role in creating new ventures: although a potential entrepreneur can be immensely creative and hardworking, without an opportunity to focus on, entrepreneurial activities cannot take place (Baron 2008; Short et al. 2010). These opportunities may be discovered and/or created (Alvarez and Barney 2007), either through a gradual creative process involving the synthesis of ideas over time (Dimov 2007), or by taking the chance to introduce innovative goods, services, or processes (Gaglio 2004). Context is also considered to be important, as it affects the availability of opportunities and sets boundaries for actions (in management research it refers to circumstances, conditions, situations, or environments that are external to the phenomenon under study and to enable or constrain it) (Welter 2011). Moreover, it is important for understanding when, how, and why entrepreneurship happens, as well as who becomes involved in the process, and it can be an asset and/or a liability, as it simultaneously provides individuals with entrepreneurial opportunities and sets boundaries for their actions (Welter 2011). Moreover, entrepreneurship can also produce its own impact on the context where it is deployed. Entrepreneurial behavior is also linked to the social context where it occurs, and as such, it needs to be interpreted in the context in which it occurs (Shane 2003; Welter and Smallbone 2011). As innovative technology entrepreneurship often involves conducting business in challenging environments—such as emerging markets and transition economies with an uncertain, ambiguous, and turbulent institutional framework, under little or no regulatory standardization—context influences its nature, pace of development, and extent, as well as the way entrepreneurs behave within it (Welter and Smallbone 2011).

According to P. F. Drucker, although both innovation and entrepreneurship demand creativity, innovation is indeed the tool of entrepreneurship, especially in view of the need to adapt to great change that exists as part of the 21st century entrepreneurship scenery (Drucker 1985, 1995, 2002). Although the incorporation of innovation is considered one of the most viable strategies for successful entrepreneurship, the successful implementation of corporate innovation is quite elusive for most companies (Kuratko et al. 2014, 2015). Many large corporations fail to develop successful disruptive innovations, due to several inhibiting factors: the inability to unlearn obsolete mental models, a successful dominant design or business concept, a risk-averse corporate climate, innovation process mismanagement, lack of adequate follow-through competencies, and the inability to develop mandatory internal or external infrastructure (Assink 2006). More importantly, organizational structure and culture, the way jobs are designed, work is organized, employees are managed and evaluated as per their performance, are also considered crucial in the context of a corporate new venture (Amit et al. 1993; Fuller and Unwin 2005). More specifically, as more innovation is likely to occur if the decisions to innovate are dispersed among many individuals, the innovation function in corporations should not rely on just a few decision-makers (who may be overly conservative and therefore prevent initiatives that might lead to successful ventures from being brought forward) (Amit et al. 1993).

Based on all of the above, in this paper we examine the corporate design and procedures’ choices that the entrepreneurial team of a successful innovative technology enterprise has made, in order to identify the factors that have contributed to its success.

2.2. Survival and Growth of Innovative Technology-Based Firms

The survival of firms has attracted increasing academic attention in recent years (He et al. 2010). Stinchcombe (1965) labeled this phenomenon the ‘liability of newness,’. Moreover, “Liability of newness” is a construct regularly utilized for directing and positioning research in organizational evolution, that signifies an age dependence in organizational death rates, assuming higher risks of failure for young organizations compared with old ones, and it has been studied in various fields since the early 1980s (Abatecola et al. 2012; Freeman et al. 1983).

Three different stages of corporate growth can also be discriminated accordingly: the “entrepreneurial”, maturity, and decline phases (Yang 2012). In the initial entrepreneurial phase, growth is accomplished through creativity, whereas in the subsequent phases, as the venture matures, first direction, then delegation, afterwards coordination, and finally collaboration, become more dominant. Each growth stage encompasses an evolutionary phase (“prolonged periods of growth where no major upheaval occurs in organization practices”) that typically lasts 4–8 years, and a revolutionary—crisis—phase (“periods of substantial turmoil in organization life”), where the business’ ability to overcome it determines its future (Greiner 1998).

Another term often confused with survival is viability. In the context of business, viability can be described as a firm’s chances and “ability to work as intended or to succeed” (Dictionary.cambridge.com 2020), or its “ability to succeed or be sustained” (Merriam-Webster.com 2020). Viability is usually expressed in financial terms, through a number of ratios that compare a company’s assets to its liabilities. It has been found that the contribution of human capital is immensely more important to the viability of SMEs than to the viability of large corporations and, at the same time, corporations with strong interests in employees’ well-being exhibit much lower bankruptcy risk and leverage (Kosmidis and Stavropoulos 2014). Further to the above, the existence, survival, growth and stability of any corporation are also highly dependent on the efficiency and effectiveness of its management (Nwankwo and Osho 2010)

The higher a company’s growth rate, the lower its likeliness of failure (Platt and Platt 1990), and hence, the higher its chances for survival. Many of the activities that new organizations engage in to create wealth take place within the domains of innovation and growth (Ireland et al. 2001). Innovation has been characterized as “the engine that drives revenue growth” in organizations (Patterson 1998), and the basis for organizational survival (Hurley and Hult 1998). Moreover, innovation capability has a significant impact on long-term corporate growth (Yang 2012). However, pursuing innovations is not necessarily associated with survival during the early stages of firm development, as a startup’s innovativeness is in fact negatively associated with its subsequent survival, and entrepreneurs’ greater appetite for risk magnifies this negative association (Hyytinen et al. 2015). Bankrupt firms generally register lower profitability, slower total assets growth, and poorer financial performance (Platt and Platt 1990). Moreover, the effect of the industry on which a company operates is also significant on its growth (Platt and Platt 1990). SMEs with high levels of R&D intensity, for example, show greater dependence on internal financing and short-term debt, as funding sources of their growth, and the need to pay off the debt and its charges over a short period can often lead to situations of financial stress, preventing those firms from making efficient use of the growth opportunities allowed by R&D business activities (Nunes et al. 2013). In the context of this research, we adopt the following definition of corporate growth: “the percentage increase in total assets of a corporation” (Berry 1971). Although the opposite may be assumed at first glance, small companies may in fact be more prone to grow. In fact, corporate size is either unrelated to, or, in some cases, even negatively related to, corporate growth (Berry 1971).

2.3. Characteristics of Innovative Technology Entrepreneurs

The psychological profile of innovative entrepreneurs is exceptionally difficult to map. Indeed, it is hardly unlikely that a uniform model expressing a single or simple explanation of the psychology of innovative entrepreneurship can be reached, for the following reasons (Wärneryd 1988):

- Entrepreneurship is affected by a combination of environmental/structural factors, situational events and individual variables.

- The amount of innovativeness displayed or required is not uniform across different entrepreneurial activities (from a very small amount in something a little innovative, to a very large amount in something really innovative or never before thought-of).

- Entrepreneurship is multidimensional, and affected by patterns of variables instead of specific values on a single variable.

- Entrepreneurs have been characterized in the literature to be (Wärneryd 1988): (a) motivated by a high need to achieve; (b) deviants, who care little about social skills and are preoccupied with an idea; (c) highly internal in their locus of control; (d) highly motivated by achievement; (e) low in risk aversion (and may be conscious takers of great risks), especially in their own areas of expertise, competence, or skill; (f) highly self-confident; (g) on a quest for novelty—always seeking innovation; (h) highly purposeful in their actions; (i) persistent.

The characteristics of the founding team in high-technology firms have been found to mitigate the liability of newness (Bruton and Rubanik 2002). More importantly, the growth of new technology-based firms is related to various characteristics of the human capital of founders—a.k.a. “the founding team”—(Aspelund et al. 2005; Colombo and Grilli 2005):

- Nature of the founders’ education: Years of university education in economic and managerial fields, and to a lesser extent, in scientific and technical fields, positively affect growth, while education in other fields does not.

- Prior work experience in the same industry as the new firm is positively associated with growth, while work experience in other industries is not. Moreover, the founders’ technical (as opposed to commercial) work experience determines growth.

- Prior entrepreneurial experience, in members of the founding team, results in superior growth.

- Heterogeneous functional experience of the founding team, when combined with radical technological characteristics of the firm’s offering, increases the likelihood for firm survival.

- A combination of the above: Synergistic gains emerge when complementary capabilities of the founders are combined—economic-managerial together with scientific-technical education, and technical together with commercial industry-specific work experience.

The entrepreneurs’ continuing effort after their initial organizing attempts is crucial to the survival of the firm (Yang and Aldrich 2017): whereas only a few initial founding conditions lower the risk of failure, the subsequent activities of the entrepreneurial team—raising additional resources, enacting routines, gaining increased public recognition—play a major role in keeping the venture alive.

Based on the above, we decided to also focus our research on the characteristics of technologically innovative entrepreneurs, as well as their subsequent activities that ensured the viability and development of the venture.

2.4. Employees’ Characteristics in Innovative Technology Enterprises

An innovative entrepreneur needs to choose the right people to employ, even before choosing what they will be working on in the organization. As noted in Jim Collin’s book “Good to Great” (Collins 2002), building great, flourishing, and successful organizations that can last in time, involves selecting the right people to employ, that:

- can adapt and perform brilliantly, no matter the challenges they may face, thus making motivating and managing them a much easier task;

- do not need to be managed as tightly, as they are self-motivated to produce their best results towards creating something great;

- will do the right things and deliver the best results they are capable of, regardless of the incentives they receive in return—compensation and incentives are however important, in order to attract them to, and retain them in, the organization.

As per the specific characteristics of new recruits, employee experience and acquired skills may, is some cases, be sought after in an enterprise (Dzeng et al. 2016; Shaiken 1995). However, the choice between experienced or inexperienced personnel should be made according to the characteristics of the position they shall be filling. Younger entrepreneurial firms tend to employ experience supplementing and utilize outside directors with significant managerial industry experience, in order to compensate for their dearth of top management industry experience, and try to alleviate the burdens of the liability of newness (Kor and Misangyi 2008). However, this is not always the right choice, as in new ventures, the information processing requirements increase with novelty, and therefore—as demographic characteristics influence information processing abilities—younger hires are more fitting in new innovative ventures (Amason et al. 2006).

Further to the above, as new innovative firms usually have no reference in order to “learn by watching” (what competitors are doing in order to learn and imitate them), they are forced by a necessity to act as initiators and to “learn by doing”. In order to do so, teams must interact easily and often, while maintaining unity, alignment, and keeping faithful to the common purpose. This kind of frequent and meaningful interaction has been found to be best facilitated by team homogeneity (age, education level, functional and educational specialization), that in turn, has been found to be positively correlated with venture performance in innovative ventures (Amason et al. 2006).

Work experience is considered to be crucial in specific lines of work, such as healthcare (M. W. Smith et al. 2013). It has also been known to have a positive mental, as well as physical, effect on some less technology-intense work environments (Madeleine et al. 2003). Higher proportions of experienced hiring are also associated with less dynamic business environments (Rynes et al. 1997). On the contrary, no association has been found between experience and relative rated performance in knowledge-intensive jobs (Paré and Elam 1997). At the same time, new graduates are evaluated more highly on open-mindedness, and their willingness and ability to learn new things (Rynes et al. 1997).

In addition, based on data from four independent studies with a total sample size of 1474 (Schmidt et al. 1986), job knowledge was found to be the strongest determinant of work performance, and, while job experience was found to have a substantial direct impact on job knowledge, it has a smaller direct impact on performance capabilities, and furthermore, general mental ability was found to bear a similar effect on work performance compared to job experience. Hence, it is to be expected that new graduates (who have more knowledge of recent tech skills over their more experienced counterparts), will be more fitting and can lead them to better results in innovative technology enterprises, where knowledge is more closely related to the (modern) technical knowledge of employees.

Metaphorically speaking, deciding between hiring inexperienced or experienced employees resembles the dilemma of choosing between a pre-configured computer that is already equipped with the technology and software, and a brand new one that you will build from scratch:

The pre-configured computer (an experienced employee) has what you need, but it also comes with extraneous software that may need to be edited or erased. A custom built computer (an inexperienced employee), on the other hand, is akin to a clean slate—one you must invest time and effort to configure and make it into what you need.(4 Corner Resources 2019)

On the same note, five reasons in favor of hiring someone who lacks industry experience are (Ryan 2017):

- Experienced employees fall into mental ruts, and do not question processes, decisions, or strategies. Hence, inexperienced employees can help towards improvement, by constantly questioning why they were set up this way in the first place.

- When experienced employees are forced to learn the intricacies of a new job, they apply what they have learned in their previous jobs. Inexperience employees, in contrast, do not “carry all that baggage” with them from previous jobs. They start from scratch, and are open to learning what is necessary in order to carry on their duties optimally.

- Experienced employees have performed the same or similar jobs many times, and may be trapped in their traditional methods. They are thus not as useful in rethinking or re-imagining processes or functions as inexperienced recruits are.

- Hiring someone with no experience helps managers develop in the process of training them, asking and answering questions they may not have considered for years, or ever.

- Inexperienced hires provide the organization with a diversity of ideas, as they tend to bring with them vastly different experiences and environmental influences.

When choosing to employ young and inexperienced personnel, one needs to take into account that, unlike the previous generation who were more concerned with the establishment, the new generation of employees (Gen Z) are more concerned with rewards and consider social life as an important aspect (Suryaningrum et al. 2019). Moreover, organizational culture and leadership has a positive direct effect on employee engagement for this new generation (Gen Z) of employees (Suryaningrum et al. 2019).

Based on all of the above, in this research, we focus on the characteristics that the employees in innovative technology enterprises should possess, in order to contribute to the survival and growth of their company, expecting that young and inexperienced recruits may provide for a better organizational fit in this context.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

The overall objective of this research is to clarify the factors that affect the survival and growth of innovative technology entrepreneurship ventures in their initial “entrepreneurial” stage of maturity. This unfolds into the following main research question:

- Research Question: Which are the factors that truly hurdle the survival and growth of a new venture that the entrepreneur must reckon with, while developing a technology-based firm? Moreover, are there any factors that can help the entrepreneur circumnavigate these hinders?This research question is further analyzed, and includes the following two sub-questions:

- -

- Sub-question 1: What are the defining characteristics of the entrepreneurs that affect the survival and growth of innovative technology entrepreneurship ventures in their initial “entrepreneurial” stage of maturity?

- -

- Sub-question 2: What are the defining characteristics of the employees that affect the survival and growth of innovative technology entrepreneurship ventures in their initial “entrepreneurial” stage of maturity?

3.2. Research Design

To effectively address these research questions, we designed our research to include:

- An exploratory study using a retrospective longitudinal autoethnographic case study combined with existing theory (Yin 2003; Fernández et al. 2002). A “social construction of reality” approach was followed, where a single case was utilized as a facilitator (purposeful sampling). This was a refined research questions- and hypotheses-generating approach. The objective was to understand the factors affecting the viability and growth of a newly established innovative technology firm, and formulate more precise research questions and hypotheses.

- A confirmatory study using a questionnaire-based quantitative survey. This was a refined research questions- and hypotheses-testing approach. The objective was to confirm the findings and test the proposed refined research questions from the previous phase. The quantitative analysis was conducted in multiple newly established innovative technology firms (theoretical sampling), and helped us to test the significance of key factors identified in the previous (qualitative) phase, as well as to assess their impact on the survival and growth of these enterprises.

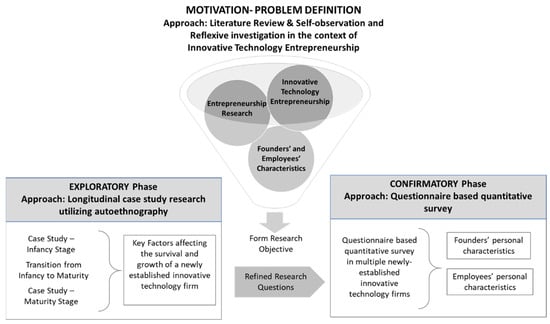

Our overall research approach can be reviewed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Approach.

While the advantage of case study research is depth (and its problem is one of breadth), the situation is the exact reverse for quantitative research conducted in large samples (their advantage is breath and their problem is one of depth) (Flyvbjerg 2006). Hence, mixed methods are necessary for a sound development of social science theory. Adopting a mixed method design advances the systematic integration, or “mixing,” of quantitative and qualitative data within a single investigation or sustained program of inquiry (i.e., the survival and growth of a newly established innovative technology venture) (Zaheer et al. 2019). The mixed method design we follow can be considered as a “gaps and holes” approach (Ridder 2017), as it concentrates on matching the findings from the single case study with patterns in the collected quantitative data in multiple technology ventures.

To sum up, a single retrospective longitudinal case study was first used for theory building, addressing the issue of how a newly established innovative technology venture survives and evolves across time. This qualitative analysis helped us to identify important factors affecting its evolution and growth and formulate more precise research questions and hypotheses. A quantitative analysis was then elaborated upon to test them and build theory.

3.2.1. Exploratory Phase: Evidence from a Retrospective Longitudinal Case Study

This phase involves a retrospective longitudinal case study research utilizing autoethnography. The case concerns a technology firm from its infancy, to its adolescence—the point where it evolved, withstanding numerous obstacles—and its successful rebirth and re-instatement in its field and market. The aim was to record the personal experience and insights of the entrepreneur across all the stages of the new venture creation process.

The case itself was selected intentionally, on the basis of it being either “typical”, “critical”, “revelatory” or “unique” in some respect (Benbasat et al. 1987). The following key characteristics make the specific case typical of a newly established innovative technology venture:

- Innovation capability (Liao et al. 2007): develops new products and services that are well accepted by the market faster than the competitors; has capability in R&D; develops novel skills for transforming old products into new ones; adopts new leadership approaches to lead all staff towards task completion; provides incentives to the staff; monitors the actual discrepancy between performance and goals.

- Technological turbulence (rate of technological changes) in the firms’ industry (Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Zhou 2006): industry is characterized by rapidly changing technology; the rate of technology obsolescence is high; difficult to forecast the technological changes in the next three years; technological changes provide big opportunities.

- Market turbulence (Su et al. 2013; Jaworski and Kohli 1993): the volume and/or composition of demand are difficult to predict; the evolution of customer preference is difficult to predict; new demands in the market are significantly different from existing ones.

- Competitive intensity (Zhou 2006): any action that a company takes, others can respond to swiftly; hear of a new competitive move almost every day; competition is cut-throat;

Case study research was selected as fitting our purpose of study for a number of reasons. First of all, the central notion of case studies is to develop theory inductively (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). Obtaining contextually rich descriptions and a holistic understanding of the case helped us recognize patterns of relationships between constructs, and to explore their underlying explanation. Another reason is that this approach is ideal for answering the “how” and “why” questions (Yin 2003). Moreover, considering that technology entrepreneurship is highly dynamic and fluid (Nambisan 2017; Reason and Bradbury 2001), case study research is suggested as a well-suited approach for researching the intricate phenomena surrounding the survival and growth of a newly established technology firm.

Taking a step forward, this case study research utilizes autoethnography. A number of definitions have been offered for this form of qualitative research in the literature. It has been defined as “a form or method of research that involves self-observation and reflective investigation in the context of ethnographic field work and writing” (Marechal 2010), a “research, writing, story, and method that connect the autobiographical and personal to the cultural, social, and political” (Ellis 2004). Thus, autoethnography was included in this research design, as it utilizes personal experience, in order to describe and critique cultural beliefs, practices, and experiences, while acknowledging and valuing a researcher’s relationships with others, and recording their behavior in the process of “figuring out what to do, how to live, and the meaning of their struggles” (Adams et al. 2015).

Moreover, this case study can be considered as a longitudinal study, as it involves the recording of past experiences and observations through contemplation, and repeated observations of specific variables over a period of time, in order to study the characteristics and/or evolution of phenomena across time (Shadish et al. 2002). More specifically, we explore how the technology venture under study evolves over time and distinguish two main stages (infancy and maturity), as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of main stages of technology ventures examined in this study (adapted from Cardon et al. 2005).

In order to gather the information needed, we combine multiple sources of data collection, enabling ‘triangulation’ (Stake 1995), that adds greater support to research conclusions. Hence, within the present case study, the following techniques were chosen as the most appropriate:

- Personal observations (autoethnography): We spent a great deal of time and effort to analyze the key factors affecting the survival and growth of the innovative technology firm. This was accomplished by active involvement and personal experience in the technology firm.

- Interviews (semi-structured) with key managers and employees concerning their views about the technology venture’s survival and growth. As such, this type of information can be considered as contextual data, in order to develop a thorough understanding of the problem situation. The greatest value of this technique lies in the depth and detail of information that can be secured. This implies that we could have more control and opportunities to improve the quality of information acquired and elicit feedback when needed.

- Company documents of the technology venture that described its economic evolution, as well as the characteristics of its employees over time.

- Mapping of the business model of the technology venture as it evolved from its infancy to its maturity stages. The business model was described in both a narrative and a standardized notation using the business process canvas methodology (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010). All these mappings were validated by discussions with key managers and employees.

3.2.2. Confirmatory Phase: Evidence from a Quantitative Survey

This research phase involves a questionnaire-based quantitative survey. The objective was to test the findings from the previous (qualitative) phase. Although ethnographic methods, like interviews and observations, are mostly used for data collection in case studies, elements from other research methods may be included in a case study research design, such as a survey, in order to collect additional data (Runeson and Höst 2009). This allows for an increase in the precision of empirical research (Runeson and Höst 2009). Such quantitative analysis conducted in multiple newly established innovative technology firms helped us to test the significance of key factors identified through the qualitative phase of our research, and assess their impact on the survival and growth of these enterprises.

More specifically, based on the qualitative results of the case study, specific characteristics of the founders and the employees were defined as important factors towards the viability and growth of their company. To further elaborate on and confirm the importance of these factors, we designed a quantitative survey. The questionnaire was administered to the entrepreneurial teams of eighteen (18) technologically innovative firms who completed the questionnaire.

4. Description of the “Trek” Case Study

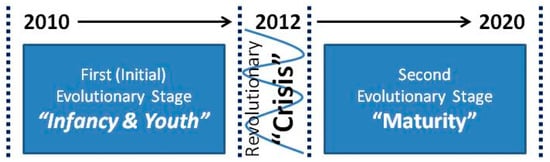

In this section, we detail the characteristics of a case study (in innovative technology entrepreneurship), as it evolved from its infancy stage, through its evolution, and into its current maturity. We refer to this case study as “Trek”, for the purpose of our investigation. Trek is a pseudonym for an established corporation in the field of online presence, with a significant market share in the Greek market. The company has exhibited significant growth, and has survived through its crucial decade (from its establishment in 2010 until today—2020). Therefore, we chose to analyze it in depth, as it is a fitting example of an innovative technology enterprise that managed to survive, as well as succeed, in its market, and achieve long-term sustained growth. As part of the case description, we also utilize the business model canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010), in order to get an insight on how Trek was (re)structured in its stages of evolution, in order to create and sustain value. Moreover, we have recognized and analyzed three stages (Greiner 1998) in Trek’s evolution: An initial two-year “evolutionary” growth stage (infancy and youth), followed by a “revolutionary” (crisis) phase, where the business’s ability to overcome it determined its evolution into its second “evolutionary” stage (maturity). This process of evolution in Trek can be reviewed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Trek’s Evolution over time (2010–2020).

More detailed information on the profile of the employees in Trek in the two different evolutionary stages of the company can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Company Characteristics between the two Evolutionary Stages of Trek.

Examining the table above, we find that the evolution of Trek from its infancy to maturity brought forth a number of changes. A change in the business objective (from online reputation management to digital marketing agency), an increase in the mean age of employees (from 24 to 28), an increased focus on employing personnel with a relative background to the company’s objective (from 50% to 80% of the employees), and less so to relative work experience (from 50% to 60% of the employees), a more balanced mix with regards to gender (from 80% male to 45% male), and a doubling of the retention of employees (from 2 years, to 4 years on average).

More detailed information on the economic indices, as well as the personnel employed in Trek over its 10 years of operation, can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Economic Indices and Personnel Employed in Trek 2010–2020.

Evidently, Trek has been consistently recording sustained growth over the ten years of its operation, both in terms of the number of people employed (from 2 in 2010, to 65 in 2020), as well as in economic indices (44% avg. revenue growth, 40% avg. net revenue increase, and 26% avg. EBITDA margin calculated in net revenue). In the following subsections, a more detailed description of the Trek case over its stages of evolution is provided.

4.1. Description of the Case Study in Its Initial Growth Stage—Infancy and Youth

4.1.1. Business Activity

With the advent of broadband in Greece and abroad, as well as the rapid development of social media, it had become clear that, at that time (2010), more users than ever were in the mood, and disposed of the means to participate, discuss, and form impressions through the exchange of views. The need and desire of companies, not only to monitor, but also to be a part of, these communities of users were obvious. Their interest was prevalent by the fact that more and more companies were building presences on social media sites, either through corporate webpages, or through webpages for the promotion of specific products. In addition, they continued to further invest in promotional activities that utilize information technologies (IT), in general, and the Internet in particular. The IT industry responded to this need with a series of products and services which had already been created and released to the market, attracting the interest of many companies and organizations. These products and services focused mainly on the most popular and international social networking websites (e.g., Facebook.com, Linkedin.com, Twitter.com, etc.), and provided monitoring functions and mining information through these media, as well as management functions for the overall presence of an organization in them.

An important gap in the market of utilization management tools for online user communities was that no tools had been developed to collect and analyze information from users’ discussions conducted in large forums. Forums are a form of communication that pre-existed social media and continued to grow alongside them. However, they cannot be examined in the same way as other social media, as they have distinctive features that significantly differentiate them: in most cases, the users who participate write in the language of the home country of the forum; they are thematic, in the sense that most discussions revolve around a central theme; users are qualified on the topic of each forum, and they can exchange detailed views in great technical detail; visitors (who may not be registered users) turn to these communities to find specialized and objective knowledge.

If the above mentioned are combined with the fact that the forum communities already had many years of operation and a large number of users, it is evident that these websites hosted information about users’ opinions regarding companies, organizations and products, which, in fact, was organized into categories and thematic sections. The information was even available to anyone who was willing to search or ask in these communities. Given all of the above, and assuming that it was important for companies to know consumers’ views about them and their products, there was a pressing need for a tool that would collect, analyze and present a detailed, overall picture of the users’ views, as reflected in all different sites beyond social media.

Trek was founded in 2010, with the aim to fill the aforementioned market needs, utilizing the information which was stored and widely available on forums and blogs. More specifically, Trek operated in the development of a comprehensive solution for opinion mining. The functionality provided to end users can be summarized as follows:

- Monitoring of different data collection sources (e.g., forums, blogs, etc.).

- Offering an overview regarding the extent to which users “talk” about the company and its products, but also about the competition.

- Offering an overview regarding the impressions that users have for the company, its products and the competition.

- Juxtaposition of primary data (users’ comments and references).

- Generation of alerts when discussions related to specific topics are identified.

The tool functions were provided in the form of a service (software as a service model) and the end users could make configurations and adjust the settings in order to more accurately collect and analyze data.

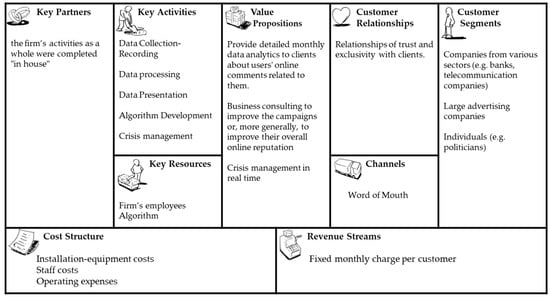

The business model canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010), that describes how Trek was initially structured in order to create value, can be reviewed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Trek’s Business Model Canvas in its Infancy Stage. Adapted from (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010).

4.1.2. Innovation and Competitive Advantage

The services offered by Trek in its initial operation enabled its clients to monitor the data flows emerging from digital social networks, and the world wide web in general, in real-time. The main focus was spotting useful information about the opinion and the mood that the general public had towards a particular company, service or product. The reliable provision of these services was based on the design and implementation of original machine learning algorithms and predictive models.

Their development was based on the effective collection of primary data from various digital social networks, via appropriate programming interfaces that identified those posts that refer to a specific topic of interest in real time. Moreover, the effective operation of these software subsystems was based on the extension of traditional natural language processing and text mining techniques, in order to successfully perform a sequence of actions that aim to clear the original data, such as (a) the fragmentation of the text of each post into words; (b) the exclusion of words that do not bear any semantic content; and (c) the extraction of the root of each word. As part of the automated classification of emotion expressed through posts, algorithms based on deep learning architectures were developed. The development of these techniques has the potential to draw on the most appropriate textual features, for both the problem of thematic modeling and the problem of emotion analysis. This is another point of Trek’s innovative superiority, as this approach was globally in a research phase.

Additionally, innovation was observed in the firm’s structure. All employees were involved and worked on every project undertaken by the firm, as projects were not entirely assigned to one person. Moreover, innovation was also prevalent in the way and means by which processes were greatly automated after the development and adoption of the Trek algorithm in the company’s day-to-day operation.

4.2. Surviving the Revolutionary “Crisis”—Evolving from Infancy to Maturity

The transition of “Trek” from infancy to maturity can be considered as a result of both difficulties with the existing business model, as well as new market trends that arose. More specifically, during the implementation of the first business model, the company faced various difficulties. Some of them played a decisive role and led to the revision and development of the business model. The most significant difficulties are described below.

- Limited market size. As mentioned above, due to the services it provides, the firm had access to the “internal” (confidential) information of its clients. In order for the firm to build relations of trust with its clients, it pledged that it would not concurrently cooperate with any other company operating in the same sector as the client. In that way, the firm eradicated any doubts raised related to the leaking of confidential information it managed. Due to this “exclusivity”, the firm ended up cooperating with one client in each sector, in a total of 4–5 sectors, and very soon there were no more potential clients to approach. This problem eventually proved to be a decisive factor for the restructuring of the company’s business model.

- Increased risk. Trek’s cooperation with its clients was not (at its greatest part) direct. Essentially, the cooperation was achieved through big advertising companies, which brought the companies they represented into contact with Trek. The entailed risk was that the advertising company could disrupt cooperation with Trek at any time. This could result in Trek uncontrollably losing a great portion of its clients. Eventually, this is what happened, resulting in the company losing almost 80% of its revenue overnight. This incident raised concerns to the company’s board members and significantly accelerated the alteration of its business model.

- Difficulty in categorizing comments. As comments were mainly categorized manually at first, and were affected by the subjective opinion of each employee, the firm decided that it would be more objective if two or three employees participated in that process, in order for an overall less biased assessment to be achieved. Even after the incorporation of the “trek” algorithm in this process, the human factor was not eliminated, as there were employees who checked and reviewed the algorithm’s results.

- Lack of specific operating (working) hours. As mentioned above, one of the services that Trek offered to its clients was crisis management. An online incident, irrespective of its significance, could occur any time of the day, or night, and it required immediate management. Thus, the company had to be on constant alert and vigilance, which was exhausting for the employees.

- Lack of technical knowledge. Although the founder’s background was deeply technical, there were no specific skills in the area of machine learning and artificial intelligence within the company. The employees who tried to implement the technology strategy of Trek could not achieve the prerequisite goals that could lead to the success of the algorithms and the software.

In addition to the aforementioned difficulties, the emerging market trends also forced Trek to reposition its presence. For many centuries, the business model of mass media (mainly the press) revolved mainly around concentrating a significantly high share of the public, which was essentially “sold” to advertisers. With the advent of the world wide web, however, companies had the opportunity, and attempted, to reach their audience without the assistance of media companies, thus effectively eliminating the middleman, and doing their own marketing directly. In theory, all an entrepreneur would need nowadays was the development of an online presence program, a hosting and maintenance service provider, and one or more social media accounts. In reality, though, branding is quite different and poses additional difficulties in the age of social media and crowd cultures, and bringing together an online audience—and being able to generate revenue from it—has become a very complex endeavor which requires resources and specialization that most businesses do not possess, especially the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMΕs) (Holt 2016). Therefore, as a result of this business opportunity and dynamics, a new type of media business emerged, which is known in the business world with many different names, such as digital marketing agency, digital advertising agency, or digital services agency. Such a significant change in the business landscape created significant insecurity in advertising companies (media), considerable opportunities in technology companies, and many factors that marketers should take into consideration. Moreover, the consulting services offered by digital marketing agencies became very popular, as most clients, even today, do not have the resources to be as technically skilled and experienced as agencies, nor do they have the connections to salespeople that the employees in agencies usually have.

4.3. Description of the Case Study in Its Second “Evolutionary” Stage—Maturity

As already mentioned, Trek faced significant difficulties during the implementation of its initial business model. The small number of customers, limited market, and increased risk of losing customers to the increasing competition, were elements that troubled the firm’s leadership team and ultimately led it to reconsider its business model, and expand the services it provided. Over a period of three months, the firm’s executives focused on readjusting Trek’s business model, while ceasing to provide any of its services. Finally, in 2012, Trek was reintroduced into the market as a “360 digital marketing agency”, a company that can take over the entire e-business of a client.

4.3.1. Business Activity

Trek is currently one of the most well-known e-business and digital marketing agencies in Greece. Its services portfolio covers a wide range of needs, by providing all the services of a digital marketing agency (i.e., digital media buying, SEO, email marketing, social media management), as well as web application development services. Its aim is to provide all the services a professional may need, in order to make the most of the online sales and promotion channels. In this context, it constantly develops its services, enriching them with additional services, such as UX/UI optimization and business intelligence consulting.

Key products/services: the agency’s digital marketing department offers all the typical services provided by a digital agency: search engine marketing, search engine optimization, email marketing, social media marketing, digital media buying, etc. It consists of groups of consultants who communicate, advise, conduct, and evaluate the effectiveness of each digital marketing campaign and every action on a daily basis, with the aim of continuously improving their performance. In addition, the development department develops web applications, having extensive experience on the PrestaShop platform, which is used by more than 100,000 e-shops worldwide. Benefiting from the synergies between marketing and technology consultants, Trek has recently launched a series of additional services that are complementary, but extremely useful for online businesses, such as UX/UI optimization and business intelligence consulting. Furthermore, the company is a Google Premier Partner, and has been distinguished in a series of initiatives organized by Google. Moreover, it also has an acknowledged relationship with the Facebook ecosystem.

In its mature form, trek’s service portfolio in essence aims to actively assist people in their e-business ventures. The company’s service offering is a comprehensive approach to digital marketing and e-commerce/e-business, as it starts with the initial set up, the transition to online business promotion and the ultimate evaluation of success. This 360-service offered by Trek can be characterized as an umbrella, under which many individual services have been developed and are provided to its clients. These services include:

- Search Engine Marketing: Trek, being a certified partner of Google and one of the most active digital marketing agencies in Greece, has significant experience in using search engines for marketing purposes.

- Social Media Marketing: Trek directs the presence of numerous social media clients’ accounts, and assists them in determining their online strategy and tactics. The clients may be active in the e-commerce sector, or other market sectors (e.g., motorcycles, food, toys and many others).

- Email Marketing: In addition to creating email campaigns and sending newsletters to the client’s customer base, the email marketing section also includes marketing automations. Marketing automations refer to software developed with the aim of automating marketing actions.

- Search Engine Optimization: Search engine optimization refers to a series of technical actions, both within and out of the context of a company’s website, aimed at improving the website’s position in the organic search results of well-known search engines.

- User Experience/User Design (UX/UI): The purpose of the user experience/user design (UX/UI) service offered by Trek is to provide entrepreneurs with guidance, in order to ensure that their e-shop or website interface provides the maximum customers’ satisfaction and usability.

- e-Business and Digital Marketing Consulting: As part of this service, a regular evaluation is made regarding the efficiency of the means of communication and promotion of e-shops. One of the most crucial features of this service is that it is based on reporting and controlling (start, pause, adjust budget, etc.) the actions taken, as well as the results they have generated, with great accuracy, both in terms of quantitative (clicks, impressions, engagement, etc.), and qualitative metrics (ad recall, brand lift, etc.) for each platform/channel, utilizing intricate reporting tools that have been custom-made within the company.

- e-shop/Website Development: Trek usually suggests a specific approach for e-shop development that consists of a series of stages and intermediate deliverables, to ensure that both the visual part and the content of the e-shop are in line with the original development goals.

Notably, although the above mentioned are the main or most common services offered by Trek, acknowledging the fact that this industry is growing rapidly, services are constantly enriched as needed by the company’s clients (changes to existing services; replacement or addition of new ones).

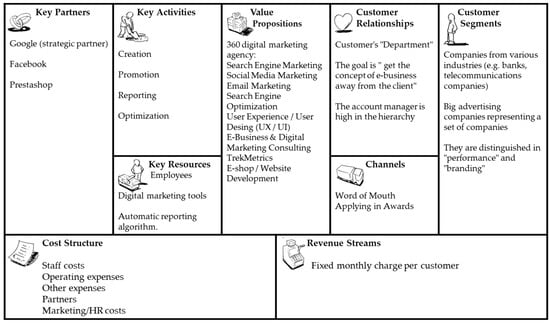

The business model canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010), that describes how Trek was re-structured in order to create value in its maturity can be reviewed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Trek’s Business Model Canvas in its Maturity Stage. Adapted from (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010).

4.3.2. Innovation and Competitive Advantage

Trek’s main advantage in its mature stage of operation is the range of services included in its portfolio, which are offered under a comprehensive, holistic consulting practice. The consulting team works closely with business owners, and manages the translation of business objectives into technical and commercial tasks. Moreover, over the past few years, Trek has won more than 100 awards for its successful project implementation, both in social media and e-commerce/e-business, at a national and multinational level. Moreover, Trek’s distinctive features, which can also be considered as its most important success factors, are the following:

- Comprehensive approach. Trek offers a full range of services that are further enriched by a network of partners, through which the company’s clients can access any digital marketing service they may need, from a single point. These services are provided as part of a comprehensive strategy designed for each client, based on their specific needs and goals.

- People-centered approach. Trek’s philosophy sets the person at its epicenter; either they are its employees, a client, or a partner. The company’s genuine interest in its partners is what made it stand out, especially when the industry was in its infancy and there was a tendency of overestimation by newcomers in the services market. Moreover, Trek seeks long-term, stable relationships, and enjoys seeing its clients succeed.

5. Quantitative Study

The findings from the qualitative study presented above inspired us to further examine the importance of the characteristics and corporate design choices of the entrepreneurs themselves, as well as their companies’ employees, towards the survival and growth of new innovative technology enterprises. Towards that end, we proceeded to conduct an additional—quantitative—study. Based on our recorded insight through the qualitative analysis of the “Trek” case study (analyzed above), as well as extant recorded insight from the literature, we formed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The viability and growth of new innovative technology enterprises are affected by the profile(s) of their entrepreneur(s), and their subsequent choices.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The viability and growth of new innovative technology enterprises are affected by the profile(s) of their employees.

Drawing from these hypotheses, we proceeded to further examine the importance of the characteristics and corporate design choices of the entrepreneurs themselves, as well as their companies’ employees, towards the survival and growth of new innovative technology enterprises. We selected to construct a questionnaire to be administered to the entrepreneurial team in eighteen (18) technologically innovative firms, by following a three-step research process:

- -

- First of all, we asked Trek’s entrepreneur to compile a list of the most defining characteristics of (a) the founders of the company and their corporate design choices, and (b) the profile of the company’s employees, that have affected its viability and growth, according to his own personal judgment.

- -

- Subsequently, we asked entrepreneurs from innovative technology startups to provide their own personal assessment of the most important characteristics that (a) the entrepreneurs, and (b) the employees, of an innovative technology enterprise should bear, in order to ensure its survival and growth.

- -

- Finally, we asked the entrepreneurs of the startups to also rate the importance of (a) the entrepreneurs’ and (b) the employees’ characteristics, that were recorded as important by Trek’s entrepreneur, towards the survival and growth of new innovative technology companies.

For the entrepreneurial team of founders, twelve characteristics were reported by the entrepreneur as most important for the survival and growth of Trek. We elaborated on research hypotheses H1 accordingly: the most important personal characteristics, and corporate design choices, of a new innovative technology enterprises’ founders, that affect its survival and growth, are: Positive thinking (H1a), Trust in People (H1b), Delegation (H1c), Honesty (H1d), Persistence (H1e), Empathy (H1f), Customer Orientation (H1g), Humility (H1h), Efficient allocation of company financial and human resources (H1i), Prioritization and Time Consciousness (H1j), Proactive personality (H1k), and Emotional Intelligence (H1l).

In the same spirit, for the employees of innovative technology firms, fifteen characteristics were recorded as important by the entrepreneur in Trek. We elaborated on research hypothesis H2 accordingly: the most important characteristics of the employees’ profile in a new innovative technology enterprise, that affect its survival and growth, are: They are information junkies/eager to learn new things (H2a), Quick adaptation to a new role (H2b), They are givers/They really care about the company and the client/Team players (H2c), Very tech-savvy (H2d), Not driven by money (H2e), Serial multi-taskers (H2f), Self-motivated/Self-managed (H2g), They can trust (H2h), They challenge the CEO and the management (H2i), They can lead (H2j), Remain optimistic (H2k), Punctual/Get things done on time (H2l), Grounded and humble (H2m), They have strong work ethics (H2n), and They are No-gossip and no-complain oriented (H2o).

In order to record the additional entrepreneurs’ (from innovative technology startups) own perception of the most important characteristics of the founders of their company and their corporate design choices, that, in their personal judgment, were the defining ones that helped towards its viability and growth, we asked them to answer the following questions:

- (1)

- Please list the most important and/or defining characteristics that your entrepreneurial team (founders) possess, that have helped in your company’s viability and growth.

- (2)

- The following list contains personal characteristics that the entrepreneurial team (founders) of a company may possess. Please assess them according to their importance and impact on ensuring the viability and sustained growth of your company (rated on a 5-point Likert scale, between 0 = “not important at all” and 4 = “absolutely essential”).

- (3)

- The characteristics that we rated were selected, based on the findings from the qualitative part of our study. Definitions were provided to the participating entrepreneurs for all of the characteristics that they were called upon to assess. They can be found in Table 4.

Table 4. Definitions of personal characteristics that the entrepreneurial team (founders) of an innovative technology enterprise may possess.

Table 4. Definitions of personal characteristics that the entrepreneurial team (founders) of an innovative technology enterprise may possess.

In order to record additional entrepreneurs’ (from innovative technology startups) own perception of the most important characteristics in the profile of their company’s employees, that, in their personal judgment, were the defining ones that helped towards its viability and growth, we asked them to answer the following questions:

- (1)

- Please list the most important and/or defining characteristics that your employees possess, that have helped in your company’s viability and growth.

- (2)

- The following list contains personal characteristics that the employees of a company may possess. Please assess them according to their importance and impact on ensuring the viability and sustained growth of your company (rated on a 5-point Likert scale; between 0 = “not important at all” and 4 = “absolutely essential”).

- (3)

- The characteristics that we rated were selected based on the findings from the qualitative part of our study. Definitions were provided to the participating entrepreneurs for all of the characteristics that they were called upon to assess. They can be found in Table 5.

Table 5. Definitions of personal characteristics that the employees of an innovative technology enterprise may possess.

Table 5. Definitions of personal characteristics that the employees of an innovative technology enterprise may possess.

The results from this quantitative study are discussed in more detail in Section 6.2 of this paper (“Discussion of Results from the Quantitative Study”).

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of Qualitative Results from the “Trek” Case Study

When conducting case research, three stages take place (Yin 1989): research design; data collection and searching for patterns. In Section 3 we described the case study design, providing the case selection, data collection protocol and field data analysis methods. In Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3, we described each particular stage of the “Trek” innovative technology entrepreneurship case (from its infancy to maturity), concerning the business activity, business model, innovation and competitive advantage. In this section, we further analyze data across the stages, in order to recognize factors that significantly affected, and contributed to, its survival and growth.

First of all, the following characteristics of the entrepreneurial team emerged as important:

- Grit—which is defined as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals” (Duckworth et al. 2007) and characterized by persistence in the face of adversity—is an important characteristic that the founding team of the enterprise must possess. As already outlined, new enterprises, and especially innovative technology enterprises, tend to face many obstacles until they reach their maturity. Hence, grit is particularly useful for entrepreneurs involved in new technologically innovative companies.

- Flexibility (embracing and driving organizational change) is also an important characteristic that the entrepreneurs must possess, in order to decide when, as well as how, their company’s business model may no longer be effective, forego of it, design a new one based on their accumulated experience, and materialize it, having learnt the dos and do nots in the process, so that it may be more effective. This is a process that may have to be followed iteratively, until the tech venture business model reaches a maturity that allows it to be viable and grow. Therefore, in this context it is important for entrepreneurs to know when to quit, redesign, and start again, and a flexible, and insightful, entrepreneur with a vision is needed to do that.

- Prior work experience. Founders’ years of prior work experience in the same industry of the new firm are positively associated with new technology-based firms’ growth than founders’ years of prior work experience in other industries.

- Team size: Team size may affect the probability of survival. The more members that take part in the founding team, the greater is the probability of survival for a new venture. The initial team size is related to survival, as larger teams are generally associated with more resources (Hambrick and D’Aveni 1992), and resourceful teams are known for their ability to mobilize new competencies (McGrath et al. 1996).

- Team heterogeneity: A greater degree of heterogeneity in the functional background of the founding team, leads to a greater probability of survival for a new technology-based firm. The basis for an effective team is not only the number of team members, but it is also highly dependent on the composition of the team. If a team is successful in dealing with the challenges of a complex task, or of a difficult environment, it is vital that it be allowed to possess sufficient internal complexity (Morgan 1997). However, the combination of varying competence within the founding team may result in positive synergistic effects, but may also create hampering and deteriorating conflicts. Team heterogeneity is generally believed to be a positive management team feature.

- Entrepreneurial experience: Entrepreneurial experience initially present in the team yields a greater probability of survival for a new technology-based firm. Due to learning effects, former entrepreneurial experience present in the team should be considered a valuable resource, as team members have previously faced similar challenges. As Gersick (1993) argues, choices between persistence and change are particularly poignant when managers have little experience to help them interpret the seriousness of those obstacles that arise along the way. However, if members of the team have faced similar challenges in the course of other entrepreneurial efforts, the new venture might be more capable of facing such dilemmas.

Taking a step forward, another important set of factors concern the characteristics of the employees of the technology venture:

- Young, Inexperienced, and Tech-Savvy Employees: Making sure that “the right people are kept on the bus” (Collins 2002) ensures that the innovative tech venture remains viable and constantly expanding. Based on the case study, young, well educated, and tech savvy employees, with little to no prior work experience may provide for the optimum fit to innovative tech entrepreneurship ventures. In contrast to traditional hierarchical organizations, in the fast-paced, constantly evolving scenery of innovative tech entrepreneurship, carrying “excessive baggage” from prior work experience may be an obstacle towards innovating, a process that fundamentally needs a clear mind and lack of premonitions and clichés in order to thrive. In our case, millennials were proven to be most fitting to the philosophy and culture of the company, and were able to create value for the company, through their personal thirst for knowledge and personal achievement. The profile of the clients in this entrepreneurial context, as well as the value proposition of the company, may also, in part, explain why that came to be true. Moreover, using many tools at the same time, as well as multitasking capabilities, were needed in order to keep up with the daily work demands. Finally, employee expertise (as reflected by their tech-savviness in our case) has been found to also bear a positive and significant effect on the generation of product innovation in high-tech companies in the past (Pereira and Leitão 2016).

- Employee Retention and Loyalty: Keeping the employees loyal to innovative technology enterprises is crucial. If they were to choose to move to a competing company, they would carry their acquired knowledge (know-how), as well as their personal relationship with the company’s clients (since the company was anthropocentric towards all directions). The clients of the company trusted, were loyal and attached to the company representatives they were cooperating with, due to the fact that they were in direct contact with them, as well as the fact that the company itself was young and had not yet managed to build a strong brand.

Finally, another important set of factors concern the characteristics of the inner working and culture of the technology venture:

- Radicalness of the technology: A greater degree of embedded radicalness in the initially controlled technology leads to a higher probability of survival for a new technology-based firm. Several scholars have demonstrated that the most relevant difference in strategy across technology-based ventures is the degree of technical innovation within the core technology of the firm (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1990). As put forth by Hindle and Yencken (2004), new ventures need to generate discontinuous innovations involving radical inventions, to have the potential for high growth.

- Product innovativeness. The most relevant characteristic of a firm when its survival is the firm’s technical innovativeness (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1990). Technical innovativeness is important, since it impacts the resources of the firm, including financial resources (Romanelli 1989). Innovative products can provide a competitive advantage to a firm, but the greater the innovativeness of the technology, the greater the consumption of resources, since it requires high levels of competence in basic science and resources to promote the new technology (Maidique and Patch 1982).